1. Introduction

APS (antiphospholipid syndrome) is an autoantibody mediated acquired thrombophilia characterized by recurrent arterial or venous thrombosis and/or pregnancy morbidity. It could be Primary or Secondary to other autoimmune disease. Currently the incidence of APS is 5 cases out of 1,00,000 population [

1]. 1% of APS patients present with Catastrophic APS [

2]. Mortality accounted for 37% cases of CAPS with CAPS associated with SLE accounting to higher mortality (48%) [

3]. Here we will discuss a rare presentation of probable CAPS in a background of SLE.

2. Case Summary & Discussion

A 57 years old diabetic, non-hypertensive female presented with severe prostration and pain abdomen associated with vomiting for 1-2 weeks. The pain was acute and generalized, there was no aggravating or relieving factor, no history of radiation, dysuria, or fever. On examination features of Hypovolaemic Shock were present and she was resuscitated in ICU. But there was persistently low blood pressure. Routine Investigations are as in

Table 1. Any infectious or surgical aetiology was ruled out through extensive evaluation.

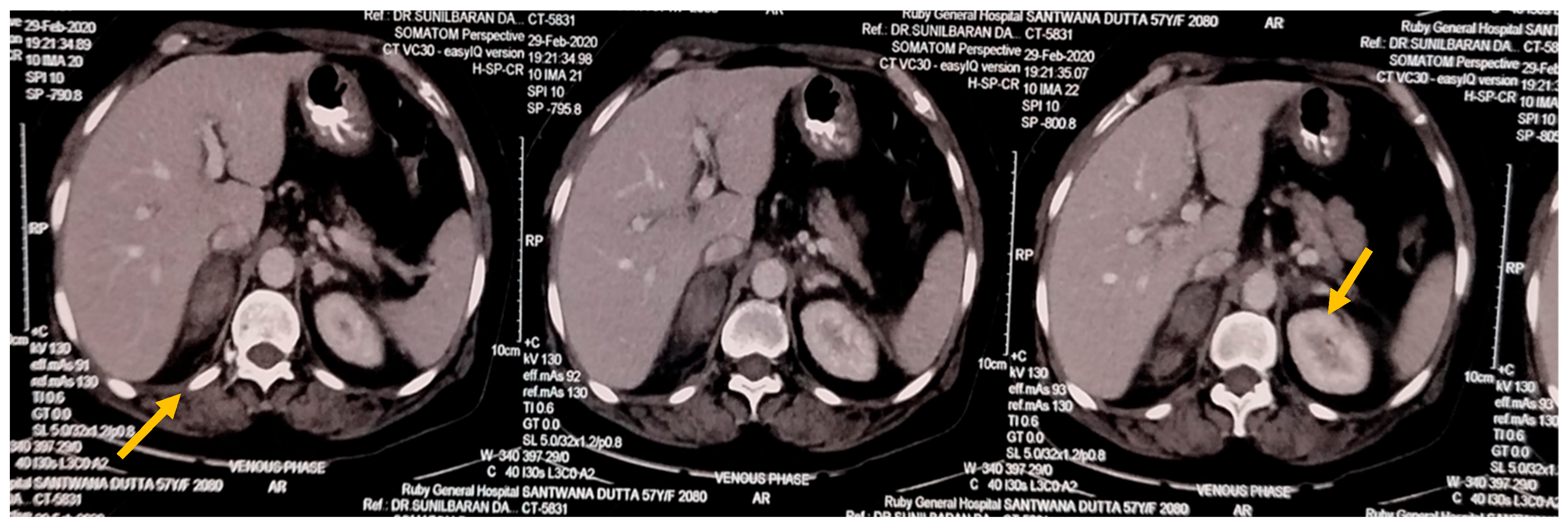

USG Whole Abdomen showed suspected Suprarenal lesion. So, CECT Abdomen was done, which showed hyperdense, non-enhancing lesion in B/L adrenal with perilesional fat stranding—likely Bilateral Adrenal Haemorrhage.

Figure 1.

CECT Abdomen showing Adrenal Haemorrhage (marked by yellow arrows).

Figure 1.

CECT Abdomen showing Adrenal Haemorrhage (marked by yellow arrows).

Then we revisited the case. There was no history of anti-coagulation, gram-negative septicaemia, trauma, no previous history of foetal demise, no previous history of recurrent stroke. There was no precipitating history suggestive of Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation, Thrombotic Microangiopathy. Peripheral Blood Smear was rechecked to rule out Microangiopathic changes like schistocytes. Also, platelet count was low, Prothrombin time (PT) normal, Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time was mildly raised which goes against Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation. There was also no history suggestive of Small Vessel Vasculitis. So, though rare, but to rule out APS (which could be a potential cause of B/L Adrenal Haemorrhage), we did the following investigations:

Anti-B2GP1 IgG (14.00 U/ml), Lupus Anticoagulant, Anti Cardiolipin Antibody IgG was positive (55 GPL). These antibodies were repeated after 12 weeks and came to be positive. APS was diagnosed. There are very few reported cases of B/L Adrenal haemorrhage in APS, as by Hana Aldajaani et al. [

4] and Dr. Rashika Bansal et al. recently [

5].

To rule out any secondary cause, Blood for ANA (IIFT) – Hep 20-10 Cell Line was done, which showed Positive result in 1:100 dilution with Dense Fine Speckled Nuclear pattern. Anti-ds DNA was positive in high titre.

But in this case, we didn’t get any history of skin rash, recurrent oral ulcers, any vasculitic rash, low back pain or any inflammatory polyarthritis.

So, a

Probable Catastrophic APS secondary to SLE was diagnosed. Simultaneously Serum 8 am Cortisol was 9.2μg/dl with Serum ACTH value 180 pg/ml which showed an evolving stage of Primary Adrenal Insufficiency.

Patient was started on Methyl prednisolone pulse therapy followed by IVIG. Subsequently the treatment was followed by maintenance steroid, immunosuppressants like MMF, Anticoagulant. Surprisingly patient’s Plasma Renin Activity was normal, so, mineralocorticoid replacement therapy was not needed. Patient responded dramatically and followed up. Now patient is in absolutely stable condition with oral steroid replacement.

Though rare, but Bilateral Adrenal haemorrhage could be a presentation of APS.

4. Discussion

The temporal relationship between adrenal haemorrhage and evolving adrenal insufficiency in this case aligns with the “two-hit hypothesis” proposed for CAPS, where an initial triggering event (possibly subclinical SLE activity) leads to widespread endothelial damage and subsequent thrombotic microangiopathy [

6]. Antiphospholipid antibodies, particularly anti-β2-glycoprotein I and anti-cardiolipin antibodies, play a crucial role in initiating the thrombotic cascade, by disrupting the annexin A5 shield on endothelial surfaces, exposing phosphatidylserine and creating a prothrombotic environment [

7]. In SLE-associated APS, these effects are potentially amplified by complement activation and immune complex deposition, creating a hypercoagulable state that predisposes to microvascular thrombosis [

8].

The adrenal glands are particularly vulnerable to thrombosis and subsequent haemorrhage due to their unique vascular architecture. They receive rich arterial supply but drain through a single vein, creating a vascular watershed area susceptible to congestion and thrombosis [

9]. When antiphospholipid antibodies trigger thrombosis in the adrenal veins, venous congestion ensues, leading to haemorrhagic infarction [

10]. This pathophysiological mechanism explains the bilateral adrenal involvement observed in our patient.

The absence of typical SLE manifestations in our patient represents what some researchers have termed “serositis-dominant lupus,” where visceral or serological manifestations predominate over cutaneous or articular features [

11]. This phenotypic heterogeneity underscores the importance of comprehensive immunological evaluation in unusual thrombotic presentations, particularly involving the adrenal glands [

12].

Conclusion

Although rare, bilateral adrenal haemorrhage should prompt consideration of APS in the differential diagnosis, particularly when associated with thrombocytopenia and positive antiphospholipid antibodies. This case highlights the importance of recognizing CAPS as a potentially life-threatening condition requiring aggressive immunomodulatory and anticoagulant therapy. Early diagnosis and appropriate management can significantly improve outcomes in this high-mortality condition.

Author Contributions

J.M. and A.R. both contributed to the conception and design of the case report as well as in the acquisition of the patient’s data and imaging readings interpretation of data and the writing of the manuscript; both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, as it is not required for this case report.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CAPS |

Catastrophic Antiphospholipid Syndrome |

| BAH |

Bilateral Adrenal Haemorrhage |

| SLE |

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus |

| CECT |

Contrast Enhanced Computed Tomography |

| β2GP1 |

Beta 2 Glycoprotein |

| ANA |

Anti Nuclear Antibody |

| dsDNA |

Double Stranded DNA |

| ACTH |

Adreno Corticotrophic Hormone |

| IVIG |

Intra-veinous Immunoglobulin |

| MMF |

Mycophenolate Mofetil |

References

- Gómez-Puerta, J.A.; Cervera, R. Diagnosis and classification of the antiphospholipid syndrome. J. Autoimmun. 2014, 48–49, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazzaz, N.M.; McCune, W.J.; Knight, J.S. Treatment of catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2016, 28, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Pintó, I.; Moitinho, M.; Santacreu, I.; Shoenfeld, Y.; Erkan, D.; Espinosa, G.; Cervera, R.; CAPS Registry Project Group (European Forum on Antiphospholipid Antibodies). Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS): Descriptive analysis of 500 patients from the International CAPS Registry. Autoimmun. Rev. 2016, 15, 1120–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldaajani, H.; Albahrani, S.; Saleh, K.; Alghanim, K. Bilateral adrenal hemorrhage in antiphospholipid syndrome. Anticoagulation for the treatment of hemorrhage. Saudi Med. J. 2018, 39, 829–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bansal, R.; Nath, P.V.; Hoang, T.D.; Shakir, M.K.M. Adrenal Insufficiency Secondary to Bilateral Adrenal Hemorrhage Associated with Antiphospholipid Syndrome. AACE Clin. Case Rep. 2020, 6, e65–e69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguila, L.A.; Lopes, M.R.; Pretti, F.Z.; et al. Clinical and laboratory features of overlap syndromes of idiopathic inflammatory myopathies associated with systemic lupus erythematosus, systemic sclerosis, or rheumatoid arthritis. Clin. Rheumatol. 2023, 33, 1093–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meroni, P.L.; Borghi, M.O.; Raschi, E.; et al. Pathogenesis of antiphospholipid syndrome: Understanding the antibodies. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2023, 7, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannakopoulos, B.; Krilis, S.A. The pathogenesis of the antiphospholipid syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 368, 1033–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Presotto, F.; Fornasini, F.; Betterle, C.; et al. Acute adrenal failure as the heralding symptom of primary antiphospholipid syndrome: Report of a case and review of the literature. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2023, 153, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramon, I.; Mathian, A.; Bachelot, A.; et al. Primary adrenal insufficiency due to bilateral adrenal hemorrhage-adrenal infarction in the antiphospholipid syndrome: Long-term outcome of 16 patients. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, 98, 3179–3189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cervera, R.; Rodríguez-Pintó, I; Espinosa, G. The diagnosis and clinical management of the catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome: A comprehensive review. J. Autoimmun. 2023, 92, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinosa, G.; Bucciarelli, S.; Cervera, R.; et al. Laboratory studies in the diagnosis of catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome: A review. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2024, 36, 86–91. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).