1. Introduction

In a context of depleting natural resources, a steadily growing world population and an increase in global warming caused mainly by human action, it is clear that sustainable development is becoming increasingly important in all sectors, and particularly in the industrial sector. Humans are responsible for more than half of the global emissions of some of the main atmospheric pollutants and GreenHouse Gas emissions (GHG), as well as the cause of significant environmental impacts, such as the release of pollutants into water and soil, the generation of waste of all kinds and the main consumer of energy (according to Euro-stat data published in 2018). Therefore, the industrial sector cannot ignore this reality.

The so-called “greenhouse effect” has its origin in the massive emission of certain gases from industrial activities such as CO2, CFCs (ChloroFluoroCarbons), CH4 and N2O, which means that the amount of energy the Earth receives from the Sun is not released normally, but that part of this energy is retained by these gases, which have the capacity to absorb long-wave radiation, considerably increasing the Earth’s surface temperature. Scientific evidence shows that human action is primarily responsible for this increase in greenhouse gases, which is increasing the temperature of the Earth and the oceans, as well as melting much of the polar ice caps.

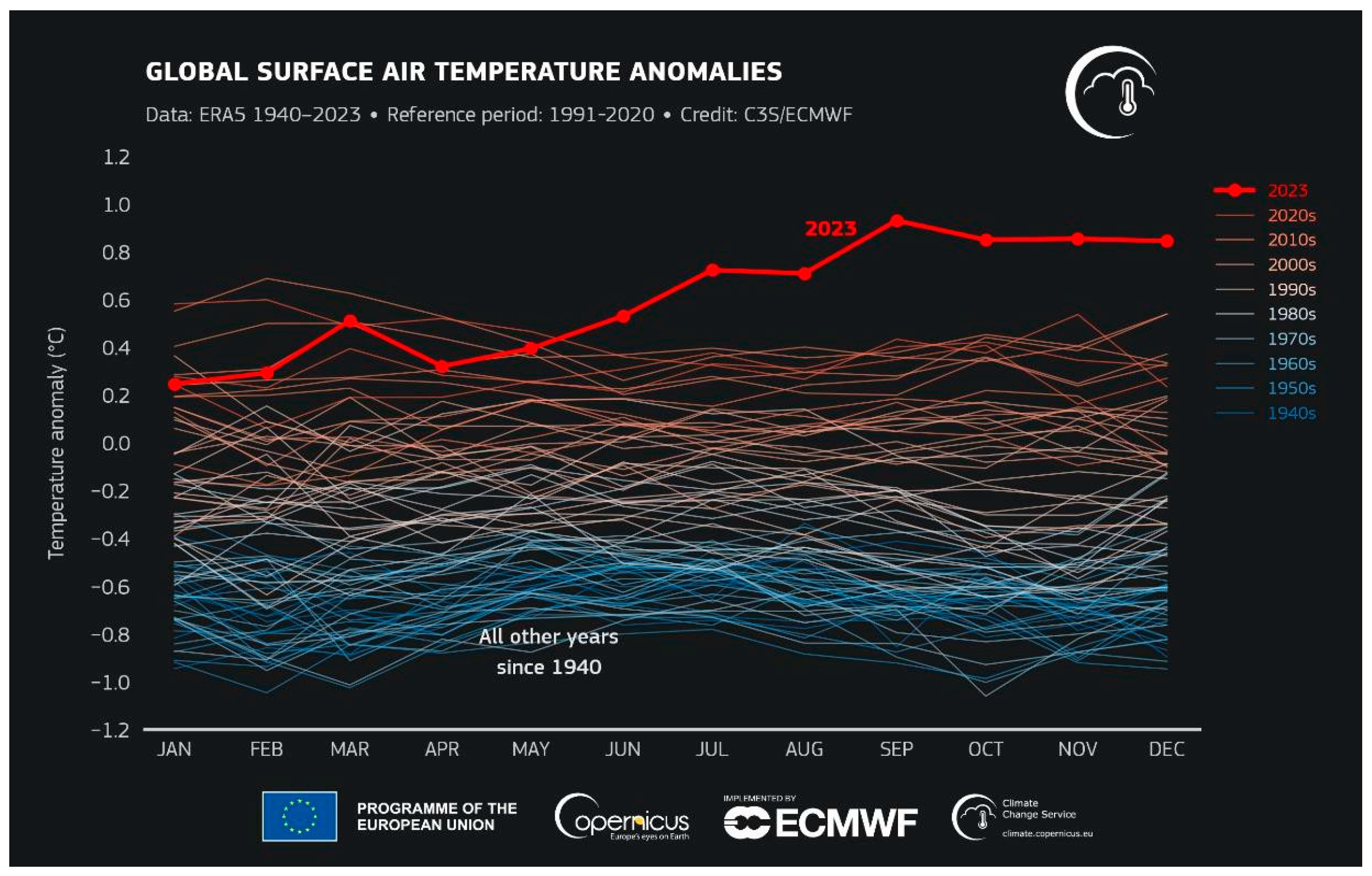

According to data from the powerful climate analysis tool ERA 5 [

1], which uses climate reanalysis for its estimates from satellite and Earth observation data from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), 2023 was the warmest year in the historical series since the first recorded data in 1940. It was also 0.60°C warmer than the average between the years 1991-2020 (

Figure 1) and was estimated to be 1.48°C warmer than pre-industrial levels from 1850-1900.

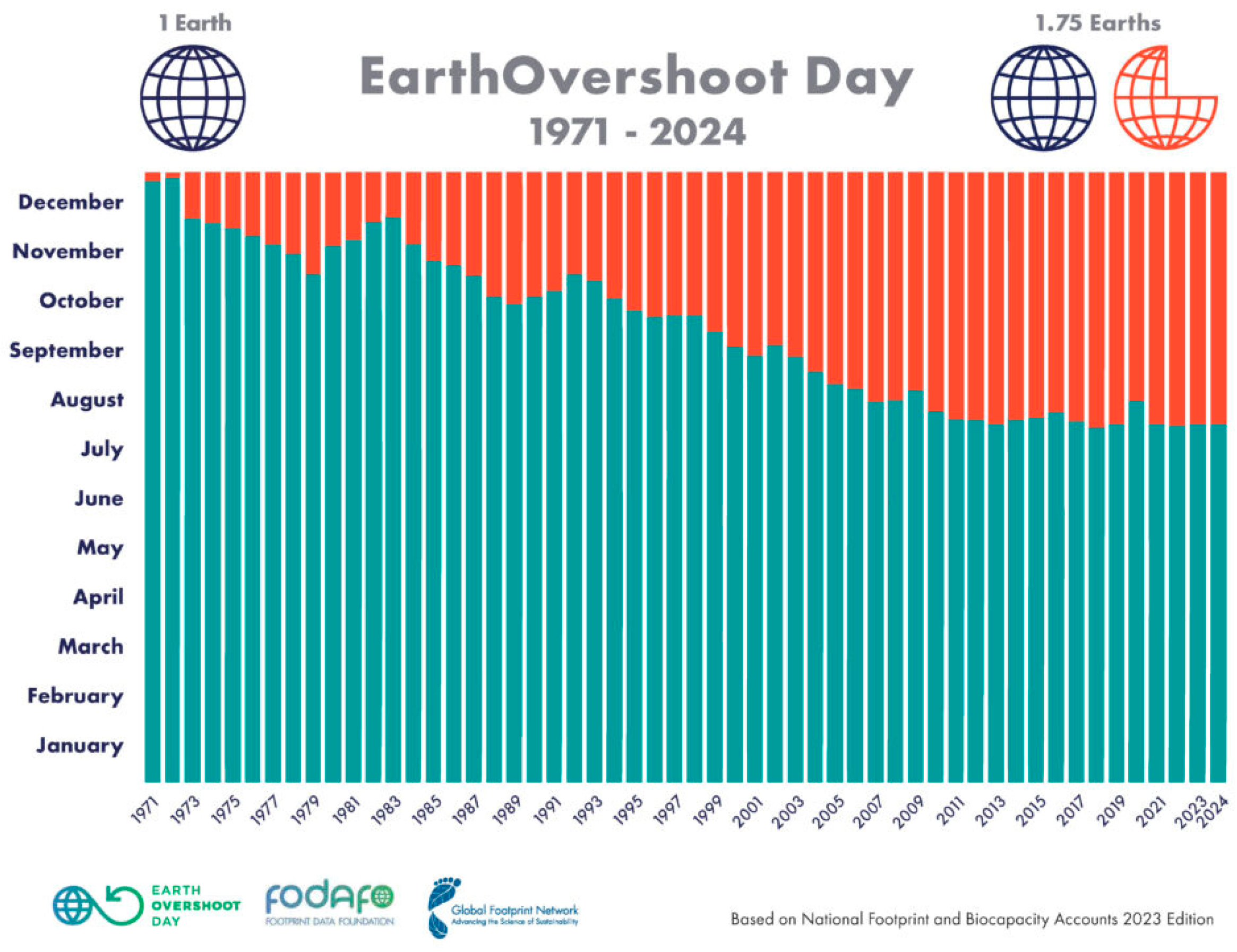

Data on the consumption of raw materials and energy produced worldwide are not encouraging either. The international research organisation Global Footprint Network [

2] calculates each year what it calls Earth Overshoot Day, a measure of the biocapacity (or biological regenerative capacity) of planet Earth, and the ecological footprint generated by global resource demand. In short, biocapacity is measured by calculating the amount of biologically productive land and sea available to provide the resources a population consumes and absorb its waste, taking into account the state of technology and current best management practices.

The result of applying this methodology is a balance between the resources that the planet is capable of generating in a year and the rate at which they are consumed by hu- man activity, ending on a day when humanity goes into the “red” in terms of energy and raw material consumption, a day that is called Planet Overcapacity Day. Data collected since the 1970s show that this day is arriving earlier and earlier in the calendar, as shown in

Figure 2. In 2024, the day on which all the resources the planet can generate would have been consumed was 1 August. This claim graphically represents that the current model of production and consumption is not sustainable, as more than one planet would be needed to satisfy it, currently 1.75 Earths, which leads to the urgent need for a change of model towards sustainability.

Socially, concern for the environment and sustainable development has been gaining ground and the concept of the Circular Economy, which focuses on extending the life cycle of products and processes, reintegrating them into the production chain to reduce their environmental impact to a minimum, is increasingly present. Therefore, there is a growing awareness of the need to reduce the use of plastics in packaging, as well as to generate new biodegradable packaging based on flexible, biodegradable and compostable biopolymer structures in different environments (in particular in soil and marine environments).

At the European level, one of the main challenges that the European Commission has set itself for the coming years is the so-called “Green Deal”, which aims to have a climate neutral continent by 2050, with no net greenhouse gas emissions in that year, and with economic growth that is decoupled from the use of resources. This will only be possible with a paradigm shift in manufacturing processes, as well as in the consumption habits of society as a whole.

The main objective of this grand bargain is to tackle climate change and environmen- tal degradation while creating economic growth and jobs, based on a series of policy ini-tiatives and measures in areas such as energy, agriculture, mobility, industry, biodiversity and the circular economy. Some of the most prominent measures of the Green Deal are [

3]:

Make Europe carbon neutral by 2050.

Increase the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions in the European Union (EU) by 2030 from 40% to 55% compared to 1990 levels. This target reflects as a salient point that Europe must step up the accelerator on CO2 reductions, as current levels are proving in- sufficient.

Promote the use of clean energy from renewable sources and optimise energy effi-ciency in traditionally highly polluting sectors such as transport and construction.

Extending the circular economy and reducing waste generally as a starting point for more sustainable manufacturing.

Protect and restore biodiversity and ecosystems.

The Green Deal is considered one of the world’s most ambitious plans to address climate change and the transition to a more sustainable economy, aiming to “protect, maintain and enhance the EU’s natural capital, as well as protect the health and well-being of citizens from environmental risks and impacts”.

In terms of strategies to achieve this, the pact aims to provide clean, affordable and secure energy, based on a decarbonisation of the energy system (and especially of con- sumption-intensive industries such as steel, chemicals and cement), promoting the use of renewable energies; in this respect, it points to an increase in offshore wind energy pro- duction on the basis of regional cooperation between member states. This pact is silent on the use of nuclear energy due to a lack of agreement between the different countries.

All these objectives on decarbonisation of industry require a robust supply of clean and affordable energy, aimed at increasing the energy efficiency of processes, for which it is essential to generate an ecosystem of industrial research and innovation that allows the development of new, less polluting disruptive technologies, the reduction in the use of fossil fuels and the search for alternative fuels, efficiency in the design and manufacture of products so that they can be more sustainable, among other fields in which there is ample room for improvement.

In short, it is clear that the planet is constantly giving warnings. The current model of production, consumption and mobility is not sustainable, and it is necessary to research and develop new technological solutions aimed at reducing greenhouse gases and waste generation, bearing in mind that technologies alone cannot achieve this without a trans- formational change in society as a whole. Human beings have treated the planet as if natural resources had no limit, or as if the damage caused could be repaired by magic, when the scientific community has been warning for decades of irreparable damage and show- ing signs of the exhaustion of an unsustainable production model. In other words, as quoted textually in [

4]: “We have to revolutionise the way we design, manufacture, use and dispose of things”, something that must involve the whole of society.

2. Materials and Methods

For this article, we have mainly reviewed the Web of Science and Researchgate data bases, consulting only articles that are available in open access, as well as different web resources that are identified and referenced throughout the text.

For the last section (3.3), a systematic review of the literature following the PRISMA methodology [

5] in the Web Of Science database of articles related to research in sustainable manufacturing has been carried out, focusing the search on those dealing with materials, energy and industrial processes.

For this search the following Boolean equations were used: TS=(sustainable manu- facturing) AND TS=(research or research fields or investigation) AND TS=(materials or energy or industrial processes).

Only Open Access articles published during 2024 in the field of engineering, in which the source of publication contains the title “Sustainability” or “Materials”, or “Advanced Energy materials”, or “Advanced materials technologies”, and which, in turn, are a syste- matic review of articles (“Review article”), have been selected in order to have a more representative view.

Filtering with all these criteria, 36 related results were obtained, of which, the most oriented to analyse the main aspects of sustainable manufacturing have been analysed.

3. Results

3.1. Concepts and Definitions of Sustainability in Manufacturing Engineering

3.1.1. Origins of Sustainable Development

The origin of the concept of sustainable development goes back to the Brundtland Report, “Our Common Future” [

6], published on 4 August 1987 by the WCED (World (World Commission on Environment and Development) named after the Norwegian Prime Minister Gro Harlem Brundtland, who at the time was also the chairperson of the WCED. This report warned of the negative environmental consequences of economic development and globalisation, and sought possible solutions to the problems arising from industrialisation and excessive population growth. It contains the best known definition of sustainable development to date:

“Development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

3.1.2. Cleaner Production and Eco-Efficiency

Later, in 1989, the concept of Cleaner Production (CP) was introduced, which was defined by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) as [

7]:

“The continuous application of an integrated environmental prevention strategy in processes, products and services with the aim of increasing their eco-efficiency and reducing their risks to humans and the environment”.

This strategy focuses both on production processes, conserving raw materials and energy, eliminating toxic raw materials and reducing the quantity and toxicity of all emis-sions and waste, and on products, reducing negative impacts throughout the life cycle of a product, from the extraction of raw materials to their final disposal, and on services, incorporating environmental concerns in design and delivery [

7].

The main objective of cleaner production is to achieve zero pollution, something that should be taken more as a horizon than something literal, since all waste has the potential to be polluting and the generation of some is inevitable in certain processes, but it is an objective that drives continuous improvement in eco-efficiency. For this reason, the term “Cleaner Production” is used to describe these efforts, thus avoiding the confusion asso-ciated with the term “Clean Production” which suggests a total elimination of waste.

On the other hand, the concept of Eco-efficiency was adopted in 1992 by the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD), and can be defined as a strategy that combines environmental improvement with economic benefits, achieving more effi-cient production processes by resource consumption and pollution.

Eco-efficiency is a concept that is directly related to technological innovation, in the sense of optimising production processes, minimising the consumption of raw materials and energy, avoiding waste, improving industrial facilities and plants to make them more environmentally sustainable, implementing new technologies, seeking a circular eco- nomy that allows waste to be converted into a new product, treating the waste generated in their production processes appropriately and responsibly, and so on.

3.1.3. Green Chemistry and Green Engineering

The concept of Green Chemistry originated in the 1990s in the USA as a result of pollution prevention laws in this sector, which is of great importance in that country, and is defined as [

8]:

“The design of chemical products and processes that reduce or eliminate the use and generation of hazardous substances”.

It focuses on the prevention of possible pollution at source, and its main objectives include minimising health and environmental risks, reducing waste generation and preventing pollution, promoting the use of less polluting and more efficient technologies and, above all, avoiding the use of some potentially harmful products.

From the analysis of the points in which this concept materialised, it can be conclu-ded that for a product to be manufactured in a sustainable manner, the best techniques available at any given time must be taken into account, dispensing with toxic substances whenever possible, choosing renewable raw materials as opposed to others that are exhaustible, and going deeper into eco-design, among other essential aspects.

Aligned with the principles of Green Chemistry and as an extension of its principles to more industrial sectors, Allen and Shonnard introduced in 2002 the concept of Green Engineering, or Sustainable Engineering as [

9]:

“The design, marketing and use of processes and products, which are technically and economi-cally feasible, while minimising both the generation of polluting waste and the risk to health and the environment”.

As can be seen, the essential idea is the same as in its predecessors, deepening a “cons-cious design” of industrial processes, through: minimising consumption, preventing po-llution rather than treating waste, minimising the diversity of materials, designing for the reuse of materials and the recovery of raw materials, or preferring inputs to the system of renewable raw materials and energy.

3.1.4. Sustainable Manufacturing and the Circular Economy

In line with the aforementioned background, current Sustainable Manufacturing (SM) standards incorporate many of these concepts, and are oriented towards identifying the necessary changes in manufacturing processes, focusing on the type and amount of resources used in their management (prevention, reduction and control), as well as on the control of waste and emissions generated, all taking into account social, environmental and economic aspects with the aim of implementing a circular, safe and efficient eco- nomy.

Among the many possible definitions of SM that can be found in the literature, one is proposed based on the literature review:

The Sustainable Manufacturing (SM) consists of applying an approach based on the rational use of natural resources to manufacturing processes, using advanced technologies that minimise the consumption of raw materials, water and energy, reduce waste generation and greenhouse gas emissions, and promote process circularity.

For its part, the concept of the Circular Economy proposes optimising resources and minimising the waste generated. According to the definition proposed by the European Parliament [

10], it involves

“sharing, renting, reusing, repairing, renewing and recycling existing materials and products as often as possible in order to create added value”, thus extending the life cycle of products and minimising their impact.

Currently, SM has evolved in 3 dimensions that coexist and that are impossible to separate, which are Economic (profitability of processes, technical feasibility and future business opportunities), Ecological (compatibility of activities with the environment and its life cycles, not separating the biosphere from progress) and Equity (attention to quality of life and individual or collective human wellbeing). This is what has come to be called the 3E model, 3BL, or 3E-TBL (Triple Bottom Line) [

11], a concept introduced by Elkington in 1998, which calls for taking into account all environmental, economic and social aspects, without which it is not possible to conceive of SM in all its breadth, bearing in mind that on many occasions, the satisfaction of several of these objectives simultaneously may be incompatible, that they may be totally or partially opposed, so that a balance must be struck between all interests to reach a balance that will be the essence of sustainability. This approach encourages companies to balance their financial objectives with responsible practices towards people and the environment, considering a holistic approach to sustai-nability.

3.2. Main Sustainable Manufacturing technologies

The main objective of sustainable manufacturing technologies is to reduce emissions and minimise the generation of pollutants, reduce energy and water consumption without causing an increase in other pollutants and, in short, improve the environmental balance in the manufacture of a given product, although pollution varies from one element to another. Their application facilitates the digitalisation and automation of production pro-cesses, which is leading to the development of more sustainable processes. The technolo-gies presented below focus on: 1) digitalisation of manufacturing; 2) decentralisation of manufacturing; 3) vertical and horizontal integration of the value chain; 4) increased pro-ductivity; and 5) process flexibility..

The main emerging technologies involved in the Industry 4.0 concept, the basis of the current concept of sustainable manufacturing, are the following [

12] (

Table 1): Additive manufacturing; Artificial intelligence; Internet of things (IoT); Cyber physical systems; Big Data based analytics; Automation and monitoring technologies.

3.2.1. Additive Manufacturing

Additive Manufacturing (AM) is defined as “the process of producing objects by ad-ding material layer by layer based on information from a three-dimensional model” [

13]. This technology, which due to its characteristics is also known as 3D printing, consists of obtaining components by depositing molten material that is then solidified, forming a sin-gle part with homogeneous properties. The two major advantages over conventional pro- cesses are that complex geometries can be obtained and there is no need for complex tooling such as moulds, dies or extrusion dies.

Typically, the use of large format printers using this technology is required for the manufacture of large parts, allowing the use of sustainable and recycled material, as well as the recycling of waste and by-products in the process itself, to take advantage of and cover the full life cycle of the raw material that enters the system.

3D printing allows parts to be optimised in such a way that they can perform the same function at up to 60% of the conventional weight. In addition, it also reduces waste because only the material required to manufacture the part is used, generating very little waste in post-processing, and this waste can be reused in most cases, especially in the case of metallic materials [

14].

The main processes of AM are as follows [

15]:

Based on extrusion of the heated material, such as FDM (Fused Deposition Modelling), which is very widespread due to its low price and simplicity

applicable to materials such as polylactic acid (PLA), ABS (Acrylonitrile Butadiene Butadiene Styrene) or PET-Glycol.

Based on photopolymerisation, such as SLA (Stereolithography) and DLP (Digital Light Processing), which use waxes, resins or ceramic materials for very good finishes and complex morphologies.

Based on material jetting, such as MJ (Material Jetting), where droplets of materials are selectively deposited by a printhead in a liquid state.

Based on binder jetting, such as BJ (Binder Jetting), with the participation of a liquid binder as a binding agent for the material in powder form.

Based on Powder Bed Fusion (PBD), where thermal energy is used to se-lectively melt regions of a powder bed of a given material to generate, as in Selective Laser Melting (SLM) and Selective Laser Sintering (SLS ).

Based on sheet lamination, SL (Sheet Lamination), as in LOM (Laminated Object Manufacturing), in which sheets of a given material are laminated to the desired shape.

Based on directed energy deposition, DED (Directed Energy Deposition), used for stainless steels and metal alloys with the advantage of being able to repair existing parts.

In general, the sustainable manufacturing advantages of AM processes over conven-tional processes can be summarised as follows [

16]:

- It removes raw materials from the supply chain, which also reduces the impacts 322 related to their transport.

- Fewer resources are consumed during the production and use phase.

- Less materials are wasted and fewer pollutants are generated

- Decentralised and local production is encouraged.

- Value chains are redesigned, supply chains are shorter and simpler, production is more localised with more innovative distribution schemes.

- Product lifetime is extended by using sustainability concepts such as reuse, repair, refurbishment and remanufacturing, considering more sustainable approaches in social, economic and environmental terms.

3.2.2. Artificial Intelligence

Today, Artificial Intelligence (AI) is integrated into manufacturing processes to make them more sustainable through various techniques that automate them (eliminating hu-man intervention), and enable autonomous decision-making with very high precision. The main AI techniques used in SM are [

17] genetic algorithms, artificial neural networks and fuzzy logic, which together account for around 70% of the techniques applied, al- though they are most often applied in combination and synergistically.

Genetic algorithms are inspired by biological processes to optimise a set of solutions, and have been used mainly to achieve cost, time and energy reduction, reduce total pro-duction time, among others, in certain industrial processes.

Artificial neural networks (ANNs) are computational models that imitate the beha-viour of neurons in the human brain in terms of their structure and signal propagation, and are programmed in such a way that they can learn by themselves through different processes [

18]. They have special applications in image identification and classification, so they are widely used in factories for defect detection or quality control, and in demand planning, as well as in DOA (Direction of Arrival) in antennas [

18], or in milling processes [

17], in which variable amounts of energy are consumed depending on how the parame-ters of the machines involved (such as cutting speed, depth, or feed rate) are set and ope-rated.

Fuzzy Logic (FL) is an AI technique used to autonomously improve decision making with the aim of reducing the energy consumption of the machines used, reducing production times or improving the quality of the products manufactured. In [

19], this te-chnique was used to optimise a plasma jet cutting process (Jet Manufacturing Process), through the development of an expert system capable of predicting the bevel angle as an indicator of process quality.

3.2.3. Big Data Analytics

The concept of Big Data Analytics (BDA) applies to all information that has characteristics such as high velocity, volume, variety and real-time processing, as well as variability and volatility [

20], and that cannot be processed or analysed using traditional processes or tools.

Their integration into manufacturing processes improves the sustainability of these processes, improving the agility of the supply chain, reducing waste generation and water consumption and optimising energy consumption [

20].

Other studies [

21,

22] showed that the implementation of BDA leads to a reduction in material consumption by 10-15%, energy consumption by around 5%, reduction of waste and rework by around 15%, and is especially useful in task automation, which re- duces manual work by around 20%. In addition, it was found that the implementation of the BDA decreases maintenance, operation and waste generation costs by approximately 12.5% from one year to the next.

3.2.4. Internet of Things

The Internet of Things (IoT) concept, introduced in 1999 by Kevin Ashton in the con- text of his research work in the field of Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) and emer-ging sensing technologies at MIT [

23], involves a network of physical objects (things) with embedded sensors, software and other technologies in order to connect and exchange data with other devices and systems over the Internet.

IoT technologies, connected to software platforms in the cloud (cloud computing), make it possible to manage larger amounts of data faster than traditional servers, and are present in most smart factories. Communication between sensors and the platform is wi-reless (RFID, Bluetooth, Wi-Fi technologies), which optimises energy consumption.

The transparency and visualisation offered by this type of system allows companies to improve production planning and raw material management, avoiding excess inven-tory and wasted processing time, which increases the efficiency of resource use and posi-tively impacts the sustainability of their processes [

24].

3.2.5. Cyber Phisically Systems

Cyber-Physical Systems (CPS) are systems of interconnected elements, both computational and physical, where data are collected and processed in real time. These connections allow machines to make decisions autonomously and respond to changes in their environment automatically [

25], speeding up response to disturbances.

Within this type of system, digital twins, virtual replicas of a product or process, which are updated in real time by taking data from the environment, facilitate the simu-lation, monitoring, analysis and control of a given process.

According to some reports [

26], where more than 1.000 major companies from dif-ferent sectors were interviewed, an overwhelming majority (80%) had digital twins al- ready operational in their facilities or were planning to do so in the near future, which gives a first idea of the relevance of these systems in the industry.

The same report [

26] shows that the use of this technology has allowed Rolls Royce to increase the time between maintenance of some aircraft engines by up to 50%, resulting in a significant reduction in its inventory of parts and spares. It has also improved the efficiency of their engines, enabling one of the airlines they work for to avoid consumption of 85·10

6 kg of fuel and the emission of more than 200·10

6 kg of carbon dioxide since 2014.

3.2.6. Machine Learning

Machine Learning (ML) technologies are a field of Artificial Intelligence that progra-mmes algorithms to ensure that systems that have not been trained for a specific task per-form it satisfactorily. They are based on the construction of a model based on the analysis of input data, captured by all kinds of sensors, which is trained based on the analysis of the results shown by this model, feeding it back and improving it until a definitive model that best adapts to reality is achieved.

Some of the main ML algorithms such as “Random Forest”, “XGBoost” or logistic regression have been tested [

27] to predict quality in finished products manufactured by injection moulding. Injection moulding involves complex production systems due to the combination of numerous parts and the unique specifications of each mould, and thanks to the implementation of this type of ML algorithms in the production process, critical parameters in the process were detected that turned out to be very determinant in the final quality of the product, and that had not been previously identified, such as mould tempe-rature, hopper temperature, injection time or cycle time.

3.2.7. Sustainable Manufacturing in the Metalworking Industry

Some of the sustainable manufacturing technologies described above are applied in the metalworking industry with the aim of making manufacturing processes more envi-ronmentally sustainable. Some studies [

28] have developed models and algorithms that model energy consumption throughout the entire machining process, using tools such as life cycle analysis, which have resulted in different proposals for sustainable manufacturing models applied to different forming technologies, optimising all parameters to achieve the best material removal rate with the shortest tool usage time.

As for the cutting fluids used in machining processes, there has been a move away from hydrocarbon-based mineral oils towards more sustainable fluids, especially vegeta-ble oil-based lubricants derived from soybean, castor, rapeseed and palm oils, synthetic esters or fatty alcohols [

29] [

30].

In this sense, almost all the efforts developed in sustainability in this field are aimed at reducing the amount of cutting fluid used as much as possible, and some “almost dry” machining techniques have been developed, such as the Minimum Quantity Lubrication (MQL) technique, in which a very small amount of cutting fluid is sprayed, This technique also includes the addition of nanoparticles such as aluminium oxide (Al

2O

3) or carbon nanotubes, which have high thermal conductivity and are used to dissipate heat in the cutting zone, further reducing the amount of fluid required [

29].

In other cases [

31], alternatives to MQL and conventional cutting fluids have been tested such as cryogenic machining (performed at temperatures below - 196°C), where liquid gases such as nitrogen (N

2), carbon dioxide (CO

2) and helium (He) are used as al- ternative coolants to conventional oil- and water-based lubricants. This type of machining also modifies the material properties of both the tool and the workpiece by controlling the heat generated in the cutting zone.

As for the casting process, advances in computational calculation and modelling te-chniques have enabled accurate numerical simulations of the filling and solidification sta-ges, as well as of the various physical phenomena involved, which have made it possible to adjust the parameters to improve attributes such as cost, time and quality of the final part and, ultimately, to optimise the process. In [

32], artificial neural networks have been used to minimise the deformation due to non-uniform temperature distribution during die casting of a free-form surface by modifying the geometrical characteristics of a cooling channel. The trained neural network was able to predict the maximum strain value with an error of approximately 2%, and the optimal cooling channel geometry was estimated using the simulated annealing technique. In other cases, it was used to adjust the water flow rates in the casting, resulting in more uniform surface temperature profiles and lower thermal gradients.

3.3. Research Areas in the Field of Sustainable Manufacturing

This report [

33] analyses the use of sustainable materials in construction, opting for biopolymers, obtained from living organisms or by-products, which offer a sustainable solution thanks to their biodegradability, renewability and low energy content, as opposed to the limitations of conventional synthetic polymers, which have made it necessary to seek alternatives with greater environmental compatibility and less ecological impact. The polymers with the best characteristics for use in building cladding are PLA (polylactic acid), PHAs (polyhydroxyalkanoates), starch-based polymers, cellulose, PHB (polyhydroxybutyric acid) and PBS (polybutylene succinate), as they are biodegradable and sustainable, and their potential as substitutes for traditional materials is analysed.

This reports [

34,

35] explore the potential of passive radiative cooling, which emerges as a more sustainable alternative for efficient energy production and use, offering cooling without the need for additional external energy. Despite the introduction of refrigerants with low Global Warming Potential (GWP) and Ozone Depletion Potential (ODP), such as R134a and R1234yf, these options still do not achieve the goal of zero energy consumption. Some applications of these chillers without external energy input are shown for cooling buildings, in textiles that regulate body temperature, in photovoltaic cells, for temperature regulation in greenhouses, to improve the preservation of food packaging, or to collect dew water. All of this is based on radiative coolers made of materials such as ZnO and TiO

2, which must maintain their solar reflectivity and emissivity in the mid-infrared range, even in adverse environmental conditions.

In [

36] a summary is made of 88 publications that analyse the possibilities of integra-ting recycled plastics into additive manufacturing processes, analysing their thermal, me-chanical and rheological properties, as well as environmental and economic implications.

The use of metallic nanoparticles, which serve as an additive to reinforce the polymer matrix, such as carbon fibre and other natural materials, significantly improves the ther-mal and mechanical properties, and therefore the print quality, improving the environ-mental profile. One of the main conclusions of this study [

36] is that incorporating recycled plastics in 3D printing results in a more economical process, reducing both energy consumption and CO

2 equivalent emissions.

In the same vein, the study [

37] indicates that one of the main limitations of introdu-cing recycled plastics such as PLA into AM is the possible deterioration of mechanical properties after repeated recycling, which could limit the usefulness of the material, potentially resulting in increased waste if the degraded material cannot be effectively recycled, although ways are being found to address this through reinforcing the polymer with virgin material or adding other reinforcing materials.

With a little more creativity, [

38] proposes to explore 3D (and 4D) printing applications in the field of Ecology, manufacturing ecological prototypes (coral reefs, terrains, mountainous regions, wetland ecosystems), which allow certain scenarios to be simulated in order to analyse the impact on them with the aim of reducing them.

In [

39] a description of the titanium recycling methods used to manufacture, mainly, aeronautical components by AM is given, providing an overview of the current state of the art in this field, since the production of virgin titanium for indus- trial use by the Kroll process has a high energy, economic and environmental cost. Current scrap metal recovery processes (such as severe plastic deformation, sintering technologies or the Conform process) present multiple limitations for their application to titanium, so it is concluded that, in order to achieve a sustainable use of titanium scrap and powders, new recovery strategies should be studied, which should allow the separation of impurity elements from titanium and optimise processing conditions.

This report [

40] discusses applications of AI in the food industry, with great potential to add value to the sector by implementing AI, machine learning (ML),BlockChain Technology (BCT) and other innovations to improve the entire food value chain, minimising human error, waste and packaging cost, while improving production speed. It is underlined that the adoption of AI (with the ability to improve efficiency, reduce costs and optimise processes in this industry) and blockchain (which can ensure transparency, traceability and security in the supply chain), will not only transform the food industry, but will also have a substantial economic impact globally, due to its ability to optimise supply chains, improve decision making and address sustainability issues, which will have a major impact on the economic growth and competitiveness of the sector in the future.

Finally, in [

41] Life Cycle Assessment is used to explore possible improvements in the design, development, manufacture, use and end-of-life of different medical devices and equipment (through 41 studies), focusing on the reduction of their environmental impact, whose potential damage is manifested at the end of their useful life, with few alternatives for their recovery or proper recycling.

4. Conclussions

From the review carried out, the following conclusions can be extracted:

- -

it is clear that applying the fundamentals of sustainable manufacturing and circularity to industrial processes rationalises the use of the planet’s resources, reduces the consumption of materials and energy, reduces greenhouse gas emissions and saves production costs.

- -

Likewise, in order to achieve the global emissions reduction targets, it is urgent and necessary to decarbonise the energy used in manufacturing, as this is the main source of environmental impact. The use of renewable energies to replace fossil fuels should be encouraged. As a general rule, it is observed that the electrification of industrial processes together with renewable energies (i.e., using a mix of electricity and renewable energies) significantly improves the environmental profile of products and processes, since it is the energy consumption necessary for production that is the main cause of polluting emissions. Countries’ decarbonisation targets need to be more ambitious, given that the expected results are not being achieved. To contribute to this, the use of natural gas in the energy mix must be progressively abandoned, as is being done with coal, as well as developing efficient energy storage systems and promoting the use of clean energies such as biofuels or green hydrogen.

- -

Investment in Research and Development (R&D) is required to improve technologies that optimise processes, develop new, more sustainable materials (lightweight, biodegradable), develop recycling processes for materials that cannot currently be recovered and encourage companies to adopt Best Available Techniques in their industrial processes to reduce their environmental impact.

- -

When assessing sustainability, it is essential to consider a comprehensive 3BL (Triple Bottom Line) approach, taking into account not only the environmental, but also the economic and social perspectives, as exploring improvements in one category without taking into account the others is not feasible and does not produce real changes in society.

- -

The main lines of research in the field of sustainable manufacturing are related to AM; in particular, with the development of technologies that allow the reuse of material waste for use as input material in the process, with the substitution of materials that are difficult to recycle by other more sustainable bio-based materials with a lower environmental impact, with the search for cooling processes without external energy input, as achieved by passive radiative coolers, with the use of AI to optimise processes and obtain maximum economic performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.; methodology, A.M. and E.M.R.; validation A.M. and E.M.R.; formal analysis, A.M.; investigation, A.M.; resources, A.M. and E.M.R.; data curation, A.M. and E.M.R.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.; writing—review and editing, A.M. and E.M.R.; visualization, A.M.; supervision, E.M.R.; project administration, E.M.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the support of the Industrial Production and Manufacturing Engineering (IPME) Research Group and the Innovation and Teaching Group for Industrial Technologies in Productive Environments (TIA Plus UNED).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- ECMWF (European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts) Reanalysis v5 (ERA5). https://www.ecmwf.int/en/forecasts/dataset/ecmwf-reanalysis-v5.

- Global Footprink Network. https://www.footprintnetwork.org/.

- European Commission (2019). COM (Brussels, 2019) 640 final. “The European Green Deal”.

- European Commission (2020). COM (Brussels, 2020) 102 final. “A New Industrial Strategy for Europe”.

- Blanco, D.; Rubio, E.Mª.; Marín, M.Mª.; de Agustina, B. “Propuesta metodológica para revisión sistemática en el ámbito de la ingeniería basada en PRISMA”. (Jaén, 2020). XXII Congreso de Ingeniería Mecánica. Dpto. de Ing. de Construcción y Fabricación, ETSI Industriales. UNED.

- Informe Brundtland, “Our common future”. WCED – World Commission on Environment and Development (1987). Oxford University Press, New York. http://www.un-documents.net/our- commonfuture.pdf.

- Rigola, Miquel. “Producción más limpia”. (Barcelona, 1998). Editorial Rubes. ISBN 9788449700729.

- Kümmerer, K.; Clark, J. “Chapter 4: Green and Sustainable Chemistry”. Recopilado en “Sustainability Science”, editado por Harald Heinrichs, Pim Martens, Gerd Michelsen y Arnim Wiek. Ed. Springer. (2016). ISBN 978-94-017-7241-9.

- Allen, David T.; Shonnard, David R. “Green Engineering: Environmentally Conscious Design of Chemical Processes. PrenticeHall. (2002).

- European Parliament. Definition of circular economy. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/topics/es/article/20151201STO05603/economia-circular-definicion-importancia-y-beneficios.

- Peralta, M.E.; Soltero, V. “Chapter 1: Sustainable manufacturing: needs for future quality development”. (2021). Compiled in “Sustainable Manufacturing”, edited by Kapil Gupta and Konstantinos Salonitis, Elseiver Inc. ISBN: 978-0-12-818115-7.

- Johansen, K.; Akay, S. “Emerging Technologies: Facilitating Resilient and Sustainable Manufacturing”. Jönköping University, Sweden. (2022). [CrossRef]

- ISO/ASTM 52900:2015. “Principios generales para la fabricación aditiva. Terminología”. (International Organization for Standardization, 2015).

- Hernández-Castellano, Pedro M., Gutiérrez, A.; Martínez, Mª. D.; Marrero-Alemán, Mª. D.; Paz, R.; Suárez, Luis A.; Ortega, Fernando. “Tecnologías de Fabricación aditiva”. Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (ULPGC). (2018). ISBN: 978-84-9042-335-6.

- Longfei Zhou, Jenna Miller, Jeremiah Vezza, Maksim Mayster, Muhammad Raffay, Quentin Justice, Zainab Al Tamimi, Gavyn Hansotte, Lavanya Devi Sunkara and Jessica Bernat. “Additive Manufacturing: A Comprehensive Review”. Gannon University, Erie, PA, USA. (USA, 2024). [CrossRef]

- Mehrpouya, M.; Vosooghnia, A.; Dehghanghadikolaei, A.; Fotovvati, B. “Chapter 2: The benefits of additive manufacturing for sustainable design and production”. (2021). Compiled in “Sustainable Manufacturing”, edited by Kapil Gupta and Konstantinos Salonitis, Elseiver Inc. ISBN: 978-0-12-818115-7.

- Agrawal, R.; Majumdar, A.; Kumar, A.; Luthra, S. “Integration of artificial intelligence in sustainable manufacturing: current status and future opportunities”. Oper. Manag. Res. 2023, 16, 1720–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra Fernández, S; Lomaña, Y.; Guzmán, O.A.; Pérez, Y. “Optimización de la Estimación de DOA en Sistemas de Antenas Inteligentes usando criterios de Redes Neuronales”. RIELAC (Revista de Ingeniería Electrónica, Automática y Comunicaciones). Vol XXXIV. (Enero-Abril 2013). p.70-86. ISSN: 1815-5928.

- Peko, I; Crnokic, B; Planinic, I.“Artificial Intelligence Fuzzy Logic Expert System for Prediction of Bevel Angle Quality Response in Plasma Jet Manufacturing Process”. Inlucido en el libro “Digital Transformation in Education and Artificial Intelligence Application. Publisher: Springer Nature. (Suiza, 2023). [CrossRef]

- Ching Horng, ER; Al Mosawi, T. “Effects of Big Data Analytics on Sustainable Manufacturing: A Comparative Study Analysis.” Chinese Journal of Urban and Environmental Studies, 10(4): 2250022‐1 to 2250022‐24. Arden University, UK. (2023).

- Popovič, A.; Hackney, R.; Tassabehji, R.; Castelli, M. (2018) “The impact of big data analytics on firms’ high value business performance”. Inf. Syst. Front. 2018, 20, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Kumar, G.; Singh, R.K. “Big data analytics application for sustainable manufacturing operations: analysis of strategic factors”. Clean Techn Env. Policy 2021, 23, 965–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, K.; Eldridge, S.; Chapin, L. “The internet of things: an overview”, Internet Society. (2015).

- Xiutian, L.; Qianqian, D.; Haozhe, S.; Guo, Y. “Sustainable manufacturing production process monitoring and economic benefit analysis based on IoT technology”. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chugh, J. “Cyber-Physical System (CPS) & Internet of Things(IoT) in Manufacturing”. Eduzone Journal. ISSN: 2319-5045. Volume 8, Issue 2, (Julio-Diciembre 2019).

- Capgemini Research Institute. “Digital twins: adding intelligence to the real world”. (2022).

- Jung, H.; Jeon, J.; Choi, D.; Park, J.-Y. “Application of Machine Learning Techniques in Injection Molding Quality Prediction: Implications on SustainableManufacturing Industry”. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayabaca, C.R. “Desarrollo de un Modelo de Fabricación Sostenible Aplicado a los Procesos de Arranque de Viruta en Entornos Colaborativos”. (2021). Tesis Doctoral de D. César Ricardo Ayabaca Sarria, dirigida por Dr. Carlos Vila Pastor. Universidad Politécnica de Valencia (UPV).

- Debnath, S.; Anwar, M.; Pramanik, A; Basak, A-K. “Chapter 5: Nanofluid-minimum quantity lubrication system in machining: towards clean manufacturing”. (2021). Recopilado en “Sustainable Manufacturing”, editado por Kapil Gupta y Konstantinos Salonitis, Elseiver Inc. ISBN: 978-0-12-818115-7.

- Kharka, V.; Jain, N.K. “Chapter 15: Achieving sustainability in machining of cylindrical gears”. (2021). Recopilado en “Sustainable Manufacturing”, editado por Kapil Gupta y Konstantinos Salonitis, Elseiver Inc. ISBN: 978-0-12-818115-7.

- Cinar Cagan, S.; Baris Buldum, B. “Chapter 10: Cryogenic cooling-based sustainable machining”. (2021). Recopilado en “Sustainable Manufacturing”, editado por Kapil Gupta y Konstantinos Salonitis, Elseiver Inc. ISBN: 978-0-12-818115-7.

- Papanikolaou, M.; Saxena, P. “Chapter 7: Sustainable casting processes through simulation- driven optimization”. (2021). Recopilado en “Sustainable Manufacturing”, editado por Kapil Gupta y Konstantinos Salonitis, Elseiver Inc. ISBN: 978-0-12-818115-7.

- Nazrun, T.; Hassan, M.K.; Hossain, M.D.; Ahmed, B.; Hasnat, M.R.; Saha, S. “Application of Biopolymers as Sustainable Cladding Materials: A Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Bai, S.; Lin, K.; Kwok, C.T.; Chen, S.; Zhu, Y.; Tso, C.Y. “Advancing Sustainable Development: Broad Applications of Passive Radiative Cooling”. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Liang, Z.; Li, W.; Yang, C.; Wang, E. “The Review of Radiative Cooling Technology Applied to Building Roof—A Bibliometric Analysis”. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, I.; Ashour, A.G.; Zeiada, W.; Salem, N.; Abdallah, M. “A Systematic Review on the Technical Performance and Sustainability of 3D Printing Filaments Using Recycled Plastic”. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djonyabe Habiba, R.; Malça, C.; Branco, R. “Exploring the Potential of Recycled Polymers for 3D Printing Applications: A Review”. Materials 2024, 17, 2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szechyńska-Hebda, M.; Hebda, M.; Doğan-Sağlamtimur, N.; Lin, W.-T. “Let’s Print an Ecology in 3D (and 4D)”. Materials 2024, 17, 2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tebaldo, V.; Gautier di Confiengo, G.; Duraccio, D.; Faga, M.G. “Sustainable Recovery of Titanium Alloy: From Waste to Feedstock for Additive Manufacturing”. Sustainability 2024, 16, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ta, M.D.-P.; Wendt, S.; Sigurjonsson, T.O. “Applying Artificial Intelligence to Promote Sustainability”. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montesinos, L.; Checa Rifá, P.; Rifá Fabregat, M.; Maldonado-Romo, J.; Capacci, S.; Maccaro, A.; Piaggio, D. “Sustainability across the Medical Device Lifecycle: A Scoping Review”. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).