Submitted:

31 March 2025

Posted:

01 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Limits of Today’s Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment Toolbox

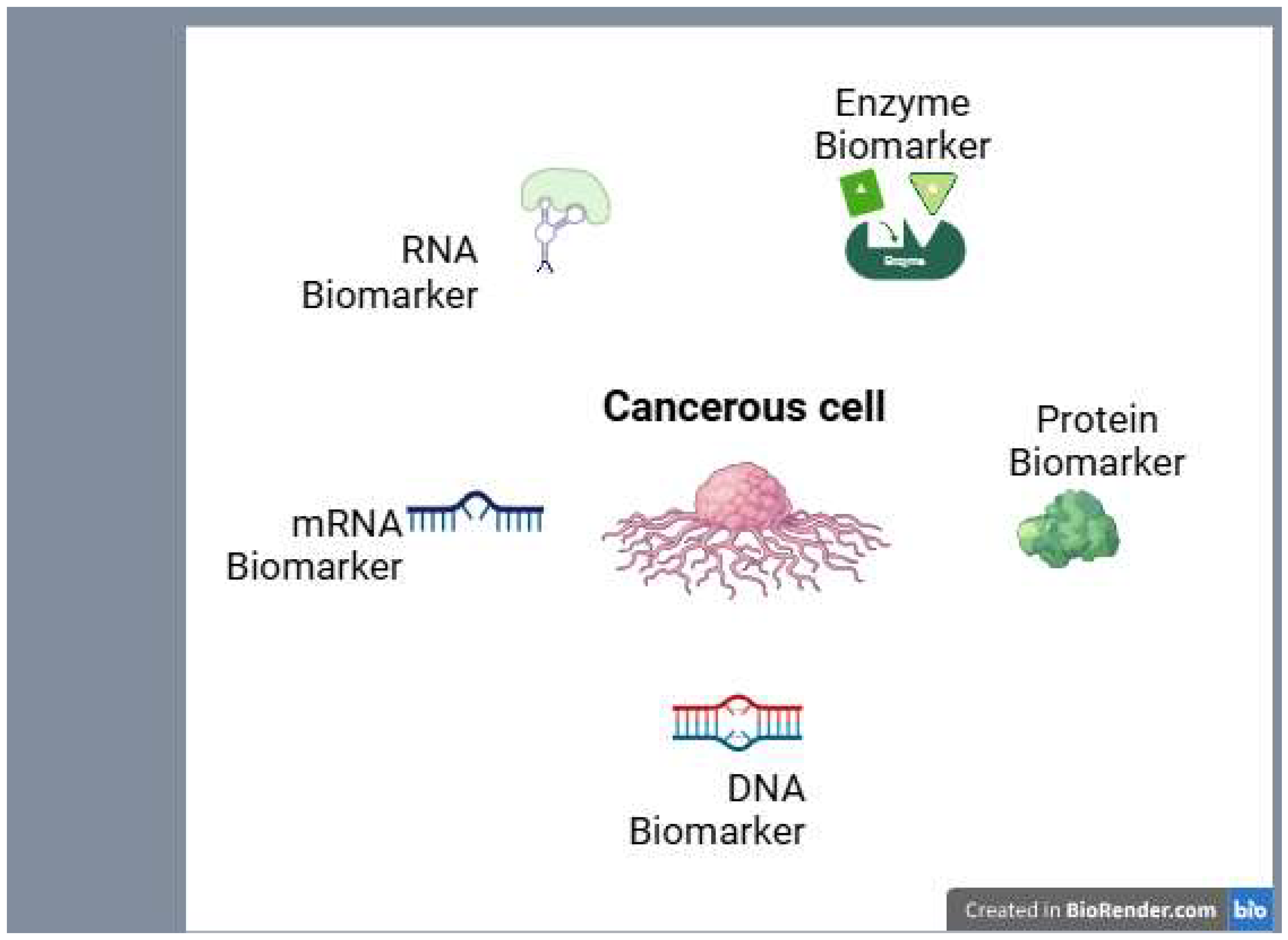

3. Biomarkers: The New Frontier in Cancer Detection

4. Personalized Molecular Therapies: Targeting Cancer’s Weak Spots

5. Bridging Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment: The Power of Integration for Better Health Care

6. In Cancer: Real-World Wins and Challenges Ahead

7. The Road Forward: Scaling the Revolution Against Cancer

8. Conclusion: A New Era in Cancer Care

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AKT | Protein Kinase B |

| ALK | Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase |

| BRCA | Breast Cancer Gene |

| CAR-T | Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-cell |

| CDT | Carbohydrate-Deficient Transferrin |

| CML | Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia |

| CRISPR | Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats |

| ctDNA | Circulating Tumor DNA |

| CUP | Cancer of Unknown Primary |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| DX | Diagnosis |

| EGFR | Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor |

| GIST | Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| HER2 | Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 |

| HPV | Human Papillomavirus |

| KIT | V-Kit Hardy-Zuckerman 4 Feline Sarcoma Viral Oncogene Homolog |

| KRAS | Kirsten Rat Sarcoma Viral Oncogene Homolog |

| mRNA | Messenger Ribonucleic Acid |

| mTOR | Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin |

| NGS | Next-Generation Sequencing |

| PD-L1 | Programmed Death-Ligand 1 |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase |

| PSA | Prostate-Specific Antigen |

| RNA | Ribonucleic Acid |

| RNAi | RNA interference |

| T790M | refers to a mutation in the EGFR (Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor) gene |

| TKI | Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor |

| VEGF | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

| WES | Whole Exome Sequencing |

References

- Carneiro, B.A.; El-Deiry, W.S. Targeting apoptosis in cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 17, 395–417. [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo-Beltrán, D.; et al. Interaction between cigarette smoke and human papillomavirus 16 E6/E7 oncoproteins to induce SOD2 expression and DNA damage in head and neck cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tigu, A.B.; Tomuleasa, C. Exploring Novel Frontiers in Cancer Therapy. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta, E.; Grey, N. Cancer control opportunities in low-and middle-income countries; Wiley Online Library, 2007; pp. 72–74. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, Y.; Kawazoe, A.; Lordick, F.; Janjigian, Y.Y.; Shitara, K. Biomarker-targeted therapies for advanced-stage gastric and gastro-oesophageal junction cancers: an emerging paradigm. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 18, 473–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buzdin, A.; Sorokin, M.; Garazha, A.; Sekacheva, M.; Kim, E.; Zhukov, N.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Kar, S.; Hartmann, C.; et al. Molecular pathway activation – New type of biomarkers for tumor morphology and personalized selection of target drugs. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2018, 53, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pashayan, N.; Pharoah, P.D. The challenge of early detection in cancer. Science 2020, 368, 589–590. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Ma, L.; Huang, C.; Li, Q.; Nice, E.C. Proteomic profiling of human plasma for cancer biomarker discovery. Proteomics 2016, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landegren, U.; Hammond, M. Cancer diagnostics based on plasma protein biomarkers: hard times but great expectations. Mol. Oncol. 2020, 15, 1715–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicklick, J.K.; Kato, S.; Okamura, R.; Schwaederle, M.; Hahn, M.E.; Williams, C.B.; De, P.; Krie, A.; Piccioni, D.E.; Miller, V.A.; et al. Molecular profiling of cancer patients enables personalized combination therapy: the I-PREDICT study. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 744–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.B. Personalized therapy in oncology: melanoma as a paradigm for molecular-targeted treatment approaches. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 2024, 41, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nami, B.; Maadi, H.; Wang, Z. Mechanisms Underlying the Action and Synergism of Trastuzumab and Pertuzumab in Targeting HER2-Positive Breast Cancer. Cancers 2018, 10, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunte, S.; Abraham, J.; Montero, A.J. Novel HER2–targeted therapies for HER2–positive metastatic breast cancer. Cancer 2020, 126, 4278–4288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, X.; Shen, L. Molecular targeted therapy of cancer: The progress and future prospect. Front. Lab. Med. 2017, 1, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, A.; Hussein, A.; Chamba, C.; Yonazi, M.; Mushi, R.; Schuh, A.; Luzzatto, L. Molecular response to imatinib in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in Tanzania. Blood Adv. 2021, 5, 1403–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Lin, Z. Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Targeted Therapy: Drugs and Mechanisms of Drug Resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hochhaus, A.; Larson, R.A.; Guilhot, F.; Radich, J.P.; Branford, S.; Hughes, T.P.; Baccarani, M.; Deininger, M.W.; Cervantes, F.; Fujihara, S.; et al. Long-Term Outcomes of Imatinib Treatment for Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 917–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenchov, R.; Sapra, A.K.; Sasso, J.; Ralhan, K.; Tummala, A.; Azoulay, N.; Zhou, Q.A. Biomarkers for Early Cancer Detection: A Landscape View of Recent Advancements, Spotlighting Pancreatic and Liver Cancers. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2024, 7, 586–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Wang, J.; Sun, Y. Circulating Tumor DNA as Biomarkers for Cancer Detection. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2017, 15, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, B.; Hindocha, S.; Lee, R.W. The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Early Cancer Diagnosis. Cancers 2022, 14, 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, H.; Shaban, M.; Rajpoot, N.; Khurram, S.A. Artificial Intelligence-based methods in head and neck cancer diagnosis: an overview. Br. J. Cancer 2021, 124, 1934–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessale, M.; Mengistu, G.; Mengist, H.M. Nanotechnology: A Promising Approach for Cancer Diagnosis, Therapeutics and Theragnosis. Int. J. Nanomed. 2022, ume 17, 3735–3749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffer, A.L.; Pearson, S.-A.; Perez-Concha, O.; Dobbins, T.; Ward, R.L.; van Leeuwen, M.T.; Rhee, J.J.; Laaksonen, M.A.; Craigen, G.; Vajdic, C.M. Diagnostic and health service pathways to diagnosis of cancer-registry notified cancer of unknown primary site (CUP). PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0230373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pauli, C.; Bochtler, T.; Mileshkin, L.; Baciarello, G.; Losa, F.; Ross, J.S.; Pentheroudakis, G.; Zarkavelis, G.; Yalcin, S.; Özgüroğlu, M.; et al. A Challenging Task: Identifying Patients with Cancer of Unknown Primary (CUP) According to ESMO Guidelines: The CUPISCO Trial Experience. Oncol. 2021, 26, e769–e779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, B.G.; Aliyuda, F.; Taiwo, D.; Adekeye, K.; Agada, G.; Sanchez, E.; Ghose, A.; Rassy, E.; Boussios, S. From Biology to Diagnosis and Treatment: The Ariadne’s Thread in Cancer of Unknown Primary. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crosby, D.; et al. Early detection of cancer. Science 2022, 375, eaay9040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillies, R.J.; Schabath, M.B. Radiomics Improves Cancer Screening and Early Detection. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers Prev. 2020, 29, 2556–2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anghel, S.A.; Ioniță-Mîndrican, C.-B.; Luca, I.; Pop, A.L. Promising Epigenetic Biomarkers for the Early Detection of Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review. Cancers 2021, 13, 4965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Qu, X. Cancer biomarker detection: recent achievements and challenges. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 2963–2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haga, Y.; Uemura, M.; Baba, S.; Inamura, K.; Takeuchi, K.; Nonomura, N.; Ueda, K. Identification of Multisialylated LacdiNAc Structures as Highly Prostate Cancer Specific Glycan Signatures on PSA. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 2247–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebell, M.H.; Culp, M.B.; Radke, T.J. A Systematic Review of Symptoms for the Diagnosis of Ovarian Cancer. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2016, 50, 384–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, B.; Edwards, R.P. Diagnosis and treatment of ovarian cancer. Hematol. /Oncol. Clin. 2018, 32, 943–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bang, J.Y.; Krall, K.; Jhala, N.; Singh, C.; Tejani, M.; Arnoletti, J.P.; Navaneethan, U.; Hawes, R.; Varadarajulu, S. Comparing Needles and Methods of Endoscopic Ultrasound–Guided Fine-Needle Biopsy to Optimize Specimen Quality and Diagnostic Accuracy for Patients With Pancreatic Masses in a Randomized Trial. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 19, 825–835.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, J.M.; Hocken, D.B. Pancreatic cancer in the media: the Swayze shift. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 2010, 92, 537–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neighbors, J.; Chase, D.; Harrow, B.; Perhanidis, J.; Monk, B. Gastrointestinal Symptoms and Diagnosis Preceding Ovarian Cancer Diagnosis: Delays in Diagnosis and Resulting Effects on Treatment Allocation. Gynecol. Oncol. 2020, 156, e25–e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilley, J.; et al. Ovarian cancer symptoms, routes to diagnosis and survival–Population cohort study in the ‘no screen’arm of the UK Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening (UKCTOCS). Gynecol. Oncol. 2020, 158, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Chen, X. Drug resistance and combating drug resistance in cancer. Cancer Drug Resist. 2019, 2, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, N.; Bivona, T.G. Polytherapy and targeted cancer drug resistance. Trends Cancer 2019, 5, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Wang, D.; Chung, C.; Tian, D.; Rimner, A.; Huang, J.; Jones, D.R. A systematic review and meta-analysis of stereotactic body radiation therapy versus surgery for patients with non–small cell lung cancer. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2019, 157, 362–373.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, B.; He, H.; Chen, B.; Zhou, Q.; Luo, T.; Li, K.; Du, T.; Huang, H. Assessment of treatment outcomes: cytoreductive surgery compared to radiotherapy in oligometastatic prostate cancer – an in-depth quantitative evaluation and retrospective cohort analysis. Int. J. Surg. 2024, 110, 3190–3202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camerini, A.; Mazzoni, F.; Scotti, V.; Tibaldi, C.; Sbrana, A.; Calabrò, L.; Caliman, E.; Ciccone, L.P.; Bernardini, L.; Graziani, J.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Chemotherapy after Immunotherapy in Patients with Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 3642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’cunha, R.; D’cunha, P.; Swarup, S.; Sultan, A.; Mogollon-Duffo, F.; Jahan, N.; Htut, T.W.; Wongsaengsak, S.; Adhikari, N.; Mon, A.; et al. Treatment-related adverse events and tolerability in patients with advanced non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer treated with first-line checkpoint inhibitors in combination with chemotherapy. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, v729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S. Genomics-Guided Immunotherapy for Precision Medicine in Cancer. Cancer Biotherapy Radiopharm. 2019, 34, 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheetz, L.; Park, K.S.; Li, Q.; Lowenstein, P.R.; Castro, M.G.; Schwendeman, A.; Moon, J.J. Engineering patient-specific cancer immunotherapies. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2019, 3, 768–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, S.P.; et al. Early detection of pancreatic cancer. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 5, 698–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farr, K.P.; Moses, D.; Haghighi, K.S.; Phillips, P.A.; Hillenbrand, C.M.; Chua, B.H. Imaging Modalities for Early Detection of Pancreatic Cancer: Current State and Future Research Opportunities. Cancers 2022, 14, 2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsimberidou, A.M.; Fountzilas, E.; Nikanjam, M.; Kurzrock, R. Review of precision cancer medicine: Evolution of the treatment paradigm. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2020, 86, 102019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwong, G.A.; Ghosh, S.; Gamboa, L.; Patriotis, C.; Srivastava, S.; Bhatia, S.N. Synthetic biomarkers: a twenty-first century path to early cancer detection. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2021, 21, 655–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalia, M. Biomarkers for personalized oncology: recent advances and future challenges. Metabolism 2015, 64, S16–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakari, S.; Niels, N.K.; Olagunju, G.V.; Nnaji, P.C.; Ogunniyi, O.; Tebamifor, M.; Israel, E.N.; Atawodi, S.E.; Ogunlana, O.O. Emerging biomarkers for non-invasive diagnosis and treatment of cancer: a systematic review. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1405267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarhadi, V.K.; Armengol, G. Molecular biomarkers in cancer. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, S.K.; Khan, P.; Natarajan, G.; Atri, P.; Aithal, A.; Ganti, A.K.; Batra, S.K.; Nasser, M.W.; Jain, M. Mucins as Potential Biomarkers for Early Detection of Cancer. Cancers 2023, 15, 1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Guan, X.; Fan, Z.; Ching, L.-M.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Cao, W.-M.; Liu, D.-X. Non-Invasive Biomarkers for Early Detection of Breast Cancer. Cancers 2020, 12, 2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, E.; Martínez, D.J.G.; Hosseini, M.-S.; Yoong, S.Q.; Fletcher, D.; Hart, S.; Guinn, B.-A. Identification of biomarkers for the early detection of non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Carcinog. 2023, 45, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolini, A.; Ferrari, P.; Duffy, M.J. Prognostic and predictive biomarkers in breast cancer: Past, present and future. In Seminars in cancer biology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Das, V.; Kalita, J.; Pal, M. Predictive and prognostic biomarkers in colorectal cancer: A systematic review of recent advances and challenges. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 87, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabst, L.; Lopes, S.; Bertrand, B.; Creusot, Q.; Kotovskaya, M.; Pencreach, E.; Beau-Faller, M.; Mascaux, C. Prognostic and Predictive Biomarkers in the Era of Immunotherapy for Lung Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffy, M.; Harbeck, N.; Nap, M.; Molina, R.; Nicolini, A.; Senkus, E.; Cardoso, F. Clinical use of biomarkers in breast cancer: Updated guidelines from the European Group on Tumor Markers (EGTM). Eur. J. Cancer 2017, 75, 284–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, L.N.; Ismaila, N.; McShane, L.M.; Andre, F.; Collyar, D.E.; Gonzalez-Angulo, A.M.; Hammond, E.H.; Kuderer, N.M.; Liu, M.C.; Mennel, R.G.; et al. Use of Biomarkers to Guide Decisions on Adjuvant Systemic Therapy for Women With Early-Stage Invasive Breast Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 1134–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, Y.; Kim, S.; Han, S.-W. Utilizing Plasma Circulating Tumor DNA Sequencing for Precision Medicine in the Management of Solid Cancers. Cancer Res. Treat. 2023, 55, 367–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, J.; Bhagwat, N.; Yee, S.S.; Ortiz, N.; Sahmoud, A.; Black, T.; Aiello, N.M.; McKenzie, L.; O’hara, M.; Redlinger, C.; et al. Combining Machine Learning and Nanofluidic Technology To Diagnose Pancreatic Cancer Using Exosomes. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 11182–11193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Kugeratski, F.G.; Kalluri, R. A novel machine learning algorithm selects proteome signature to specifically identify cancer exosomes. Elife 2024, 12, RP90390. [Google Scholar]

- Das, S.; et al. Biomarkers in cancer detection, diagnosis, and prognosis. Sensors 2023, 24, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, J.; Song, G.; Chen, D.; Li, Y.; Liu, S.; Hu, S.; Rosa, C.; Eichinger, D.; Pino, I.; Zhu, H.; et al. Identification of Serological Biomarkers for Early Diagnosis of Lung Cancer Using a Protein Array-Based Approach. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2017, 16, 2069–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Khoury, V.; Schritz, A.; Kim, S.-Y.; Lesur, A.; Sertamo, K.; Bernardin, F.; Petritis, K.; Pirrotte, P.; Selinsky, C.; Whiteaker, J.R.; et al. Identification of a Blood-Based Protein Biomarker Panel for Lung Cancer Detection. Cancers 2020, 12, 1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomans-Kropp, H.A.; Song, Y.; Gala, M.; Parikh, A.R.; Van Seventer, E.E.; Alvarez, R.; Hitchins, M.P.; Shoemaker, R.H.; Umar, A. Methylated Septin9 (mSEPT9): A Promising Blood-Based Biomarker for the Detection and Screening of Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Res. Commun. 2022, 2, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Meng, J.; Duan, H.; Zhang, D.; Tang, Y. Diagnostic Assessment of septin9 DNA Methylation for Colorectal Cancer Using Blood Detection: A Meta-Analysis. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2018, 25, 1525–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Liu, D.; Zhang, X.; Johnson, H.; Feng, X.; Zhang, H.; Wu, A.H.B.; Chen, L.; Fang, J.; Xiao, Z.; et al. Establishing a Urine-Based Biomarker Assay for Prostate Cancer Risk Stratification. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtit, E.; Vannetzel, J.-M.; Darmon, J.-C.; Roche, S.; Bourgeois, H.; Dewas, S.; Catala, S.; Mereb, E.; Fanget, C.F.; Genet, D.; et al. Results of PONDx, a prospective multicenter study of the Oncotype DX® breast cancer assay: Real-life utilization and decision impact in French clinical practice. Breast 2019, 44, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Gole, J.; Gore, A.; He, Q.; Lu, M.; Min, J.; Yuan, Z.; Yang, X.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, T.; et al. Non-invasive early detection of cancer four years before conventional diagnosis using a blood test. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.C. Transforming the landscape of early cancer detection using blood tests—Commentary on current methodologies and future prospects. Br. J. Cancer 2021, 124, 1475–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echle, A.; Rindtorff, N.T.; Brinker, T.J.; Luedde, T.; Pearson, A.T.; Kather, J.N. Deep learning in cancer pathology: a new generation of clinical biomarkers. Br. J. Cancer 2020, 124, 686–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-Y.; Lin, W.-Y.; Zhou, C.; Yang, Z.-A.; Kalpana, S.; Lebowitz, M.S. Integrating Artificial Intelligence for Advancing Multiple-Cancer Early Detection via Serum Biomarkers: A Narrative Review. Cancers 2024, 16, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.T.; Tan, Y.J.; Oon, C.E. Molecular targeted therapy: Treating cancer with specificity. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 834, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Herbst, R.S.; Boshoff, C. Toward personalized treatment approaches for non-small-cell lung cancer. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 1345–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seebacher, N.A.; Stacy, A.E.; Porter, G.M.; Merlot, A.M. Clinical development of targeted and immune based anti-cancer therapies. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 38, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghiloo, S.; Norozi, S.; Asgarian-Omran, H. The Effects of PI3K/Akt/mTOR Signaling Pathway Inhibitors on the Expression of Immune Checkpoint Ligands in Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cell Line. Iran. J. Allergy, Asthma Immunol. 2022, 21, 178–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashworth, A.; Lord, C.J. Synthetic lethal therapies for cancer: what’s next after PARP inhibitors? Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 15, 564–576. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Guo, M. Synthetic lethality strategies: Beyond BRCA1/2 mutations in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Sci. 2020, 111, 3111–3121. [Google Scholar]

- Hosea, R.; Hillary, S.; Wu, S.; Kasim, V. Targeting Transcription Factor YY1 for Cancer Treatment: Current Strategies and Future Directions. Cancers 2023, 15, 3506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blass, E.; Ott, P.A. Advances in the development of personalized neoantigen-based therapeutic cancer vaccines. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 18, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Li, D.; Zhu, X. Cancer immunotherapy: Pros, cons and beyond. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 124, 109821. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Zhu, J.; Lv, Z.; Qin, H.; Wang, X.; Shi, H. Recent Advances in RNA-Targeted Cancer Therapy. ChemBioChem 2023, 25, e202300633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haque, S.; Cook, K.; Sahay, G.; Sun, C. RNA-Based Therapeutics: Current Developments in Targeted Molecular Therapy of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.-X.; Li, C.; Cheng, Y.-M.; Huang, M.-X.; Zhao, G.-K.; Jin, Z.-L.; Qi, X.-W.; Gu, J.; Ouyang, Q. Advances in Small-Molecule Dual Inhibitors Targeting EGFR and HER2 Receptors as Anti-Cancer Agents. Curr. Med. Chem. 2024, 31, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taieb, J.; Jung, A.; Sartore-Bianchi, A.; Peeters, M.; Seligmann, J.; Zaanan, A.; Burdon, P.; Montagut, C.; Laurent-Puig, P. The Evolving Biomarker Landscape for Treatment Selection in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Drugs 2019, 79, 1375–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restrepo, J.C.; Guevara, D.M.; López, A.P.; Palacios, J.F.M.; Liscano, Y. Identification and Application of Emerging Biomarkers in Treatment of Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer: Systematic Review. Cancers 2024, 16, 2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, Y.-C.; Kirschner, K.; Copland, M. Improving outcomes in chronic myeloid leukemia through harnessing the immunological landscape. Leukemia 2021, 35, 1229–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’shaughnessy, J.; Robert, N.; Annavarapu, S.; Zhou, J.; Sussell, J.; Cheng, A.; Fung, A. Recurrence rates in patients with HER2+ breast cancer who achieved a pathological complete response after neoadjuvant pertuzumab plus trastuzumab followed by adjuvant trastuzumab: a real-world evidence study. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2021, 187, 903–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, K.-G.; Notsuda, H.; Fang, Z.; Liu, N.F.; Gebregiworgis, T.; Li, Q.; Pham, N.-A.; Li, M.; Liu, N.; Shepherd, F.A.; et al. Lung Cancer Driven by BRAFG469V Mutation Is Targetable by EGFR Kinase Inhibitors. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2022, 17, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breadner, D.A.; Vincent, M.D.; Liu, G.; Rothenstein, J.; Menjak, I.B.; Cheema, P.K.; Juergens, R.A.; Mithoowani, H.; Bains, P.; Wang, Y.; et al. Osimertinib then chemotherapy in EGFR-mutated lung cancer with osimertinib third-line rechallenge (OCELOT). J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, TPS9160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambardella, V.; Tarazona, N.; Cejalvo, J.M.; Lombardi, P.; Huerta, M.; Roselló, S.; Fleitas, T.; Roda, D.; Cervantes, A. Personalized Medicine: Recent Progress in Cancer Therapy. Cancers 2020, 12, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walcher, L.; Kistenmacher, A.-K.; Suo, H.; Kitte, R.; Dluczek, S.; Strauß, A.; Blaudszun, A.-R.; Yevsa, T.; Fricke, S.; Kossatz-Boehlert, U. Cancer Stem Cells—Origins and Biomarkers: Perspectives for Targeted Personalized Therapies. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankó, P.; Lee, S.Y.; Nagygyörgy, V.; Zrínyi, M.; Chae, C.H.; Cho, D.H.; Telekes, A. Technologies for circulating tumor cell separation from whole blood. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2019, 12, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Xing, X.-M.; Ding, Y.; Huang, Q. OncoGPT: An AI assistant for genomic-driven precision oncology. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, N.P.; Barua, J.D.; Shaikh, A.P.; Adhav, S.; Petrovic, N.; Jahja, E.; Peshkova, T.; Nakashidze, I. Genetic polymorphism and current biotechnology approaches of therapeutic aspects within endometrial tumors. Euchembioj Rev. 2025, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, H.; Zenklusen, J.C.; Staudt, L.M.; Doroshow, J.H.; Lowy, D.R. The next horizon in precision oncology: Proteogenomics to inform cancer diagnosis and treatment. Cell 2021, 184, 1661–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehm, K.M.; Khosravi, P.; Vanguri, R.; Gao, J.; Shah, S.P. Harnessing multimodal data integration to advance precision oncology. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2021, 22, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pulumati, A.; et al. Technological advancements in cancer diagnostics: Improvements and limitations. Cancer Rep. 2023, 6, e1764. [Google Scholar]

- Zubair, M.; Wang, S.; Ali, N. Advanced Approaches to Breast Cancer Classification and Diagnosis. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dienstmann, R.; Jang, I.S.; Bot, B.M.; Friend, S.; Guinney, J. Database of genomic biomarkers for cancer drugs and clinical targetability in solid tumors. Cancer Discov. 2015, 5, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamel, H.F.M.; Al-Amodi, H.S.A.B. Exploitation of gene expression and cancer biomarkers in paving the path to era of personalized medicine. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2017, 15, 220–235. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Z.; Lian, S.; Mak, S.; Chow, M.Z.-Y.; Xu, C.; Wang, W.; Keung, H.Y.; Lu, C.; Kebede, F.T.; Gao, Y.; et al. Deep RNA Sequencing Revealed Fusion Junctional Heterogeneity May Predict Crizotinib Treatment Efficacy in ALK-Rearranged NSCLC. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2022, 17, 264–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaeger, R.; Weiss, J.; Pelster, M.S.; Spira, A.I.; Barve, M.; Ou, S.-H.I.; Leal, T.A.; Bekaii-Saab, T.S.; Paweletz, C.P.; Heavey, G.A.; et al. Adagrasib with or without Cetuximab in Colorectal Cancer with Mutated KRAS G12C. New Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Li, X.; Zhang, R.; Liu, S.; Xiang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Chen, X.; Pan, T.; Yan, L.; Feng, J.; et al. Combinative treatment of β-elemene and cetuximab is sensitive to KRAS mutant colorectal cancer cells by inducing ferroptosis and inhibiting epithelial-mesenchymal transformation. Theranostics 2020, 10, 5107–5119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donovan, M.J.; Meurs, C.; Fernandez, G.; Madduri, A.S.; Feliz, A.; Zeineh, J.; DeAngel, R.; Westenend, P. AI-enabled digital test to predict disease recurrence for patients with early-stage invasive breast cancer and performance in a MammaPrint low-risk cohort from the Netherlands with a median 6-year follow-up. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.Y.; Chung, J.-Y.; Byeon, S.-J.; Kim, C.J.; Lee, Y.-Y.; Kim, T.-J.; Lee, J.-W.; Kim, B.-G.; Chae, Y.L.; Oh, S.Y.; et al. Validation of Potential Protein Markers Predicting Chemoradioresistance in Early Cervical Cancer by Immunohistochemistry. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khattak, M.A.; Reid, A.; Freeman, J.; Pereira, M.; McEvoy, A.; Lo, J.; Frank, M.H.; Meniawy, T.; Didan, A.; Spencer, I.; et al. PD-L1 Expression on Circulating Tumor Cells May Be Predictive of Response to Pembrolizumab in Advanced Melanoma: Results from a Pilot Study. Oncol. 2019, 25, e520–e527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Incorvaia, L.; Rinaldi, G.; Badalamenti, G.; Cucinella, A.; Brando, C.; Madonia, G.; Fiorino, A.; Pipitone, A.; Perez, A.; Pomi, F.L.; et al. Prognostic role of soluble PD-1 and BTN2A1 in overweight melanoma patients treated with nivolumab or pembrolizumab: finding the missing links in the symbiotic immune-metabolic interplay. Ther. Adv. Med Oncol. 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camidge, D.R.; Doebele, R.C.; Kerr, K.M. Comparing and contrasting predictive biomarkers for immunotherapy and targeted therapy of NSCLC. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 16, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.E.; Chester, J.D. Personalised cancer medicine. Int. J. Cancer 2015, 137, 262–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulton, J.J.; LeBlanc, T.W.; Cutson, T.M.; Starr, K.N.P.; Kamal, A.; Ramos, K.; E Freiermuth, C.; McDuffie, J.R.; Kosinski, A.; Adam, S.; et al. Integrated outpatient palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Palliat. Med. 2018, 33, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balitsky, A.K.; et al. Patient-reported outcome measures in cancer care: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Network Open 2024, 7, e2424793. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, C.; Zheng, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Hao, J.; Zhao, X.; Yi, K.; Shi, L.; Kang, C.; et al. Virus-like nanoparticle as a co-delivery system to enhance efficacy of CRISPR/Cas9-based cancer immunotherapy. Biomaterials 2020, 258, 120275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghamiri, S.; Talaei, S.; Ghavidel, A.A.; Zandsalimi, F.; Masoumi, S.; Hafshejani, N.H.; Jajarmi, V. Nanoparticles-mediated CRISPR/Cas9 delivery: Recent advances in cancer treatment. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Wu, S.; Huang, D.; Li, C. Complications and comorbidities associated with antineoplastic chemotherapy: Rethinking drug design and delivery for anticancer therapy. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2024, 14, 2901–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, R.; Zhen, S.; Zhang, C.; Moon, J.-Y.; Bteich, F.; Kuang, C. Impact of adjuvant chemotherapy on outcomes after curative-intent surgery for biliary tract cancer: A 10-year retrospective single-center study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, e16273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, D.J.; Eroglu, Z.; Brockstein, B.; Poklepovic, A.S.; Bajaj, M.; Babu, S.; Hallmeyer, S.; Velasco, M.; Lutzky, J.; Higgs, E.; et al. Pembrolizumab Plus Ipilimumab Following Anti-PD-1/L1 Failure in Melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 2647–2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helena, A.Y.; et al. Effect of osimertinib and bevacizumab on progression-free survival for patients with metastatic EGFR-mutant lung cancers: a phase 1/2 single-group open-label trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020, 6, 1048–1054. [Google Scholar]

- O'Shaughnessy, J.; Graham, C.L.; Whitworth, P.; Beitsch, P.D.; Osborne, C.R.C.; Rahman, R.L.; Brown, E.A.; Gold, L.P.; Johnson, N.M.; Brufsky, A.; et al. Association of MammaPrint index and 3-year outcome of patients with HR+HER2- early-stage breast cancer treated with chemotherapy with or without anthracycline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarneri, V.; Griguolo, G.; Miglietta, F.; Conte, P.; Dieci, M.; Girardi, F. Survival after neoadjuvant therapy with trastuzumab–lapatinib and chemotherapy in patients with HER2-positive early breast cancer: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. ESMO Open 2022, 7, 100433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, B.; Loong, H.; Summers, Y.; Thomas, Z.; French, P.; Lin, B.; Sashegyi, A.; Wolf, J.; Yang, J.-H.; Drilon, A. Correlation between treatment effects on response rate and progression-free survival and overall survival in trials of targeted therapies in molecularly enriched populations. ESMO Open 2022, 7, 100398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsimberidou, A.; Fu, S.; Hong, D.; Piha-Paul, S.; Naing, A.; Rodon, J.; Yap, T.; Karp, D.; Dumbrava, E.; Heymach, J.; et al. 638P Final results of IMPACT 2, a randomized study evaluating molecular profiling and targeted agents in metastatic cancer at MD Anderson Cancer Center. Ann. Oncol. 2024, 35, S506–S507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neagu, A.-N.; Bruno, P.; Johnson, K.R.; Ballestas, G.; Darie, C.C. Biological Basis of Breast Cancer-Related Disparities in Precision Oncology Era. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldea, M.; Andre, F.; Marabelle, A.; Dogan, S.; Barlesi, F.; Soria, J.-C. Overcoming Resistance to Tumor-Targeted and Immune-Targeted Therapies. Cancer Discov. 2021, 11, 874–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.; Mayer, T.; Li, S.; Qureshi, S.; Farooq, F.; Vuylsteke, P.; Ralefala, T.; Marlink, R. Advancing oncology drug therapies for sub-Saharan Africa. PLOS Glob. Public Heal. 2023, 3, e0001653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twahir, M.; Oyesegun, R.; Yarney, J.; Gachii, A.; Edusa, C.; Nwogu, C.; Mangutha, G.; Anderson, P.; Benjamin, E.; Müller, B.; et al. Real-world challenges for patients with breast cancer in sub-Saharan Africa: a retrospective observational study of access to care in Ghana, Kenya and Nigeria. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e041900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.; Saraswat, A.; Wei, Z.; Agrawal, M.Y.; Dukhande, V.V.; Reznik, S.E.; Patel, K. Development of Dual ARV-825 and Nintedanib-Loaded PEGylated Nano-Liposomes for Synergistic Efficacy in Vemurafnib-Resistant Melanoma. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Tsui, S.T.; Liu, C.; Song, Y.; Liu, D. EGFR C797S mutation mediates resistance to third-generation inhibitors in T790M-positive non-small cell lung cancer. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2016, 9, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helena, A.Y.; et al. Acquired resistance of EGFR-mutant lung cancer to a T790M-specific EGFR inhibitor: emergence of a third mutation (C797S) in the EGFR tyrosine kinase domain. JAMA Oncol. 2015, 1, 982–984. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D. Cancer biomarkers for targeted therapy. Biomark. Res. 2019, 7, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, P.; Mao, A.; Qiu, W.; Li, G. Improvement of Cancer Prevention and Control: Reflection on the Role of Emerging Information Technologies. J. Med Internet Res. 2024, 26, e50000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesse, B.W.; Kwasnicka, D.; Ahern, D.K. Emerging digital technologies in cancer treatment, prevention, and control. Transl. Behav. Med. 2021, 11, 2009–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, S.W.; Tang, C.; Tan, X.; Srivastava, S. Liquid biopsy for early cancer detection: technological revolutions and clinical dilemma. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2024, 24, 937–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, W.; Hurley, J.; Roberts, D.; Chakrabortty, S.; Enderle, D.; Noerholm, M.; Breakefield, X.; Skog, J. Exosome-based liquid biopsies in cancer: opportunities and challenges. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, 466–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, D.; Khan, N.U.; Gu, W.; Lei, H.; Goel, A.; Chen, T. Informatics strategies for early detection and risk mitigation in pancreatic cancer patients. Neoplasia 2025, 60, 101129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolfo, C.; Russo, A. Moving Forward Liquid Biopsy in Early Liver Cancer Detection. Cancer Discov. 2023, 13, 532–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, D.A., Jr.; Lennerz, J.K. Technology and future of multi-cancer early detection. Life 2024, 14, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passaro, A.; Al Bakir, M.; Hamilton, E.G.; Diehn, M.; André, F.; Roy-Chowdhuri, S.; Mountzios, G.; Wistuba, I.I.; Swanton, C.; Peters, S. Cancer biomarkers: Emerging trends and clinical implications for personalized treatment. Cell 2024, 187, 1617–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zhao, H. Next-generation sequencing in liquid biopsy: cancer screening and early detection. Hum. Genom. 2019, 13, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molla, G.; Bitew, M. Revolutionizing Personalized Medicine: Synergy with Multi-Omics Data Generation, Main Hurdles, and Future Perspectives. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Poulos, R.C.; Liu, J.; Zhong, Q. Machine learning for multi-omics data integration in cancer. iScience 2022, 25, 103798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ma, W.; Huang, Z.; Liu, K.; Feng, Z.; Zhang, L.; Li, D.; Mo, T.; Liu, Q. Research and application of omics and artificial intelligence in cancer. Phys. Med. Biol. 2024, 69, 21TR01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, I.-W.; Vo, H.H.; Chen, Y.-S.; Baysal, M.A.; Kahle, M.; Johnson, A.; Tsimberidou, A.M. Precision Oncology: Evolving Clinical Trials across Tumor Types. Cancers 2023, 15, 1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

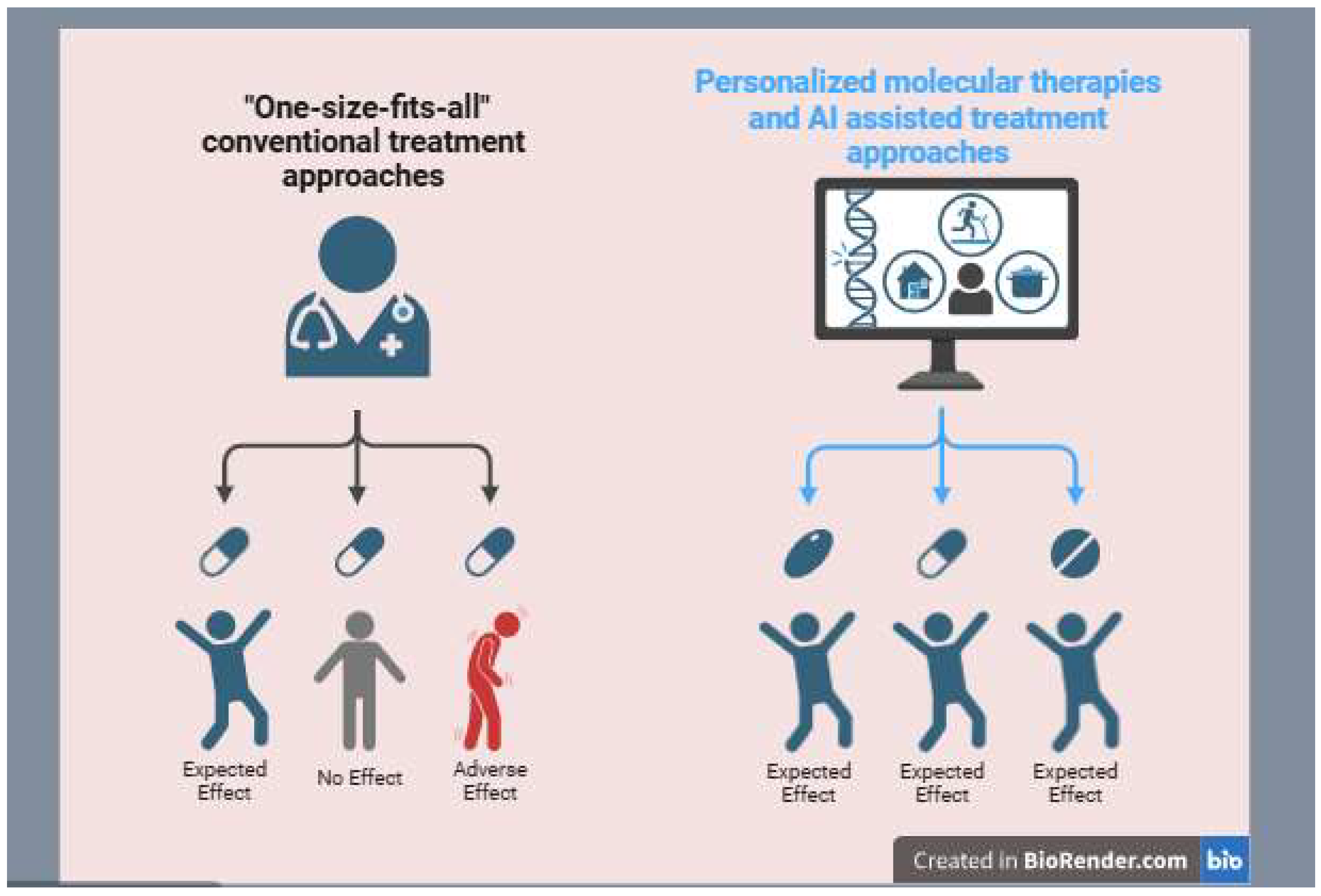

| Aspect | Conventional diagnosis | Advanced diagnosis |

|---|---|---|

| Techniques | - Biopsy (tissue examination) - Imaging (X-ray, CT, MRI, Ultrasound) - Blood tests (tumor markers like PSA, CA-125) |

-Liquid biopsy (circulating tumor DNA, CTCs) - Next-generation sequencing (NGS) - AI-powered imaging analysis - Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) - multi-omics profiling (genomics, proteomics, metabolomics) |

| Accuracy | Moderate, requires invasive procedures and may not detect early-stage cancer | High, enables early detection and real-time monitoring of tumor evolution |

| Personalization | “One-size-fits-all” approach, based on histology and general tumor characteristics | Highly personalized, identifying genetic mutations and molecular signatures for tailored treatment |

| Speed of Results | Can take weeks due to tissue processing and pathology | Faster, especially with AI-driven and liquid biopsy techniques |

| Biomarker types | Purpose | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic biomarker | Detect cancer presence | PSA, CA-125, CTCs |

| Prognostic biomarker | Predict cancer outcome | HER2, Ki-67, TP53 mutations |

| Predictive biomarker | Guide treatment selection | EGFR mutations, PD-L1 expression |

| Monitoring biomarker | Track disease progression | CEA, ctDNA, imaging-based markers |

| Cancer types | Biomarker Types | Monitoring Biomarker |

|---|---|---|

| Prostate cancer | Diagnostic (PSA) | Monitoring PSA levels |

| Ovarian cancer | Diagnostic (CA-125) | Monitoring CA-125 levels |

| Breast cancer | Predictive (HER2) | Monitoring HER2 levels |

| Lung cancer | Diagnostic (Early CDT-Lung) | Monitoring CTDNA |

| Colorectal cancer | Diagnostic (CEA) | Monitoring CEA levels |

| Melanoma | Prognostic (BRAF mutations) | Monitoring LDH levels |

| Pancreatic cancer | Diagnostic (CA 19-9) | Monitoring CA 19-9 levels |

| Liver cancer | Diagnostic (AFP) | Monitoring AFP levels |

| Bladder cancer | Diagnostic (NMP22) | Monitoring NMP22 levels |

| Testicular cancer | Diagnostic (AFP, hCG) | Monitoring AFP levels |

| Aspect | Conventional Treatment | Advanced Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Techniques | - Surgery (tumor removal) - Chemotherapy - Radiation therapy |

- Targeted therapy (EGFR inhibitors, BRAF inhibitors) - Immunotherapy (CAR-T cells, checkpoint inhibitors) - CRISPR gene editing - Personalized medicine (based on genetic profiling) - AI-driven drug discovery |

| Specificity | Non-specific, affecting both cancerous and healthy cells | Highly specific, targeting cancer cells while minimizing damage to normal cells |

| Side Effects | High, including nausea, hair loss, immune suppression | Reduced, as treatments are more focused and personalized |

| Effectiveness | Variable, depends on cancer type and stage | Higher efficacy in many cases, especially for resistant or rare cancers |

| Recurrence Rate | Often high due to incomplete tumor eradication | Lower, as targeted treatments disrupt cancer pathways effectively |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).