Submitted:

28 March 2025

Posted:

31 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Clinical Presentation

3. Radiographic Presentation

4. Mirel Classification

| Variable | Score | ||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Site of lesion | Upper limb | Lower limb | Trochanteric region |

| Size of lesion (cortical thickness) | <1/3rd diameter | 1/3-2/3rd diameter | >2/3rd diameter |

| Nature of lesion | Blastic | Mixed | Lytic |

| Pain | Mild | Moderate | Functional |

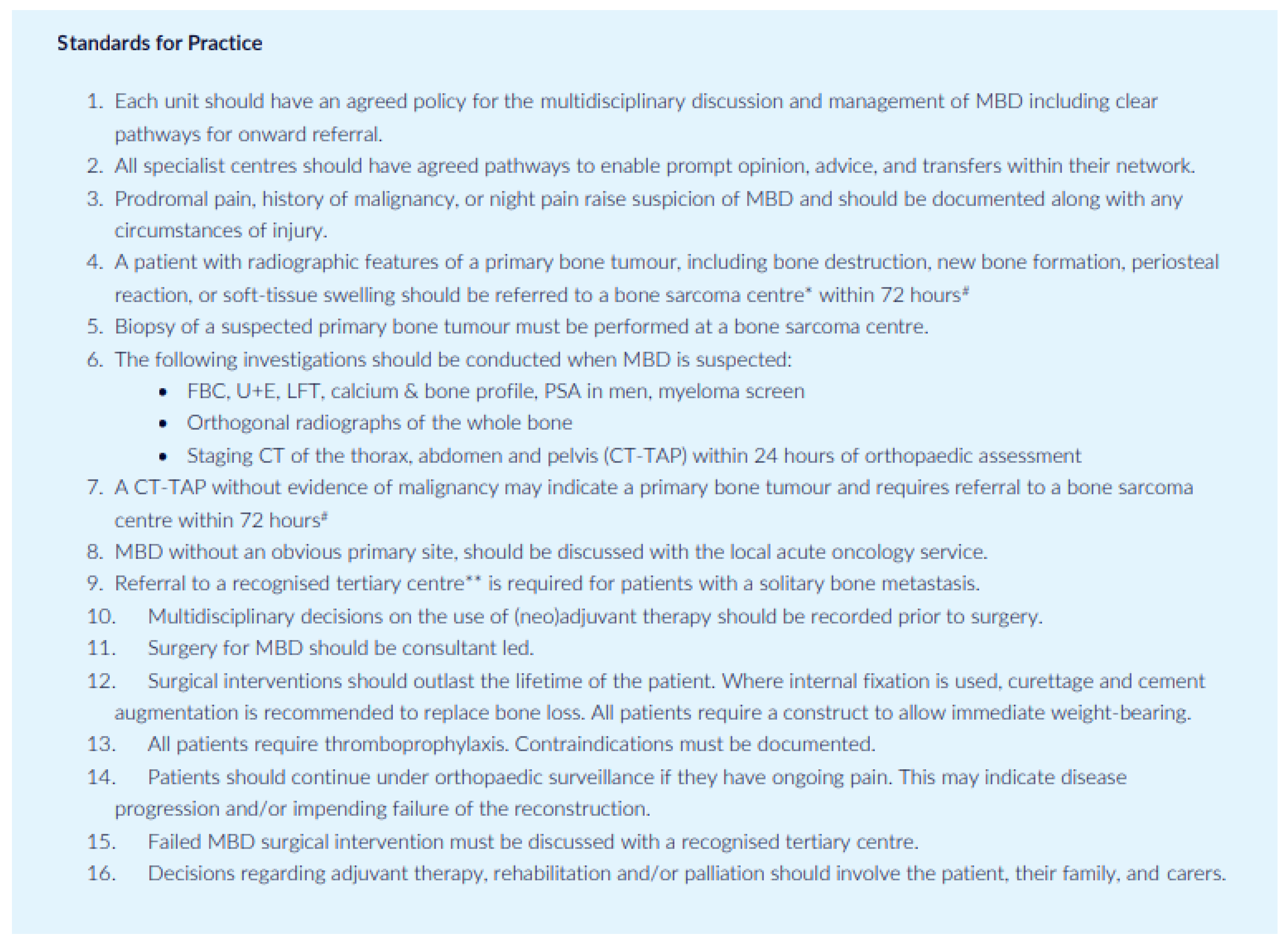

5. Current Management Approach

6. Biopsy

7. Tertiary versus Non-Specialised Centres

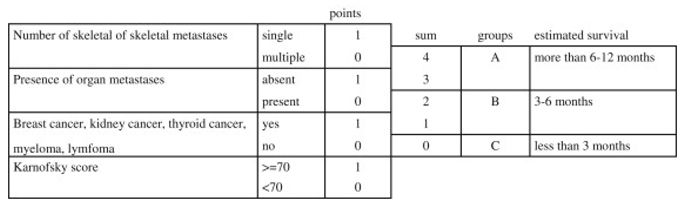

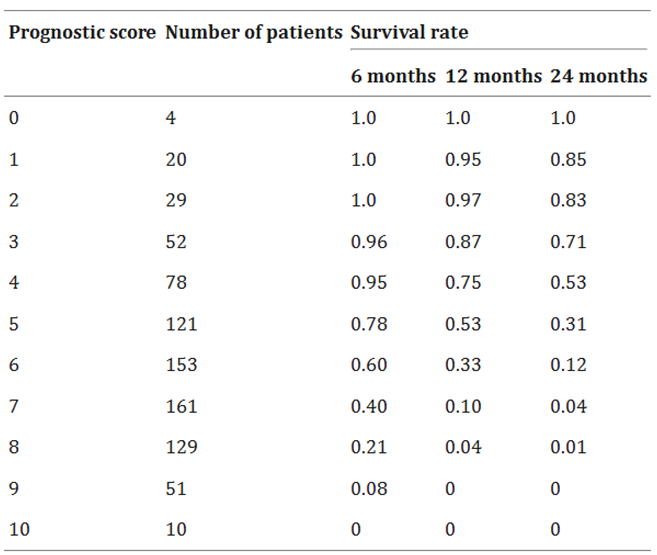

8. Prognosis

9. Potential Future Treatment Options

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jayarangaiah A, Theetha Kariyanna P. Bone Metastasis [Internet]. PubMed. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507911/.

- Chansky, HA. Metastatic Bone Disease: Practice Essentials, Pathophysiology and Etiology, Epidemiology [Internet]. Medscape.com. Medscape; 2024 [cited 2025 Mar 23]. Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1253331-overview#a7?form=fpf.

- Storm HH, Kejs AMT, Engholm G, Tryggvadóttir L, Klint A, Bray F, et al. Trends in the overall survival of cancer patients diagnosed 1964-2003 in the Nordic countries followed up to the end of 2006: the importance of case-mix. Acta oncologica (Stockholm, Sweden) [Internet] 2010, 49, 713–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers DL, Raad M, Rivera JA, Wedin R, Laitinen M, Sørensen MS, et al. Life Expectancy After Treatment of Metastatic Bone Disease: An International Trend Analysis. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons [Internet] 2024, 32, e293–301. [Google Scholar]

- BOA. Management of Metastatic Bone Disease (MBD) [Internet]. BOA/BOOS; 2022 [cited 2025 Mar 23]. Available from: file:///C:/Users/7952080/AppData/Local/Temp/MicrosoftEdgeDownloads/00a0ed89-45d2-480a-a0a6-8b627fba7182/BOAST-Metastatic-Bone-Disease.pdf.

- About secondary bone cancer | Secondary cancer | Cancer Research UK [Internet]. Cancerresearchuk.org. 2017. Available from: https://www.cancerresearchuk.

- Zhang J, Cai D, Hong S. Prevalence and prognosis of bone metastases in common solid cancers at initial diagnosis: a population-based study. BMJ Open [Internet] 2023, 13, e069908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan C, Stoltzfus KC, Horn S, Chen H, Louie AV, Lehrer EJ, et al. Epidemiology of bone metastases. Bone 2020, 115783. [Google Scholar]

- BOOS & BOA. Metastatic Bone Disease: A Guide to Good Practice [Internet]. Tillman, Ashford, editors. BOOS/BOA; 2015 [cited 2025 Mar 23]. Available from: https://baso.org.uk/media/61543/boos_mbd_2016_boa.pdf.

- So A, Chin J, Fleshner N, Saad F. Management of skeletal-related events in patients with advanced prostate cancer and bone metastases: Incorporating new agents into clinical practice. Canadian Urological Association Journal [Internet] 2012, 6, 465–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim A, Scher N, Williams G, Sridhara R, Li N, Chen G, et al. Approval Summary for Zoledronic Acid for Treatment of Multiple Myeloma and Cancer Bone Metastases. Clinical Cancer Research [Internet] 2003, 9, 2394–2399. [Google Scholar]

- Archer JE, Chauhan GS, Dewan V, Osman K, Thomson C, Nandra RS, et al. The British Orthopaedic Oncology Management (BOOM) audit. The bone & joint journal 2023, 105, 1115–1122. [Google Scholar]

- CKS is only available in the UK [Internet]. NICE. Available from: https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/hypercalcaemia/background-information/causes/.

- Gaillard, F. Bone metastases | Radiology Reference Article | Radiopaedia.org [Internet]. Radiopaedia. Available from: https://radiopaedia.org/articles/bone-metastases-1?

- Macedo F, Ladeira K, Pinho F, Saraiva N, Bonito N, Pinto L, et al. Bone metastases: an Overview. Oncology Reviews [Internet] 2017, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Jayarangaiah A, Theetha Kariyanna P. Bone Metastasis [Internet]. PubMed. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507911/.

- Douglas Phillips C, Pope TL, Jones JE, Keats TE, Hunt MacMillan R. Nontraumatic avulsion of the lesser trochanter: a pathognomonic sign of metastatic disease? Skeletal Radiology 1988, 17, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. -L. Rouvillain, R. Jawahdou, Blanco OL, A. Benchikh-el-Fegoun, E. Enkaoua, Uzel M. Isolated lesser trochanter fracture in adults: An early indicator of tumor infiltration. Orthopaedics & Traumatology Surgery & Research 2011, 97, 217–220. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, DJ. Mirels classification (pathological fracture risk) [Internet]. Radiopaedia. Radiopaedia.org; 2024. Available from: https://radiopaedia.org/articles/mirels-classification-pathological-fracture-risk-1?lang=gb.

- Mirels, H. The Classic: Metastatic Disease in Long Bones A Proposed Scoring System for Diagnosing Impending Pathologic Fractures. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 2003, 415, S4–S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosher ZA, Patel H, Ewing MA, Niemeier TE, Hess MC, Wilkinson EB, et al. Early Clinical and Economic Outcomes of Prophylactic and Acute Pathologic Fracture Treatment. Journal of Oncology Practice 2019, 15, e132–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behnke N, Baker D. Prophylactic Fixation Of Impending Pathologic Fractures: In-Hospital Cost And Complication Analysis As Compared To Acute Fracture Fixation [Internet]. [cited 2025 Mar 23]. Available from: https://www.isols-msts.org/abstracts/files/abstracts-podium/isols-msts-abstract-140.pdf.

- Impending Fracture & Prophylactic Fixation - Pathology - Orthobullets [Internet]. www.orthobullets.com. Available from: https://www.orthobullets. 8002.

- Mirel’s classification to predict possible pathological fracture if boney metastasis [Internet]. Gpnotebook.com. 2018 [cited 2025 Mar 23]. Available from: https://gpnotebook.com/en-GB/pages/oncology/mirels-classification-to-predict-possible-pathological-fracture-if-boney-metastasis.

- Jawad MU, Scully SP. In Brief: Classifications in Brief. Clinical Orthopaedics & Related Research 2010, 468, 2825–2827. [Google Scholar]

- Harrington, KD. Impending pathologic fractures from metastatic malignancy: evaluation and management. Instructional course lectures [Internet] 1986, 35, 357–381. [Google Scholar]

- Knipe H, Bell D, Worsley C. Harrington criteria (pathological fracture risk). Radiopaediaorg [Internet]. 2015 Nov 1 [cited 2025 Mar 23]; Available from: https://radiopaedia.org/articles/harrington-criteria-pathological-fracture-risk-1.

- Rizzo SE, Kenan S. Pathologic Fractures [Internet]. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. StatPearls Publishing; 2020. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559077/.

- Harvie P, Whitwell D. Metastatic bone disease. Bone & Joint Research 2013, 2, 96–101. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell, P. Metastatic Disease of Extremity - Pathology - Orthobullets [Internet]. Orthobullets.com. 2019. Available from: https://www.orthobullets.com/pathology/8045/metastatic-disease-of-extremity.

- Selvaggi G, Scagliotti GV. Management of bone metastases in cancer: a review. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology [Internet] 2005, 56, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J. Pathological fracture | Radiology Reference Article | Radiopaedia.org [Internet]. Radiopaedia. Available from: https://radiopaedia.org/articles/pathological-fracture?

- Marshall RA, Mandell JC, Weaver MJ, Ferrone M, Sodickson A, Khurana B. Imaging Features and Management of Stress, Atypical, and Pathologic Fractures. RadioGraphics 2018, 38, 2173–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukamoto S, Kido A, Tanaka Y, Facchini G, Peta G, Rossi G, et al. Current Overview of Treatment for Metastatic Bone Disease. Current Oncology 2021, 28, 3347–3372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Felice F, Piccioli A, Musio D, Tombolini V. The role of radiation therapy in bone metastases management. Oncotarget [Internet] 2017, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Saarto T, Janes R, Tenhunen M, Kouri M. Palliative radiotherapy in the treatment of skeletal metastases. European Journal of Pain 2002, 6, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haber, Z. Transarterial Embolization of Bone Metastases. Techniques in Vascular and Interventional Radiology 2023, 26, 100883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma J, Tullius T, Van Ha TG. Update on Preoperative Embolization of Bone Metastases. Seminars in Interventional Radiology 2019, 36, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geraets SEW, Bos PK, van der Stok J. Preoperative embolization in surgical treatment of long bone metastasis: a systematic literature review. EFORT Open Reviews 2020, 5, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acuña AJ, Vijayakumar G, Buac NP, Colman MW, Gitelis S, Blank AT. The effect of timing between preoperative embolization and surgery: A retrospective analysis of hypervascular bone metastases. Journal of Surgical Oncology 2023, 129, 416–423. [Google Scholar]

- Sun S, Lang EV. Bone Metastases from Renal Cell Carcinoma: Preoperative Embolization. Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology 1998, 9, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake MT, Clarke BL, Khosla S. Bisphosphonates: Mechanism of Action and Role in Clinical Practice. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 2008, 83, 1032–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gralow J, Tripathy D. Managing Metastatic Bone Pain: The Role of Bisphosphonates. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 2007, 33, 462–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CKS is only available in the UK [Internet]. NICE. Available from: https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/hypercalcaemia/management/unconfirmed-cause/.

- CKS is only available in the UK [Internet]. NICE. Available from: https://cks.nice.org.

- Dental Management of Patients Prescribed Bisphosphonates -Clinical Guidance (Produced in conjunction with the Dental LPN for Shropshire and Staffordshire) [Internet]. 2015. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/mids-east/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2015/03/bisphosphonates-guidelines-2015.

- BNF is only available in the UK [Internet]. NICE. Available from: https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drugs/denosumab/#indications-and-dose.

- NICE. Denosumab for the prevention of skeletal[1]related events in adults with bone metastases from solid tumours [Internet]. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2012 [cited 2025 Mar 20]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.

- Overview | Denosumab for the prevention of skeletal-related events in adults with bone metastases from solid tumours | Guidance | NICE [Internet]. www.nice.org.uk. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta265.

- NICE. Risk assessment foR Venous thRomboembolism (Vte) [Internet]. 2010. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng89/resources/department-of-health-vte-risk-assessment-tool-pdf-4787149213.

- CKS is only available in the UK [Internet]. NICE. Available from: https://cks.nice.org.

- Kulkarni A, Grimer R, Carter S, Tillman R, Abudu A. How bad is a whoops procedure? – answers from a case matched series. Orthop Procs. 2005, 87, 3. [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. Tumor Markers [Internet]. National Cancer Institute. 2019. Available from: https://www.cancer.

- Motoo Y, Watanabe H, Sawabu N. [Sensitivity and specificity of tumor markers in cancer diagnosis]. Nihon Rinsho Japanese Journal of Clinical Medicine [Internet] 1996, 54, 1587–1591. [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. Tumor Markers in Common Use - National Cancer Institute [Internet]. www.cancer.gov. 2019. Available from: https://www.cancer.

- Ratasvuori M, Wedin R, Keller J, Nottrott M, Zaikova O, Bergh P, et al. Insight opinion to surgically treated metastatic bone disease: Scandinavian Sarcoma Group Skeletal Metastasis Registry report of 1195 operated skeletal metastasis. Surgical Oncology. 2013, 22, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Table - PMC [Internet]. Cancer Med. 2014 Jul 10;3(5):1359–1367. Nih.gov. 2025 [cited 2025 Mar 23]. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4302686/table/tbl4/. [CrossRef]

- Katagiri H, Okada R, Takagi T, Takahashi M, Murata H, Harada H, et al. New prognostic factors and scoring system for patients with skeletal metastasis. 2014, 3, 1359–1367.

- Table – PMC. Cancer Med. 2014 Jul 10;3(5):1359–1367. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4302686/table/tbl5/. [CrossRef]

- Rai, P. Current surgical management of metastatic pathological fractures of the femur: A multicentre snapshot audit [Internet]. Clinical Key. European Journal of Surgical Oncology, 2020-08-01, Volume 46, Issue 8, Pages 1491-1495; 2020. Available from: https://www.clinicalkey.com/#!/content/playContent/1-s2.0-S0748798320301281?returnurl=https:%2F%2Flinkinghub.elsevier.com%2Fretrieve%2Fpii%2FS0748798320301281%3Fshowall%3Dtrue&referrer=https:%2F%2Fpubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov%2F.

- Winnard PT, Farhad Vesuna, Bol GM, Gabrielson KL, Chenevix-Trench G, Ter ND, et al. Targeting RNA Helicase DDX3X with a Small Molecule Inhibitor for Breast Cancer Bone Metastasis Treatment. Cancer Letters. 2024, 604, 217260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- RK-33 [Internet]. Hopkinsmedicine.org. 2018. Available from: https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/news/articles/2018/05/rk-33.

- Experimental Cancer Drug Eliminates Bone Metastases Caused by Breast Cancer in Lab Models [Internet]. Hopkinsmedicine.org. 2024. Available from: https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/news/newsroom/news-releases/2024/10/experimental-cancer-drug-eliminates-bone-metastases-caused-by-breast-cancer-in-lab-models.

- MR Guided Focused Ultrasound [Internet]. stanfordhealthcare.org. Available from: https://stanfordhealthcare.org/medical-treatments/m/mr-guided-focused-ultrasound.html.

- Han X, Huang R, Meng T, Yin H, Song D. The Roles of Magnetic Resonance-Guided Focused Ultrasound in Pain Relief in Patients With Bone Metastases: A Systemic Review and Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in oncology 2021, 11. [Google Scholar]

| Tumour Marker | Malignancy |

|---|---|

| Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) | Liver cancer, ovarian cancer, and germ cell tumours |

| Beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (Beta-hCG) | Choriocarcinoma and germ cell tumours |

| CA19-9 | Pancreatic, gallbladder, bile duct, and gastric cancers |

| CA-125 | Ovarian cancer |

| Calcitonin | Medullary Thyroid Cancer |

| Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) | Colorectal cancer, breast and ovarian cancer |

| CD20 | Non-Hodgkin lymphoma |

| Oestrogen receptor (ER)/progesterone receptor (PR) | Breast cancer |

| 5-HIAA | Carcinoid tumors |

| Gastrin | Gastrin-producing tumour (gastrinoma) |

| Immunoglobulins | Multiple myeloma and Waldenström macroglobulinemia |

| Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) | Prostate cancer |

| Thyroglobulin | Thyroid cancer |

| Prognostic factor | Score | |

|---|---|---|

| Primary site | ||

| Slow growth | Hormone-dependent breast and prostate cancer, thyroid cancer, multiple myeloma, and malignant lymphoma | 0 |

| Moderate growth | Lung cancer treated with molecularly targeted drugs, hormone-independent breast and prostate cancer, renal cell carcinoma, endometrial and ovarian cancer, sarcoma, and others | 2 |

| Rapid growth | Lung cancer without molecularly targeted drugs, colorectal cancer, gastric cancer, pancreatic cancer, head and neck cancer, oesophageal cancer, other urological cancers, melanoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, gall bladder cancer, cervical cancer, and cancers of unknown origin | 3 |

| Visceral metastasis | Nodular visceral or cerebral metastasis | 1 |

| Disseminated metastasis (Pleural, peritoneal, or leptomeningeal dissemination.) | 2 | |

| Laboratory data | Abnormal (CRP ≥ 0.4 mg/dL, LDH ≥ 250 IU/L, or serum albumin <3.7 g/dL.) | 1 |

| Critical (platelet <100,000/μL, serum calcium ≥10.3 mg/dL, or total bilirubin ≥1.4) | 2 | |

| ECOG PS | 3 or 4 | 1 |

| Previous chemotherapy | Score if Yes | 1 |

| Multiple skeletal metastases | Score if Yes | 1 |

| Total | 10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).