1. Introduction

Methicillin-resistant

Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is a major global health issue, known for causing a wide range of infections from minor skin issues to severe systemic illnesses such as sepsis [

1,

2]. Resistance to methicillin and other β-lactam antibiotics, including penicillins and cephalosporins, has made treatment more difficult, resulting in higher rates of illness and death, longer hospital stays, and increased healthcare costs [

3,

4]. This resistance, largely driven by the mecA gene, means that many antibiotics that were once effective no longer work against MRSA infections [

5,

6]. Invasive MRSA infections carry significantly higher morbidity and mortality than methicillin-sensitive S.

aureus (MSSA) infections. For example, MRSA bacteremia is associated with prolonged hospital stays, elevated healthcare costs, and roughly double the mortality risk compared to MSSA [

7]. Reviews and meta-analyses have repeatedly shown that MRSA is common in many healthcare settings around the world, highlighting the need to understand its spread [

3,

8]. For example, a meta-analysis focused on elderly care centers found a global MRSA prevalence of 14.69%, underscoring how widespread this pathogen is [

8]. Moreover, the differences between hospital-associated (HA-MRSA) and community-associated (CA-MRSA) strains have become less clear, further complicating the epidemiological picture. Said et al. (2023) demonstrated a clear lineage divergence from CA-MRSA patterns in younger individuals to HA-MRSA profiles in seniors, emphasizing age-specific host-selection from a common MSSA ancestor [

9].

Tertiary care hospitals play a key role in the battle against MRSA. These hospitals, which care for many high-risk patients and perform numerous invasive procedures, as well as use a large amount of antibiotics, are particularly prone to MRSA transmission [

10]. Intensive care units (ICUs) within these hospitals are even more vulnerable due to the critically ill state of patients, who often have weakened immune systems, and the common use of medical devices that can serve as entry points for infection [

10]. Research has shown that MRSA infection rates are usually higher in ICUs compared to non-ICU settings, indicating a need for focused interventions in these areas [

11]. The severe infections caused by MRSA in tertiary care settings—including bloodstream infections, pneumonia, surgical site infections, and skin and soft tissue infections—can lead to serious health consequences and place a significant burden on both patients and the healthcare system [

12].

It is essential to understand how MRSA infections vary by age and gender to develop effective prevention and control strategies [

3]. Different age groups may have varying risks of MRSA due to factors like underlying health conditions, changes in immune function, and differing levels of exposure to healthcare environments. For instance, the elderly are often reported to have higher rates of MRSA-related hospitalizations [

13]. Recent evidence also points to differences between genders in MRSA prevalence and outcomes [

3,

14]. While many studies report higher MRSA carriage and bloodstream infection rates among males [

15,

16], others have observed notable MRSA rates in certain female populations, underlining the complexity of these patterns. Such conflicting findings suggest that local demographic factors—ranging from behavioral to biological influences—can affect MRSA prevalence in distinct ways, necessitating further targeted research.

Studying MRSA profiles separately in ICU and non-ICU settings within tertiary hospitals is crucial because of the unique clinical environments and patient populations in these areas [

17]. ICUs often have a higher rate of multidrug-resistant organisms, including MRSA, due to the factors already mentioned—critical illness, frequent use of invasive devices, and strong selective pressure from broad-spectrum antibiotics [

18]. Infection rates of healthcare-associated MRSA are higher in ICUs than in general wards [

19]. Furthermore, the types of infections and patterns of antibiotic use can vary greatly between these units, which may influence the characteristics of MRSA strains seen in each setting. Comparing MRSA profiles between these areas can uncover important differences in epidemiology and resistance patterns within the same hospital, thereby helping to tailor specific infection control measures and antibiotic guidelines.

This observational study aims to provide a detailed understanding of age- and gender-specific MRSA and CA-MRSA profiles, along with their associated disease patterns, within our tertiary care hospital, while also comparing ICU and non-ICU settings. By analyzing data from 253 S. aureus isolates, the study seeks to determine the prevalence of MRSA and CA-MRSA across different age and gender groups, compare these profiles between ICU and non-ICU patients, and describe the related disease patterns and antibiotic susceptibility profiles. Focusing on a single tertiary care hospital can generate valuable local epidemiological data that may guide targeted infection control and treatment strategies for our patient population and the specific MRSA strains present

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design and Setting

This clinical surveillance study was conducted at King Salman Specialist Hospital (KSSH), Ha’il from May 2023 to March 2025) as part of a scheduled MRSA surveillance program for elimination of this Superbug and all related lineages. This is because KSSH is a major referral center with diverse patient populations, including both general wards and specialized intensive care units (ICUs). It has been accredited by the Saudi Central Board for Accreditation of Healthcare Institutions (CBAHI)-Ref.no. HAL/MOH/HO5/34213 and along with the Ha’il Health Regional Laboratory (HHRL) which is also certified and accredited by the CBAHI)-Code 2739, together they make up a major cluster for healthcare diagnostic centers that receive samples for testing. All patients who presented with clinically suspected Staphylococcus aureus infections were included. However, in-line with the major global efforts for MRSA eradication programs since the pandemic in 2005, we focused on all hospital units prone to MRSA infection sources and specimens from bloodstream, respiratory, and skin and soft tissue infections whether from the microbiology laboratory or disease characteristic directly from clinical unit records. All sampling, identification, and clinical profiles were according to the ISO standard protocols in-place, as explained below.

Patient Enrollment, Sample Collection, and Definition of Clinical Categories

A total of 253 non-duplicate S. aureus isolates were obtained from patients of varying ages and both genders. Patients were categorized into ICU or non-ICU groups based on their admission status at the time of sample collection. Patients of any gender and age who were admitted with a suspected S. aureus infection were eligible for inclusion. Only patients with a laboratory-confirmed S. aureus isolate obtained from a clinical specimen, such as blood, respiratory secretions, or wound swabs, were included. However, certain exclusions were applied. Repeat isolates from the same patient or from the same infection site that exhibit identical diagnostic, genetic, or disease characteristics within a short interval (e.g., 14 days) were not considered to avoid redundancy. Additionally, samples that failed to grow on subculture or that exhibited polymicrobial contamination, or non-specific nuc-gene profiles, making it difficult to clearly identify S. aureus, at species or strain level, were excluded from the final analysis. All clinical specimens were collected using standard sterile techniques and transported promptly to the microbiology laboratory to maintain sample viability. The study adhered to established microbiological protocols for sample handling and processing. Clinical specimens—including blood, respiratory, wound, and other site samples—were collected using sterile techniques. All samples taken in different units that the laboratory was adequately transported promptly to the microbiology laboratory under appropriate conditions to maintain viability and sterility. Patients were grouped by age 10–29, 30–49, 50–69, 70+ and gender male, female. Infections were classified by specimen source (blood, respiratory, wounds, or other sites). ICU and non-ICU status was determined at the time of culture collection.

Laboratory Identification, Molecular Characterizations, and Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing

Routine bacteriological methods were employed for the initial identification of Staphylococcus aureus isolates. All clinical specimens were inoculated onto standard culture media, including blood agar, mannitol salt agar, and Baird-Parker agar, and incubated at 37°C for 18–24 hours. Isolates showing typical colony morphology were subjected to biochemical testing, and molecular confirmation was carried out using the nuc gene, which is specific for S. aureus.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed using automated systems, namely the BD Phoenix (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), VITEK 2 (bioMérieux, Marcy-l'Étoile, France), and MicroScan Plus (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). The testing procedures and interpretive criteria were based on the standards provided by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI, M100-26) (Patel et al., 2021 Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing CLSI. 26th Edition; at:

www.clsi.org).

Zone diameters and minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were interpreted accordingly, and where necessary, additional agar diffusion testing was performed to confirm resistance to oxacillin and other beta-lactams. Standard quality control strains, such as S. aureus ATCC 25923, were used consistently to ensure the accuracy and reproducibility of results.

Isolates showing phenotypic resistance to cefoxitin and/or oxacillin were classified as methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), in accordance with CLSI guidelines. To further confirm methicillin resistance and to avoid misclassification due to borderline or inducible resistance, molecular detection was conducted using the GeneXpert® Dx System (Cepheid, USA). This real-time PCR platform allowed for direct detection of key genetic markers, including mecA, nuc, and spa, as well as SCCmec elements. The system utilizes an integrated, closed-cartridge format that automates sample purification, amplification, and detection, minimizing the risk of contamination and reducing bias introduced by in vitro subculturing. Direct molecular testing from clinical specimens ensured the accurate identification of MRSA strains and preserved the genetic integrity of the original isolate.

All isolates confirmed as resistant to either cefoxitin or oxacillin and carrying the mecA gene were categorized as MRSA. Susceptible isolates without mecA were classified as methicillin-sensitive S. aureus (MSSA). Based on their resistance profiles, MRSA isolates were further divided into hospital-associated MRSA (HA-MRSA) and community-associated MRSA (CA-MRSA). HA-MRSA strains were typically resistant to both beta-lactam antibiotics and at least one non–beta-lactam antimicrobial category, reflecting a multidrug-resistant phenotype. In contrast, CA-MRSA strains were usually resistant to beta-lactams but remained susceptible to non–beta-lactam agents such as clindamycin, trimethoprim, and tetracycline.

The antibiotic panel tested included agents across multiple categories: beta-lactams (cefoxitin, oxacillin, ampicillin, penicillin, and cefotaxime), fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, moxifloxacin, and ofloxacin), aminoglycosides (gentamicin), macrolides and lincosamides (erythromycin and clindamycin), glycopeptides (vancomycin and teicoplanin), oxazolidinones (linezolid), lipopeptides (daptomycin), tetracyclines (tetracycline and tigecycline), and other agents including trimethoprim, nitrofurantoin, rifampicin, mupirocin, and ceftaroline. Classification of isolates as multidrug-resistant (MDR), extensively drug-resistant (XDR), or pan-drug resistant (PDR) was performed according to definitions established by the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), as described by Magiorakos et al. [

20]. These classifications were based on acquired resistance across different antimicrobial categories, excluding intrinsic resistance mechanisms.

Direct Multi-Gene Molecular Detection of S. aureus Lineages by GeneXpert System

A major advantage of using advanced molecular systems such as the GeneXpert RT-PCR is the reduction of mutations that may arise from repeated subculturing and in vitro passage. Laboratory subculturing can induce subtle genomic changes in

S. aureus, triggering alternative expression pathways that alter key characteristics of genotypes. These changes can lead to significant misinterpretations in downstream analyses. Previous studies, including our own, have demonstrated that such in vitro artifacts, if not controlled by well-designed protocols, can significantly distort the genetic profiles of isolates originally obtained from patients [

21,

22].

The GeneXpert system addresses these issues by enabling direct molecular detection from patient specimens, providing accurate strain profiles that are consistent with clinical presentation, demographic data, and disease classification. In this study, molecular detection was performed using the latest versions of the Cepheid GeneXpert® Dx system, utilizing the SA Complete and MRSA assay kits, following the manufacturer’s protocols and kit specifications.

The GeneXpert platform employs a fully automated, multiplex real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) approach using preloaded primers and probes targeting the nuc, spa, mecA, and SCCmec genes. These are housed in single-use, self-contained cartridges with built-in reagents. The system integrates sample purification, amplification, and detection into a single workflow, minimizing contamination, DNA degradation, and sample handling errors. Each cartridge is inoculated directly with the patient sample (e.g., swab) and inserted into the instrument, which is connected to a personal computer with preinstalled software for test operation and result interpretation.

Quality assurance is maintained through internal controls: the Sample Processing Control (SPC) monitors adequate processing of the bacterial target and checks for potential PCR inhibitors, while the Probe Check Control (PCC) verifies reagent rehydration, PCR tube filling, probe functionality, and dye stability. These controls help ensure the reliability and accuracy of the molecular detection process.

Data Management and Statistical Analysis

Demographic and microbiological data were recorded using local databases and Microsoft Excel and REDCap) and then imported into Statistical Package for Social Sciences software (SPSS, IBM; Version 24 for Windows (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Prepared data was analyzed using Descriptive stratified analysis. We present absolute numbers, proportions, and graphical distributions. We conducted Chi square and exact statistical tests for proportions and show p-values where appropriate (a p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant).

Prior to analysis, continuous variables were assessed for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Due to the non-normal distribution of the demographic data, non-parametric tests were applied. Differences in demographic characteristics (age and gender distributions) between ICU and non-ICU populations (

Table 1) were evaluated using the Mann-Whitney U test. A two-tailed p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Categorical variables—such as the distribution of clinical specimen sources (blood, respiratory, wounds, and other sites;

Table 2), MRSA versus MSSA prevalence (

Table 4 and

Table 5), and antibiotic resistance profiles (

Table 3)—were compared using Chi-square tests for independence. For each 2×2 contingency table (e.g., comparing MRSA prevalence between ICU and non-ICU within specific age groups), degrees of freedom were set to 1, and significance was defined as p < 0.05. In addition, gender-specific comparisons of MRSA prevalence across ICU and non-ICU settings were performed using Chi-square tests (as shown in the merged analysis in

Table 6). All p-values reported are two-tailed. Overall, these statistical methods allowed us to assess whether differences in demographic distributions, MRSA/MSSA prevalence, and antibiotic resistance patterns were statistically significant, thus supporting targeted infection control and treatment strategies.

3. Results

Demographic Distribution of S. aureus Isolates in ICU and Non-ICU Settings

A total of 106 isolates (41.9%) were recovered from the ICU, whereas 149 isolates (58.1%) were obtained from non-ICU areas. Within the ICU cohort (

n = 106), 75 (71%) isolates originated from male patients and 31 (29%) from female patients. Among male ICU patients, the 70+ age group had the highest proportion (28/75, 61.9%), followed by the 10–29 group (15/75, 51.7%), 50–69 group (25/75, 43.1%), and the 30–49 group (7/75, 17.9%). For female ICU patients, the highest proportion of isolates was observed in the 10–29 group (7/15, 46.7%), followed by 30–49 (7/19, 36.8%), 50–69 (8/33, 24.2%), and 70+ (9/18, 50.0%) (

Table 1).

Among non-ICU patients (n = 149), (64%;

n= 95) isolates were obtained from males and (36%;

n=54) from females. Male non-ICU patients showed the highest proportion of isolates in the 30–49 age group (32/39, 82.1%), followed by 50–69 (33/58, 56.9%), 10–29 (14/29, 48.3%), and 70+ (16/42, 38.1%). For female non-ICU patients, the highest proportion was found in the 50–69 group (25/33, 75.8%), followed by 30–49 (12/19, 63.2%), 10–29 (8/15, 53.3%), and 70+ (9/18, 50.0%) (

Table 1).

Comparison of the demographic distribution between ICU and non-ICU populations using the Mann-Whitney U test yielded no statistically significant difference (U = 6641.5, Wilcoxon W = 20837.5, Z = –1.064, p = 0.287), indicating that while there were differences in some absolute numbers, the overall demographic patterns did not differ significantly (

Table 1).

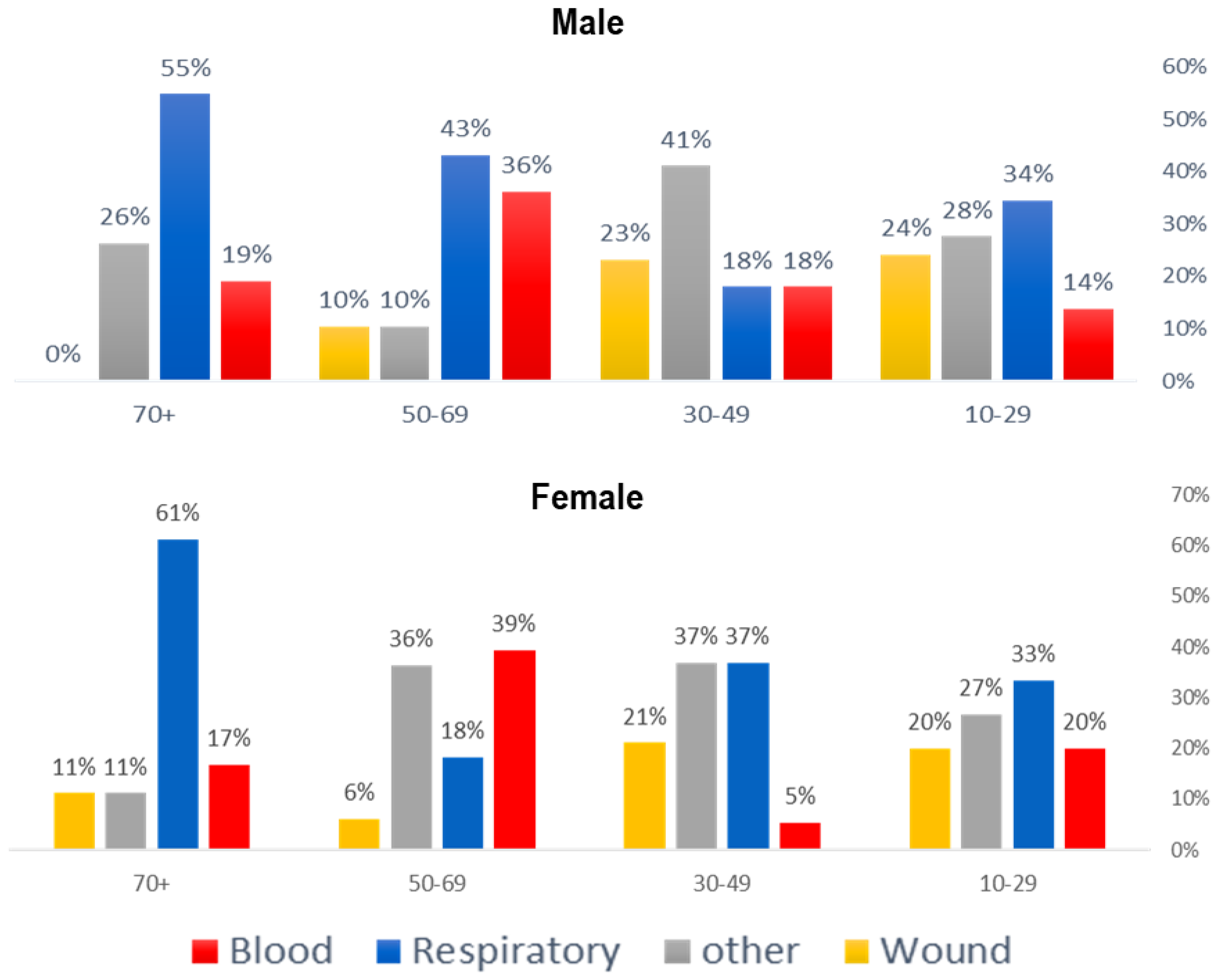

Distribution of Clinical Specimen Sources Among Patient Groups

A total of 60 isolates (24%) were derived from blood, 94 (37%) from respiratory samples, 66 (26%) from other sites, and 33 (13%) from wounds. In male patients, the 50–69 age group exhibited the highest proportion of respiratory isolates (43.1%), followed by blood samples (36.2%) and other sites (10.3%). The 70+ male group had the highest respiratory isolation rate (54.8%), with blood samples contributing 19.0% and other sites 26.2%, while no isolates were obtained from wounds. The 30–49 male group showed 41.0% of isolates from other sites, while respiratory and blood samples each accounted for 17.9%. In the 10–29 male group, respiratory samples made up 34.5%, other sites 27.6%, wound isolates 24.1%, and blood samples 13.8%. Among female patients, the 70+ age group had the highest proportion of respiratory isolates (61.1%), while blood, wound, and other site isolates each contributed 16.7%, 11.1%, and 11.1%, respectively. The 50–69 female group had a more balanced distribution, with 39.4% of isolates from blood, 18.2% from respiratory samples, 36.4% from other sites, and 6.1% from wounds. The 30–49 female group recorded 36.8% respiratory isolates, 36.8% from other sites, 21.1% from wounds, and 5.3% from blood. The 10–29 female group exhibited a distribution of 33.3% respiratory isolates, 26.7% from other sites, 20.0% each from blood and wound isolates (

Table 2). Overall, 45 blood isolates (24.5%) were identified as MRSA, compared to 15 (21.7%) MSSA. Similar trends were observed in respiratory and wound specimens, where MRSA accounted for 41.8% and 10.3% of isolates, respectively, while MSSA made up 24.6% and 20.3% of isolates, respectively. Respiratory samples had the highest percentage of MRSA, while wound samples had the lowest (

Table 2 and

Figure 1).

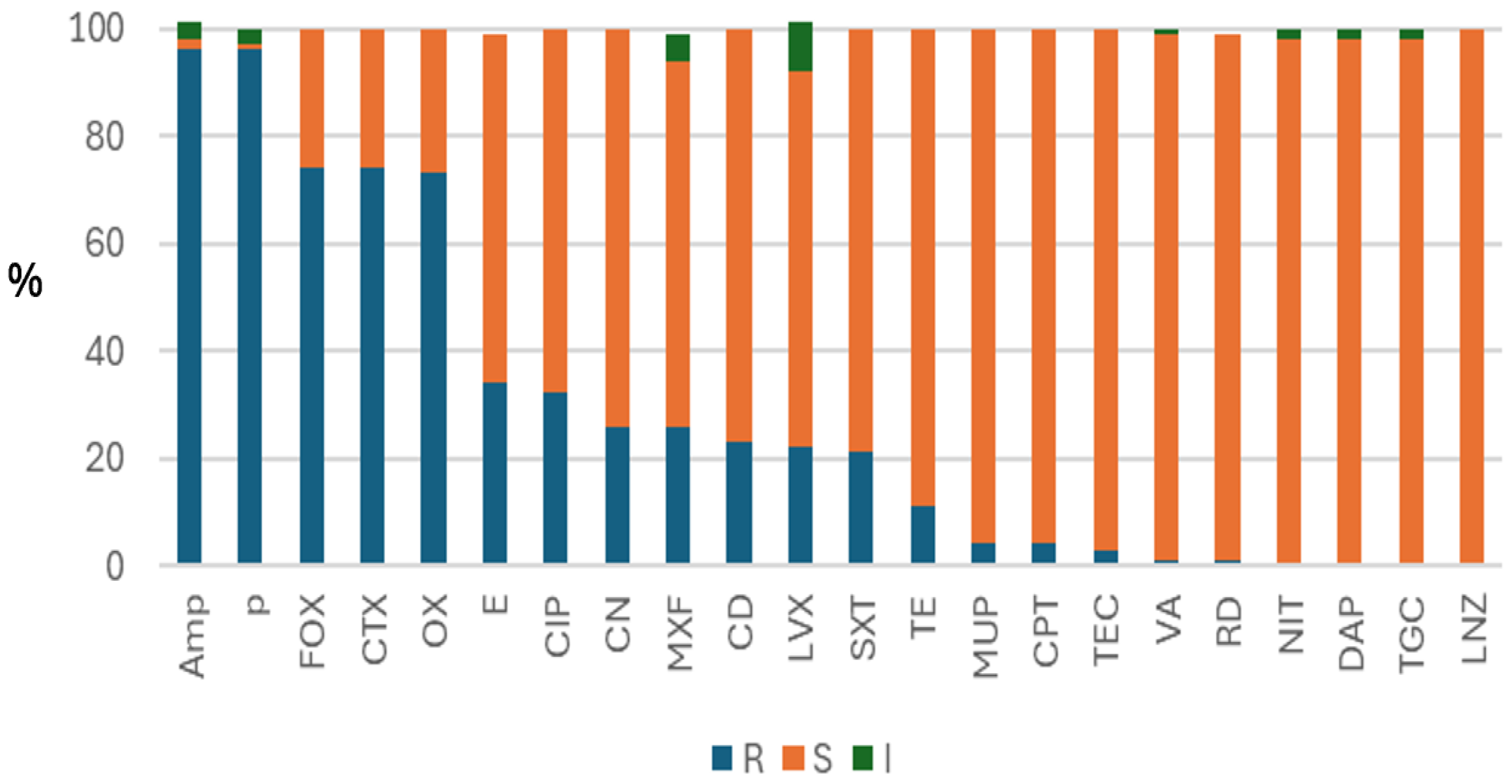

Antibiotic Resistance Profiles of Staphylococcus aureus Isolates

A substantial proportion of isolates demonstrated resistance to β-lactam antibiotics. Specifically, 73.9% were resistant to cefoxitin and cefotaxime, while ampicillin and penicillin resistances each reached 96%. In line with CLSI criteria and molecular confirmation (GeneXpert), any isolate with positive resistant elements and resistance to cefoxitin or oxacillin was classified as MRSA. Among these MRSA strains, many also exhibited co-resistance to non–β-lactam antibiotics, reflecting a HA-MRSA profile. In contrast, MRSA isolates that remained susceptible to most non–β-lactam agents aligned with CA-MRSA characteristics.

High fluoroquinolone resistance was observed, with 73.1% of isolates resistant to ofloxacin, whereas ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin maintained susceptibility rates of 68.0% and 69.6%, respectively. Resistance to gentamicin and trimethoprim was comparatively lower at around 20–26%. Among glycopeptides, vancomycin and teicoplanin retained strong efficacy, with 97.6% and 96.8% susceptibility, respectively, and only rare intermediate or resistant strains detected. Daptomycin also remained highly active, with 98.4% of isolates susceptible.

Regarding lincosamide and macrolide agents, clindamycin resistance was noted in 22.5% of isolates (with 0.4% intermediate), and erythromycin resistance reached 34.4%. Linezolid showed excellent in vitro activity, with 99.6% of isolates susceptible. Nitrofurantoin (97.6%), rifampicin (98.4%), and tetracycline (88.9%) also exhibited high activity, whereas moxifloxacin susceptibility was 68.4%. Ceftaroline and tigecycline both displayed favorable profiles (95.7% and 98.4% susceptibility, respectively) (

Table 3 and

Figure 2).

Taken together, these findings highlight the predominance of MRSA in this setting, driven by broad β-lactam resistance and, in many cases, co-resistance to fluoroquinolones. However, vancomycin, daptomycin, linezolid, and tigecycline remained effective therapeutic options.

Age and Gender-Specific Prevalence of MRSA and MSSA

Among male patients (n = 168), 117 isolates (69.6%) were identified as MRSA and 51 (30.4%) as MSSA. In contrast, among female patients (n = 85), 67 isolates (78.8%) were MRSA and 18 (21.2%) were MSSA. Within the ICU setting, the highest proportion of MRSA was observed in the 10–29 age group (20/22, 90.9%), followed by the 50–69 group (29/33, 87.9%). The 30–49 age group had an MRSA prevalence of 64.3% (9/14). Patients aged 70+ in the ICU showed an MRSA proportion of 68.6% (24/35), remaining more frequently MRSA than MSSA. In non-ICU settings, the distribution of MRSA differed notably across age groups. The 10–29 age group exhibited 45.5% MRSA (10/22), which was the only category in which MSSA was more prevalent (54.5%). The 30–49 group had an MRSA prevalence of 59.1% (26/44), whereas the 50–69 age group demonstrated a 79.3% (46/58) MRSA prevalence. In the 70+ non-ICU group, MRSA accounted for 80.0% (20/25) of isolates, the highest proportion outside the ICU (

Table 4). Taken together, these findings highlight a pronounced prevalence of MRSA among both male and female patients, with particularly high MRSA proportions in middle-aged and older adults across ICU and non-ICU settings. The 10–29 non-ICU group showed a different trend, where MSSA exceeded MRSA prevalence, suggesting potential differences in community-acquired versus hospital-acquired infection patterns in younger patients. These findings emphasize the need for targeted infection control measures and antibiotic stewardship programs in both ICU and general hospital wards (

Table 4).

Gender-Based Differences in MRSA and MSSA Prevalence Across ICU and Non-ICU Settings

When analyzing gender distribution by age group in ICU and non-ICU settings, notable differences emerged between male and female patients. In the 10–29 age group, non-ICU females (64.0%) had a higher MRSA rate than ICU females (36.0%), while rates in males were similar between ICU (51.7%) and non-ICU (48.3%). In the 30–49 and 50–69 age groups, non-ICU patients, especially females, had higher MRSA prevalence than ICU patients. Among 70+ patients, MRSA rates were evenly distributed between ICU and non-ICU settings (50.0%) in females, while ICU males had a higher MRSA prevalence (67.0%) compared to non-ICU males (33.0%). These findings highlight age- and gender-specific MRSA trends, emphasizing the need for tailored infection control strategies in both ICU and non-ICU settings (

Table 5).

A 2×2 Chi-square test was performed for each age group to compare gender distribution (male vs. female) between ICU and non-ICU settings. Each 2×2 table had 1 degree of freedom. A significant difference (p < 0.05) was observed only in the 50–69 age group (X² = 10.766, p = 0.001), indicating that males in this bracket were more likely to be in the ICU, whereas females were more frequently in the non-ICU group. In the 10–29, 30–49, and 70+ age groups, there was no significant difference in the male/female distribution (p > 0.05). Thus, 50–69 stands out as the only age range with a statistically meaningful discrepancy in gender distribution across ICU and non-ICU settings (

Table 6).

4. Discussion

Staphylococcus aureus continues to evolve and emerge spreading as a strong adversary in healthcare, especially in large hospitals where complex patient conditions and invasive procedures help it spread. Our study-of 253 S. aureus isolates (41.9% from ICU, 58.1% from non-ICU)-which examined the age- and gender-specific presence and disease profiles of MRSA and MSSA, provided important trends supporting and expanding on earlier reports in this field.

A key part of MRSA’s challenge in the clinic is its resistance to β-lactam antibiotics, driven by the

mecA gene [

23]. This change makes common treatments, such as penicillins and cephalosporins, mostly ineffective and forces clinicians to use other alternatives including glycopeptides and oxazolidinones [

24]. Our results, showing 73.9% resistance to cefoxitin/cefotaxime and 96% resistance to ampicillin/penicillin, mirrored these well-known mechanisms and echoed on global reports that highlight the growing difficulties in treating MRSA infections [

25,

26]. Nevertheless, the major pitfall in

S. aureus treatment and management strategies has been the mere reliance on new drugs alone juxtaposing the species potentials similar to all other bacteria. As we and others have been examining for decades, the widely known rapid adaptational capacity of the species and evolution of resistant clones despite genome-stability and clonal backgrounds in humans and animals [

22,

27], makes it imperative for a relevant change in MRSA control strategy. The species is one of the most powerful pathogens ever known in expressing subtle human-specialized mechanisms of adaptations and genome-plasticity [

28,

29]. It therefore plausible that the age-, gender-, ecosystems, and host-microenvironments-all differentiate the evolution of clonal lineages specific to each demographic factor [

30,

31] – and these should be the major focus for the Superbug. The high proportion of MRSA in our hospital, across both ICU and non-ICU settings, reminds us that MRSA is still firmly rooted in areas where the risk is elevated. In our ICU population, which comprised 71% male and 29% female isolates, invasive procedures and intensive antibiotic pressure create an environment that favors MRSA persistence [

32,

33]. Many studies have observed that ICU patients face higher MRSA rates than those in general wards, a fact that our data also reflected [

34,

35].

Our findings show that while patient characteristics between ICU and non-ICU groups did not differ greatly, there were distinctions in the absolute numbers and infection types. Older ICU patients, particularly those aged 70+ years, experienced more respiratory (54.8% in males and 61.1% in females) and bloodstream infections, likely reflecting ventilator use and immunocompromised status. This is in line with work showing that critically ill patients often develop severe MRSA infections, such as bacteremia and pneumonia, which can lead to higher illness and death rates [

36,

37,

38].

When we looked at age-specific trends, we saw that MRSA became more common in older individuals. This pattern is well-documented in many places: older adults, particularly those above 60, are more prone to MRSA infection due to factors like a weaker immune system and more chronic diseases [

14,

39,

40]. In our data, the 70+ group had high MRSA rates in both ICU and non-ICU wards. Meanwhile, younger people also develop MRSA, though their patterns can differ. Some works describe a “J-shaped” curve where both very young and older patients carry higher MRSA rates [

9,

35]. This likely points to different causes in children and older adults. Among our younger patients (10–29 years) in non-ICU areas, MSSA sometimes matched or exceeded MRSA rates, suggesting that these are evolutionary ancestors for invasive skin and soft tissue infections emerging as CA-MRSA in youth and HA-MRSA by age [

41].

We also observed notable gender diffyoiu\erences in MRSA rates. While many reports find that men are more likely to have MRSA—attributed to factors like greater colonization and different hygiene practices [

3,

42]— our work showed that some female groups had higher MRSA levels. Conflicting results in various studies emphasize that gender-related differences in MRSA likely arise from local, behavioral, and even hormonal issues [

43,

44]. For instance, a study in a maternity and children’s hospital found increased MRSA in young female patients, suggesting that local circumstances and certain risks can outweigh the usual male dominance [

43]. In our data, young female patients in the ICU had lower MRSA rates than those outside the ICU, while older groups had fewer differences. This suggests that gender-related risks might blend with clinical settings to form unique local patterns of MRSA.

Our review of diseases tied to MRSA and MSSA offers more insights into their clinical impact. Many reports point to skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs) as the main expression of MRSA, especially in the community [

40,

45,

46]. While SSTIs were common across ages in our findings, older and ICU patients more often had respiratory and bloodstream infections. This is logical, as older or critically ill individuals may have weaker lungs or require devices, raising their risk of serious infections. We also saw that younger patients are more likely to present with SSTIs, while older groups are more prone to pneumonia and bacteremia. These differences show how diagnosis and treatment might need to be customized by age and setting.

Our detailed look at antibiotic resistance patterns is another vital piece. MRSA isolates in our study largely resisted β-lactams and fluoroquinolones, reflecting the effect of the mecA gene and pressures from antibiotic use [

47]. However, they remained mostly vulnerable to glycopeptides (such as vancomycin), oxazolidinones (such as linezolid), and newer treatments like tigecycline and daptomycin. These data are in line with several studies from similar hospitals, which show that although older antibiotics are losing ground, the newer “last-resort” agents still work [

9,

40,

48]. Nonetheless, the strong resistance to fluoroquinolones in our study is concerning, since these drugs are often used first in practice. Differences in resistance patterns between our data and that from places like Vietnam and India stress the need for stewardship programs that watch local trends [

3,

44].

When comparing ICU and non-ICU wards, we found that although there were no huge differences in overall patient demographics, the ICU environment still carried a heavier load of severe MRSA infections. ICUs are known hotspots because of high-risk patients, frequent use of invasive devices, and broad-spectrum antibiotics [

10]. Our data, showing greater MRSA rates in ICU patients (especially in bloodstream and lung infections), strengthen this well-recognized situation. It also signals the importance of strong infection control in ICUs, including active screening, careful hand hygiene, and decolonization. Older adults in the ICU were hit the hardest by MRSA, reinforcing the idea that they deserve extra attention in control measures.

Local patterns do not exist in a vacuum, and our study fits into global observations. Worldwide, MRSA prevalence can vary widely, from around 13% in some places to over 70% in others [

49,

50]. For example, Saudi Arabia’s average MRSA rate is about 32.5%, and it has been rising [

43]. Meanwhile, certain European nations, such as the Netherlands, have kept rates very low with strong control efforts [

51]. Our hospital’s MRSA and MSSA levels must be interpreted in this broad context, where health policies, antibiotic usage, and population traits differ. By offering a careful snapshot of MRSA in a tertiary hospital, our study reminds us that even within one place, age, gender, and clinical areas can shape different MRSA patterns.

These insights have several implications. Clinically, the high MRSA rate in older age groups and in the ICU suggests that initial antibiotic choices in these groups should cover MRSA. With β-lactams and fluoroquinolones often failing, clinicians should consider drugs proven effective against MRSA, such as vancomycin or linezolid. From an infection control view, our data hint that screening and decolonizing might be especially effective in the ICU and among older patients. For example, swabbing for MRSA at admission and then isolating and decolonizing those who test positive might lower the spread in these high-risk settings.

Regarding gender-based trends, our findings reveal that while some works describe a higher burden in men, local factors may create a different picture. This indicates that prevention and treatment plans for MRSA should be flexible and consider the specific patient groups served by each hospital [

10,

44]. Future research could focus on the social, biological, and cultural elements behind these gender differences, paving the way for more personal interventions.

Lastly, our review of antibiotic susceptibility underscores how quickly resistance patterns can shift. The marked resistance to widely used drugs in our study underlines the need for steady local observation of resistance and for strict antibiotic stewardship programs. As patterns change, it is crucial that providers adjust their standard therapies and that infection control teams track these changes constantly. With the threat of resistance to even our newest treatments, we must keep searching for fresh therapies and different approaches to fighting MRSA.

In summary, our work offers a clear view of how MRSA and MSSA each lineage differs by age, gender, and disease type in a tertiary hospital, relevant to host- and tissue-specific evolutions. The strong presence of MRSA in older adults and ICU settings, contrasted with community-associated patterns among younger non-ICU patients, underscoring the need for targeted interventions and tailored treatment strategies. These findings are immediately relevant to everyday practice, highlighting the significance of host-specialized screening, relevant infection control, and updated antibiotic policies to ease the burden of MRSA in high-risk areas.

In the bigger picture, we confirm that while our local trends mirror many of the global patterns—such as older adults and ICU patients being more prone to MRSA—our hospitals also have unique details that deserve further study. Next steps should involve molecular and genomic research to track MRSA’s ancestors lines in our setting and discover potential connections between strains from the community and the hospital. Such future work would deepen our understanding of MRSA’s spread and lead to even more precise infection control.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our study emphasizes the urgent need for careful, ecotype-strain specialized strategies to manage MRSA in tertiary care facilities. Ongoing surveillance, targeted screening for lineage ancestors in youth, and strong antibiotic stewardship remain essential to mitigate the clinical and economic impacts of MRSA in these vulnerable hospital environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Kamaleldin B Said; Data curation, Kamaleldin B Said, Khalid F Alshammari, Ruba Ahmed, Fawwaz Alshammari, Ahmed H. Jadani, Ehab Rakha, Salem Almijrad, Anwar E. Almallahi, Bader Alkharisi, Naif Altamimi, Tariq Mahmoud, Nada A bosaid and Amal Alshammari; Formal analysis, Kamaleldin B Said, Khalid F Alshammari, Ruba Ahmed, Fawwaz Alshammari, Ahmed H. Jadani, Ehab Rakha, Salem Almijrad, Anwar E. Almallahi, Bader Alkharisi, Naif Altamimi, Tariq Mahmoud, Nada A bosaid and Amal Alshammari; Funding acquisition, Kamaleldin B Said; Investigation, Kamaleldin B Said and Salem Almijrad; Methodology, Kamaleldin B Said, Khalid F Alshammari, Ruba Ahmed, Fawwaz Alshammari, Ahmed H. Jadani, Ehab Rakha, Salem Almijrad, Anwar E. Almallahi, Bader Alkharisi, Naif Altamimi, Tariq Mahmoud, Nada A bosaid and Amal Alshammari; Project administration, Kamaleldin B Said; Resources, Kamaleldin B Said, Khalid F Alshammari, Ruba Ahmed, Fawwaz Alshammari, Ahmed H. Jadani, Ehab Rakha, Salem Almijrad, Anwar E. Almallahi, Bader Alkharisi, Naif Altamimi, Tariq Mahmoud, Nada A bosaid and Amal Alshammari; Software, Kamaleldin B Said, Khalid F Alshammari, Ruba Ahmed, Fawwaz Alshammari, Ahmed H. Jadani, Ehab Rakha, Salem Almijrad, Anwar E. Almallahi, Bader Alkharisi, Naif Altamimi, Tariq Mahmoud, Nada A bosaid and Amal Alshammari; Supervision, Kamaleldin B Said; Validation, Kamaleldin B Said, Khalid F Alshammari, Ruba Ahmed, Fawwaz Alshammari, Ahmed H. Jadani, Ehab Rakha, Salem Almijrad, Anwar E. Almallahi, Bader Alkharisi, Naif Altamimi, Tariq Mahmoud, Nada A bosaid and Amal Alshammari; Visualization, Kamaleldin B Said, Khalid F Alshammari, Ruba Ahmed, Fawwaz Alshammari, Ahmed H. Jadani, Ehab Rakha, Salem Almijrad, Anwar E. Almallahi, Bader Alkharisi, Naif Altamimi, Tariq Mahmoud, Nada A bosaid and Amal Alshammari; Writing – original draft, Kamaleldin B Said; Writing – review & editing, Kamaleldin B Said, Khalid F Alshammari, Ruba Ahmed, Fawwaz Alshammari, Ahmed H. Jadani, Ehab Rakha, Salem Almijrad, Anwar E. Almallahi, Bader Alkharisi, Naif Altamimi, Tariq Mahmoud, Nada A bosaid and Amal Alshammari.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Research Ethical Committee (REC) of University of Ha’il, Saudi Arabia, has Approved this research by the number (H-2024-496), dated REC 4/11/A2024. In addition, IRB Approval (Log 2024-120, Dec 2024) was obtained from Ha’il Health Cluster, Ha’il to perform this work.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. A blank copy attached herewith this manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

Blank Informed Consent file uploaded herewith this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the University of Ha’il’s Deanship for research, REC, and clinics for their support throughout this work. As native English speakers, some of authors have thoroughly proofread this manuscript for clarity and accuracy. No AI-generated content was used in drafting or revising, All scientific content, data interpretation, and conclusions are solely the authors’ work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Patil PP, Patil HV, Patil S. Evaluation of Antibiotic Sensitivity in Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Isolates From Clinical Specimens in a Tertiary Care Hospital. Cureus. 2024;16(10):e72628. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim RA, Wang SH, Gebreyes WA, Mediavilla JR, Hundie GB, Mekuria Z, et al. Antimicrobial resistance profile of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from patients, healthcare workers, and the environment in a tertiary hospital in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2024;19(8):e0308615. [CrossRef]

- Ghia CJ, Waghela S, Rambhad G. A Systemic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis Reporting the Prevalence and Impact of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Infection in India. Infect Dis (Auckl). 2020;13:1178633720970569. [CrossRef]

- Pradhan P, Rajbhandari P, Nagaraja SB, Shrestha P, Grigoryan R, Satyanarayana S, et al. Prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a tertiary hospital in Nepal. Public Health Action. 2021;11(Suppl 1):46-51. [CrossRef]

- Gurung RR, Maharjan P, Chhetri GG. Antibiotic resistance pattern of Staphylococcus aureus with reference to MRSA isolates from pediatric patients. Future Sci OA. 2020;6(4):Fso464. [CrossRef]

- Shoaib M, Aqib AI, Muzammil I, Majeed N, Bhutta ZA, Kulyar MF, et al. MRSA compendium of epidemiology, transmission, pathophysiology, treatment, and prevention within one health framework. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:1067284. [CrossRef]

- Yao Z, Wu Y, Xu H, Lei Y, Long W, Li M, et al. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections among dermatology inpatients: A 7-year retrospective study at a tertiary care center in southwest China. Frontiers in Public Health. 2023;Volume 11 - 2023. [CrossRef]

- Hasanpour AH, Sepidarkish M, Mollalo A, Ardekani A, Almukhtar M, Mechaal A, et al. The global prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization in residents of elderly care centers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2023;12(1):4. [CrossRef]

- Said KB, AlGhasab NS, Alharbi MSM, Alsolami A, Bashir AI, Saleem M, et al. A Sequalae of Lineage Divergence in Staphylococcus aureus from Community-Acquired Patterns in Youth to Hospital-Associated Profiles in Seniors Implied Age-Specific Host-Selection from a Common Ancestor. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13(5). [CrossRef]

- Soe PE, Han WW, Sagili KD, Satyanarayana S, Shrestha P, Htoon TT, et al. High Prevalence of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus among Healthcare Facilities and Its Related Factors in Myanmar (2018-2019). Trop Med Infect Dis. 2021;6(2). [CrossRef]

- Ben-David D, Mermel LA, Parenteau S. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus transmission: the possible importance of unrecognized health care worker carriage. Am J Infect Control. 2008;36(2):93-7. [CrossRef]

- Madani TA, Al-Abdullah NA, Al-Sanousi AA, Ghabrah TM, Afandi SZ, Bajunid HA. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in two tertiary-care centers in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2001;22(4):211-6. [CrossRef]

- Elixhauser A, Steiner C. Infections with Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA) in U.S. Hospitals, 1993–2005. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2006.

- Pomorska-Wesołowska M, Różańska A, Natkaniec J, Gryglewska B, Szczypta A, Dzikowska M, et al. Longevity and gender as the risk factors of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in southern Poland. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):51. [CrossRef]

- Kupfer M, Jatzwauk L, Monecke S, Möbius J, Weusten A. MRSA in a large German University Hospital: Male gender is a significant risk factor for MRSA acquisition. GMS Krankenhhyg Interdiszip. 2010;5(2). [CrossRef]

- Humphreys H, Fitzpatick F, Harvey BJ. Gender Differences in Rates of Carriage and Bloodstream Infection Caused by Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Are They Real, Do They Matter and Why? Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2015;61(11):1708-14. [CrossRef]

- Qiao F, Huang W, Cai L, Zong Z, Yin W. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization and infection in an intensive care unit of a university hospital in China. J Int Med Res. 2018;46(9):3698-708. [CrossRef]

- Kim H, Kim ES, Lee SC, Yang E, Kim HS, Sung H, et al. Decreased Incidence of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Bacteremia in Intensive Care Units: a 10-Year Clinical, Microbiological, and Genotypic Analysis in a Tertiary Hospital. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2020;64(10). [CrossRef]

- Samuel P, Kumar YS, Suthakar BJ, Karawita J, Sunil Kumar D, Vedha V, et al. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Colonization in Intensive Care and Burn Units: A Narrative Review. Cureus. 2023;15(10):e47139. [CrossRef]

- Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, Carmeli Y, Falagas ME, Giske CG, et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(3):268-81. [CrossRef]

- Said KB, Ramotar K, Zhu G, Zhao X. Repeat-based subtyping and grouping of Staphylococcus aureus from human infections and bovine mastitis using the R-domain of the clumping factor A gene. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;63(1):24-37. [CrossRef]

- Said Kamaleldin B, Ismail J, Campbell J, Mulvey Michael R, Bourgault A-M, Messier S, et al. Regional Profiling for Determination of Genotype Diversity of Mastitis-Specific Staphylococcus aureus Lineage in Canada by Use of Clumping Factor A, Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis, and spa Typing. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2010;48(2):375-86. [CrossRef]

- Ali T, Basit A, Karim AM, Lee J-H, Jeon J-H, Rehman SU, et al. Mutation-Based Antibiotic Resistance Mechanism in Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Clinical Isolates. Pharmaceuticals [Internet]. 2021; 14(5). [CrossRef]

- Maddiboyina B, Roy H, Ramaiah M, Sarvesh CN, Kosuru SH, Nakkala RK, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: novel treatment approach breakthroughs. Bulletin of the National Research Centre. 2023;47(1):95. [CrossRef]

- Brown NM, Goodman AL, Horner C, Jenkins A, Brown EM. Treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA): updated guidelines from the UK. JAC-Antimicrobial Resistance. 2021;3(1):dlaa114. [CrossRef]

- Lade H, Kim J-S. Molecular Determinants of β-Lactam Resistance in Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA): An Updated Review. Antibiotics [Internet]. 2023; 12(9). [CrossRef]

- Feil, E., J. Cooper, H. Grundmann, D. Robinson, M. Enright, T. Berendt, S. Peacock, J. Smith, M. Murphy, B. Spratt, C. Moore, and N. Day. 2003. How clonal is Staphylococcus aureus? J. Bacteriol. 185 : 3307-3316. [CrossRef]

- Highlander, S., K. Hultén, X. Qin, H. Jiang, S. Yerrapragada, E. J. Mason, Y. Shang, T. Williams, R. Fortunov, Y. Liu, O. Igboeli, J. Petrosino, M. Tirumalai, A. Uzman, G. Fox, A. Cardenas, D. Muzny, L. Hemphill, Y. Ding, S. Dugan, P. Blyth, C. Buhay, H. Dinh, A. Hawes, M. Holder, C. Kovar, S. Lee, W. Liu, L. Nazareth, Q. Wang, J. Zhou, S. Kaplan, and G. Weinstock. 2007. Subtle genetic changes enhance virulence of methicillin resistant and sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. BMC Microbiol. 7 : 99. [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, F., S. Watanabe, T. Baba, H. Yuzawa, T. Ito, Y. Morimoto, M. Kuroda, L. Cui, M. Takahashi, A. Ankai, S. Baba, S. Fukui, J. Lee, and K. Hiramatsu. 2005. Whole-genome sequencing of Staphylococcus haemolyticus uncovers the extreme plasticity of its genome and the evolution of human-colonizing staphylococcal species. J. Bacteriol. 187 : 7292-7308. [CrossRef]

- van Leeuwen, W., D. Melles, A. Alaidan, M. Al-Ahdal, H. Boelens, S. Snijders, H. Wertheim, E. van Duijkeren, J. Peeters, P. van der Spek, R. Gorkink, G. Simons, H. Verbrugh, and A. van Belkum. 2005. Host- and tissue-specific pathogenic traits of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 187 : 4584-4591. [CrossRef]

- Josefsson E, Kubica M, Mydel P, Potempa J, Tarkowski A. In vivo sortase A and clumping factor A mRNA expression during Staphylococcus aureus infection. Microb Pathog 2008;44:103-110. [CrossRef]

- Lee AS, Harbarth SJ. Infection Control in the ICU: MRSA Control. In: Vincent J-L, Hall JB, editors. Encyclopedia of Intensive Care Medicine. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2012. p. 1216-25.

- Oztoprak N, Cevik MA, Akinci E, Korkmaz M, Erbay A, Eren SS, et al. Risk factors for ICU-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. American Journal of Infection Control. 2006;34(1):1-5. [CrossRef]

- Dancer SJ, Coyne M, Speekenbrink A, Samavedam S, Kennedy J, Wallace PGM. MRSA acquisition in an intensive care unit. American Journal of Infection Control. 2006;34(1):10-7. [CrossRef]

- Buckley MS, Kobic E, Yerondopoulos M, Sharif AS, Benanti GE, Meckel J, et al. Comparison of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Nasal Screening Predictive Value in the Intensive Care Unit and General Ward. Ann Pharmacother. 2023;57(9):1036-43. [CrossRef]

- Hassoun A, Linden PK, Friedman B. Incidence, prevalence, and management of MRSA bacteremia across patient populations—a review of recent developments in MRSA management and treatment. Critical Care. 2017;21(1):211. [CrossRef]

- Shorr AF, Zilberberg MD, Micek ST, Kollef MH. Outcomes associated with bacteremia in the setting of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia: a retrospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2015;19(1):312. [CrossRef]

- Carey GB, Holleck JL, Ein Alshaeba S, Jayakrishnan R, Gordon KS, Grimshaw AA, et al. Estimated mortality with early empirical antibiotic coverage of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in hospitalized patients with bacterial infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2023;78(5):1150-9. [CrossRef]

- Hasmukharay K, Ngoi ST, Saedon NI, Tan KM, Khor HM, Chin AV, et al. Evaluation of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bacteremia: Epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and outcomes in the older patients in a tertiary teaching hospital in Malaysia. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2023;23(1):241. [CrossRef]

- Tanihara S, Suzuki S. Estimation of the incidence of MRSA patients: evaluation of a surveillance system using health insurance claim data. Epidemiol Infect. 2016;144(11):2260-7. [CrossRef]

- Gerber JS, Coffin SE, Smathers SA, Zaoutis TE. Trends in the incidence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection in children's hospitals in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(1):65-71. [CrossRef]

- Alhunaif SA, Almansour S, Almutairi R, Alshammari S, Alkhonain L, Alalwan B, et al. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Bacteremia: Epidemiology, Clinical Characteristics, Risk Factors, and Outcomes in a Tertiary Care Center in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Cureus. 2021;13(5):e14934. [CrossRef]

- Almutairi H, Albahadel H, Alhifany AA, Aldalbahi H, Alnezary FS, Alqusi I, et al. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) at a maternity and children hospital in Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study. Saudi Pharm J. 2024;32(4):102001. [CrossRef]

- Al Musawi S, Alkhaleefa Q, Alnassri S, Alamri AM, Alnimr A. Eleven-Year surveillance of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections at an Academic Health Centre. J Prev Med Hyg. 2022;63(1):E132-e8. [CrossRef]

- Loewen K, Schreiber Y, Kirlew M, Bocking N, Kelly L. Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection: Literature review and clinical update. Can Fam Physician. 2017;63(7):512-20.

- Stryjewski ME, Chambers HF. Skin and Soft-Tissue Infections Caused by Community-Acquired Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2008;46(Supplement_5):S368-S77. [CrossRef]

- LeBlanc L, Pépin J, Toulouse K, Ouellette MF, Coulombe MA, Corriveau MP, et al. Fluoroquinolones and risk for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(9):1398-405. [CrossRef]

- Ventola CL. The antibiotic resistance crisis: part 1: causes and threats. P t. 2015;40(4):277-83.

- Zhou S, Hu X, Wang Y, Fei W, Sheng Y, Que H. The Global Prevalence of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus in Patients with Diabetic Foot Ulcers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2024;17:563-74. [CrossRef]

- Nourollahpour Shiadeh M, Sepidarkish M, Mollalo A, As'adi N, Khani S, Shahhosseini Z, et al. Worldwide prevalence of maternal methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Microb Pathog. 2022;171:105743. [CrossRef]

- Wertheim HF, Vos MC, Boelens HA, Voss A, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM, Meester MH, et al. Low prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) at hospital admission in the Netherlands: the value of search and destroy and restrictive antibiotic use. J Hosp Infect. 2004;56(4):321-5. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Distribution of Staphylococcus aureus isolates by clinical specimen source across different age groups and genders. The bar chart represents the percentage of isolates recovered from blood (red), respiratory samples (blue), other sites (gray), and wounds (yellow) among male (top) and female (bottom) patients in four age groups (70+, 50–69, 30–49, and 10–29 years).

Figure 1.

Distribution of Staphylococcus aureus isolates by clinical specimen source across different age groups and genders. The bar chart represents the percentage of isolates recovered from blood (red), respiratory samples (blue), other sites (gray), and wounds (yellow) among male (top) and female (bottom) patients in four age groups (70+, 50–69, 30–49, and 10–29 years).

Figure 2.

Antibiotic susceptibility profiles of Staphylococcus aureus isolates. The x-axis lists the tested antibiotics, abbreviated as follows: Amp (ampicillin), P (penicillin), FOX (cefoxitin), CTX (cefotaxime), OX (oxacillin), CIP (ciprofloxacin), E (erythromycin), CN (gentamicin), MXF (moxifloxacin), CD (clindamycin), LVX (levofloxacin), SXT (trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole), TE (tetracycline), MUP (mupirocin), CPT (ceftaroline), TEC (teicoplanin), VA (vancomycin), RD (rifampicin), NIT (nitrofurantoin), DAP (daptomycin), TGC (tigecycline), and LNZ (linezolid). The y-axis indicates the percentage of isolates categorized as resistant (R, blue), susceptible (S, orange), or intermediate (I, green). Resistance to cefoxitin or oxacillin defined methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), whereas strains susceptible to these agents were classified as methicillin-sensitive S. aureus (MSSA).

Figure 2.

Antibiotic susceptibility profiles of Staphylococcus aureus isolates. The x-axis lists the tested antibiotics, abbreviated as follows: Amp (ampicillin), P (penicillin), FOX (cefoxitin), CTX (cefotaxime), OX (oxacillin), CIP (ciprofloxacin), E (erythromycin), CN (gentamicin), MXF (moxifloxacin), CD (clindamycin), LVX (levofloxacin), SXT (trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole), TE (tetracycline), MUP (mupirocin), CPT (ceftaroline), TEC (teicoplanin), VA (vancomycin), RD (rifampicin), NIT (nitrofurantoin), DAP (daptomycin), TGC (tigecycline), and LNZ (linezolid). The y-axis indicates the percentage of isolates categorized as resistant (R, blue), susceptible (S, orange), or intermediate (I, green). Resistance to cefoxitin or oxacillin defined methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), whereas strains susceptible to these agents were classified as methicillin-sensitive S. aureus (MSSA).

Table 1.

Demographic distribution of S. aureus isolates in ICU and non-ICU settings, stratified by age group and gender.

Table 1.

Demographic distribution of S. aureus isolates in ICU and non-ICU settings, stratified by age group and gender.

| ICU Status |

Gender |

Age Group |

Count |

% within Group |

| ICU |

Male |

10-29 |

15 |

51.70% |

| 30-49 |

7 |

17.90% |

| 50-69 |

25 |

43.10% |

| 70+ |

28 |

61.90% |

| Subtotal Male (ICU) |

75 |

| Female |

10-29 |

7 |

46.70% |

| 30-49 |

7 |

36.80% |

| 50-69 |

8 |

24.20% |

| 70+ |

9 |

50.00% |

| Subtotal Female (ICU) |

31 |

| Total ICU |

106 |

| Non-ICU |

Male |

10-29 |

14 |

48.30% |

| 30-49 |

32 |

82.10% |

| 50-69 |

33 |

56.90% |

| 70+ |

16 |

38.10% |

| Subtotal Male (Non-ICU) |

95 |

| Female |

29-Oct |

8 |

53.30% |

| 30-49 |

12 |

63.20% |

| 50-69 |

25 |

75.80% |

| 70+ |

9 |

50.00% |

| Subtotal Female (Non-ICU) |

54 |

| Total Non-ICU |

149 |

| Overall Total |

Male |

168 |

| Female |

85 |

| Grand Total |

253 |

| Statistical Analysis Results Comparing ICU and Non-ICU Groups |

| Test Statistic |

Value |

| Mann-Whitney U |

6641.5 |

| Wilcoxon W |

20837.5 |

| Z |

-1.064 |

| Asymp. Sig. (2-tailed) |

0.287 |

Table 2.

Distribution of Staphylococcus aureus isolates by clinical specimen source, stratified by age group and gender.

Table 2.

Distribution of Staphylococcus aureus isolates by clinical specimen source, stratified by age group and gender.

| Attribute |

Blood |

Respiratory |

other |

Wound |

| Frequency |

60 |

94 |

66 |

33 |

| Percent |

24 |

37 |

26 |

13 |

| Male |

10-29 |

Count |

4 |

10 |

8 |

7 |

| N% |

13.80% |

34.50% |

27.60% |

24.10% |

| 30-49 |

Count |

7 |

7 |

16 |

9 |

| N% |

17.90% |

17.90% |

41.00% |

23.10% |

| 50-69 |

Count |

21 |

25 |

6 |

6 |

| N% |

36.20% |

43.10% |

10.30% |

10.30% |

| 70+ |

Count |

8 |

23 |

11 |

0 |

| N% |

19.00% |

54.80% |

26.20% |

0.00% |

| Female |

10-29 |

Count |

3 |

5 |

4 |

3 |

| N% |

20.00% |

33.30% |

26.70% |

20.00% |

| 30-49 |

Count |

1 |

7 |

7 |

4 |

| N% |

5.30% |

36.80% |

36.80% |

21.10% |

| 50-69 |

Count |

13 |

6 |

12 |

2 |

| N% |

39.40% |

18.20% |

36.40% |

6.10% |

| 70+ |

Count |

3 |

11 |

2 |

2 |

| N% |

16.70% |

61.10% |

11.10% |

11.10% |

| MRSA Count |

45 |

77 |

43 |

19 |

| MRSA N% |

24.50% |

41.80% |

23.40% |

10.30% |

| MSSA Count |

15 |

17 |

23 |

14 |

| MSSA N% |

21.70% |

24.60% |

33.30% |

20.30% |

Table 3.

Antibiotic resistance patterns of S. aureus isolates, MRSA and MSSA.

Table 3.

Antibiotic resistance patterns of S. aureus isolates, MRSA and MSSA.

| |

Resistant |

Susceptible |

Intermediate |

| Antibiotics |

Count |

N% |

Count |

N% |

Count |

N% |

| Cefoxitin |

187 |

73.90% |

66 |

26.10% |

0 |

0.00% |

| Cefotaxime |

187 |

73.90% |

66 |

26.10% |

0 |

0.00% |

| Ampicillin |

242 |

95.70% |

4 |

1.60% |

7 |

2.80% |

| Penicillin |

243 |

96.00% |

3 |

1.20% |

7 |

2.80% |

| Ofloxacin |

185 |

73.10% |

68 |

26.90% |

0 |

0.00% |

| Gentamicin |

67 |

26.50% |

186 |

73.50% |

0 |

0.00% |

| Trimethoprim |

52 |

20.60% |

201 |

79.40% |

0 |

0.00% |

| Teicoplanin |

7 |

2.80% |

245 |

96.80% |

1 |

0.40% |

| Vancomycin |

1 |

0.40% |

247 |

97.60% |

3 |

1.20% |

| Clindamycin |

57 |

22.50% |

195 |

77.10% |

1 |

0.40% |

| Erythromycin |

87 |

34.40% |

165 |

65.20% |

1 |

0.40% |

| Linezolid |

1 |

0.40% |

252 |

99.60% |

0 |

0.00% |

| Nitrofurantoin |

1 |

0.40% |

247 |

97.60% |

5 |

2.00% |

| Moxifloxacin |

67 |

26.50% |

173 |

68.40% |

13 |

5.10% |

| Rifampicin |

3 |

1.20% |

249 |

98.40% |

1 |

0.40% |

| Tetracycline |

27 |

10.70% |

225 |

88.90% |

1 |

0.40% |

| Ciprofloxacin |

80 |

31.60% |

172 |

68.00% |

1 |

0.40% |

| Mupirocin |

9 |

3.60% |

244 |

96.40% |

0 |

0.00% |

| Daptomycin |

0 |

0.00% |

249 |

98.40% |

4 |

1.60% |

| Ceftaroline |

10 |

4.00% |

242 |

95.70% |

1 |

0.40% |

| Tigecycline |

0 |

0.00% |

249 |

98.40% |

4 |

1.60% |

| Levofloxacin |

55 |

21.70% |

176 |

69.60% |

22 |

8.70% |

Table 4.

Age and gender distribution of MRSA and MSSA isolates in ICU and non-ICU settings.

Table 4.

Age and gender distribution of MRSA and MSSA isolates in ICU and non-ICU settings.

| Category |

MRSA |

MSSA |

| Male |

Count |

117 |

51 |

| N% |

69.6% |

30.4% |

| Female |

Count |

67 |

18 |

| N% |

78.8% |

21.2% |

| ICU |

10-29 |

Count |

20 |

2 |

| N% |

90.9% |

9.1% |

| 30-49 |

Count |

9 |

5 |

| N% |

64.3% |

35.7% |

| 50-69 |

Count |

29 |

4 |

| N% |

87.9% |

12.1% |

| 70+ |

Count |

24 |

11 |

| N% |

68.6% |

31.4% |

| Non-ICU |

10-29 |

Count |

10 |

12 |

| N% |

45.5% |

54.5% |

| 30-49 |

Count |

26 |

18 |

| N% |

59.1% |

40.9% |

| 50-69 |

Count |

46 |

12 |

| N% |

79.3% |

20.7% |

| 70+ |

Count |

20 |

5 |

| N% |

80.0% |

20.0% |

Table 5.

Comparison of MRSA prevalence between male and female patients across different age groups in ICU and non-ICU settings.

Table 5.

Comparison of MRSA prevalence between male and female patients across different age groups in ICU and non-ICU settings.

| |

Sub-Category |

Male

N (ICU vs Non-ICU%)

|

Female

N (ICU vs Non-ICU%)

|

| Gender by Age Group (ICU vs non-ICU) |

10-29 years |

ICU |

15 (51.7%) |

9 (36.0%) |

| Non-ICU |

14 (48.3%) |

16 (64.0%) |

| 30-49 years |

ICU |

7 (17.9%) |

7 (36.8%) |

| Non-ICU |

32 (82.1%) |

12 (63.2%) |

| 50-69 years |

ICU |

25 (64.1%) |

8 (25.0%) |

| Non-ICU |

14 (35.9%) |

24 (75.0%) |

| 70+ years |

ICU |

26 (67.0%) |

9 (50.0%) |

| Non-ICU |

13 (33.0%) |

9 (50.0%) |

Table 6.

Statistical comparison of gender distribution across ICU and non-ICU settings using a 2×2 Chi-square test for each age group.

Table 6.

Statistical comparison of gender distribution across ICU and non-ICU settings using a 2×2 Chi-square test for each age group.

| Age Group |

ICU (M, F) |

Non-ICU (M, F) |

X2 |

p-value

|

Significance |

| 10–29 |

(15, 9) |

(14, 16) |

1.344 |

0.246 |

ns |

| 30–49 |

(7, 7) |

(32, 12) |

2.522 |

0.112 |

ns |

| 50–69 |

(25, 8) |

(14, 24) |

10.766 |

0.001 |

** |

| 70+ |

(26, 9) |

(13, 9) |

1.439 |

0.23 |

ns |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).