1. Introduction

Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) is a chronic inflammatory

disease that affects the joints of affected individuals but is increasing

recognised as a systemic inflammatory disorder that impacts the wider

vasculature, metabolic function and cognition (Alivernini, Firestein and McInnes,

2022). Prevailing evidence strongly indicates that the pathogenesis of RA is

driven by genetic predisposition that increases the autoreactivity of the host

immune response for modified self-antigens that arise due to environmental

influences (Alivernini, Firestein and McInnes, 2022). The most important

genetic risk factor for developing RA resides in the Major Histocompatability

Complex class II complex comprising the highly polymorphic Human Leukocyte

Antigens (HLA) DR, DP and DQ genes encoding cell surface proteins that present

peptide antigens to CD4+ T cells. More specifically, approximately 90% of RA

patients express HLA alleles DRB1*04:01, DRB1*04:04, DRB1*01:01 or DRB1*14:02

that are thought to be involved in the presentation of post-translationally

modified self-antigens, such as citrullinated peptides, to autoreactive CD4+ T

cells via T cell receptor (TCR) signalling (Firestein and McInnes, 2017).

Autoreactive B cells may also recognise these modified antigens through their B

cell receptor and present them to autoreactive T cells, driving T cell: B cell

collaboration and the production of anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies

(ACPAs) that perpetuate inflammatory signalling cascades via crosstalk with

tissue-resident stromal cells and immune cells within the joints (Alivernini,

Firestein and McInnes, 2022). The accumulation of citrullinated peptides in RA

patients is strongly linked with smoking and therefore provides an intriguing

insight into how host genetics and environmental factors may shape the

pathogenesis of this inflammatory disease (Klareskog et al., 2006). As there is

currently no cure for RA, therapeutic interventions are focused on decreasing

inflammatory pathways though various mechanisms (

Table 1). Current treatments include

conventional synthetic Disease Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drugs (csDMARDs) and

glucocorticoids that have broad acting and poorly defined mechanisms of action,

in addition to biological DMARDs (bDMARDs) and targeted synthetic DMARDs

(tsDMARDs) that target more defined inflammatory pathways. For bDMARDs and

tsDMARDs, their mechanism of action includes inhibition of TNFα signalling,

inhibition of T cell co-stimulation, CD20-mediated B cell/plasma cell

depletion, modulation of IL-6 signalling and inhibition of cytokine-mediated

JAK-STAT signalling. Therapeutic regimens are guided by the American College of

Rheumatology (Fraenkel et al., 2021) and the European Alliance of Associations

for Rheumatology (Smolen et al., 2023) in the USA and Europe, respectively.

Despite the plethora of available therapies, RA is a heterogenous disease. Many

patients do not adequately respond to first-line treatments and undergo several

cycles of trial and error with next-in-line therapeutic options. Furthermore,

many patients lose response over time and/or do not achieve clinical remission

with any of the currently available therapies (Smolen et al., 2018). This

latter cohort are defined as ‘difficult-to-treat’. Overall, drug-free remission

in RA is rare (Nagy and Van Vollenhoven, 2015). Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR)

T cell therapy is a clinically approved treatment of different forms of B cell

leukaemia, lymphoma and myeloma, and their success in targeting malignant B

cells has led to their exploration as a potential therapeutic strategy for the

treatment of RA via depletion of B cells (key drivers of inflammation in RA) as

well as other immune cell types and tissues.

2. CAR T Cell Therapy

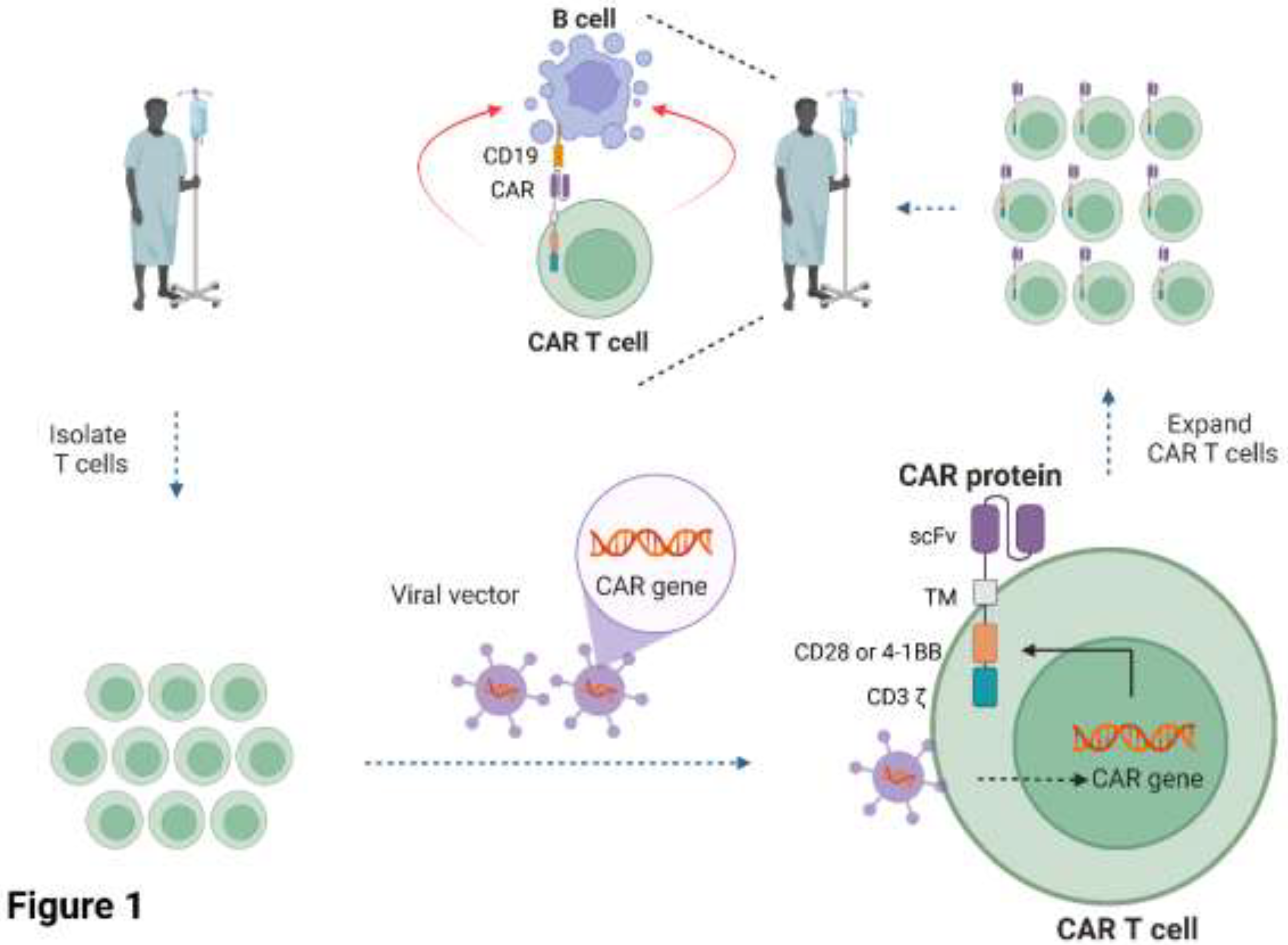

CAR T cells are cell-based therapies whereby the patient’s T cells are extracted from their blood and engineered to express a CAR protein on the surface of the T cells that redirects them towards target cells (June et al., 2018). The engineered T cells are expanded in-vitro before being infused back into the same patient. The CAR is a non-natural synthetic receptor comprised of an extracellular single chain variable fragment (scFv) specific for antigen(s) on the target cell, linked to a transmembrane domain and intracellular signalling domains derived from the TCR (CD3 chain) and the co-stimulatory receptors CD28 or 4-1BB (

Figure 1). The interaction of the CAR molecule with its antigen on the target cell activates the T cell via phosphorylation of the intracellular domains of the CD3 and co-stimulatory domains by endogenous kinases, resulting in the production of toxic chemicals and inflammatory cytokines that promote target cell death. The advantage of CARs is that they can be tailored to target essentially any antigen on the surface of the target cell and modified with different intracellular domains to fine-tune their function (June et al., 2018).

To date, there are seven CAR T cell therapies approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and they all target CD19 or BCMA surface antigens on B cells or plasma cells for the treatment of leukaemia, lymphoma or multiple myeloma (

Table 2; six of these seven products are approved by the European Medicines Agency at the current time of writing). These are highly personalised, cell-derived living drugs that are made for individual patients and have shown unprecedented clinical results, particularly in patients who have failed conventional forms of treatment including different regimens of chemotherapy (Brudno, Maus and Hinrichs, 2024). All current FDA/EMA-approved therapies use second generation CAR constructs comprising the intracellular domain of CD3 and the intracellular domain of CD28 or 4-1BB co-stimulatory receptors (

Table 2). First-generation CAR constructs lacked the co-stimulatory domains necessary for full T cell activation and were ineffective in clinical trials (June et al., 2018), whereas third and fourth generation CAR constructs, comprising two intracellular co-stimulatory domains within a single construct (i.e. CD28 and 4-1BB domains) or incorporating co-expression of inflammatory cytokines/ antibodies, respectively, are currently under evaluation in pre-clinical and clinical studies (Tokarew et al., 2019). Clinically approved CAR T cell production utilises retroviral or lentiviral viral vectors to genetically engineer the cells, as these vectors integrate the CAR gene into the T cell genome to mitigate against gene loss following T cell expansion prior to infusion back into the patient (

Table 2). The primary mechanism of action of these cellular therapies is depletion of CD19+ or BCMA+ B cells or plasma cells, resulting in B cell aplasia and hypogammaglobulinemia. Although these products have demonstrated impressive clinical responses across various B cell malignancies, they have significant and life-threatening side effects, most notably Cytokine Release Syndrome (CRS) and neurological toxicity. Interestingly, the anti-rheumatic bDMARD tocilizumab, an IL-6 receptor antagonist, is approved for the treatment of CRS for six of the seven CAR T cell products and must be available for use prior to reinfusion of the engineered cells in the clinical treatment centre to rapidly manage this side effect, if required. CAR T cell therapies also carry a black box warning of possible secondary T cell malignancies due to the integrating nature of the viral vectors which may disrupt the genome of the genetically engineered T cells (Furlow, 2024). Although CAR T cell therapy has demonstrated impressive results for B cell leukaemias and lymphomas, they have had limited success in targeting solid tumours (Brudno, Maus and Hinrichs, 2024).

The effectiveness of CAR T cell therapy for the treatment of B cell cancers has led to their exploration for the treatment of inflammatory and autoimmune diseases including systemic lupus erythematosus and systemic sclerosis where similar mechanisms of action are desired i.e. depletion of pathogenic immune cells (Chung et al., 2024; Schett et al., 2024). In many ways, their introduction into the clinic mimics rituximab which is clinically approved for the treatment of RA and haematological cancers, with a common mechanism of action of depletion of CD20+ B cells (Chung et al., 2024). Promising case studies in RA patients have recently shown, however, that CAR T cells may provide superior therapeutic advantages over rituximab as a single infusion of these cells can induce sustained drug-free remission in RA (see case studies below). Furthermore, the T cells used for CAR T cell manufacture can be enriched for specific T cell subsets to tailor immune responses (e.g. CD4+ helper T cells, CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, naïve, effector, memory cells central, effector, stem cell-like subtypes or regulatory T cells (Kumar, Connors and Farber, 2018)), while the CAR itself can be engineered to target defined subsets of pathogenic cells including antigen-specific B cells or T cells and thus avoiding the destruction of bystander B cells. These studies and the exciting potential of CAR T cell therapy for the treatment of RA is discussed in the next section.

3. CAR T cell Therapy for the Treatment of RA

3.1. Clinical Studies: CD19 and Tandem CD20-CD19-Directed CAR T Cell Therapy

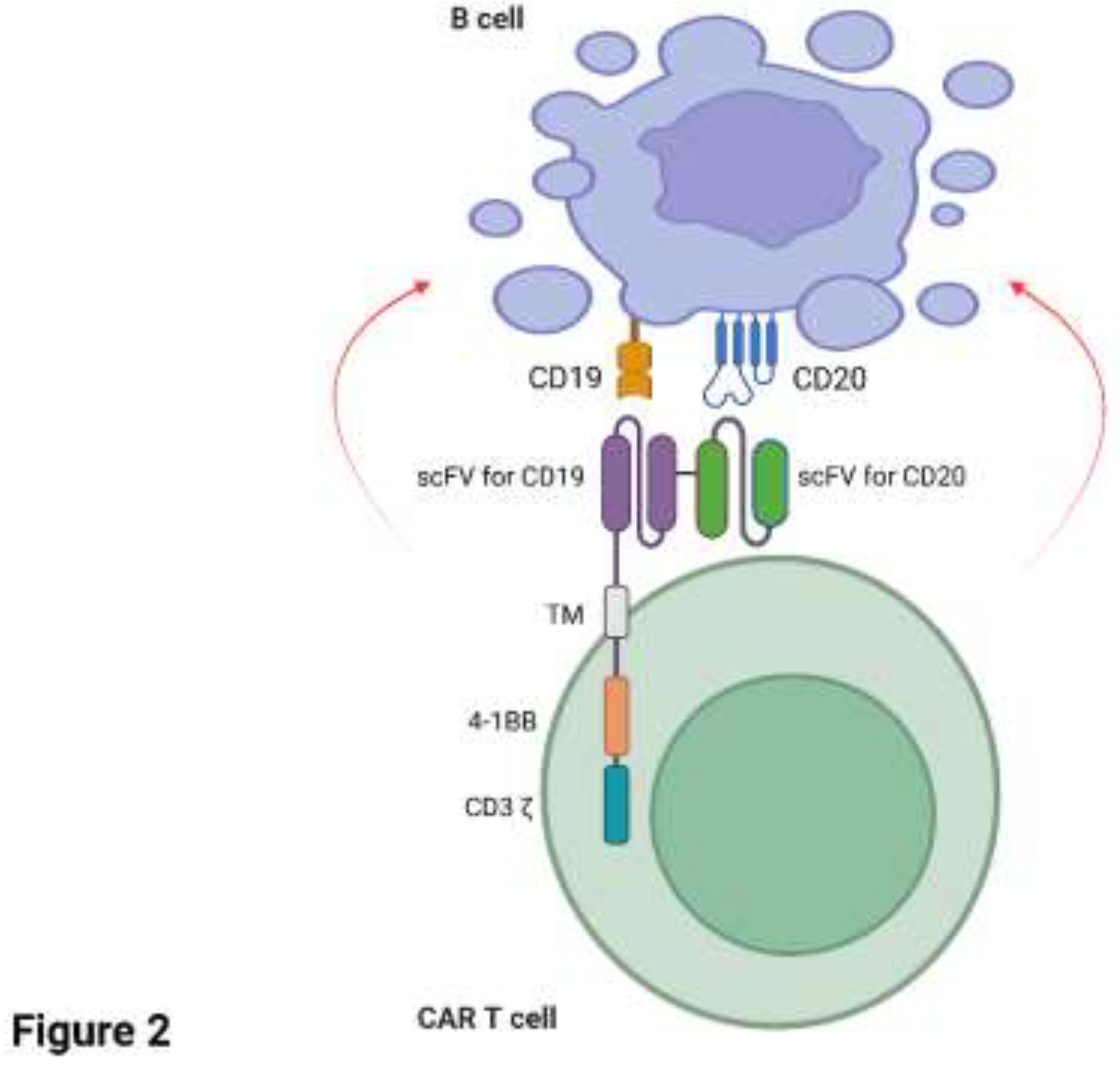

Several case studies have reported remarkable success with CAR T cells targeting CD19+ and/or CD20+ B cells in patients with RA. A recent case study (Szabo et al., 2024) reported a 73-year-old male patient diagnosed with highly active RA in 2011. The patient was treated with low-dose glucocorticoid, MTX, hydroxychloroquine and tocilizumab (anti-IL6 receptor antagonist) and remained on treatment until 2018 with low/moderate disease activity. The patient was subsequently diagnosed with Germinal Centre B cell-like-DLBCL in 2023 and was treated with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, mitoxantrone, vincristine and prednisolone, but was deemed refractory to treatment. On the basis of the patient’s refractory DLBCL, they were enrolled in a phase II randomised, multicentre, open-label clinical trial to study the effect of a novel bispecific CD20-CD19 directed CAR T cell therapy. Since loss of CD19 surface antigen is common in B cell malignancies and appears to be a mechanism for immune evasion with CD19-specific CAR T cell therapy (Cappell and Kochenderfer, 2023) a dual approach of targeting both CD19 and CD20 in tandem aimed to mitigate against a reduction in CAR T cell efficacy should loss of CD19 occur on the target cell. The patient’s T cells were engineered with zamtocabtagene autoleucel (zamto-cel) which is an investigational lentiviral vector encoding a CAR construct specific for both CD20 and CD19 in tandem, linked to the intracellular domains of CD3 and 4-1BB (

Figure 2). The CAR T cell product was well tolerated with mild (grade 1) CRS that was subsequently treated with anti-fever medication. Deep B cell aplasia was noted until 180 days post CAR T cell infusion. As of October 2024, the patient remains in partial response/stable disease for DLBCL one year post-therapy and, intriguingly, is in complete drug-free clinical remission for RA. Notably, the re-emergence of B cells after 180 days post-therapy has not led to the reappearance of RA, indicating that an ‘immune reset’ may have taken place with elimination of the pathogenic B cell clones (Szabo et al., 2024). A very similar case study highlighted a 62-year-old woman diagnosed with Sjogren’s syndrome in 2000 and RA later in 2009, the latter which was difficult-to-treat (Masihuddin et al., 2024). The patient’s treatment for RA consisted of long-term glucocorticoids, two anti-TNFα therapies, anti-IL-6 receptor therapy (toculizumab), a co-stimulation modulator (abatacept) and a JAK inhibitor (tofacitinib). However, both the patient’s Sjogren’s syndrome and RA remained active and unfortunately DLBCL was also diagnosed in 2020. The patient was treated with the clinically approved CD19-targeting CAR T cell therapy axicabtagene ciloleucel (Yescarta) in April 2022 after relapse of DLBCL following standard-of-care rituximab in combination with chemotherapy. Remission of the patient’s lymphoma and RA was achieved with CAR T cell therapy in October 2022 and December 2022, respectively. As of December 2024, the patient remains drug free from RA-directed therapies including corticosteroids, csDMARDs, bDMARDs and tsDMARDs (Masihuddin et al., 2024).

Two case studies have shown excellent results for the treatment of RA co-existing with other inflammatory diseases. In the first of these studies (Haghikia et al., 2024), a 37-year-old woman first diagnosed in 2013 with Myasthenia gravis (a B cell driven autoimmune disease) subsequently developed ACPA-positive RA in 2020. As treatment was focused on MG and involved the use of glucocorticoids and rituximab (treatments that can also be used for RA), no additional therapies were considered for RA. The patient did not respond to these conventional therapies, as well as other therapeutic regimens, and had high levels of disease activity for both Myasthenia gravis and RA concomitant with recurrent infections and a poor quality of life. The patient’s T cells were isolated and engineered with a lentiviral vector encoding a second generation CD19-specific CAR T construct comprising a fully human CD19 binding domain with CD3 and CD28 costimulatory domains (KYV-101, Kyverna Therapeutics). The CAR T cell product was mainly comprised of CD4+ helper T cells and was well tolerated with grade I CRS following infusion. Disease activity scores for both Myasthenia gravis and RA indicated disease remission, with undetectable ACPA levels reported for RA. Circulating B cells were undetectable at day 4 post CAR T cell infusion and slowly returned by day 150. The patient was free of joint pain, was symptom free and was subsequently able to exercise for an hour. Clinical and immunological data was reported up to 150 days post treatment and therefore it be will interesting whether long-term drug free remission is possible. In the second case study (Albach et al., 2025), a 32-year-old female patient with a six-year history of systemic sclerosis and ACPA-positive RA was treated with autologous T cells engineered with KYV-101. The patient developed grade II CRS that was treated with tocilizumab and corticosteroids. Circulating B cell counts were undetectable for 56 days and reappeared in the blood and bone marrow as naïve/transitional B cell subsets by week 16. The level of ACPAs declined below the cut-off values within 21 days and have remained below baseline for 6 months. As of February 2025, the patient remains in remission (Albach et al., 2025).

The four case studies highlighted above showcase the potential for CAR T cell therapies to treat RA. These treatments, however, were complicated by co-existing B cell malignancies or autoimmunity in all four patients. Two additional case studies have been recently reported in difficult-to-treat RA patients without additional malignancies or inflammatory disease (Lidar et al., 2025; Li et al., 2025). The first patient was a 39-year-old woman with erosive seropositive RA who had failed a variety of csDMARDs, bDMARDs (5 x anti-TNFα, 2 x anti-IL-6 receptor, anti-IL-1 and a co-stimulation modulator) and tsDMARDS (3 JAK inhibitors) over a 20-year disease period (Lidar et al., 2025). These therapies resulted in depletion of B cells in peripheral blood yet > 70% CD19+ B cells remained in synovial biopsies. The patient’s T cells were extracted and engineered with a second-generation retroviral vector encoding CD19-specific CAR linked to the intracellular domains from CD3 and CD28. The patient developed grade III CRS and grade IV neurotoxicity one day after infusion of the CAR T cells which required treatment with tocilizumab, anakinra and high dose corticosteroids. After 100 days post-treatment, autoantibody levels declined by 80% and the patient is currently in drug-free remission (Lidar et al., 2025). The second study reported three RA patients that were refractory to a variety of csDMARDs and bDMARDs (notably these patients had not been treated with rituximab) (Li et al., 2025). The patients’ T cells were engineered with a fourth-generation CAR comprising a CD19-targeting scFv, intracellular domains from CD3 and 4-1BB and scFv sequences derived from neutralising anti-IL-6 (sirukumab) and anti-TNFα (adalimumab) to direct secretion of soluble cytokine targeting antibodies. The rationale for investigating this advanced CAR construct was that targeting both B cells and RA-associated inflammatory cytokines may provide additional therapeutic benefit in difficult-to-treat patients. The therapy was tolerated well in all three patients and no serious adverse events including CRS or neurotoxicity were recorded. CD19+ B cells were depleted in all three patients and this correlated with proliferation of the CAR+ T cells in vivo. Clinical responses were impressive, with a reduction in disease activity markers and ablation of autoantibody levels correlating with an improvement of synovitis and reduction in joint swelling. Similar to studies already highlighted above (Haghikia et al., 2024; Szabo et al., 2024; Albach et al., 2025), circulating B cells re-emerged at day 60-90 post CAR T cell infusion and no relapse in RA was observed.

3.2. CAR T cells targeting other antigens for the treatment of RA

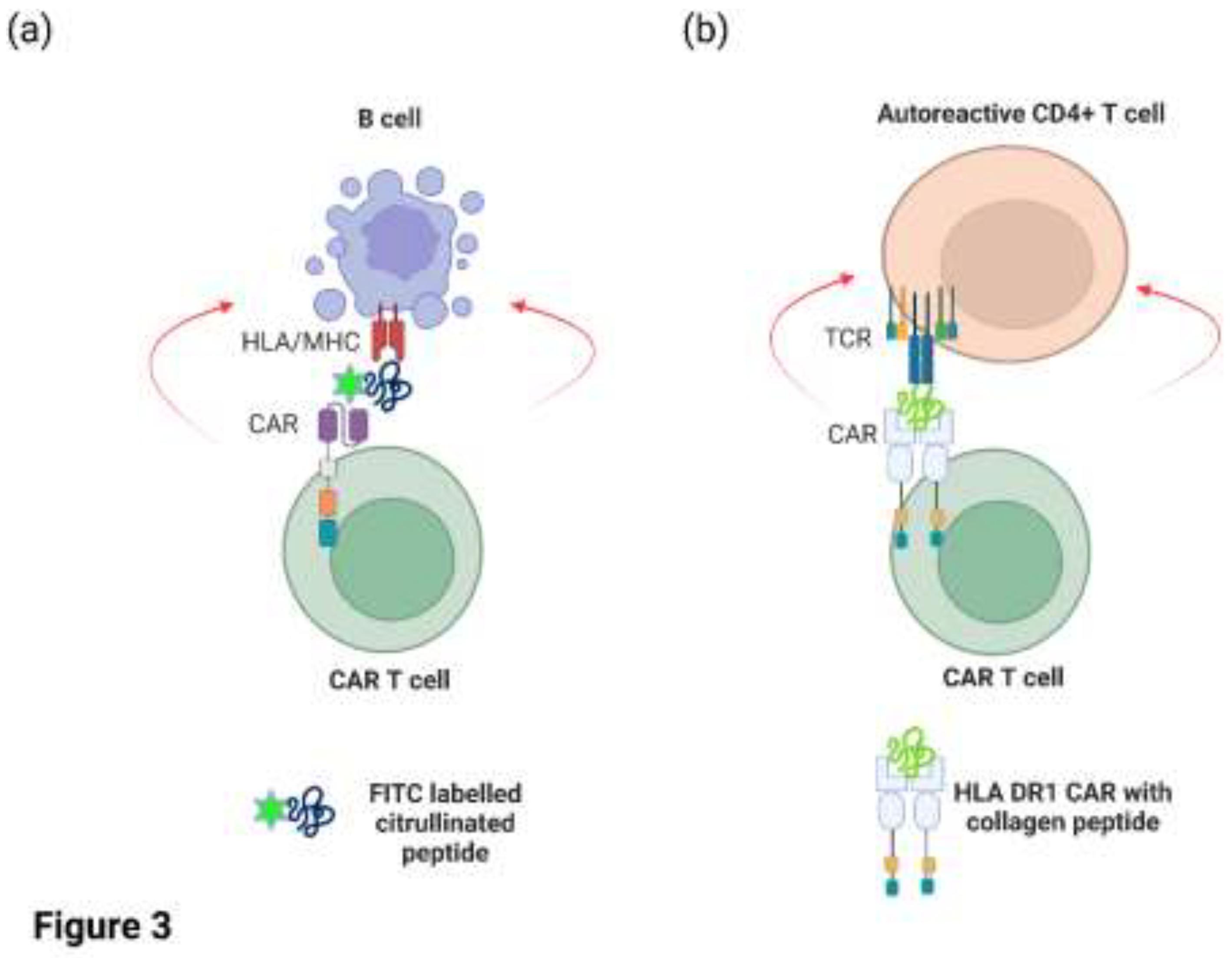

CAR T cells targeting CD19/CD20 on malignant or autoreactive B cells also target healthy B cells, resulting in B cell aplasia and hypogammaglobulinemia. The unintentional targeting of all circulating B cells by CAR T cell therapy has led to the exploration for novel antigens that are selectively expressed on malignant or autoreactive cells relative to healthy cells. Zhang and colleagues elegantly demonstrated that human CAR T cells could be engineered to recognise autoreactive B cells from RA patients in-vitro (Zhang et al., 2021). Primary human T cells were transduced with a lentiviral vector encoding a CAR specific for the fluorescent reporter molecule FITC (

Figure 3a). These engineered T cells were subsequently co-cultured in-vitro with B cells from RA patients in the presence of FITC-labelled citrullinated peptides to direct the CAR T cells to the autoreactive B cells. The CAR T cells specifically lysed peptide-specific autoreactive B cells in the presence of FITC-labelled peptide but had minimal effects on B cells incubated with an irrelevant FITC-labelled peptide (Zhang et al., 2021). In a separate study, the Rosloniec group (Whittington et al., 2022) took a different approach and engineered a novel CAR construct with HLA DR1 (a common antigen-presentation module expressed in RA patients) on the extracellular domain that was covalently linked to an autoantigenic peptide from type II collagen (

Figure 3b). Hence, the HLA DR1/collagen peptide replaced the scFv that is typically found on most CAR molecules. As the HLA DR1 molecule is comprised of two peptide chains (DR1A and DR1B), each chain was linked with the intracellular signalling domain of CD3 and CD28. The rationale of this study was to demonstrate that expression of this CAR construct in murine CD8+ cytotoxic T cells via retroviral expression could directly target and eliminate autoreactive CD4+ T cells with TCRs specific for this HLA/peptide complex. In vitro assays demonstrated that the CAR T cells efficiently recognised and killed CD4+ T cells specific for type II collagen, whereas CD4+ T cells that recognise other antigens were not targeted. Furthermore, the infusion of these CD8+ CAR T cells into a humanised mouse model of autoimmune arthritis reduced disease severity and/or delayed onset, as well as reducing antigen-specific T cell proliferation and autoantibody levels. Thus, these CAR T cells were clearly capable of targeting autoreactive T cells and B cells. The CAR T cell population did not proliferate in vivo, however, and the numbers of engineered cells declined after 10 days post administration which may be due to the low number of target cells in-vivo (Whittington et al., 2022).

As already mentioned, specific T cell subsets can be enriched for CAR T cell manufacture to tailor immune responses (Kumar, Connors and Farber, 2018). One such example is the use of regulatory T cells (Tregs) for CAR T cell therapy as these cells negate inflammatory responses via (a) inhibitory cytokine signalling (IL-10, TGFβ and IL-35 pathways) (b) direct cell: cell contact that suppresses proinflammatory T cells (c) production of metabolites that dampen immunity or (d) sequestration of co-stimulatory signals on antigen presenting cells (Vignali, Collison and Workman, 2008). An unpublished study reported engineering of human Tregs with a CAR containing an extracellular binding domain specific for citrullinated vimentin which is a protein found in the synovium of RA patients. The CAR expressing Treg cells proliferated in response to citrullinated vimentin (but not an unmodified protein), produced IL-10 and suppressed the proliferation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Furthermore, the CAR Tregs were activated when incubated with synovial fluid from RA patients.

Another interesting target that could potentially be targeted with CAR T cells is fibroblast-associated protein (FAP). FAP is a type II transmembrane serine protease that cleaves peptide bonds between proline and other amino acids (reviewed in (Chu, 2022)). FAP expression is normally restricted to foetal tissue and is not expressed in healthy adult tissue other than bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells. Interestingly, FAP expression is upregulated in stromal fibroblasts of more than 90% of epithelial cancers, as well as wound healing and fibrotic diseases (Chu, 2022). The restricted nature of FAP expression makes it a promising target for CAR T cell therapy because it may allow for selective targeting of cancer cells or fibrotic (scar) tissue, with minimal damage to healthy tissues. FAP-targeting CAR T cells have shown promising results in vitro for the treatment of solid cancers (Bughda et al., 2021; Shahvali et al., 2023), and infusion of FAP-targeting CAR T cells into mice with hypertensive cardiac injury (and concomitant expression of FAP) eliminated activated fibroblasts, significantly reduced cardiac fibrosis and restored cardiac function (Aghajanian et al., 2019; Rurik et al., 2022). FAP is also highly expressed in the synovium of RA patients, making it an intriguing antigen to target with CAR T cells (Chu, 2022). FAP is not expressed in the synovium of healthy mice or in models of osteoarthritis, suggesting that the targeting this protein should have minimal effects on non-activated fibroblasts and healthy tissues. FAP-targeting CAR T cells have not been evaluated in pre-clinical models of RA to date, but if successful, they could provide the first RA therapy that does not directly target immune cells and inflammation. In summary, these studies demonstrate the potential for selectively targeting autoreactive B cells or T cells, as well as enriching for T cell subsets to tailor immune responses for the treatment of RA.

4. Conclusions and Future Studies

CAR T cell therapy has shown unprecedented results for the treatment of RA in difficult-to-treat patients via depletion of CD19+/CD20+ B cells. The clinical data, while preliminary, suggests that a single infusion of these cell-based therapies could mediate long term suppression of inflammatory disease, an ‘immune reset’ and drug-free remission (Haghikia et al., 2024; Masihuddin et al., 2024; Szabo et al., 2024; Albach et al., 2025; Lidar et al., 2025; Li et al., 2025). Due to their success in treating B cell leukaemia and lymphoma, there now exists an enormous body of clinical and regulatory data on CAR T cell manufacture, efficacy and side-effects, much of which can be leveraged for the treatment of RA and other autoimmune diseases. It should be noted however that only seven RA patients have been treated with CAR T cell therapy to date, and these were mostly individual case studies. Future RA studies will therefore need to evaluate larger cohorts of patients in randomised clinical trials where CAR T cell therapy is compared to standard-of-care treatments. Indeed, two clinical trials are currently underway or will shortly recruit RA patients to evaluate CAR T cell therapy (

Table 3). One of these trials (NCT06475495) will engineer T cells with the investigational viral vector KYV-101 encoding the CD19-specific CAR and compare their efficacy to rituximab treatment. It will be interesting to determine whether infusion of CAR T cells provides long-term remission of RA in a direct head-to-head comparison with rituximab. Rituximab has been reported as only partially depleting synovial B cells in RA patients (Kavanaugh et al., 2008; Thurlings et al., 2008) and therefore it will be useful to determine if the impressive results with CAR T cell therapy correlates with trafficking into the joints and depletion of synovial B cells.

While CAR T cells have shown impressive results in B cell cancers, their serious and life-threatening side effects requires availability of the bDMARD tocilizumab in the infusion centre to rapidly manage CRS. The inclusion of black box warnings on each FDA drug label to “Do not administer [CAR T cell therapy trade name] to patients with active infection or inflammatory disorders.”, is obvious given that CAR T cell-mediated CRS would exacerbate inflammatory disease. While these warnings are applied in the context of cancer patients being considered for CAR T cell therapy, it is interesting that these therapies have now been infused in cancer patients with co-existing RA as well as RA patients without cancer. It has been reported that CD19-directed CAR T cell therapy for autoimmune disease induces low/manageable levels of CRS and neurotoxicity in patients and appears to be milder compared to cancer patients (Chung et al., 2024; Schett et al., 2024). However, as highlighted in the clinical case studies summarised in this review, grade II/III CRS and grade IV neurotoxicity were reported in some RA patients who received CAR T cell therapy, necessitating the use of tocilizumab to manage CRS (Albach et al., 2025; Lidar et al., 2025). This highlights that side effects of CAR T cell therapy will need to be monitored closely in future trials for RA. Interestingly, three RA patients treated with fourth-generation CAR T cells co-expressing neutralising anti-IL-6 and anti-TNFα antibodies showed excellent responses and did not experience any side effects (Li et al., 2025). The use of tocilizumab to treat CRS in RA patients has added an interesting question as to whether blocking the IL-6 pathway has a dual role in controlling CRS in addition to a therapeutic benefit for the treatment of RA. Randomisation of RA patients for treatment with second-generation CAR T cells or with fourth generation CAR T cells co-expressing neutralising IL-6 antibodies may be a novel way of addressing this important clinical question in the future.

CAR T cells also carry an additional black box warning of secondary T cell malignancies in patients who received these therapies which is likely due to the integration of the CAR construct into the T cell genome using retroviral or lentiviral vectors. Transient expression of CARs in T cells may be a novel way of avoiding secondary malignancies, as the construct will be lost following replication of the T cells. As an example, the Epstein group used lipid nanoparticles to deliver mRNA encoding a FAP-targeting CAR into murine T cells in vivo for the treatment of cardiac fibrosis (Rurik et al., 2022). The nanoparticles were coated with antibodies to CD5 to enable targeting of T cells, as CD5 is highly expressed on T cells and on some subsets of B cells. Up to 25% of circulating T cells in the mice were engineered with the FAP-specific CAR which correlated with regression of cardiac injury. CAR expression was transient with the loss of this receptor on T cells one-week post-infusion (Rurik et al., 2022). A similar in-vivo strategy using targeted lipid nanoparticles could be used to deliver CD19-targeting or FAP-specific CAR mRNA into T cells with much lower risks of secondary malignancies.

In summary, CAR T cell therapy holds enormous promise for the treatment of RA, in particularly difficult-to-treat patients. This can be achieved by targeting well characterised antigens (CD19/CD20+ B cells) or novel antigens (e.g. immune cells recognising citrullinated peptide antigens or FAP expressing fibroblasts) in broad or selected T cell subsets using a variety of novel CAR constructs delivered by viral or non-viral approaches.

References

- Aghajanian, H.; et al. Targeting cardiac fibrosis with engineered T cells. Nature 2019, 573, 430–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albach, F.N.; et al. Targeting autoimmunity with CD19-CAR T-cell therapy: efficacy and seroconversion in diffuse systemic sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology 2025, keaf077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alivernini, S., Firestein, G.S. and McInnes, I.B. The pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Immunity 2022, 55, 2255–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brudno, J.N., Maus, M.V. and Hinrichs, C.S. CAR T Cells and T-Cell Therapies for Cancer: A Translational Science Review. JAMA 2024, 332, 1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bughda, R.; et al. Fibroblast Activation Protein (FAP)-Targeted CAR-T Cells: Launching an Attack on Tumor Stroma. ImmunoTargets and Therapy 2021, 10, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappell, K.M. and Kochenderfer, J.N. Long-term outcomes following CAR T cell therapy: what we know so far. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology 2023, 20, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.-Q. Highlights of Strategies Targeting Fibroblasts for Novel Therapies for Rheumatoid Arthritis. Frontiers in Medicine 2022, 9, 846300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.B.; et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy for autoimmune disease. Nature Reviews Immunology 2024, 24, 830–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firestein, G.S.; McInnes, I.B. Immunopathogenesis of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Immunity 2017, 46, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraenkel, L.; et al. 2021 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Care & Research 2021, 73, 924–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlow, B. FDA investigates risk of secondary lymphomas after CAR-T immunotherapy. The Lancet Oncology 2024, 25, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haghikia, A.; et al. Clinical efficacy and autoantibody seroconversion with CD19-CAR T cell therapy in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis and coexisting myasthenia gravis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2024, 83, 1597–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- June, C.H.; et al. CAR T cell immunotherapy for human cancer. Science 2018, 359, 1361–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanaugh, A.; et al. Assessment of rituximab’s immunomodulatory synovial effects (ARISE trial). 1: clinical and synovial biomarker results. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2008, 67, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klareskog, L.; et al. A new model for an etiology of rheumatoid arthritis: Smoking may trigger HLA–DR (shared epitope)–restricted immune reactions to autoantigens modified by citrullination. Arthritis & Rheumatism 2006, 54, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.V., Connors, T.J. and Farber, D.L. Human T. Human T Cell Development, Localization, and Function throughout Life. Immunity 2018, 48, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; et al. Fourth-generation chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy is tolerable and efficacious in treatment-resistant rheumatoid arthritis. Cell Research 2025, 35, 220–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lidar, M.; et al. CD-19 CAR-T cells for polyrefractory rheumatoid arthritis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2025, 84, 370–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masihuddin, A.; et al. Remission of lymphoma and rheumatoid arthritis following anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Rheumatology 2024, keae714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, G. and Van Vollenhoven, R.F. Sustained biologic-free and drug-free remission in rheumatoid arthritis, where are we now? Arthritis Research & Therapy 2015, 17, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rurik, J.G.; et al. CAR T cells produced in vivo to treat cardiac injury. Science 2022, 375, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schett, G.; et al. Advancements and challenges in CAR T cell therapy in autoimmune diseases. Nature Reviews Rheumatology 2024, 20, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahvali, S.; et al. Targeting fibroblast activation protein (FAP): advances in CAR-T cell, antibody, and vaccine in cancer immunotherapy. Drug Delivery and Translational Research 2023, 13, 2041–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolen, J.S.; et al. Rheumatoid arthritis. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 2018, 4, 18001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolen, J.S.; et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2022 update. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2023, 82, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, D.; et al. Sustained drug-free remission in rheumatoid arthritis associated with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma following tandem CD20-CD19-directed non-cryopreserved CAR-T cell therapy using zamtocabtagene autoleucel. RMD Open 2024, 10, e004727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurlings, R.M.; et al. Synovial tissue response to rituximab: mechanism of action and identification of biomarkers of response. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2008, 67, 917–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokarew, N.; et al. Teaching an old dog new tricks: next-generation CAR T cells. British Journal of Cancer 2019, 120, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignali, D.A.A., Collison, L.W. and Workman, C.J. How regulatory T cells work. Nature Reviews Immunology 2008, 8, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittington, K.B.; et al. CD8+ T Cells Expressing an HLA-DR1 Chimeric Antigen Receptor Target Autoimmune CD4+ T Cells in an Antigen-Specific Manner and Inhibit the Development of Autoimmune Arthritis. The Journal of Immunology 2022, 208, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; et al. In vitro elimination of autoreactive B cells from rheumatoid arthritis patients by universal chimeric antigen receptor T cells. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2021, 80, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).