Submitted:

20 March 2025

Posted:

21 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Fundamental DC-DC Switching Converters [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]

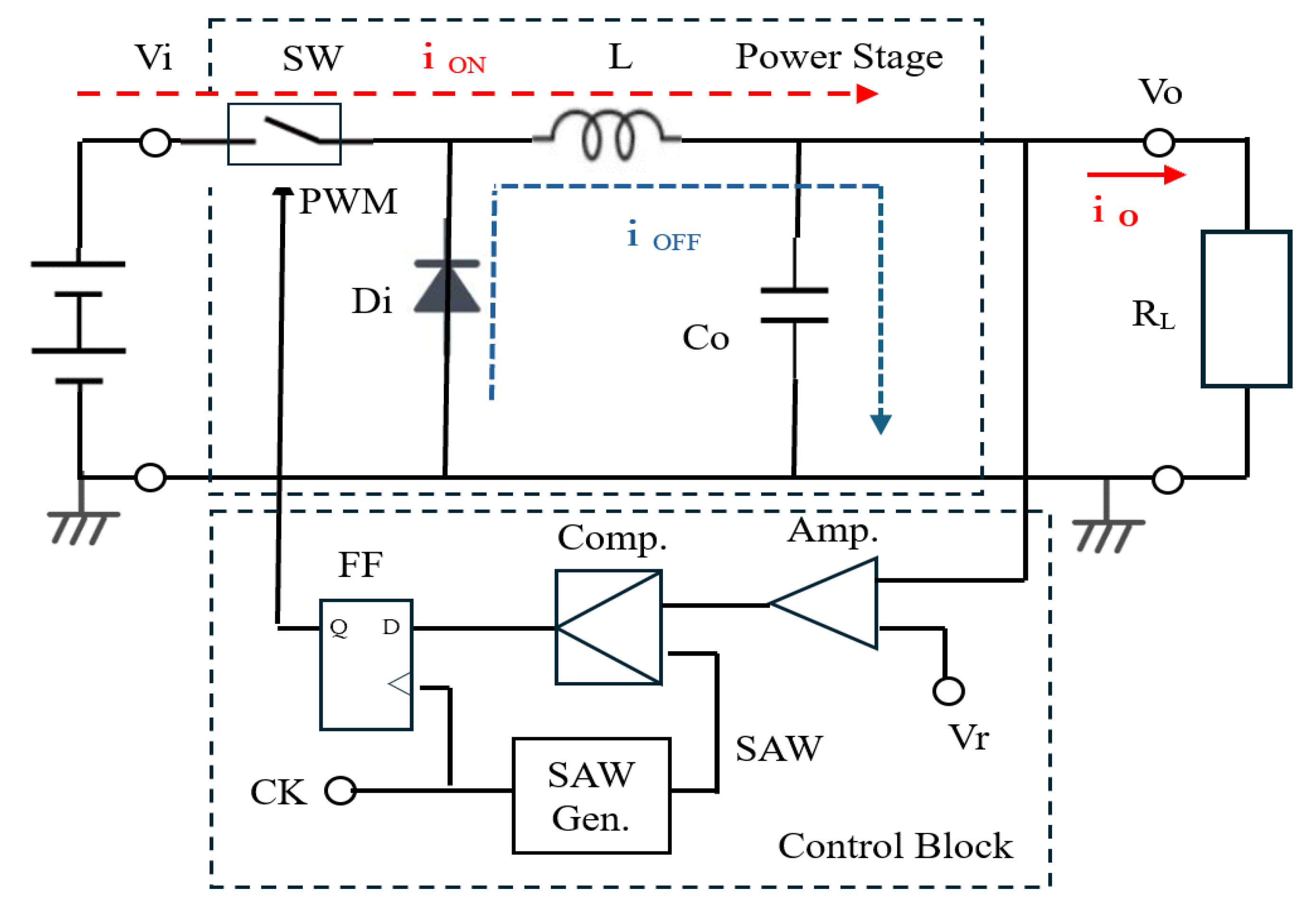

2.1. Buck Converter with PWM Control

2.2. Boost Converter

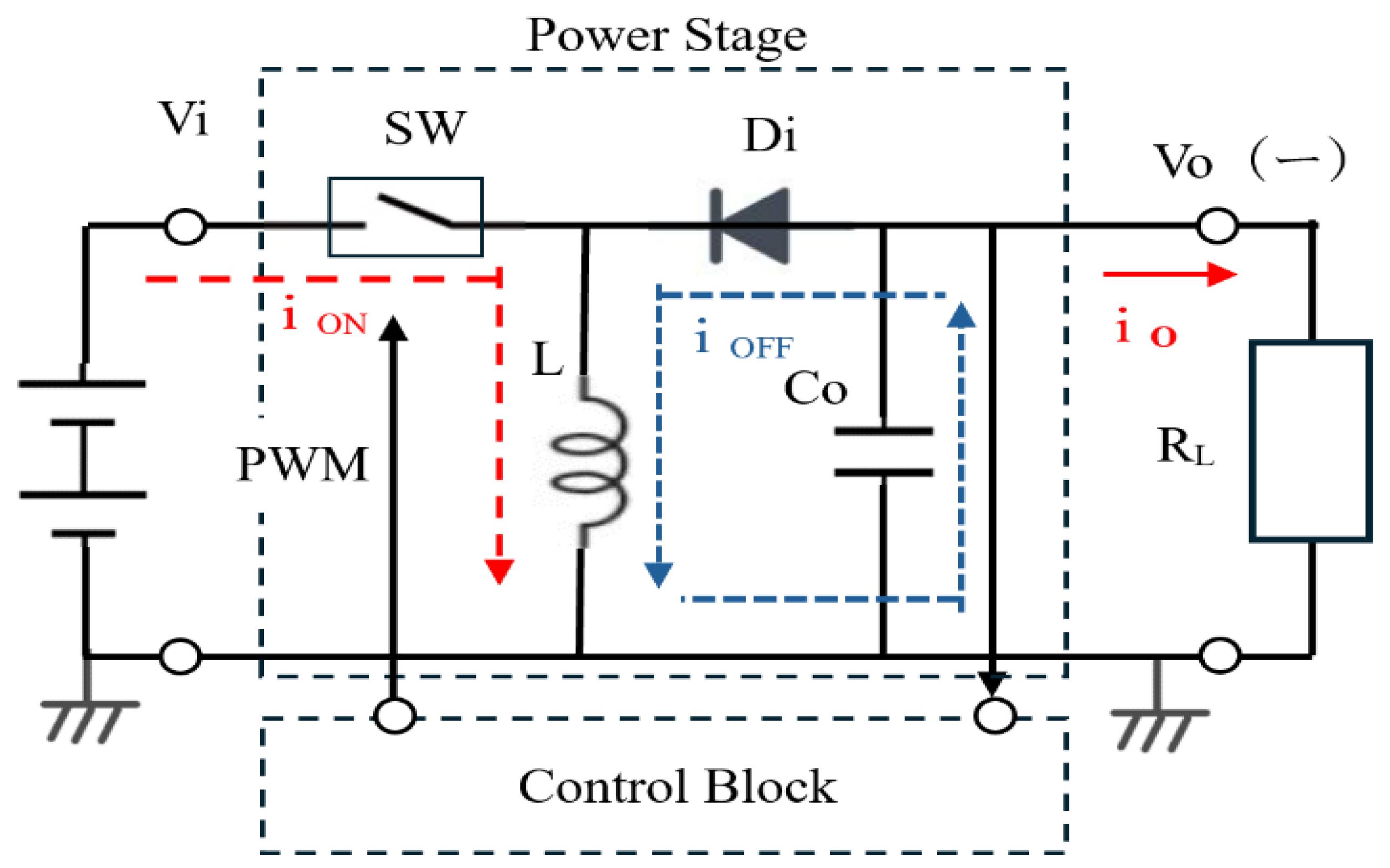

2.3. Buck-Boost Converter

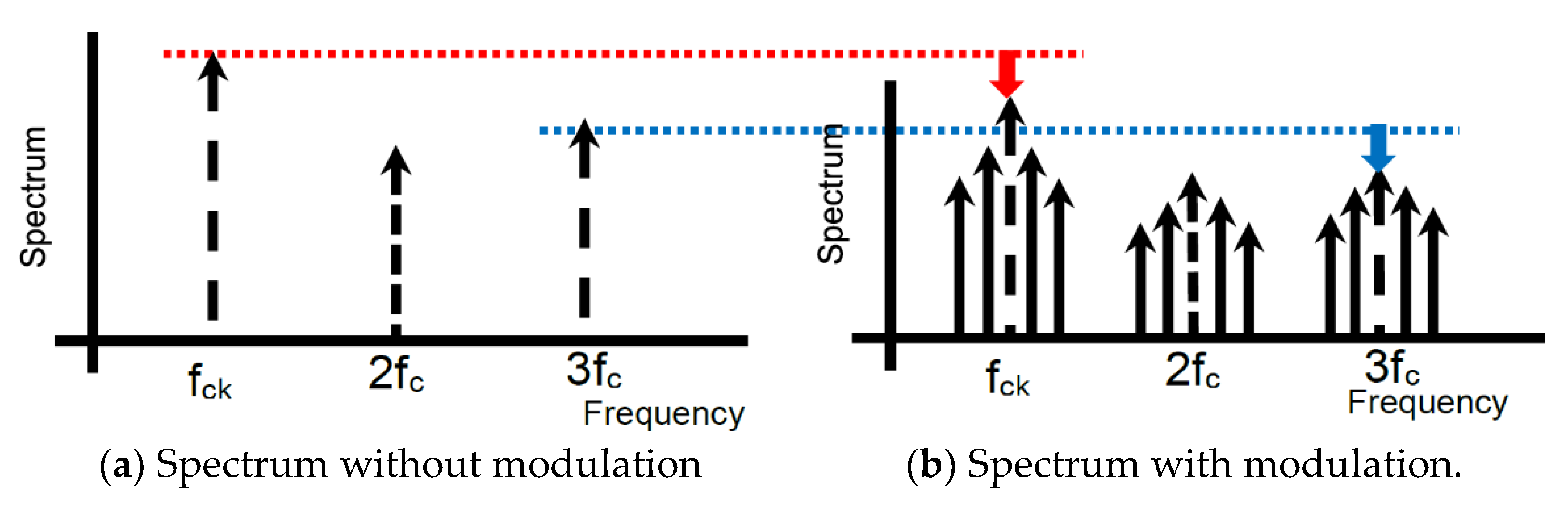

3. Conventional Method of EMI Reduction with Suppressing Diffusion [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]

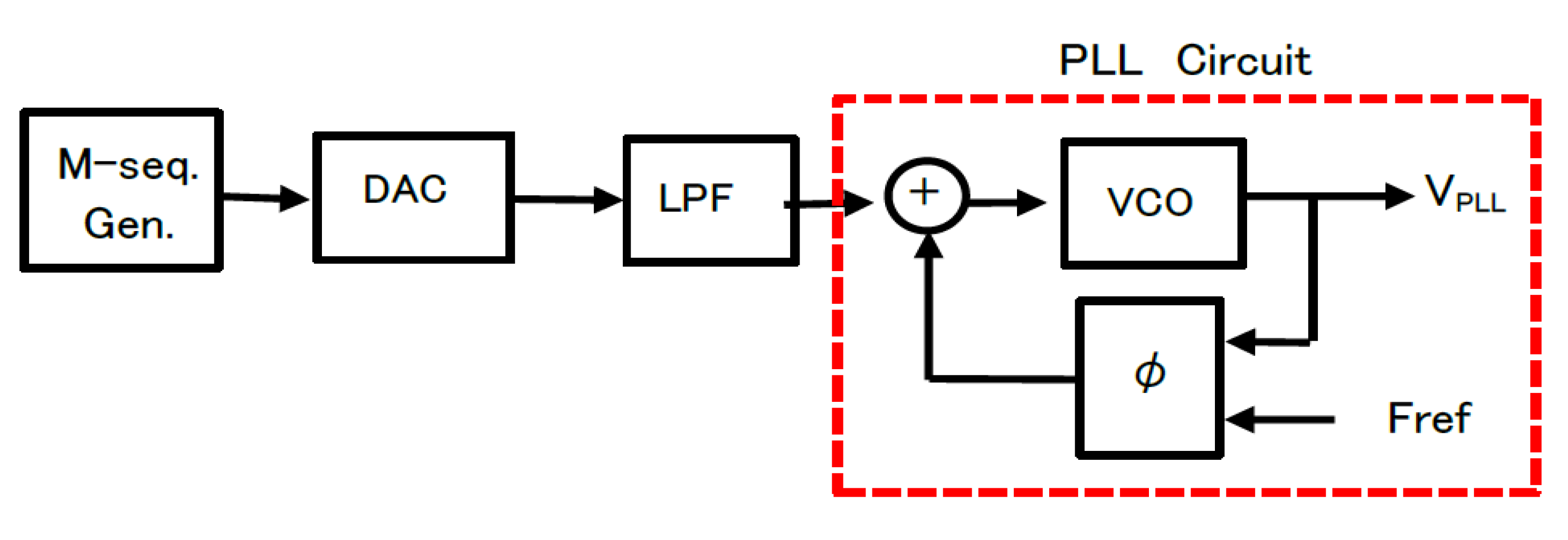

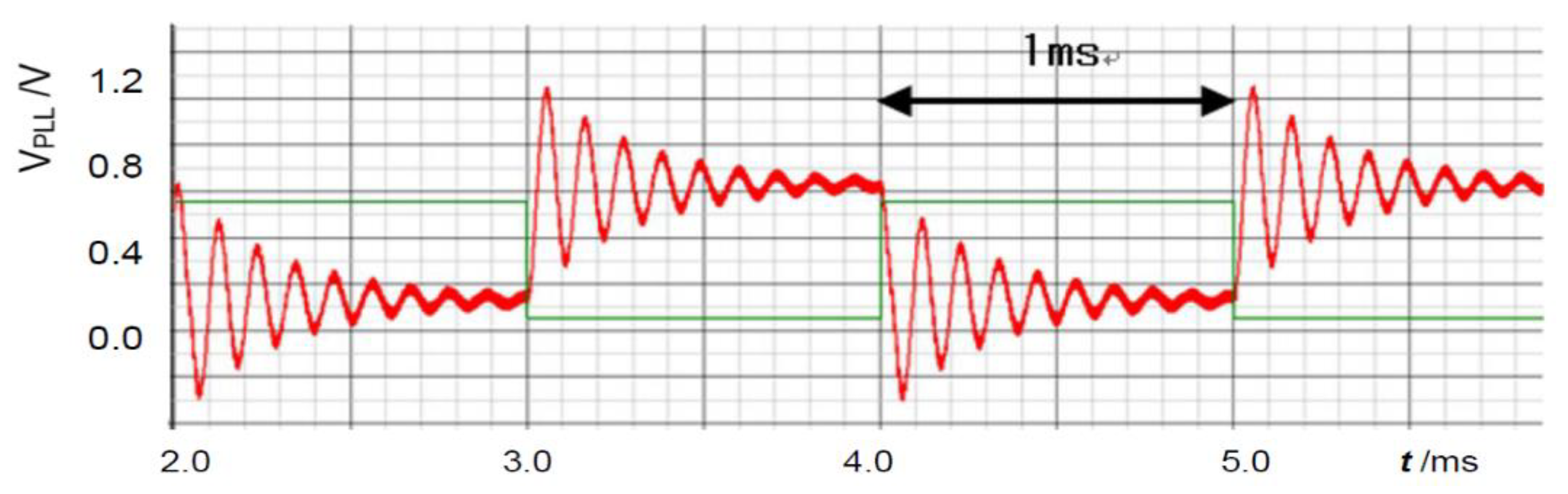

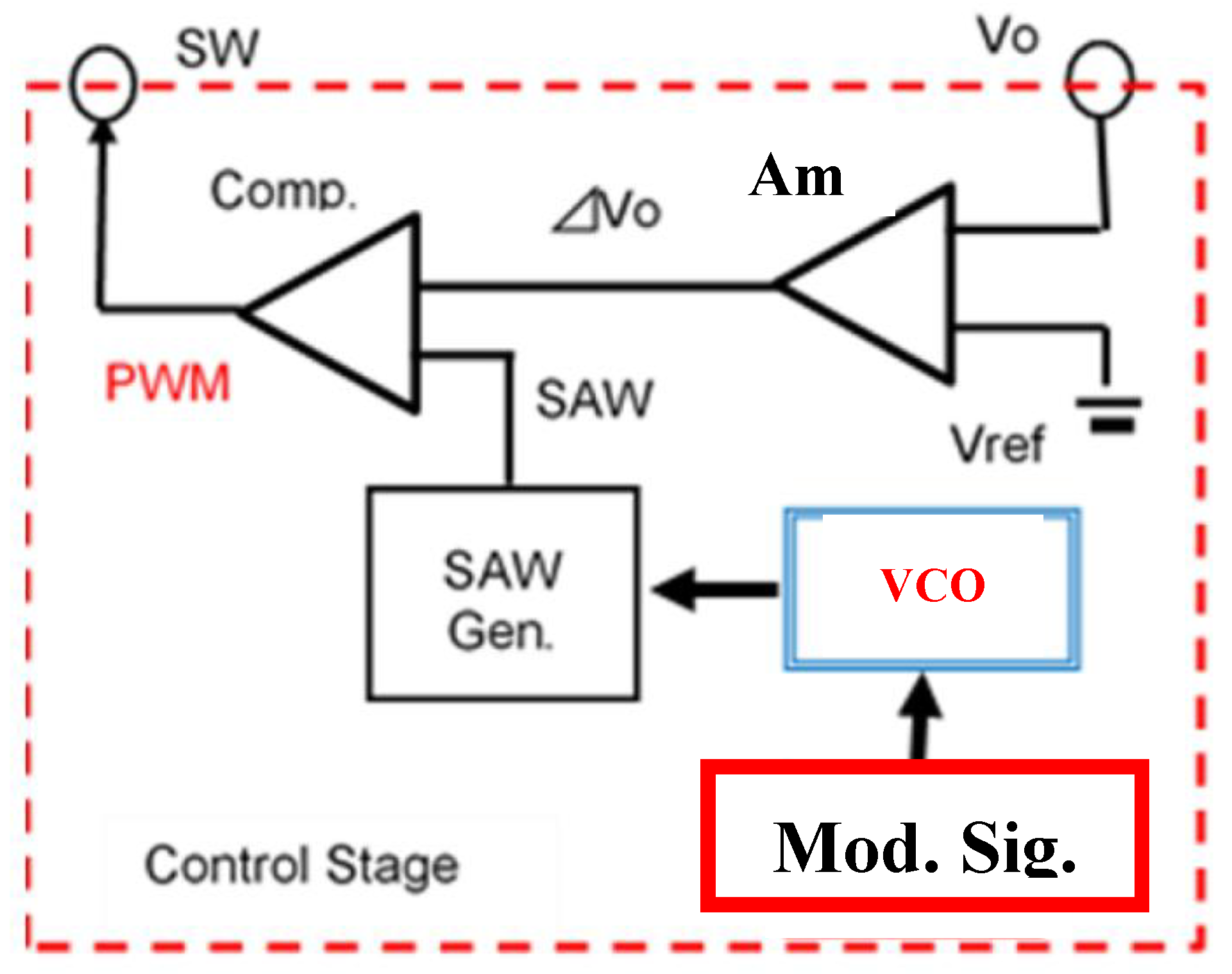

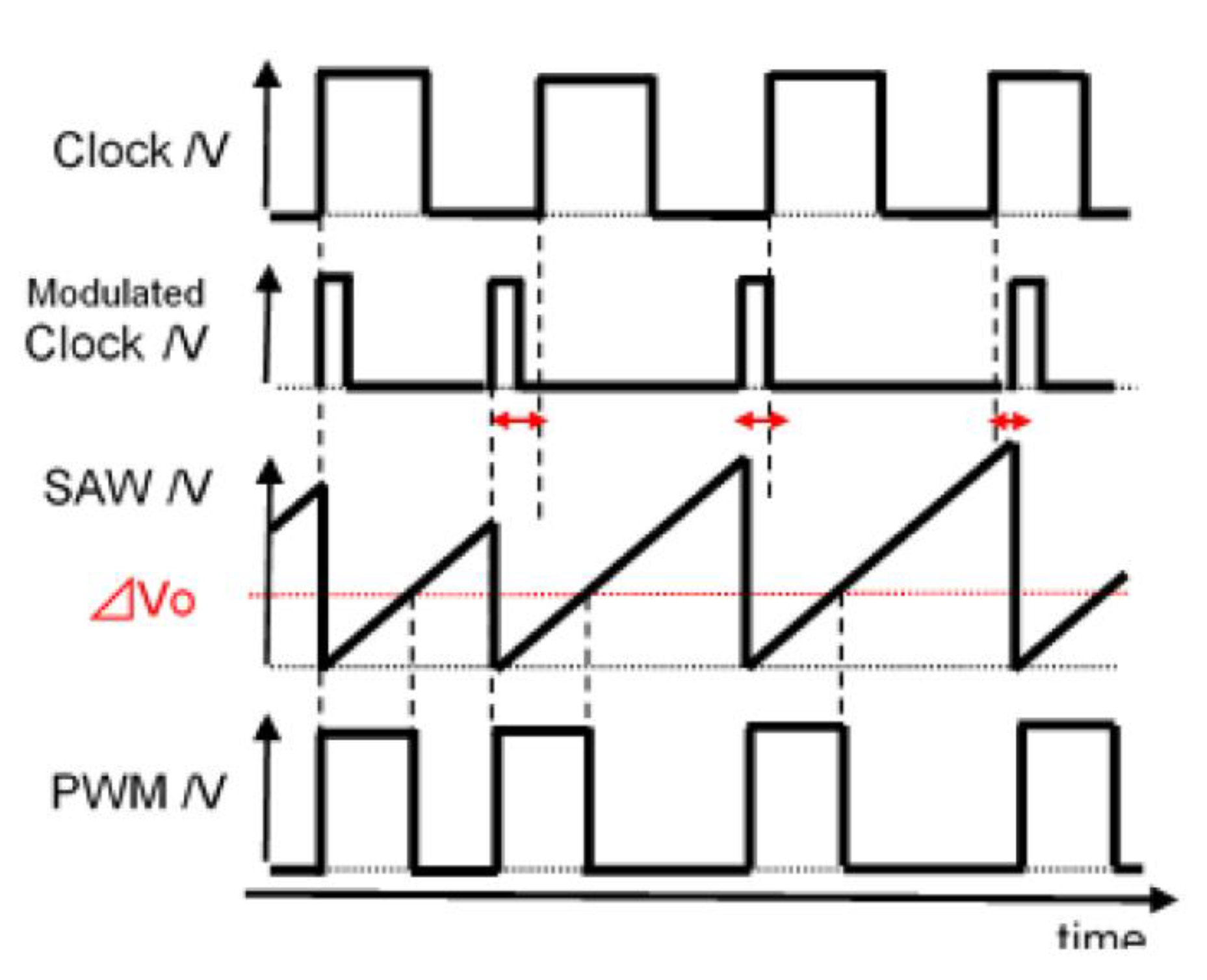

3.1. Frequency Modulation with Analog Spread Spectrum Clock Generator

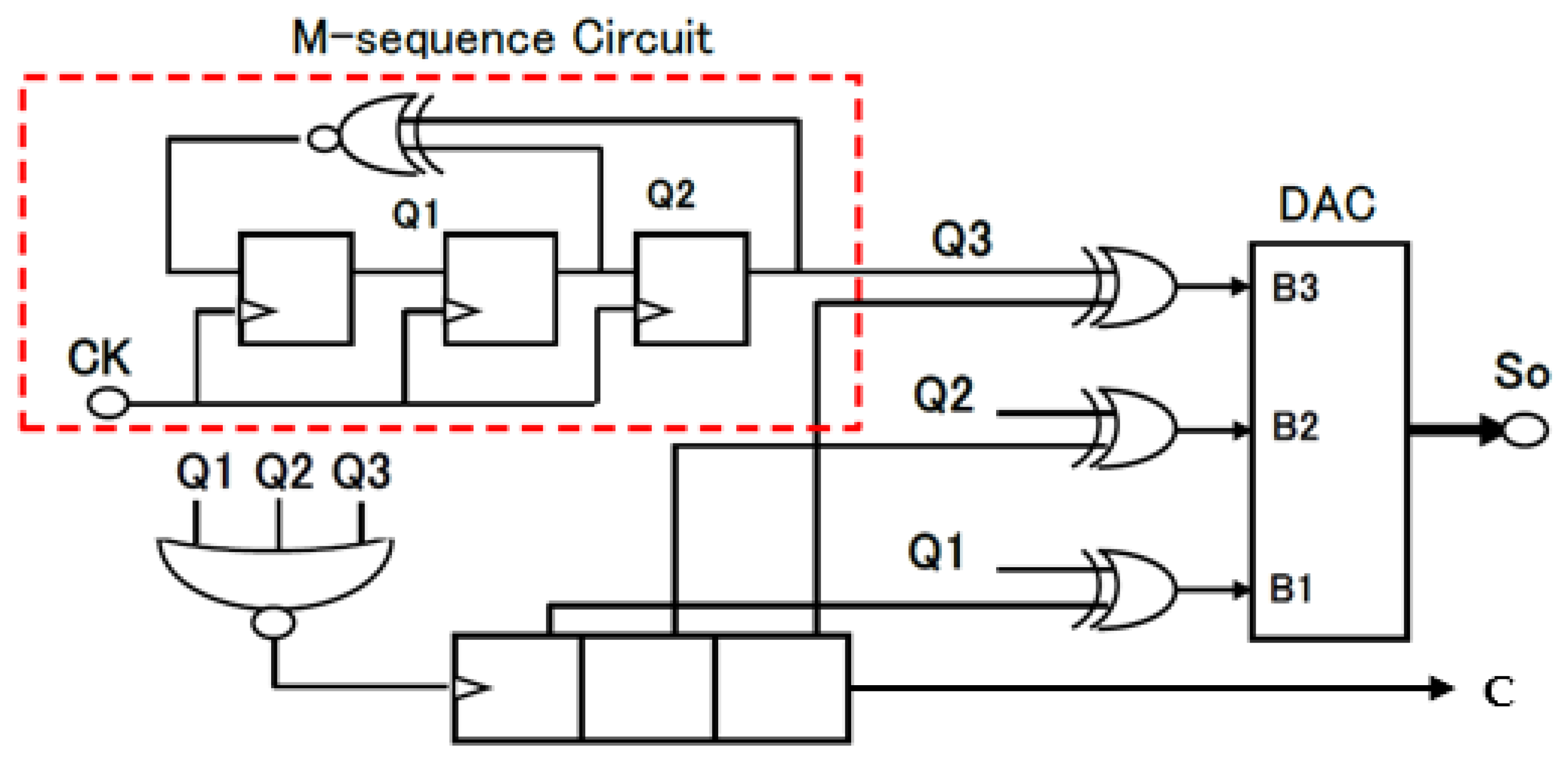

3.2. Basic Digital Frequency Modulation with LFSR

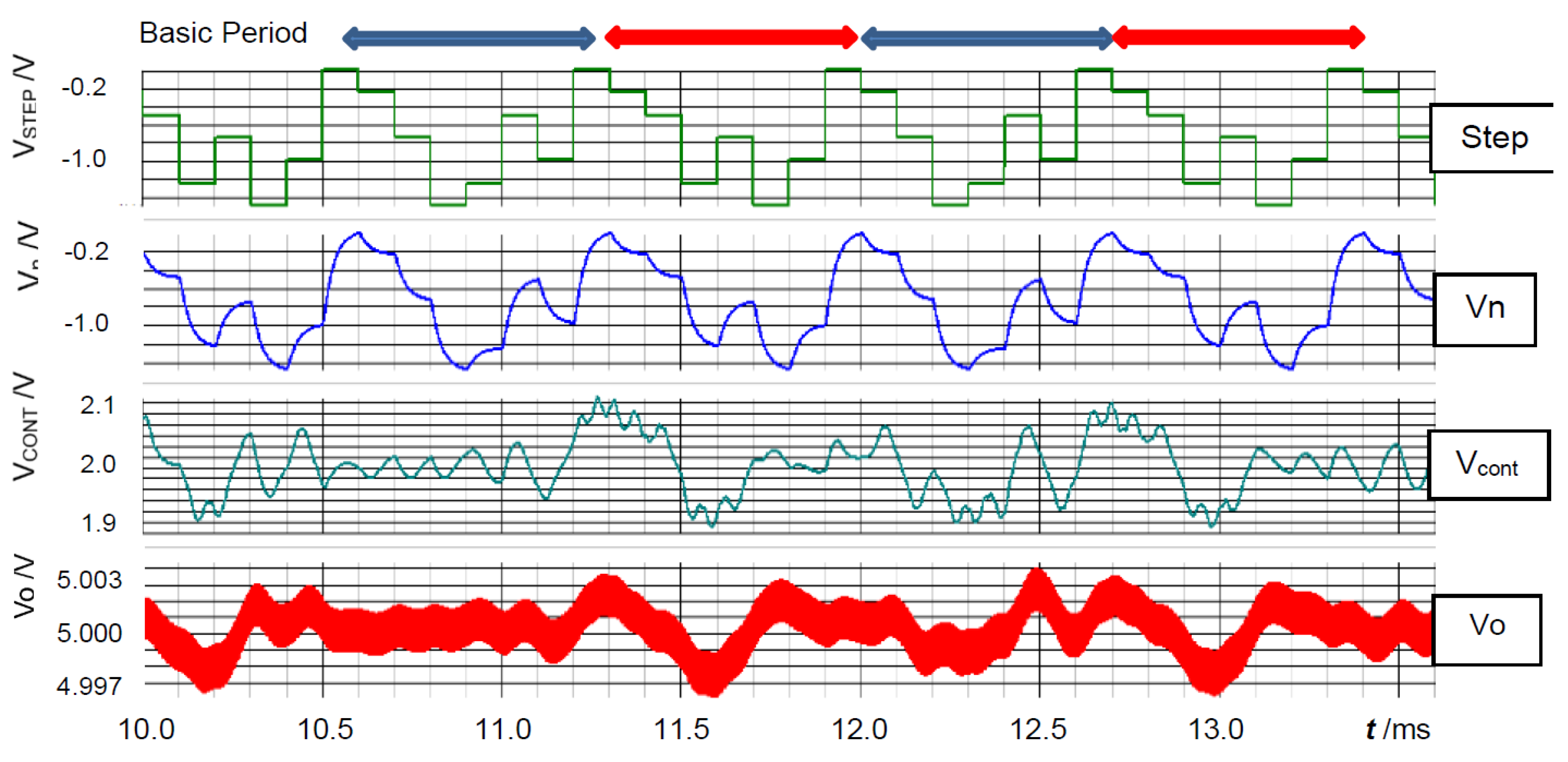

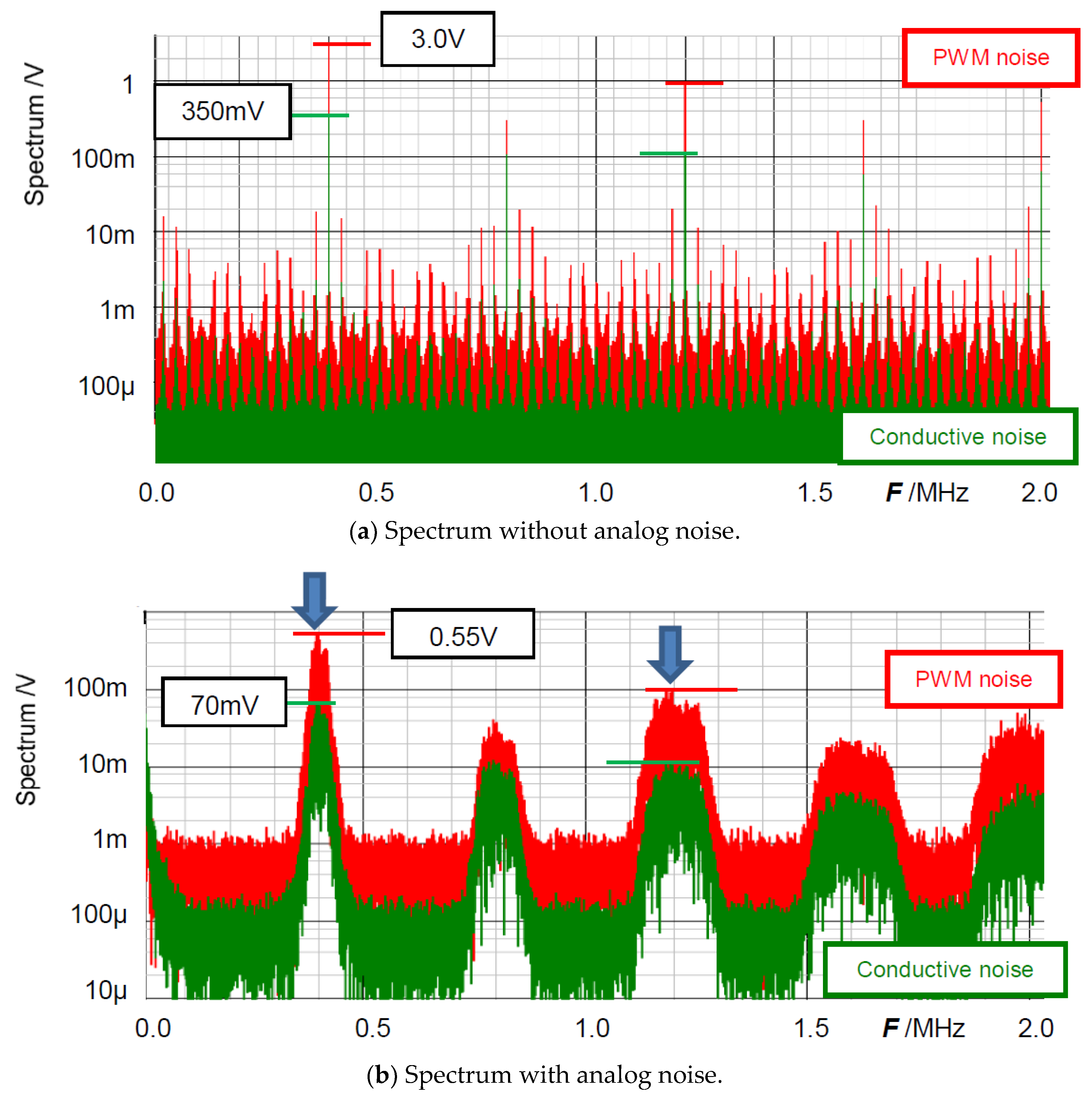

3.3. Analog Noise Generators using Bit Operation

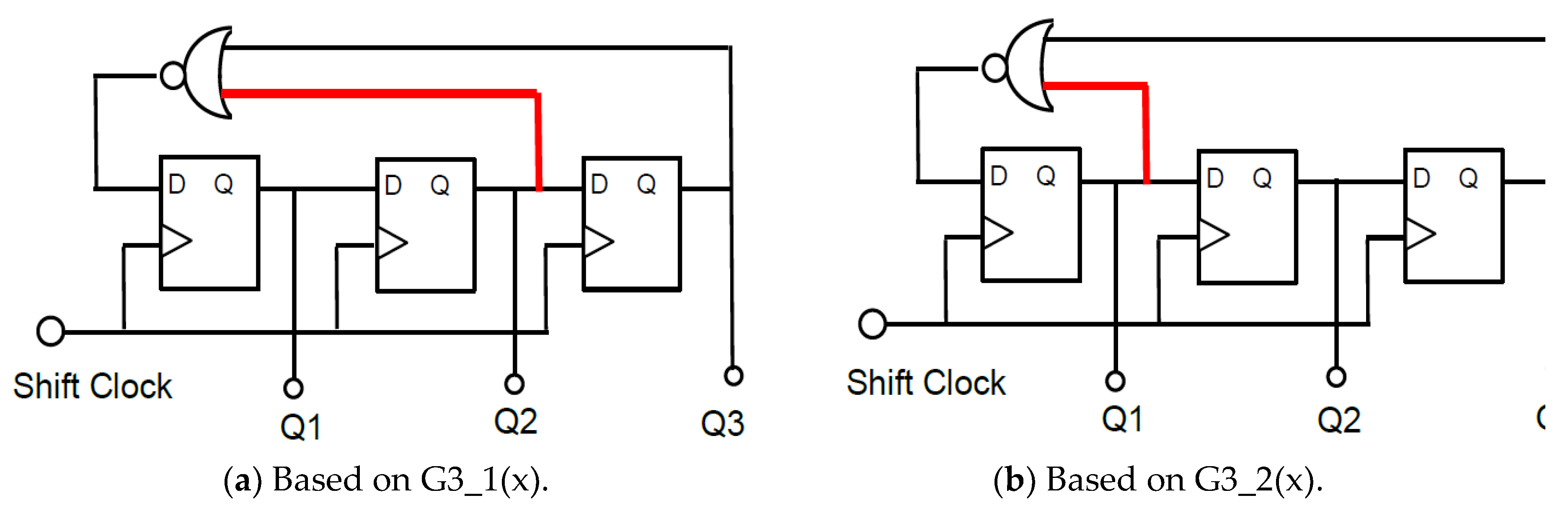

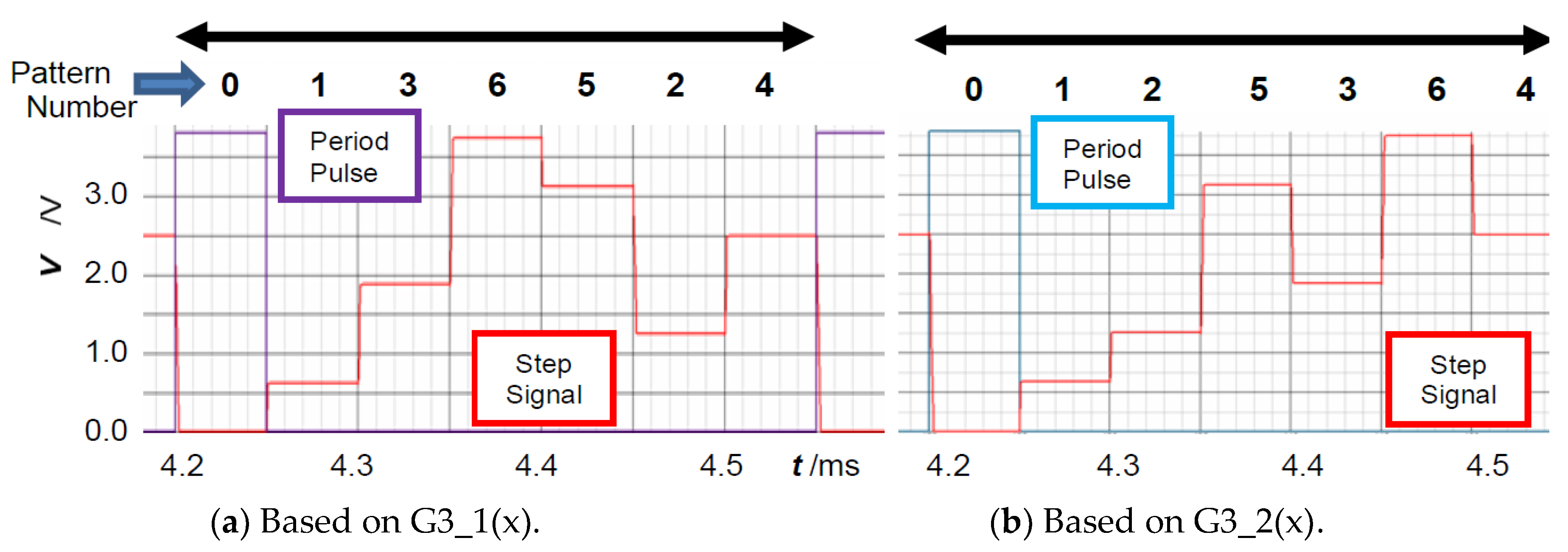

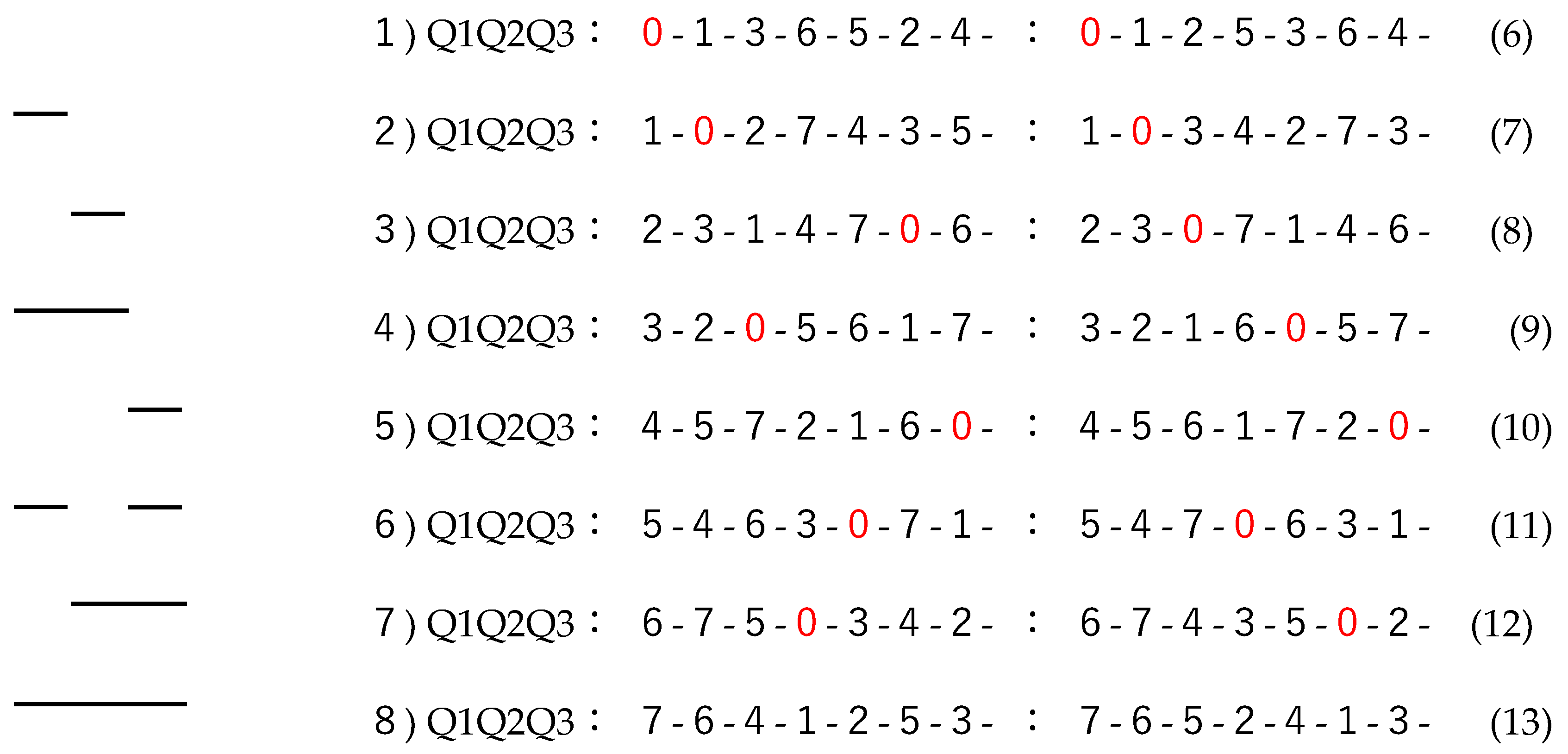

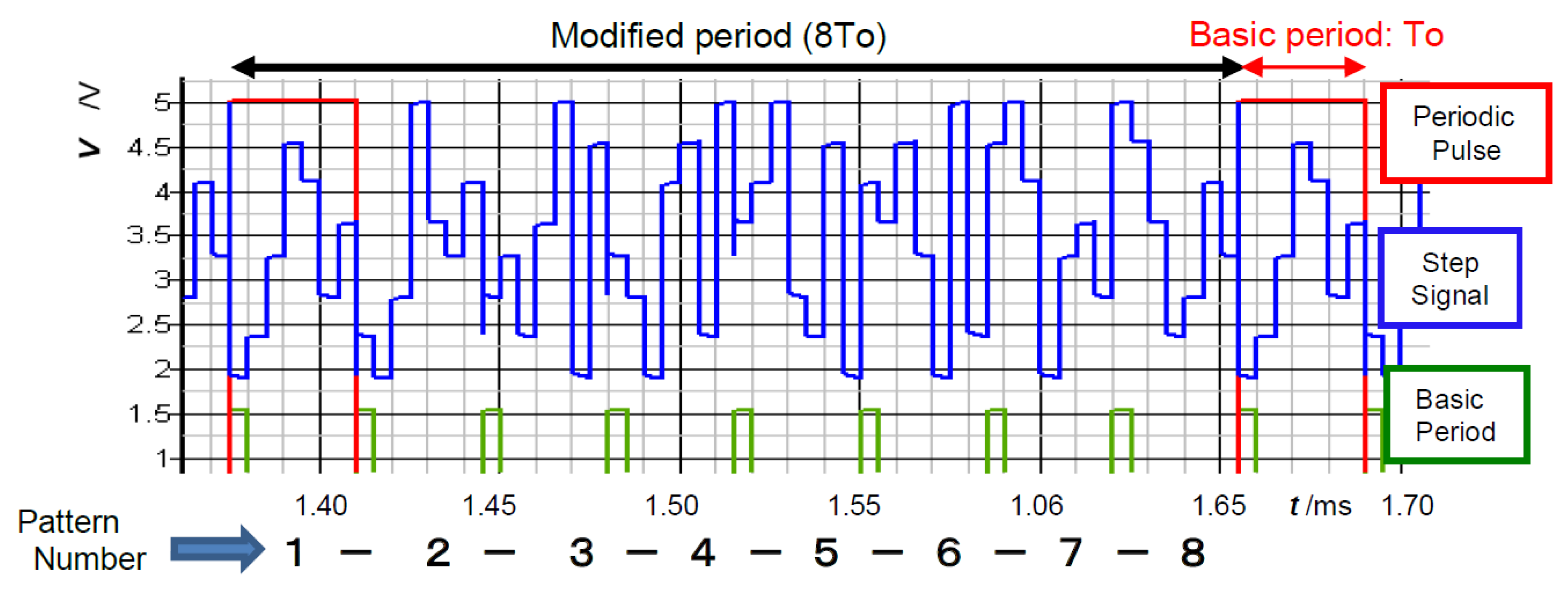

3.4. Pattern Generator Using Bit-Inverse and Bit-Exchange and Simulation Results

3.5. Expansion of Number of Pseudo Analog Noise Generator Bits

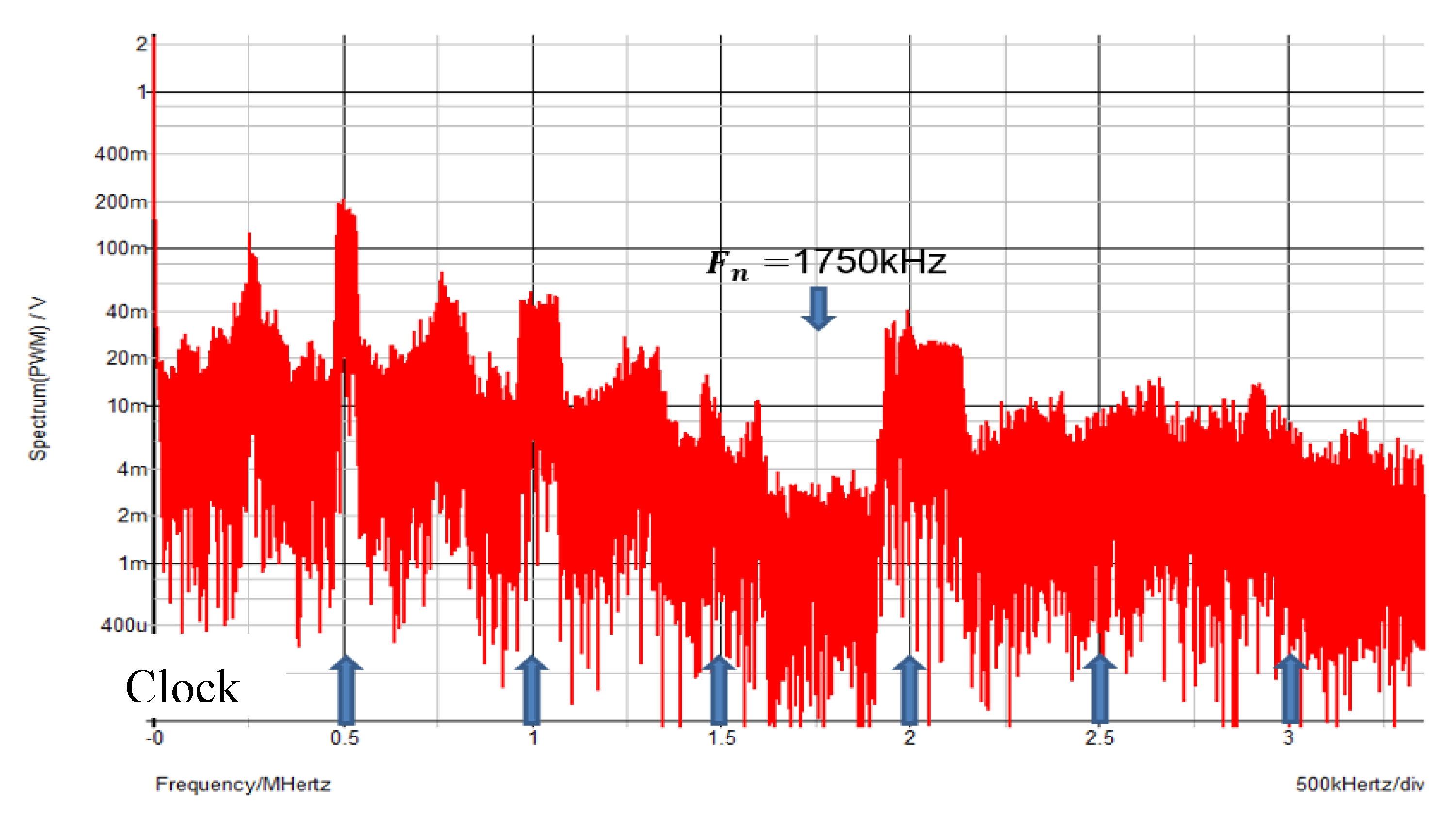

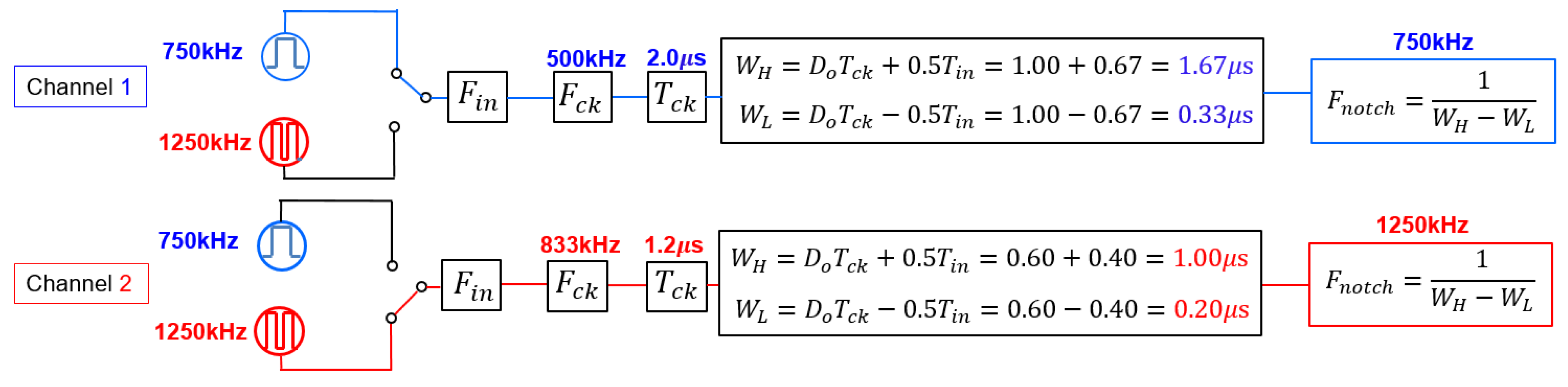

4. Notch Band Select with Pulse Coding Control [25,26,27,28]

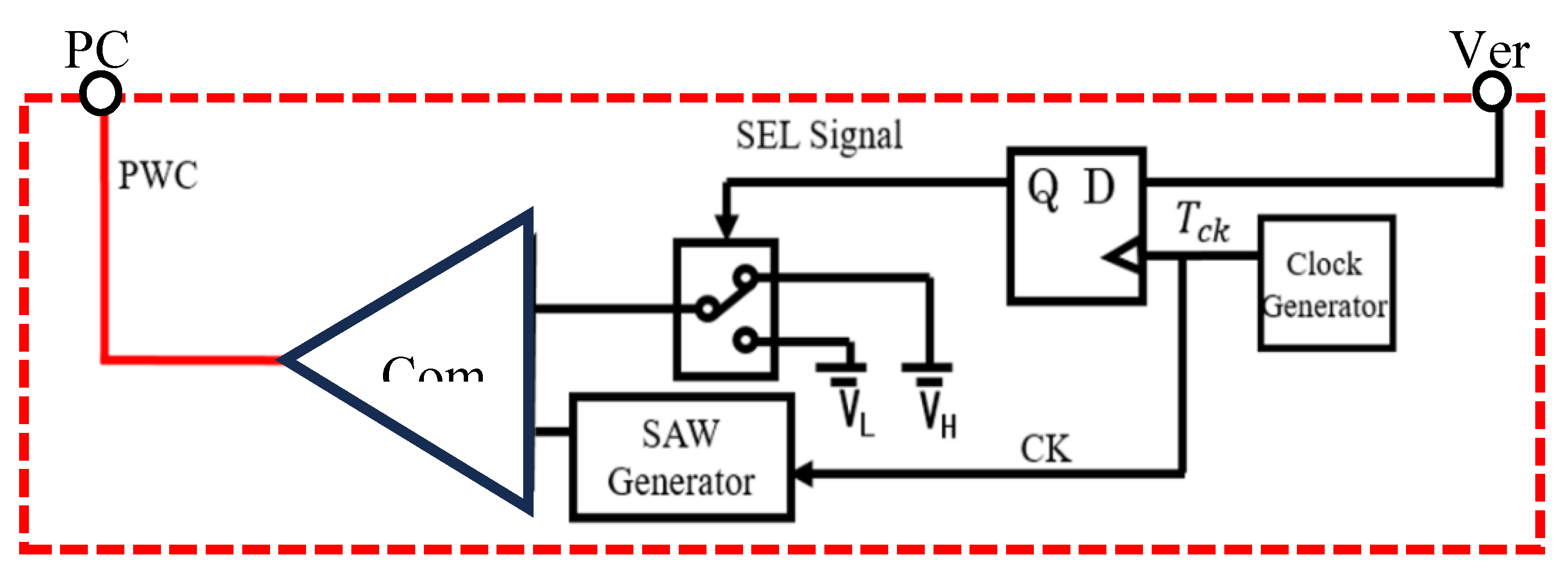

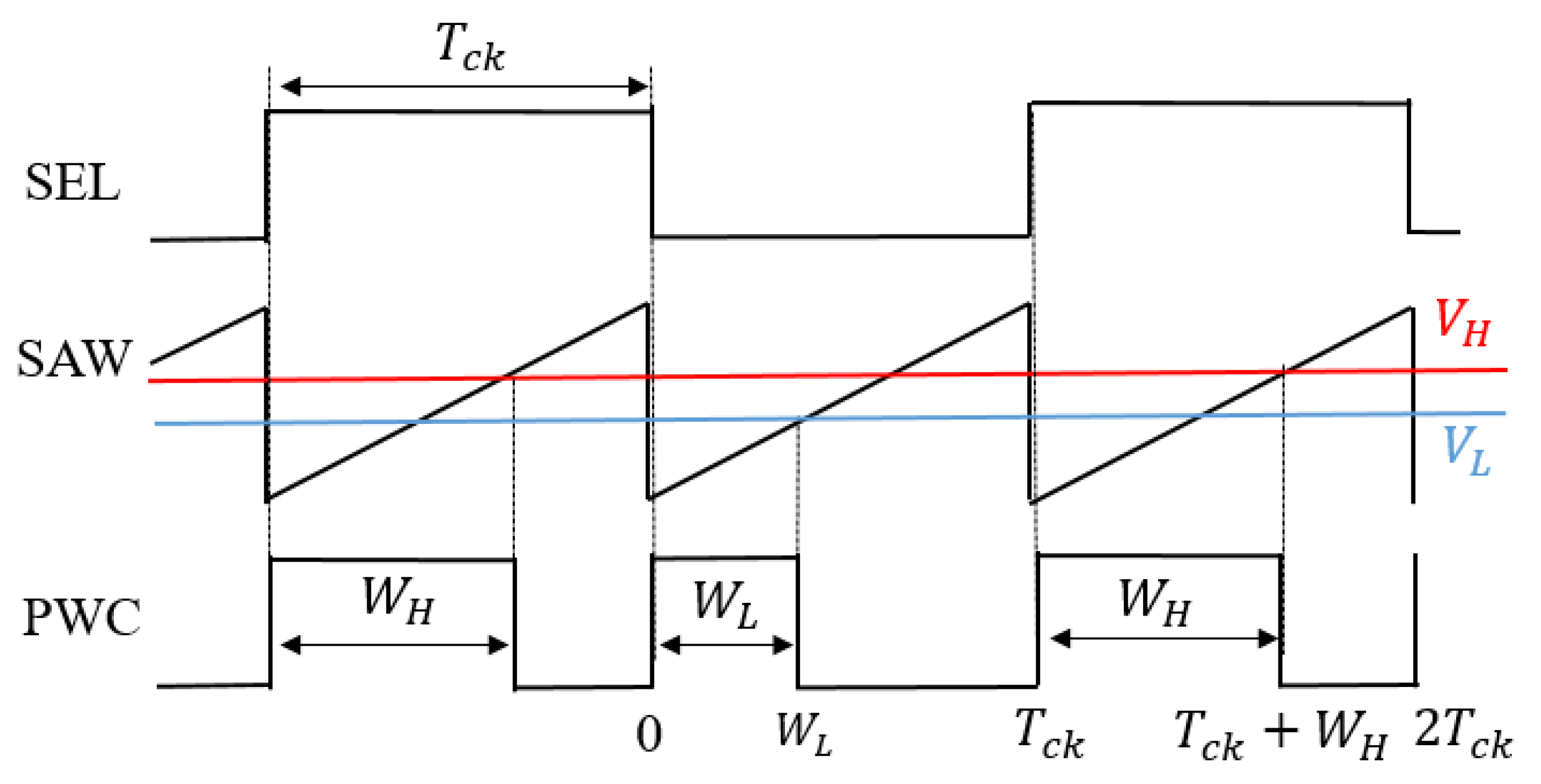

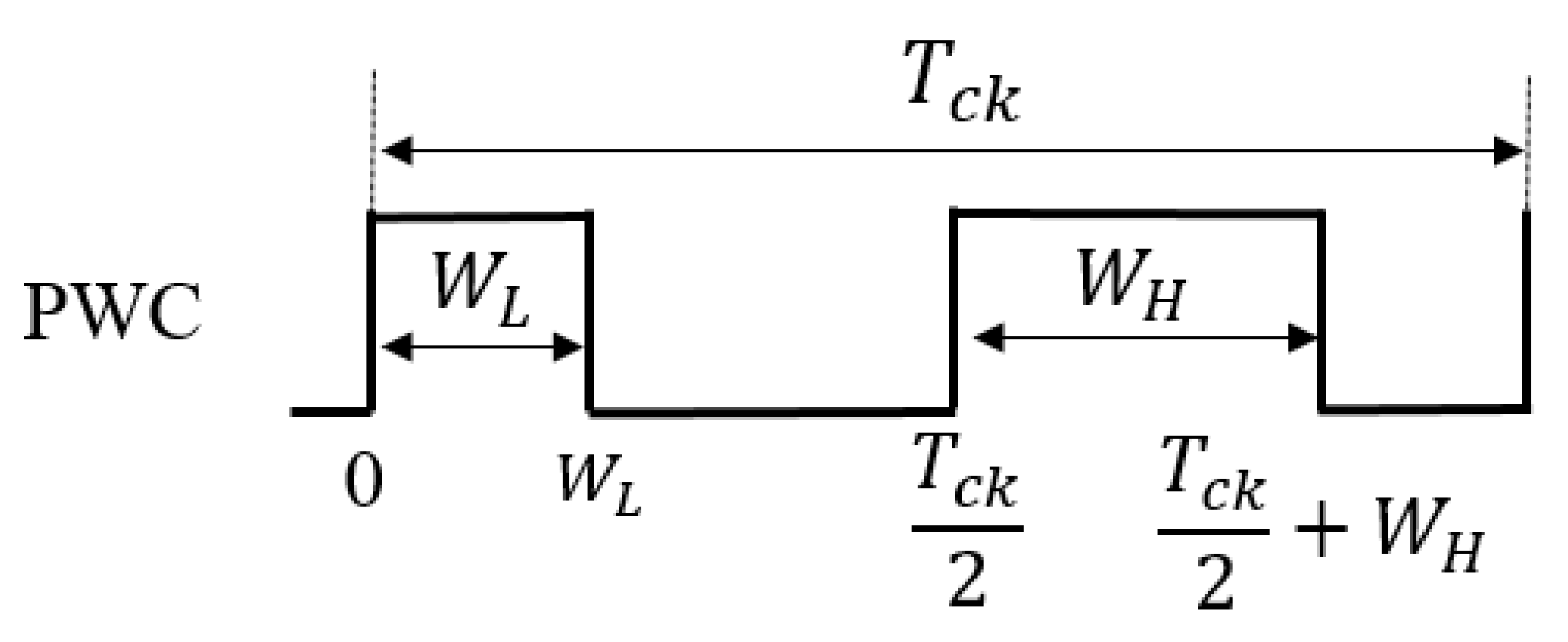

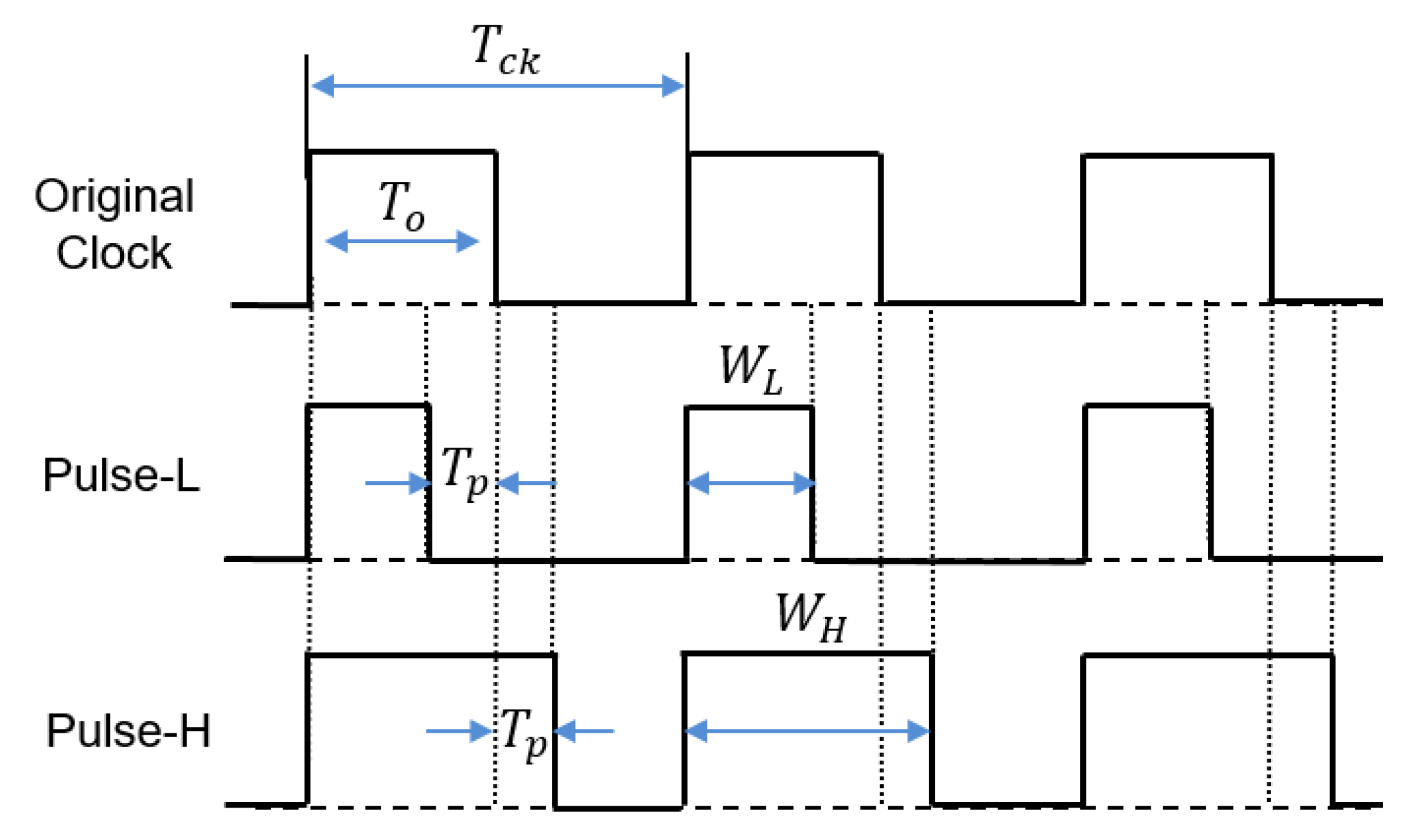

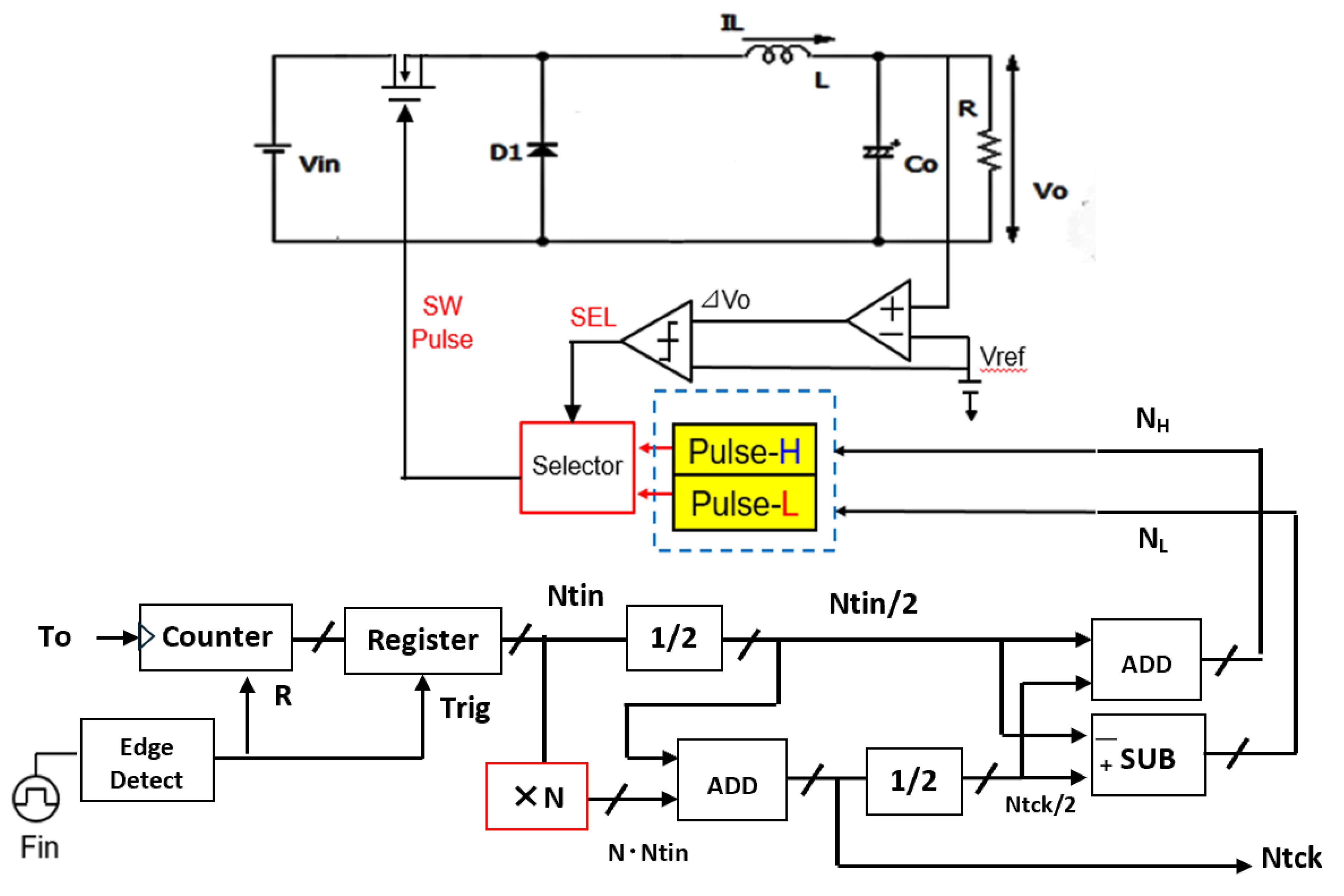

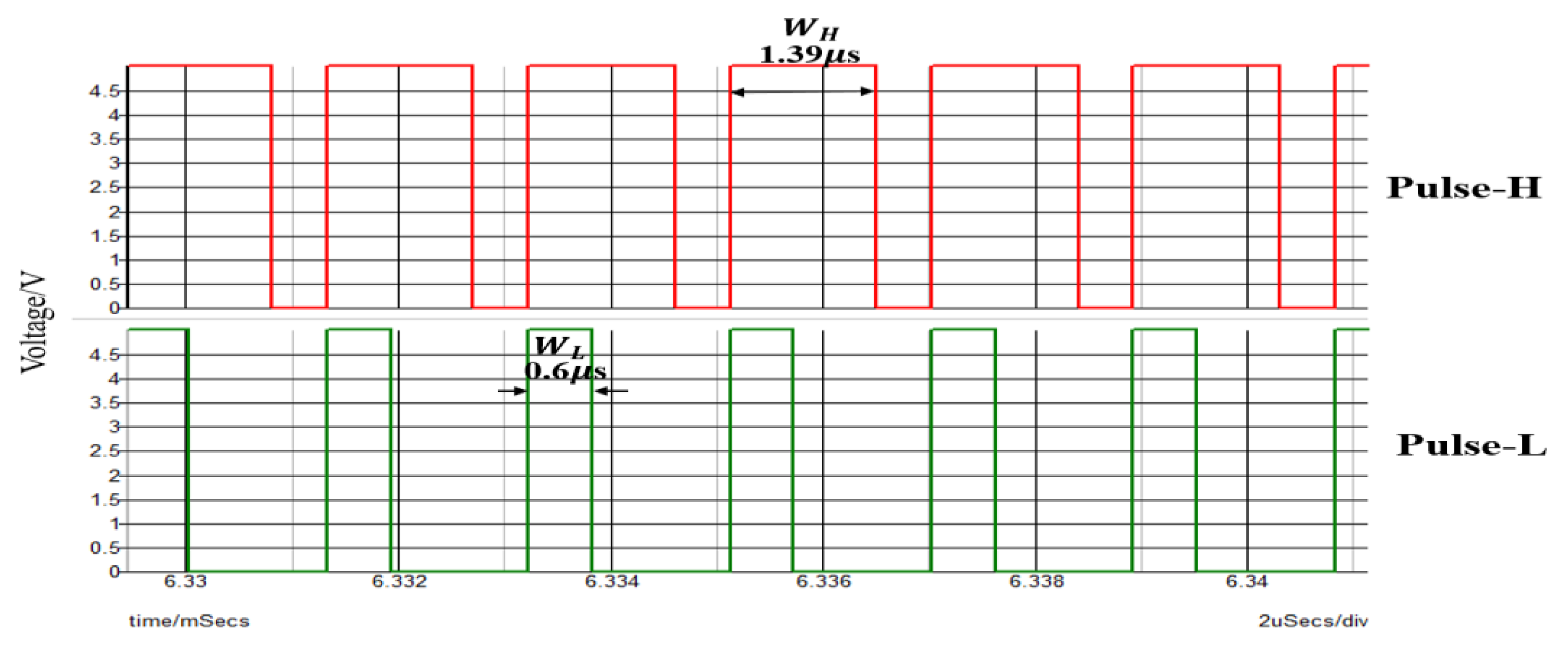

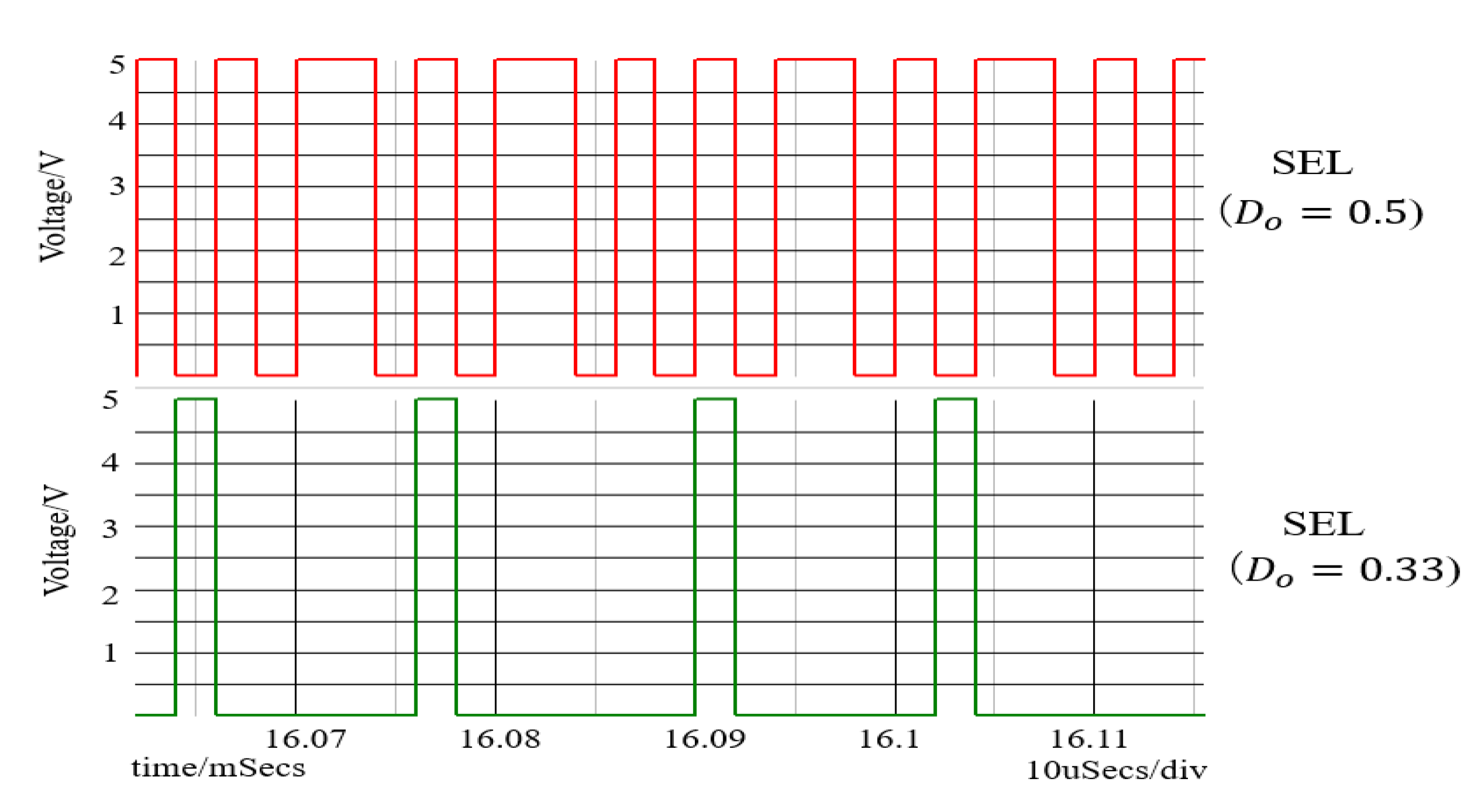

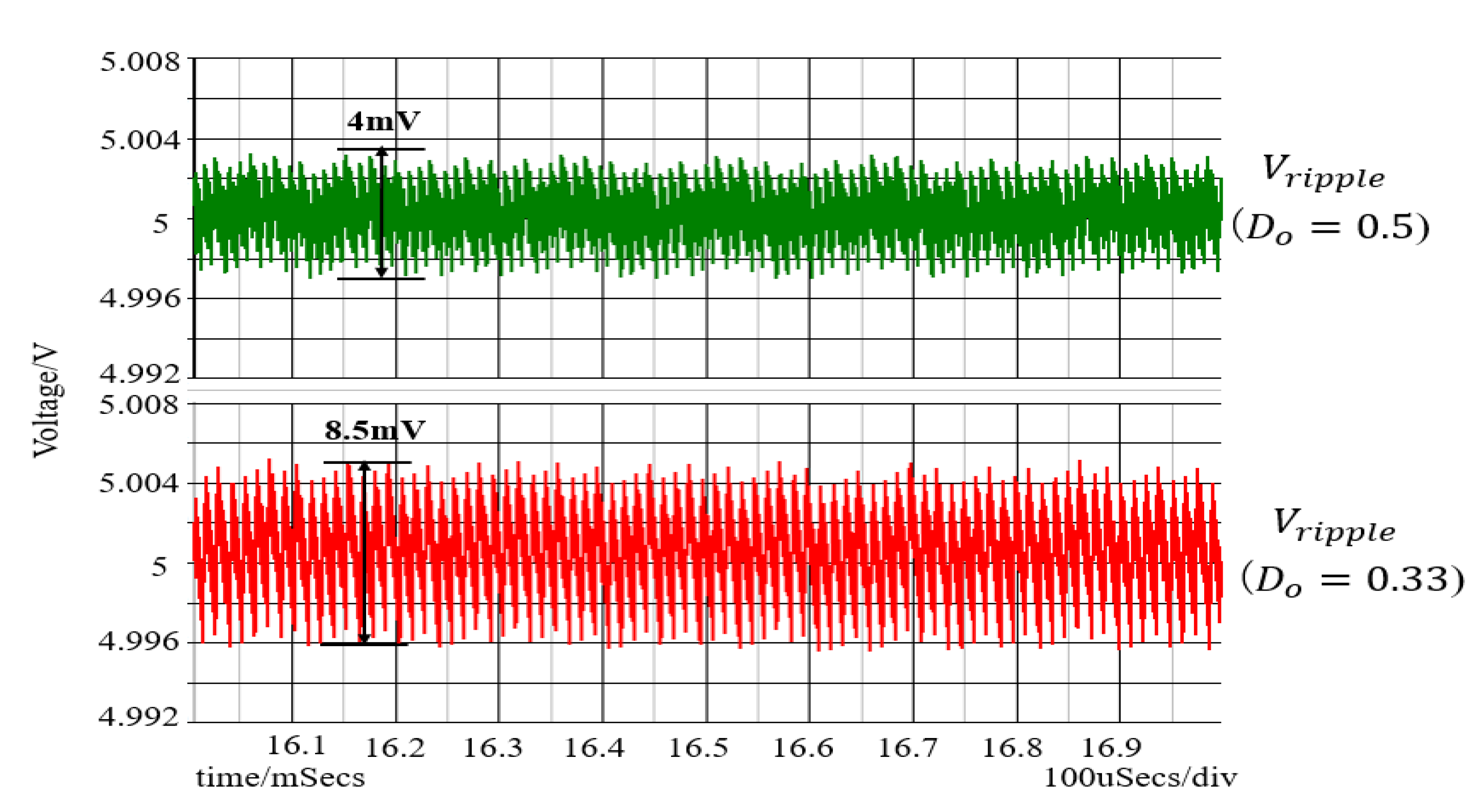

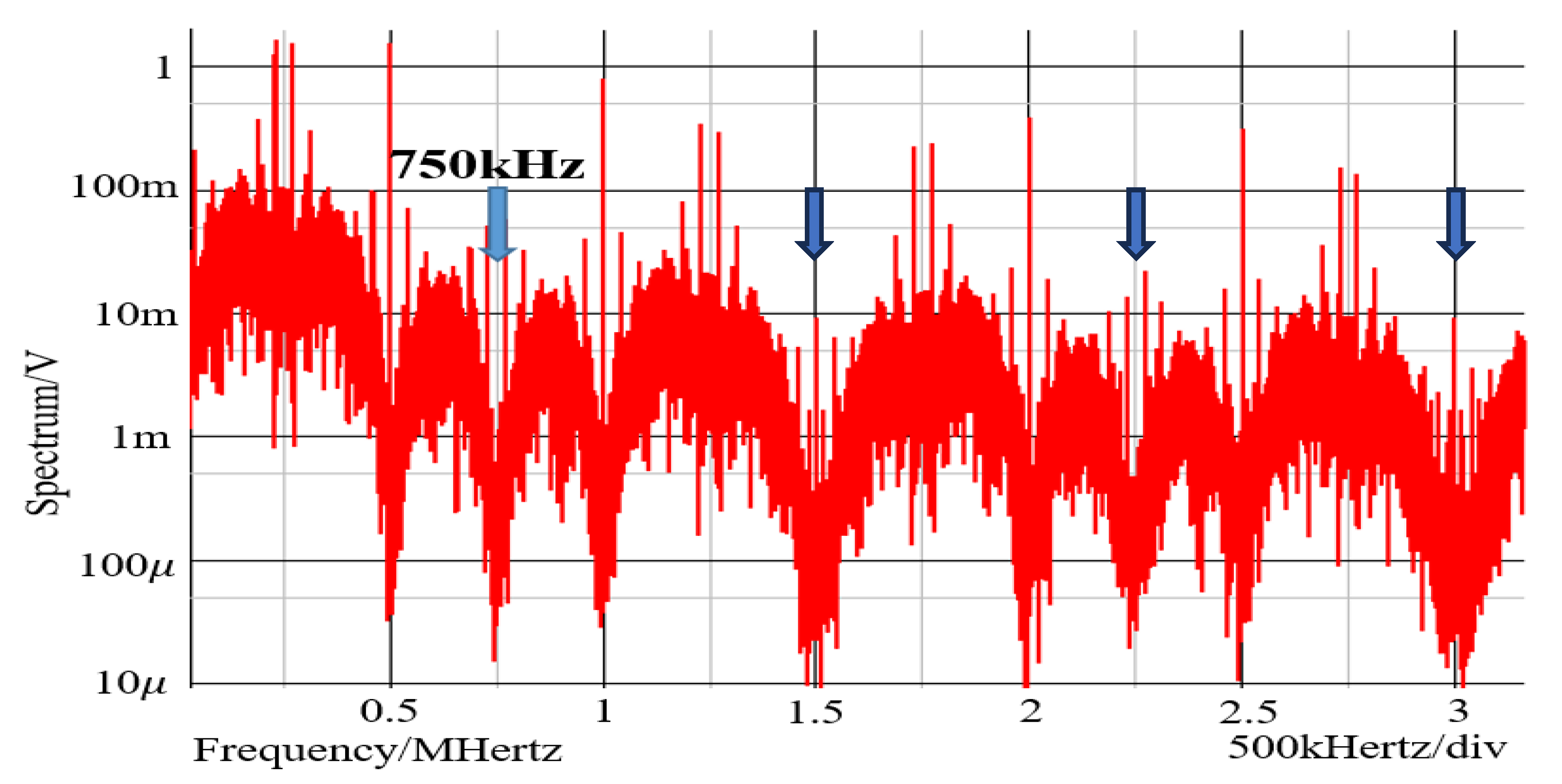

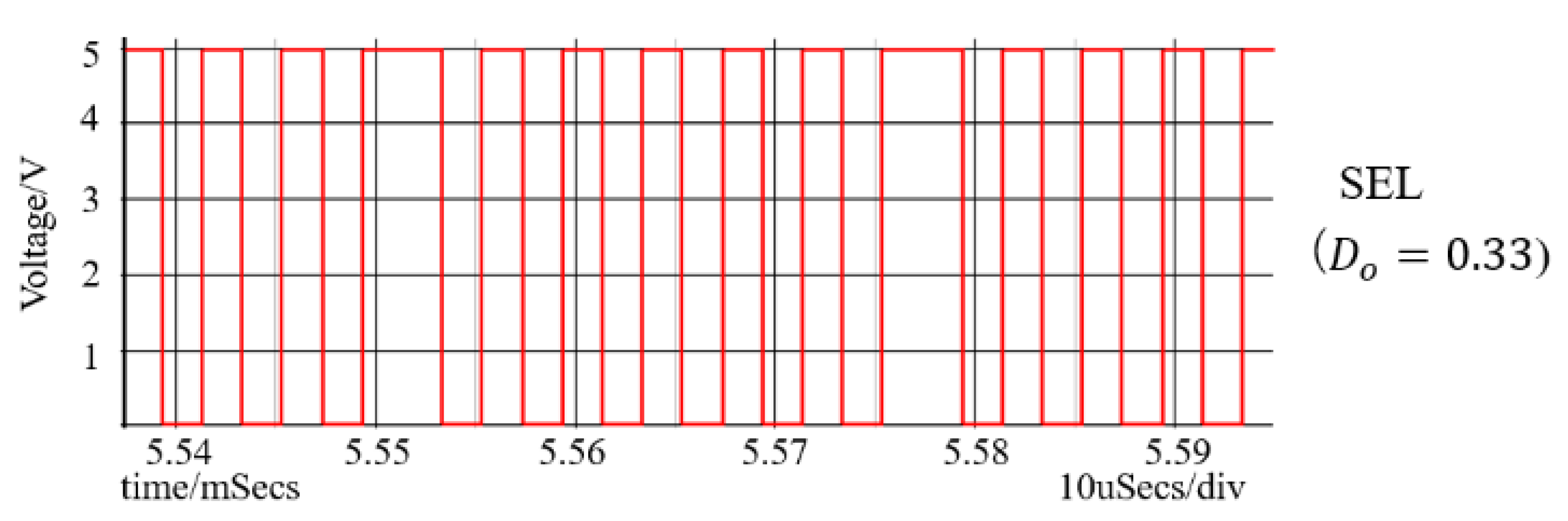

4.1. Pulse Width Coding (PWC) Control

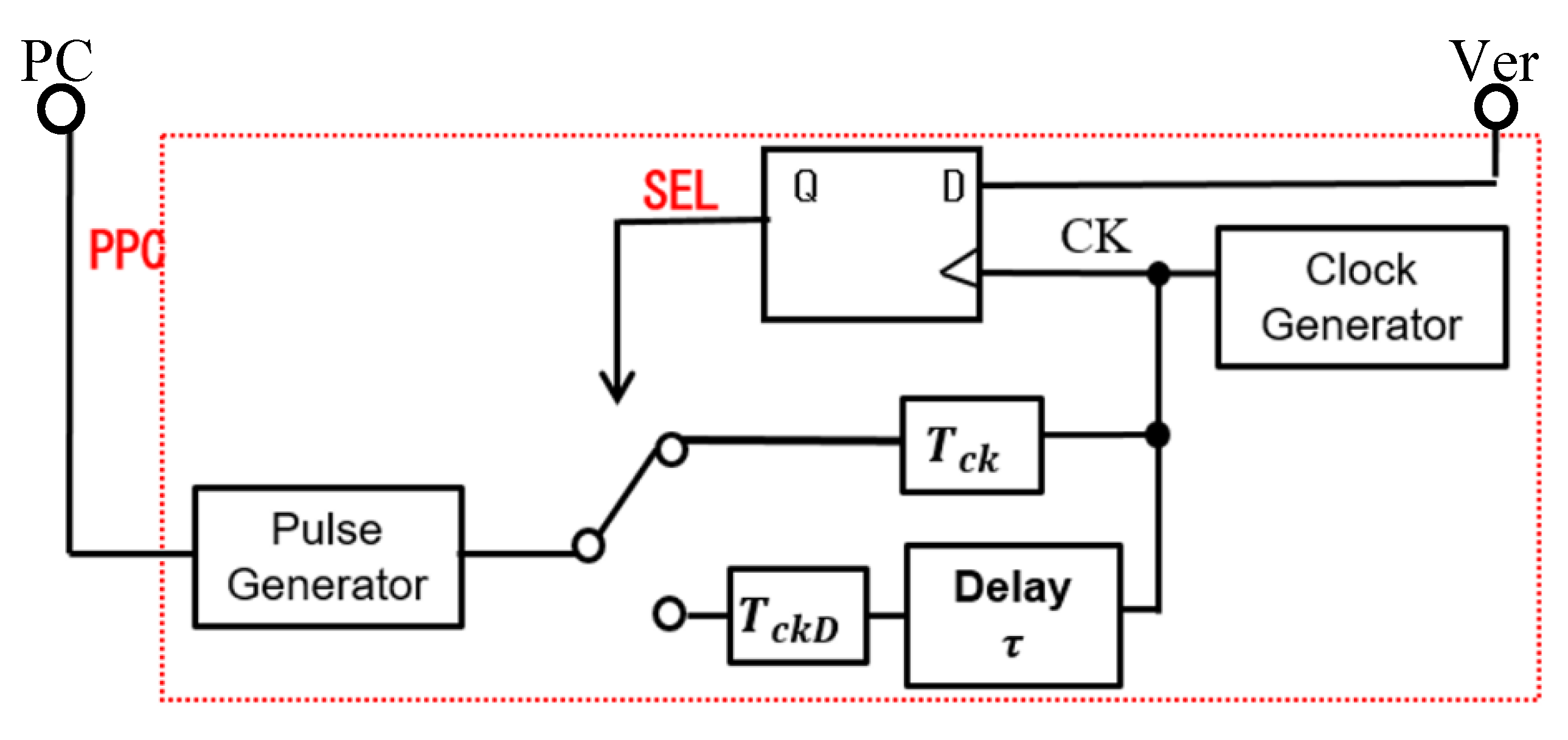

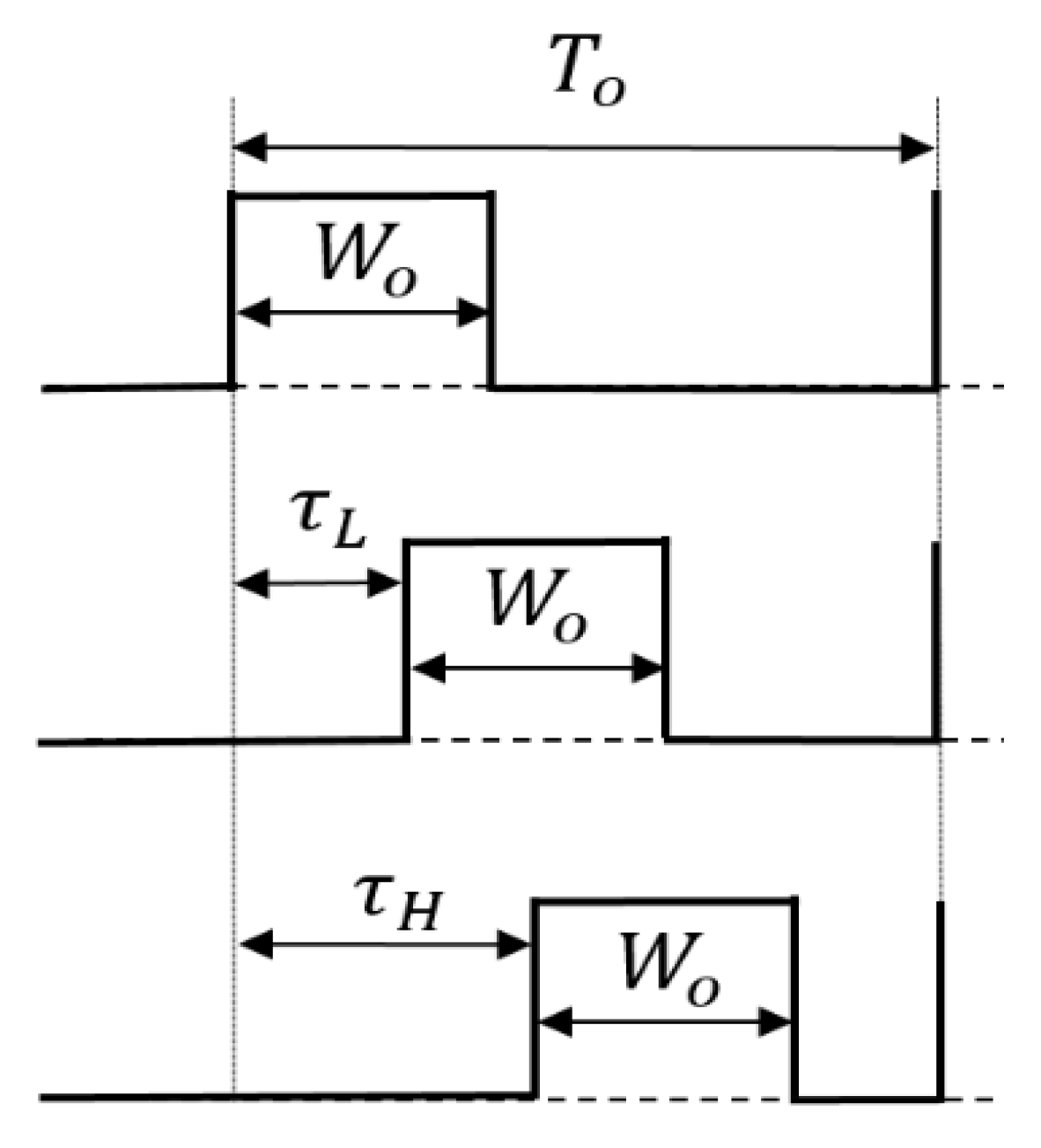

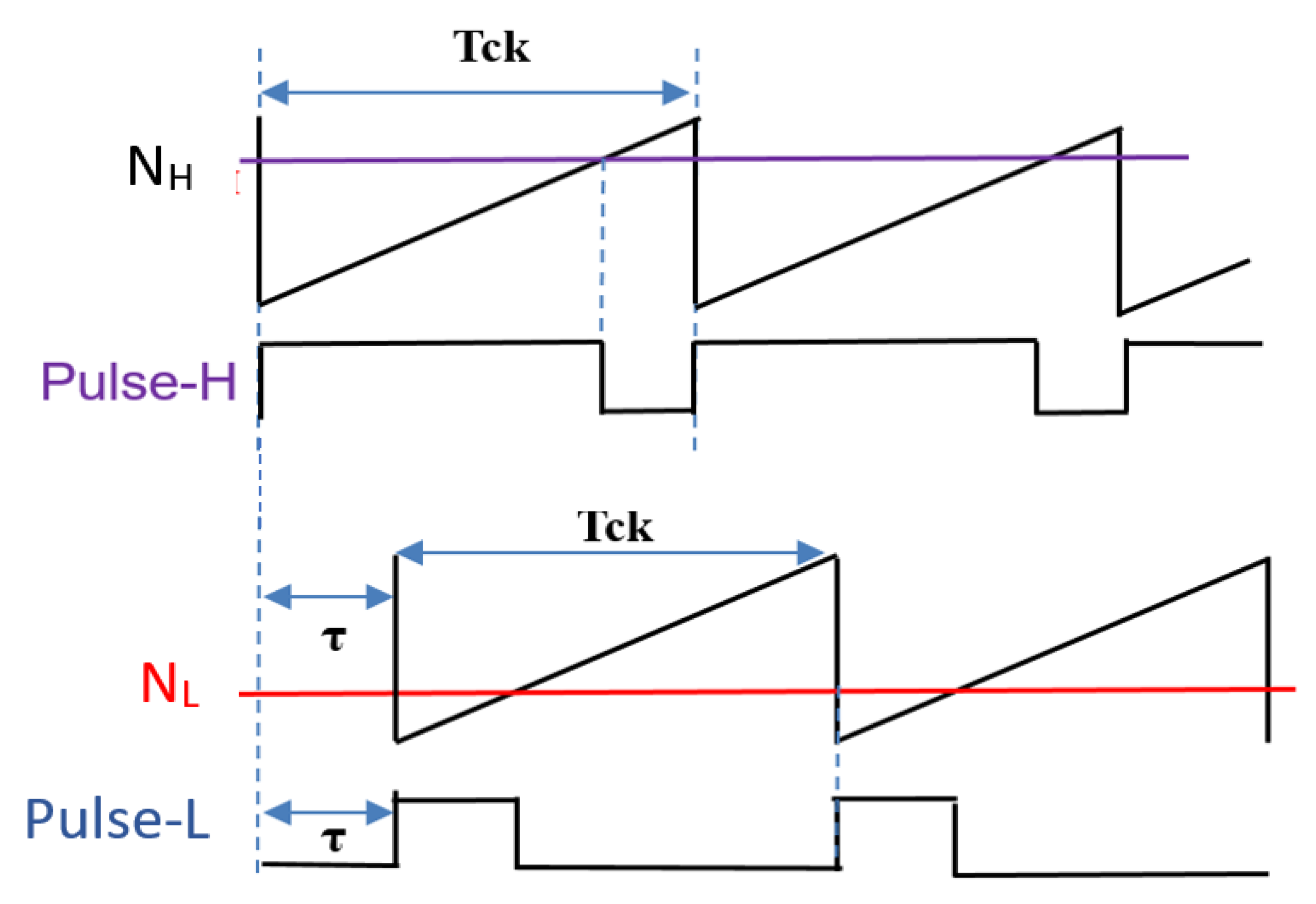

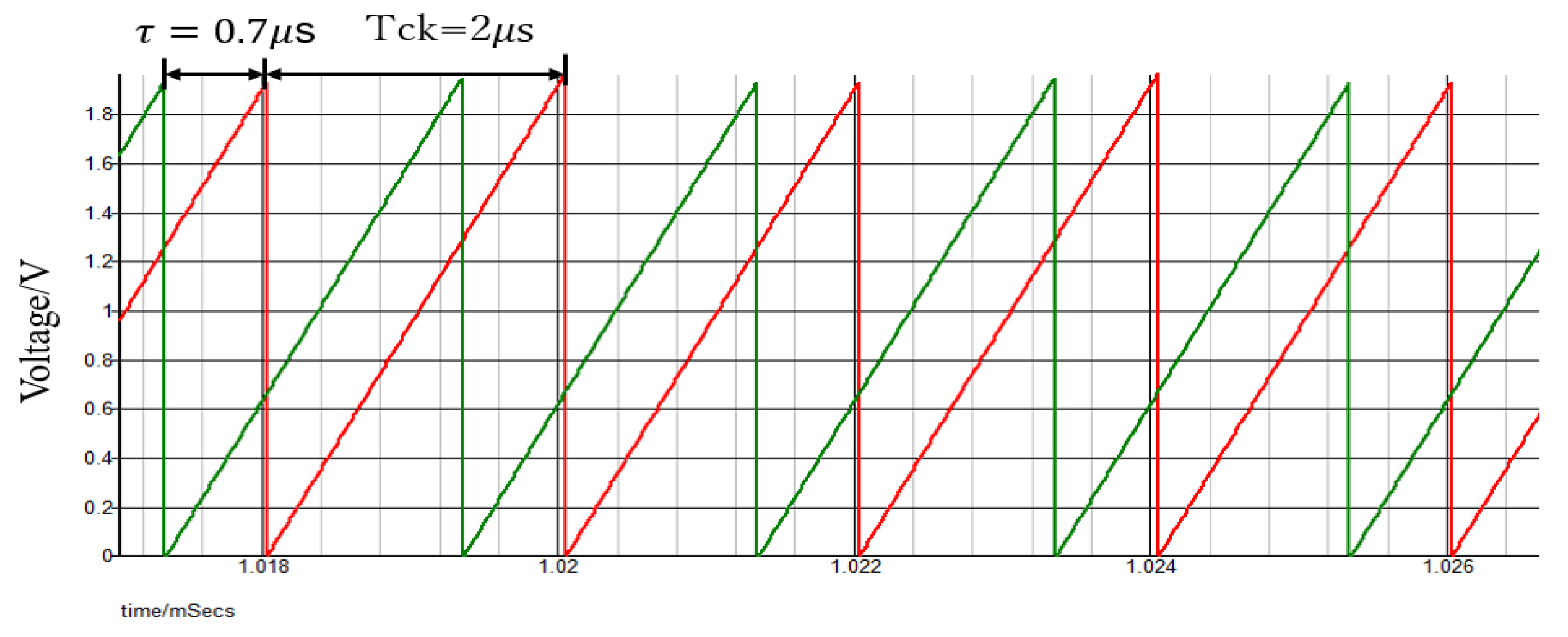

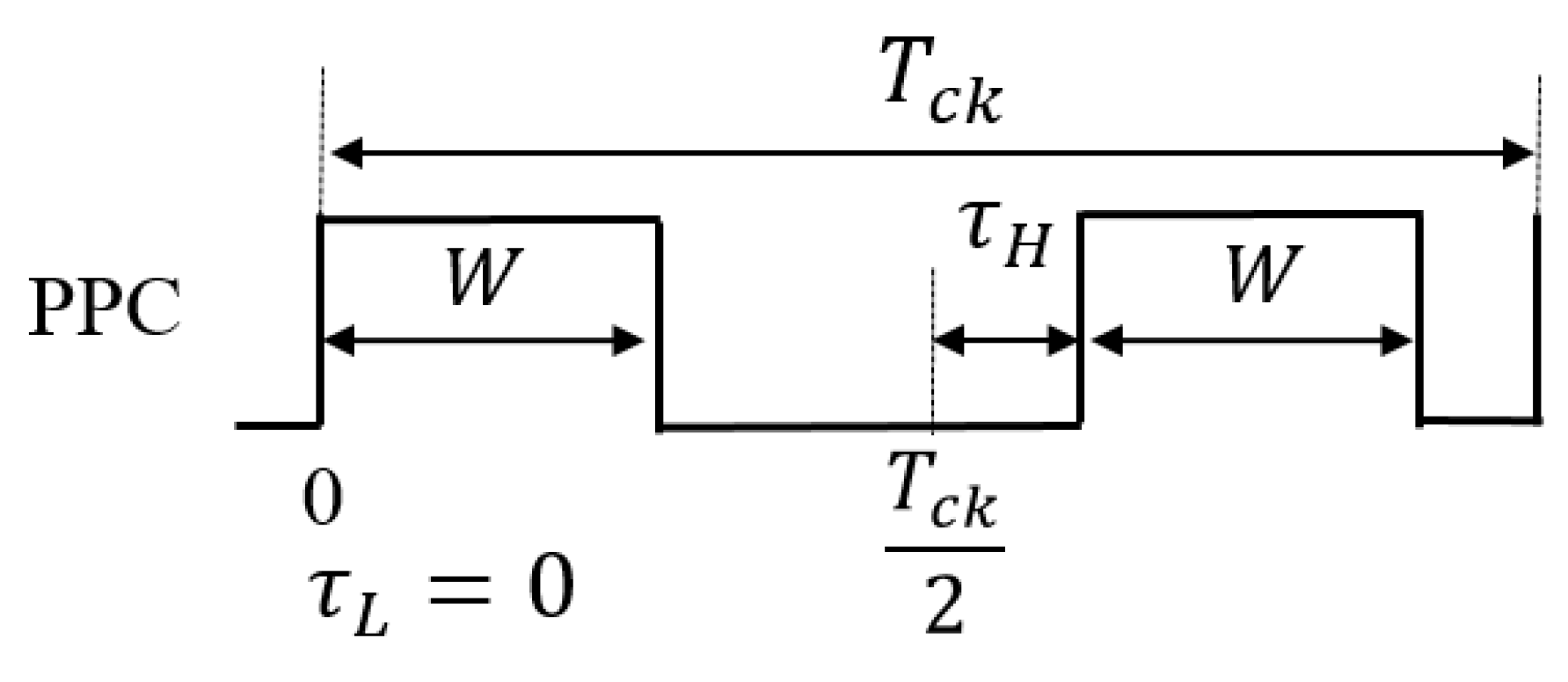

4.2. Pulse Phase Coding (PPC) Control

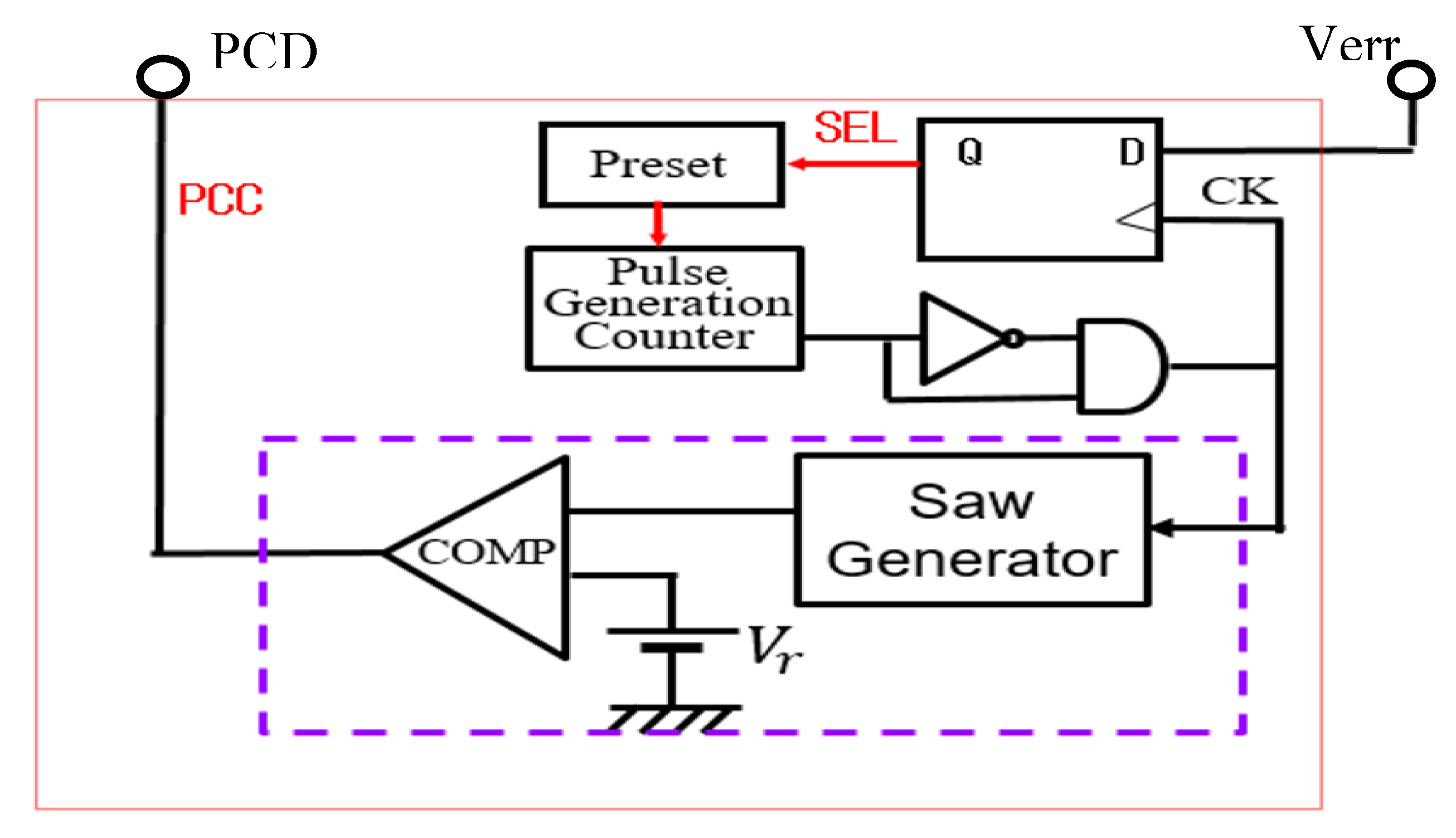

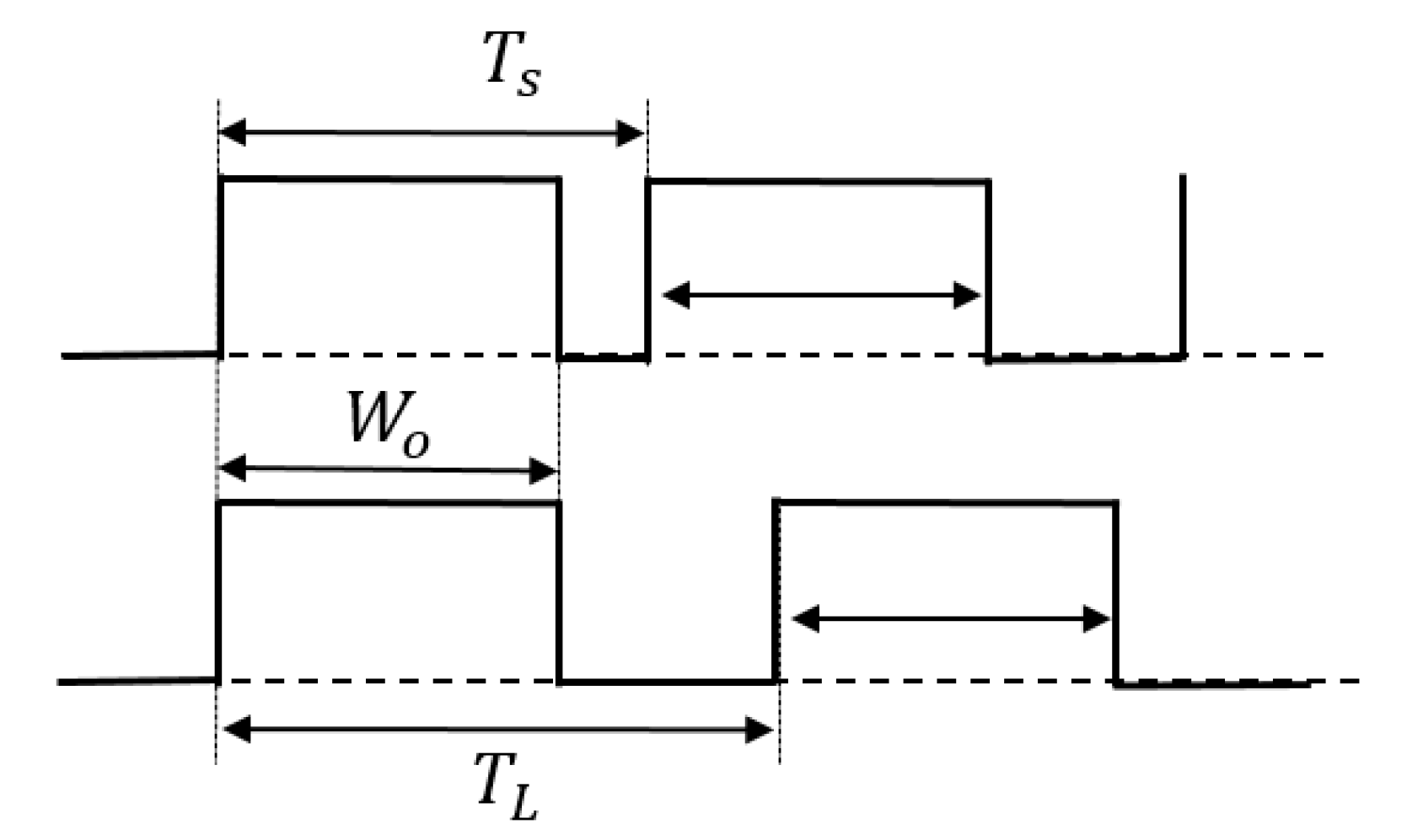

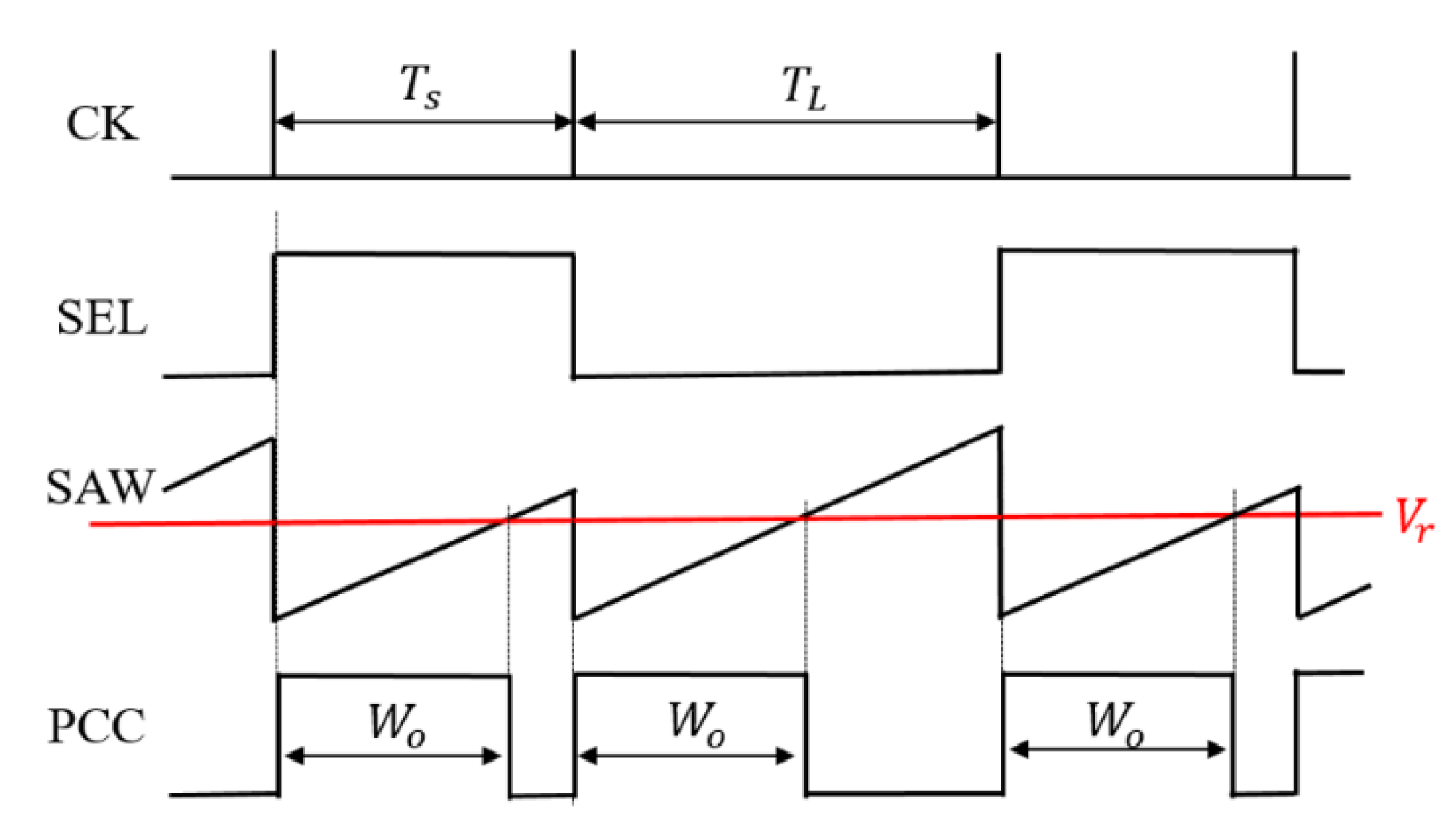

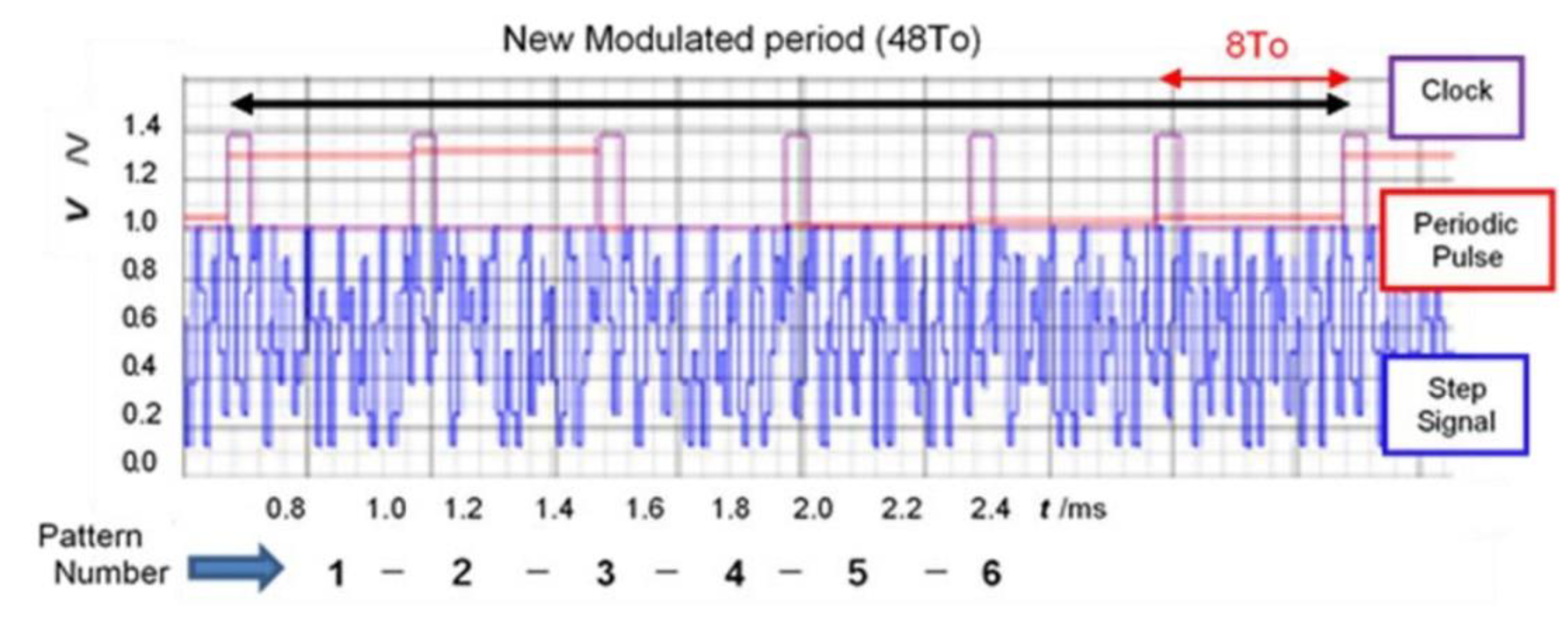

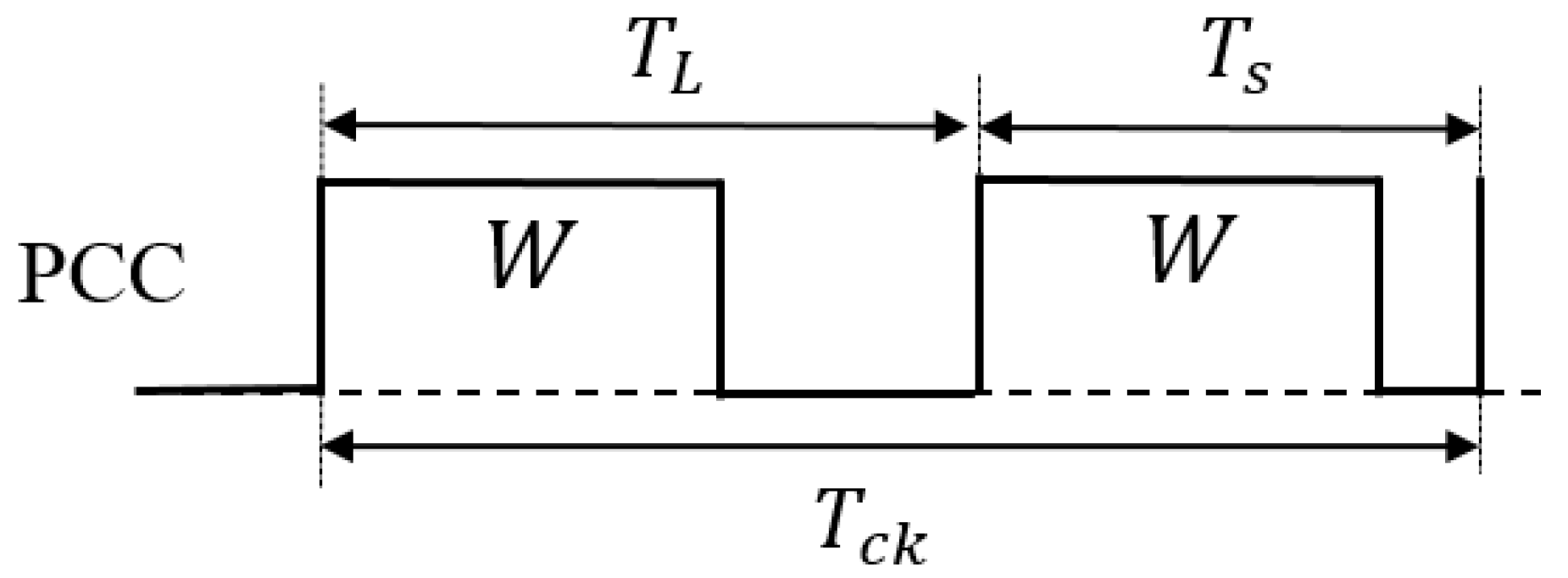

4.3. Pulse Cycle Coding (PCC) Control

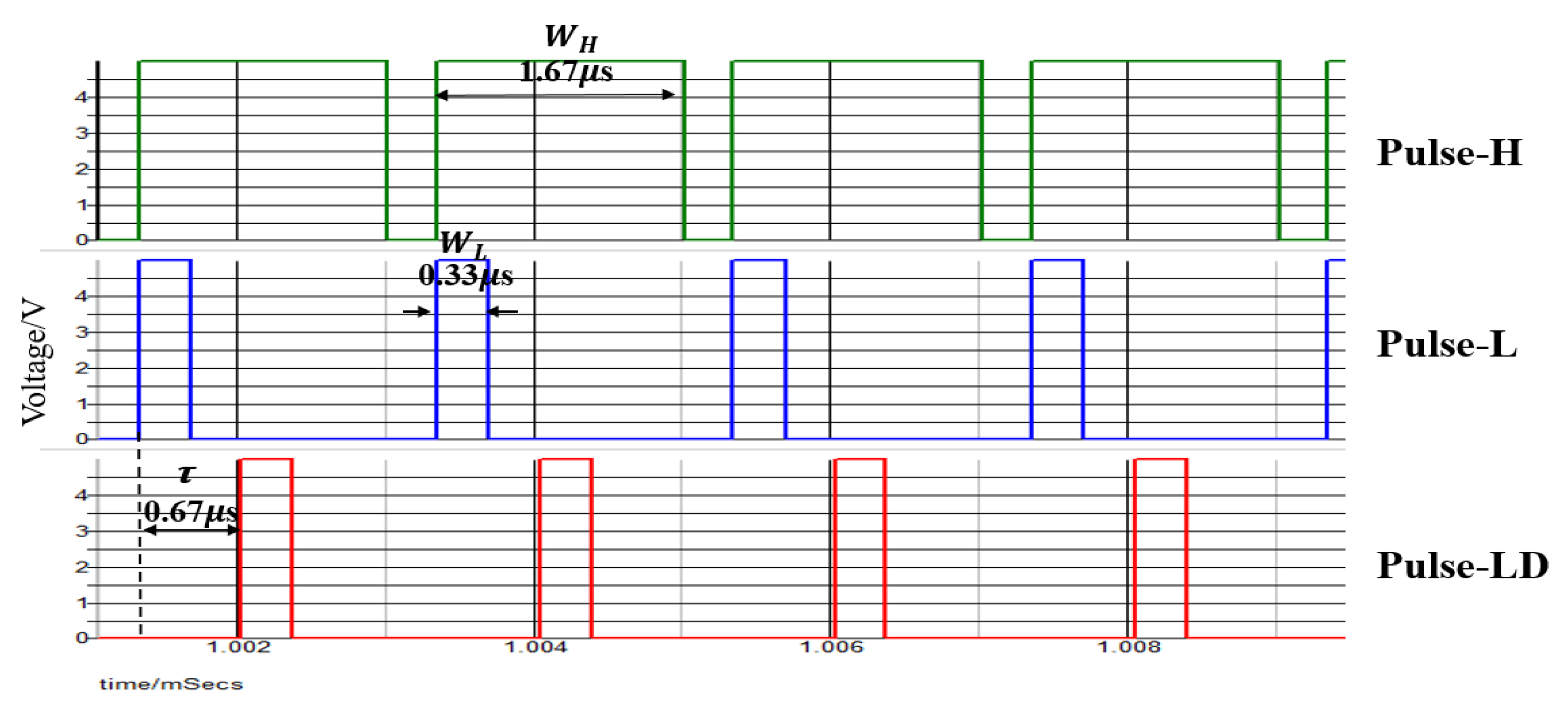

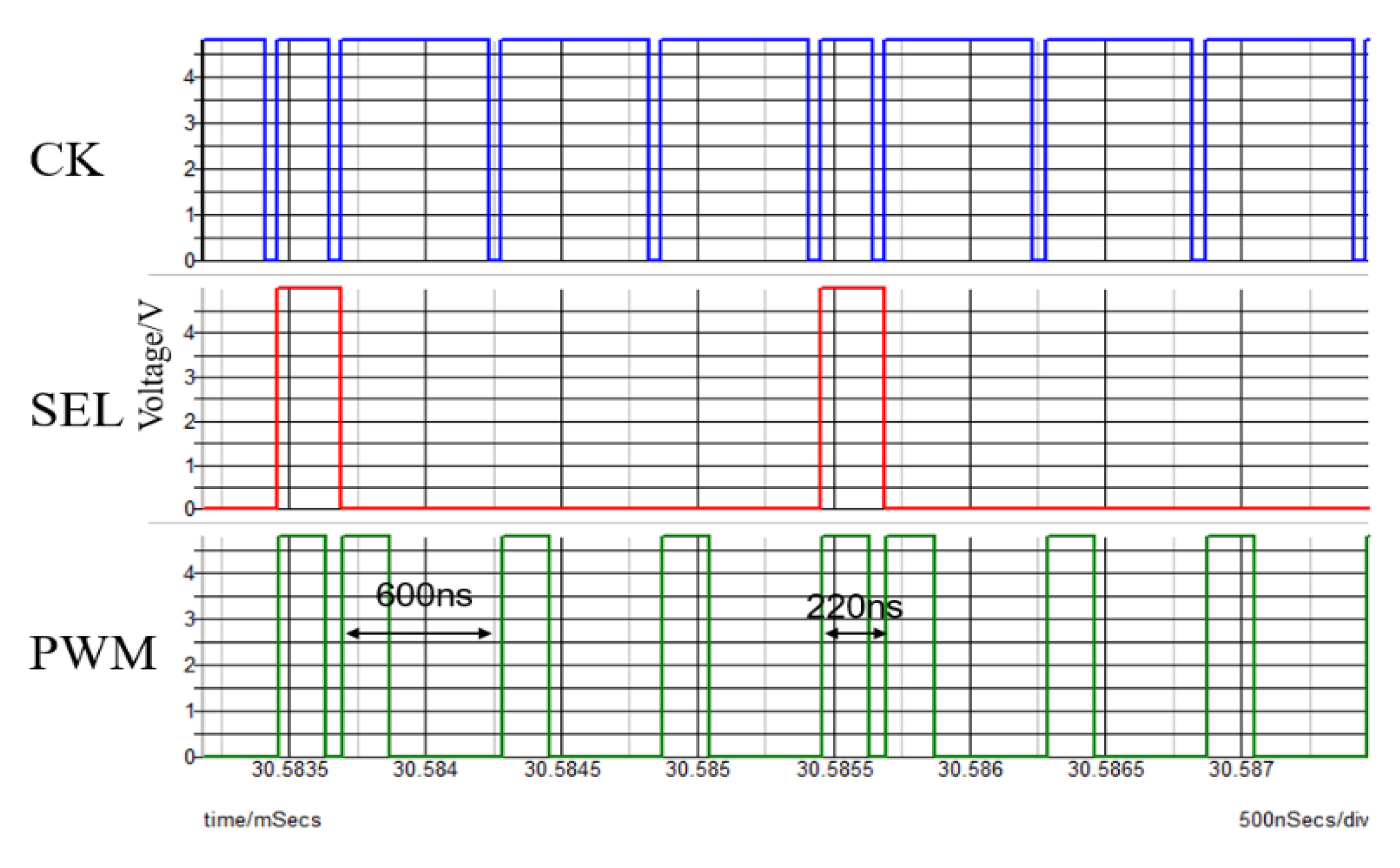

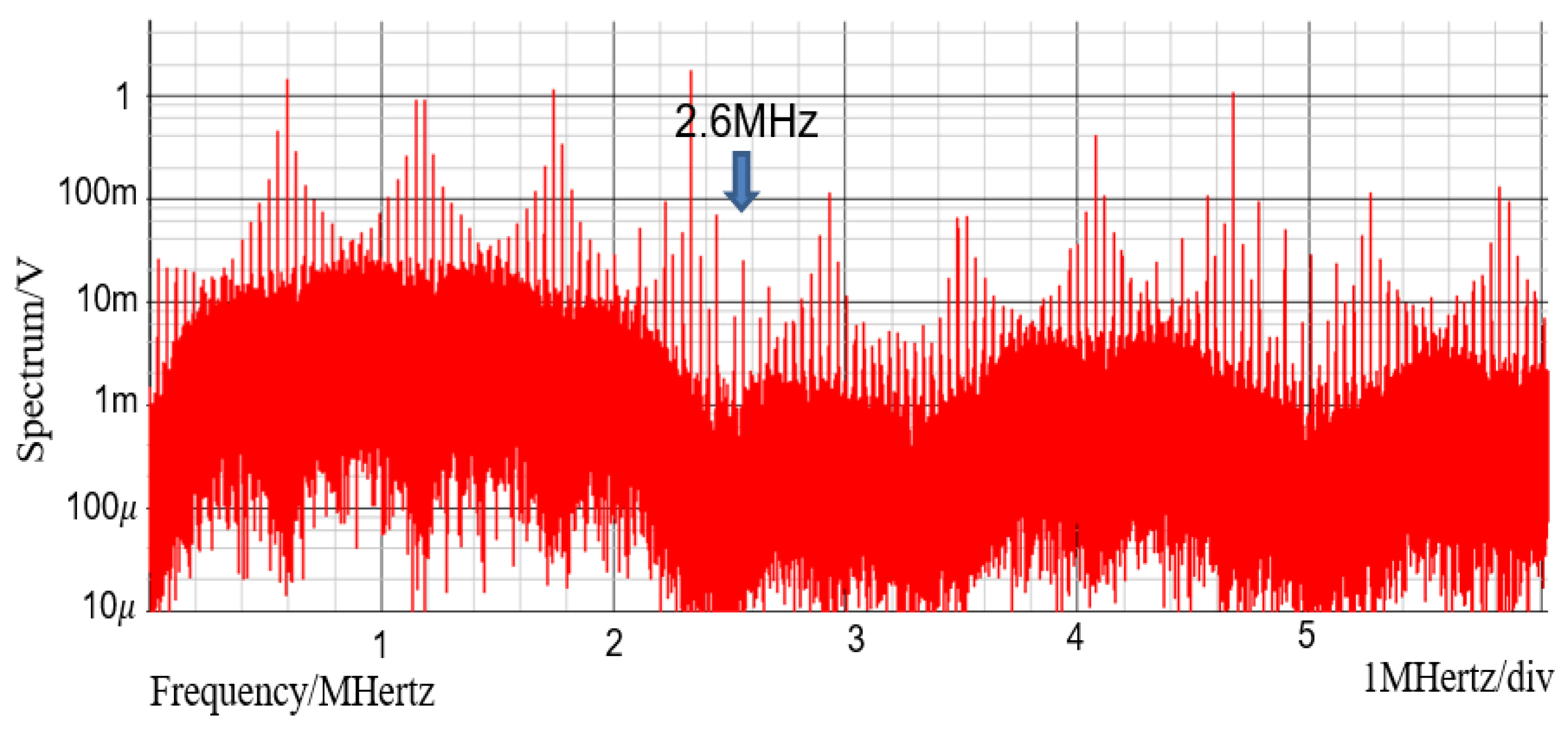

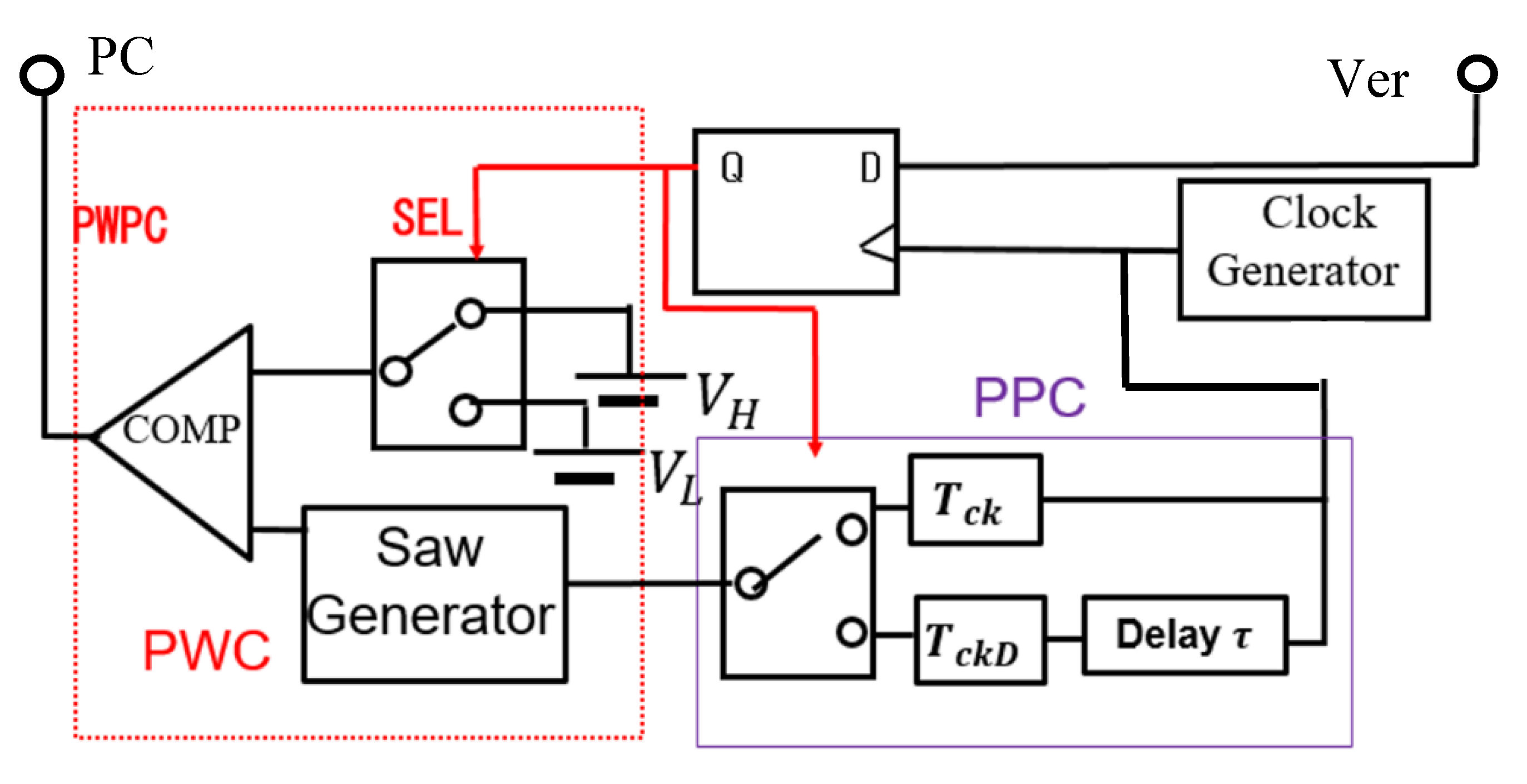

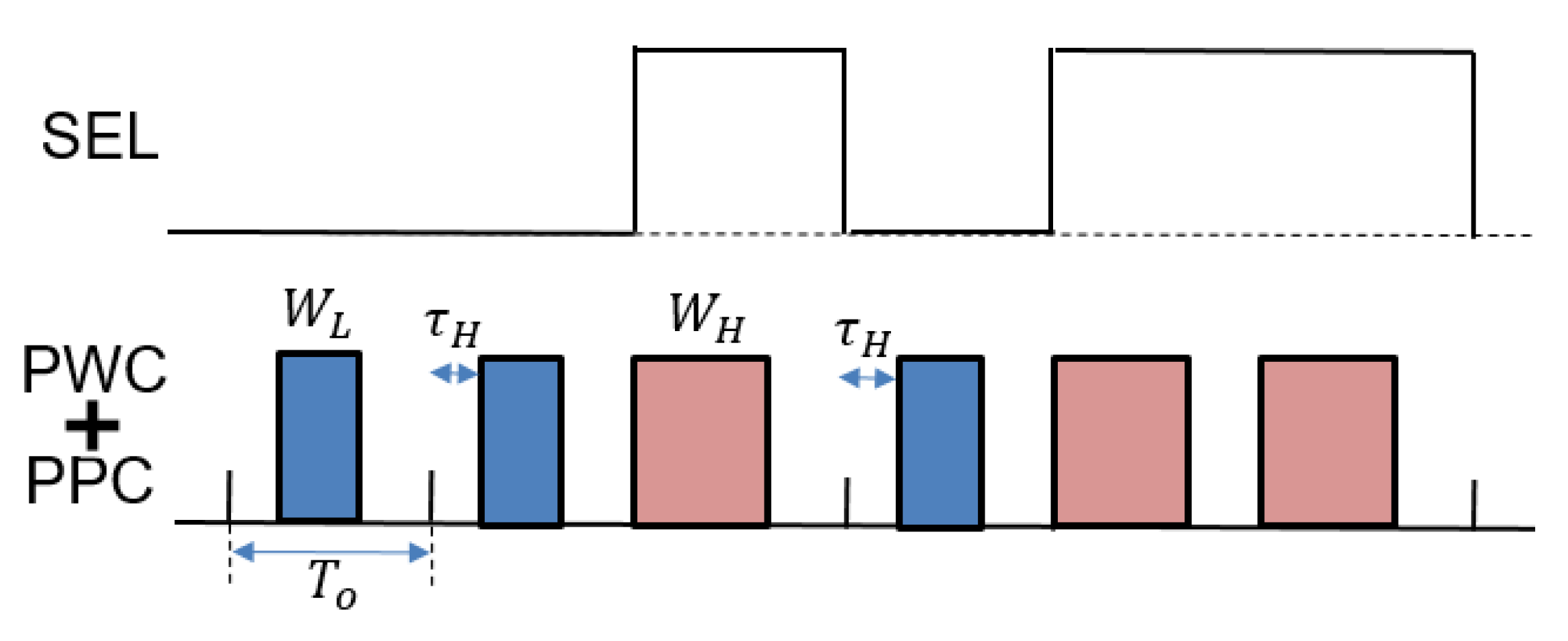

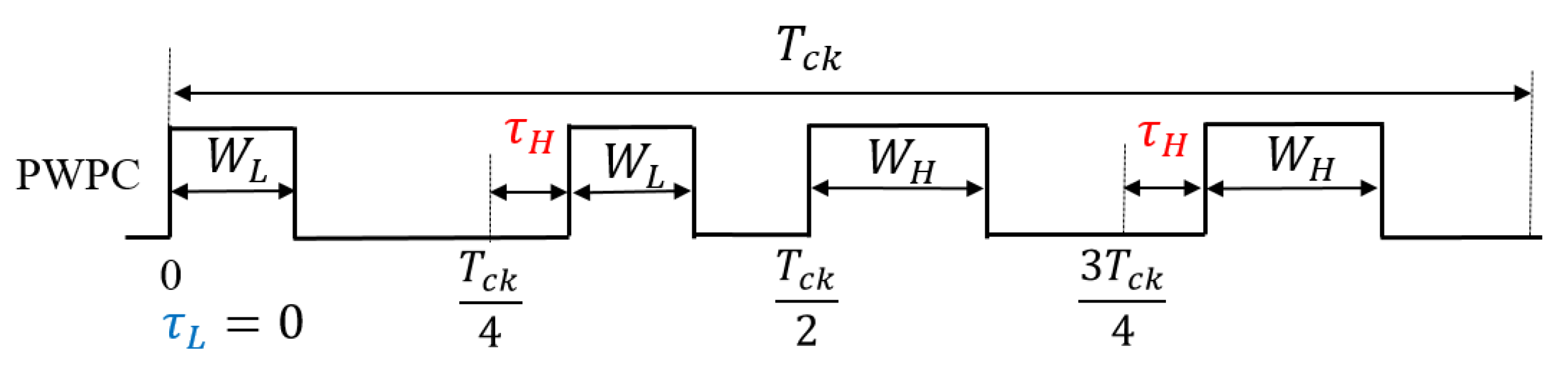

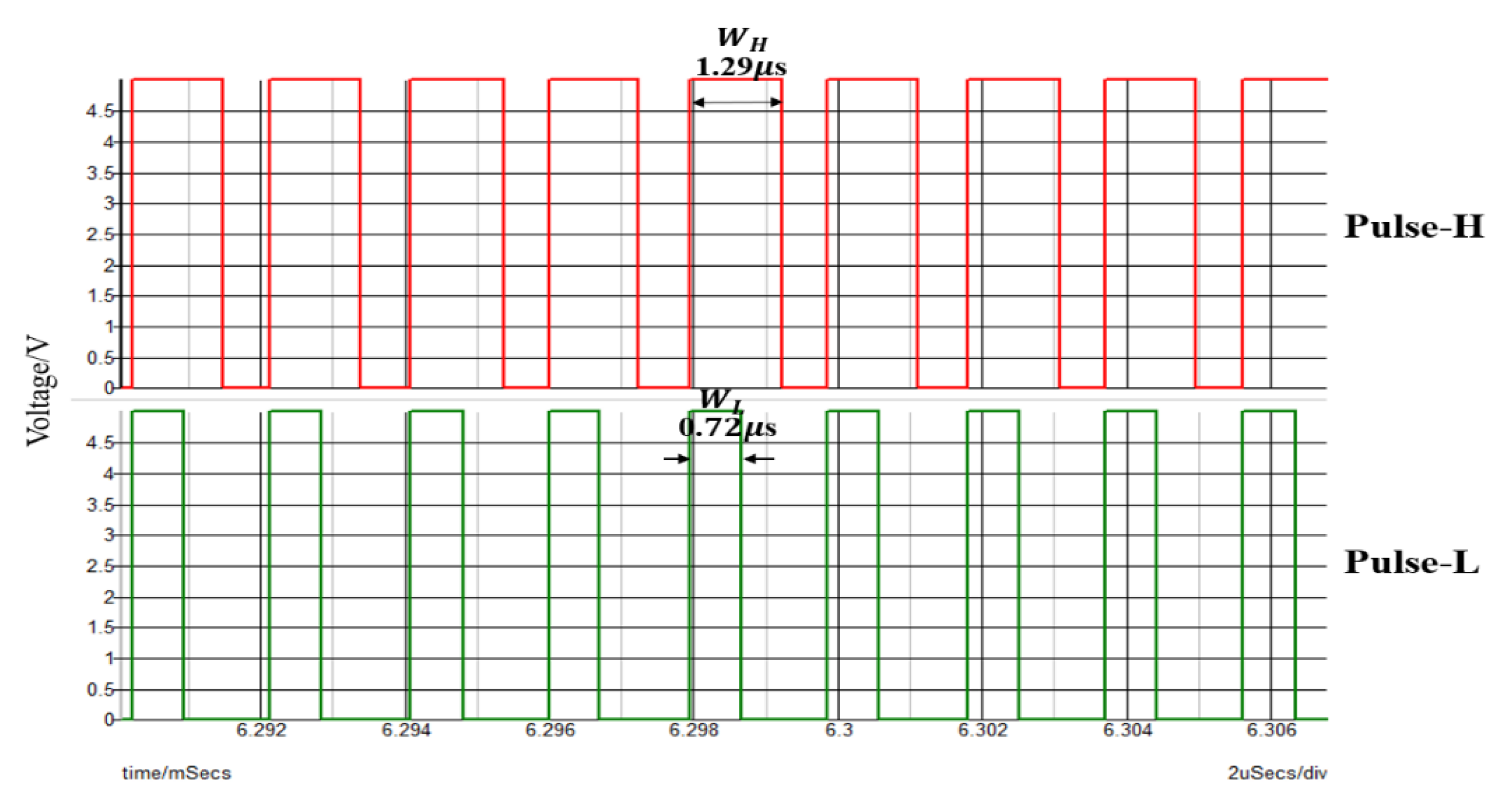

4.4. Pulse Width and Phase Coding (PWPC) Control

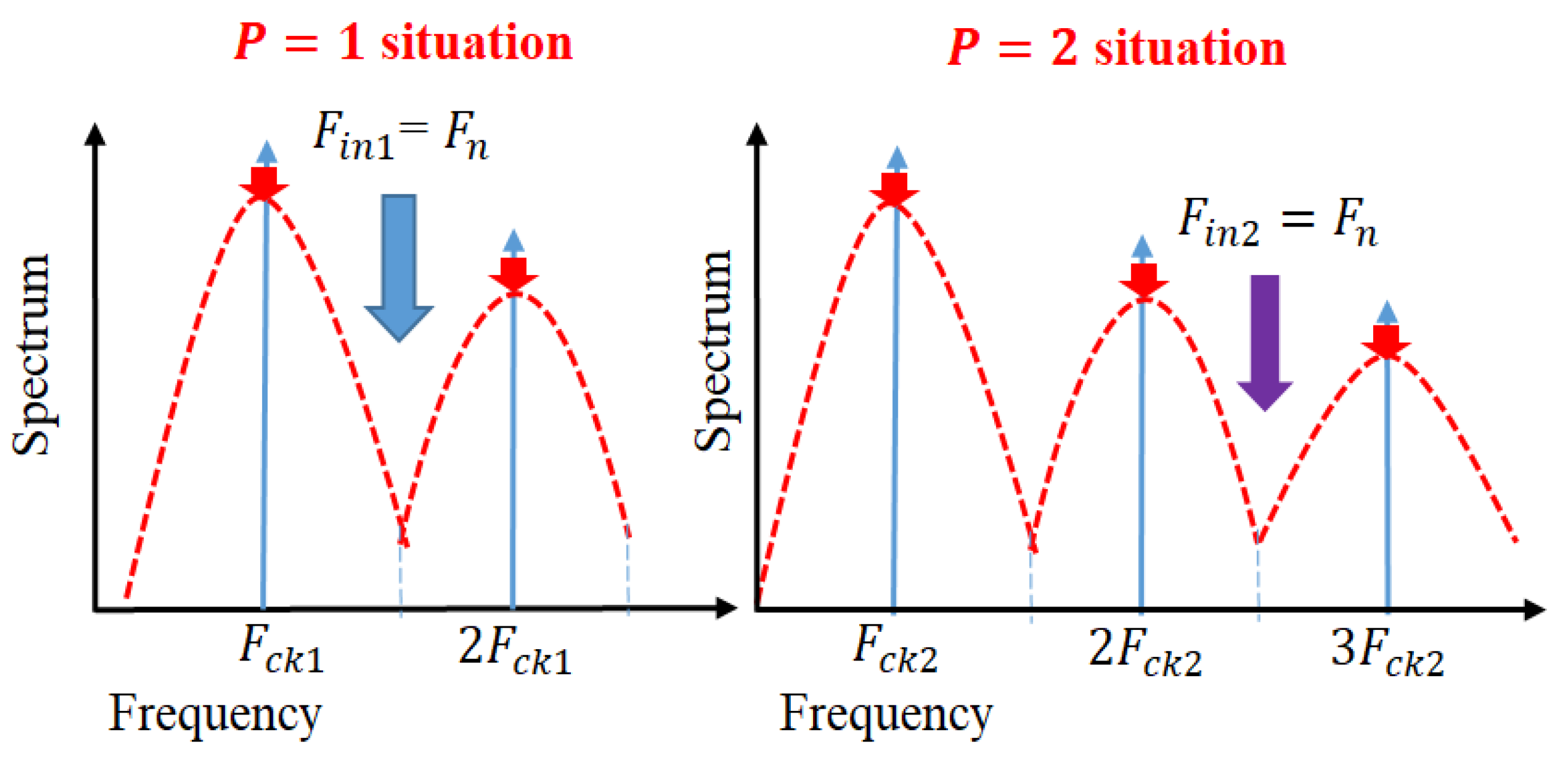

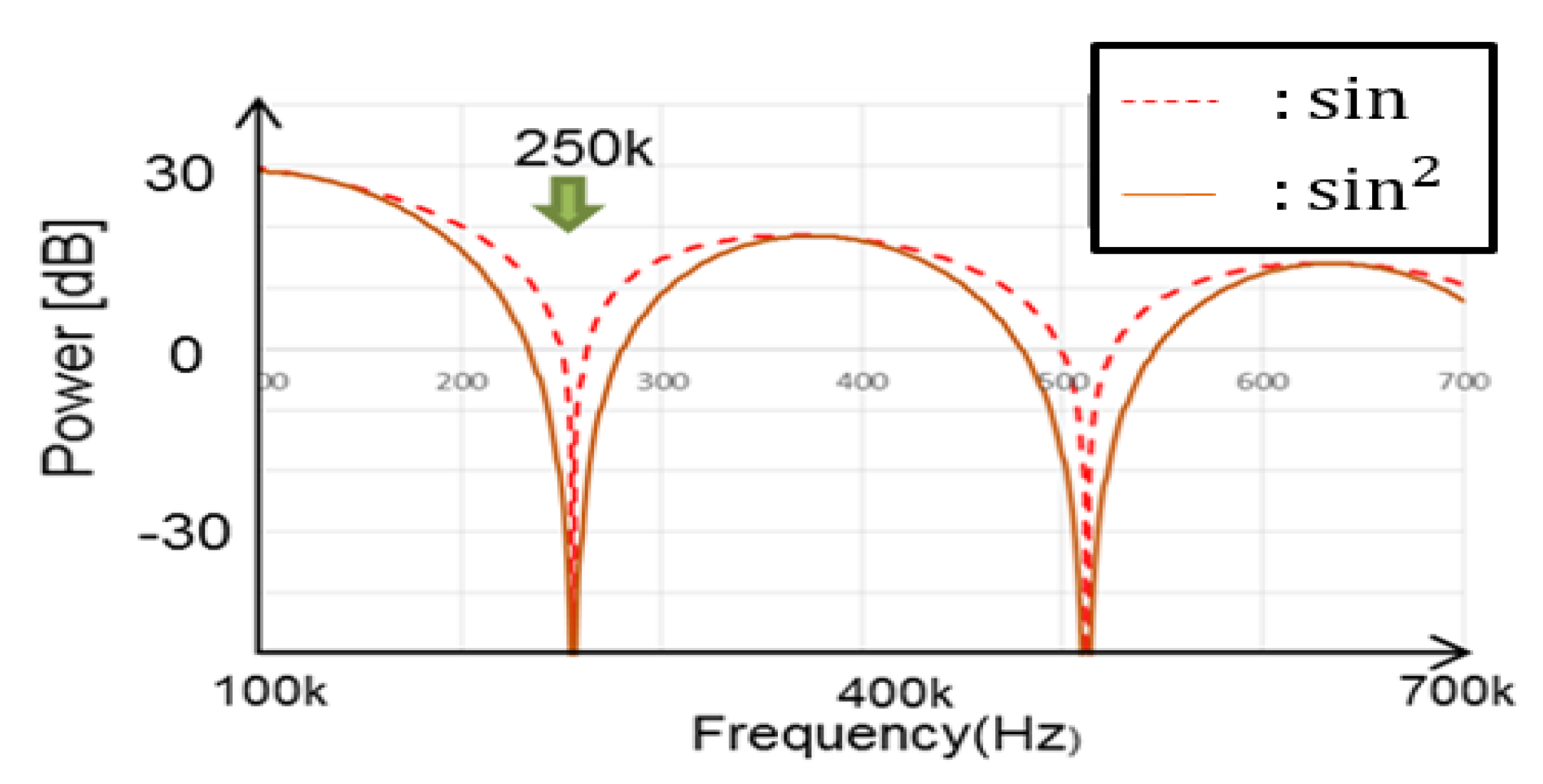

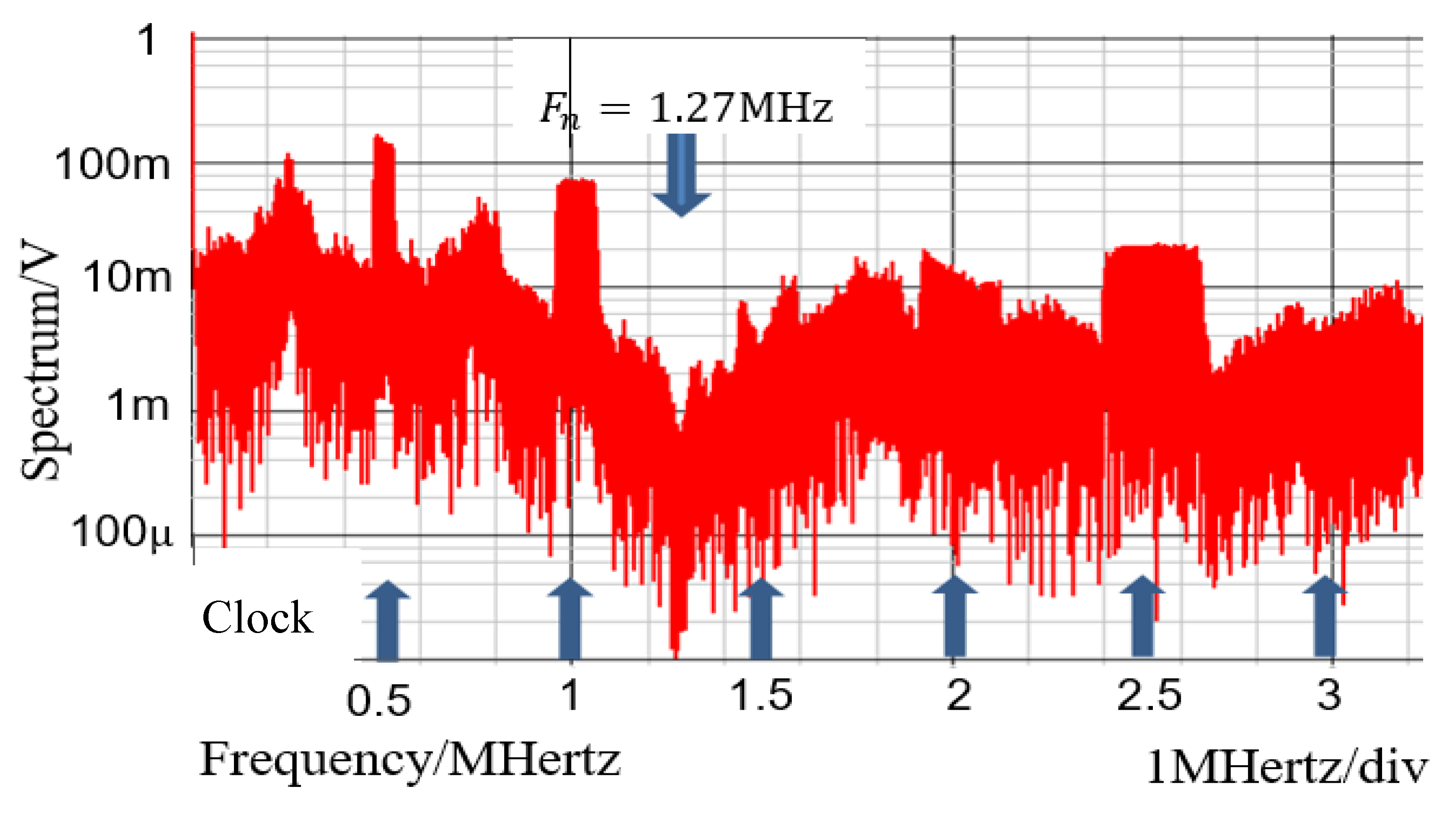

4.5. Derivation of Notch Frequency Using Fourier Transform

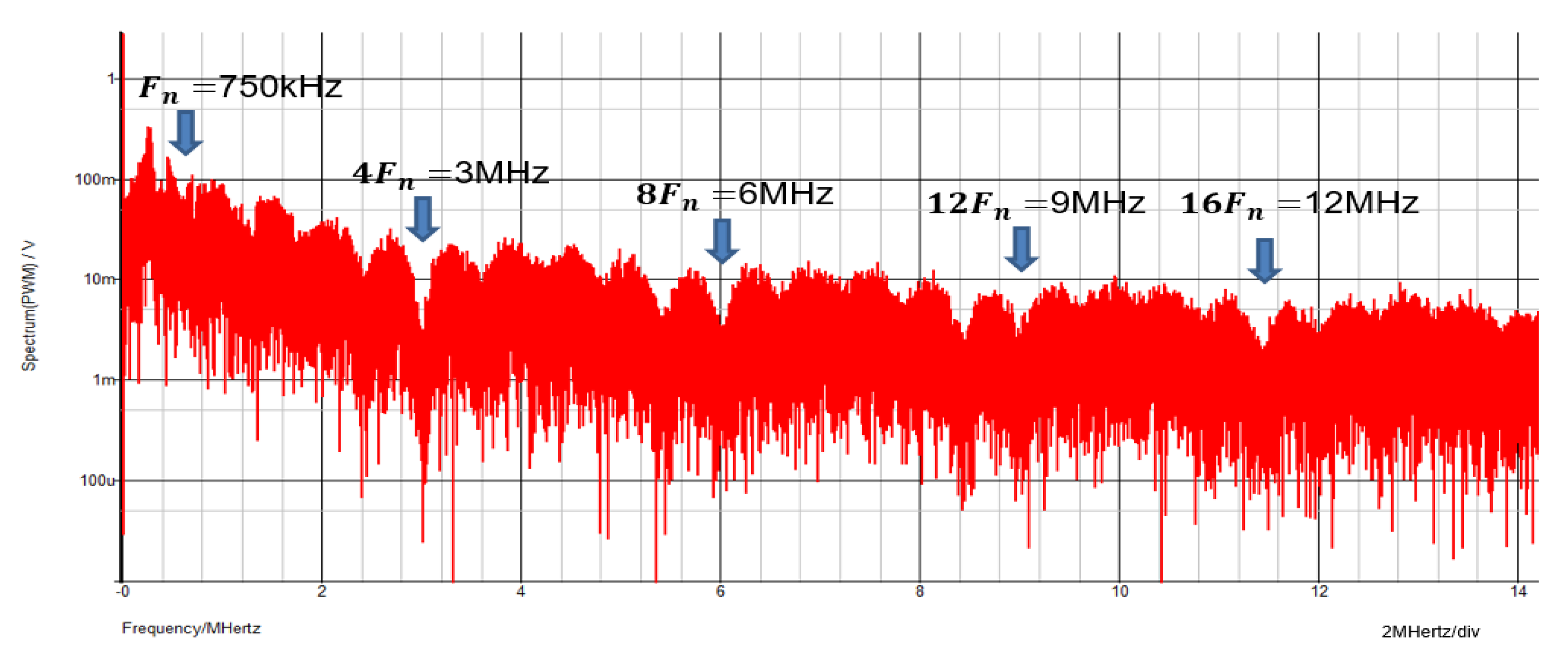

5. Automatic Notch Generation [19,20,21,22,23,24,25]

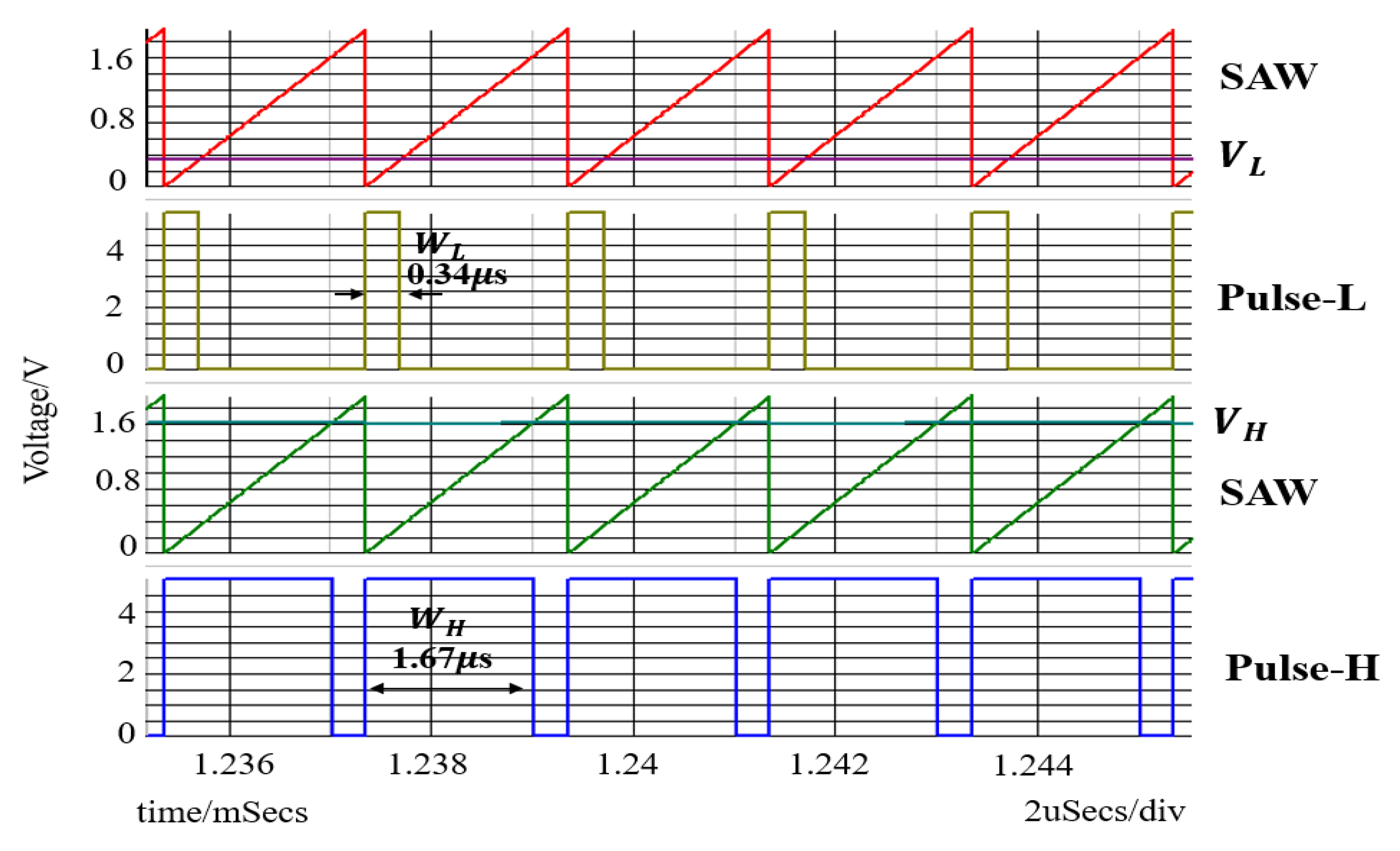

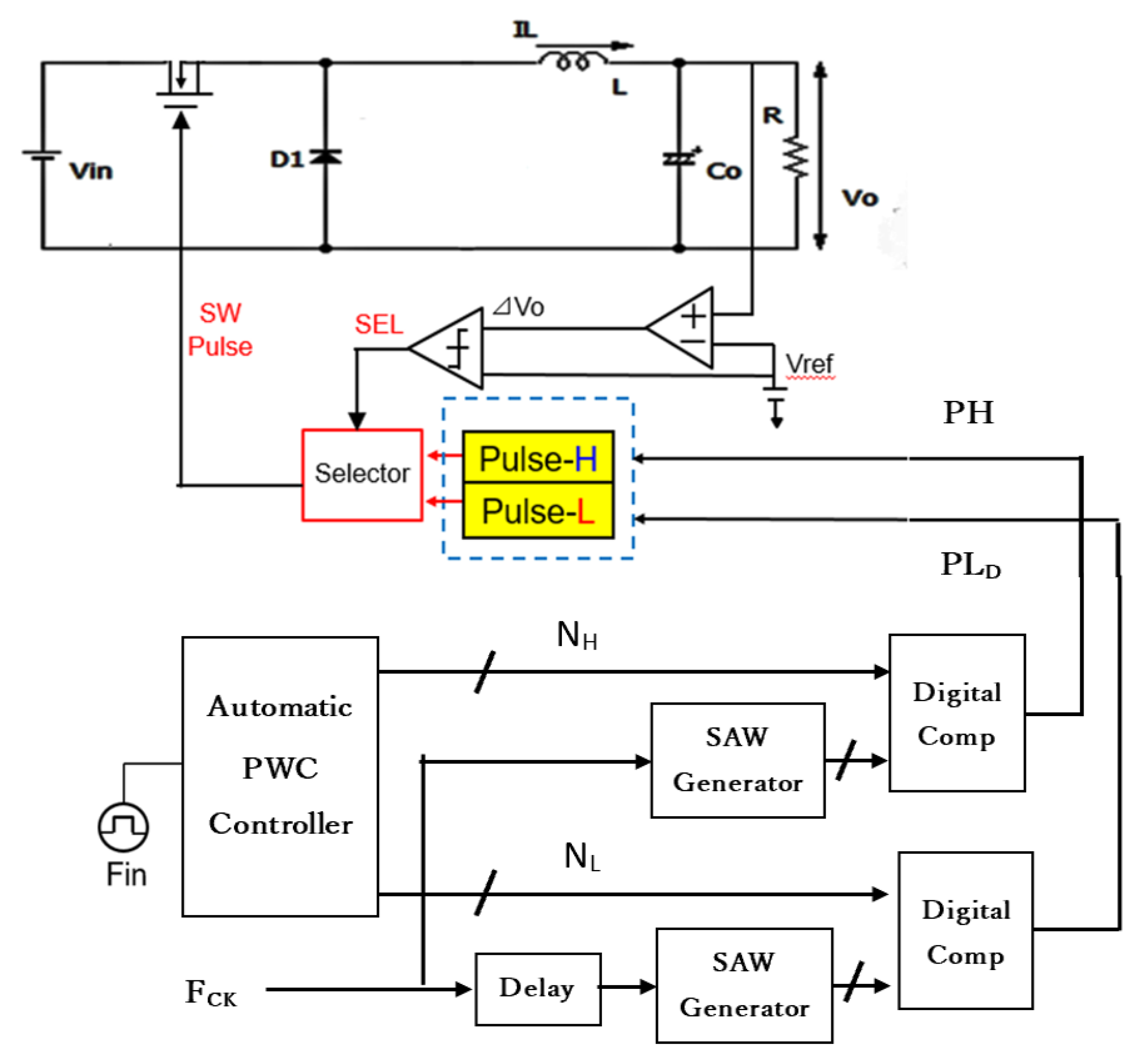

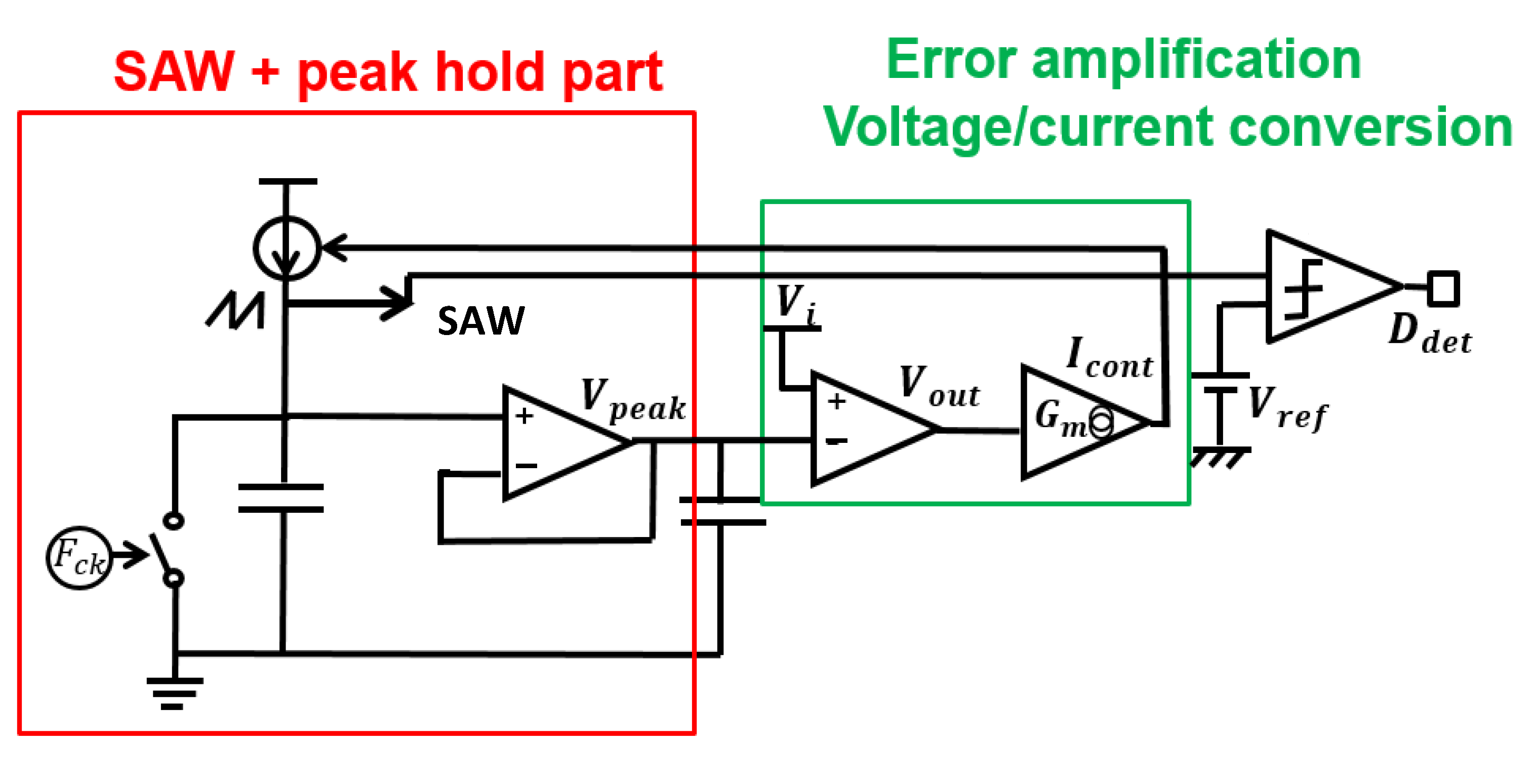

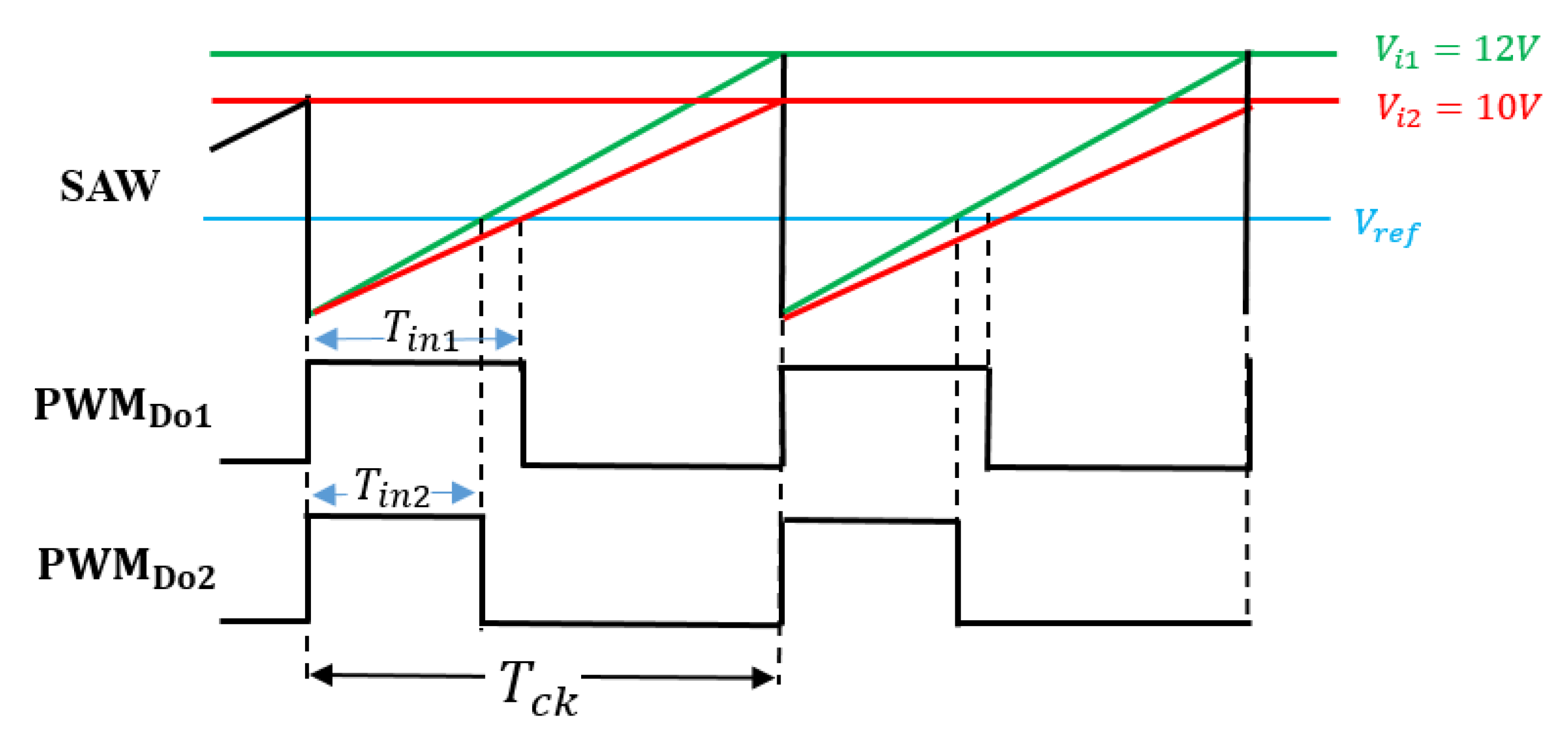

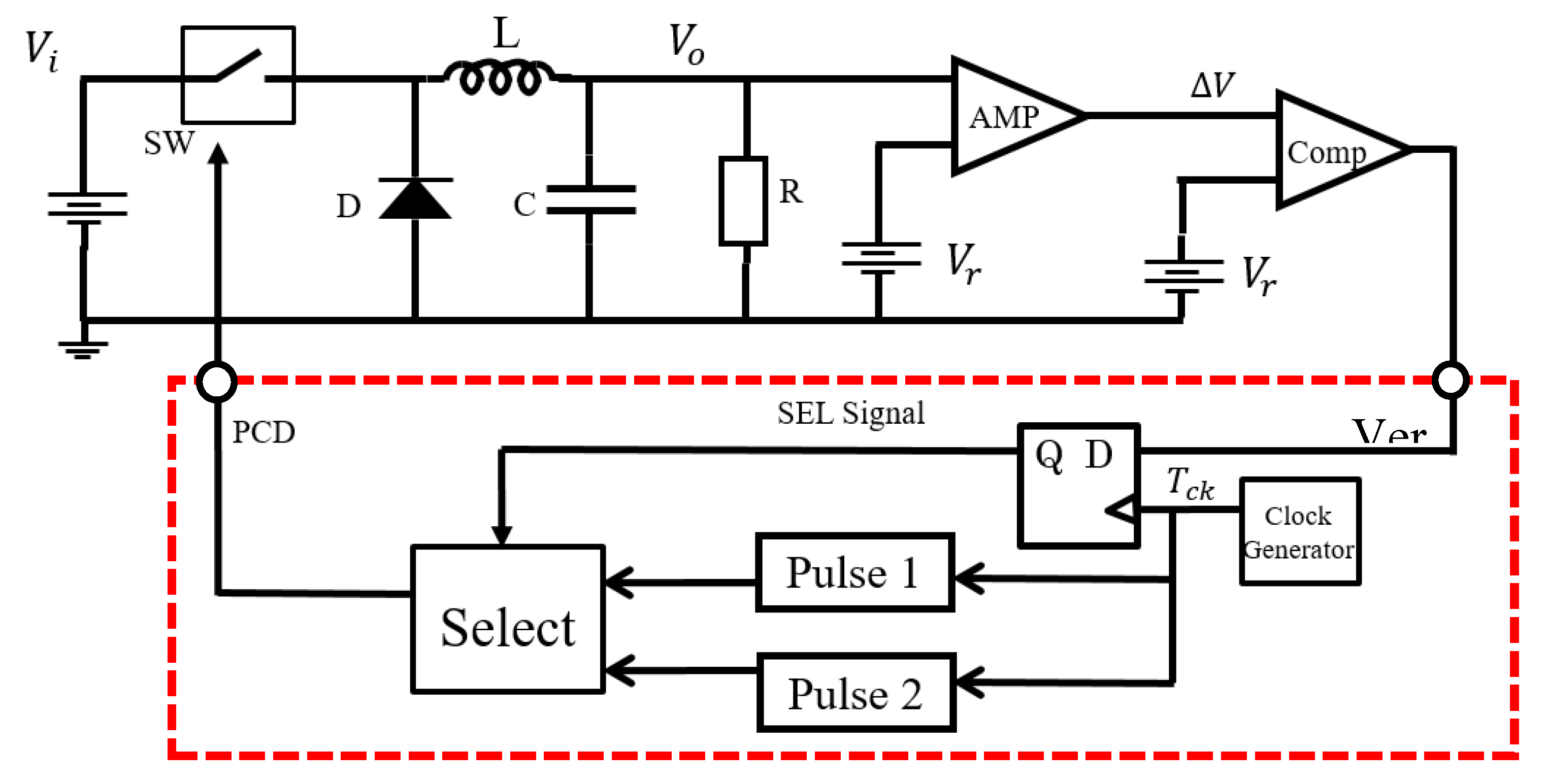

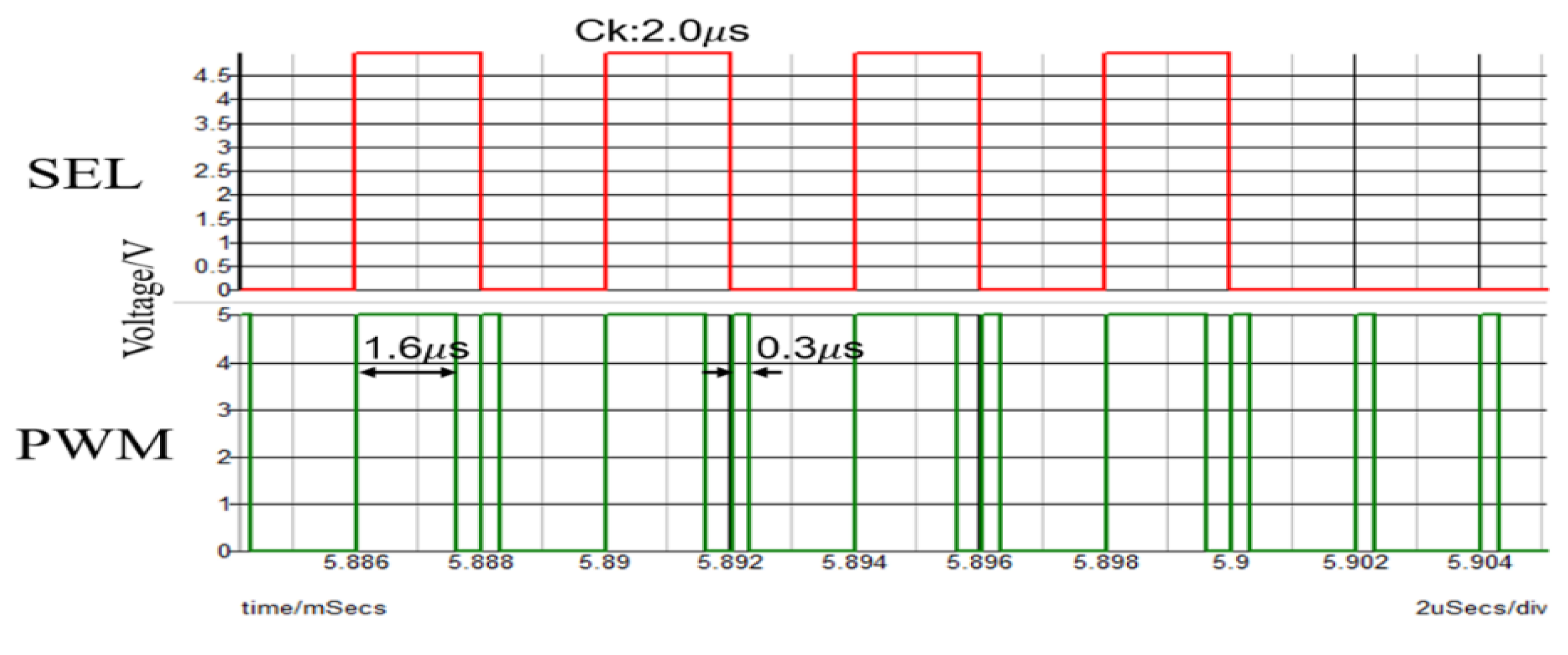

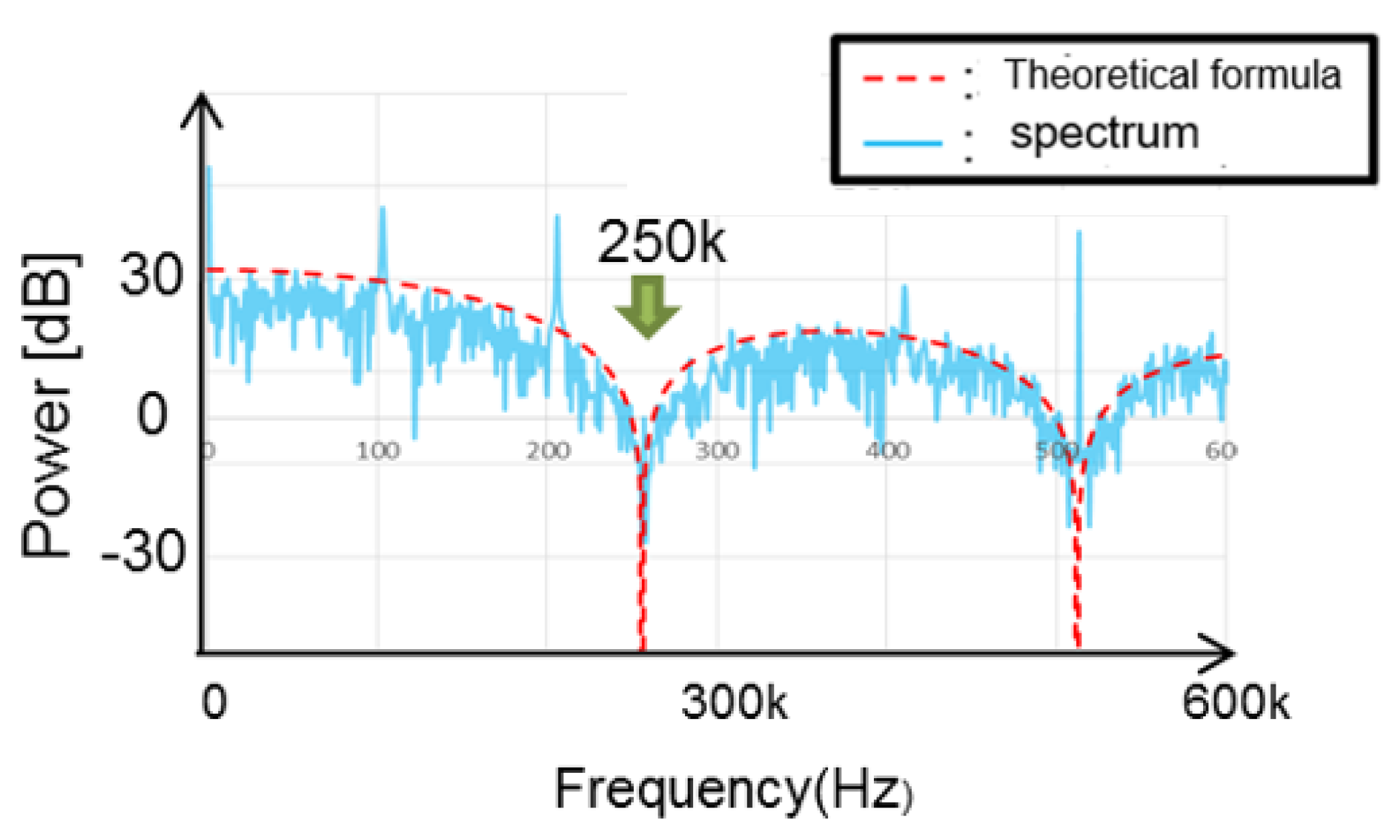

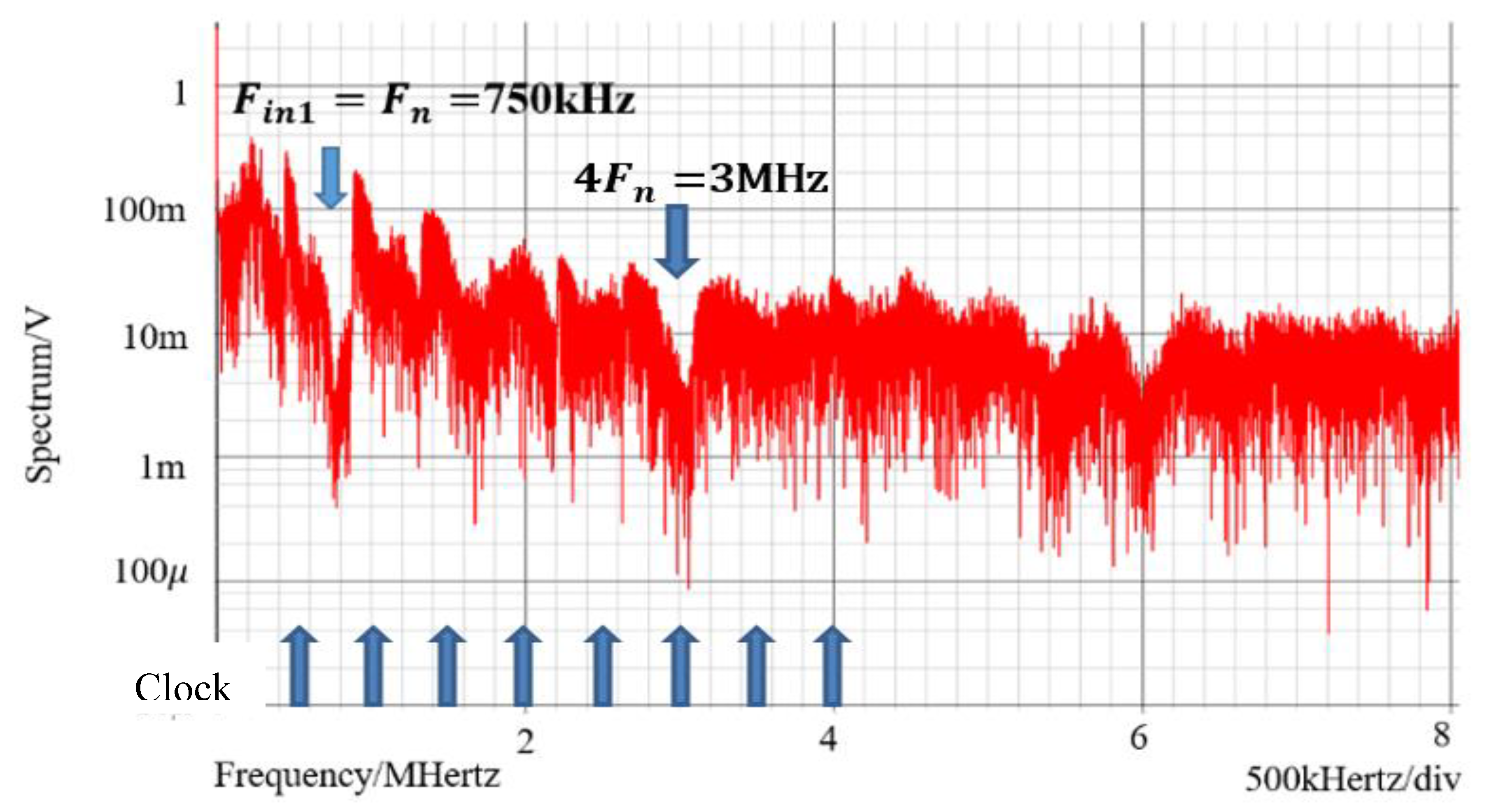

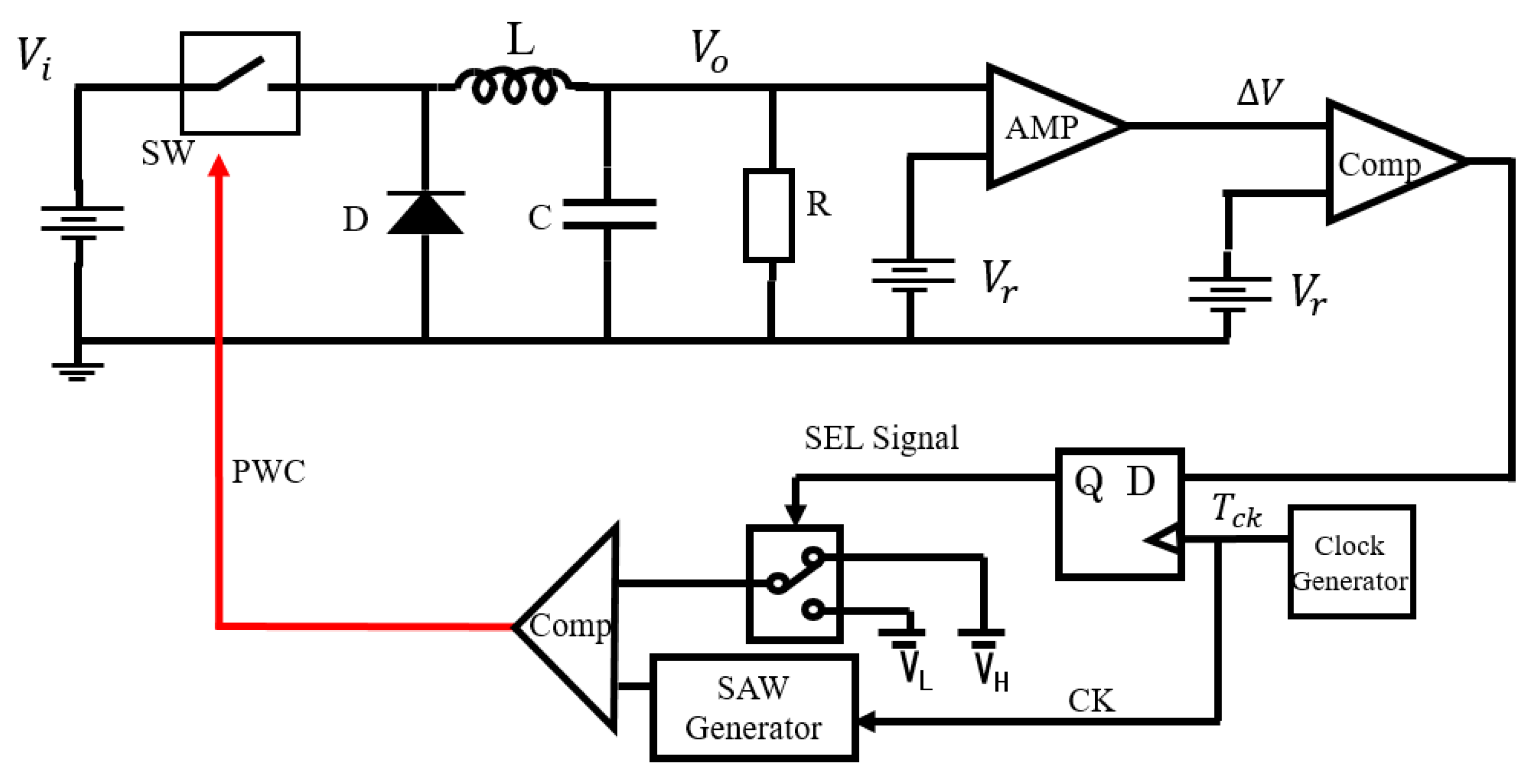

5.1. Automatic Notch Generation Using PWC Control

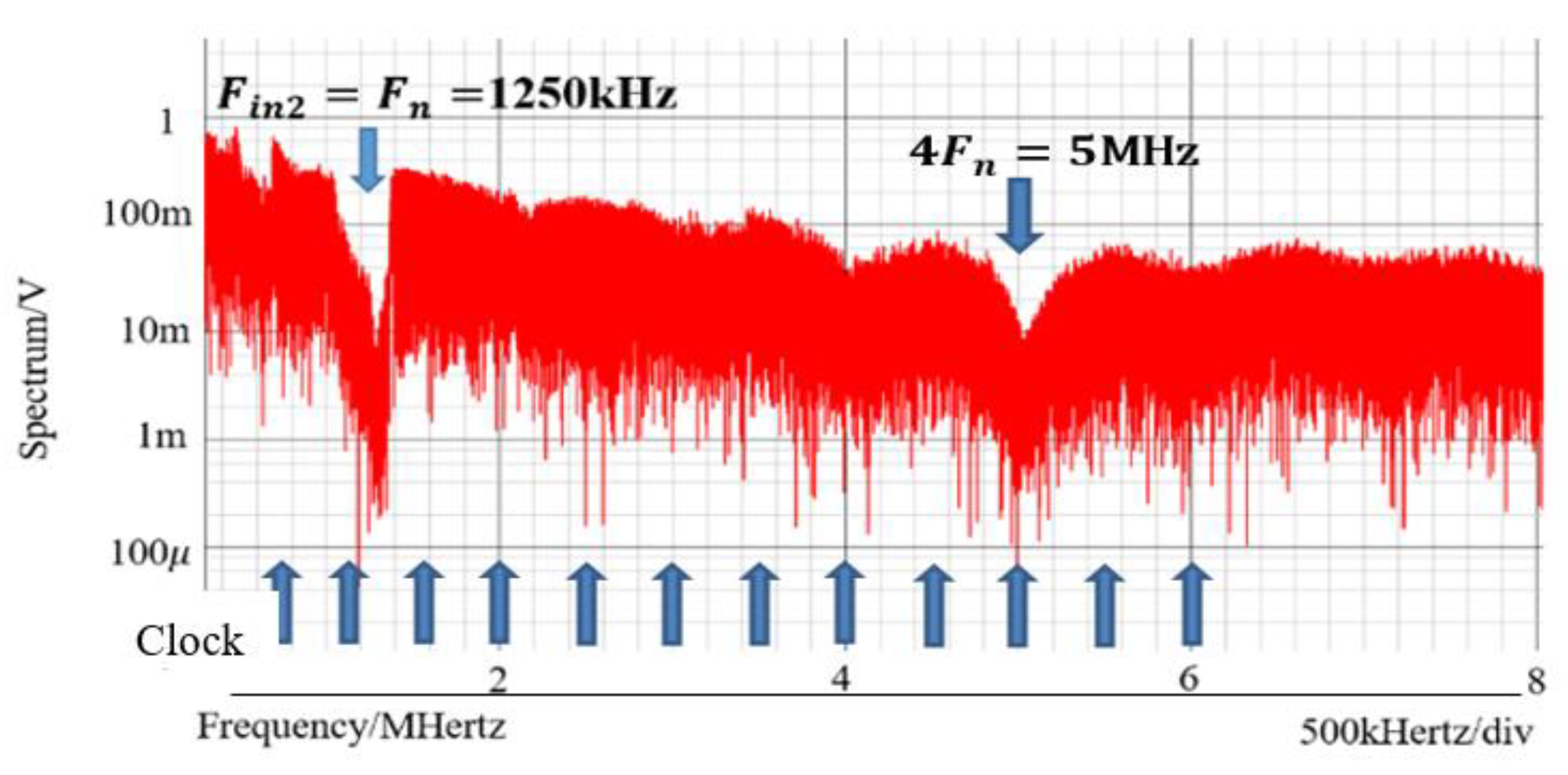

5.2. Automatic Notch Generation with PWPC Control

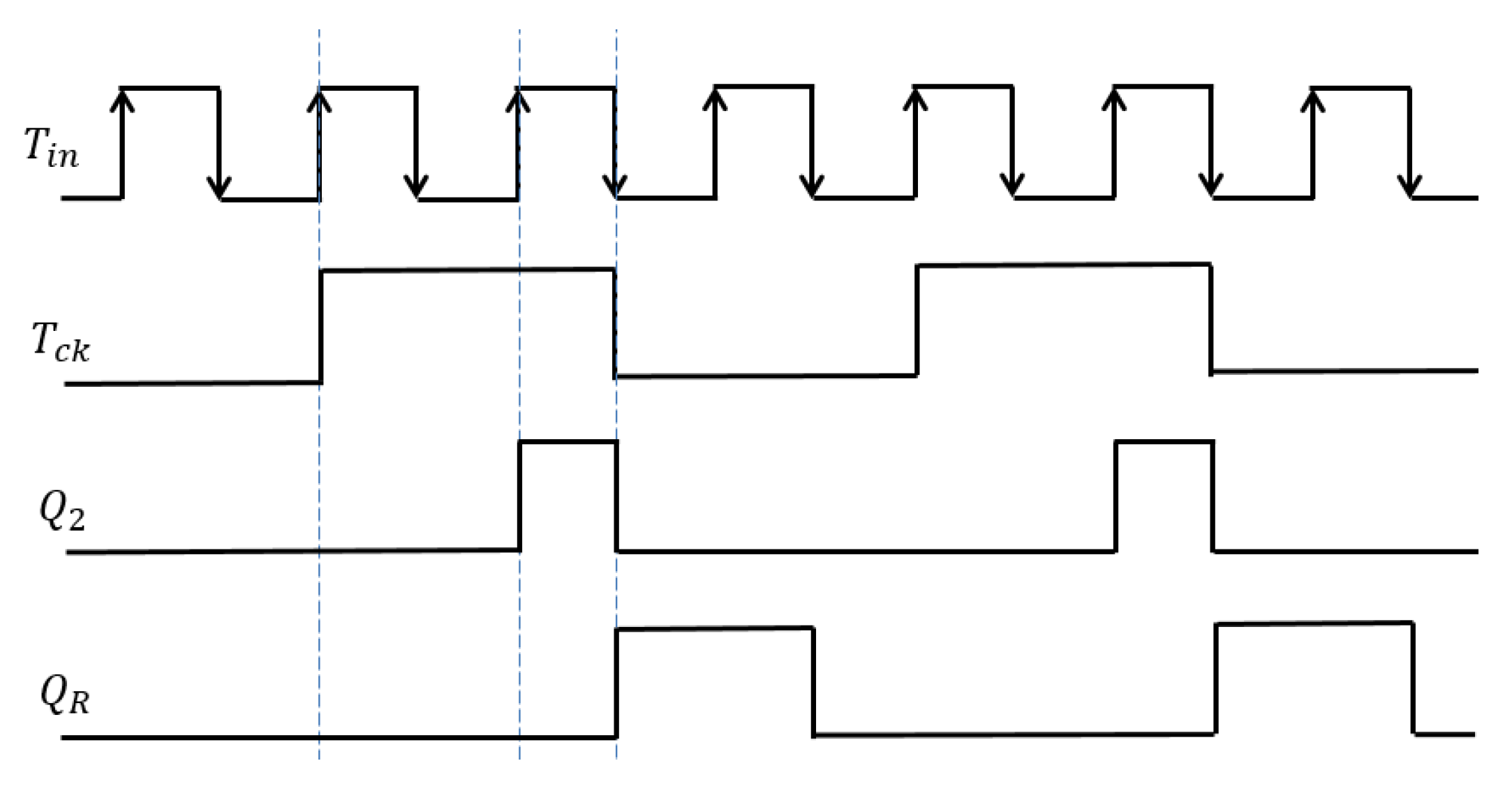

5.3. Duty Ratio Generation in Automatic Notch Generation

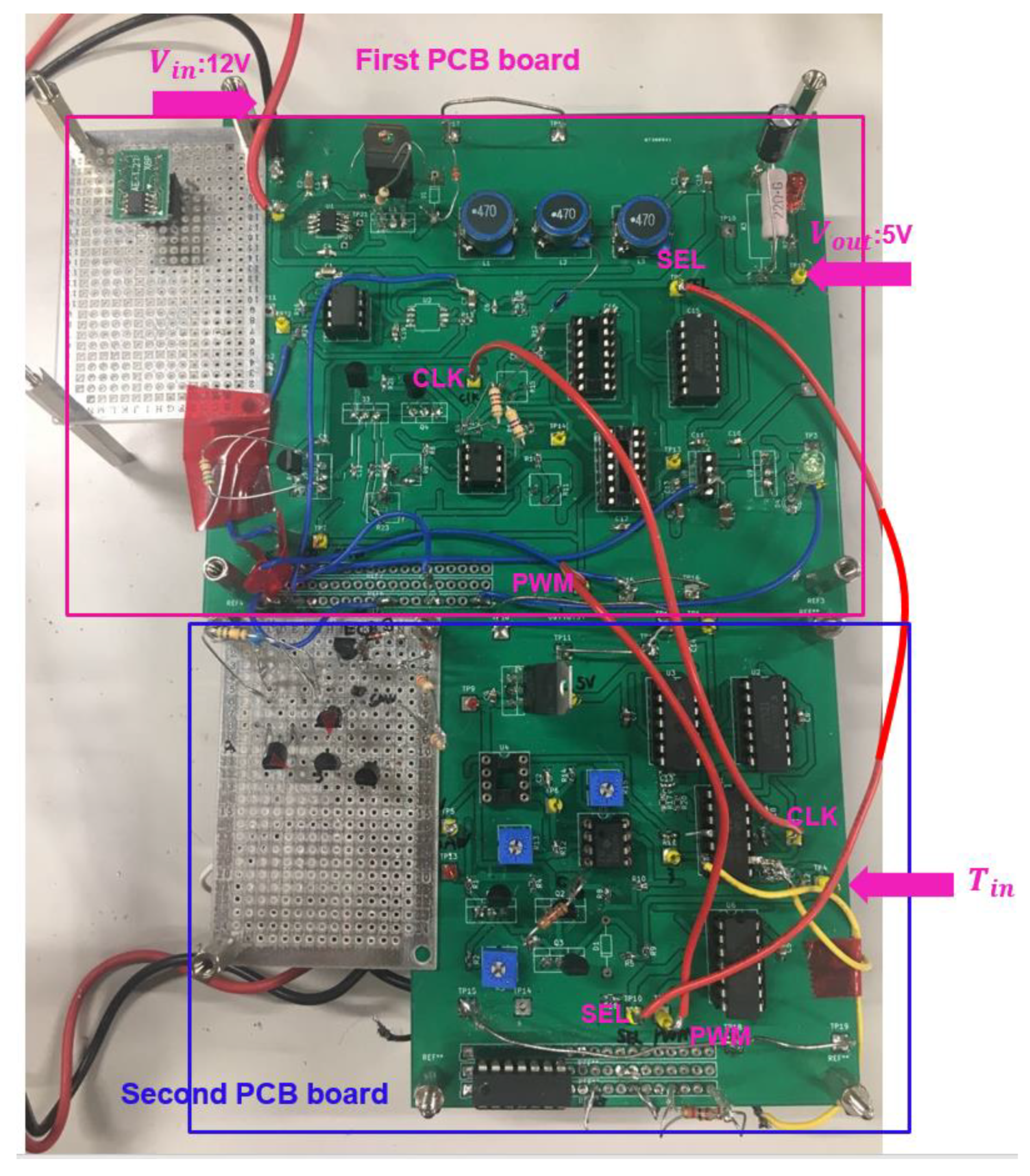

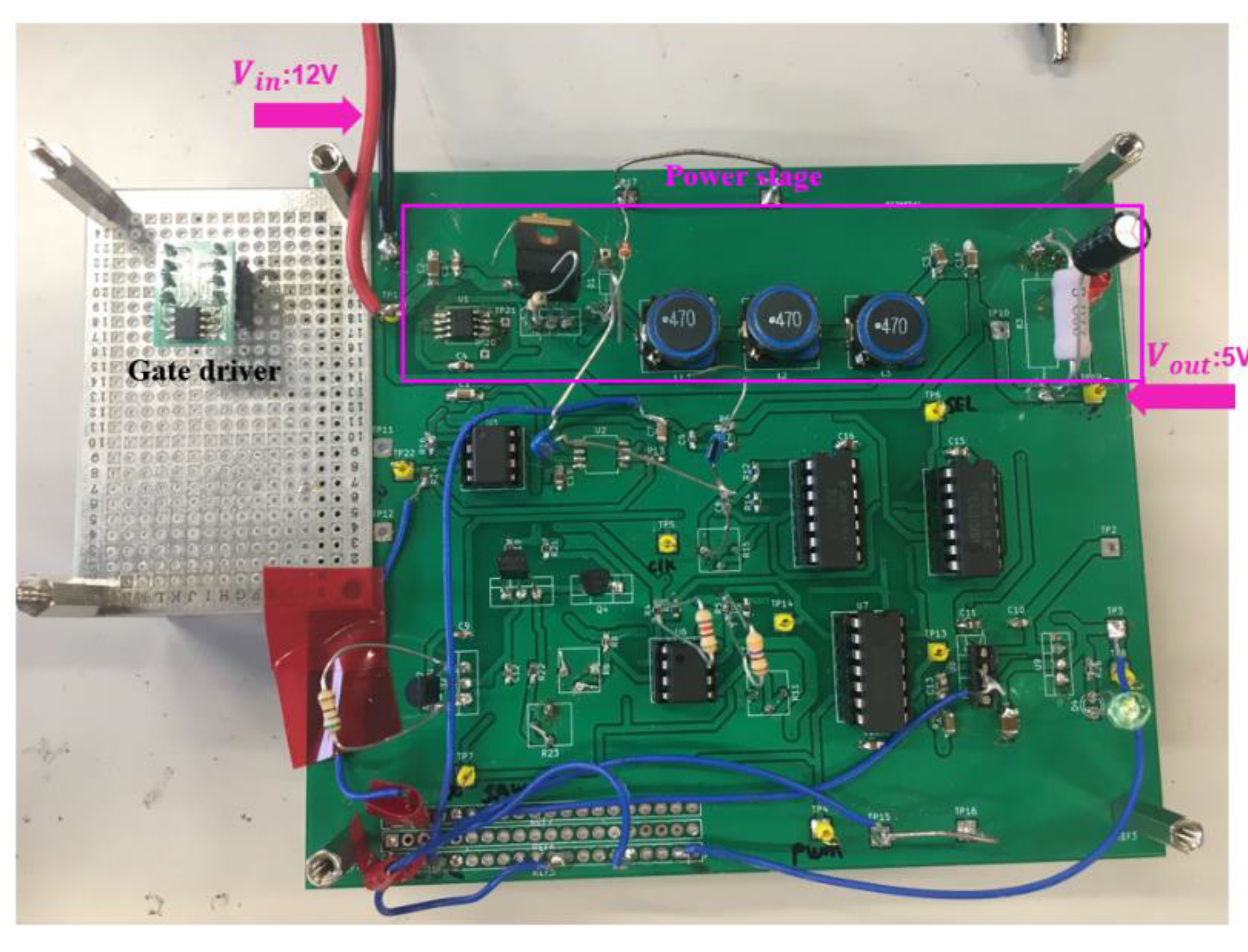

6. Implementation of PWC Controlled Converter with Notch Generation

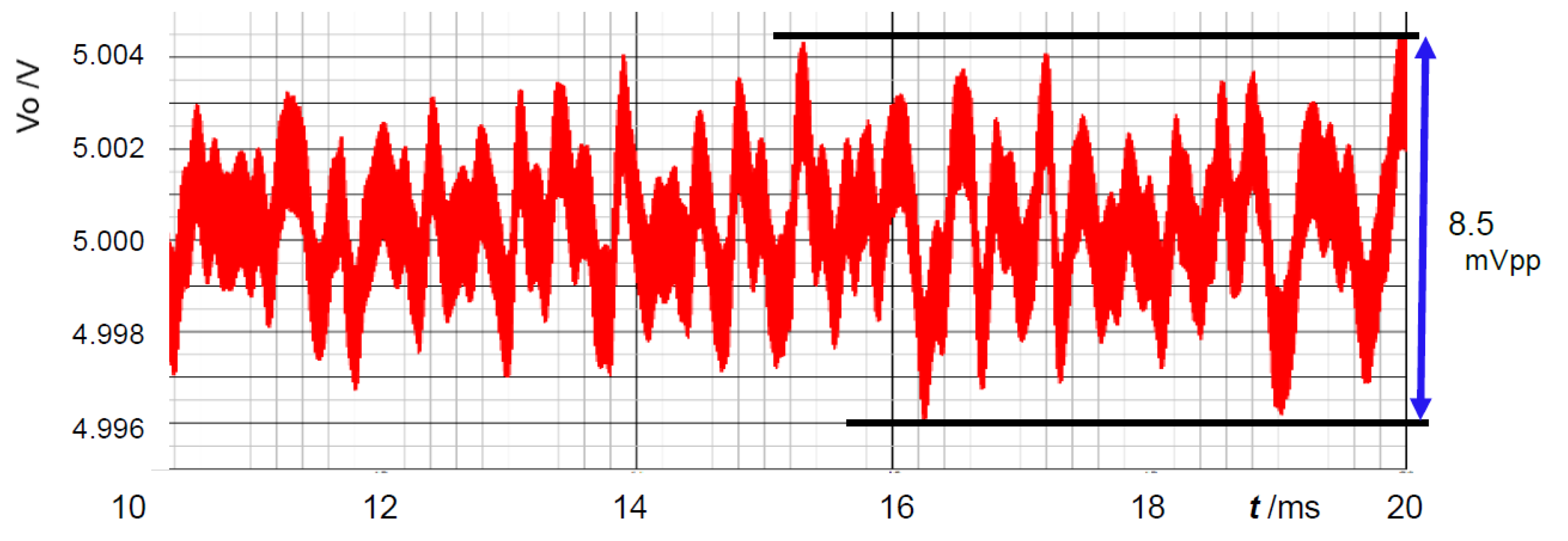

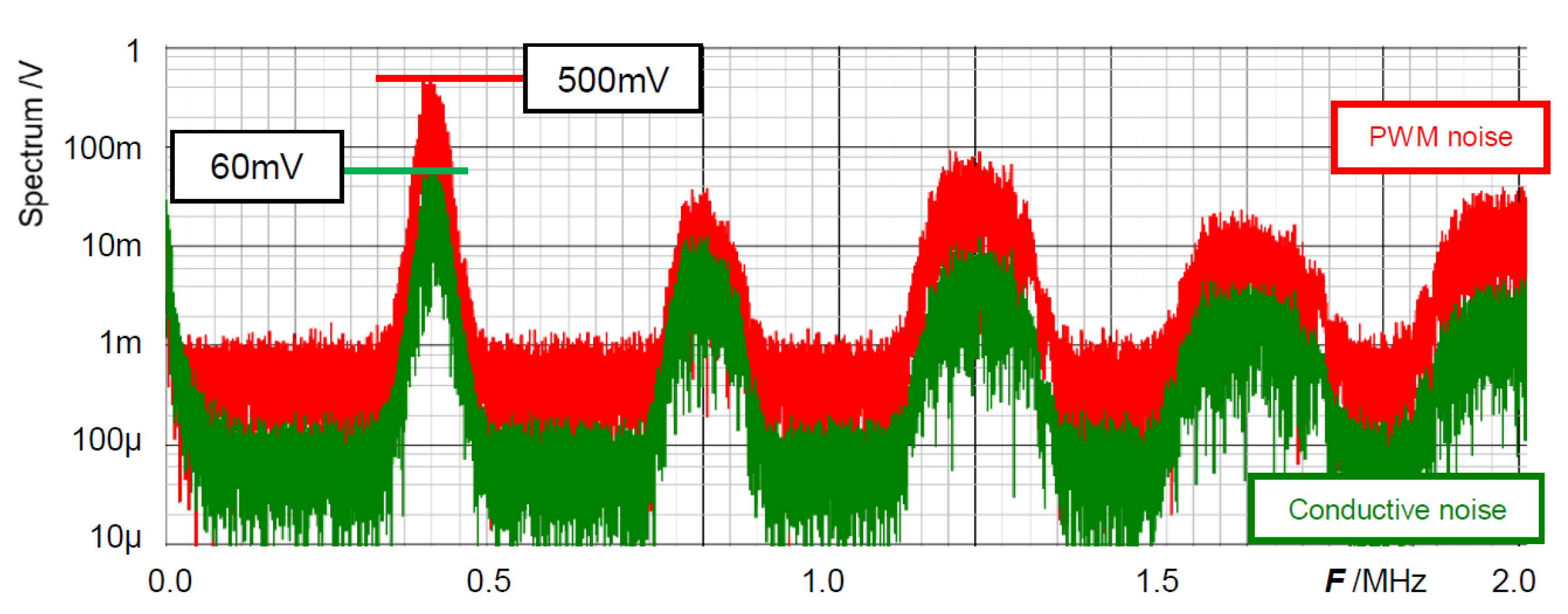

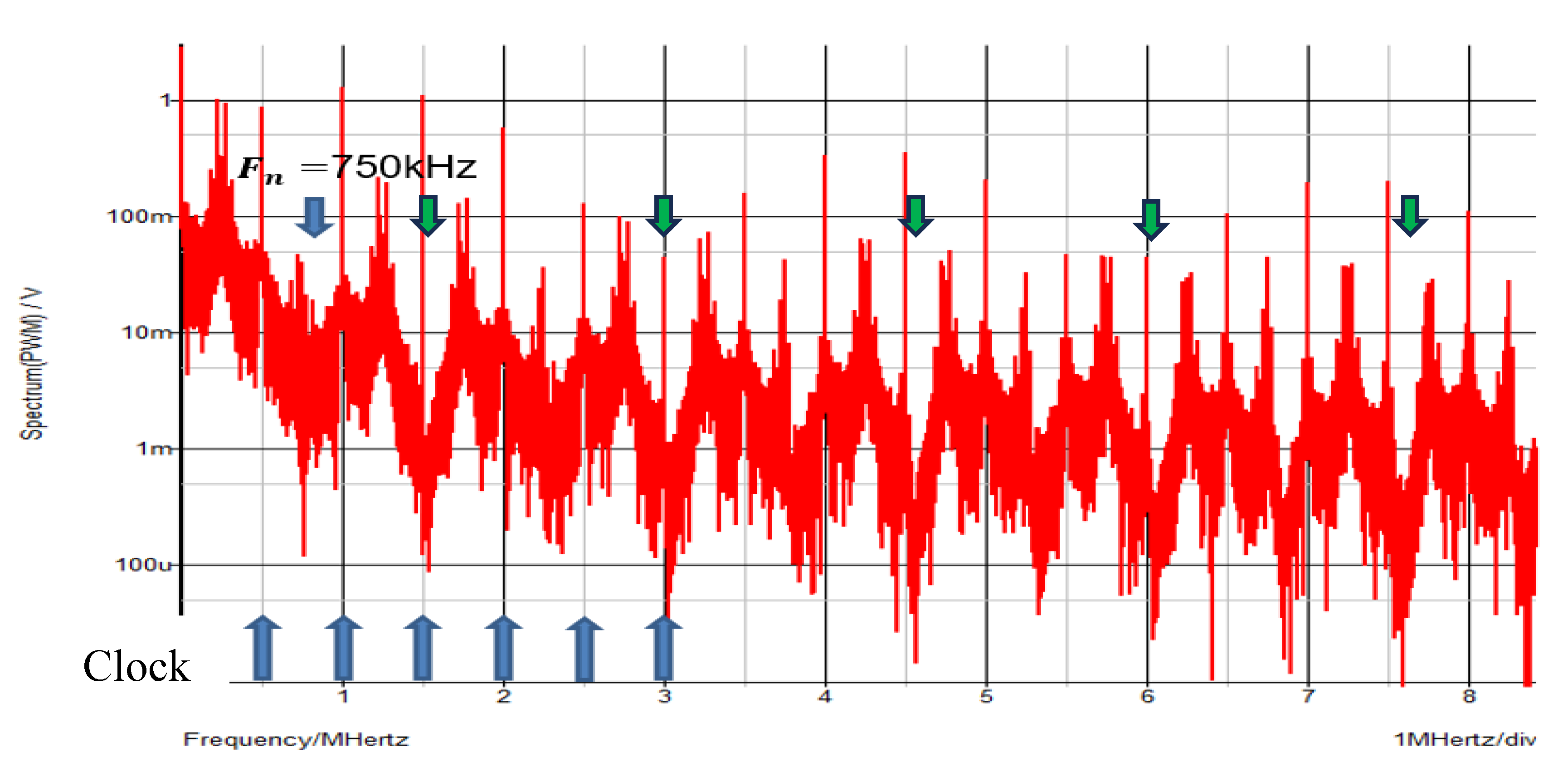

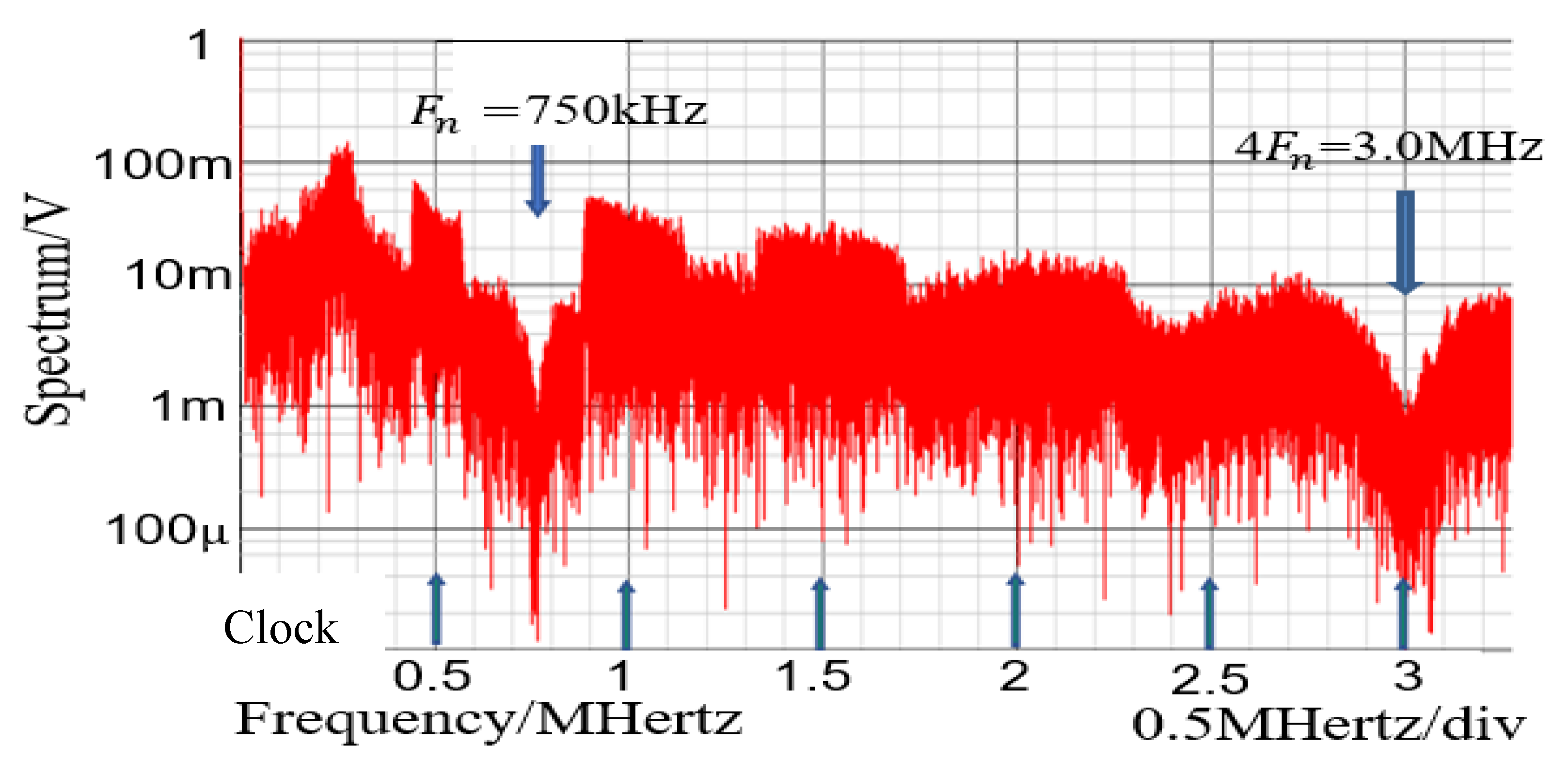

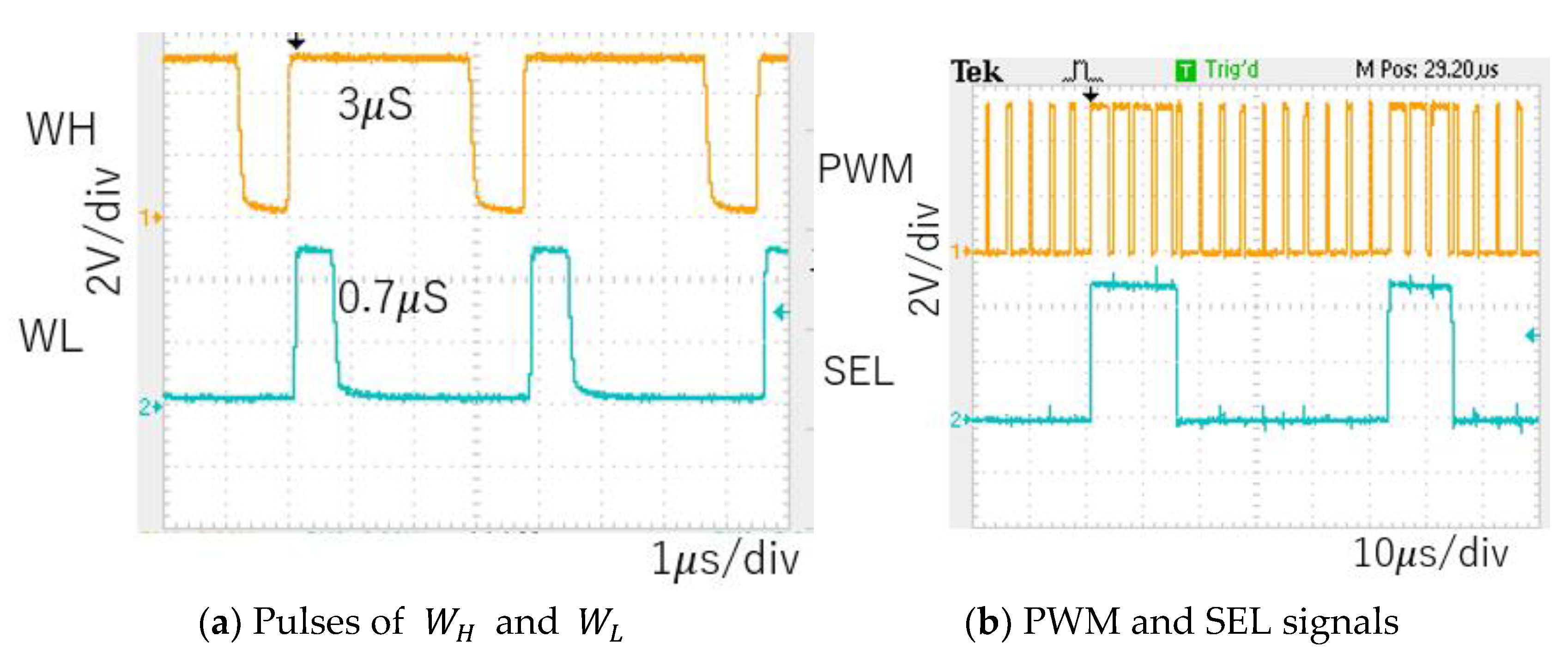

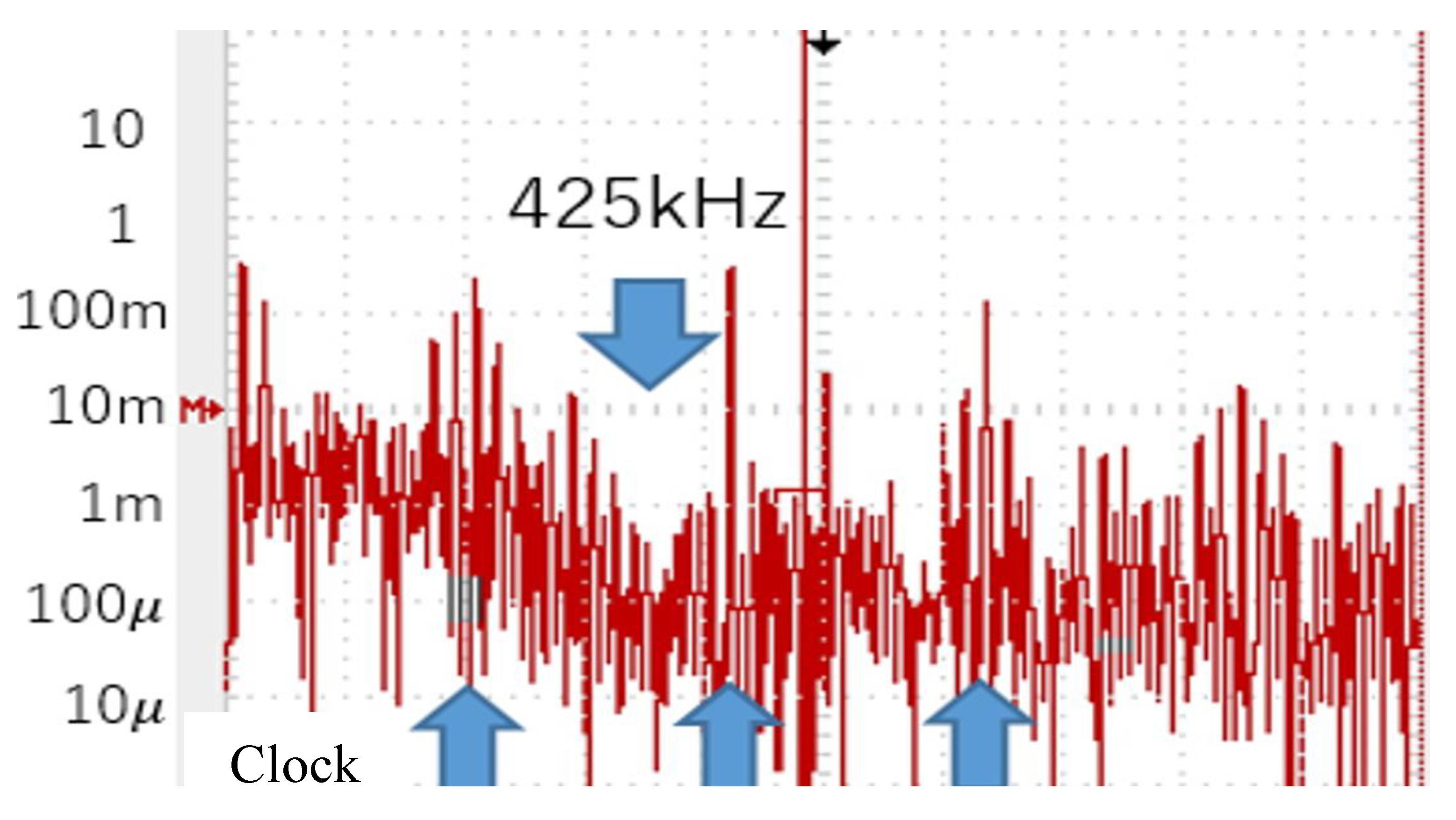

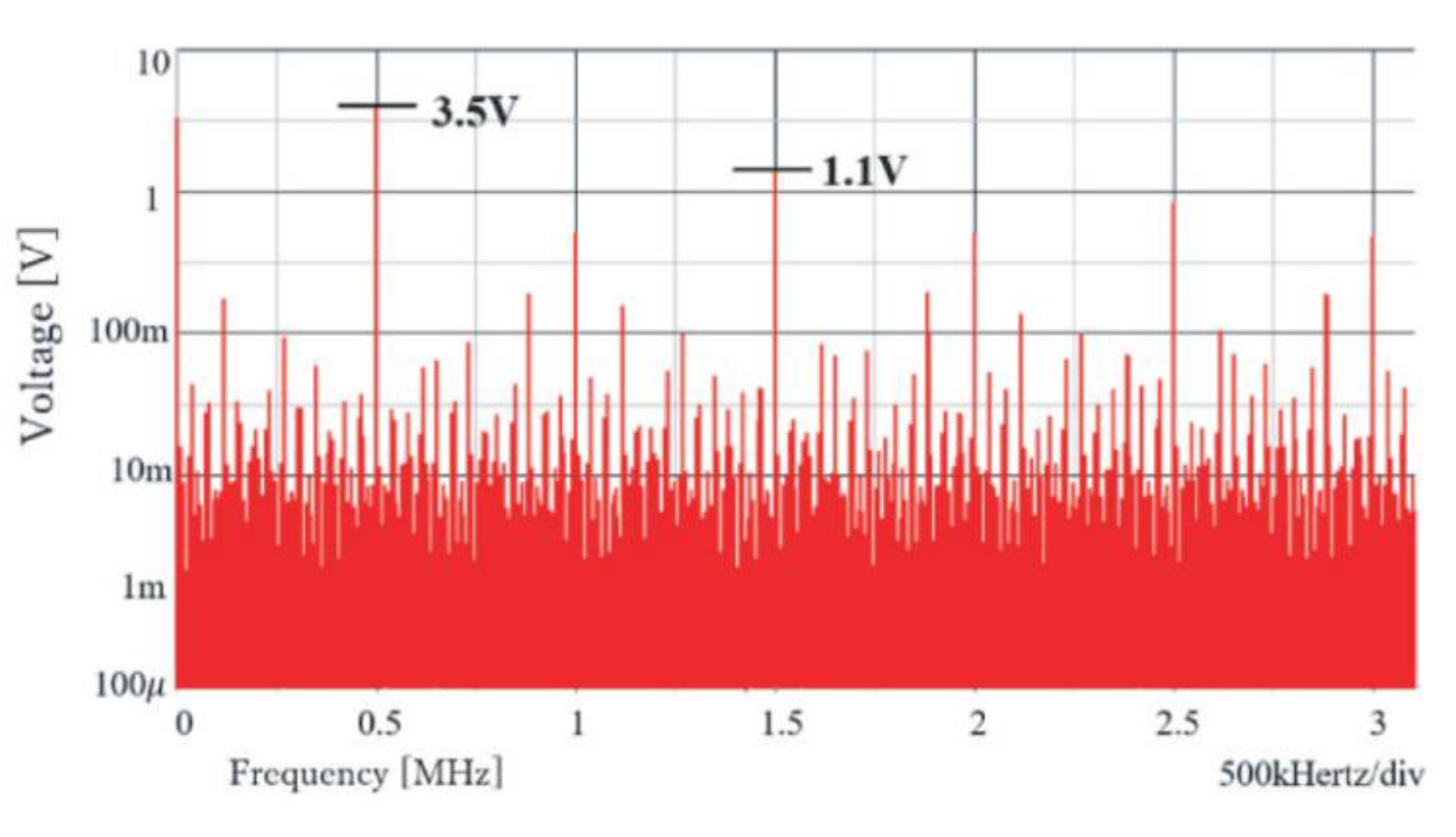

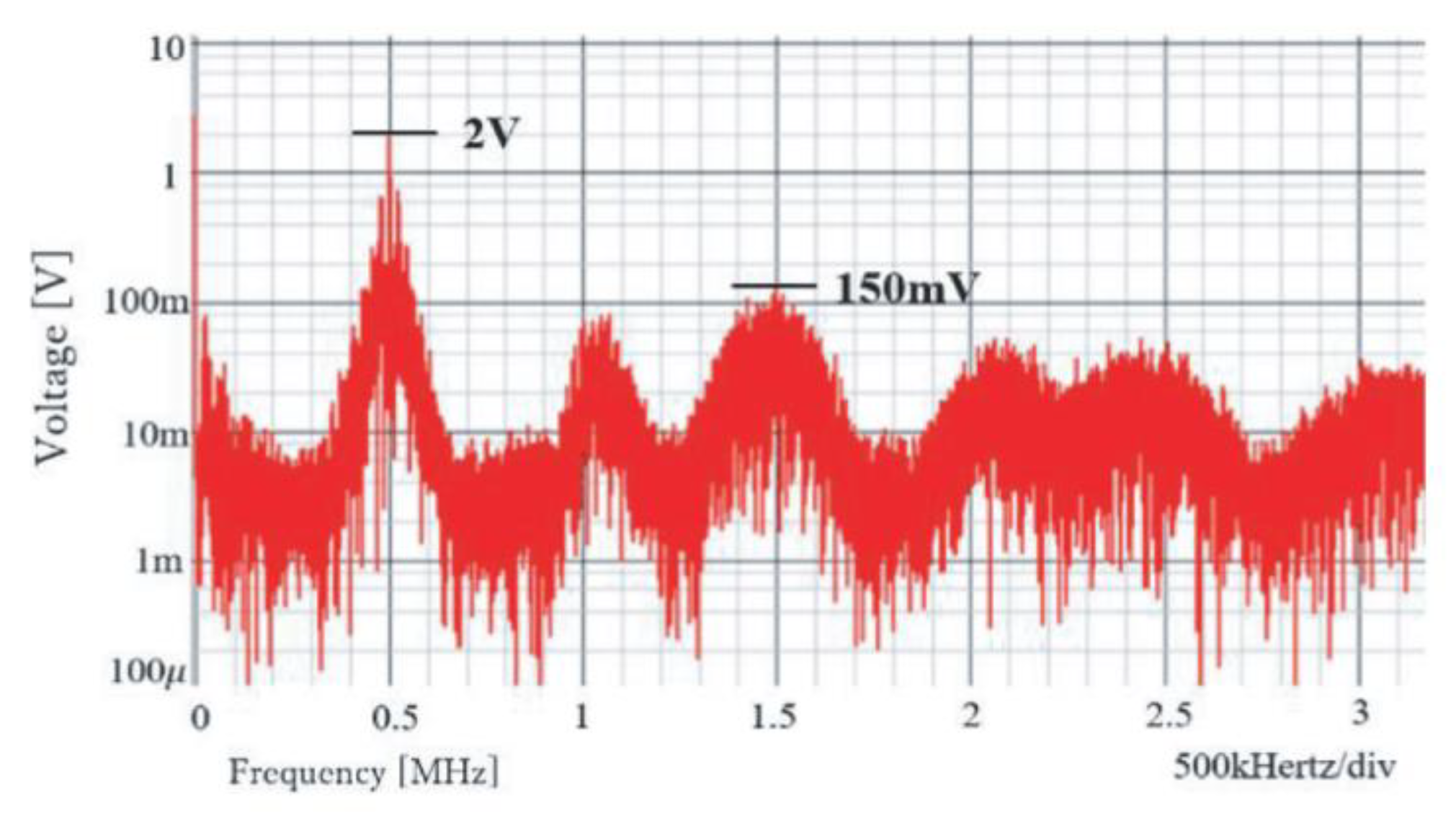

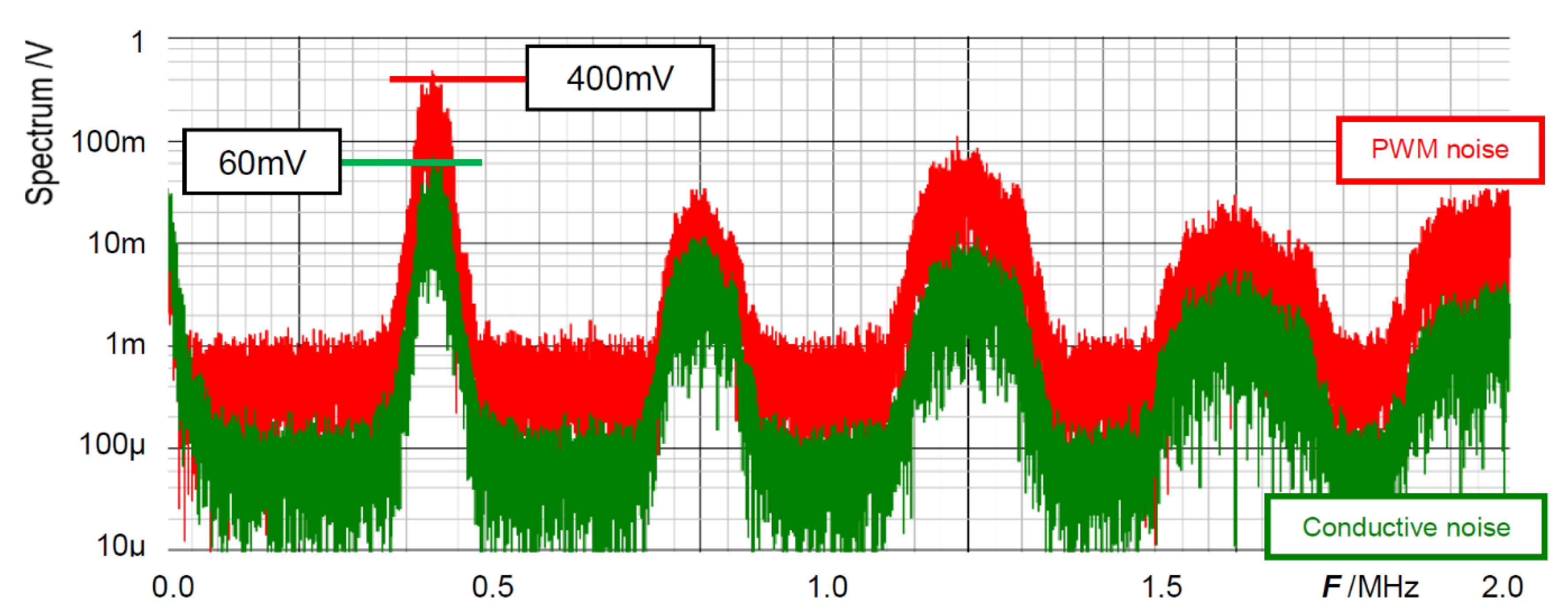

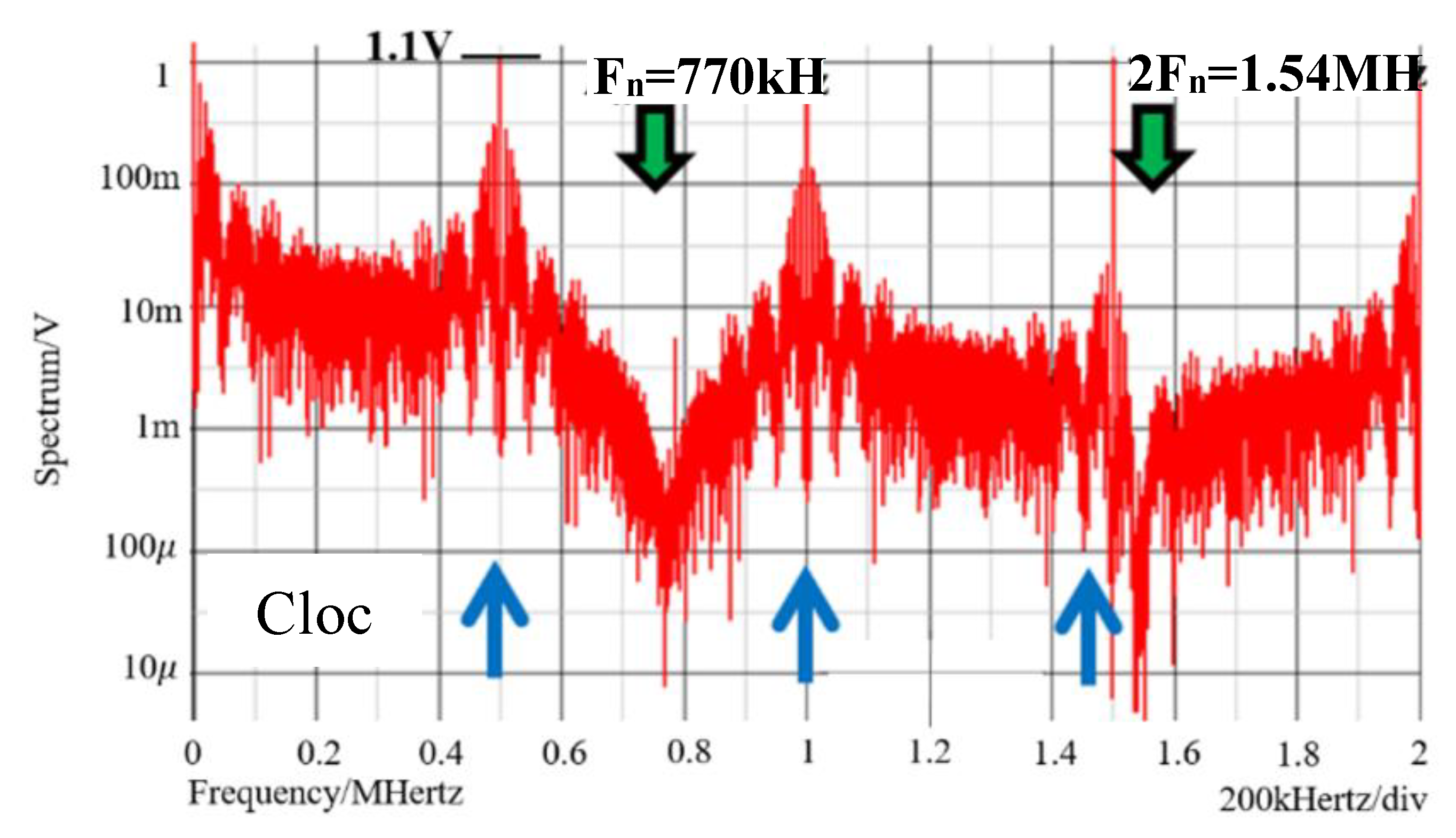

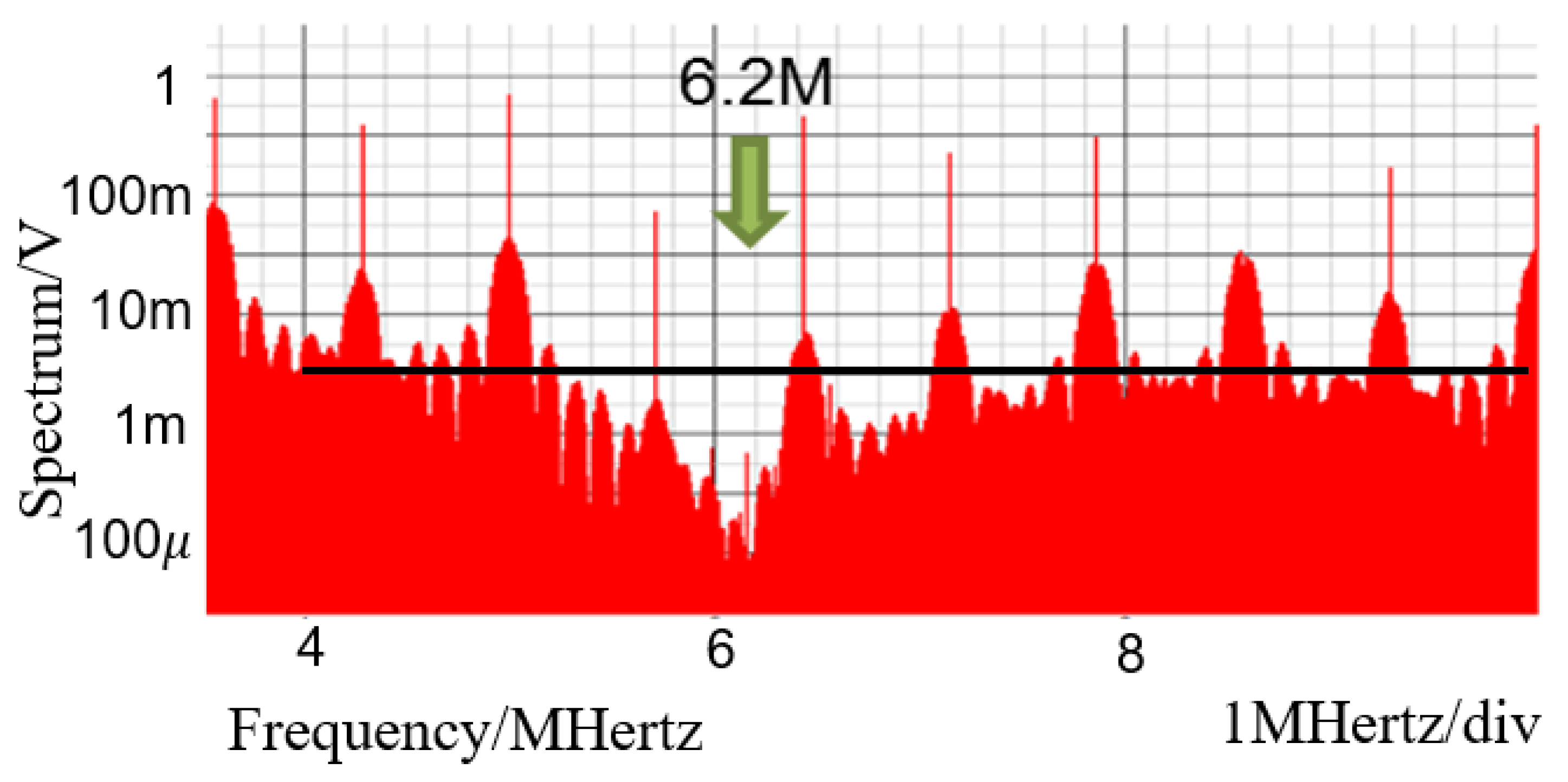

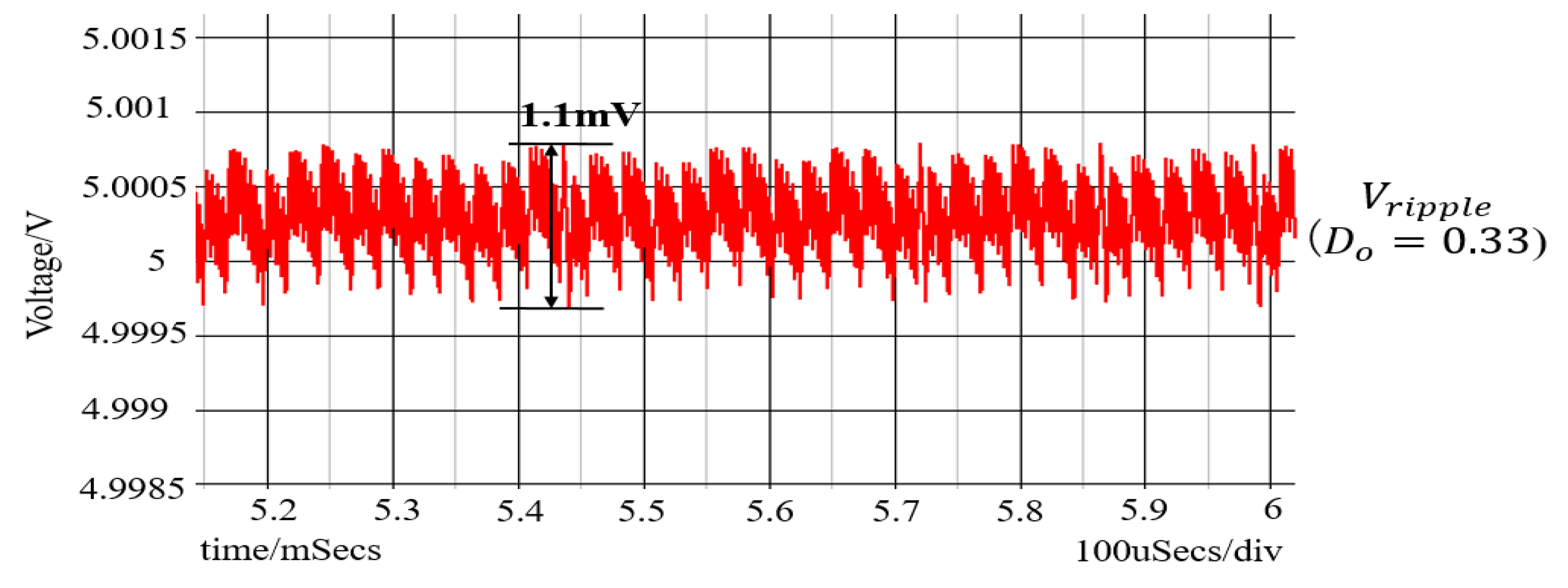

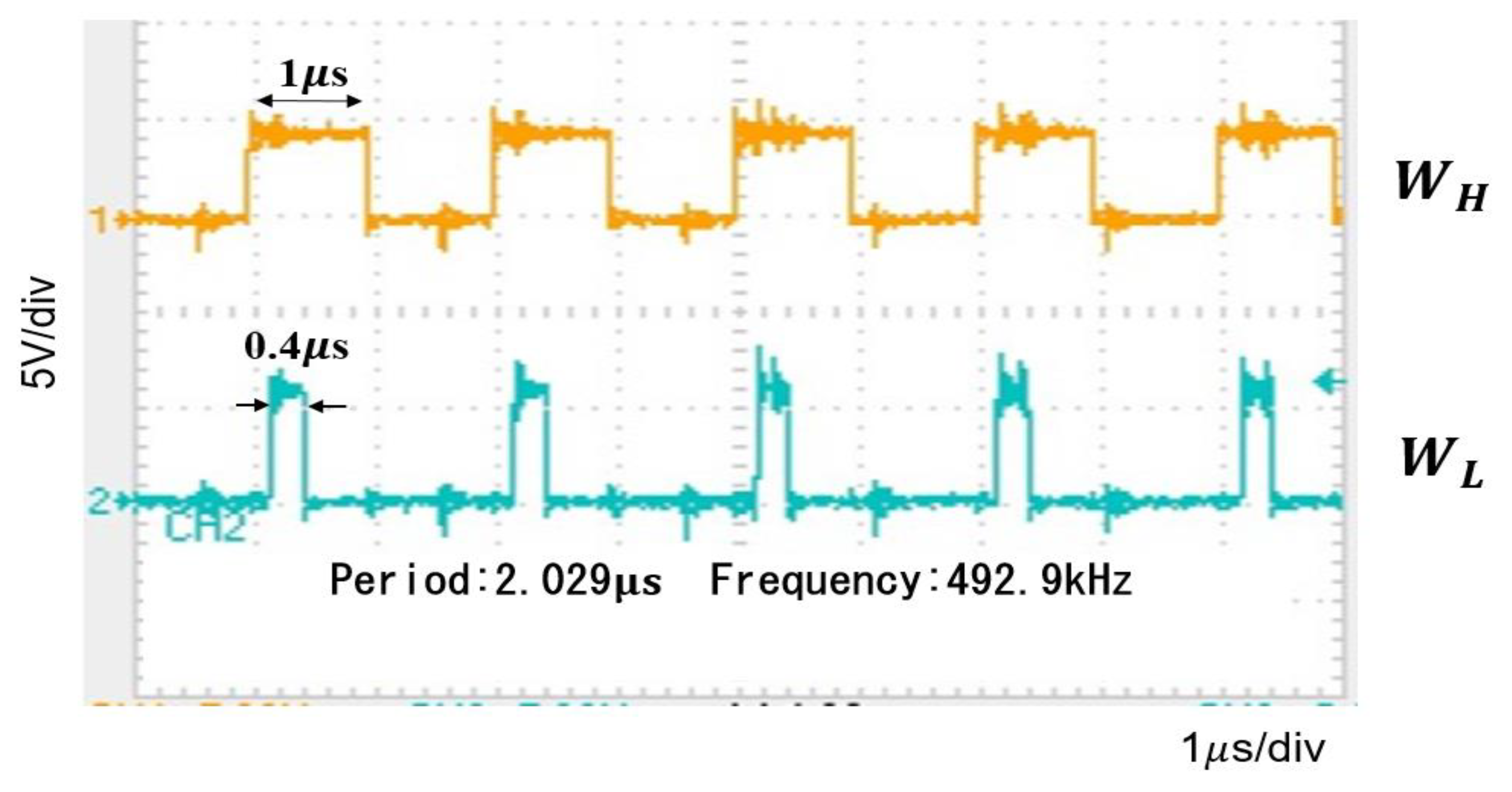

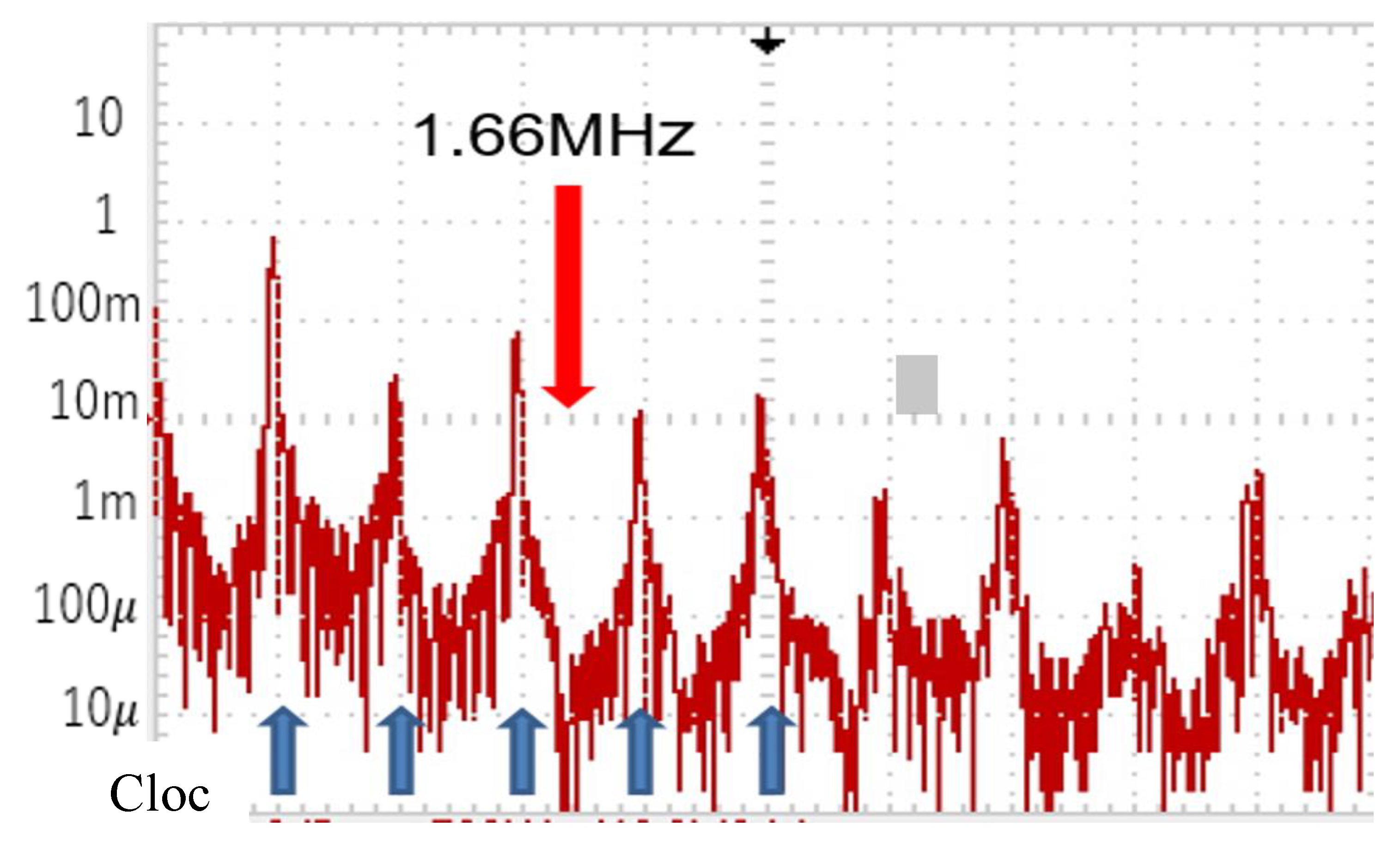

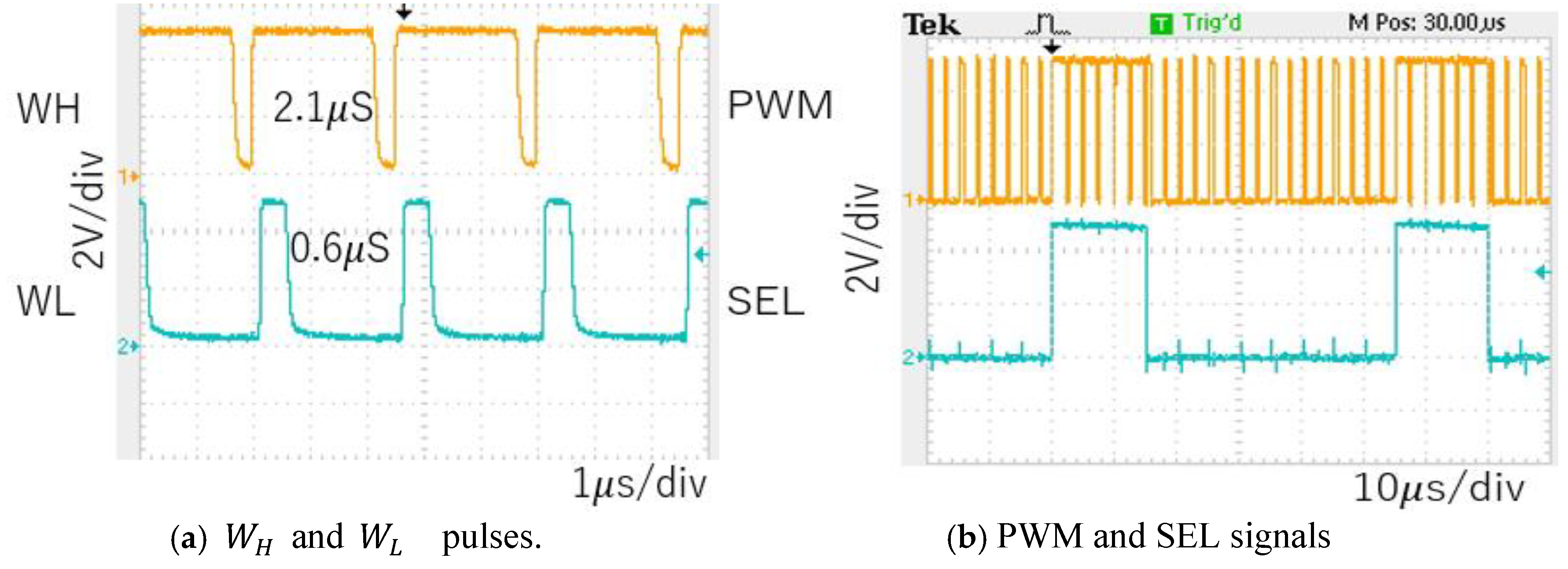

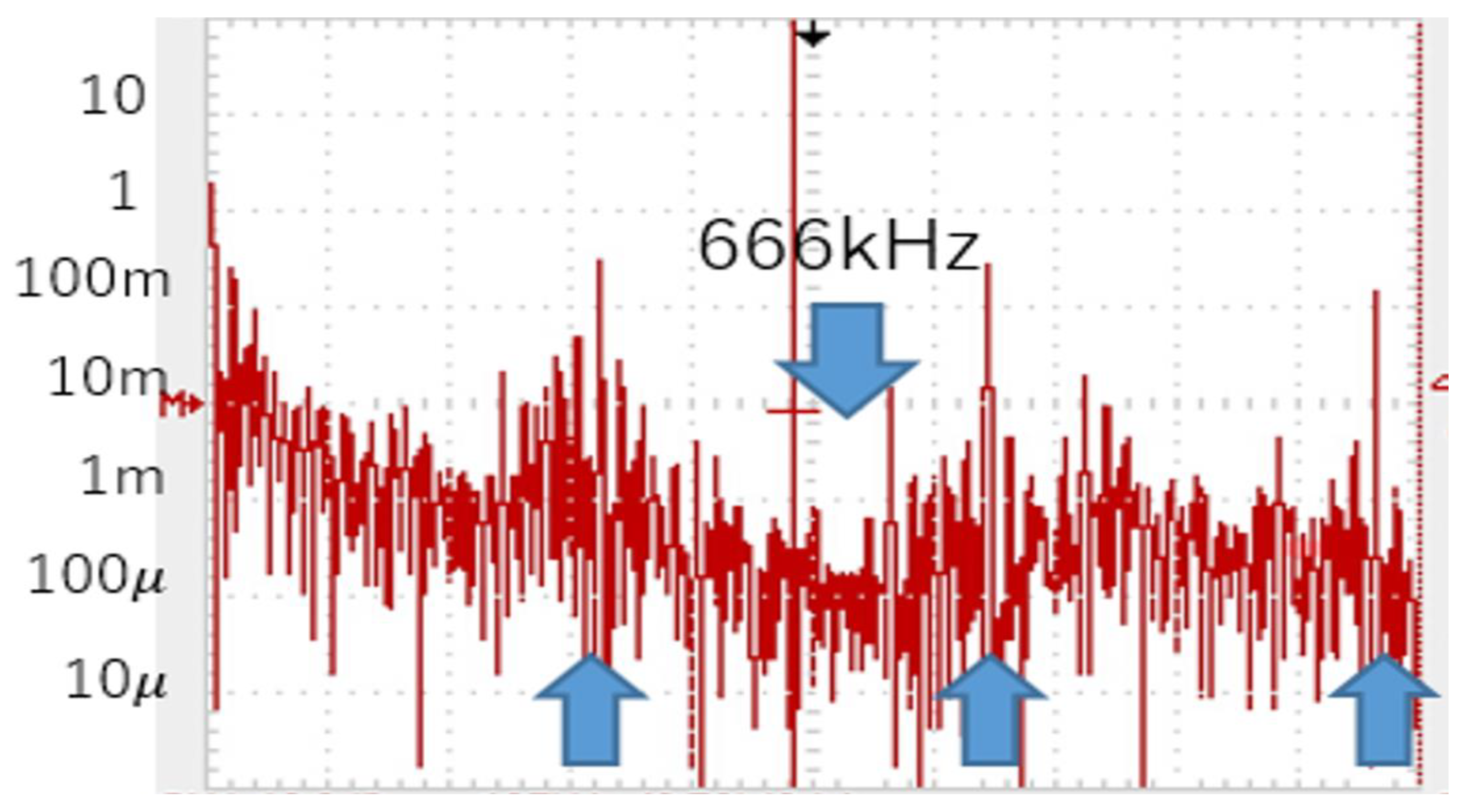

6.1. Experiment of Converter with Notch Generation

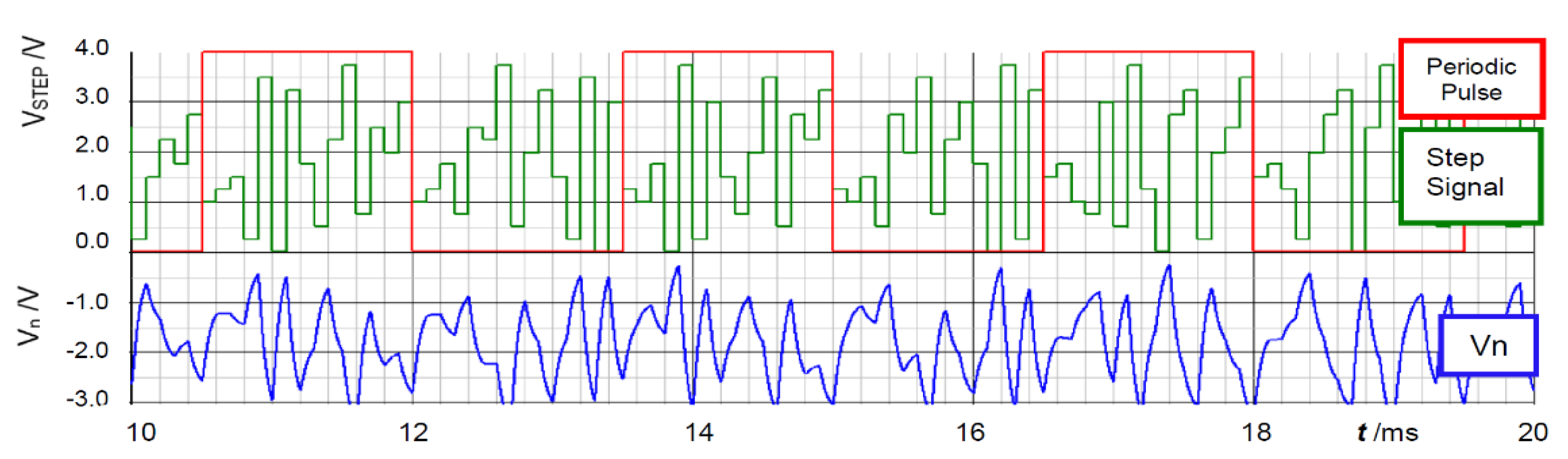

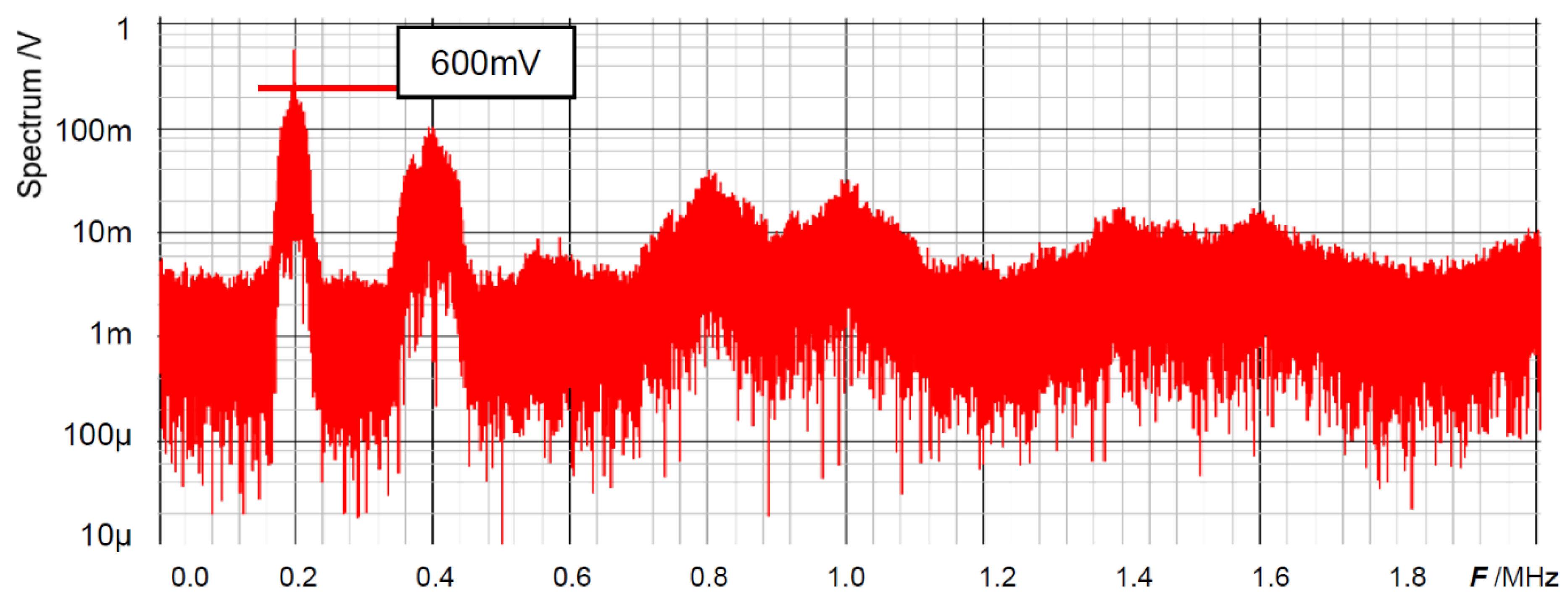

6.2. Experiment of Automatic Notch Generation

7. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

References

- K. Harada, T. Ninomiya, and B. Gu, Circuit Scheme of PWM Converter in Basics of Switching Converter, Corona Publishing, Japan (1992).

- A. J. Stratakos, C. R. Sullivan, S. R. Sandersand, R. W. Broderson, “High-Efficiency Low-Voltage DC-DC Conversion for Portable Applications in Low-Voltage/Low-Power Integrated Circuits and Systems,” Chapter 12, IEEE Press (1999).

- A. M. Trzynadlowski, Z. Wang, J. M. Nagashima, C. Stancu, and M. H. Zelechowsk, “Comparative Investigation of PWM Techniques for a New Drive for Electric Vehicles,” IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl, vol. 39, no. 5, pp. 1396-1403 (Sep. 2003).

- Robert W. Erickson, Dragan Maksimović, Fundamentals of Power Electronics, The Third Edition, Springer (2020).

- K. Taniguchi, T. Sato, T. Nabeshima and K. Nishijima, “Constant frequency hysteretic PWM controlled buck converter,” International Conference on Power Electronics and Drive Systems (PEDS), pp. 1194-1199 Taipei, Taiwan, (2009).

- R. Lai, Y. Maillet, F. Wang, S. Wang, R. Burgos, and D. Boroyevich, “An Integrated EMI Choke for Differential-mode and Common-mode Noise Suppression,” IEEE Trans. Power Electron, vol.25, no.3, pp. 539-544 (March 2010).

- R. Mukherjee, A. Patra, and S. Banerjee “Impact of a Frequency Modulated Pulse Width Modulation (PWM) Switching Converter on the Input Power System Quality,” IEEE Trans. Power Electron., vol.25, no.6, pp. 1450-1459 (Jun. 2010).

- A. M. Stankovic, G. C. Verghese, and D. J. Perreault, “Analysis and Synthesis of Randomized Modulation Schemes for Power Converters,” IEEE Trans. Power Electron, vol. 10, no. 6, pp. 680–693 (Nov. 1995).

- K. K. Tse, H. S. Chung, S. Y. Hui, and H. C. So, “Analysis and Spectral Characteristics of a Spread-Spectrum Technique for Conducted EMI Suppression,” IEEE Trans. Power Electron., vol.15, no.2, pp. 399-410 (Mar. 2000).

- H. Giral, E. A. Aroudi, L. Martinez-Salamero, R. Leyva, and J. Maixe, “Current Control Technique for Improving EMC in Power Converters,” Electron. Lett., vol.37, no.5 (Mar. 2001).

- B. Yuan, C. Liang, Z. Li and Q. Zhang, “A Clock Generator with Dual Pseudo Random Spread Spectrum in DC-DC Buck Converter,” IEEE International Conference on Integrated Circuits, Technologies and Applications (ICTA), Hangzhou, China, pp. 2024.

- F. Mihali, and D. Kos, “Reduced Conductive EMI in Switched-mode DC–DC Power Converters without EMI Filters: PWM versus Randomized PWM,” IEEE Trans. Power Electron, vol.21, no.6, pp. 1783-1794 (Nov. 2006).

- H. Li, W. K. S. Tang, Z. Li, and W. A. Halang, “A Chaotic Peak Current Mode Boost Converter for EMI Reduction and Ripple Suppression,” IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II: Exp. Briefs, vol.55, no.8, pp. 763-767 (Aug. 2008).

- Y. -H. Kao et al., “8.11 A 48V-to-5V Buck Converter with Triple EMI Suppression Circuit Meeting CISPR 25 Automotive Standards,” IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference (ISSCC), pp. 164-166, San Francisco, CA, USA (Feb. 2024).

- M. Fishta, E. Raviola and F. Fiori, “EMI Reduction at the Source in WBG Inverters: A Comparative Study of Spread-Spectrum Modulation and Auxiliary Switching Leg Techniques,” IEEE Transactions on Electromagnetic Compatibility, vol. 66, no. 5, pp. 1412-1419 (Oct. 2024).

- E. Stok, M. Otten, H. Huisman and Y. Kösesoy, “EMI Reduction in an Interleaved Buck Converter Through Spread Spectrum Frequency Modulation,” 25th European Conference on Power Electronics and Applications (EPE’23 ECCE Europe), pp. 1-11, Aalborg, Denmark (2023).

- T. -W. Sun, M. -Z. Li, T. -H. Tsai and C. -C. Chang, “A High-Accuracy Hysteretic DC-DC Converter Using A Spread-Spectrum EMI Suppression Technique with Double Gold Codes,” 21st IEEE Interregional NEWCAS Conference (NEWCAS), pp. 1-4, Edinburgh, United Kingdom (2023).

- A. Barbaro, M. Fishta, E. Raviola and F. Fiori, “A Comparison of Spread Spectrum and Sigma Delta Modulations to Mitigate Conducted EMI in GaN-Based DC-DC Converters,” 14th International Workshop on the Electromagnetic Compatibility of Integrated Circuits (EMC Compo), pp. 1-6, Torino, Italy (2024).

- J. Kundrata and A. Baric, “Clock Frequency Optimization of a Compensated Spread-Spectrum Controller in Buck Converters,” IEEE Access, vol. 12, pp. 4881.

- S. Kapat, “Reconfigurable Periodic Bi-frequency DPWM with Custom Harmonic Reduction in DC-DC Converters,” IEEE Trans. Power Electron, vol.31, no.4, (Apr. 2016).

- J. Kundrata and A. Barić, “Implementation of Voltage Regulation in a Spread-Spectrum-Clocked Buck Converter,” 46th MIPRO ICT and Electronics Convention (MIPRO), pp. 253-258, Opatija, Croatia (2023).

- N. Miki, N. Tsukiji, K. Asaishi, Y. Kobori, N. Takai, H. Kobayashi, “EMI Reduction Technique With Noise Spread Spectrum Using Swept Frequency Modulation for Hysteretic DC-DC Converters,” IEEE International Symposium on Intelligent Signal Processing and Communication Systems (ISPACS), Xiamen, China (Nov. 6-9, 2017).

- N. Oiwa, S. Sakurai, Y. Sun, M. T. Tri, J. Li, Y. Kobori, H. Kobayashi, “EMI Noise Reduction for PFC Converter with Improved Efficiency and High Frequency Clock,” IEEE 14th International Conference on Solid-State and Integrated Circuit Technology, Qingdao, China (Nov. 2018.

- Y. Kobori, Y. Sun, M. T. Tri, A. Kuwana, H. Kobayashi, “EMI Reduction in Switching Converters With Pseudo Random Analog Noise,” Journal of Technology and Social Science, Vol.4, No.2, pp.33-48 (20). 20 April.

- Y. Kobori, T. Arafune, N. Tsukiji, H. Kobayashi, “Selectable Notch Frequencies of EMI Spread Spectrum Using Pulse Modulation in Switching Converter,” IEEE 11th International Conference on ASIC, no.16158097, B8-8, Chengdu, China (Nov. 2015).

- Y. Sun, Y. Kobori, H. Kobayashi, “Full Automatic Notch Generation in Noise Spectrum of Pulse Coding Controlled Switching Converter,” IEEE 14th International Conference on Solid-State and Integrated Circuit Technology, Qingdao, China (Nov. 2018.

- Y. Sun, Y. Kobori, A. Kuwana, H. Kobayashi, “Pulse Coding Controlled Switching Converter that Generates Notch Frequency to Suit Noise Spectrum,” IEICE Trans. Communications, Vol.E103-B, No.11, pp.1331-1340 (Nov. 2020).

- G. Dong, S. Katayama, Y. Sun, Y. Kobori, A. Kuwana, H. Kobayashi, “Notch Frequency Generation Methods in Noise Spread Spectrum for Pulse Coding Switching DC-DC Converter,” 13th Latin American Symposium on Circuits and Systems, Santiago, Chile (Mar. 2022).

- A. T. L. Lee, W. Jin, S.-C. Tan, and R. S. Y. Hui, Single-Inductor Multiple-Output Converters: Topologies, Implementation, and Applications, CRC Press; 1st edition (Dec. 2021).

- B. Rooholahi, Y. P. Siwakoti, H. -G. Eckel, F. Blaabjerg and A. S. Bahman, “Enhanced Single-Inductor Single-Input Dual-Output DC–DC Converter With Voltage Balancing Capability,” IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, vol. 71, no. 7, pp. 7241-7251, (24). 20 July.

- X. Zhang, A. Zhao, X. Li, Y. Jiang, R. P. Martins and P. -I. Mak, “An 80W Single-Inductor DC-DC Architecture for Simultaneous Flash Charging and Dual-Output PoL Supply with 92.1% Peak Efficiency from 15V-to-28V Input to 12.6V/3.3V/1V Outputs Using 1.3 mm3 Inductor,” IEEE European Solid-State Electronics Research Conference (ESSERC), Bruges, Belgium, pp. 61-64 (2024).

- W. -T. Yeh, M. -X. Cai, C. -W. Tsai and C. -H. Tsai, “A Single-Inductor Bipolar-Output DC-DC Converter With Tunable Asymmetric Power Distribution Control (APDC) for AMOLED Applications,” IEEE Access, vol. 13, pp. 6810-6819 (2025).

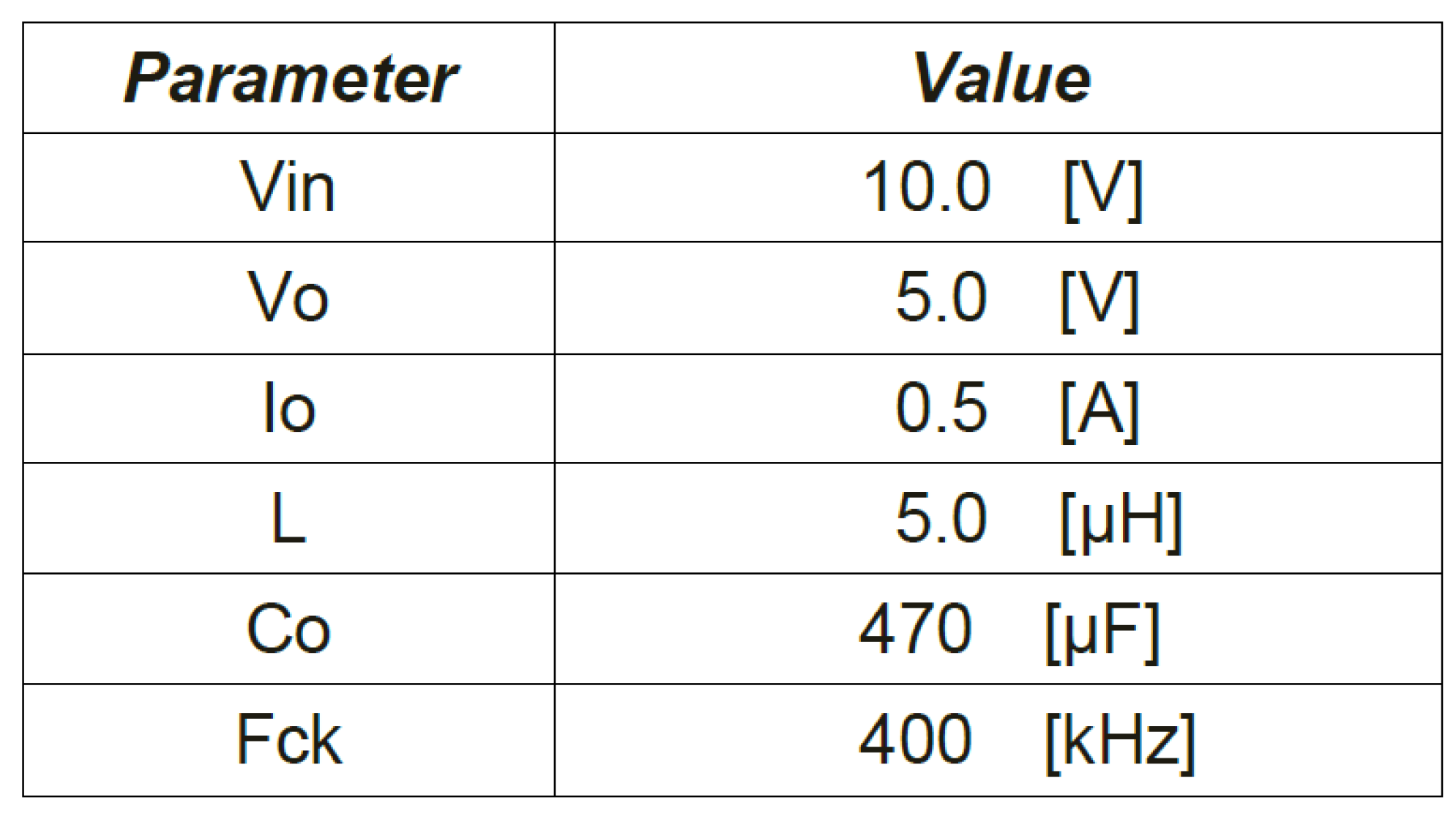

| 12V | 5V | 0.52A | 200 |

| 470 | 2.0s | 1.6s | 0.3s |

| 10V | 3V | 0.5A | 100 |

| 470 | 170ns | 600ns | 220ns |

| 12V | 5V | 0.2A |

| 100 | 47 | 500kHz |

| 10V | 3.5V | 0.16A |

| 141 | 570 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).