1. Introduction

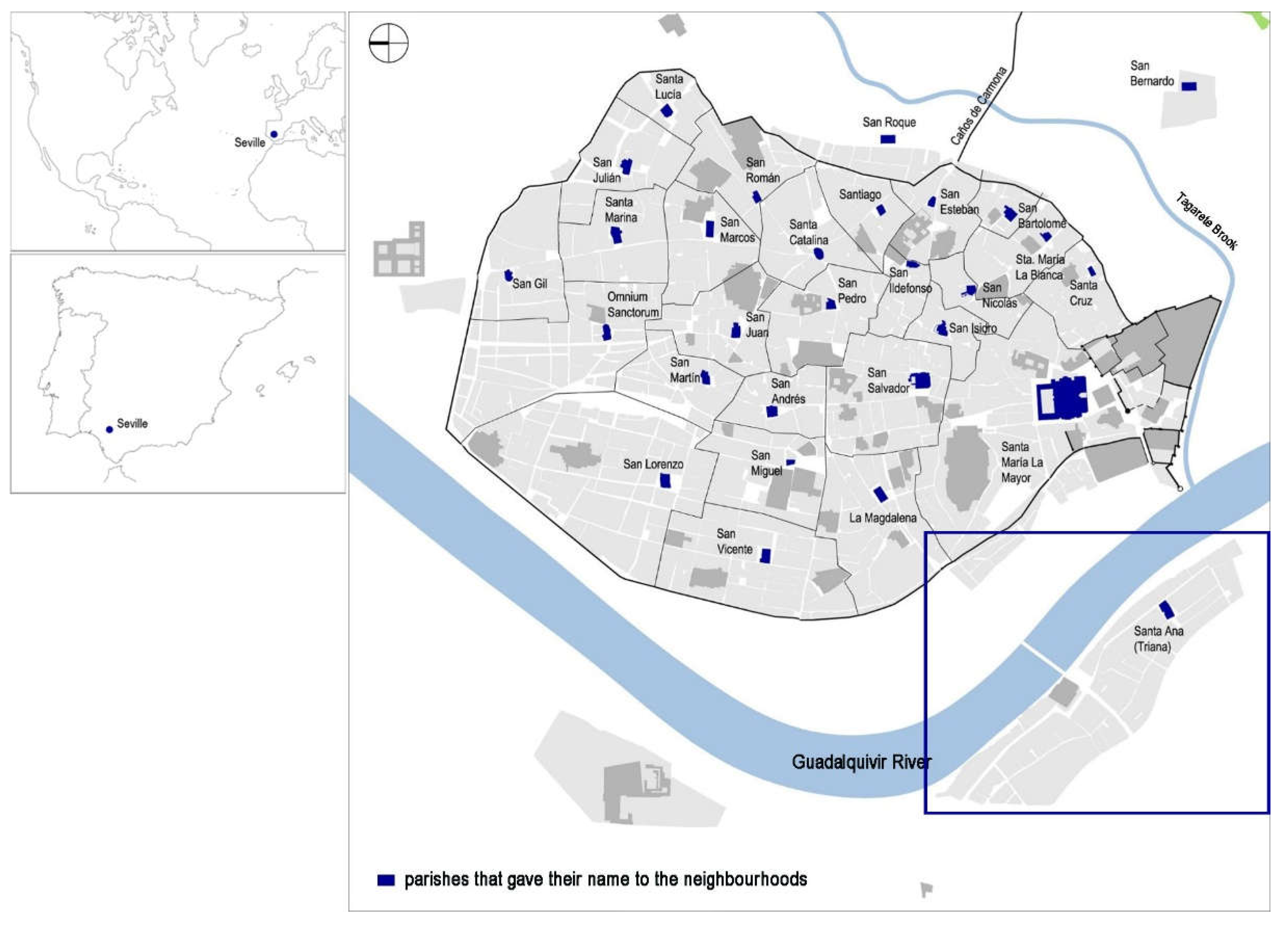

1.1. About Seville

To understand urban planning on the Iberian Peninsula in the early Modern Age, it is essential to analyse two fundamental architectural and structural elements: the wall and the church. These components, although inherited from the medieval tradition, were merged from the first moments of the Christian repopulation, and played a crucial role in the organization of urban settlements. Walls not only provided protection but also helped to structure urban space, while churches acted as centres of social and territorial organization. Together, they defined the growth of cities over time [

1]. But in a brief period, the process of consolidation of urban space would lead to the construction of buildings and the creation of new urban spaces, which, when integrated into an increasingly complex network, became essential landmarks for the development of urban centres. This phenomenon of urban expansion and stratification took place in many peninsular and American cities, contributing to their definitive transformation [

2].

The city of Seville was certainly special, as it played a fundamental role in the urban and commercial context of the peninsula. Its importance was merged from 1503 onwards, when the

Casa de Contratación –House of Trade– was created, which centralized trade and the administration of routes to the new overseas territories. This merged Seville as the so-called Port of the Indies and as the main centre of trade with America during the 16th and 17th centuries. Its strategic location, on the banks of a navigable river, the Guadalquivir, eased the arrival of ships from the Atlantic and the distribution of goods to the interior of the peninsula. In addition, the security provided by its position some kilometres inland protected it from pirate attacks. This, together with an ever-growing port infrastructure and the establishment of the

Casa de Contratación, made Seville the main centre for economic transactions between Spain and America (

Figure 1).

However, despite its growing importance in transatlantic trade, Seville kept the same organizational structure that characterized most of the cities on the peninsula: an urban layout centred around its walls and religious temples. The urban morphology of the city was characterized by small buildings, with narrow façades and a notable depth, organized contiguously around the main temples. This urban planning model favoured the creation of densely populated neighbourhoods within the walled enclosure, while the peripheral areas and suburbs, although less compact, also underwent a process of densification in which the centrality of the religious temples was reproduced, albeit with more marked differences and the incorporation of open spaces. It should also be borne in mind that the historical evolution of Seville was strongly influenced by its Islamic heritage, which was reflected in a more irregular and complex urban configuration than in other cities with a more planned development (

Figure 2).

1.2. About Triana

Although Seville concentrated all the administration of overseas trade, the real core of port activities was in Triana. This quarter, whose occupation dates to the Islamic period, was strategically found next to a fortress and one of the main access routes to the city (Díaz Garrido, 2010). Over time, Triana evolved from a dispersed suburb to a merged neighbourhood with a well-defined identity. During the 15th century, Triana was already a

puebla –village– with its own church [

3], and its population grew significantly, which favoured the structuring of a more organized urban fabric. The streets of the district, initially laid out in a linear pattern parallel to the river, expanded progressively, giving rise to a dynamic urban nucleus with significant commercial activity. By the 15th century, Triana was merged as a fundamental enclave within the city, the

collación –quarter– of Santa Ana de Triana [

4] (

Figure 3).

This study focuses on the analysis of 16th century Seville, through the research of historical sources, with the aim of deepening our knowledge of Triana, one of the richest and most densely populated neighbourhoods in the city. The aim is to answer key questions such as what the collación of Triana was like, who were the inhabitants, and what were the characteristics of their dwellings.

The proposed work aims to offer a comprehensive view of the urban, social, and architectural development of Triana in the Modern Age, highlighting its role within the socio-economic structure of Seville and its relevance in Atlantic trade.

2. State of Art

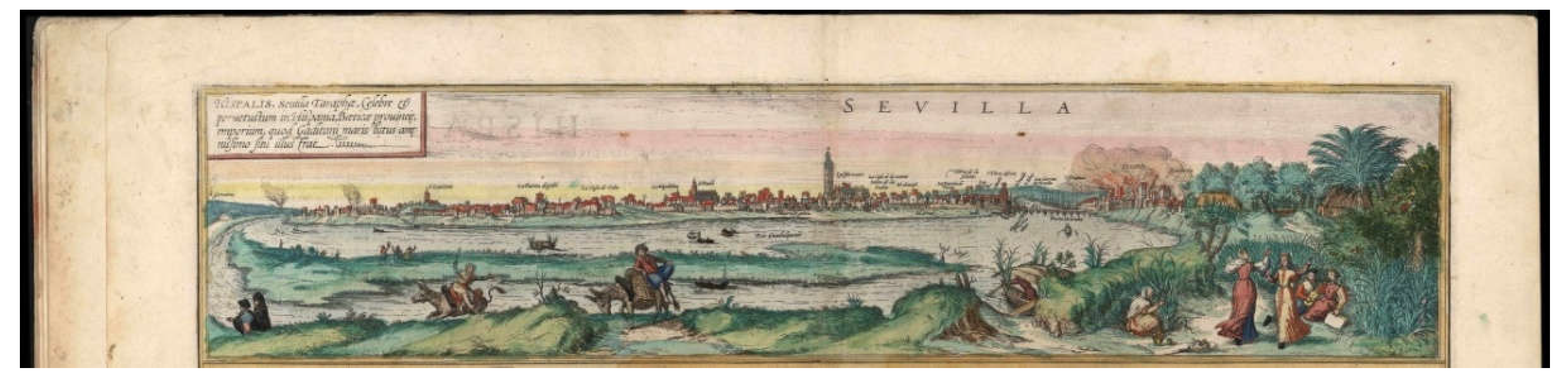

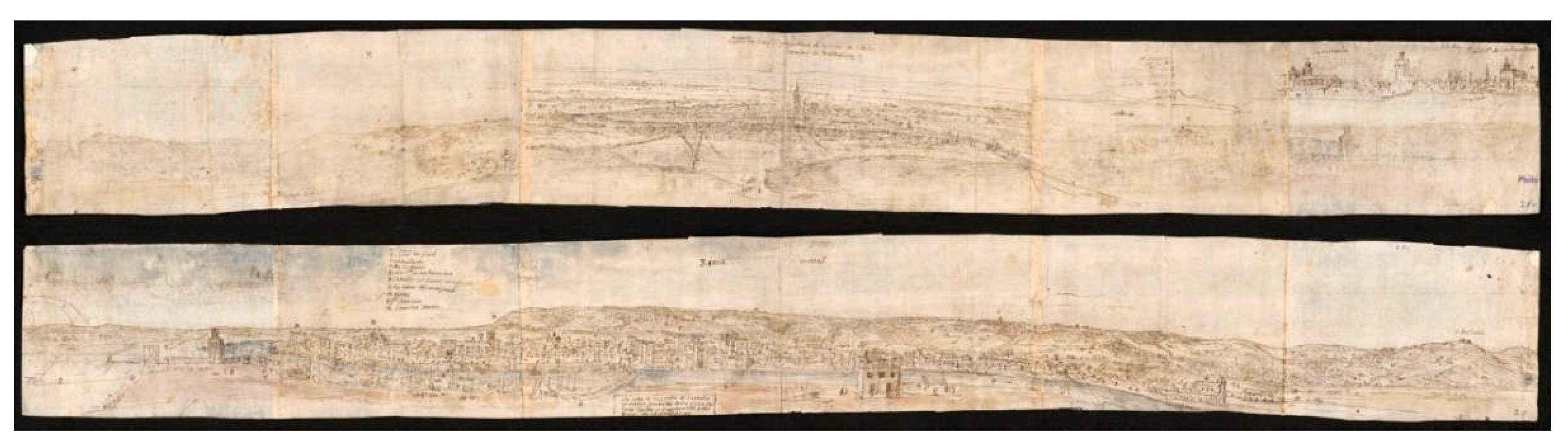

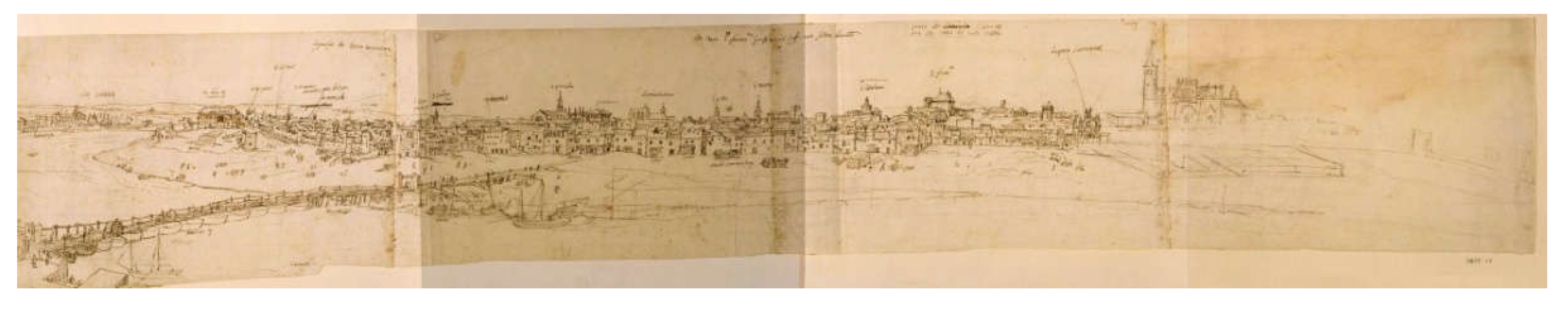

About the images for the study of the urban planning of Seville and Triana in the 16th century, it is more than significant that from 1560 onwards, a production of graphic representations of the city began, mostly of a naturalistic nature, which marked a milestone in the history of Sevillian urban iconography. Except for the models of the main altarpiece of the cathedral, these representations are the first of the city and are fundamental visual documents for understanding the evolution of Seville’s urban landscape. Among the most outstanding works of this period are the panoramic views produced by artists such as Joris Hoefnagel (

Figure 4) and Anton Van der Wyngaerde (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6), who capture the city in a precise manner, drawn from life. These depictions not only offer a detailed view of the urban setting, but also give special prominence to Triana, a notable aspect that is particularly prominent in Wyngaerden’s views. This is exceptional within the tradition of Sevillian iconography, as it shows Triana with a singular attention that is not seen in other depictions of the period, underlining the importance of the neighbourhood in the context of the city.

Another representative example of this graphic tradition is the print by Brambilla (

Figure 7), produced in 1585, which presents a general panorama of Seville from the west, with Triana in the foreground. This type of representation, which would be replicated on many occasions, is characterized by an approach which, while supporting an overall view, introduces a degree of abstraction and simplification with respect to the real city, allowing for a more stylized and symbolic interpretation of the urban landscape.

These views are not only valuable as visual documents, but also as a means of exploring how artists of the time perceived and presented the urban development of Seville, with a particular focus on Triana. Their contribution to the study of the city in the 16th century is essential, as they offer a graphic perspective that complements other types of historical records and allows for a deeper understanding of the evolution of urban spaces, their organization and the relationship between the different neighbourhoods and the Guadalquivir River.

Also, among the main bibliographical sources for the study of urban representation in the 16th century, works such as

La representación de la ciudad en el Renacimiento by Arévalo Rodríguez [

5] or

La imagen de la ciudad en la Edad Moderna edited by Cámara Muñoz and Gómez López [

6] stand out. In addition,

Ciudades del siglo de oro: Las vistas españolas de Anton van den Wyngaerde edited by Kagan [

7], together with the facsimile editions of

Civitates Orbis Terrarum by Max Schefold [

8] and Skelton [

9], are essential references. For the Sevillian context, the work of Díaz Zamudio and Gámiz Gordo on Sevilla [

10] is fundamental and complements this perspective. Finally,

Iconografía de Sevilla. 1400-1650 by Cabra Loredo and Santiago Páez [

11], which brings together many views of Seville.

The systematic analysis of Seville’s periphery was first addressed in

Sevilla extramuros. La huella de la historia en el sector oriental de la ciudad, edited by Valor Piechotta and Romero Moragas [

12]. Other relevant studies on 16th century Seville include

Historia de Sevilla. La ciudad del Quinientos by Morales Padrón [

13], and

El urbanismo de Sevilla durante el reinado de Felipe II by Albardonedo Freire [

14].

Likewise, the study of the city’s urban and rural infrastructures is complemented by works such as

La obra hidráulica en la cuenca baja del Guadalquivir by Moral Ituarte [

15]. About fortifications, the

Estudio histórico-arqueológico de las puertas medievales y postmedievales de las murallas de la ciudad de Sevilla by Jiménez Maqueda [

16] provides a detailed analysis. In relation to the religious buildings found outside the city walls,

Patrimonio y ciudad. El sistema de los conventos de clausura en el centro histórico de Sevilla by Pérez Cano [

17] offers a complete perspective. On the other hand,

Los hospitales de Sevilla by Chueca Goitia et al. [

18] focuses on the hospital institutions of the 16th century. Finally, the study of the rural landscape of Seville is found in

El paisaje rural sevillano en la Baja Edad Media by Montes Romero-Camacho [

19].

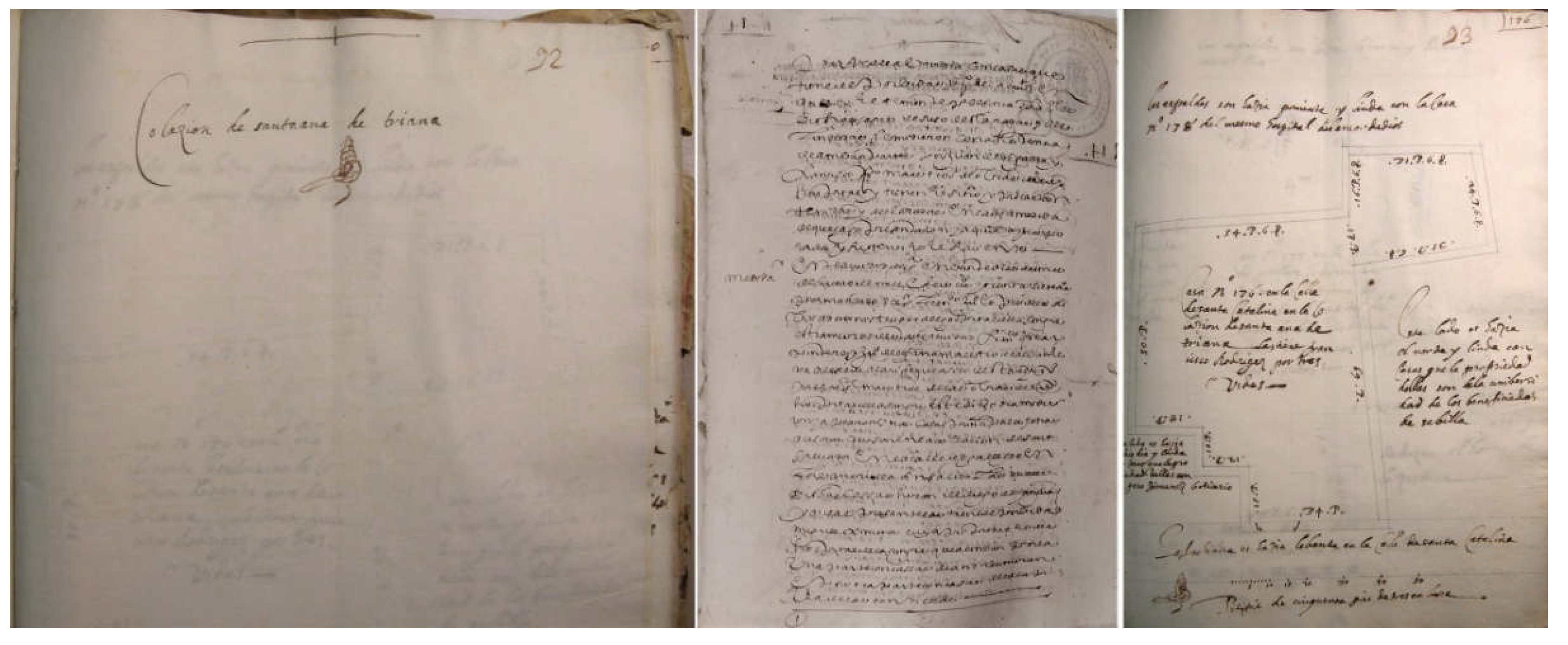

For the analysis of the dwelling and urban structure of Seville and Triana, various documentary sources were consulted, including archives such as the Archivo de la Catedral de Sevilla –Seville Cathedral Archive– (ACS), the Archivo de la Diputación Provincial de Sevilla –Provincial Council Archive of Seville– (ADPSE), and the Archivo Histórico Provincial de Sevilla Protocolos Notariales –Provincial Historical Archive of Seville Notarial Protocols– (AHPSPN).

Particularly noteworthy are the house surveys and plot plans, which provide information on tenants, trades, dimensions, and construction characteristics of the properties. Approximately 1700 records have been reviewed, including descriptions of houses belonging to the cathedral and to the hospitals of Las Bubas, El Cardenal, and Las Cinco Llagas (16th century surveys), as well as of the hospitals reduced (beginning of the 17th century) many drawn up by Vermondo Resta. In addition, 220 surveys of the Hospital de la Misericordia (17th century) have been included, allowing the identification of 44 properties in the collación of Triana.

Apart from this documentation, chronicles, and publications such as

Curiosidades antiguas sevillanas by Gestoso Pérez [

20],

Curiosidades sevillanas by Álvarez Benavides [

21],

Triana de puente a puente (1147-1853) by Acosta Domínguez [

22] and

Triana: el caserío. Calles, plazas, sitios y lugares by Macías Míguez [

23], the latter based on the population lists of neighbours from the 15th century to the 19th century.

Finally, the academic research of Díaz Garrido [

24], whose thesis

Triana y la orilla derecha del Guadalquivir was awarded the Focus-Abengoa prize in 2005, stands out. Her study on the residential typology of the

corral de vecinos –a traditional Spanish communal housing– in Triana and her coordination of the

Aula Digital de la Ciudad have been fundamental to understanding the urban evolution of the neighbourhood.

3. Historical and Urban Context of Triana

The historical development of Triana is articulated through several stages, beginning with its Islamic origins, where it appeared as a suburb linked to Seville. This first phase of Triana’s history laid the foundations for its later growth, making it a strategic and significant point in the city’s urban history. During the Islamic period, Triana was already intricately linked to the Guadalquivir River, which defined its geographical and economic importance. This relationship with the river lasted throughout its evolution, being fundamental for the commercial and industrial activity of the neighbourhood, which would be consolidated in later stages.

The late medieval period, which lasted from the Christian conquest until the end of the 15th century, was crucial in the formation of the arrabal –suburb– of Triana. During this period, Triana underwent a remarkable transformation. Its status as a suburb was strengthened, and it gradually developed into an urban centre with its own identity, even known as ‘guarda y collación de Sevilla’ –guard and quarter of Seville–. The district began to get importance not only as a place of residence, but also as a commercial and productive centre, which served as a bridge between Seville and the overseas territories. Throughout this period, Triana was a centre of artisan, agricultural and industrial activity, with a population that depended on activities related to the river, agriculture, and trade.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, Triana experienced its heyday, especially driven by the discovery of America and the boom in trade in the Indies. According to Morgado [

25], at the end of the 16th century Triana was: ‘a warehouse for all the tar, nails, oars and all the rigging for navigation’, which underlines the importance of maritime activity in the neighbourhood. This testimony not only highlights the importance of Triana in the maritime and commercial context, but also reflects the fundamental role played by sailors, captains, and masters, who settled in the area due to the opportunities offered by the boom in traffic to the Indies. This relationship with the sea also materialized in local industry, such as the production of gunpowder,

bizcocho –biscuit– (essential food for the crews) and ceramics, products that were mostly destined for trade with America [

26] (

Figure 8).

Triana’s industry and economy were essential factors in its growth. The neighbourhood was not only a centre of production, but also a strategic node in the trade to America. Numerous sailors, masters and commissaries settled in Triana and played a crucial role in the expeditions to the New World. In 1569, the Universidad de Mareantes –University of the Men of the Sea– heir to the medieval Colegio de los Comitres –School of the Shipmen–, was founded as a reference point for seafaring professionals. This university brought together the sailors, masters, and pilots who formed part of the structure of the maritime trade to the Indies. The creation of the Casa de la Contratación and its relationship with Triana, as the nerve centre of maritime activity, further reinforced the importance of this neighbourhood in the dynamics of the expeditions.

In addition to its role in maritime activity, Triana stood out for its access to the river, which eased communications and trade. The Pontoon Bridge provided a vital connection with the city of Seville, being essential for the flow of goods and people between both sides of the Guadalquivir. This interconnection with the city was complemented by a network of roads that connected Triana with nearby towns such as Camas, Itálica and Huelva, which favoured the transport of goods and the mobility of the population [

27] (

Figure 9).

The demographic growth of Triana, a direct consequence of its economic prosperity, was consolidated during this period. By the end of the 16th century, the population of the neighbourhood reached 4,000 –equivalent to 20,000 inhabitants–. This increase was accompanied by a construction boom, with 2,454 new houses built in Seville, of which more than 900 were in Triana [

28].

The urban configuration of Triana also revealed an interesting complexity. The presence of defensive elements such as the

cava –a moat of Almohad origin– and the wall that extended to the west, marked a clear distinction between the neighbourhood and the walled city of Seville. In addition, its urban fabric was made up of houses, corrals, inns, and shops, which were distributed in places such as the Altozano and Santo Domingo, areas of great commercial importance. In this environment, local industries developed, such as the production of soap, ceramics, and gunpowder, which contributed to the economy not only of Triana, but of Seville as a whole [

29,

30] (

Figure 10).

Another important aspect of Triana in the Modern Age was the constant interaction with other communities, especially the Portuguese, who played a fundamental role in maritime activity. As Morales Padrón [

13] points out, the Portuguese presence in Triana was considerable, and the collaboration between sailors from both crowns, Castilian, and Portuguese, was crucial in the Atlantic expansion and navigation to the Indies. The commercial and maritime ties between the two territories were particularly close, especially in the 16th and 17th centuries, and contributed to Triana becoming one of the most important seafaring districts on the peninsula.

Urban expansion was also influenced by the arrival of other new inhabitants, including the Moors who, after being banished from Granada by Philip II, settled in Seville, especially in Triana. It is estimated that by the end of the 16th century the Moorish population of Seville reached 7,000 people, many of whom lived in Triana. This integration of the Moors, together with the presence of a diverse population, had a considerable influence on the social and cultural configuration of the neighbourhood.

This urban and social panorama of Triana, marked by its links with trade, industry, the sea, and the routes to America, reflected an interdependence of elements that contributed to its consolidation as a key neighbourhood in the history of Seville during the Modern Age.

4. Neighbours: Occupations and Backgrounds

As has been seen since the late Middle Ages, the population of Triana has been distinguished by its remarkable diversity of trades, which reflects the economic and social structure of the neighbourhood. According to historians,

Trianeros were engaged in activities linked to the sea, agriculture, and industry. Among the most recurrent trades were sailors, who played a fundamental role in maritime traffic to the Indies, as well as builders and craftsmen, who were essential to produce elements necessary for navigation and daily life. In fact, Triana was a centre for the manufacture of items such as pottery, soap, gunpowder and biscuit, products that were closely related to the expeditions and trade to America. In addition, the area surrounding the neighbourhood, rich in market gardens, allowed agriculture to flourish, with the production of oil and wine, activities that were fundamental for the supply of the city and foreign trade [

27].

Along with these trades, the population of Triana was also made up of sweepers, potters and other craftsmen who carried out work related to local production and trade. These trades were essential for the supply of basic products and the creation of utensils used in everyday life. In addition to these workers, Triana also housed servants, people dedicated to various domestic and support tasks, as well as professionals from different fields, such as doctors, apothecaries, and clergymen [

13]. The latter constituted an important part of the community, as they played significant roles in both the religious life and public health of the neighbourhood (

Figure 11).

The analysis of the documents of the surveys, which described the properties and the conditions of the tenants, confirms the variety of professions in the neighbourhood. In these texts, the occupation or social status of the neighbours is often mentioned, which allows us to see a wide range of trades, from the humblest to the most prestigious. Among the tenants recorded are potters, labourers, sailors, and merchants, highlighting the economic versatility and the importance of manual and commercial work in the development of the neighbourhood. Married couples, widows, and a considerable number of married women, who were an active part of the community, also stand out. It is interesting to note the presence of a Portuguese among the Neighbours, which is consistent with the research of Quiles García et al. [

31], who underlines the significant Portuguese influence in Triana during the 16th century, especially in the maritime sphere.

The surveys also mention other professions that formed part of everyday life in Triana. Among the neighbours, the following trades are documented: atahonero –mill worker–, apothecary, ship’s captain, clergyman, doctor, farrier, ship’s master, pilot, merchant, and an oil merchant, which once again shows the diversity of economic activities and the social plurality that coexisted in the neighbourhood. This professional diversity and the presence of people of different origins and social status constitute one of the most defining characteristics of Triana currently, reflecting its complexity as a meeting place for diverse social, ethnic, and economic groups.

This panorama of diversity in the social composition of Triana highlights how the neighbourhood was not only a hub of economic activity, but also a space where diverse cultures and social groups coexisted. The coexistence of sailors, artisans, merchants, and workers of different trades, together with the influence of foreign populations, contributed to giving Triana its unique character within 16th-century Seville. This complex social structure allowed the neighbourhood to become a vibrant centre of production, trade, and culture, merging itself as a fundamental pillar of the city in the context of the economic boom linked to trade with the Indies.

5. The Houses of Triana: Structure, Uses, and Distribution

The studies on the dwellings of Triana, based on 44 surveys analysed, show a notable variety in the types of constructions that predominated in this Sevillian neighbourhood. Most of the buildings were residential in character, although some different uses were also documented, such as a corral that served as a garden, a

corral de vecinos, and a shop. To better understand these spaces, we have integrated data from other publications and chronicles that show the houses and neighbouring corrals as the most common architectural typologies in Triana. These corrals and dwellings were not only residential, but also an integral part of a way of life that, due to their proximity to the city, was linked to commercial and service activities. In addition, the presence of inns suggests that Triana, being a neighbourhood outside the city walls and at the confluence of several roads, was a place of transit and rest, which favoured the establishment of this type of establishment (

Figure 12).

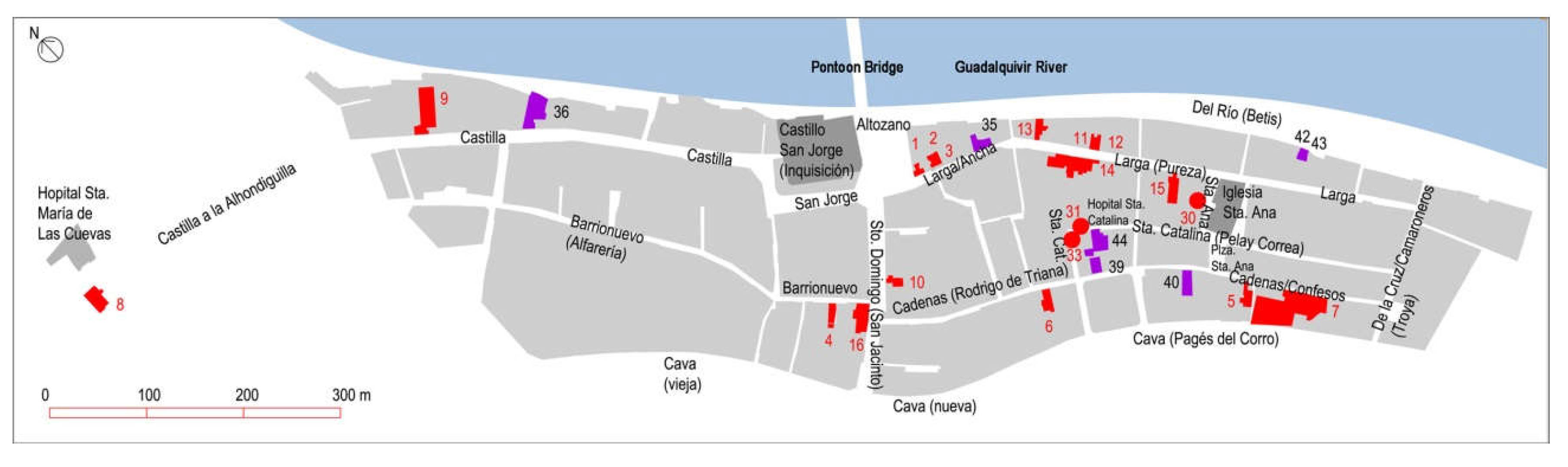

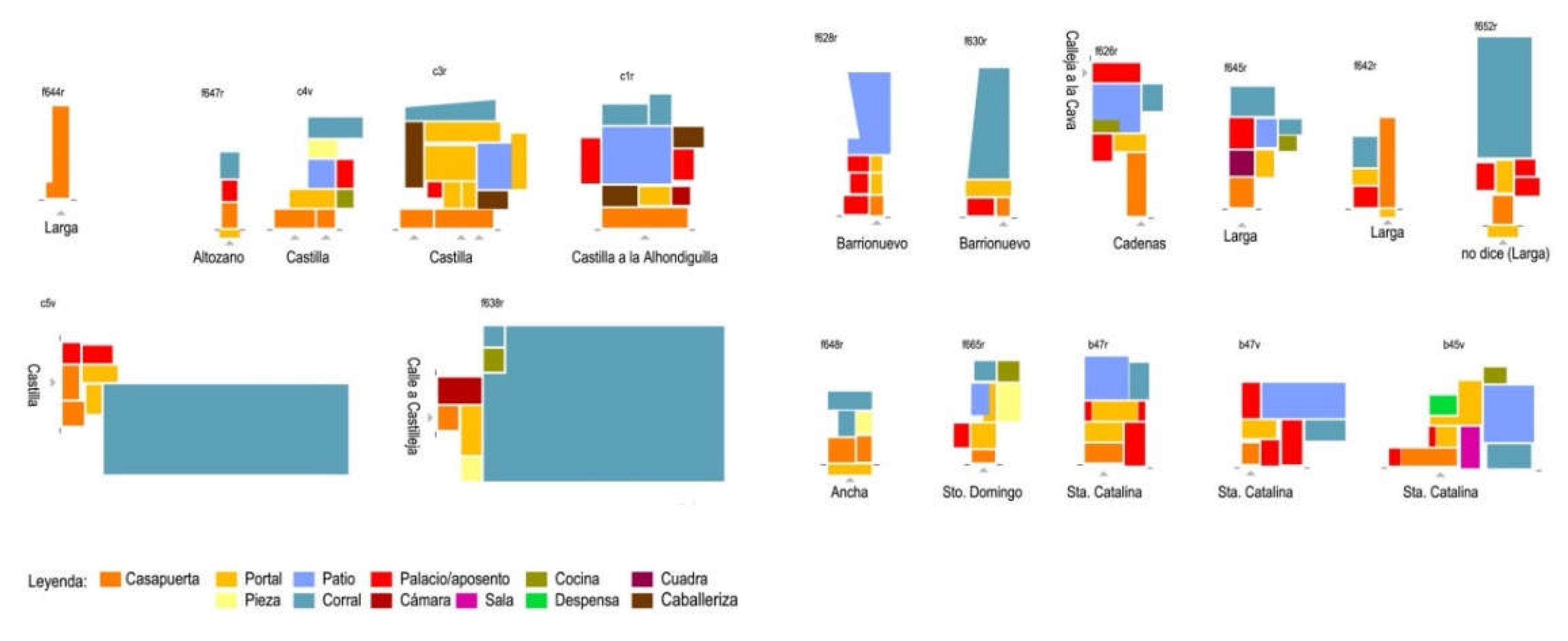

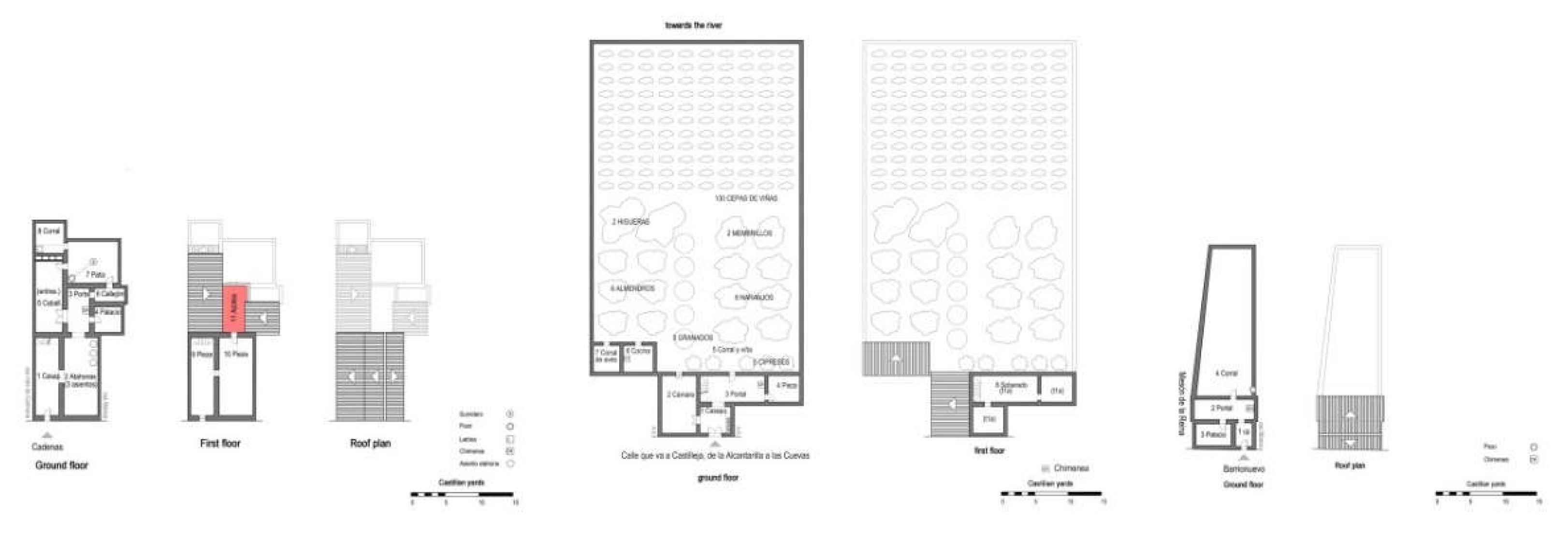

The analysis of the Triana dwellings is based on 33 literary and 11 graphic surveys (

Figure 13 and

Figure 14), which offer a detailed view of the surface area and distribution of the houses. The literary surveys use Castilian yards –0.8359 m– to measure the width and length of the spaces, allowing the surface area of each room on the ground floor to be calculated. Once these measurements were obtained, the occupied area of the plots was estimated by adding 10% to the total surface area of the dwellings to have a more exact approximation. The graphic surveys also provided a visual scale, which allowed the exact conversion of the measurements to square meters using a CAD program [

32].

5.1. Architectural Drawing and Analysis

In addition, using our own drawing methodology, already used in previous research, 18 of the 19 dwellings analysed were drawn. Thanks to these surveys and graphic drawings of the houses, the typology of the Triana neighbourhood in the 16th and 17th centuries has been studied.

The method used to draw the houses described in the survey plans consisted of formulating hypotheses on the ground plan. This helped to understand the construction and its later architectural analysis, by ‘translating the written and graphic into the digital’. This process is distributed as follows:

Transcription of the surveys

Compilation of the information for a better use and selection of the data necessary for the knowledge of the architecture, construction, and elaboration of the drawing hypotheses

Drawing of the spatial structures in CAD and architectural graphic analysis

After the analysis, conclusions are drawn that cover the most frequent volumes and the relationship of the buildings with the street, such as the distributions, the uses of the spaces and their surfaces, as well as the most recurrent types of construction and the installations inside them.

Analysis of the data obtained from these surveys revealed that the average surface area of housing plots in Triana was around 200 square meters, which is higher than the average for Seville, which was approximately 160 square meters [

33]. This suggests that, compared to other areas of the city, Triana offered more spacious dwellings, which is consistent with the demand and commercial character of the neighbourhood.

In terms of the number of floors, most of the houses in Triana were not very tall. Single-floor dwellings predominated, although some exceptions were documented in the areas near the Altozano or Ancha Streets, which were areas with greater commercial activity. Some dwellings of greater surface area and construction quality were also found, which had more than one floor. In all cases, with one exception, the dwellings had a courtyard or a corral, or even both. These open-air spaces were essential for Triana dwellings and stood for a characteristic element of the architecture of the neighbourhood.

Among the most common elements in Triana dwellings were casapuerta –vestibule–doorways, kitchens, and courtyard. Compared to the Seville average, Triana had a greater number of doorways, suggesting that the dwellings had multiple passageways that could have other uses. The kitchen, on the other hand, was present in almost 40% of Triana dwellings, compared to 25% in the rest of the city, which could show a difference in the habits and needs of the neighbourhood’s population. In many cases, the houses that did not have a proper kitchen had a space in the casapuerta, the doorway or the courtyard, where a fireplace was placed, or a cooker was installed for the preparation of food.

The living spaces in Triana’s houses were the so-called ‘palaces’ or living and sleeping quarters. The average number of these spaces was two per dwelling, which coincided with the general pattern in the city. However, given that many of the houses did not have

soberados –additional spaces on the upper floor–, it is possible that the Triana dwellings had a smaller area devoted to rooms compared to the rest of Seville. It is important to note, however, that the courtyards and corrals were fundamental elements in the structure of Triana’s dwellings. In fact, corrals, with larger surfaces than courtyards, were more common than in other areas of the city [

33] (

Figure 15).

In terms of facilities, Triana dwellings did not always have a well, unlike in other parts of Seville, where this resource was more common. Only 70% of the dwellings analysed had one, which could be due to the proximity to the Guadalquivir River or to an alternative supply system not yet detailed in the documents. For water drainage, some dwellings were equipped with drains, and for sanitation, latrines were used.

To better illustrate the diversity of typologies and uses, three representative dwellings were selected: a house with three

atahona –stone mill– seats, a house with a large orchard and vineyards, and the house of a widow –a cook in a nearby inn–. This variety of uses and configurations proves how, in Triana, the dwellings, and especially the neighbours’ corrals, not only fulfilled residential functions, but also commercial and service functions. This trend continued even into the 20th century, when the corrales de vecinos continued to share spaces with industrial and commercial activities [

34] (

Figure 16).

6. Other Forms of Inhabitation: Corrales de Vecinos, Mesones, and Posadas

6.1. Corrales de VECINOS

The corrales de vecinos were a residential typology characterized by the construction of dwellings on interior plots, which often occupied vegetable gardens or courtyards –called

compases in Seville–. In most cases, these dwellings were organised with a corridor of rooms attached to the boundaries of the plot. This type of dwelling was extensively documented for the whole of Seville in the 16th century, with 27 corrales in total, of which two were in Triana [

35]. However, for this study, the period of research was extended, using various documentary sources and notarial protocols that allowed the discovery of two more corrales in the 17th century, broadening the vision of this form of dwelling.

During the 18th century, the proliferation of corrales was remarkable, and their study has become a field of interest for many historians, among whom Macías Míguez [

29] and Morales Padrón [

13] stand out. The latter focused his attention on the gradual disappearance of the corrales in the 20th century, a phenomenon that had already been pointed out by other authors. In addition, the research by Fernández Salinas [

34] on the historical heritage of Seville and the work carried out by Díaz Garrido and her team at the

Aula Digital de la Ciudad [

36] have contributed significantly to the knowledge of this typology. In their research, they documented 30 corrales that were still preserved in 2010 in various streets of Triana, such as Alfarería, Arcilla, Bernardo Guerra, Betis, Castilla, Covadonga, Pagés del Corro, Pureza, Salado, San Jacinto, and San Jorge.

The analysis of the corrales in the 16th and 17th centuries reveals a diverse distribution in their location. However, no clear conclusion can be drawn about the most common locations of corrals because they were not a widespread residential typology at the time. The available data suggest that the corrales were concentrated in the streets Castilla, San Jacinto –also known as Santo Domingo–, and Pagés del Corro – known la Cava–. Among these, the Corral de La Parra, found in San Jacinto, stands out especially, as it stayed in operation until 1880, having been founded in the 16th century.

The corrales functioned around the central courtyard. In general, the men worked outside the dwelling, while the women and children remained in the courtyard. They usually had a kitchen equipped with a fireplace, a water well –later replaced by a tap–, a washing place –with a basin– and a latrine. This living configuration remained unchanged until well into the 20th century, with the gradual incorporation of more modern technologies, but without significantly altering the spatial and constructional structure of the corrals.

During the 18th century, the corrales and the

casas de vecindad –a similar name given– underwent a significant expansion. Some of the area’s most densely occupied by these housing spaces were the streets Pagés del Corro (la Cava), Alfarería (Barrionuevo), Castilla, Pelay Correa (Santa Catalina), Rodrigo de Triana (Cadenas), San Jacinto (Santo Domingo), and Pureza (Larga). Of all of these, Pagés del Corro Street was notable for its large concentration of corrales, especially during the heyday of the gypsy trade in the 18th century. This boom made the street one of the most overcrowded, reaching its peak of population around 1950. La Cava, originally a medieval moat used to defend Triana, was considered an unhealthy and dangerous area from the 16th century, although it still housed several corrales. Among the known corrales in the Cava Vieja were

de Judíos,

de Esparto,

de Navarra, de Juan Ruiz, and

de Platero, all of which are documented from 1706 in the population registers. In the Cava Nueva, other corrales were found, such as those of de Aromo and

de Encarnación, referenced between 1705 and 1706 [

29].

Other streets that housed many corrales were Alfarería, Castilla and Pelay Correa (Santa Catalina). In Alfarería Street, there were outstanding corrales such as La Bomba (also known as La Casa Grande), del Túnel, where tiles, and flowerpots were made, and Largo, among others. Castilla Street, on the other hand, was famous for having several corrales and pottery kilns, such as the Corral Verde, el Hondo, del Facundo, del Padre Santo, de la Cruz, and de Mateos, among others, according to records from 1705. In Pelay Correa (Santa Catalina), known for its high concentration of corrales and industries, such as de Doña Mensía (1665), del Moral (1705), and del Parra (1706) were documented.

In other areas, such as Rodrigo de Triana (Cadenas), important corrales were documented, such as those of

de Penitencia,

Los Palos, and

Casa de las Atarazanas. San Jacinto, despite being an eminently commercial area, also housed several corrales, including

de la Piedad (1705),

del Parra (disappeared in 1880), and

de Escalante. Finally, in Pureza Street (Ancha, Larga), some corrales and were found, such as the

Casa-horno de la Secretaría (1665-1705) and

el Haza de Sra. Santa Ana (1705) [

29].

6.2. Mesones and Posadas

One of the most prominent residential forms in Triana, especially for those who passed through the city or stayed temporarily, were the mesones and posadas. In 16th century Seville, a clear architectural and functional distinction existed between these, while in English, the term inn encompassed both concepts. Mesones provided both food and lodging, often catering to transient travellers and merchants. These establishments were typically organized around a central courtyard, where stables and storage spaces accommodated guests traveling with goods or animals. In contrast, posadas offered more stable lodging for long-term residents or regular visitors, with a greater emphasis on private rooms and communal areas. This differentiation reflects not only variations in urban hospitality services but also distinct architectural layouts within the city’s-built environment. The English term inn does not capture these nuances, as it historically referred to establishments offering both lodging and meals without necessarily distinguishing between their architectural structures or primary clientele.

The number of these were significant in the 16th century, around 70 establishments were registered throughout Seville, of which four were in Triana [

37]. These inns were concentrated in the access areas to the city, particularly in the streets near the entrances to the roads that connected Triana with other towns, such as the roads to Castilleja, Tomares, and Aljarafe. In particular, the most commercial streets of Triana, such as Castilla, San Jacinto (Santo Domingo) and Alfarería (Barrionuevo), were the main locations of these establishments.

Macías Míguez’s exhaustive study of the streets of Triana also documented several inns on these same streets. In Alfarería Street, the

Mesón de los Amoladores, which was in operation until 1900, stood out. In Castilla Street, there were the inns

de Las Cuevas,

de Las Bocas,

de La Concepción, and the

Posada Nueva or

Posada de Don Juan y

del Duque (1715). In San Jacinto Street, the inn

de Cotarros,

de la Gallega, and

de Las Ánimas were recorded, which continued to work until 1940 [

29]. These places not only provided accommodation, but also served as meeting places, particularly in the context of the commercial and transit flows of the time.

One of the most important inns, according to documentary sources, was the Mesón de la Reina, found in Alfarería Street (Barrionuevo). This inn was found next to a house rented by a widowed woman, which belonged to Seville Cathedral. Curiously, municipal ordinances prohibited the sale of food in the inns, so it was often the women who oversaw cooking for the inn’s customers. This type of activity was not exceptional, and it is highly likely that this was the case with Juana Fernández, who oversaw preparing meals in this establishment.

Despite the wealth of documentation on the inns in Triana, no specific survey plans have been found for them, which has prevented a detailed graphic reconstruction of their structures. However, their organization can be inferred from the common characteristics of the inns in Seville [

38]. These spaces were made up of a large gatehouse that gave access to the dwelling, stables that occupied a third of the total surface area, and a courtyard or corral that stood for another third of the space. In addition, the inns had rooms and guest quarters, and sometimes included wells, water basins, and latrines. For the accommodation of horses, suitable stables were provided. This architectural model reflected a functionality oriented towards both lodging and added services, such as animal care and the provision of food and drink for travellers and constituted a key element in the urban life of Triana during this period.

The prevalence of inns in Triana, as in other areas outside the city walls, underlines the importance of the area as a meeting point for travellers, traders, and temporary residents, which eased not only economic exchange but also the integration of different urban activities in a context of great social dynamism.

7. Current state of the Houses in Triana

The images and the surveys documents are a fundamental source for the study of the modern history of Triana, both for their descriptive richness and for the degree of detail with which the masters reflected the buildings in their drawings and writings. In the specific case of the surveys, these documents not only offer a quantitative view of the buildings, but also allow them to be classified, giving a deeper insight into their architectural characteristics and historical context. This is why the texts and drawings of the survey documents, when they are preserved, become authentic repositories of information, holding data on the life cycle of the buildings and on the people who lived in them over time (

Figure 17).

The architecture reflected in these documents is of great heritage value and should have received an adequate level of protection. However, the difficulty in finding, identifying and preserving these buildings has been a constant obstacle to their safeguarding. Today, new research tools and approaches allow for a better understanding of these architectural assets, which can contribute significantly to their conservation, restoration or at least their proper documentation. However, any effort in this direction must be based on precise knowledge, based on documentary sources covering the graphic as well as the textual, and historiographical dimensions.

The primary aim of this research is to offer new insights into the historical and architectural context of the Triana district at a pivotal moment in its development while also contributing to the broader study of architecture and, more specifically, 16th-century domestic architecture. Reconstructing this architectural past through historical documents presents a significant challenge, as most of the recorded buildings have vanished over time (

Figure 18).

Nevertheless, as far as possible, an effort has been made to find the original locations of these buildings and to analyse what remains have survived to the present day. In many cases, the absence of physical structures further emphasises the importance of preserving the available documentation, which is the main testimony of a lost architecture and the key to understanding its role in the urban history of the city (

Figure 19).

This article has presented a systematic compilation of the sources of information used, as well as a working method developed over years of research. This approach has mitigated the many challenges inherent in the reconstruction of Triana’s historic architecture, providing a solid basis for future research and action in the field of architectural heritage conservation.

8. Conclusions

Living in Triana gave an intense sense of belonging to those who lived in the neighbourhood. The Neighbours, known as

trianeros, named themselves a unique community, clearly differentiating themselves from the

sevillanos or people from other regions. During the 16th and 17th centuries, Triana was home to a great diversity of trades, which contributed to the uniqueness of its identity. Among the most common inhabitants were sailors, both in their various specialties and in the different social strata, potters, builders, farmers, stockbreeders, and other workers linked to ceramics, soap, and gunpowder. The presence of slaves, especially in the houses of the wealthiest, and Moors, was also part of the social structure of the neighbourhood (

Figure 20).

In urban planning terms, Triana is characterized by a dispersed settlement pattern, with many humble houses. The plots were larger toward the outskirts of the neighbourhood and smaller in the central core, particularly along major streets such as Altozano, San Jacinto, Pureza, and Castilla.

The dwellings in Triana followed the typology of single-family houses, which were the most usual form of construction in the area. However, there were also a notable number of tenement houses, which began to proliferate especially in the 18th century. Despite the presence of inns in the historical documentation, this type of dwelling was not common for the Trianeros, but was occupied by the innkeepers, who lived in or around these establishments (

Figure 21).

Architecturally, the buildings in Triana shared many similarities with those in Seville but differed in some aspects. Firstly, the height of the buildings in Triana was lower, with single-story houses being the most common. Additionally, the plots were larger compared to those in the neighbouring city. Other distinctive features included the presence of a well in some houses, though not all had one, and the layout of outdoor spaces, where corrales de vecinos typically occupied a larger area than patios, reflecting the importance of open spaces in the neighbourhood’s daily life.

Triana stood out not only for its social and professional diversity but also for its unique urban and architectural layout. While it shared certain elements with Seville, it featured distinctive characteristics that defined its identity as a place with a powerful sense of community and a particular adaptation to the needs and customs of its inhabitants (

Figure 22).

9. Triana Empty of Trianeros... the Future

The Triana neighbourhood, an emblem of Sevillian identity, is facing a transformation that threatens its essence: there are more tourists and fewer trianeros. The rise of holiday rentals and property speculation have pushed up house prices, making it difficult for the families who have always lived in the neighbourhood to continue living there (

Figure 23).

Many houses, once full of life and tradition, now remain closed or are temporarily occupied by visitors. Tourist overcrowding, although beneficial for the local economy, is blurring the everyday life of the neighbourhood, turning it into a showcase rather than a home. Triana is being emptied of trianeros, and with them its customs, its neighbourhood atmosphere, its soul, and its history are being lost.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.M.-O and M.N.-G.; investigation, P.M.-O and M.N.-G.; resources, M.N.-G.; writing, original draft preparation, P.M.-O. and M.N.-G.; writing-review and editing, P.M.-O. and M.N.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is the result of the of the project R + D + I Grant Calling a spade a spade: (Re)constructing fifteenth and sixteenth-century housing with words and images. PID2022-136565NB-I00. PI: Maria Elena Diez Jorge; co-PI: Ana Aranda Bernal. Funded by MCIU/AEI/ 10.13039/501100011033 and by ERDF, EU.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors are members of the research group Expregrafica. Lugar, Arquitectura y Dibujo (PAIDI-HUM-976).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACS |

Archivo de la Catedral de Sevilla –Seville Cathedral Archive– |

| ADPSE |

Archivo de la Diputación Provincial de Sevilla –Provincial Council Archive of Seville– |

| AHPSPN |

Archivo Histórico Provincial de Sevilla Protocolos Notariales –Provincial Historical Archive of Seville Notarial Protocols– |

References

- Gutiérrez Millán, M. E. El espacio urbano en la ciudad de Salamanca, escenario físico de un equilibrio de poderes. Revista de estudios extremeños 2001, 1, 181–198.

- Moya-Olmedo, M. P.; Núñez-González, M. De ciudades y de hombres: Primer urbanismo americano del siglo XVI. Quiroga. Revista de Patrimonio Iberoamericano 2023, 22, 126–143. [CrossRef]

- González Jiménez, J. Repartimiento de Sevilla (Vol. 1); Ayuntamiento de Sevilla: Sevilla, Spain, 1988.

- Carriazo y Arroquia, J. de M. Anecdotario sevillano; Imprenta Municipal: Sevilla, Spain, 1988.

- Arevalo Rodríguez, F. La representación de la ciudad en el Renacimiento. Levantamiento urbano y territorial; Caja de Arquitectos: Barcelona, Spain, 2003.

- Cámara Muñoz, A.; Gómez López, C. (Eds.). La imagen de la ciudad en la Edad Moderna; Editorial Universitaria Ramón Aceres: Madrid, Spain, 2011.

- Kagan, R. L. (Ed.) Ciudades del Siglo de Oro: Las vistas españolas de Anton van den Wyngaerde; El Viso: Madrid, Spain, 1986.

- Schefold, M. Georg Braun and Franz Hogenberg: Beschreibung und Contrafactur der vornembster Stät der Welt 1574–1618, 6 vol. [facsimile]; Simbach am Inn, Müller und Schindler: Stuttgart, Germany, 1965.

- Skelton, R. S. Braun, G. y Hogenberg, F. Civitates Orbis Terrarum, 3 vol. [facsimile]; Theatrum Orbis Terrarum Ltd.: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 1965.

- Diaz Zamudio, T.; Gámiz Gordo, A. Views of Seville environs until 1800. In Graphic Imprints; Springer, 2018; pp. 1177–1188. [CrossRef]

- Cabra Loredo, M. D.; Santiago Paez, E. Iconografía de Sevilla: 1400-1650; Fundación Focus-El Viso: Madrid, Spain, 1988.

- Valor Piechotta, M.; Romero Moragas, C. (Eds.) Sevilla extramuros. La Huella de la Historia en el Sector Oriental de la Ciudad; Universidad de Sevilla, Sevilla, Spain, 1998.

- Morales Padrón, F. Historia de Sevilla. La ciudad del Quinientos; Universidad de Sevilla: Sevilla, Spain, 1977.

- Albardonedo Freire, A. El urbanismo de Sevilla durante el reinado de Felipe II; Ediciones Guadalquivir: Sevilla, Spain, 2002.

- Moral Ituarte, L. del. La obra hidráulica en la cuenca baja del Guadalquivir (siglos XVIII–XX): gestión del agua y organización del territorio; Universidad de Sevilla: Sevilla, Spain, 1991.

- Jiménez Maqueda, D. Estudio histórico-arqueológico de las puertas medievales y postmedievales de las murallas de la ciudad de Sevilla; Fundación Aparejadores y Ediciones Guadalquivir: Sevilla, Spain, 1999.

- Pérez Cano, M. T. Patrimonio y ciudad. El sistema de los conventos de clausura en el centro histórico de Sevilla: génesis, diagnósticos y propuesta de intervención para su recuperación urbanística; Universidad de Sevilla, Fundación Focus: Sevilla, Spain, 1996.

- Chueca Goitia, F.; Domínguez Ortiz, A.; Hermosilla Molina, A. Los Hospitales de Sevilla; Real Academia Sevillana de Buenas Letras: Sevilla, Spain, 1989.

- Montes Romero-Camacho, I. El paisaje rural sevillano en la Baja Edad Media: aproximación a su estudio a través de las propiedades del Cabildo-Catedral de Sevilla; Diputación de Sevilla: Sevilla, Spain, 1989.

- Gestoso Pérez, J. Curiosidades Antiguas Sevillanas. 1910. Grosso Galván, M. (Ed); Ayuntamiento de Sevilla: Sevilla, Spain, 1993.

- Álvarez-Benavides, A. Curiosidades sevillanas. 1898-1899. Castillo Martos M., (Ed.); Universidad de Sevilla: Sevilla; Spain, 2021.

- Acosta Dominguez, V. Triana. De puente a puente (1147-1853); El Monte de Piedad y Caja de Ahorros: Sevilla, Spain, 1979.

- Macías Miguez, M. Triana. El caserío: calles, plazas, sitios y lugares; Ayuntamiento de Sevilla, Tenencia de Alcaldía de Triana: Sevilla, Spain, 1982.

- Díaz Garrido, M. Triana y la orilla derecha del Guadalquivir; Universidad de Sevilla, Fundación Focus-Abengoa: Sevilla, Spain, 2010.

- Morgado, A. de. Historia de Sevilla; Ayuntamiento de Sevilla, Instituto de la Cultura y las Artes: Sevilla, Spain, 2017.

- González Moreno, J. Descubrimiento en Triana: las cuevas del jabón; RC Editor: Sevilla, Spain, 1989.

- Collantes de Terán Sánchez, A. Sevilla en la Baja Edad Media: la ciudad y sus hombres; Sección de Publicaciones del Excmo. Ayuntamiento: Sevilla, Spain, 1977.

- Rodriguez Vicente, M. E. Trianeros en Indias en el siglo XVI. In Andalucía y America en el siglo XVI: actas de las II Jornadas de Andalucía y América; Torres Ramírez, B.; Hernández Palomo, J. J. (Coord.); 1983; Volume 1, pp. 135–146.

- Macías Míguez, M. Triana: el caserío: calles, plazas, sitios y lugares; Ayuntamiento de Sevilla, Tenencia de Alcaldía de Triana: Sevilla, Spain, 1982..

- Núñez-González, M. Arquitectura, dibujo y léxico de alarifes en la Sevilla del siglo XVI. Casas, corrales, mesones y tiendas; Universidad de Sevilla, Fundación Focus: Sevilla, Spain, 2021.

- Quiles García, F.; Fernández Chaves, M. F.; Fialho Conde A. (Coords.) La Sevilla Lusa la presencia portuguesa en el Reino de Sevilla durante el Barroco; Enredars: Sevilla, Spain, 2018.

- Núñez-González, M. La representación gráfica de la casa en Sevilla en los siglos XVI y XVII. In De trazos, huellas e improntas: arquitectura, ideación, representación y difusión; Marcos Alba, C. L., Juan Gutiérrez, P. J., Domingo Gresa, J., Oliva Meyer. J. (Coord.); 2018; Volume 1, pp. 595–604.

- Núñez-González, M. Arquitectura, dibujo y léxico de alarifes en la Sevilla del siglo XVI. Casas, corrales, mesones y tiendas; Universidad de Sevilla, Fundación Focus: Sevilla, Spain, 2021.

- Fernández Salinas, V. Vivienda modesta y patrimonio cultural: los corrales y patios de vecindad en el conjunto histórico de Sevilla. Scripta Nova 2003, 7(146).

- Núñez-González, M. Los corrales de vecinos en la Sevilla del Siglo de Oro. Laboratorio de Arte 2019, 31, 229–246.

- Díaz Garrido, M.; Bravo Bernal, A. M.; Castellano Román, M. Corrales de vecinos en Triana; Universidad de Sevilla, Departamento de Expresión Gráfica Arquitectónica: Sevilla, Spain, 2010.

- Núñez-González, M. Vocabulario arquitectónico ilustrado. La casa sevillana del siglo XVI. Universidad de Granada: Granada, Spain, 2022.

- Núñez-González, M.; Moya-Olmedo, P. Trazas del arquitecto sevillano Pedro Sánchez Falconete entre 1603 y 1628. EGA Expresión Gráfica Arquitectónica 2024, 29(52), 56–69. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

‘Seville, the Guadalquivir River, and Triana in the 16th century’. Chaves J. (1579). Hispalensis conventus delineatio. En Ortelius A. Theatrum Orbis Terrarum. Antuerpiae, Antwerp.

Figure 1.

‘Seville, the Guadalquivir River, and Triana in the 16th century’. Chaves J. (1579). Hispalensis conventus delineatio. En Ortelius A. Theatrum Orbis Terrarum. Antuerpiae, Antwerp.

Figure 2.

‘View of the city of Seville from Triana’. Attributed to Sánchez Coello, A. (c. the end of the 16th century). View of Seville [Painting]. Museo de América –Museum of America–, Madrid, Spain.

Figure 2.

‘View of the city of Seville from Triana’. Attributed to Sánchez Coello, A. (c. the end of the 16th century). View of Seville [Painting]. Museo de América –Museum of America–, Madrid, Spain.

Figure 3.

Collaciones –quarters– in the 16th century Seville. Source the authors.

Figure 3.

Collaciones –quarters– in the 16th century Seville. Source the authors.

Figure 4.

‘View of Seville: Triana appears on the right’. Braun, G.; Hogenberg, F. (1572). Civitates Orbis Terrarum (Vol. 1). Cologne and Antwerp. Source Biblioteca Nacional de España –National Library of Spain–, Madrid, Spain.

Figure 4.

‘View of Seville: Triana appears on the right’. Braun, G.; Hogenberg, F. (1572). Civitates Orbis Terrarum (Vol. 1). Cologne and Antwerp. Source Biblioteca Nacional de España –National Library of Spain–, Madrid, Spain.

Figure 5.

‘View of Seville and view of Triana according to Anton van den Wyngaerde’. Wyngaerde A. van den. (1567). View of Seville [Drawing]. Österreichische Nationalbibliothek –National Library of Austria–, Vienna, Austria; Wyngaerde A. van den. (1567). View of Triana [Drawing]. Österreichische Nationalbibliothek –National Library of Austria–, Vienna, Austria.

Figure 5.

‘View of Seville and view of Triana according to Anton van den Wyngaerde’. Wyngaerde A. van den. (1567). View of Seville [Drawing]. Österreichische Nationalbibliothek –National Library of Austria–, Vienna, Austria; Wyngaerde A. van den. (1567). View of Triana [Drawing]. Österreichische Nationalbibliothek –National Library of Austria–, Vienna, Austria.

Figure 6.

‘View of Triana according to Anton van den Wyngaerde’. Wyngaerde A. van den. (1567). Panoramic View of Seville and Triana [Drawing]. Victoria and Albert Museum, London, Great Britain.

Figure 6.

‘View of Triana according to Anton van den Wyngaerde’. Wyngaerde A. van den. (1567). Panoramic View of Seville and Triana [Drawing]. Victoria and Albert Museum, London, Great Britain.

Figure 7.

‘View of Seville, Triana in the foreground below according to Ambrogio Brambilla’. Brambilla, A. (1585). View of Seville [Engraving]. Biblioteca Nacional de España –National Library of Spain–, Madrid, Spain.

Figure 7.

‘View of Seville, Triana in the foreground below according to Ambrogio Brambilla’. Brambilla, A. (1585). View of Seville [Engraving]. Biblioteca Nacional de España –National Library of Spain–, Madrid, Spain.

Figure 8.

Triana, the Guadalquivir River, and Seville (based on Núñez-González 2021). Source the authors.

Figure 8.

Triana, the Guadalquivir River, and Seville (based on Núñez-González 2021). Source the authors.

Figure 9.

‘The view of Triana according to Anton van den Wyngaerde: can be found the Pontoon Bridge over the Guadalquivir River, several churches, one city gate, the sandbank, etc.’ Wyngaerde A. van den. (1567). Panoramic View of Seville and Triana (Detail) [Drawing]. Victoria and Albert Museum, London, Great Britain.

Figure 9.

‘The view of Triana according to Anton van den Wyngaerde: can be found the Pontoon Bridge over the Guadalquivir River, several churches, one city gate, the sandbank, etc.’ Wyngaerde A. van den. (1567). Panoramic View of Seville and Triana (Detail) [Drawing]. Victoria and Albert Museum, London, Great Britain.

Figure 10.

Triana (based on Núñez-González 2021). Source the authors.

Figure 10.

Triana (based on Núñez-González 2021). Source the authors.

Figure 11.

Triana appears on the right: can be found the castle, the Reales Almonas or Xavoneria –sopaery–, the word alfarería –pottery– alluding to the pottery kilns that existed, the Pontoon Bridge over the Guadalquivir River. Braun, G.; Hogenberg, F. (1572). Civitates Orbis Terrarum (Vol. 1). Cologne and Antwerp. Source Biblioteca Nacional de España –National Library of Spain–, Madrid, Spain.

Figure 11.

Triana appears on the right: can be found the castle, the Reales Almonas or Xavoneria –sopaery–, the word alfarería –pottery– alluding to the pottery kilns that existed, the Pontoon Bridge over the Guadalquivir River. Braun, G.; Hogenberg, F. (1572). Civitates Orbis Terrarum (Vol. 1). Cologne and Antwerp. Source Biblioteca Nacional de España –National Library of Spain–, Madrid, Spain.

Figure 12.

Like most Iberian cities, Seville’s urban structure continued to have medieval characteristics, the city was organized around its walls and churches and buildings tended to have narrow, deep facades and were squeezed around religious institutions, forming dense neighbourhoods. In the suburbs, as in the case of Triana, buildings were dispersed along gates and roads, and open spaces increased. Brambilla, A. (1585). View of Seville (Detail) [Engraving]. Biblioteca Nacional de España –National Library of Spain–, Madrid, Spain.

Figure 12.

Like most Iberian cities, Seville’s urban structure continued to have medieval characteristics, the city was organized around its walls and churches and buildings tended to have narrow, deep facades and were squeezed around religious institutions, forming dense neighbourhoods. In the suburbs, as in the case of Triana, buildings were dispersed along gates and roads, and open spaces increased. Brambilla, A. (1585). View of Seville (Detail) [Engraving]. Biblioteca Nacional de España –National Library of Spain–, Madrid, Spain.

Figure 13.

‘Surveys (cover, literary, and graphic pages). Resta, V. (1603-1627). (File 8-bis, protocol 180). ADPSE, Seville, Spain.

Figure 13.

‘Surveys (cover, literary, and graphic pages). Resta, V. (1603-1627). (File 8-bis, protocol 180). ADPSE, Seville, Spain.

Figure 14.

Location of the houses (red, literary surveys; purple, graphic surveys). Source the authors.

Figure 14.

Location of the houses (red, literary surveys; purple, graphic surveys). Source the authors.

Figure 15.

Functional graphic analysis of some dwellings. Source the authors.

Figure 15.

Functional graphic analysis of some dwellings. Source the authors.

Figure 16.

House and atahonas of Alonso Romí; house, orchard, and vineyards of Rodrigo de Chaves, neighbour of Seville; house of Juana Fernández, widow –drawings according to the surveys–. Source the authors.

Figure 16.

House and atahonas of Alonso Romí; house, orchard, and vineyards of Rodrigo de Chaves, neighbour of Seville; house of Juana Fernández, widow –drawings according to the surveys–. Source the authors.

Figure 17.

Santa Ana Square, Pureza Street, San Jacinto Street, and Betis Street: Then and Now. Source Municipal Archive of Seville and the authors.

Figure 17.

Santa Ana Square, Pureza Street, San Jacinto Street, and Betis Street: Then and Now. Source Municipal Archive of Seville and the authors.

Figure 18.

Corral de las flores, ‘patio of casa de vecindad’ said the image, and Casa Quemada: Then. Source Municipal Archive of Seville.

Figure 18.

Corral de las flores, ‘patio of casa de vecindad’ said the image, and Casa Quemada: Then. Source Municipal Archive of Seville.

Figure 19.

Pagés del Corro Street, corral de vecinos, San Jacinto Street, Corral de la Parra, and two houses in Betis Street: Now. Source the authors.

Figure 19.

Pagés del Corro Street, corral de vecinos, San Jacinto Street, Corral de la Parra, and two houses in Betis Street: Now. Source the authors.

Figure 20.

The sense of belonging to Triana is reflected in many plaques, commemorating artists, politicians, or ordinary residents that the neighbourhood once had or recognizes as trianeros. Source the authors.

Figure 20.

The sense of belonging to Triana is reflected in many plaques, commemorating artists, politicians, or ordinary residents that the neighbourhood once had or recognizes as trianeros. Source the authors.

Figure 21.

Up ‘The view of Triana according to Anton van den Wyngaerde: can be found the Pontoon Bridge over the Guadalquivir River, several churches, one city gate, the sandbank, etc.’ Wyngaerde A. van den. (1567). Panoramic View of Seville and Triana (Detail) [Drawing]. Victoria and Albert Museum, London, Great Britain. Down ‘The view of Triana from La Giralda’. Source Municipal Archive of Seville.

Figure 21.

Up ‘The view of Triana according to Anton van den Wyngaerde: can be found the Pontoon Bridge over the Guadalquivir River, several churches, one city gate, the sandbank, etc.’ Wyngaerde A. van den. (1567). Panoramic View of Seville and Triana (Detail) [Drawing]. Victoria and Albert Museum, London, Great Britain. Down ‘The view of Triana from La Giralda’. Source Municipal Archive of Seville.

Figure 22.

Yo si soy nacío en Triana –I was indeed born in Triana– is displayed on a plaque on the façade of a house, as a symbol of the feeling and pride of being from Triana. Source the authors.

Figure 22.

Yo si soy nacío en Triana –I was indeed born in Triana– is displayed on a plaque on the façade of a house, as a symbol of the feeling and pride of being from Triana. Source the authors.

Figure 23.

‘The Triana Hotel, once upon a time one corral de vecinos full of vecinos, now is a space empty of vecinos al full of cars.’ Source Municipal Archive of Seville and the authors.

Figure 23.

‘The Triana Hotel, once upon a time one corral de vecinos full of vecinos, now is a space empty of vecinos al full of cars.’ Source Municipal Archive of Seville and the authors.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).