1. Introduction

Described initially in 1974 [30], the current definition of burnout by the World Health Organization is as an occupation-dependent syndrome arising from unsuccessfully managed chronic workplace stress, with symptoms of reduced professional efficacy ranging from energy depletion or exhaustion to an increased work-related mental distance, negativism, or cynicism [

1]. Considered specific to healthcare professionals initially [

2]—representing a significant cause of healthcare professional turnover [

3]—this syndrome can develop among all employee types [

4], resulting in self-undermining behaviors such as poor communication, careless mistakes, and interpersonal conflicts [

5]. Particularly in healthcare professionals, burnout is responsible for increased on-the-job errors and reduced patient care [

6]. Burnout was prevalent in employees with high-pressure jobs [

7] and widespread in healthcare professionals before COVID-19, with over one-half of physicians and one-third of nurses experiencing its symptoms in the US [

8]. The ending of COVID-19 as a global health emergency on 5 May 2023 [

9] marked more than three years of the pandemic that began [

10] on 11 March 2020 [

11]. Escalating burnout throughout the pandemic, COVID-19 represents the cause for increasing the complexity of finding solutions to burnout in all employees [

12], especially healthcare professionals [

13,

14].

Psychological flow is a desired experience that extends a person’s mind to its limits from a challenging and worthwhile voluntary effort to accomplish something valued such that a sense of time and place is lost [

15]. It was first described [

16] by Csikszentmihalyi in 1975 in a work examining flow in rock climbers, surgeons, composers, modern dancers, chess players, and basketball players [

17] and was the focus of his research program until his 2021 death [

18]. Pre-COVID-19, achieving flow in the workplace was recognized as an effective means to resist burnout [

19]. That there is a direct relationship between the identification of burnout and the urge to find psychological flow in work is no coincidence—the two represent opposite extremes of employee stimulation [

20].

The objective is to consider the achievability of psychological flow during the pandemic and, if realized, whether it retained the ability to avert burnout during COVID-19 in a manner that supports the direct connection between burnout and psychological flow attainment regarding a scale of workplace stimulation. A scoping review is the chosen methodology to achieve this. The choice of a scoping review on this topic is novel and provides insights into the type of effect COVID-19 had on the relationship between burnout and flow. The results demonstrate that achieving flow was possible during the pandemic by different types of employees and was realized in several ways—preventing burnout in each case. This result adds to the literature contrasting burnout with psychological flow regarding workplace stimulation regarding the effect of COVID-19.

2. Materials and Methods

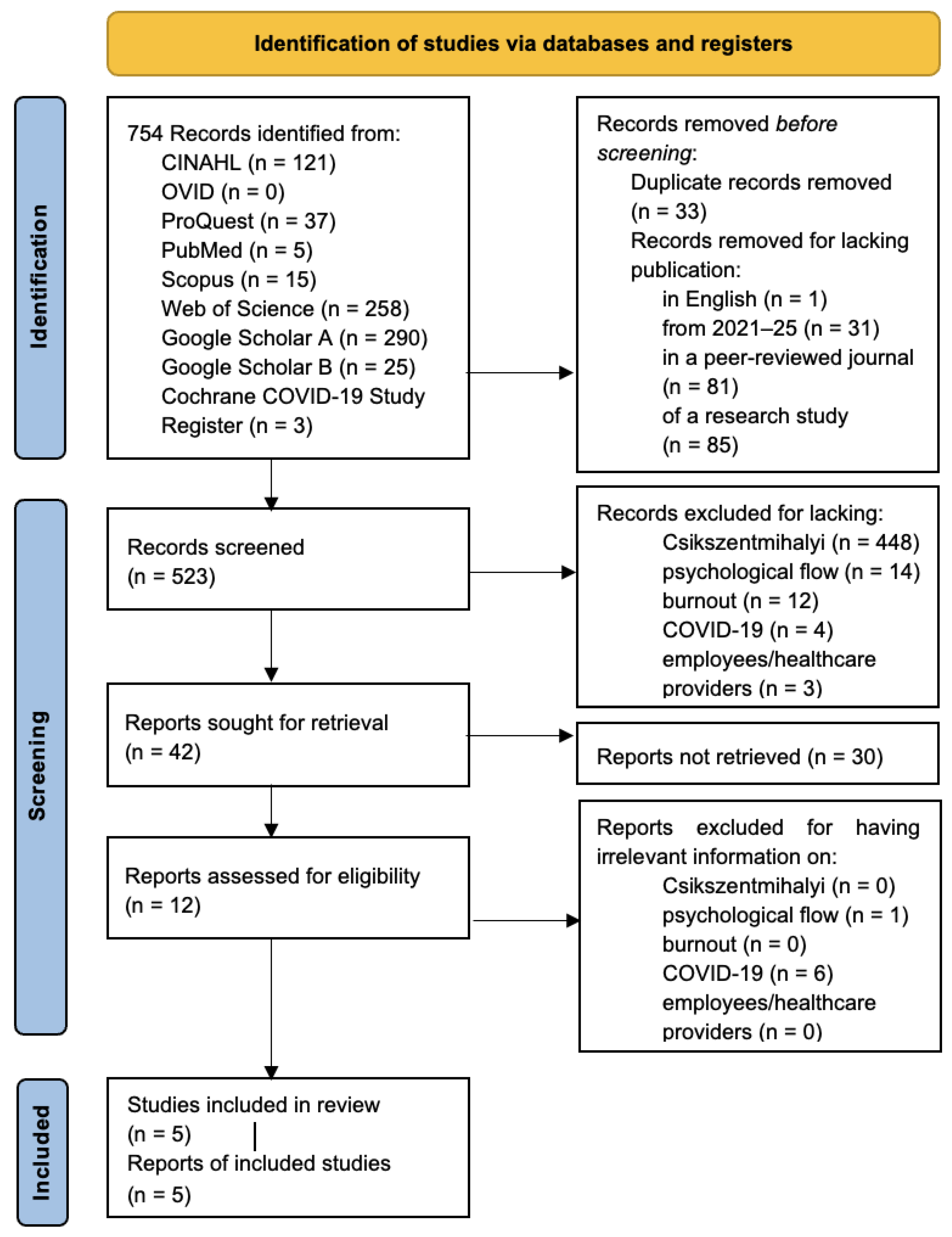

The methods of gathering the materials follow the most recent preferred reporting item for systematic review and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines for scoping reviews [

21,

22]. Internationally standardized [

23], the PRISMA process for scoping reviews is considered the best practice guidance for scoping reviews [

24]. The method includes a selection of databases and registers in searching the keywords, then removing records before screening duplicates, records not in English, those not from 2021-2025, not peer-reviewed, and not a research study. The records screened exclude those lacking Csikszentmihalyi, psychological flow, burnout, COVID-19, or employees/healthcare providers. If retrievable, no further consideration is given to reports of irrelevant information, making them ineligible. Following this process resulted in the studies included in the review—all of which represented the reports of the included studies.

The PRISMA flow of information diagram specific to scoping reviews represents the results of following this process. The most recent PRISMA template for scoping reviews [

25] is the basis of the exclusion and inclusion criteria flow. The PRISMA Scoping Review Checklist is in Supplementary S1: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist outlining the entire process undertaken in this article beyond the scoping review itself. Preregistration for this scoping review is at

https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/ARN8P (accessed on 8 March 2025).

The search selection of a scoping review is to investigate the range and depth of research on this subject. In contrast to examining PICO (population, intervention, comparison, and outcome) requiring a systematic review [

26], this purpose represents a scoping review that searches six primary databases (CINAHL, OVID, ProQuest, PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science), one supplementary database (Google Scholar)—searched in two ways—and one register (the Cochrane COVID-19 Register). Each was selected for relevance and reach [

27]. The selection of these databases represents those most relevant to burnout-related topics and those likely to produce the broadest reach [

27]. The common keywords searched are “burnout, COVID-19, employees, healthcare providers, psychological flow, Csikszentmihalyi” for each database. Each database had particular limitations to the search to achieve the necessary goal. The details of these eliminations are in Supplementary S2 under the specific search.

Following PRISMA guidelines [

23,

24,

28], Supplementary S2 notes all keywords beyond the initial ones. Excluded are reports of irrelevant information on any keywords (including those with keywords in the references alone). Following the PRISMA reporting process, the flow diagram does not reveal the details of the individual searches. Yet, this information is significant and is in Supplementary S2. Including this supplementary file represents counteracting the cognitive bias of one scholar completing the scoping review [

29,

30]. Selection bias is irrelevant [

31,

32] as this is a scoping review rather than a PRISMA systematic review and meta-analysis.

A 2019 study of twelve academic databases that found it the most comprehensive search engine [

33], additionally reconfirmed with 2023 research [

34], was the basis for selecting Google Scholar as a search engine database. It is a supplementary database from the judgment of 2020 [

27] research that evaluated it as unsuitable for primary review searches based on its delivery of inconsistent results and lack of Boolean search options. Yet, the same 2020 review acknowledges Google Scholar as the most comprehensive and used database by academics. As a scoping review, comprehensiveness is key. Consequently, the reach of Google Scholar as a database is significant to the intended purpose of the undertaking.

Google Scholar was alone in being searched twice, with the keywords listed differently for each search. The parameters for Google Scholar A were [Burnout psychological flow Csikszentmihalyi employees OR healthcare providers "COVID 19" since 2021]. For Google Scholar B, they were ["burnout" "psychological flow" "Csikszentmihalyi" employees OR healthcare providers "COVID 19" since 2021]. Both searches were retained as their results differed (see Supplementary S2).

All searches were performed on 8 February 2025 by the author.

3. Results

3.1. Search Process Results

There were 754 results from the six primary databases, one register, and the one supplementary database searched twice, with OVID returning none. Regarding the searches, the least accurate for this topic are CINAHL and Web of Science. For the CINAHL search, 116 of the 121 results did not mention Csikszentmihalyi, although a keyword in the search process and the initial return for this database was relatively substantial. With Web of Science, the lack of returns regarding Csikszentmihalyi was additionally considerable—216 of the 258 results. What is unique regarding the Web of Science review is that a consequential number of returns could not be retrieved—25. ProQuest had a similar problem to these databases regarding search accuracy, with 28 of the returns lacking Csikszentmihalyi. However, the difference is that the initial returns were fewer, at 37. The Cochrane COVID-19 Study Register produced only three results—two were duplicates, and one lacked mention of Csikszentmihalyi.

Twice-searched Google Scholar tested the difference between searching with quotation marks on only “COVID-19” (Google Scholar A) and differentiating all the keywords with quotation marks (Google Scholar B). Of the 25 returns in Google Scholar B, 18 are duplicates with Google Scholar A. Seven are distinct. Still, the result is that these that differ from Google Scholar A are not peer-reviewed—one does not mention Csikszentmihalyi. The final materials of this scoping review are five returns from the Google Scholar A search, demonstrating the value of Google Scholar as a search engine for this topic. A decision to avoid using Google Scholar resulting from its view as a supplementary database [

27] would have resulted in no relevant returns for this topic. Google Scholar B duplicates the first return of Google Scholar A. No other duplicates of the final Google Scholar A reports are with other database searches.

The process following the PRISMA guidelines for scoping reviews is in

Figure 1.

This process neglects the details of the exclusions by database, combining all results by the second stage of removing records before screening. Consequently, to improve the transparency of the process,

Table 1 provides the details of the exclusions for all searches. The total exclusions are 749. The row of duplicates in

Table 1 has two results in round brackets for PubMed (4) and Google Scholar A (27). These are the total duplicates. However, the recorded duplicates for each are 2 and 0, as the duplicates of these searches are those not removed before screening. For the complete account of each search process, see Supplementary S2.

3.2. Reports of Included Studies

Of the 29 pages representing the results returned from the Google Scholar A search, all six reports of included studies are in the first 11 pages. The first return was on page 1—the only duplicate with Google Scholar B of the reports included—“Psychological flow and mental immunity as predictors of job performance for mental health care practitioners during COVID-19” [

35]. The second of the returns was on page 3, “Building Nurse Resilience Through Art Therapy and Narrative Medicine Integration” [

36]. Page 5 saw the return of the third report, “Are algorithmically controlled gig workers deeply burned out? An empirical study on employee work engagement” [

37]. The fourth report returned on page 7, “Positive Coping and Well-being of Corporate Professionals during the Covid-19 Pandemic: A Single Case Study” [

38]. The final report is the fifth return on page 11 [

39]. Of these reports, the publication of the oldest was in 2022, and the most recent publication is from 2025. Initially, the consideration was that burnout represented symptoms associated with healthcare providers [

2]. Therefore, it is significant that the top three returns are three types of healthcare providers, with mental healthcare practitioners viewed as working under conditions most likely to produce burnout [

40]. The last three are workers in high-pressure occupations with significant burnout—either resulting from job demands or from mixing employment with parenthood [

41,

42,

43] (see

Table 2).

Each of the five included reports had multiple authors, were regarding studies in four different countries (and one conducted worldwide), published in various journals, and used a different methodology for the study reported (see

Table 3).

The report of the relevant study results found for each record is in

Table 4.

In “Psychological flow and mental immunity as predictors of job performance for mental health care practitioners during COVID-19” [

35], the claim is that psychological flow is a form of mental immunity to burnout, similar to biological immunity. This assertion arises from its ability to encourage professional development by creating “psychological capital” that motivates feelings of well-being, increasing productivity compared with individuals who do not exhibit psychological flow. The decision to test this supposition was a cross-sectional descriptive design study from 7 March 2022 to 28 August 2022, during the COVID-19 pandemic, to predict the job performance, mental immunity, and psychological flow of health mental care providers. The selection for the survey was a random sample of 145 Saudi mental health professionals, 120 of whom returned the questionnaire—64 men and 56 women, aged between 27 and 48. Psychological flow and mental immunity were statistically significant predictors of job performance among mental health care practitioners. The recommendation is for interventions to enhance the psychological flow, mental immunity, and job performance of mental health care practitioners to promote effective coping with work stress and protect them from symptoms of burnout.

“Building Nurse Resilience Through Art Therapy and Narrative Medicine Integration” [

36] presents a qualitatively focused mixed-methods study to develop a narrative medicine protocol for enhancing nurse resilience through the integration of art prompts respecting the Expressive Therapies Continuum (ETC) model. During the pandemic in 2022, nine participants across two cohorts completed a 4-week asynchronous online workshop. Quantitative results showed no statistically significant changes; however, the feasibility and practical benefits of the intervention were evident with the 15-minute art prompt through fostering positive emotions, sensory engagement, and meaning-making, aligning with the PERMA model [

44,

45]. The conclusion is that existing narrative medicine programs in healthcare institutions can incorporate art prompts to promote healthcare worker resilience regarding burnout.

The study of the ability of psychological flow to avert burnout during COVID in “Are algorithmically controlled gig workers deeply burned out? An empirical study on employee work engagement” [

37], was regarding the survey results from two provinces in China of 400 gig workers at several digital platform companies. Two-thirds of the respondents were men, while a third were women, with the highest percentage of respondents being between 20 and 30 years old. Over three quarters had at least one higher education degree and were full-time employees. The ability of the workers to recognize and evaluate algorithmic control in human-computer interaction fundamentally influenced the attitude and behavior of gig workers during COVID-19. Different gig workers had distinct perceptions and understandings about algorithmic control, affecting their responses accordingly. The authors note that control over data algorithms intensified following COVID-19. The result was a moderating effect of flow experience on the positive relationship between perceived algorithmic control and burnout. Psychological flow experience was a significant antecedent variable of employee work engagement during the pandemic.

Corporate professionals are the focus of “Positive Coping and Well-being of Corporate Professionals during the Covid-19 Pandemic: A Single Case Study” [

38] with the aim of the study understanding how the positive coping strategies used by corporate professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic influenced their well-being. From a group of 20 corporate professionals interviewed worldwide, one engaged in a phenomenological research study. Flow was among the human strengths mentioned as relevant to averting burnout during the pandemic regarding the PERMA model of well-being that focuses on individual strengths. Although COVID-19 was challenging for the corporate professional, in being able to meet the challenge successfully, there was obtainment of the type of enjoyment that comes with achieving psychological flow—this enjoyment extended to increased quality family time. The advice is that the methods and thinking patterns used by corporate professionals might be adopted successfully in other fields to produce positive outcomes.

The concern of “The COVID-19 pandemic's effect on family leisure activities of working parents with pre-school aged children” [

39] was also family time. A self-administered questionnaire collected the views of 140 South African working parents with preschool-aged children regarding their leisure activities and changes to these activities that affected work-life balance and overall well-being of parents. Pre-COVID-19, parents indicated that they had personal leisure time available. During the initial lockdown of the pandemic, while confined to their homes and because of the blurred boundaries between work, leisure, caring, and household duties, they experienced negative emotions and tiredness, i.e., emotional burnout. However, as the pandemic continued, there was a shift in family leisure activities, permitting newly embraced leisure activities to reshape family leisure choices and options. The authors indicate that psychological flow illustrates the type of deep engagement parents described regarding these new activities, driven by intrinsic joy with an alignment between challenges and abilities. The study raises awareness regarding the significance of work-life balance during pandemic situations, as recognizing the role of leisure activities for parents of preschool-aged children in promoting psychological flow can avert burnout.

4. Conclusions

The results of this scoping review of burnout avoidance by employees during COVID-19 through achieving psychological flow were various.

Google Scholar alone identified relevant peer-reviewed articles for this assessment and did so most effectively by isolating the search terms least, questioning the belief that this search engine is merely supplementary.

The included articles demonstrate that psychological flow was achievable by several types of employees during the pandemic, experiencing flow, averting burnout, and the achievement of flow differed.

For mental health practitioners, flow was attained during COVID-19 directly through their particular relationship to work. Nurses experienced flow in art therapy sessions specifically offered in response to COVID-19. Gig workers experienced a direct relationship between perceived algorithmic control and burnout, with psychological flow significantly variable concerning employee work engagement during the pandemic. Corporate professions, though initially experiencing burnout during the pandemic, were able to challenge themselves using the peak of their skills to produce the level of enjoyment resulting in flow. One of the areas in which they experienced flow was leisure pursuits. The study of preschool-aged parents reinforced the value of peak experiences in leisure activities to avert workplace burnout.

Together, these five included reports—identified using the PRISMA process for scoping reviews—reinforce that psychological flow represents the opposite of burnout regarding a workplace stimulation scale. Furthermore, if an employee experiences psychological flow, they cannot simultaneously suffer from burnout. To further test that psychological flow and burnout are mutually exclusive, especially in pandemic situations, the suggestion is for future research. Psychological flow was possible during COVID-19 for various employee types, and attaining it permitted burnout avoidance, suggesting a focus on achieving flow in the workplace during pandemics would diminish the incidence of employee burnout.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

Preprints.org, Supplementary S1: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist; Supplementary S2: Nine Database Searches.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- World Health Organization Burn-out an “Occupational Phenomenon”: International Classification of Diseases 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/28-05-2019-burn-out-an-occupational-phenomenon-international-classification-of-diseases (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Maslach, C.; Leiter, M.P. The Burnout Challenge: Managing People’s Relationships with Their Jobs; Harvard university press: Cambridge (Mass.) London, 2022; ISBN 978-0-674-25101-4.

- Tabur, A.; Elkefi, S.; Emhan, A.; Mengenci, C.; Bez, Y.; Asan, O. Anxiety, Burnout and Depression, Psychological Well-Being as Predictor of Healthcare Professionals’ Turnover during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Study in a Pandemic Hospital. Healthcare 2022, 10, 525. [CrossRef]

- Edú-Valsania, S.; Laguía, A.; Moriano, J.A. Burnout: A Review of Theory and Measurement. IJERPH 2022, 19, 1780. [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; De Vries, J.D. Job Demands–Resources Theory and Self-Regulation: New Explanations and Remedies for Job Burnout. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping 2021, 34, 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, M.; Asadi-Pooya, A.A.; Mousavi-Roknabadi, R.S. Burnout among Healthcare Providers of COVID-19; a Systematic Review of Epidemiology and Recommendations : Burnout in Healthcare Providers. Archives of Academic Emergency Medicine 2020, 9, e7. [CrossRef]

- Hurria, C. Burnout – An Exponential Rise. JOP 2023, 23. [CrossRef]

- Reith, T.P. Burnout in United States Healthcare Professionals: A Narrative Review. Cureus 2018, 10, e3681. [CrossRef]

- Rigby, J.; Satija, B. WHO Declares End to COVID Global Health Emergency. Reuters 2023. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-pharmaceuticals/covid-is-no-longer-global-health-emergency-who-2023-05-05/ (accessed on 31 March 2024).

- Morgantini, L.A.; Naha, U.; Wang, H.; Francavilla, S.; Acar, Ö.; Flores, J.M.; Crivellaro, S.; Moreira, D.; Abern, M.; Eklund, M.; et al. Factors Contributing to Healthcare Professional Burnout during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Rapid Turnaround Global Survey. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0238217. [CrossRef]

- Cucinotta, D.; Vanelli, M. WHO Declares COVID-19 a Pandemic. Acta Bio Medica Atenei Parmensis 2020, 91, 157–160. [CrossRef]

- Kloutsiniotis, P.V.; Mihail, D.M.; Mylonas, N.; Pateli, A. Transformational Leadership, HRM Practices and Burnout during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Role of Personal Stress, Anxiety, and Workplace Loneliness. International Journal of Hospitality Management 2022, 102, 103177. [CrossRef]

- Adnan, N.B.B.; Dafny, H.A.; Baldwin, C.; Jakimowitz, S.; Chalmers, D.; Aroury, A.M.A.; Chamberlain, D. What Are the Solutions for Well-Being and Burn-out for Healthcare Professionals? An Umbrella Realist Review of Learnings of Individual-Focused Interventions for Critical Care. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e060973. [CrossRef]

- Maresca, G.; Corallo, F.; Catanese, G.; Formica, C.; Lo Buono, V. Coping Strategies of Healthcare Professionals with Burnout Syndrome: A Systematic Review. Medicina 2022, 58, 327. [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Flow: A Component of the Good Life. In Positive psychology: an international perspective; Kostić, A., Chadee, D., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, 2021; pp. 193–201 ISBN 978-1-119-66644-8.

- Engeser, S.; Schiepe-Tiska, A.; Peifer, C. Historical Lines and an Overview of Current Research on Flow. In Advances in Flow Research; Peifer, C., Engeser, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; pp. 1–29 ISBN 978-3-030-53467-7.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Beyond Boredom and Anxiety; The Jossey-Bass behavioral science series; 1st ed.; Jossey-Bass Publishers: San Francisco, 1975; ISBN 978-0-87589-261-0.

- Steimer, S. UChicago News. October 28 2021. Available online: https://news.uchicago.edu/story/mihaly-csikszentmihalyi-pioneering-psychologist-and-father-flow-1934-2021 (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Pelly, D.; Daly, M.; Delaney, L.; Doyle, O. Worker Stress, Burnout, and Wellbeing Before and During the COVID-19 Restrictions in the United Kingdom. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 823080. [CrossRef]

- Pincus, J.D. Employee Engagement as Human Motivation: Implications for Theory, Methods, and Practice. Integr. psych. behav. 2023, 57, 1223–1255. [CrossRef]

- PRISMA PRISMA for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR). PRISMA 2020 2024. Available online: https://www.prisma-statement.org/scoping (accessed on 7 September 2024).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, n71. [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated Methodological Guidance for the Conduct of Scoping Reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Khalil, H.; Larsen, P.; Marnie, C.; Pollock, D.; Tricco, A.C.; Munn, Z. Best Practice Guidance and Reporting Items for the Development of Scoping Review Protocols. JBI Evidence Synthesis 2022, 20, 953–968. [CrossRef]

- PRISMA PRISMA 2020 Statement. PRISMA 2024. Available online: https://www.prisma-statement.org/prisma-2020 (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Smith, S.A.; Duncan, A.A. Systematic and Scoping Reviews: A Comparison and Overview. Seminars in Vascular Surgery 2022, 35, 464–469. [CrossRef]

- Gusenbauer, M.; Haddaway, N.R. Which Academic Search Systems Are Suitable for Systematic Reviews or Meta-analyses? Evaluating Retrieval Qualities of Google Scholar, PubMed, and 26 Other Resources. Research Synthesis Methods 2020, 11, 181–217. [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018, 169, 467–473. [CrossRef]

- Neal, T.M.S.; Lienert, P.; Denne, E.; Singh, J.P. A General Model of Cognitive Bias in Human Judgment and Systematic Review Specific to Forensic Mental Health. Law and Human Behavior 2022, 46, 99–120. [CrossRef]

- Fernández Pinto, M. Methodological and Cognitive Biases in Science: Issues for Current Research and Ways to Counteract Them. Perspectives on Science 2023, 31, 535–554. [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Cole, S.R.; Howe, C.J.; Westreich, D. Toward a Clearer Definition of Selection Bias When Estimating Causal Effects. Epidemiology 2022, 33, 699–706. [CrossRef]

- Infante-Rivard, C.; Cusson, A. Reflection on Modern Methods: Selection Bias—a Review of Recent Developments. International Journal of Epidemiology 2018, 47, 1714–1722. [CrossRef]

- Gusenbauer, M. Google Scholar to Overshadow Them All? Comparing the Sizes of 12 Academic Search Engines and Bibliographic Databases. Scientometrics 2019, 118, 177–214. [CrossRef]

- Healey, M.; Healey, R.L. Searching the Literature on Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL): An Academic Literacies Perspective: Part 1. TLI 2023, 11. [CrossRef]

- Al Eid, N.A.; Arnout, B.A.; Al-Qahtani, T.A.; Farhan, N.D.; Al Madawi, A.M. Psychological Flow and Mental Immunity as Predictors of Job Performance for Mental Health Care Practitioners during COVID-19. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0311909. [CrossRef]

- Choe, N.S.; Yelle, M. Building Nurse Resilience Through Art Therapy and Narrative Medicine Integration. Art Therapy 2025, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Lang, J.J.; Yang, L.F.; Cheng, C.; Cheng, X.Y.; Chen, F.Y. Are Algorithmically Controlled Gig Workers Deeply Burned out? An Empirical Study on Employee Work Engagement. BMC Psychol 2023, 11, 354. [CrossRef]

- George, E.S.; Antony, J.M.; Wesley, M.S. Positive Coping and Well-Being of Corporate Professionals during the Covid-19 Pandemic: A Single Case Study. Journal of Positive School Psychology 2022, 6, 5189–5194.

- Perold, I.; Knott, B.; Young, C. The COVID-19 Pandemic’s Effect on Family Leisure Activities of Working Parents with Pre-School Aged Children. World Leisure Journal 2024, 66, 267–290. [CrossRef]

- Bykov, K.V.; Zrazhevskaya, I.A.; Topka, E.O.; Peshkin, V.N.; Dobrovolsky, A.P.; Isaev, R.N.; Orlov, A.M. Prevalence of Burnout among Psychiatrists: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders 2022, 308, 47–64. [CrossRef]

- Załuski, M.; Makara-Studzińska, M. Latent Occupational Burnout Profiles of Working Women. IJERPH 2022, 19, 6525. [CrossRef]

- Hajiheydari, N.; Delgosha, M.S. Investigating Engagement and Burnout of Gig-Workers in the Age of Algorithms: An Empirical Study in Digital Labor Platforms. ITP 2024, 37, 2489–2522. [CrossRef]

- Lam, L.T.; Lam, M.K.; Reddy, P.; Wong, P. Factors Associated with Work-Related Burnout among Corporate Employees Amidst COVID-19 Pandemic. IJERPH 2022, 19, 1295. [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M.E.P. Positive Psychology: A Personal History. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2019, 15, 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Chisale, E.T.; Phiri, F.M. PERMA Model and Mental Health Practice. Asian Journal of Pharmacy, Nursing and Medical Sciences 2022, 10, 21–24.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).