Submitted:

14 March 2025

Posted:

17 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Historical Context of Sustainability

2.2. Ownership Structure

2.3. Board Composition

2.4. Gender Diversity on Boards

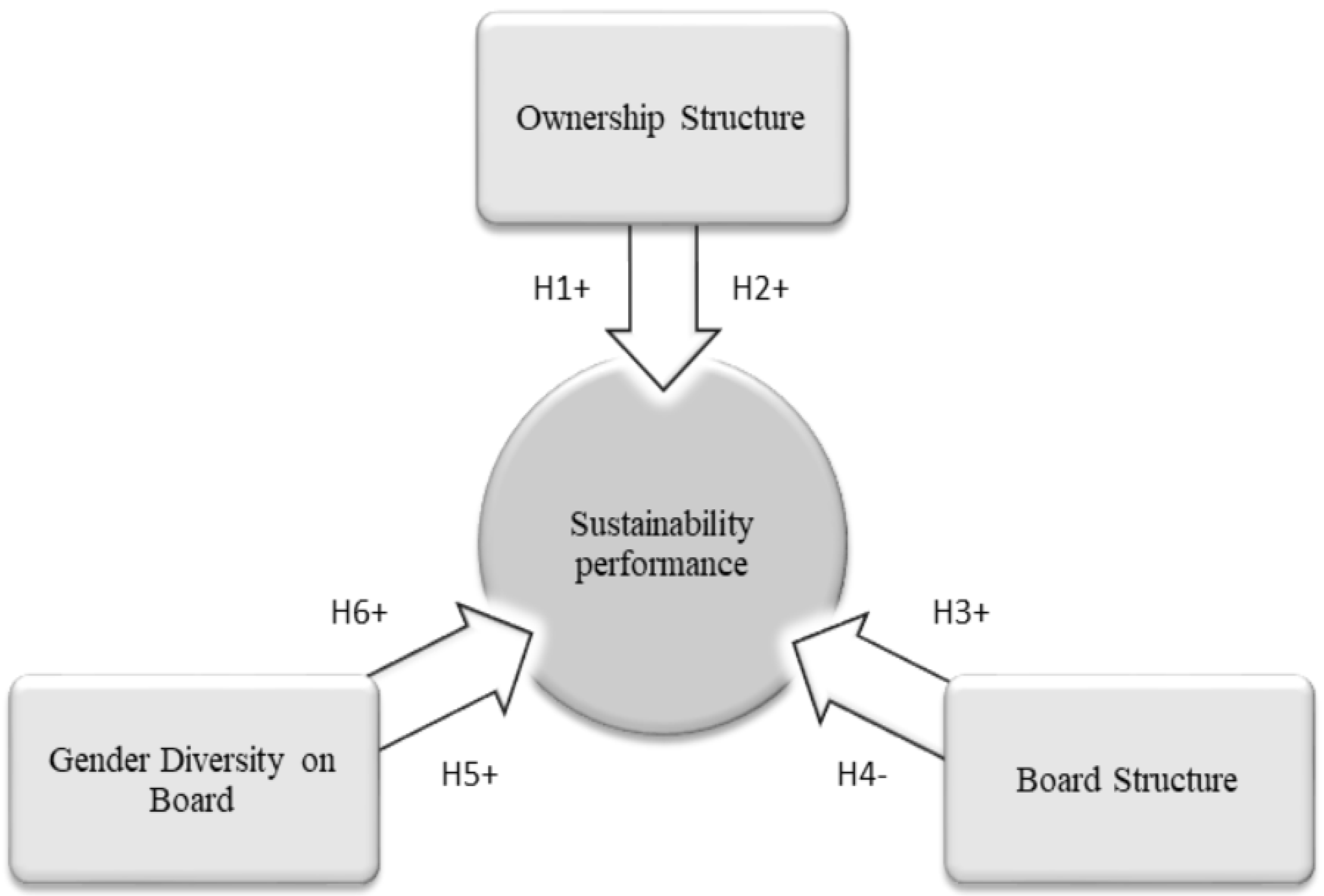

2.5. Structural Model and Distribution of Hypotheses

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Dependent Variable

3.2. Independent Variables

3.3. Control Variables

3.4. Econometric Models

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Main Results and Discussions

5. Conclusions

References

- Abdullah, S.N.; Ismail, K.N.I.K.; Nachum, L. Does Having Women on Boards Create Value? The Impact of Societal Perceptions and Corporate Governance in Emerging Markets. Strateg. Manag. J. 2016, 37, 466–476. [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, R.V.; Aragón-Correa, J.A.; Marano, V.; Tashman, P.A. The Corporate Governance of Environmental Sustainability: A Review and Proposal for More Integrated Research. J. Manag. 2021, 47, 1468–1497. [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, M.; Yilmaz, M.K.; Tatoglu, E.; Basar, M. Antecedents of Corporate Sustainability Performance in Turkey: The Effects of Ownership Structure and Board Attributes on Non-Financial Companies. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 276, 124284. [CrossRef]

- ISE_B3. Índice de Sustentabilidade Empresarial (ISE B3): Índice de Sustentabilidade Empresarial. 2024. Available online: https://www.b3.com.br/pt_br/market-data-e-indices/indices/indices-de-sustentabilidade/indice-de-sustentabilidade-empresarial-ise-b3.htm.

- Barros, T.D.S.; Kirschbaum, C. Qual a Posição das Mulheres na Rede de Board Interlocking do Brasil? Uma Análise para o Período de 1997 a 2015. Rev. Adm. Empresas 2023, 63. [CrossRef]

- Borghesi, R.; Houston, J.F.; Naranjo, A. Corporate Socially Responsible Investments: CEO Altruism, Reputation, and Shareholder Interests. J. Corp. Finance 2014, 26, 164–181. [CrossRef]

- Burton, I. Report on Reports: Our Common Future. Environ. Sci. Policy Sustain. Dev. 1987, 29, 25–29. [CrossRef]

- Cezarino, L.O.; de Queiroz Murad, M.; Resende, P.V.; Sales, W.F. Being Green Makes Me Greener? An Evaluation of Sustainability Rebound Effects. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 269, 121436. [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Dong, H.; Lin, C. Institutional Shareholders and Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Financ. Econ. 2020, 135, 483–504. [CrossRef]

- Chu, H.L.; Liu, N.Y.; Chiu, S.C. CEO Power and CSR: The Moderating Role of CEO Characteristics. China Account. Finance Rev. 2023, 25, 101–121. [CrossRef]

- Clark, G.L.; Feiner, A.; Viehs, M. From the Stockholder to the Stakeholder: How Sustainability Can Drive Financial Outperformance. SSRN Working Paper 2508281, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Correa-Garcia, J.A.; Garcia-Benau, M.A.; Garcia-Meca, E. Corporate Governance and Its Implications for Sustainability Reporting Quality in Latin American Business Groups. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 260, 121142. [CrossRef]

- Dobija, D.; Hryckiewicz, A.; Zaman, M.; Puławska, K. Critical Mass and Voice: Board Gender Diversity and Financial Reporting Quality. Eur. Manag. J. 2022, 40, 29–44. [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R.G.; Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. The Impact of Corporate Sustainability on Organizational Processes and Performance. Manag. Sci. 2012, 60, 2835–2857. [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Partnerships from Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st-Century Business. Environ. Qual. Manag. 1998, 8, 37–51. [CrossRef]

- Fama, E.F.; Jensen, M.C. Separation of Ownership and Control. SSRN Electron. J. 1983, 26, 301–325. [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E.; Reed, D.L. Stockholders and Stakeholders: A New Perspective on Corporate Governance. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1983, 25, 88–106. [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Tang, T.; Yan, X. Why Do Institutions Like Corporate Social Responsibility Investments? Evidence from Horizon Heterogeneity. J. Empir. Finance 2019, 51, 44–63. [CrossRef]

- García-Martín, C.J.; Herrero, B. Do Board Characteristics Affect Environmental Performance? A Study of EU Firms. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 74–94. [CrossRef]

- Guenster, N.; Bauer, R.; Derwall, J.; Koedijk, K. The Economic Value of Corporate Eco-Efficiency. Eur. Financ. Manag. 2011, 17, 679–704. [CrossRef]

- Konrad, A.M.; Kramer, V.; Erkut, S. The Impact of Three or More Women on Corporate Boards. Organ. Dyn. 2008, 37, 145–164. [CrossRef]

- Kuhlman, T.; Farrington, J. What Is Sustainability? Sustainability 2010, 2, 3436–3448. [CrossRef]

- Lameira, V.D.J.; Ness Jr, W.L.; Quelhas, O.L.G.; Pereira, R.G. Sustentabilidade, Valor, Desempenho e Risco no Mercado de Capitais Brasileiro. Rev. Bras. Gest. Negócios 2013, 15, 76–90. Available online: https://www.scielo.br/j/rbgn/a/98GmMjzrhWjJG9jGVbR38QL/?format=pdf&lang=pt.

- Lee, B.X.; Kjaerulf, F.; Turner, S.; Cohen, L.; Donnelly, P.D.; Muggah, R.; Davis, R.; Realini, A.; Kieselbach, B.; MacGregor, L.S.; Waller, I.; Gordon, R.; Moloney-Kitts, M.; Lee, G.; Gilligan, J. Transforming Our World: Implementing the 2030 Agenda Through Sustainable Development Goal Indicators. J. Public Health Policy 2016, 37(S1), 13–31. [CrossRef]

- Maida, A.; Weber, A. Female Leadership and Gender Gap within Firms: Evidence from an Italian Board Reform. ILR Rev. 2022, 75, 488–515. [CrossRef]

- Med Bechir, C.; Jouirou, M. Investment Efficiency and Corporate Governance: Evidence from Asian Listed Firms. J. Sustain. Finance Invest. 2024, 14, 596–618. [CrossRef]

- Naciti, V. Corporate Governance and Board of Directors: The Effect of a Board Composition on Firm Sustainability Performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 237, 117727. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.H.H.; Ntim, C.G.; Malagila, J.K. Women on Corporate Boards and Corporate Financial and Non-Financial Performance: A Systematic Literature Review and Future Research Agenda. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2020, 71, 101554. [CrossRef]

- Orellano, V.I.F.; Quiota, S. Análise do Retorno dos Investimentos Socioambientais das Empresas Brasileiras. Rev. Adm. Empresas 2011, 51, 471–484. Available online: https://www.scielo.br/j/rae/a/ct34Twsnw3WYg9yN4ZdfdQs/abstract/?lang=pt.

- Qureshi, M.A.; Kirkerud, S.; Theresa, K.; Ahsan, T. The Impact of Sustainability (Environmental, Social, and Governance) Disclosure and Board Diversity on Firm Value: The Moderating Role of Industry Sensitivity. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2019, 29, 1199–1214. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.D.D.; Funchal, B. Fatores Determinantes na Incorporação das Organizações ao ISE. Base Rev. Adm. Contab. UNISINOS 2018, 15, 31–41. [CrossRef]

- Robert, K.W.; Parris, T.M.; Leiserowitz, A.A. What Is Sustainable Development? Goals, Indicators, Values, and Practice. Environ. Sci. Policy Sustain. Dev. 2005, 47, 8–21. [CrossRef]

- Romano, M.; Cirillo, A.; Favino, C.; Netti, A. ESG (Environmental, Social and Governance) Performance and Board Gender Diversity: The Moderating Role of CEO Duality. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9298. [CrossRef]

- Sant’Ana, N.L.D.S.; Medeiros, N.C.D.D.; Silva, S.A.D.L.; Menezes, J.P.C.B.; Chain, C.P. Concentração de Propriedade e Desempenho: Um Estudo nas Empresas Brasileiras de Capital Aberto do Setor de Energia Elétrica. Gest. Prod. 2016, 23, 718–732. Available online: https://www.scielo.br/j/gp/a/pD4cpfndVWZYCMB6Yqqhfhx/abstract/?lang=pt.

- Schoenmaker, D. Investing for the Common Good: A Sustainable Finance Framework; Bruegel: Brussels, 2017; p. 80. Available online: https://aei.pitt.edu/88435/1/From-traditional-to-sustainable-finance_ONLINE.pdf.

- Shakil, M.H.; Tasnia, M.; Mostafiz, M.I. Board Gender Diversity and Environmental, Social and Corporate Governance Performance of US Banks: Moderating Role of Environmental, Social and Corporate Governance Controversies. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2021, 39, 661–677. [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, E.A.; Nossa, V.; Funchal, B. O Índice de Sustentabilidade Empresarial (ISE) e os Impactos no Endividamento e na Percepção de Risco. Rev. Contab. Fin. 2011, 22, 29–44. Available online: https://www.scielo.br/j/rcf/a/Npy4byt4mpTnHbnw4Yy6zLw/?format=pdf&lang=pt.

- United Nations, D.L. Agenda 21: Programme of Action for Sustainable Development, Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, Statement of Forest Principles: The Final Text of Agreements Negotiated by Governments at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), 3–14 June 1992, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Digital Library UN 1993. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/170126.

- Valls Martínez, M.D.C.; Martin Cervantes, P.A.; Cruz Rambaud, S. Women on Corporate Boards and Sustainable Development in the American and European Markets: Is There a Limit to Gender Policies? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 2642–2656. [CrossRef]

- Zalata, A.M.; Ntim, C.G.; Alsohagy, M.H.; Malagila, J. Gender Diversity and Earnings Management: The Case of Female Directors with Financial Background. Rev. Quant. Finance Account. 2022, 58, 101–136. [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, A.; Schröder, M. What Determines the Inclusion in a Sustainability Stock Index? A Panel Data Analysis for European Firms. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 848–856. [CrossRef]

- Zournatzidou, G.; Ragazou, K.; Sklavos, G.; Sariannidis, N. Examining the Impact of Environmental, Social, and Corporate Governance Factors on Long-Term Financial Stability of the European Financial Institutions: Dynamic Panel Data Models with Fixed Effects. Int. J. Financ. Stud. 2025, 13, 3. [CrossRef]

| Hypotheses | Expected sign | |

| H1 | There is a positive association between foreign ownership and sustainability performance. | + |

| H2 | The greater the organizational maturity, the higher the sustainability performance. | + |

| H3 | The composition of independent members has a positive influence on sustainability performance. | + |

| H4 | CEO duality is negatively associated with sustainability performance. | - |

| H5 | There is a positive association between the presence of women on the board and sustainability performance. | + |

| H6 | An increase in the number of women on the board has a positive impact on sustainability performance. | + |

| Variable | Division | Acronyms | Description |

| Dependent | Sustainability Index | ISE | Dummy for Sustainability (ISE) |

| Independent | Ownership Structure | PES; PTN; PIN | Logarithms of foreign, traded, and institutional ownership. |

| Organizational Maturity | MAO1 - MAO6 | Dummies for organizational maturity (20-year intervals). | |

| Board Members | MIC; MCIF, TAC | Proportion of independent members and women on independent boards. | |

| CEO Duality | DCE | Dummy for CEO duality. | |

| Female Representation | TMCF1 - TMCF4 | Dummies for one, two, three, or more women on the board. | |

| Control | Economic-Financial Variables | ATI; QTB; ALF; SET; ANO | Logarithm of total assets, Tobin’s Q, financial leverage, sector, and year. |

| Variable | Description | Mean | Median | Stand. Dev. | Max | Min |

| 1. ISE | Sustainability Index | 0.04 | 0 | 0.21 | 1 | 0 |

| 2. PES | Log of foreign | 4.71 | 4.59 | 0.87 | 8.0 | 3.1 |

| 3. PIN | Log of institutional | 4.67 | 4.59 | 0.77 | 5.1 | -4.6 |

| 4. PTN | Log of publicly traded | 4.92 | 5.08 | 1.06 | 9.6 | 1.3 |

| 5. MAO1 | Maturity from 1 to 20 | 0.36 | 0 | 0.48 | 1 | 0 |

| 6. MAO2 | Maturity from 21 to 40 | 0.20 | 0 | 0.40 | 1 | 0 |

| 7. MAO3 | Maturity from 41 to 60 | 0.19 | 0 | 0.39 | 1 | 0 |

| 8. MAO4 | Maturity from 61 to 80 | 0.13 | 0 | 0.34 | 1 | 0 |

| 9. MAO5 | Maturity from 81 to 100 | 0.05 | 0 | 0.22 | 1 | 0 |

| 10. MAO6 | Maturity over 100 years | 0.06 | 0 | 0.23 | 1 | 0 |

| 11. MIC | Independent members on the board | 0.18 | 0 | 0.30 | 1.1 | 0 |

| 12. MCIF | Women on the independent board | 0.02 | 0 | 0.06 | 0.7 | 0 |

| 13. DCE | CEO duality | 0.22 | 0 | 0.41 | 1 | 0 |

| 14. TAC | Total members board | 3.02 | 0 | 3.65 | 15 | 0 |

| 15. TMCF1 | One woman board | 0.07 | 0 | 0.25 | 1 | 0 |

| 16. TMCF2 | Two women board | 0.02 | 0 | 0.15 | 1 | 0 |

| 17. TMCF3 | Three women board | 0.01 | 0 | 0.09 | 1 | 0 |

| 18. TMCF4 | More than three women | 0.00 | 0 | 0.03 | 1 | 0 |

| 19. ATI | Log of total assets | 6.25 | 6.37 | 1.03 | 9.11 | -1.2 |

| 20. QTB | Tobin’s Q | 0.38 | 0.00 | 2.14 | 59.03 | -1.4 |

| 21. ALF | Financial leverage | 0.82 | 0.60 | 2.29 | 55.50 | 0.00 |

| Independent variables | Model 1. | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ||

| PES (Foreign ownership) | -1.037** | -1.871** | |||||||

| PIN (Institutional ownership) | 0.097 | 0.160 | |||||||

| PTN (Public ownership) | -1.673** | -2.784** | |||||||

| MAO1 (Maturity 1-20 years) | -0.422** | -0.880** | |||||||

| MAO2 (Maturity 21-40 years) | -0.003 | 0.067 | |||||||

| MAO3 (Maturity 41-60 years) | -0.276* | -0.470 | |||||||

| MAO4 (Maturity 61-80 years) | -0.921*** | -1.876*** | |||||||

| MAO5 (Maturity 81-100 years) | 0.185 | 0.132 | |||||||

| MIC (Independent board members) | 0.144 | 0.348 | |||||||

| MCIF (Female independent board) | 1.442** | 2.542** | |||||||

| DCE (CEO duality) | -0.182 | -0.252 | |||||||

| TAC (Board size) | 0.061*** | 0.120*** | |||||||

| TMCF1(One woman on board) | 0.473*** | 0.926*** | |||||||

| TMCF2 (Two women on board) | 1.144*** | 2.094*** | |||||||

| TMCF3 (Three women on board) | 0.608** | 1.169** | |||||||

| QTB (Tobin’s Q) | -0.645 | -1.008 | 0.129*** | 0.242*** | 0.122*** | 0.233*** | 0.105*** | 0.199*** | |

| ATI (Log of total assets) | 2.942*** | 5.085*** | 1.480*** | 2.764*** | 1.155*** | 2.175*** | 1.077*** | 2.229*** | |

| ALF (Financial leverage) | -3.007** | -5.315** | -0.041 | -0.105 | -0.097 | -0.239 | -0.033 | -0.074 | |

| Teste Wald | 34.79** | 28.08** | 349.28*** | 332.85*** | 281.73*** | 236.23*** | 318.00*** | 299.01*** | |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.30 | 0.31 | 0.37 | 0.36 | 0.38 | 0.36 | 0.39 | 0.37 | |

| Teste HL | 0.64 | 0.94 | 0.69 | 0.36 | 0.23 | 0.87 | 0.14 | 0.04 | |

| Structures | Hypotheses | Expected Sign | Observed Sign | Results | |

| Ownership Structure | H1 | There is a positive association between foreign ownership and sustainability performance. | + | - | Not supported |

| H2 | The greater the organizational maturity, the higher the sustainability performance. | + | - | Not supported | |

| Board Structure | H3 | The composition of independent members has a positive influence on sustainability performance. | + | + | Supported |

| H4 | CEO duality is negatively associated with sustainability performance. | - | - | Not supported | |

| Gender Diversity on Board | H5 | There is a positive association between the presence of women on the board and sustainability performance. | + | + | Supported |

| H6 | An increase in the number of women on the board has a positive impact on sustainability performance. | + | + | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).