Submitted:

15 March 2025

Posted:

17 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

An efficient method for efficiently cleaning pharmaceutical wastewater and eliminating micro-contaminants is the production of hydrochar from coal waste and sewage sludge using hydrothermal carbonization (HTC) techniques. This procedure produces high-quality hydrochar, a potential adsorbent material for pharmaceutical wastewater treatment, by carefully converting coal waste and sewage sludge in proportions. This novel approach dramatically lowers the dangers to environmental health posed by excessive pharmaceutical pollutants. Essential elements include reaction temperature, reaction duration, feedstock qualities, pressure, total solids, solvents, catalyst composition, and a host of other biochemical and physicochemical parameters that all affect the quality of the hydrochar generated during HTC. To effectively remove pharmaceutical wastewater pollutants and lessen environmental concerns, this paper carefully reviews the use of hydrochar, an adsorbent made from particular ratios of sewage sludge (SS) and coal waste (CW).

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- To thoroughly review the effectiveness of hydrochar derived from the combined use of sewage sludge and coal waste in removing pharmaceutical contaminants from wastewater.

- It identifies critical factors affecting operational conditions, including reaction temperature, catalyst selection, and coal waste and sewage sludge mass ratios while examining hydrochar composition and characteristics.

2. Main Text

2.1. Coal Waste and Sewage Sludge Treatment

2.1.1. Coal as an Adsorbent Material

2.2. Sewage Sludge Treatment

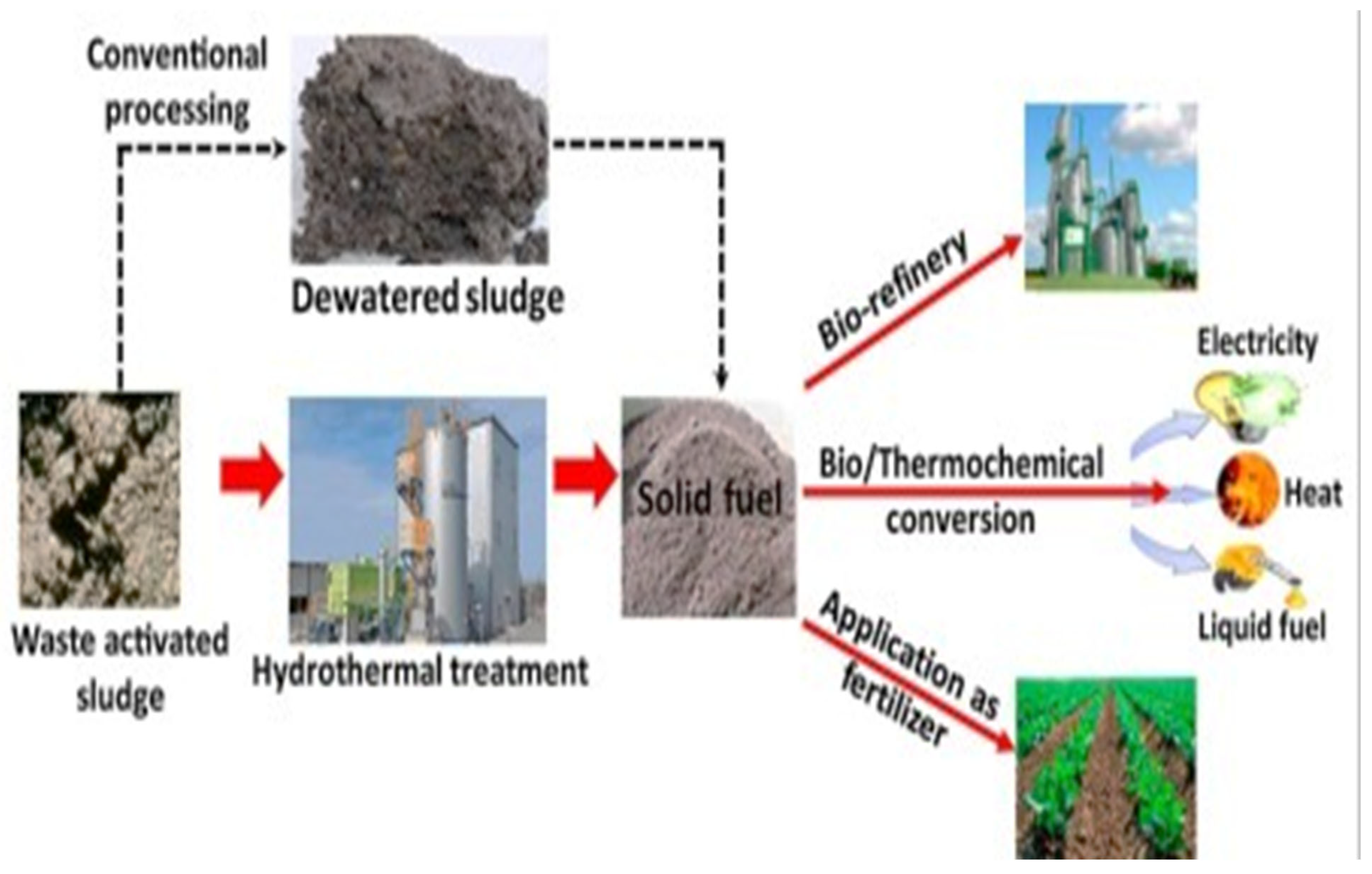

2.2.1. Hydrothermal Modification of Sewage Sludge

2.2.2. Biomass Transformation to Hydrochar via HTC

2.2.3. Treatment of Sewage Sludge, Operating Conditions, and Benefits

2.2.4. Hydrothermal Processing of Coal Waste

2.3. HTC Treatment of Sewage Sludge Mixed with Coal Waste

2.3.1. HTC Parameters

2.4. Advantages of Hydrothermal Carbonization

2.5. Pyrolysis and Hydrothermal Carbonization in Waste Treatment

2.5. Theory and Discussion

3. Conclusions

List of Abbreviations

| HTC | hydrothermal carbonisation |

| SS | sewage sludge |

| CW | coal waste |

| SA | South Africa |

| wt/wt | weight per weight |

| wt% | weight percentage |

| WWTP | wastewater treatment plant |

| °C | degree Celsius |

| HC | hydrochar |

| CO2 | carbon dioxide |

| HHV | high heating value |

| MPa | Mega Pascal |

| AC | activated carbon |

| Co-HTC | co-hydrothermal carbonisation |

| CM | Carbon material |

| CW | carbonised waste |

| 5-HMF | 5-hydroxymethylfurfural |

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdulsalam, J.; Mulopo, J.; Oboirien, B.; Bada, S.; Falcon, R. Experimental evaluation of activated carbon derived from South Africa’s discarded coal for natural gas storage. International Journal of Coal Science & Technology 2019, 6(3), 459–477. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulsalam, J.; Onifade, M.; Bada, S.; Mulopo, J.; Genc, B. The spontaneous combustion of chemically activated carbons from South African coal waste. Combustion Science and Technology 2022, 194(10), 2025–2041. [Google Scholar]

- Afolabi, O.O.; Sohail, M.; Cheng, Y.L. Optimisation and characterisation of hydrochar production from spent coffee grounds by hydrothermal carbonisation. Renewable Energy 2020, 147, 1380–1391. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadpour, A.; Do, D.D. The preparation of active carbons from coal by chemical and physical activation. Carbon 1996, 34(4), 471–479. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, M.B.; Johir, M.A.H.; Zhou, J.L.; Ngo, H.H.; Nghiem, L.D.; Richardson, C.; Moni, M.A.; Bryant, M.R. Activated carbon preparation from biomass feedstock: clean production and carbon dioxide adsorption. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 225, 405–413. [Google Scholar]

- Aliakbari, Z.; Younesi, H.; Ghoreyshi, A. A.; Bahramifar, N.; Heidari, A. Production and characterisation of sewage-sludge-based activated carbons under different post-activation conditions. Waste and biomass valorisation 2018, 9(3), 451–463. [Google Scholar]

- Aragón-Briceño, C.I.; Ross, A.B.; Camargo-Valero, M.A. Mass and energy integration study of hydrothermal carbonisation with anaerobic digestion of sewage sludge. Renewable Energy 2021, 167, 473–483. [Google Scholar]

- Archer, E. The fate of pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs), endocrine disrupting contaminants (EDCs), metabolites and illicit drugs in a WWTW and environmental waters. Chemosphere 2017, 174, 437–446. [Google Scholar]

- Asvat, R.; Bischoff, C.A.; Botha, C.J. Factors to measure the performance of private business schools in South Africa. Journal of Economics and Behavioral Studies 2018, 10(6 (J)), 50–69. [Google Scholar]

- Azadi, P.; Afif, E.; Foroughi, H.; Dai, T.; Azadi, F.; Farnood, R. Catalytic reforming of activated sludge model compounds in supercritical water using nickel and ruthenium catalysts. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2013, 134, 265–273. [Google Scholar]

- Baig, K.S. Interaction of enzymes with lignocellulosic materials: causes, mechanism, and influencing factors. Bioresources and bioprocessing 2020, 7(1), 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Bardestani, R.; Patience, G.S.; Kaliaguine, S. Experimental methods in chemical engineering: specific surface area and pore size distribution measurements BET, BJH, and DFT. The Canadian Journal of Chemical Engineering 2019, 97(11), 2781–2791. [Google Scholar]

- Barghi, B. Process optimisation for catalytic oxidation of dibenzothiophene over UiO-66-NH2 by using a response surface methodology. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 16288–16297. [Google Scholar]

- Bedin, K.C.; Cazetta, A.L.; Souza, I.P.; Pezoti, O.; Souza, L.S.; Souza, P.S.; Yokoyama, J.T.; Almeida, V.C. Porosity enhancement of spherical activated carbon: Influence and Optimisation of hydrothermal synthesis conditions using response surface methodology. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2018, 6(1), 991–999. [Google Scholar]

- Bentsen, S.N.; Felby, C. Technical potentials of biomass for energy services from current agriculture and forestry in selected countries in Europe, The Americas, and Asia; N. p.: Denmark: N. p; Denmark, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bertanza, G.; Collivignarelli, C.; Pedrazzani, R. The Role of Chemical Oxidation in Combined Chemical-Physical and Biological Processes: Experiences of Industrial Wastewater Treatment. Water Science and Technology 2001, 44, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bi, P., Zhang, M., Li, S., Lu, H., Wang, H., Liang, X., Liang, H. & Zhang, Y. (2022). Ultra-sensitive and widely applicable strain sensors enabled by carbon nanofibers with dual alignment for human-machine interfaces. Nano Research.

- Bohlmann, J.A.; Inglesi-Lotz, R. Analysing the South African residential sector’s energy profile. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2018, 96, 240–252. [Google Scholar]

- Borowski, G.; Alsaqoor, S.; Alahmer, A. Using agglomeration techniques for coal and ash waste management in the circular economy. Advances in Science and Technology. Research Journal 2021, 15(3). [Google Scholar]

- Breulmann, M.; Schulz, E.; van Afferden, M.; Müller, R.A.; Fühner, C. Hydrochar derived from sewage sludge: effects of pre-treatment with water on char properties, phytotoxicity, and chemical structure. Archives of Agronomy and Soil Science 2018, 64(6), 860–872. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Liu, G.; Kang, Y.; Wu, B.; Sun, R.; Zhou, C.; Wu, D. Coal utilisation in China: environmental impacts and human health. Environmental Geochemistry and Health 2014, 36(4), 735–753. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, X.; Lu, M.; Khan, M.B.; Lai, C.; Yang, X.; He, Z.; Chen, G.; Yan, B. Hydrothermal carbonisation of different wetland biomass wastes: Phosphorus reclamation and hydrochar production. Waste Management 2020, 102, 106–113. [Google Scholar]

- Danso-Boateng, E.; Holdich, R.G.; Shama, G.; Wheatley, A.D.; Sohail, M.; Martin, S.J. Kinetics of faecal biomass hydrothermal carbonisation for hydrochar production. Applied Energy 2013, 111, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Reis, G.S.; Bin Mahbub, M.K.; Wilhelm, M.; Lima, E.C.; Sampaio, C.H.; Saucier, C.; Pereira Dias, S.L. Activated carbon from sewage sludge for removal of sodium diclofenac and nimesulide from aqueous solutions. Korean Journal of Chemical Engineering 2016, 33(11), 31493161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Đurđević, D.; Blecich, P.; Jurić, Ž. Energy recovery from sewage sludge: the case study of Croatia. Energies 2019, 12(10), 1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakkaew, K.; Koottatep, T.; Pussayanavin, T.; Polprasert, C. Faecal sludge treatment and utilisation by hydrothermal carbonisation. Journal of Environmental and Management 2018, 216, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funke, A.; Ziegler, F. Hydrothermal carbonisation of biomass: A summary and discussion of chemical mechanisms for process engineering. Biofuels, Bioproducts and Biorefining 2010, 4, 160–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gani, K.M.; Hlongwa, N.; Abunama, T.; Kumari, S.; Bux, F. Emerging contaminants in South African water environment-a critical review of their occurrence, sources, and ecotoxicological risks. Chemosphere 2021, 269, 128737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, N.; Kamran, K.; Quan, C.; Williams, P.T. Thermochemical conversion of sewage sludge: A critical review. Progress in Energy and Combustion Science 2020, 79, 100843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, M.; Nanda, S.; Romero, M.J.; Zhu, W.; Kozinski, J.A. Subcritical and supercritical water gasification of humic acid as a model compound of humic substances in sewage sludge. The Journal of Supercritical Fluids 2017, 119, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, H.B.; Diptendu, S.; Saxena, R.C. Biofuels from thermochemical conversion of renewable resources: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Review, Elsevier 2008, 12(2), 504–517. [Google Scholar]

- Grobelak, A.; Grosser, A.; Kacprzak, M.; Kamizela, T. Sewage sludge processing and management in small and medium-sized municipal wastewater treatment plant-new technical solution. Journal of Environmental Management 2019, 234, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwenzi, W.; Chaukura, N. Organic contaminants in African aquatic systems: Current knowledge, health risks, and future research directions. Science of Total Environment 2018, 619, 1493–1514. [Google Scholar]

- Heidari, M.; Salaudeen, S.; Dutta, A.; Acharya, B. Effects of process water recycling and particle sizes on hydrothermal carbonisation of biomass. Energy & fuels 2018, 32(11), 11576–11586. [Google Scholar]

- Heinemann, N.; Alcalde, J.; Miocic, J.M.; Hangx, S.J.; Kallmeyer, J.; Ostertag-Henning, C.; Hassanpouryouzband, A.; Thaysen, E.M.; Strobel, G.J.; Schmidt-Hattenberger, C.; Edlmann, K. Enabling large-scale hydrogen storage in porous media–the scientific challenges. Energy & Environmental Science 2021, 14(2), 853–864. [Google Scholar]

- Hernando, M. D.; Mezcua, M.; Fernández-Alba, A. R.; Barceló, D. Environmental Risk Assessment of Pharmaceutical Residues in Wastewater Effluents, Surface Waters and Sediments. Talanta 2006, 334–342. [Google Scholar]

- Hitzl, M.; Corma, A.; Pomares, F.; Renz, M. The hydrothermal carbonisation (HTC) plant as a decentral biorefinery for wet biomass. Catalyst Today 2015, 257, 154–159. [Google Scholar]

- Hlangwani, E.; Doorsamy, W.; Adebiyi, J.A.; Fajimi, L.I.; Adebo, O.A. A modelling method for the development of a bioprocess to optimally produce umqombothi (a South African traditional beer). Scientific Reports 2021, 11(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Hoekman, S.K.; Broch, A.; Robbins, C. Hydrothermal carbonisation (HTC) of lignocellulosic biomass. Energy & Fuels 2011, 25(4), 1802–1810. [Google Scholar]

- Hoekman, S.K.; Broch, A.; Robbins, C.; Zielinska, B.; Felix, L. Hydrothermal carbonisation (HTC) of selected woody and herbaceous biomass feedstocks. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery 2013, 3(2), 113–126. [Google Scholar]

- Hovland, M.; Rueslåtten, H.; Johnsen, H.K. Large salt accumulations as a consequence of hydrothermal processes associated with ’Wilson cycles’: A review, Part 2: Application of a new salt-forming model on selected cases. Marine and Petroleum Geology 2018, 92, 128–148. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, B.; Wang, K.; Wu, L.; Yu, S.H.; Antonietti, M.; Titirici, M.M. Engineering carbon materials from the hydrothermal carbonisation process of biomass. Advanced materials 2010, 22(7), 813–828. [Google Scholar]

- Imbierowicz, M.; Chacuk, A. Kinetic model of excess activated sludge thermohydrolysis. Water Research 2012, 46(17), 5747–5755. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jain, A.; Balasubramanian, R.; Srinivasan, M.P. Hydrothermal conversion of biomass waste to activated carbon with high porosity: A review. Chemical Engineering Journal 2016, 283, 789–805. [Google Scholar]

- Kacprzak, M.; Neczaj, E.; Fijałkowski, K.; Grobelak, A.; Grosser, A.; Worwag, M.; Rorat, A.; Brattebo, H.; Almås, Å.; Singh, B.R. Sewage sludge disposal strategies for sustainable development. Environmental Research 2017, 156, 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Kacprzak, M.J.; Kupich, I. The specificities of the circular economy (CE) in the municipal wastewater and sewage sludge sector local circumstances in Poland. Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy 2021, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Kacprzak, M.J.; Kupich, I. The specificities of the circular economy (CE) in the municipal wastewater and sewage sludge sector—local circumstances in Poland. Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy 2021, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Kahilu, G. M.; Bada, S.; Mulopo, J. Physicochemical, structural analysis of coal discards (and sewage sludge) (co)-HTC derived biochar for a sustainable carbon economy and evaluation of the liquid by-product. In Scientific Reports; Kruse et al., 2022; Volume 12, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kahilu, G. M.; Bada, S.; Mulopo, J. Coal Discards and Sewage Sludge Derived-Hydrochar for HIV Antiretroviral Pollutant Removal from Wastewater and Spent Adsorption Residue Evaluation for Sustainable Carbon Management. Sustainability 2022a, 14(22), 15113. [Google Scholar]

- Kahilu, G. M., Bada, S., & Mulopo, J. (2023). Systematic physicochemical characterisation, carbon balance, and cost of production analyses of activated carbons derived from (Co)-HTC of coal discards and sewage sludge for hydrogen storage applications. Waste Disposal and Sustainable Energy.

- Kambo, H.S.; Dutta, A. Strength, storage, and combustion characteristics of densified lignocellulosic biomass produced via torrefaction and hydrothermal carbonisation. Applied Energy 2014, 135, 182–191. [Google Scholar]

- Kambo, H.S.; Dutta, A. A comparative review of biochar and hydrochar in terms of production, physico-chemical properties and applications. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2015, 45, 359–378. [Google Scholar]

- Karungamye, P.; Rugaika, A.; Mtei, K.; Machunda, R. The pharmaceutical disposal practices and environmental contamination: A review in East African countries. HydroResearch 2022, 5, 99–107. [Google Scholar]

- Keefer, R.F. Coal ashes industrial wastes or beneficial by-products? In Trace elements in coal and coal combustion residues(3–9); CRC Press, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Khanam, N.; Singh, A.A.; Singh, A.K.; Hamidi, M.K. Water quality characterisation of industrial and municipal wastewater, issues, challenges, health effects, and control techniques. In Recent Trends in Wastewater Treatment; Springer, Cham, 2022; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.; Yoshikawa, K.; Park, K.Y. Characteristics of biochar obtained by hydrothermal carbonisation of cellulose for renewable energy. Energies 2015, 8(12), 14040–14048. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.W.; Jang, H.S.; Kim, J.G.; Ishibashi, H.; Hirano, M.; Nasu, K.; Ichikawa, N.; Takao, Y.; Shinohara, R.; Arizono, K. Occurrence of pharmaceutical and personal care products (PPCPs) in surface water from Mankyung River, South Korea. Journal of Health Science 2009, 55, 249–258. [Google Scholar]

- Klavarioti, M.; Mantzavinos, D.; Kassinos, D. Removal of residual pharmaceuticals from aqueous systems by advanced oxidation processes. Environ. Int. 2009, 35, 402–417. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kruse, A.; Grandl, R. Hydrothermal carbonisation: 3. Kinetic model. Chemie Ingenieur Technik 2015, 87(4), 449–456. [Google Scholar]

- Krylova, A.Y.; Zaitchenko, V.M. Hydrothermal carbonisation of biomass: a review. Solid Fuel Chemistry 2018, 52(2), 91–103. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Samadder, S.R. A review on technological options of waste to Energy for effective management of municipal solid waste. Waste Management 2017, 69, 407–422. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A.; Oyedun, A.O.; Kumar, M. A review on the current status of various hydrothermal technologies on biomass feedstock. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews.–Elsevier 2018, 81(P2), 1742–1770. [Google Scholar]

- Kyzas, G.Z.; Kostoglou, M. Green Adsorbents for Wastewaters: A Critical Review. Materials 2014, 7, 333–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, D.G.J.; de Pedro, C.; Paxeus, N. Effluent from Drug Manufactures Contains Extremely High Levels of Pharmaceuticals. Journal of Hazardous Material 2007, 148, 751–755. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Dos Reis, A.A.; Ansari, A.; Bertelli, L.; Carr, Z.; Dainiak, N.; Degteva, M.; Efimov, A.; Kalinich, J.; Kryuchkov, V.; Kukhta, B. Public health response and medical management of internal contamination in past radiological or nuclear incidents: A narrative review. Environment International 2022, 107222. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Liu, X.; You, F.; Wang, P.; Feng, X.; Hu, Z. Pore Size Distribution Characterization by Joint Interpretation of MICP and NMR: A Case Study of Chang 7 Tight Sandstone in the Ordos Basin. Processes 2022, 10(10), 1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, M.F.; Bian, J.; Wang, B.; Xu, J.K.; Sun, R.C. Hydrothermal carbonisation of bamboo in an oxalic acid solution: effects of acid concentration and retention time on the characteristics of products. RSC advances 2015, 5(94), 77147–77153. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Xing, B.; Ding, Y.; Han, X.; Wang, S. A critical review of the production and advanced utilisation of biochar via selective pyrolysis of lignocellulosic biomass. Bioresource Technology 2020, 312, 123614. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, J.; Cheng, Z.; Zhou, L. Nitrogen-doping enhanced fluorescent carbon dots: green synthesis and their applications for bioimaging and label-free detection of Au3+ ions. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2016, 4(6), 3053–3061. [Google Scholar]

- Libra, J.A.; Ro, K.S.; Kammann, C.; Funke, A.; Berge, N.D.; Neubauer, Y.; Titirici, M.M.; Fühner, C.; Bens, O.; Kern, J.; Emmerich, K.H. Hydrothermal carbonisation of biomass residuals: a comparative review of the chemistry, processes, and applications of wet and dry pyrolysis. Biofuels 2011, 2(1), 71–106. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, X.; Jordan, B.; Berge, N.D. Thermal conversion of municipal solid waste via hydrothermal carbonisation: Comparison of carbonisation products to products from current waste management techniques. Waste management 2012, 32(7), 1353–1365. [Google Scholar]

- Lucian, M.; Volpe, M.; Gao, L.; Piro, G.; Goldfarb, J.L.; Fiori, L. Impact of hydrothermal carbonisation conditions on the formation of hydrochar and secondary chars from the organic fraction of municipal solid waste. Fuel 2018, 233, 257–268. [Google Scholar]

- Madikizela, L.M.; Ncube, S.; Chimuka, L. Analysis, occurrence, and removal of pharmaceuticals in African water resources: A current status. Journal of Environmental Management 2020, 253, 109741. [Google Scholar]

- Madikizela, L.M.; Rimayi, C.; Khulu, S.; Ncube, S.; Chimuka, L. Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products, in Emerging Freshwater Pollutants. In Elsevier; Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 71–190. [Google Scholar]

- Madureira, T.V.; Rocha, M.J.; Cass, Q.B.; Tiritan, M.E. Development and Optimisation of an HPLC-DAD Method for the Determination of Diverse Pharmaceuticals in Estuarine Surface Waters. Journal of Chromatographic Science 2010, 48, 176–182. [Google Scholar]

- Maqhuzu, A.B.; Yoshikawa, K.; Takahashi, F. Stochastic economic analysis of coal alternative fuel production from municipal solid wastes employing hydrothermal carbonisation in Zimbabwe. Science of The Total Environment 2020, 716, 135337. [Google Scholar]

- Meisel, K.; Clemens, A.; Fühner, C.; Breulmann, M.; Majer, S.; Thrän, D. Comparative life cycle assessment of HTC concepts valorising sewage sludge for energetic and agricultural use. Energies 2019, 12(5), 786. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, S. Combining solar power with coal-fired power plants or cofiring natural gas. Clean Energy 2018, 2(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Mumme, J.; Eckervogt, L.; Pielert, J.; et al. Hydrothermal Carbonization of Anaerobically Digested Maize Silage. Bioresource Technology 2011, 102, 9255–9260. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mumme, J.; Titirici, M.M.; Pfeiffer, A.; Luder, U.; Reza, M.T.; Mä sek, O. Hydrothermal ̌ carbonisation of digestate in the presence of zeolite: process efficiency and composite properties. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2015, 3(11), 2967–2974. [Google Scholar]

- Munir, M.T.; Mansouri, S.S.; Udugama, I.A.; Baroutian, S.; Gernaey, K.V.; Young, B.R. Resource recovery from organic solid waste using hydrothermal processing: Opportunities and challenges. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2018, 96, 64–75. [Google Scholar]

- Ngqwala, N.P.; Muchesa, P. Occurrence of pharmaceuticals in aquatic environments: A review and potential impacts in South Africa. South African Journal of Science 116 2020, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Nordea. Impacts of Pharmaceutical Pollution on Communities and Environment in India Impacts of Pharmaceutical Pollution on Communities and Environment in India. Nord. Asset Management 2016, Vol 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Panel, C.H.; Rao, Y.; Cao, L.; Shi, Y.; Hao, S.; Luo, G.; Zhang, S. Hydrothermal conversion of sewage sludge: Focusing on the characterisation of liquid products and their methane yields. Chemical Engineering Journal 2019, 367–375. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, S.; Mondal, S.; Majumder, S.K.; Das, P.; Ghosh, P. Treatment of a Pharmaceutical Industrial Effluent by a Hybrid Process of Advanced Oxidation and Adsorption. ACS Omega 2020, 50(5), 32305–32317. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlovic, I.; Barriga, C.; Hermosín, M. C.; Cornejo, J.; Ulibarri, M. A. Adsorption of acidic pesticides 2, 4-D, Clopyralid, and Picloram on calcined hydrotalcite. Applied Clay Science 2005, 30(2), 125–133. [Google Scholar]

- Petlovanyi, M.V.; Medianyk, V.Y. Assessment of coal mine waste dumps development priority. Scientific Bulletin of the National Mining University 2018, (4), 28–35. [Google Scholar]

- Picone, A.; Volpe, M.; Messineo, A. Process water recirculation during hydrothermal carbonisation of waste biomass: Current knowledge and challenges. Energies 2021, 14(10), 2962. [Google Scholar]

- Picone, A.; Volpe, M.; Messineo, A. Process water recirculation during hydrothermal carbonisation of waste biomass: Current knowledge and challenges. Energies 2021, 14(10), 2962. [Google Scholar]

- Racek, J.; Sevcik, J.; Chorazy, T.; Kucerik, J.; Hlavinek, P. Biochar–recovery material from pyrolysis of sewage sludge: a review. Waste and biomass valorisation 2020, 11(7), 36773709. [Google Scholar]

- Raheem, P.A.; Sikarwar, V.S.; He, J.; Dastyar, W.; Dionysiou, D.D.; Wang, W.; Zhao, M. Opportunities and challenges in sustainable treatment and resource reuse of sewage sludge: A review. Chemical Engineering Journal 2018, 616–641. [Google Scholar]

- Reza, M.T.; Yan, W.; Uddin, M.H.; Lynam, J.G.; Hoekman, S.K.; Coronella, C.J.; Vásquez, V.R. Reaction kinetics of hydrothermal carbonisation of loblolly pine. Bioresource Technology 2013, 139, 161–169. [Google Scholar]

- Reza, M.T.; Yang, X.; Coronella, C.J.; Lin, H.; Hathwaik, U.; Shintani, D.; Neupane, B.P.; Miller, G.C. Hydrothermal carbonisation (HTC) and pelletisation of two arid land plants bagasse for energy densification. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2016, 4(3), 11061114. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, D.L. Practical wastewater treatment; John Wiley & Sons, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Saba, A.; Saha, P.; Reza, M.T. Co-Hydrothermal Carbonization of coal-biomass blend: Influence of temperature on solid fuel properties. Fuel processing technology 2017, 167, 711–720. [Google Scholar]

- Saha, N.; Saba, A.; Reza, M.T. Effect of hydrothermal carbonisation temperature on pH, dissociation constants, and acidic functional groups on hydrochar from cellulose and wood. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis 2019, 137, 138–145. [Google Scholar]

- Sekulic, M.T.; Boskovic, N.; Slavkovic, A.; Garunovic, J.; Kolakovic, S.; Pap, S. Surface functionalised adsorbent for emerging pharmaceutical removal: adsorption performance and mechanisms. Process Safety and Environmental Protection 2019, 125, 50–63. [Google Scholar]

- Shaddel, S.; Bakhtiary-Davijany, H.; Kabbe, C.; Dadgar, F.; Østerhus, S.W. Sustainable sewage sludge management: From current practices to emerging nutrient recovery technologies. Sustainability 2019, 11(12), 3435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.; Delerue-Matos, C.; Figueiredo, S.A.; Freitas, O.M. The use of algae and fungi for removal of pharmaceuticals by bioremediation and biosorption processes: a review. Water 2019, 11(8), 1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, É.M.L.; Otero, M.; Rocha, L.S.; Gil, M.V.; Ferreira, P.; Esteves, V.I.; Calisto, V. Multivariable Optimisation of activated carbon production from microwave pyrolysis of brewery wastes-Application in the removal of antibiotics from water. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2022, 431, 128556. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stemann, J., & Ziegler, F. (2011). Assessment of the energetic efficiency of a continuously operating plant for hydrothermal carbonisation of biomass. World Renewable Energy Congress, Sweden, 125-132.

- Stemann, J.; Putschew, A.; Ziegler, F. Hydrothermal carbonisation: Process water characterisation and effects of water recirculation. Bioresource Technology 2013, 143, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stolboushkin, E., Gilliat, J., Hillis, P. & Zuklic, S. (2016). Successful Deployment of Electro-Hydraulic TCP Firing Head Improves Safety and Reduces Rig-Time. In SPE Deepwater Drilling and Completions Conference. OnePetro.

- Subramanian, N.; Mahendran, R.; Ahmad, M.; Ahmad, M.; Shafiq, M.; Shafiq, M.; Choi, J. G.; Choi, J. G. Optimization-Driven Machine Learning Approach for the Prediction of Hydrochar Properties from Municipal Solid Waste. Sustainability 2023, 15(7), 6088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, Y.; Benzaazoua, M.; Edahbi, M.; Mansori, M.; Hakkou, R. Leaching and geochemical behaviour of fired bricks containing coal wastes. Journal of environmental management 2018, 209, 227235. [Google Scholar]

- Tasca, A. L., Puccini, M., Gori, R., Corsi, I., Galletti, A. M. R., & Vitolo, S. (2019). Hydrothermal carbonisation of sewage sludge: a critical analysis of process severity, hydrochar properties, and environmental implications. Waste Management, 93, 1-13. Tasca et al., 2011.

- Van de Venter, F.F. (2021). Producing briquettes for domestic household fuel applications from coal tailings (Doctoral dissertation).

- Wang, D.; Fang, G.; Xue, T.; et al. A melt route for synthesising activated carbon derived from a carton box for high-performance symmetric supercapacitor applications. Journal of Power Sources 2016, 307, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chang, Y.; Li, A. Hydrothermal carbonisation for energy-efficient processing of sewage sludge: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2019, 108, 423–440. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Sun, F.; Hao, F. A green trace K2CO3-induced catalytic activation strategy for developing coal-converted activated carbon as an advanced candidate for CO2 adsorption and supercapacitors. Chemical Engineering Journal 2020, 383, 123205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhai, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Li, C.; Zeng, G. A review of the hydrothermal carbonisation of biomass waste for hydrochar formation: Process conditions, fundamentals, and physicochemical properties. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2018, 90, 223–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, B.; Poerschmann, J.; Wedwitschka, H.; Koehler, R.; Kopinke, F.D. Influence of process water reuse on the hydrothermal carbonisation of paper. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2014, 2(9), 2165–2171. [Google Scholar]

- Wilk, M.; Magdziarz, A.; Jayaraman, K.; Szymańska-Chargot, M.; Gökalp, I. Hydrothermal carbonisation characteristics of sewage sludge and lignocellulosic biomass. A comparative study. Biomass and Bioenergy 2019, 120, 166–175. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, Y.; Xu, Z.; Wei, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, X.; Yang, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhang, J.; Luo, L.; Zhou, Z. Carbon-based materials as adsorbent for antibiotics removal: mechanisms and influencing factors. Journal of Environmental Management 2019, 237, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yin, L.; Farimani, A.B.; Min, K.; Vishal, N.; Lam, J.; Lee, Y.K.; Aluru, N.R.; Rogers, J.A. Mechanisms for hydrolysis of silicon nanomembranes as used in bioresorbable electronics. Advanced Materials 2015, 27(11), 1857–1864. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Chesnutt, B.M.; Haggard, W.O.; Bumgardner, J.D. Deacetylation of chitosan: Material characterisation and in vitro evaluation via albumin adsorption and pre-osteoblastic cell cultures. Materials 2011, 4, 1399–1416. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Li, Z.; Wu, Y.; Guo, X.; Ye, J.; Yuan, B.; Wang, S.; Jiang, L. Recent advances in the thermal destabilisation of Mg-based hydrogen storage materials. RSC advances 2019, 9(1), 408–428. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Lv, H.; Kang, H.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, C. A literature review of failure prediction and analysis methods for composite high-pressure hydrogen storage tanks. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44(47), 25777–25799. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, N.; Wang, G.; Yu, C.; Zhang, J.; Dang, H.; Zhang, C.; Ning, X.; Wang, C. Physicochemical structure characteristics and combustion kinetics of low-rank coal by hydrothermal carbonisation. Energy 2022, 238, 121682. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).