1. Introduction

Aging is a highly complex and multifactorial process influenced by genetic, environmental, and cellular pathways, involving intricate molecular mechanisms that regulate cellular homeostasis, metabolic balance, and stress responses [

1]. In recent decades literature has highlighted the critical role of epigenetic modifications, mitochondrial dysfunction, telomere attrition, and chronic inflammation—often referred to as "inflammaging"—in driving the aging process [

2]. Additionally, sirtuins (SIRTs), a conserved family of proteins involved in cellular stress resistance and metabolic regulation, have emerged as key regulators of longevity, modulating gene expression, DNA repair and cellular metabolism. Their involvement in pathways such as mitochondrial biogenesis, oxidative stress resistance, and autophagy underscores their potential as therapeutic targets for age-related diseases [

3]. Understanding these interconnected mechanisms provides valuable insights into strategies promoting healthy aging and extending lifespan.

Seven sirtuins, listed from 1 to 7, have been recognized so far. Each shows a catalytic domain (present in all sirtuins), and different N- and C-ends give each sirtuin specific biological features [

4].

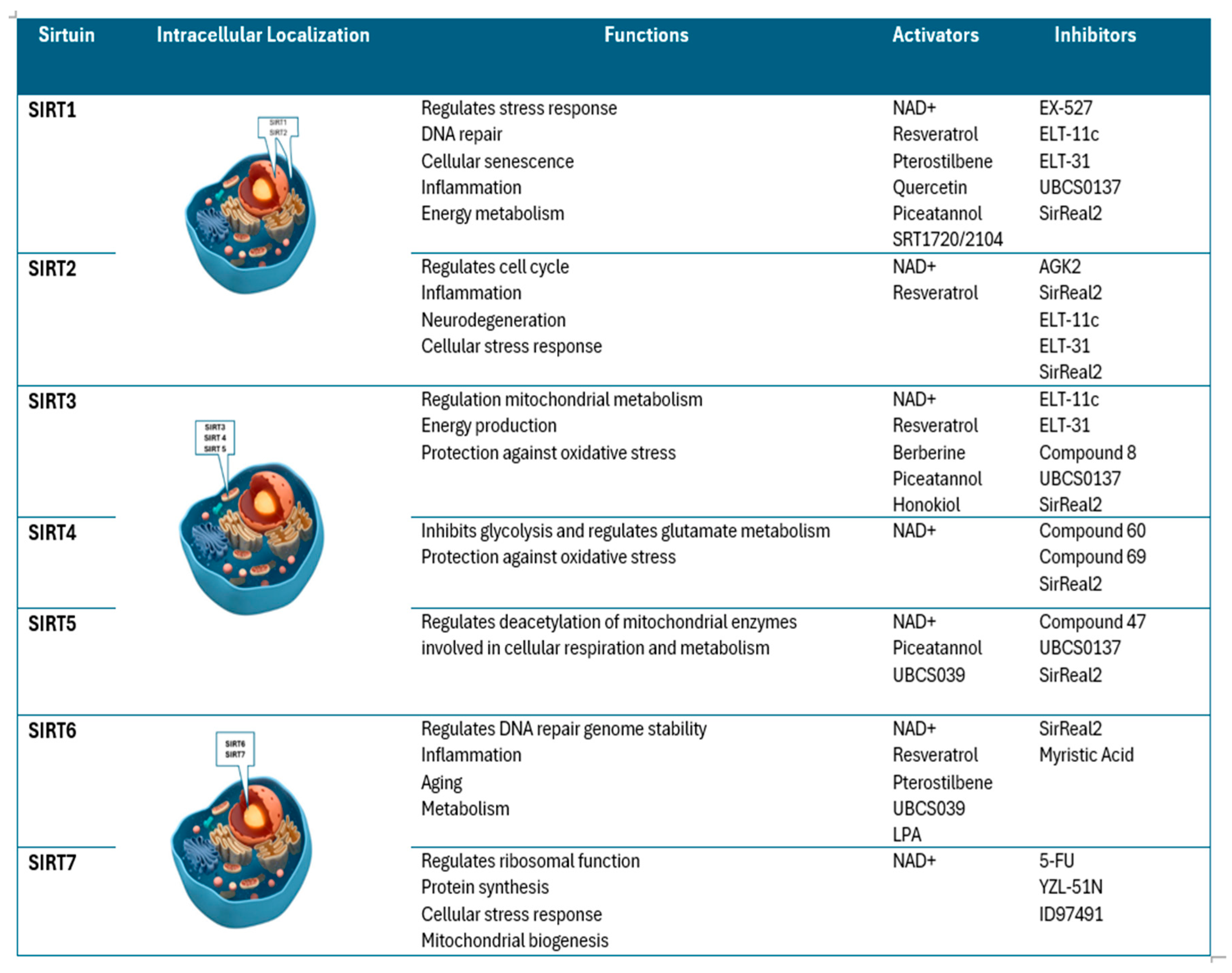

Sirtuins (SIRT1–SIRT7) exhibit distinct intracellular localization, with SIRT1, SIRT6, and SIRT7 primarily nuclear, SIRT2 cytoplasmic, and SIRT3–SIRT5 mitochondrial, influencing diverse cellular functions. Their activity is modulated by various activators such as NAD

+, resveratrol and Piceatannol, and inhibitors like nicotinamide, EX-527 and SirReal2 (

Figure 1) [

5].

Sirtuins may promote different post-translational modifications in many different proteins so they are actually known as deacetylases [

6]. Sirtuins’ activity depends on nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD

+). This is very important if we consider that NAD

+ is a crucial cofactor for many mitochondrial metabolic processes that lead to energy production. Mitochondria are largely expressed in heart and kidneys. Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) production leads to altered DNA and electron chain transport, thus impairing mitochondrial function. This dangerous chain could be counteracted by healthy mitochondria and selective autophagy of damaged ones thus explaining the beneficial effects of caloric restriction [

7].

The classification of sirtuins as merely NAD

+-dependent deacetylase is an oversimplification that does not fully capture the complexity of their biological roles. Although NAD

+ is an essential cofactor for the majority of sirtuins, it is not the sole determinant of their enzymatic activity. Sirtuins are involved in a broader range of cellular processes and enzymatic modifications, extending well beyond deacetylation. This functional diversity underscores the need to recognize the multifaceted nature of sirtuin biology. While deacetylation is the most widely studied activity of sirtuins, some members of the sirtuin family catalyze additional post-translational modifications, including ADP-ribosylation [

8] and deacetylation of non-acetyl groups [

9]. Notably, SIRT5 is involved in the deacetylation of succinyl groups [

10], highlighting the ability of sirtuins to modulate a diverse array of acyl groups beyond acetylation. Moreover, SIRT1 and SIRT6 have been shown to catalyze mono-ADP-ribosylation, a modification that plays a crucial role in DNA repair and various regulatory pathways, further broadening the scope of sirtuin function [

11].

In our previous studies we investigated the role of sirtuins modulating factors that accelerate physiological aging, including glucose metabolism, DNA integrity, cancer development, neurodegenerative disorders, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [

12,

13].

Building on our previous work and recent findings the current objective is to elucidate the role of sirtuins as key pathophysiological mediators and potential therapeutic targets in the progression of Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD). Additionally, recognizing the intricate interrelationship between cardiovascular and renal dysfunction, we aim to investigate the involvement of sirtuins in heart diseases, with a particular focus on the cardio-renal axis and the molecular mechanisms underlying cardio-renal cross-talk.

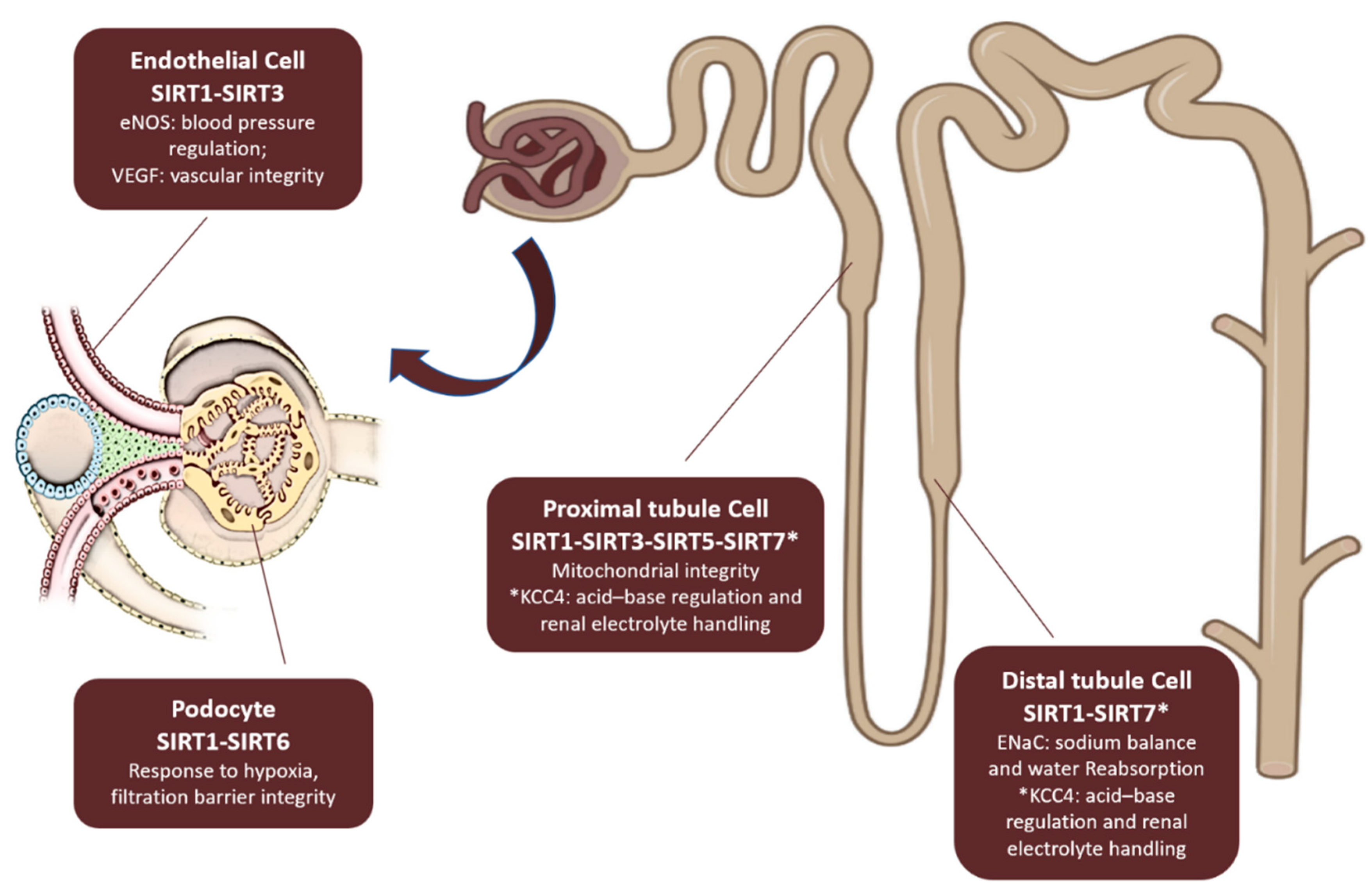

Sirtuins in Kidney Diseases

In kidney disease, sirtuins influence key pathological mechanisms such as fibrosis, apoptosis, mitochondrial dysfunction, and inflammation, which contribute to disease progression [

14,

15]. Dysregulation of sirtuin activity has been implicated in acute kidney injury [

16], diabetic nephropathy [

17], and chronic kidney disease [

18,

19]. Understanding the precise roles of sirtuins in renal physiology and pathology may provide new therapeutic targets for mitigating kidney disease and improving renal function. Regarding physiology, sirtuins’expression in kidney and their functions are illustrated in

Figure 2.

Sirtuins and Acute Kidney Injury

Aging kidneys show an increased vulnerability to ischemia/reperfusion (I/R)-induced injury, suggesting that sirtuins might play a significant role in the response to I/R. SIRT1 has been shown to confer resistance to kidney injury after I/R [

20]. Overexpression of SIRT1 reduces kidney injury by activating anti-oxidant pathways such as the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway and reducing p53 expression, which subsequently attenuates apoptosis [

20,

21]. Additionally, SIRT1 promotes mitochondrial biogenesis, restoring ATP levels and reducing mitochondrial mass, nitrosative stress, and inflammation, which help protect against I/R injury. Activators like SRT1720, which stimulate SIRT1, have been shown to improve renal function following I/R injury by enhancing mitochondrial function and reducing inflammation [

22]. The activation of mitochondrial biogenesis through PGC-1α is proposed as a key mechanism for repair after I/R injury [

23].

SIRT3, predominantly localized in the mitochondrial matrix, is another key sirtuin involved in I/R injury. Following I/R, SIRT3 expression increases, and its overexpression helps protect the kidneys by suppressing superoxide generation [

24]. Loss of SIRT3, however, exacerbates kidney injury by impairing mitochondrial homeostasis, a process that can be rescued through restoration of SIRT3 via the AMPK/PGC-1α pathway [

25].

Interestingly, SIRT5 has a distinct role in I/R injury, with loss of SIRT5 function conferring renoprotective effects. SIRT5 regulates fatty acid oxidation by shifting it from the mitochondria to peroxisomes, which appears to improve kidney function after I/R [

26]. Conversely, SIRT6 has been linked to the negative regulation of tubular cell injury and inflammation during I/R injury, suggesting a protective role [

27].

Sirtuins, particularly SIRT1 and SIRT6, have been found to alleviate kidney injury in sepsis-induced AKI by modulating inflammatory responses and promoting autophagy. In contrast, the role of SIRT2 in sepsis-induced AKI appears to be detrimental, as the absence of SIRT2 improves renal function and reduces tubular injury [

28]. SIRT1 has also been shown to attenuate contrast-induced nephropathy (CIN), a common cause of AKI, through its modulation of oxidative stress and apoptosis via the PGC-1α/FoxO1 signaling pathway [

29]. SIRT3 deficiency exacerbates CIN, while activation of the SIRT3-Nrf2 pathway provides protection [

30].

Sirtuins in Chronic Kidney Disease and Fibrosis

By 2021, a joint statement from the American Society of Nephrology, European Renal Association, and International Society of Nephrology indicated that more than 850 million people suffer from some form of kidney disease. CKD affects between 8% and 16% of the population worldwide. It is defined by a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, albuminuria of at least 30 mg per 24 hours, or markers of kidney damage (eg, hematuria or structural abnormalities such as polycystic or dysplastic kidneys) persisting for more than 3 months [

31].

CKD is associated with a great increase in morbidity and mortality and a decrease in health related quality of life. The severity of these complications is generally proportional to the decline in renal function and it is most evident in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) [

32]. Moreover, CKD causes very important economic consequences. In 2023, in USA there was a 40% increase, from

$54.9B to

$76.8B in expenditures for individuals with CKD [

33].

The risk of CKD increases with age and elderly patients are overrepresented in dialysis population [

34]. Moreover, a reciprocal relationship between CKD and aging seems to exist, since CKD may contribute to premature biological aging of different organ systems [

35]. This may result in the occurrence of usually geriatric complications in relatively young patients with ESRD [

10].

Each of the seven sirtuins plays a role in this complex relationship.

Fibrosis is a hallmark of nearly all progressive forms of Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD), regardless of the initial cause [

36]. This fibrotic progression is closely linked to impaired NAD+ biosynthesis, which downregulates the activity of sirtuins, including those with anti-fibrotic roles. In rat models of CKD, it has been shown that NAD+ biosynthesis is significantly reduced, impairing the functions of SIRTs, which are crucial for combating fibrosis [

37].

SIRT1 expression is notably decreased in kidney biopsies from patients with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) [

38]. Experimental studies have shown that silencing SIRT1 exacerbates fibrosis in mice with unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO), a model of progressive kidney injury [

39]. In contrast, stimulating SIRT1 through pharmacological interventions or genetic manipulation has been found to reduce inflammation and matrix protein accumulation, thus mitigating fibrosis in experimental models of CKD [

40].

The anti-fibrotic activity of SIRT1 is primarily attributed to its ability to inhibit the TGFβ signaling pathway by deacetylating Smad3 and Smad4. This action reduces the transcription of pro-fibrotic genes such as collagen IV, fibronectin, and matrix metalloproteinase 7 (MMP7)[

41]. Additionally, SIRT1 influences endothelial cell function, as demonstrated by targeted deletion of SIRT1 in the endothelium, which impaired vasorelaxation and promoted fibrosis by downregulating MMP14, stimulating the HIF2α–Notch1 axis, and releasing proteolytic fragments of the endothelial glycocalyx [

42].

SIRT6 also plays a protective role against kidney fibrosis. After fibrotic insults, SIRT6 is upregulated in the kidneys and interacts with β-catenin. This complex binds to the promoters of fibrogenic genes and prevents their transcription through SIRT6-dependent deacetylation of histone proteins [

43]. SIRT6 overexpression in mice prevented renal interstitial fibrosis induced by a high-adenine diet by downregulating HIPK2, which regulates several pro-fibrotic pathways [

44]. In renal tubular cells, the phosphorylation of SIRT6 by GSK3β prevented its degradation, thus supporting its anti-fibrotic actions. SIRT3, a mitochondrial sirtuin, has been shown to play a role in mitigating fibrosis in multiple organs, including the kidney. In SIRT3-deficient mice, age-dependent fibrosis in the kidney is exacerbated due to increased TGFβ signaling and hyperacetylation of GSK3β, which leads to the activation of Smad3 [

45]. Additionally, SIRT3-deficient mice exhibited reduced levels of mitochondrial fusion proteins (Opa1 and Mfn1) and increased levels of Drp1, leading to mitochondrial fission, a process associated with renal dysfunction and fibrosis since its early stage [

46].

In podocytes, SIRT3 has been shown to deacetylate KLF15, a negative regulator of extracellular matrix protein synthesis, helping to reduce fibrosis [

47]. Moreover, SIRT3 inhibits renal calcium oxalate crystal formation by promoting macrophage M2 polarisation via the deacetylation of FOXO1 [

48] and protects from hyperlipidemia-related renal injury [

49].

Sirtuins in Hypertensive Nephropathy

Sirtuins, particularly SIRT3 and SIRT6, have been shown to exert protective effects in the pathogenesis of hypertensive nephropathy through various biological functions such as anti-oxidative stress, anti-apoptosis, anti-fibrosis, anti-inflammation, and anti-mitochondrial injury. The protective mechanisms of these sirtuins are primarily achieved by regulating protein post-translational modifications (PTM), signaling pathways, and transcription factors. Studies using SIRT3 knockout or overexpression mouse models have demonstrated that SIRT3 plays a critical role in alleviating renal fibrosis and oxidative stress in hypertensive nephropathy. In SIRT3-deficient mice receiving Angiotensin II (Ang II) infusion, there was an increase in endothelial mesenchymal transformation (EndoMT) and reactive oxygen species (ROS), which aggravated renal dysfunction [

50]. On the other hand, SIRT3 transgenic endothelial-specific mice (TgEC) exhibited alleviation of Ang II-induced renal fibrosis, EndoMT, and oxidative stress, indicating that SIRT3 plays a protective role in mitigating hypertension-induced kidney damage [

51]. SIRT3 knockout also led to iron overloading and enhanced ROS formation in renal cells via NADPH oxidase, further worsening renal fibrosis,in contrast, SIRT3 overexpression protected against kidney injury induced by Ang II [

47,

52]

SIRT6 also plays a key protective role in hypertensive nephropathy by regulating protein PTM, DNA damage, cellular metabolism, and mitochondrial function. In endothelial cells, SIRT6 prevents injury by inhibiting the NK3 homeobox 2-GATA binding protein 5 signaling pathway through deacetylation of histone H3 lysine 9 (H3K9) [

53].Furthermore, SIRT6 has been shown to alleviate Ang II-mediated inflammation and oxidative damage induced by Ang II suppressing ROS and enhancing gene expression of Nrf2 and HO-1 [

54].

Sirtuins in Diabetic Kidney Disease

One of the most common causes of CKD is diabetes. Diabetic kidney disease (DKD) is defined by the presence of CKD in a person with diabetes [

31] and it is considered as the leading cause of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) in developed and developing countries [

55]. Sirtuins play a critical role in the pathogenesis of DKD through their regulatory effects on various cellular pathways [

56]. Among them, SIRT1, SIRT3, SIRT4, SIRT6 and SIRT7 have been demonstrated to exert renoprotective effects during both the initiation and progression of DKD [

57,

58,

59]. These protective actions are mediated through their ability to deacetylate key target proteins and directly modulate the expression of genes and signaling pathways. In patients with DKD, SIRT1 expression is significantly downregulated in both serum and renal tissues, suggesting a strong correlation between its expression levels and kidney function [

60]. SIRT1 exerts its protective effects by regulating transcription factors such as NF-κB and FoxO, thereby reducing inflammation, oxidative stress, and apoptosis; it also influences key signaling pathways, including AMPK/SIRT1, which promotes autophagy and mitochondrial function, and TGF-β1/Smad3, which mitigates fibrosis [

61]. Furthermore, SIRT1 interacts with molecules like NQO1 and glucagon-like peptide-1 to prevent apoptosis and oxidative stress, ultimately alleviating DKD progression [

62]. SIRT3 alleviates DKD by preventing HG-induced apoptosis, reducing ROS production, and activating autophagy through AMPK/PGC-1α signaling [

63]. SIRT4 protects podocytes by reducing mitochondrial ROS and inhibiting NF-κB-mediated inflammation and apoptosis [

64]. SIRT7, mitigates podocyte apoptosis and inflammation under diabetic conditions [

65]. Collectively, these sirtuins contribute to mitochondrial homeostasis and anti-inflammatory mechanisms, highlighting their therapeutic potential in DKD. The roles of SIRT2 and SIRT6 in DKD remain unclear due to conflicting findings. SIRT2 expression is reported to be both upregulated and downregulated under hyperglycemia, with its knockdown enhancing cell proliferation and reducing apoptosis, suggesting a potential role in DKD pathology meanwhile SIRT6 is linked to increased TNF-α expression, suggesting a role in inflammation [

17,

66,

67].

Polycystic Kidney Disease

The role of SIRTs in autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD)is still emerging. Studies show that SIRT1 inhibition—either through silencing or pharmacological means—reduces cyst formation in mice. This negative effect of SIRT1 in ADPKD is linked to its suppression of Rb and p53, which promotes epithelial cell proliferation and cyst growth [

68]. However, a clinical trial testing oral niacinamide, a SIRT inhibitor, in ADPKD patients showed good safety and tolerability but failed to slow kidney enlargement over 12 months [

69].In ADPKD patients compared to healthy subjects Kurtgoz and coworkers found that urine SIRT1 levels were significantly lower. Also serum SIRT1 levels of ADPKD patients were higher than control cases, but the difference wasn’t statistically significant. These findings suggest an impaired SIRT1 metabolism in ADPKD patients which might play a role in cysts development [

70]. SIRT2 is involved in cilia pathophysiology and centrosome function that on their turns are involved in polycystic kidney disease and in ciliopathy-associated disease progression [

68]. Moreover, by inhibiting caspase-3 and ROS generation, it affects apoptosis and oxidative stress [

71].

Sirtuins and Cardiovascular Diseases

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), principally ischemic heart disease (IHD) and stroke, are the leading cause of global mortality and a major contributor to disability. The total number of cardiovascular events almost doubled from 1990 to 2019 [

72]. Notably, an increasing number of studies linked SIRTs with different CVDs. SIRTs affect the production of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) by modulating mitochondrial function and increasing endothelial dysfunction, leading to an increased progression of atherosclerotic lesions [

73]. The imbalance of SIRTs levels may increase the vulnerability to CVDs, including heart failure (HF), atherosclerosis, ischaemic heart disease, hypertrophic heart disease and metabolic disease.

It seems that SIRT1 protects the heart from hypertrophic stimulation, oxidative stress damage, ROS accumulation and apoptotic damage. It also could avoid ischemic/reperfusion injury, as well as SIRT3 and SIRT6 [

74,

75,

76]; SIRT3 exerts a cardioprotective role by protecting mitochondrial function; evidences suggest that activation of SIRT6 may be a therapeutic tool to treat atherosclerosis.

The role of SIRTs in atherosclerosis is relatively clear, with main effects in regulating LDL cholesterol levels, macrophages, foam cells, and endothelial function through various factors and signaling pathways; SIRT1, SIRT3 and SIRT6 are the sirtuins involved in protecting against atherosclerosis and cardiac hypertrophy [

77,

78,

79]. They also exhibit a protecting role towards diabetic cardiomyopathy. Unfortunately, not all SIRTs activities are beneficial. For example, SIRT2 is destructive in I/R injury (its downregulation is protective against I/R injury [

80]) and SIRT4 is detrimental towards heart hypertrophy and fibrosis [

81].

SIRTs are involved in pathophysiological mechanisms of HFpEF (heart failure with preserved ejection fraction) [

82]. As summarized by European Society of Cardiology [

83], it is the most significant subtype of HF, and it is primarily characterized by left ventricular diastolic dysfunction (LVDD).

SIRT family has recently been found to be associated with HFpEF development through different signaling pathways such as the eEF2K/eEF2 pathway, the SIRT1/transmembrane BAX inhibitor motif, the Sirt3/MnSOD pathway, and the AMPK/PGC-1α pathway, causing endoplasmic reticulum stress, apoptosis, mitophagy, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction [

84]. SIRT4, SIRT5, and SIRT7, instead, are downregulated in HF.

Sirtuins and Cardio-Renal Diseases

It is well known that fibrosis is also involved in the onset of HF and it is also recognized as the linkage mechanism between heart and kidney in the development of cardio-renal diseases. Fibrosis arises from the proliferation of fibroblasts and their differentiation to myofibroblasts and subsequent deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM). Another important factor involved in heart and kidney fibrosis is endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EndMT) [

85,

86] that seems to be an important mechanism leading to glomerular sclerosis in DKD [

87]. Several studies shown that TGF-β, through activation of several signaling pathways (TGF/Smad, Erk, Akt), is the main stimulator and modulator of EndMT [

88]. According to previous studies, SIRT1 and SIRT3 (both decreased in TGF-β - induced EndMT) seem to be TGF-β inhibiting factors [

89,

90] so their upregulation could be a chance to attenuate both cardiac and renal fibrosis thus mitigating cardio-renal syndromes, in which fibrosis plays an important role [

91].

One of the most important recognized mechanisms leading to cardiorenal syndromes (CRS) is endothelial dysfunction [

92,

93,

94], indeed it plays an important role in the pathophysiology of hypertension, which is considered as one of the most common risk factor in the development of both renal and cardiac damage. Guo J et al., in a murine model, demonstrated that the downregulation of SIRT6 contributes to endothelial dysfunction and is involved in the pathogenesis of hypertension. The aim of the study was to explore the role of SIRT6 in the development of hypertension and the molecular mechanisms involved. It was found that SIRT6 indirectly regulates the expression of GATA5, a transcription factor that regulates blood pressure, through inhibiting Nkx3.2 expression. It is clear that the downregulation of SIRT6 reduces GATA5 expression and this leads to endothelial dysfunction through reduced nitric oxide bioavailability and increased permeability, and subsequent hypertension and cardiorenal injury [

95]. These findings suggest that SIRT6 upregulation may be useful to counteract both hypertension and cardiorenal damage by improving the endothelial function.

Mitochondrial dysfunction is another important factor involved in the pathophysiology of cardiorenal syndromes; it entails the reduction of glutathione (GSH) levels, increased inflammation and altered redox signaling, all of these factors are involved in the genesis of oxidative stress and subsequential cardiorenal damage. The SIRTs’ role in mitochondrial impairment emerges from involvement of SIRT1 and SIRT3 in the AMPK-SIRT1/3-PGC-1α axis in CRS 3 and 4, in which a primary acute or chronic kidney damage leads to cardiac dysfunction. This axis regulates several mitochondrial pathways such as fatty acid oxidation, oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), inflammation and mitochondrial ROS production. It was found that the AMPK-SIRT1/3-PGC-1α axis is downregulated in CRS 3 and 4 and it is closely related to mitochondrial impairment, moreover it seems that N-acetylcysteine (NAC) has protective effects against oxidative stress and inflammation thanks to its ability to increase AMPK, SIRT1 and SIRT3 expression. In conclusion, the use of antioxidants (such as NAC) should be considered as a strategy to reduce cardiorenal damage through the restoration of the AMPK-SIRT1/3-PGC-1α axis activity, exploiting its ability of mitigating both inflammation and oxidative stress by increasing the expression of SOD2 (superoxide dismutase) and GPx (glutathione peroxidase) and decreasing NLRP3 inflammasome/IL-1β/IL-18 activation [

96].

Resveratrol and Sirtuins Agonists in Cardio-Renal Diseases

After brief dissertation, it is clear how sirtuins deserve our attention for their deep involvement in metabolic and pathophysiological ways of kidney and heart disease so these enzymes could be hypothesized as therapeutical targets. Different natural SIRT1 agonists showed renoprotective effects in animal models [

97] and among these Resveratrol (RSV) and other phenolic compounds have been widely investigated with interesting and positive results.

Polyphenols, a diverse group of phytochemicals found in various fruits, vegetables, teas, and wines, have garnered significant attention in recent years for their potential health benefits, particularly in the context of cardiorenal diseases. These compounds have been shown to exhibit antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and vasodilatory effects, which may be beneficial for cardiovascular and renal health.

RSV has been proven to be useful in treating different chronic diseases through enhancing mitochondrial quality [

98] which is altered in several chronic diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), cardiovascular disease, obesity, cancer and various forms of CKD (including DKD, IgA kidney disease, membranous nephropathy and polycystic kidney disease) [

99]. RSV seems to be able to regulate mitochondrial dynamics, mitophagy, endogenous mitochondrial apoptosis, oxidative stress, mitochondrial membrane homeostasis, and respiratory chain function and mitochondrial quality control thus contributing to delay the onset of the above mentioned chronic diseases [

98]. SIRT1 activated by RSV attenuates ISO-induced cardiac dysfunction and fibrosis by regulating EndMT in vivo [

100]. SIRT1 overexpression suppressed the development of TGF-β1-induced EndMT in vitro. In this study it was also shown that P-Smad2/3 expression was increased in ISO-induced cardiac fibrosis, but was attenuated by RSV-activated SIRT1 (perhaps due to SIRT1’s ability to inhibit the nuclear translocation of Smad2/3).

Also in CKD patients, Resveratrol exerts beneficial, promising effects by modulating SIRT1 levels, oxidative stress and inflammation.

Pharmacologycal agents, such as SRT1720, a SIRT 1 activator, showed renal antifibrotic effects by reducing oxidative stress. [

101]

Physical exercise (both as single sessions and training) activates SIRT1 which, on its turn, activates mitochondrial oxidative function. [

102]

Sirtuins agonists (represented by NAD+), have gradually emerged as new treatments for heart failure. By modulating metabolism, maintaining redox homeostasis, and regulating immune responses, Sirtuins improve heart failure symptoms and prognosis.

More recently, Liraglutide, a novel antidiabetic agent, showed to influence SIRT1 expression in stroke patients and this finding confirms that sirtuins are worthy of investigation to ameliorate treatment and prognosis of CKD patients, independently of the cause of primary kidney disease. [

103]

SGLT2 inhibitors have been demonstrated to upregulate SIRT3 expression. SGLT2 inhibition suppressed epithelial to mesenchymal transition and fibrogenesis in kidney proximal tubules; this effect of SGLT2 inhibition was associated with its ability to restore SIRT3 expression and glycolysis [

104]. This interesting pharmacological activity could be a potential therapeutical target to prevent cardiac remodeling. Moreover, SGLT2 inhibitors activate SIRT1/PGC-1α/FGF21 pathway through their ability to induce a fasting-like metabolic and transcriptional paradigm [

105]. The cardioprotective effects of SGLT2 inhibitors may also be related to this particular signaling [

106].

Conclusions and Future Directions

Future research is obviously needed to clarify the role of these molecules and to enhance their potential therapeutical role in heart and kidney diseases. But, on our opinion, this topic is worthy of more attention because Resveratrol or other Sirtuins agonists’ administration could become an useful and safe tool in cardiorenal diseases.

In diabetic rats, the intergenerational treatment with oral resveratrol improved the functions of the heart, kidney, and brain. The more interesting finding is that resveratrol treatment increases the second and third generations' resistance to neurobehavioral changes, diabetes, and -associated cardio-renal dysfunction. [

107].

It is really interesting to hypothesize similar studies in humans to prove the efficacy and safety of this natural compound.

A systematic review and meta-analysis analyzed multiple studies on polyphenol intake and kidney health. The review concluded that higher dietary polyphenol intake was associated with a lower risk of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and improved renal function markers among the general population [

108] This aligns with findings from another study [

109] which demonstrated that higher consumption of flavonoid-rich foods was inversely related to the incidence of CKD in older adults.

In addition to their effects on blood pressure and kidney function, the anti-inflammatory properties of polyphenols have been shown to play a crucial role in protecting against the progression of cardiorenal diseases. A recent study [

110] explored the impact of berry polyphenols on inflammatory markers in patients with chronic heart failure. The findings suggested that berry supplementation led to a significant reduction in inflammatory cytokines and improved cardiac function, highlighting the protective role of polyphenols in cardiovascular health [

111].[1

In summary, emerging research underlines the potential of polyphenols as a promising dietary intervention for the prevention and management of cardiorenal diseases. Their beneficial effects on blood pressure, kidney function, lipid profiles, and inflammation make them a valuable area of study for improving cardiovascular and renal health outcomes. Continued exploration of polyphenol-rich diets in diverse populations will further elucidate their role in promoting cardiorenal health.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Maldonado, E.; Morales-Pison, S.; Urbina, F.; Solari, A. Aging Hallmarks and the Role of Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants (Basel). 2023, 12, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Baechle, J.J.; Chen, N.; Makhijani, P.; Winer, S.; Furman, D.; Winer, D.A. Chronic inflammation and the hallmarks of aging. Mol Metab. 2023, 74, 101755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Grabowska, W.; Sikora, E.; Bielak-Zmijewska, A. Sirtuins, a promising target in slowing down the ageing process. Biogerontology. 2017, 18, 447–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Michan, S.; Sinclair, D. Sirtuins in mammals: insights into their biological function. Biochem J. 2007, 404, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen, M.; Tan, J.; Jin, Z.; Jiang, T.; Wu, J.; Yu, X. Research progress on Sirtuins (SIRTs) family modulators. Biomed Pharmacother. 2024, 174, 116481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michishita, E.; Park, J.Y.; Burneskis, J.M.; Barrett, J.C.; Horikawa, I. Evolutionarily conserved and non conserved cellular localizations and functions of human SIRT proteins. Mol Biol Cell 2005, 16, 4623–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaban, R.S.; Nemoto, S.; Finkel, T. Mitochondria, oxidants, and aging. Cell 2005, 120, 483–495. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, W.; Jialong, Z.; Jiuzhi, Y.; Yang, Y.; Chongning, L.; Jincai, L. ADP-ribosylation, a multifaceted modification: Functions and mechanisms in aging and aging-related diseases. Ageing Res Rev. 2024, 98, 102347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konrad, T. Howitz, Screening and profiling assays for HDACs and sirtuins. Drug Discovery Today: Technologies, 2015, 18, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Lombard, D.B. Functions of the sirtuin deacylase SIRT5 in normal physiology and pathobiology. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2018, 53, 311–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Poltronieri, P.; Celetti, A.; Palazzo, L. Mono(ADP-ribosyl)ation Enzymes and NAD+ Metabolism: A Focus on Diseases and Therapeutic Perspectives. Cells. 2021, 10, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Carollo, C.; Urso, C.; Lo Presti, R.; Caimi, G. Sirtuins and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Food and Nutrition Sciences, 2018, 9, 1254–1260. [Google Scholar]

- Carollo, C.; Firenze, A.; Caimi, G. Sirtuins and Aging: is there a Role for Resveratrol? . International Journal of Advanced Nutritional and Health Science 2016, 4, 203–211. [Google Scholar]

- Haigis, M.C.; Sinclair, D.A. Mammalian sirtuins: biological insights and disease relevance. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2010, 5, 253–295. [Google Scholar]

- Kitada, M.; Ogura, Y.; Monno, I.; Koya, D. Sirtuins and Type 2 Diabetes: Role in Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Mitochondrial Function. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2019, 10, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Peasley, K.; Chiba, T.; Goetzman, E.; Sims-Lucas, S. Sirtuins play critical and diverse roles in acute kidney injury. Pediatr Nephrol. 2021, 36, 3539–3546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mortuza, R.; Chen, S.; Feng, B.; Sen, S.; Chakrabarti, S. High glucose induced alteration of SIRTs in endothelial cells causes rapid aging in a p300 and FOXO regulated pathway. PLoS One. 2013, 8, e54514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hao, Chuan-Ming, and Volker H. Haase. "Sirtuins and their relevance to the kidney.". Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2010, 21, 1620–1627.

- Ogura, Yoshio, Munehiro Kitada, and Daisuke Koya. "Sirtuins and renal oxidative stress.". Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1198.

- Fan, Hong, et al. "The histone deacetylase, SIRT1, contributes to the resistance of young mice to ischemia/reperfusion-induced acute kidney injury.". Kidney international 2013, 83, 404–413.

- Shi, Si, et al. "Melatonin attenuates acute kidney ischemia/reperfusion injury in diabetic rats by activation of the SIRT1/Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway.". Bioscience reports 2019, 39, BSR20181614.

- Hansen, L.W.; Khader, A.; Yang, W.L.; Prince, J.M.; Nicastro, J.M.; Coppa, G.F.; Wang, P. Sirtuin 1 activator SRT1720 protects against organ injury induced by intestinal ischemia-reperfusion. Shock. 2016, 45, 359–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fontecha-Barriuso, M.; Martin-Sanchez, D.; Martinez-Moreno, J.M.; Monsalve, M.; Ramos, A.M.; Sanchez-Niño, M.D.; Ruiz-Ortega, M.; Ortiz, A.; Sanz, A.B. The Role of PGC-1α and Mitochondrial Biogenesis in Kidney Diseases. Biomolecules. 2020, 10, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pan, Jenny Szu-Chin, et al. "Stanniocalcin-1 inhibits renal ischemia/reperfusion injury via an AMP-activated protein kinase-dependent pathway.". Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2015, 26, 364–378.

- Clark, A.J.; Parikh, S.M. Targeting energy pathways in kidney disease: the roles of sirtuins, AMPK, and PGC1α. Kidney Int. 2021, 99, 828–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chiba, T.; Peasley, K.D.; Cargill, K.R.; Maringer, K.V.; Bharathi, S.S.; Mukherjee, E.; Zhang, Y.; Holtz, A.; Basisty, N.; Yagobian, S.D.; Schilling, B.; Goetzman, E.S.; Sims-Lucas, S. Sirtuin 5 Regulates Proximal Tubule Fatty Acid Oxidation to Protect against AKI. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019, 30, 2384–2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gao, Z.; Chen, X.; Fan, Y.; Zhu, K.; Shi, M.; Ding, G. Sirt6 attenuates hypoxia-induced tubular epithelial cell injury via targeting G2/M phase arrest. J Cell Physiol. 2020, 235, 3463–73. [Google Scholar]

- You, J.; Li, Y.; Chong, W. The role and therapeutic potential of SIRTs in sepsis. Front Immunol. 2024, 15, 1394925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hong, Y.A.; Bae, S.Y.; Ahn, S.Y.; Kim, J.; Kwon, Y.J.; Jung, W.Y.; Ko, G.J. Resveratrol Ameliorates Contrast Induced Nephropathy Through the Activation of SIRT1-PGC-1α-Foxo1 Signaling in Mice. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2017, 42, 641–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, X.; Li, N.; Zhang, J.; Yang, J.; Bu, P. Sirtuin 3 deficiency aggravates contrast-induced acute kidney injury. J Transl Med. 2018, 16, 313, Erratum in: J Transl Med. 2022, 20, 46. 10.1186/s12967-021-03172-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group 2024. Kidney International 2024, 105 (Suppl 4S), S117–S314. [CrossRef]

- Abdel Kader, K. Symptoms with or because of Kidney Failure? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2022, 17, 475–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US Renal Data System 2023.

- Nitta, K.; Okada, K.; Yanai, M.; Takahashi, S. Aging and chronic kidney disease. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2013, 38, 109–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stenvinkel, P.; Larsson, T.E. Chronic kidney disease: a clinical model of premature aging. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013, 62, 339–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Fu, P.; Ma, L. Kidney fibrosis: from mechanisms to therapeutic medicines. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023, 8, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Leung Anthony, K.L. "PARPs. " Current Biology 2017, 27, R1256–R1258. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes-Gonçalves, G.; Costa-Pessoa, J.M.; Pimenta, R.; Tostes, A.F.; da Silva, E.M.; Ledesma, F.L.; Malheiros, D.M.A.C.; Zatz, R.; Thieme, K.; Câmara, N.O.S.; Oliveira-Souza, M. Evaluation of glomerular sirtuin-1 and claudin-1 in the pathophysiology of nondiabetic focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Sci Rep. 2023, 13, 22685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- He, Wenjuan, et al. "Sirt1 activation protects the mouse renal medulla from oxidative injury.". The Journal of clinical investigation 2010, 120, 1056–1068.

- Zhang, Y.; et al. Sirtuin 1 activation reduces transforming growth factor-β1-induced fibrogenesis and afords organ protection in a model of progressive, experimental kidney and associated cardiac disease. Am. J. Pathol. 2017, 187, 80–90. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.Z.; Wen, D.; Zhang, M.; Xie, Q.; Ma, L.; Guan, Y.; Ren, Y.; Chen, J.; Hao, C.M. Sirt1 activation ameliorates renal fibrosis by inhibiting the TGF-β/Smad3 pathway. J Cell Biochem. 2014, 115, 996–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Liu, Y.; Qin, X.; Chen, K.; Wang, R.; Yuan, L.; Chen, X.; Hao, C.; Huang, X. SIRT1 attenuates renal fibrosis by repressing HIF-2α. Cell Death Discov. 2021, 7, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cai, J.; Liu, Z.; Huang, X.; Shu, S.; Hu, X.; Zheng, M.; Tang, C.; Liu, Y.; Chen, G.; Sun, L.; Liu, H.; Liu, F.; Cheng, J.; Dong, Z. The deacetylase sirtuin 6 protects against kidney fibrosis by epigenetically blocking β-catenin target gene expression. Kidney Int. 2020, 97, 106–118, Epub 2019 Sep 17. Erratum in: Kidney Int. 2022, 101, 422. 10.1016/j.kint.2021.11.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Li, W.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, W.; Huang, H. SIRT6 overexpression retards renal interstitial fibrosis through targeting HIPK2 in chronic Kidney Disease. Front Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1007168. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cai, J.; Wang, T.; Zhou, Y.; Tang, C.; Liu, Y.; Dong, Z. Phosphorylation by GSK-3β increases the stability of SIRT6 to alleviate TGF-β-induced fibrotic response in renal tubular cells. Life Sci. 2022, 308, 120914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, L.; Yang, X.; Jian, Y.; Liu, J.; Ke, X.; Chen, S.; Yang, D.; Yang, D. SIRT3 deficiency exacerbates early-stage fibrosis after ischaemia-reperfusion-induced AKI. Cell Signal. 2022, 93, 110284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Zhang, J.; Yan, X.; Zhang, C.; Liu, H.; Shan, X.; Li, J.; Yang, Y.; Huang, C.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, Y.; Bu, P. SIRT3-KLF15 signaling ameliorates kidney injury induced by hypertension. Oncotarget. 2017, 8, 39592–39604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Xi, J.; Chen, Y.; Jing, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, C.; Hao, Z.; Zhang, L. Sirtuin 3 suppresses the formation of renal calcium oxalate crystals through promoting M2 polarization of macrophages. J Cell Physiol. 2019, 234, 11463–73. [Google Scholar]

- Huan-Huan Chen, Yi-Xiao Zhang, Jia-Le Lv, Yu-Yang Liu, Jing-Yi Guo, Lu Zhao, Yu-Xin Nan, Qi-Jun Wu, Yu-Hong Zhao. Role of sirtuins in metabolic disease-related renal injury. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2023, 161.

- Pushpakumar, Sathnur, et al. "Methylation-dependent antioxidant-redox imbalance regulates hypertensive kidney injury in aging.". Redox Biology 2020, 37, 101754.

- Jain, Sudhir, et al. "Age-related expression of human AT1R variants and associated renal dysfunction in transgenic mice.". American Journal of Hypertension 2018, 31, 1234–1242.

- Feng, Xiaomeng, et al. "SIRT3 deficiency sensitizes angiotensin-II-induced renal fibrosis.". Cells 2020, 9, 2510.

- Guo, Jian, et al. "Endothelial SIRT6 is vital to prevent hypertension and associated cardiorenal injury through targeting Nkx3. 2-GATA5 signaling.". Circulation Research 2019, 124, 1448–1461.

- Fan, Yanqin, et al. "Sirt6-mediated Nrf2/HO-1 activation alleviates angiotensin II-induced DNA DSBs and apoptosis in podocytes.". Food & function 2021, 12, 7867–7882.

- Chung, W.K.; Erion, K.; Florez, J.C.; Hattersley, A.T.; Hivert, M.F.; Lee, C.G.; McCarthy, M.I.; Nolan, J.J.; Norris, J.M.; Pearson, E.R.; Philipson, L.; McElvaine, A.T.; Cefalu, W.T.; Rich, S.S.; Franks, P.W. Precision Medicine in Diabetes: A Consensus Report From the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care. 2020, 43, 1617–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitada, M.; Kume, S.; Koya, D. Role of sirtuins in kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2014, 23, 75–79. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong Yifei, Lee Kyung, He John Cijang. SIRT1 is a potential drug target for treatment of diabetic kidney disease. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2018, 9, 624.

- Dong YJLiu, N.; Xiao, Z.; Sun, T.; Wu, S.H.; Sun, W.X.; Xu, Z.G.; Yuan, H. Renal protective effect of Sirtuin 1. J Diabetes Res. 2014, 2014, 843786. [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda, I.; Hasegawa, K.; Sakamaki, Y.; Muraoka, H.; Kawaguchi, T.; Kusahana, E.; Ono, T.; Kanda, T.; Tokuyama, H.; Wakino, S.; Itoh, H. Pre-emptive Short-term Nicotinamide Mononucleotide Treatment in a Mouse Model of Diabetic Nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021, 32, 1355–1370, Erratum in: J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021, 32, 2683. 10.1681/ASN.2021071000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lu, Zhihui, et al. "METTL14 aggravates podocyte injury and glomerulopathy progression through N6-methyladenosine-dependent downregulating of Sirt1.". Cell death & disease 2021, 12, 881.

- Qi, W.; Hu, C.; Zhao, D.; Li, X. SIRT1-SIRT7 in Diabetic Kidney Disease: Biological Functions and Molecular Mechanisms. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022, 13, 801303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shi, Jian-Xia, and Qin Huang. "Glucagon-like peptide-1 protects mouse podocytes against high glucose-induced apoptosis, and suppresses reactive oxygen species production and proinflammatory cytokine secretion, through sirtuin 1 activation in vitro.". Molecular Medicine Reports 2018, 18, 1789–1797.

- Wang, Yunfei, et al. "Sirt3 overexpression alleviates hyperglycemia-induced vascular inflammation through regulating redox balance, cell survival, and AMPK-mediated mitochondrial homeostasis.". Journal of Receptors and Signal Transduction 2019, 39, 341–349. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Zhang, L.; Hua, F.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, C.; Mi, X.; Qin, N.; Wang, J.; Zhu, A.; Qin, Z.; Zhou, F. FOXM1-activated SIRT4 inhibits NF-κB signaling and NLRP3 inflammasome to alleviate kidney injury and podocyte pyroptosis in diabetic nephropathy. Exp Cell Res. 2021, 408, 112863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Xiaojing, et al. "microRNA-20b contributes to high glucose-induced podocyte apoptosis by targeting SIRT7.". Molecular medicine reports 2017, 16, 5667–5674. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Shuang, et al. "SIRT2 affects cell proliferation and apoptosis by suppressing the level of autophagy in renal podocytes.". Disease Markers 2022, 2022, 4586198.

- Bian, Che, et al. "Association of SIRT6 circulating levels with urinary and glycometabolic markers in pre-diabetes and diabetes.". Acta Diabetologica 2021, 58, 1551–1562. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Fan, L.X.; Sweeney WEJr Denu, J.M.; Avner, E.D.; Li, X. Sirtuin 1 inhibition delays cyst formation in autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Clin Invest. 2013, 123, 3084–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- El Ters, M.; Zhou, X.; Lepping, R.J.; Lu, P.; Karcher, R.T.; Mahnken, J.D.; Brooks, W.M.; Winklhofer, F.T.; Li, X.; Yu, A.S.L. Biological Efficacy and Safety of Niacinamide in Patients With ADPKD. Kidney Int Rep. 2020, 5, 1271–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ozkan Kurtgoz, P. , Karakose, S., Cetinkaya, C.D. et al. Evaluation of sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) levels in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Int Urol Nephrol.

- Nie, H.; Hong, Y.; Lu, X.; Zhang, J.; Chen, H.; Li, Y.; et al. SIRT2 mediates oxidative stress-induced apoptosis of differentiated PC12 cells. Neuroreport 2014, 25, 838–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G.A. Roth, G.A. Mensah, C.O. Johnson, et al. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk factors, 1990-2019: update from the GBD 2019 study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 2982–3021.

- Alam, F.; Syed, H.; Amjad, S.; Baig, M.; Khan, T.A.; Rehman, R. Interplay between oxidative stress, SIRT1, reproductive and metabolic functions. Curr Res Physiol. 2021, 4, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hsu, C.P.; Zhai, P.; Yamamoto, T.; Maejima, Y.; Matsushima, S.; Hariharan, N.; Shao, D.; Takagi, H.; Oka, S.; Sadoshima, J. Silent information regulator 1 protects the heart from ischemia/reperfusion. Circulation 2010, 122, 2170–2182. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Porter, G.A.; Urciuoli, W.R.; Brookes, P.S.; Nadtochiy, S.M. SIRT3 deficiency exacerbates ischemia-reperfusion injury: implication for aged hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2014, 306, H1602–H1609. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- X.X. Wang, X.L. Wang, M.M. Tong, et al. SIRT6 protects cardiomyocytes against ischemia/reperfusion injury by augmenting FoxO3α-dependent antioxidant defense mechanisms. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2016, 111, 13.

- Alcendor, R.R.; Gao, S.; Zhai, P.; Zablocki, D.; Holle, E.; Yu, X.; Tian, B.; Wagner, T.; Vatner, S.F.; Sadoshima, J. Sirt1 regulates aging and resistance to oxidative stress in the heart. Circ Res 2007, 100, 1512–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaresan, N.R.; Gupta, M.; Kim, G.; Rajamohan, S.B.; Isbatan, A.; Gupta, M.P. Sirt3 blocks the cardiac hypertrophic response by augmenting Foxo3a-dependent antioxidant defense mechanisms in mice. J Clin Invest 2009, 119, 2758–2771. [Google Scholar]

- Sundaresan, N.R.; Vasudevan, P.; Zhong, L.; Kim, G.; Samant, S.; Parekh, V.; Pillai, V.B.; Ravindra, P.V.; Gupta, M.; Jeevanandam, V.; Cunningham, J.M.; Deng, C.X.; Lombard, D.B.; Mostoslavsky, R.; Gupta, M.P. The sirtuin SIRT6 blocks IGF-Akt signaling and development of cardiac hypertrophy by targeting c-Jun. Nat Med 2012, 18, 1643–1650. [Google Scholar]

- Lynn, E.G.; McLeod, C.J.; Gordon, J.P.; Bao, J.; Sack, M.N. SIRT2 is a negative regulator of anoxia-reoxygenation tolerance via regulation of 14-3-3 zeta and BAD in H9c2 cells. FEBS Lett 2008, 582, 2857–2862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong-Ping Liu, Ri Wen, Chun-Feng Liu, Tie-Ning Zhang, Ni Yang. Cellular and molecular biology of sirtuins in cardiovascular disease. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2023, 164, 114931, ISSN 0753–3322.

- Lu, Y.; Li, Y.; Xie, Y.; Bu, J.; Yuan, R.; Zhang, X. Exploring Sirtuins: New Frontiers in Managing Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2024, 25, 7740. [Google Scholar]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Čelutkienė, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: Developed by the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. (Engl. Ed.) 2022, 75, 523. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wu, Q.-J.; Zhang, T.-N.; Chen, H.-H.; Yu, X.-F.; Lv, J.-L.; Liu, Y.-Y.; Liu, Y.-S.; Zheng, G.; Zhao, J.-Q.; Wei, Y.-F.; et al. The sirtuin family in health and disease. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 402. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zeisberg EM, Tarnavski O, Zeisberg M, Dorfman AL, McMullen JR, Gustafsson E, Chandraker A, Yuan X, Pu WT, Roberts AB, Neilson EG, Sayegh MH, Izumo S, Kalluri R. Endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition contributes to cardiac fibrosis. Nat Med 2007, 13, 952–961.

- Zeisberg EM, Potenta SE, Sugimoto H, Zeisberg M, Kalluri R. Fibroblasts in kidney fibrosis emerge via endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition. J Am Soc Nephrol 2008, 19, 2282–2287.

- Kizu A, Medici D, Kalluri R. Endothelial-mesenchymal transition as a novel mechanism for generating myofibroblasts during diabetic nephropathy. Am J Pathol 2009, 175, 1371–1373.

- E. Pardali, G. E. Pardali, G. Sanchez-Duffhues, M.C. Gomez-Puerto P. Ten Dijke. TGF-beta-Induced endothelial-mesenchymal transition in fibrotic diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18.

- Li, Z.; Wang, F.; Zha, S.; Cao, Q.; Sheng, J.; Chen, S. SIRT1 inhibits TGF-β-induced endothelial-mesenchymal transition in human endothelial cells with Smad4 deacetylation. J Cell Physiol 2018, 233, 9007–9014. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.R.; Zheng, Y.J.; Zhang, Z.B.; Shen, W.L.; Li, X.D.; Wei, T.; Ruan, C.C.; Chen, X.H.; Zhu, D.L.; Gao, P.J. Suppression of Endothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition by SIRT (Sirtuin) 3 Alleviated the Development of Hypertensive Renal Injury. Hypertension 2018, 72, 350–360. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado-Valero, B.; Cachofeiro, V.; Martínez-Martínez, E. Fibrosis, the Bad Actor in Cardiorenal Syndromes: Mechanisms Involved. Cells. 2021, 10, 1824. [Google Scholar]

- Shestakova, M.V.; Iarek-Martynova, I.R.; Ivanishina, N.S.; Aleksandrov, A.A.; Dedov, I.I. Cardiorenal syndrome in type 1 diabetes mellitus: the role of endothelial dysfunction]. Kardiologiia. 2005, 45, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shestakova, M.V.; Jarek-Martynowa, I.R.; Ivanishina, N.S.; Kuharenko, S.S.; Yadrihinskaya, M.N.; Aleksandrov, A.A.; Dedov, I.I. Role of endothelial dysfunction in the development of cardiorenal syndrome in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2005, 68 Suppl1, S65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatamizadeh, P.; Fonarow, G.C.; Budoff, M.J.; Darabian, S.; Kovesdy, C.P.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K. Cardiorenal syndrome: pathophysiology and potential targets for clinical management. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2013, 9, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Wang, Z.; Wu, J.; Liu, M.; Li, M.; Sun, Y.; Huang, W.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, W.; Li, X.; Zhang, C.; Hong, F.; Li, N.; Nie, J.; Yi, F. Endothelial SIRT6 Is Vital to Prevent Hypertension and Associated Cardiorenal Injury Through Targeting Nkx3. 2-GATA5 Signaling. Circ Res. 2019, 124, 1448–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lumpuy-Castillo, J.; Amador-Martínez, I.; Díaz-Rojas, M.; Lorenzo, O.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J.; Sánchez- Lozada, L.G.; Aparicio-Trejo, O.E. Role of mitochondria in reno-cardiac diseases: A study of bioenergetics, biogenesis, and GSH signaling in disease transition. Redox Biol. 2024, 76, 103340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Iside, C. Sirtuin 1 activation by natural phytochemicals: an overview. Front Pharmacol 2020, 11, 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weichu Tao, Hu Zhang, Xia Jiang, Ning Chen. Resveratrol combats chronic diseases through enhancing mitochondrial quality. Food Science and Human Wellness. 2024, 13, 597–610, ISSN 2213. [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, D.; Capili, A.; Choi, M.E. Mitochondrial dysfunction in kidney injury, inflammation, and disease: Potential therapeutic approaches. Kidney Res Clin Pract. 2020, 39, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen-Hua Liu, Yanhong Zhang, Xue Wang, Xiao-Fang Fan, Yuqing Zhang, Xu Li, Yong-sheng Gong, Li-Ping Han. SIRT1 activation attenuates cardiac fibrosis by endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2019, 118.

- Yunzhuo Ren, Chunyang Du, Yonghong Shi, Jingying Wei, Haijiang Wu, Huixian Cui. The Sirt 1 activator, SRT1720, attenuates renal fibrosis by inhibiting CTGF and oxidative stress. Int J Mol Med, 2017, 39, 1317–1324.

- Vargas-Ortiz, K.; Pérez-Vázquez, V.; Macías-Cervantes, M.H. Exercise and Sirtuins: A Way to Mitochondrial Health in Skeletal Muscle. Int J Mol Sci. 2019, 20, 2717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.Y.; Choi, S.E.; Ha, E.S.; Lee, H.B.; Kim, T.H.; Han, S.J.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, D.J.; Kang, Y.; Lee, K.W. Role of liraglutide in brain repair promotion through Sirt1-mediated mitochondrial improvement in stroke. Int J Mol Med. 2019, 44, 1161–1171. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Liu, H.; Takagi, S.; Nitta, K.; Kitada, M.; Srivastava, S.P.; Takagaki, Y.; Kanasaki, K.; Koya, D. Renal protective effects of empagliflozin via inhibition of EMT and aberrant glycolysis in proximal tubules. JCI Insight. 2020, 5, e129034. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Osataphan, S.; Macchi, C.; Singhal, G.; Chimene-Weiss, J.; Sales, V.; Kozuka, C.; Dreyfuss, J.M.; Pan, H.; Tangcharoenpaisan, Y.; Morningstar, J. SGLT2 inhibition reprograms systemic metabolism via FGF21-dependent and -independent mechanisms. JCI Insight. 2019, 4, e123130. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Packer, M. Cardioprotective effects of sirtuin-1 and its downstream effectors: Potential role in mediating the heart failure benefits of SGLT2 (Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2) inhibitors. Circ Heart Fail. 2020, 13, e007197. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Mukherjee, M.; Kumar, A.; Sharma, G.; Tabassum, F.; Akhtar, S.; Imam, M.T.; Saeed Almalki, Z.S. Preliminary investigation on impact of intergenerational treatment of resveratrol endorses the development of 'super-pups'. Life Sci 2023, 314, 121322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirmiran, P.; Yuzbashian, E.; Rahbarinejad, P.; Asghari, G.; Azizi, F. Dietary Intakes of Total Polyphenol and Its Subclasses in Association with the Incidence of Chronic Kidney Diseases: A Prospective Population-based Cohort Study. [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Peng, W.; Hu, F.; Li, G. Association between dietary intake of flavonoid and chronic kidney disease in US adults: Evidence from NHANES 2007-2008, 2009-2010, and 2017-2018. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0309026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arisi, T.O.P.; da Silva, D.S.; Stein, E.; Weschenfelder, C.; de Oliveira, P.C.; Marcadenti, A.; Lehnen, A.M.; Waclawovsky, G. Effects of cocoa consumption on cardiometabolic risk markers: Protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.

- Najjar, R.S.; Turner, C.G.; Wong, B.J.; Feresin, R.G. Berry-Derived Polyphenols in Cardiovascular Pathologies: Mechanisms of Disease and the Role of Diet and Sex. Nutrients. 2021, 13, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).