Submitted:

13 March 2025

Posted:

14 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

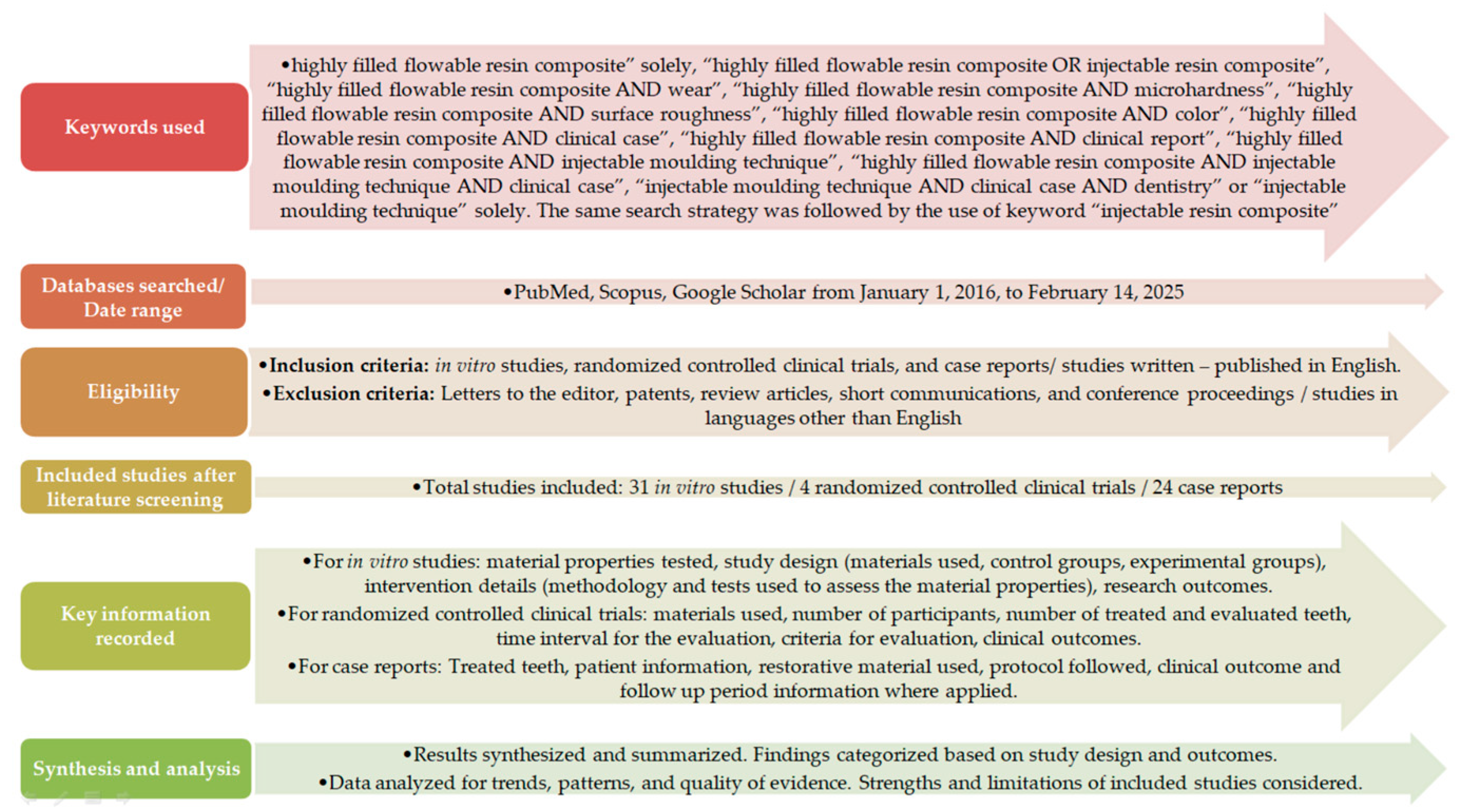

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Case Reports of Injectable Moulding Technique Using Flowable Resin Composites – Interpretation of the Clinical Outcome

- Despite the material per se, external factors such as medical record, intraoral temperature and humidity, acid consumption, grinding, poor oral hygiene, parafunctional behaviors, and polishing procedures are additional influential factors affecting clinical outcomes [52].

- Very short follow-up periods are applied. In order to draw clear conclusions on a technique or a material, long-term follow-up periods are essential.

- The initial evaluation of a restoration or restorative procedure and its behavior through time should be based on specific guidelines and criteria and should not be only assessed by the presence of stains and wear. These criteria include esthetic, functional, and biological parameters, such as anatomical form, surface luster, and surface staining, fracture of material, marginal adaptation, postoperative sensitivity, reoccurrence of dental caries, tooth integrity, and the adjacent mucosa evaluation [53,54,55].

- We should keep in mind that although clinical cases belong to the evidence – based scientific pyramid, their quality as well as their amount of evidence is weak [56]. The selection of a dental biomaterial in conjunction with a restorative technique should be made through well-designed randomized controlled clinical trials reinforced by in vitro studies and by the conduction of well–structured systematic reviews and metanalysis.

3.2. In Vitro and Randomized Control Clinical Studies on Highly Filled Flowable Resin Composites

3.2.1. Interpretation of the Results of the In Vitro Studies and Randomized Controlled Clinical Trials

4. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alzraikat, H.; Burrow, M.F.; Maghaireh, G.A.; Taha, N.A. Nanofilled resin composite properties and clinical performance: A review. Oper Dent. 2018, 43, 173–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vouvoudi, E.C. Overviews on the Progress of Flowable Dental Polymeric Composites: Their Composition, Polymerization Process, Flowability and Radiopacity Aspects. Polymers 2022, 14, 4182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baroudi, K.; Rodrigues, J.C. Flowable Resin Composites: A Systematic Review and Clinical Considerations. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015, 9, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayne, S.C.; Thompson, J.Y.; Swift, E.J.; Stamatiades, P.; Wilkerson, M. A characterization of first-generation flowable composites. J Am Dent Assoc. 1998, 129, 567–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terry, D.; Powers, J. Using injectable resin composite: Part one. Int Dent Afr. 2014, 5, 52–62. [Google Scholar]

- Perdigão, J.; Araujo, E.; Ramos, R.Q.; Gomes, G.; Pizzolotto, L. Adhesive dentistry: Current concepts and clinical considerations. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2021, 33, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasi, A.; Alnassar, T.; Chiche, G. Injectable technique for direct provisional restoration. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2018, 30, 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumino, N.; Tsubota, K.; Takamizawa, T.; Shiratsuchi, K.; Miyazaki, M.; Latta, M.A. Comparison of the wear and flexural characteristics of flowable resin composites for posterior lesions. Acta Odontol Scand. 2013, 71, 820–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badr, C.; Spagnuolo, G.; Amenta, F.; Khairallah, C.; Mahdi, S.S.; Daher, E.; Battineni, G.; Baba, N.Z.; Zogheib, T.; Qasim, S.S.B.; et al. A Two-Year Comparative Evaluation of Clinical Performance of a Nanohybrid Composite Resin to a Flowable Composite Resin. J. Funct. Biomater. 2021, 12, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, A.; Takamizawa, T.; Sugimura, R.; Tsujimoto, A.; Ishii, R.; Kawazu, M.; Saito, T.; Miyazaki, M. Interrelation among the handling, mechanical, and wear properties of the newly developed flowable resin composites. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2019, 89, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G-aenial Universal Injectable from, GC. Technical Guide. Available online: https://www.gc.dental/europe/sites/europe.gc.dental/files/products/downloads/gaenialuniversalinjectable/manual/MAN_G-aenial_Universal_Injectable_Technical_Manual_en.pdf (accessed on 4 September 2024).

- Shaalan, O.O.; Abou-Auf, E.; El Zoghby, A.F. Clinical evaluation of flowable resin composite versus conventional resin composite in carious and noncarious lesions: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Conserv Dent. 2017, 20, 380–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geštakovski, D. The injectable composite resin technique: Minimally invasive reconstruction of esthetics and function. Clinical case report with 2-year follow-up. Quintessence Int. 2019, 50, 712–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coachman, C.; De Arbeloa, L.; Mahn, G.; Sulaiman, T.A.; Mahn, E. An Improved Direct Injection Technique With Flowable Composites. A Digital Workflow Case Report. Oper Dent. 2020, 45, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosaka, K.; Tichy, A.; Motoyama, Y.; Mizutani, K.; Lai, W.J.; Kanno, Z.; Tagami, J.; Nakajima, M. Post-orthodontic recontouring of anterior teeth using composite injection technique with a digital workflow. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2020, 32, 638–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ypei Gia, N.R.; Sampaio, C.S.; Higashi, C.; Sakamoto, A.; Hirata, R. The injectable resin composite restorative technique: A case report. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2021, 33, 404–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés-Bretón Brinkmann, J.; Albanchez-González, M.I.; Lobato Peña, D.M.; García Gil, I.; Suárez García, M.J.; Peláez Rico, J. Improvement of aesthetics in a patient with tetracycline stains using the injectable composite resin technique: Case report with 24-month follow-up. Br Dent J. 2020, 229, 774–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosaka, K.; Tichy, A.; Hasegawa, Y.; Motoyama, Y.; Kanazawa, M.; Tagami, J.; Nakajima, M. Replacing mandibular central incisors with a direct resin-bonded fixed dental prosthesis by using a bilayering composite resin injection technique with a digital workflow: A dental technique. J Prosthet Dent. 2021, 126, 150–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ljubičić, M.; Živković, M. Multidisciplinary approach in treatment of spacing: Orthodontic treatment and partial ve-neers using the injectable composite resin technique. Serbian Dental Journal 2021, 68, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geštakovski, D. The injectable composite resin technique: Biocopy of a natural tooth - advantages of digital planning. Int J Esthet Dent. 2021, 16, 280–299. [Google Scholar]

- Hulac, S.; Kois, J.C. Managing the transition to a complex full mouth rehabilitation utilizing injectable composite. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2023, 35, 796–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peumans, Μ. Geštakovski, D.; Mattiussi, J.; Karagiannopoulos, K. Injection moulding technique with injectable composites: Quick fix or long-lasting solution? Int Dent Afr. 2023, 13, 14–22. [Google Scholar]

- Hosaka, K.; Tichy, A.; Yamauti, M.; Watanabe, K.; Kamoi, K.; Yonekura, K.; Foxton, R.; Nakajima, M. Digitally Guided Direct Composite Injection Technique with a Bi-layer Clear Mini-Index for the Management of Extensive Occlusal Caries in a Pediatric Patient: A Case Report. J Adhes Dent. 2023, 25, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhu, J.; Yang, X.; Gao, J.; Yu, H. Technique to restore the midline space of central incisors using a two-in-one template: A clinical report. J Prosthodont. 2023, 32, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villafuerte, K.R.V.; Obeid, A.T.; de Oliveira, N.A. Injectable Resin Technique as a Restorative Alternative in a Cleft Lip and Palate Patient: A Case Report. Medicina 2023, 59, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, M. Injectable composites in modern practice. Journal of the Irish Dental Association 2023, 69, 197–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, K.; Tichy, A.; Kamoi, K.; Hiasa, M.; Yonekura, K.; Tanaka, E.; Nakajima, M.; Hosaka, K. Restoration of a Microdont Using the Resin Composite Injection Technique With a Fully Digital Workflow: A Flexible 3D-printed Index With a Stabilization Holder. Oper Dent. 2023, 48, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shui, Y.; Wu, J.; Luo, T.; Sun, M.; Yu, H. Three dimensionally printed template with an interproximal isolation design guide consecutive closure of multiple diastema with injectable resin composite. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2024, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafeie, N.; Sampaio, C.S.; Hirata, R. Transitioning from injectable resin composite restorations to resin composite CAD/CAM veneers: A clinical report. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2024, 36, 1221–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muslimah, D.F.; Hasegawa, Y.; Antonin, T.; Richard, F.; Hosaka, K. Composite Injection Technique With a Digital Workflow: A Pragmatic Approach for a Protruding Central Incisor Restoration. Cureus. 2024, 16, e58712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branzan, R.; Taraboanta, I.; Tanasa, A.M.; Stoleriu, S.; Ghiorghe, A.C.; Pancu, G.; Georgescu, A.; Andra Taraboanta-Gamen, A.; Andrian, S. The use of flowable composite injection technique in a case of sever tooth wear. A case report. Int.J.Med.Dent. 2024, 28, 48–54. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, K.; Tanaka, E.; Kamoi, K.; Tichy, A.; Shiba, T.; Yonerakura, K.; Nakajima, M.; Han, R.; Hosaka, K. A dual composite resin injection molding technique with 3D-printed flexible indices for biomimetic replacement of a missing mandibular lateral incisor. J Prosthodont Res. 2024, 68, 667–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathod, P.; Patel, A.; Mankar, N.; Chandak, M.; Ikhar, A. Enhancing Aesthetics and Functionality of the Teeth Using Injectable Composite Resin Technique. Cureus. 2024, 16, e59974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyahya, Y.; Alrebdi, A.; Farah, R.I.; Albazei, S.S.F. Esthetic Rehabilitation of Congenitally Peg-Shaped Lateral Incisors Using the Injectable Composite Resin Technique: A Clinical Report. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2024, 16, 1883–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Wei, J.; Anniwaer, A.; Huang, C. Esthetic rehabilitation of labial tooth defects caused by caries of the anterior teeth using a composite resin injection technique with veneer-shaped 3D printing indices. J Prosthodont Res. 2025, 69, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spadoni, D.; Valeri, C.; Quinzi, V.; Schneider Moser, U.; Marzo, G. Advancing Orthodontic Aesthetics: Exploring the Potential of Injectable Composite Resin Techniques for Enhanced Smile Transformations. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammannato, R.; Ferraris, F.; Marchesi, G. The “index technique” in worn dentition: A new and conservative approach. Int J Esthet Dent 2015, 10, 68–99. [Google Scholar]

- Ammannato, R.; Rondoni, D.; Ferraris, F. Update on the “index technique” in worn dentition: A no-prep restorative approach with a digital workflow. Int J Esthet Dent 2018, 13, 516–537. [Google Scholar]

- Kouri, V.; Moldovani, D.; Papazoglou, E. Accuracy of Direct Composite Veneers via Injectable Resin Composite and Silicone Matrices in Comparison to Diagnostic Wax-Up. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, D.A.; Powers, J.M.; Mehta, D.; Babu, V. A predictable resin composite injection technique, part 2. Dent. Today. 2014, 33, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Jurado, C.A.; Tinoco, J.V.; Tsujimoto, A.; Barkmeier, W.; Fischer, N.; Markham, M. Clear matrix use for composite resin core fabrication. Int J Esthet Dent. 2020, 15, 108–117. [Google Scholar]

- Tolotti, T.; Sesma, N.; Mukai, E. Evolution of the Guided Direct Composite Resin Technique in Restorative Dentistry: A Systematic Review. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2024, 23, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beautifil Flow Plus: Safety Data Sheet. Available online: https://www.shofu.com/wp-content/uploads/Beautifil-Flow-Plus-SDS-US-Version-11.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2024).

- Kooi, T.J.; Tan, Q.Z.; Yap, A.U.; Guo, W.; Tay, K.J.; Soh, M.S. Effects of food-simulating liquids on surface properties of giomer restoratives. Oper Dent. 2012, 37, 665–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tetric EvoFlow. Instructions for use. Available online: https://www.ivoclar.com/en_li/eifu?document-id=36624&show-detail=1 (accessed on 5 September 2024).

- G-aenial Universal Injectable. Available online: https://www.gc.dental/europe/sites/europe.gc.dental/files/products/downloads/gaenialuniversalinjectable/ifu/IFU_G-aenial_Universal_Injectable_W.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2024).

- G-aenial Universal Flo. Available online: https://www.gc.dental/europe/sites/europe.gc.dental/files/products/downloads/gaenialuniversalflo/ifu/IFU_G-aenial_Universal_Flo_W.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2024).

- Clearfil Majesty ES Flow. Available online: https://www.kuraraynoritake.eu/media/pdfs/IFU_CLEARFIL_MAJESTY_ES_Flow_1561R973R-007_WEB_22.pdf (accessed on 5th September 2024).

- Beautifil Injectable X: Safety Data Sheet. Available online: https://www.shofu.com.sg/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/SDS_BEAUTIFIL-Injectable-XVer.2.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Tetric N-flow. Instructions for use. Available online: https://www.ivoclar.com/en_in/eifu?document-id=45433&show-detail=1 (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Estelite Universal Flow. Product Instructions. Available online: https://www.tokuyama-us.com/estelite-universal-flow-dental-composite/ (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Bonsor, S.J.; Pearson, G.J. A clinical guide to applied dental materials, 1st ed.; Churchill Livingstone Elsevier: London, UK, 2012; pp. 69–86. [Google Scholar]

- Hickel, R.; Peschke, A.; Tyas, M.; Mjör, I.; Bayne, S.; Peters, M.; Hiller, K.A.; Randall, R.; Vanherle, G.; Heintze, S.D. FDI World Dental Federation: Clinical criteria for the evaluation of direct and indirect restorations-update and clinical examples. Clin Oral Investig. 2010, 14, 349–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larasati, N.; Rizal, M.F.; Fauziah, E. Comparing modified USPHS and FDI criteria for the assessment of glass ionomer restorations in primary molars utilising clinical and photographic evaluation. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2024, 25, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquillier, T.; Doméjean, S.; Le Clerc, J.; Chemla, F.; Gritsch, K.; Maurin, J.C.; Millet, P.; Pérard, M.; Grosgogeat, B.; Dursun, E. The use of FDI criteria in clinical trials on direct dental restorations: A scoping review. J Dent. 2018, 68, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colwill, M.; Baillie, S.; Pollok, R.; Poullis, A. Using clinical cases to guide healthcare. World J Clin Cases. 2024, 12, 1555–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Νair, S.R.; Niranjan, N.T.; Jayasheel, A.; Suryakanth, D.B. Comparative Evaluation of Colour Stability and Surface Hardness of Methacrylate Based Flowable and Packable Composite -In vitro Study. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017, 11, ZC51–ZC54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, G.; Zhao, L.; Wang, J.; Kunzelmann, K.H. Surface properties and color stability of dental flowable composites influenced by simulated toothbrushing. Dent Mater J. 2018, 37, 717–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ujiie, M.; Tsujimoto, A.; Barkmeier, W.W.; Jurado, C.A.; Villalobos-Tinoco, J.; Takamizawa, T.; Latta, M.A.; Miyazaki, M. Comparison of occlusal wear between bulk-fill and conventional flowable resin composites. Am J Dent. 2020, 33, 74–78. [Google Scholar]

- Korkut, B.; Haciali, C. Color Stability of Flowable Composites in Different Viscosities. Clin Exp Health Sci. 2020, 10, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimatani, Y.; Tsujimoto, A.; Barkmeier, W.W.; Fischer, N.G.; Nagura, Y.; Takamizawa, T.; Latta, M.A.; Miyazaki, M. Simulated Cuspal Deflection and Flexural Properties of Bulk-Fill and Conventional Flowable Resin Composites. Oper Dent. 2020, 45, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsujimoto, A.; Irie, M.; Teixeira, E.C.N.; Jurado, C.A.; Maruo, Y.; Nishigawa, G.; Matsumoto, T.; Garcia-Godoy, F. Relationships between Flexural and Bonding Properties, Marginal Adaptation, and Polymerization Shrinkage in Flowable Composite Restorations for Dental Application. Polymers 2021, 13, 2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niyomsujarit, N.; Worahan, A.; Chaichalothorn, M. Effects of cyclic acid challenge on the surface roughness of various flowable resin composites. M Dent J 2021, 41, 187–196. [Google Scholar]

- Degirmenci, A.; Degirmenci, B.U.; Salameh, M. Long-Term Effect of Acidic Beverages on Dental Injectable Composite Resin: Microhardness, Surface Roughness, Elastic Modulus, and Flexural Strength Patterns. Strength Mater 2022, 54, 331–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludovichetti, F.S.; Lucchi, P.; Zambon, G.; Pezzato, L.; Bertolini, R.; Zerman, N.; Stellini, E.; Mazzoleni, S. Depth of Cure, Hardness, Roughness and Filler Dimension of Bulk-Fill Flowable, Conventional Flowable and High-Strength Universal Injectable Composites: An In Vitro Study. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafarpour, D.; Ferooz, R.; Ferooz, M.; Bagheri, R. Physical and Mechanical Properties of Bulk-Fill, Conventional, and Flowable Resin Composites Stored Dry and Wet. Int J Dent. 2022, 2022, 7946239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoramian Tusi, S.; Hamdollahpoor, H.; Mohammadi Savadroodbari, M.; Sheikh Fathollahi, M. Comparison of polymerization shrinkage of a new bulk-fill flowable composite with other composites: An in vitro study. Clin Exp Dent Res. 2022, 8, 1605–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turk, S.; Erden Kayalidere, E.; Celik, E.U.; Yasa, B. In vitro wear resistance of conventional and flowable composites containing various filler types after thermomechanical loading. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2024, 36, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uctasli, M.; Garoushi, S.; Uctasli, M.; Vallittu, P.K.; Lassila, L. A comparative assessment of color stability among various commercial resin composites. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsahn, N.A.; El-Damanhoury, H.M.; Shirazi, Z.; Saleh, A.R.M. Surface Properties and Wear Resistance of Injectable and Computer-Aided Design/Computer Aided Manufacturing-Milled Resin Composite Thin Occlusal Veneers. Eur J Dent. 2023, 17, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Nassar, M.; Elsayed, M.A.; Jameel, D.B.; Ahmad, T.T.; Rahman, M.M. In Vitro Optical and Physical Stability of Resin Composite Materials with Different Filler Characteristics. Polymers 2023, 15, 2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elgammal, Y.A.; Temirek, M.M.; Hassanein, O.E.; Abdelaziz, M.M. The Effect of Different Finishing and Polishing Systems on Surface Properties of New Flowable Bulk-fill Resin Composite. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2023, 24, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vulović, S.; Stašić, J.N.; Ilić, J.; Todorović, M.; Jevremović, D.; Milić-Lemić, A. Effect of different finishing and polishing procedures on surface roughness and microbial adhesion on highly-filled composites for injectable mold technique. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2023, 35, 917–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degirmenci, A.; Pehlivan, I.E.; Degirmenci, B.U. Effects of polishing procedures on optical parameters and surface roughness of composite resins with different viscosities. Dent Mater J. 2023, 42, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczesio-Wlodarczyk, A.; Garoushi, S.; Vallittu, P.; Bociong, K.; Lassila, L. Polymerization shrinkage of contemporary dental resin composites: Comparison of three measurement methods with correlation analysis. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2024, 152, 106450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Bai, X.; Xu, M.; Zhou, T.; Loh, Y.M.; Wang, C.; Pow, E.H.N.; Tsoi, J.K.H. The mechanical, wear, antibacterial properties and biocompatibility of injectable restorative materials under wet challenge. J Dent. 2024, 146, 105025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, T.; Pow, E.H.N.; Tsoi, J.K.H. The chemical and optical stability evaluation of injectable restorative materials under wet challenge. J Dent. 2024, 146, 105031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyashita-Kobayashi, A.; Haruyama, A.; Nakamura, K.; Wu, C.-Y.; Kuroiwa, A.; Yoshinari, N.; Kameyama, A. Changes in Gloss Alteration, Surface Roughness, and Color of Direct Dental Restorative Materials after Professional Dental Prophylaxis. J. Funct. Biomater. 2024, 15, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basheer, R.R.; Hasanain, F.A.; Abuelenain, D.A. Evaluating flexure properties, hardness, roughness and microleakage of high-strength injectable dental composite: An in vitro study. BMC Oral Health. 2024, 24, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczesio-Wlodarczyk, A.; Garoushi, S.; Vallittu, P.; Bociong, K.; Lassila, L. Polymerization shrinkage stress of contemporary dental composites: Comparison of two measurement methods. Dent Mater J. 2024, 43, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabi, H.; Denny, M.; Karagiannopoulos, K.; Petridis, H. Comparison of Flexural Strength and Wear of Injectable, Flowable and Paste Composite Resins. Materials 2024, 17, 4749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tüter Bayraktar, E.; Kızıl Öztürk, E.; Saygılı, C.C.; Türkmen, C.; Korkut, B. Fluorescence and color adjustment potentials of paste-type and flowable resin composites in cervical restorations. Clin Oral Investig. 2024, 28, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerges, P.; Labib, M.; Nabih, S.; Moussa, M. Fracture resistance of injectable resin composite versus packable resin composite in class II cavities: An in vitro study. Journal of Stomatology. 2024, 77, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checchi, V.; Generali, L.; Corciolani, L.; Breschi, L.; Mazzitelli, C.; Maravic, T. Wear and roughness analysis of two highly filled flowable composites. Odontology 2024, 113, 724–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francois, P.; Attal, J.P.; Fasham, T.; Troizier-Cheyne, M.; Gouze, H.; Abdel-Gawad, S.; Le Goff, S.; Dursun, E.; Ceinos, R. Flexural Properties, Wear Resistance, and Microstructural Analysis of Highly Filled Flowable Resin Composites. Oper Dent. 2024, 49, 597–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vulović, S.; Blatz, M.B.; Bukorović, J.; Živković, N.; Todorović, A.; Vencl, A.; Milić Lemić, A. Effect of acidic media on surface characteristics of highly filled flowable resin-based composites: An in vitro study. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2024, 2024, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitasako, Y.; Sadr, A.; Burrow, M.F.; Tagami, J. Thirty-six month clinical evaluation of a highly filled flowable composite for direct posterior restorations. Aust Dent J. 2016, 61, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, L.; Hua, L.; Guan, R.; Hou, B. Randomized controlled clinical trial of a highly filled flowable composite in non-carious cervical lesions: 3-year results. Clin Oral Investig. 2021, 25, 5955–5965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elderiny, H.M.; Khallaf, Y.S.; Akah, M.M.; Hassanein, O.E. Clinical Evaluation of Bioactive Injectable Resin Composite vs Conventional Nanohybrid Composite in Posterior Restorations: An 18-Month Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2024, 25, 794–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hançer Sarıca, S.; Arslan, S.; Balkaya, H. Comparison of the 2-year clinical performances of class II restorations using different restorative materials. Clin Oral Investig. 2025, 29, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, H.; Sun, H.; Liu, Y.; Liu, W.; Su, B.; Li, S. The Development of Filler Morphology in Dental Resin Composites: A Review. Materials 2021, 14, 5612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, X.; Yang, J.; et al. Micromechanical interlocking structure at the filler/resin interface for dental composites: A review. Int J Oral Sci. 2023, 15, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Kim, H.C.; Hur, B.; Park, J.K. Surface roughness and color stability of various composite resins. J Korean Acad Conserv Dent 2007, 32, 542–549. [Google Scholar]

- Draughn, R.A.; Harrison, A. Relationship between abrasive wear and microstructure of composite resins. J Prosthet Dent. 1978, 40, 220–224. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marghalani, H.Y. Effect of filler particles on surface roughness of experimental composite series. J Appl Oral Sci. 2010, 18, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuelenain, D.A.; Neel, E.A.A.; Al-Dharrab, A. Surface and mechanical properties of different dental composites. Austin J Dent. 2015, 2, 1019. [Google Scholar]

- Filtek Z350XT. Technical Product Guide. Available online: https://multimedia.3m.com/mws/media/1363105O/3m-filtek-z350-xt-universal-restorative-tpp-la-apac.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Oivanen, M.; Keulemans, F.; Garoushi, S.; Vallittu, P.K.; Lassila, L. The effect of refractive index of fillers and polymer matrix on translucency and color matching of dental resin composite. Biomater Investig Dent. 2021, 8, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Lee, Y.K. Differences in color, translucency and fluorescence between flowable and universal resin composites. J Dent. 2008, 36, 840–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.K.; Lim, B.S.; Rhee, S.H.; Yang, H.C.; Powers, J.M. Color and translucency of A2 shade resin composites after curing, polishing and thermocycling. Oper Dent 2005, 30, 436–442. [Google Scholar]

- Soliman, H.A.N.; Elkholany, N.R.; Hamama, H.H.; El-Sharkawy, F.M.; Mahmoud, S.H.; Comisi, J.C. Effect of Different Polishing Systems on the Surface Roughness and Gloss of Novel Nanohybrid Resin Composites. Eur J Dent. 2021, 15, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefferies, S.R. Abrasive finishing and polishing in restorative dentistry: A state-of-the-art review. Dent Clin North Am 2007, 51, 379–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadas, M. The effect of different beverages on the color and translucency of flowable composites. Scanning. 2016, 38, 701–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.H.; Ong, J.L.; Okuno, O. The effect of filler loading and morphology on the mechanical properties of contemporary composites. J Prosthet Dent. 2002, 87, 642–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.K. Influence of filler on the difference between the transmitted and reflected colors of experimental resin composites. Dent Mater. 2008, 24, 1243–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marghalani, H.Y. Effect of filler particles on surface roughness of experimental composite series. J Appl Oral Sci. 2010, 18, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, P.; Yang, S.M.; Xu, Y.X.; Wang, X.Y. Surface roughness and gloss alteration of polished resin composites with various filler types after simulated toothbrush abrasion. J Dent Sci. 2023, 18, 1016–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawlus, P.; Reizer, R.; Wieczorowski, M. Functional Importance of Surface Texture Parameters. Materials 2021, 14, 5326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turssi, C.P.; Ferracane, J.L.; Ferracane, L.L. Wear and fatigue behavior of nano-structured dental resin composites. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2006, 78, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlay, N.; Hahnel, S.; Dowling, A.H.; Fleming, G.J.P. The in vitro wear behavior of experimental resin-based composites derived from a commercial formulation. Dent Mater. 2013, 29, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osiewicz, M.A.; Werner, A.; Roeters, F.J.M.; Kleverlaan, C.J. Wear of direct resin composites and teeth: Considerations for oral rehabilitation. EurJ Oral Sci. 2019, 127, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirică, I.C.; Furtos, G.; Bâldea, B.; Lucaciu, O.; Ilea, A.; Moldovan, M.; Câmpian, R.-S. Influence of Filler Loading on the Mechanical Properties of Flowable Resin Composites. Materials 2020, 13, 1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heintze, S.D.; Reichl, F.X.; Hickel, R. Wear of dental materials: Clinical significance and laboratory wear simulation methods -A review. Dent Mater J. 2019, 38, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerasmart. Instructions for Use. Available online: https://www.gc.dental/america/sites/america.gc.dental/files/products/downloads/cerasmart/ifu/cerasmart-ifu.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Sideridou, I.; Tserki, V.; Papanastasiou, G. Effect of chemical structure on degree of conversion in light-cured dimethacrylate-based dental resins. Biomaterials. 2002, 23, 1819–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratap, B.; Gupta, R.K.; Bhardwaj, B.; Nag, M. Resin based restorative dental materials: Characteristics and future perspectives. Jpn Dent Sci Rev. 2019, 55, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCabe, J.F.; Rusby, S. Water absorption, dimensional change and radial pressure in resin matrix dental restorative materials. Biomaterials. 2004, 25, 4001–4007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sideridou, I.D.; Karabela, M.M.; Vouvoudi, E.C. Dynamic thermomechanical properties and sorption characteristics of two commercial light cured dental resin composites. Dent Mater. 2008, 24, 737–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gajewski, V.E.S. Monomers used in resin composites: Degree of conversion, mechanical properties and water sorption/solubility. Braz. Dent. J. 2012, 23, 508–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imazato, S.; Tarumi, H.; Kato, S.; Ebi, N.; Ehara, A.; Ebisu, S. Water Sorption, Degree of Conversion, and Hydrophobicity Resins containing Bis-GMA and TEGDMA. Dent. Mater. J. 1999, 19, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczesio-Wlodarczyk, A.; Kopacz, K.; Szynkowska-Jozwik, M.I.; Sokolowski, J.; Bociong, K. An Evaluation of the Hydrolytic Stability of Selected Experimental Dental Matrices and Composites. Materials 2022, 15, 5055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goņalves, F.; Kawano, Y.; Pfeifer, C.; Stansbury, J.W.; Braga, R.R. Influence of BisGMA, TEGDMA, and BisEMA contents on viscosity, conversion, and flexural strength of experimental resins and composites. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2009, 117, 442–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczesio-Wlodarczyk, A.; Domarecka, M.; Kopacz, K.; Sokolowski, J.; Bociong, K. An Evaluation of the Properties of Urethane Dimethacrylate-Based Dental Resins. Materials 2021, 14, 2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sideridou, I.; Tserki, V.; Papanastasiou, G. Study of water sorption, solubility and modulus of elasticity of light-cured dimethacrylate-based dental resins. Biomaterials. 2003, 24, 655–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleming, P.S.; Lynch, C.D.; Pandis, N. Randomized controlled trials in dentistry: Common pitfalls and how to avoid them. J Dent. 2014, 42, 908–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Treated teeth | Patient record | Restorative material | Protocol | Follow up / Clinical outcome | Author/Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 maxillary anterior teeth | 22 years old/ male | Beautiful Flow Plus F03 (Shofu Inc, Kyoto, Japan) | Analog workflow (one transparent silicon index and individual space holders from mock-ups) | 2-year follow-up → No soft tissue inflammation or significant wear | Gestakovski et al., 2019 [13] |

| 6 anterior teeth | 28 years old/ female | Tetric Evoflow (Ivoclar Vivadent, Lichtenstein) | Partially digital workflow (two transparent silicone indices based on the 3D printing models) | No follow-up period Excellent initial clinical outcomes |

Coachman et al.,2020 [14] |

| post-orthodontic recontouring of 4 maxillaty anterior teeth | 15 years old/ female | G-ænial Universal Injectable (GC, Japan) | Partially digital workflow (one transparent silicon index based on 3D printing models) | 5-month follow-up → no signs of wear and no defects | Hosaka et al., 2020 [15] |

| 8 maxillary teeth (upper right to left second premolars) | 28 years old/ female | G-aenial Universal Flo (GC, Japan) | Analog workflow (one transparent silicone index covered by 1 mm acetate plate expanded to adjacent teeth to achieve more stable fitting) | 1-year follow-up → staining of restoration and the tooth – material interface / presence of voids | Ypei Gia et al., 2020 [16] |

| 16 teeth with generalised tetracycline dental stains |

52 years old/ female | G-ænial Universal Injectable (GC, Japan) | Analog workflow (one transparent silicone index) | 2-year follow-up → no gingival infammation, bleeding on probing or wear | Cortés-Bretón Brinkmann et al., 2020 [17] |

| 2 missing mandibular incisors replaced with a direct bilayered resin bonded fixed dental prosthesis |

No information available | everX Flow for dentin and G-ænial Universal Injectable for enamel (GC Corp, Tokyo, Japan) |

Partially digital workflow: two 3d-printed casts (1st: dentin cast/ 2nd: anatomic wax-up cast) and two transparent silicon indices (Exaclear, GC) | 3-month follow-up → No signs of wear or soft tissue inflammation |

Hosaka et al., 2021 [18] |

| 4 maxillary anterior teeth (lateral incisors and canines) | 32 years old/ male | G-ænial Universal Injectable (GC, Japan) | Analog workflow (one transparent silicon index and stoppers made by C – silicone on the impression tray) | No follow-up period Excellent initial performance |

Ljubičić et al, 2021 [19] |

| maxillary lateral incisor and maxillary first premolar | 25 years old/ female | G-ænial Universal Injectable (GC, Japan) |

Partially digital workflow (one tansparent silicone index based on the 3D printed wax-up + two putty silicone stoppers) | 10-month follow-up → no wear, discoloration or periodontal problems | Gestakovski, 2021 [20] |

| transitional treatment of a complex full mouth rehabilitation | 53 years old/ male | G-aenial Universal Injectable (GC, Japan) | Analog workflow (two transparent silicon indices for each arch) | 6-month follow-up → no signs of tissue inflammation or wear |

Hulac et al., 2023 [21] |

| 4 clinical cases of: a. General wear in upper and lower jaw b. Six maxillary anterior teeth c. Full mandibular arch treatment d. Six maxillary anterior teeth |

No information except of the 4th case : 45 years old/ male |

G-ænial Universal Injectable (GC, Japan) | either digital or analog workflow either one or two indices |

12-month-, 20-month- and 24-month follow-up → smooth and shiny surfaces, absence of occlusal wear, chipping, marginal discoloration or tissue inflammation | Peumans et al., 2023 [22] |

| extensive posterior occlusal cavities | 13 years old/ female | Clearfil ES Flow Universal, (Kuraray Noritake, Tokyo, Japan) | Digital workflow (bi-layer clear mini-index with hard outer plastic layer and elastic inner silicone layer) | 1-year follow-up → Excellent outcome | Hosaka et al., 2023 [23] |

| symmetrical restoration of two central incisors | 50 years old/ female | Beautifil Flow Plus F00 (Shofu, Kyoto, Japan | Digital workflow (one custom-designed, two-in-one digital template) | No follow-up | Wu et al., 2023 [24] |

| re-recontouring of maxillary premolars to canines | 21 years old/ female | Tetric N-Flow (Ivoclar Vivadent, Schaan, Lichtenstein) |

Analog workflow (one transparent index) | 1-year follow-up → No marginal discoloration or fracture | Villafuerte et al., 2023 [25] |

| 2nd upper right premolar to upper left canine | 34 years old/ female | Not mentioned | Partially digital workflow (one transparent matrix based on digital wax up) | 1-year follow-up → no chipping and minimal staining | Healy, 2023 [26] |

| a microdont maxillary lateral incisor | 18 years old/ male | Clearfil ES Flow Universal (Kuraray Noritake, Japan) | Digital workflow (one 3d printed index including only two adjacent to the microdont lateral incisor teeth and labial and palatal extensions + digital stabilization holder) | 6-month follow-up → Excellent outcome | Watanabe et al., 2023 [27] |

| multiple diastema closure (6 teeth) | 41 years old/ female | Beautifil Flow Plus F00 (Shofu, Kyoto, Japan) | Digital workflow (3D-printed index with interproximal matrices to isolate interproximal contact areas) | 10-month follow-up → no signs of wear and soft tissue inflammation | Shui et al., 2024 [28] |

| 6 lower anterior teeth | 36 years old/ male | G-aenial Universal Flo (GC, Tokyo, Japan) |

Analog workflow (one transparent silicon index) | Annual follow-ups for 4 years → staining in the tooth – composite interface and chippings repaired every year | Rafeie et al., 2024 [29] |

| maxillary right central incisor | 42 years old/ male | Clearfil ES Flow Universal (Kuraray Noritake, Tokyo, Japan) | Partially digital workflow (one transparent silicone index based on 3D printed models) | 3-year follow-up → excellent clinical outcome | Muslimah et al., 2024 [30] |

| full mouth rehabilitation | 57 years old/ male | G-aenial Universal Injectable (GC, Tokyo, Japan) |

Partially digital workflow (one transparent silicone index based on 3D printing wax up models) | 1-year follow-up → No defects | Branzan et al., 2024 [31] |

| Replacement of a missing mandibular lateral incisor with direct composite resin-bonded fixed partial denture |

34 years old/ female | Estelite Universal Flow, (Tokuyama Dental Corp., Tokyo, Japan ) | Digital workflow (two 3D-printed indices representing the dentin layer index and the outer enamel layer index + stabilization holder) | 1-year follow-up → excellent treatment outcomes | Watanabe et al., 2024 [32] |

| six maxillary anterior teeth | 34 years old/ female |

Beautifil Injectable, (Shofu, Kyoto, Japan) | Analog workflow (one transparent silicone index) | 12-month follow-up → No wear, postoperative sensitivity, soft tissue inflammation |

Rathod et al., 2024 [33] |

| peg-shaped and malformed upper lateral incisors |

24 years old/ male | Beautifil Flow Plus F03 (Shofu, Kyoto, Japan) | Analog workflow (one transparent silicone index) | No follow-up | Alyahya et al., 2024 [34] |

| labial tooth defects caused by caries | 18 years old/ female | Beautifil Flow Plus F00; (Shofu, Kyoto, Japan) |

Digital workflow (veneer-shaped 3D printing indices) | 1-year follow-up → no signs of soft tissue inflammation or caries | Zhu et al., 2025 [35] |

| maxillary lateral incisors in two paediatric patients | 12.6 years old/ female 12.3 years old/ male |

G-ænial Universal Injectable (GC, Tokyo, Japan) | Digital workflow (one triple-layer transparent silicone index) | 6-year follow-up → no bleeding, staining or periodontal inflammation (Clinical case 1) 2-year follow up → no bleeding, no color change (Clinical case 2) |

Spadoni et al., 2025 [36] |

| Flowable Composite Resin | Composition |

|---|---|

| Beautifil Flow Plus P03 or P00 (Shofu Inc., Kyoto, Japan) | 15 – 25 % by weight Bis-GMA, 10 – 20 %by weight TEGDMA S-PRG (surface pre reacted glass ionomer) filler based on 50 – 60 % by weight fluoroboroaluminosilicate glass, 1 – 5% by weight SiO2 and 1 – 5% by weight Al2O3, polymerization initiator, pigments and others. Particle size range: 0.01 to 4.0 μm Mean particle size: 0.8 μm [43,44] |

| Tetric Evoflow (Ivoclar Vivadent AG, Schaan, Lichtenstein) | Bis-GMA, UDMA, copolymer, barium glass, ytterbium trifluoride, Si-Zr mixed oxide, Inorganic filler content: 58% by weight / 30.7 - 33.7% by volume Particle size range: 0.11 μm to 15.5 μm [45] |

| G-aenial Universal Injectable (GC Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) | Dimethacrylate monomers and 69% by weight and approximately 50% by volume barium glass and silica fillers. Particle size range: 0.01 - 0.5 μm [46] |

| G-aenial Universal Flo (GC Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) | Dimethacrylate monomers and 69% by weight and approximately 50% by volume strontium glass and silica fillers. Particle size range: 0.01 - 1.0 μm [47] |

| Clearfil Majesty ES flow (Kuraray Noritake Dental, Tokyo, Japan) | Dimethacrylates and silanized barium glass and silica filler particles. Inorganic filler content: 48 to 64% by volume. Particle size range: 0.18 μm to 3.5 μm [48] |

| Beautifil Injectable X (Shofu Inc., Kyoto, Japan) | Bis-GMA, TEGDMA, Bis-MPEPP, S-PRG filler based on fluoroboroaluminosilicate glass, polymerization initiator, pigments and others. Inorganic filler content: 50-60% by weight [49] |

| Tetric N-Flow (Ivoclar Vivadent AG, Schaan, Lichtenstein) | Bis-GMA, UDMA, TEGDMA, ytterbium trifluoride, barium glass, bariumaluminium fluorosilicate glass, Si-Zr mixed oxide. Inorganic filler content: 38 – 40% by volume. Particle size range: 0.03 μm to 15.5 μm [50] |

| Estelite Universal Flow, Medium Viscosity (Tokuyama Dental Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) | Dimethacrylates (Bis-GMA, Bis-MPEPP, TEGDMA, UDMA) and spherical silica-zirconia filler and composite filler Inorganic filler content: 71% by weight/ 57% by volume Mean particle size: 200 nm Particle size range: 100 to 300 nm [51] |

| Parameters Tested | Type of Specimens/Type of Control Groups/Procedures | Tests | Conclusions | Author/Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| color stability - surface hardness |

(1) G-aenial Universal Flo (GC Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) (2) Filtek Z350XT (3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN, USA) (3) Tetric N Ceram (Ivoclar Vivadent AG, Schaan, Lichtenstein) immersion in coffee for 72 hours + tooth brushing simulation |

(a) Spectrophotometer measurements every 72 hours for 3 weeks (b) Microhardness tester |

color stability and surface hardness: Filtek Z350XT > Tetric N Ceram > G-aenial Universal Flo Inferior properties of G-aenial Universal Flo |

Nair et al., 2017 [57] |

| surface gloss - surface roughness - color stability |

(1) four traditional flowable composites: a. GrandioSO Flow (VOCO GmbH, Cuxhaven, Germany), b. Arabesk Flow (VOCO GmbH, Cuxhaven, Germany) c. Kerr Revolution Formula 2 (Kerr, Orange, CA, USA) d. Gradia Direct LoFlo (GC Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) (2) one self-adhering flowable composite: Kerr Vertise Flow (Kerr, Orange, CA, USA) (3) one universal injectable composite: G-ænial Universal Flo Experimental groups: toothbrushing simulation (Willytec, Munich, Germany) Control groups: No toothbrushing simulation Polishing procedure: Grinding up to 4000-grit by silicon carbide papers under running water + ultrasonication |

(a) glossmeter for Gloss Units measurements (b) optical profiler for Ra measurements (c) spectrophotometer for color change (ΔΕ) (d) Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) observation |

Highly filled flowable composite showed:

|

Lai et al., 2018 [58] |

| handling - mechanical properties - wear |

Experimental groups: Six flowable composite resins (1) Beautifil Flow Plus F00 (BF; Shofu Inc., Kyoto, Japan) (2) Clearfil Majesty ES Flow (CE; Kuraray Noritake Dental Inc., Tokyo, Japan) (3) Estelite Universal Flow (EU; Tokuyama Dental Corp, Tokyo, Japan) (4) Filtek Supreme Ultra Flowable Restorative (FS; 3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN, USA) (5) G-ænial Universal Flow (GU) (6) Gracefil Zero Flow (GZ; GC Corp., Tokyo, Japan) Control groups: two conventional resin composites: (7) micro hybrid, Clearfil AP-X (AP; Kuraray Noritake Dental Inc., Tokyo, Japan) (8) nano filled resin composite, Filtek Supreme Ultra (SU; 3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN, USA) Uniform polishing procedure: Grinding up to 1200-grit by silicon carbide paper discs |

(a) thermogravimetry/differential thermal analysis (TG/DTA) for filler content measurement (b) ISO 4049:2019 specifications and three-point bending test for flexural strength, flexural modulus and modulus of resilience evaluation (c) Confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM) for maximum depth and volume loss of wear facets (d) universal testing machine for extrusion force measurement (e) creep meter for thread formation (stickiness) (f) SEM analysis |

Flowable resins show:

Conventional nanofilled resin presents significantly lower volume loss compared to the other materials. Significantly higher thread formation for GU compared to the other resin composites. Increasing the inorganic filler content did not enhance the physical properties of highly filled flowable resin composites. |

Imai et al., 2019 [10] |

| occlusal wear | (1) Filtek Bulk Fill Flowable Restorative (3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN, USA) (2) G-aenial Bulk Injectable (GC Corp., Tokyo, Japan) (3) SDR flow + (Dentsply, York, PA, USA) (4) Tetric EvoFlow Bulk Fill (Ivoclar Vivadent AG, Schaan, Lichtenstein) (5) Clearfil Majesty IC (Kuraray Noritake Dental Inc., Tokyo, Japan) (6) Filtek Supreme Ultra Flow (7) G-aenial Universal Flo (8) Herculite XRV Ultra Flow (Kerr, Orange, CA, USA) Universal polishing procedure: Grinding up to 4000-grit by silicon carbide paper discs Wear simulation by 400,000 cycles in a Leinfelder-Suzuki device with a stainless steel ball bearing antagonist |

Non-contact profilometer and SEM analysis for volume loss and maximum depth of wear evaluation | G-aenial bullk injectable, G-aenial Universal Flo and Filtek Supreme Ultra Flow showed significantly less wear and significantly lower volume loss than the other flowable materials | Ujiie et al., 2020 [59] |

| color stability | (1) two high-viscosity flowable composites (G-aenial Injectable, GC, Tokyo, Japan; Estelite Super Low Flow, Tokuyama Dental, Tokyo, Japan) (2) a bulk-fill flowable composite (Filtek Bulk-Fill Flowable) (3) a low viscosity flowable composite (Filtek Ultimate Flowable, 3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN, USA) (4) a packable composite (Filtek Ultimate, 3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN, USA) Uniform polishing procedure: Sof-Lex polishing discs (3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN, USA) Experimental groups: Immersion in various colorant solutions (coke, tea, coffee, red wine) Control group: Immersion in saline |

(a) spectrophotometer (EasyShade IV, Vita, Germany) (b) colorimeter (ShadeStar, Dentsply Sirona, USA) for color measurements in two time intervals: immediately after discoloration for 144 hours in an incubator at 37°C and after repolishing |

Color stability is material dependent and colorant solution dependent. Filtek Ultimate flowable presented the highest level of color change in both time intervals Color stability of high viscosity flowable composite materials is comparable to that of packable composite. |

Korkut et al., 2020 [60] |

| cuspal deflection - flexural properties |

Five bulk-fill flowable composite resins: (1) Beautifil Bulk Flowable (BF; Shofu, Kyoto, Japan) (2) Bulk Base (BB; Sun Medical, Shiga, Japan) (3) Filtek Fill and Core (FF; 3M ESPE, St Paul, MN, USA) (4) SDR (SD; Dentsply Sirona, York, PA, USA) (5) X-tra base (XB; VOCO GmbH, Cuxhaven, Germany) and six conventional flowable resin composites: (6) Clearfil Majesty ES Flow (CE) (7) Clearfil Majesty LV (CL) (8) Estelite Universal Flow (EU) (9) G-ænial Universal Injectable (GI) (10) Filtek Supreme Ultra Flowable (FS) (11) UniFil LoFlo Plus (UF; GC, Tokyo, Japan). Uniform polishing procedure: Silicon carbide papers of 600 – grit size. |

(a) Simulated cuspal deflection by the use of aluminium block milled for MOD (mesial – occlusal – distal) cavities assessed by 2 different measurement techniques: a. Micrometer b. CLSM (b) three-point bending test on a universal testing machine for flexural strength and modulus evaluation (c) SEM analysis |

Cuspal deflection, flexural strength and modulus are material dependent Higher cuspal deflection of the conventional flowable resin composites compared to bulk fill flowable resin composites Conventional highly filled flowable resin composites present the highest flexural strength and modulus Significant correlation between flexural properties and cuspal deflection of resin composites |

Shimatani et al., 2020 [61] |

| flexural properties - bonding properties - marginal adaptation - polymerization shrinkage |

4 highly filled flowable composites: (1) Beautifil Flow Plus X F03 (BF) (2) Clearfil Majesty ES Flow Low (CM) (3) Estelite Universal Flow Medium Flow (EU) (4) G-ænial Universal Injectable (GU). Traditional flowable composite (5) Unifil LoFlow Plus (UP, GC, Tokyo, Japan) Bulk fill flowable composite (6) Filtek Bulk Fill Flowable (FF) The adhesive system recommended by the manufacturer of each company was used. The materials properties were evaluated in two time intervals: t1: 10 min after curing t2: 24 h after curing |

(a) ISO 4049:2019 (3-point bending test by a universal testing machine) for flexural properties (b) shear bond strength to enamel and dentin by the universal testing machine (c) traveling microscope for marginal adaptation (d) bonded-disk method using a uni-axial linear variable displacement transducer (LVDT) for polymerization shrinkage (e) Aluminum cuspal deflection method for polymerization shrinkage stress |

The new generation flowable composites showed significantly higher:

|

Tsujimoto et al., 2021 [62] |

| surface roughness | 1. G-ænial Universal Injectable 2. Beautifil Injectable X 2. Filtek Z350XT Flowable Restorative 4. Filtek Z350XT Universal Universal finishing – polishing procedure: Abrasive sandpaper discs of 800-, 1200-, 2000-, 2400 grit size + ultrasonic cleansing Experimental groups: cyclic acid challenge with 0.5% citric acid (pH: 2.3) Control group: absence of cyclic acid challenge |

(a) Surface roughness evaluation (Ra parameter) by a contact stylus profilometer (b) Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) analysis |

Statistically significant differences in Ra values after citric acid challenge between all materials tested (conventional composite resin presented the most favorable surface roughness values) After cyclic acid challenge Beautifil Injectable X presented statistically significant higher Ra values when compared to the control. |

Niyomsujarit et al., 2021 [63] |

| surface roughness - microhardness - flexural strength - elastic modulus |

(1) Estelite Bulk Fill Flow, Tokuyama Corp., Tokyo, Japan (2) G-aenial Posterior, GC Europe N.V., Leuven, Belgium (3) G-aenial Universal Injectable Polishing procedure: Grinding up to 1200-grit by silicon carbide paper discs + ultrasonication randomly divided for immersion into: I. coke II. orange juice, III. into artificial saliva (control group) measured: A. before exposure to beverages B. on the first day C. first week D. first month E. first year |

(a) Surface roughness by 3D non-contact profilometer (Contour GT-K 3D Optical Microscope, Bruker, Izmir, Turkey) (Ra values) (b) Microhardness assessment by a Vickers microhardness device (HMV-G 31 Microhardness Tester, Shimadzu Corporation, Japan) (c) Elastic modulus and flexural strength measurements according to ISO 4049 recommendations (d) SEM analysis |

Microhardness values: Microhybrid > bulk fill > injectable composite Elastic modulus: Bulk fill > injectable > microhybrid composite Flexural strength: Injectable > bulk fill > microhybrid composite Surface roughness: Injectable > bulk fill > microhybrid composite Acidic beverages affected the surface roughness, microhardness, flexural strength, and elastic modulus values of all materials tested including the new injectable composite The injectable composite exposed to short- and long-term immersion cycles exhibited flexural strength values above the ISO 4049/2019 standard. |

Degirmenci et al., 2022 [64] |

| depth of cure (DOC) - hardness - surface roughness - filler dimensions |

(1) Filtek Bulk Fill Flowable Restorative (bulk fill flowable), (2) Tetric EvoFlow Bulk Fill (bulk fill flowable) (3) Filtek Supreme XTE Flowable Restorative (nanofilled flowable) (4) G-ænial Flo X (microhybrid flowable composite) (5) G-ænial Universal Injectable (high-strength injectable composite) |

a. ISO 4049 scrape technique for DOC b. 3D laser confocal microscope (LEXT OLS 4100; Olympus) for durface roughness (Ra values) c. Vickers diamond indenter (Vickers microhardness tester, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) for hardness d. SEM images at 3000 and 9000 magnification for filler content |

DOC: Bulk-fill flowables > highly filled flowable > traditional flowables Hardness: Bulk fill flowables = highly filled injectable > traditional flowable resin Surface roughness: Bulk fill flowables > highly filled injectable |

Ludovichetti et al., 2022 [65] |

| filler weight (FW) - fracture toughness (FT) - Vickers hardness (VHN) - sorption/solubility (S/S) - color change (ΔE) |

(1) Aura bulk-fill (AB) (SDI, Bayswater, Victoria, Australia) (bulk fill composite resin) (2) Tetric EvoCeram (TE) (Ivoclar Vivadent) (bulk fill composite resin) (3) G-ænial Universal Flo (GUF) (GC) (highly filled flowable composite resin) (4) GC Kalore (GCK) (GC, Tokyo, Japan) (conventional composite resin) Stored: I. dry II. wet in distilled water subcategorized in three groups: A. Stored for one day B. Stored for 7 days C. Stored for 60 days |

a. standard ash method for filler weight b. 4-point test jig using a universal testing machine for fracture toughness c. Digital hardness tester for microhardness d. ISO 4049 for sorption/solubility e. Standard Commission Internationale de L’Eclairage (CIE Lab) for color stability |

Highly filled flowable resin composite had:

After 60 days, the color changes of all resin composites used in this study were clinically invisible. |

Jafarpour et al., 2022 [66] |

| polymerization shrinkage | (1) G-aenial Universal Flo (GUF) (2) Filtek Z250, 3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN, USA (3) G-aenial bulk injectable (GBI) (4) X-tra base (XB) (5) X-tra fil (XF), VOCO, Cuxhaven, Germany Polymerization shrinkage evaluation in 4 time intervals t1:1 sec t2:30 sec t3: 60sec t4:1800s |

Relative linear shrinkage assessment and shrinkage strain rate evaluation by numerical differentiation of the shrinkage strain data with respect to time | Polymerization shrinkage values: G-aenial Bulk Injectable = G-aenial Universal Flo > XF = Z250 =XB |

Khoramian Tusi et al., 2022 [67] |

| wear resistance |

Experimental groups: (1) nanohybrid conventional (G-aenial Posterior) and flowable (G-aenial Universal Injectable) composite resins, (2) a nanofilled bulk (Filtek One Bulk-fill Restorative) and flowable (Filtek Ultimate Flow) composite resin (3) submicron-filled conventional (Estelite Posterior Quick, Tokuyama, Tokyo, Japan) and flowable (Estelite Bulk-Fill Flow, Tokuyama, Tokyo, Japan) composite resin Control group: buccal surfaces of extracted human premolars thermomechanical chewing simulation for 240,000 cycles |

volume loss and maximum depth of loss calculation by laser scanner device | wear volume loss and loss depth:

|

Turk et al., 2023 [68] |

| color stability | (1) Filtek Universal Restorative (3M ESPE) (2) SDR flow+ (Dentsply) (3) everX Flow (GC, Tokyo, Japan) (4) G-ænial A’CHORD (GC, Tokyo, Japan) (5) G-ænial Universal Flo (GC) (6) G-ænial Universal Injectable (GC) Polishing procedure: a. By machine (1000-grit, 2000-grit and 4000-grit abrasive paper discs) b. Or by hand (3 M Sof-Lex Diamond Polishing System, 3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN, US) Immersed in five different beverages: a. Distilled water (control group) b. Coffee c. Red wine d. Energy drink e. Coke color change measurement in three time periods: i. Baseline ii. 84 days after immersion iii. After repolishing |

Color stability assessment by the use of a spectrophotometer (ΔE) | The flowable composites (traditional and highly filled) showed similar ΔΕ values to the conventional composite materials in the hand polished groups. SDR flow+ in coffee and wine presented the highest ∆E when compared to other tested materials (above the threshold of clinically acceptable color change) repolishing serves as an effective technique for eliminating surface discoloration in composite restorations |

Uctasli et al., 2023 [69] |

| microhardness - surface roughness - wear |

1mm thin, conservative occlusal veneers fabricated by: (1) Cerasmart blocks, Cerasmart, GC, Tokyo, Japan (CS) (indirect CAD/CAM technique) (2) Beautifil Injectable X (BF) (3) G-ænial Universal Injectable (GU) (4) SonicFill 2, Kerr, Orange, CA, USA (SF) |

(a) three-dimensional scanning i. before ii. after thermomechanical cyclic loading for wear assessment (b) optical profilometer for surface roughness (Ra value) (c) microhardness tester for VHN (d) SEM analysis |

VHN: CS> GU =SF > BF surface roughness: SF > BF > CS > GU volumetric wear: SF > BF > CS > GU GU injectable occlusal veneers are less influenced by thermomechanical cyclic loading than CS milled veneers BF and SF: significant volumetric loss and increased Ra values which might limit their clinical use as thin occlusal veneers |

Elsahn et al., 2023 [70] |

| physical stability - optical stability |

(1) Beautifil Injectable X (injectable flowable resin based material) (2) Beautifil II LS (low shrinkage paste resin based material), Shofu, Kyoto, Japan (3) CharmFil flow (flowable composite resin), Dentkist Inc, Gunpo-si, Gyeonggi-do, Korea (4) CharmFil Plus (nanofilled composite resin), Dentkist Inc, Gunpo-si, Gyeonggi-do, Korea No information available concerning the polishing procedure Aging after thermocycling and staining challenge |

(a) micro-hardness tester (Wilson Tukon 1102, Buehler, Echterdingen, Germany) for Vickers hardness (VH) (b) water sorption and solubility (WS/SL) tests (c) digital spectrophotometer for color change assessment |

Hardness values: packable – conventional resin > highly filled injectable flowable material > traditional flowables Beautifil Injectable X and II LS showed negative WS, whereas the other groups had positive values All groups showed significant color alterations after one week of the staining challenge |

Islam et al., 2023 [71] |

| surface roughness - surface gloss |

G-aenial Bulk Injectable flowable resin composite, GC 2 different polishing procedures: I. The two-step Sof-Lex spiral wheels system (Solventum) II. The multiple-step Sof-Le XT disks (Solventum) 2 different time intervals: A. After polishing B. After three months immersed in 2 different liquids: a. artificial saliva (control group) b. Coca-Cola. |

(a) optical profilometer for surface roughness (Ra measurment) (b) Horiba gloss checker |

Improved surface roughness and gloss by using the multiple-step polishing system Acidic media had a negative impact on surface roughness and surface gloss of the resin composite material |

Elgammal et al., 2023 [72] |

| surface roughness - microbial adhesion and viability of Streptococcus mutans |

(1) Filtek Supreme Flowable Restorative (2) Tetric EvoFlow (3) G-aenial Universal Flo (4) G-aenial Universal Injectable Four different polishing procedures: 1. Sof-Lex discs, 3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN, USA (SLD) 2. Sof-Lex Spirals, 3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN, USA (SLS) 3. One Gloss, Shofu, Tokyo, Japan (OG) 4. PoGo, Dentsply/Caulk, Milford, DE, USA (PG) |

(a) optical profiler(Ra and Rz) for surface roughness (b) Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (c) colony forming unit (CFU) and cell viability assay for biofilm analysis |

Both material and polishing procedures affect surface roughness and microbial adhesion GUI adhered the lowest amount of Strep.mutans, due to the smoothest surfaces. The smoothest surfaces possess GUI and GUF, among materials and SLD and SLS, among polishing procedures |

Vulovic et al., 2023 [73] |

| optical properties - surface roughness |

(1) Microhybrid conventional composite resin (G-ænial Anterior, GC, Tokyo, Japan) (2) Highly filled flowable composite resin (G-ænial Universal Flo) (3) Highly filled injectable flowable composite resin (G-ænial Universal Injectable) Polishing procedure: specimens grinded for 180s manual grinding up to 1200-grit by silicon carbide papers Experimental groups: 1. Multi step rubber polishing discs (Sof-Lex polishing discs) 2. Two step flexible polishing discs (CLEARFIL Twist DIA, EVE Ernst Vetter, Keltern, Germany Control group: no further commercial polishing |

(a) spectrophotometer for optical properties analysis (L*a*b) translucency assessment: TP and TP00 equations opalescence evaluation: OP-BW equation chroma evaluation: C*ab formula (b) refractive index assessment (RI) by the use of Abbe refractometer (c) optical profilometer for surface roughness (d) SEM analysis (e) Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) analysis |

Highly filled flowable injectable composite had the highest translucency and opalescence and the lowest chroma value the polishing procedure did not significantly affect the RI the composite type and polishing procedure show statistical significant effects on surface roughness |

Degirmenci et al., 2023 [74] |

| polymerization shrinkage | (1) EverX Posterior (GC, Tokyo, Japan) (2) EverX Flow Bulk (GC, Tokyo, Japan) (3) EverX Flow Dentin (GC, Tokyo, Japan) (4) G-aenial Anterior (5) G-aenial Posterior (6) G-aenial A’chord (GC, Tokyo, Japan) (7) G-aenial Universal Injectable (8) Filtek One Bulk Fill (9) Filtek Universal Restorative (10) SDR + Flow (11) Aura Bulk Fill (SDI, Bayswater, Victoria, Australia) |

(a) Polymerization shrinkage assessment by i. Buoyancy method ii. Linear strain gauge method iii. Depth measurements (b) filler content (wt. %) by ashing-in-air technique (c) flexural modulus by 3 point bending test following the ISO 4049:2019 specifications (d) degree of conversion (DOC) by Fourier Transformed Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) |

Shrinkage values, obtained by the buoyancy method, are greater than those of the strain gauge The highest volume shrinkage and linear shrinkage values were observed for the highly filled flowable composite resin Volumetric filler amount correlates with shrinkage values The lowest DOC is present in the highly filled flowable composite resin composite (G-aenial Universal Injectable) There are some differences (around 10 %) between the filler content (wt. %) measured by the ashing-in-air method and the data given by the manufacturers. |

Szczesio-Wlodarczyk et al., 2024 [75] |

| mechanical properties - wear - antibacterial properties - biocompatibility |

Three highly filled flowable composite resins: (1) G-aenial Universal Injectable, (GU) (2) Beautifil Injectable XSL (BI), (3) Filtek Supreme Flowable (FS) and a compomer: (4) Dyract Flow, Dentsply, York, PA, USA (DF) Uniform polishing procedure: silicon carbide abrasive papers (600-, 1000-, 2000- grit size) time intervals of investigation: a. immediately after preparation b. after 1-day c. 7-day d. 14-day e. 30-day water storage |

(a) three-point bending test in accordance with ISO 4049:2019 for flexural strength, modulus and elastic recovery (b) Three body wear test for volume loss and wear depth assessment (c) an optical interferometer (Ra values) for surface roughness (d) SEM analysis (e) CCK-8 test for cell viability (f) Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM) and SEM for cell morphology (g) CFU counting, CLSM, and SEM for S.mutans adherence |

Mechanical properties are material-dependent and sensitive to water storage CFU counting: no significant differences between the materials GU and FS had more favorable cell adhesion and morphology Flexural strength: GU > FS > BI > DF at all testing levels FS presented a slightly thicker biofilm and BI showed lower bacteria density Superior properties of highly filled injectable composite resins |

Chen et al., 2024 [76] |

| chemical stability - optical stability |

Highly filled flowable resin composites + compomer (1) G-aenial Universal Injectable (GU) (2) Beautifil Injectable XSL (BI), (3) Filtek Supreme Flowable (FS) (4) Dyract Flow (DF) Uniform polishing procedure: silicon carbide abrasive papers (up to 2000- grit) |

(a) ISO4049:2019 standard for water sorption/solubility (b) inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES) and F-ion selective electrode for elemental release (c) FTIR for degree of convertion immediately after curing and 24 hours later (d) Contact angle measurement by sessile drop method for wettability (e) color difference (ΔE), lightness difference (ΔL) and translucency (TP) by a spectrophotometer and the CIEL*a*b* values |

G-aenial Universal Injectable exhibits:

Both material type and duration of water storage affected the optical properties |

Bai et al., 2024 [77] |

| surface gloss - surface roughness - color change |

1. Estelite Universal Flow (EUF) 2. Beautifil Flow Plus F00 (BFP) 3. GC Fuji II, GC, Tokyo, Japan (FLC) 4. GC Fuji IX GP EXTRA, GC, Tokyo, Japan (FGP) Divided into four groups of prophylaxis procedures: Group 1: Load of 100 gf, 10 s, 4× Group 2: Load of 100 gf, 30 s, 4× Group 3: Load of 300 gf, 10 s, 4× Group 4: Load of 300 gf, 30 s, 4× |

(a) glossmeter (GD-26, Murakami Color Research Laboratory, Tokyo, Japan) for surface gloss (b) surface profilometer (Surfcom 130A, Tokyo Seimitsu, Tokyo, Japan) (Ra, Rz, Ry values) (c) Spectrophotometer(Vita Easyshade V, Vita Zahnfabrik, Bad Sackingen, Germany) for color change (d) 3D Measuring Laser Microscope for surface observation (e) SEM observations |

Highly filled flowable resins presented favorable surface characteristics compared to glass ionomer cements The higher loadings and longer durations of dental prophylaxis might affect surface characteristics, depending on the material |

Miyashita-Kobayashi et al., 2024 [78] |

| physical and mechanical properties |

Experimental groups: Four types of highly filled flowable composites: (1) G-aenial Universal Flo (2) G-aenial Universal Injectable (3) Beautifl Injectable (4) Beautifl Flow Plus Control group: nanohybrid conventional resin composite (5) Filtek Z350 XT, 3M ESPE |

a. universal testing machine for flexural strength and elastic modulus b. optical profilometer (Ra parameter) for surface roughness c. microhardness tester (HMG-G; Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) for VHN d. Microleakage evaluation in class V cavities by the use of methylene blue solution |

Variations in highly filled flowable resins concerning physical and mechanical properties. Flexural strength: no statistically significant difference between all highly filled flowables and the control elastic modulus: Filtek Z350 presented higher elastic modulus compared to experimental groups VHN: Control group > experimental groups surface roughness: no differences observed between groups microleakage: control group > highly filled flowables |

Basheer et al., 2024 [79] |

| polymerization shrinkage stress | Conventional composite resins + highly filled flowable resin + bulk fill composite resin + flowable bulk-fill composite resins: (1) EverX Posterior (2) EverX Flow Bulk (3) G-aenial Anterior (4) G-aenial Posterior (5) G-aenial A’chord (6) G-aenial Universal Injectable (7) Filtek One Bulk Fill (8) Filtek Universal Restorative (9) SDR + Flow (10) Aura Bulk Fill |

Polymerization shrinkage stress evaluation by the use of two different methods a. Contraction forces measurement b. Photoelastic analysis |

Shrinkage stress values: photoelastic method > contraction forces measurements No differences in polymerization shrinkage stress values between conventional composite resins and the highly filled flowable resin composite. |

Szczesio – Wlodararczyk et al., 2024 [80] |

| wear - flexural strength |

1. G-aenial Universal Injectable 2. Beautifil Plus F00 3. Tetric EvoFlow and a conventional composite resin: 4. Empress Direct (Ivoclar Vivadent AG, Schaan, Lichtenstein) wear simulation by 200,000 cycles |

(a) Two-body wear test (b) Three-point bending test for flexural strength, flexural modulus and modulus of resilience (c) SEM observations |

G-aenial Universal Injectable and Beautifil Plus F00 presented:

Injectable, highly filled flowable composite resins may be suitable to use in occlusal, load-bearing areas |

Rajabi et al., 2024 [81] |

| Fluorescence adjustment level - Color adjustment level |

Class V cavities of 50 extracted human teeth restored by: Five paste-type resin composites: (1) Omnichroma (Tokuyama Dental Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) (2) G-aenial A-Chord (3) Estelite Asteria (Tokuyama Dental Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) (4) Clearfil Majesty ES-2 (Kuraray Noritake, Tokyo, Japan) (5) Charisma Diamond One (Kulzer Dental, Hanau, Germany) and five highly-filled flowable composites: (6) Omnichroma flow (Tokuyama Dental Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) (7) G-aenial Injectable (GC, Japan) (8) Estelite Universal Flow (Tokuyama Dental Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) (9) Clearfil Majesty Low Flow (Kuraray Noritake, Tokyo, Japan) (10) Charisma Diamond One Flow (Kulzer Dental, Hanau, Germany) Polishing procedure: two-step diamond spiral wheels |

color adjustment (ΔECP) and fuorescence adjustment (ΔEFI) levels evaluated by the use of (a) Cross-polarization (CP) (b) fuorescence illumination (FI) images |

Paste-type composites presented significantly lower ΔEFI and ΔECP values than the highly filled flowable composites The only clinically acceptable color adjustment was found for G-aenial Universal Injectable among the flowable composites. |

Bayraktar et al., 2024 [82] |

| Fracture resistance | 50 extracted maxillary premolars Control group: 10 intact, untreated premolars Experimental groups (40 extracted teeth) 1. small class II cavities restored with highly filled flowable resin (G-aenial Injectable) 2. extensive class II cavities restored with highly filled flowable resin 3. small class II cavities restored with packable resin (G-aenial Posterior) 4. extensive class II cavities restored with highly filled flowable resin |

(a) universal testing machine (model 3343, Instron Corporation, Canton, MA, USA) with stainless steel ball of 4mm diameter (b) Steromicroscope for mode of failyre assessment |

no statistically significant differences between:

|

Gerges et al., 2024 [83] |

| surface roughness - wear |

Two highly filled flowable composites: (1) Clearfl Majesty ES flow (2) G-aenial Universal Injectable two conventional resin composites (3) Clearfl Majesty ES-2 (4) G-aenial A’CHORD Polishing procedure: Up to 4000- grit size silicon carbide paper for 20 seconds |

(a) Wear assessment after chewing simulations (240.000 cycles, 20N) (b) surface roughness by a rugosimeter, before after chewing cycles (c) SEM observations |

Surface roughness and wear of highly filled flowable composites were comparable to that of conventional composites Highly filled flowables can be used in occlusal areas especially when overcured |

Checchi et al., 2024 [84] |

| flexural properties - wear resistance |

nine highly filled flowable resin composites viscous composites conventional low-filled flowable composites |

(a) Two-body wear test (b) Three-point bending test (c) SEM analysis |

The majority of highly filled composites exhibited:

|

Francois et al., 2024 [85] |

| surface roughness - surface hardnes |

4 highly filled flowable composite resins: (1) G-aenial Universal Flo (2) G-aenial Universal Injectable (3) Tetric EvoFlow (4) Filtek Supreme Flowable Restorative At different time intervals (a) t0: before immersion (b) t1: 9h after immersion (c) t2: 18h after immersion in different media i. gastric juice ii. fizzy drink iii. citric juice iv. artificial saliva |

(a) optical profiler (Ra measurement) (b) SEM analysis (c) Vickers hardness tester for surface hardness |

G-aenial Universal Injectable revealed lower surface roughness and higher hardness compared to other highly filled flowable composite resins both before and after exposure to acidic media | Vulovic et al., 2024 [86] |

| Objective | Materials | Sample Size/Time Intervals | Evaluation Criteria | Results | Author/Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evaluation of direct posterior restorations after 36 months. | 1. Conventional composite resin (Estelite Sigma Quick, Tokuyama, Tokyo, Japan) 2. Highly filled flowable composite resin (G-aenial Universal Flo, GC) two-step self-etch adhesive applied to both materials |

58 mid-size to extensive posterior composite restorations in 32 patients Restoration evaluation: a. After placement (baseline) b. 6-months c. 12-months d. 24-months e. 36-months After 36 months 42 restorations were evaluated in 21 patients |

FDI (World Dental Federation) criteria | No statistically significant difference between cavities restored with highly filled flowable and conventional composite resins (p > 0.05/ Pearson’s X2 and Fisher’s exact tests for differences between restorative materials and Cochran’s Q test for differences between the same material in different time intervals) No secondary caries observed. |

Kitasako et al., 2016 [87] |

| Evaluation of direct non-carious cervical lesions (NCCLs) after 3 years | 1. Highly filled flowable composite (Clearfil Majesty ES Flow, Kuraray Noritake Dental Inc., Tokyo, Japan) 2. Conventional paste-type composite (Clearfil Majesty ES-2, Kuraray Noritake Dental Inc., Tokyo, Japan) Clearfil SE Bond (Kuraray Noritake Dental Inc., Tokyo, Japan) |

84 NCCLs in 27 subjects were included Restoration evaluation: a. baseline (BL) b. 1 year c. 2 years d. and 3 years |

FDI criteria | Regarding changes over time, significant differences were found within each group (p < 0.01) No significant difference between the two material groups at any time interval concerning functional properties The highly filled flowable resin composite presented significantly better: surface lustre (p<0.01) at the 1 year recall and marginal staining (p<0.05) at any time point (Wilcoxon signed-rank test) |

Zhang et al., 2021 [88] |

| Evaluation of direct posterior restorations after 18 months | 1. Bioactive injectable resin composite (Beautifil Flow Plus X F00, Shofu Inc., Kyoto, Japan) 2. Nanohybrid resin composite (Tetric N-Ceram, Ivoclar Vivadent AG, Schaan, Lichtenstein) |

18 patients with 26 class I and II carious cavities Restoration evaluation: a. baseline b. 6-months c. 12-months d. 18-months |

modified United States Public Health Service (USPHS) criteria |

no statistically significant difference between the two materials at different time intervals in terms of anatomical form, secondary caries, marginal staining, postoperative sensitivity (p=1.00) and marginal adaptation (p>0.05 / 95% confidence level/ 80% power / Chi-square test and Cochran’s Q test) |

Elderiny et al., 2024 [89] |

| Evaluation of class II restoration using different restorative materials after 2 years | 1. Conventional composite: Clearfil Majesty Posterior ( Kuraray Noritake Dental Inc., Tokyo, Japan) 2. Bulk-fill composite:Filtek One Bulk Fill Restorative (Solventum) 3. Highly filled flowable composite: G-aenial Universal Injectable (GC, Japan) |

110 patients with 259 Class II restorations Restoration evaluation: a. Baseline b. 1-year c. 2 years After 2 years: i. 59 conventional composite restorations ii. 68 bulk-fill composite restorations iii. 61 highly filled flowable composite restorations in 74 patients have been evaluated |

FDI criteria | The materials showed similar results in most of the scores. Highly filled flowable composite and bulk-fill composite presented better clinical performance regarding surface gloss compared to conventional composite (p<0.05, rank-based Friedman analysis) |

Hançer Sarıca et al., 2025 [90] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).