1. Introduction

Early Childhood Caries (ECC) is a significant form of tooth decay in children, typically affecting those under the age of six. ECC is particularly aggressive compared to caries in older children and adults, as it causes rapid destruction of tooth structures. The primary teeth most affected are the upper incisors and first molars, making early detection and intervention crucial to preventing further damage [

1].

As outlined by the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD), ECC is characterized by the presence of decayed, missing, or filled surfaces in any primary tooth of a child younger than 71 months [

2]. Initially, ECC manifests as white spot lesions on the gingival margins of the upper incisors, which can escalate to deeper cavities and tooth loss if left untreated. Despite a global decline in overall caries prevalence, ECC continues to be a prominent public health issue, with increasing rates in several regions. This rise presents significant challenges to both preventive and therapeutic dental strategies [

3,

4].

Various remineralizing agents have been developed to address the early stages of caries. Casein Phosphopeptide-Amorphous Calcium Phosphate (CPP-ACP) has emerged as an effective agent due to its ability to release bioavailable calcium and phosphate ions, essential for enamel remineralization and the prevention of further demineralization [

5]. CPP-ACP works by stabilizing these ions within the dental plaque, reducing mineral loss during caries episodes and aiding in enamel repair [

6,

7].

Additionally, Glass Ionomer Cement (GIC) is commonly used in restorative dentistry for its ability to bond chemically with tooth surfaces and release fluoride, known for its antimicrobial effects. GIC is particularly beneficial in caries management due to its fluoride-releasing properties and minimal solubility in the oral environment. The acidic pH during its setting and its fluoride content further enhances its antibacterial properties, potentially reducing the levels of Streptococcus mutans, a key bacterium involved in the development and progression of ECC [

8,

9].

S. mutans begins colonizing the oral cavity soon after the eruption of the first tooth, playing a pivotal role in the initiation and progression of caries. This bacterium metabolizes fermentable carbohydrates to produce lactic acid, which lowers the pH of the oral cavity, promoting the demineralization of tooth enamel. Controlling S. mutans is essential for halting the progression of ECC, as it contributes significantly to the formation of cavitated lesions [

10,

11].

The objective of this study is to compare the antimicrobial effectiveness of CPP-ACP and GIC in reducing the levels of S. mutans in the saliva of children diagnosed with ECC. By assessing the impact of these treatments, this research aims to provide valuable insights into their influence on the oral microbiota and inform more effective strategies for the prevention and management of ECC.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was conducted on preschool children aged 3 to 5 years who visited the outpatient department (OPD) of the Department of Pediatric and Preventive Dentistry, BBD College of Dental Sciences, Lucknow. Children diagnosed with Early Childhood Caries (ECC) were selected based on stringent inclusion and exclusion criteria to ensure the reliability and precision of the results. The study followed the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was obtained from the institutional ethical committee of BBD College of Dental Sciences, Lucknow (Approval No. 19). Written informed consent was collected from the parents or guardians of all participants. They were thoroughly briefed in Hindi or Bhojpuri on the study's aims, methods, potential risks, and benefits. The confidentiality of participant information was ensured through anonymization and secure storage of all personal data. Participants were assured they could withdraw from the study at any stage without consequences.

2.1. Inclusion Criteria

Age Range (3 to 5 years): The study was focused on preschool-aged children, a critical period for the development of ECC, where early interventions are essential.

Children with clinically visible dental caries in their primary teeth were included, ensuring the sample was homogeneous in relation to the study's focus.

Children residing within a 5-8 km radius of the campus were included to ensure ease of follow-up and sample collection.

2.2. Exclusion Criteria

Children with any history of systemic diseases or who had taken antibiotics within the past three months were excluded to avoid potential confounding effects on the microbial profile.

Children with developmental or cognitive disabilities were excluded to avoid potential bias in treatment adherence or the ability to follow oral hygiene protocols.

Children who had undergone major dental treatments or orthodontic procedures were excluded to prevent alterations in the microbial environment that might influence the study's outcomes.

Participation was voluntary, and only children whose parents or legal guardians provided informed consent were enrolled in the study.

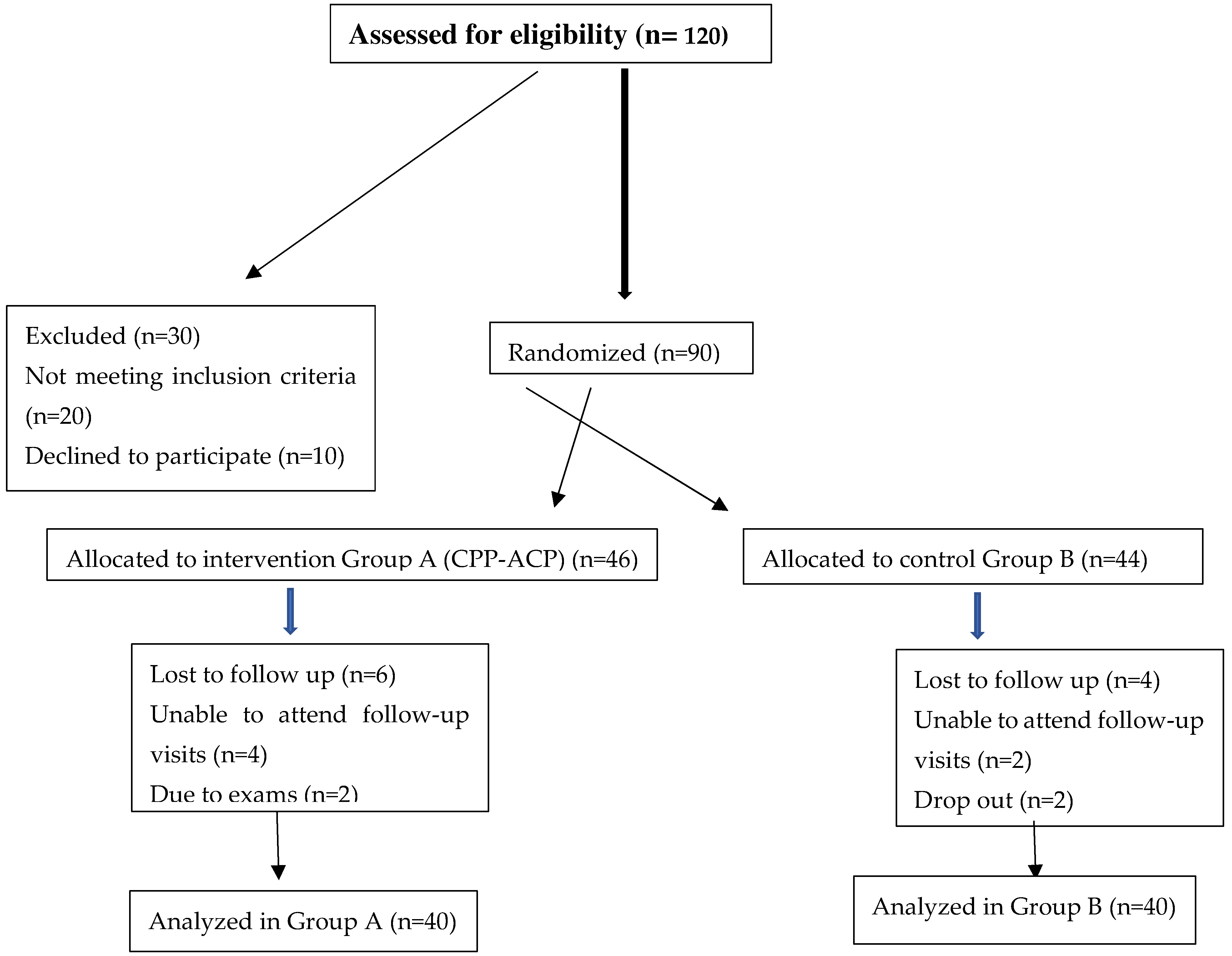

Study Design: This research employed a randomized controlled trial (RCT) design, regarded as the gold standard for evaluating clinical interventions. Randomization was utilized to reduce selection bias and enhance the validity of the findings. (

Figure 1).

Sample Size Calculation: Sample size calculation was based on a power analysis to detect significant differences in the primary outcome, which was the salivary Streptococcus mutans (S. mutans) colony-forming unit (CFU) count. Using an alpha of 0.05, 80% power, and an effect size estimated from previous studies, a total of 80 participants (40 per group) were deemed necessary to achieve statistically significant results. The effect size was derived from prior research indicating the average reduction in S. mutans CFU with similar interventions. (

Figure 1).

Group Allocation and Randomization: Participants were randomly assigned to one of two groups using a computer-generated randomization method to minimize allocation bias. The allocation was concealed from both the participants and the clinicians involved in the study using sealed opaque envelopes to ensure a single-blind design. (

Figure 1).

Group A (CPP-ACP Group): Participants in this group received Glass Ionomer Cement (GIC) restorations and were instructed to apply a pea-sized amount of CPP-ACP cream to all tooth surfaces after dinner, just before sleep.

Group B (Control Group): Children in this group received only GIC restorations, without any CPP-ACP application.

The randomization process ensured that the groups were balanced, minimizing bias in treatment allocation.

Baseline Data Collection: Prior to the intervention, all participants underwent a comprehensive clinical examination, including the assessment of their oral health status. Stimulated saliva samples were collected from all children to measure the baseline levels of S. mutans CFUs. The samples were collected by having the children chew on a paraffin wax tablet for a standardized period (2–3 minutes), which stimulated saliva production. These samples were then processed and the CFU counts were determined using Mitis Salivarius Agar (MSA) as the culture medium.

Treatment Protocol: Restorative treatment was carried out on all participants with decayed teeth, using GIC following the manufacturer's instructions (Fuji IX). The restoration procedure included cleaning the cavity, placing the GIC, and allowing it to set for the specified time (5 minutes). After restoration, participants were instructed to follow the relevant treatment protocol depending on their group assignment:

Group A (CPP-ACP): Application of CPP-ACP cream (GC Tooth Mousse) was recommended post-restoration as part of the intervention.

Group B (Control): Only the restorative procedure with GIC was performed.

Post-Treatment Data Collection: One week, one month, and three months following the restorative procedure, stimulated saliva samples were recollected from all participants to measure changes in the S. mutans CFU count. These time points were selected to capture both the short-term and long-term effects of the interventions on microbial load, based on prior evidence suggesting these intervals to be optimal for detecting significant microbial changes.

Dropout and Loss to Follow-up: Efforts were made to reduce participant dropout by emphasizing the importance of follow-up visits. However, any participant who withdrew from the study or did not complete the follow-up visits was excluded from the final analysis. A final analysis was conducted with data from those who completed all study visits and protocols. (

Figure 1)

Instruments and Materials Required: The following instruments and materials were used in the study:

Infection control: Head cap, face mask, gloves

Clinical examination and treatment: Probes, explorers, mouth mirrors, tweezers, cotton rolls

Restorative treatment: GIC mixing pad, plastic spatula, GIC Fuji IX for restoration

Sample collection: Paraffin wax, plastic containers, cotton rolls

Caries excavation: Airotor, excavator

CPP-ACP group treatment: GC Tooth Mousse

Miscellaneous: Suction tube, green cloth, kidney tray for maintaining a clean working environment

Culture Medium: For the isolation of S. mutans, Mitis Salivarius Agar (MSA) was used. The agar was prepared as per standard protocols and inoculated with the saliva samples. These samples were incubated at 37°C for 48 hours to allow the growth of S. mutans colonies. Colony counting was performed manually, and CFU counts were determined in duplicate for accuracy.

Data Handling and Statistical Analysis Data: were recorded in Microsoft Excel and analyzed using SPSS (version 22) software. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the baseline characteristics. To test for normality, the Shapiro-Wilk test was performed. Paired t-tests were performed for within-group comparisons, and independent t-tests were used for between-group comparisons of the changes in S. mutans CFU counts. Potential confounders such as age, gender, and dietary habits were analyzed to determine their effect on the outcomes. A significance level of p<0.05 was used for all statistical tests.

3. Results

To assess the relationship between snack frequency in the case and control groups, a Chi-square test was used. The distribution of snack frequency was comparable between the two groups, with no significant differences observed (control: 90% ≤2 snacks vs. case: 80%). These findings suggest that the dietary habits of the two groups were similar at baseline. (

Table 1).

Independent sample t-test was used to compare mean CFU counts at baseline and after treatment. Baseline CFU counts showed no significant difference (P = 0.7344), confirming comparable groups. Post-treatment, the case group had significantly lower CFU counts (P = 0.0002***), demonstrating the effectiveness of CPP-ACP with GIC restorations in reducing Streptococcus mutans levels. (

Table 2).

Independent sample t-test assessed gender-based baseline differences in CFU counts. No significant differences were observed between males or females in control and case groups (P > 0.05), confirming gender-based baseline comparability. (

Table 3).

An independent t-test was used to compare post-treatment CFU counts between genders at 1 week, 1 month, and 3 months. At each time point, CFU counts were significantly lower in the case group for both males and females (P < 0.05). These results highlight the sustained effectiveness of CPP-ACP application with GIC restorations in reducing Streptococcus mutans, regardless of gender. (

Table 4).

4. Discussion

Early Childhood Caries (ECC) is a significant public health concern, particularly among infants and preschool-aged children. Streptococcus mutans is widely regarded as a primary etiological factor in ECC due to its ability to adhere to tooth surfaces and form biofilms, which are resistant to normal oral cleansing [

11]. S. mutans is highly cariogenic because it ferments dietary sugars, producing organic acids that lower plaque pH, leading to enamel demineralization. Its role in the initiation and progression of caries has been extensively studied, and it is considered the dominant bacterium responsible for the early stages of dental caries in children [

12,

13]. While other bacteria, such as Lactobacillus species, contribute to caries progression, S. mutans is particularly virulent due to its capacity to produce extracellular polysaccharides and acid byproducts, which create an environment conducive to further bacterial growth and tooth decay [

14,

15]. Consequently, targeting S. mutans is crucial in the prevention and management of ECC.

The observed reductions in Streptococcus mutans levels in the case group underscore the multifaceted role of CPP-ACP in caries management. CPP-ACP has been shown to buffer plaque acidity and stabilize calcium and phosphate ions, thus preventing enamel demineralization and promoting remineralization. CPP-ACP stabilizes these ions in a bioavailable form, which can be redeposited onto the enamel, reversing the early stages of caries [

16,

17]. Research has demonstrated that CPP-ACP can significantly increase the concentration of calcium and phosphate in the plaque fluid, making it a potent remineralizing agent [

17]. Additionally, studies have shown that CPP-ACP application can reduce plaque acidity, providing an optimal environment for remineralization [

17,

18]. When combined with the fluoride-releasing properties of glass ionomer cement (GIC), a synergistic effect occurs, enhancing the overall reduction in bacterial levels and reinforcing the remineralization process compared to the control group [

19].

Snack frequency and dietary habits were assessed using a self-reported food frequency questionnaire, which recorded participants' typical consumption of sugary snacks over the previous week. This ensured consistency between the groups and minimized confounding effects from dietary variations. Previous research highlights the strong association between frequent sugary snack consumption and the progression of ECC, reinforcing the need for dietary control in caries management [

17,

20,

21].

The control group also showed significant reductions in Streptococcus mutans levels post-treatment. This reduction can be attributed to the inherent antibacterial properties of GIC, which releases fluoride to enhance remineralization and inhibit bacterial growth. [

17] Furthermore, the oral health education provided during the study likely improved participants’ oral hygiene practices, contributing to the observed reductions in bacterial loads. The role of oral health education in promoting behavioral changes, such as reducing the consumption of cariogenic foods and improving oral hygiene, should be carefully considered when interpreting these findings [

17,

22].

Baseline CFU levels between the case and control groups were statistically comparable, establishing a solid foundation for post-treatment comparisons. Post-treatment data revealed significantly greater reductions in CFU levels in the case group across all follow-up periods. For example, at the 1-week follow-up, CFU levels in the case group were markedly lower than those in the control group, and this trend persisted at the 1-month and 3-month intervals [

16,

17,

23,

24]. Gender-based analyses confirmed the consistent efficacy of CPP-ACP, with similar trends in CFU reductions observed for both males and females, demonstrating the intervention’s broad applicability [

17].

The rationale for selecting 1-week, 1-month, and 3-month follow-up intervals was informed by the biological progression of ECC and the temporal effects of CPP-ACP. Immediate bacterial reductions observed at 1 week are consistent with previous findings, which reported significant short-term impacts of CPP-ACP [

25,

26]. The 1-month and 3-month follow-ups allowed for the evaluation of sustained effects, consistent with the literature on biofilm recolonization and remineralization dynamics. This comprehensive approach provides a nuanced understanding of immediate and long-term treatment outcomes.[

26]

Future research should mitigate these limitations by employing larger, randomized sample sizes to minimize selection bias and enhance the validity of findings. Moreover, the limited follow-up duration constrains the evaluation of the long-term sustainability of the observed effects. Extending follow-up periods in future studies will enable a more comprehensive assessment of the durability of CPP-ACP’s benefits. Additionally, as oral health education may have influenced participants’ behavior, future research should seek to disentangle its effects from those of the treatment, facilitating a more precise evaluation of CPP-ACP’s independent impact on early childhood caries.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the potential of CPP-ACP as an adjunctive agent in managing ECC by significantly reducing Streptococcus mutans levels. The combination of CPP-ACP with GIC restorations provides a synergistic approach to caries prevention and management. In practical terms, implementing CPP-ACP treatment in routine pediatric dental care, especially in high-risk populations, could significantly improve ECC outcomes. In low-income settings, where the prevalence of ECC is disproportionately high, the integration of CPP-ACP into affordable preventive protocols could have transformative effects on public health. Future research should explore the cost-effectiveness of these interventions and the feasibility of implementing them in resource-limited environments, emphasizing the need for accessible and sustainable oral health care solutions for vulnerable populations.

Funding

No funding was provided for the publication.

Informed Consent Statement

The informed consent was taken from the study participants.

Data Availability Statement

The data for the present study will be available upon reasonable request from corresponding author or first author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Çolak, H.; Dülgergil, C.T.; Dalli, M.; Hamidi, M.M. Early childhood caries update: A review of causes, diagnoses, and treatments. J. Nat. Sci. Biol. Med. 2013, 4, 29–38. [CrossRef]

- American Academy on Pediatric Dentistry; American Academy of Pediatrics. Policy on early childhood caries (ECC): classifications, consequences, and preventive strategies. Pediatr Dent. 2008;30(7 Suppl):40-43.

- Alazmah, A. Early Childhood Caries: A Review. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2017, 18, 732–737. [CrossRef]

- Anil, S.; Anand, P.S. Early Childhood Caries: Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Prevention. Front. Pediatr. 2017, 5, 157–157. [CrossRef]

- Cochrane, N.; Cai, F.; Huq, N.L.; Burrow, M.; Reynolds, E. New Approaches to Enhanced Remineralization of Tooth Enamel. J. Dent. Res. 2010, 89, 1187–1197. [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, E. Casein Phosphopeptide-Amorphous Calcium Phosphate: The Scientific Evidence. Adv. Dent. Res. 2009, 21, 25–29. [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, E.; Cai, F.; Shen, P.; Walker, G. Retention in Plaque and Remineralization of Enamel Lesions by Various Forms of Calcium in a Mouthrinse or Sugar-free Chewing Gum. J. Dent. Res. 2003, 82, 206–211. [CrossRef]

- Mount, G.J. Buonocore Memorial Lecture. Glass-ionomer cements: past, present and future. Oper Dent. 1994, 19, 82–90.

- Wilson, A.D.; E Kent, B. A new translucent cement for dentistry. The glass ionomer cement. Br. Dent. J. 1972, 132, 133–135. [CrossRef]

- Tungare S, Paranjpe AG. Early Childhood Caries. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- Loesche, W.J. Nutrition and dental decay in infants. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1985, 41, 423–435. [CrossRef]

- Dinis, M.; Agnello, M.; Cen, L.; Shokeen, B.; He, X.; Shi, W.; Wong, D.T.W.; Lux, R.; Tran, N.C. Oral Microbiome: Streptococcus mutans/Caries Concordant-Discordant Children. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 782825. [CrossRef]

- Gross, E.L.; Beall, C.J.; Kutsch, S.R.; Firestone, N.D.; Leys, E.J.; Griffen, A.L. Beyond Streptococcus mutans: Dental Caries Onset Linked to Multiple Species by 16S rRNA Community Analysis. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e47722. [CrossRef]

- Koo, H.; Xiao, J.; Klein, M.I.; Jeon, J.G. Exopolysaccharides Produced by Streptococcus mutans Glucosyltransferases Modulate the Establishment of Microcolonies within Multispecies Biofilms. J. Bacteriol. 2010, 192, 3024–3032. [CrossRef]

- Caufield, P.; Schön, C.; Saraithong, P.; Li, Y.; Argimón, S. Oral Lactobacilli and Dental Caries: A Model for Niche Adaptation in Humans. J. Dent. Res. 2015, 94, 110S–118S. [CrossRef]

- Al-Batayneh, O.B.; Al-Rai, S.A.; Khader, Y.S. Effect of CPP-ACP on Streptococcus mutans in saliva of high caries-risk preschool children: a randomized clinical trial. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent. 2019, 21, 339–346. [CrossRef]

- Kakoti D, Chakravarty T, Kashyap N, Kumar B. Evaluation of the Effects of Application of CPP-ACP and GIC Restorations on Salivary Mutans Streptococcus in Children with Early Childhood Caries. J Res Adv Dent. 2021;12(1):45-50.

- Farooq, I.; Moheet, I.A.; Imran, Z.; Farooq, U. A review of novel dental caries preventive material: Casein phosphopeptide–amorphous calcium phosphate (CPP–ACP) complex. King Saud Univ. J. Dent. Sci. 2013, 4, 47–51. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, I.S.; Mei, M.L.; Zhou, Z.L.; Burrow, M.F.; Lo, E.C.-M.; Chu, C.-H. Shear Bond Strength and Remineralisation Effect of a Casein Phosphopeptide-Amorphous Calcium Phosphate-Modified Glass Ionomer Cement on Artificial “Caries-Affected” Dentine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1723. [CrossRef]

- Zahara, A.M.; Fashihah, M.H.; Nurul, A.Y. Relationship between Frequency of Sugary Food and Drink Consumption with Occurrence of Dental Caries among Preschool Children in Titiwangsa, Kuala Lumpur. Malays J Nutr. 2010, 16, 83–90.

- Moynihan, P.J.; Kelly, S.A. Effect on Caries of Restricting Sugars Intake: Systematic review to inform WHO guidelines. J. Dent. Res. 2014, 93, 8–18. [CrossRef]

- Nakai, Y.; Mori-Suzuki, Y. Impact of Dietary Patterns on Plaque Acidogenicity and Dental Caries in Early Childhood: A Retrospective Analysis in Japan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2022, 19, 7245. [CrossRef]

- Joshi N, Sharma A, Garg R. Effect of CPP-ACP Application and Restoration of Primary Teeth on Salivary Mutans Streptococcus in Children with Early Childhood Caries. J Adv Med Dent Scie Res. 2018;6(4):87-90.

- Svanberg, M.; Mjör, I.; Ørstavik, D. Mutans Streptococci in Plaque from Margins of Amalgam, Composite, and Glass-ionomer Restorations. J. Dent. Res. 1990, 69, 861–864. [CrossRef]

- Sitthisettapong, T.; Phantumvanit, P.; Huebner, C.; DeRouen, T. Effect of CPP-ACP Paste on Dental Caries in Primary Teeth: A randomized trial. J. Dent. Res. 2012, 91, 847–852. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xie, X.; Wang, Y.; Yin, W.; Antoun, J.S.; Farella, M.; Mei, L. Long-term remineralizing effect of casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate (CPP-ACP) on early caries lesions in vivo: A systematic review. J. Dent. 2014, 42, 769–777. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).