1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is clinically characterized by an early deficit in episodic memory, concerning spatiotemporal context [

1,

2], along with extracellular senile plaques and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles (NFT) [

3]. The amyloid plaques harbor heterogeneous aggregates of amyloid beta (

Aβ) peptides containing 40 (Aβ

1-40) or 42

(Aβ1-42) amino acid residues.

The amyloid cascade hypothesis initially suggested that Aβ deposition was the primary trigger for AD as it was found to precede and influence the tau pathology [

4]. Later, findings revealed that cognitive impairment [

5] and synaptic dysfunction [

6] were correlated and coincided with

a rise in the level of Aβ oligomers [

7]

, even without the formation of amyloid plaques. Consequently,

the earliest amyloid toxicities in AD have been modified to

be associated with soluble Aβ

species [

8,

9].

The generation of transgenic animals overexpressing proteins related to familial AD, mutant APP (amyloid precursor protein) and PS (presenilin) is based on the amyloid hypothesis that cognitive deficit was linked to plaque formation [

10]. With an attempt to replicate the hallmarks of AD including senile plaques, these animals develop age-dependent amyloid pathology in a spatiotemporal manner which closely mimics disease progression in human [

4,

11]. However, both intrinsic and extrinsic factors modulate the course and outcome of these models [

12]. More importantly, the presence of amyloid plaques may not account for memory deficits. Moreover, memory impairment cannot also be directly related to a specific dysfunction of a particular brain area [

11].

On the other hand, injection of Aβ oligomers into a specific brain region is required as an alternative to understand the effects of increased soluble Aβ species without the presence of any plaques [

1]. Unlike the transgenic model, the injection model allows us to control the concentration of Aβ oligomers spatiotemporally and

recapitulate the cardinal features of early AD [

1]

. Using wild-type strain also provides an excellent in vivo model as it can circumvent the potential side effects from the gene mutations. In this context, adverse effects associated with the early Aβ pathology could be identified, thereby preventing cognitive impairment and interfering with advanced neurodegenerative processes [

12].

Therefore, we will review why injection of Aβ1-42 oligomers is a valid model to investigate early stage of AD pathology and why dorsal CA1 region is a target area to understand the adverse effects of Aβ1-42 oligomers related to contextual memory.

2. Transgenic Model vs. Injection Model

Transgenic animals, mice and rats [

13,

14], which express the mutant forms of APP and/or PS gene have enabled us to study AD-related pathologies. These models share a common feature of increased Aβ production, leading to formation and deposition of amyloid plaques [

15]. By recapitulating the neuropathological features of AD [

10] and exhibiting a chronic, progressive spectrum of disease [

16], these models appear to phenocopy the critical aspects of human AD. Thus, they have represented a promising niche for investigating Aβ pathology and testing the efficacy of therapeutic interventions.

However, these models are based on familial AD-associated gene mutations which only account for < 1% of AD cases [

13]. By contrast, clinical AD results from a complex interaction of multiple etiologies, rather than a single involvement of genes [

17]. Next, using transgenic animals is time-consuming because it takes months or years to develop Aβ plaques which do not have a clear relationship with cognitive impairments. Resembling advanced AD, they are lacking early AD-associated pathological changes. The appearance of AD-related phenotypes could be confounded by several factors such as species, age, etc [

12]. More importantly, they develop AD phenotypes not in chronological order and thus are not equivalent to human AD. For example, plaque deposition is preceded by cellular changes and cognitive impairments [

10].

To overcome the shortcomings of the transgenic models, injection of Aβ oligomers has been alternatively used. Firstly, the dose of oligomers, the route of injection and the age of animals can be adjusted to minimize the experimental contributing factors. Next, the wild-type strain can circumvent the by-stander effects of the recipient genes derived from introduction of exogenous genes’ mutations [

16]. Moreover, the key advantage of this model can be partly explained by the facts that any brain region can be targeted [

1] and the oligomers are rapidly delivered to the area of interest [

18]. Most importantly, the greatest benefit of this Aβ-injected model is its credibility as pathological changes are directly triggered by the Aβ oligomers.

As a rise in soluble Aβ species in a certain brain area has been regarded as a starting phenomenon in AD, the oligomer injection is a valid model to investigate the early stage of AD pathology [

1,

15].

Injecting either natural or synthetic Aβ1-42 oligomers can trigger synaptic dysfunction, astrogliosis and cognitive deficits [

18,

19,

20]. Moreover, these features can be directly linked to specific dysfunction of a particular brain area due to amyloid deposition [

18,

21]. However, having considered the chronic nature of AD rather than a sudden surge of oligomers, the transgenic models are also recommended to strengthen the findings from the Aβ oligomer-injected models [

16].

3. Why Is Understanding Hippocampal CA1 Region Important?

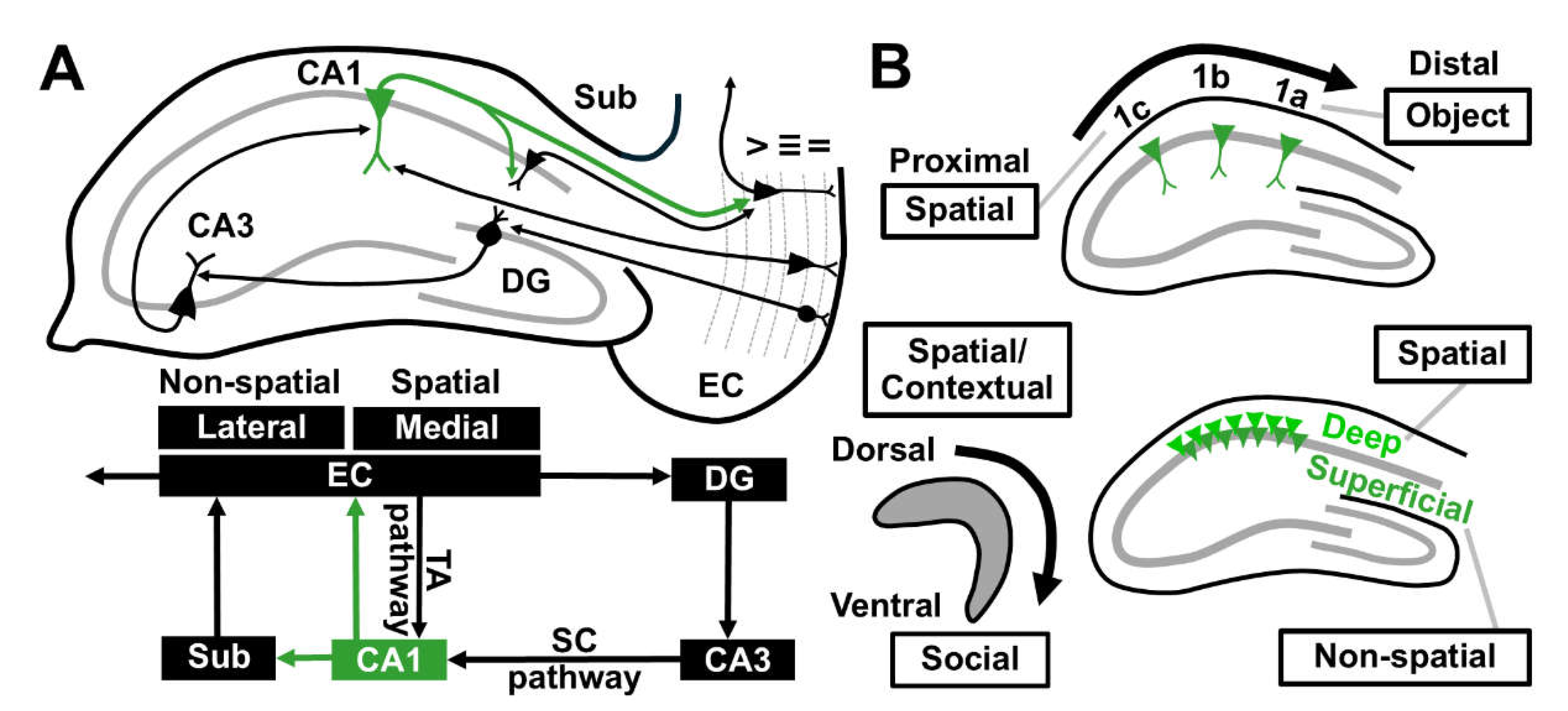

A typical CA1 (Cornu ammonis 1) pyramidal neuron (CA1 PN) receives most glutamatergic inputs from the entorhinal cortex (EC). The classical trisynaptic circuitry originates from projections of the EC layer 2 stellate cells, via perforant path (PP), to dentate gyrus (DG) granule cells whose mossy fibers synapse with CA3 PNs, which in turn excite CA1 PNs through the Schaffer collateral (SC) pathway. In addition, direct glutamatergic projections from EC layer 3 PNs also reach CA1 PNs through the temporo-ammonic (TA) pathway. The trisynaptic and monosynaptic circuits convergence at the proximal and distal apical dendrites of CA1 PNs, respectively [

22,

23]. Finally, CA1 integrates non-spatial information from the lateral entorhinal cortex (LEC) and spatial information from the medial entorhinal cortex (MEC) and provides the primary output of the hippocampus, along with subiculum to the extrahippocampal circuits (

Figure 1A) [

22].

The hippocampal CA1 region shows functional, intrinsic and synaptic heterogeneities across the longitudinal (dorso-ventral), transverse (proximo-distal) and radial (deep-superficial) axes despite its homogeneous cytoarchitecture [

24,

25]. Firstly, dorsal CA1 is particularly engaged in the formation of spatial and contextual memories [

26] whereas ventral CA1 PNs mediate social-related cues [

27]. Along the transverse axis, proximal CA1 PNs exhibit specific firing towards spatial information [

28] whereas activation of distal CA1 PNs corresponds to object memory encoding [

29,

30]. Compared to superficial PNs, deep CA1 PNs are more likely to have place fields and are highly activated during spatial processing (

Figure 1B) [

31]. This functional diversity reflects differential behavioral role of the hippocampal CA1 subfields in different axes.

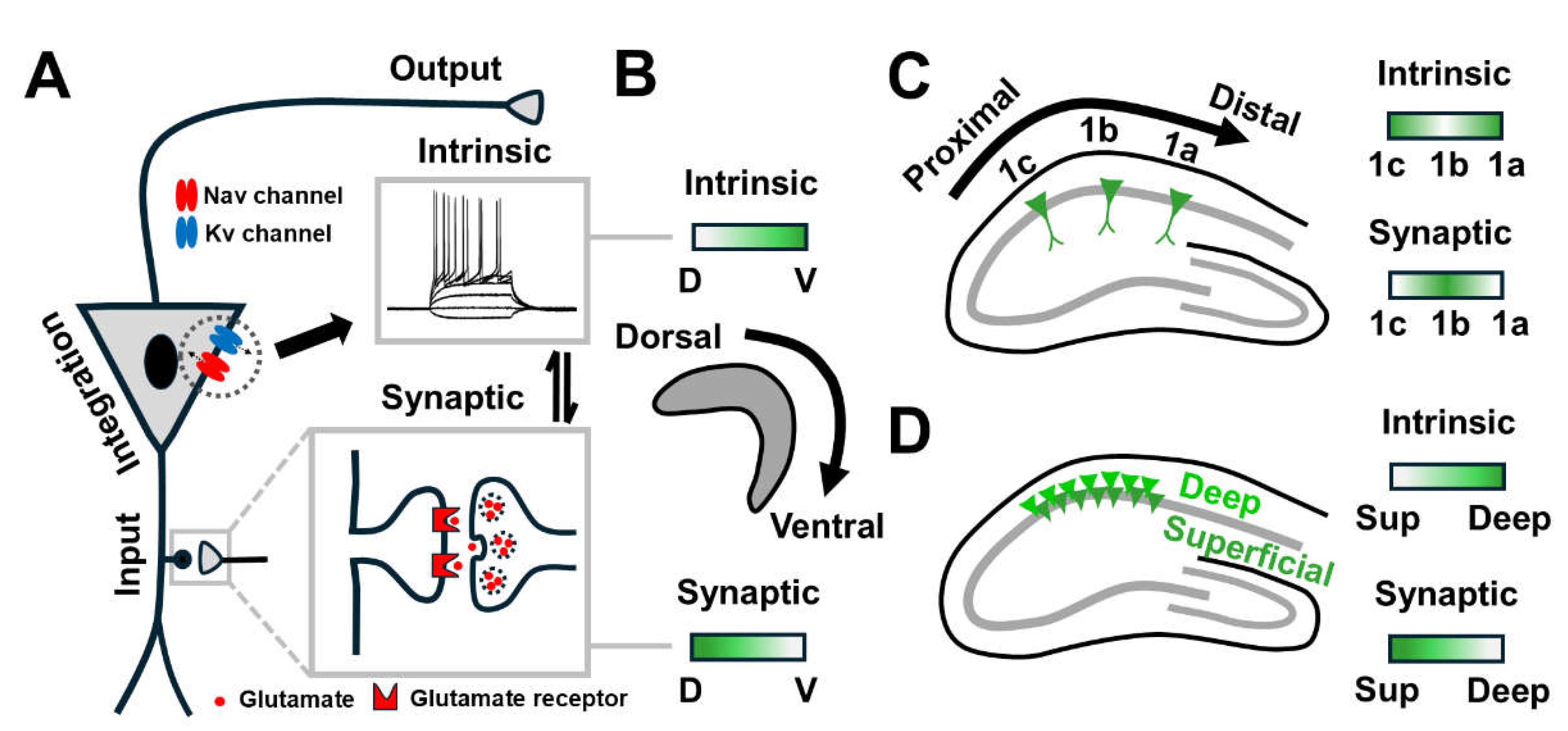

These in vivo functional differences can also be contributed by variations in the input-output function of CA1 PNs. Fundamentally, a neuron integrates synaptic inputs and decides whether to fire an action potential (AP) or not. The intrinsic excitability (IE) determines its likelihood of firing in response to synaptic inputs and is therefore a crucial link between synaptic input and action potential output (

Figure 2A) [

32]. Though controlled by independent mechanisms, both forms of plasticity are interdependent [

33]. Indeed, both are tightly coupled and bi-directionally adjusted in CA1 PNs so that neuronal activity is maintained to prevent extreme modifications [

34].

Yet, how these properties can be directly translated to in vivo responses is controversial owing to the striking topographical differences [

35]. For example, ventral CA1 PNs form a weaker and less stable synaptic plasticity [

36,

37], but are also more excitable than dorsal PNs (

Figure 2B) [

38]. In the dorsal hippocampus, similar synaptic and intrinsic properties are found at CA1a and CA1c PNs whereas CA1b is distinguished by having lower intrinsic excitability with higher synaptic integrating properties (

Figure 2C) [

35]. Next, synaptic plasticity of CA1 PNs is more robust in the superficial layer [

39] whereas deep CA1 PNs elicit higher firing in the dorsal region (

Figure 2D) [

35]. These findings suggest that these axis-dependent differences may be related to the expression/function of ion channels as well as receptors underlying intrinsic and synaptic properties.

4. Why Is Hippocampal CA1 Relevant as a Target Area to Study AD Pathology?

The CA1 region, which integrates and processes contextual [

40] and spatial information [

41], is affected in in the early stage of AD. Interestingly, it shows spatiotemporal pattern of amyloid deposition along its anatomical axes [

24]. For example, ventral CA1 has a higher amyloid plaque burden than its dorsal pole [

42]. Across the transverse axis, amyloid deposits appear more abundantly in the distal CA1 region than the proximal CA1 [

43]. However, the impact of amyloid on the radial axis is still unknown. Taken together, CA1 PNs exhibit axis-linked differential susceptibility to AD pathology.

Selective vulnerability of CA1 PNs with non-uniform functions may underline selective loss of a particular modality of memory. In the context of functional in vivo consequences, spatial memory deficits can be related to specific dysfunction of dorsal CA1 PNs. Place cells in the dorsal CA1 became damaged along with nearby Aβ aggregates [

2] which was accompanied by spatial memory deficits [

44]. Yet, there is no clear evidence to characterize such functional impairments in ventral CA1 and across the other two axes.

Owing to the contrasting heterogeneities of CA1, specific targeting of its subfield is important not to miss axis-linked implications in the functional consequences of AD. This leads to direct injection of oligomeric Aβ

1-42 into the dorsal CA1 region which shows Aβ

1-42 oligomer-induced deficits in spatial working memory [

1,

45]

, in association with synaptic dysfunction [

46]

and Aβ deposition at the injected site [

47]. Thus, this CA1 injection model which directly links Aβ oligomers with amyloid-related pathology is valid to advance our understanding of cognitive deficits in AD.

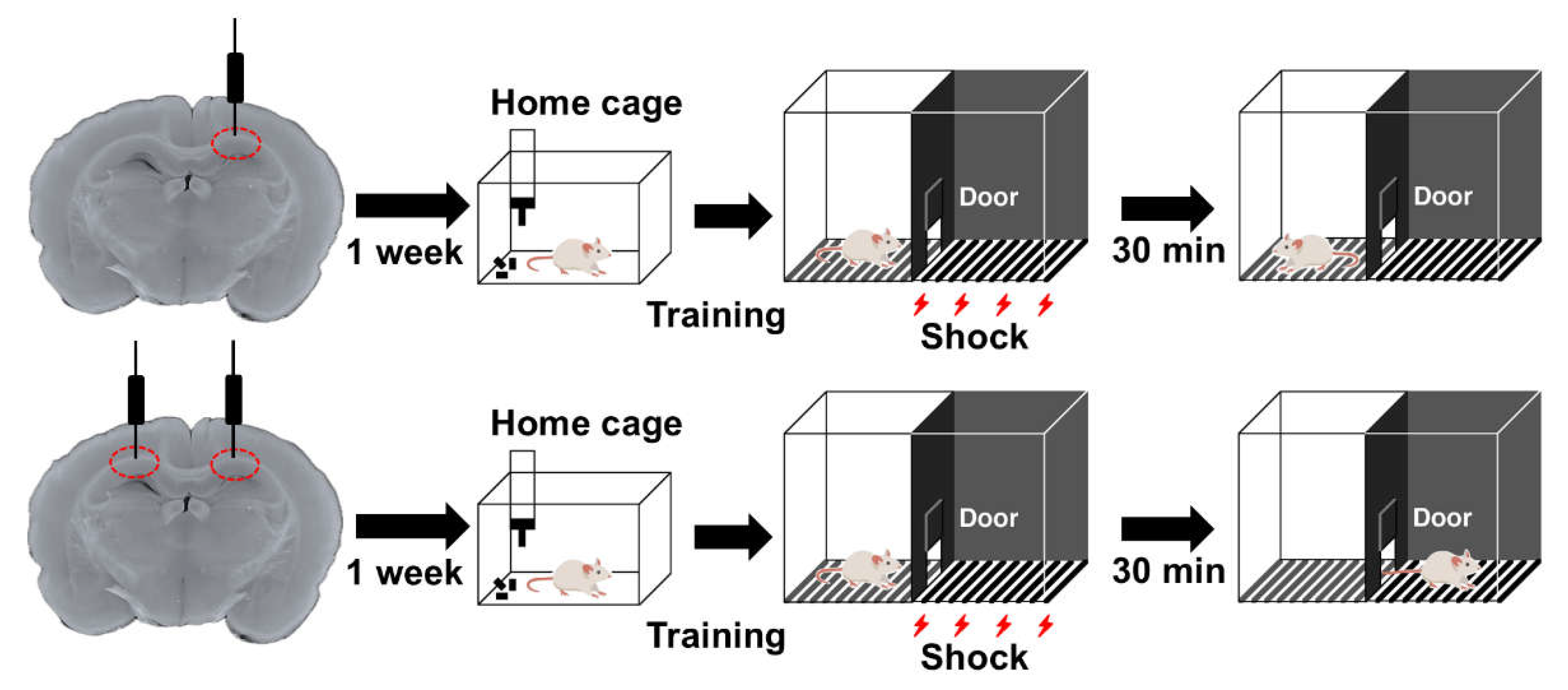

5. Effect of Injecting Aβ1-42 Oligomers into Dorsal CA1 on Contextual Memory

Here, we will focus on contextual memory because of the rapid and stable development of associative learning and its clear relationship with dorsal CA1 [

48]. The inhibitory avoidance (IA) task, a learning paradigm for contextual memory, is based on associating the training context with the aversive stimulus after the foot shock [

49]. Briefly, contextual learning requires a certain period of exploration prior to shock during which spatial and non-spatial features of the environment are integrated. After receiving shock, if the animals have learnt the context-shock pairing, they will stay in the lit area which they would normally not prefer. Thus, the prolonged latency to enter the dark box indicates formation of contextual memory.

Several studies supported that encoding and retrieval of contextual memory require dorsal CA1 [

26,

27]. Similar to in vitro HFS (high-frequency stimulation), induction of NMDA (N-methyl-D-aspartate)-dependent LTP (long-term potentiation) [

48] is followed by delivery of GluR1-containing AMPARs (α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor) to the CA3-CA1 synapses [

50], resulting in increased number of AMPARs [

49] after contextual learning. Moreover, formation of contextual memory strengthens synaptic transmission at both excitatory (AMPAR) and inhibitory (GABA

AR) (γ-aminobutyric acid receptor) synapses [

49,

51] under the cholinergic control [

51]. Next, enhanced plasticity in the CA1b region suggests processing and integrating spatial and non-spatial information necessary for establishing contextual memory [

52]. That is why this one-trial IA task is a relevant learning paradigm to study the adverse effects of oligomers on the dorsal CA1 region.

As CA1b displays robust processing of its mixed input [

35] and assembles information necessary for IA learning [

52], we aimed to elucidate the effects of Aβ

1-42 oligomers on contextual memory by injecting into this target region. Previously, we found that unilateral injection of Aβ

1-42 oligomers did not affect learning performance whereas bilateral injection shortened the latency (

Figure 3) [

53]. This was in accordance with our previous finding that bilateral dorsal CA1 is required for contextual learning [

51]. We also assured that this contextual impairment was not influenced by motor, sensory and emotional changes. More importantly, this Aβ

1-42 oligomer-induced behavioral consequence can be directly related to dorsal CA1 dysfunction as the electrophysiological properties of CA1 PNs were adversely affected along with concomitant deposition of Aβ

1-42 oligomers in the target region [

53].

6. Conclusions

Significant progress has been made to explore the relationship of Aβ oligomers with specific dysfunction of hippocampal CA1 region. Linking the diversity of CA1 PNs to their functional outcome and specifying the adverse effects of Aβ1-42 oligomers on dorsal CA1 will lead to a better understanding of episodic memory impairment in AD and will provide a niche for therapeutic interventions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.-K.-W.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.-K.-W.-M.; writing—review and editing, D.M.; visualization, M.-K.-W.-M. and D.M.; supervision, D.M.; funding acquisition, D.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research C (D.M. Grant No. 23K06348), Scientific Research B (D.M. Grants No. 16H05129 and 19H03402), and Scientific Research in Innovative Areas (D.M. Grant No. 26115518), from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan. This project was also supported by the YU AI project of the Center for Information and Data Science Education.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| Aβ |

Amyloid beta |

| AD |

Alzheimer’s disease |

| AMPAR |

α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor |

| AP |

Action potential |

| APP |

Amyloid precursor protein |

| CA1 |

Cornu ammonis 1 |

| DG |

Dentate gyrus |

| EC |

Entorhinal cortex |

| GABAAR |

γ-aminobutyric acid receptor |

| HFS |

High-frequency stimulation |

| IA task |

Inhibitory avoidance task |

| IE |

Intrinsic excitability |

| Kv channel |

Voltage-gated potassium channel |

| LEC |

Lateral entorhinal cortex |

| LTP |

Long-term potentiation |

| MEC |

Medial entorhinal cortex |

| Nav channel |

Voltage-gated sodium channel |

| NFT |

Neurofibrillary tangle |

| NMDA |

N-methyl-D-aspartate |

| PN |

Pyramidal neuron |

| PP |

Perforant path |

| PS |

Presenilin |

| SC |

Schaffer collateral |

| TA |

Temporo-ammonic |

References

- Chambon, C.; Wegener, N.; Gravius, A.; Danysz, W. Behavioural and cellular effects of exogenous amyloid-β peptides in rodents. Behav. Brain Res. 2011, 225, 623–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takamura, R.; Mizuta, K.; Sekine, Y.; Islam, T.; Saito, T.; Sato, M.; Ohkura, M.; Nakai, J.; Ohshima, T.; Saido, T.C.; et al. Modality-specific impairment of hippocampal CA1 neurons of Alzheimer’s disease model mice. J. Neurosci. 2021, 41, 5315–5329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeTure, M.A.; Dickson, D.W. The neuropathological diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol Neurodegeneration 2019, 14, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oddo, S. Amyloid deposition precedes tangle formation in a triple transgenic model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2003, 24, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Dam, D.; D’Hooge, R.; Staufenbiel, M.; Van Ginneken, C.; Van Meir, F.; De Deyn, P.P. Age-dependent cognitive decline in the APP23 model precedes amyloid deposition. Eur J of Neuroscience 2003, 17, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mucke, L.; Masliah, E.; Yu, G.-Q.; Mallory, M.; Rockenstein, E.M.; Tatsuno, G.; Hu, K.; Kholodenko, D.; Johnson-Wood, K.; McConlogue, L. High-level neuronal expression of Aβ1–42 in wild-type human amyloid protein precursor transgenic mice: Synaptotoxicity without plaque formation. J. Neurosci. 2000, 20, 4050–4058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandy, S.; Simon, A.J.; Steele, J.W.; Lublin, A.L.; Lah, J.J.; Walker, L.C.; Levey, A.I.; Krafft, G.A.; Levy, E.; Checler, F.; et al. Days to criterion as an indicator of toxicity associated with human Alzheimer amyloid-β oligomers. Ann. Neurol. 2010, 68, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, J.; Selkoe, D.J. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s Disease: Progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science 2002, 297, 353–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hector, A.; Brouillette, J. Hyperactivity induced by soluble amyloid-β oligomers in the early stages of Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2021, 13, 600084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elder, G.A.; Gama Sosa, M.A.; De Gasperi, R. Transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer’s Disease. Mt. Sinai J Med. 2010, 77, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, M.; Kobayashi, H.; Tatsumi, L.; Tomita, T. Mouse models of Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2022, 15, 912995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLarnon, J.; Ryu, J. Relevance of Aβ 1-42 intrahippocampal injection as an animal model of inflamed Alzheimer’s Disease brain. CAR 2008, 5, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spires, T.L.; Hyman, B.T. Transgenic models of Alzheimer’s Disease: Learning from animals. Neurotherapeutics 2005, 2, 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedikz, E.; Kloskowska, E.; Winblad, B. The rat as an animal model of Alzheimer’s Disease. J Cellular Molecular Medi 2009, 13, 1034–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stéphan, A.; Phillips, A.G. A case for a non-transgenic animal model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Genes Brain Behav. 2005, 4, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.Y.; Lee, D.K.; Chung, B.-R.; Kim, H.V.; Kim, Y. Intracerebroventricular injection of amyloid-β peptides in normal mice to acutely induce Alzheimer-like cognitive deficits. JoVE 2016, No. 109, 53308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokjohn, T.A.; Roher, A.E. Amyloid precursor protein transgenic mouse models and Alzheimer’s Disease: Understanding the paradigms, limitations, and contributions. Alzheimer’s Amp; Dement. 2009, 5, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouillette, J.; Caillierez, R.; Zommer, N.; Alves-Pires, C.; Benilova, I.; Blum, D.; De Strooper, B.; Buee, L. Neurotoxicity and memory deficits induced by soluble low-molecular-weight amyloid- 1-42 oligomers are revealed in vivo by using a novel animal model. J. Neurosci. 2012, 32, 7852–7861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, G.M.; Li, S.; Mehta, T.H.; Garcia-Munoz, A.; Shepardson, N.E.; Smith, I.; Brett, F.M.; Farrell, M.A.; Rowan, M.J.; Lemere, C.A.; et al. Amyloid-β protein dimers isolated directly from Alzheimer’s brains impair synaptic plasticity and memory. Nat Med 2008, 14, 837–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forny-Germano, L.; Lyra E Silva, N.M.; Batista, A.F.; Brito-Moreira, J.; Gralle, M.; Boehnke, S.E.; Coe, B.C.; Lablans, A.; Marques, S.A.; Martinez, A.M.B.; et al. Alzheimer’s disease-like pathology induced by amyloid-β oligomers in nonhuman primates. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 13629–13643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, R.; Cechetto, D.; Whitehead, S. Assessing the effects of acute amyloid β oligomer exposure in the rat. IJMS 2016, 17, 1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basu, J.; Siegelbaum, S.A. The corticohippocampal circuit, synaptic plasticity, and memory. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2015, 7, a021733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witter, M.P.; Doan, T.P.; Jacobsen, B.; Nilssen, E.S.; Ohara, S. Architecture of the Entorhinal Cortex A Review of Entorhinal Anatomy in Rodents with Some Comparative Notes. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masurkar, A.V. Towards a circuit-level understanding of hippocampal CA1 dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease across anatomical axes. J Alzheimers Dis Parkinsonism 2018, 8, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soltesz, I.; Losonczy, A. CA1 pyramidal cell diversity enabling parallel information processing in the hippocampus. Nat Neurosci 2018, 21, 484–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakazawa, Y.; Pevzner, A.; Tanaka, K.Z.; Wiltgen, B.J. Memory retrieval along the proximodistal axis of CA1. Hippocampus 2016, 26, 1140–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuyama, T.; Kitamura, T.; Roy, D.S.; Itohara, S.; Tonegawa, S. Ventral CA1 neurons store social memory. Science 2016, 353, 1536–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, A.; Fernández-Ruiz, A.; Buzsáki, G.; Berényi, A. Spatial coding and physiological properties of hippocampal neurons in the Cornu Ammonis subregions. Hippocampus 2016, 26, 1593–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, H.T.; Schuman, E.M. Functional division of hippocampal area CA1 via modulatory gating of entorhinal cortical inputs. Hippocampus 2012, 22, 372–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, N.H.; Flasbeck, V.; Maingret, N.; Kitsukawa, T.; Sauvage, M.M. Proximodistal segregation of nonspatial information in CA3: Preferential recruitment of a proximal CA3-distal CA1 network in nonspatial recognition memory. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 11506–11514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuseki, K.; Diba, K.; Pastalkova, E.; Buzsáki, G. Hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells form functionally distinct sublayers. Nat Neurosci 2011, 14, 1174–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magee, J.C. Dendritic integration of excitatory synaptic input. Nat Rev Neurosci 2000, 1, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, A.R.; Kaczorowski, C.C. Regulation of intrinsic excitability: Roles for learning and memory, aging and Alzheimer’s disease, and genetic diversity. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2019, 164, 107069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasselin, C.; Inglebert, Y.; Debanne, D. Homeostatic regulation of h-conductance controls intrinsic excitability and stabilizes the threshold for synaptic modification in CA1 neurons. J. Physiol. 2015, 593, 4855–4869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masurkar, A.V.; Tian, C.; Warren, R.; Reyes, I.; Lowes, D.C.; Brann, D.H.; Siegelbaum, S.A. Postsynaptic integrative properties of dorsal CA1 pyramidal neuron subpopulations. J. Neurophysiol. 2020, 123, 980–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouvaros, S.; Papatheodoropoulos, C. Theta burst stimulation-induced LTP: Differences and similarities between the dorsal and ventral CA1 hippocampal synapses. Hippocampus 2016, 26, 1542–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruki, K.; Izaki, Y.; Nomura, M.; Yamauchi, T. Differences in paired-pulse facilitation and long-term potentiation between dorsal and ventral CA1 regions in anesthetized rats. Hippocampus 2001, 11, 655–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougherty, K.A.; Islam, T.; Johnston, D. Intrinsic excitability of CA1 pyramidal neurones from the rat dorsal and ventral hippocampus. J. Physiol. 2012, 590, 5707–5722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masurkar, A.V.; Srinivas, K.V.; Brann, D.H.; Warren, R.; Lowes, D.C.; Siegelbaum, S.A. Medial and lateral entorhinal cortex differentially excite deep versus superficial CA1 pyramidal neurons. Cell Reports 2017, 18, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.; Kesner, R.P. Differential contributions of dorsal hippocampal subregions to memory acquisition and retrieval in contextual fear-conditioning. Hippocampus 2004, 14, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ásgeirsdóttir, H.N.; Cohen, S.J.; Stackman, R.W. Object and place information processing by CA1 hippocampal neurons of C57BL/6J mice. J. Neurophysiol. 2020, 123, 1247–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, M.L.; Molina-Campos, E.; Ybarra, N.; Rogalsky, A.E.; Musial, T.F.; Jimenez, V.; Haddad, L.G.; Voskobiynyk, Y.; D’Souza, G.X.; Carballo, G.; et al. Variability in sub-threshold signaling linked to Alzheimer’s disease emerges with age and amyloid plaque deposition in mouse ventral CA1 pyramidal neurons. Neurobiol. Aging 2021, 106, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aamer, A.; Reyes, I.; Tian, C.; Thangavel, M.; Masurkar, A. Differential susceptibility of CA1 pyramidal neuron subpopulations to neurodegeneration in the 5xFAD model of amyloidosis (P3-3.020). Neurology 2024, 102, 3473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, L.; Johnston, K.G.; Crapser, J.; Green, K.N.; Ha, N.M.-L.; Tenner, A.J.; Holmes, T.C.; Nitz, D.A.; Xu, X. Degenerate mapping of environmental location presages deficits in object-location encoding and memory in the 5xFAD mouse model for Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2023, 176, 105939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faucher, P.; Mons, N.; Micheau, J.; Louis, C.; Beracochea, D.J. Hippocampal injections of oligomeric amyloid β-peptide (1–42) induce selective working memory deficits and long-lasting alterations of ERK signaling pathway. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppensteiner, P.; Trinchese, F.; Fà, M.; Puzzo, D.; Gulisano, W.; Yan, S.; Poussin, A.; Liu, S.; Orozco, I.; Dale, E.; et al. Time-dependent reversal of synaptic plasticity induced by physiological concentrations of oligomeric Aβ42: An early index of Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 32553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Liu, J.; Ruan, Z.; Tian, S.; Ma, Y.; Zhu, J.; Li, G. Intrahippocampal injection of Aβ1-42 inhibits neurogenesis and down-regulates IFN-γ and NF-κB expression in hippocampus of adult mouse brain. Amyloid 2013, 20, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitlock, J.R.; Heynen, A.J.; Shuler, M.G.; Bear, M.F. Learning induces long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. Science 2006, 313, 1093–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakimoto, Y.; Kida, H.; Mitsushima, D. Temporal dynamics of learning-promoted synaptic diversity in CA1 pyramidal neurons. The FASEB Journal 2019, 33, 14382–14393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsushima, D.; Ishihara, K.; Sano, A.; Kessels, H.W.; Takahashi, T. Contextual learning requires synaptic AMPA receptor delivery in the hippocampus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011, 108, 12503–12508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsushima, D.; Sano, A.; Takahashi, T. A cholinergic trigger drives learning-induced plasticity at hippocampal synapses. Nat Commun 2013, 4, 2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paw-Min-Thein-Oo; Sakimoto, Y. ; Kida, H.; Mitsushima, D. Proximodistal heterogeneity in learning-promoted pathway-specific plasticity at dorsal CA1 synapses. Neuroscience 2020, 437, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min-Kaung-Wint-Mon; Kida, H. ; Kanehisa, I.; Kurose, M.; Ishikawa, J.; Sakimoto, Y.; Paw-Min-Thein-Oo; Kimura, R.; Mitsushima, D. Adverse effects of Aβ1-42 oligomers: Impaired contextual memory and altered intrinsic properties of CA1 pyramidal neurons. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).