1. Introduction

Spermatogenesis is a complex process that takes place within the seminiferous tubules of the testes, by which haploid male gametes, known as spermatozoa, are produced in mammals (Suede et al., 2025). This process requires a highly specialized environment to support the development and maturation of sperm cells that is provided by somatic cells like Sertoli, Leydig and Peritubular Myoid cells (PTM). Nurtured by hormones and growth factors secreted to the environment, germ cells perform proliferation, differentiation and spermiogenesis involving spermatogonia, spermatocyte and spermatid to produce mature sperm (Oatley & Brinster, 2012). The proliferation phase, known as mitotic phase, involves the mitotic division of spermatogonia stem cells (SSC) located along the basal membrane of the seminiferous tubules. These rounds of mitotic divisions drives to the expansion of the spermatogonial population before entering the differentiation stage, ensuring a continuous supply of germ cells throughout the reproductive life of the male. During differentiation, the primary spermatocytes transition into haploid cells. The process begins with meiosis I. Each secondary spermatocyte then undergoes meiosis II, resulting in four haploid spermatids (

Figure 1) (Suede et al., 2025). Throughout meiosis, chromosomal recombination and crossover events ensure genetic diversity among the sperm cells. The final stage, spermiogenesis, involves the morphological and biochemical transformation of round spermatids into elongated spermatozoa (

Figure 5C). This includes the condensation and compaction of DNA to facilitate motility, the formation of the acrosome (an enzyme-containing cap essential for fertilization), and the development of a flagellum for movement. DNA compaction is achieved through the replacement of histones with protamines, resulting in a highly compact and transcriptionally inactive chromatin structure (Nishimura & L’Hernault, 2017). Along the whole process, apoptosis results in a crucial regulatory mechanism that eliminates defective or excess germ cells. It ensures that only genetically intact and properly differentiated sperm are produced, maintaining the balance between germ cell proliferation and maturation within the seminiferous tubules (Zakariah et al., 2022)

.

In this review, we provide an updated perspective on the critical role of hormonal, genetic and temperature regulation during spermatogenesis, and how they participate in the cellular mechanisms of germ cells through the process.

2. Hormonal Regulation in Spermatogenesis

Hormones play a crucial role in spermatogenesis by coordinating essential functions and interactions through the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis (HPG) (

Figure 2). This axis is of vital importance in gametogenesis regulation in vertebrates, both for spermatogenesis in males and folliculogenesis in females (Oduwole et al., 2021). Some studies have elucidated the evolutionary origin of the HPG axis, stating sea lampreys as the earliest evolved vertebrates. In addition, some functional roles have been attributed to gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) that acts via the HPG axis regulating reproductive mechanisms (Sower, 2018; Sower et al., 2009). This hormone, GnRH, is the key regulator of the HPG axis, which is secreted by the hypothalamus in pulses. Its function lies in stimulating the anterior pituitary gland (AP) to synthesize gonadotropins, such as, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH), and its subsequent secretion by gonadotropic cells. To reach their site of action, gonadotropins enter to the circulatory system, and they are transported to the testis, where FSH and LH act through specific G protein-coupled membrane receptors (GPCR). FSH targets Sertoli cells which, together with the developing sperm cells, comprises the cellular component of the seminiferous tubules, which function is to support spermatogenesis facilitating progression of germ cells and to nurture them promoting the development of spermatocytes and spermatids. In addition, Sertoli cells secrete Inhibin B that helps to regulate FSH release by negative feedback on AP, and anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH), which is responsible for the female reproductive structures’ regression during male development.

Moreover, FSH stimulation via FSH receptor (FSH-R) binding in Sertoli cells, activates the canonical cAMP/PKA pathway, leading to the secretion of various growth factors, such as stem cell factor (SCF) and c-kit ligand that support the survival, proliferation and differentiation of germ cells. Nonetheless, it is now clear that this is just one of several mechanisms activated by FSH stimulus to transduce intracellular signals (Ulloa-Aguirre et al., 2018). Thus, FSH plays an important role, both independently or in combination with T, in the proliferation of Sertoli cells, as well as in supporting spermatid maturation by producing signalling molecules and nutrients for this matter. After the puberty onset, when sexual maturity has been reached, FSH together with T, triggers signals mediated by Sertoli cells to propagate germ cell maturation, supply antiapoptotic survival factors and regulate adhesion complexes between germ and Sertoli cells (Oduwole et al., 2018). The effects of FSH have been classically studied using hypophysectomised or GnRH immunized animal models treated with exogenous FSH (Ramaswamy & Weinbauer, 2014a) or human patients with hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism (Nieschlag et al., 1999). These studies have shown that FSH enhances germ cell proliferation by increasing spermatogonia and spermatocytes count, but it is unable to produce spermatids in the absence of T. Additionally, FSH-R knockout animal models (Abel et al., 2000; Dierich et al., 1998) have suggested that FSH is not essential to maintain fertility, in line with the observed in studies with hypogonadotrophic patients (Schaison et al., 1993).

FSH is also necessary for spermatogonia to differentiate into primary spermatocytes. It regulates the meiotic entry by inhibiting Activin A (which promotes DNA synthesis in spermatocytes) and activating its counteractors factors Inhibin B, and IL-6 (via PKC dependent pathway). Also, it has been described, in murine Sertoli cells, that FSH promotes nociception expression via cAMP/PKA. And, in order to promote spermatocyte survival, FSH signaling was described inhibiting both intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathways through expression of Galectin -3 (L. Li et al., 2024; J. M. Wang, Li, Yang, et al., 2022).

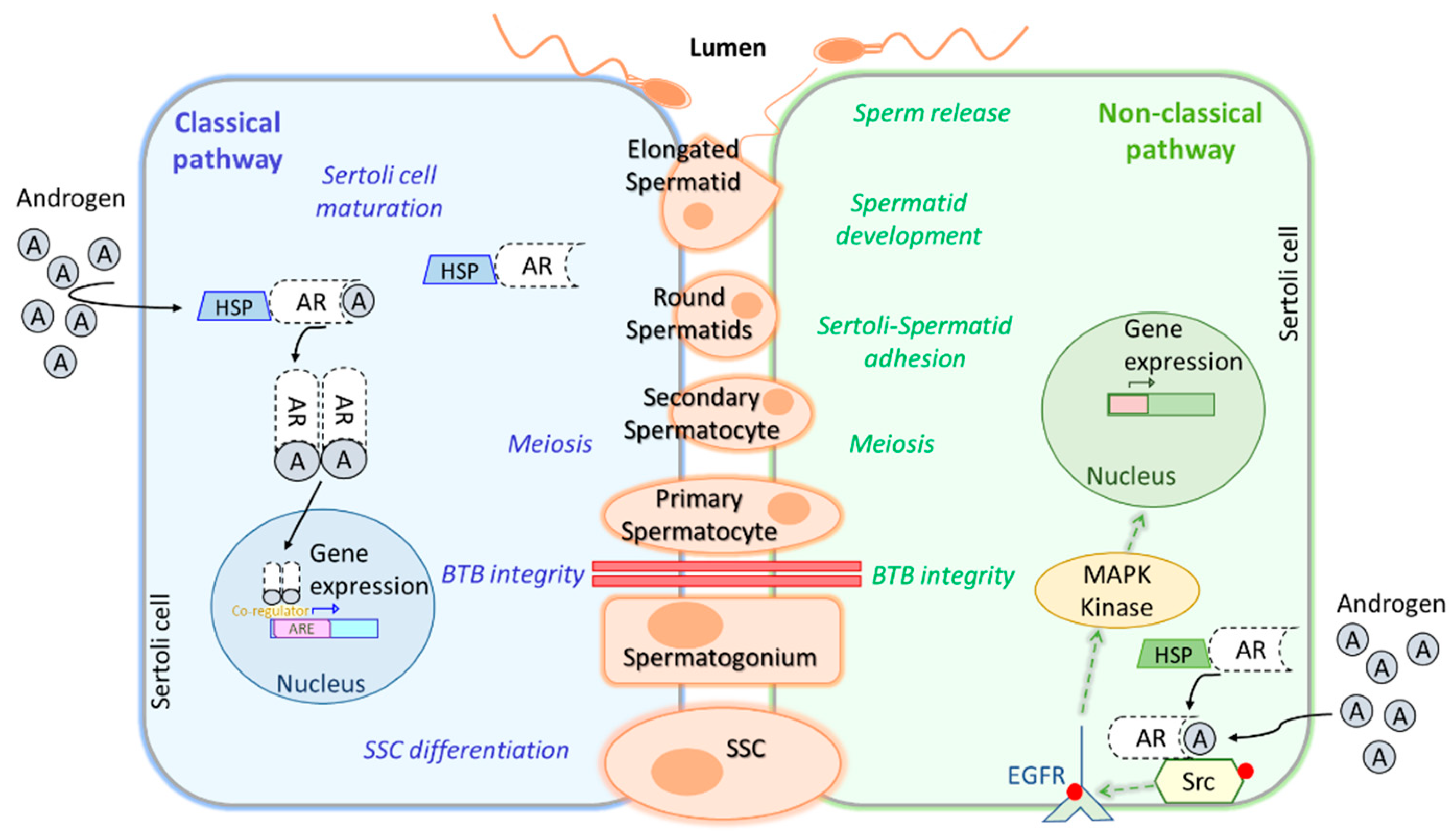

On the other hand, LH influences testicular interstitial Leydig cells. These cells are responsible for androgens production, as well as for insulin-like peptide 3 (INSL3)(L. Li et al., 2024; Oduwole et al., 2021). LH main function is to stimulate Leydig cells to produce T, which is one of the main testicular androgens, playing a crucial role in the regulation and progression of spermatogenesis in mammals (R. Zhou et al., 2019). Concretely, it is essential for the successful development of male secondary sexual characteristics. These two hormones act together as a LH/T signal and play a critical role in initiating and maintaining spermatogenesis. In

Figure 3, we summarize the classical and non-classical pathways in Sertolli cells.

T and its metabolite dihydrotestosterone (DHT) bind to androgen receptors (AR) in Sertoli cells diffusing through the plasma membrane and forming a complex that activates the classical signaling pathway (

Figure 3). Then AR dimers are translocated to the nucleus targeting a broad spectrum of genes that can promote Sertoli cells maturation, induce SSC differentiation, ensure spermatocyte meiosis, and safeguard blood-testis-barrier (BTB) integrity. Conversely, the non-classical signaling pathway starts with translocation of the AR from the cytoplasm to the plasma membrane, where it interacts with SRC proto-oncogen (Src) causing epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) phosphorylation, which activates MAPK kinases to regulate targeted gene transcription. This pathway, as well as the classical one, is involved in BTB integrity and spermatocyte meiosis, but also in the adhesion of Sertoli cells to spermatids, spermatid development and sperm release (L. Li et al., 2024a; J. M. Wang, Li, & Yang, 2022). Other non-classical pathways stimulated by T have been reviewed in J. M. Wang et al., 2022, as well as, upstream, downstream and transcription regulators participating in this complex network triggered by AR signaling during spermatogenesis. In contrast to the observations made in FSH-R knockout mouse, which was fertile, deletion of LH receptor (LH-R) in male mice has been reported to greatly reduce T levels in serum and testis and to impair spermatogenesis completion (Ramaswamy & Weinbauer, 2014). The explanation for this relies on the activation of adenylate cyclase and the increase of cyclic AMP (cAMP) levels after LH-LHR binding on Leydig cells membrane, which in turn, activates protein kinase A (PKA), activating the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR), finally leading to T synthesis from cholesterol. A study in male rats exposed to 17α-ethynylestradiol (EE2), an endocrine-disrupting chemical, has reported that EE2 treatment reduces T secretion by downregulation of LH-R pathway, leading to a decrease in cAMP, which in turn, suppresses steroidogenesis by downregulation of some steroidogenic enzymes, such as, P450 side-chain cleavage enzyme (P450scc) and StAR. These results propose a model to further investigate the mechanisms underlying T inhibition (Lin et al., 2020).

It was reviewed in A. Kumar et al. (2018), that spermiation might be controlled by FSH acting via androgen. In one of the studies, in the model of suppression of FSH and androgen it was disturbed the transcription of genes that participated in lysosome function and lipid metabolism in Sertoli cells (O’Donnell et al., 2009). Also, other hormones have been described to play a role in spermiation, such as: oestrogen contributing to actin and cytoskeletal dynamics, Retinoic Acid (RA) for cytoskeletal remodelling, oxytocin for tubular contractibility, among others. Moreover, this step has been considered a proper target for male contraception, since it is a delicate phase in different species such as rodents, monkeys and humans (A. Kumar et al., 2018).

Other key hormones that are worth mentioning on this complex regulatory network are prolactin (PRL) and estradiol (E2). PRL is synthesized and secreted by the AP and binds to its receptor PRLR on several tissues including testis, epididymis, seminal vesicle and prostate, activating the JAK-STAT signaling pathway and playing a role in male gonadal function by regulating the number of LH and FSH receptors, releasing gonadotropins, promoting steroidogenesis and spermatocyte-spermatid conversion, among other effects (Bole-Feysot et al., 1998; Raut et al., 2019). However, some KO studies for PRL or PRLR have attempted to further investigate their effect in male reproductive functions, but the results were not conclusive, remaining unclear the role of this hormone and its receptor in relation to male fertility (Binart et al., 2003; Steger et al., 1998). Regarding E2, it is produced in the testis in small amounts by aromatization of T, by action of the enzyme CYP19A1 or aromatase. E2 acts by binding to estrogen receptors ERα and ERβ, although only Erα has been reported to have a role in maintaining male fertility (Krege et al., 1998). Additionally, disruption of Cyp19 gene coding for aromatase (ArKO mice) results in decreased fertility in males of advancing age (Fisher et al., 1998).

3. Genetic Regulation in Spermatogenesis

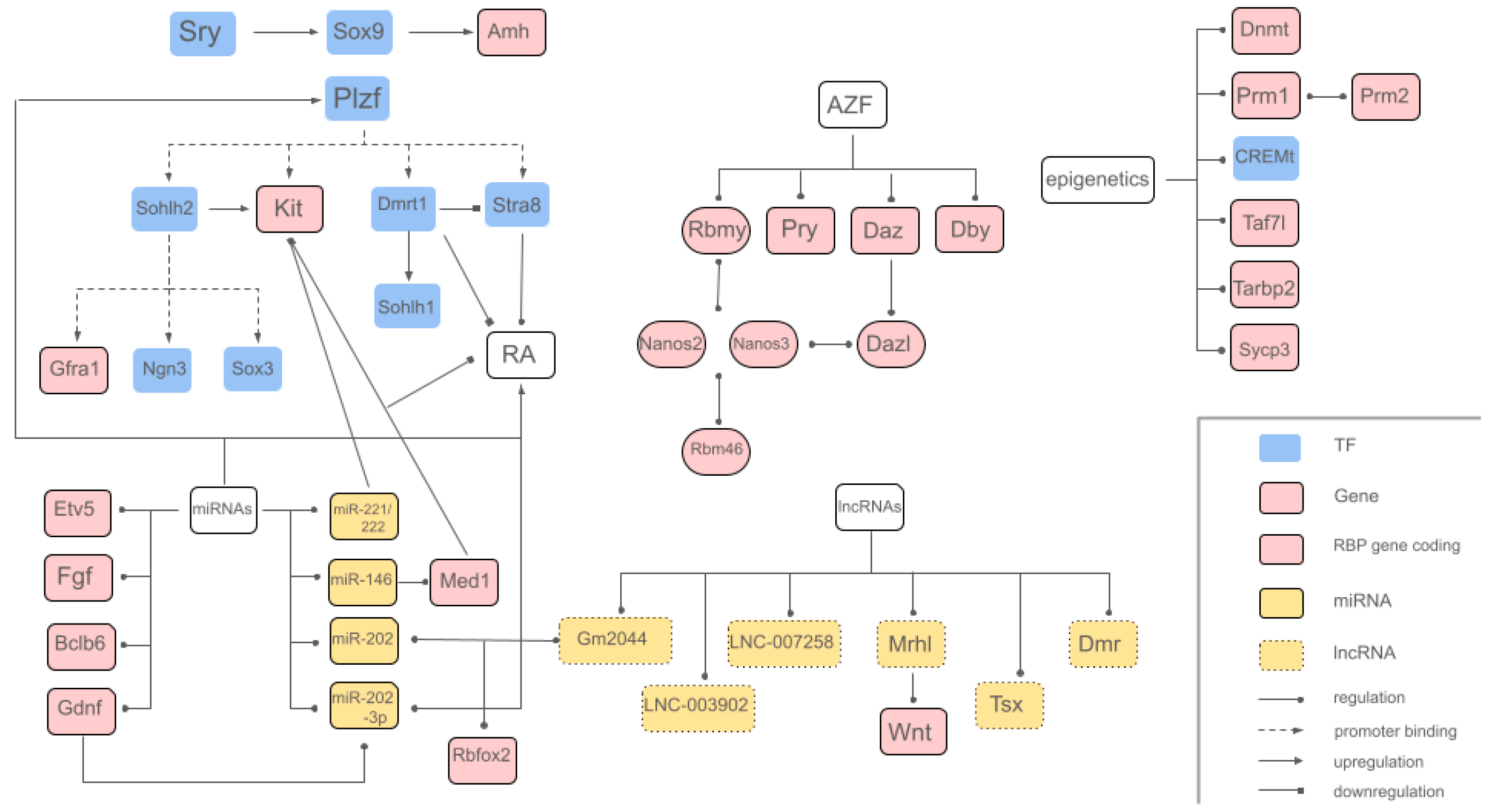

The genetic mechanisms involved in the complex process of spermatogenesis guarantee precise cell differentiation and stage-specific gene expression due to three different regulatory levels: gene regulation, transcriptional regulation and epigenetic regulation (Lui & Cheng, 2009). While numerous genes, transcription factors and other key elements are involved in spermatogenesis regulation, this review focuses on the most relevant and/or extensively studied ones, as shown in

Table 1. Key transcription factors involved in the genetic regulation of spermatogenesis include

SRY (Sex-determining Region Y) and

SOX9 (SRY-box transcription factor 9), both essential for sex determination and the development of male germ cells.

Sry, located at the distal region of the short arm of the Y chromosome, acts as the master regulator initiating testicular differentiation by activating the expression of

Sox9 in Sertoli cells (Neto et al., 2016). In turn,

Sox9 promotes the transcription of genes involved in the formation and maintenance of seminiferous tubules, such as AMH (anti-Mullerian hormone), and in the regulation of the environment necessary for spermatogenesis (MacLean & Wilkinson, 2005).

Plzf (ZBTB16) (promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger) is also a key transcription factor expressed in undifferentiated spermatogonia and is critical for SSC maintenance, where

Plzf mutation results in a progressive germ cell loss (Sharma et al., 2018). This factor regulates SSCs by direct promoter binding to differentiation-related genes, such as

Sohlh2, Kit, Stra8 and

Dmrt1, repressing them (Song et al., 2020).

Plzf knockout models are infertile and present testicular degeneration (Costoya et al., 2004). SOHLH2, expressed in type A spermatogonia, regulates spermatogenesis by binding and modulating genes, such as

Gfra1, Ngn3, and

Sox3 (Suzuki et al., 2012). Additionally, SOHLH2 promotes

Kit expression, while its downregulation results in increased PLZF levels and reduced

Kit expression (Y. Li et al., 2014; H. Suzuki et al., 2012). Another key regulator,

Stra8, an essential target of RA, governs spermatogonial differentiation; its deficiency in mice leads to spermatocyte depletion and disrupts meiotic progression (Endo et al., 2015). Furthermore,

Dmrt1 (Doublesex-mab3-related transcription factor gene family) is a differentiating marker (Guo et al., 2018) and a sexual determination gene (Song et al., 2020). It acts limiting RA response on spermatogonia, downregulating

Stra8 (Stimulated by RA 8) transcription.

Dmrt1 also activates the spermatogonial differentiation factor

Sohlh1 (Spermatogenesis and oogenesis specific basic helix-loop-helix 1) transcription, thereby blocking meiosis and inducing spermatogonia development (Du et al., 2021). In addition, there are other genes that play a crucial role in human spermatogenesis and have significant clinical relevance. The AZF (Azoospermia Factor) region on the Y chromosome comprises critical genes whose microdeletions have a direct impact on spermatogenesis, such as RNA-binding motif protein Y-linked family 1,

Ptpn13 Like Y-Linked, Deleted in Azoospermia and DEAD-box Y linked (

Rbmy1,

Pry,

Daz and

Dby), directly involved in essential germline-specific processes and hold potential for improving future therapeutic strategies (Neto et al., 2016). DAZL (deleted in azoospermia-like) belongs to the DAZ family of RNA-binding proteins.

Dazl is expressed during embryonic and adult gametogenesis, playing a crucial role in germ cell determination, development and meiotic progression (Gill et al., 2011; Seligman & Page, 1998). DAZL deficiency impairs proliferation and differentiation of spermatogonial progenitors as a result of translational regulation (Du et al., 2021) and

Dazl knockout results in infertility in both sexes (Ruggiu et al., 1997). Recent findings by Mikedis et al. (2020) establish how

Dazl drives expansion and differentiation of spermatogonial progenitors. Furthermore, DAZL enhances germ cell development, promoting the translation of genes that regulate spermatogonial proliferation and differentiation (Mikedis et al., 2020). Moreover, studies have found different transcription factors expressed in a stage-specific manner during spermatogenesis such as

Tbx3 (T-Box Transcription Factor 3) (L. Zhang et al., 2010), activated in infant spermatogonia (J. Han et al., 2010), and

Utf1 (Undifferentiated Embryonic Cell Transcription Factor 1) in puberty (Guo et al., 2018). On the other hand, some transcription factors, such as cAMP response element modulator (CREM) and testis-specific CREM (CREMt), act through a testis-specific isoform generated by alternative splicing, controlling postmeiotic germ cell differentiation (Lui & Cheng, 2009) Its absence generates a knock-on effect that deactivates a large number of genes specific for sperm differentiation, triggering male infertility (MacLean & Wilkinson, 2005).

Post-transcriptional gene control regulation takes an essential role, especially at later steps of sperm differentiation when chromatin compaction induces transcriptional silencing in elongating spermatids (Yadav & Kotaja, 2014). NANOS proteins are highly conserved post-transcriptional regulators. Studies involving knockout models have highlighted the critical role of Nanos genes in germ cell development (Saga, 2010). In mice, these proteins interact with the CCR4-NOT deadenylation complex to mediate the downregulation of target mRNAs (A. Suzuki et al., 2010). The absence of NANOS2 and NANOS3 leads to a progressive depletion of primordial germ cells (PGCs) (Tsuda et al., 2003), a phenotype also observed in other RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) knockout models, such as TIAL1 and DND1 (Beck et al., 1998; Youngren et al., 2005). RBM46 is a novel RBP essential in spermatogenesis. Similar to other RBPs, RBM46 regulates mRNA translation and stability (Lv et al., 2023). Rbm46 knockout models exhibit testicular atrophy, reduced testis weight, and infertility, with seminiferous tubules lacking spermatids (Lv et al., 2023; Qian et al., 2022). RBM46 is crucial for meiosis, as its absence leads to spermatocytes arresting in early meiotic stages due to defects in chromosome synapsis and premature entry into aberrant metaphase (Lv et al., 2023; Qian et al., 2022). Additionally, RBM46 targets genes involved in chromosome segregation and the mitotic-to-meiotic transition, coordinating with RNA-processing cofactors such as YTHDC2/MEIOC to ensure proper meiotic entry (Qian et al., 2022). Due to the high requirements for the control of gene expression, it is not surprising that microRNAs have provided an important additional level to the regulation of sperm production. MiRNAs play a crucial role in spermatogenesis and testicular function, regulating the proliferation and differentiation of both Sertoli and germ cells (Walker, 2022). It has been studied how disrupting the enzymes and proteins involved in miRNA biosynthesis leads to fertility disorders in males, such as DICER, whose absence in mice spermatogonia causes increased infertility due to several deficiencies: defects in spermatogonial progression and abnormalities in sperm elongation, apoptosis in Sertoli cells, impaired spermatogenesis and sperm production, azoospermia, between others (G. J. Kim et al., 2010; Maatouk et al., 2008; Papaioannou et al., 2009). Moreover, DROSHA suppression in spermatogenic cells leads to severe germ cell depletion and low counts of elongating spermatids (Wu et al., 2012).

The balance between self-renewal and differentiation of SSCs is vital for spermatogenesis, with miRNAs regulating key factors like glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor, fibroblast growth factor, B cell CLL/lymphoma 6 member and Ets transcription variant 5 (Gdnf, Fgf, Bclb6, and Etv5), which support SSC self-renewal and maintain the SSC niche. Additionally, miRNAs have an influence in proteins such as PLZF and RA, which promote spermatogonial differentiation (Klees et al., 2024). Among the critical miRNAs involved in spermatogenesis regulation, miR-146 overexpression inhibits RA-mediated spermatogonial differentiation by targeting Med1, a coregulator of RA-receptors, and decreasing Kit proto-oncogene expression (Huszar & Payne, 2013). Similar to Dmrt1, Kit is also a differentiating marker (Guo et al., 2018). miR-221/222 maintain the undifferentiated state of spermatogonia by repressing Kit expression, thus preventing their transition to differentiated spermatogonia (Yang et al., 2013). Another crucial miRNA is miR-202-3p, regulated by GDNF and RA, and its knockout mice lead to premature SSC differentiation, highlighting its importance in SSC maintenance (J. Chen et al., 2021). These miRNAs are key to regulating the balance between SSC self-renewal and differentiation.

Male germ cells exhibit a highly diverse transcriptome, particularly in round spermatids and pachytene spermatocytes, driven by extensive transcriptional activity involving both, protein-coding and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) genes (Soumillon et al., 2013). In spermatogenesis and testicular development, some of the key studied lncRNA-coding genes are: Mrhl, which has been shown to be critical for regulating Wnt signaling, that plays a critical role in spermatogonia development (Kayyar et al., 2023); Tsx (a testis-specific X-linked gene), which is specifically expressed in pachytene spermatocytes. Tsx knockout mice exhibited decreased testicular weight and increased spermatocyte apoptosis (Anguera et al., 2011); and Dmr (Dmrt1-related gene), which plays a negative regulatory role for Dmrt1 in male sexual development(L. Zhang et al., 2010). Numerous studies have established that several lncRNAs serve as a fundamental element in regulating SSCs, maintaining SSC survival and self-renewal through protein coding genes and miRNA (Liang et al., 2014). Functional studies, as done in (Weng et al., 2017), found specific lncRNAs directly involved in the regulation of key genes essential for spermatogenesis and testis development, such as LNC_003902 targeting GATA4 (transcriptional regulator for development of the murine fetal testis) and LNC_007258 targeting NKAP (involved in maintenance and differentiation of spermatogonial stem cells in spermatogenesis). As shown in the study by Liang et al. (2019), there is a tight correlation between lncRNA Gm2044 and miR-202 in spermatogenesis, where both RNAs are upregulated in cases of non-obstructive azoospermia (NOA), a condition characterized by spermatogonial arrest. The identified lncRNA Gm2044 plays a significant role in the context of male infertility as a miR-202 host gene, directly influencing the expression of the miRNA target gene, Rbfox2, which is crucial for regulating cell proliferation and differentiation in spermatogenesis. Other important way for lncRNAs to participate in epigenetic regulation during spermatogenesis, is recruiting histone modification-related enzymes, such as histone acetylation and methylation, establishing specific gene expression patterns for different stages of development (He et al., 2021). Moreover, they can regulate chromatin activity by recruiting histone modification enzymes (L. L. Chen, 2016).

In addition, Piwi-interacting small RNAs (piRNAs) also play a central role in spermatogenesis. PiRNAs silence transposable elements (TEs) during meiosis, protecting the integrity of the germline genome (Mukherjee et al., 2014; Yadav & Kotaja, 2014).

Similarly, circular RNAs (circRNAs) are gaining attention due to their ability to act as miRNA sponges, inhibiting their function and then regulating gene expression networks (G. Zhou et al., 2022). Although their specific function in spermatogenesis is less explored, new studies suggest their involvement in NOA (Z. Zhang et al., 2022). By inhibiting miRNAs, protein binding regulation and gene transcription regulation can lead to cell cycle arrest and spermatogonia apoptosis, affecting spermatogenesis (G. Zhou et al., 2022).

In order to preserve genome integrity and also promote genetic diversity, germ cells undergo epigenetic reprogramming during development and are conditioned to attain full developmental potential upon fertilization (Saitou & Hayashi, 2021).

It is known that epigenetic regulation is indispensable, not only in general gene expression, but also in the precise control of spermatogenesis, as it affects key processes such as germ cell differentiation and fertility. N6-methyladenosine (m6A) is one of the most widespread epigenetic modifications in mRNA and plays a crucial role in gametogenesis across multiple. As it is demonstrated in Fang et al. (Fang et al., 2021b), disruptions in m6A regulation or abnormal levels of this modification are closely linked to defects in gametogenesis and embryonic development. Genome-wide methylation studies revealed how the sperm epigenome significantly differs from somatic cells due to unique DNA methylation patterns, and the presence of specialized chromatin structures required for meiosis and spermiogenesis. These differences highlight the distinct roles that DNA methylation in sperm plays beyond gene expression, influencing chromosomal organization and fertility-related processes (Trasler, 2009). The Dnmt family, including Dnmt1, Dnmt3a, Dnmt3b, and Dnmt3l, encodes enzymes that regulate DNA methylation, adding methyl groups to cytosines in CpG contexts, essential for imprinting and germline-specific methylation. In male germ cells, Dnmt3a and Dnmt3l establish de novo methylation during prenatal development, and disruptions can lead to infertility due to defective imprinting and meiotic failure (Kaneda et al., 2004; Salle et al., 2004), while Dnmt1 maintains these patterns postnatally (Salle & Trasler, 2006).

Chromatin condensates by the significant remodeling process called protamination. This crucial step replaces histones with protamines and involves different modifications and specific proteins. Aside from DNA compaction, protamination is also essential in epigenetic regulation because disrupting the role of histones in shaping the embryonic epigenetic landscape can lead to changes in gene expression and impaired fertility. This emphasizes their crucial function in epigenomic regulation during spermatogenesis (Blanco & Cocquet, 2019). Due to their importance, the regulation of protamines Prm1 and Prm2 transcription, translation and final gene expression is carefully modulated (C. Cho et al., 2001, 2003). Among key regulators, previously mentioned CREM transcription factor, Taf7l and Tarbp2 also take an important role in the regulation, as it is been previously proved how their absence led to protamines failed translation, reduced sperm count and motility and male infertility (Blanco & Cocquet, 2019; Carrell et al., 2007; H. Zhou et al., 2013). Sycp3 has also been widely studied, as it has a major role in meiotic chromosomes compactation, acting as a structural scaffold that facilitates synapsis between homologous chromosomes (Syrjänen et al., 2014). Knockout mice show a sexually dismorphic phenotype and infertility due to cell death in early meiosis (Yuan et al., 2000). New in vitro analysis suggests that meiotic chromosome compaction is driven by SYCP3’s DNA-binding and self-assembly, while in vivo, its function relies on SYCP2 and the meiotic cohesin core (Syrjänen et al., 2014).

In

Table 1 are summarized these principal elements described above and represented in the gene map of

Figure 4.

4. Temperature Regulation

Mammalian body temperature is regulated by various mechanisms that balance heat production and temperature loss. Internal organs are the primary heat generators due to their metabolic activities, which increase intra-abdominal temperature. The testes, in particular, generate significant heat during spermatogenesis. They must mitigate this heat as an increase of just 1.5–2 ºC in testicular temperature can inhibit spermatogenesis (Mieusset et al., 1993). Moreover, normal testicular function requires a substantial temperature reduction of 2–8 ºC below core body temperature (Ivell, 2007). The localization of male reproductive organs is one of nature’s strategies to prevent heat damage. The suspension of the testes outside the abdomen, in the scrotum, is a distinctive feature of homeothermic animals, except for marine mammals and elephants. The presence of the scrotum establishes an abdominal-scrotal-testicular temperature gradient that maintains the testes within a functional temperature range lower than the abdominal core (Dierauf & Gulland, 2001). In addition, several mechanisms contribute to the testicular thermoregulatory system: the pampiniform plexus surrounding the testicular artery; the tunica dartos muscle, a thin rugated fascial muscle of the scrotum that reduces scrotal volume and brings the testes closer to the warmer abdominal region; and the cremaster muscle, a thin fascial muscle of the spermatic cord that retracts the testes. In contrast, cetaceans, which have intra-abdominal testes, rely on a counter-current heat exchanger (CCHE) instead of the pampiniform plexus (Miller, 2007). The CCHE is formed by a spermatic arterial plexus juxtaposed to the lumbo-caudal venous plexus, which carries blood from superficial veins of the dorsal fin and flukes cooled by external water. This mechanism cools the spermatic arterial plexus that supplies the testes (Rommel et al., 1992; Scholander & Schevill, 1955). Cryptorchidism, a condition where the testes fail to descend into the scrotum, exemplifies the detrimental effects of elevated testicular temperatures. Studies have demonstrated the negative impact of increased temperature on spermatogenesis in animals with undescended testes or thermal stress induced in the laboratory (Pérez-Crespo et al., 2008). High temperatures impair regulatory mechanisms, leading to the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Ziaeipour et al., 2021). This results in oxidative stress in germ cells, increased DNA damage, apoptosis, and autophagy (Rockett et al., 2001; J. Yin et al., 2017), as well as alterations in gene expression. These changes reduce testicular function and sperm quality, contributing to male infertility (Kesari et al., 2018; Morrell, 2020).

Increased apoptosis due to heat stress leads to decreased testicular weight, germ cell loss, and low sperm concentration (Gao et al., 2020; J N Chen 1 L H Ji 1, 2020; Lue et al., 2000; Qin et al., 2019). Even worse, after heat stress, a high amount of germ cells can carry out the complete development into abnormal morphological spermatozoa with damaged DNA avoiding apoptosis, which leads in a reduction of viability or motility(Banks et al., 2005; Mahdivand et al., 2021; Y. Yin et al., 1997). In IVF experiments, heat stress has been linked to reduced sperm binding to the zona pellucida and DNA fragmentation, observed by significant declines in COMET assay parameters such as tail length and tail moment(de Dios Hourcade et al., 2008). Mitochondrial dysfunction caused by heat stress, including reduced ATP synthesis, decreased membrane potential, and lower mitochondrial protein content, further impairs sperm motility (Gong et al., 2017). As heat stress increases oxidative stress, this affects Na+/K+-ATPase activity that reduces sperm flagellum movement, which explains abnormal motility and fertility reduction (Thundathil et al., 2012). The phosphorylation state of glycogen synthase kinase 3α (GSK-3α), mediated by Ser21 phosphorylation, is associated with sperm motility in various species, including humans(Somanath et al., 2004), bovines (Vijayaraghavan et al., 2000), and pigs (Gong et al., 2017). At this point, Gong et al. (2017) demonstrated that heat stress reduced levels of GSK-3α phosphorylation in board sperm affecting its motility.

Heat stress also affects DNA integrity and gene expression. The synaptonemal complex, essential for homologous chromosome pairing during meiosis, is disrupted by elevated temperatures, leading to recombination failures that become DNA fragmentation and unpaired chromosomes or aneuploidy, damaging DNA integrity (Houston et al., 2018; Pérez-Crespo et al., 2008). On one hand, heat stress induces mRNA and protein degradation and downregulates genes related to meiosis and DNA synthesis (B. Kim et al., 2013). On the other hand, heat stress activates some genes related to defense, regulation and DNA damage repair, as well as heat shock proteins (HSPs). Heat shock proteins are essential for spermatogenesis to protect proteins not only against heat but radiation and chemical exposure. HSP70 are highly conserved proteins across phyla, from archaebacterial to plants and animals. There are two members of the HSP70 family expressed specifically during spermatogenesis HSP70-2 and HSC70t. HSP70-2 protein is present in spermatocyte during meiotic phase of spermatogenesis (Allen et al., 1988), while HSC70t is synthesized in postmeiotic spermatids (Zakeri & Wolgemuth, 1987). HSP70-2 is associated with synaptonemal complex, and it is necessary for the formation of Cdk1cyclin B1 heterodimer. Male mice deficient in hsp70-2 are infertile due to arrested germ cell meiosis in prophase I, and increased apoptosis in spermatocyte stage.

But the effect of an increased temperature in the testicles not only affects spermatogenesis and male fertility. Moreover, changes in gamete during spermatogenesis caused by heat stress that don’t compromise viability but biology may also affect embryo development. Different studies demonstrated a reduction of cleavage rate (de Dios Hourcade et al., 2008), as well as the preimplantational development of embryos produced in vivo (Zhu & Setchell, 2004) and in vitro (Jannes et al., 1998; Setchell et al., 1998; Zhu & Setchell, 2004). Male mice subjected to heat stress sire fewer post-implantation embryos and fetuses with reduced body weights, not affecting to resorptions (de Dios Hourcade et al., 2008; Jannes et al., 1998; Setchell et al., 1998; Yaeram et al., 2006). In sheep, heat stress increases the proportion of degenerated embryos (Mieusset et al., 1991). Paternal heat stress also alters protein profiles in preimplantation embryos, indicating its impact on embryonic development (Zhu & Maddocks, 2005). Additionally, scrotal heat stress can distort offspring sex ratios in mice, when males are mated with females on the same day as scrotal heat treatment, reducing the proportion of male offspring without affecting the ratio of X- and Y-chromosome-bearing spermatozoa(Pérez-Crespo et al., 2008) although it has been seen that the altered temperature environment could differently affect the functionality of spermatozoa carrying X or Y chromosomes for a short period, more than the spermatogenesis itself (Pérez-Crespo et al., 2008).

In human, the most common origin of heat stress is the modern lifestyle that impairs proper testicular thermoregulation, such as regular use of tight clothes that reduces airflow of genital area (Jensen et al., 1996; Laven ’ et al., 1988; Lynch et al., 1986), sedentary behavior or seated position during long periods (Bujan et al., 2000; Henrik et al., 2002), obesity (Kort et al., 2006), or the use of thermal treatments (Garolla et al., 2013; Shefi et al., 2007).

In mammals, pathological heat stress is produced by cryptorchidism (Mieusset et al., 1987), varicocele when abnormal dilatation of the veins of the pampiniform plexus take place (Naughton et al., 2001), or febrile episodes (Sergerie et al., 2007).

But also, the Global Warming is a matter of concern that affects both animals and human infertility. It is well documented not only the increase in the environmental temperature since the beginning of the industrial era, but also the increase in the frequencies of heat waves, and the relationship with an increased mortality rates due to heatstroke, dehydration, or hyperthermia. Different researches have studied how the climate change affects fertility through the association between the season environmental temperature and sperm parameters, highlighting a likely detrimental effect of extreme temperatures (Kabukçu et al., 2020; Pakmanesh et al., 2024; Yogev et al., 2012; Y. Zhou et al., 2020).

5. Cellular Mechanisms of Proliferation and Differentiation of Germ Cells

In mammals, the formation of testes begins with the segregation of seminiferous cord bundles from the surface epithelium, which are subsequently divided into individual cords by mesenchyme (

Figure 5A). At this stage, the primordial germ cells (PGCs) are named gonocytes, and few days after birth they undergo a transformation into SSCs. In the testis of adult mice, SSCs are identified as As spermatogonia (SA in

Figure 1), where “s” stands for single, reflecting their undivided state and lack of intercellular bridges. Whether this dual pathway from gonocytes to spermatogonia is mouse-specific or a general from mammals remains uncertain, although considering the parallel with Drosophila, could be broadly used the direct development from PGCs to spermatogonia (White-Cooper & Bausek, 2010).

Figure 5.

A) Mouse testis development. B) Cell lineages of developing testis: Peritubular Myoid Cells (PTM), Sertoli cells, Germ Cells and Leydig cells. C) Seminiferous epithelial cycle map of mouse spermatogenesis: The columns show different stages of the seminiferous epithelial cycle (marked with Roman numerals I–XII). The progress of germ cell differentiation, is represented from left to right, and from bottom to top. Aund, undifferentiated spermatogonia; A1–4, type A1–A4 spermatogonia; In, intermediate spermatogonia; B, type B spermatogonia; Pl, preleptotene spermatocytes; L, leptotene spermatocytes; Z, zygotene spermatocytes; P, pachytene spermatocytes; D, diplotene spermatocytes; 2°, secondary spermatocytes plus meiotic divisions. Arabic numerals 1-16 refer to steps of post-meiotic spermatid maturation (spermiogenesis). Reproduced with permission of: A) (Yildirim et al., 2020a); B) (Pelosi & Koopman, 2017a); C) from Mäkelä et al., 2020, reproduced with permission.

Figure 5.

A) Mouse testis development. B) Cell lineages of developing testis: Peritubular Myoid Cells (PTM), Sertoli cells, Germ Cells and Leydig cells. C) Seminiferous epithelial cycle map of mouse spermatogenesis: The columns show different stages of the seminiferous epithelial cycle (marked with Roman numerals I–XII). The progress of germ cell differentiation, is represented from left to right, and from bottom to top. Aund, undifferentiated spermatogonia; A1–4, type A1–A4 spermatogonia; In, intermediate spermatogonia; B, type B spermatogonia; Pl, preleptotene spermatocytes; L, leptotene spermatocytes; Z, zygotene spermatocytes; P, pachytene spermatocytes; D, diplotene spermatocytes; 2°, secondary spermatocytes plus meiotic divisions. Arabic numerals 1-16 refer to steps of post-meiotic spermatid maturation (spermiogenesis). Reproduced with permission of: A) (Yildirim et al., 2020a); B) (Pelosi & Koopman, 2017a); C) from Mäkelä et al., 2020, reproduced with permission.

The “seminiferous epithelium cycle” was defined in rats by Leblond and Clermont in 1952 by considering the division of the epithelium into separate stages, according to the cellular associations observed in each tubular cross-section. In rats, the seminiferous epithelium cycle was divided into 14 stages (I to XIV) and spermiogenesis split into additional 19 steps (1 to 19) (Hess & De França, 2008; Leblond & Clermont, 1952). In mouse, the cycle is divided into 16 stages (I to XVI) as is showed in

Figure 5C. The seminiferous epithelium cycle and spermatogenesis presents a different duration in each species (

Table 2).

This spermatogenesis occurs within the seminiferous tubules, the functional unit of the mammalian testis, being regulated by several endocrine factors, such as testosterone, FSH, LH and estrogens. These seminiferous tubules are composed by Sertoli and germ cells (Mruk & Cheng, 2015). It begins at puberty after a long preparatory period of the called prespermatogenesis, present in the fetus and in the infant (

Figure 5B) (Holstein et al., 2003).

5.1. Phases of Spermatogenesis

Mammalian spermatogenesis is divided into three general phases: mitotic division of SSC, meiosis of the spermatocyte and spermiogenesis. The proliferative phase, known as Mitotic phase, involves the mitotic division of SSC located along the basal membrane of the seminiferous tubules. These rounds of mitotic divisions produce primary spermatocytes driving to the expansion of the spermatogonial population before entering the differentiation stage, ensuring a continuous supply of germ cells throughout the reproductive life of the male. During differentiation, the primary spermatocytes undergo meiosis to reduce their chromosome number by half, transitioning into haploid cells. The process begins with meiosis I, where a primary spermatocyte (diploid, 2n) divides to form two secondary spermatocytes (haploid, n). Each secondary spermatocyte then undergoes meiosis II, resulting in four haploid spermatids. Throughout meiosis, chromosomal recombination and crossover events ensure genetic diversity among the sperm cells. The final stage, spermiogenesis, involves the morphological and biochemical transformation of round spermatids into elongated spermatozoa (

Figure 1).

5.1.1. Mitotic Phase

In the proliferative stage or spermatocytogenesis, the SSC located adjacent to the basement membrane, produces type A and B differentiated spermatogonia. Therefore, undifferentiated type A spermatogonia are amplified and self-renewed by mitosis to replenish the stem cells. A series of mitotic cell divisions with incomplete cytokinesis (since daughter cells stay interconnected by cytoplasmic bridges) first produce a pair of spermatogonial cells, and then differentiate into 4-16 or even 32 aligned A spermatogonias, which migrate from base compartment to the luminal compartment of the seminiferous tubules. Aligned A spermatogonia transition is regulated by at least one extrinsic factor (retinoic acid) and multiple intrinsic factors. A1 spermatogonia undergo subsequently six mitoses, generating A2, A3, A4, intermediate (In) and B spermatogonia, being all of them differentiated spermatogonia. The mitosis in mammalian gametogenesis is controlled by several components: the oscillation activity of Cyclin/CDKs, the activity of Anaphase promoting Complex/Cyclosome (APC/C), the components at the mitotic spindle such as small kinetochore-associated protein (SKAP), DNA repair-associated genes, several signaling molecules, miRNAs, etc (Chocu et al., 2012; De Kretser et al., 1998; Griswold, 2016; J. H. Wang et al., 2019).

5.1.2. Meiosis

During meiosis, spermatocytes reduce the chromosome copy number from diploid to haploid round spermatids through two consecutive divisions. Interestingly, meiotic cell division occurs in stage XII in mice, but in rats it is not confined only in a single stage. When B spermatogonia divides by mitosis forming two preleptotene spermatocytes, it represents the meiotic entry, prior to chromosome segregation. They undergo meiotic prophase I, which consists in the reorganization of nuclear architecture and chromosome structure, leading to the formation of bivalent chromosomes through the formation of synaptonemal complex (SC) or related structures to perform meiotic recombination. Primary spermatocytes go through the preleptotene stage, when DNA replication occurs, and later, undergo the leptotene, zygotene, pachytene and diplotene stages of the prophase I. In mice and humans, the main components of prophase I are conserved, but the organization of axial element (AE) and SC displays sexually different properties, since prophase I of meiosis in males presents pachytene checkpoint and meiotic sex chromosomal inactivation (MSCI). MSCI are accompanied by significant changes in gene expression and modifications to the epigenetic landscape. It occurs when the transcription of most genes on the sex chromosomes is suppressed during meiosis due to the lack of synapsis between the X and Y chromosomes outside the pseudoautosomal regions, localizing the sexual chromosomes in the sex body or XY body. After meiosis, sex chromosome inactivation is predominantly preserved in round spermatids within a heterochromatic structure called postmeiotic sex chromatin (PMSC). However, certain genes bypass this silencing for specific activation. During meiotic prophase CDKs, cyclins and non-cyclin CDK activators, are important effectors. That includes among many others: cyclin A1, Cdk2 and Cdk4. Also, meiosis initiator (MEIOSIN) and STRA8 regulate gene activity by binding to transcription start sites (TSSs) of a wide array of genes involved in meiosis and other spermatogenic processes; many target genes of MEIOSIN and STRA8 are associated with meiotic prophase processes such as chromosome dynamics and recombination. Then, the first meiotic division produces secondary spermatocytes, which quickly proceed through the second meiotic division, resulting in the formation of haploid round spermatids. Mistakes in these crucial processes can result in aneuploidy and genetic instability, making it critical for them to be regulated by multiple surveillance mechanisms (Alavattam et al., 2022; C. Han, 2024; Hess & De França, 2008; Ishiguro, 2024; Lim & Kaldis, 2013; Turner, 2015).

5.1.3. Testis Cells and Seminiferous Tubule Structure

Within the seminiferous tubule, Sertoli cells, which are polarized epithelial cells, generate the tight BTB, to divide the seminiferous epithelium into basal and luminal compartments (Ogawa et al., 2005) (

Figure 1). The BTB structure is created by tight junctions, ectoplasmic specializations, desmosomes and gap junctions that are present between Sertoli cells, but not between Sertoli and germ cells or between germ cells in vivo (Mruk & Cheng, 2015). This barrier is vital as it protects sperm production from autoimmune reactions (L. Li et al., 2024a). Sertoli cells are the major contributions to the stem cell niche, although there are also contributing peritubular myoid (contractile cells surrounding seminiferous tubules playing a crucial role in propelling spermatozoa from the seminiferous tubules into the epididymis) and Leydig cells (located in the interstitial space and secreting testosterone in the presence of LH) (

Figure 1). Also, testosterone is needed for the maintenance of the BTB, spermatogenesis, and fertility, and it promotes both Sertoli-germ cell junction assembly and disassembly (Mruk & Cheng, 2015; White-Cooper & Bausek, 2010). During cellular transformation, germ cells migrate from the basement membrane to the tubular lumen of seminiferous tubules (Zakariah et al., 2022). This transport during the epithelial cycle is possible due to the coordination between the microtubule (MT) and F-actin-based cytoskeletons in Sertoli cells and at the Sertoli-germ cell interphase. Studies in mammalian cells displayed that MT serve as tracks for carrying several cargos (cellular organelles including proteins, mRNA complexes, endosomes, mitochondria and cell nuclei) requiring the motor proteins as dyneins in the MT-minus-end-directed transport and others as kinesin which is responsible for the MT-plus-end-directed transports of cellular organelles. Motor proteins are probably recruited by developing spermatids in order to move up or down the seminiferous epithelium at different stages of the epithelial cycle. Sometimes dyneins and kinesins are attached simultaneously to the same cargo, and there are present several protein kinases, phosphatases and Rab GTPases regulating the activity of motor proteins. In this scenario are also involved the polarized F-actin microfilaments which also serve as the tracks to support cellular transport serving as a guide for MT growth (Rajender et al., 2010; Wen et al., 2016).

5.1.4. Spermiogenesis

The spermiogenesis corresponds to the post-meiotic phase or cytodifferentiation, in which haploid round spermatids are going to differentiate into spermatozoa by displaying morphological transformation, including the formation of the flagellum and acrosome (with the contribution of Golgi apparatus), nuclear condensation being histones replaced by protamines and cytoplasmic shedding (C. Han, 2024; Hess & De França, 2008; J. H. Wang et al., 2019). When spermatogenesis is finished, is followed by spermiation when immotile spermatozoa are released from testis, therefore still need to mature throughout the epididymis, followed by capacitation and acrosome reaction in the female reproductive tract (Freitas et al., 2017).

During this late stage, intercellular bridges gain some importance since round spermatids are haploid and some individual cells would lack single copy genes, such as those present in sex chromosomes. Therefore, haploid spermatids could behave as functionally diploid by sharing gene products across intercellular bridges. However, the presence of multinucleated spermatids is a hallmark of defective spermiogenesis. Regarding the development of the acrosome, it starts in round spermatids shortly after meiosis, formed by the trafficking of the Golgi-derived vesicles to the nuclear membrane. Then, it gradually extends across the nuclear surface, eventually covering up to half of the anterior portion of the sperm head. For instance, the failure in acrosome formation is linked to the known condition globozoospermia. Moreover, the species-specific sperm head shape is established after the round spermatid nucleus shifts to one side of the cell and gradually transitions from a spherical shape as nuclear condensation and sperm head shaping begin. Abnormalities in head morphology could be due to problems associated with the formation of the manchette (microtubule-based structure vital for sperm head shaping) or to the chromatin compaction and protamination. Besides, early round spermatids start the assembly to the central microtubule-based component of the flagella, known as the axoneme, which is structured with a central pair of microtubules encircled by nine outer doublet microtubules, forming the characteristic “9+2” arrangement. Dynein motors attached to the outer doublets create the forces necessary for antiparallel sliding, which drives the flagellum’s wave-like motion. After the initiation of axoneme formation in early spermiogenesis, secondary structures required for flagella function are assembled during the elongation phase of spermiogenesis. Defects in all these complex processes could lead to issues in flagella assembly and in sperm motility. In the elongation phase of spermiogenesis, the round spermatid nucleus and acrosome becomes polarized to one side of the cell. At this stage, the spermatid connects with a specialized type of adhesion junction known as the ectoplasmic specialization. And defects in positioning of sperm heads inside the epithelium are probably due to defects in either the ES and/or its ability to be translocated along Sertoli cell microtubules. The last step of spermiogenesis is spermiation, being the process, in which elongated spermatids undergo final remodeling and are released from the seminiferous epithelium into the lumen of the tubule, preparing for their transport to the epididymis (O’Donnell & O’Bryan, 2014; Teves et al., 2020). It has been described that sperm had a greater mid-piece volume from polygamous primate species than sperm of a monogamous species, where sperm competition would be higher (Anderson MJ and Dixon AF, 2002).

5.1.5. Mechanisms for Maintaining DNA Integrity in Spermatozoa

To address DNA damage in spermatozoa and preserve genomic integrity, five repair mechanisms have evolved: nucleotide excision repair, base excision repair, mismatch repair, double-strand break repair, and post-replication repair (Gunes et al., 2015). The ubiquitin proteasome system is important in every step of spermatogenesis, since deubuquitinating enzymes might be involved in histone removal and protein turnover during meiosis (Suresh et al., 2015). Several studies on cultured mammalian cells indicated that the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway plays a crucial role in several cellular processes, including DNA repair, protein translocation, circadian rhythm regulation, protein folding, transcription, and apoptosis (Gunes et al., 2015).

5.1.6. Importance of Apoptosis in Spermatogenesis

Apoptosis plays a crucial role in ensuring the proper function and development of male germ cells, from the initial stages of gonadal differentiation in the early embryo to the process of fertilization (Bejarano et al., 2018). That removal of excess germ cells from testicular tissue is crucial in order to control the number of spermatogenic cells that are supported and nourished by the Sertoli cells, since it has been described that up to 75% of germ cells are lost during development of spermatogonia, ensuring the elimination of those which carry DNA mutations or genes with defects (Zakariah et al., 2022). Mitochondrion is a key intracellular organelle involved in the regulation of apoptosis, which is translationally active during spermatogenesis. This organelle is participating in multiple roles, including ATP production, generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), calcium signaling, and apoptosis. Mitochondrial defects are associated with various physiological dysfunctions, including infertility. In the mid-piece of mature mammalian spermatozoa there are 72 to 80 mitochondria (Rajender et al., 2010). While mitochondrial proteins play a major role in the activation and termination of intrinsic apoptosis in response to oxidative stress, sperm cell extrinsic apoptosis is mediated by Fas protein receptors (Gunes et al., 2015). Apoptotic makers possibly related to male infertility would include: the activation of phosphatidylserine mark by caspases (early apoptotic marker), DNA fragmentation (late-stage apoptosis), and low motile sperm, that reflects high presence of apoptosis markers compared to the highly motile sperm cells (Gunes et al., 2015).

6. New Discoveries and Future Perspectives

6.1. Advancements in the Study of Male Hormonal Reproductive Disorders

Fertility issues affect to 9% of couples worldwide and 50% come from the male side, according to The World Health Organization (WHO). Several factors are involved in male infertility, ranging from genetic mutations to lifestyle habits. Impairments at a hormonal level during the cycle of spermatogenesis will result in failure to give rise to suitable spermatozoon. Therefore, fertility in the male side will be compromised. During puberty, the adequate spermatogenesis and sperm production is brought about by the role of gonadotropins that lies mainly in generating the cohort of Sertoli, Leydig and germ cells for adult life. Consequently, if hormone deprivation occurs during this stage of life, scrotal descent and testis development will be impaired, whereas in the adult, only the germ cells composition in somatic cells will be functionally hindered, mainly in Sertoli cells (Ramaswamy & Weinbauer, 2014).

The most prevalent male genitalia congenital disorder is cryptorchidism. Involved in this disease is INSL3, which participates in the coordination of the descent of the testis during foetal development. It has been reported (Nef & Parada, 1999) that knockout male mice for Insl3, although viable, show bilateral cryptorchidism caused by abnormalities in the development of the gubernaculum. This structure is a foetal ligament that is attached to the scrotum and caudal epididymis and follows atrophy after birth (Acién et al., 2011). This knockout model has been reported to be especially useful for the study of oestrous cycle deregulation in female homozygotes (Nef & Parada, 1999).

Regarding HPG axis impairments, it has been described the role of kisspeptin in the HPG axis and highlighted its potential use as a diagnostic tool and treatment for some reproductive disorders, such as hypogonadism, central precocious puberty (CPP) and female infertility. Kisspeptin acts as a critical factor regulating GnRH release. In the male side, it is also involved in reproductive behaviour, Leydig cells regulation, spermatogenesis and sperm functions (Xie et al., 2022). Ishikawa et al., 2018 and Matsui et al., 2012 studies in rats have elucidated a great anti-tumour effect in the kisspeptin analogue, TAK-448, that strongly inhibits HPG axis in a greater extent than GnRH analogues. Therefore, these findings constitute a potential and novel approach in androgen deprivation therapies, indicated for sex-hormone dependent malignancies, as prostate cancer.

Many challenges are encountered in clinical practice regarding reproductive disorders. However, current knowledge on endocrine dynamics and future advancements will shed light on a better understanding of hormone-dependent reproductive malignancies.

6.2. Insights in Male Contraception

Male hormonal contraception poses an effective and reversible alternative to female contraception methods, allowing men to share the burden of this issue with their female partners. Therefore, it has potential to positively and significantly have an impact in society.

Exogenous administration of suppressing hormones for both LH and FSH leads to low T levels in the testis resulting in a significant decrease in sperm count in the ejaculate. Some of these suppressing hormones that can be used are T alone or in combination with progestin or GnRH analogues (

Figure 2)., and their effect is reversible (Nieschlag, 2010; C. Wang et al., 2024). Although these options are effective and prevent fertility in most men, they are not yet available nor approved. These treatments entail some adverse effects regarding sexual drive, acne and serum cholesterol. Moreover, it is uncertain which side effects would be faced after long-term high doses of T regarding some cancers, such as prostate cancer, and some cardiovascular diseases.

Additionally, optimization of dosing and delivery are required to overcome limitations and reduce side effects of these contraceptives. Some of these limitations are the variability in suppression rates regarding different populations, long duration of the treatment (6-8 weeks due to the 72-day process of spermatogenesis), risk of pregnancy due to sperm rebound in some men and lack of funding from the pharmaceutical industry. To overcome some of these hurdles, novel androgens with dual androgen-progestin action, such as dimethandrolone undecanoate and 11-ß-methyl-19-nortestosterone-17-ß-dodecyl carbonate, have been reported as suitable candidates to be developed as oral pills or long-acting injections. Other promising methods of delivery under research are transdermal gels and implants, providing the user with a more independent and user-friendly alternative (Thirumalai & Page, 2022; C. Wang & Swerdloff, 2010).

Aside from male contraception, the mechanism of bypassing the action of GnRH by administering exogenous T, progestins or GnRH analogues could represent a valuable mechanism to be studied as a therapy for some diseases in which the HPG axis is impaired in males, for example, in congenital hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism (CHH), causing delayed puberty. In addition, several scientific studies have proposed heat stress as a male contraception method (Kandeel & Swerdloff, 1988; Liu, 2010; R. H. Wang et al., 2007) through germ cell apoptosis, inducing reversible oligospermia o azoospermia. Nevertheless, Male Thermal Contraceptive methods (MTC) include generation of artificial cryptorchidism or heat shock by ultrasound, or local hot water applied to the scrotum. An experiment with voluntary patients of normal semen parameters was performed, to analyze the inhibition of spermatogenesis by artificial cryptorchidism, as a contraceptive method in human, during 12 months (Mieusset et al., 1985). Most of the parameters analyzed dropped significantly from the first month, reaching the lowest values from the sixth month on. Ultrasound has been used as a reversible suppressant of spermatogenesis, in different species since it produces a double effect, heat and mechanic, affecting sperm, spermatids, and primary and secondary spermatocytes but Sertoli cells and stem cells, with any kind of genetic damage (Fahim et al., 1977).

6.3. Advancements in the Gene Regulation of Spermatogenesis

The integration of omics technologies and tools is transforming our understanding of genetic regulation in spermatogenesis. Recent studies have identified previously uncharacterized genes as essential for meiosis, such as Zcwpw1, based on high-resolution proteomic dynamics and new machine learning technologies to predict key meiosis proteins (Fang et al., 2021). These new predictions require validation, paving the way for further investigations and characterizations of the genes and proteins involved. Single-cell technologies have developed over the years to consistently quantify gene expression and to enable integrated epigenome, proteome and transcriptome profiling. Green et al. (2018) used scRNA-seq to study transcriptome-wide dynamics during SPG differentiation focusing on selected genes known to be involved in regulation, such as Sohlhs, Dmrts, Kit and Stra8. Already described marker genes can be targeted to understand their expression. Additionally, new spatial transcriptomics approaches are complementing scRNA-seq by adding spatial context, enabling the study of organized gene expression data within tissue architecture and cellular interactions (X. Zhang et al., 2023). Through scRNA spatial transcriptomics, marker genes can also be targeted in order to find spatial expression patterns. Piwil4 (piwi-like RNA-mediated gene silencing 4) and Etv5 have been found expressed in different human spermatogonial developing states (Guo et al., 2018).

As multi-omics knowledge continues to increase, new gene candidates could be used as biomarkers for infertility diagnostic. Rbm46 is an example, as it has been recently found to be a key element in spermatogenesis regulation in order to properly exit mitosis during meiosis (Dai et al., 2021). Its downregulation in azoospermic patients suggests that Rbm46 could be a key factor in male infertility. Studies in zebrafish models have also revealed that depletion of RBM46 disrupts essential genes such as Dazl, Nanos3, and Sycp3, further confirming its importance in germ cell development and meiosis (Dai et al., 2021). These findings make Rbm46 a promising candidate for future research into male infertility, opening the door for investigations in other animal models like mice and ultimately paving the way for clinical applications in humans. miRNA, lncRNA and circRNAs are also novel gene candidates, their expression profiles in testicular tissues have been increasingly studied and found to be differentially expressed in OA and NOA patients (Anguera et al., 2011; Klees et al., 2024; Weng et al., 2017). This significant differential expression in patients with NOA, make them another potentially non-invasive therapeutic, molecular biomarker and drug target. Using advancements of gene editing technologies, such as tools like CRISPR/Cas9, has enabled the manipulation of specific genes to investigate their function, paving the way for gene therapies to treat male infertility. The broad knock-out approach has evolved into more targeted, specific knockouts, enabling studies to gain a more detailed and comprehensive understanding of spermatogenesis (H. Q. Wang et al., 2022). That is why, clinically, non-coding RNAs are emerging as promising biomarkers for diagnosing reproductive disorders and as targets for innovative treatments (Klees et al., 2024; Robles et al., 2019). Dysfunctions in spermatogenesis, which are responsible for male infertility, often have a genetic basis, making CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing a promising therapeutic approach. Previously mentioned miR-202, a target microRNA for male infertility because of its crucial role in SSC regulation, was deleted using CRISPR/Cas9 for additional functional analysis (X. Li et al., 2019). Gene therapy and new technologies can be used to treat male infertility caused by mutations in key genes for sperm development, or to correct epigenetic imbalances. As an example, male infertility has also been restored in mice using CRISPR/Cas9, targeting mutated marker genes that lead to impaired spermatogenesis and, consequently, infertility, such as Kit (X. Li et al., 2019) and Tex11 (Y. H. Wang et al., 2021).

As seen in Liang et al., (2019) a deeper understanding of the molecular pathways regulating spermatogenesis can lead to significant advancements in potential therapeutic approaches for male infertility. A promising avenue for future research is the clinical application of identified spermatogenesis regulators. The direct involvement of Dazl (Seligman & Page, 1998), Plzf (Sharma et al., 2018), and miR-202 (J. Chen et al., 2017) in infertility and spermatogenesis dysfunctions has been well-documented in the literature, yet limited research in infertile patients has been conducted due to ethical concerns, technical challenges, and the complexity of accurate spermatogenesis-related disorders models in clinical settings. However, advances in gene editing technologies, such as CRISPR/Cas9, combined with in vitro models and personalized medicine, offer promising avenues to overcome these challenges and enable further exploration of spermatogenesis in human patients. This could provide insights into new therapeutic strategies where, in the future, the development of RNA-based therapies and the combination of genetic and epigenetic approaches have the potential to redefine male infertility treatment, allowing for more targeted and personalized interventions.

6.4. Advancements in In Vitro Spermatogenesis

Testis is a complex organ where different cells interact to achieve healthy sperm production. Several factors can compromise this process, leading to fertility failure. Efforts to study it in vitro have been ongoing for decades, driven by the need to better understand male infertility, reproductive toxicology, and potential regenerative medicine applications.

Early studies used 2D monolayer cultures to isolate testicular cells such as spermatogonia, Sertoli cells, and Leydig cells. While these approaches provided valuable insights into individual cell behaviors, they lacked the microenvironment and spatial organization necessary for full spermatogenesis. The main limits of this culture approach are ineffective in mimicking the seminiferous tubule structure and the inability to maintain germ cell differentiation beyond a certain stage (Kulibin & Malolina, 2023). Alternatively, in vitro culture of testicular tissue slices or fragments has been a significant advancement. These explants retain the architecture of the seminiferous tubules, enabling better cellular interactions. A 2011 study by Sato et al. demonstrated complete in vitro spermatogenesis in neonatal mouse testicular tissue cultured with optimized conditions, producing functional sperm capable of fertilization (Sato et al., 2011). The limitation of this technique is the limited long-term viability of tissue cultures and the difficulty in translating protocols to adult human testicular tissue. At this point, organoids offer a promising solution by providing an in vitro model that mimics in vivo processes (Stopel et al., 2024). Testicular organoids are 3D cell culture systems that self-assemble from testicular cells, creating a microenvironment more representative of in vivo conditions. They can mimic the seminiferous tubule structure and facilitate cellular interactions and signaling pathways critical for germ cell development. With this technique, partial spermatogenesis in mouse organoids has been achieved, supporting further germ cell differentiation by the introduction of growth factors like FSH, testosterone, and retinoic acid. The main problem that presents is, on one hand, the difficulty in achieving complete meiosis and the production of fully mature sperm and on the other hand, the variability in organoid formation and functionality. Organoid techniques rely on the knowledge of Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and embryonic stem cells (ESCs) that have been differentiated into primordial germ cell-like cells (PGCLCs) and even spermatogonial-like cells. In 2016, a study by Q. Zhou et al. (2016) achieved complete in vitro spermatogenesis from PGCLCs derived from mouse ESCs. Moreover, microfluidic platforms are a new technique that recreates dynamic environments with precise control over nutrient flow, temperature, and hormone delivery. This allows to improve germ cell survival and differentiation and model testicular toxicology with high reproducibility.

The combination of these techniques amplifies the options to design a successful protocol to study this complex process.

So, research in this area is trying to develop robust and reproducible protocols for large-scale in vitro spermatogenesis, achieving functional sperm production from germ cells as the ultimate goal. Combining in vitro testicular systems with ovarian organoids or other reproductive models will allow an advancement in the knowledge of broader aspects of fertility. In addition, it could be useful for clinical applications such as the generation of sperm for individuals with non-obstructive azoospermia or for preserving genetic material of endangered species.

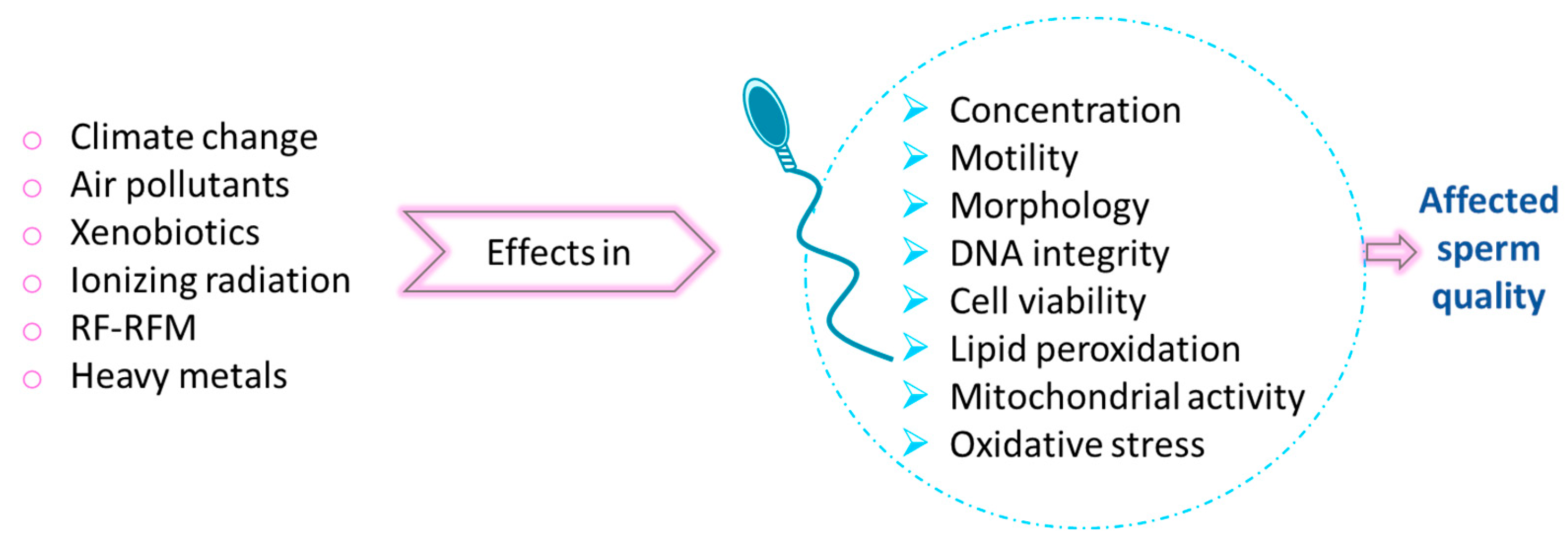

6.5. Environmental Threats for Male Fertility

Between 1970 and 2020, fertility rates declined across all countries globally. Although the world’s population continues to grow, the rate of this growth is decreasing. However, this situation seems to be different depending on each country, but still across men from all continents, the average sperm concentration dropped by 51.6% between 1973 and 2018; being around 7% of all men affected by male infertility all over the world. The widespread presence of environmental stressors has become a significant contributor to the increasing incidence of male infertility and a reduction of sperm quality worldwide (N. Kumar & Singh, 2022; Wdowiak et al., 2024).

The harmful effect of environmental factors on male fertility (

Figure 6) could be explained by the effect in sperm of ROS, the impact of epigenetics and genetic susceptibility. One of these factors are xenobiotics, such as dioxins and furans, from transport industry among others; Bisphenol A (BPA) present in manufactured plastics, cosmetics and as antioxidant in food industry; phthalates, to give flexibility to plastic; micropollutants and nanoparticles from nanotechnologies (such as silver, copper oxide, zinc oxide, cobalt, titanium oxide, nickel oxide) that ends in aquatic environment, including pharmaceuticals and sex hormones; alcohol; pesticides… Interestingly, xenobiotics behave as endocrine disruptors, interfering in vertebrate species with both genomic and non-genomic pathways (Gallo et al., 2020). Other factors are: air pollution (sulfur oxides, nitrogen oxides, carbon oxides, dust, soot and ashes), heavy metals (such as lead, cadmium and mercury), ionizing radiation or occupational dust (Gallo et al., 2020; N. Kumar & Singh, 2022; Wdowiak et al., 2024). Lifestyle factors (as smoking, alcohol consumption and BMI), health conditions (such as varicocele, impaired glucose tolerance, infections and some malignancies) and advanced paternal age, shown an effect in sperm DNA fragmentation (Szabó et al., 2023). However, the quality of semen could be improved by following a healthy diet rich in plant-based foods, as mediterranean, vegetarian or a dietary approach to stop hypertension (DASH) (Nassan et al., 2018; Salas-Huetos et al., 2019), although more research in the field is needed.

Several studies pointed out that prolonged uses and exposure to mobile phone (Agarwal et al., 2011) and Wi-Fi (Pall, 2018), and therefore to RF-EMR (Radio Frequency Electromagnetic Radiation), which is a non-ionizing radiation could have adverse effects on human health, including spermatogenesis (Agarwal et al., 2011). The spermatogenesis issues could be due to thermal stress increasing the testicular temperature and due to an oxidative stress increasing ROS and therefore DNA damage. Both of them would lead to: a decreased sperm counts and maturation, a reduced epididymal weight, a reduction of motility and alterations in morphology and cell viability (Sciorio et al., 2022).

Furthermore, reproduction is also affected by the two direct consequences of climate change due to the rise in greenhouse gas emission: global warming (increase in global temperature) and ocean acidification (Gallo et al., 2020). Temperature increase exerts a negative effect in sperm fitness as it has been previously described in this work, as well as ocean acidification shows a negative impact on reproduction of the majority of marine species, since they are external fertilisers and release sperm and eggs into the water (Campbell et al., 2016).

Therefore, the exposure to adverse environmental factors can lead to reduced semen quality in terms of decreased sperm concentration, impaired motility, viability, and normal morphology, as well as increased sperm DNA fragmentation, mitochondrial dysfunction and membrane integrity, all contributing to male infertility (N. Kumar & Singh, 2022).

7. Conclusions

The complex process of spermatogenesis depends on the proper functioning of multiple events such as hormonal influence, adequate genetic and epigenetic regulation, and correct balance between cellular proliferation and differentiation. All of these processes must occur under the appropriate temperature and environmental conditions. Lifestyle, climatic change, and environmental contamination are threats to this delicate process. Recent research on hormone influence allows us to understand the germ cell niche, and the delicate balance of the whole process. Cell-to-cell interaction and the internal cycles of spermatogenesis are orchestrated by multiple hormones assuring the success of the system. Although main spermatogenesis genes are described, new discoveries in the role of miRNA and epigenetic events complete the knowledge about spermatogenesis regulation, elucidating their role in cell proliferation and differentiation events at the molecular level. Although spermatogenesis has been studied for a long time, its complexity still requires more research to fully understand and control germ cell development. Due to advancement in cell culture techniques, in vitro spermatogenesis appears to be a promising tool for investigating and understanding this complex process. To achieve this, it is necessary to create a suitable microenvironment that mimics the in vivo conditions of the testis, and supports the survival and development of all the cell types involved in spermatogenesis, ultimately achieving complete and functional spermatogenesis. A better understanding of how to maintain somatic and germinal cells in vitro is required (Ishikura et al., 2021; Kulibin & Malolina, 2023), and new in vitro models such as organoids could play a key role in this aim (Bourdon et al., 2021; Cham et al., 2021; Sakib et al., 2019; Stopel et al., 2024).This strategy offers the potential to simplify cell-to-cell interactions, clarifying the role of hormonal and genetic influence on the process, and providing a suitable model for studying the impact of temperature, environmental change, and toxics substances in the spermatogenesis process (Cham et al., 2024; I. K. Cho & Easley, 2023; Y. Fang et al., 2024; Garcia et al., 2022; Hu et al., 2024; Ibtisham et al., 2017). This strategy not only contributes to basic research but also has potential clinical applications that include infertility treatment, fertility preservation, conservation biology, genetic disorder prevention, and research into human germ cell development, between others (I. K. Cho & Easley, 2023).

References

- Abel, M.H.; Wootton, A.N.; Wilkins, V.; Huhtaniemi, I.; Knight, P.G.; Charlton, H.M. The Effect of a Null Mutation in the Follicle-Stimulating Hormone Receptor Gene on Mouse Reproduction1. Endocrinology 2000, 141, 1795–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acién, P.; del Campo, F.S.; Mayol, M.-J.; Acién, M. The female gubernaculum: role in the embryology and development of the genital tract and in the possible genesis of malformations. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2011, 159, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, A.; Singh, A.; Hamada, A.; Kesari, K. Cell phones and male infertility: a review of recent innovations in technology and consequences. Int. braz j urol 2011, 37, 432–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavattam, K.G.; Maezawa, S.; Andreassen, P.R.; Namekawa, S.H. Meiotic sex chromosome inactivation and the XY body: a phase separation hypothesis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2021, 79, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, R.L.; O'Brien, D.A.; Eddy, E.M. A Novel hsp70-Like Protein (P70) is Present in Mouse Spermatogenic Cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1988, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amann, R.P. A Critical Review of Methods for Evaluation of Spermatogenesis from Seminal Characteristics. J. Androl. 1981, 2, 37–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson MJ and Dixon, AF. (2002). Motility and the midpiece in primates. Nature.

- Anguera, M.C.; Ma, W.; Clift, D.; Namekawa, S.; Kelleher, R.J.; Lee, J.T. Tsx Produces a Long Noncoding RNA and Has General Functions in the Germline, Stem Cells, and Brain. PLOS Genet. 2011, 7, e1002248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, S.; A King, S.; Irvine, D.S.; Saunders, P.T.K. Impact of a mild scrotal heat stress on DNA integrity in murine spermatozoa. Reproduction 2005, 129, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A. R. P. , Miller, I. J., Anderson, P., & Streuli, M. (1998). RNA-binding protein TIAR is essential for primordial germ cell development (gene targetingpartial embryonic lethalityRNA recognition motifribonucleoproteinsterility). In Cell Biology (Vol. 95, pp. 2331–2336). www.pnas.org.

- Bejarano, I.; Rodríguez, A.B.; Pariente, J.A. Apoptosis Is a Demanding Selective Tool During the Development of Fetal Male Germ Cells. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2018, 6, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billard, R. Spermatogenesis and spermatology of some teleost fish species. 1986, 26, 877–920. [CrossRef]

- Binart, N.; Melaine, N.; Pineau, C.; Kercret, H.; Touzalin, A.M.; Imbert-Bolloré, P.; Kelly, P.A.; Jégou, B. Male Reproductive Function Is Not Affected in Prolactin Receptor-Deficient Mice. Endocrinology 2003, 144, 3779–3782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco, M., & Cocquet, J. (2019). Genetic factors affecting sperm chromatin structure. In Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology (Vol. 1166, pp. 1–28). Springer New York LLC. [CrossRef]

- Blesbois, E. Biological Features of the Avian Male Gamete and their Application to Biotechnology of Conservation. J. Poult. Sci. 2012, 49, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bole-Feysot, C.; Goffin, V.; Edery, M.; Binart, N.; Kelly, P.A. Prolactin (PRL) and Its Receptor: Actions, Signal Transduction Pathways and Phenotypes Observed in PRL Receptor Knockout Mice. Endocr. Rev. 1998, 19, 225–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]