Submitted:

06 March 2025

Posted:

07 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

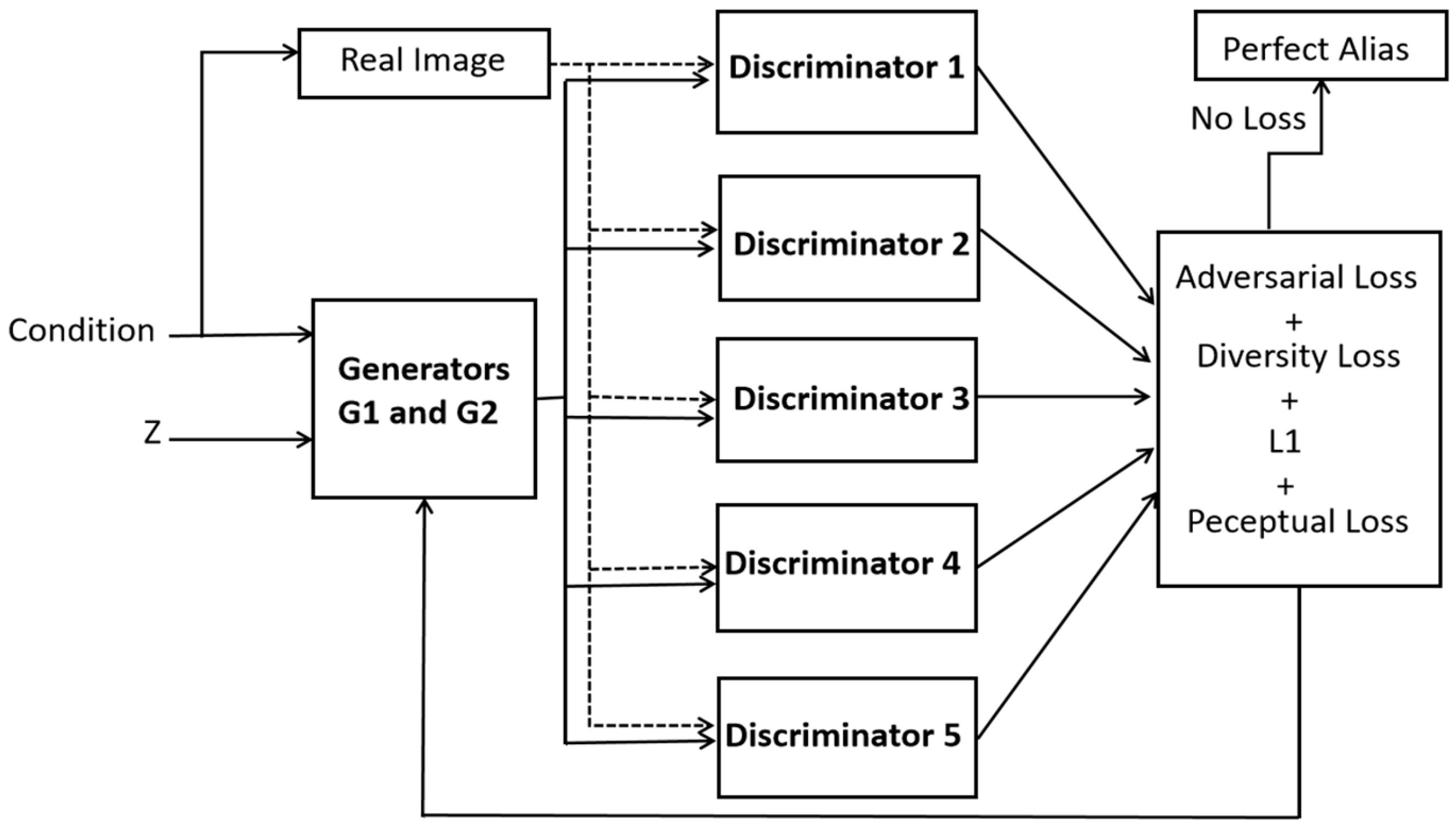

- A novel dual generator architecture using mutual regularization to achieve better generalization for OCT images of coronary arterial plaques. A discriminator (D1) within the network is used for classification alleviating the need for a separate classification architecture resulting in computational efficiency.

- A novel architecture of dynamic multi-discriminator fusion is designed to play an adversarial game against two generators. We introduce a dynamic fusion mechanism to adjust the weighting of discriminators based on the image specific conditions.

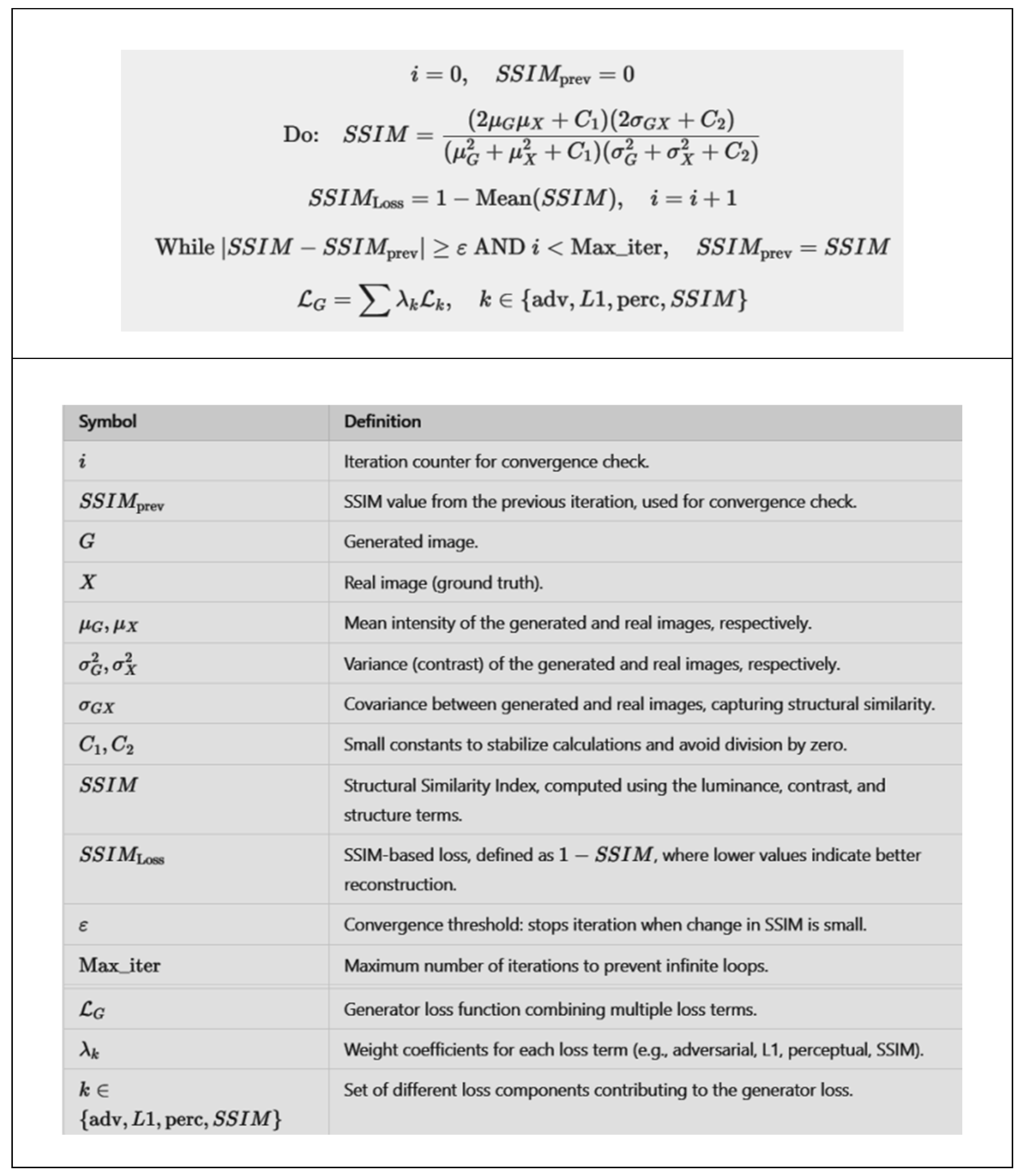

- Essentially, we incorporated adversarial loss, perceptual loss, L1 loss, cross entropy and diversity loss in our loss function for an enhanced realism in the generated images.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. OCT Dataset and Its Pre-Processing

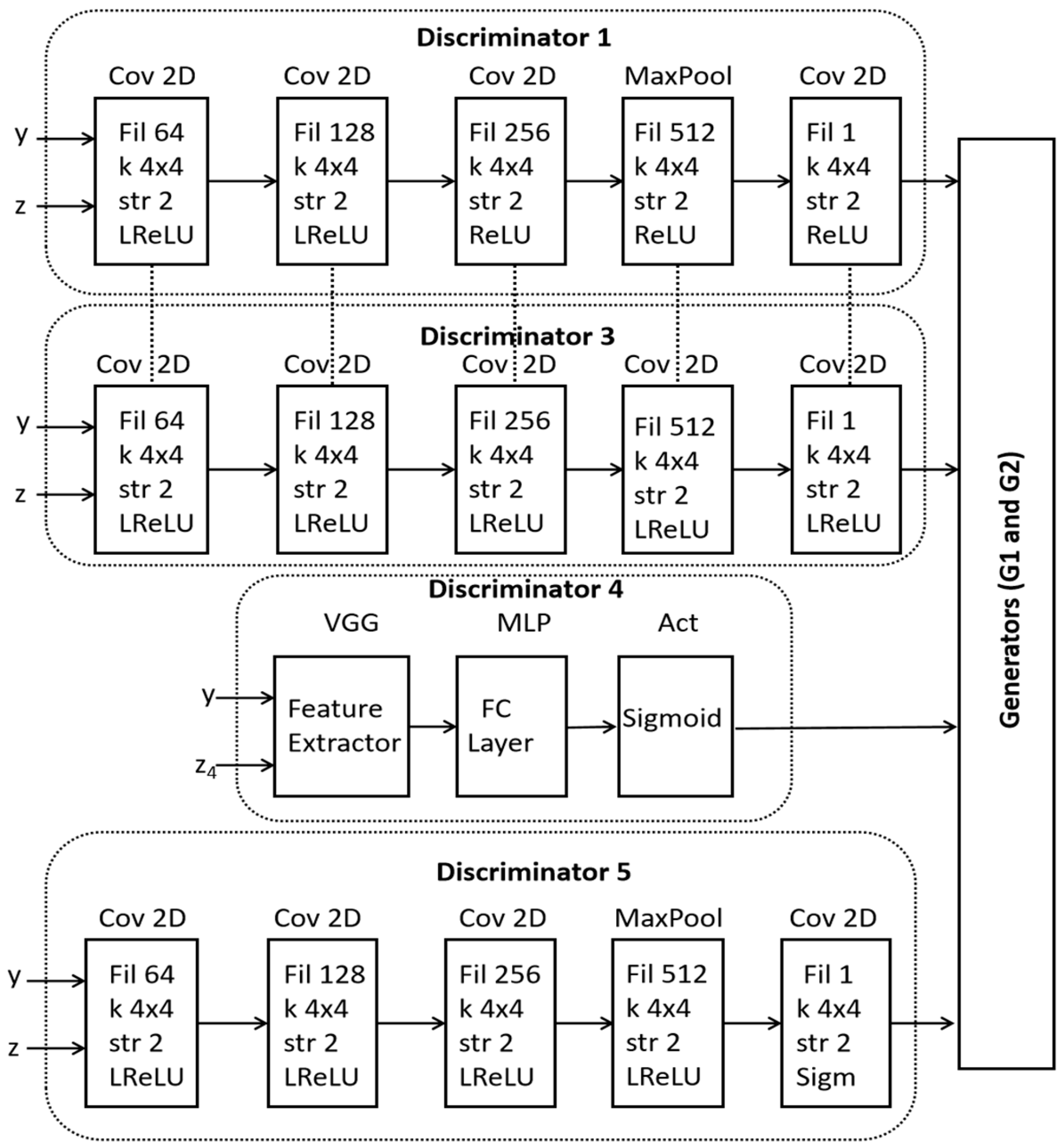

2.2. Proposed Dual Generator Multi-Fusion GAN

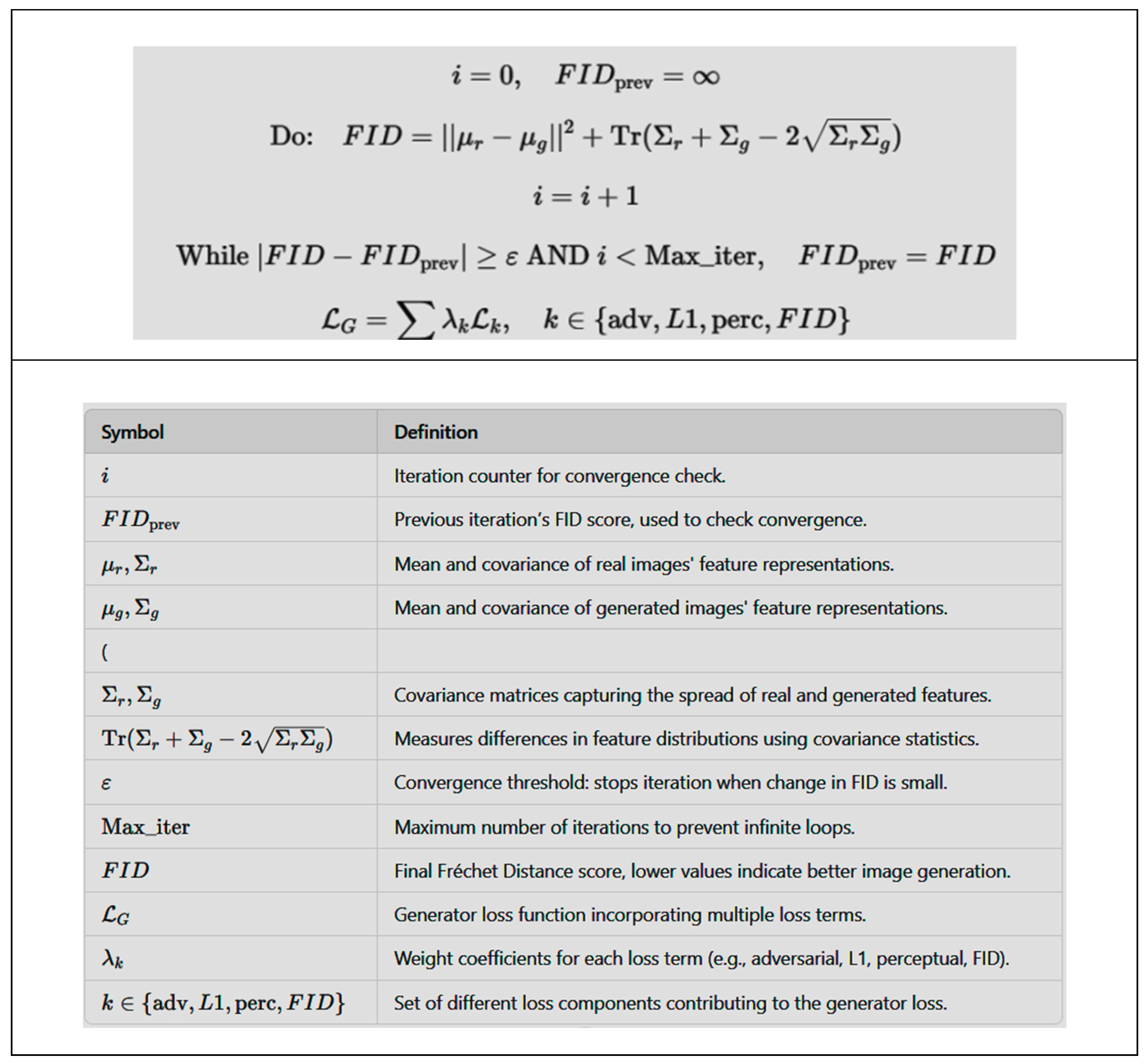

2.3. Mathematical Formulation

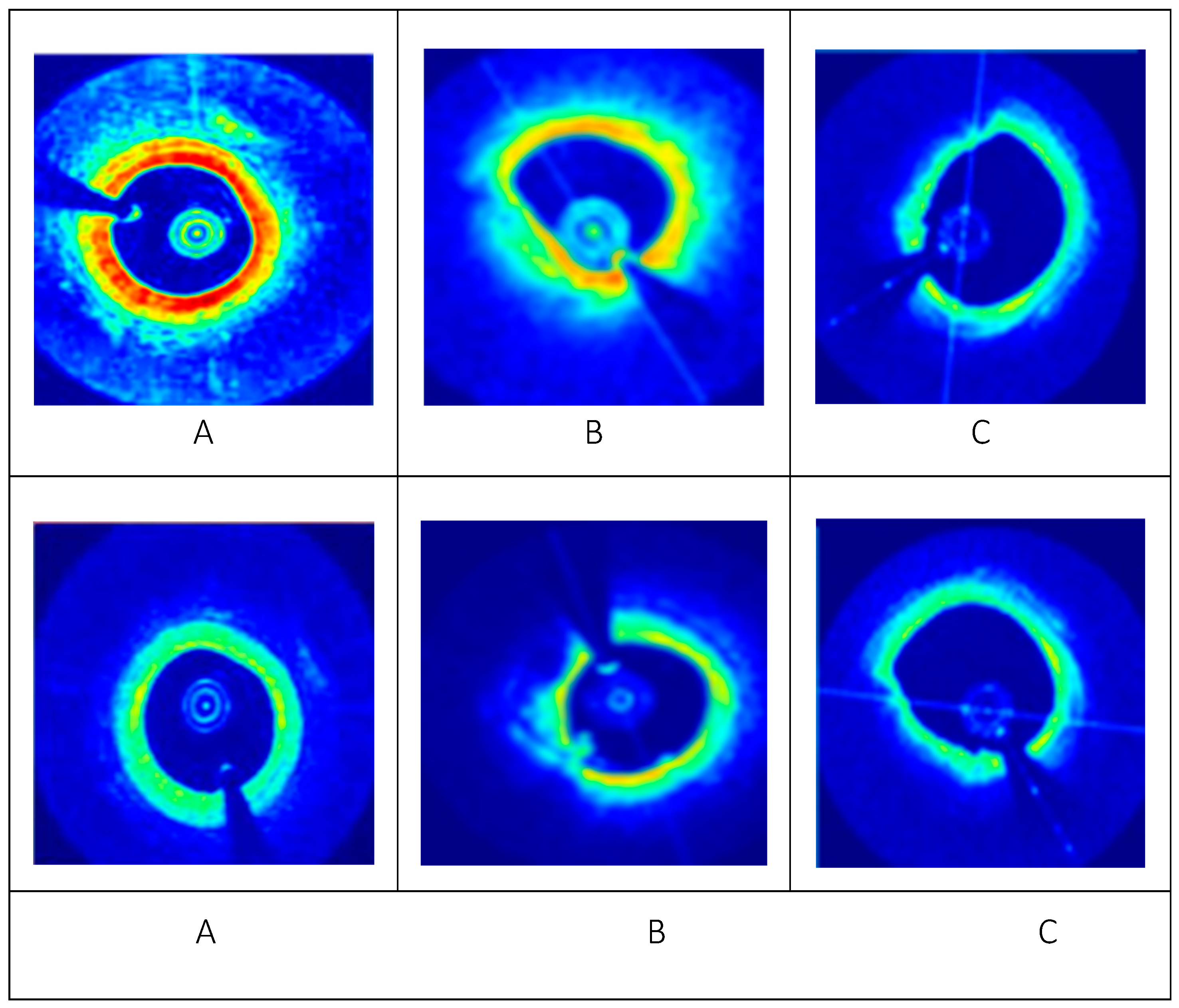

3. Results and Analysis

4. Conclusions

References

- Borrelli, N.; Merola, A.; Barracano, R.; Palma, M.; Altobelli, I.; Abbate, M.; Papaccioli, G.; Ciriello, G.D.; Liguori, C.; Sorice, D.; et al. The Unique Challenge of Coronary Artery Disease in Adult Patients with Congenital Heart Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2024. [CrossRef]

- https://www.cdc.gov/heart-disease/about/coronary-artery-disease.html.

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK355309/.

- Młynarska, E.; Czarnik, W.; Fularski, P.; Hajdys, J.; Majchrowicz, G.; Stabrawa, M.; Rysz, J.; Franczyk, B. From Atherosclerotic Plaque to Myocardial Infarction—The Leading Cause of Coronary Artery Occlusion. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.; Ran, A.R.; Nguyen, T.X.; Lin, T.P.H.; Chen, H.; Lai, T.Y.Y.; Tham, C.C.; Cheung, C.Y. Deep Learning in Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography: Current Progress, Challenges, and Future Directions. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zafar, H.; Zafar, J.; Sharif, F. Automated Clinical Decision Support for Coronary Plaques Characterization from Optical Coherence Tomography Imaging with Fused Neural Networks. Optics 2022, 3, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, H.; Zafar, J.; Sharif, F. GANs-Based Intracoronary Optical Coherence Tomography Image Augmentation for Improved Plaques Characterization Using Deep Neural Networks. Optics 2023, 4, 288–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/tbio.201900034.

- https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/2057-1976/aab640/meta.

- Araki, M. , Park, SJ., Dauerman, H.L. et al. Optical coherence tomography in coronary atherosclerosis assessment and intervention. Nat Rev Cardiol 19, 684–703 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Oosterveer, T.T.M. , van der Meer, S.M., Scherptong, R.W.C. et al. Optical Coherence Tomography: Current Applications for the Assessment of Coronary Artery Disease and Guidance of Percutaneous Coronary Interventions. Cardiol Ther 9, 307–321 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Sant Kumar, Miao Chu, Jordi Sans-Roselló et al., In-Hospital Heart Failure in Patients With Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy Due to Coronary Artery Disease: An Artificial Intelligence and Optical Coherence Tomography Study, Cardiovascular Revascularization Medicine,Volume 47, 2023, Pages 40-45. [CrossRef]

- Mintz, Gary S et al.Intravascular imaging in coronary artery disease, The Lancet, Volume 390, Issue 10096, 793 - 809. [CrossRef]

- Matthews, Stephen Daniel MD; Frishman, William H. MD, A Review of the Clinical Utility of Intravascular Ultrasound and Optical Coherence Tomography in the Assessment and Treatment of Coronary Artery Disease, Cardiology in Review 25(2):p 68-76, March/April 2017. [CrossRef]

- Aiko Shimokado, Yoshiki Matsuo, Takashi Kubo et al., In vivo optical coherence tomography imaging and histopathology of healed coronary plaques, Atherosclerosis, vol. 275, pp. 35-42, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, H.J.; Ghayesh, M.H.; Zander, A.C.; Li, J.; Di Giovanni, G.; Psaltis, P.J. Automated Coronary Optical Coherence Tomography Feature Extraction with Application to Three-Dimensional Reconstruction. Tomography 2022, 8, 1307–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Infact 15 Avital, Y., Madar, A., Arnon, S. et al. Identification of coronary calcifications in optical coherence tomography imaging using deep learning. Sci Rep 11, 11269 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Niioka, H. , Kume, T., Kubo, T. et al. Automated diagnosis of optical coherence tomography imaging on plaque vulnerability and its relation to clinical outcomes in coronary artery disease. Sci Rep 12, 14067 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Yoon M, Park JJ, Hur T, Hua CH, Hussain M, Lee S, Choi DJ. Application and Potential of Artificial Intelligence in Heart Failure: Past, Present, and Future. Int J Heart Fail. 2023 Nov 30;6(1):11-19. [CrossRef]

- Molenaar, M.A. , Selder, J.L., Nicolas, J. et al. Current State and Future Perspectives of Artificial Intelligence for Automated Coronary Angiography Imaging Analysis in Patients with Ischemic Heart Disease. Curr Cardiol Rep 24, 365–376 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Föllmer, B., Williams, M.C., Dey, D. et al. Roadmap on the use of artificial intelligence for imaging of vulnerable atherosclerotic plaque in coronary arteries. Nat Rev Cardiol 21, 51–64 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Seetharam K, Min JK. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Cardiovascular Imaging. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc J. 2020 Oct-Dec;16(4):263-271. [CrossRef]

- Langlais, É.L., Thériault-Lauzier, P., Marquis-Gravel, G. et al. Novel Artificial Intelligence Applications in Cardiology: Current Landscape, Limitations, and the Road to Real-World Applications. J. of Cardiovasc. Trans. Res. 16, 513–525 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Thomas, T., Kurian, A.N. (2022). Artificial Intelligence of Things for Early Detection of Cardiac Diseases. In: Al-Turjman, F., Nayyar, A. (eds) Machine Learning for Critical Internet of Medical Things. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Chen, SF., Loguercio, S., Chen, KY. et al. Artificial Intelligence for Risk Assessment on Primary Prevention of Coronary Artery Disease. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep 17, 215–231 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Bozyel S, Şimşek E, Koçyiğit Burunkaya D, Güler A, Korkmaz Y, Şeker M, Ertürk M, Keser N. Artificial Intelligence-Based Clinical Decision Support Systems in Cardiovascular Diseases. Anatol J Cardiol. 2024 Jan 7;28(2):74–86. [CrossRef]

- Ke-Xin Tang, Yan-Lin Wu, Su-Kang Shan et al.,Advancements in the application of deep learning for coronary artery calcification, Meta-Radiology,vol.3, Issue 1, 100134. [CrossRef]

- J. Lee et al., “Segmentation of Coronary Calcified Plaque in Intravascular OCT Images Using a Two-Step Deep Learning Approach,” in IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 225581-225593, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Infact 15 Lee, J., Prabhu, D., Kolluru, C. et al. Fully automated plaque characterization in intravascular OCT images using hybrid convolutional and lumen morphology features. Sci Rep 10, 2596 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Infact 16 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S174680942300321X.

- X. Li et al., “Multi-Scale Reconstruction of Undersampled Spectral-Spatial OCT Data for Coronary Imaging Using Deep Learning,” in IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, vol. 69, no. 12, pp. 3667-3677, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Bifurcation detection in intravascular optical coherence tomography using vision transformer based deep learning. [CrossRef]

- Rongyang Zhu, Qingrui Li, Zhenyang Ding, Kun Liu, Qiutong Lin, Yin Yu, Yuanyao Li, Shanshan Zhou, Hao Kuang, Junfeng JiangShow full author list.

- Published 18 July 2024 • © 2024 Institute of Physics and Engineering in Medicine Physics in Medicine & Biology, Volume 69, Number 15Citation Rongyang Zhu et al. 2024 Phys. Med. Biol. 69 155009.

- Yiqing Liu, Farhad R. Nezami, Elazer R. Edelman,A transformer-based pyramid network for coronary calcified plaque segmentation in intravascular optical coherence tomography images, Computerized Medical Imaging and Graphics,Volume 113, 2024, 102347. [CrossRef]

- S. Zheng, W. Shuyan, H. Yingsa and S. Meichen, “QOCT-Net: A Physics-Informed Neural Network for Intravascular Optical Coherence Tomography Attenuation Imaging,” in IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics, vol. 27, no. 8, pp. 3958-3969, 2023. [CrossRef]

- https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.05990.

- Kugelman, J. , Alonso-Caneiro, D., Read, S.A. et al. Enhancing OCT patch-based segmentation with improved GAN data augmentation and semi-supervised learning. Neural Comput & Applic 36, 18087–18105 (2024). [CrossRef]

- X. Li et al., “Cross-Platform Super-Resolution for Human Coronary Oct Imaging Using Deep Learning,” 2024 IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI), Athens, Greece, 2024, pp. 1-5. [CrossRef]

- K. Zhou et al., “Sparse-Gan: Sparsity-Constrained Generative Adversarial Network for Anomaly Detection in Retinal OCT Image,” 2020 IEEE 17th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI), Iowa City, IA, USA, 2020, pp. 1227-1231. [CrossRef]

- J. Ma, H. Xu, J. Jiang, X. Mei and X. -P. Zhang, “DDcGAN: A Dual-Discriminator Conditional Generative Adversarial Network for Multi-Resolution Image Fusion,” in IEEE Transactions on Image Processing, vol. 29, pp. 4980-4995, 2020.

- M. Tajmirriahi, R. Kafieh, Z. Amini and V. Lakshminarayanan, “A Dual-Discriminator Fourier Acquisitive GAN for Generating Retinal Optical Coherence Tomography Images,” in IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement, vol. 71, pp. 1-8, 2022, Art no. 5015708. [CrossRef]

- C. Zhao et al., “MHW-GAN: Multidiscriminator Hierarchical Wavelet Generative Adversarial Network for Multimodal Image Fusion,” in IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems, vol. 35, no. 10, pp. 13713-13727, 2024. [CrossRef]

- [42] P. Jeihouni, O. Dehzangi, A. Amireskandari, A. Rezai and N. M. Nasrabadi, “MultiSDGAN: Translation of OCT Images to Superresolved Segmentation Labels Using Multi-Discriminators in Multi-Stages,” in IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics, vol. 26, no. 4, pp. 1614-1627, April 2022. [CrossRef]

| Model Description | SSIM | FID Score | L1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Generator with two SR Layer, MultiSD Module [42] | 0.7933±0.0077 | 39 | 0.057±0.0028 |

| MultiSDGAN Module with Attention mechanism [42] | 0.8240±0.0028 | 16 | 0.032±0.0017 |

| Proposed DGDFGAN | 0.9542±0.008 | 7 | 0.010±0.0005 |

| Model Description | SSIM | FID Score | L1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| DDFA-GAN model using dual disciminators [40] | 0.7350±0.0064 | 67 | 0.054±0.0047 |

| MHW-GAN for multimodal image fusion using triple discriminators [41] | 0.7718±0.0039 | 46 | 0.054±0.0047 |

| Multi- SDGAN with attention mechanism using maximum discriminators [42] | 0.8611±0.0017 | 12 | 0.032±0.0017 |

| Dual Generator proposed model | 0.9452±0.008 | 7 | 0.010±0.0005 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).