1. Introduction

The notion of a network is universal. Networks are

everywhere. They can be imagined as a collection of interconnecting elements of

a definite nature. The elements should be distinguishable since otherwise it is

difficult to observe them and to make some reasonable conclusions. The water

flow is not a network, therefore. However, it can be modeled mathematically

successfully. The constellations are networks if the stars are identified and

observable. A great challenge is to detect, observe, describe, and make

conclusions about small and even microscopic networks. Networks of these type

can be found on atomic and molecular levels.

What is interesting about networks and how

knowledge of them can be useful for humans? The first question is philosophical

and a little bit relates to arts and artistic Perception of life. The second

question is practical and is important for humans to increase essential living

factors and improve the level of life. Examples are telecommunications network

systems for transmitting data over distances. (Example: Telephone networks) and

broadcast networks, as well as computer networks, sensor networks, trade networks,

financial networks, and so on.

Of special interest are biological networks, such

as neural networks, complex networks of neurons in the brain and nervous system

(Example: Human brain neural network), ecological networks, such as

interactions between different species in an ecosystem (Example: Food webs in a

forest ecosystem), genetic networks, reflecting interactions between genes and

gene products ( Example: regulatory gene networks in cells).

The topic we have chosen for the review relates to

biology. It is not possible to observe neural networks and genetic networks by

unarmed eye, but these networks exist and knowledge of them is extremely

important for humanity. Experimenters can, by improving technique and

methodology, obtain a lot of information about hardly obtainable networks.

Systematization of gained data and analysis are difficult tasks. Recall, that

the main information about genes is a relatively recent matter. According to

data in [1] “gene regulatory networks (GRNs)

began to be studied in earnest in the late 1990s and early 2000s. The advent of

high-throughput gene expression technologies, such as microarrays and later RNA

sequencing, allowed scientists to measure the expression levels of thousands of

genes simultaneously. This technological advancement made it possible to infer

and analyze GRNs on a large scale.” The mathematical theory of networks is a

reflection of actually existing objects. This is the theory of gene networks.

The theory must capture the essential regularities, and the basic principles of

the functioning of networks. This predicts the behavior of networks with a

given data set. In mathematical theory, correspondences with already known

observations can be found. At the same time, predictions that logically follow

from a formal theory can be observed in the presence of appropriate conditions.

This is evidence of its reasonable construction. Let us consider one approach

to the construction of the theory of gene networks, focusing on the presence of

these characteristics. In the beginning, there was progress in the study of the

behavior and development of biological objects, which stimulated the

introduction of the concept of a gene network. It became clear that the most

important issues of the development and vital activity of living organisms are

supported by the coordinated expression of various groups of genes. A gene

regulatory network (GRN) is understood as a set of coordinatedly expressed

genes, their protein products, and the relationships between them.

Inferring gene regulatory networks (GRNs) is a fundamental problem in

biology that aims to reveal the complex relationships between genes and their

regulators. Mathematical methods can be used effectively to solve this and

related issues. How these principles are implemented in the construction of a

theory of the evolution of gene networks.

2. Data, Model, Applications

One of the references in our literature list says Nothing

in Biology Makes Sense except in the Light of Evolution [2]. To a great extent this is true also for the

networks theory. Having this in mind look at the system of ODE

Suppose that are sigmoidal functions that

monotonically increase from a=0 to b=1. The values of a

and b need not be positive, but can. Assume that generally nonlinear

functions are for description of the

relations between elements of a network. These elements have the

characteristics dependent on the argument t,

interpreted as time. Solutions of the system (1) are meant as smooth functions satisfying the equations (1).

The specific structure of the system (1) can be explained in the following way.

It is assumed that elements of a network interrelate generally in a nonlinear

way and -th element is affected by the total effect of the

remaining elements as indicated in (1). To be realistic, this total effect is

bounded. The second term means the degradation of the i-th gene

expression product; wij—the

connection weight or strength of control of gene j on gene i.

Positive values of wij signify

activating influences, whereas negative values denote repressing influences; θi—the impact

of external stimuli on gene i is reflected in its ability to modulate

the gene’s responsiveness to activating or repressing factors.

Definition 1. An invariant region in the

phase space is the region that cannot be left by a trajectory of system (1).

Proposition 1. The parallelepiped is an invariant set.

Consider the system of equations

Proposition 2. The system (2) has a solution

in the invariant set .

Sketch of the proof. On the border of the invariant

set the

vector field

Փ={ } is directed inward. Therefore, the continuous map

Փ maps the topological ball into itself. So the map Փ has

a fixed point in □

Definition 2. A set of points defined by the

relation is called an i-th nullcline

of the system (1).

Definition 3. Cross-points of all nullclines

are called critical points of the system (1).

Corollary of Proposition 2. System (1) has a

critical point in an invariant set

Proposition 3. All critical points of

system (1) are in the invariant set

Proof. Any critical point belongs to all

nullclines. Any nullcline lies in the strip for

some . These strips intersect by the set □

Remark. System (1) has at least one critical

point but can have multiple critical points.

Critical points are subject to analysis. The

standard analysis of a critical point involves the following procedure.

Standard analysis. The goal is to obtain a vector which consists of the characteristic numbers. The characteristic numbers, with some degenerate cases, provide information about the type of a critical point.

First, the linearization of the system (1) is constructed. Some refinements of the standard process applied to systems of the form (1) are discussed in the results section.

4. Conclusions

What are nullclines and how do they affect the behavior of trajectories?

Nullclines of the system (1) are continuous surfaces defined by the relations (2). They can be visualized using appropriate software for 2D and 3D systems. For higher dimensional systems the projections of nullclines onto the lower order subspaces are possible. To imagine how they look for higher dimensions is problematic. This is beyond the human senses, but quite the usual thing for theoretical mathematics. Look at the system

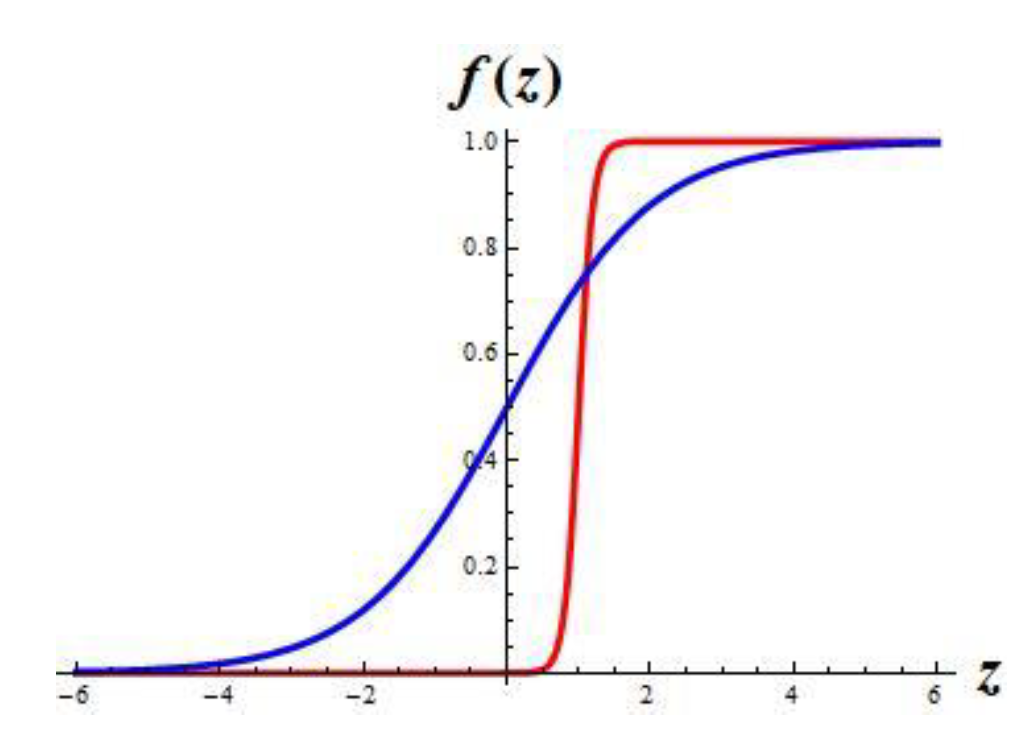

This system uses the sigmoidal function

which has the graph in

Figure 1.

What is the impact of parameters in the function. The graph stretches in the strip between zero and one values. Increasing the parameter μ results in the steeper middle segment of the graph. This segment becomes almost vertical as μ tends to +ꝏ. Changing the parameter θ results in shifting the graph in the horizontal direction.

In a model function

f is used depending on multiple variables

. Moreover the combination of variables may be transformed in many ways. Look at system (4).

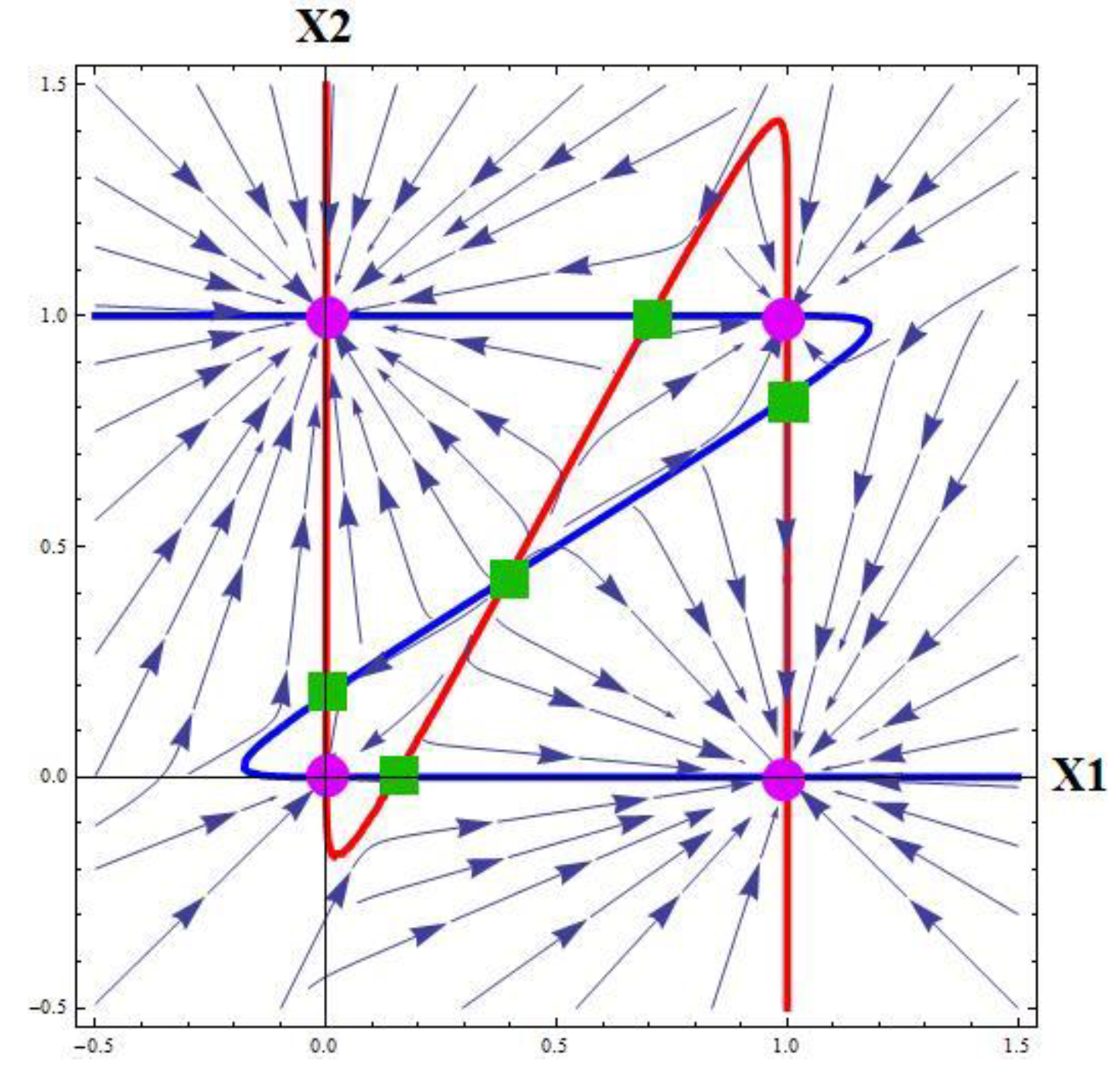

What are critical points and how many they are?

The critical points are points of intersection of nullclines. How many critical points are possible for the 2D system?

Figure 2 shows the nullclines for some particular choice of parameters. Since the nullclines are intersected at 9 points, and more intersections are not possible, we are led to the conclusion that the maximal number of critical points is 9. Of them, four critical points are attractive, and the remaining are saddle points.

Generally, the number of critical points depends on the dimensionality of a system but is finite.

What are attractors and what is their role in the study of a model and of a network?

Attractors are subsets of the phase space , which attract trajectories (as the argument

t tends to +infinity) from the initial points that are in at least in close proximity (in some neighborhood) of an attractor. If all trajectories of interest are attracted, an attractor is global. System (1) has an invariant set, and all trajectories of interest have the initial conditions in it. If any trajectory starting in

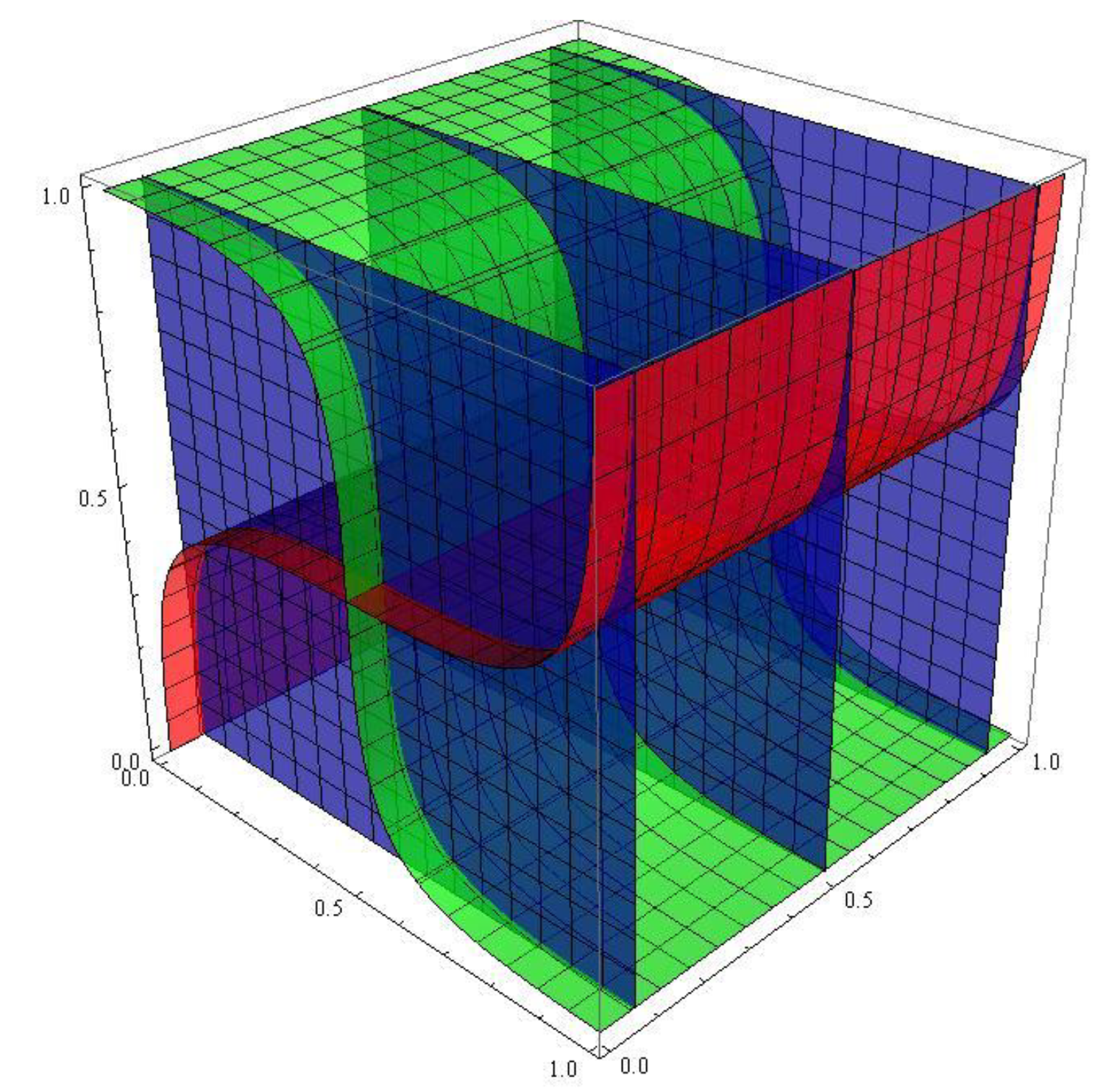

tends to an attractor, this attractor is global. Consider an example. Let the three-dimensional system be

The nullclines of this system are defined by the relations

Notice that the system (5) is uncoupled. It consists of a coupled two dimensional (2D) system

and a single equation

Can critical points be attractors and how to detect them?

They can, and they are detectable by solving system (2), where

is specified for the case. For 2D system (3) stable nodes and focuses are attractors. Their type can be detected visually and by analytical means. For higher order systems the role of analytical methods increases. There are also degenerate cases where some characteristic numbers are zero, but the point in question is attractive. For general information on these things, the book [

3] provides needed information.

Technique for the local analysis and improvements

This technique is standard but can be significantly simplified due to the specific structure of the system. Let us consider the system

The critical point

must satisfy the relations

The linearization at a critical point

is

Since from (9)

the relations (11) become

The characteristic equation ( is a unity matrix) then is a cubic equation with coefficients expressed explicitly in terms of the critical point.

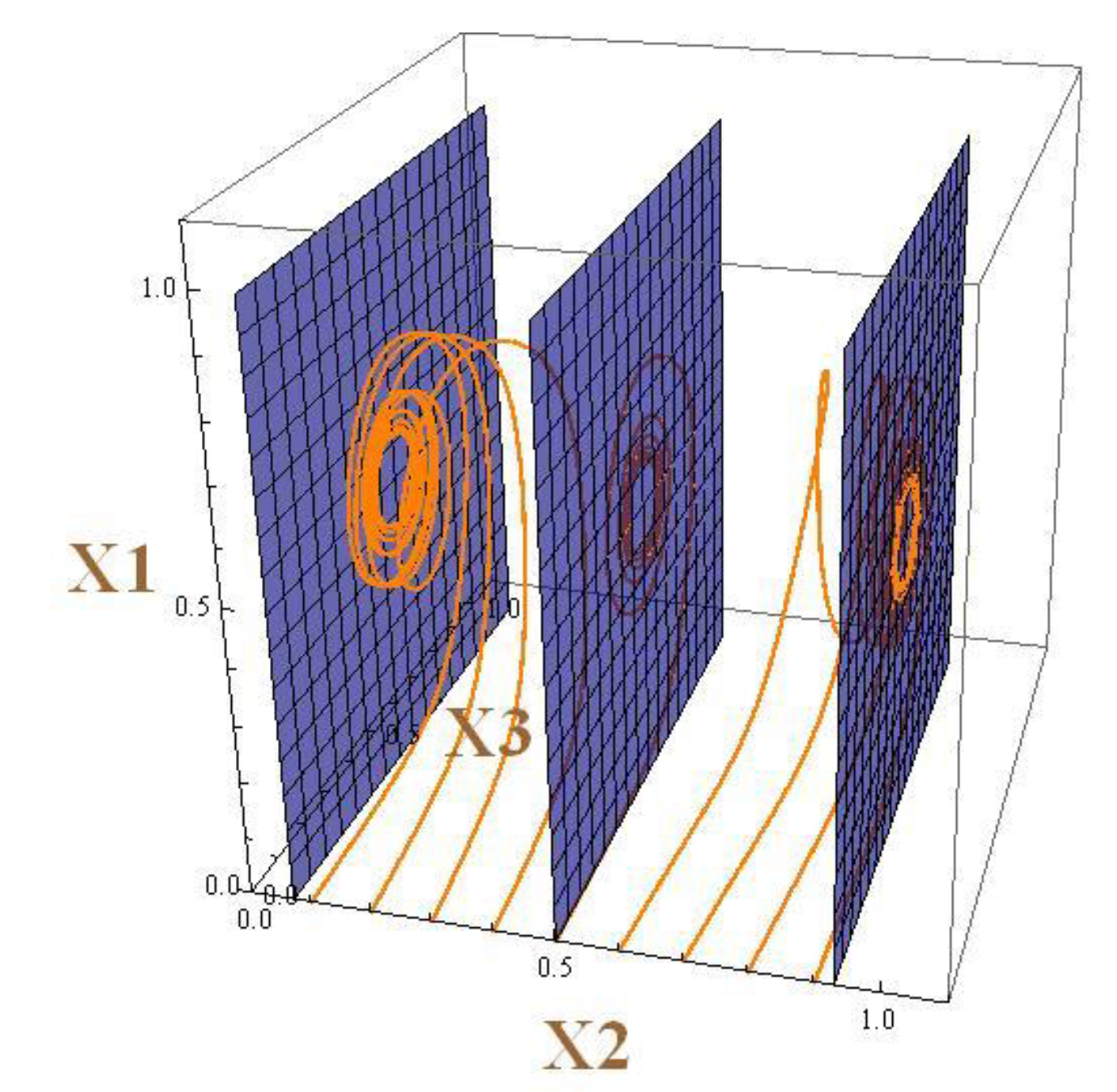

Can periodic solutions be attractors? How do they appear and what do they look like?

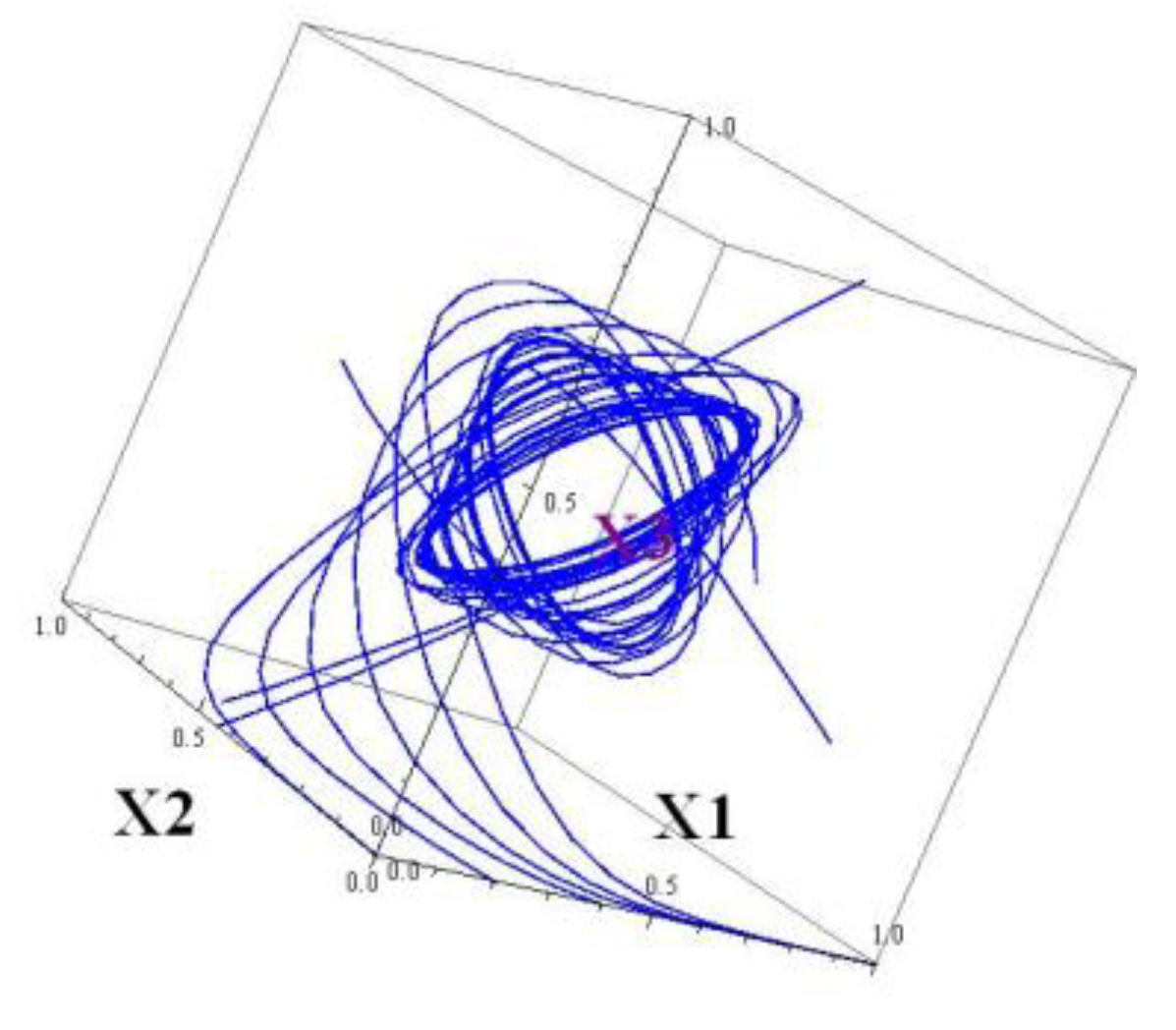

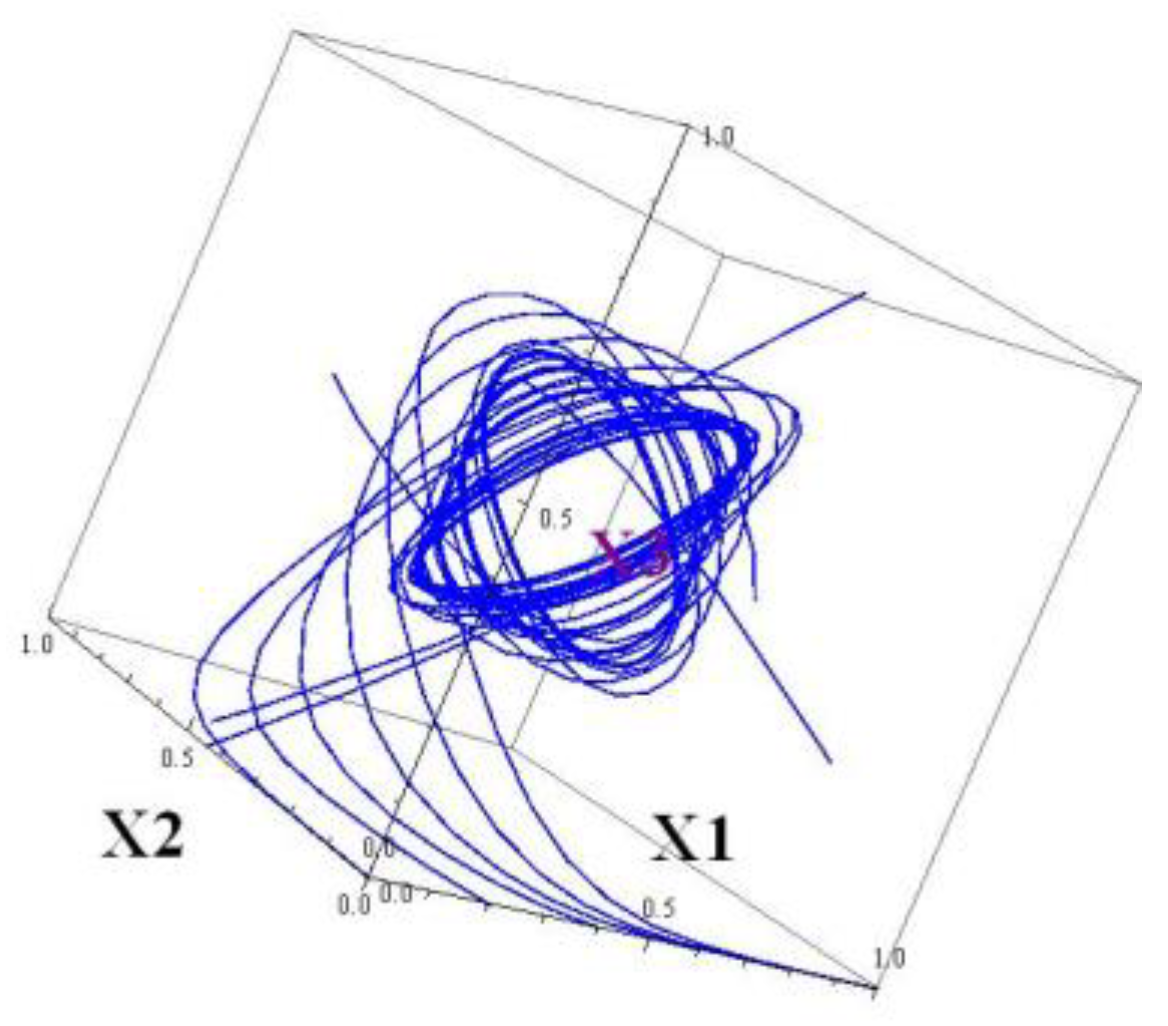

Periodic solutions can be attractors. The system (5) has three periodic solutions. The respective trajectories are located in the vertical planes depicted in

Figure 4. The middle plane contains a periodic trajectory that attracts trajectories with the initial point in this plane. This plane divides the invariant cube in two parts. The trajectories which have initial points to the left of the middle plane tend to the closed trajectory located in the left plane. Similarly behave trajectories starting on the right.

How to see attractors in 4D systems, and more.

The easiest way to see an attractor in a 4D system is to take two copies of a 2D system that has an attractor and build a 4D uncoupled system of them. For instance, take the system (2) and construct the 4D system

which is uncoupled. Take the parameters as in system (5) and consider the system

This system has a 4D attractor. It cannot be viewed, but projections to 2D and/or 3D subspaces can. By construction, the projections onto

and

subspaces looks similar. The projections onto the

3D subspaces

) and (

) are depicted in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6.

If a nonzero element is inserted in the matrix , the system immediately may become pre-chaotic, exhibiting a sensitive dependence on the initial data. Testing on the Lyapunov exponents shows these changes.

Several resuts on this matter were published in [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. The chaotic attractor for 3D systems were discovered

Miscellaneous

GRN are studied not only theoretically, but also having in mind practical applications. The need for managing and control of some GRN stems from the research on the border of medicine and mathematics. In the papers [

11], [

12] the mathematical problems related to the explanation of genetic issues of leucemia were considered. The authors have constructed the scheme of GRN, which has three attractors. The disease is associated with the tending of the network state to a “bad” attractor. The healthy states are associated with ”normal” attractors. The mathematical problem of treating leucemia is redirecting the system states from a “bad” attractor to a normal one, using adjustable parameters. In the work [

13] the authors construct an aging gene regulatory network consisting of the core cell cycle regulatory genes. The process of aging can be characterized by state transitions from the landscape I to II. For networks with a large number of elements the mathematical problem of redirecting a trajectory from one attractor to another is challenging. Although for low dimensional networks this problem can be resolved provided that some needed information is possible. Imagine that there are several attractors and their basins of attractions (all in the invariant set

Qn). The current state ( a point in the phase space) is given. The future states are known since the respective trajectory is defined by the initial point. The trajectory goes to a certain attractor. There is a need to redirect the trajectory to another attractor. Sometimes it is possible by changing certain parameters.

For illustration return to system (5). It has the second nullcline in the form of three planes where on the right are the roots of the equation These roots are r1=0.07072, r2=0.5, r3=0.92928. Let the current state of the system be (0.5, 0.2, 0.5). The trajectory from this point goes to the limit cycle of the 2D system (7) at x2=r1. Suppose there is need to redirect this trajectory to the right attractor at x2=r3. This can be done by adjusting a single parameter θ2 to the value 0.42. Only one attractor at x2=0.962948 remains. After the trajectory is sufficiently close to a single attractor at x2=0.962948, the parameter θ2 can be made again 0.5. The system state is now in the basin of attraction of the attractor at x2=r3.

Conclusion (Review of the Literature)

In [

14] the role of Lyapunov exponents in detecting chaotic behavior is discussed in the examples of 4D genetic and neural models. In [

15] different approaches to the study of GRN are reviewed. In [

16] the 2D system was studied. The bifurcation curves in the

plane was constructed that separates regions corresponding to two and one attracting critical points. The paper [

17] contains the results of the activation case when entries of the regulatory matrix W are positive. It is a rare sample of articles where the n-dimensional system is studied. In particular, the results of [

16] are generalized under the assumption that the sum of elements in each row of the matrix W is the same. The book [

18] is helpful for researchers active in the study of chaos. It contains interesting suggestions on dynamical systems involved in modeling GRN. The article [

19] is a review of several approaches being used to study GRN. The 3D particular system was studied in [

20] providing detailed information on critical points and chaotic behavior of solutions. [

21] is the application of GRN type systems to managing telecommunication networks. Article [

22] is probably the first where GRN type systems appear but they were focused on interrelation of populations of neurons. In [

23] the problem of control in 2D GRN type systems was considered. The Gompertz function was chosen to represent nonlinearity. Articles [

24], [

25], [

26] contain results on both genetic and neuronal networks, using Gompertz and logistic nonlinearities. The comparison was made. The titles of the works [

27], [

28], [

29] are quite informative. In the paper [

30] the six-order GRN type system was considered. The 3D projections of the obtained attractors are presented. Periodic solutions of 2D, 3D and 4D GRN type systems were considered in [

31]. Various examples of biologically induced and GRN type systems were considered in the PhD dissertation by E. Brokan. In the work [

33] the authors attempt to understand how the joint dynamics of molecules, cells, genes and pathways may be integrated in the framework of aging biology research contributing to aging. It is proposed that “organismal function is accomplished by the integration of regulatory mechanisms at multiple hierarchical scales, and … the disruption of this ensemble causes the phenotypic and functional manifestations of aging.” Some key examples at different scales are presented that can potentially enrich the understanding of aging. In [

34] the authors divide the modeling networks to knowledge-driven and data-driven. This division is discussed within the framework of mechanistic learning. This term refers to the synergistic combination of mechanistic mathematical modeling and data-driven machine or deep learning. This emerging field finds increasing applications in (mathematical) oncology. The single-cell methods are reviewed in [

35]. These methods are well suited for GRN investigations. The observation of important factors, resolving gene expression in individual cells can allow subtle behaviours to be detected. An overview of computational approaches to GRN modeling and analysis is presented in the work [

36]. The description of processes in living systems through the concept of computation is in focus in the paper [

37]. A continuous stream of information receiving and processing by living systems, from single cells to higher vertebrates, is considered as biological computation. The authors highlight the limitations of the current attractor-based framework for understanding computations in biological systems. The authors in [

38] review biomedical applications and analyses of interactions among gene, protein and drug molecules for modeling disease mechanisms and drug responses. It is mentioned in the work [

39] that one of the “outstanding problems in complexity science and engineering is the study of high-dimensional networked systems and of their susceptibility to transitions to undesired states as a result of changes in external drivers or in the structural properties.” Because of the large number of parameters controlling the state of such complex systems, “the study of their dynamics is extremely difficult.” The authors propose an analytical framework for collapsing complex N-dimensional networked systems into an S+1-dimensional manifold with S << N. In [

40] a challenging systems biology problem of searching for possible biochemical networks that perform a certain function is considered. The authors try to elaborate an approach to solve this problem by training a recurrent neural network (RNN) to perform the desired function. The review [

41] examines “GRN modeling approaches in aging, encompassing differential equations, Boolean/fuzzy logic decision trees, Bayesian networks, mutual information, and regression clustering. These approaches provide nuanced insights into the intricate gene-protein interactions in aging, unveiling potential therapeutic targets and ARD biomarkers.” The broad spectrum of problems concerning complexity, entropy and statistical learning in nonlinear dynamics is considered in [

42]. An impressive list of references contains 207 items. The current problems in complex networks such as network entanglement, order parameter dynamics and model reduction methods for complex network systems are discussed in [

43], [

44], [

45]. In the work [

46] the authors declare that ”an accurate prediction of the dynamics seems hardly feasible, because the network is often complicated and unknown. In this work, given past observations of the dynamics on a fixed graph, we show the contrary: Even without knowing the network topology, we can predict the dynamics. Specifically, for a general class of deterministic governing equations, we propose a two-step prediction algorithm.” The problems of morphogenesis as results from the activity of gene networks are discussed in [

47]. The fuzzy systems, problems of synchronization, robustness and resilience are considered in [

48], [

49], [

50].

The selection of article for this mini-review is subjective and reflects only the current interest of the author.