1. Introduction

Large-scale integrated circuits and field-programmable gate arrays are receiving significant attention in modern technology. Many sectors, from automotive to healthcare, rely heavily on these technologies. While LSIs offer high-density integration and optimized performance, FPGAs provide flexibility and reconfigurability, making them complementary technologies in many applications [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Given their critical role, ensuring device reliability through comprehensive testing has become paramount, as faulty devices can significantly impact system operations and societal functionality. This necessitates extensive testing across various manufacturing stages under diverse conditions [

5]. As these semiconductor devices grow in complexity and functionality, the volume of required tests has surged, resulting in rising test costs. This escalating expense is a major concern, as testing now constitutes a substantial portion of the overall manufacturing cost for both LSIs and FPGAs [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. The challenge of maintaining thorough testing while managing costs is particularly pronounced in FPGAs, where the reconfigurable nature of the device adds an extra layer of complexity to the testing process. Various test cost reduction methods have been proposed that apply data analytics, machine learning algorithms, and statistical methods [

11,

12,

13,

14,

14]. In particular, the wafer-level characteristic modeling method based on the statistical algorithm is the most promising candidate that reduces the test cost, that is, measurement cost, without impairing the test quality [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. On the other hand, the state-of-the-art FPGA estimation proposed in [

8,

9,

10] shows that the estimated measurements can be drastically reduced through a compressed sensing-based

virtual probe technique [

8,

9,

22,

23,

24]. However, as experimentally shown in [

13,

25,

26], the experiments are conducted using wafer measurement data from a mass industry production, the

Gaussian process GP-based estimation method surpasses the techniques presented in [

8,

9,

16,

17,

18,

19] which is based on compressed sensing [

23,

24]. Because the estimation eliminates the need for measurement, it not only reduces the cost of measurement but also can be used to reduce the number of test items and/or change the test limits, which is expected to improve the efficiency of adaptive testing [

27,

28,

29,

30]. In [

15], the expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm [

31] was used to predict the measurement. The

Gaussian process-based method provides more accurate prediction results [

13,

14,

20,

21,

25,

26]. The use of GP modeling has another side benefit. As it calculates the confidence of a prediction, the user can confirm whether the number and location of measurement samples are sufficient, and suitable or not, being a great advantage from a practical viewpoint. In addition, since the GP can calculate the uncertainty of the estimation result, the user can confirm whether the number and location of measurement samples are sufficient and suitable or not.

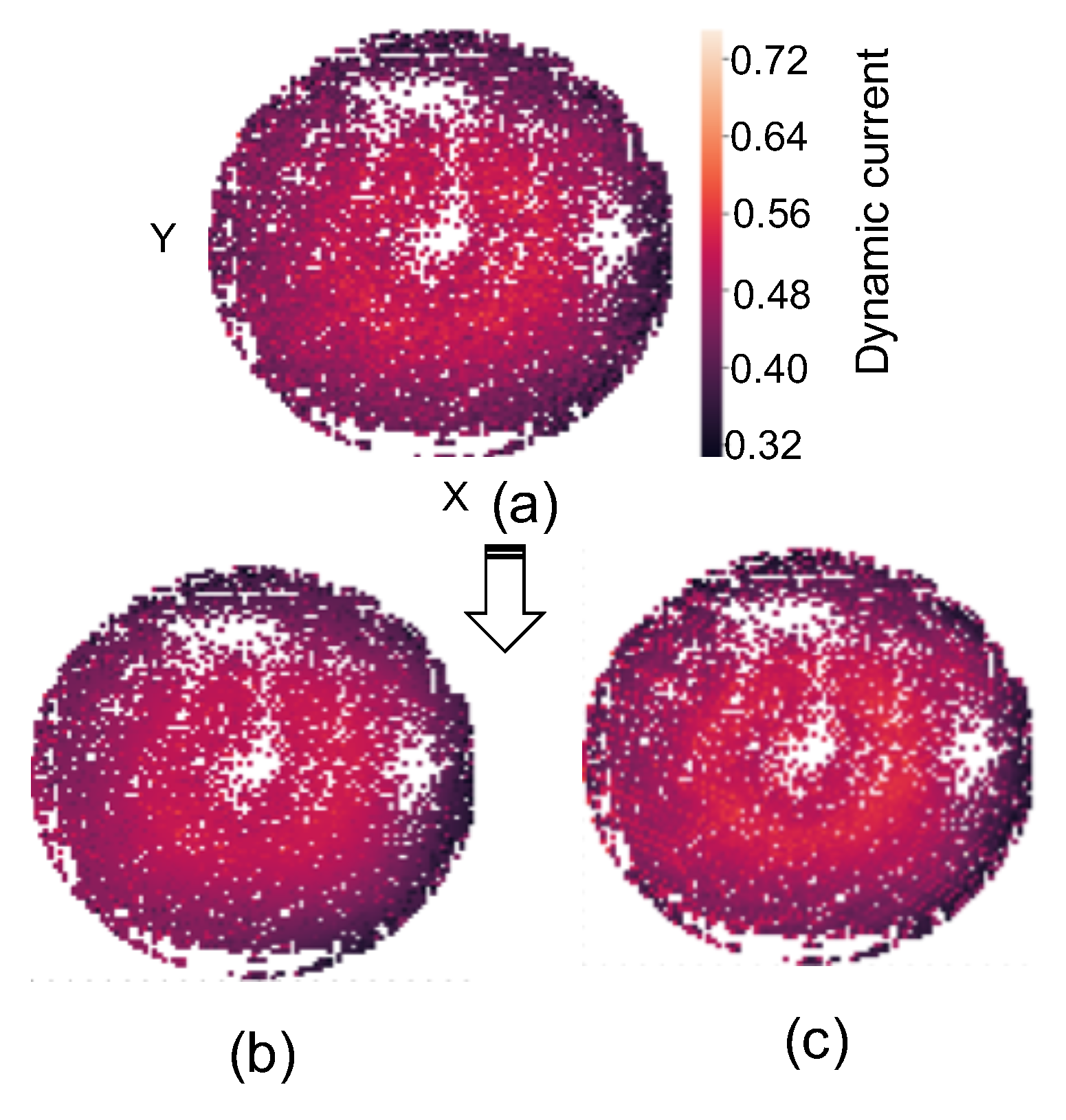

Figure 1 presents an experimental analysis in the form of a heat map, showing the full measurement results for a wafer of a 28 nm analog/RF device with a 10% estimation. The figure includes three heat maps (a, b, c), where (a) represents the actual measured data, while (b) and (c) show the predicted data using a virtual probe and Gaussian process regression (GPR), respectively. In both cases, 10% of the samples are used to estimate the remaining 90% of the unmeasured samples. It is evident from the figure that both VP and GPR effectively address and accurately predict the unknown measured data with high accuracy and minimal error.

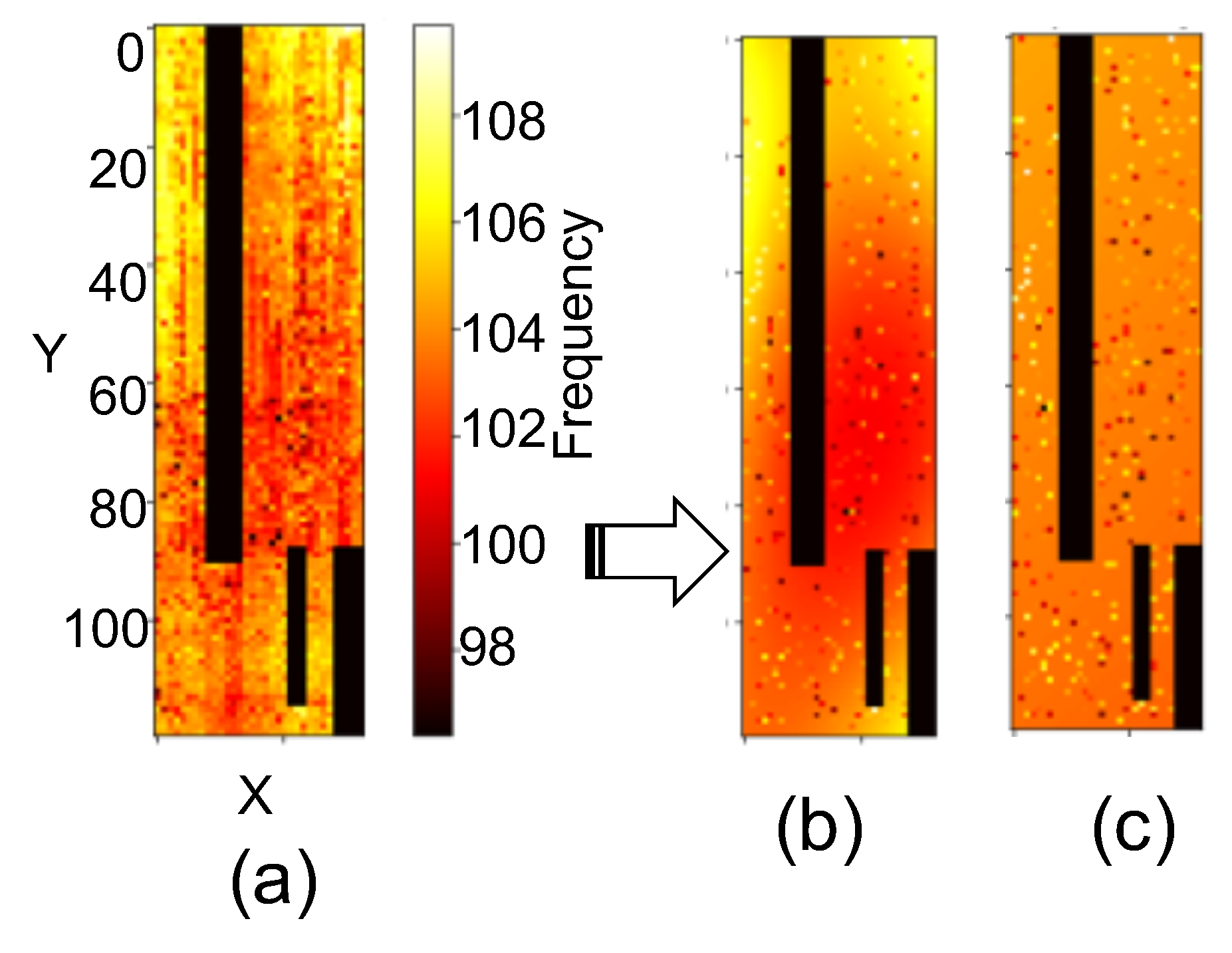

Figure 2 shows a similar experiment with delay information in look-up tables (LUTs) using ring oscillators (ROs). The figure includes three heat maps (a, b, c), where (a) represents the actual measured data, while (b) and (c) show the predicted data using a 10% virtual probe and 10% training data for the Gaussian process regression (GPR), respectively, The figure shows the similar trend on

Figure 1 and in both cases VP and GPR effectively address as well as accurately predict the unknown measured data with high accuracy and minimal error.

The VP technique exploits the sparsity of frequency-domain components in spatial process variation for prediction. Due to the gradual nature of process variation in FPGAs and wafers, high-frequency components approach zero, allowing seamless integration with fingerprinting techniques. The method’s effectiveness is validated through silicon measurements on commercial FPGAs.

Unlike VP’s direct frequency-domain approach, GPR models spatial process variation as a probabilistic distribution using kernel-based correlation analysis. This technique effectively handles gradual variations through Gaussian process smoothing, making it ideal for probabilistic predictions. Experimental validation using commercial FPGAs and wafer analog/RF device data demonstrates the method’s effectiveness [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37].

However, when applying GPR, it is most important to select the best kernel function, but the appropriate kernel function for LSI testing is not well understood. Since there is no effective method for investigating kernel function selection, this study applies GPR to mass production LSI test data, experimentally compares a large number of kernel functions, and identifies the best kernel function. Furthermore, based on this evaluation, we demonstrate that estimation accuracy can be further improved by using multiple kernel functions with high estimation accuracy. The hybrid or mixture kernels are proposed in [

35,

36,

37,

38] where different modes of mixing and combining are explained. In

Section 3, sum of two product kernels

achieves the best result than any individual kernel.

Most importantly, even when one single kernel or composite kernel function works well, it may not outperform others in different datasets with similar performance. Additionally, composite or adaptive kernels with too many parameters may suffer from overfitting issues. This study aims to determine a custom adaptation based on estimation prediction confidence to select the top two candidates for adaptation with dynamic weight adjustment based on the estimation confidence, instead of using fixed-weight adaptive kernels. Unlike typical hybrid or mixture kernels proposed in [

35,

36,

37,

38], this approach determines the weight of each kernel based on their difference in confidence levels. After an exhaustive analysis of various kernel functions across all possible combinations, using actual industry production data and real silicon data, it was observed that the proposed custom adaptive kernel consistently outperformed across two different datasets.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 provides an overview of GP-based modeling for wafer and FPGA process variations.

Section 3 details the kernel function and proposed custom adaptive kernel strategies. Section presents a quantitative evaluation of the proposed custom kernel approach compared to conventional approaches. Finally,

Section 5 offers the conclusion.

2. Gaussian Process Regression for Semiconductor Reliability

A Gaussian distribution is a type of probability distribution for continuous variables, also known as a normal distribution. In this distribution, the mean, mode, and median are identical, and the distribution is symmetric around the mean. Since it is continuous rather than discrete, the distribution is represented as a smooth curve rather than a histogram. The probability density function of the Gaussian distribution is given by:

where

represents the expected value (mean) and

denotes the standard deviation.

The probability distribution treats the function as a random variable, creating a probabilistic model that predicts y for a given input x. When is defined, the outputs for inputs follow a Gaussian process. The joint distribution of at any set of points is Gaussian. This property holds true even as N approaches infinity, making a Gaussian process an infinite-dimensional Gaussian distribution.

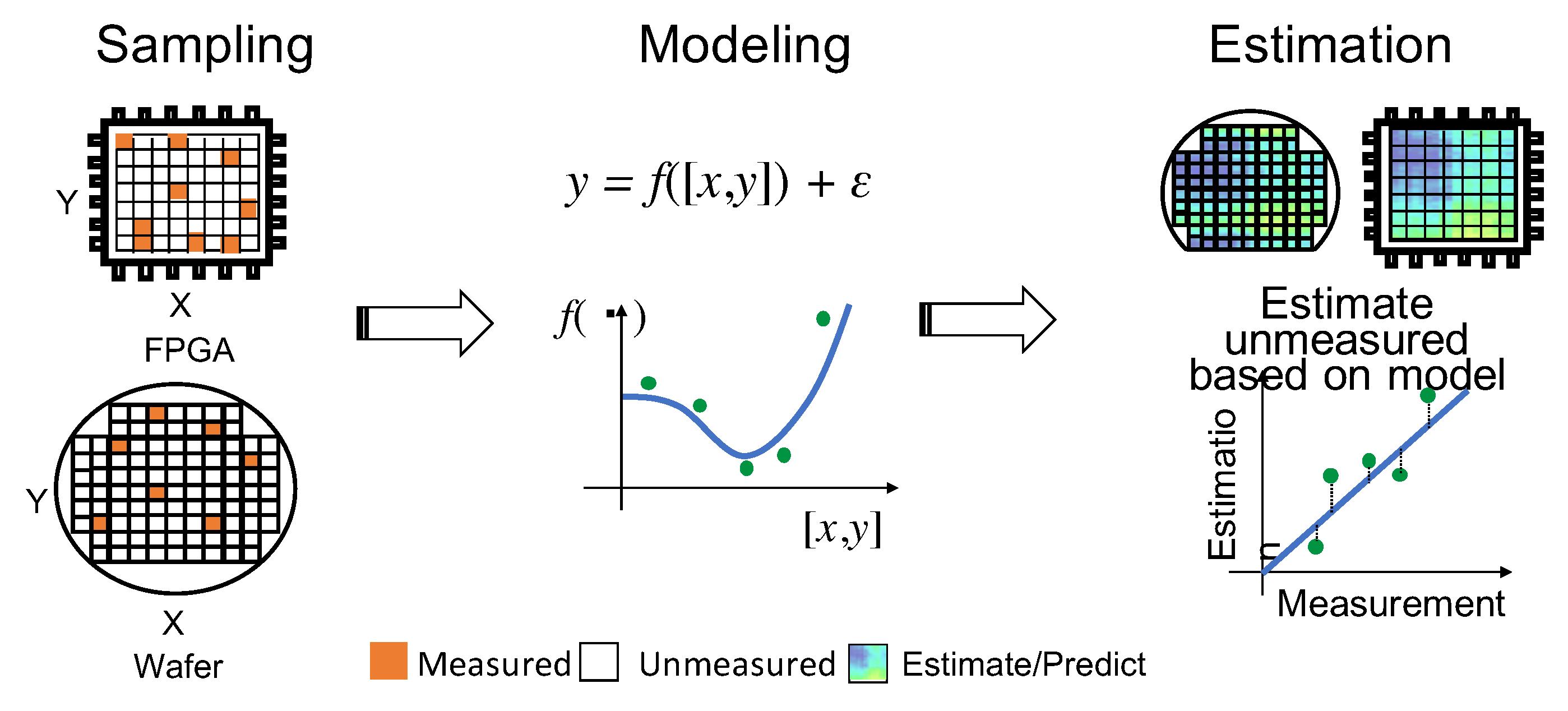

As illustrated in

Figure 3, Gaussian process methods are used to model the relationship between input

X and output

Y. This relationship is expressed mathematically as:

where

represents the model’s noise or uncertainty. Data collected from the Wafer and FPGA are used to establish this relationship. Using this model, we can estimate the new output

for both Wafer and FPGA is the new input data

. The model is constructed as a function of the probability distribution using Bayesian inference.

As mentioned earlier, the semiconductor industry is pursuing methods to improve quality without increasing test costs, or to reduce costs while maintaining quality. Particularly for the latter, wafer-level characteristic modeling methods based on statistical algorithms yield good results. This model uses Gaussian process regression for prediction, creating a prediction model based on limited sample measurements on the wafer surface or FPGA lookup table to predict the entire wafer surface and entire lookup tables.

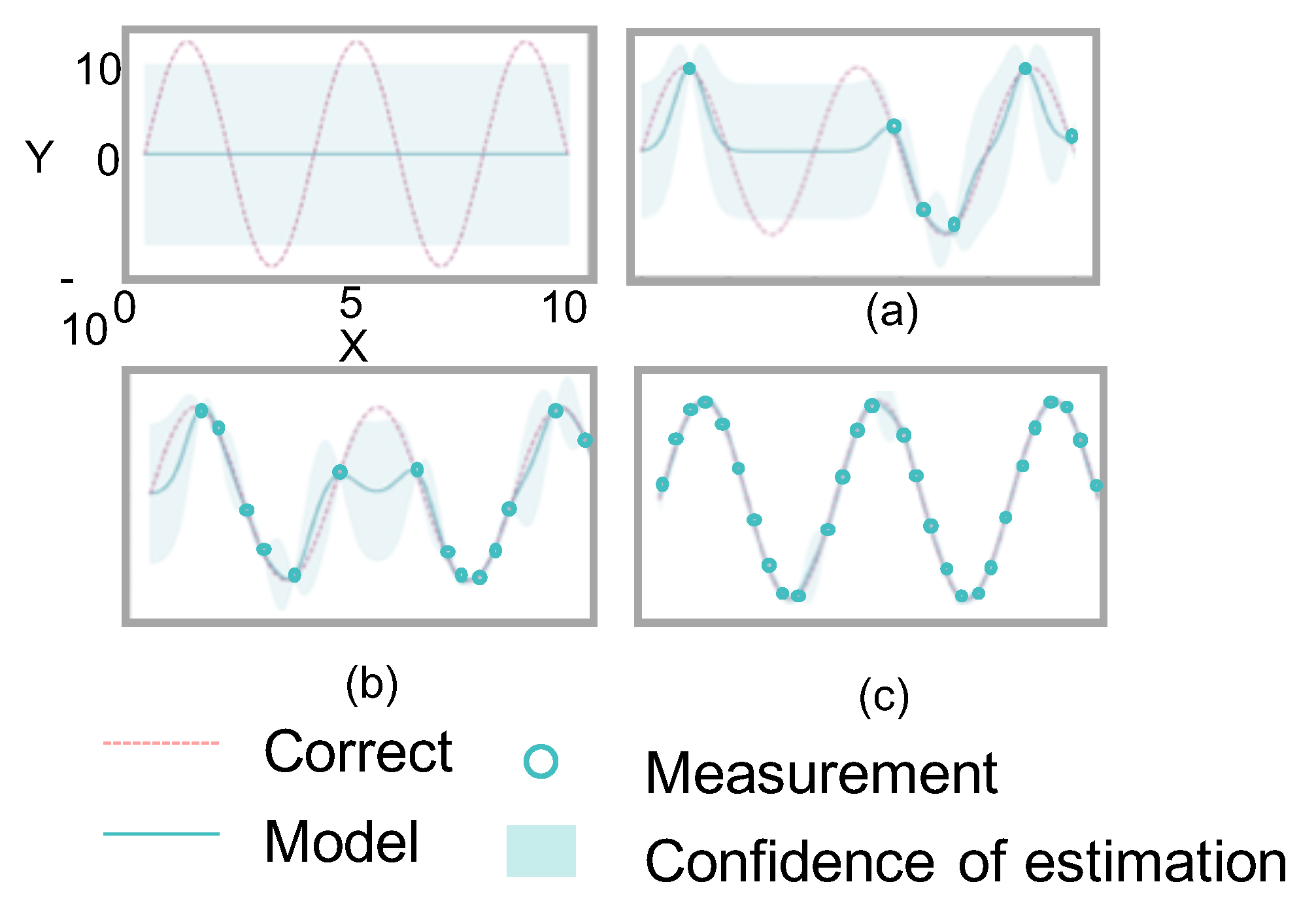

Figure 4a–c illustrate how the model the relationship between input x and output y. Data D is utilized to model the relationship. The new output y(n+ 1) for the new data x (n+ 1) is estimated based on the model. The model is calculated as a function of the probability distribution with the Bayesian manner.

3. Proposed Custom Adaptive Kernel Approach

The GP-based regression employs kernel functions from the GPy [

32] framework to model and predict the characteristics of LSIs and FPGAs.

This method learns from the measurement results of a small number of LSIs on the wafer and FPGA delay information. After the learning phase, it determines two functions: , which relates to the wafer LSI coordinates, and , which relates to FPGA delay information in look-up tables (LUTs) using ring oscillators (ROs). These functions estimate the characteristics of unmeasured LSIs and FPGAs, significantly reducing measurement time and costs.

Let represent the wafer surface coordinates, and represent the FPGA LUT delay information. Similarly, define and as the respective measurement values to be predicted.

The training and test datasets are defined as follows:

For FPGA data:

where

and

.

Using the predictive models

and

obtained from GPR, the predicted values for the test datasets are:

3.1. Hybrid or Mixture Kernel Strategy

The Hybrid or Mixture Kernel approach combines multiple kernel functions, each tailored to specific data characteristics, into a composite kernel. This strategy traditionally uses fixed weights for individual kernels, expressed as:

where

are the individual kernels, and

are their static weights with

. However, such static weighting lacks adaptability to varying data properties, limiting robustness and flexibility.

To address this, an adaptive hybrid kernel strategy where weights are dynamically adjusted based on kernel performance metrics.

3.1.1. Adaptive Kernel Strategy

The adaptive kernel strategy is designed to enhance GPR’s robustness and adaptability for semiconductor data, such as wafer variations and FPGA delays. In this case, we introduce two of the adaptive strategies first we adapt three kernel with jitter in the 4th while the second approach consider top two candidates with adaptive weights. The data

works with the kernel function

to determine the confidence of the error

to identify the candidates. This strategy dynamically selects or combines kernel functions based on the data’s statistical properties, enhancing model accuracy across different production environments. The kernel combination involves forming a composite kernel by weighting multiple kernels:

where

,

, and

are dynamically adjusted. It improves predictive accuracy by adjusting kernel selection and weighting to match data characteristics, enhancing model robustness across varied datasets, and reducing costs in semiconductor testing by minimizing error rates. A composite kernel is then formed by weighting multiple kernels according to:

where

,

, and

are dynamically adjusted weights.

The composite kernel

is defined as a weighted sum of individual kernels:

where

represents individual kernels (Exponential, MLP, RBF, and Matérn32) and

are adaptive weights. Let

represent their respective performance metrics, and

denote the performance difference between kernels

i and

j. Given a threshold

for significant performance difference, the weights are determined as:

where

and

are indices of kernels with highest and second-highest performance metrics. The final composite kernel is expressed as:

subject to the constraints:

On the other hand, a more simple adaption with only two kernels can also be defined where the kernel combination involves forming a composite kernel by weighting the top two kernels and including a jitter kernel as the third component:

where

,

, and

are dynamically adjusted weights. Here,

(jitter) ensures numerical stability. In this case he composite kernel

is defined as a weighted sum of individual kernels:

where

represents individual kernels (Exponential, MLP, and jitter) and

are adaptive weights. Let

represent their respective performance metrics, and

denote the performance difference between kernels

i and

j. Given a threshold

for significant performance difference, the weights are determined as:

subject to the constraints:

The final composite kernel is expressed as:

3.2. Propose Custom Adaptive Model

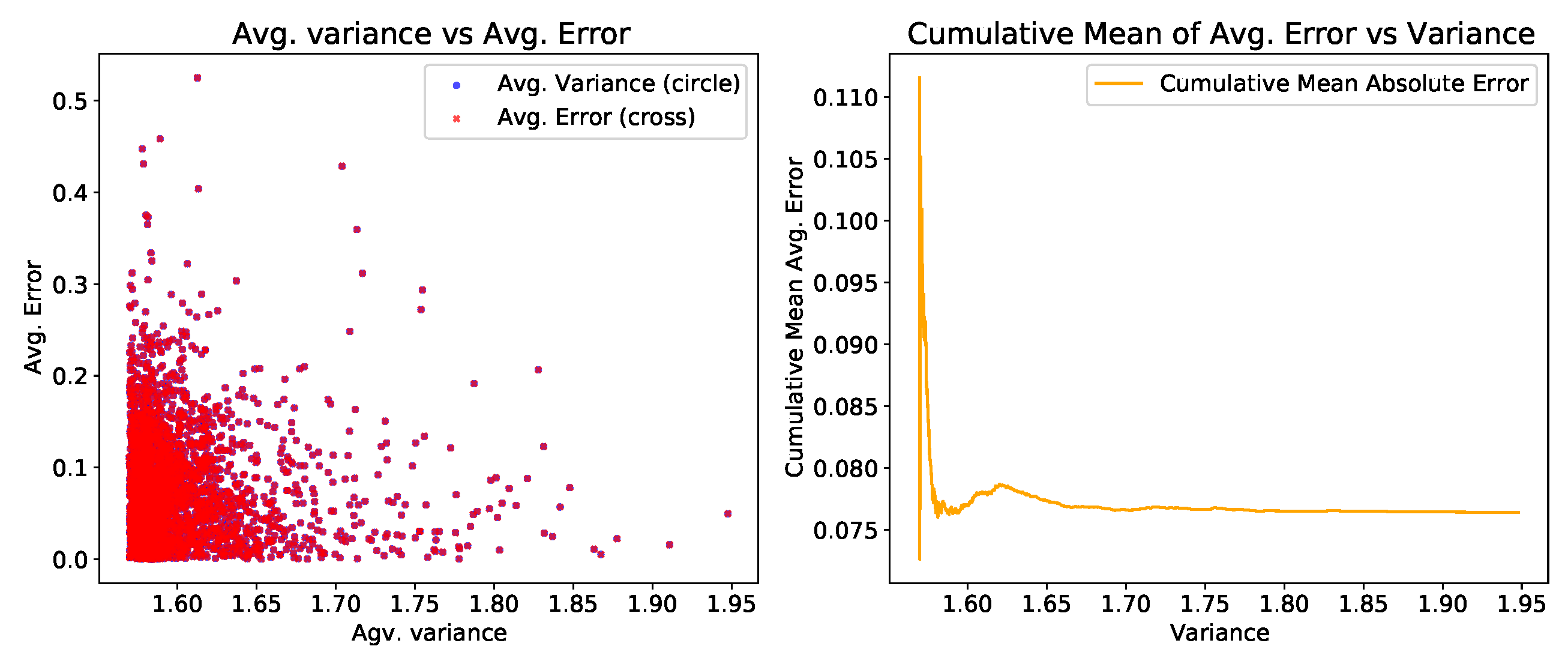

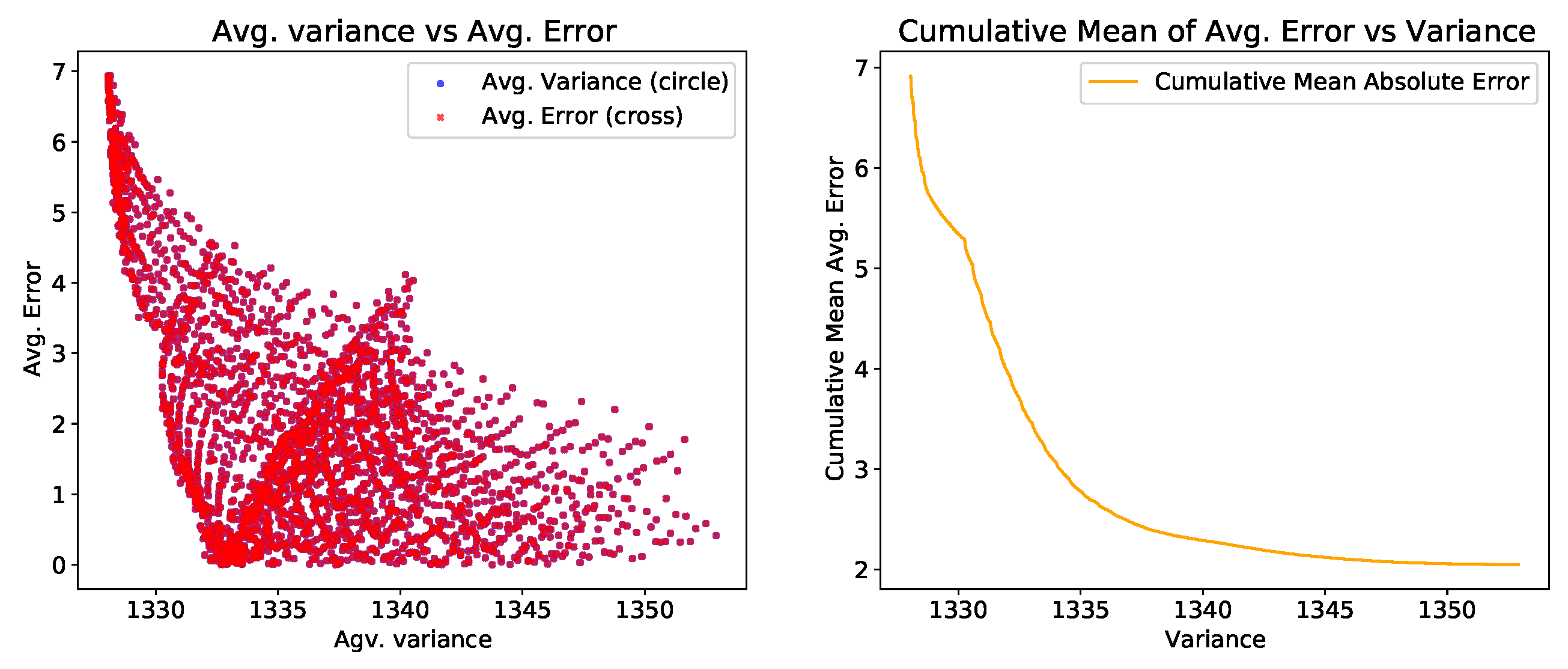

Before discussing the proposed custom adaptive strategy, we first analyze the correlation between variance and average error, as illustrated in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 where variance vs. average error scatter plot and cumulative mean of avg. error vs variance are illustrated for Matern52 and Linear Kernel respectively. In both figures, Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) is utilized to predict the input data using randomly selected 10% of the data for training, with error calculations as defined in

Section 4. The “variance vs. avg. error scatter plot” and “cumulative mean of average error vs. variance” highlight this relationship in different scenarios. In the case of the Matern-52 kernel, the error remains consistently low, with the cumulative trend exhibiting a slight increase as variance grows. The scatter plot demonstrates a weak positive trend where higher variance corresponds to slightly lower errors. For the linear kernel, where the prediction uncertainty is higher, the correlation exhibits a stronger negative trend. In both cases, regardless of the kernel choice, the negative correlation establishes that lower variance is associated with lower error. A similar trend is also examined in wafer data. We examined a negative correlation between the cumulative average error and the predictive variance. Although in some cases, such as for certain wafer and FPGA paths, we observed a positive correlation for some kernels, the overall correlation averaged across the datasets was found to be negative in both cases.

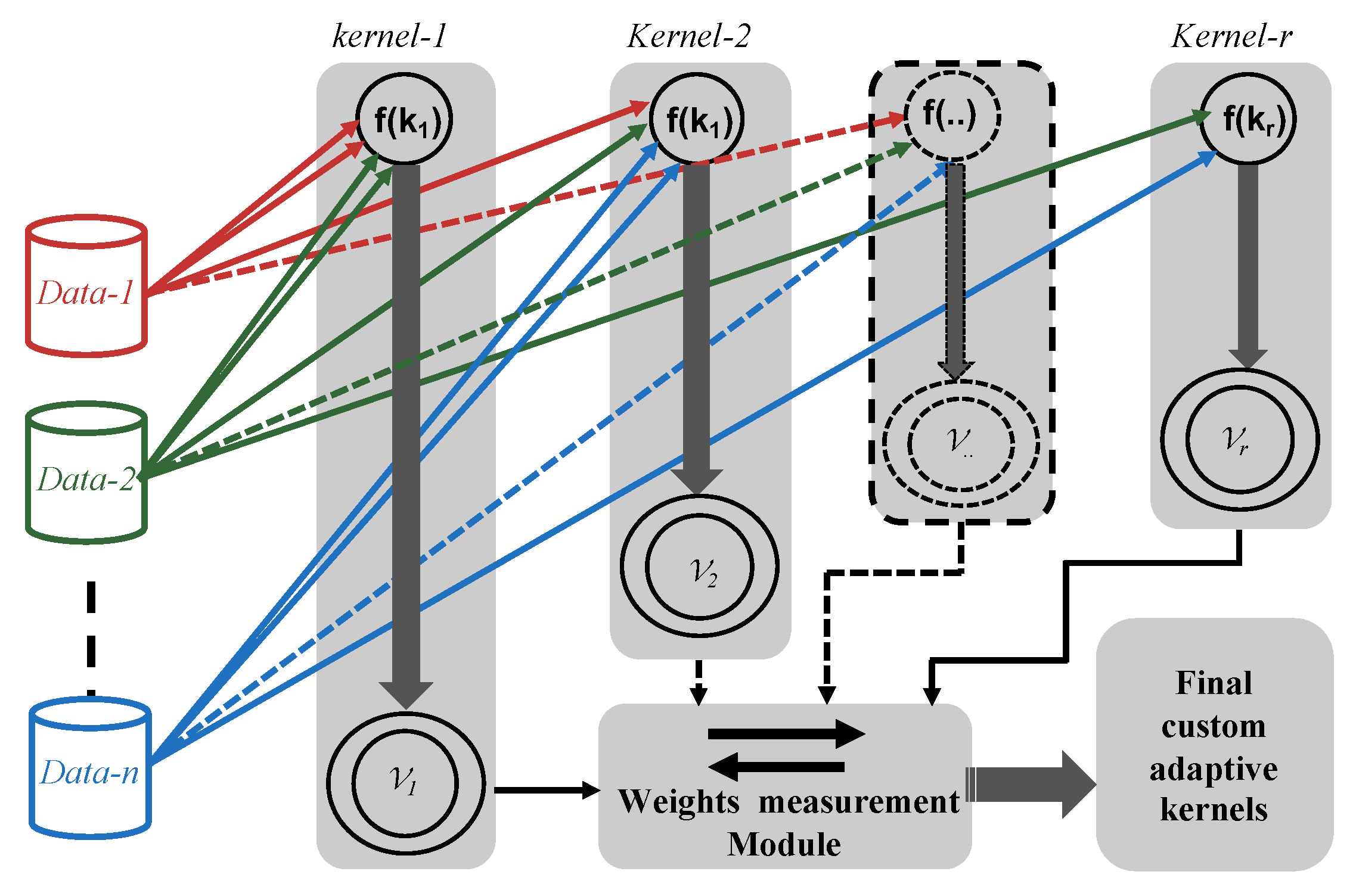

Considering this relationship, the proposed custom adaptive strategy is depicted in

Figure 7. The figure illustrates how kernel weights are adapted based on confidence measurements derived from the variance of predictions. In this approach, the adaptive kernel weights are calculated based on predicted variance instead of during the estimation process.

Figure 7 presents the different datasets

with different kernel functions

. The Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) estimates the variance

. for each kernel function. From these calculations, the top two candidates

and

are selected based on the lowest average variance among all kernels.

The weights

and

are defined to satisfy the following condition:

where the weights are assigned based on the difference in the variances

and

:

The weight

is calculated as:

where

is a scaling factor to control the impact of the variance difference on the weight.

Similarly,

is given by:

Here if , then and as the variance difference increases, increases if and decreases if . The smaller the variance of compared to , the more dominates.

This approach ensures that the kernel with higher confidence receives greater weight, reflecting its importance in the combined kernel function. The proportional adjustment of and accommodates scenarios where one kernel significantly outperforms the other in terms of variance.

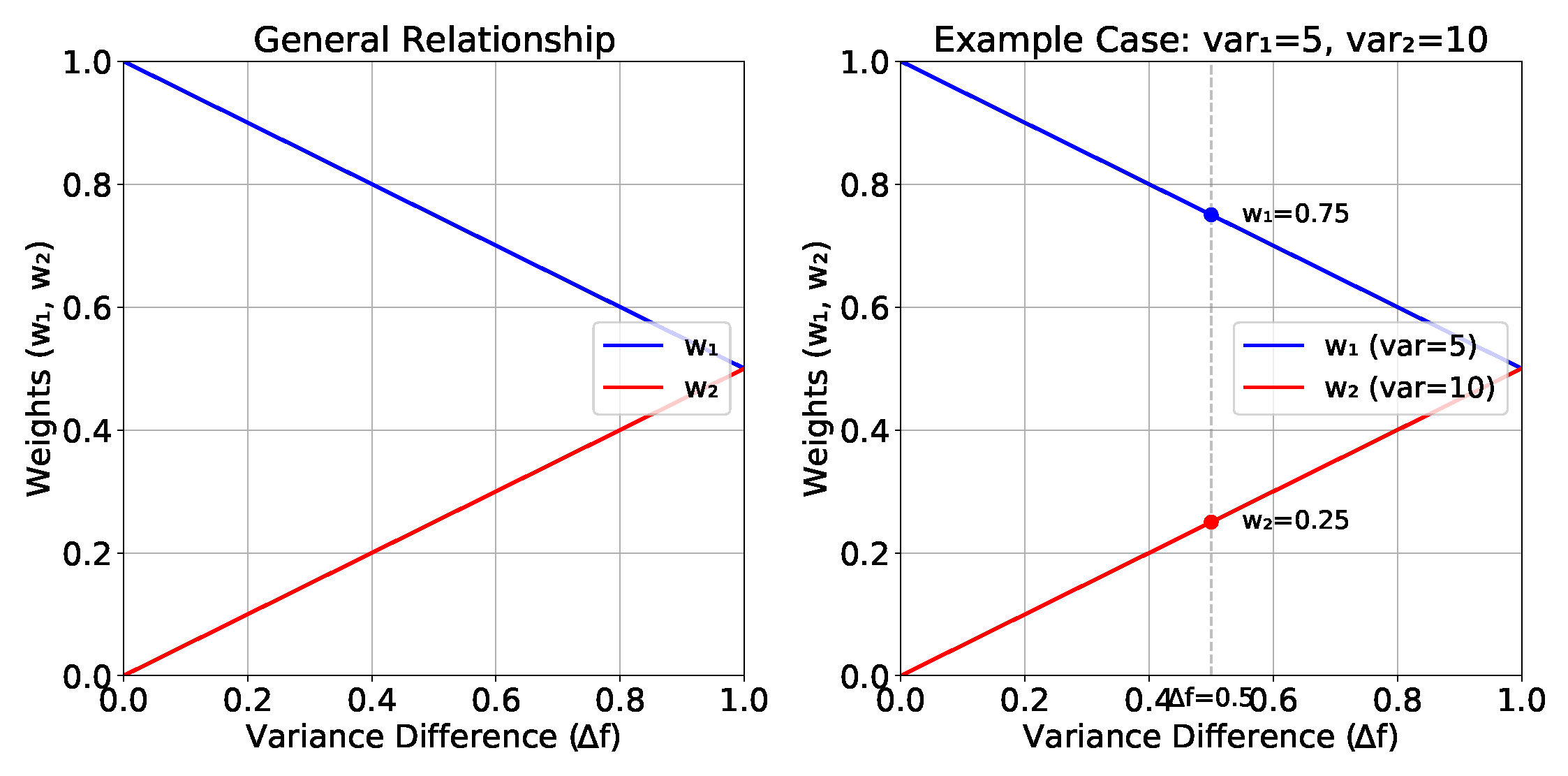

Figure 8 illustrates the relationship between

,

, and the variance difference

. It presents a general graph and another part demonstrating how the values are calculated and estimated with two variances, 10 and 5. According to the example in

Figure 8, the weights

and

are calculated as 0.75 and 0.25, respectively.

The proposed weighting mechanism adjusts and based on the variance difference between two kernels. The hypothesis provides a robust framework for assigning weights, ensuring that kernels with higher variance contribute more to the combined kernel function.

4. Experimental Result

In this study, we conducted experiments in two different environments for two data types. A Linux workstation with Debian on an Intel Core i7 processor and 32 GB memory is used for the wafer data. On the other hand, a Windows 11 workstation with AMD architecture and 16 GB memory is used for the FPGA data.

Table 1 shows the list of kernels used in each method and the proposed method.

4.1. Experimental Setup

The detailed estimation methodology of the existing work and the proposed environment setup, including datasets for the FPGA and wafer data, the kernel list used, the framework, and the calculation of estimation errors, are explored in this section. The details about the all above are as follows:

4.1.1. Wafer Data

For wafer data, we conducted experiments using an industrial production test dataset of a 28 nm analog/RF device. Our dataset contains 150 wafers from six lots, each lot contains 25 wafers and a single wafer featuring approximately 6,000 devices under test (DUTs). In this experiment, we utilized a measured characteristic for an item of the dynamic current test, A heat map of the full measurement results for the first wafer of the sixth lot is displayed in

Figure 1(a) and

Figure 9. For ease of experimentation, the faulty dies were removed from the dataset. In the data set, there are 16 sites in a single touchdown. However, in this experiment, the site information is not considered separately during the training phase. Although the data comes from a multisite environment, all 16 sites are treated as a single entity because the source data does not show any discontinuous changes for each site as shown in

Figure 1(a) and

Figure 9

4.1.2. FPGA Data

For FPGA data, we conducted experiments using measurements using the Xilinx Artix-7 FPGA. In this experiment, 10 FPGAs (FPGA-01 to FPGA-10) were used. An on-chip measurement circuit has been implemented using 7-stages (i.e., 7 LUTs) in a Configurable Logic Block (CLB). The Ring Oscillator (RO) is based on XNOR or XOR logic gates. By keeping the same internal routing, logic resources, and structure for each RO placed in a CLB, the frequency variation caused by internal routing differences can be minimized. A total of

3,173 ROs were placed on a geometrical grid of

(excluding the empty space of the layout) through hardware macro modeling using the Xilinx CAD tool, Vivado [

8,

9].

Figure 2(a) shows a single path’s measured frequency heat-map. This style is followed to cover the total layout of the FPGA. The Artix-7 FPGA has 6-input LUTs, which create a total of 32 (

) possible paths for XNOR- and XOR-based RO configurations (path-01 to path-32). In total, to complete the exhaustive fingerprint (X-FP) measurement, 32 fingerprint measurements were conducted for all the 32 paths.

4.1.3. GPR Kernel

We use all supported kernels by the GPy framework, along with the proposed hybrid and adaptive kernels, for both wafer-level and FPGA-based data.

4.1.4. Estimated Prediction Error

To quantitatively evaluate the modeling accuracy, we defined the error (

) between the correct (

) and the predicted mean (

) normalized using the maximum and minimum values of

as follows:

where

indicates the range between the minimum and maximum values of the fully measured characteristics.

4.1.5. Experimental analysis

Table 2 and

Table 3 shows the detailed evaluation of 150 wafers of six lots and 32 paths of 10 FPGAs respectively. Actual industry production data and actual silicon data are used in this evaluation. From the table it shows that wafer data’s smooth patterns make it suitable for both Exponential and MLP kernels, while FPGA delay’s complexity favors the Exponential kernel. MLP kernel’s performance on FPGA data may be hindered by high sensitivity to hyperparameters, especially in higher dimensions.

The Exponential kernel is consistently strong across tasks, with vRBF, GridRBF, and ExpQuad performing well on wafer data, and RatQuad and Matern52 on FPGA data. White and Linear kernels under-perform on both, suggesting non-linearity is essential. The wafer task is generally easier, while FPGA delay prediction shows higher variability, indicating greater challenge.

For wafer data, Exponential and MLP kernels are suitable, with vRBF and ExpQuad as alternatives. For FPGA delays, the Exponential kernel is best, with RatQuad and Matern52 also worth considering. Avoid White and Linear kernels for both tasks.

The Hybrid kernel and the proposed adaptive kernels also perform well while in the proposed outperforms from all the case in terms of average and most of the case individual and lot wise average for both the wafer and FPGAs.

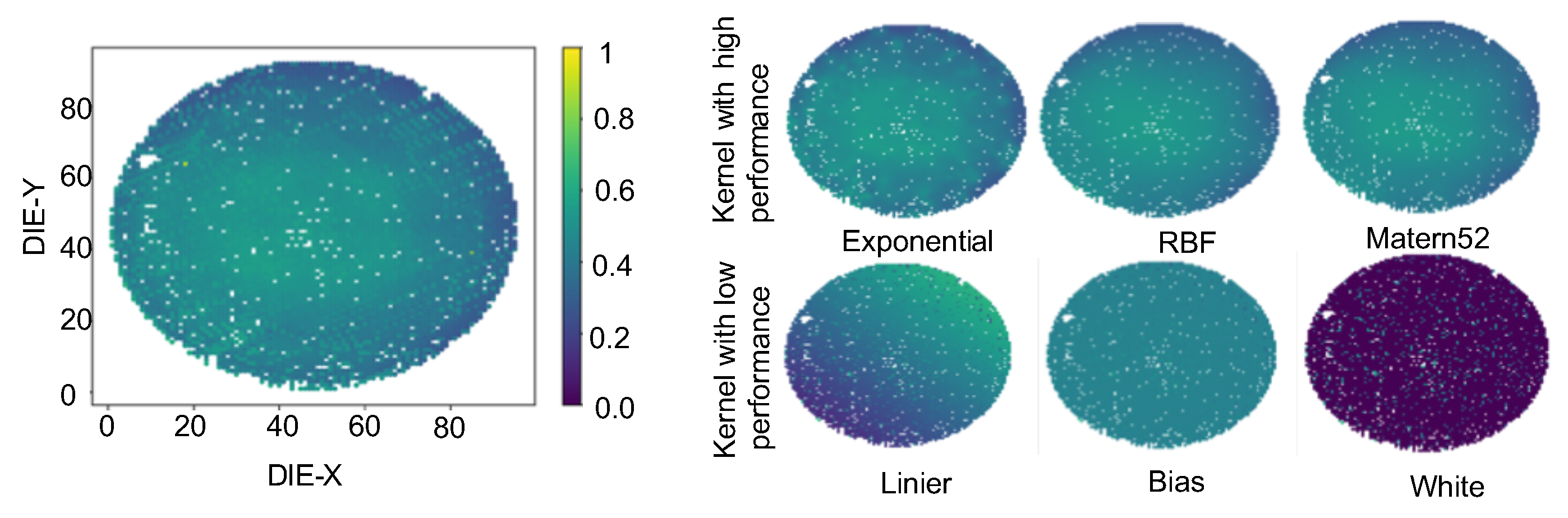

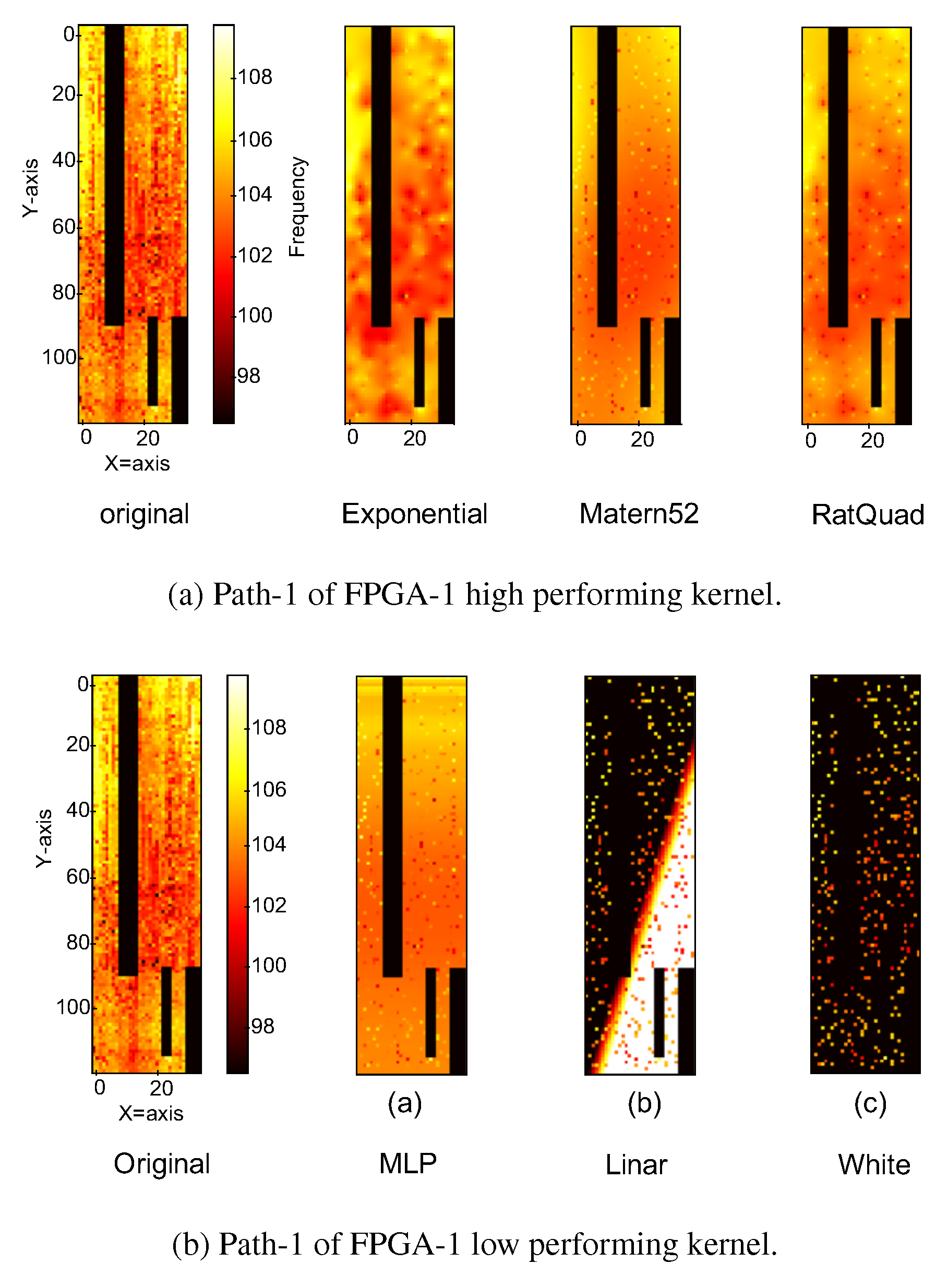

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 show the heat maps comparison for the wafer and FPGA, respectively. In the case of the wafer in

Figure 10, the first wafer of the third lot is explored, while in the case of FPGA in

Figure 11, the figure depicts the first path of the first FPGA with three good-performing and three bad-performing kernels.

In the wafer data, the exponential RBF and Matérn52 kernels very closely reproduce the original die, while in the case of bad performance, the linear, bias, and white kernels are also depicted in the corresponding heat maps. On the other hand, in

Figure 11, the heat map of FPGA data shows that the exponential, Matérn, and TatQuad kernels are performing well, while MLP, linear, and white kernels are not performing well. From the figure, it is also clearly shown that in both cases of FPGAs and wafer data, the good-performing kernels are reflected in their corresponding heat maps as well.

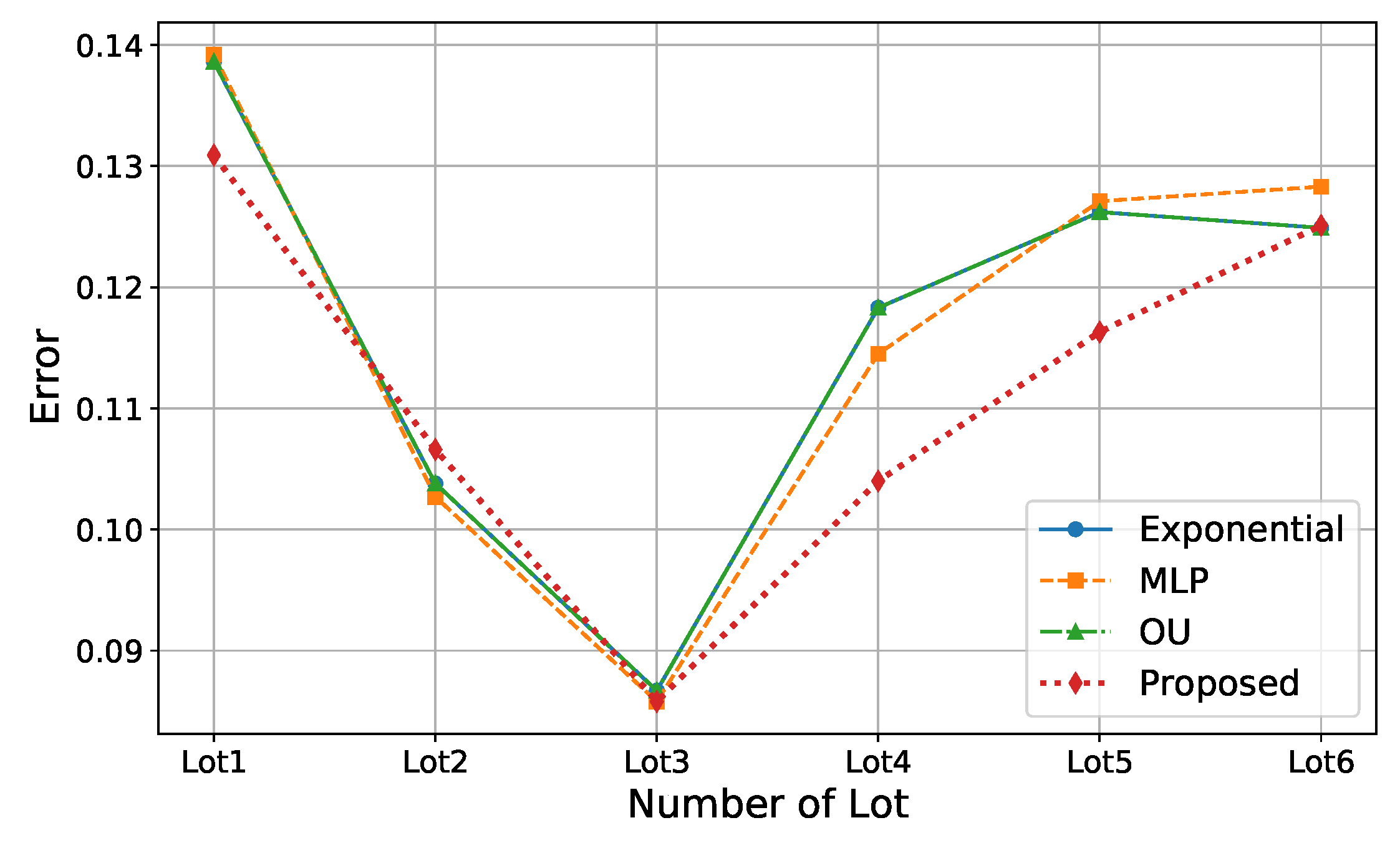

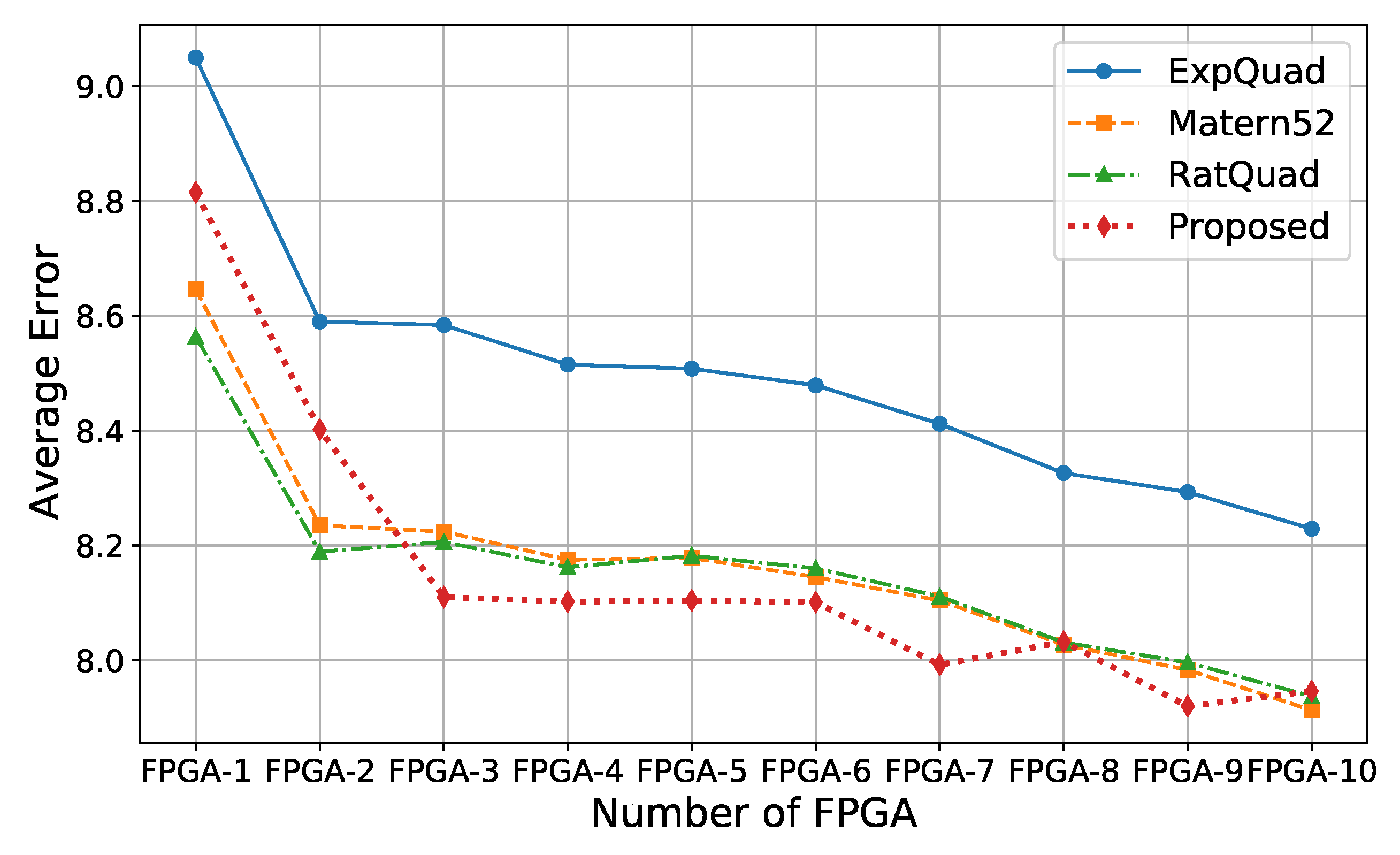

The comparison of the top four performing kernels in both cases of wafer and FPGAs is depicted with a line graph in

Figure 10 and

Figure 12, respectively. To find a common performer in both cases, only Proposed is outperforming in the two different environments.

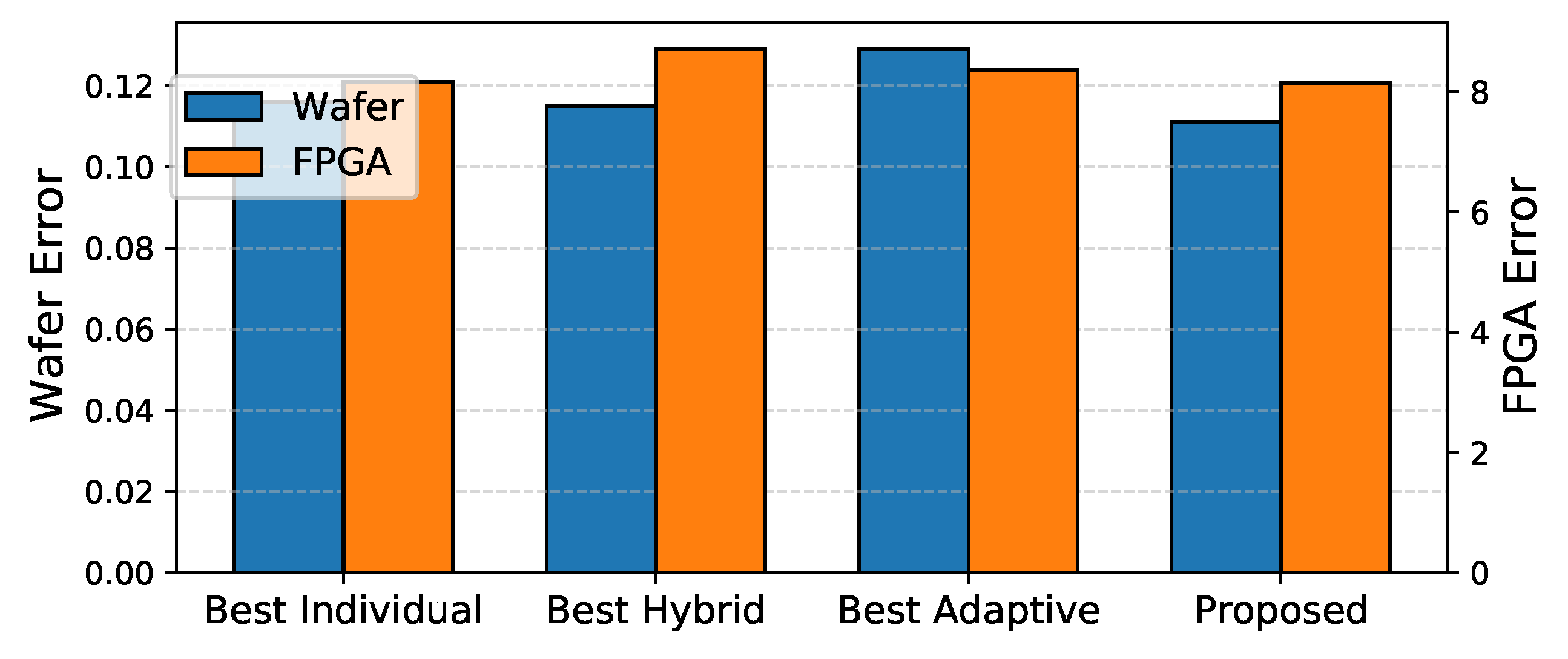

Finally,

Figure 13 illustrates the comparison of Wafer and FPGA accuracy across different kernel configurations to explore significant insights. For wafer accuracy measurements, the hybrid kernel achieves a low error rate of 0.115, which is comparable to the best kernel’s error rate of 0.116. However, the

proposed custom adaptive kernel demonstrates superior performance with the lowest Wafer error rate of 0.111.

In the FPGA dataset analysis also shown in

Figure 13, the single best kernel slightly outperforms both the adaptive and hybrid kernels in baseline comparisons. Nevertheless, the

Proposed custom adaptive kernel again demonstrates superior performance with the lowest FPGA error rate of 8.15, followed closely by the best kernel at 8.163 and the

adaptive kernel with an error rate of 8.36. The hybrid kernel, however, exhibits notably higher FPGA error rates, indicating suboptimal performance for FPGA-based applications.

In the comprehensive analysis across both datasets, the Proposed kernel emerges as the most effective solution, consistently achieving superior performance. While the hybrid kernel demonstrates competitive accuracy in wafer-based applications, its significantly elevated FPGA error rate renders it unsuitable for universal deployment across both platforms.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated the application of Gaussian Process Regression (GPR), a state-of-the-art technique, for wafer-level variation modeling and FPGA delay prediction, with an emphasis on kernel function selection. Through exhaustive analysis, various kernel functions, including hybrid and adaptive kernels, were evaluated using wafer-level industry production data and silicon measurements from FPGAs. While no single kernel function consistently excelled across all datasets, our proposed custom adaptive kernel with a weighted kernel approach demonstrated superior versatility and reliability. This novel methodology enhances the predictive performance and adaptability of GPR, addressing limitations in current state-of-the-art applications. By offering robust accuracy across diverse scenarios, this approach presents a practical and innovative solution for optimizing semiconductor testing and production processes, with the potential to significantly reduce costs and improve efficiency. These contributions represent a meaningful advancement in leveraging GPR for semiconductor manufacturing and related domains.

Author Contributions

Riaz-ul-Haque Mian: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing – Original Draft Preparation, Project Administration Foisal Ahmed: Data Curation, Validation, Writing – Review & Editing. Yoshito Hagihara: Experiment, Writing Yamane Souma: Validation, Formal Analysis. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability Statement

This study utilized two datasets: 1. The FPGA dataset used in this study can be made available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author. Researchers requesting this dataset must provide a clear research purpose and will need to agree to terms of use. 2. The second dataset, which consists of industry production data, is subject to a non-disclosure agreement (NDA). Access to this dataset can be facilitated through direct communication with the industry contact, as provided by the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Wan, Z.; Yu, B.; Li, T.Y.; Tang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Raychowdhury, A.; Liu, S. A survey of fpga-based robotic computing. IEEE Circuits and Systems Magazine 2021, 21, 48–74. [CrossRef]

- Riaz-ul-haque, M.; Michihiro, S.; Inoue, M. Hardware–Software Co-Design for Decimal Multiplication. Computers 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Nery, A.S.; Sena, A.C.; Guedes, L.S. Efficient Pathfinding Co-Processors for FPGAs. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Symposium on Computer Architecture and High Performance Computing Workshops (SBAC-PADW), 2017, pp. 97–102.

- Shintani, M.; Mian, R.U.H.; Inoue, M.; Nakamura, T.; Kajiyama, M.; Eiki, M. Wafer-level Variation Modeling for Multi-site RF IC Testing via Hierarchical Gaussian Process. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Test Conference (ITC), 2021, pp. 103–112.

- Violante, M.; Sterpone, L.; Manuzzato, A.; Gerardin, S.; Rech, P.; Bagatin, M.; Paccagnella, A.; Andreani, C.; Gorini, G.; Pietropaolo, A.; et al. A new hardware/software platform and a new 1/E neutron source for soft error studies: Testing FPGAs at the ISIS facility. IEEE Transactions on Nuclear Science 2007, 54, 1184–1189. [CrossRef]

- Bahukudumbi, S.; Chakrabarty, K. Wafer-level testing and test during burn-in for integrated circuits; Artech House, 2010.

- Garrou, P. Wafer level chip scale packaging (WL-CSP): An overview. IEEE Transactions on Advanced Packaging 2000, 23, 198–205. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.; Shintani, M.; Inoue, M. Accurate Recycled FPGA Detection Using an Exhaustive-Fingerprinting Technique Assisted by WID Process Variation Modeling. IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems 2021, 40, 1626–1639. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.; Shintani, M.; Inoue, M. Low Cost Recycled FPGA Detection Using Virtual Probe Technique. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Test Conference in Asia (ITC-Asia), 2019, pp. 103–108.

- Ahmed, F.; Shintani, M.; Inoue, M. Feature engineering for recycled FPGA detection based on WID variation modeling. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE European Test Symposium (ETS). IEEE, 2019, pp. 1–2.

- Wang, L.C. Experience of Data Analytics in EDA and Test—Principles, Promises, and Challenges. IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems 2017, 36, 885–898. [CrossRef]

- Stratigopoulos, H.G. Machine learning applications in IC testing. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of IEEE European Test Symposium, 2018.

- Shintani, M.; Inoue, M.; Nakamura, Y. Artificial Neural Network Based Test Escape Screening Using Generative Model. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of IEEE International Test Conference, 2018, p. 9.2.

- Huang, K.; Kupp, N.; John M., Jr., C.; Makris, Y. Handling Discontinuous Effects in Modeling Spatial Correlation of Wafer-level Analog/RF Tests. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of IEEE Design Automation and Test in Europe, 2013, pp. 553–558.

- Reda, S.; Nassif, S.R. Accurate Spatial Estimation and Decomposition Techniques for Variability Characterization. IEEE Transactions on Semiconductor Manufacturing 2010, 23, 345–357. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Rutenbar, R.R.; Blanton, R.D. Virtual probe: A statistically optimal framework for minimum-cost silicon characterization of nanoscale integrated circuits. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of IEEE/ACM International Conference on Computer-Aided Design, 2009, pp. 433–440.

- Zhang, W.; Li, X.; Rutenbar, R.A. Bayesian Virtual Probe: Minimizing Variation Characterization Cost for Nanoscale IC Technologies via Bayesian Inference. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of ACM/EDAC/IEEE Design Automation Conference, 2010, pp. 262–267.

- Zhang, W.; Li, X.; Liu, F.; Acar, E.; Rutenbar, R.A.; Blanton, R.D. Virtual Probe: A Statistical Framework for Low-Cost Silicon Characterization of Nanoscale Integrated Circuits. IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems 2011, 30, 1814–1827. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Lin, F.; Hsu, C.K.; Cheng, K.T.; Wang, H. Joint Virtual Probe: Joint Exploration of Multiple Test Items’ Spatial Patterns for Efficient Silicon Characterization and Test Prediction. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of IEEE Design Automation and Test in Europe, 2014.

- Kupp, N.; Huang, K.; Carulli, Jr., J.M.; Makris, Y. Spatial correlation modeling for probe test cost reduction in RF devices. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of IEEE/ACM International Conference on Computer-Aided Design, 2012, pp. 23–29.

- Ahmadi, A.; Huang, K.; Natarajan, S.; John M., Jr., C.; Makris, Y. Spatio-Temporal Wafer-Level Correlation Modeling with Progressive Sampling: A Pathway to HVM Yield Estimation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of IEEE International Test Conference, 2014, p. 18.1.

- Zhang, W.; Li, X.; Liu, F.; Acar, E.; Rutenbar, R.A.; Blanton, R.D. Virtual probe: A statistical framework for low-cost silicon characterization of nanoscale integrated circuits. IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems 2011, 30, 1814–1827.

- Donoho, D.L. Compressed sensing. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 2006, 52, 1289–1306.

- Candes, E.J.; Wakin, M.B. An Introduction To Compressive Sampling. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine 2008, 25, 21–30. [CrossRef]

- Shintani, M.; Mian, R.U.H.; Inoue, M.; Nakamura, T.; Kajiyama, M.; Eiki, M. Wafer-level Variation Modeling for Multi-site RF IC Testing via Hierarchical Gaussian Process. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Test Conference (ITC), 2021, pp. 103–112.

- ul-haque MIAN, R.; NAKAMURA, T.; KAJIYAMA, M.; EIKI, M.; SHINTANI, M. Efficient Wafer-Level Spatial Variation Modeling for Multi-Site RF IC Testing. IEICE TRANSACTIONS on Fundamentals of Electronics, Communications and Computer Sciences 2023, pp. 1139–1150.

- Marinissen, E.J.; Singh, A.; Glotter, D.; Esposito, M.; Jr., J.M.C.; Nahar, A.; Butler, K.M.; Appello, D.; Portelli, C. Adapting to Adaptive Testing. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of IEEE Design Automation and Test in Europe, 2010, pp. 556–561.

- Gotkhindikar, K.R.; Daasch, W.R.; Butler, K.M.; Carulli, Jr., J.M.; Nahar, A. Die-level Adaptive Test: Real-time Test Reordering and Elimination. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of IEEE International Test Conference, 2011, p. 15.1.

- Yilmaz, E.; Ozev, S.; Sinanoglu, O.; Maxwell, P. Adaptive Testing: Conquering Process Variations. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of IEEE European Test Symposium, 2012.

- Shintani, M.; Uezono, T.; Takahashi, T.; Hatayama, K.; Aikyo, T.; Masu, K.; Sato, T. A Variability-Aware Adaptive Test Flow for Test Quality Improvement. IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems 2014, 33, 1056–1066. [CrossRef]

- Dempster, A.P.; Laird, N.M.; Rubin, D.B. Maximum Likelihood from Incomplete Data Via the EM Algorithm. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological) 1977, 39, 1–38.

- GPy. GPy: A Gaussian process framework in python. http://github.com/SheffieldML/GPy, since 2012.

- Xanthopoulos, C.; Huang, K.; Ahmadi, A.; Kupp, N.; Carulli, J.; Nahar, A.; Orr, B.; Pass, M.; Makris, Y., Gaussian Process-Based Wafer-Level Correlation Modeling and Its Applications. In Machine Learning in VLSI Computer-Aided Design; Elfadel, I.A.M.; Boning, D.S.; Li, X., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; pp. 119–173.

- Ahmadi, A.; Huang, K.; Natarajan, S.; Carulli, J.M.; Makris, Y. Spatio-temporal wafer-level correlation modeling with progressive sampling: A pathway to HVM yield estimation. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Test Conference. IEEE, 2014, pp. 1–10.

- Chang, C.; Chang, H.M.; Chiang, K. Study on Gaussian Process Regression to Predict Reliability Life of Wafer Level Packaging with cluster analysis. In Proceedings of the 2022 17th International Microsystems, Packaging, Assembly and Circuits Technology Conference (IMPACT), 2022, pp. 1–4.

- Chang, C.; Zeng, T. A hybrid data-driven-physics-constrained Gaussian process regression framework with deep kernel for uncertainty quantification. Journal of Computational Physics 2023, 486, 112129. [CrossRef]

- Suwandi, R.C.; Lin, Z.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Z.; Cheng, L.; Yin, F. Gaussian Process Regression with Grid Spectral Mixture Kernel: Distributed Learning for Multidimensional Data. In Proceedings of the 2022 25th International Conference on Information Fusion (FUSION), 2022, pp. 1–8.

- Bu, A.; Wang, R.; Jia, S.; Li, J. GPR-Based Framework for Statistical Analysis of Gate Delay under NBTI and Process Variation Effects. Electronics 2022, 11, 1336. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).