1. Introduction

This study stems from the evidence of a lack of cognitive and sensory stimulation artefacts based on cultural elements for Portuguese people with dementia. Portugal is the 4th OECD country with the highest prevalence of dementia, accounting for approximately 200,000 cases, with this number expected to more than double by 2050 [

1]. Population ageing is one of the main causes of the increase in dementia [

2]. According to the Population Reference Bureau [

3], Portugal is the fourth oldest country in the world, with the percentage of the ageing population expected to rise from 20% to 32% in the coming decades [

4].

Alzheimer's disease accounts for 70% of dementia cases. For every 1,000 people aged between 65 and 74 there are 53 new cases, a figure that rises to 170 in the 75-84 age group and to 230 in the population aged over 85 [

5].

As stated by WHO [

6], “there is no cure for dementia”, with pharmacological treatments acting on symptoms [

7]. Although these treatments are widely used, their impact is still modest [

8]. Concurrently, research has shown the importance of non-pharmacological treatments to ameliorate the symptoms of dementia and promote well-being [

9,

10], emphasising the potential of those centred on the person, their biography and culture [

11]. Of particular importance are the theories of Kitwood [

9] who advocated person-centred care in which the person comes first (and not their state of dementia) with their personality, story of life, and social context being key factors.

Health professionals and researchers have followed these premises focusing on care models based on recognising and valuing the person, their personhood and social context [

12,

13]. Non-pharmacologic interventions such as reality orientation, reminiscence or cognitive and sensory stimulation have shown considerable evidence of their effectiveness, especially when focused on the person's life experiences and culture [

8,

14]. Reminiscence therapies and activities centred on the person's life story have integrated interventions for people with dementia at different stages, helping to reinforce identity, stimulating enjoyment and encouraging relationships [

15].

Design researchers have contributed to these therapies with cognitive and sensory stimulation artefacts based on the personhood and life stories of persons with dementia. Participatory methods have been widely used with positive results, offering insights into people’s interests, social and relational contexts, while providing qualitative contributions, relevance, and validation [

13,

16,

17,

18]. However, much of the research is focused on persons with mild to moderate dementia, with a few exceptions such as the work of Treadaway and colleagues [

19] with persons with advanced dementia.

This article addresses an exploratory study that delves into the potential of cultural elements in the cognitive and sensory stimulation of persons with moderate to advanced dementia through participatory design methods. It is hypothesised that including cultural elements transversal to the persons’ biographies may hold greater potential for stimulating their senses and evoking reminiscences. This hypothesis was explored through textile artefacts with women with Alzheimer’s Disease at the Day Centre “Memória de Mim”[“A Memory of Myself”], a service specialised in dementia run by Alzheimer’s Portugal association (partner of the project). The study was held within the framework of the research REMIND, which aims to identify design contributions based on cultural and biographical components for cognitive and sensory stimulation of persons with dementia in Portugal.

2. Research Methods

In a preliminary phase, visits were made to the Centre aiming to familiarise and establish a close and trusting relationship with the persons with dementia, to learn about their life stories, interests and preferences, to observe dynamics, daily activities and interactions experienced there, and to identify habits [

17,

20]. To avoid possible confusion and overstimulation with the presence of all team members at the Centre, the consistent point of contact method [

21] was adopted, i.e. only one member of the research team made systematic visits to the Centre who was integrated as a volunteer member.

The researcher took part in various activities and tasks such as meals, walks outside, leisure activities (watching TV programmes, listening to music, playing games), creative activities (crafts, painting), group therapies and cognitive and sensory stimulation activities. This provided greater proximity between the researcher and stakeholders [

20,

22].

Ethnographic methods were combined, including visual and sensory ethnography [

23,

24], participant observation [

25], walking interviews [

26], focus groups and informal interviewing with care workers [

22], collection and documentation of materials [

27,

28], including sensory and cognitive stimulation artefacts.

The information collected at the Centre was analysed and cross-referenced with data from scientific literature for a better contextualisation and understanding of the events observed [

29]. Biographical characteristics of the persons with dementia at the Centre, personal interests and relevant stories told by themselves, health professionals or relatives were documented. This data was gathered and mapped on a concept map, divided into 5 categories: “Dementia/Symptoms” based on scientific data; “Life experiences” with stories by those living with dementia, their relatives and health professionals; “Design contributions”, with possible design approaches for cognitive and sensory stimulation, and important features to include; “Portuguese Culture” with cultural elements relevant between the 1960s and 1980s, the most meaningful years for the target audience; “Biographical Aspects” covering content related to the target audience, activities and routines at the Centre.

Textile artefacts were found in several of the Centre's tasks and activities, such as creative activities which were regularly based on fabric collages, or therapeutic activities based on winding woollen or cotton threads onto cardboard rolls. It was also observed the frequent use of polyester fleece blankets to cover persons with dementia, especially those with advanced dementia who spent long periods of time sitting on articulated armchairs. These blankets warmed them and provided a sense of comfort. This led the team to focus on the design of a sensory blanket that could cover the person while providing cognitive and sensory stimulation.

The next phase was dedicated to selecting the fabrics to be used through participatory design methods. Participants included seven women attending the Centre — five with advanced Alzheimer’s Disease and two with moderate Alzheimer’s Disease.

All the participatory methods took place at the Centre and were first presented to health professionals to ensure their suitability to the target audience. These methods were inspired by work of Hendriks et al. [

20], Treadaway et al. [

19], van Rijn, van Hoof, and Stappers [

17], and Costa [

30], and adapted to the features, culture and abilities of the women involved.

It was intended to be a meaningful engagement of the women while fostering well-being in the moment [

31]. Hence, participatory methods prioritized sensations and emotions that could provide well-being, such as pleasure, involvement, connection, sense of belonging, self-identity, and a sense of purpose.

For participants with advanced dementia and severely compromised verbal-communication skills strategies included putting fabrics in their hands and observing their reactions, placing one to three fabrics on a table where the person was and monitoring their reactions: whether they were indifferent, grabbed or pushed one of the fabrics away, how long they handled a fabric, whether they touched it superficially or explored its textures. The analysis of the participatory process focused mainly on observing body reactions and facial expressions. However, words were occasionally spoken when viewing the fabrics, which were valued in this process.

For participants with moderate dementia, while showing different fabrics, strategies included storytelling built on the researcher's knowledge of the participant's interests, imagining possible uses, discussing features of the fabrics. During the process, the comments by participants were considered alongside their body reactions and facial expressions to each fabric presented.

For both groups of women, participatory design methods were applied and repeated at different times and days, envisaging more consistent results.

In the first stage, fabrics presented were chosen for their diversity (colour, texture, consistency, weight) with no apparent relationship with Portuguese culture.

In a second stage, samples produced with different crochet techniques and contrasting colours were presented, a technique commonly used in Portugal in past decades. The practice of crochet was essentially a response to everyday needs, with artefacts developed for utilitarian use [

32]. In the 1970s-80s it was common for women to produce quilts and blankets, cushions and garments using crochet granny square patterns [

33]. Hence, crochet was used as a cultural element to observe and compare the participants' reactions to the first fabrics and understand the potential of including cultural elements for cognitive and sensory stimulation. Crochet samples of various sizes and formats, and with contrasting colours were produced using different stitches (see

Figure 1).

Ethical Considerations

All participants were duly informed about the goals and procedures at each stage of the project and their anonymity was ensured. Before the participatory methods involving persons with dementia, they were contextualised on each activity and the purpose repeated several times throughout the process. The possibility of withdrawing from the project at any time without any prejudice to the individual was guaranteed. In the case of persons with dementia unable to give consent, this was ensured by carers. Furthermore, the contextualisation of the project, methodologies and procedures were submitted to the Ethics Committee of the University of Porto with approved protocols.

3. Results

3.1. Participatory Design Involving Women with Dementia

The reactions of women with advanced dementia to fabrics with no connection with Portuguese culture were diversified. For example, in one case, a soft fabric was placed in the participant's hands. As no reaction was observed, fabrics with fur were passed through her hands asking if it was good. The woman replied affirmatively, but this seemed to be an automatic reaction and there were no additional signs or expressions of pleasure.

A lace fabric was latter shown, which led her to verbalise “Cambric” (Fine linen or cotton fabric, often used for lace or embroidery work), followed by “It's from N. (Random letter used for her son's name.)”. As her verbal communication skills were very compromised, it was not possible to engage in a conversation that would allow us to ascertain the meaning of her reaction. However, it suggested that this fabric had a sentimental value, evoking memories. This perception was confirmed when a new fabric was given to her, and she said “Cambric! O. (Random letter used for her daughter's name.) made it!”. Considering her apparent interest in cambric, a pink sample of this fabric with white flowers embroidered was brought to the Centre and shown to her. She held the fabric, handled it for a while and left it with no further reactions or words.

One of the samples shown was from a blanket in shades of white and grey. This was placed on a table where two women were seated. One of them held it tightly and stayed with it until health professionals took her to another activity. After she left, the fabric was placed in front of the other woman and her attention drawn to it. She grabbed it and ran her hand over it several times, occasionally folding it, as if to sense the texture and materiality. Other fabrics were placed on the table and shown to her. One of these, a black lace, she threw away, while another, in soft fur, she groped for it. Later, she grabbed the black lace again and felt asleep with it in her hands.

These interactions with different fabrics were observed for several weeks at different times and it was possible to identify fabrics that seemed to elicit greater interest and reactions. Still, each woman's reactions varied at different times and were not always consistent (occasionally resembling spontaneous reactions). The women's fabric preferences also seemed to differ.

Regarding women with moderate dementia, it was possible to gain deeper insights into their experiences and perceptions throughout the participatory process since their verbal communication skills were less compromised. When the project was contextualised and their participation requested, they were always very keen to learn about the project and give their input.

Patterned fabrics elicited more interest from these women than plain ones. When it was suggested that fabrics could be combined, one of them rejected the idea, suggesting that we should always use the same one. The Cambric fabric was the most appreciated by one of the women. Another fabric with printed flowers also pleased her, while fabrics with geometric prints (squares or stripes) elicited less interest. It should be noted that this woman had been a seamstress. So, while she was appreciating the fabrics, she explained how they could be applied to the artefact and how they could be sewn and finished. In the case of fabrics with geometric prints, she was concerned about how the lines would come together in the seams, a factor that determined the exclusion of these fabrics in the selection process.

3.2. Introducing Cultural Elements

After experimenting with different fabrics with no connection to Portuguese culture, samples in crochet were brought to the Centre. In the case of women with advanced dementia, the participatory methods always took place at a table where various samples were arranged.

When shown the samples, one of the women grabbed a larger orange square, handled it a while and put it down again. Later, she picked another and wiped it across her cheek. She kept the sample until the care workers came to pick her up.

A second woman at the table stretched out her arms, reached for the crochet samples and spontaneously said “It's beautiful”. Due to her severe aphasia, this reaction was found surprising to the researcher and the healthcare professionals present during the activity. Then, she pointed to the orange square and said “Look, that one please”. The sample was passed to her, and she threw it back with a smile, as if playing along. She was then shown one of the smaller samples, to which she replied, “the lace”. Her limited verbal expressions, combined with her non-verbal reactions — such as handling the crochet samples, picking them up and throwing them with a smile — were interpreted as positive responses.

Another woman approached the table and sat down. She grabbed several crochet squares and started handling them. Some of them did not have the finishes done with threads hanging down. She pulled on the threads several times as if trying to understand where they came from. She folded the largest square, placed the smaller ones together, overlapped the various pieces, and repeated these actions as if looking for the best way to organise them. She remained focused on this activity for several minutes.

On another occasion, crochet samples were placed in front of a woman with no verbal communication skills. At first there was no reaction — she remained seated with her arms crossed in her usual position. Shortly afterwards, she picked up an orange square and handled it for a while. She pulled out the loose threads and tried to fit them into the holes in the crochet. With her fingertips, she groped the texture, passing them through the holes, as if trying to get through them. She folded and unfolded the square repeatedly. Occasionally, she would put it down for a while and pick it up again. For much of that afternoon, she kept various crochet squares with her, handling them, experimenting with them and pulling on their threads, a reaction that was considered positive by health professionals, as she often appeared apathetic towards her surroundings.

Regarding women with moderate dementia, reactions were very positive. When crochet samples were shown to one of the women, she recalled she had crocheted before and began to share memories of her sister who used to make bedspreads with crochet squares like the ones shown. Though she enjoyed all the samples, the square ones drew more attention, reminding her that in the past it was very common to make blankets and bedspreads with squares like those and that she herself had also crocheted.

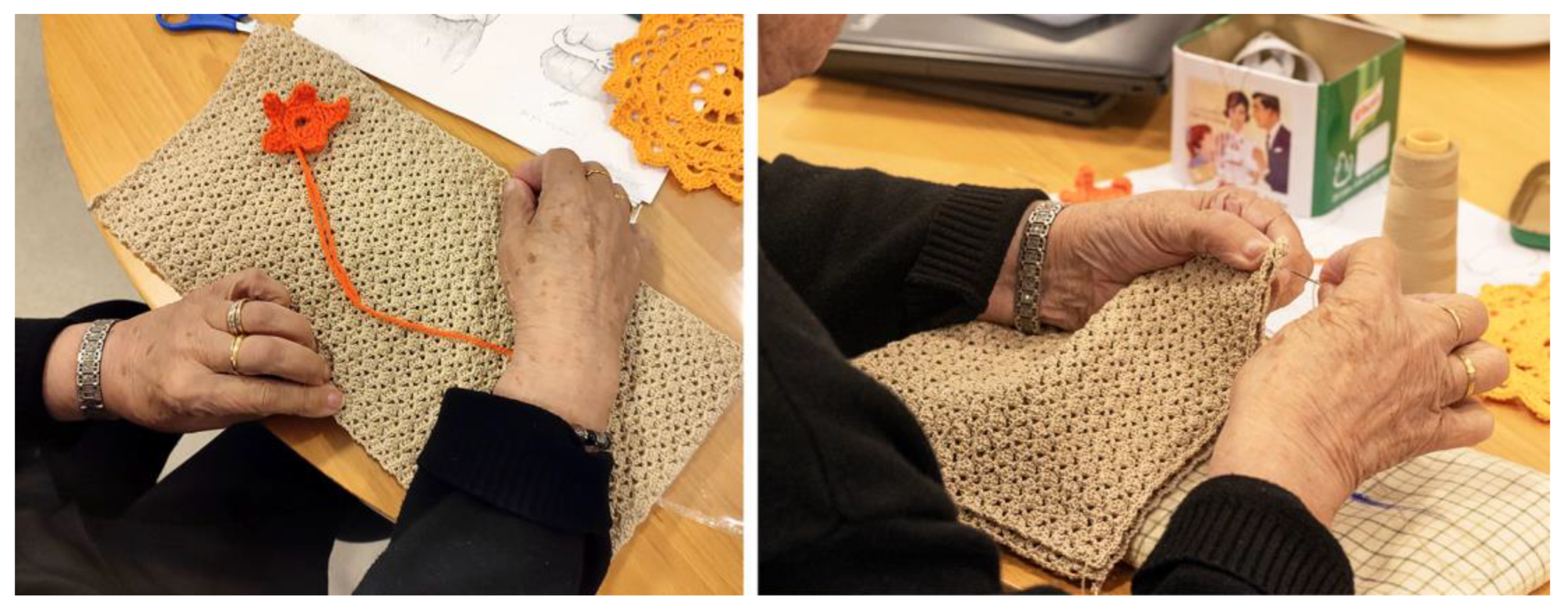

The second woman, the former seamstress, also enjoyed the pieces very much. She was shown crocheted flowers, squares and rectangles in various colours and sizes. When asked what we could do with these pieces, she looked at one of the comfort cushions at the Centre and, claiming it was ugly, suggested that we could make a pillowcase out of the brown rectangle and attach a flower with some thread and pompoms. She said she no longer could crochet, but she gave us various ideas on how to combine the samples we had. She folded a brown rectangle and explained how we could make the pillowcase. She realised that the sides were not quite right and asked us for a needle and thread to sew them together and sort it out. The necessary materials were provided, and she began to line up the sides (see

Figure 2).

As she lined up the crochet pieces, she mentioned that she had sewn a lot and taught and managed more than 100 women in a factory: ‘I'm a seamstress and I've taught many to sew’. Pointing to the thread she was sewing with, she said that ‘this thread was like mine from the factory’. This woman spent almost an hour engaged in sewing the pillowcase and even when her granddaughter came to pick her up from the Centre, she would not stop. When she finished, she was visibly happy, showing the pillowcase to everyone and saying she could do more if necessary.

4. Discussion

The participatory design with the women with advanced dementia proved particularly challenging due to their verbal communication skills severely compromised. The interaction relied heavily on the physical component, on exchanging and experimenting with textiles and evaluating/interpreting reactions. The use of sensory ethnography methods was key to this interaction. The technique of laying samples on a table in front of them was advantageous, since it enabled to assess their reactions to the sample.

Throughout the participatory design, the women's well-being was always prioritised, their enjoyment through engaging in experimenting with the fabrics and crochet samples. Given most of the women lived with advanced dementia, the contextualisation of the project and the purpose of their participation was information they were unlikely to retain or comprehend (although this was systematically provided), so the end result was not the goal of the project, but rather the participatory act and the pleasure they could get in the moment, that is, as Treadaway et al. [

19] point out, the well-being in the moment.

Hence, although the participatory design methods were previously structured, the way they proceeded was always the result of the participants' actions and choices, how they led and induced the process: the moment when a woman decides to make a pillowcase from a crocheted rectangle is a clear example. This is in line with Pink [

23] (p. 51) who points out that “it is impossible to ever be completely prepared for or know precisely how an ethnographic project will be conducted before starting”.

The first fabrics with no connection with Portuguese culture elicited diversified reactions from participants with advanced dementia which varied throughout the process. Inconsistency in reactions was noted, which may be due to the person's state of dementia. In one case, memories of the past were triggered when shown a fabric that reminded Cambric, suggesting the activation of personal life stories through sensory stimulation. This exemplifies the potential of sensory stimulation with persons with advanced dementia, which is in line with findings from Treadaway et al. [

19].

For women with moderate dementia, reactions throughout the process were more consistent and a strong sense of commitment to the participatory process was felt. Nonetheless, their involvement was limited to selecting fabrics and, in one case, explaining how they should be sewn, without prompting any further dialogue about the fabrics.

Concurrently, samples in crochet (with a strong connection with Portuguese culture and life stories of these women) elicited greater attention and reactions from all participants. Women with advanced dementia spent more time handling these samples, experimenting with its textures and holes, pulling loose threads and trying to fit them into the holes. Women with moderate dementia, not only verbalised their appreciation but also recalled positive memories. Reactions to the crochet samples are summarised in

Table 1.

It is thought that reminiscences may have happened as well with women with advanced dementia, i.e. the crochet may have triggered emotional memories. In advanced stages of dementia, although logical and autobiographical memory can be very compromised, implicit emotional memory can remain for much longer. As stated by Treadaway et al. [

19] (p. 13), “objects can retain important emotional significance for a person and stimulate moments of clarity when past memories are revived and re-experienced”.

It should be emphasised the greater involvement of one woman whose former occupation was seamstress, which reinforces the potential of drawing up participatory design on the person's personhood and life story [

21,

30]. On her own initiative, she engaged in producing an artefact with the crochet samples, confirming Costa's [

30] remarks that this approach contributes to increasing the level of participation and involvement of the participants. Her engagement provided her with moments of reconnection with her own history, evoking positive memories.

The technique — crochet — is recognised as a factor that led to greater interest and engagement, since it was widely used in the most meaningful decades for this generation. Part of these women used to crochet bedspreads, tablecloths and garments. Additionally, the use of bright, contrasting colours may have contributed to attract their attention, as well as the loose threads which elicit further interest of the women with advanced dementia.

The results support the hypothesis that the inclusion of cultural textiles linked to the biographical stories of persons with dementia has significant potential to stimulate their senses and evoke reminiscences. However, it is acknowledged that these findings are based on an exploratory study with a limited group of participants and focused solely on textiles, highlighting the need for further research in this area. This includes exploring other cultural elements through textile or other artefacts and involving a broader demographic, including men with dementia. While it may have been less common for men of this generation to crochet, crochet artefacts were often present in shared living spaces as household decorations or practical items. Therefore, it is anticipated that the presence of crochet in the Centre could contribute to creating a more welcoming and familiar environment, offering benefits beyond reminiscence and warranting further exploration.

Given the positive feedback shown by all participants, a first textile artefact was produced — a blanket combining crochet squares of different sizes and colours. A modular layout was designed to combine the sizes of squares. Different crochet techniques were chosen to diversify the sensory stimulus and prompt greater interest and willingness to explore the pattern for longer. Five bright colours were combined, exploring contrasts, chiaroscuro and chromatic complementarity to reinforce visual stimulation. A different crochet stitch was used around the blanket and a fringe was added with several loose threads in each corner for additional sensory stimulus, as the loose threads had sparked great interest in several women (see

Figure 3).

This blanket can be used over the legs when women are in the armchairs allowing for constant visual and sensory contact or to cover their back, wrapping them up as a shawl. The blanket has already been used at the Centre. The reactions are diverse and include running the hands over it, as if sensing its texture, groping the crochet work, handling the fringes. In certain cases, handling the blanket keeps the person entertained and focussed for long periods of time, as shown in

Figure 4. The blanket has been also used in sensory activities led by healthcare professionals: together with persons with advanced dementia they explore colour patterns and the effects by crochet stitches.

Following participatory design methods at the Centre, additional activities have been developed to involve women with moderate dementia in the production of textile artefacts, such as co-designing and sewing pouches, as shown in

Figure 5. Studies have shown that the active involvement of people living with dementia in activities that are meaningful to them and related to their life story helps to increase their self-esteem, strengthen their identity and dignity, and foster a sense of purpose [

34]. They stimulate positive emotions, a longer and significant involvement of the person and, subsequently, contribute to an increase in their well-being, to their flourishing [

35].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Cláudia Lima, Susana Barreto and Catarina Sousa.; methodology, Cláudia Lima and Catarina Sousa; formal analysis, Cláudia Lima; investigation, Cláudia Lima, Susana Barreto; resources, Cláudia Lima, Catarina Sousa; data curation, Cláudia Lima; writing—original draft preparation, Cláudia Lima and Susana Barreto.; writing—review and editing, Cláudia Lima, Susana Barreto and Catarina Sousa; visualization, Cláudia Lima and Susana Barreto; supervision, Cláudia Lima; project administration, Cláudia Lima. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, I.P. by project reference UIDB/04057.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study. All participants, health professionals and care workers were thoroughly informed on the project's goals and procedures at each stage, and their anonymity was ensured. That is, all ethical considerations were carefully addressed and upheld. The possibility of withdrawing from the project at any time without any prejudice to the individual was guaranteed. In the case of persons with dementia unable to give consent, this was ensured by carers. Participant consent information and informed consent to participate was verbal. For persons with dementia, this information was provided at the beginning of each activity and reinforced along the process. Additionally, the project's context, methodologies, and procedures were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Porto on February 13, 2024.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank to all persons with dementia and health professionals who participated in this study and bodies from Alzheimer's Portugal Association who have been contributing to the research REMIND.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- OECD. Health At A Glance 2021; 2021. [CrossRef]

- Santana, I.; Farinha, F.; Freitas, S.; Rodrigues, V.; Carvalho, Á. Epidemiologia da Demência e da Doença de Alzheimer em Portugal: Estimativas da Prevalência e dos Encargos Financeiros com a Medicação. Acta Médica Portuguesa 2015, 28, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Population Reference Bureau. Countries with the oldest populations in the world; 2019. https://www.prb.org/resources/countries-with-the-oldest-populations-in-the-world/. (accessed on 28 October 2024).

- Vilar, M.; Sousa, L. B.; Firmino, H.; Simões, M.R. Envelhecimento e qualidade de vida. In Saúde mental das pessoas mais velhas; Firmino, H., Simões, M. R., Cerejeira, J. Coord., Eds.; Lidel: Lisboa, Portugal, 2016; pp. 19–43. [Google Scholar]

- Albuquerque, E.; Esteves, P. S.; Cerejeira, J. Doença de Alzheimer. In Saúde mental das pessoas mais velhas; Firmino, H., Simões, M. R., Cerejeira, J. Coord., Eds.; Lidel: Lisboa, Portugal, 2016; pp. 309–320. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization: WHO. Dementia. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia (accessed on 21 July 2024).

- Esteves, P. S.; Albuquerque, E.; Cerejeira, J. Demência Frontotemporal. In Saúde mental das pessoas mais velhas; Firmino, H., Simões, M. R., Cerejeira, J. Coord., Eds.; Lidel: Lisboa, Portugal, 2016; pp. 321–330. [Google Scholar]

- Câmara, J.; Nunes, M. V. S. Impacto de um programa de estimulação cognitiva na comunicação e cognição: Um estudo com pessoas com demência institucionalizadas. In Centro de Desenvolvimento Académico, Universidade da Madeira eBooks; 2021; pp 273–285. [CrossRef]

- Brooker, D.; Kitwood, T. Dementia Reconsidered, Revisited; the person still comes first. Open University Press: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- McDermott, O.; Charlesworth, G.; Hogervorst, E.; Stoner, C.; Moniz-Cook, E.; Spector, A.; Csipke, E.; Orrell, M. Psychosocial Interventions for People With Dementia: A Synthesis of Systematic Reviews. Aging & Mental Health 2018, 23, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, G. A.; Sousa, I.; Nunes, M. V. S. Cultural Adaptation of Cognitive Stimulation Therapy (CST) for Portuguese People with Dementia. Clinical Gerontologist 2020, 45, 891–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, G. A.; Sousa, I. Viver com Demência. Ordem dos Psicólogos: Lisboa, Portugal, 2022.

- Tsekleves, E.; Keady, J. Design for People Living with Dementia: Interactions and Innovations. Routledge: London and New York, 2021.

- Aguirre, E.; Spector, A.; Orrell, M. Guidelines for adapting cognitive stimulation therapy to other cultures. Clinical Interventions in Aging 2014, 1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooker, D. Personhood maintained: Commentary by Dawn Brooker. In Dementia reconsidered, revisited; the person still comes, first, Brooker, D., Eds.; Kitwood, T. Open University Press: London, Portugal, 2019; pp. 78–82. [Google Scholar]

- Garde, J. A.; Van Der Voort, M. C.; Niedderer, K. Design Probes for People with Dementia. Proceedings of DRS 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rijn, H.; Van Hoof, J.; Stappers, P. J. Designing Leisure Products for People With Dementia: Developing ‘“the Chitchatters”’ Game. American Journal of Alzheimer S Disease & Other Dementias® 2009, 25, 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, J.; Wright, P. C.; McCarthy, J.; Green, D. P.; Thomas, J.; Olivier, P. A design-led inquiry into personhood in dementia. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems 2013, 2617–2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treadaway, C.; Fennell, J.; Prytherch, D.; Kenning, G.; Prior, A.; Walters, A.; Taylor, A. Compassionate Design: How to Design for Advanced Dementia – a toolkit for designers; Cardiff Met Press: Cardiff, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks, N.; Huybrechts, L.; Slegers, K.; Wilkinson, A. Valuing implicit decision-making in participatory design: A relational approach in design with people with dementia. Design Studies 2018, 59, 58–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, S.; Brittain, K.; Jackson, D.; Ladha, C.; Ladha, K.; Olivier, P. Empathy, participatory design and people with dementia. CHI 2012: 30th ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems 2012, 521–530. [CrossRef]

- Antelius, E.; Kiwi, M.; Strandroos, L. Ethnographic methods for understanding practices around dementia among culturally and linguistically diverse people salon. In Social Research Methods in Dementia Studies Inclusion and Innovation; Keady, J., Hydén, L., Johnson, A., Swarbrick, C. Eds, Eds.; Routledge: London & New York, 2019; pp. 121–139. [Google Scholar]

- Pink, S. Doing sensory ethnography. Sage Publications, 2015.

- Pink, S. Doing visual ethnography. Sage Publications, 2021.

- Ciesielska, M.; Boström, K. W.; Öhlander, M. Observation methods. In Springer eBooks; 2017; pp 33–52. [CrossRef]

- Kullberg, A.; Odzakovic, E. Walking interviews as a research method with people living with dementia in their local community. In Social Research Methods in Dementia Studies Inclusion and Innovation; Keady, J., Hydén, L., Johnson, A., Swarbrick, C., Eds.; Routledge: London & New York, 2019; pp. 23–37. [Google Scholar]

- Banks, M.; Zeitlyn, D. Visual methods in social research. Sage Publications, 2015.

- Tinkler, P. Using photographs in social and historical research. Sage Publications, 2013.

- Norman, D. Design for a Better World: Meaningful, Sustainable, Humanity Centered. The MIT Press: Cambridge, Massachussets, 2023.

- Costa, A. Demência — Desdramatizada e colorida. Prime Books: Portugal, 2019.

- Treadaway, C.; Prytherch, D.; Kenning, G.; Fennell, J. In the moment: designing for late stage dementia. Proceedings of DRS 2016, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruchinho, A.; Duarte, D.; Marcelo, A.S.; Péres, P. Renda das Lérias – Tradição e Inovação na Moda. In Património, Educação e Cultura: Convergências e novas Perspetivas; Jorge, F. R., Belo, J., Ribeiro, M. Coord., Eds.; Instituto Politécnico de Castelo Branco: Castelo Branco, Portugal, 2023; pp. 231–245. [Google Scholar]

- Borden, M. Why is the Granny Square called a Granny Square?. PieceWork. https://pieceworkmagazine.com/why-is-the-granny-square-called-a-granny-square. (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- Rodgers, P. A. Co-designing with people living with dementia. CoDesign 2017, 14, 188–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M. E. P. A vida que floresce. Estrela Polar: Algfragide, Portugal, 2012.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).