Development

In the article entitled A Brief History of Western Cult Furniture Design. The Chair (Part 3). Building a Theoretical Framework of the Chair as a Machine-Tool for Sitting Through Premodernity, Modernity and Postmodernity, written by Anderson and Girod in ArtyHum magazine No. 90. We argued that Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc (1814-1879) analyzes Gothic architecture not only in formal and structural terms, but also in relation to the social, economic and political conditions of the time, arguing that this architecture reflects a specific social order that manifests medieval values and social organization. Although the author does not explicitly use the term, his analysis implies that architecture is a cultural manifestation linked to a given social context, which has influenced later studies on the relationship between architecture and society. Anderson's PhD thesis (2014) connects this concept with the zeitgeist of Siegfried Giedion (1888-1968) who defines the zeitgeist as the cultural and social influence on artistic expressions; suggesting that both Viollet-le-Duc and Giedion consider architecture a reflection of society, where the social order and the spirit of the times are essential to its understanding. This theoretical work aims to interpret the stylistic complexity of non-industrial furniture design through analytical categories of social order that influence various aesthetics applied to vernacular and Creole artisanal design.

In that article in ArtyHum magazine nº 90 we defined the following for Europe: the feudal social order from which a feudal-monastic aesthetic is derived, the absolutist-monarchic social order from which a courtly-monarchic aesthetic is derived (1643-1789) typical of the Ancien Régime, and the liberal social order from which a triple aesthetic is derived: (a) non-modern (1789-1928) typical of 17th and 19th century artisanal furniture, (b) modern (1928-1959) typical of 20th century furniture and (c) postmodern (1960-2024) typical of contemporary furniture design. But how can we transpose these theoretical-analytical categories from Europe to America?

“The pre-Columbian social order is characterized by a mythical-cosmogonic aesthetic (…). This long period marks the arrival of the first humans to the continent and culminates with European contact.”

5

The pre-Columbian peoples of America cover a broad period and “The arrival of the first humans in America is estimated to be around 15,000 BC, although some theories suggest even earlier dates.”

6There is a wide range of literature suggesting that the arrival of Christopher Columbus in 1492 marked the beginning of significant contact between Europe and American civilizations. “We are talking about a broad period that covers: (circa 15,000 BC - 1492 AD)”

7 During this long period, numerous cultures and civilizations developed in various regions, including the Mayans, Aztecs, Incas and many other indigenous peoples.

Pre-Columbian cultures in the Americas are notable not only for their impressive architectural and artistic legacy, but also for their technological advances and ability to adapt to diverse environments. These societies developed sophisticated tools and techniques for construction, agriculture, and natural resource management. Innovation in irrigation systems, such as Andean terraces and chinampas, not only guaranteed food security but also demonstrated a deep ecological understanding.

Furthermore, the pre-Columbian worldview permeated all aspects of daily life. It not only defined religious practices, but also influenced urban planning, architectural design, and political structures. Cities were conceived as terrestrial representations of a cosmic order, with each construction reflecting the sacred relationship between man and the universe.

The impact of these cultures is not limited to the past; many of their traditions, symbols and practices are still present in contemporary indigenous communities. This cultural continuity reinforces the importance of understanding them not as extinct civilizations, but as living roots that contribute to the identity and cultural diversity of America.

Finally, from a comparative perspective, pre-Columbian cultures stand out for their uniqueness compared to other civilizations of their time. While in Europe and Asia the great architectural works were mainly driven by centralized state or religious structures, in America we observe a unique combination of technological innovation, spirituality and connection with nature that defined its development.

Thus, “In pre-Columbian cultures, rituals and myths not only structured daily life, but served as a bridge between the human world and the cosmos, reflecting a worldview deeply integrated with nature.”

8

Therefore, “Pre-Columbian architecture not only fulfilled practical functions, but also reflected complex social and religious structures.”

9It should also be understood that something similar happens in the rest of the arts; thus, “Pre-Columbian art was not only a form of aesthetic expression, but also a means of communicating religious and cosmological values. Geometric designs and anthropomorphic representations were loaded with symbolic meanings that reflected their spiritual and social beliefs.”

10

Ceteris paribus, “Pre-Columbian artifacts, from tools to ceremonial vessels, combined functionality and symbolism. These objects were not only useful in everyday life, but were also considered to carry sacred messages, fusing the beautiful and the practical.”

11 Thus, “Pre-Columbian ceremonial objects were much more than tools; they encapsulated concepts of cosmic order and served as instruments of connection with the sacred.”

12 It must be understood that almost any artifact becomes a ceremonial object. Eliade maintains that, “In each of their artistic expressions, pre-Columbian peoples managed to fuse the functional with the spiritual, achieving creations that still amaze us today for their symbolism and technical sophistication.”

13

Likewise, “The aesthetics of pre-Columbian peoples were deeply integrated with their religious practices. Ceramics, textiles and sculptures served as offerings to the gods and as tangible representations of myths and legends, reinforcing the connection between the human and the divine.”

14

Similarly, “Pre-Columbian artists carefully selected materials such as precious stones, metals, and natural pigments not only for their durability, but also for their symbolic properties. Bright colors and specific textures had meanings associated with fertility, power, and spiritual connection to nature.”

15

The objective is not to detail each of the pre-Columbian civilizations, but broadly speaking we can say that:

-The Mayan civilization: “They existed from 2000 BC until the 16th century, with their peak between 250 and 900 AD, covering southeastern Mexico, Guatemala, Belize and parts of Honduras and El Salvador.”

16They had a hieroglyphic writing system, an advanced calendar, and were experts in astronomy. “They built city-states like Tikal and Chichen Itza, with step pyramids and temples; they were polytheistic, worshipping several gods related to agriculture, the sun, and war.”

17

-The Aztec civilization: “They settled in the 14th century, reaching their splendor between 1428 and 1521 in central Mexico, especially in present-day Mexico City.”

18They had a strong focus on agriculture, growing mainly corn, and developed a writing system alongside a rich tradition of poetry and music. “The capital Tenochtitlan, built on a lake, had temples, palaces and canals, most notably the Templo Mayor pyramid; they practiced human sacrifice as part of their religious rituals to appease the gods.”

19

-The Inca civilization: “Formed around 1438, they fell in 1533 after the Spanish conquest.”

20 Their empire extended across Peru, Ecuador, Bolivia, Chile and Argentina. “They had an impressive road system (Qhapaq Ñan) that facilitated trade and communication, and although they did not have a writing system, they used quipus to keep records.”

21They built cities in the mountains, such as Cusco and Machu Picchu, using advanced stone construction techniques. “They were polytheistic, worshipping several gods, the most important being Inti, the sun god.”

22

The aesthetics of pre-Columbian peoples, spanning from approximately 15,000 BC to 1492 AD, can be described as deeply connected to their worldview and mythology. “The idea of a mythical-cosmogonic aesthetic is apt, as many pre-Columbian civilizations had a strong bond with nature, gods, and cosmic cycles.”

23

Pre-Columbian cultures in the Americas, represented by diverse civilizations, are characterized by their ability to adapt to varied environments, complex social organization, and a deeply spiritual worldview. These societies developed advanced agricultural systems that allowed them to thrive in challenging geographical conditions, such as tropical rainforests, high plateaus, and coastal valleys.

Their connection with nature and religion was fundamental, manifesting itself in the construction of monuments that integrated functional and symbolic aspects. Pyramids, temples and ceremonial centers were not only architectural structures, but also expressions of their beliefs in cosmic order and its relationship with natural cycles. These works, often aligned with astronomical events, reflect an advanced knowledge of the cosmos.

The social organization of these cultures was based on a hierarchy that combined political and religious power. Leaders, considered intermediaries between gods and men, played a crucial role in the cohesion of their communities. This structure also facilitated the development of trade networks and cultural exchange, promoting a rich diversity of artistic and technological expressions.

Agriculture was an essential pillar for these civilizations, highlighted by innovations such as Andean terraces, irrigation systems and chinampas. These techniques not only guaranteed food security, but also strengthened the economic and social foundations of their empires.

In conclusion, pre-Columbian cultures left an indelible legacy that is reflected in their architecture, art and philosophy of life. Their ability to harmonize with the environment and their deep understanding of natural cycles continue to inspire contemporary studies on sustainability and social organization.

On the other hand, “Pre-Columbian art is characterized by its symbolism and its connection with natural cycles, elements that reinforced both its cultural identity and its understanding of the universe.”

24

Mythic-cosmogonic aesthetics had a lot of symbolism in its art and architecture elements reflecting religious and mythological beliefs. For example, pyramids and temples, such as those at Teotihuacan or Tikal, were aligned with astronomical events.

The materials used were natural and local, such as stone, wood and ceramics, often decorated with symbols that represented their beliefs and connection to the earth. They used vibrant colours and shapes that evoked elements of nature, such as animals and plants, reflecting their environment and spirituality.

It is important to consider that there was great diversity in pre-Columbian aesthetics depending on the region (Andes, Mesoamerica, North America, etc.). Each culture had its own traditions and styles. Many works of art told stories or represented myths, which adds a narrative layer to the aesthetic. Incorporating this aspect can enrich the interpretation.

Consideration should be given to how changes in the environment (such as agriculture and urbanisation) impacted aesthetics and architecture. This could add depth to understanding their evolution. How interactions between different groups (trade, migration, etc.) influenced artistic styles and techniques should also be explored.

In summary, mythical-cosmogonic aesthetics are a good basis for understanding the art and design of pre-Columbian peoples within the pre-Columbian social order; they reflect several fundamental aspects of the worldview and daily life of these cultures.

Aesthetics incorporate elements that reflect religious and spiritual beliefs. Temples, pyramids and other buildings were not only functional structures, but also sacred, meant to pay homage to deities and nature. Works of art and design reflect a deep connection with the natural environment. Many designs incorporate elements of local flora and fauna, symbolizing respect and veneration for the earth. The depiction of astronomical and temporal cycles, such as the solstices and equinoxes, shows how these cultures understood their place in the cosmos. This is manifested in the alignment of buildings and in iconography that reflects the relationship with agricultural cycles.

Aesthetics are also a reflection of cultural and social identity. Each pre-Columbian civilization had its own visual language, which served to communicate its history, myths, and values through art, pottery, and architecture. The works often tell stories and depict myths, reinforcing social and cultural cohesion. These visual narratives helped to transmit knowledge, traditions, and values to future generations.

Example: “The Throne of Piedras Negras (…), refers to an archaeological object found at the site of Piedras Negras, an ancient Mayan city in Guatemala.”

25Whose original name was Yokib (meaning great entrance), although there is no definitive consensus on that name, it is a pre-Hispanic archaeological site of the Mayan civilization "(...), located in the Usumacinta basin, was one of the most important centers of the Mayan civilization during the Classic period."

26Within the Sierra del Lacandón National Park, which contains important remains of one of the most important cities of the Classic Maya; although: “The pottery found here shows that it was occupied from 700 BC to 820 AD, it was between the years 450 AD and 810 AD that the city reached its current size.”

27This period was the most prosperous. “The city reached its peak during the 6th and 7th centuries AD, with a remarkable production of art and architecture.”

28

It is a stone throne or ceremonial throne found archaeologically, a type of object or structure that was used primarily in pre-Hispanic cultures of Mesoamerica, including the Mayans. These thrones not only served as a seat, but also had deep political and religious symbolism, representing the ruler's authority, power, and connection to the divine.

“The throne not only serves as a place to sit, but is a symbol of power and legitimacy.”29 Indeed, “This throne is known for its rich iconography and its importance in the representation of Mayan power and elite.”

30 This throne: “It was used in ceremonies and political acts, symbolizing the authority of the ruler and his connection with the gods.”

31Since: “The use of the throne in ceremonies and political acts gives it a deep meaning; in these contexts, it becomes an object loaded with ritual meanings.”

32“The throne not only served a practical function in ceremonies, but also symbolized the ruler's authority and connection to the divine.”33

The Piedras Negras Throne was deeply linked to Mayan religious beliefs, especially with the gods of fertility, rain and creation, such as K'awiil, Itzamná and Chaac. Through its symbolism, the throne represented the divine legitimation of the ruler and his ability to maintain cosmic and political order, being associated with both the divine and the natural forces essential to the well-being of the people.

Known for its great sculptural production compared to other ancient Mayan sites, the wealth of sculpture, together with the precise chronological information associated with the lives of Piedras Negras' elites, has allowed archaeologists to reconstruct the history of the political system and its geopolitical footprint.

“The ornamentation of the throne represented authority, status and connection to the gods, loading beauty with deep symbolism and purpose.”34

The Piedras Negras Throne (

Figure 2), refers to an archaeological object found at the site of Piedras Negras, an ancient Mayan city in Guatemala; this throne is known for its rich iconography and its importance in representing Mayan power and elite. Piedras Negras is located in the present-day department of Guatemala, near the Usumacinta River, which was an important political and cultural center during the Classic Mayan period.

It was the largest pre-Hispanic city in the Usumacinta basin, and is considered one of the most important cultural monuments in Guatemala, despite its isolation. Piedras Negras is located in the department of Petén, Guatemala, within the Sierra del Lacandón National Park, on the eastern side of the Usumacinta basin. It is located on top of an escarpment, occupying a series of valleys located at a considerable height on the riverbank.

It was used in ceremonies and political events, symbolizing the ruler's authority and connection to the gods. It features characteristics of Classic Mayan art, including intricate reliefs and an aesthetic that combines mythological elements with everyday life. This type of artifact is essential to understanding the social structure, religion, and political practices of the Maya, as well as their cultural legacy.

The premodern hypothesis on object design suggests a unification of the beautiful, the useful and the good, where aesthetics and functionality are intertwined with an ethical purpose. This idea is closely related to the Greek concept of kalokagathia, which represents the harmony between beauty and virtue, emphasizing that the beautiful must also be good and useful. On the Black Stone Throne, the useful, the beautiful and the good are clearly manifested in the following ways:

-The-useful-ceremonial:The primary function of the throne is to provide a ceremonial seat for the ruler. This practical use is essential in rituals and political events, where the throne symbolizes the ruler's authority and role in society. Furthermore, the throne is designed to be functional in its context, allowing the leader to actively participate in important ceremonies.

When we talk about ceremonial utility in the context of the Piedras Negras throne, we are not referring solely to the practical utility of sitting; although the throne does indeed provide a seat for the ruler, its functionality goes far beyond this physical aspect. The throne not only serves as a place to sit, but is a symbol of power and legitimacy; by being on the throne, the ruler is placed in a position of visible authority, which reinforces his role in society. The use of the throne in ceremonies and political acts gives it a deep meaning; in these contexts, it becomes an object or artifact loaded with ritual meanings, where the action of sitting implies a series of social and religious interactions that validate the power of the ruler. The function of the throne also implies its use in rituals that connect the ruler with the gods, which transcends the simple act of sitting and becomes a means of establishing spiritual and community relationships. By participating in ceremonies from the throne, the ruler reinforces the social and cultural structure of his community.

The ruler who sits on the Piedras Negras Throne is connected to several important gods in Mayan mythology, including Itzamná, the creator and wisdom god, often associated with heaven and earth, central to Mayan cosmology and symbolizing authority and knowledge; Kukulkán (also known as Quetzalcóatl in other Mesoamerican cultures), the feathered serpent god, associated with wind, rain, and fertility, representing balance and power; Yaxhá, a deity related to rain and agriculture, important for the prosperity of the community; K'awiil, the god of divine authority, frequently depicted with a scepter and a snake-like leg, symbolizing the ruler's power and legitimacy; and the gods of fertility and corn, such as Hun Hunahpú, Chac, and Ixchel, whose influences on agriculture and abundance were crucial to the survival of Mayan society.

-The-beauty-of-divinity:The throne’s aesthetics are notable for their complexity and formal expression, with intricate reliefs and carved details depicting Mayan figures and symbols. This beauty is not only meant to impress, but also reflects the beliefs and culture of the Mayan elite. The ornamentation and artistic design elevate the object beyond its practical function, creating a visual impact that highlights the ruler’s importance.

The throne is made of stone, with carved details that represent Mayan figures and symbols, reflecting religious beliefs and social hierarchy. With a laminar morphology, the throne has a seat and a backrest resolved in rectangular planes with visual continuity. It is supported on two legs located towards the interior of the vertices of the seat, shaped like a stipe that taper downwards. It is interpreted that the wall acts as a support for the backrest due to the absence of rear legs. On the backrest, two subtractions can be observed in the central part, corresponding to the low-relief carving of two faces. It is carved on its entire surface except for the area where the seat rests.

The perception of beauty on the Piedras Negras throne and in Mayan culture in general cannot be reduced to a modern or Western vision, as proposed by Western (post-Kantian) aesthetics; its understanding was deeply rooted in the Mayan worldview and its cultural context. For the Mayans, beauty was not only related to order and harmony, but also to the connection with the divine. The intricate reliefs and details carved on objects such as the throne were not merely decorative, but told stories, reflected myths and beliefs, and expressed cultural values. The ornamentation of the throne, in particular, transcended mere aesthetics, as it represented authority, status, and connection to the gods, imbuing beauty with deep symbolism and purpose. This relationship between beauty and functionality extended to social perception: a beautifully designed object could reinforce the ruler’s power and legitimacy in the eyes of the community, thus contributing to social cohesion and cultural identity. Mayan beauty was not conceived as an end in itself, but as part of a comprehensive approach that included the useful-ceremonial, from a ritualistic perspective, and the good of the beautiful-in-divinity, understood as the response of the gods to the requests of the rulers, creating a balance between the aesthetic, the functional and the ethical (the ethical can be considered as what is correct for the gods within the worldview of said society).

Mayan beauty was not perceived as an end in itself, but as part of a comprehensive approach that included the useful (according to what they considered useful from a ritualistic point of view) and the good (that the gods respond to the requests made by the rulers).

The Piedras Negras Throne, a significant artifact in Mayan culture, exemplifies this relationship. Crafted from stone with intricate reliefs, it not only serves a practical function in ceremonies and political acts, but also symbolizes the ruler's authority and connection to the divine. Its in-divinity aesthetic is intimately linked to its functional-ceremonial (or ritualistic) use and symbolic meaning, reflecting religious beliefs and the social hierarchy of the time.

-The-good:The throne also embodies values that we define today as ethical. As an object used in religious and political ceremonies, it represents the connection between the ruler and the gods, underlining his role as intermediary between the divine and the human. This ethical aspect implies that the ruler must act with justice and responsibility, maintaining social order and the prosperity of his community.

Thus, the term “good” in the context of the Piedras Negras Throne refers to the ethical and spiritual dimension that its use implies. Beyond being a ceremonial seat, the throne symbolizes the ruler’s responsibility as a mediator between the gods and the community. By sitting on the throne, the leader not only assumes a political role, but also an ethical commitment to act with justice, guarantee prosperity, and maintain the cosmic balance, which was essential for the survival and cohesion of Mayan society. This concept of goodness is intrinsically linked to the Mayan worldview, where the divine, the human, and the social are intertwined in a common purpose.

As in the Greek tradition of kalokagathia, where a beautiful object was meant to be morally correct and useful, the Mayan throne embodies these values. The iconographic richness of the throne reinforces its value in the community, showing that a beautiful object is not only ornamental, but also communicates a cultural and ethical legacy.

Thus, both the premodern hypothesis and the concept of kalokagathia (Greek) allow us to understand the Piedras Negras Throne as a symbol that transcends its practical function, representing the interconnection between beauty, utility and ethical meaning in Mayan culture. This underlines the importance of objects in the social context, where each element contributes to a deeper understanding of the identity and values of the society that created them.

Continuing with this pre-modern hypothesis #1: Before the Catholic Monarchs, the Kingdoms of Castile and Aragon each had their own monarchs who exercised forms of absolute power, although not to the same extent as the Catholic Monarchs. “The absolutist monarchy in Spain was consolidated mainly during the reigns of the Catholic Monarchs, Isabel I of Castile (1451-1516) and Ferdinand II of Aragon (1452-1516), who unified the kingdoms of Castile and Aragon at the end of the 15th century, laying the foundations of centralized power in the figure of the monarch

.”35“Isabel and Fernando initiated a process of centralization of power that would be the seed of the absolute monarchy in Spain. Through the creation of common institutions and the control of local churches, the foundations of a monarchy that did not tolerate the fragmentation of power were laid.”36

Later, “The 17th century in Spain witnessed the transition from a monarchy of divine right to a more authoritarian regime that closed the circle of absolutism.”37

Isabella I of Castile reigned from 1474 until her death, and Ferdinand II of Aragon reigned alongside Isabella from 1479 until his death. Their marriage in 1469 unified the kingdoms of Castile and Aragon, laying the groundwork for modern Spain. In 1492, they completed the Reconquista with the conquest of the Kingdom of Granada, the last Muslim stronghold on the Iberian Peninsula. Also in 1492, they issued the Edict of Granada, which expelled Jews who did not convert to Christianity.

They sponsored Christopher Columbus's voyage in 1492, which led to the discovery of the American continent and the beginning of Spanish colonial expansion.

They worked to centralize power in the figure of the monarch, weakening the influence of the nobility and strengthening royal administration.

The union of Castile and Aragon and the policies of the Catholic Monarchs marked the beginning of the absolute monarchy in Spain, which would be further consolidated in the following centuries with the Habsburgs and Bourbons. “The marriage between Isabella of Castile and Ferdinand of Aragon not only unified the kingdoms, but also strengthened royal power, paving the way for the establishment of a monarchy that, although not absolutely centralized in its early years, already gave signs of a change towards the concentration of power in the figure of the king.”

38

“Isabel and Fernando, through their marital and territorial policies, forged a real power that would be consolidated in the figure of the absolutist monarchs in the following decades.”39

After the Catholic Monarchs: House of Habsburg: From the reign of Charles I (1516-1556) to that of Philip II (1556-1598). House of Bourbon: From the reign of Philip V (1700-1746) to the 19th century, although there were interruptions at different times, such as the War of Independence (1808-1814).

The absolute monarchy in Spain can be considered from the reign of the Catholic Monarchs (1474) until the fall of the absolute monarchy in the 19th century, although the context and characteristics of absolutism varied: from 1474 (reigns of the Catholic Monarchs), until 1812 (Constitution of Cadiz, which limited the power of the monarch). "The figure of the absolutist king was consolidated over the centuries, especially during the government of the Catholic Monarchs, when the idea of the centralized monarchy in Spain was constructed."

40

“The Catholic Monarchs not only unified the kingdoms, but also laid the foundations for future absolutism in the Spanish monarchy by strengthening royal authority and central administration.”41

This covers a long period of consolidation and evolution of the monarchy in Spain.

“The Catholic Monarchs understood the importance of political centralization as a means to strengthen the State and maximize its power. This, together with their drive for religious unification, allowed them to move towards an absolutist model that would be more evident in later centuries.”42“The Catholic Monarchs were the initial architects of a monarchical system that, although not fully absolutist in its early days, laid the foundations for the concentration of power in the figure of the king, as evidenced by their political and religious reforms.”43

The Alcázar of Segovia is one of the most emblematic fortresses in Spain, known for its majestic architecture and its history linked to the Spanish monarchy. Located on a rocky hill, between the Eresma and Clamores rivers, the Alcázar has had various uses over the centuries: it was a royal palace, a prison and an artillery academy, among others. The Throne Room is one of the most significant rooms in the palace, used by the monarchs, especially during the reign of the Catholic Monarchs (Isabel I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon), to hold audiences and official royal court events. In this room, the monarchs received ambassadors, nobles and courtiers, and made crucial decisions for the kingdom. The decoration of the Throne Room is majestic and rich, reflecting the grandeur of the reign of the Catholic Monarchs. The throne, which occupies the central place, is flanked by artistic details that underline the authority and power of the monarchs.

One of the most representative elements of the Throne Room is the motto “Tanto monta, monta tanto” (It makes no difference whether it is one or the other), inscribed on the front of the canopy that covers the throne. This motto is one of the best-known insignia of the Catholic Monarchs and symbolises the equality and parity between Isabel and Fernando, despite the fact that they ruled in separate kingdoms. Adopted as part of the process of unification of Castile and Aragon after their marriage in 1469, the phrase expresses that, although Isabel was Queen of Castile and Fernando King of Aragon, their powers were equally important and complementary. In simple terms, the motto means “it makes no difference whether it is one or the other”, reinforcing the idea that there was no hierarchy between them, but rather an alliance of equals. This phrase symbolises the equal union between the two kingdoms and how, together, they ruled jointly.

The motto “Tanto monta, monta tanto” appears in various places in the Alcázar of Segovia, especially on the canopy of the throne, reinforcing the idea of duality and symmetry between the Catholic Monarchs. In the Throne Room, this motto has a symbolic value and underlines the majesty of the place, as well as the central figure of the monarch in his role of justice and governance. Throughout history, this motto has become one of the most representative emblems of the reign of the Catholic Monarchs and the consolidation of Spain as a unified power.

The Alcázar of Segovia was originally a military fortress built on the site of an ancient Roman fort, but over the centuries, the building has undergone various transformations. During the reign of the Catholic Monarchs and subsequent monarchs, the Alcázar was converted into a royal palace. The Throne Room is just one of the many historic rooms that can be visited within the Alcázar, which also includes the Tower of Juan II, the Queen's Chamber and the palace gardens. Today, the Alcázar of Segovia is one of the most visited tourist destinations in Spain, both for its architectural beauty and its historical significance. The Throne Room, with its decorated throne and the motto of the Catholic Monarchs, remains one of the most emblematic places in the fortress.

The thrones of the Alcázar of Segovia (

Figure 3) are related to the Throne of the Catholic Monarchs in terms of style and function. In the Alcázar, the thrones and chairs used by royalty were often made of carved wood, with ornamentation and details that symbolized the power and authority of the monarchs. High backrests and the inclusion of heraldic elements were common in these seats, highlighting the importance of the nobility and their status. Also the canopy that frames and zones the position of the thrones as well as the three steps that place them above ground level. Decoration with tapestry and other materials was also common practice, similar to what is seen in the throne of the Catholic Monarchs, which sought to create a visual impact and emphasize the greatness of the reign.

The throne of the Catholic Monarchs was in the flamboyant Gothic style, made of carved wood, often decorated with tapestry, reflecting the aesthetics and values of the monarchy at that time. Designed to highlight royal authority, it featured ornamental details that reflected the power and grandeur of the monarchy, with high backrests and heraldic symbols on the tapestry. In addition, there were other kings' chairs that reflected the monarch's status. The throne of Charles I, in the Plateresque style, was made of wood with silver details, emphasizing imperial power with intricate reliefs and a monumental design. The councillors' chairs, in the Baroque style, were made of carved wood, often with ivory or mother-of-pearl inlays; they were designed for nobility and councillors, focusing on comfort and ostentation, reflecting their importance in the administration of the kingdom.

Philip II's throne, in the Spanish Renaissance style, was made of walnut and had rich upholstery. Its design was more austere than those of its predecessors, reflecting a shift towards a more sober style, but it was still a symbol of authority. The court chairs, in the Rococo style (18th century), were painted or gilded and upholstered in silk; they were lighter and more ornate, reflecting a decorative style popular at court during the 18th century. Each of these seats not only served a practical function (not only did they have an intrinsic or per se utilitarian value; beyond the fact that kings could sit on them), but they had value as a symbol of power (symbolic value) because they were thrones rather than simple chairs and reflected the authority of the monarch, as well as the culture and art of the time (aesthetic value); their design and materials reflect the values and aesthetics of the Spanish monarchy at different times in its history.

This throne not only served a practical function, but also a symbolic one. In symbolic terms, the throne represented the divine and absolute power of the monarchs, but also the policy of centralization that the Catholic Monarchs implemented. The idea of a centralized monarchy, which would be the seed of the absolute monarchy in Spain; these pieces of furniture were not just objects of use, they were visual emblems of the monarch's supremacy, designed to project the grandeur and power of the crown.

Throughout history, the thrones of the Spanish monarchs evolved in style and materials, but always maintained their function as symbols of royal power. The relationship between the Catholic Monarchs and the throne of the Alcázar of Segovia is a clear reflection of the process of consolidation of the absolute monarchy in Spain. The throne, more than a simple seat, was a powerful symbol of royal authority, of the union of kingdoms and of the centralization of power, fundamental principles in the construction of Spain.

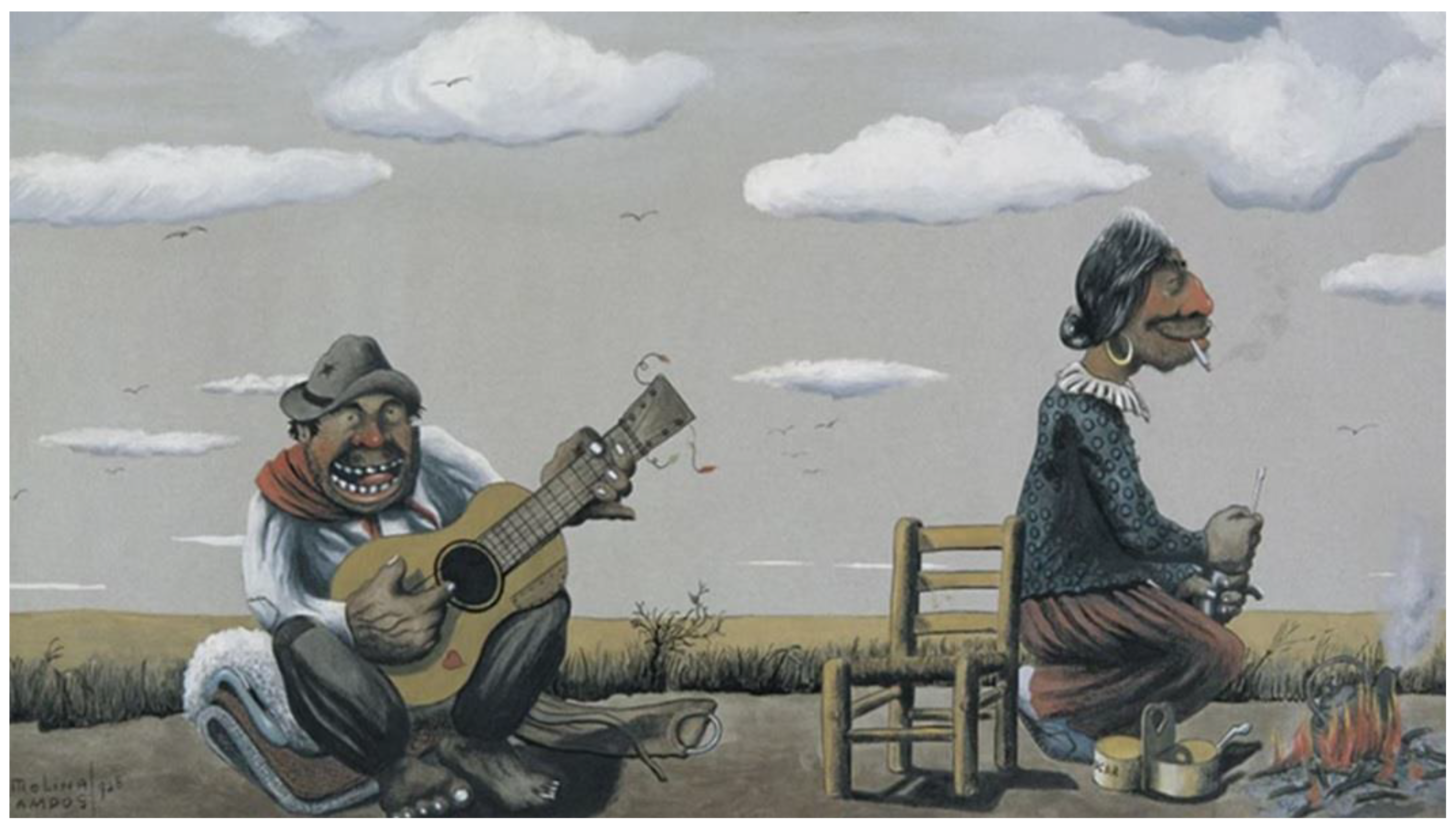

On the other hand, the article by Anderson and Girod, published in ArtyHum magazine no. 85, entitled “The Argentine Country Style Chair (Part 2). When Art Theory Becomes a Theoretical Paradigm to Explain the Typology of the Proto-Rationalist Country Style (or Gaucho Style) Chair in the Argentine Republic”, continues its analysis of the Argentine Creole chair from an artistic, cultural and historical perspective. This work follows the theoretical lines of that publication in the magazine, where the bases were established to understand the influence of the Iberian colonies and their relationship with local design.

The article explores rural design typologies in Argentina, focusing on the influence of artists such as Florencio Molina Campos (1891-1959), who reflected gaucho life and traditions in his caricatures and artwork. The study analyzes how rustic furniture, particularly the matera chair and other types of handcrafted furniture, reflect a minimalist and functional aesthetic that precedes the Modern Movement in Europe, including the Bauhaus. In addition, the article highlights the analogy between Argentine vernacular design and other rural cultures such as the Shaker community in the United States.

This theoretical analysis suggests that the geometric simplicity and austerity of these premodern pieces of furniture anticipate concepts that would later become fundamental in modern European design.

Anderson and Girod's article makes a connection between proto-rationalism and the design of Argentine country-style chairs, pointing out that the proto-rational ideas of vernacular design of semi-nomadic furniture such as the chair anticipate key features of the Modern Movement in Europe.

The concept of proto-rationalism in the article refers to the austerity and geometric simplicity of gaucho design, which is strikingly similar to the functionalist and minimalist design promoted by the Modern Movement in architecture and furniture design in Europe in the early 20th century. The term suggests that these functional and austere forms of design, devoid of unnecessary ornamentation, already existed in rural cultures in Argentina, long before these principles were formalized in Europe by the great academies or universities.

These design forms were not influenced by European tradition, but emerged from a direct interaction with local materials and needs in Argentina. This design typology, like the gaucho matera chair, has a minimalist and austere geometry that relates to the ascetic life of the gaucho, using indigenous materials such as wood from the fields of the humid pampas and braided leather, reflecting a rational resolution of the aesthetic and functional needs of the rural environment.

On the other hand, the relationship between the proto-rationalist chair and African masks is very interesting, since an analogy is established between the proto-rationalist design of the Argentine country-style chair and African masks. This comparison focuses on the geometric abstraction that both art forms share, and how both anticipate concepts that were later central to the Modern Movement in Europe, particularly Cubism and the Bauhaus.

African masks, with their minimalist and synthetic geometry, influenced artists such as Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), especially during his so-called “African Period.” These masks displayed a simplicity of form and geometric purity that were considered proto-rationalist. Similarly, the design of the Argentine country chair, with its austerity and simple geometry, reflects a proto-rationalist abstraction, but applied in the context of Argentine vernacular and rural design.

Both objects, the chairs and the masks, are examples of how non-Western cultures developed design principles that were later admired and adopted by avant-garde movements in Europe. In the case of the African masks, Picasso was inspired by their abstraction to develop Cubism, while the proto-rationalist design of the gaucho chair is an example of how functional and simple forms were already present in rural cultures before being formalized by the Bauhaus School.

The relationship between the two lies in the fact that both typologies—the Argentine chairs and the African masks—show a design based on simplicity and functionality, with a strong symbolic and aesthetic charge that anticipates the concepts of geometric abstraction and minimalism of modern design known as the Modern Movement in Architecture and furniture design.

The analysis presented by Anderson and Girod on the relationship between proto-rationalism in the design of Argentine gaucho chairs and African masks has a valid theoretical basis from the point of view of art history, anthropology and design, although it is a rather particular approach that seeks to draw deep connections between very different cultures.

The idea of proto-rationalism applied to vernacular design is consistent with the history of design and architecture. In many cultures, pre-modern design solutions were rational in the sense that they were functionally adapted to the conditions of the environment, available materials, and usage needs. In this sense, the gaucho-style chair, with its simple geometry and local materials such as leather and wood, represents a rational response to the needs of the Argentine rural environment.

In terms of design, many objects that we now consider part of modernism or functionalist design have their roots in artisanal and vernacular traditions that prioritized utility over ornamentation. The Bauhaus School, for example, promoted these values, as did the Shaker chair tradition in the US, which also valued austerity and functionality.

However, while African masks had a ceremonial, ritual and spiritual context, Argentine gaucho chairs were functional objects with an everyday purpose. Although both may be proto-rational in their geometric approach and adaptation to specific needs (in the case of masks, the symbolic need; in chairs, the functional need), they are objects of a very different nature. The parallel between the geometric abstraction of the masks and the design of the chairs is more an attempt to highlight that non-Western cultures already had advanced design principles before they were theorized in Europe.

Design anthropology recognises that in many cultures, aesthetics and function are linked, and this is the case in both Africa and Argentina. However, the connection between these two specific cultures (African and Gaucho) is more of a parallel than a mutual influence. The comparison with African masks is interesting from a stylistic and anthropological perspective, although differences in function and cultural context must be taken into account. Both examples show how design in different parts of the world was able to anticipate what would later be known as modern design, reinforcing the idea that design innovation is not exclusive to Europe, but a global phenomenon. In short, the ideas proposed are consistent with the principles of design and anthropology, although the relationship between chairs and African masks is more conceptual than direct.

The Bauhaus and other modernist design movements borrowed many ideas from non-Western cultures and vernacular design. For example, the simple, functional forms seen in Bauhaus furniture, designed by masters such as Marcel Breuer (1902-1981), are based on the belief that form follows function. This principle was already found in many rural cultures, which, out of necessity, created functional, geometrically simple furniture. The gaucho design of the Matera chair can be considered a vernacular antecedent of these ideas; as an anthropological and cultural principle, the adaptation of objects to the local context is a constant in the history of global design.

From an anthropological perspective, both forms of design – African masks and gaucho chairs – share a common element: they are products of a deep relationship between culture and object. In the case of African masks, their geometric shape is linked to rites and beliefs, while gaucho chairs reflect rural living conditions, the use of local materials and the need for semi-nomadic people to adapt to the environment.

Although the rural environment and the life of the gaucho are mentioned, a deeper exploration of how gaucho culture, with its semi-nomadic way of life, its relationship to the land and local materials, and its resistance to colonization, directly influenced the rationality behind the designs is missing. Gaucho chairs were not only rational in terms of geometry and materials, but were also the product of a specific philosophy of life and value system. For example, the gauchos' value of self-sufficiency and adaptability, their economy of resources, and their ability to make the most of what was available in nature, are principles that deeply influence the design of these objects. These social and cultural considerations are intimately linked to what could be called semi-nomadic proto-rationalism.

When referring to the semi-nomadic way of life in the context of gauchos, it refers to a lifestyle characterized by constant mobility, but not entirely nomadic. Gauchos were people who moved around regularly, but not continuously or without a fixed home, as would be the case with true nomads. Gauchos moved frequently across the vast plains of Argentina, Uruguay, and Brazil (especially in the Rio Grande do Sul region) due to their work with cattle. They often traveled great distances to herd cattle, hunt wild animals, or find new pastures, but they did not always live on the move. They had specific areas where they spent seasons, and some even had homes or bases where they returned periodically.

Gauchos were highly dependent on the natural resources of the regions in which they moved. They used horses for transport and work, lived off beef, and obtained other resources such as leather and food from their immediate surroundings. This direct relationship with nature required a life that combined mobility and the ability to settle temporarily to take advantage of the resources of a place. Although not completely nomadic, gauchos were not tied to a life in towns or cities with stable infrastructure. Their housing was often improvised or temporary (the ranch), and this is also reflected in their austere lifestyle (the same was true of their furniture). They were self-sufficient people, able to make their tools and furniture from materials they found in the countryside. The gaucho chair or matera chair is an example of a simple, practical, and easy-to-build object that fits with this adaptable lifestyle.

The work of the gaucho was related to cattle raising, hunting, and seasonal activities. This type of life did not require gauchos to remain in one place for long periods, allowing them to move as needed, such as herding cattle or participating in seasonal tasks such as slaughtering. This lifestyle gave them flexibility, but also meant that they were not absolute nomads, as they returned to specific areas depending on the season or work; hence, being semi-nomadic, their furniture was semi-nomadic.

The semi-nomadic way of life of the gauchos combined elements of mobility with moments of temporary settlement. This way of life allowed them to take advantage of the resources of the environment and quickly adapt to changing weather conditions or work requirements. Although they were not total nomads, their mobility and self-sufficiency were crucial aspects, which influenced their material culture, such as simple and functional furniture that they could easily make and use in their daily lives, such as chairs and other handcrafted objects.

As for the relationship with technological and artisanal development, the minimalist semi-nomadic proto-rationalism in the design of vernacular furniture – such as the matera-gaucha chair – is also deeply related to local artisanal techniques and available technology. Although the use of indigenous materials, such as leather and wood, is mentioned, there is not enough discussion on how artisanal techniques and technological limitations of the time influenced the design of these chairs (which will be a likely sub-topic of Girod’s PhD thesis research). It would have been interesting to explore how production methods (e.g. handwork and available tools) limited or influenced the forms of design, and how this reflected a kind of practical rationality that is aligned with the concept of minimalist semi-nomadic proto-rationalism.

The semi-nomadic lifestyle of the gauchos has a deep relationship with proto-rationalism in the design of objects and furniture, including the chair-materas, due to the need to create practical and adaptable solutions to a changing environment. This lifestyle directly influenced the way the gauchos designed and used their tools and furniture, prioritizing functionality and simplicity over ornamentation, which is key to the concept of minimalist semi-nomadic proto-rationalism.

Proto-rationalism is characterized by a design that responds to basic needs and environmental conditions in a logical and efficient manner. In the case of the gauchos, the way of life required objects to be practical, transportable, and multifunctional. The chair-materas, for example, are lightweight, easy to make from local materials (such as wood and leather), and designed to be highly functional in a rural environment, where mobility was key. This approach is rational because it eliminates all decorative excess, focusing on the pure utility of the object. Thus, the chair-materas reflect a proto-rationalism by solving the needs of the gauchos directly, without unnecessary additions, with a simple and austere design.

Gauchos relied on materials available to them in the natural environment, such as wood from local trees (algarrobo, ñandubay and others depending on the geographical areas where they lived) and leather from the animals they raised. This efficient use of resources is also a reflection of proto-rationalism, as design was closely linked to what was available at the time, optimizing raw materials without the need to import or seek external materials.

Having to move frequently, gauchos learned to use resources pragmatically, which promoted a minimalist and functional aesthetic. In terms of design, this corresponds to a rationalization of materials and construction methods, making objects durable but also adaptable.

Proto-rationalist design is also evident in the structural simplicity of gaucho furniture, such as the matera chair, which not only had to be functional, but also easy to construct, disassemble, or transport. Gauchos could not carry heavy or complicated objects, so design solutions needed to be adaptable and versatile. This simplicity in form and construction is a fundamental principle of proto-rationalism.

The semi-nomadic way of life required objects to be mobile and sturdy. Chairs, stools, and other furniture had to meet these conditions, which promoted an austere, geometric, and rational aesthetic. Gauchos were self-sufficient, meaning that many of the objects they used, such as chairs, were made by themselves or by local artisans. This is also in line with proto-rationalism, as objects were not only functional, but also durable and easy to maintain due to their simplicity.

By not relying on an industrial infrastructure, the design had to be rational in the sense that anyone could make it with the tools and materials available. This not only made the objects highly useful, but also easily replicable and repairable.

Although local materials such as wood and leather are discussed, not enough emphasis is placed on how the use of these materials reflected a symbiotic relationship with the environment. The ability of vernacular rural designers to use sustainable and renewable materials is at the heart of rational design in many pre-industrial cultures that had an ecological concept of man's relationship with the natural environment (La Pachamama or Mother Earth Goddess in Latin America).

This aspect could have been linked to current trends in sustainable design, showing how the proto-rationalism of the gaucho chairs could be seen as a precursor to contemporary principles in environmentally conscious design that make up the most advanced theories of design in developed countries today, ecodesign.

44.This connection between furniture design and cultural symbolism is not sufficiently explored in the article. For example, materials such as leather or wood, and their relationship to livestock or land, might have had deeper meanings in gaucho life.

The semi-nomadic lifestyle of the gauchos profoundly influenced proto-rationalism in the vernacular design of their furniture. This lifestyle promoted a practical, self-sufficient and functional mindset, where objects had to meet multiple criteria: being easy to construct, using local materials, being transportable and durable. This functional simplicity and adaptation to the environment is at the core of proto-rationalism, which in this context reflects a type of organic design that developed long before the formalization of these concepts in European modernism, such as at the Bauhaus.

On the other hand, the semiotic analysis carried out in the article on the Argentine country-style chair focuses on the relationship between the functionality, aesthetics and symbolism of the object in the context of gaucho and criollo culture. Design objects, such as chairs, speak in a non-verbal language, which implies that, through their form, materials and structure, they transmit meanings that go beyond their simple practical function. This language involves both the aesthetic and the symbolic. Paraphrasing Knapp

45Nonverbal language is an essential form of human communication, the interpretation of which depends on gestures, postures and facial expressions as well as the cultural context in which it occurs. The interaction between verbal and nonverbal signals allows for a deeper understanding of individuals' intentions and emotions.

In the previous article, entitled A Brief Western History of Cult Furniture Design. The Chair (Part 3), written in ArtyHum No. 90, by Anderson and Girod, three fundamental values were identified in the analysis of the chair, although in reality there are four:

-Functional-use-value:This value refers to the practical utility of the chair as an object for sitting. Its design is adapted to the needs of the gaucho, such as his semi-nomadic lifestyle and his daily activities in a practical sense (drinking the infusion: mate).

-Aesthetic-use-value:The chair is not only useful, but also has an aesthetic value. The materials used, such as native wood and braided leather, and the simple, minimalist design, give it a particular beauty that is part of Creole culture.

-Symbolic-use-value:In addition to its function and aesthetics, the chair has a deep symbolic value, as it refers to the gaucho identity and to the rural history of Argentina. The use of local leather and wood evokes the connection with the land and the culture of asado (barbecue) that comes from working in cattle ranches, central elements of the life of the gaucho.

It is mentioned that in pre-modern design (such as the gaucho chair), the values of utility (functional value) and beauty (aesthetic value) were united. There was no separation between the functional and the aesthetic, since both aspects complemented each other in the design object.

The minimalist geometry and simplicity of the gaucho chair-matera design are based on the functional-use-value associated with its functionalist proto-rationalism (practical, useful, light, transportable) and a symbolic-aesthetic-use-value in the leather seat associated with culture (barbecue and folk music) and cattle work. The analysis also touches on the capitalist-use-value or capitalist-exchange-value (this is the fourth value mentioned above). The chair, being an object

46 linked to rural and artisanal production, it represents an object and not an industrial product (be careful with these concepts, you must know how to differentiate).

The article entitled The Argentine Country Style Chair. When Art Theory Becomes a Theoretical Paradigm to Explain the Typology of the Proto-Rationalist Country Style Chair (or Gaucho Style) in the Argentine Republic, published in the magazine ArtyHum Nº 85; written by Anderson and Girod, is part of a broader research on the craft design and historical evolution of the country style chair in the Argentine Republic, particularly related to the figure of the gaucho and the colonial influences of the Iberian Peninsula.

The paper delves into how the design typology of the gaucho chair is linked to the Spanish and Portuguese colonies in Latin America, pointing out the influence of colonial heritage on Creole design. It analyzes some of the paintings and caricatures of the artist Florencio Molina Campos where iconographies of this type of gaucho chair (materas) are exemplified by the painting, showing how his vernacular, minimalist and proto-rationalist designs anticipate certain concepts of the European Modern Movement, such as those of the Bauhaus.

Figure 4.

Work “Cantando bonito”, by Florencio Molina Campos for his series of almanacs of the Alpargatas SAIC factory © GGM and FFMC (Télam). Source: Diario Infobae, Republic of Argentina.

Figure 4.

Work “Cantando bonito”, by Florencio Molina Campos for his series of almanacs of the Alpargatas SAIC factory © GGM and FFMC (Télam). Source: Diario Infobae, Republic of Argentina.

The gaucho chair, with its austere and functional geometry, resembles the proto-rationalist style of rural cultures, such as the Shaker community in the USA, which is related to a practical and functional approach - or use-value - of local materials.

It is analyzed how these chairs, despite their simplicity and functionality, also have a great aesthetic-use value and symbolic-use value, since materials such as leather and vegetable fibers refer to the history and rural economy of Argentina, in particular livestock production and the culture of the asado criollo (the aesthetics lies in its simplicity and minimalism that gives it a beauty in simplicity and its symbolism lies in the tiento or braided leather of cow (bovine cattle) or foal (equine cattle) which symbolically refers to the criollo livestock in the estancias and going further refers to the wild cattle).

47). The article concludes that this type of design not only anticipates but is also an integral part of Argentina's cultural heritage, symbolizing a symbiosis between the functional, the aesthetic and the symbolic.

The photograph of the country-style chair seen on

Figure 5 is analogous to the iconographic image of the painting on

Figure 4; it not only represents the gaucho, but can also be seen as an object (not a product) of cultural belonging that generates an emotional identification and roots in the Creole culture. This identity value could be linked to the way in which people see themselves reflected in these objects, as an extension of their way of life, traditions and values (an intangible cultural heritage).

48.

The country-style chair can also be seen as a vehicle of collective memory. Beyond their functional, aesthetic or symbolic value, these objects act as witnesses of history, encapsulating events and practices that marked generations of rural inhabitants in Argentina. Analyzing how these objects preserve and transmit historical memory could deepen the analysis. This value, linked to nostalgia and legacy, could complement the semiotic analysis in terms of how objects transmit and preserve the history of the Argentine pampas.

Ritual or ceremonial value:Although the symbolic value of the chair is mentioned, it could be relevant to explore its role in social rituals. In rural contexts, objects such as the chair can have a ceremonial meaning in everyday or festive practices, such as drinking mate, playing folk guitar, or eating roasted meat. This ritual or ceremonial value can broaden the analysis by considering how the chair is not only a utilitarian object, but also a key component in moments of social interaction, loaded with symbolism that reinforces community ties (such as gastronomy).

In the semiotic analysis the most relevant points with a minimalist and semi-nomadic proto-rationalist vernacular design:

-The object as a non-verbal language: It is stated that design objects, such as chairs, speak in a non-verbal language, which implies that, through their form, materials and structure, they transmit meanings that go beyond their simple practical function or use-value. This language involves both the aesthetic and the symbolic. Four (4) fundamental values are identified in the analysis of the chair:

-Functional-use-value:This value refers to the practical utility of the chair as an object for sitting. Its design is tailored to the needs of the gaucho, such as his semi-nomadic lifestyle and daily activities.

-Aesthetic-use-value:The chair is not only useful, but also has an aesthetic value. The materials used, such as native wood and braided leather, and the simple, minimalist design, give it a particular beauty that is part of Creole culture.

-Symbolic-use-value:It refers to the gaucho identity and to the rural history of Argentina (something like the cultural heritage that represents the work with cattle). The use of local leather and wood evokes the link with the land and the culture of the barbecue (among other evocations), central elements of the life of the gaucho, the cattle rancher and the landowner.

The semiotic analysis focuses on the four main values: functional-use-value, aesthetic-use-value, symbolic-use-value and capitalist-exchange-value. While these encompass a substantial part of the meaning of the Argentine country-style chair, there may be other aspects not analyzed or not sufficiently explored that could enrich the semiotic analysis.

The unity between function and aesthetics present in the gaucho matera chair is mentioned in hypothesis no. 1 or premodern: where the values of the useful (functional value) are united to the kalokagathia, which is equivalent to saying that the beautiful (aesthetic value) and the good (ethical value) were united.

51. There was no separation between the functional, the aesthetic and the morally ethical, since all these aspects complemented each other –and still do in existing rural areas- in the design object. Since they can still be bought, or ordered to be built by artisans, as objects and not as products; that is, if a craftsman is commissioned to build them and is paid (with money obviously) we would not be buying them as a product even if it is a commodity acquired in a capitalist way (since it is a personal order). We would be acquiring them as an object of artisan design and they do not reach the status of an industrial product. Because their manufacture is not truly industrialized or massive (although it is not industrialized, it could be a non-industrial mass manufacture as was the Thonet chair No. 14, but it is not equivalent to that either); so, what is the gaucho matera chair? Answer: it is an object that operates more like a barter with money (capitalist currency).

Barter is a system of exchange where goods or services are exchanged directly, without the use of money. In this context, when you commission a craftsman to make a handmade chair and pay with money, it is not strictly barter, as you are using a monetary medium originating in capitalism, rather than exchanging one good for another. However, one could argue that the process has elements of barter, in the sense that you are exchanging money for a personalized good that has a specific value. So, although it is not barter in its classical definition, the personal relationship and the uniqueness of the object can lead to a richer exchange experience than true, ancient barter, but of lower status than the purchase of an industrial product (in the capitalist market). The analysis also touches on capitalist exchange-value (being purchased from a craftsman who sells it and a user who buys it), it represents a commodity that circulates in the capitalist market.

The gaucho matera chair is a symbol of identity and a cultural product that transcends its utilitarian function to become an object loaded with historical and social meaning (aesthetic and symbolic) that circulates in a capitalist market. Hence we say that it is an object with a capitalist exchange value.

We could add an ecological value - or environmental sustainability value - since the local materials used in the manufacture of the chair (wood, plant fibers, leather) are analyzed, the ecological value or sustainability of these designs could be explored. How is the production of these chairs related to the natural environment? Nowadays, sustainability is an important criterion for evaluating the design of objects. Analyzing this value would allow us to understand how the production of these chairs respects (or not) the ecological balance and how it can become an example of sustainable design (what in the most advanced theories of the developed world has been defined as ecodesign).

52.

The semi-nomadic lifestyle of the gauchos profoundly influenced proto-rationalism in the design of their furniture and tools. This lifestyle promoted a practical, self-sufficient and functional mindset, where objects had to meet multiple criteria: being easy to build, using local materials, being transportable and durable. This functional simplicity and adaptation to the environment is at the core of proto-rationalism, which in this context reflects a type of organic design that developed long before the formalization of these concepts in European modernism (such as at the Bauhaus).

The term semi-nomadic refers to a lifestyle that combines aspects of sedentary and nomadic life, where people move periodically, but not constantly, maintaining ties to a fixed place. This concept is used in anthropological and sociological studies to describe communities that depend on hunting, gathering, or agriculture, moving based on the availability of resources. For a more formal academic definition, one can consult André Leroi-Gourhan's book Anthropology of Nomadic Peoples, published in 1971, where the characteristics of nomadic and semi-nomadic societies are discussed, as well as their relationship with the environment and the design of tools and furniture. Another reference on gauchos is José Luis Romero's 1946 book Los gauchos: historia y cultura de un pueblo, which offers an in-depth analysis of gaucho life and how their semi-nomadic lifestyle influenced their material culture.

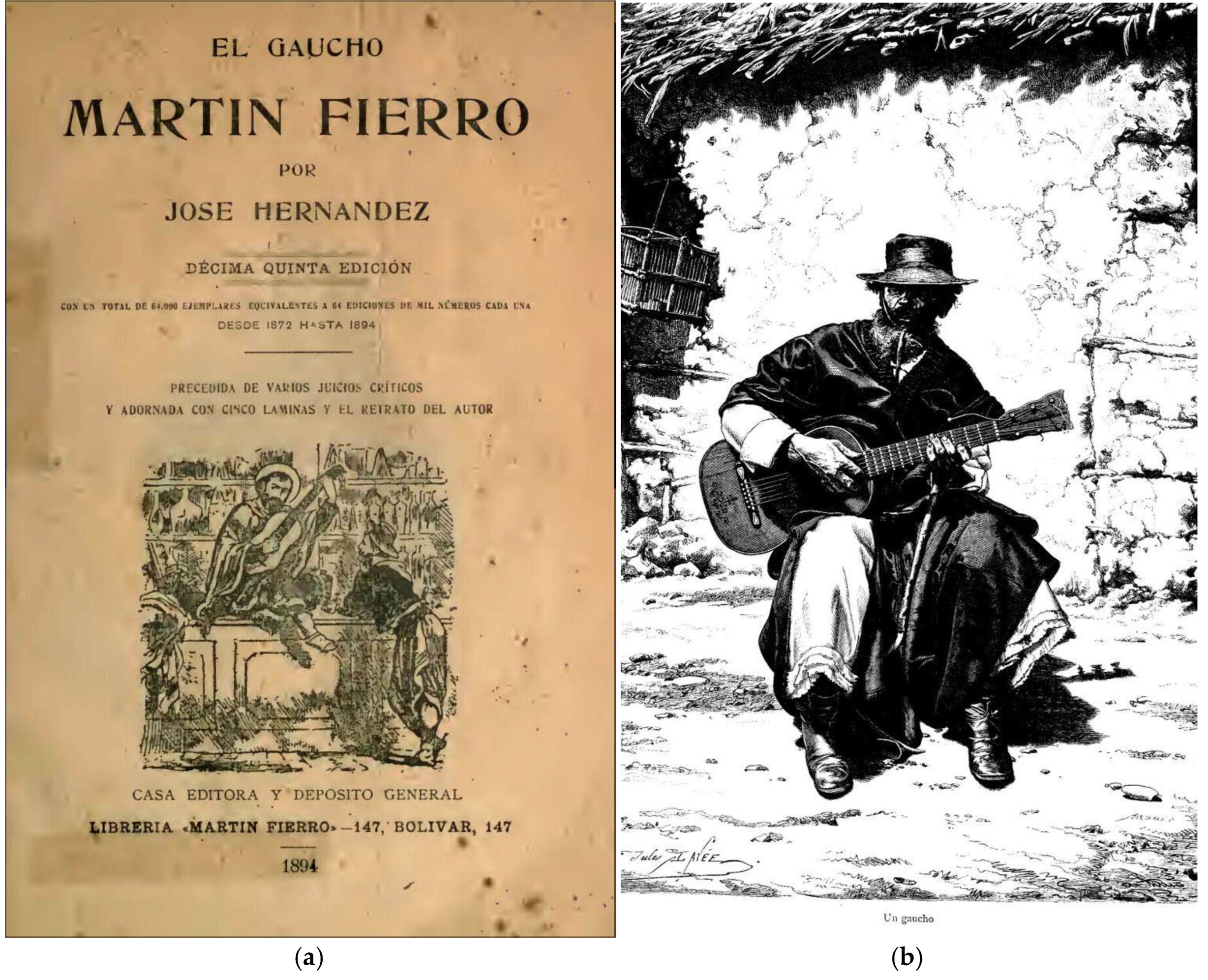

The literature of the text El Gaucho Martín Fierro (1872), written by José Hernández (1834-1886) in the 19th century, is an epic poem depicting the life of gauchos in Argentina. This work reflects the cultural identity of the gauchos, their struggle for freedom and their customs, including their relationship with the environment and their semi-nomadic lifestyle, highlighting values such as freedom, justice and resistance, intrinsic aspects of gaucho life. In this context, the mate chairs, used in gaucho coexistence, exemplify a practical approach, as they are transportable and designed to facilitate life in the countryside, allowing one to enjoy a mate in different places, while being functional and suitable for their lifestyle.

Furthermore, the simplicity and functionality of the mate chairs reflect proto-rationalism, where design is a direct response to the needs of the environment. These chairs adapt to the context and cultural practices of the communities that use them. Molina Campos' paintings portray rural and gaucho life in Argentina, capturing the customs and traditions of the gauchos, as well as their environment. In his works, the representation of gaucho life is observed, where gauchos often appear enjoying a mate in their mate chair, emphasizing the importance of these objects in gaucho culture, as they are not just furniture, but elements that tell stories about identity and coexistence in the countryside.

José Hernández’s literature, Molina Campos’ paintings and the Materas chairs are intrinsically connected through the representation of a semi-nomadic lifestyle. Together, they offer a comprehensive view of gaucho culture, highlighting the functionality, adaptability and deep bond with the environment that defines this community. This relationship not only illustrates the gaucho identity, but also reflects a design approach that values simplicity and utility in everyday life.

Figure 6.

(a,b) On the left, cover of the famous literary work El gaucho Martín Fierro (edition: 1894) by the author José Hernández. Martín Fierro is the protagonist of the gaucho story written in verse in El Gaucho Martín Fierro (1872) and La vuelta de Martín Fierro (1879), by José Hernández. He is a gaucho from the Argentine pampas who finds himself fighting a Creole duel and killing a man. From that moment on, he must face the social injustices of the time. In the first book, Martín Fierro finds himself separated from his family and in the second book he is reunited with his children. Source: This is a faithful photographic reproduction of a two-dimensional public domain work of art. The work is in the public domain in the Argentine Republic.

Figure 6.

(a,b) On the left, cover of the famous literary work El gaucho Martín Fierro (edition: 1894) by the author José Hernández. Martín Fierro is the protagonist of the gaucho story written in verse in El Gaucho Martín Fierro (1872) and La vuelta de Martín Fierro (1879), by José Hernández. He is a gaucho from the Argentine pampas who finds himself fighting a Creole duel and killing a man. From that moment on, he must face the social injustices of the time. In the first book, Martín Fierro finds himself separated from his family and in the second book he is reunited with his children. Source: This is a faithful photographic reproduction of a two-dimensional public domain work of art. The work is in the public domain in the Argentine Republic.

On the right, an illustration of a gaucho. Source: The Earth and Man: A Picturesque Description of Our Globe and the Different Races that Inhabit It by Fiedrich von Hellwag - Montaner and Simon editors. Image by an unknown author from 1886.

Discussion

Hypothesis based on Hegelian Dialectics applied to the probable process of syncretism in furniture design in America.

(a) Thesis:The mythical-cosmogonic aesthetics of pre-Columbian peoples (15,000 BC - 1492 AD) constitute a foundational paradigm in the production of artifacts and design objects in America. In these societies, objects not only fulfilled practical functions, but were deeply integrated with cosmology, spirituality, and natural cycles. Pre-Columbian designs, such as ceremonial thrones and other carved artifacts, evidence a symbiotic relationship between man, nature, and the cosmos. Pre-Columbian architecture not only fulfilled practical functions, but also reflected complex social and religious structures, and ceremonial objects were instruments of connection with the sacred. This connection imbued objects with profound spiritual and cultural meaning, turning them into manifestations of an aesthetic deeply linked to a mythical-cosmogonic order.

(b) Antithesis:With the arrival of the Spanish colonizers in 1492, and the imposition of the absolutist monarchies, a new aesthetic-cultural model emerged in America. This model was linked to colonial furniture, which reflected the hierarchical and ostentatious values of the absolutist-monarchical order. It is mentioned that the throne of the Catholic Monarchs reflected a centralized and hierarchical power, decorated with elements that symbolized the greatness of the monarchy. This design, influenced by European courtly-monarchical aesthetics, represented a cultural clash with pre-Columbian traditions, prioritizing luxury and power over spiritual and practical connections. In this context, local artisans began to integrate Iberian materials and techniques, transforming traditional practices into a forced syncretism.

(c) Synthesis of the gaucho ethos:Argentine gaucho design of the 19th century, specifically the silla matera, emerges as a Hegelian synthesis that evidences a cultural syncretism between pre-Columbian traditions, the Spanish colonial legacy and the conditions of the Argentine rural environment. The silla matera, described as having an austere and functional design that reflects the semi-nomadic life of the gaucho, using local materials such as wood and leather, integrates the values of the useful, the beautiful and the symbolic. This minimalist proto-rationalist design solves the practical needs of the rural environment, while preserving aesthetic and symbolic elements of pre-existing cultures.

Unlike pre-Columbian objects, which were imbued with cosmogonic and spiritual meaning, the matera chair focuses on solving practical problems. The symbolism it possesses is more cultural than spiritual, reflecting the gaucho ethos, but without a direct link to the mythical-cosmogonic traditions of the native peoples.

The reasons why we come to affirm that the design of objects, artifacts (even furniture), as in the Indo-Ibero-American chair-matera, is the result of the semi-nomadic proto-rationalist minimalist syncretism are discussed below.

Cultural syncretism in Latin America developed in a context of colonialism and cultural resistance, marked by the fusion of indigenous and Hispanic traditions. This process integrated elements of pre-Hispanic worldviews, such as those of the Aztecs, Incas and Mayans, with European practices and beliefs, especially those linked to Catholicism. This cultural amalgamation gave rise to phenomena such as religious mestizaje, visible in expressions such as the Virgin of Guadalupe, which symbolizes both the continuity of indigenous traditions and their adaptation to the structures imposed by the conquistadors. The incorporation of indigenous values into European practices allowed local communities to reconfigure their cultural identities in the midst of colonial domination.

In the literary and artistic sphere, Latin America reflected this fusion through a unique creative production. Authors such as Rubén Darío and José Martí criticized colonial structures and celebrated an aesthetic that broke with traditional Hispanicist paradigms. Rubén Darío, considered the greatest representative of modernism, knew how to mix elements of Hispanic-indigenous cultural fusion with the European avant-garde, managing to renew the literature of the New World. For his part, Martí proposed an emancipatory discourse, anticipating the post-colonialist ideas that would later be fundamental for the modernists. In the 20th century, figures such as the Mexican poet and essayist Octavio Paz (1914-1998), the Chilean poet Pablo Neruda (1904-1973), the Chilean poet and Nobel Prize winner for Literature Gabriela Mistral (1889-1957) and the Mexican painter Frida Kahlo (1907-1954) transformed the artistic and literary panorama, providing it with a hybrid voice –in the words of the writer and anthropologist born in Argentina in 1939: García Canclini- and universal that marked the reconciliation of historical tensions between the indigenous and the European. This artistic and literary production not only reflected the fight against the colonialist practices of the local elites, but also served as a vehicle for the revaluation of silenced cultural elements.

According to Canclini: “Hybridity is a fundamental characteristic of contemporary cultures, where elements from different traditions, times and spaces mix and give rise to new meanings and significances.”

53

Syncretism, as explained by Colombian philosopher Yuri Gómez, is not only a historical phenomenon, but a continuous praxis that allows humanity to bring together what is different in each act of creation. This practice makes possible the integration of seemingly incompatible elements, generating cultural results that challenge traditional categories and broaden the horizons of knowledge. The pictorial works of artists such as the Mexican muralist Diego Rivera (1886-1957) and the Chilean architect, painter and poet Roberto Matta (1911-2002) illustrate this principle; through their productions, these creators captured the tensions of class, race and power, turning their works into mirrors of the social conflicts that crossed their respective eras. Rivera, with his monumentalism and focus on social struggles, and Matta, with his surrealism loaded with philosophical and political implications, exemplified how art can be a vehicle for cultural analysis and transformation.

Mexico holds a prominent place as the epicenter of Latin American cultural syncretism. This country succeeded in developing in an exceptional way the integration of indigenous and European elements in all areas of culture, from religion to art. Events such as the Day of the Dead are an example of cultural fusion in the religious sphere, where pre-Hispanic beliefs about death are fused with the Catholicism brought by the colonizers. In art, muralists such as Diego Rivera, the Mexican painter and writer David Alfaro Siqueiros (1896-1974) and the cartoonist, caricaturist and painter of Mexican muralism José Clemente Orozco (1833-1949) reinterpreted European values from a mestizo perspective, while artists such as Frida Kahlo and the Mexican painter Rufino Tamayo (1899-1992) explored the complexities of Mexican cultural identity. This syncretism not only consolidated Mexico as a reference in art and culture, but also served as a model for other countries in their search for a hybrid identity that embraced both their indigenous roots and their European heritage.