1. Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has had a significant impact on global health, society and economy since its emergence in late 2019 [

1].

Mortality data provide important insights into the severity and progression of disease and enable the identification of important risk factors such as age, pre-existing health conditions and socioeconomic factors that predispose individuals to adverse outcomes, thus supporting the implementation of tailored interventions to protect or treat specific populations at increased risk [

2]. Analyzing mortality trends for a particular disease is essential for evaluating healthcare system capacity and care efficiency. Such analyses indicate where additional human resources are needed, including doctors, nurses and other healthcare professionals, as well as technical resources such as hospital beds, ventilators, essential medical supplies and personal protective equipment [

3]. Monitoring the impact of novel vaccines and therapeutic interventions on mortality rates also informs clinical practice by guiding the adoption of the most effective treatment strategies [

4]. Detailed mortality data also plays a pivotal role in epidemiological modeling and forecasting, enhancing the reliability of predictions regarding future disease waves and the associated demands on healthcare infrastructure [

5]. Beyond addressing the immediate challenges of a pandemic like COVID-19, the collection and analysis of mortality data contribute to constructing a robust knowledge base for future global health threats. This rationale can be used by policymakers and healthcare administrators to enhance preparedness and resilience against emerging crises [

6]. In summary, the thorough study of mortality data serves as a cornerstone for saving lives, improving health system performance, and fostering resilience in the face of both current and future public health challenges.

Therefore, the purpose of this study is to analyze COVID-19-related mortality in the US during the first five years of the pandemic. Specifically, we examined trends in overall mortality, as well as demographic factors such as gender, age and place of occurrence, to identify patterns and disparities in COVID-19 mortality. This analysis is expected to provide valuable insights into the broader impact of the pandemic on the general population, representing a reliable basis for controlling the spread of new variants or future infectious outbreaks [

7].

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a retrospective descriptive study accessing the "Provisional Multiple Cause of Death" database maintained by the US National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) through the Wide-Ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (WONDER) interface [

8]. This platform provides comprehensive nationwide information extracted from death certificates, including demographic data, geographical details and the primary underlying causes of death. Our analysis focused on records identified by the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) code U07.1, designated specifically for “COVID-19” [

9]. Our digital search encompassed the period from January 2020 to December 2024. Additional searches were conducted to stratify the data by gender, ten-year age groups and place of death, combining these variables with the ICD-10 code U07.1. The resulting data included age-adjusted mortality rates (×100,000) for gender analysis, crude mortality rates (×100,000) for analysis of the ten-year age classes, and total death counts with corresponding percentages for analysis of the place of death. Mortality rates, both crude and age-adjusted, were reported alongside their respective 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). This study was performed in agreement of the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and complied with all relevant local regulations. As the NCHS WONDER is a publicly available, anonymized and freely searchable database, the study was exempt from Ethical Committee approval.

3. Results

According to the NCHS, the total number of COVID-19-related US deaths (ICD-10 code U07.1) was 350,831 in 2020, 416,893 in 2021, 186,552 in 2022, 49,942 in 2023, and 30,483 in 2024, respectively. Cumulatively, the number of deaths for COVID-19 increased by around 19% from 2020 to 2021, but then declined considerably in the following years, by a mean factor of 0.44 (range 0.27-0.61).

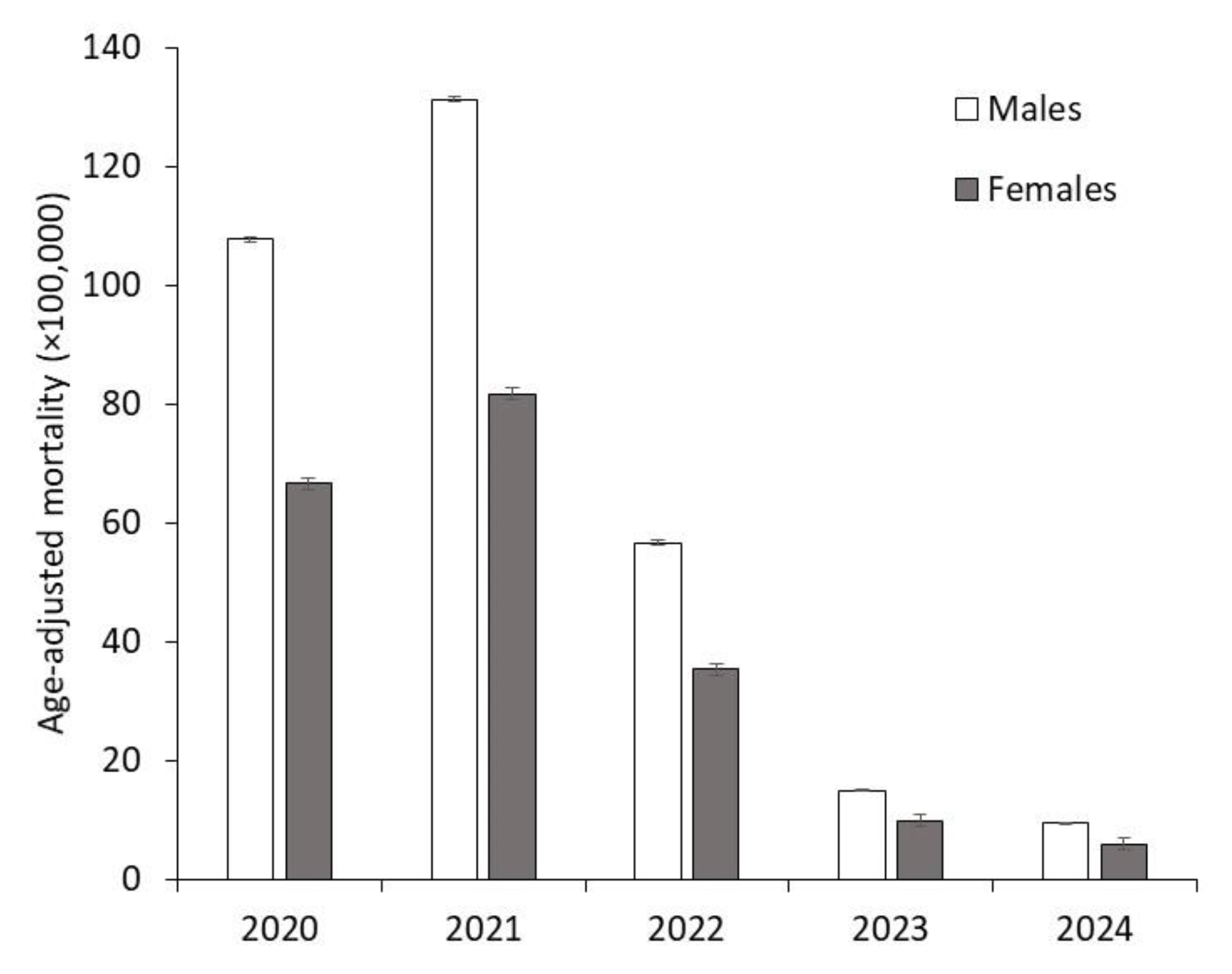

The age-adjusted mortality rates for COVID-19 across the first five years of the pandemic stratified by gender are illustrated in

Figure 1.

Mortality consistently remained approximately 60% higher in males compared to females. The male-to-female mortality ratio was 1.62 in 2020, 1.61 in 2021, slightly decreased to 1.60 in 2022, dropped to 1.52 in 2023, but then returned to 1.61 in 2024.

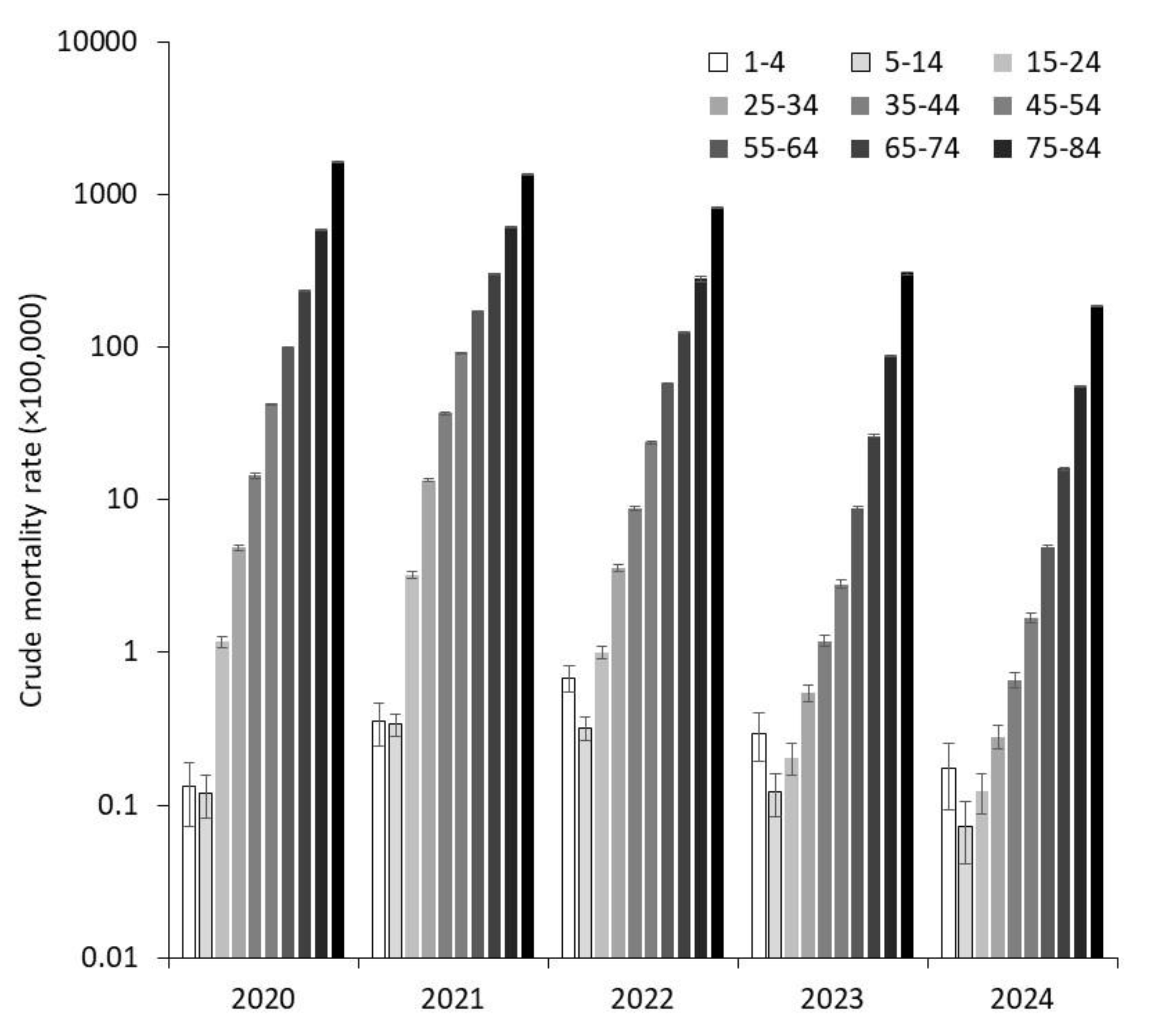

The crude mortality data for age groups are displayed in

Figure 2, showing that crude death rates consistently increased with age across all five pandemic years.

This trend remained remarkably consistent from year to year, highlighting the persistent correlation between advancing age and higher mortality rates. However, a general decline in crude mortality rates was observed across all age groups except the youngest population. Specifically, the ratio of crude mortality between the years 2024 and 2020 showed an increase of +33% in the 1–4 years age group, but significant declines in older age groups, as follows: -39% between 5–14 years, -89% between 15–24 years, -94% between 25–34 years, -95% between 35–44 years, -96% between 45–54 years, -95% between 55–64 years, -93% between 65–74 years, -91% between 75–84 years, and -89% in individuals aged 85 years and older, respectively.

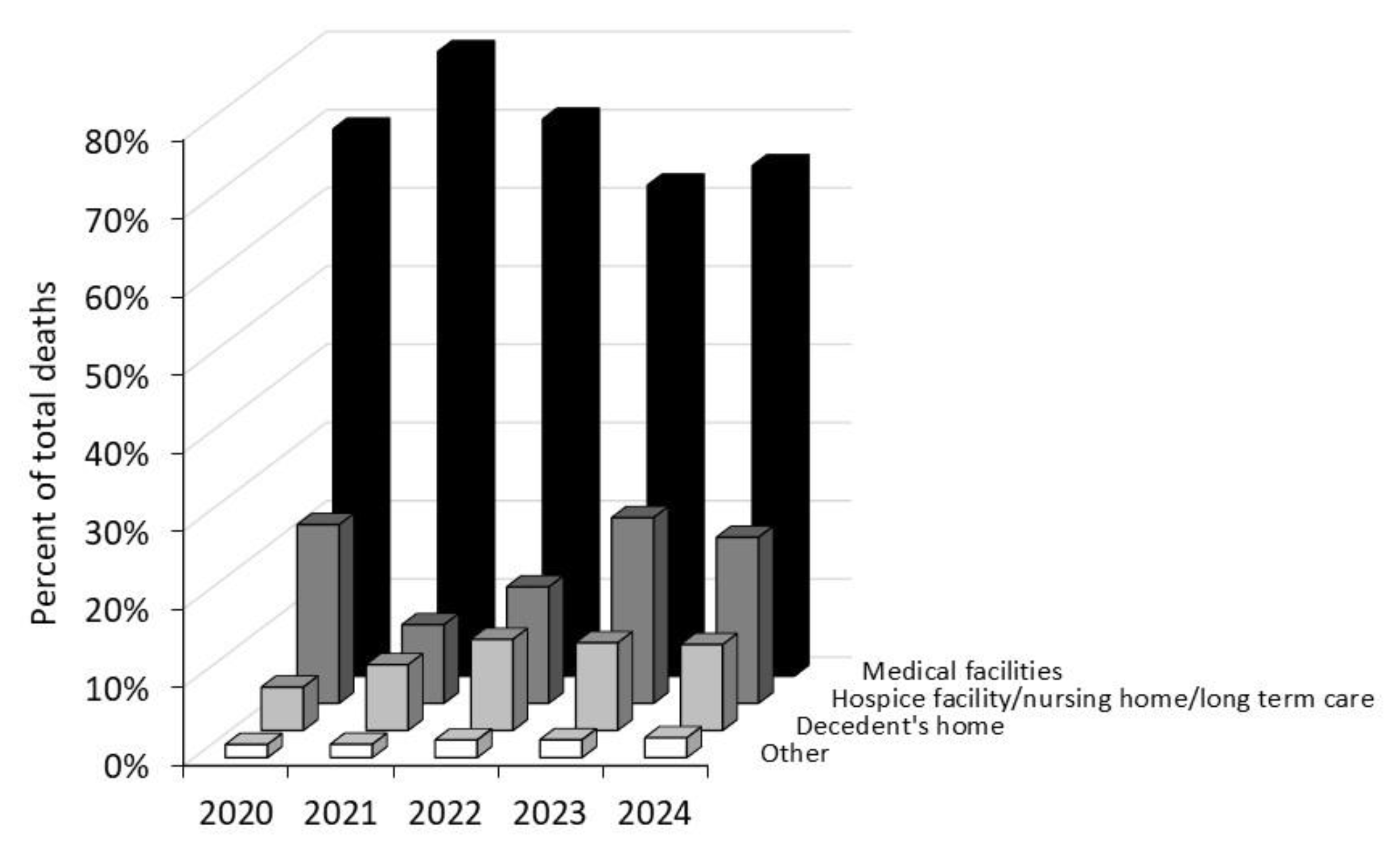

Regarding the place of death, the majority of COVID-19 fatalities occurred in medical facilities (63–80%), followed by hospice facilities, nursing homes, or long-term care settings (10–23%), decedents’ homes (6–12%), and other locations (2–3%) (

Figure 3).

Cumulatively, the percentage of deaths occurring in medical facilities decreased over time, while the proportion of deaths in decedents’ homes nearly doubled between 2020 and 2024.

4. Discussion

The systematic analysis of mortality data for a certain pathology is essential to better understand the trajectory of disease, its demographic impact and trends over time [

10]. The results of our analysis show that COVID-19 mortality in the US varied remarkably across years, gender, age groups and places of death.

The dynamics of COVID-19-related mortality during the first five years of the pandemic reflect the evolving nature of the crisis, with a considerable decline observed over time. This reduction can be attributed to multiple interrelated factors, including the widespread availability of COVID-19 vaccines and the development of natural immunity against the virus [

11,

12], advances in clinical management that have improved and refined the therapeutic arsenal against this life-threatening disease [

13], the high mortality among older and more vulnerable populations during the early pandemic years (2020–2021) which may have further reduced the pool of individuals at highest risk of worse clinical outcome and contributed to fewer deaths in subsequent years, along with the emergence of less virulent variants that has led to a gradual attenuation of SARS-CoV-2 virulence [

14].

Our analysis provides additional evidence that males have been disproportionately impacted by COVID-19, exhibiting consistently higher mortality rates than females (between 52-62%). This gender disparity is likely driven by a combination of biological, behavioral and social factors, such as weaker immune responses in males, higher prevalence of comorbidities among men and lower healthcare-seeking behaviors in males [

15]. However, our findings are consistent with those reported by Ramírez-Soto et al. [

16], who analyzed COVID-19 fatality rates across 73 different countries during the years 2020–2021, and concluded that the infection fatality rate was 40% higher in men than in women (3.17% vs. 2.26%).

Older adults have faced significantly higher risk of aggravation (e.g., intensive care unit [ICU] admission) and mortality due to age-related vulnerabilities, including weakened immune responses, higher prevalence of underlying medical conditions and potentially lower care access [

17,

18]. Nevertheless, our analysis has revealed a differential impact of COVID-19 on very early child (1-4 years) mortality, with a 33% increase observed between 2020 and 2024, although the crude death rate in 2024 was still nearly 70% lower compared to the peak mortality in 2022 for this age group. This indicates that the overall mortality rate for children has dropped far below the highest levels recorded during the pandemic height. This trend is divergent when compared to the mortality rates of other age groups, which showed a considerable decline between 2020 and 2024. One significant factor that may have contributed to the observed trend in early child mortality is the potential misclassification or incorrect attribution of ICD-10 code, especially during the first years of the pandemic, thus leading to potential underestimation of total deaths in 2020. "During the initial wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, several challenges arose regarding the timely and accurate assignment of ICD-10 codes for pediatric deaths. Children often present with atypical or less pronounced symptoms of COVID-19 compared to adults, which could have led to the misidentification of the direct cause of death [

19]. Specifically, some pediatric COVID-19 cases may have been misclassified as other respiratory illnesses, such as influenza or respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infections, which are more commonly diagnosed in children [

20]. As a result, some deaths may have been attributed to these conditions rather than directly to COVID-19, potentially distorting the accuracy of mortality data and hindering a comprehensive understanding of the pandemic’s impact on pediatric health.

Beyond demographic disparities, the place of death provides critical insights into the role of the healthcare system during the pandemic. A substantial proportion of deaths occurred in medical facilities, underscoring the immense strain on hospitals during peak pandemic waves. This observation is consistent with early data reported by the US Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) COVID Task Force [

21], which indicated that when ICU bed usage nationwide reached 75% capacity, an estimated 12,000 additional excess deaths occurred over the subsequent two weeks. Nevertheless, the notable proportion of deaths occurred in nursing homes, hospice facilities and private residences highlights the extensive impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on vulnerable populations outside traditional hospital settings [

22].

We finally acknowledge that this study may have some limitations. As a retrospective observational analysis, this study is subject to inherent bias associated with the reliability of secondary data sources. Exclusive reliance on death certificates from the NCHS introduces the potential for misclassification and incomplete reporting, especially during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic when diagnostic accuracy was constrained. While the study examines mortality trends across demographic groups, it cannot account for key confounding factors such as socioeconomic disparities, care access, vaccination status and the impact of SARS-CoV-2 variants, as these variables are unavailable in the WONDER database.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the results of our analysis indicate that COVID-19-related mortality in the US reached its peak in 2021 and has significantly declined in subsequent years. This trend is likely attributable to a combination of factors, including increased population immunity through vaccination and natural infection, advancements in clinical management strategies and evolution of the virus into variants with potentially lower pathogenicity [

23]. Mortality consistently increased with age, though crude death rates declined across most age groups except the youngest. Male mortality was approximately 60% higher than female mortality throughout the pandemic. A significant shift in the place of death occurred over time, with decline in deaths in medical facilities and a doubling of home deaths by 2024. This trend underscores the need for enhanced vigilance and strengthened home-based care for patients at higher risk of developing more aggressive forms of COVID-19.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.M. and G.L.; methodology, C.M.; formal analysis, G.L.; data curation, G.L.; writing—original draft preparation, C.M.; writing—review and editing, G.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The NCHS WONDER is a publicly available, anonymized and freely searchable database, so that the study was exempt from Ethical Committee approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article or supplementary material.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| COVID-19 |

Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| SARS-CoV-2 |

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 |

| NCHS |

National Center for Health Statistics |

| WONDER |

Wide-Ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research |

| ICD-10 |

International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision |

| ICU |

Intensive Care Unit |

| RSV |

Respiratory Syncytial Virus |

| CISA |

Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Security Agency |

References

- Mattiuzzi C, Lippi G. COVID-19: Lessons from the Past to Inform the Future of Healthcare. COVID 2025;5:4. [CrossRef]

- Hernandez JBR, Kim PY. Epidemiology Morbidity And Mortality. [Updated 2022 Oct 3]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK547668/.

- Khan JR, Awan N, Islam MM, Muurlink O. Healthcare Capacity, Health Expenditure, and Civil Society as Predictors of COVID-19 Case Fatalities: A Global Analysis. Front Public Health 2020;8:347. [CrossRef]

- Yang F, Tran TN, Howerton E, Boni MF, Servadio JL. Benefits of near-universal vaccination and treatment access to manage COVID-19 burden in the United States. BMC Med 2023;21:321. [CrossRef]

- Lippi G, Henry BM, Plebani M. A Simple Epidemiologic Model for Predicting Impaired Neutralization of New SARS-CoV-2 Variants. Vaccines (Basel) 2023;11:128. [CrossRef]

- Filip R, Gheorghita Puscaselu R, Anchidin-Norocel L, Dimian M, Savage WK. Global Challenges to Public Health Care Systems during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Review of Pandemic Measures and Problems. J Pers Med 2022;12:1295. [CrossRef]

- Cueni T. Lessons learned from COVID-19 to stop future pandemics. Lancet 2023;401:1340. [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Provisional Mortality on CDC WONDER Online Database. Data are from the final Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2022, and from provisional data for years 2023-2024, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program. Accessed at http://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd-icd10-provisional.html on Jan 13, 2025.

- ICD-10-CM Codes. 2025 ICD-10-CM Diagnosis Code U07.1. Available at: https://www.icd10data.com/ICD10CM/Codes/U00-U85/U00-U49/U07-/U07.1. Last accessed: January 13, 2025.

- Matthes KL, Staub K. The Need to Analyse Historical Mortality Data to Understand the Causes of Today's Health Inequalities. Int J Public Health 2024;69:1607739. [CrossRef]

- Franchi M, Pellegrini G, Cereda D, Bortolan F, Leoni O, Pavesi G, et al. Natural and vaccine-induced immunity are equivalent for the protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Infect Public Health 2023;16:1137-1141. [CrossRef]

- Tsagkli P, Geropeppa M, Papadatou I, Spoulou V. Hybrid Immunity against SARS-CoV-2 Variants: A Narrative Review of the Literature. Vaccines (Basel) 2024;12:1051. [CrossRef]

- Bhimraj A, Morgan RL, Shumaker AH, Baden LR, Cheng VC, Edwards KM, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines on the Treatment and Management of Patients With COVID-19 (September 2022). Clin Infect Dis 2024;78:e250-49. [CrossRef]

- Livieratos A, Gogos C, Akinosoglou K. SARS-CoV-2 Variants and Clinical Outcomes of Special Populations: A Scoping Review of the Literature. Viruses 2024;16:1222. [CrossRef]

- Bachmann M, Gültekin N, Stanga Z, Fehr JS, Ülgür II, Schlagenhauf P. Disparities in response to mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccines according to sex and age: A systematic review. New Microbes New Infect 2024;63:101551. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Soto MC, Ortega-Cáceres G, Arroyo-Hernández H. Sex differences in COVID-19 fatality rate and risk of death: An analysis in 73 countries, 2020-2021. Infez Med 2021;29:402-7. [CrossRef]

- Shahid Z, Kalayanamitra R, McClafferty B, Kepko D, Ramgobin D, Patel R, et al. COVID-19 and Older Adults: What We Know. J Am Geriatr Soc 2020;68:926-9. [CrossRef]

- Rossi AP, Gottin L, Donadello K, Schweiger V, Nocini R, Taiana M, et al. Obesity as a risk factor for unfavourable outcomes in critically ill patients affected by Covid 19. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2021;31:762-8. [CrossRef]

- Martin B, Rao S, Bennett TD. Disparities in Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children and COVID-19 Across the Organ Dysfunction Continuum. JAMA Netw Open 2023;6:e2249552. [CrossRef]

- Belza C, Pullenayegum E, Nelson KE, Aoyama K, Fu L, Buchanan F, et al. Severe Respiratory Disease Among Children With and Without Medical Complexity During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw Open 2023;6:e2343318. [CrossRef]

- French G, Hulse M, Nguyen D, Sobotka K, Webster K, Corman J, et al. Impact of Hospital Strain on Excess Deaths During the COVID-19 Pandemic - United States, July 2020-July 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021;70:1613-6. [CrossRef]

- Shen K, Loomer L, Abrams H, Grabowski DC, Gandhi A. Estimates of COVID-19 Cases and Deaths Among Nursing Home Residents Not Reported in Federal Data. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e2122885. [CrossRef]

- Lippi G, Nocini R, Henry BM. Analysis of online search trends suggests that SARS-CoV-2 Omicron (B.1.1.529) variant causes different symptoms. J Infect 2022;84:e76-7. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).