Submitted:

12 February 2025

Posted:

13 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Problem Formulation

Weak Form Derivation

Boundary Conditions

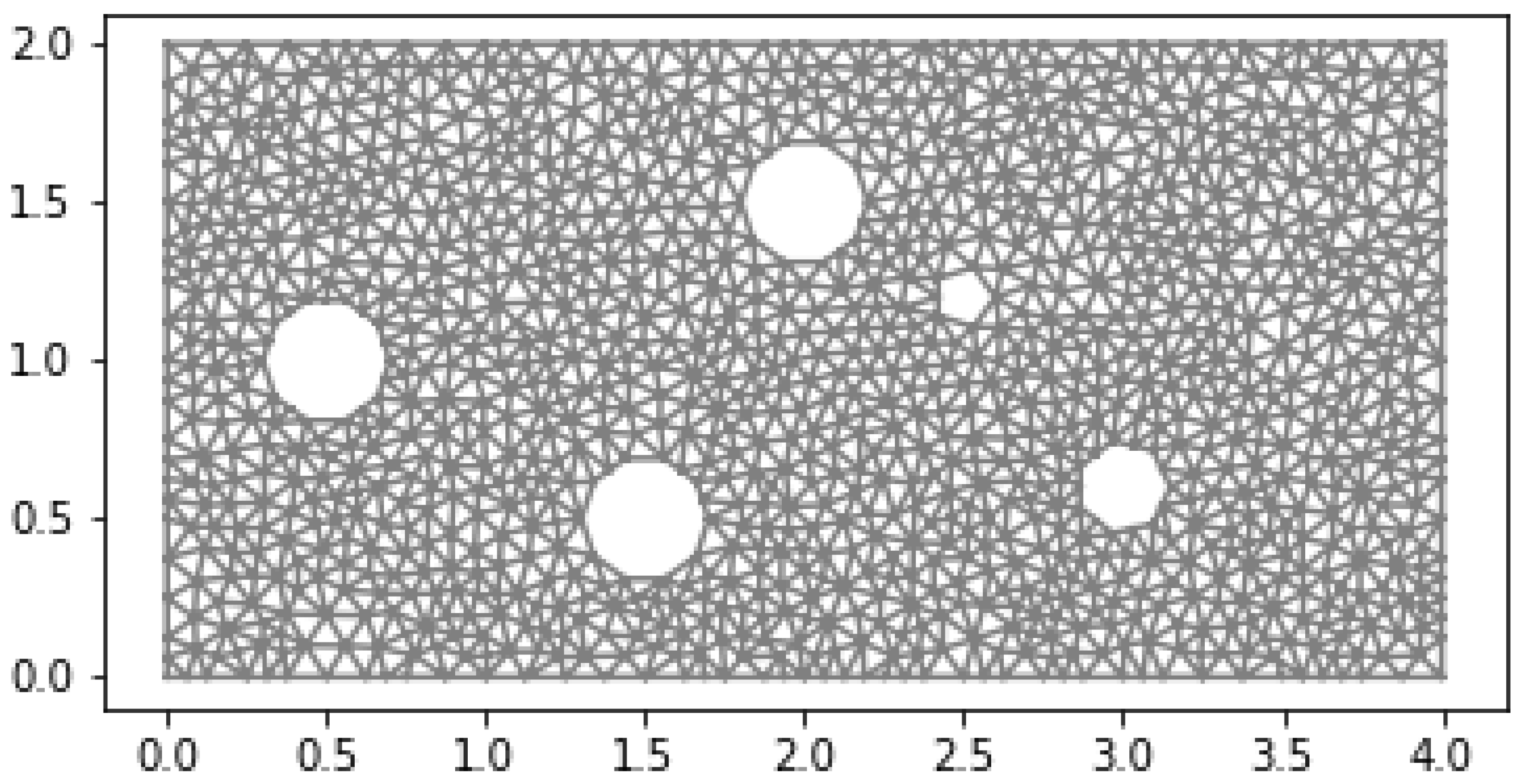

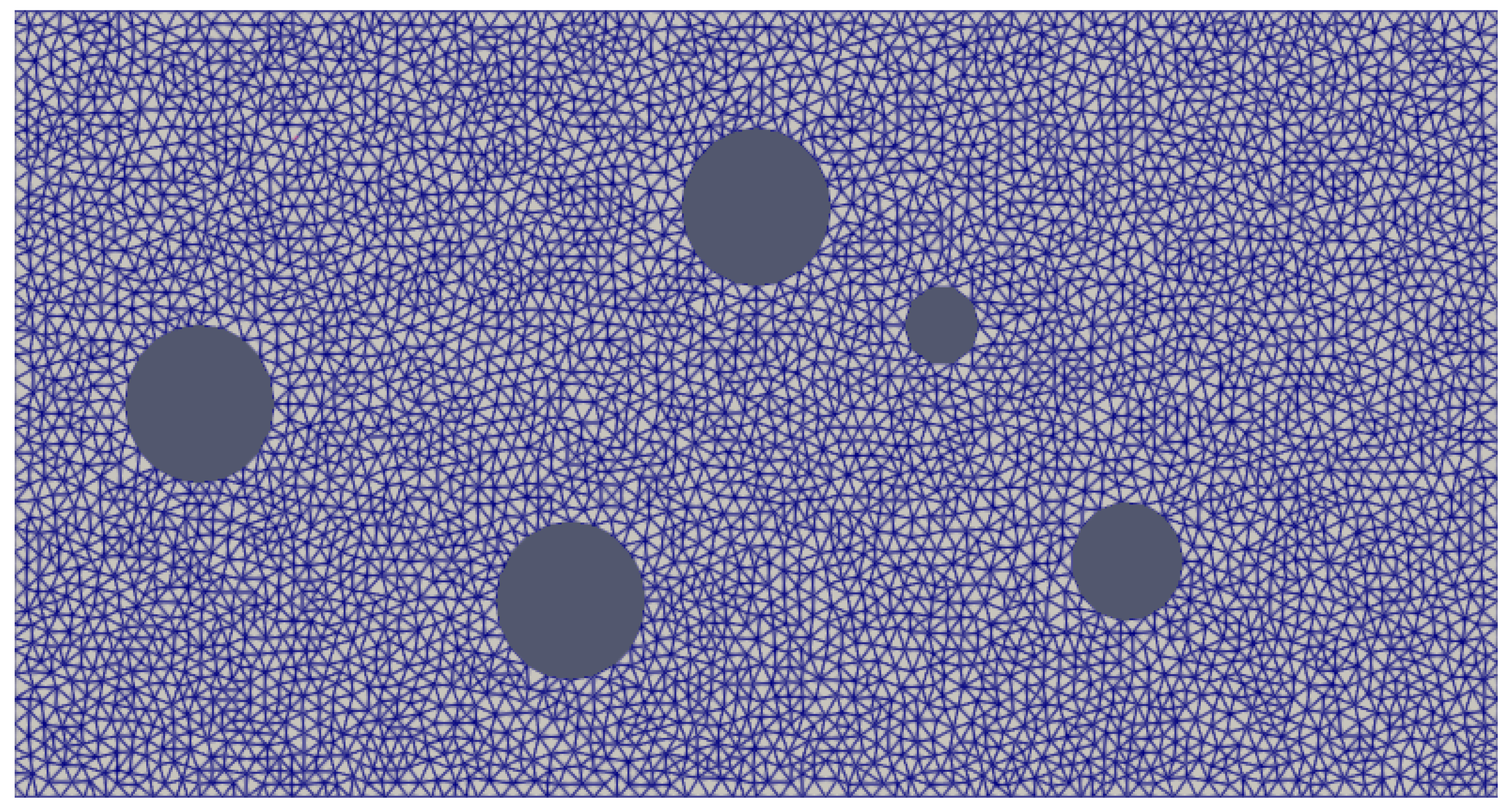

Finite Element Approximation

FEniCS Implementation

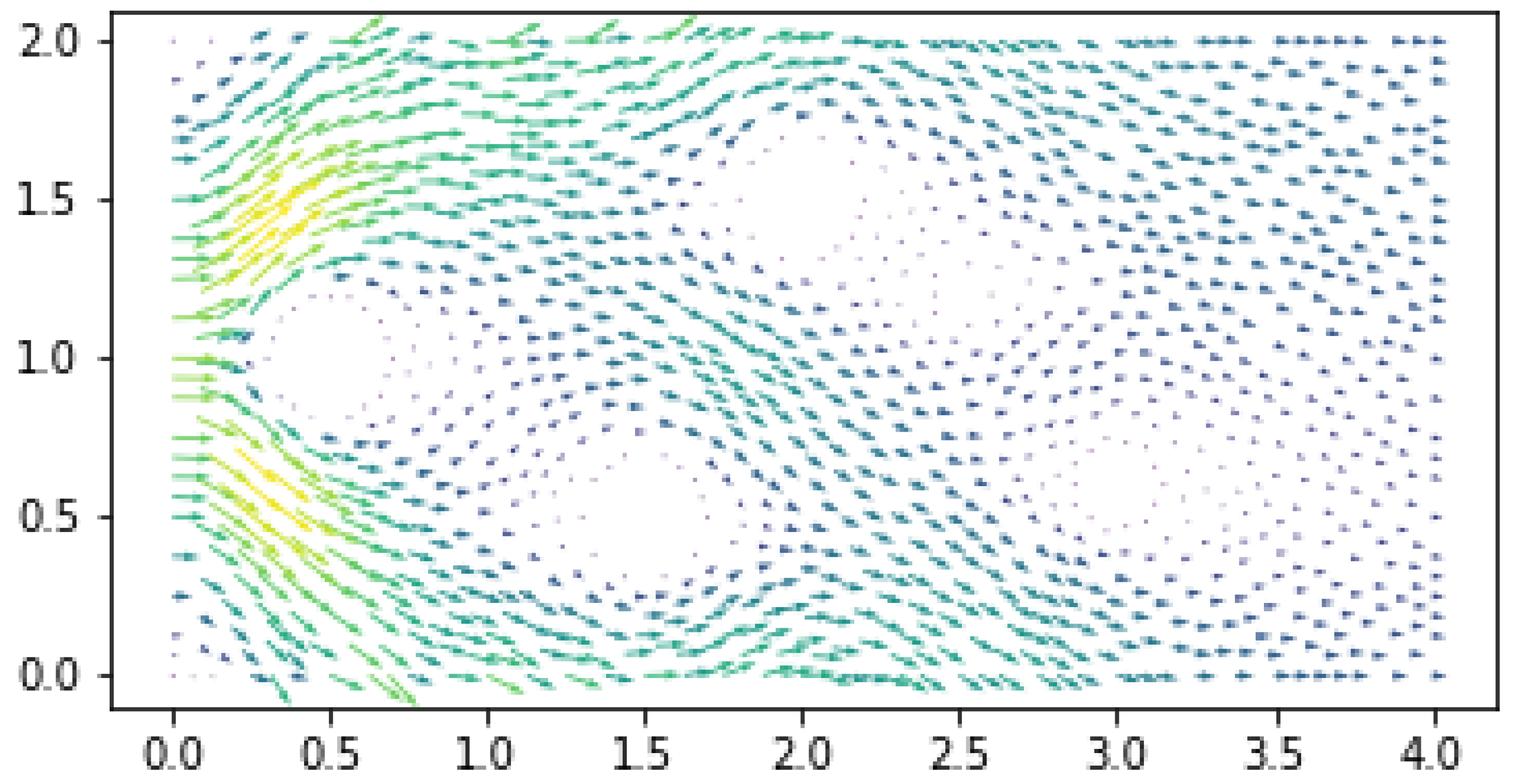

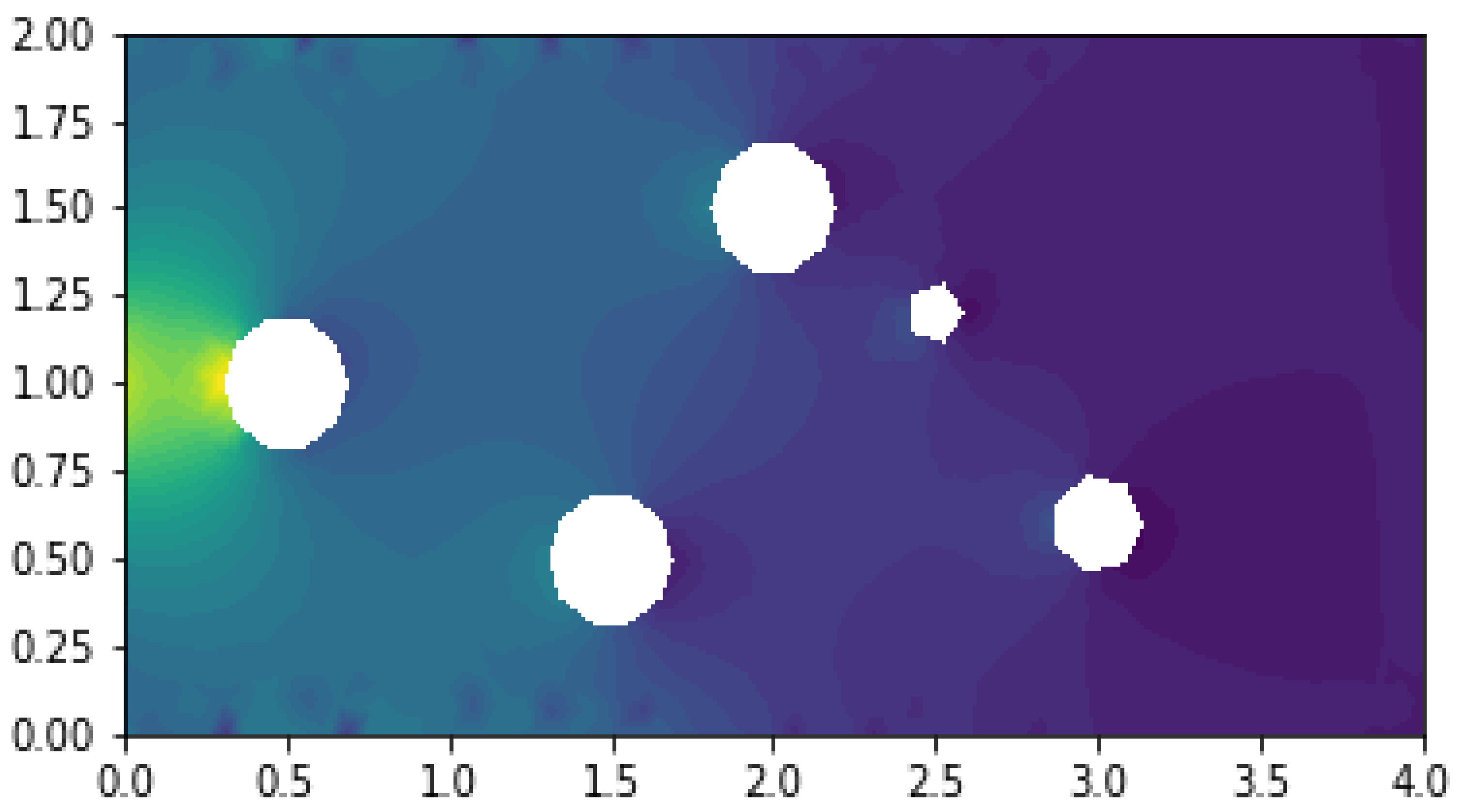

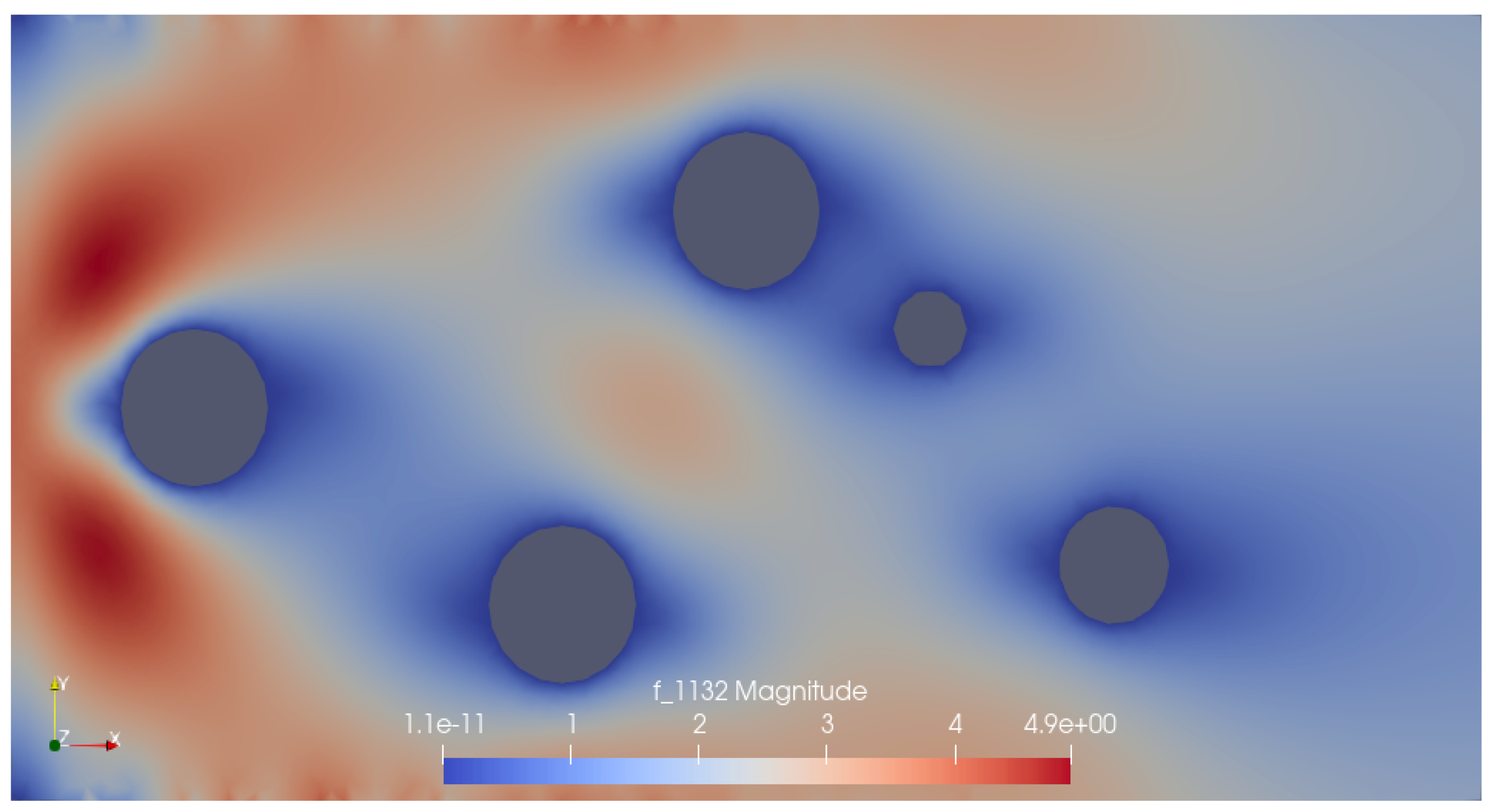

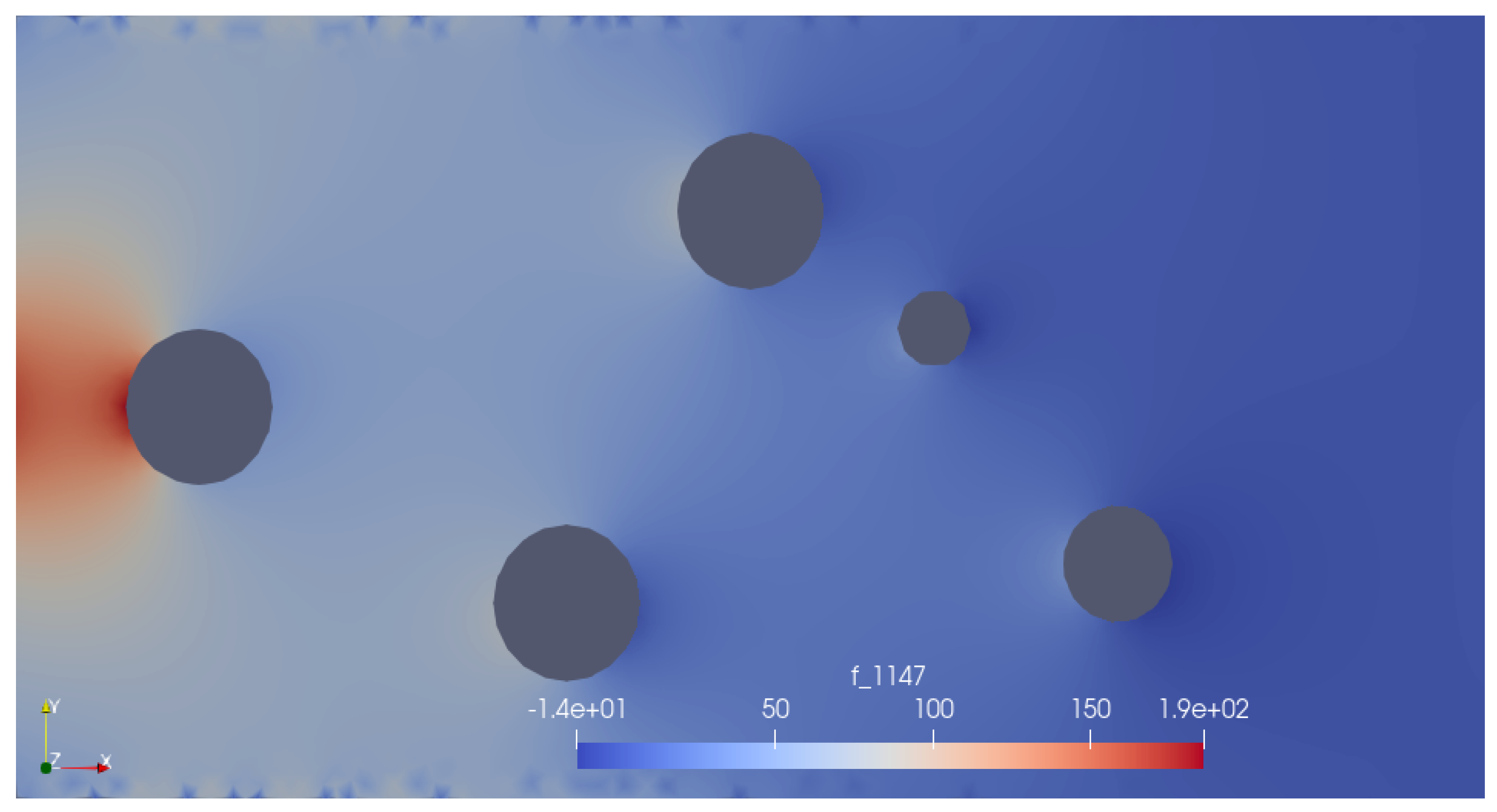

Results

Conclusions and Way Forward

References

- Djakbarova, U.; Madraki, Y.; Chan, E.; Kural, C. Dynamic interplay between cell membrane tension and clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Biol Cell 2021, 113, 344–73.

- Houk, A.; Jilkine, A.; Mejean, C.; Boltyanskiy, R.; Dufresne, E.; Angenent, SB, e.a. Membrane tension maintains cell polarity by confining signals to the leading edge during neutrophil migration. Cell 2012, 148, 175–88.

- Thottacherry, J.; Kosmalska, A.; Kumar, A.; Vishen, A.; Elosegui-Artola, A.; Pradhan, S, e.a. Mechanochemical feedback control of dynamin independent endocytosis modulates membrane tension in adherent cells. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 4217.

- Shi, Z.; Graber, Z.; Baumgart, T.; Stone, H.; Cohen, A. Cell membranes resist flow. Cell 2018, 175, 1769–79.e13.

- Kamalesh, K.; Scher, N.; Biton, T.; Schejter, E.; Shilo, E.Z.; Avinoam, O. Exocytosis by vesicle crumpling maintains apical membrane homeostasis during exocrine secretion. Dev Cell 2021, 56, 1603–1616.e6.

- Gauthier, N.; Fardin, M.; Roca-Cusachs, P.; Sheetz, M. Temporary increase in plasma membrane tension coordinates the activation of exocytosis and contraction during cell spreading. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011, 108, 14467–72.

- Boulant, S.; Kural, C.; Zeeh, J.; Ubelmann, F.; Kirchhausen, T. Actin dynamics counteract membrane tension during clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Nat Cell Biol 2011, 13, 1124–31.

- Basu, R.; Whitlock, B.; Husson, J.; Le Floc’h, A.; Jin, W.; Oyler-Yaniv, A, e.a. Cytotoxic T cells use mechanical force to potentiate target cell killing. Cell 2016, 165, 100–10.

- Diz-Muñoz, A.; Fletcher, D.; Weiner, O. Use the force: Membrane tension as an organizer of cell shape and motility. Trends Cell Biol 2013, 23, 47–53.

- Shi, Z.; Baumgart, T. Membrane tension and peripheral protein density mediate membrane shape transitions. Nat Commun 2015, 6, 5974.

- Bertoluzza, S.; Chabannes, V.; Prud’Homme, C.; Szopos, M. Boundary conditions involving pressure for the Stokes problem and applications in computational hemodynamics. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng 2017, 322, 58–80.

- SMubasshar. new-rep. GitHub repository 2025.

- Hruza. Fluid-Particle-ALE. GitHub repository 2025.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).