Submitted:

11 February 2025

Posted:

20 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

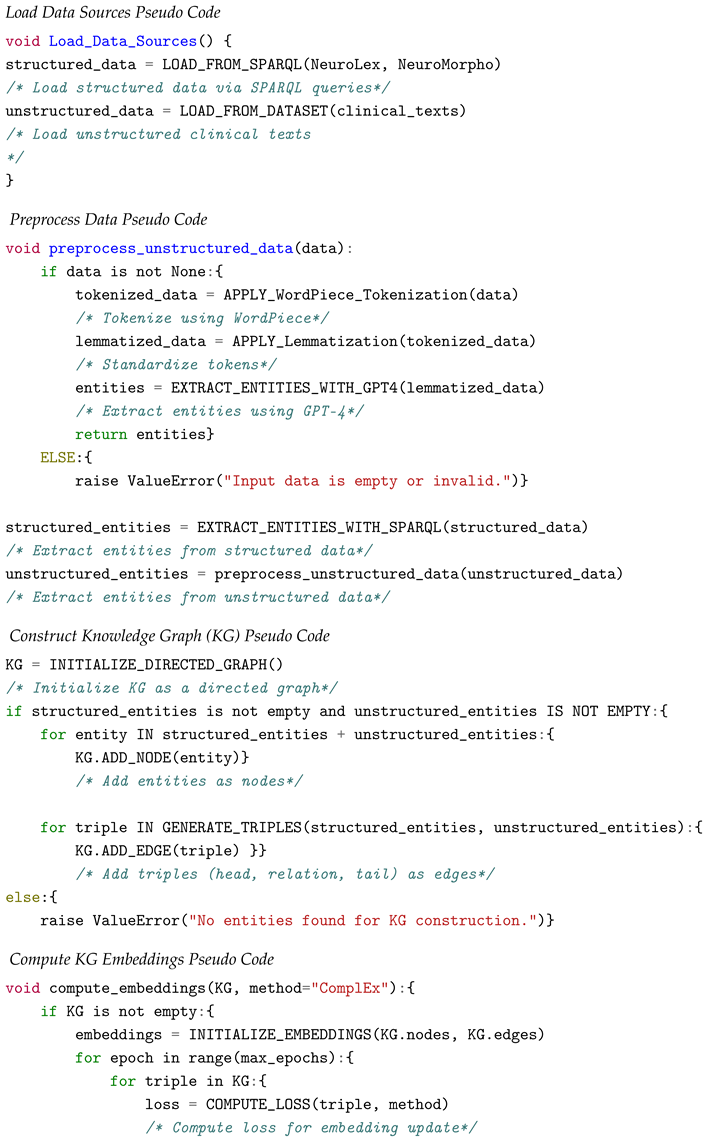

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Sources

- NeuroLex: NeuroLex is a comprehensive, structured ontology for cognitive neuroscience, offering hierarchical knowledge of brain regions, neuron types, and cognitive functions. Relevant entities (e.g., hippocampus, Anxiety, memory) are extracted using SPARQL queries, which retrieve data in the form of RDF triples (subject, predicate, object). These triples, such as the amygdala (associated with Anxiety), form the knowledge graph (KG) foundation, where nodes represent entities, and edges represent relationships between them. NeuroLex provides highly granular and standardized data, enabling PKG-LLM to systematically incorporate neurobiological structures and their cognitive associations.

- NeuroMorpho: NeuroMorpho offers a rich repository of 3D neuronal morphology data, providing detailed information about neuronal structures such as dendrites, axons, and soma size. Initially provided in SWC format, this morphological data is processed into a relational structure and integrated into the KG. Each neuron type is linked to its corresponding brain region and further connected to cognitive functions or psychiatric disorders, such as GAD and MDD. For example, a neuron from the prefrontal cortex (PFC) might be linked to mood regulation and associated with MDD. This neuroanatomical data enhances the KG by adding structural depth to the relationships between brain regions and mental disorders.

- Tokenization: Clinical text is split into meaningful tokens (words, phrases) to facilitate analysis.

- Lemmatization: Words are reduced to their base or dictionary form, allowing for standardization across clinical variations.

- Named Entity Recognition (NER): Leveraging the capabilities of GPT-4 for NER tasks, medical entities such as symptoms, diagnoses, and treatments are extracted with high accuracy. GPT-4 enables the precise identification of entities from clinical notes and text, facilitating their integration into the knowledge graph (KG). For example, the term "persistent worry" might be linked to the "Anxiety" node in the KG, while "sleep disturbance" could be associated with a node connected to sleep regulation and mental health. This process enhances the depth and relevance of the knowledge graph by ensuring that critical medical terms are accurately mapped.

3.2. Knowledge Graph Construction

3.2.1. Entity Extraction and Triple Formation

3.2.2. Graph Schema and KG Construction

3.2.3. Knowledge Graph Embeddings

-

TransE: In TransE, a relation r is modeled as a translation from the head entity h to the tail entity t. The energy function for a triple is defined as:Where are the embedding vectors of the head, relation, and tail, respectively, and denotes the L2-norm. The training objective is to minimize for correct triples and maximize it for incorrect triples (negative sampling).

-

TransH (Translation on Hyperplanes): TransH addresses the limitations of TransE by allowing each relation to have its hyperplane. Entities are first projected onto a relation-specific hyperplane, then the translation is performed. The projection of entity onto the hyperplane of relation is defined as:Where is the normal vector for relation r, and is the entity embedding projected onto the relation-specific hyperplane. The energy function is:Where are the head and tail entity embeddings after being projected onto the hyperplane of relation r.

- ComplEx: ComplEx extends TransE to model asymmetric relations by embedding entities and relations into complex-valued vector spaces. The scoring function for a triple is:where are complex vectors, is the complex conjugate of t, and denotes the trilinear dot product. This allows the model to capture non-symmetric relations common in cognitive neuroscience.

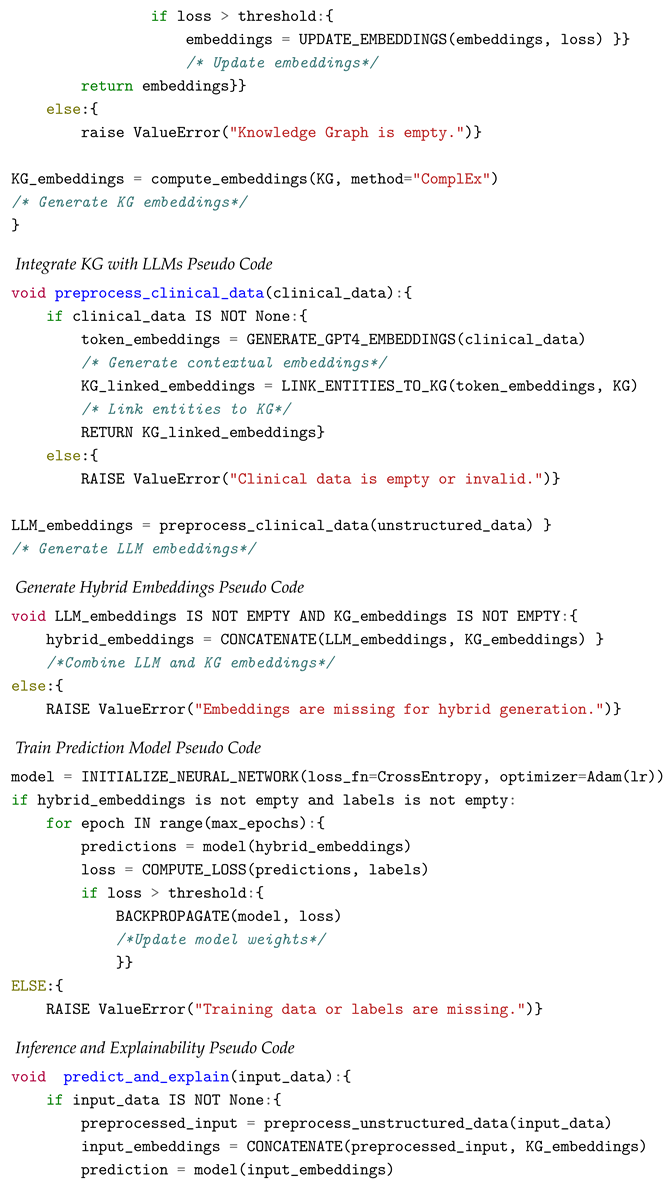

3.3. Integration with Large Language Models (LLMs)

3.3.1. Preprocessing of Clinical Data

- Tokenization: The text is tokenized using WordPiece tokenization (as employed in BERT) to effectively handle subword units and ensure that all terms, including medical terms, are accurately segmented.

- Entity Recognition and Linking: GPT-4 and models like ClinicalBERT are used for Named Entity Recognition (NER) to identify medical entities such as symptoms, diagnoses, and treatments. These entities are then linked to their corresponding nodes in the KG through entity-linking algorithms, ensuring semantic consistency across the knowledge graph.

3.3.2. LLM-Based Feature Extraction

3.3.3. KG-Augmented Embeddings

3.3.4. Attention Mechanism for Symptom and Entity Interaction

3.4. Model Training and Optimization

3.4.1. Neural Network Architecture

3.4.2. Loss Function and Optimization

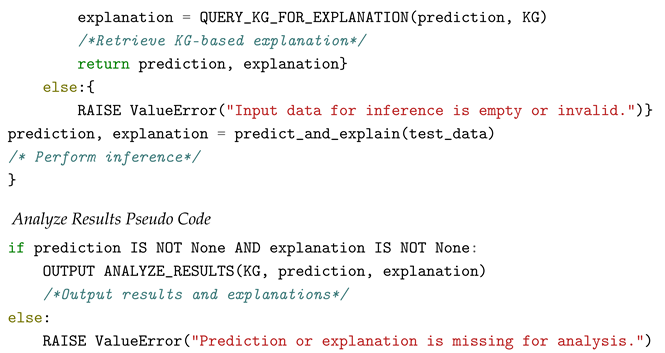

3.5. Inference and Explainability

3.5.1. Knowledge Graph Querying

3.5.2. Attention-Based Explanation

3.6. Result

- Discovery of Differences in the Structure of Hippocampal Neurons in GAD and MDD Patients: Using data from NeuroMorpho, our team has shown that pyramidal neurons in the hippocampus of MDD patients undergo more significant structural changes, such as a reduction in dendritic branching. In contrast, these neuronal changes in GAD patients occur differently, such as increased synaptic activity in stress-related regions. These differences may explain the cognitive and emotional symptoms variation between the two disorders.

- Identification of New Connections Between the Amygdala and Short-Term Memory in GAD and MDD Patients: Using data from NeuroLex, our team was able to uncover new associations between the amygdala and short-term memory, among other regions. The results showed that in patients with GAD, amygdala activity tends to reduce short-term memory more adversely, while the same in cases of MDD remains less intense. These insights also provide a more informed understanding of the cognitive distinction between the two disorders.

- Detection of Differences in Neuronal Plasticity in the Prefrontal Cortex Between the Two Disorders: Using data from NeuroMorpho, our team was able to uncover more detailed changes in dendritic branching and synapses in the prefrontal cortex of GAD and MDD patients. These findings explain why GAD patients tend to react more strongly to environmental stimuli, while MDD patients show less responsiveness to similar stimuli. This difference in neuronal plasticity could be the key factor behind the varied behavioral responses observed in these two disorders.

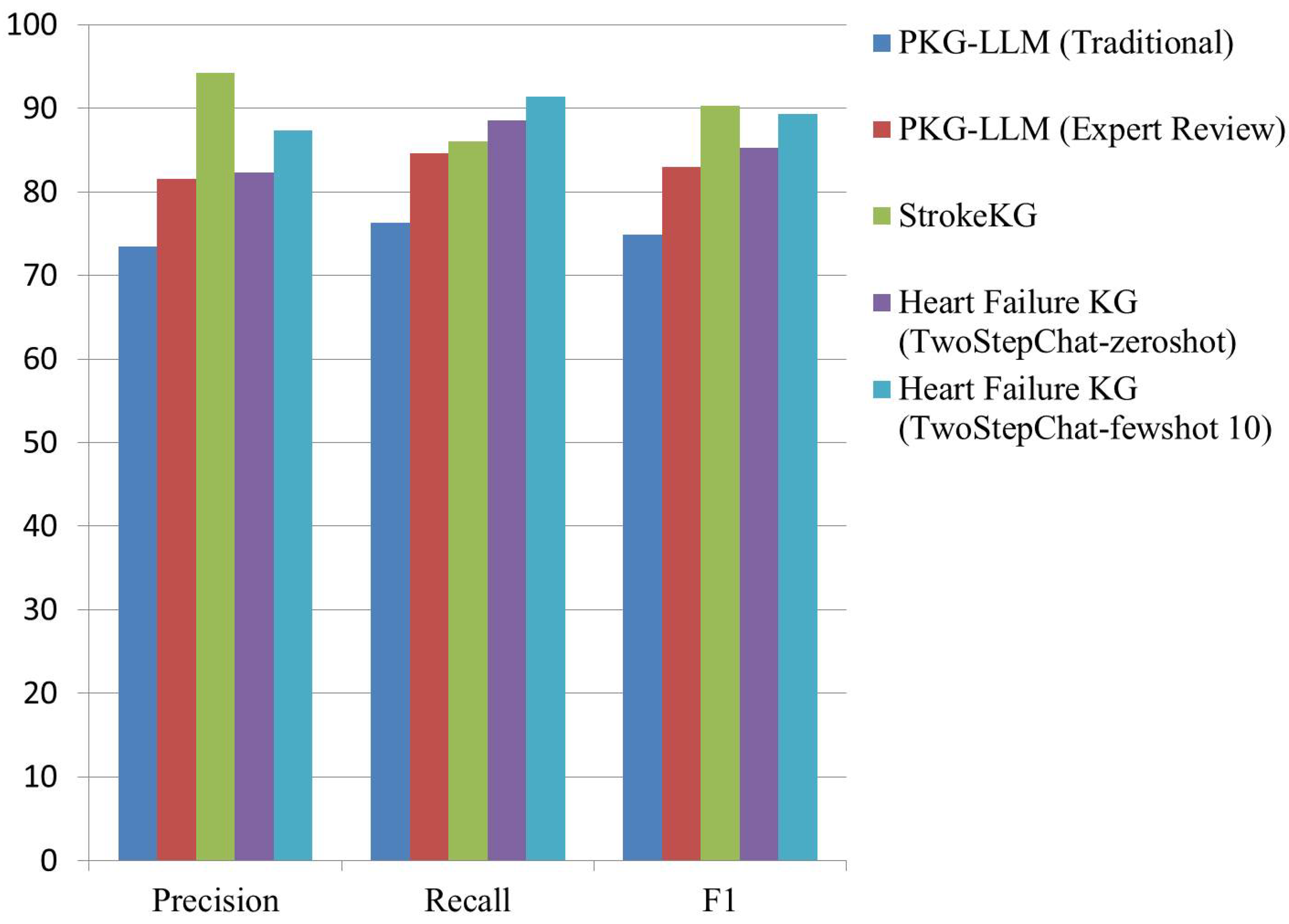

4. Evaluation

4.1. Traditional Metrics

- Precision: The ratio of correctly aligned nodes and edges (true positives) to all aligned nodes and edges (true positives + false positives).

- Recall: The ratio of correctly aligned nodes and edges to all actual correct nodes and edges in the original graph (true positives + false negatives).

- F1-Score: The harmonic mean of precision and recall, used to account for any imbalances between the two.

4.2. Expert Review

4.3. Link Prediction

-

Mean Rank (MR): Mean Rank is a metric used to evaluate the performance of information retrieval systems. This represents the average order of true positive items in the list of retrieved items. This is calculated by assigning a category to each item. Then find the average of the categories of related items. A lower average rank indicates better performance. This is because related items are rated higher on average [28].Where is the rank position of the i-th relevant item, and N is the total number of relevant items.

-

Mean Reciprocal Rank (MRR): Mean Reciprocal Rank is a metric that can be understood with a helpful example. Imagine you are searching for a specific document in a large database. MRR is the average of the reciprocal rows of the first related item in the list of retrieved items. This is useful in situations where the first relevant outcome has priority. MRR is a measure of how quickly the first relevant object is retrieved[29].Where is the rank position of the first relevant item for the i-th query, and N is the total number of queries.

- Precision in K (P@K): P@K measures the proportion of the top K items retrieved to their corresponding items. In our evaluation, we calculate P@K for different values of K, specifically K=1, K=3, and K=10. P@K measures the proportion of relevant items in the first k results, it evaluates the quality of the results. The highest ranking and calculated as follows[29]:where K is the number of top items considered, and N is the total number of queries.

5. Coagulation and Future Work

Appendix A

References

- Gurbuz, O.; Alanis-Lobato, G.; Picart-Armada, S.; Sun, M.; Haslinger, C.; Lawless, N.; Fernandez-Albert, F. Knowledge graphs for indication expansion: an explainable target-disease prediction method. Frontiers in genetics 2022, 13, 814093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholson, D.N.; Himmelstein, D.S.; Greene, C.S. Expanding a database-derived biomedical knowledge graph via multi-relation extraction from biomedical abstracts. BioData Mining 2022, 15, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Ebeid, I.A.; Bu, Y.; Ding, Y. Coronavirus knowledge graph: A case study. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2007.10287 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, K.M.; Krishnamurthy, M.; Alobaidi, M.; Hussain, M.; Alam, F.; Malik, G. Automated domain-specific healthcare knowledge graph curation framework: Subarachnoid hemorrhage as phenotype. Expert Systems with Applications 2020, 145, 113120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Seo, H.; Tabar, M.; Ma, F.; Wang, S.; Lee, D. Deterrent: Knowledge guided graph attention network for detecting healthcare misinformation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGKDD international conference on knowledge discovery & data mining, 2020, pp. 492–502.

- Xu, J.; Kim, S.; Song, M.; Jeong, M.; Kim, D.; Kang, J.; Rousseau, J.F.; Li, X.; Xu, W.; Torvik, V.I.; et al. Building a PubMed knowledge graph. Scientific data 2020, 7, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, R.; Ahmed, U.; Dobriy, D.; ajewska, W.; Menotti, L.; Saeedizade, M.J.; Dumontier, M. Exploring the role of generative AI in constructing knowledge graphs for drug indications with medical context. Proceedings http://ceur-ws. org ISSN 2023, 1613, 0073. [Google Scholar]

- Wawrzik, F.; Rafique, K.A.; Rahman, F.; Grimm, C. Ontology learning applications of knowledge base construction for microelectronic systems information. Information 2023, 14, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zeng, Y.; Das, A.; Jo, S.; Zhang, T.; Patel, P.; Zhang, J.; Gao, S.J.; Pratt, D.; Chiu, Y.C.; et al. reguloGPT: Harnessing GPT for Knowledge Graph Construction of Molecular Regulatory Pathways. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, W.; Lyu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Cai, J.; Shu, P.; Ge, Y.; Lu, Y.; Gao, S.; Wang, Y.; Wang, P.; et al. Large Language Models for Bioinformatics. arXiv arXiv:2501.06271 2025.

- Xu, R.; Shi, W.; Yu, Y.; Zhuang, Y.; Jin, B.; Wang, M.D.; Ho, J.C.; Yang, C. Ram-ehr: Retrieval augmentation meets clinical predictions on electronic health records. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.00815 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Li, R.; Croxford, E.; Tesch, S.; To, D.; Caskey, J.; Patterson, B.W.; Churpek, M.M.; Miller, T.; Dligach, D.; et al. Large Language Models and Medical Knowledge Grounding for Diagnosis Prediction. medRxiv 2023, 2023–11. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Ren, C.; Xie, S.; Liu, S.; Ji, H.; Wang, Z.; Sun, T.; He, L.; Li, Z.; Zhu, X.; et al. REALM: RAG-Driven Enhancement of Multimodal Electronic Health Records Analysis via Large Language Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.07016 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Yuanyuan, F.; Zhongmin, L. Research and application progress of Chinese medical knowledge graph. Journal of Frontiers of Computer Science & Technology 2022, 16, 2219. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, M.; Hegselmann, S.; Lang, H.; Kim, Y.; Sontag, D. Large language models are few-shot clinical information extractors. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2205.12689 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Frisoni, G.; Moro, G.; Balzani, L. Text-to-text extraction and verbalization of biomedical event graphs. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Computational Linguistics, 2022, pp. 2692–2710.

- Lee, J.; Yoon, W.; Kim, S.; Kim, D.; Kim, S.; So, C.H.; Kang, J. BioBERT: a pre-trained biomedical language representation model for biomedical text mining. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 1234–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandak, P.; Huang, K.; Zitnik, M. Building a knowledge graph to enable precision medicine. Scientific Data 2023, 10, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Li, Z.; Li, J.; Qu, Y.; Chang, Y.; Han, Q.; Cao, L.; Lin, S. Research on Traditional Chinese Medicine: Domain Knowledge Graph Completion and Quality Evaluation. JMIR Medical Informatics 2024, 12, e55090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Cao, X.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, F.; Gong, T.; Wang, Y.; Jing, S. AsdKB: A Chinese Knowledge Base for the Early Screening and Diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder. In Proceedings of the International Semantic Web Conference. Springer, 2023, pp. 59–75.

- Singhal, K.; Azizi, S.; Tu, T.; Mahdavi, S.S.; Wei, J.; Chung, H.W.; Scales, N.; Tanwani, A.; Cole-Lewis, H.; Pfohl, S.; et al. Large language models encode clinical knowledge. Nature 2023, 620, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.X.; Zhou, K.; Li, J.; Tang, T.; Wang, X.; Hou, Y.; Min, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, J.; Dong, Z.; et al. A survey of large language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.18223 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, T.; Gu, Y.; Xue, M.; Gu, R.; Li, B.; Gu, X. Knowledge graph construction for heart failure using large language models with prompt engineering. Frontiers in Computational Neuroscience 2024, 18, 1389475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viera, A.J.; Garrett, J.M.; et al. Understanding interobserver agreement: the kappa statistic. Fam med 2005, 37, 360–363. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kottner, J.; Streiner, D.L. The difference between reliability and agreement. Journal of clinical epidemiology 2011, 64, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McHugh, M.L. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochemia medica 2012, 22, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Wu, C.; Nenadic, G.; Wang, W.; Lu, K. Mining a stroke knowledge graph from literature. BMC bioinformatics 2021, 22, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayyeri, M.; Cil, G.M.; Vahdati, S.; Osborne, F.; Rahman, M.; Angioni, S.; Salatino, A.; Recupero, D.R.; Vassilyeva, N.; Motta, E.; et al. Trans4E: Link prediction on scholarly knowledge graphs. Neurocomputing 2021, 461, 530–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Wang, Y.C.; Wang, B.; Kuo, C.C.J.; et al. Knowledge Graph Embedding: An Overview. APSIPA Transactions on Signal and Information Processing 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordes, A.; Usunier, N.; Garcia-Duran, A.; Weston, J.; Yakhnenko, O. Translating embeddings for modeling multi-relational data. Advances in neural information processing systems 2013, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z.; Deng, Z.H.; Nie, J.Y.; Tang, J. Rotate: Knowledge graph embedding by relational rotation in complex space. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1902.10197 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, B.; Yih, W.t.; He, X.; Gao, J.; Deng, L. Embedding entities and relations for learning and inference in knowledge bases. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6575 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Trouillon, T.; Welbl, J.; Riedel, S.; Gaussier, É.; Bouchard, G. Complex embeddings for simple link prediction. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2016, pp. 2071–2080.

- Dettmers, T.; Minervini, P.; Stenetorp, P.; Riedel, S. Convolutional 2d knowledge graph embeddings. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, 2018, Vol. 32.

- Zheng, Z.; Zhou, B.; Yang, H.; Tan, Z.; Waaler, A.; Kharlamov, E.; Soylu, A. Low-Dimensional Hyperbolic Knowledge Graph Embedding for Better Extrapolation to Under-Represented Data. In Proceedings of the European Semantic Web Conference. Springer, 2024, pp. 100–120.

- Bollacker, K.; Evans, C.; Paritosh, P.; Sturge, T.; Taylor, J. Freebase: a collaboratively created graph database for structuring human knowledge. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2008 ACM SIGMOD international conference on Management of data, 2008, pp. 1247–1250.

- Miller, G.A. WordNet: a lexical database for English. Communications of the ACM 1995, 38, 39–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchanek, F.M.; Kasneci, G.; Weikum, G. Yago: a core of semantic knowledge. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 16th international conference on World Wide Web, 2007, pp. 697–706.

| Metric | Precision | Recall | F1 |

| PKG-LLM (Traditional) | 75.45 | 78.60 | 76.89 |

| PKG-LLM (Expert Review) | 82.34 | 85.40 | 83.85 |

| StrokeKG [27] | 80.06 | 88.92 | 84.26 |

| Metric | Precision | Recall | F1 |

| PKG-LLM (Traditional) | 73.42 | 76.30 | 74.84 |

| PKG-LLM (Expert Review) | 81.55 | 84.60 | 82.99 |

| StrokeKG | 94.21 | 86.04 | 90.26 |

| Heart Failure KG [23] (TwoStepChat-zeroshot) |

82.33 | 88.50 | 85.31 |

| Heart Failure KG (TwoStepChat-fewshot 10) |

87.35 | 91.35 | 89.31 |

| KG | Metrics | TransE [30] | RotatE [31] | DistMult [32] | ComplEx [33] | ConvE [34] | HolmE [35] |

| FB15k-237 [36] | MR | 209 | 178 | 199 | 144 | 281 | - |

| MRR | 0.310 | 0.336 | 0.313 | 0.367 | 0.305 | 0.331 | |

| P@1 | 0.217 | 0.238 | 0.224 | 0.271 | 0.219 | 0.237 | |

| P@3 | 0.257 | 0.328 | 0.263 | 0.275 | 0.350 | 0.366 | |

| P@10 | 0.496 | 0.530 | 0.490 | 0.558 | 0.476 | 0.517 | |

| WN18RR [37] | MR | 3936 | 3318 | 5913 | 2867 | 4944 | - |

| MRR | 0.206 | 0.475 | 0.433 | 0.489 | 0.427 | 0.466 | |

| P@1 | 0.279 | 0.426 | 0.396 | 0.442 | 0.389 | 0.415 | |

| P@3 | 0.364 | 0.492 | 0.440 | 0.460 | 0.430 | 0.489 | |

| P@10 | 0.495 | 0.573 | 0.502 | 0.580 | 0.507 | 0.561 | |

| YAGO3-10 [38] | MR | 1187 | 1830 | 1107 | 793 | 2429 | - |

| MRR | 0.501 | 0.498 | 0.501 | 0.577 | 0.488 | 0.441 | |

| P@1 | 0.405 | 0.405 | 0.412 | 0.500 | 0.399 | 0.333 | |

| P@3 | 0.528 | 0.550 | 0.38 | 0.40 | 0.560 | 0.507 | |

| P@10 | 0.673 | 0.670 | 0.661 | 0.7129 | 0.657 | 0.641 | |

| PKG-LLM | MR | 314 | 166 | 247 | 138 | 294 | - |

| MRR | 0.396 | 0.223 | 0.285 | 0.392 | 0.335 | 0.258 | |

| P@1 | 0.385 | 0.197 | 0.304 | 0.303 | 0.307 | 0.233 | |

| P@3 | 0.412 | 0.243 | 0.321 | 0.419 | 0.382 | 0.262 | |

| P@10 | 0.531 | 0.311 | 0.367 | 0.488 | 0.475 | 0.308 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).