Submitted:

11 February 2025

Posted:

12 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Reviewed Studies

2.2. Overview of Reviewed Studies

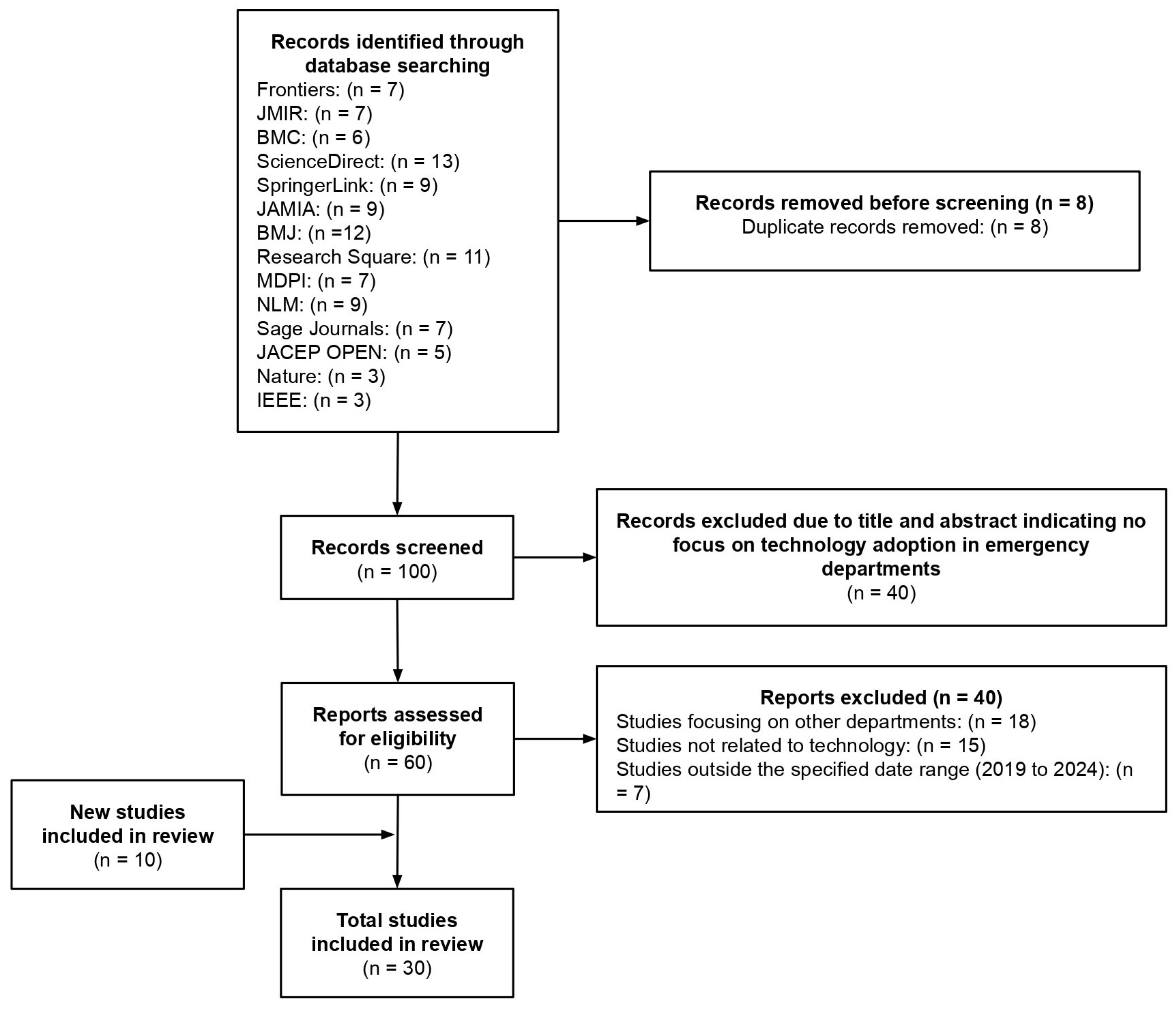

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Methodology

3.2. Meta-Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Literature Analysis

4.2. Comparative Analysis

4.3. Critical Analysis

4.4. Strategies for Technology Adoption

4.5. Innovation and Contribution

4.6. Limitation and Future Research

4.7. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EDs | Emergency Department |

| VUC | Virtual Urgent Care |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| CDSS | Clinical Decision Support System |

| OUD | Opioid Use Disorder |

| EHR | Electronic Health Records |

| HFE | Human Factors Engineering |

| PE | Pulmonary Embolism |

| DAs | Decision Aids |

| SDM | Shared Decision-Making |

| HIRAID® | History including Infection risk, Red flags, Assessment, Interventions, Diagnostics |

| PRISMA-ScR | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews |

| PEDs | Portable Electronic Devices |

| AWS | Amazon Web Services |

| VEDs | Virtual Emergency Departments |

| SOP | Standard Operating Procedure |

References

- R. Hendayani and M. Y. Febrianta, “Technology as a driver to achieve the performance of family businesses supply chain,” Journal of Family Business Management, vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 361–371, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. Pilevari and F. Yavari, “Journal of Industrial Strategic Management Industry Revolutions Development from Industry 1.0 to Industry 5.0 in Manufacturing,” Journal of Industrial Strategic Management, vol. 2020, no. 2, pp. 44–63, 2020.

- K. Yu, L. Lin, M. Alazab, L. Tan, and B. Gu, “Deep Learning-Based Traffic Safety Solution for a Mixture of Autonomous and Manual Vehicles in a 5G-Enabled Intelligent Transportation System,” IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, vol. 22, no. 7, pp. 4337–4347, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Hermes, T. Riasanow, E. K. Clemons, M. Böhm, and H. Krcmar, “The digital transformation of the healthcare industry: exploring the rise of emerging platform ecosystems and their influence on the role of patients,” Business Research, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 1033–1069, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Bohr and K. Memarzadeh, “The rise of artificial intelligence in healthcare applications,” in Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare, Elsevier, 2020, pp. 25–60. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Sujan, S. White, I. Habli, and N. Reynolds, “Stakeholder perceptions of the safety and assurance of artificial intelligence in healthcare,” Saf Sci, vol. 155, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- I. Kulkov, A. Tsvetkova, and M. Ivanova-Gongne, “Identifying institutional barriers when implementing new technologies in the healthcare industry,” European Journal of Innovation Management, vol. 26, no. 4, pp. 909–932, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Bruun, L. Milling, S. Mikkelsen, and L. Huniche, “Ethical challenges experienced by prehospital emergency personnel: a practice-based model of analysis,” BMC Med Ethics, vol. 23, no. 1, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. L. Hick and A. T. Pavia, “Duty to Plan: Health Care, Crisis Standards of Care, and Novel Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2,” National Library of Medicine, 2020. [CrossRef]

- O. J. Canfell et al., “Understanding the Digital Disruption of Health Care: An Ethnographic Study of Real-Time Multidisciplinary Clinical Behavior in a New Digital Hospital,” Appl Clin Inform, vol. 13, no. 5, pp. 1079–1091, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. Østervang, C. M. Jensen, E. Coyne, K. B. Dieperink, and A. Lassen, “Usability and Evaluation of a Health Information System in the Emergency Department: A Mixed Methods Study (Preprint),” JMIR Hum Factors, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. R. Anaraki et al., “A qualitative study of the barriers and facilitators impacting the implementation of a quality improvement program for emergency departments: SurgeCon.,” BMC Health Serv Res, vol. 24, no. 1, p. 855, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. H. Alshammari and A. Alenezi, “Nursing workforce competencies and job satisfaction: the role of technology integration, self-efficacy, social support, and prior experience,” BMC Nurs, vol. 22, no. 1, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Vainieri, C. Panero, and L. Coletta, “Waiting times in emergency departments: A resource allocation or an efficiency issue?,” BMC Health Serv Res, vol. 20, no. 1, Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. T. Stefánsdóttir et al., “Implementing a new emergency department: a qualitative study of health professionals’ change responses and perceptions,” BMC Health Serv Res, vol. 22, no. 1, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Cheraghi, H. Ebrahimi, N. Kheibar, and M. H. Sahebihagh, “Reasons for resistance to change in nursing: an integrative review,” BMC Nurs, vol. 22, no. 1, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. T. Chen, C. L. Lin, and W. N. Wu, “Big data management in healthcare: Adoption challenges and implications,” Int J Inf Manage, vol. 53, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. J. Kim, J. H. Choi, and G. M. N. Fotso, “Medical professionals’ adoption of AI-based medical devices: UTAUT model with trust mediation,” Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, vol. 10, no. 1, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. K. Mackey et al., “‘Fit-for-purpose?’ - Challenges and opportunities for applications of blockchain technology in the future of healthcare,” BMC Med, vol. 17, no. 1, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- E. Elder, A. N. B. Johnston, M. Wallis, and J. Crilly, “The demoralisation of nurses and medical doctors working in the emergency department: A qualitative descriptive study,” Int Emerg Nurs, vol. 52, p. 100841, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. N. Hall et al., “Designs, facilitators, barriers, and lessons learned during the implementation of emergency department led virtual urgent care programs in Ontario, Canada,” Front Digit Health, vol. 4, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Fujimori et al., “Acceptance, Barriers, and Facilitators to Implementing Artificial Intelligence–Based Decision Support Systems in Emergency Departments: Quantitative and Qualitative Evaluation,” JMIR Form Res, vol. 6, no. 6, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. S. Huilgol, C. T. Berdahl, N. Qureshi, C. C. Cohen, P. Mendel, and S. H. Fischer, “Innovation adoption, use and implementation in emergency departments during the COVID-19 pandemic,” BMJ Innov, p. bmjinnov-2023-001206, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. S. Zachrison, K. M. Boggs, E. M. Hayden, J. A. Espinola, and C. A. Camargo, “Understanding Barriers to Telemedicine Implementation in Rural Emergency Departments,” Ann Emerg Med, vol. 75, no. 3, pp. 392–399, Mar. 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. Boyle et al., “Hospital-Level Implementation Barriers, Facilitators, and Willingness to Use a New Regional Disaster Teleconsultation System: Cross-Sectional Survey Study,” JMIR Public Health Surveill, vol. 9, 2023. [CrossRef]

- D. Pu et al., “Virtual emergency care in Victoria: Stakeholder perspectives of strengths, weaknesses, and barriers and facilitators of service scale-up,” Australas Emerg Care, vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 102–108, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- E. Antor, J. Owusu-Marfo, and J. Kissi, “Usability evaluation of electronic health records at the trauma and emergency directorates at the Komfo Anokye teaching hospital in the Ashanti region of Ghana,” BMC Med Inform Decis Mak, vol. 24, no. 1, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Bhosekar, S. Mena, S. Mihandoust, A. Joseph, and K. C. Madathil, “An Exploratory Study to Evaluate the Technological Barriers and Facilitators for Pediatric Behavioral Healthcare in Emergency Departments,” in Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, SAGE Publications Inc., 2023, pp. 2560–2563. [CrossRef]

- K. Hodwitz et al., “Healthcare workers’ perspectives on a prescription phone program to meet the health equity needs of patients in the emergency department: a qualitative study,” Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Nataliansyah et al., “Managing innovation: a qualitative study on the implementation of telehealth services in rural emergency departments,” BMC Health Serv Res, vol. 22, no. 1, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- B. Kennedy et al., “Establishing enablers and barriers to implementing the HIRAID® emergency nursing framework in rural emergency departments,” Australas Emerg Care, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. J. Moy et al., “Understanding the perceived role of electronic health records and workflow fragmentation on clinician documentation burden in emergency departments,” Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, vol. 30, no. 5, pp. 797–808, May 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Uscher-Pines, J. Sousa, A. Mehrotra, L. H. Schwamm, and K. S. Zachrison, “Rising to the challenges of the pandemic: Telehealth innovations in U.S. emergency departments,” Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, vol. 28, no. 9, pp. 1910–1918, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. H. Wong et al., “Formative evaluation of an emergency department clinical decision support system for agitation symptoms: a study protocol,” BMJ Open, vol. 14, no. 2, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. J. Barton et al., “Academic Detailing as a Health Information Technology Implementation Method: Supporting the Design and Implementation of an Emergency Department–Based Clinical Decision Support Tool to Prevent Future Falls,” JMIR Hum Factors, vol. 11, no. 1, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. Billah, L. Gordon, E. M. Schoenfeld, B. P. Chang, E. P. Hess, and M. A. Probst, “Clinicians’ perspectives on the implementation of patient decision aids in the emergency department: A qualitative interview study,” JACEP Open, vol. 3, no. 1, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. Davison et al., “Barriers and facilitators to implementing psychosocial digital health interventions for older adults presenting to emergency departments: a scoping review protocol,” BMJ Open, vol. 14, no. 8, p. e085304, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. E. Salwei, P. Carayon, D. Wiegmann, M. S. Pulia, B. W. Patterson, and P. L. T. Hoonakker, “Usability barriers and facilitators of a human factors engineering-based clinical decision support technology for diagnosing pulmonary embolism,” Int J Med Inform, vol. 158, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Simpson et al., “Implementation strategies to address the determinants of adoption, implementation, and maintenance of a clinical decision support tool for emergency department buprenorphine initiation: a qualitative study,” Implement Sci Commun, vol. 4, no. 1, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. D. Shin et al., “Barriers and Facilitators to Using an App-Based Tool for Suicide Safety Planning in a Psychiatric Emergency Department: A Qualitative Descriptive Study Using the Theoretical Domains Framework and COM-B Model,” 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Shuldiner, D. Srinivasan, L. Desveaux, and J. N. Hall, “The Implementation of a Virtual Emergency Department: Multimethods Study Guided by the RE-AIM (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance) Framework,” JMIR Form Res, vol. 7, no. 1, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Sharifi Kia, M. Rafizadeh, and L. Shahmoradi, “Telemedicine in the emergency department: an overview of systematic reviews,” Aug. 01, 2023, Institute for Ionics. [CrossRef]

- B. Z. Hose et al., “Work system barriers and facilitators of a team health information technology,” Appl Ergon, vol. 113, p. 104105, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Tyler et al., “Use of Artificial Intelligence in Triage in Hospital Emergency Departments: A Scoping Review,” Cureus, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Hudson et al., “Perspectives of Healthcare Providers to Inform the Design of an AI-Enhanced Social Robot in the Pediatric Emergency Department,” Children, vol. 10, no. 9, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. D. Katzman, C. B. van der Pol, P. Soyer, and M. N. Patlas, “Artificial intelligence in emergency radiology: A review of applications and possibilities,” Jan. 01, 2023, Elsevier Masson s.r.l. [CrossRef]

- K. Piliuk and S. Tomforde, “Artificial intelligence in emergency medicine. A systematic literature review,” Int J Med Inform, vol. 180, p. 105274, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Jordan, J. Hauser, S. Cota, H. Li, and L. Wolf, “The Impact of Cultural Embeddedness on the Implementation of an Artificial Intelligence Program at Triage: A Qualitative Study,” Journal of Transcultural Nursing, vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 32–39, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Talevski et al., “From concept to reality: A comprehensive exploration into the development and evolution of a virtual emergency department,” JACEP Open, vol. 5, no. 4, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. M. Arabi, A. A. Al Ghamdi, M. Al-Moamary, A. Al Mutrafy, R. H. AlHazme, and B. A. Al Knawy, “Electronic medical record implementation in a large healthcare system from a leadership perspective,” BMC Med Inform Decis Mak, vol. 22, no. 1, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. B. D. Laig and F. T. Abocejo, “Change Management Process in a Mining Company: Kotter’s 8-Step Change Model,” Journal of Management, Economics, and Industrial Organization, pp. 31–50, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- F. A. Memon, S. Shah, and U. Khoso, “IMPROVING EMPLOYEE’S ENGAGEMENT IN CHANGE: REASSESSING KURT LEWIN’S MODEL,” 2021. [Online]. Available: http://cusitjournals.com/index.php/CURJ.

- M. A. Kilby, “Creating Good Jobs in Automotive Manufacturing,” 2021.

- G. K. Gouda and B. Tiwari, “Talent agility, innovation adoption and sustainable business performance: empirical evidences from Indian automobile industry,” International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, vol. 71, no. 6, pp. 2582–2604, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Uday Krishna Padyana, Hitesh Premshankar Rai, Pavan Ogeti, Narendra Sharad Fadnavis, and Gireesh Bhaulal Patil, “Server less Architectures in Cloud Computing: Evaluating Benefits and Drawbacks,” Innovative Research Thoughts, vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 1–12, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- O. Ghandour, S. El Kafhali, and M. Hanini, “Computing Resources Scalability Performance Analysis in Cloud Computing Data Center,” J Grid Comput, vol. 21, no. 4, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. Ullagaddi, “From Barista to Bytes: How Starbucks Brewed a Digital Revolution,” Journal of Economics, Management and Trade, vol. 30, no. 9, pp. 78–89, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- F. Mızrak, “Effective Change Management Strategies,” in Perspectives on Artificial Intelligence in Times of Turbulence: Theoretical Background to Applications, IGI Global, 2023, pp. 135–162. [CrossRef]

- B. Moesl et al., “Towards a More Socially Sustainable Advanced Pilot Training by Integrating Wearable Augmented Reality Devices,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 14, no. 4, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

| Author | Topic | Participants | Sample Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hall et al. (2022) [21] | Designs, facilitators, barriers, and lessons learned during the implementation of emergency department led virtual urgent care programs in Ontario, Canada | 13 emergency medicine physicians and researchers with experience in leading and implementing local VUC programs | 7 out of 14 VUC pilot programs across Ontario |

| Fujimori et al. (2022) [22] | Acceptance, Barriers, and Facilitators to Implementing Artificial Intelligence–Based Decision Support Systems in Emergency Departments: Quantitative and Qualitative Evaluation | 14 physicians from two community, tertiary care hospitals in Japan | Data from 27,550 emergency department patients from a tertiary care hospital in Japan |

| |||

| Anaraki et al. (2024) [12] | A qualitative study of the barriers and facilitators impacting the implementation of a quality improvement program for emergency departments: SurgeCon | Physicians, nurses, managers, patient care facilitators, program coordinators and patients | 31 clinicians and 341 patients were surveyed via telephone |

| Huilgol et al. (2024) [23] | Innovation adoption, use and implementation in emergency departments during the COVID-19 pandemic | Healthcare professionals from 8 hospital-based emergency departments in the United States | 49 healthcare professionals |

| |||

| Zachrison et al. (2020) [24] | Understanding Barriers to Telemedicine Implementation in Rural Emergency Departments | Rural Emergency Departments (EDs) in the United States |

|

| Boyle et al. (2023) [25] | Hospital-Level Implementation Barriers, Facilitators, and Willingness to Use a New Regional Disaster Teleconsultation System: Cross-Sectional Survey Study | Emergency managers from hospital-based and freestanding emergency departments (EDs) in New England states | 189 hospitals and EDs were identified, with 164 (87%) responding to the survey |

| Pu et al. (2024) [26] | Virtual emergency care in Victoria: Stakeholder perspectives of strengths, weaknesses, and barriers and facilitators of service scale-up | Emergency medicine physicians, health care consumers, other health care professionals, including residential aged care facility staff members and general practitioners | 20 participants:

|

| Antor et al. (2024) [27] | Usability evaluation of electronic health records at the trauma and emergency directorates at the Komfo Anokye teaching hospital in the Ashanti region of Ghana | Trauma and emergency department staff members at Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital. | 234 trauma and emergency department staff members at Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital |

| Bhosekar et al. (2023) [28] | An Exploratory Study to Evaluate the Technological Barriers and Facilitators for Pediatric Behavioral Healthcare in Emergency Departments | Assistant nurse manager, charge nurse, security accounts manager, and patient safety specialist | 4 healthcare providers across two hospitals |

| Hodwitz et al. (2024) [29] | Healthcare workers’ perspectives on a prescription phone program to meet the health equity needs of patients in the emergency department: a qualitative study | Healthcare workers | 12 interviews |

| Nataliansyah et al. (2022) [30] | Managing innovation: a qualitative study on the implementation of telehealth services in rural emergency departments | 18 key informants from six U.S. healthcare systems (hub sites) | 65 rural emergency departments (spoke sites) across 11 U.S. states |

| Kennedy et al. (2024) [31] | Establishing enablers and barriers to implementing the HIRAID® emergency nursing framework in rural emergency departments | Emergency nurses from 11 rural, regional emergency departments in Southern New South Wales, Australia | 102 nurses completed the survey |

| Moy et al. (2023) [32] | Understanding the perceived role of electronic health records and workflow fragmentation on clinician documentation burden in emergency departments | Physicians and registered nurses | 24 responses:

|

| Uscher-Pines et al. (2021) [33] | Rising to the challenges of the pandemic: Telehealth innovations in U.S. emergency departments | 15 emergency department leaders from 14 institutions across 10 states in the United States | A total of 35 individuals were invited to participate, resulting in a response rate of 43% |

| Wong et al. (2024) [34] | Formative evaluation of an emergency department clinical decision support system for agitation symptoms: a study protocol | Emergency department physicians, nurses, technicians, and patients with lived experience of restraint use during an emergency department visit |

|

| Barton et al. (2024) [35] | Academic Detailing as a Health Information Technology Implementation Method: Supporting the Design and Implementation of an Emergency Department–Based Clinical Decision Support Tool to Prevent Future Falls | Emergency medicine resident physicians and advanced practice providers | 16 participants (10 resident physicians and 6 advanced practice providers) |

| Billah et al. (2022) [36] | Clinicians' perspectives on the implementation of patient decision aids in the emergency department: A qualitative interview study | Emergency clinicians, including attending physicians, resident physicians, and physician assistants | 20 emergency clinicians |

| Davison et al. (2024) [37] | Barriers and facilitators to implementing psychosocial digital health interventions for older adults presenting to emergency departments: a scoping review protocol | The scoping review will consider articles that include older adults (70 years and older) who have received care in an emergency department setting, as well as other stakeholders such as patient families, clinical staff, and other hospital staff involved in the care of older adults in EDs | The review will include both qualitative and quantitative studies, but the exact sample size will depend on the studies identified and included in the review |

| Salwei et al. (2022) [38] | Usability barriers and facilitators of a human factors engineering-based clinical decision support technology for diagnosing pulmonary embolism | Emergency medicine physicians | 32 emergency medicine physicians:

|

| Simpson et al. (2023) [39] | Implementation strategies to address the determinants of adoption, implementation, and maintenance of a clinical decision support tool for emergency department buprenorphine initiation: a qualitative study | Clinicians from five different healthcare systems, including:

|

28 interviews |

| Shin et al. (2024) [40] | Barriers and Facilitators to Using an App-Based Tool for Suicide Safety Planning in a Psychiatric Emergency Department: A Qualitative Descriptive Study Using the Theoretical Domains Framework and COM-B Model | Nurses, psychiatrists, social workers, program assistants, and chemists | 29 emergency department professionals |

| Shuldiner et al. (2023) [41] | The Implementation of a Virtual Emergency Department: Multimethods Study Guided by the RE-AIM (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance) Framework | Patients utilizing the virtual emergency department (VED) and medical specialists | Average of 153 visits per month |

| Sharifi Kia et al. (2023) [42] | Telemedicine in the emergency department: an overview of systematic reviews | Review-based study | Analysis of 18 studies (not direct participant data) |

| Hose et al. (2023) [43] | Work system barriers and facilitators of a team health information technology | Professionals from 12 different healthcare disciplines | 36 healthcare workers |

| Tyler et al. (2024) [44] | Use of Artificial Intelligence in Triage in Hospital Emergency Departments: A Scoping Review | Review-based study | 29 publications selected from an initial 1142 reviewed |

| Hudson et al. (2023) [45] | Perspectives of Healthcare Providers to Inform the Design of an AI-Enhanced Social Robot in the Pediatric Emergency Department | Medical professionals from 2 paediatric emergency departments in Canada | 11 medical professionals |

| Katzman et al. (2023) [46] | Artificial intelligence in emergency radiology: A review of applications and possibilities | Review-based study | 44 studies reviewed |

| Piliuk and Tomforde (2023) [47] | Artificial intelligence in emergency medicine. A systematic literature review | Review-based study | 116 studies reviewed |

| Jordan et al. (2023) [48] | The Impact of Cultural Embeddedness on the Implementation of an Artificial Intelligence Program at Triage: A Qualitative Study | Triage nurses in a community hospital’s emergency department in the United States | 13 triage nurses |

| Talevski et al. (2024) [49] | From concept to reality: A comprehensive exploration into the development and evolution of a virtual emergency department | Patients using the Victorian Virtual Emergency Department in Victoria, Australia | 500 patients who used the VVED service |

| Author | Topic | Barriers | Facilitators |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hall et al. (2022) [21] | Designs, facilitators, barriers, and lessons learned during the implementation of emergency department led virtual urgent care programs in Ontario, Canada |

|

|

| Fujimori et al. (2022) [22] | Acceptance, Barriers, and Facilitators to Implementing Artificial Intelligence–Based Decision Support Systems in Emergency Departments: Quantitative and Qualitative Evaluation |

|

|

| Anaraki et al. (2024) [12] | A qualitative study of the barriers and facilitators impacting the implementation of a quality improvement program for emergency departments: SurgeCon |

|

|

| Huilgol et al. (2024) [23] | Innovation adoption, use and implementation in emergency departments during the COVID-19 pandemic |

|

|

| Zachrison et al. (2020) [24] | Understanding Barriers to Telemedicine Implementation in Rural Emergency Departments |

|

|

| Boyle et al. (2023) [25] | Hospital-Level Implementation Barriers, Facilitators, and Willingness to Use a New Regional Disaster Teleconsultation System: Cross-Sectional Survey Study |

|

|

| Pu et al. (2024) [26] | Virtual emergency care in Victoria: Stakeholder perspectives of strengths, weaknesses, and barriers and facilitators of service scale-up |

|

|

| Antor et al. (2024) [27] | Usability evaluation of electronic health records at the trauma and emergency directorates at the Komfo Anokye teaching hospital in the Ashanti region of Ghana |

|

|

| Bhosekar et al. (2023) [28] | An Exploratory Study to Evaluate the Technological Barriers and Facilitators for Pediatric Behavioral Healthcare in Emergency Departments |

|

|

| Hodwitz et al. (2024) [29] | Healthcare workers’ perspectives on a prescription phone program to meet the health equity needs of patients in the emergency department: a qualitative study |

|

|

| Nataliansyah et al. (2022) [30] | Managing innovation: a qualitative study on the implementation of telehealth services in rural emergency departments |

|

|

| Kennedy et al. (2024) [31] | Establishing enablers and barriers to implementing the HIRAID® emergency nursing framework in rural emergency departments |

|

|

| Moy et al. (2023) [32] | Understanding the perceived role of electronic health records and workflow fragmentation on clinician documentation burden in emergency departments |

|

|

| Uscher-Pines et al. (2021) [33] | Rising to the challenges of the pandemic: Telehealth innovations in U.S. emergency departments |

|

|

| Wong et al. (2024) [34] | Formative evaluation of an emergency department clinical decision support system for agitation symptoms: a study protocol |

|

|

| Barton et al. (2024) [35] | Academic Detailing as a Health Information Technology Implementation Method: Supporting the Design and Implementation of an Emergency Department–Based Clinical Decision Support Tool to Prevent Future Falls |

|

|

| Billah et al. (2022) [36] | Clinicians' perspectives on the implementation of patient decision aids in the emergency department: A qualitative interview study |

|

|

| Davison et al. (2024) [37] | Barriers and facilitators to implementing psychosocial digital health interventions for older adults presenting to emergency departments: a scoping review protocol |

|

|

| Salwei et al. (2022) [38] | Usability barriers and facilitators of a human factors engineering-based clinical decision support technology for diagnosing pulmonary embolism |

|

|

| Simpson et al. (2023) [39] | Implementation strategies to address the determinants of adoption, implementation, and maintenance of a clinical decision support tool for emergency department buprenorphine initiation: a qualitative study |

|

|

| Shin et al. (2024) [40] | Barriers and Facilitators to Using an App-Based Tool for Suicide Safety Planning in a Psychiatric Emergency Department: A Qualitative Descriptive Study Using the Theoretical Domains Framework and COM-B Model |

|

|

| Shuldiner et al. (2023) [41] | The Implementation of a Virtual Emergency Department: Multimethods Study Guided by the RE-AIM (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance) Framework |

|

|

| Sharifi Kia et al. (2023) [42] | Telemedicine in the emergency department: an overview of systematic reviews |

|

- |

| Hose et al. (2023) [43] | Work system barriers and facilitators of a team health information technology |

|

|

| Tyler et al. (2024) [44] | Use of Artificial Intelligence in Triage in Hospital Emergency Departments: A Scoping Review |

|

- |

| Hudson et al. (2023) [45] | Perspectives of Healthcare Providers to Inform the Design of an AI-Enhanced Social Robot in the Pediatric Emergency Department |

|

|

| Katzman et al. (2023) [46] | Artificial intelligence in emergency radiology: A review of applications and possibilities |

|

|

| Piliuk and Tomforde (2023) [47] | Artificial intelligence in emergency medicine. A systematic literature review |

|

- |

| Jordan et al. (2023) [48] | The Impact of Cultural Embeddedness on the Implementation of an Artificial Intelligence Program at Triage: A Qualitative Study |

|

|

| Talevski et al. (2024) [49] | From concept to reality: A comprehensive exploration into the development and evolution of a virtual emergency department |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).