1. Introduction

Federated learning (FL) is a novel approach to securing machine learning (ML) by distributing workloads across multiple machines in a specific domain, allowing clients to train ML models collaboratively without exposing raw data [

1]. Within the realm of SG infrastructure, the concept of FL is still novel where the application has not been fully realized yet, including concerns around efficiency gains and security measures [

2]. At present, there is wide industry adoption of IoT devices such as smart meters which automate the meter reading process for electricity providers through internet communication [

2]. This data is then used to extrapolate power consumption patterns and predictions for individual homes and commercial buildings to satisfy power grid requirements on a city-wide scale. As more manual processes continue to be digitized within this domain and the use of data to make informed decisions through data-driven decision-making increase in the modern day, processes that concern the processing and utilization of this data must adapt in the same way [

2]. However, there is still concern with regards to the security of power consumption data that introduces potential implications relating to user privacy [

2]. An example being able to determine individual lifestyles and habits through power consumption data provided by a smart meter attached to a house. To build on the privacy-preservation feature that FL offers, we introduce HE, a novel encryption scheme that behaves similarly to other encryption schemes, incorporating a key generation function, an encryption function, a decryption function, and an evaluation function as one of the core components to the FL framework [

3]. The novelty in HE is that it allows the data to be manipulated while in an encrypted state, which means that the data is never exposed in a decrypted state, thus preserving the privacy and integrity of security of the data during the model aggregation process [

3]. Therefore, this paper aims to develop a novel IoT framework utilizing a combination of FL, EC, and HE principles with the goal of predicting energy consumption patterns in a SG system while preserving user privacy E2E.

1.1. Research Challenges

A common challenge when working with ML is model tuning. An incorrectly tuned model overfits or underfits data that can produce inaccurate predictions as the model fails to determine the true relationship of the datas. Another challenge lies in utilizing HE to encrypt large amounts of data. While Cheon-Kim-Kim-Song (CKKS) and an HE schemes improve time complexity at the cost of accuracy, it still uses a lot of memory when encrypting workloads which is inefficient. Furthermore, to establish P2P architecture, a communication protocol is required between peers and a method of establishing P2P connections in the first place. While utilizing a protocol such as Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) can be more insecure than other methods of communication such as Hypertext Transfer Protocol Secure (HTTPS) or other Transport Layer Security (TLS) protocols due to vulnerabilities such as Man-In-The-Middle (MITM) attacks. HTTP makes for convenient setup for the purpose of demonstrating the security of the framework itself in a secure sandboxed simulation environment. However, in this study, we addressed the following research question.

What federated learning IoT framework can be developed and tested to predict energy consumption and to preserve user-privacy in smart grids using homomorphic encryption?

1.2. Research Scope and Contribution

The main contribution of this paper is the creation and verification of a SG IoT framework for predicting energy consumption using peer-to-peer federated learning (P2PFL) and HE to preserve user-privacy. This research offers detailed review and analysis of existing frameworks and approaches of privacy-preservation using FL and HE. We also explore the application of the framework in this space by developing a software simulation to evaluate the practicality of our framework in a real-world scenario. For the literature review, we looked at recent work over the last five years using well known databases such as Google Scholar, Scopus, Elsevier Science Direct, and IEEE Xplore library. Search terms used in this paper include federated learning framework, smart grid federated learning framework, federated learning IoT framework, machine learning for federated learning.

The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

We propose a novel federated learning smart grid IoT framework using P2PFL and HE principles to secure model parameters (by extension, user data) in the model aggregation process between peers in an EC context. To this end, we provide an analysis of the existing FL IoT framework focusing on privacy-preservation within the realm of SG IoT to identify research gaps and areas for contribution.

In the context of IoT, we explore a practical application of the framework with IoT devices involving SG energy consumption and optimization using software simulation. To this end, we develop a simulation model for system performance evaluation and validation.

Finally, we contribute code (written in Python) for system design and practical implementation. To this end, we made our source code publicly available (

https://github.com/FilUnderscore/SG-P2PFL-HE) at no costs so that network researchers and engineers can make a substantial contribution to this emerging field, especially energy consumption prediction with privacy-preservation.

1.3. Structure of the Article

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. The related work on FL frameworks in a SG setting, as well as the unification of P2PFL and HE are presented in

Section 2. The SGIoT framework design is presented in

Section 3. The system simulation as well as an HE implementation is presented in

Section 4. The research design and methodology are discussed in

Section 5. The system evaluation and test results are presented in

Section 6; the practical implications are also discussed in this section. Finally, the paper is concluded in

Section 7.

Table 1 lists the abbreviations used in this paper.

2. Related Work

Several studies have been published looking at developing FL frameworks in a SG setting, utilizing FL to develop power consumption forecasting models through load forecasting in a privacy-preserving manner. Abdulla, N. et al. [

2] implements an adaptive FL framework to forecast energy consumption in smart cities in an efficient and robust manner with custom models with EC architecture, including benefits such as privacy-preservation, lesser error rates and faster training times.

Liu, Y. et al. [

4] also proposes a FL framework which looks to distribute forecasting models during model training instead of distributing user data to preserve user privacy using EC. Roy, A.G. et al. [

5] first introduced P2PFL as an alternative to conventional FL where a Peer-to-Peer (P2P) network architecture is adopted where any individual peer can begin the model training process for their own model by fetching models from other peers. The motivation for P2PFL was largely focused on the concern of data sharing “due to ethical and legal regulations” of medical data between medical centers [

5]. The paper looked at sharing Federated Learning models between different medical centers without the need for medical data to be shared/exposed between them [

5]. While this paper used individual clients to perform training and communication with each other, we would apply a similar concept, but the clients would be the edge devices, while the IoT devices would act as a “sensor”, collecting data to be encrypted and transmitted to the edge devices for processing and training of the model data [

5].

Hijazi, N.M. [

6] introduced FHE as a viable method of privacy-preservation when exchanging models within a P2PFL framework. Wen, H. et al. [

7] also investigated using FHE for privacy-preservation but for the purposes of detecting electricity theft patterns on CKKS HE-encrypted data.

2.1. Research Gaps and Areas for Contribution

While the existing research works (

Table 2) consider privacy-preservation aspects within the ML model definition, they do not consider privacy-preservation aspects within the rest of the FL pipeline, namely interclient data exchange security measures and localised data security on the clients themselves. We can observe that while [

7] incorporates CKKS HE for privacy-preservation, it uses centralized FL which limits privacy-preservation as the central server is more vulnerable to targetted attacks such as a Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attack. Looking outside of SG, we can observe that while [

6] introduced P2PFL-E (a subset of P2PFL using FHE), supporting model aggregation on a single chosen peer at a time, which then redistributes the aggregated model to the other peers.

An IoT framework incorporating a variant of P2PFL with HE to preserve user privacy in energy consumption is a potential research gap and areas for contribution to the field. Therefore, in this paper, we focus on developing a smart grid IoT framework by integrating P2PFL architecture using HE principles. The proposed framework is discussed next.

3. Description of the Proposed Framework

Given the knowledge of the types of FL architecture that can be implemented, we propose a framework utilizing a combination of hierarchical and decentralized FL [

1]. The key concept is to use edge devices to perform both model computations for the clients and to communicate with other edge devices in a decentralized manner. All the devices are using end-to-end encryption to ensure that the chain of privacy starts with the client [

1].

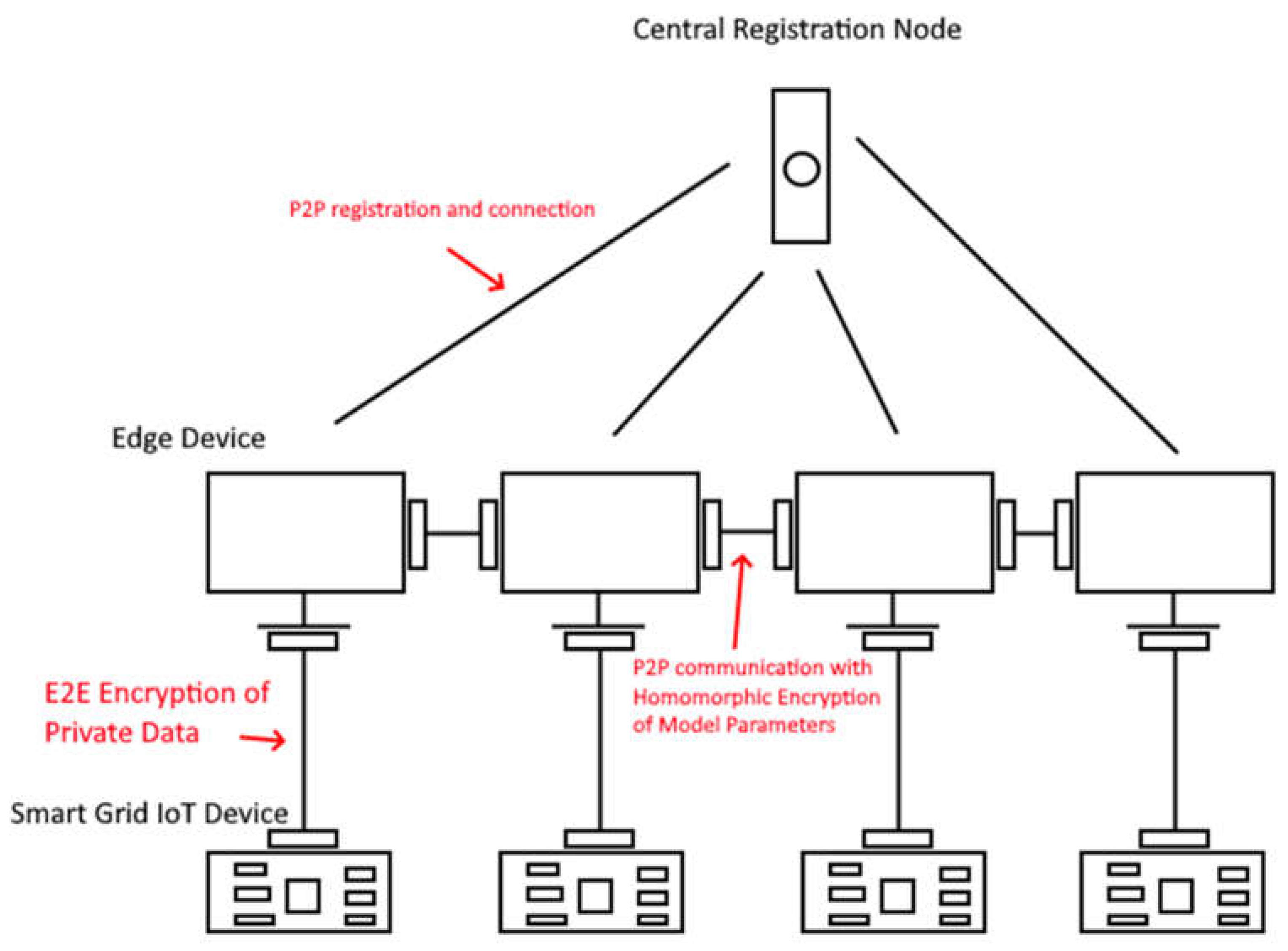

Our proposed framework is based on P2PFL principles (see

Figure 1) in which edge devices connect to each other using P2P networking. The data exchanged between peers is encrypted using CKKS fully homomorphic encryption (FHE). Initially, a peer establishes connection with a central registration Node acting as a repository where any peer in the network can query to get connection details for other peers connected to the network. Likewise, any number of SG IoT devices can be connected to specific edge devices using E2E encryption. These devices can act as “sensors” to collect data to be encrypted and transmitted to the edge devices for processing and training of the model data [

5].

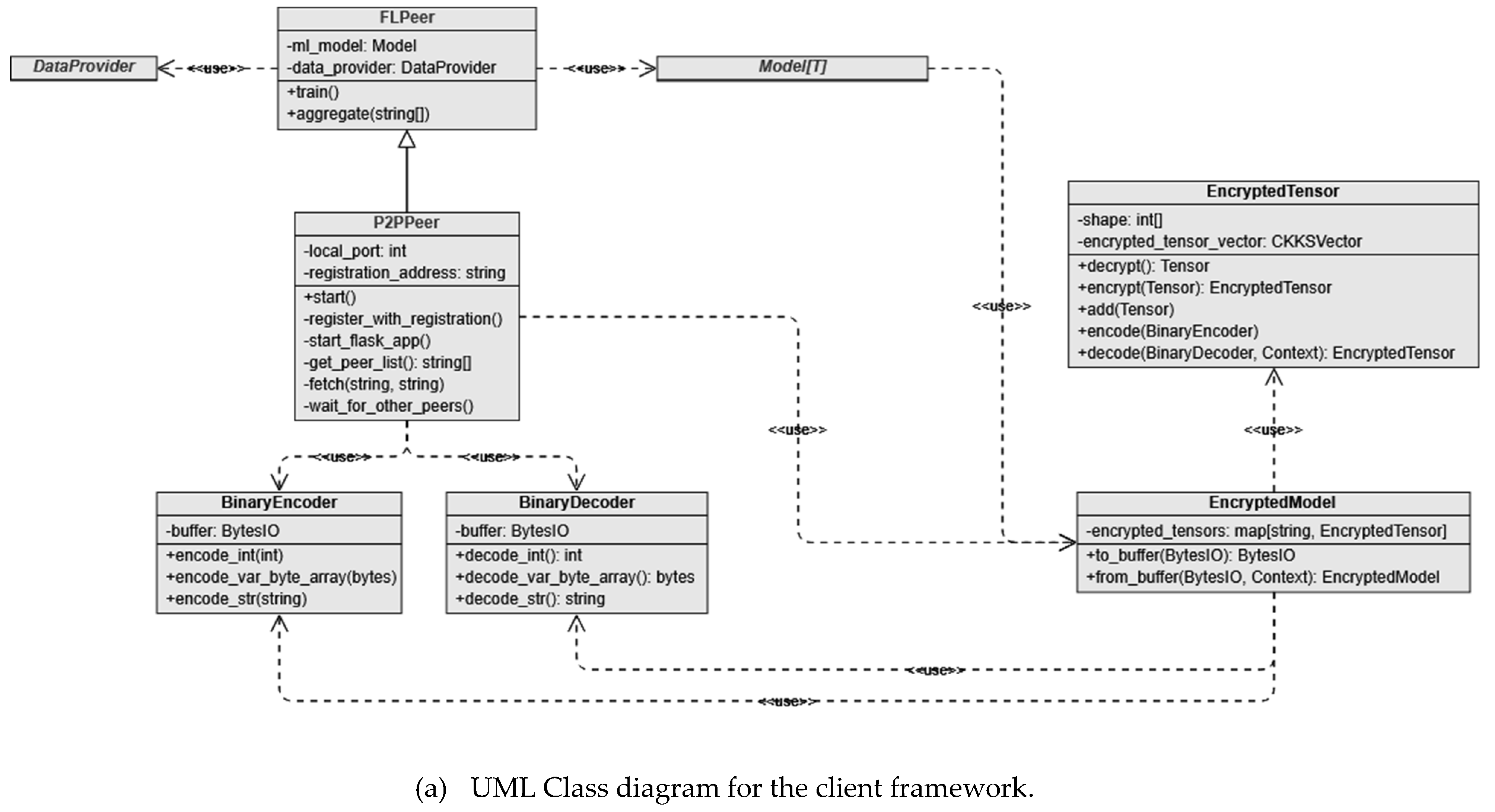

Our proposed framework is implemented using Python programming with various libraries, including PyTorch, Darts, Pandas, TenSEAL, MatPlotLib, and Flask. The framework consisits of four main components: (i) the common client framework (see

Figure 2a), (ii) client data providers that feed data during the model training process (

Figure 2b), (iii) model wrappers which abstract the model training logic (

Figure 2c); and (iv) the central registration node (

Figure 2d). The framework we use several uses PyTorch for the ML training/validation framework, while Darts is used for its out-of-the-box time-series based Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) model configuration. Pandas is used to perform data transformation and processing for feeding into the RNN model, and Flask is used to the host the client and central registration node instances. Furthermore, TenSEAL is used to provide an interface to Microsoft SEAL to perform FHE. This technology stack was used to demonstrate that the proposed framework is feasible and could theoretically be implemented with any other technology stack that supports the same fundamental principles of ML model training, client socket hosting, data transformation and processing tools, and a fully working FHE implementation.

We design the framework with flexibility and security in mind, allowing the user to provide their own ML model wrapped by a supported MLModel (e.g. MLTSModel for ML models that use TimeSeries RNN models). This framework handles all the model training, aggregation, and prediction logic securely. The DataProvider class is used to both parse and provide data (e.g., CSVTSDataProvider to parse TimeSeries data from a Comma-Separated Values (CSV) file) to an MLModel. Each peer can run either within a single instance of the program (using FLPeer) or as an individual instance (using P2PPeer) to share a registration server with other peers that manage peer registration in a similar fashion to EdgeFL.

Each peer requires a DataProvider instance to be provided along with an MLModel which can then have either the train function invoked (for the FLPeer implementation) or the start function invoked (for P2PPeer implementation) to begin the training process. Once the training process is completed, the function returns and then the user can call the aggregate function to manually aggregate peers (if using FLPeer implementation), otherwise it will be automatically handled if the user is using the P2PPeer implementation.

3.1. P2P Communication

P2P communication is supported if the user opts to use the P2PPeer implementation to perform FL. This communication is established between peers through the registration server where each peer is then able to communicate between each other without the need for the registration server. The registration server serves as a peer list that new and existing peers can query to communicate and exchange model parameters with.

Communication between the registration server and P2P peer is established using HTTP. When the peer first establishes connection with the registration server, it sends through JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) data as a form using a POST request to register itself with the registration server. From here on, the peers can submit GET requests to the registration server to get peer data to establish direct communication with other peers that are registered with the registration server. Furthermore, classes for binary data encoding and decoding were introduced to allow better cross-peer communication and interpretation of encrypted model parameters.

4. Implementation Aspect of Fully Homomorphic Encryption

Specifically, we utilize the CKKS encryption scheme by Cheon et al. (2016) to encrypt floating-point values (used heavily by tensors which represent the model parameters as matrices). The reason we opt to use the CKKS scheme and not the Brakerski-Gentry-Vaikuntanathan (BGV) encryption scheme [

8]. This is because the CKKS scheme is much better at efficiently encrypting floating-point values which are allowed to accumulate minor error resulting in approximate value encryption. While BGV is better suited for cases where numerical accuracy must be preserved throughout the encryption stage which severely limits plaintext storage under hard memory constraints. Because of these differences, CKKS is better suited for encrypting values such as model parameters as numerical accuracy is not of utmost importance in the case of ML workloads. The BGV is better suited for ensuring plaintext integrity. Equation (1) is transforming a tensor from a matrix form to a vector form using the get_tensor_as_vector function for more efficient FHE encryption.

To perform FHE encryption on an entire ML model, we need to consider encrypting all relevant model parameters to ensure that no malicious actors can intercept and decipher any weight values which could lead to data leakage in a secure setting. We do this by performing encryption of all tensors which represent the model parameters in an ML model. This can, however, be a very expensive operation to perform when you have tensors with dimensions as large as 784 rows by 69 columns. Initial tests showed that memory usage skyrockets when attempting to encrypt tensors of these dimensions which consume an excess of 4GB and beyond which would not be suitable for workloads carried out with especially large models that contain a lot of parameters, as in our case. An optimization we derived (see Equation (1)) as a consequence of these results was to first transform each tensor using a transformation function which maps a tensor

to a vector

and stores the shape in a separate vector

which will allow us to inverse this mapping transformation later on when we go to decrypt the encrypted tensor by first creating a 1-dimensional tensor which is then re-shaped using the encoded shape information that was derived from the initial encryption step. It is vital that the shape information is kept and exchanged as it is the only way that a tensor can be restored via inverse mapping once the initial mapping transformation has occurred. In this case, since each peer has the same model hyperparameters which specify the number of parameters present within the model as well as the shape of each tensor that represents these parameters, we do not need to worry about encrypting the shape information as there is no concern of data leakage of any of the parameters which would contain sensitive values during model aggregation. This optimization prevents memory consumption from skyrocketing by allowing the TenSEAL library to split and encrypt the resulting vector into multiple ciphertexts which consume less memory than the same data as an encrypted tensor, possibly due to how TenSEAL internally handles tensor encryption differently to vector encryption. This operation does disable specific operations such as matrix multiplication, however we do not intend to make use of these operations regardless so there are no disadvantages to encrypting tensors this way for our specific use case. Equation (2) performs vector addition on an encrypted tensor

with an unencrypted tensor U which has been transformed to a vector

temporarily using the mapping function defined in Eq (1).

Each peer generates a public key

and a secret key

and encrypts model parameters

with its own

.

, the ciphertext

is then exchanged with other peers (in turn retrieving their ciphertexts containing their model parameters) and can perform a variation of FHE to sum and multiply (divide using inverse multiplication) to each compute the global model parameters

. Equation (3) computes a shared ciphertext C' given a list of ciphertexts with a specific order of transformations (i.e. addition). Equation (4) computes the shared model S by decrypting the shared ciphertext C' and finding the average of n models (n being the number of peers in this case). These transformations in this example represent computing the global model ciphertext using the Federated Averaging (FedAvg) algorithm [

9].

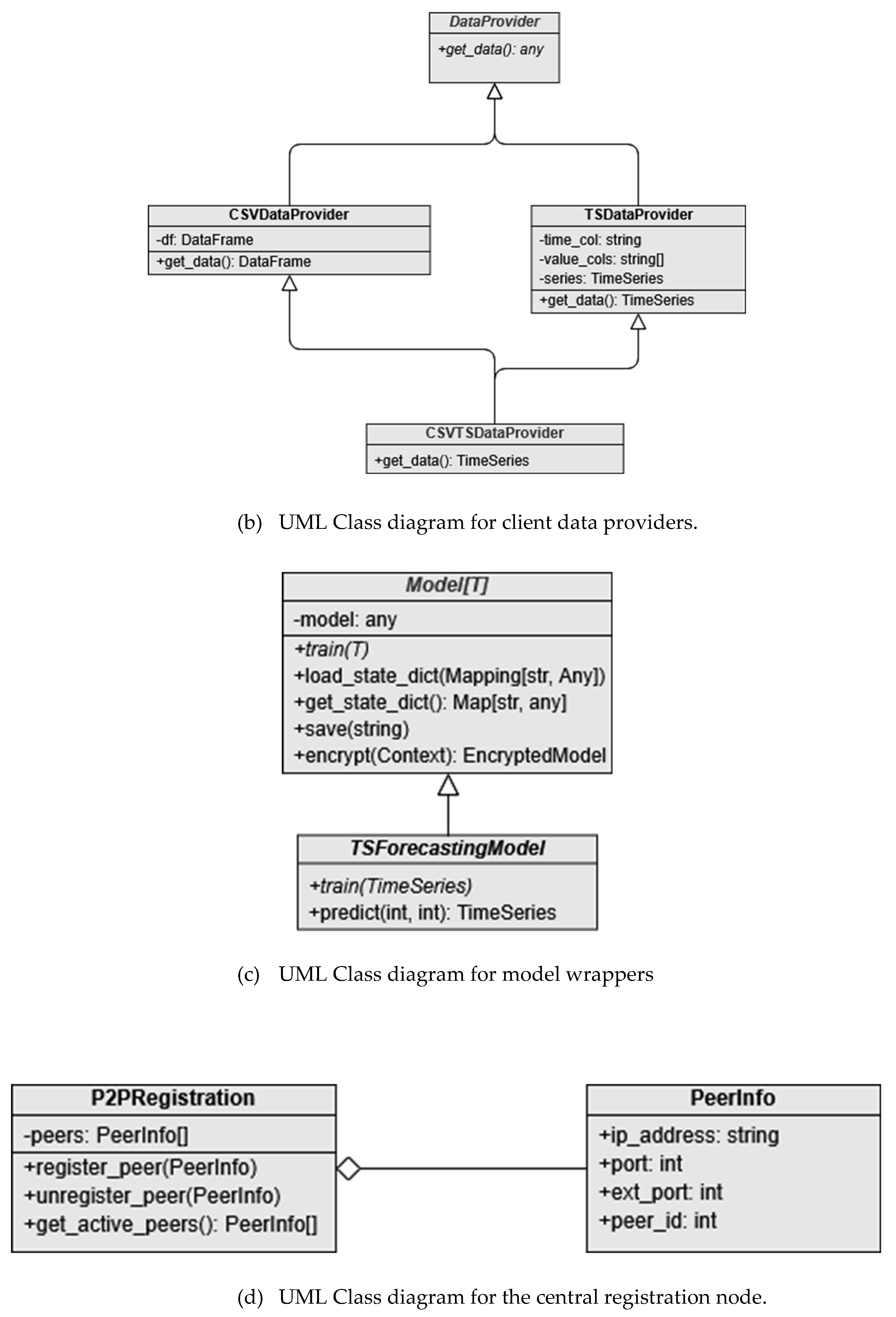

Once all the tensors representing the model parameters have been encrypted, we can then transmit these now encrypted tensors in a round-robin fashion to each peer within the P2P network and perform aggregation via the FedAvg algorithm with a different approach [

9]. We can first perform addition of each peer’s local model parameters with the encrypted tensors (using Eq (3)) representing a certain peer’s local model parameters, with each peer passing the encrypted model forward to another peer in round-robin fashion (see

Figure 3) until the encrypted model returns to the initial peer that made an aggregation request in the network. The initial peer can then decrypt the encrypted model,

where

represents the sum of all peer model parameters in a decrypted state, which will now contain tensors which represent the sum of all model parameters in the P2P network. We can then divide each of these tensors by the number of addition operations performed (see Eq (4)) on the encrypted tensors to determine the global FL model without the risk of model data leakage occurring at any stage in the aggregation process within the network while the model is in possession by a different peer. This process can be repeated on each peer within the network, allowing each peer to derive the same global model while maintaining both security and privacy within the network.

5. Performance Evaluation

To evaluate the FL framework, a simulated network is established by running multiple clients with different datasets on a local machine in a P2P configuration abstracted using the central registration node as a central repository to distribute connectivity details between each client. The SG dataset used for testing the FL framework in this paper is based on household electrical power consumption measured by smart meters in London [

10]. The dataset comes with smart meter reading data captured from 5,567 households in London between November 2011 and February 2014, in half-hourly, hourly, and daily sets of data, which allows for a flexible approach when testing the FL framework with an ML model [

11]. In this case, the daily dataset was used to train and predict daily trends in power consumption for households that are connected to the simulated SG system utilizing the FL framework. The ML model used is an RNN model using the Long Short-Term Model (LSTM) sub-model. We also opted to use the FedAvg algorithm for FL model aggregation [

9]. The FedAvg algorithm is a common algorithm that is used in FL when aggregating with various trained client models. These models can be replicated with a version that supports HE as pointed out in [

3], thanks to the homomorphism property of HE [

9].

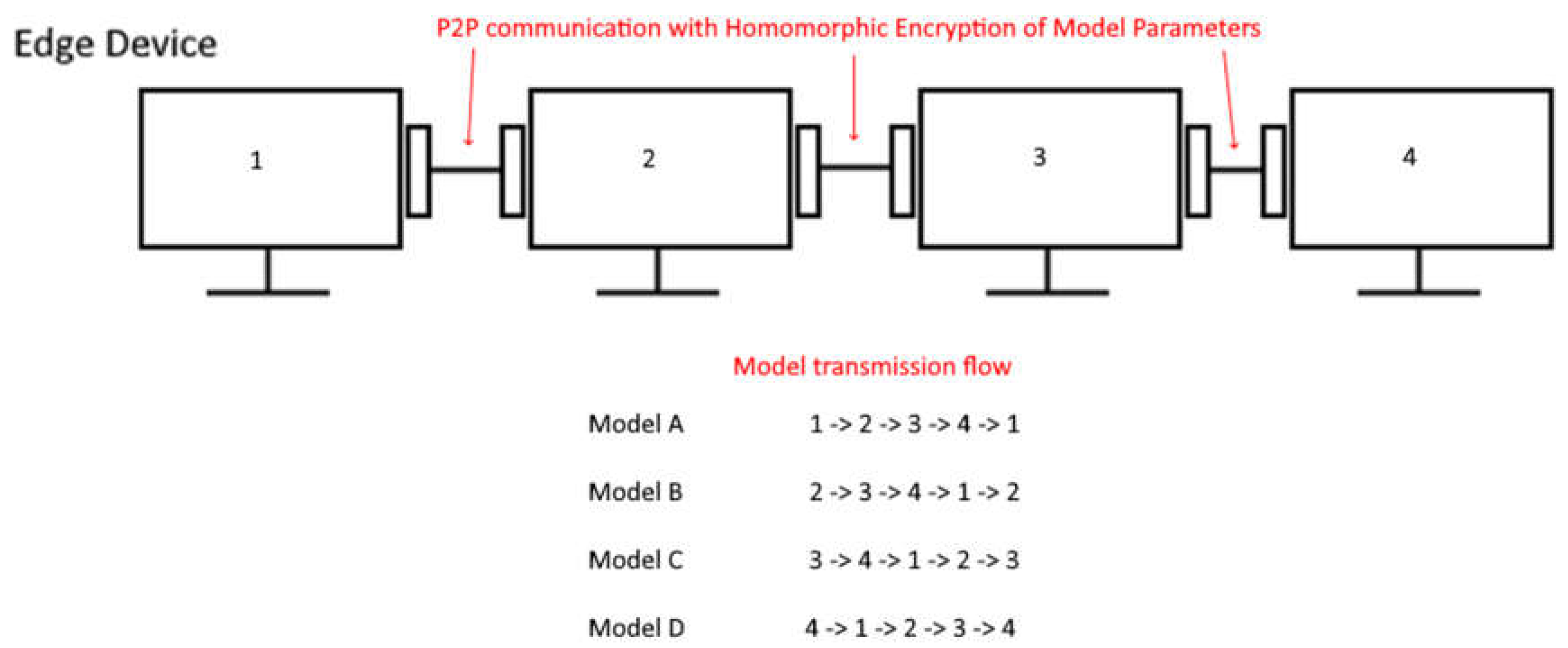

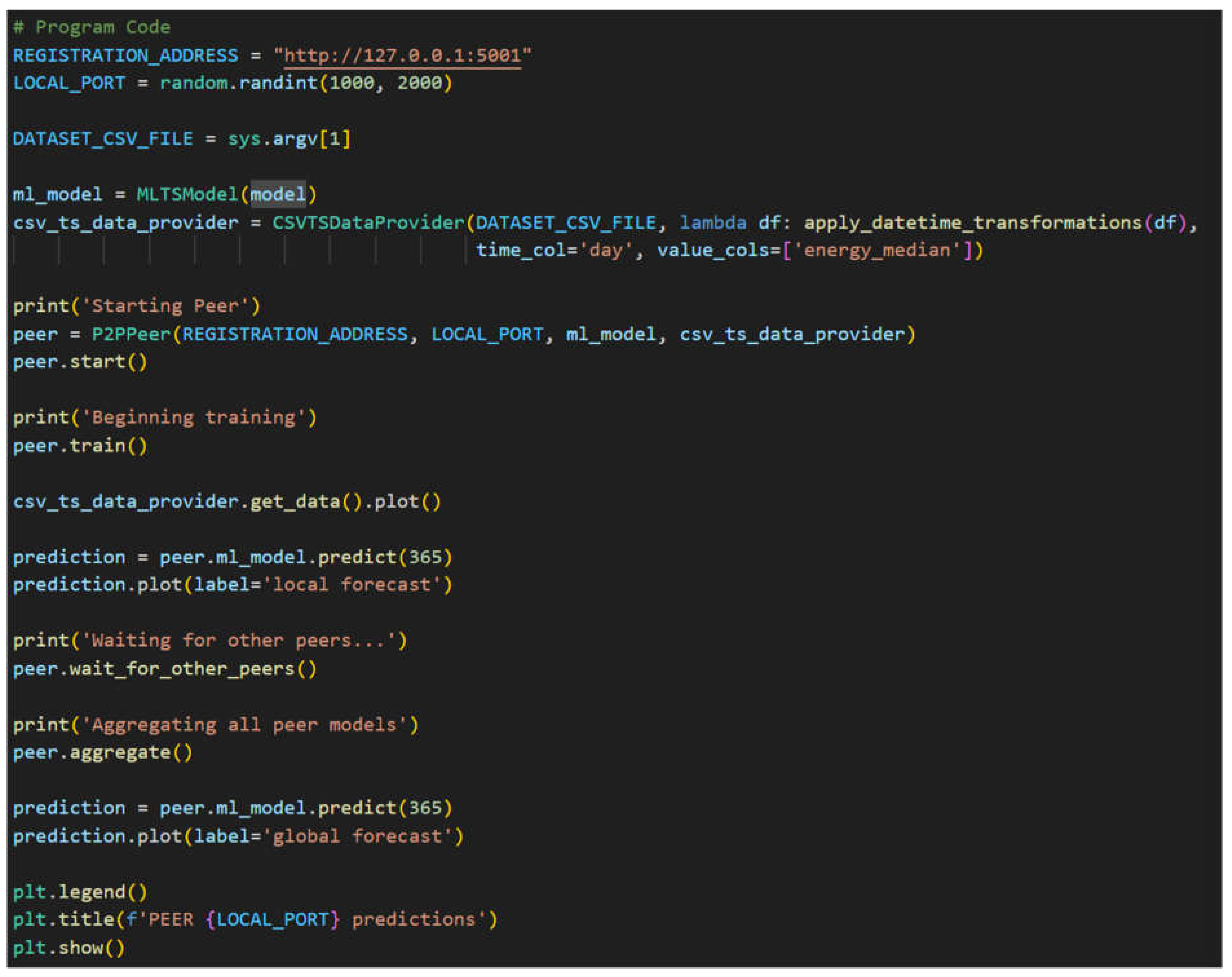

An example program utilizing the P2PPeer class is shown

Figure 4 to demonstrate using the framework to train a FL model among variable number of peers amongst each other sharing a central registration server using the P2P architecture. In this example, the CSV file is provided as the first parameter through the command line when executing the example program. The P2PPeer start function is then called which registers the peer to the provided registration server at REGISTRATION_ADDRESS with the randomly generated LOCAL_PORT for other peers to connect to via the registration server. The peer then performs local model training using the dataset provided and then waits for other peers to do the same via the registration server using the wait_for_other_peers function. Once the wait_for_other_peers function returns, indicating that all other connected peers have performed local model training, all connected peers then individually perform global model aggregation and distribution via the aggregate function. Once the global model has been finalized, the program plots both the local and global model predictions against the dataset provided.

5.1. Simulation Environment

To evaluate the effectiveness of our FL framework, we use Python-based implementation in conjunction with the dataset described in

Section 5. This provides a suitable simulation environment replicating a real-world scenario in which the framework would be used. Training is done on an NVIDIA Graphics Processing Unit (GPU) utilizing Tensor Cores to improve training performance during the simulation due to the amount of time it can take to train the same model in a Central Processing Unit (CPU), using the PyTorch CUDA package. Additionally, the tuned model parameters are provided (see

Table 3).

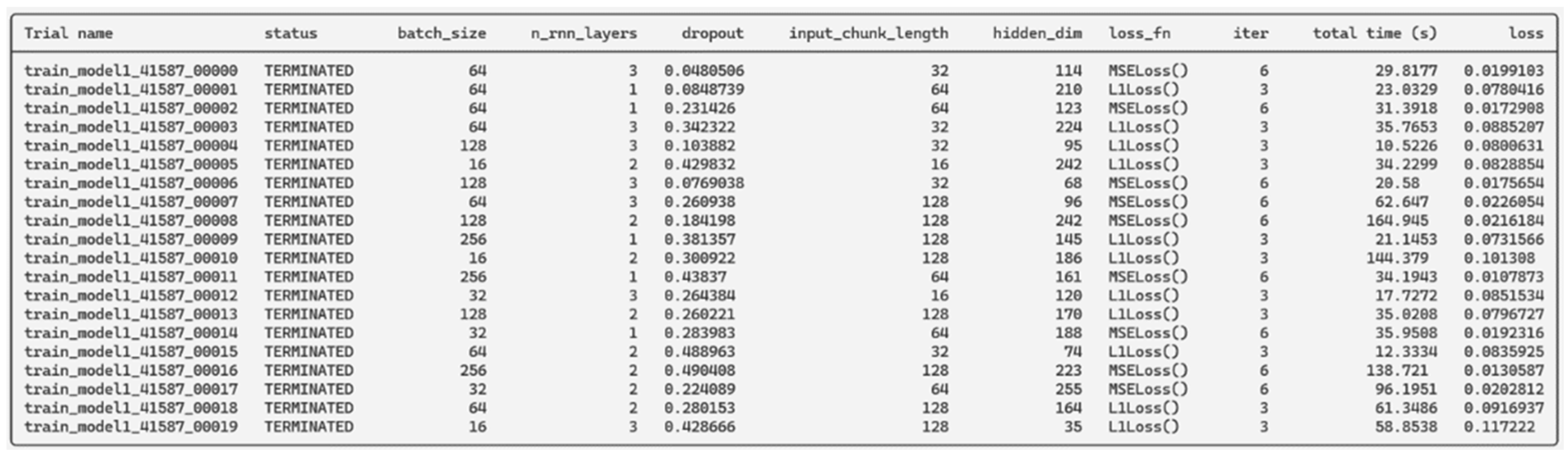

5.2. Hyperparameter Optimization

Hyperparameter optimization is performed using the Ray Tune Python library to test various specified model hyperparameters. This optimization allows us to find a good combination of values to tune the model and produce more accurate predictions with a lower validation loss during training. It allows us to train multiple models with varying hyperparameters in parallel with the same subset of data provided to each trial. In other words, models of the same kind with varying hyperparameters to fine tune the model using FL framework to generate SG predictions with both local and global forecasts for each peer. Once all trials run and results are obtained (see

Figure 5), one can feed the best hyperparameters found with the least validation losses into our generalized model.

5.3. Model Validation

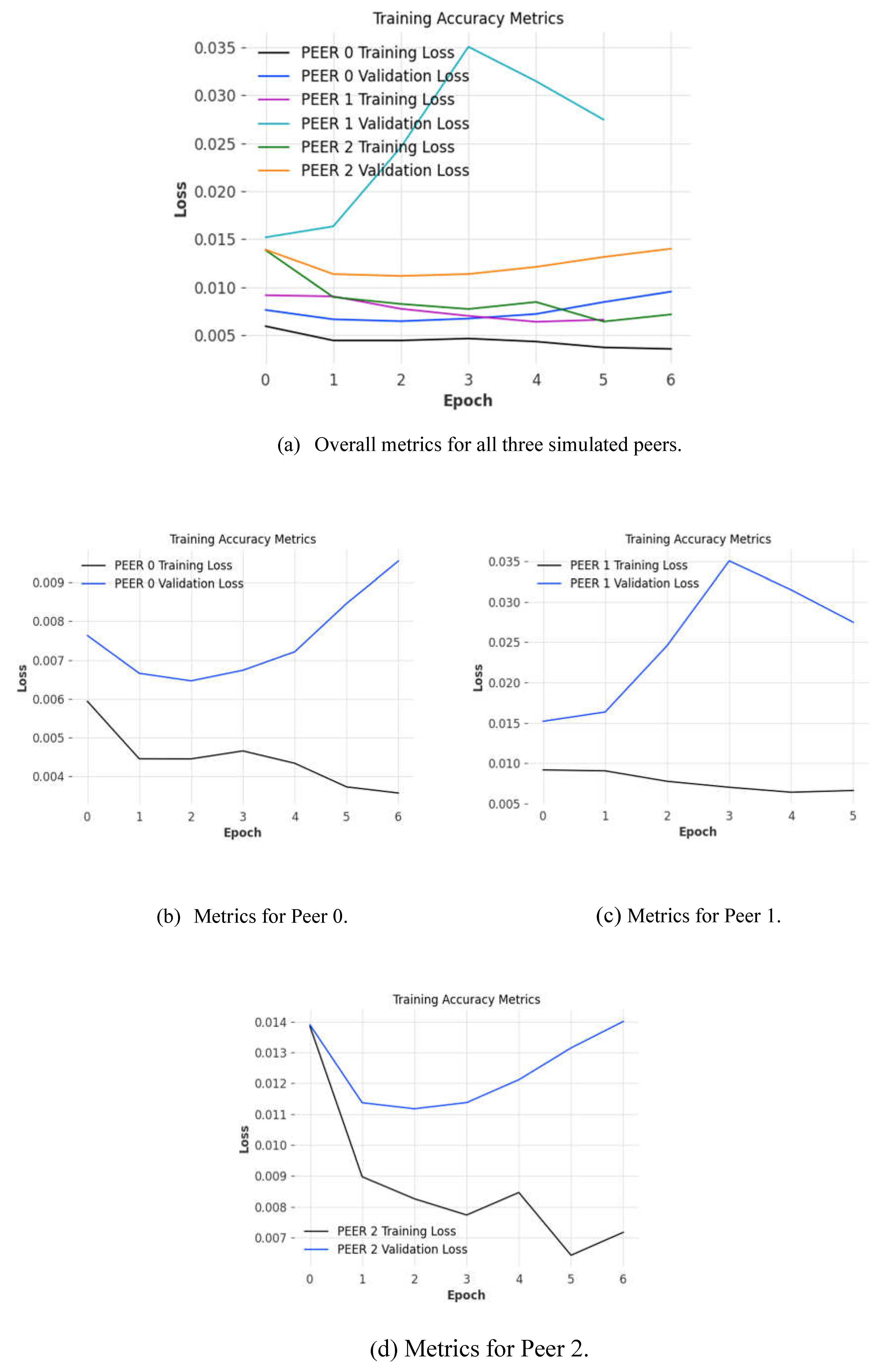

Model validation was performed by plotting and comparing training accuracy metrics (see Fig. 8) to ensure that the trained model parameters were optimal given the datasets provided. When training a model, great care needs to be taken when tuning model hyperparameters as it is easy to underfit or overfit a model which results in noisy and inaccurate predictions. Underfitting a model causes bad predictions as the model is unable to establish a relationship between inputs and outputs from the training dataset. Likewise, overfitting a model causes the opposite effect where a model will attempt to apply familiar relationships in a repetitive manner by looking at patterns in the data instead of learning the nature of these relationships from the data. To prevent underfitting and overfitting from occurring, we use early stopping which determines the most recent epoch where the difference between the training loss and validation loss was the most minimal, which is deemed to be the best fit for the model. By ensuring that we use the best fit for the models, we can have high confidence that the predictions that are produced by the models and global model produced following aggregation are as accurate as possible. This is especially true given that we utilize model hyperparameter optimization to ensure that the initial hyperparameters reduce the initial losses at the beginning of the process.

6. Results and Discussion

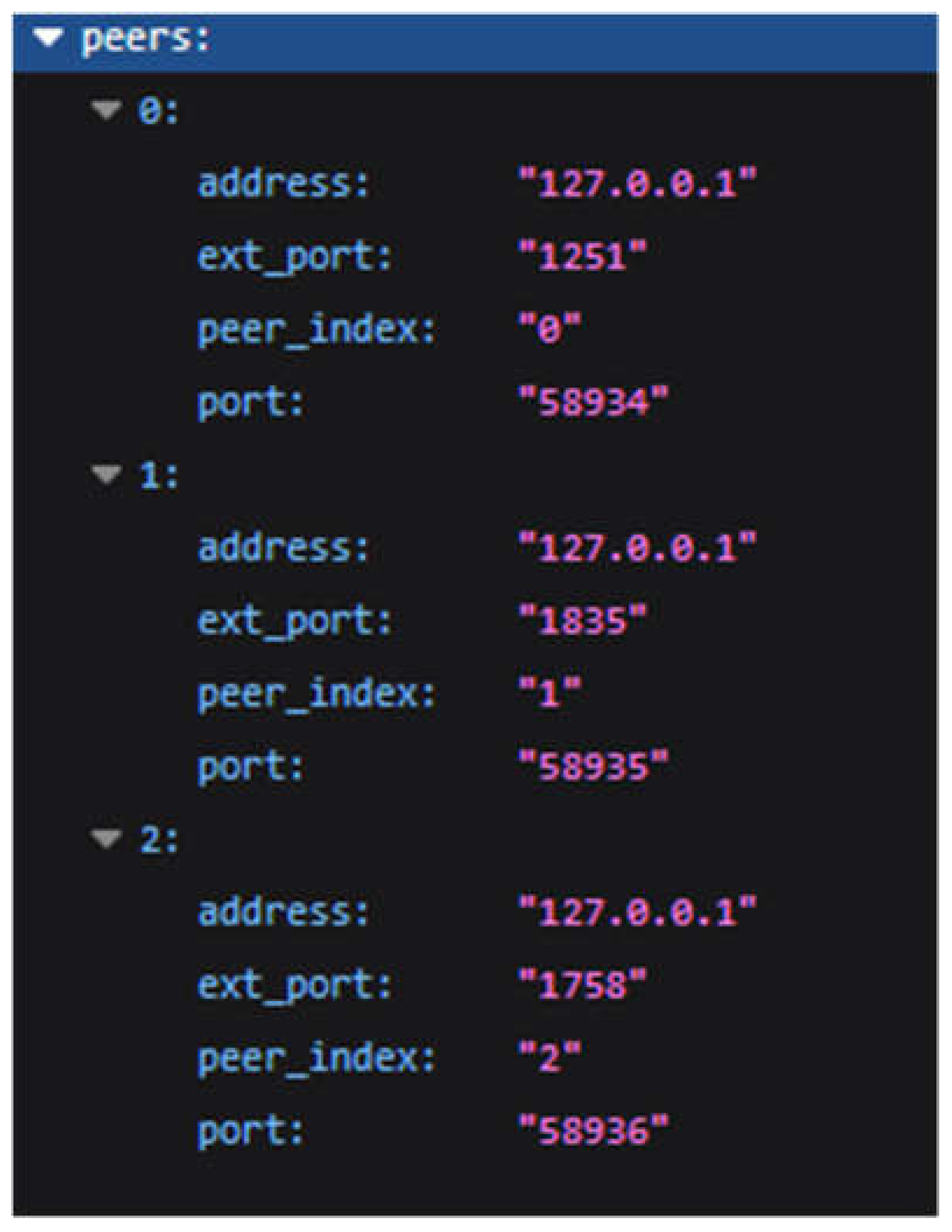

We can observe that the framework successfully computes a FL model from three separate ML models running on separate instances communicating via the previously established P2P architecture (see

Figure 6). The central registration node registers each peer’s address and port that a connection was established from and receives the communication port from the client itself. Additionally, the central registration node determines each peer’s index relative to each other to streamline the model aggregation process later. Because the P2P architecture does not require much information to establish, we eliminate any personally identifiable information that can be used to connect a client to a data source, thus preserving user privacy.

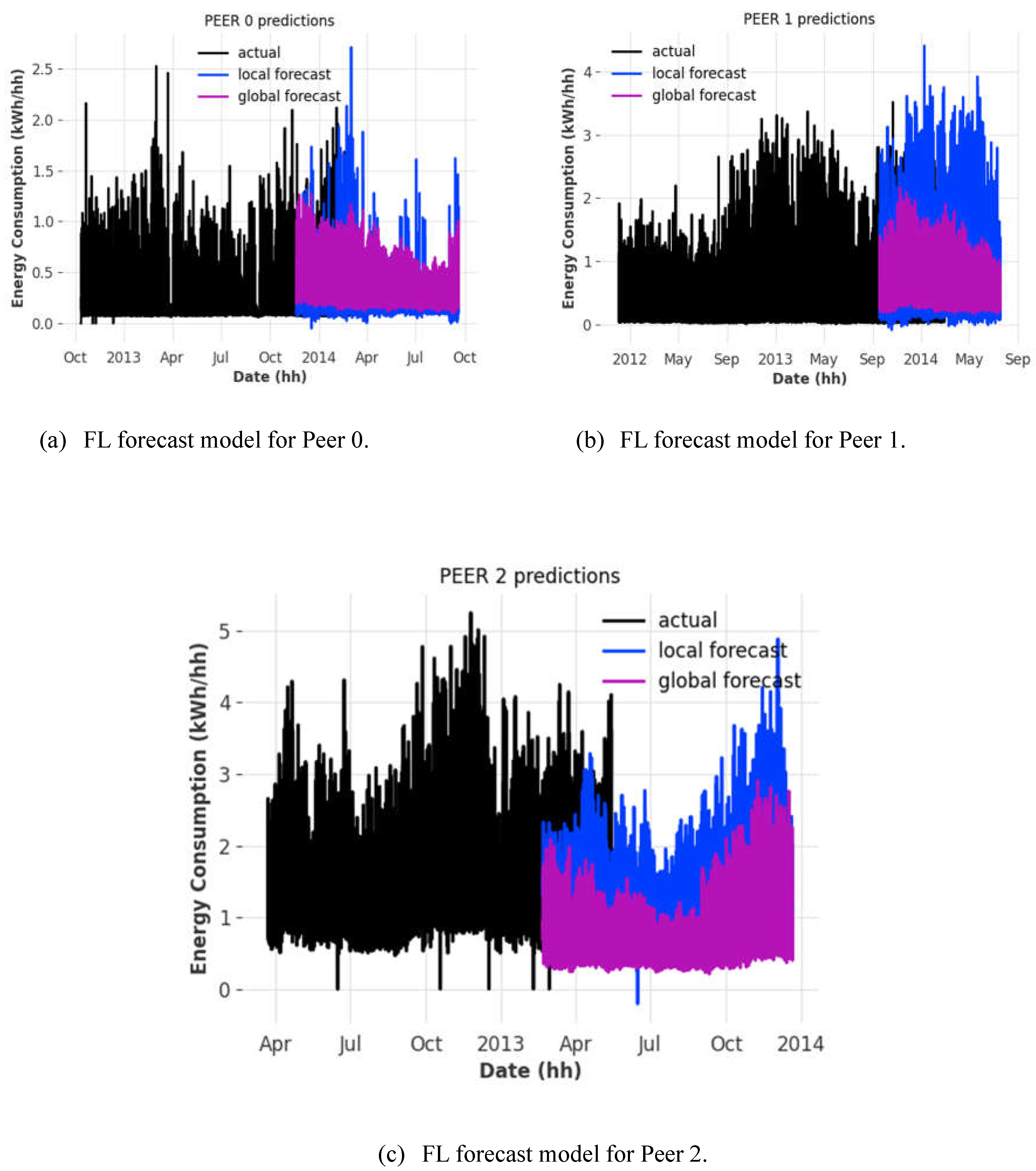

We can observe that the FL model is able to predict power consumption trends to some accuracy depending on the client that it is running on, compared to the local forecast model (similar trends and patterns depending on the date) (see

Figure 7).

We can observe that the individual accuracies of the localized models we train before aggregation occur (see

Figure 8) hover between 96% to 98% given the simulation parameters provided when training and validating the model against the test dataset. As with all cases with FL models, as the number of models that partake in the FL model aggregation process, the more accurate a FL model [

6]. Given our sample size of three is quite small, minor differences between datasets can cause dramatic fluctuations in the output of the FL model [

6]. However, given our focus is on improving the privacy-preservation aspect of the FL framework architecture, it is satisfactory for our case.

6.1. Practical System Implications

To ensure that the implementation of HE functions as expected, we can observe that a comparison between the model data stored locally on a client and the same model data fetched from another client has differing payloads by comparing the binary output in hexadecimal form. By looking at

Figure 9, one can observe that the model parameter “rnn.weight_ih_10” is encrypted from its original value using HE, which is then distributed to other clients in the P2P network in which each client will then average their own weights against the received encrypted models from other clients using FedAvg to derive the FL model securely, preventing any data leakage from occurring from model data.

Network planners can be benefitted from the P2P architecture that the framework utilizes by reducing communication delays between peers through direct connection instead of through a middle-man centralized server, as well as reducing cost by requiring less infrastructure. This does however come with a catch as individual peers will need to be equipped with enough computational power to perform ML workloads in a reasonable amount of time. However, the cost will ultimately depend on whether a fast and performant output is required, sacrificing power efficiency and cheap costs, and vice versa. In both cases however, privacy-preservation remains a key benefit of utilizing a P2P architecture in this case, as it becomes harder to attack a decentralized network instead of one relying on a central authoritative host.

7. Conclusions

In this paper, we proposed a robust and secure framework integrating FL, EC, IoT, and HE, for proving a real-world application of P2PFL for forecasting smart grid data to predict energy consumption patterns. Full encryption of the model parameters of the FL model with HE was achieved to allow privacy-preservation of sensitive data and prevent data leakage in a peer-to-peer networking environment while maintaining model accuracy during the end-to-end encryption process. Results obtained have shown that the accuracies of the localized models were up to 98% when training and validating the model against the test dataset. Future research work includes developing a new derivative HE encryption scheme where a shared private key can be generated from a set of public keys plus a given peer’s secret key to decrypt a shared ciphertext given that similar transformations are applied to both the ciphertext and the key. We uncovered a novel encryption scheme Multi-Key Fully Homomorphic Encryption (MKFHE) which allows multiple ciphertexts to be grouped into one generalized ciphertext to allow transformations to be performed on all grouped ciphertexts at once [

12]. However, MKFHE does not address the need for each peer to be able to independently perform these transformations locally, as it still requires each peer to exchange encrypted models in a round-robin fashion, which risks saturating network bandwidth in cases where many peers may need to perform model aggregation to compute the global model [

12].

References

- Panigrahi, M.; Bharti, S.; Sharma, A. Federated Learning for Beginners: Types, Simulation Environments, and Open Challenges. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Computer, Electronics & Electrical Engineering & their Applications (IC2E3); 2023; pp. 1–6.

- Abdulla, N.; Demirci, M.; Ozdemir, S. Smart Meter-Based Energy Consumption Forecasting for Smart Cities Using Adaptive Federated Learning. Sustainable Energy, Grids and Networks 2024, 38, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, R.; Mi, B.; Huang, D. A Federated Learning Framework Based on CSP Homomorphic Encryption. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 12th Data Driven Control and Learning Systems Conference; Xiangtan; 2023; pp. 196–201. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Dong, Z.; Liu, B.; Xu, Y.; Ding, Z. FedForecast: A Federated Learning Framework for Short-Term Probabilistic Individual Load Forecasting in Smart Grid. Electrical Power and Energy Systems 2023, 152, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.G.; Siddiqui, S.; Pölsterl, S.; Navab, N.; Wachinger, C. BrainTorrent: A Peer-to-Peer Environment for Decentralized Federated Learning. 2019.

- Hijazi, N.M.; Aloqaily, M.; Guizani, M. Collaborative IoT Learning with Secure Peer-to-Peer Federated Approach. Comput Commun 2024, 228, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Liu, X.; Lei, B.; Yang, M.; Cheng, X.; Chen, Z. A Privacy-Preserving Heterogeneous Federated Learning Framework with Class Imbalance Learning for Electricity Theft Detection. Appl Energy 2024, 378, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brakerski, Z.; Gentry, C.; Vaikuntanathan, V. Fully Homomorphic Encryption without Bootstrapping. 2011.

- McMahan, H.B.; Moore, E.; Ramage, D.; Hampson, S.; Arcas, B.A. Communication-Efficient Learning of Deep Networks from Decentralized Data. 2023. [CrossRef]

- D., J.-M. Smart Meters in London 2022.

- Networks, U.K.P. SmartMeter Energy Consumption Data in London Households 2015.

- Zhou, T.; Chen, L.; Che, X.; Liu, W.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, X. Multi-Key Fully Homomorphic Encryption Scheme with Compact Ciphertexts. 2021.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).