Submitted:

09 February 2025

Posted:

10 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Smart Environment

- Smart Cities: These use IoT technology and data analytics to improve urban living. With a growing global population, cities consume 75% of natural resources and contribute 60-80% of global greenhouse gas emissions, leading to resource depletion and global warming. The smart city concept addresses human needs and environmental concerns, enhancing the quality of life and social well-being [8].

- Smart Homes: is a system where appliances and devices can be controlled remotely using an internet connection, allowing homeowners to manage security, climate control, lighting, and entertainment systems from a distance. Smart doorbells, security systems, and appliances form part of the IoT ecosystem, collecting and sharing information. A smart home offers greater comfort, security, and environmental sustainability. Intelligent air conditioning systems use home sensors and online data sources to optimise operational decisions, forecasting home occupancy and conserving energy [3,9].

- Smart Agriculture: uses IoT sensors, GPS technology, and data analytics to monitor crop health, soil conditions, and livestock, resulting in optimised resource use, increased productivity, and sustainable practices. It goes beyond incorporating technology; agricultural machinery and equipment should have IT capabilities for semi-automated decision-making. This approach relies on big data technologies, IoT, satellite monitoring, interconnected data, and artificial intelligence [7,10].

- Smart Healthcare Systems: These systems utilize IoT devices and data analytics to monitor patient health, manage medical records, and enhance healthcare delivery efficiency. They include remote patient monitoring, telemedicine, and intelligent diagnostic systems. IoT can record patient data, generate diagnostic reports, and detect vital signs. Wearable devices like Fitbit and smart watches monitor physical activity, allowing users to set activity targets and track their health goals. This proactive approach saves time for patients and reduces healthcare costs [7,11].

2. Paper Structure

2.1. The Methodology

2.2. Fundamentals of Classification

- -

- Regression: This technique analyzes the relationship between target (dependent) and predictor (independent) variables. It predicts continuous numerical values by modelling this relationship, making it useful for forecasting and trend analysis tasks.

- -

- Classification: Assigns data to predefined categories or labels by identifying patterns in input features. It predicts discrete outcomes and applies to structured and unstructured data.

- A.

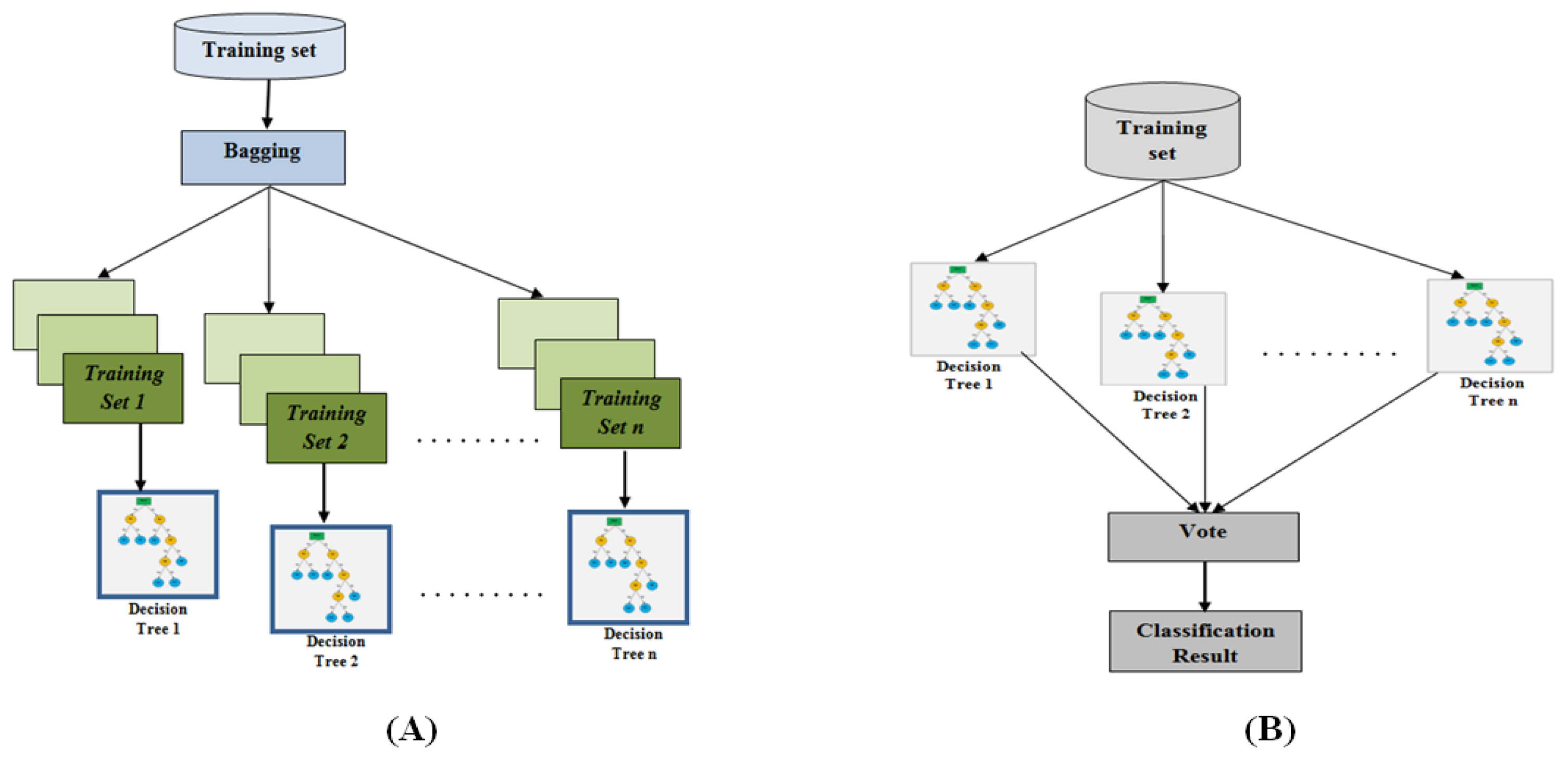

- Random Forest (RF):

- B.

- Gradient Boosting Machines (GBM):

2.3. Data Source and Description

2.4. Optimized Classifier Selection for Smart IoT Environments

2.5. Performance Measurement Matrices

- -

- True Positive (TP): A data point is classified as a True Positive (TP) in the confusion matrix when a positive outcome is predicted and the actual result matches the prediction.

- -

- False Positive (FP): A data point is classified as a False Positive (FP) when a positive outcome is predicted, but the actual outcome is negative. This is known as a Type 1 Error, where the prediction is overly optimistic.

- -

- False Negative (FN): A data point is classified as a False Negative (FN) when a negative outcome is predicted, but the actual outcome is positive. This is referred to as a Type 2 Error and is considered problematic as a Type 1 Error.

- -

- True Negative (TN): A data point is classified as a True Negative (TN) in the confusion matrix when a negative outcome is predicted and the actual result is negative.

- Accuracy: This metric represents the ratio of correctly classified data points to the total number of observations.

- Precision: Precision answers the question: What proportion of predicted positives were correct? In other words, it measures how often the model is correct when it predicts an item to belong to a particular class.

- Recall: Also known as Sensitivity, this metric indicates how many positive class predictions were made from all the actual positive instances in the dataset.

- F-Measure: The F-Measure combines precision and recall into a single score, offering a balanced evaluation of the model’s performance. The The score considers precision and recall at equal weights, returning values between 0.0 and 1.0. [30]

- Area Under the Curve (AUC): is a performance metric used in classification tasks.

- Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC): is a measure of the correlation between the predicted classes and the actual ground truth. MCC is widely regarded as a balanced metric, making it suitable even when the classes have significantly different sizes [29].

3. Results Analysis and Discussions

3.1. Comparison of Overall Performance for Both Methods

- ➢

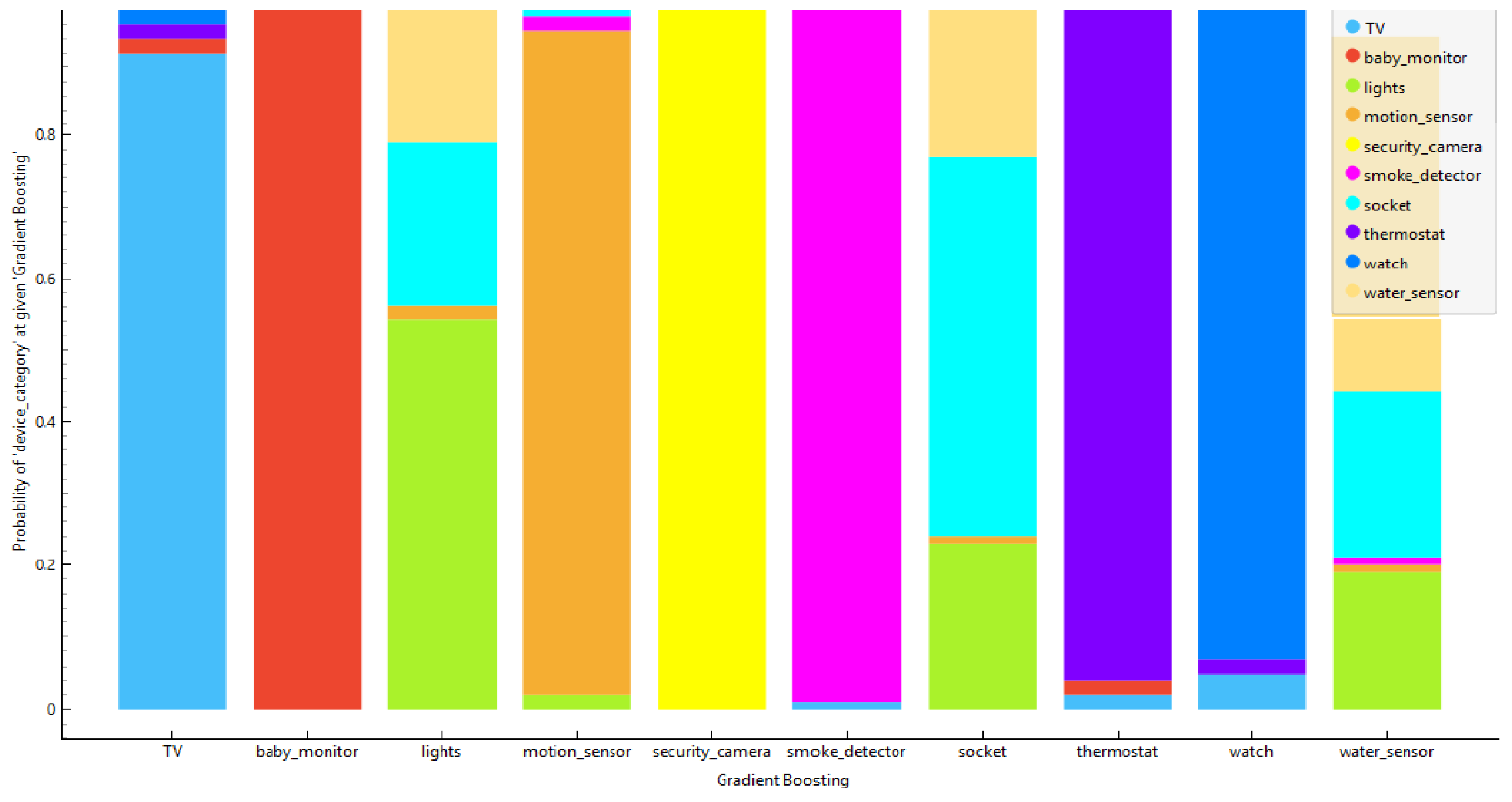

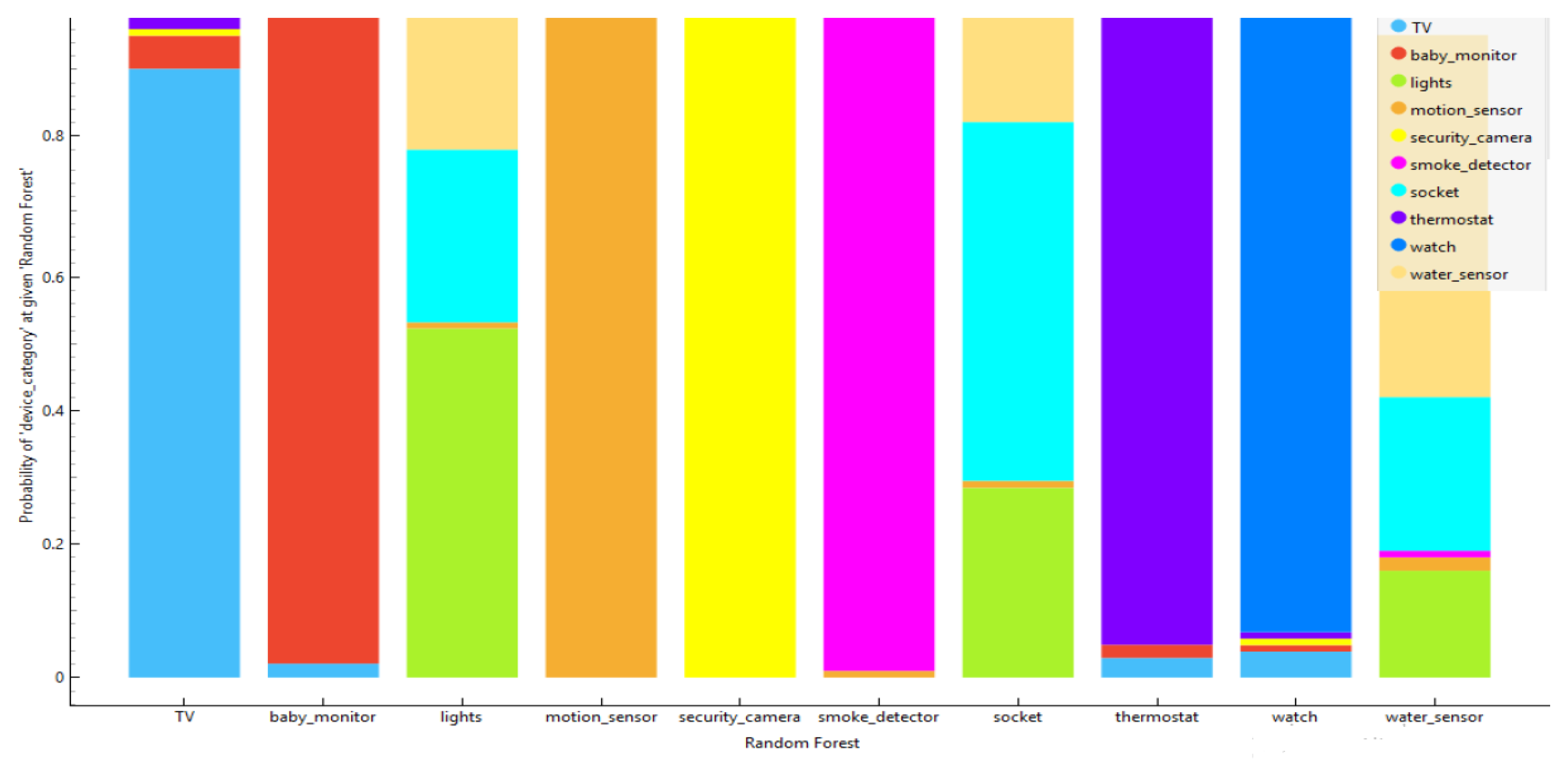

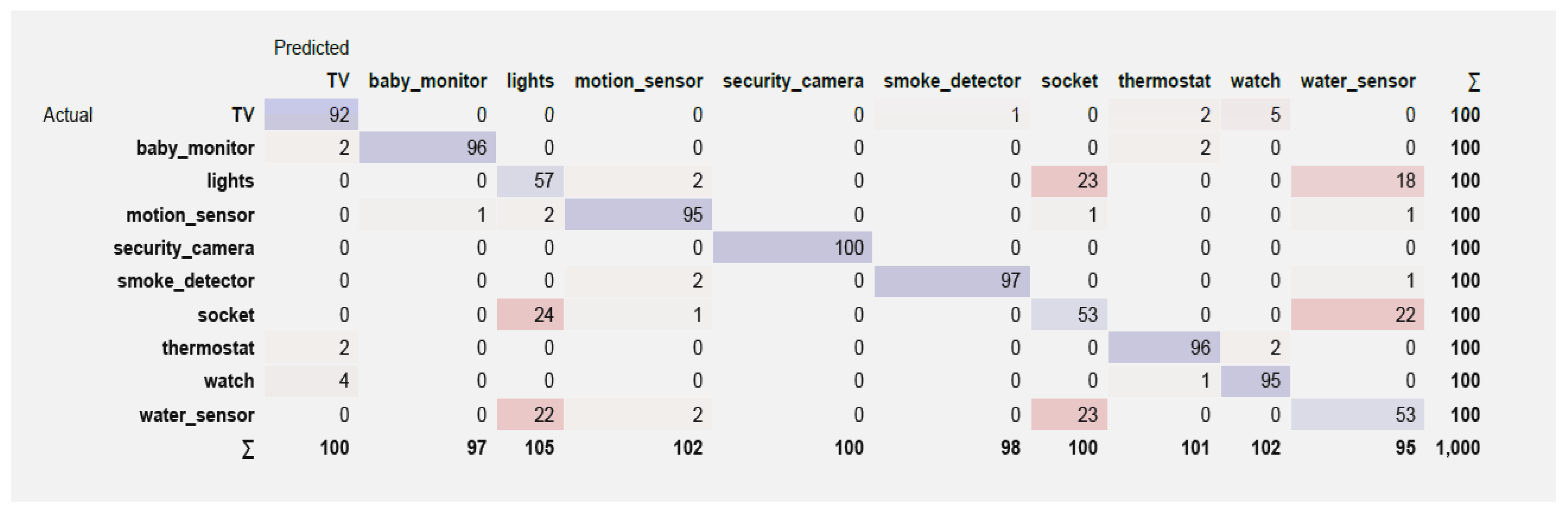

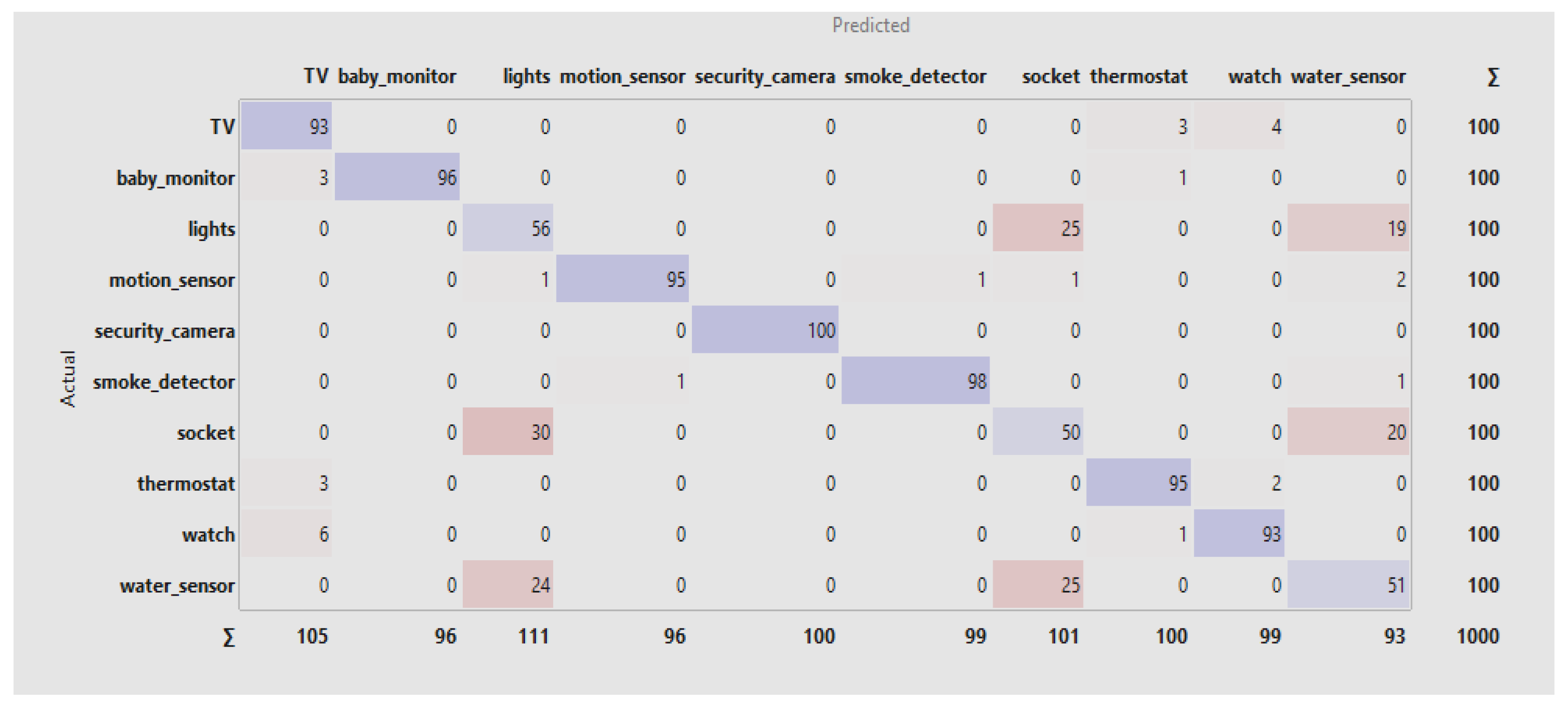

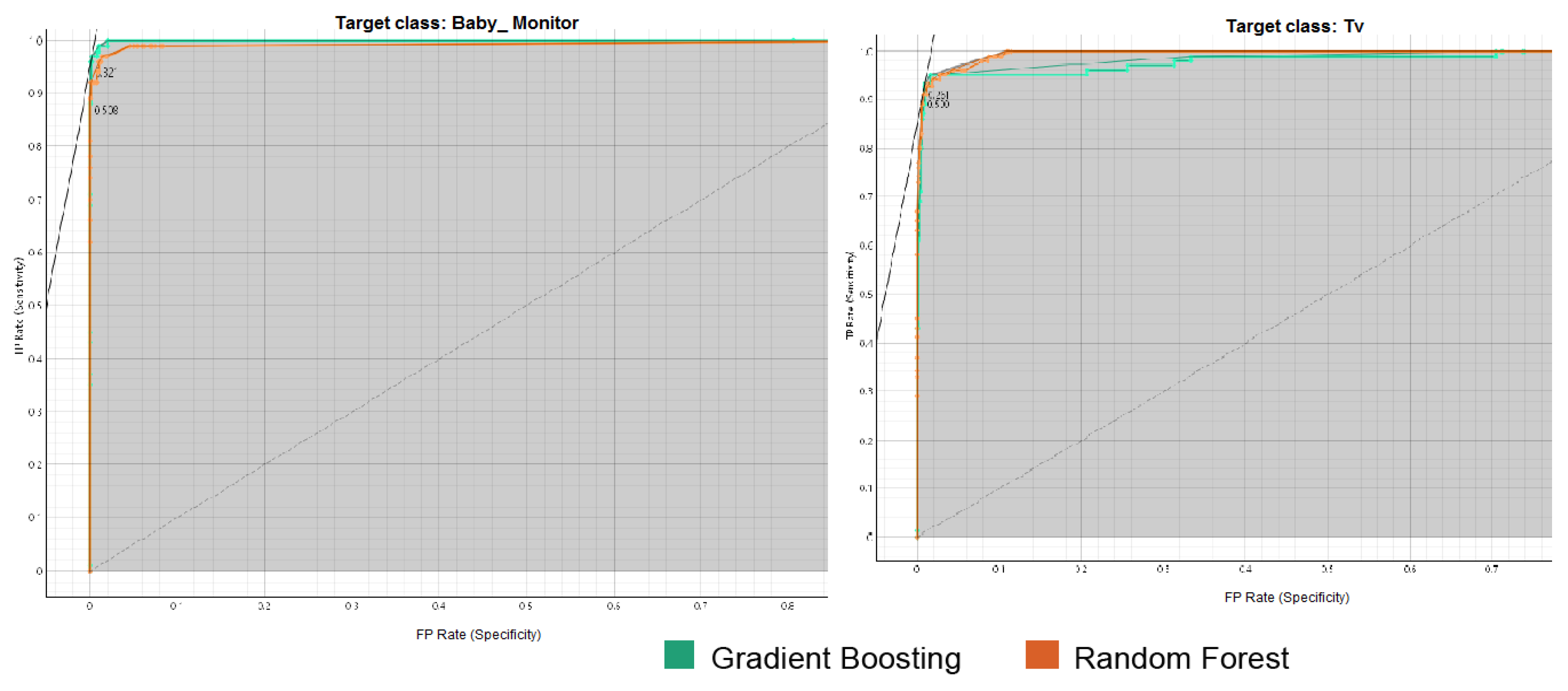

- TV: Both models demonstrated high accuracy, with Random Forest slightly outperforming Gradient Boosting regarding precision and recall.

- ➢

- Baby Monitor: Both models performed exceptionally well, with Gradient Boosting achieving a slightly higher F1 score.

- ➢

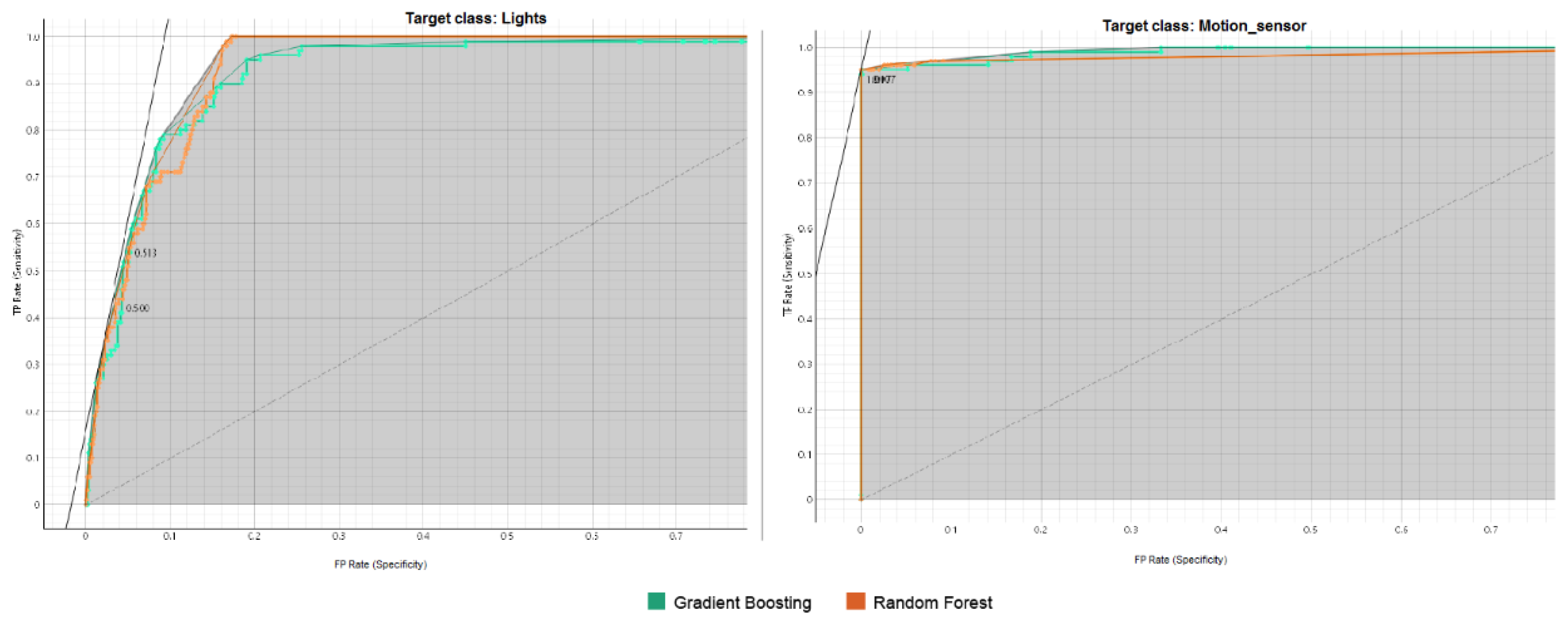

- Lights: Both models faced challenges with this class, exhibiting low F1 scores, recall, MCC, and precision.

- ➢

- Motion Sensor: Both models performed well, with Gradient Boosting showing a slight advantage.

- ➢

- Security Camera: Both models achieved optimal performance with high scores across all metrics.

- ➢

- Smoke Detector: Both models performed well, with Gradient Boosting achieving a slightly higher F1 score.

- ➢

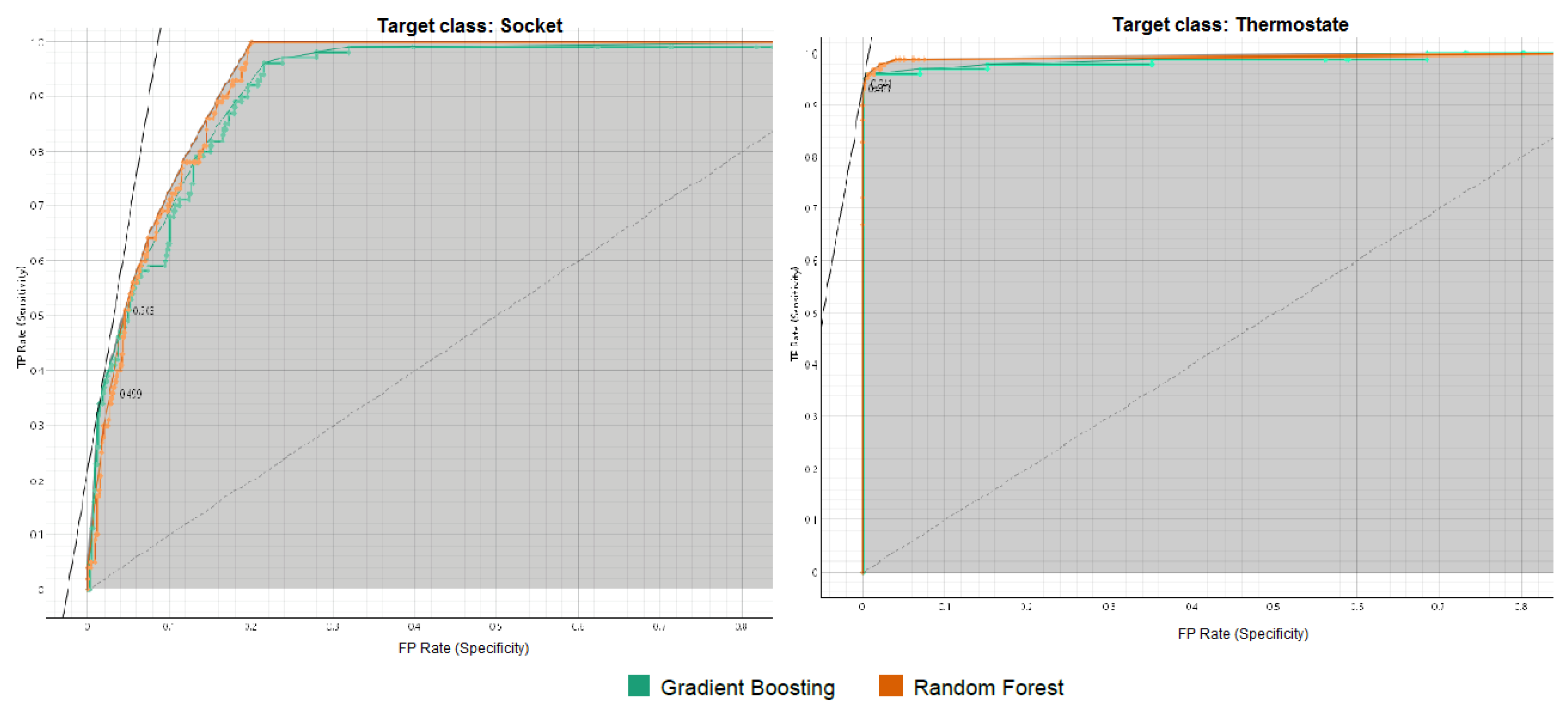

- Socket: Both models struggled with this class, exhibiting low F1 scores, recall, MCC, and precision.

- ➢

- Thermostat: Both models performed well, with Gradient Boosting achieving a slightly higher F1 score.

- ➢

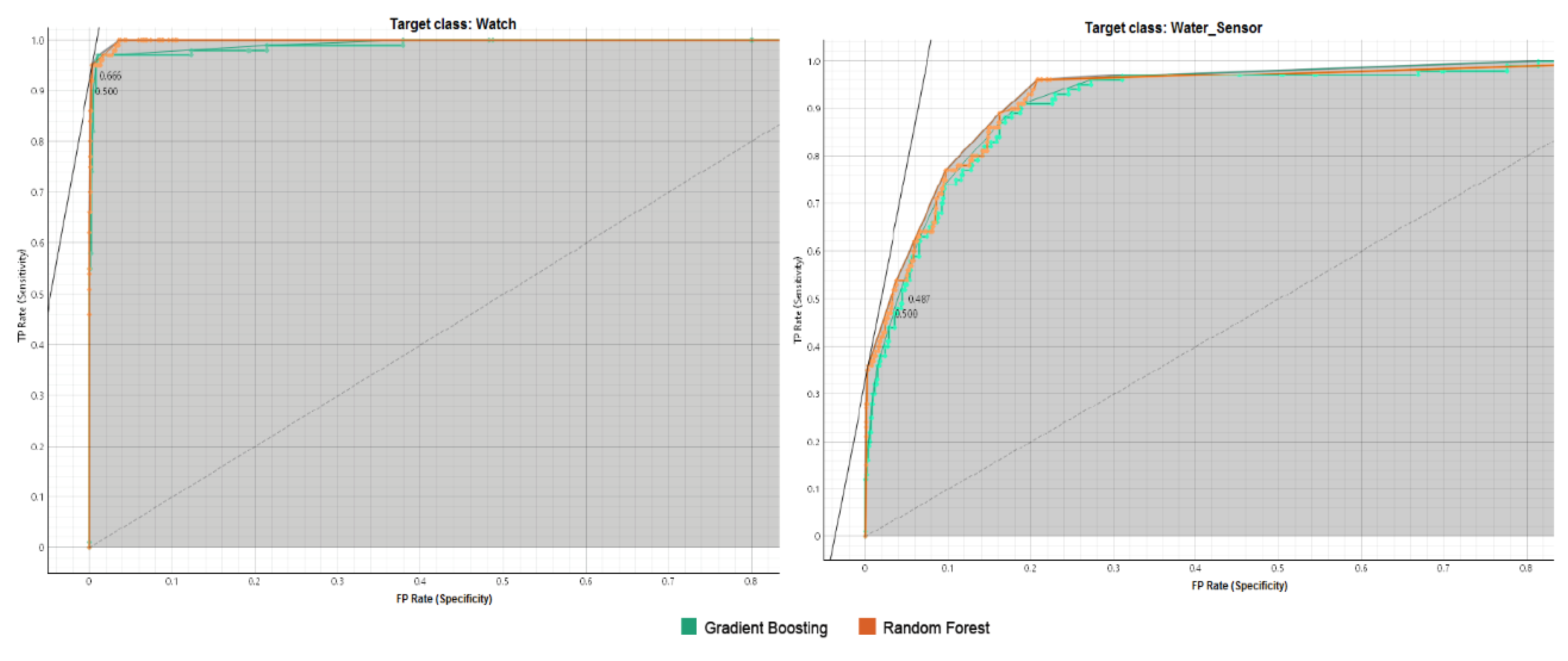

- Watch: Both models performed well, with Random Forest achieving a slightly higher F1 score.

- ➢

- Water Sensor: Both models achieved high AUC and accuracy but exhibited low F1 scores, recall, MCC, and precision.

3.2. Probability Distribution of the Target Variable for Both Models

3.3. The Confusion Matrix

3.4. Area Under the ROC Curve

4. Discussions

5. Conclusion

References

- Zahid H, Saleem Y, Hayat F, Khan F, Alroobaea R, Almansour F, Ahmad M, Ali I. (2022). A Framework for Identification and Classification of IoT Devices for Security Analysis in Heterogeneous Network. Hindawi, Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, S., Kalita, H., & Choudhury, T. (2019). Internet of Things (IoT): A Comprehensive Review on Architectures, Security Issues, and Countermeasures. IEEE Internet of Things Journal, 7(1), 1-24).

- Sagar V, SM Kusuma. (2015). Home Automation Using Internet of Things. International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET).Volume: 02 Issue: 03 | Jan-2015. Pg 1965 -1970. e-ISSN: 2395-0056.

- Al-Fuqaha A, Guizani M, Mohammadi M, Aledhari M, Ayyash M.(2015). Internet of Things: A Survey on Enabling Technologies, Protocols, and Applications. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials. [CrossRef]

- G. Hemanth Kumar Yadav, V.S.S.P.L. N. Balaji Lanka, K. Lakshmi Devi, A. Naresh, P.Naresh, Koppuravuri Gurnadha Gupta, B. S. (2024). Smart Environments IoT Device Classification Using Network Traffic Characteristics. International Journal of Intelligent Systems and Applications in Engineering, 12(3), 2422–2430. https://ijisae.org/index.php/IJISAE/article/view/5713.

- Rajesh Nimodiya A, Sunil Ajankar S. (2022). A Review on Internet of Things. International Journal of Advanced Research in Science, Communication and Technology (IJARSCT). [CrossRef]

- Ikrissi G, Mazri T. (2021). IOT-BASED SMART ENVIRONMENTS: STATE OF THE ART, SECURITY THREATS AND SOLUTIONS. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences. [CrossRef]

- ABDI H, SHAHBAZITABAR M. (2020). Smart city: A review of concepts, definitions, standards, experiments, and challenges . Journal of Energy Management and Technology (JEMT) Vol. 4, Issue 3. [CrossRef]

- Lin H, W. Bergmann N. (2016). IoT Privacy and Security Challenges for Smart Home Environments. Information, MDPI. [CrossRef]

- Zinke-Wehlmann C, Charvá K. (2021). Introduction of Smart Agriculture. Chapter 14 in book: Big Data in Bioeconomy, Results from the European DataBio Project (pp.187-190). Springer. [CrossRef]

- Pal Singh H, Kaur G. (2018) .Internet of Things(IoT): Applications and Challenges. International Journal of Advanced Research Trends in Engineering and Technology (IJARTET). ISSN2394-3785.

- Hannan A, Munawar Cheema S, Miguel Pires I. (2024). Machine learning-based smart wearable system for cardiac arrest monitoring using hybrid computing. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control. Volume 87. [CrossRef]

- Attaullah, H.; Sanaullah, S.; Jungeblut, T. (2024). Analyzing Machine Learning Models for Activity Recognition Using Homomorphically Encrypted Real-World Smart Home Datasets: A Case Study. MDPI, Applied Science. [CrossRef]

- Soleymani S, Mohammadzadeh S. (2023). Comparative Analysis of Machine Learning Algorithms for Solar Irradiance Forecasting in Smart Grids. arXiv:2310.13791, 13th Smart Grid Conference. [CrossRef]

- Saied M, Guirguis S, Madbouly M. (2023). A Comparative Study of Using Boosting-Based Machine Learning Algorithms for IoT Network Intrusion Detection. Springer, International Journal of Computational Intelligence Systems. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya D, Kumar Nigam M. (2023). Energy Efficient Fault Detection and Classification Using Hyperparameter-Tuned Machine Learning Classifiers with Sensors. Measurement: Sensors. [CrossRef]

- Tao P , Shen H, Zhang Y, Ren P, Zhao J, Jia Y. (2022). Status Forecast and Fault Classification of Smart Meters Using LightGBM Algorithm Improved by Random Forest. Hindawi, Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing. [CrossRef]

- Hameed A, and Leivadeas A. (2020). Traffic Multi-Classification Using Network and Statistical Features in a Smart Environment. IEEE 25th International Workshop on Computer Aided Modeling and Design of Communication Links and Networks (CAMAD). [CrossRef]

- Nath Mohalder R, Alam Hossain Md, Hossain N. (2023).CLASSIFYING THE SUPERVISED MACHINE LEARNING AND COMPARING THE PERFORMANCES OF THE ALGORITHMS. International Journal of Advance Research (IJAR). ISSN: 2320-5407. DOI URL:. [CrossRef]

- F.A.H. ALNUAIMI A , H.K. ALBALDAWI T. (2024). An overview of machine learning classification techniques. BIO Web of Conferences 97, 00133. [CrossRef]

- Boateng, E.Y., Otoo, J. and Abaye, D.A. (2020) Basic Tenets of Classification Algorithms KNearest-Neighbor, Support Vector Machine, Random Forest and Neural Network: A Review. Journal of Data Analysis and Information Processing, 8, 341-357. [CrossRef]

- Kim GI, Kim S, Jang B. (2023). Classification of mathematical test questions using machine learning on datasets of learning management system questions. PLoS ONE 18(10): e0286989. [CrossRef]

- Umer M, Sadiq S, Alhebshi RM, Sabir MF, Alsubai S, Al Hejaili A, Khayyat MM, Eshmawi AA, Mohamed A. (2023). IoT based smart home automation using blockchain and deep learning models. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 9:e1332. [CrossRef]

- Jin, HJ, Ghashghaei, FR, Elmrabit, N, Ahmed, Y & Yousefi. (2024). Enhancing sniffing detection in IoT home Wi-Fi networks: an ensemble learning approach with Network Monitoring System (NMS). IEEE Access, vol. 12, pp. 86840-86853. [CrossRef]

- https://github.com/PacktPublishing/Machine-Learning-for-Cybersecurity Cookbook/tree/master/Chapter05/IoT%20Device%20Type%20Identification%20Using%20Machine%20Learning. (URL accessed on 20 October 2024).

- S. B. Kotsiantis. (2007). Supervised Machine Learning: A Review of Classification Techniques. Informatica. 249-268.

- Grandini M, Bagli E, Visani G. (2020). Metrics for Multi-Class Classification: an Overview. arXiv:2008.05756. [CrossRef]

- Alenazi, M. and Mishra, S. (2024). Cyberatttack Detection and Classification in IIoT systems using XGBoost and Gaussian Naïve Bayes: A Comparative Study. Engineering, Technology & Applied Science Research. 14, 4 (Aug. 2024), 15074–15082. [CrossRef]

- Vujović Z.D. (2021). Classification Model Evaluation Metrics. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications (IJACSA). [CrossRef]

- Chekati A. Riahi M. Moussa F. (2020). Data Classification in Internet of Things for Smart Objects Framework. 28th International Conference on Software, Telecommunications and Computer Networks (SoftCOM 2020). [CrossRef]

- Wabang, K., Oky Dwi Nurhayati, & Farikhin. (2022). Application of The Naïve Bayes Classifier Algorithm to Classify Community Complaints. Jurnal RESTI (Rekayasa Sistem Dan Teknologi Informasi), 6(5), 872 - 876. [CrossRef]

| Gradient Boosting | Metrics Class | AUC | ACC | F1 | Precision | Recall | MCC |

| TV | 0.979 | 0.984 | 0.920 | 0.920 | 0.920 | 0.911 | |

| Baby monitor | 1.00 | 0.995 | 0.975 | 0.990 | 0.960 | 0.972 | |

| Lights | 0.926 | 0.909 | 0.556 | 0.543 | 0.570 | 0.506 | |

| Motion sensor | 0.991 | 0.988 | 0.941 | 0.931 | 0.950 | 0.934 | |

| Security camera | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Smoke detector | 0.997 | 0.996 | 0.980 | 0.990 | 0.970 | 0.978 | |

| socket | 0.920 | 0.906 | 0.530 | 0.530 | 0.530 | 0.478 | |

| Thermostat | 0.987 | 0.991 | 0.955 | 0.950 | 0.960 | 0.950 | |

| Watch | 0.991 | 0.988 | 0.941 | 0.931 | 0.950 | 0.927 | |

| Water sensor | 0.914 | 0.911 | 0.544 | 0.558 | 0.530 | 0.495 |

| Random Forest | Metrics Class | AUC | ACC | F1 | Precision | Recall | MCC |

| TV | 0.998 | 0.981 | 0.907 | 0.886 | 0.930 | 0.897 | |

| Baby monitor | 0.999 | 0.996 | 0.980 | 1.00 | 0.960 | 0.978 | |

| Lights | 0.936 | 0.901 | 0.500 | 0.505 | 0.560 | 0.475 | |

| Motion sensor | 0.984 | 0.994 | 0.960 | 0.990 | 0.950 | 0.966 | |

| Security camera | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Smoke detector | 0.995 | 0.997 | 0.985 | 0.990 | 0.980 | 0.983 | |

| socket | 0.912 | 0.899 | 0.498 | 0.495 | 0.500 | 0.441 | |

| Thermostat | 0.989 | 0.990 | 0.950 | 0.950 | 0.950 | 0.944 | |

| Watch | 0.999 | 0.987 | 0.935 | 0.939 | 0.930 | 0.927 | |

| Water sensor | 0.934 | 0.919 | 0.585 | 0.600 | 0.570 | 0.540 |

| Model | AUC | CA | F1 | Precision | Recall | MCC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | 0.997 | 0.981 | 0.905 | 0.901 | 0.910 | 0.895 |

| Gradient Boosting | 0.979 | 0.984 | 0.920 | 0.920 | 0.920 | 0.911 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).