Submitted:

05 February 2025

Posted:

06 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Signal Model

2.1. Sparse SAR Imaging Model

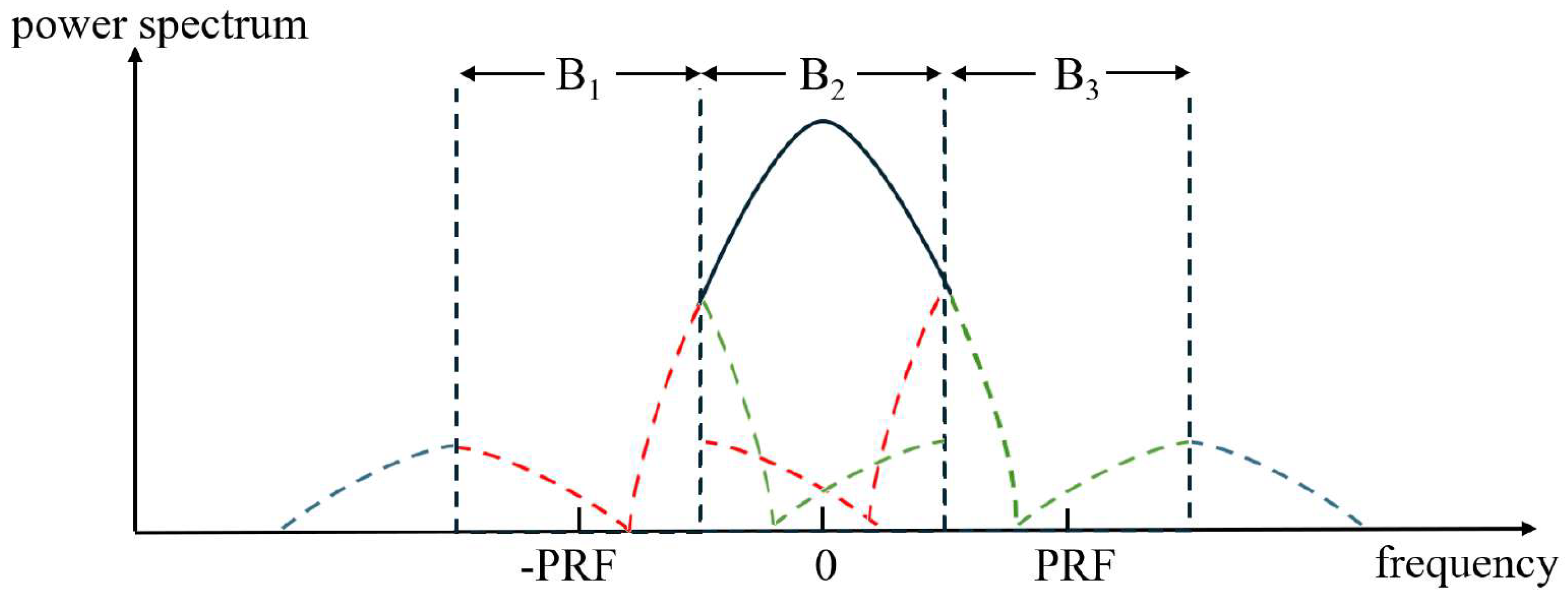

2.2. Azimuth Ambiguity Suppression Signal Model

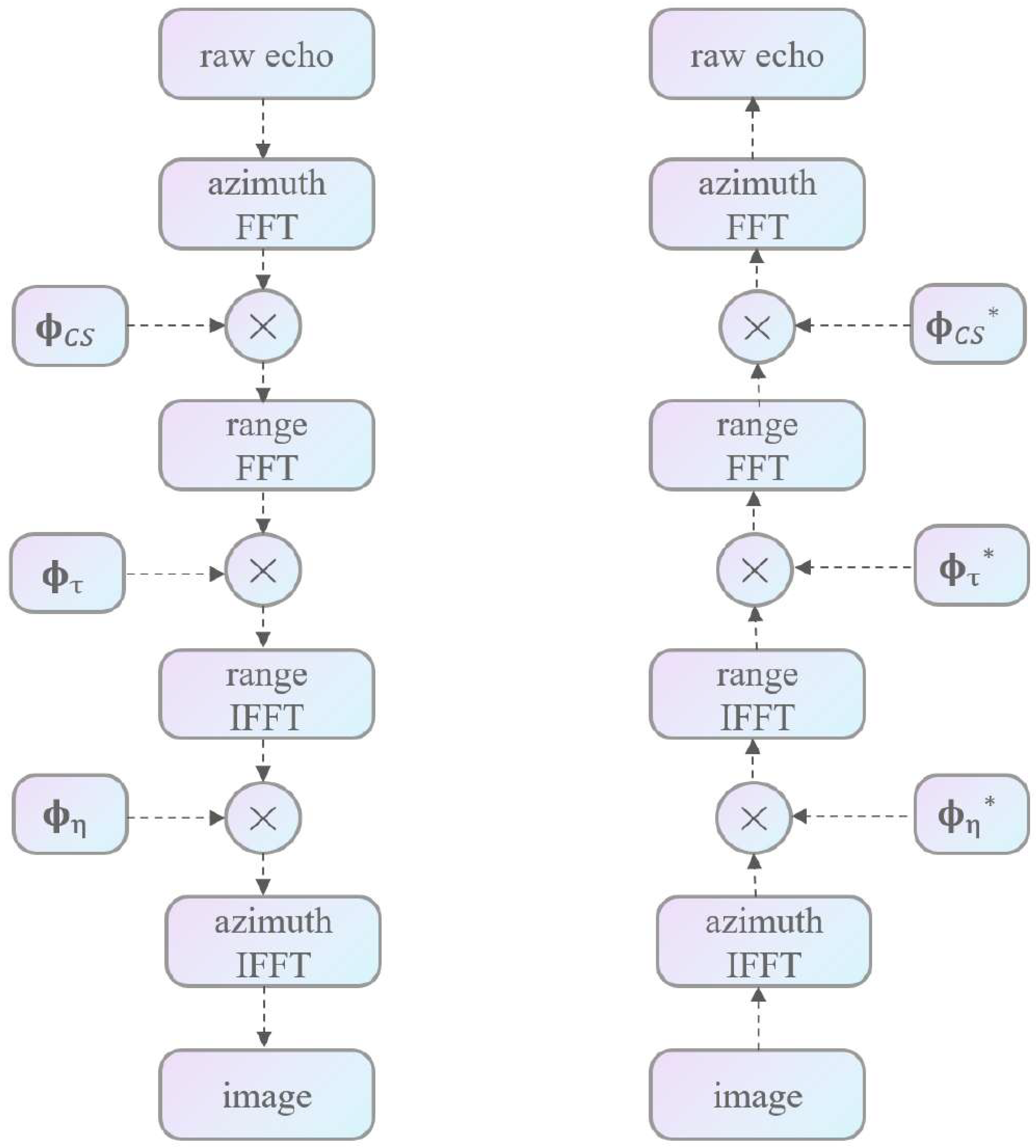

3. The Structure of the Imaging Network

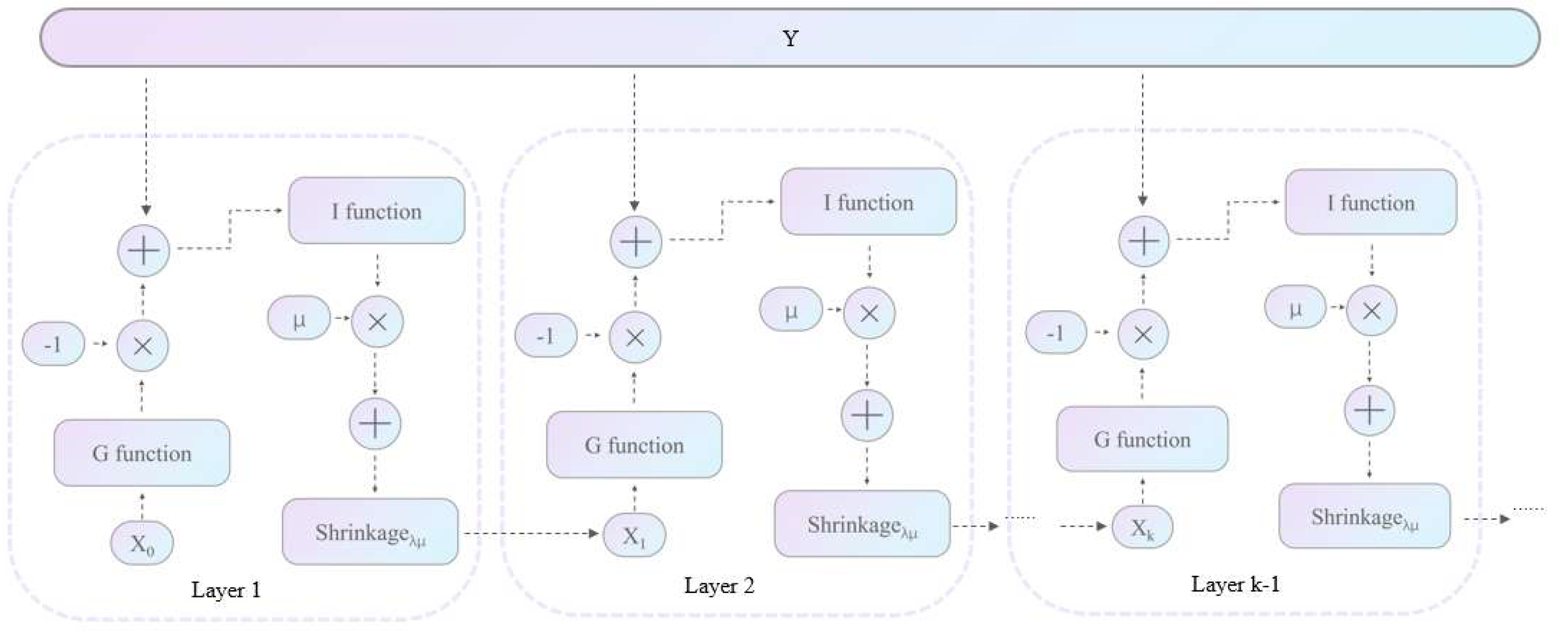

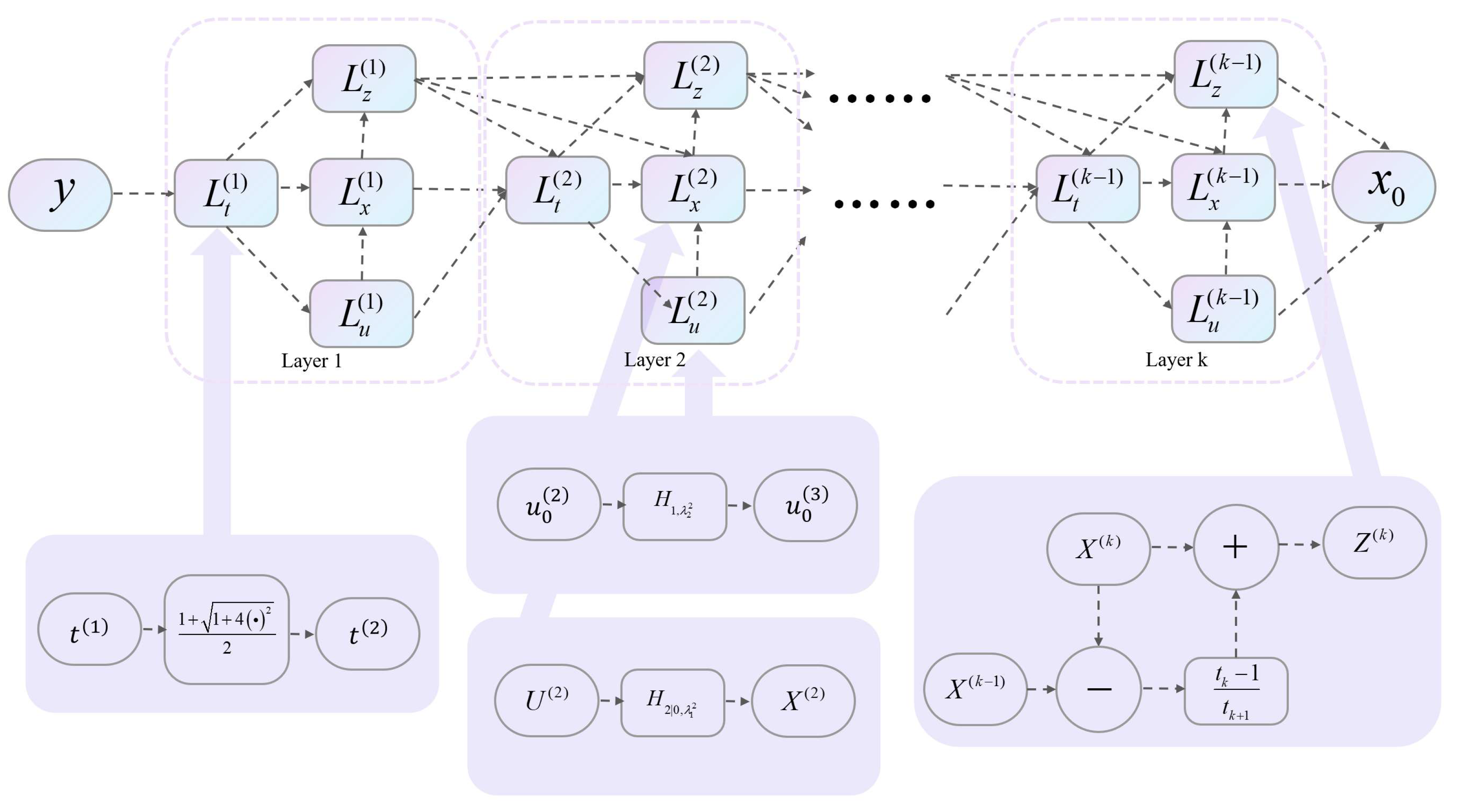

3.1. The Structure of Basic ISTA Network

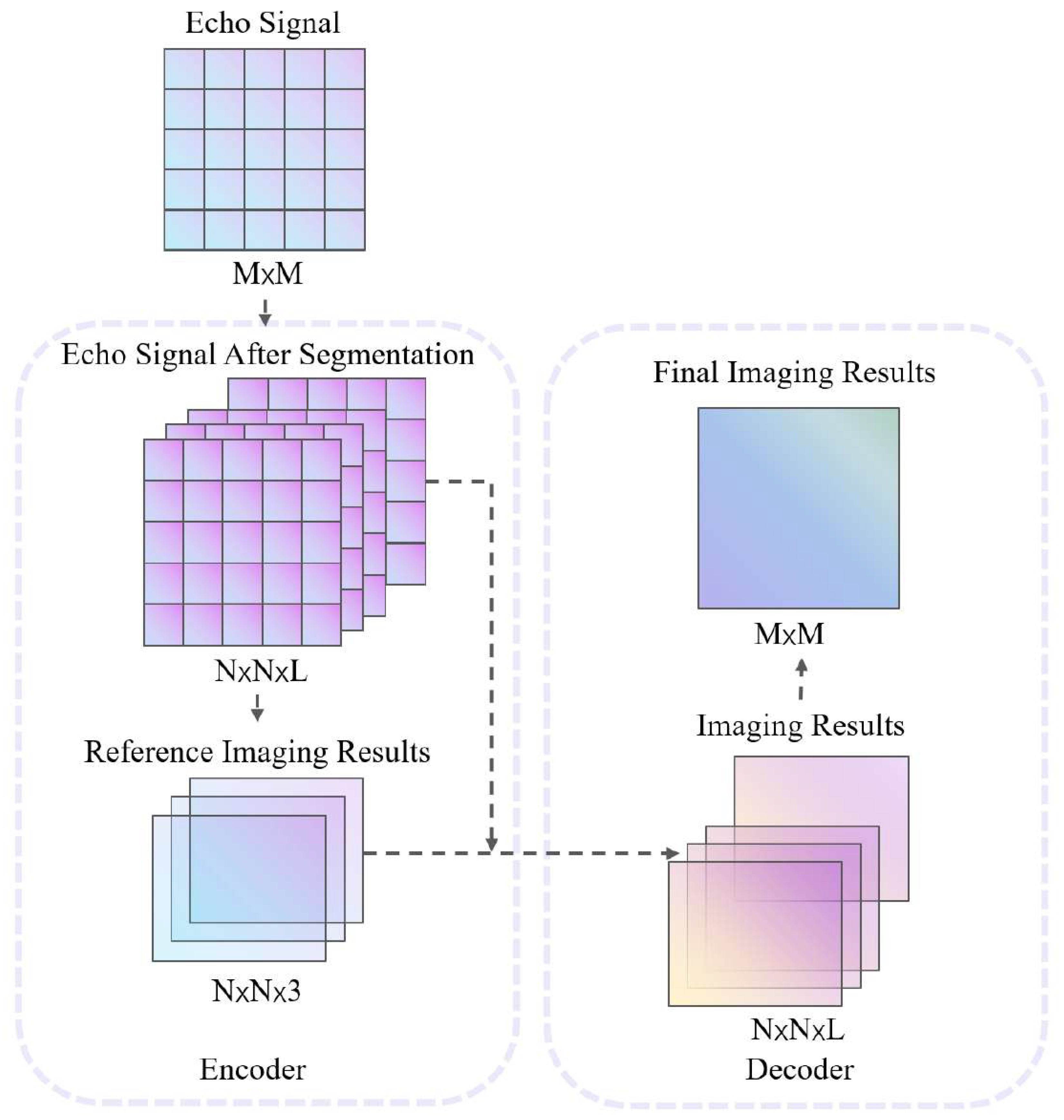

3.2. The Structure of Azimuth Ambiguity Suppression Network

| Algorithm 1: algorithm of azimuth ambiguity based sparse imaging |

|

3.3. The Training Process of the Azimuth Ambiguity Suppression Network

4. Experiments

4.1. Simulation Experiments

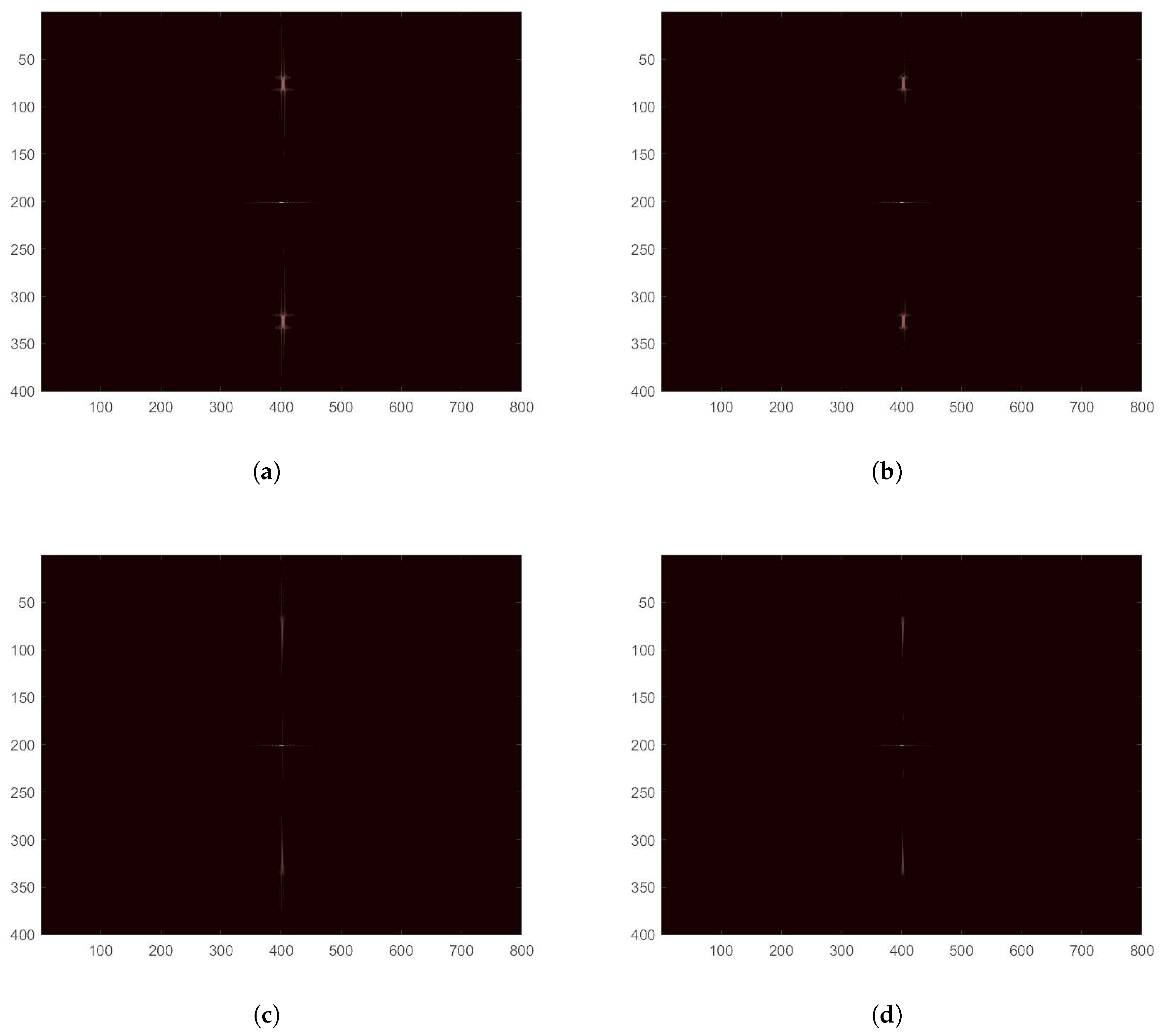

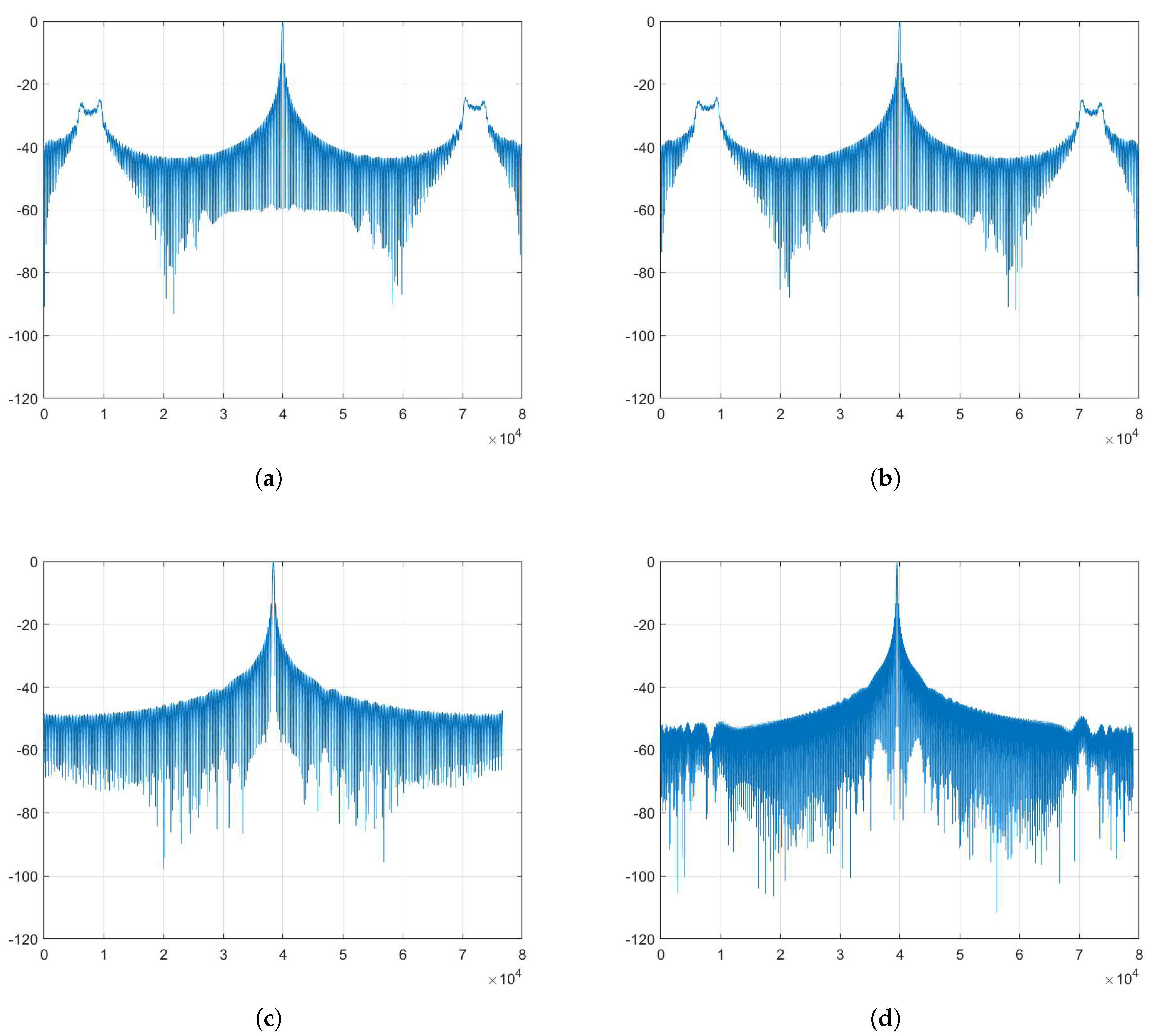

4.1.1. Point Target Imaging Experiment

4.1.2. Point Target Undersampling Imaging Experiment

4.2. Real Data Experiments

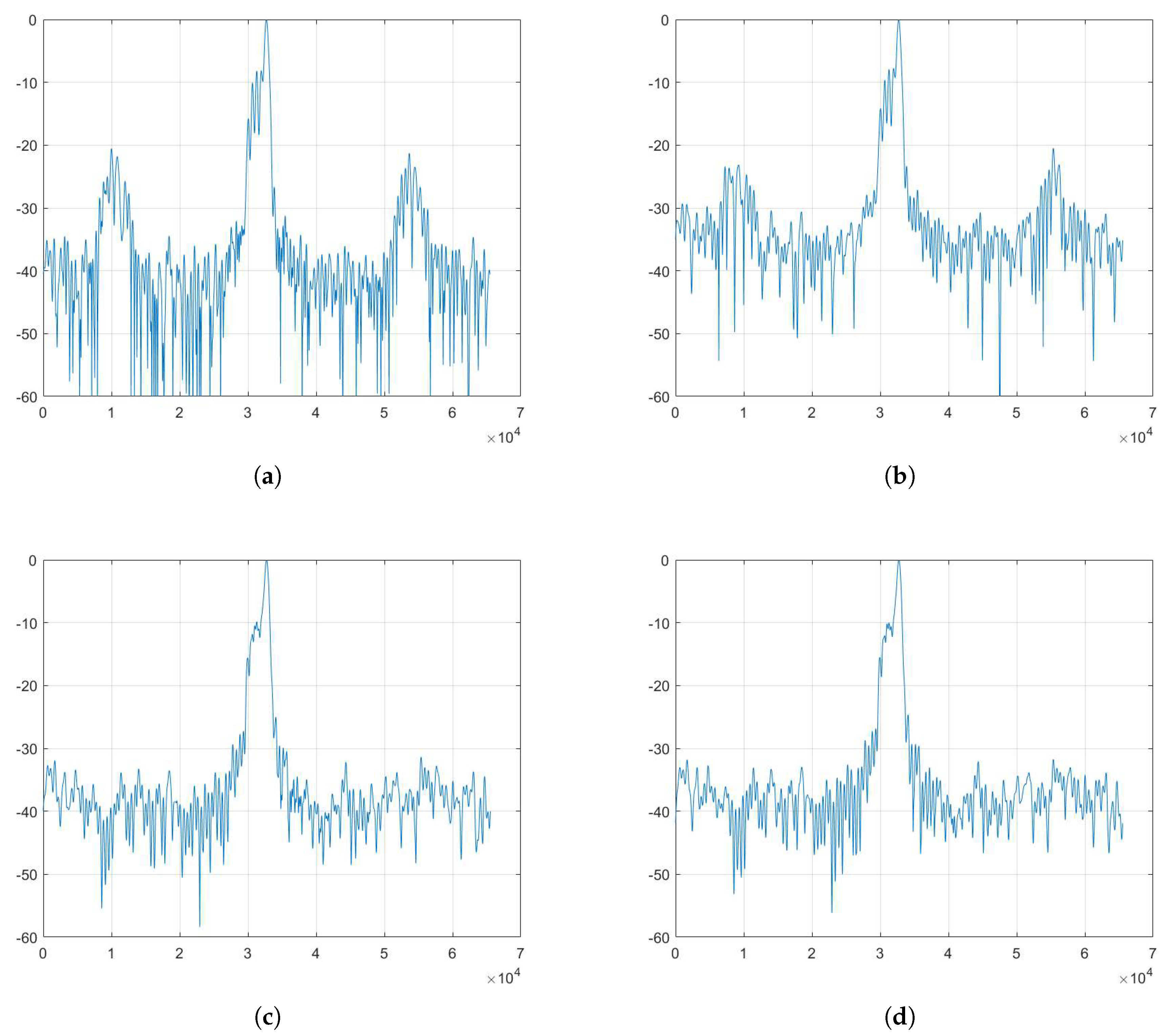

4.2.1. Real Data Imaging Experiment

4.2.2. Real Data Undersampling Image Experiment

4.2.3. Network Iteration Layer Experiment

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HRWS | high-resolution wide-swath |

| SAR | synthetic aperture radar |

| RCM | range cell migration |

| SAAS-Net | Self-supervised Azimuth Ambiguity Suppression Network |

| CS | chirp-scaling |

| PRF | pulse repetition frequency |

| ISTA | iterative shrinkage thresholding algorithm |

| FISTA | fast iterative shrinkage thresholding algorithm |

References

- Baraniuk, R.G. Compressive sensing [lecture notes]. IEEE signal processing magazine 2007, 24, 118–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candès, E.J.; Romberg, J.; Tao, T. Robust uncertainty principles: Exact signal reconstruction from highly incomplete frequency information. IEEE Transactions on information theory 2006, 52, 489–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, V.M.; Easley, G.R.; Healy, D.M.; Chellappa, R. Compressed synthetic aperture radar. IEEE Journal of selected topics in signal processing 2010, 4, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Zhang, Y. SAR image reconstruction from undersampled raw data using maximum a posteriori estimation. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2014, 8, 1651–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Liao, G.; Zhu, S.; Yang, X.; Zhang, X. SAR imaging with undersampled data via matrix completion. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 2014, 11, 1539–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Fang, J.; Xu, Z. Sparse SAR imaging based on L 1/2 regularization. Science China Information Sciences 2012, 55, 1755–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Duan, C.; Hu, W. Sparse representation based autofocusing technique for ISAR images. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2012, 51, 1826–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xing, M.; Qiu, C.W.; Li, J.; Bao, Z. Achieving higher resolution ISAR imaging with limited pulses via compressed sampling. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 2009, 6, 567–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, E.; Nannini, M.; Reigber, A. A data-adaptive compressed sensing approach to polarimetric SAR tomography of forested areas. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 2012, 10, 543–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, C.D.; Ertin, E.; Moses, R.L. Sparse signal methods for 3-D radar imaging. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Signal Processing 2010, 5, 408–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budillon, A.; Ferraioli, G.; Schirinzi, G. Localization performance of multiple scatterers in compressive sampling SAR tomography: Results on COSMO-SkyMed data. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2014, 7, 2902–2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, B.; Hong, W.; Wu, Y. Fast compressed sensing SAR imaging based on approximated observation. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2013, 7, 352–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Qiu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, W. MF-JMoDL-Net: A Sparse SAR Imaging Network for Undersampling Pattern Design towards Suppressed Azimuth Ambiguity. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, E.; Yonel, B.; Yazici, B. Deep learning for SAR image formation. In Proceedings of the Algorithms for Synthetic Aperture Radar Imagery XXIV. SPIE, Vol. 10201; 2017; pp. 11–21. [Google Scholar]

- Pu, W. Deep SAR imaging and motion compensation. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2021, 30, 2232–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.; Ni, J.; Liang, J.; Xiong, S.; Luo, Y. End-to-end SAR deep learning imaging method based on sparse optimization. Remote Sensing 2021, 13, 4429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wu, J.; Huo, W.; Jiang, R.; Li, Z.; Yang, J.; Li, H. Target-oriented SAR imaging for SCR improvement via deep MF-ADMM-Net. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2022, 60, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wu, J.; Huo, W.; Jiang, R.; Li, Z.; Yang, J.; Li, H. Target-oriented SAR imaging for SCR improvement via deep MF-ADMM-Net. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2022, 60, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregor, K.; LeCun, Y. Learning fast approximations of sparse coding. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 27th international conference on international conference on machine learning, 2010, pp.

- Wang, M.; Wei, S.; Liang, J.; Zeng, X.; Wang, C.; Shi, J.; Zhang, X. RMIST-Net: Joint range migration and sparse reconstruction network for 3-D mmW imaging. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2021, 60, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, E.; Yonel, B.; Yazici, B. Deep learning for SAR image formation. In Proceedings of the Algorithms for Synthetic Aperture Radar Imagery XXIV. SPIE, Vol. 10201; 2017; pp. 11–21. [Google Scholar]

- Yonel, B.; Mason, E.; Yazıcı, B. Deep learning for passive synthetic aperture radar. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Signal Processing 2017, 12, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, A. Suppressing the azimuth ambiguities in synthetic aperture radar images. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 1993, 31, 885–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Youming, W.; Ze, Y.; et al. A SAR image azimuth ambiguity suppression method based on compressed sensing restoration algorithm. J. Radar 2016, 5, 39–45. [Google Scholar]

- Bingchen, Z.; Chenglong, J.; Zhe, Z.; Jian, F.; Yao, Z.; Wen, H.; Yirong, W.; Zongben, X. Azimuth Ambiguity Suppression for SAR Imaging based on Group Sparse Reconstruction.

- Xu, G.; Xia, X.G.; Hong, W. Nonambiguous SAR image formation of maritime targets using weighted sparse approach. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2017, 56, 1454–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Martino, G.; Iodice, A.; Riccio, D.; Ruello, G. Filtering of azimuth ambiguity in stripmap synthetic aperture radar images. IEEE Journal of selected topics in applied earth observations and remote sensing 2014, 7, 3967–3978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Yu, Z.; Xiao, P.; Li, C. Azimuth ambiguity suppression based on minimum mean square error estimation. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS). IEEE; 2015; pp. 2425–2428. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Yu, Z.; Xiao, P.; Li, C. Suppression of azimuth ambiguities in spaceborne SAR images using spectral selection and extrapolation. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2018, 56, 6134–6147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| simulation parameters | value |

|---|---|

| Carrier Frequency/Hz | 1.2e8 |

| Equivalent Bandwidth/m | 1e8 |

| Radar Platform Movement Speed/m/s | 154 |

| SNR/dB | 30 |

| PRF/Hz | 7.2e7 |

| Range/m | 5000 |

| Method | PSNR(dB) | ISLR(dB) | AASR(dB) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CS-IST | -13.356 | -10.581 | -14.216 |

| CS-IST-AAS | -19.775 | -16.449 | -17.423 |

| ISTA-Net | -13.542 | -11.325 | -14.198 |

| AAS-Net | -20.194 | -17.232 | -18.017 |

| Sample rate | SNR(dB) | CS-IST | CS-IST-AAS | ISTA-Net | AAS-Net |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | -18.15 | -18.34 | -18.07 | -18.46* | |

| 90% | 10 | -18.68 | -19.32* | -18.99 | -19.08 |

| 5 | -19.24 | -19.95 | -18.97 | -20.23* | |

| 20 | -14.22 | -17.42 | -14.20 | -18.02* | |

| 70% | 10 | -15.75 | -17.94 | -14.68 | -18.27* |

| 5 | -16.08 | -18.27 | -16.33 | -18.35* | |

| 20 | -9.15 | -12.36 | -10.32 | -12.73* | |

| 30% | 10 | -10.21 | -12.84 | -10.83 | -13.02* |

| 5 | -10.32 | -13.21 | -11.07 | -13.29* |

| Method | AASR(dB) | Time(s)) |

|---|---|---|

| CS-IST | -9.56 | 71.71 |

| CS-IST-AAS | -14.63 | 128.28 |

| ISTA-Net | -11.34 | 0.13 |

| Proposed method | -15.01 | 0.14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).