1. Introduction

A suboptimal diet contributes to approximately half of all cardiometabolic deaths in the US [

1]. Based on the US Burden of Disease Collaborators' analysis of 17 leading risk factors for mortality—including smoking tobacco, an unhealthy diet contributes to the most deaths [

2]. In contrast, healthy eating patterns rich in fruits and vegetables promote longevity [

3,

4,

5]. Many factors are responsible for poor dietary habits, but frequent eating out and infrequent cooking at home are particularly concerning. As of 2010, Americans spend more on food away from home than groceries [

6]. Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) estimates that 16% of the average American's daily calories come from fast foods [

6]. Foods away from home are typically high in sodium, calories, trans fats, and ultra-processed ingredients [

6]. Thus, eating away from home can decrease dietary quality and increase body mass index [

7,

8]. As eating out has become more popular, home cooking has simultaneously declined [

9]. The downturn in cooking at home is unfortunate because home cooking can improve dietary quality and increase adherence to US nutritional guidelines [

10,

11].

Culinary Medicine (CM) seeks to decrease the burden of diet-related illnesses through blending nutrition, culinary arts, disease prevention, public health, and evidenced-based medicine [

12,

13,

14,

15]. To promote healthy eating, CM emphasizes food and health literacy [

16,

17,

18]. Despite the lack of a standardized definition, CM can educate health practitioners, students, and patients about the links between dietary behaviors, cooking techniques, and disease [

19,

20,

21]. Food safety, meal preparation, grocery shopping, and food storage are common topics in CM [

14,

22,

23]. Cooking classes and demonstrations are essential components of CM.

We argue that analyzing the gut microbiome and metabolome can complement CM interventions due to the profound link between diet and the gut microbiome and metabolome. Further, short-term CM interventions may benefit from fecal analyses since diet can rapidly alter gut bacteria. We also describe the feasibility of fecal microbiome and metabolomic testing in CM with our pilot experience since hygiene and embarrassment have been previously portrayed as barriers to stool collection [

24].

2. Culinary Medicine’s Evidence and Limitations

Evidence for the value of CM exists. Multiple studies have demonstrated the effectiveness and limitations of CM despite its relative nascency [

10,

15,

25]. A 2021 meta-analysis of 33 CM interventions by Asher et al. highlighted the effect of CM on dietary behaviors. Most of the studies had a pre-post design—seven were randomized clinical trials (RCT). The studies had varying program lengths, ranging from 1 day to 2 years. Reported measures included changes in culinary knowledge, motivation, self-efficacy for healthier cooking, and dietary intake. The seven RCTs showed CM's benefits for improving dietary patterns, cooking confidence, culinary knowledge, and body mass index [

15]. Similarly, a recent scoping review of the effect of CM interventions on medical students indicated improvements in their self-efficacy in providing nutritional counseling and their culinary knowledge [

26].

Meta-analyses of CM have noted several limitations of commonly measured outcomes [

10,

15,

25]. One notable limitation is a shortage of quantitative measurements. Researchers seldom measure how CM affects anthropomorphic variables or metabolic parameters such as hemoglobin A1c, blood pressure, homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), or lipid levels. When CM studies assess quantitative variables, other factors such as genetics, health status, sleep, and physical activity may act as confounders. Additionally, many quantitative clinical variables change slowly and may require multiple assessments over months or years. Furthermore, CM interventions intending to prevent disease may not benefit from using these clinical markers since they may be normal in a healthy population.

Moreover, many CM interventions rely on self-reports of dietary intake, such as Food Frequency Questionnaires and 24-hour dietary recall. Despite their low cost and ease of use, these survey tools have limitations. Social desirability, errors in recall, and underreporting can compromise the validity of both tools [

27,

28,

29]. In CM research, these inaccuracies can cause false conclusions and misinterpretations of results. Using biomarkers of dietary intake and nutritional status can improve the quantitative and dietary assessment of CM.

Nutritional biomarkers are measurable characteristics of dietary intake or nutritional status found in biological samples such as urine, plasma, saliva, hair, or stool [

30]. The availability of dietary biomarkers stems from the recent rise in omics technologies—metabolomics, genomics, proteomics, transcriptomics, and microbiomics [

31,

32,

33]. In CM, dietary biomarkers may directly suggest nutrient intake or indirectly reflect the effects of digestion, absorption, and metabolism on consumed nutrients. Assessing dietary metabolites is attractive in CM because dietary intake alone does not reflect the complex processes involved in nutrition, such as nutrient-nutrient interactions, bioavailability, and metabolism. Pico et al. provide an excellent review of nutritional biomarkers [

34]. Likewise, Liang et al. thoroughly appraise the use of nutritional biomarkers in RCTs [

30].

3. Understanding the Gut Microbiome and its Relationships with Health and Disease

The gut microbiome is a complex ecosystem of symbiotic microorganisms housed within the gastrointestinal tract that influences health and disease through microbe-host interactions [

35]. Almost 1000 different species of bacteria reside in the gut [

36]. Bacteria account for approximately 60% of the dry weight of human feces [

37]. The microbiome encompasses not only the gastrointestinal tract's bacteria (microbiota), but also their bacterial genomes and products [

38]. Researchers estimate that the gut microbiome contains 150 times more genes than the human genome [

36]. This wide array of genetic information translates to a vast catalog of bacterial products, including metabolites, interacting with the human body. Microbial metabolites include vitamins, short-chain fatty acids, bile acids, neurotransmitters, lipids, choline derivatives, and gases. Evidence shows that these metabolites can play a causal or indirect role in various disease states. These include noncommunicable diseases associated with diet such as obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer [

39]. As such, understanding how diet manipulates the gut microbiome and metabolome may have value in treating and preventing disease [

24].

4. The Influence of Diet on the Gut Microbiota Composition

Bacteria colonize the gut during birth. The mode of delivery - Cesarean or vaginal - impacts this initial microbiota composition [

40]. After birth, the primary determinants of gut microbiota are age, host genetics, and environmental factors such as antibiotic exposure, smoking, and diet [

41]. The influence of diet on the microbiota is apparent early in life, as breast milk and formula affect bacterial diversity differently [

42]. Similarly, a diet rich in fruits and vegetables affects the gut microbiome differently than one rich in protein and ultra-processed foods like the Standard American Diet [

43]. The American Gut Project analyzed lifestyle data and stool samples from over 10,000 participants. Their analysis demonstrated that consuming foods from plants diversifies the gut microbiota. They found an association between consuming at least 30 plants per week with the most diverse gut microbiota [

44].

In contrast, dietary patterns rich in ultra-processed food may decrease diversity within the gut microbiota. For example, Manor et al.'s examination of lifestyle factors and gut microbiota revealed a negative association between increased consumption of sugary beverages and microbial diversity [

45]. Likewise, in a systemic review, Marit Zinöcker and Inge Lindseth highlighted the detrimental impact of ultra-processed foods ultra-processed foods on the microbiota and host physiology. Specifically, they note concerns with emulsifiers, artificial sweeteners, and acellular nutrients—isolated nutrients free from the framework of plant or animal cells [

46]. Hence, evaluating the gut microbiota may help assess reductions in ultra-processed food consumption, an essential target for CM interventions.

5. The Effect of Diet on the Gut Metabolome and the Gut Metabolome’s Role in Disease

Diet can also affect the gut metabolome, a function of the metabolic activity of bacteria within the gut. In a landmark study evaluating the impact of diet on colon cancer risk, O'keefe et al. performed a cross-over study involving African Americans and black, rural South Africans. The participants exchanged their traditional diets, a fiber-rich South African diet and a fiber-poor, protein-heavy American diet. An analysis of the participants’ stool metabolites revealed the African diet reduced secondary bile acids, a metabolite, by 70%, whereas the American diet increased them by 400% [

47]. Secondary bile acids within the colon may contribute to colonic inflammation and colon cancer [

48].

Aside from cancer, fecal metabolites may reflect a risk for cardiometabolic diseases [

49]. Fecal Trimethylamine (TMA) is one of several metabolites implicated in cardiovascular disease. The gut microbiota metabolizes choline and carnitine, nutrients commonly found in eggs and meat, into TMA. In turn, the liver metabolizes TMA to trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO), a plasma metabolite associated with atherosclerosis [

50]. Besides TMA, Deng et al. analyzed fecal metabolites from 1007 participants. They found that 12 other fecal metabolites besides TMA were associated with cardiometabolic conditions, including type 2 diabetes, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and obesity. Their study also revealed that butyric acid, a short-chain fatty acid (SCFA), was inversely associated with type 2 diabetes [

51]. SCFAs stem from microbial fermentation of dietary fiber and may offer protection against diabetes and obesity [

52].

Additionally, the metabolites found within the gut metabolome may correspond to the intake of specific nutrients. Shinn et al. identified metabolites that predict intake by using machine learning. They specifically assessed for metabolites corresponding to the intake of almonds, broccoli, avocado, walnuts, barley, and whole-grain oats. The accuracy of their predictive models ranged from 47% to 89% [

53].

Diet-associated changes in the gut microbiota and metabolome can occur rapidly. In a controlled feeding study, Wu et al. showed detectable changes in the gut microbiome within 24 hours of dietary modification [

54]. Researchers also compared the effects of four days of fast-food or a Mediterranean diet on the microbiota and metabolite production. Their study showed that four days of either diet was enough to alter the gut microbiota composition and metabolites [

55].

The speed at which diet can alter the microbiota is another reason supporting its use in CM. Again, CM studies of days or weeks in duration may be too brief to impact clinical and anthropomorphic markers such as BMI and hemoglobin A1C.

6. Feasibility: Our Pilot Experience with CM and Gut Microbiome Evaluation

In 2022, we began providing free cooking classes and nutrition education in under-resourced neighborhoods on Chicago’s South and West sides. We developed and implemented a 6-week healthy cooking curriculum called Good Food is Good Medicine (GFGM). A chef and a chef-trained physician created the curriculum by utilizing their expertise and both the Health Belief Model and the Socio-ecological model as theoretical frameworks. The curriculum was also culturally tailored to meet the needs of the predominantly non-Black Hispanic and Black non-Hispanic populations residing in our service areas. We utilized surveys and focus groups to tailor the curriculum to meet our participants' needs.

We delivered the curriculum in partnership with the non-profit organization, the Good Food Catalyst. The program occurred in several teaching kitchens in under-resourced neighborhoods in Chicago, including Garfield Park, Englewood, Little Village, and North Lawndale. To demonstrate the program's real-world effectiveness, we analyzed the stool metabolome of 18 participants from the Garfield Park site.

After we explained the gut microbiome's roles in health and disease in a focus group setting, the participants were eager to participate. Using whipped cream as a model, we demonstrated how to collect stools with our collection kit in the teaching kitchen. We collected stool samples at weeks 1, 3, and 6. To collect the stool in a sanitary fashion, participants did not bring stool samples into the building housing the teaching kitchen. Hand-washing before and after stool drop-off was mandatory.

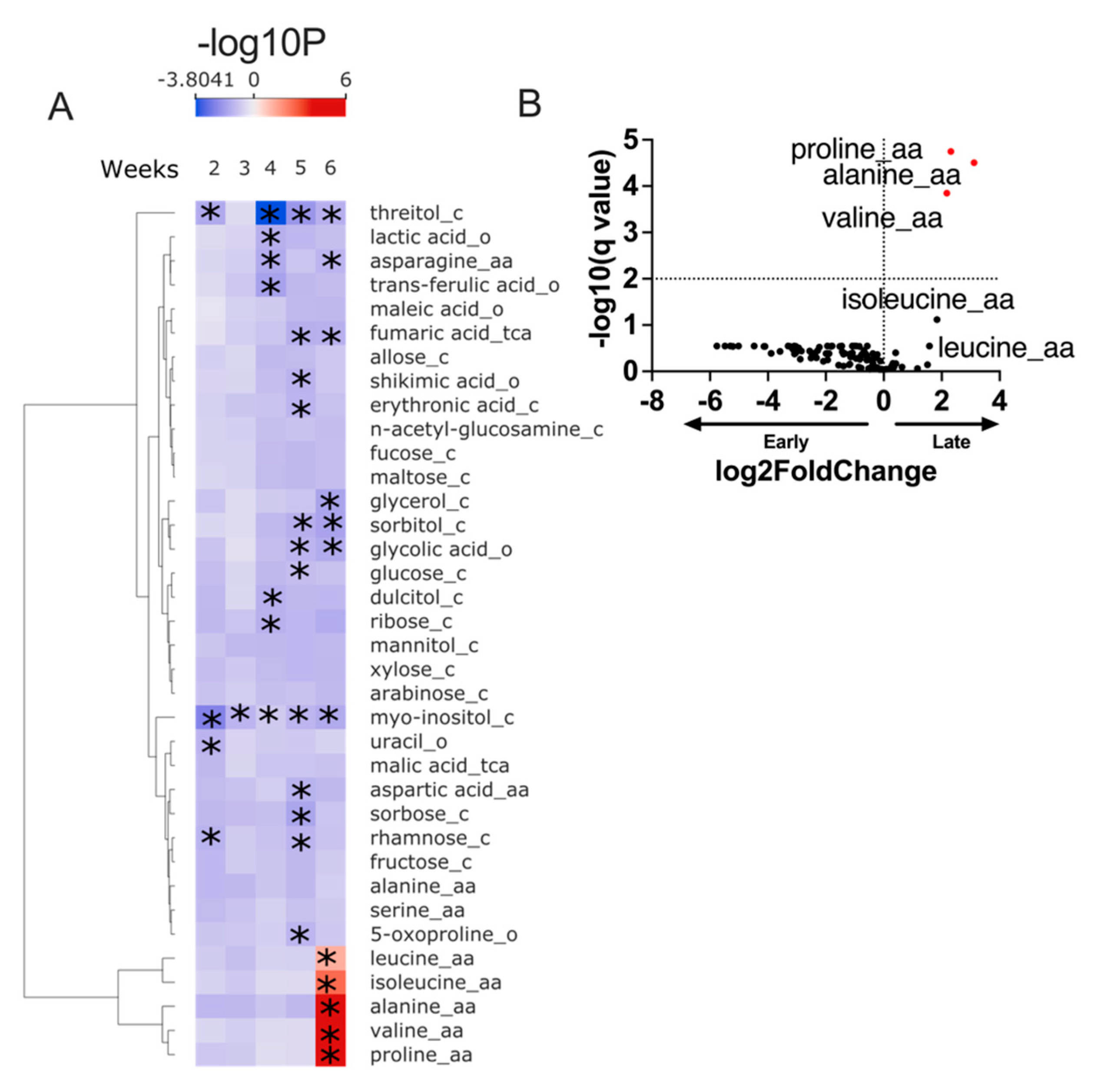

Our preliminary evaluation of fecal metabolites suggests our CM intervention leads to detectable changes in the fecal metabolome (

Figure 1).

7. Conclusions

Diet is a well-established risk factor for chronic disease. CM is a practical, evidenced-based strategy for facilitating healthier eating. Incorporating biomarkers of diet and nutritional status could help with understanding the effectiveness of CM interventions. Food is a powerful determinant of the gut microbiome's and metabolome's composition and function. As such, there is value in investigating the gut microbiome and metabolome before and after CM interventions.

Our findings demonstrate the feasibility of collecting stool samples for metabolomic testing in a CM intervention targeting under-resourced communities. We also showed that our six-week curriculum leads to detectable dietary changes by analyzing the gut metabolome. Further studies are needed to correlate metabolomic changes with changes in dietary intake.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.M. and E.C.; data curation, O.D.; writing—original draft preparation, T.W. and E.M.; writing—review and editing, S.T., E.L, S.L., and T.W..; supervision, E.M and E.C..; project administration, J.W. and E.L.; funding acquisition, E.M. and E.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.".

Funding

This research was funded by the Gastrointestinal Research Foundation (GIRF).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of University of Chicago, Biological Sciences Division (protocol 15573a).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Shelby Parchman for administrative support, Joan and David Evans for philanthropic support, the Gastrointestinal Research Foundation (GIRF) and the Digestive Diseases Research Core Center.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

| TLA |

Three letter acronym |

| LD |

Linear dichroism |

References

- Micha, R.; Peñalvo, J.L.; Cudhea, F.; Imamura, F.; Rehm, C.D.; Mozaffarian, D. Association Between Dietary Factors and Mortality From Heart Disease, Stroke, and Type 2 Diabetes in the United States. JAMA 2017, 317, 912–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collaborators, T.U.B. of D.; Mokdad, A.H.; Ballestros, K.; Echko, M.; Glenn, S.; Olsen, H.E.; Mullany, E.; Lee, A.; Khan, A.R.; Ahmadi, A.; et al. The State of US Health, 1990-2016: Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Among US States. Jama 2018, 319, 1444–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Sonderman, J.; Buchowski, M.S.; McLaughlin, J.K.; Shu, X.-O.; Steinwandel, M.; Signorello, L.B.; Zhang, X.; Hargreaves, M.K.; Blot, W.J.; et al. Healthy Eating and Risks of Total and Cause-Specific Death among Low-Income Populations of African-Americans and Other Adults in the Southeastern United States: A Prospective Cohort Study. Plos Med 2015, 12, e1001830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Z.; Wang, F.; Li, Y.; Baden, M.Y.; Bhupathiraju, S.N.; Wang, D.D.; Sun, Q.; Rexrode, K.M.; Rimm, E.B.; Qi, L.; et al. Healthy Eating Patterns and Risk of Total and Cause-Specific Mortality. JAMA Intern. Med. 2023, 183, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Pan, A.; Wang, D.D.; Liu, X.; Dhana, K.; Franco, O.H.; Kaptoge, S.; Angelantonio, E.D.; Stampfer, M.; Willett, W.C.; et al. Impact of Healthy Lifestyle Factors on Life Expectancies in the US Population. Circulation 2018, 138, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saksena, M.J.; Okrent, A.M.; Anekwe, T.D.; Cho, C.; Dicken, C.; Effland, A.; Elitzak, H.; Guthrie, J.; Hamrick, K.S.; Hyman, J.; et al. America’s Eating Habits: Food Away From Home; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nagao-Sato, S.; Reicks, M. Food Away from Home Frequency, Diet Quality, and Health: Cross-Sectional Analysis of NHANES Data 2011–2018. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seguin, R.A.; Aggarwal, A.; Vermeylen, F.; Drewnowski, A. Consumption Frequency of Foods Away from Home Linked with Higher Body Mass Index and Lower Fruit and Vegetable Intake among Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Environ. Public Heal. 2016, 2016, 3074241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, L.P.; Ng, S.W.; Popkin, B.M. Trends in US Home Food Preparation and Consumption: Analysis of National Nutrition Surveys and Time Use Studies from 1965-1966 to 2007-2008. Nutr J 2013, 12, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reicks, M.; Kocher, M.; Reeder, J. Impact of Cooking and Home Food Preparation Interventions Among Adults: A Systematic Review (2011–2016). J Nutr Educ Behav 2018, 50, 148–172.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, S.; Brown, H.; Wrieden, W.; White, M.; Adams, J. Frequency of Eating Home Cooked Meals and Potential Benefits for Diet and Health: Cross-Sectional Analysis of a Population-Based Cohort Study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, K.; Polak, R. Culinary Medicine: Paving the Way to Health Through Our Forks. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2019, 14, 51–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puma, J.L. Culinary Medicine and Nature: Foods That Work Together. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2020, 14, 143–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puma, J.L. What Is Culinary Medicine and What Does It Do? Popul Health Manag 2016, 19, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asher, R.C.; Shrewsbury, V.A.; Bucher, T.; Collins, C.E. Culinary Medicine and Culinary Nutrition Education for Individuals with the Capacity to Influence Health Related Behaviour Change: A Scoping Review. J Hum Nutr Diet 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truman, E.; Lane, D.; Elliott, C. Defining Food Literacy: A Scoping Review. Appetite 2017, 116, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cullen, T.; Hatch, J.; Martin, W.; Higgins, J.W.; Sheppard, R. Food Literacy: Definition and Framework for Action. Can. J. Diet. Pr. Res. 2015, 76, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wang, D.; Liu, C.; Jiang, J.; Wang, X.; Chen, H.; Ju, X.; Zhang, X. What Is the Meaning of Health Literacy? A Systematic Review and Qualitative Synthesis. Fam. Med. Community Heal. 2020, 8, e000351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polak, R.; Phillips, E.M.; Nordgren, J.; Puma, J.L.; Barba, J.L.; Cucuzzella, M.; Graham, R.; Harlan, T.S.; Burg, T.; Eisenberg, D. Health-Related Culinary Education: A Summary of Representative Emerging Programs for Health Professionals and Patients. Glob Adv Health Med 2016, 5, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ring, M.; Cheung, E.; Mahadevan, R.; Folkens, S.; Edens, N. Cooking Up Health: A Novel Culinary Medicine and Service Learning Elective for Health Professional Students. J Altern Complementary Medicine 2019, 25, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothman, J.M.; Bilici, N.; Mergler, B.; Schumacher, R.; Mataraza-Desmond, T.; Booth, M.; Olshan, M.; Bailey, M.; Mascarenhas, M.; Duffy, W.; et al. A Culinary Medicine Elective for Clinically Experienced Medical Students: A Pilot Study. J Altern Complementary Medicine 2020, 26, 636–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B. , H.I.; Evert, A.; Fleming, A.; Gaudiani, L.M.; Guggenmos, K.J.; Kaufer, D.I.; McGill, J.B.; Verderese, C.A.; Martinez, J. Culinary Medicine: Advancing a Framework for Healthier Eating to Improve Chronic Disease Management and Prevention. Clin. Ther. 2019, 41, 2184–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asher, R.C.; Jakstas, T.; Lavelle, F.; Wolfson, J.A.; Rose, A.; Bucher, T.; Dean, M.; Duncanson, K.; Horst, K. van der; Schonberg, S.; et al. Development of the Cook-EdTM Matrix to Guide Food and Cooking Skill Selection in Culinary Education Programs That Target Diet Quality and Health. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lecky, D.M.; Hawking, M.K.D.; McNulty, C.A.M.; group, E. steering Patients’ Perspectives on Providing a Stool Sample to Their GP: A Qualitative Study. Br. J. Gen. Pr. 2014, 64, e684–e693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, B.; Thompson, W.G.; Almasri, J.; Wang, Z.; Lakis, S.; Prokop, L.J.; Hensrud, D.D.; Frie, K.S.; Wirtz, M.J.; Murad, A.L.; et al. The Effect of Culinary Interventions (Cooking Classes) on Dietary Intake and Behavioral Change: A Systematic Review and Evidence Map. Bmc Nutrition 2019, 5, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, J.; Atamanchuk, L.; Rao, T.; Sato, K.; Crowley, J.; Ball, L. Exploring Culinary Medicine as a Promising Method of Nutritional Education in Medical School: A Scoping Review. BMC Méd. Educ. 2022, 22, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HEBERT, J.R.; CLEMOW, L.; PBERT, L.; OCKENE, I.S.; OCKENE, J.K. Social Desirability Bias in Dietary Self-Report May Compromise the Validity of Dietary Intake Measures. Int. J. Epidemiology 1995, 24, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, N.; Ejima, K.; Zoh, R.S.; Brown, A.W. Bias in Nutrition-Health Associations Is Not Eliminated by Excluding Extreme Reporters in Empirical or Simulation Studies. eLife 2023, 12, e83616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravelli, M.N.; Schoeller, D.A. Traditional Self-Reported Dietary Instruments Are Prone to Inaccuracies and New Approaches Are Needed. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Nasir, R.F.; Bell-Anderson, K.S.; Toniutti, C.A.; O’Leary, F.M.; Skilton, M.R. Biomarkers of Dietary Patterns: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutr. Rev. 2022, 80, 1856–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rist, M.J.; Wenzel, U.; Daniel, H. Nutrition and Food Science Go Genomic. Trends Biotechnol 2006, 24, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, H.; Brennan, L. Metabolomics as a Tool in the Identification of Dietary Biomarkers. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2017, 76, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, X.; Shen, L. Advances and Trends in Omics Technology Development. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 911861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picó, C.; Serra, F.; Rodríguez, A.M.; Keijer, J.; Palou, A. Biomarkers of Nutrition and Health: New Tools for New Approaches. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinross, J.M.; Darzi, A.W.; Nicholson, J.K. Gut Microbiome-Host Interactions in Health and Disease. Genome Med. 2011, 3, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, B.; Wang, X.; Li, L. Human Gut Microbiome: The Second Genome of Human Body. Protein Cell 2010, 1, 718–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomaa, E.Z. Human Gut Microbiota/Microbiome in Health and Diseases: A Review. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 2020, 113, 2019–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, G.; Rybakova, D.; Fischer, D.; Cernava, T.; Vergès, M.-C.C.; Charles, T.; Chen, X.; Cocolin, L.; Eversole, K.; Corral, G.H.; et al. Microbiome Definition Re-Visited: Old Concepts and New Challenges. Microbiome 2020, 8, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Tan, Y.; Cheng, H.; Zhang, D.; Feng, W.; Peng, C. Functions of Gut Microbiota Metabolites, Current Status and Future Perspectives. Aging Dis. 2022, 13, 1106–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominguez-Bello, M.G.; Costello, E.K.; Contreras, M.; Magris, M.; Hidalgo, G.; Fierer, N.; Knight, R. Delivery Mode Shapes the Acquisition and Structure of the Initial Microbiota across Multiple Body Habitats in Newborns. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2010, 107, 11971–11975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Wang, X.; Li, L. Human Gut Microbiome: The Second Genome of Human Body. Protein Cell 2010, 1, 718–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, A.L.; Monteagudo-Mera, A.; Cadenas, M.B.; Lampl, M.L.; Azcarate-Peril, M.A. Milk- and Solid-Feeding Practices and Daycare Attendance Are Associated with Differences in Bacterial Diversity, Predominant Communities, and Metabolic and Immune Function of the Infant Gut Microbiome. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2015, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perler, B.K.; Friedman, E.S.; Wu, G.D. The Role of the Gut Microbiota in the Relationship Between Diet and Human Health. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2022, 85, 449–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, D.; Hyde, E.; Debelius, J.W.; Morton, J.T.; Gonzalez, A.; Ackermann, G.; Aksenov, A.A.; Behsaz, B.; Brennan, C.; Chen, Y.; et al. American Gut: An Open Platform for Citizen Science Microbiome Research. mSystems 2018, 3, e00031–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manor, O.; Dai, C.L.; Kornilov, S.A.; Smith, B.; Price, N.D.; Lovejoy, J.C.; Gibbons, S.M.; Magis, A.T. Health and Disease Markers Correlate with Gut Microbiome Composition across Thousands of People. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinöcker, M.K.; Lindseth, I.A. The Western Diet–Microbiome-Host Interaction and Its Role in Metabolic Disease. Nutrients 2018, 10, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keefe, S.J.D.; Li, J.V.; Lahti, L.; Ou, J.; Carbonero, F.; Mohammed, K.; Posma, J.M.; Kinross, J.; Wahl, E.; Ruder, E.; et al. Fat, Fibre and Cancer Risk in African Americans and Rural Africans. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Umar, S.; Rust, B.; Lazarova, D.; Bordonaro, M. Secondary Bile Acids and Short Chain Fatty Acids in the Colon: A Focus on Colonic Microbiome, Cell Proliferation, Inflammation, and Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agus, A.; Clément, K.; Sokol, H. Gut Microbiota-Derived Metabolites as Central Regulators in Metabolic Disorders. Gut 2021, 70, 1174–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Dai, M. Trimethylamine N-Oxide Generated by the Gut Microbiota Is Associated with Vascular Inflammation: New Insights into Atherosclerosis. Mediat. Inflamm. 2020, 2020, 4634172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, K.; Xu, J.; Shen, L.; Zhao, H.; Gou, W.; Xu, F.; Fu, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Shuai, M.; Li, B.; et al. Comparison of Fecal and Blood Metabolome Reveals Inconsistent Associations of the Gut Microbiota with Cardiometabolic Diseases. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaak, E.E.; Canfora, E.E.; Theis, S.; Frost, G.; Groen, A.K.; Mithieux, G.; Nauta, A.; Scott, K.; Stahl, B.; Harsselaar, J. van; et al. Short Chain Fatty Acids in Human Gut and Metabolic Health. Benef. Microbes 2020, 11, 411–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinn, L.M.; Mansharamani, A.; Baer, D.J.; Novotny, J.A.; Charron, C.S.; Khan, N.A.; Zhu, R.; Holscher, H.D. Fecal Metabolites as Biomarkers for Predicting Food Intake by Healthy Adults. J. Nutr. 2022, 152, 2956–2965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, G.D.; Chen, J.; Hoffmann, C.; Bittinger, K.; Chen, Y.-Y.; Keilbaugh, S.A.; Bewtra, M.; Knights, D.; Walters, W.A.; Knight, R.; et al. Linking Long-Term Dietary Patterns with Gut Microbial Enterotypes. Science 2011, 334, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, C.; Sawrey-Kubicek, L.; Beals, E.; Rhodes, C.H.; Houts, H.E.; Sacchi, R.; Zivkovic, A.M. Human Gut Microbiome Composition and Tryptophan Metabolites Were Changed Differently by Fast Food and Mediterranean Diet in 4 Days: A Pilot Study. Nutr. Res. 2020, 77, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).