Submitted:

27 January 2025

Posted:

28 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Development of a custom multimodal methodology: This study introduces a tailored methodology for integrating multimodal data—text, images, and tabular representations—in materials science. This methodology includes unique workflows for data creation, alignment, and representation, specifically addressing challenges associated with multimodal datasets.

- Utilization of the Alexandria dataset: By leveraging the extensive Alexandria dataset, the research successfully generates a multimodal dataset comprising chemical compositions (text), crystal structures (images), and structural properties (tabular data). This approach highlights the potential of combining diverse data sources for material property predictions.

- Implementation of advanced model automation: The study integrates AutoGluon for model tuning, significantly reducing the manual effort required for hyperparameter optimization. This automation ensures efficient development and fine-tuning of deep learning models across multiple modalities.

- Improved predictive accuracy with multimodal integration: Results demonstrate that combining text and image modalities improves the predictive accuracy of material property models compared to single-modality approaches. The fusion techniques employed capture complementary information, enhancing model performance.

2. Modalities

- Multimodal alignment: Developing universal principles to govern interactions across modalities is a key objective, with a strong emphasis on identifying and understanding cross-modal interactions [12].

- Compositionality: Foundational to neural networks, this principle supports hierarchical learning by transforming raw data into higher-level representations, enabling reasoning and generalization to out-of-distribution scenarios [9].

- Representation generation: Research focuses on creating efficient, modality-specific representations, often leveraging encoder-decoder architectures to capture modality-specific nuances [13].

- Transferability of representations: Modern multimodal frameworks emphasize using pre-trained models to accelerate new tasks with minimal data, promoting representation transfer within and across modalities [13].

- Representation fusion: Among the most complex challenges, representation fusion aims to seamlessly integrate diverse semantic data types (e.g., images, text, or knowledge graphs). This process requires normalization and embedding before integration, which is crucial for building scalable multimodal learning systems [9].

2.1. Data Modalities

2.1.1. Tabular Data

- Atomic structure: Including details like atomic coordinates, bond types, and lattice parameters that define the spatial arrangement of atoms within a crystal.

- Electronic properties: Such as band gaps, electronic densities, and magnetic properties.

- Thermodynamic and mechanical properties: Like enthalpy of formation, elasticity, and thermal conductivity, which are crucial for predicting material stability and suitability for various applications.

2.1.2. Image Data

2.1.3. Text Data

2.2. Single Modality Machine Learning Models

2.2.1. Composition-Based Models

- Masked Language Modeling (MLM): Inspired by the Cloze task [21], MLM randomly masks 15% of tokens in a sequence and tasks the model with predicting the masked tokens using context from both directions. This objective encourages BERT to develop a nuanced, bidirectional understanding of language, differentiating it from traditional unidirectional models.

- Next Sentence Prediction (NSP): This task trains BERT to identify relationships between sentence pairs. Half of the training pairs are consecutive sentences, while the other half are randomly paired. The model learns to predict whether the second sentence logically follows the first, a capability particularly useful for tasks like question answering and natural language inference.

2.2.2. Graph Neural Networks

- Input block: This block includes a Linear layer and an Embedding layer. Each node’s input features are transformed into 256-dimensional vectors using the Linear layer. For edges, an Embedding layer maps Coulomb potentials and infinite potential summations into 256-dimensional embeddings.

- Interaction block: Comprising multiple interaction layers, this block updates each node’s feature vector by incorporating features from neighboring nodes and edge embeddings. For each neighboring node, embeddings are concatenated along the edge dimension and then with node features along the feature dimension, as in CGCNN [31].

- Readout block: This block includes an AvgPooling layer followed by a Linear layer. The AvgPooling layer aggregates features from all nodes, and the Linear layer maps the aggregated 256-dimensional hidden features to a final scalar output.

2.2.3. Image-Based Models

3. Multimodal Learning Models and Frameworks

3.1. Fusion Techniques

- Early Fusion (Feature-Based): Features from different modalities are integrated immediately after extraction, often by concatenating their representations.

- Late Fusion (Decision-Based): Integration occurs after each modality has been independently processed, with decisions (e.g., classifications or regressions) from individual modalities combined in the final stage.

- Hybrid Fusion [43]: Combines the outputs from early fusion with predictions from individual unimodal models, leveraging both feature-level and decision-level information.

3.1.1. Early Fusion

3.1.2. Late Fusion

3.1.3. Hybrid Fusion

3.2. CLIP

- Image Encoder: A convolutional neural network (CNN) or a vision transformer (ViT) that processes images and maps them into the shared latent space.

- Text Encoder: A transformer-based model that processes text descriptions and maps them into the same latent space as the images.

- Zero-Shot Learning: CLIP excels at zero-shot learning by leveraging its shared embedding space to link unseen classes to seen ones through textual descriptions. This capability allows it to retrieve relevant images for new class descriptions without explicit training on those classes.

- Cross-Modal Retrieval: CLIP performs effectively in cross-modal retrieval, enabling the retrieval of images based on text queries and the identification of text descriptions based on images. This functionality is particularly useful for search engines, content recommendation systems, and other applications requiring robust cross-modal interactions [48].

- Content Moderation and Filtering: CLIP supports content moderation by matching inappropriate text with corresponding images, helping platforms manage large volumes of user-generated content and ensure compliance with community guidelines.

- Enhanced Image Captioning: By aligning images and text in a shared latent space, CLIP improves image captioning quality. It produces more accurate and contextually relevant captions that closely match the visual content, enhancing the overall captioning experience [49].

3.3. MultiMat

3.4. AutoGluon-Multimodal

3.5. Challenges in Multimodal Learning

4. Empirical Study

4.1. Data Understanding

4.2. Dataset Construction and Multimodal Generation

4.2.1. Generating the Image Modality for Multimodal Learning

4.2.2. Standardizing Structural Data for Tabular Representation

4.2.3. Generating the Text Modality for Multimodal Learning

4.2.4. Target Feature Selection

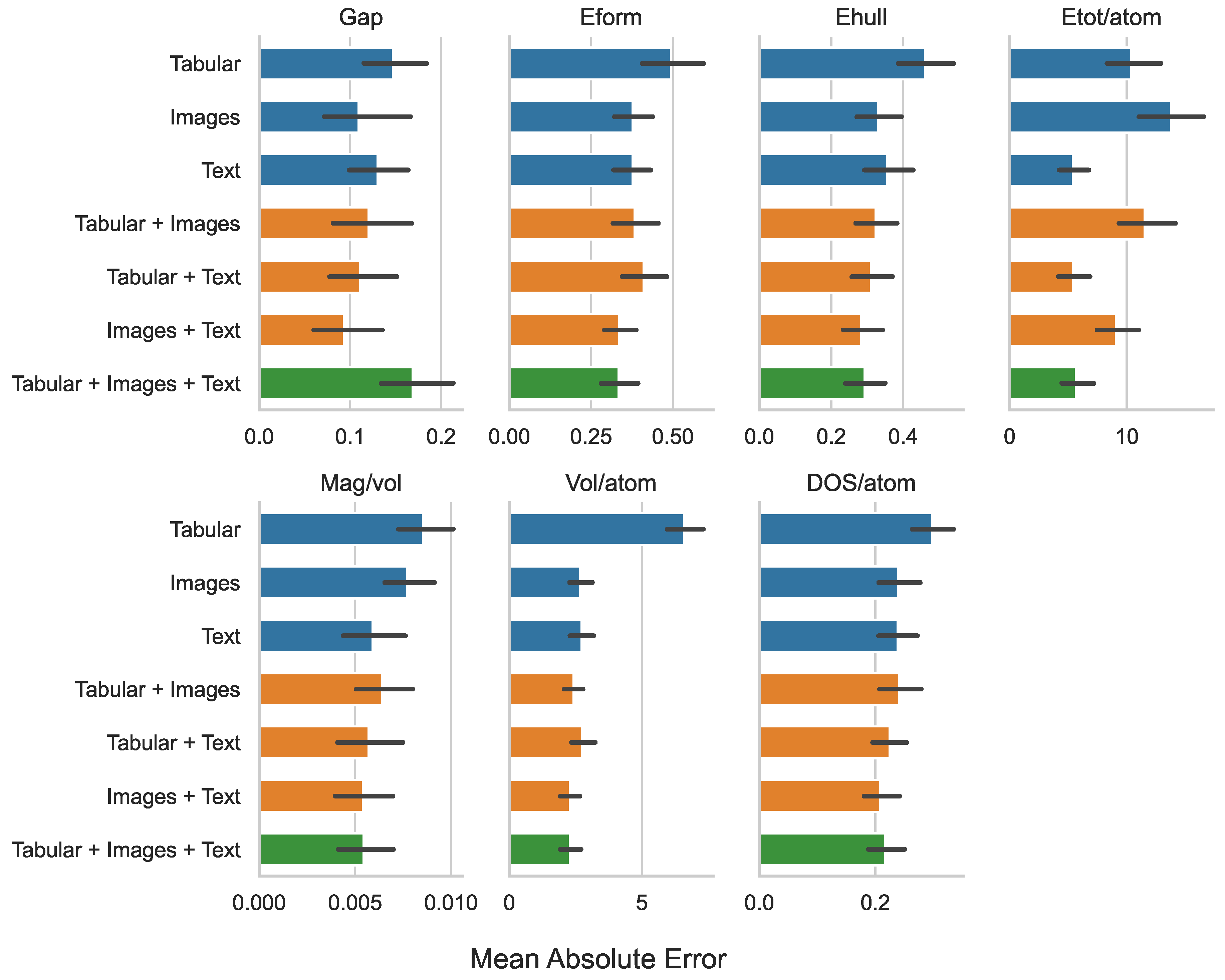

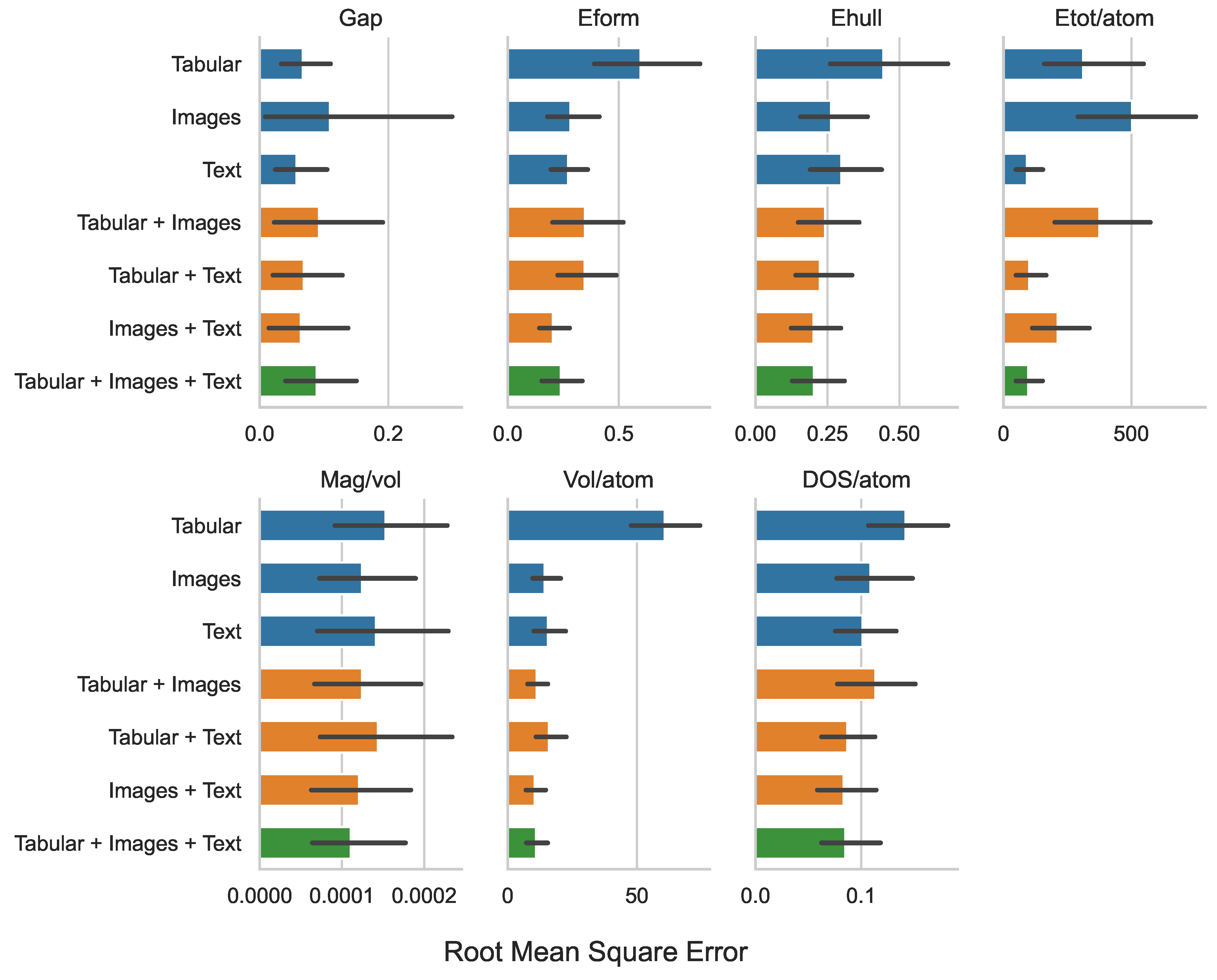

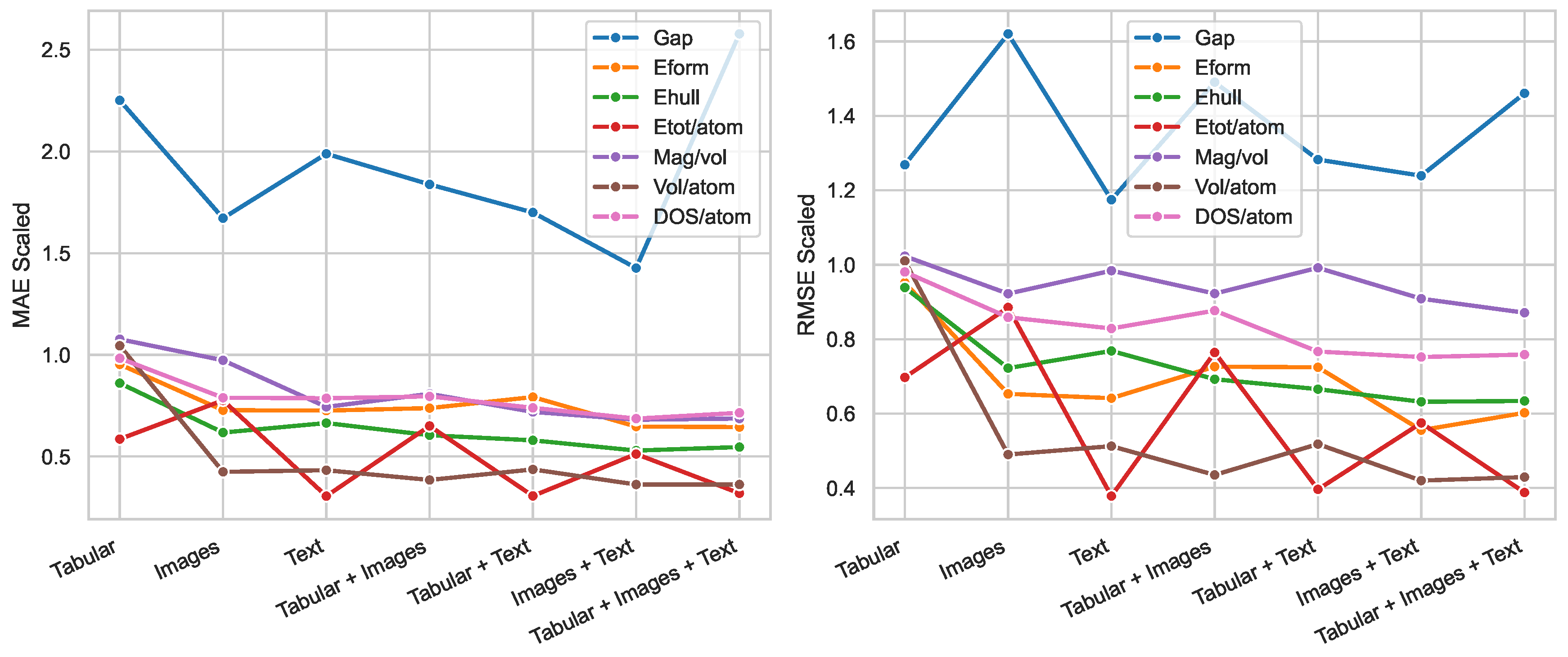

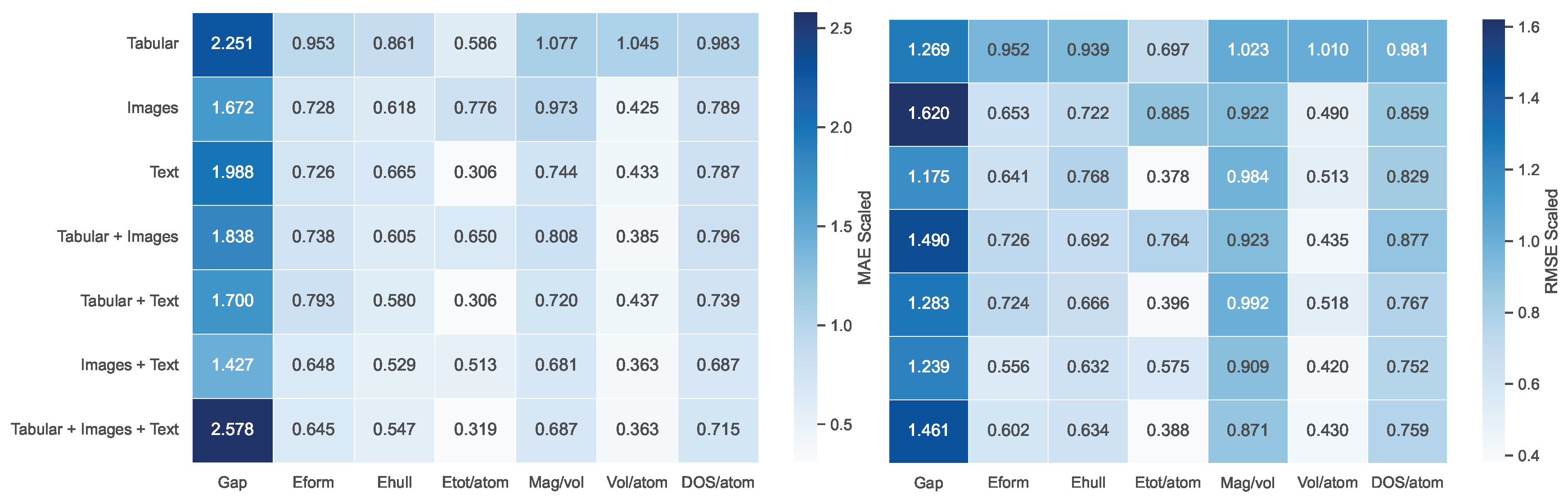

- Gap (eV): This represents the band gap in electron volts, a key indicator of a material’s electronic behavior, such as whether it functions as a conductor, insulator, or semiconductor. The values were directly retrieved from the band_gap_ind.

- Eform (eV atom−1): The formation energy per atom in electron volts, reflecting the thermodynamic stability of the material. This feature was sourced directly from the e_form.

- Ehull (eV atom−1): Energy above the convex hull per atom in electron volts, indicating the material’s stability relative to potential phase separation. These values were derived from the e_above_hull.

- Etot/atom (eV atom−1): The total energy per atom in electron volts, representing the cumulative stability and binding energy of the atomic configuration. This feature was calculated by dividing the energy_total by the number of atomic sites (nsites).

- Mag/vol ( Å−3): The magnetic moment per unit volume, measured in micro-Bohr magnetons per cubic angstrom, providing a normalized measure of the material’s magnetism. This value was computed by dividing the total_mag by the volume.

- Vol/atom (Å3 atom−1): The atomic volume per atom in cubic angstroms, offering insights into atomic packing density. This feature was calculated by dividing the volume by nsites.

- DOS/atom (states (eV atom)−1): The density of electronic states per atom at the Fermi level, which provides insights into the material’s electronic and conductive properties. This feature was computed by dividing the dos_ef by nsites.

4.3. Dataset Alignment

4.4. Multimodal Training Pipeline

4.5. Evaluation and Analysis

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chapman, P.; Clinton, J.; Kerber, R.; Khabaza, T.; Reinartz, T.; Shearer, C.; Wirth, R. CRIPS-DM 1.0 Step by Step Data Mining Guide. Technical report, CRISP-DM Consortium, 2000.

- Ramos, P.; Oliveira, J.M. Robust Sales Forecasting Using Deep Learning with Static and Dynamic Covariates. Applied System Innovation 2023, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, J.; Cerqueira, T.F.; Romero, A.H.; Loew, A.; Jäger, F.; Wang, H.C.; Botti, S.; Marques, M.A. Improving machine-learning models in materials science through large datasets. Materials Today Physics 2024, 48, 101560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltrusaitis, T.; Ahuja, C.; Morency, L.P. Multimodal Machine Learning: A Survey and Taxonomy. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2019, 41, 423–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summaira, J.; Li, X.; Shoib, A.M.; Li, S.; Jabbar, A. Recent Advances and Trends in Multimodal Deep Learning: A Review. arXiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Wang, J.; Wang, S. Deep Multimodal Representation Learning: A Survey. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 63373–63394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, M.; Oliveira, J.M.; Ramos, P. Enhancing Hierarchical Sales Forecasting with Promotional Data: A Comparative Study Using ARIMA and Deep Neural Networks. Machine Learning and Knowledge Extraction 2024, 6, 2659–2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, J.M.; Ramos, P. Investigating the Accuracy of Autoregressive Recurrent Networks Using Hierarchical Aggregation Structure-Based Data Partitioning. Big Data and Cognitive Computing 2023, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Škrlj, B. From Unimodal to Multimodal Machine Learning: An overview; SpringerBriefs in Computer Science, Springer Cham, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, J.M.; Ramos, P. Cross-Learning-Based Sales Forecasting Using Deep Learning via Partial Pooling from Multi-level Data. In Proceedings of the Engineering Applications of Neural Networks; Iliadis, L.; Maglogiannis, I.; Alonso, S.; Jayne, C.; Pimenidis, E., Eds., Cham, 2023; pp. 279–290. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, J.M.; Ramos, P. Evaluating the Effectiveness of Time Series Transformers for Demand Forecasting in Retail. Mathematics 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, P.P.; Zadeh, A.; Morency, L.P. Foundations & Trends in Multimodal Machine Learning: Principles, Challenges, and Open Questions. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wei, F.; Sun, X.; Wu, Z.; Lin, S. A Simple Multi-Modality Transfer Learning Baseline for Sign Language Translation. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2022; pp. 5110–5120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Ong, S.P.; Hautier, G.; Chen, W.; Richards, W.D.; Dacek, S.; Cholia, S.; Gunter, D.; Skinner, D.; Ceder, G.; et al. Commentary: The Materials Project: A materials genome approach to accelerating materials innovation. APL Materials 2013, 1, 011002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Yan, K.; Luo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Qian, X.; Ji, S. Efficient Approximations of Complete Interatomic Potentials for Crystal Property Prediction. In Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Machine Learning; Krause, A.; Brunskill, E.; Cho, K.; Engelhardt, B.; Sabato, S.; Scarlett, J., Eds. PMLR, 23–29 Jul 2023, Vol. 202, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pp. 21260–21287. [CrossRef]

- Horton, M.; Shen, J.X.; Burns, J.; Cohen, O.; Chabbey, F.; Ganose, A.M.; Guha, R.; Huck, P.; Li, H.H.; McDermott, M.; et al. Crystal Toolkit: A Web App Framework to Improve Usability and Accessibility of Materials Science Research Algorithms. arXiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Zhu, X.; Clifton, D.A. Multimodal Learning With Transformers: A Survey. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis & Machine Intelligence 2023, 45, 12113–12132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers); Burstein, J.; Doran, C.; Solorio, T., Eds., Minneapolis, Minnesota, 6 2019; pp. 4171–4186. [CrossRef]

- Radford, A.; Narasimhan, K.; Salimans, T.; Sutskever, I. Radford, A.; Narasimhan, K.; Salimans, T.; Sutskever, I. Improving Language Understanding by Generative Pre-Training. 2018. Available online: https://cdn.openai.com/research-covers/language-unsupervised/language_understanding_paper.pdf.

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.u.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is All you Need. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2017, Vol. 30, pp. 5998–6008. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, W.L. “Cloze Procedure”: A New Tool for Measuring Readability. Journalism Quarterly 1953, 30, 415–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Singh, A.; Michael, J.; Hill, F.; Levy, O.; Bowman, S. GLUE: A Multi-Task Benchmark and Analysis Platform for Natural Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the 2018 EMNLP Workshop BlackboxNLP: Analyzing and Interpreting Neural Networks for NLP; Linzen, T.; Chrupała, G.; Alishahi, A., Eds., Brussels, Belgium, 2018; pp. 353–355. [CrossRef]

- Rajpurkar, P.; Zhang, J.; Lopyrev, K.; Liang, P. SQuAD: 100,000+ Questions for Machine Comprehension of Text. In Proceedings of the 2016 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; Su, J.; Duh, K.; Carreras, X., Eds., Austin, Texas, 11 2016; pp. 2383–2392. [CrossRef]

- Zellers, R.; Bisk, Y.; Schwartz, R.; Choi, Y. SWAG: A Large-Scale Adversarial Dataset for Grounded Commonsense Inference. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; Riloff, E.; Chiang, D.; Hockenmaier, J.; Tsujii, J., Eds., Brussels, Belgium, 2018; pp. 93–104. [CrossRef]

- MatBERT GitHub. MatBERT: A pretrained BERT model on materials science literature. 2021. Available online: https://github.com/lbnlp/MatBERT.

- Wang, A.Y.T.; Kauwe, S.K.; Murdock, R.J.; Sparks, T.D. Compositionally restricted attention-based network for materials property predictions. npj Computational Materials 2021, 7, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarselli, F.; Gori, M.; Tsoi, A.C.; Hagenbuchner, M.; Monfardini, G. The Graph Neural Network Model. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks 2009, 20, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Pan, S.; Chen, F.; Long, G.; Zhang, C.; Yu, P.S. A Comprehensive Survey on Graph Neural Networks. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2021, 32, 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipf, T.N.; Welling, M. Semi-Supervised Classification with Graph Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Veličković, P.; Cucurull, G.; Casanova, A.; Romero, A.; Liò, P.; Bengio, Y. Graph Attention Networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations; 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, T.; Grossman, J.C. Crystal Graph Convolutional Neural Networks for an Accurate and Interpretable Prediction of Material Properties. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 120, 145301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasteiger, J.; Groß, J.; Günnemann, S. Directional Message Passing for Molecular Graphs. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations; 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasteiger, J.; Becker, F.; Günnemann, S. GemNet: Universal Directional Graph Neural Networks for Molecules. In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems; Ranzato, M.; Beygelzimer, A.; Dauphin, Y.; Liang, P.; Vaughan, J.W., Eds. Curran Associates, Inc., 2021, Vol. 34, pp. 6790–6802. [CrossRef]

- Schütt, K.T.; Kindermans, P.J.; Sauceda, H.E.; Chmiela, S.; Tkatchenko, A.; Müller, K.R. SchNet: A continuous-filter convolutional neural network for modeling quantum interactions. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017; NIPS’17, p. 992–1002. [CrossRef]

- Lecun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y.; Haffner, P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proceedings of the IEEE 1998, 86, 2278–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2016, pp. 770–778. [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q.V. EfficientNet: Rethinking Model Scaling for Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML 2019, 9-15 June 2019, Long Beach, California, USA; Chaudhuri, K.; Salakhutdinov, R., Eds. PMLR, 2019, Vol. 97, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pp. 6105–6114. [CrossRef]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin Transformer: Hierarchical Vision Transformer using Shifted Windows . In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Los Alamitos, CA, USA, 10 2021; pp. 9992–10002. [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Dong, W.; Socher, R.; Li, L.J.; Li, K.; Fei-Fei, L. ImageNet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2009, pp. 248–255. [CrossRef]

- D’mello, S.K.; Kory, J. A Review and Meta-Analysis of Multimodal Affect Detection Systems. ACM Comput. Surv. 2015, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Pantic, M.; Roisman, G.I.; Huang, T.S. A Survey of Affect Recognition Methods: Audio, Visual, and Spontaneous Expressions. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2009, 31, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atrey, P.K.; Hossain, M.A.; El Saddik, A.; Kankanhalli, M.S. Multimodal fusion for multimedia analysis: A survey. Multimedia Systems 2010, 16, 345–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Cai, L.; Meng, H. Multi-level Fusion of Audio and Visual Features for Speaker Identification. In Proceedings of the Advances in Biometrics; Zhang, D.; Jain, A.K., Eds., Berlin, Heidelberg, 2005; pp. 493–499. https://doi.org/10.1007/11608288_66. [CrossRef]

- Lan, Z.z.; Bao, L.; Yu, S.I.; Liu, W.; Hauptmann, A.G. Double Fusion for Multimedia Event Detection. In Proceedings of the Advances in Multimedia Modeling; Schoeffmann, K.; Merialdo, B.; Hauptmann, A.G.; Ngo, C.W.; Andreopoulos, Y.; Breiteneder, C., Eds., Berlin, Heidelberg, 2012; pp. 173–185. [CrossRef]

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, C.; Ramesh, A.; Goh, G.; Agarwal, S.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Mishkin, P.; Clark, J.; et al. Learning Transferable Visual Models From Natural Language Supervision. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning; 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Kornblith, S.; Norouzi, M.; Hinton, G. A simple framework for contrastive learning of visual representations. In Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Machine Learning. JMLR.org, 2020, ICML’20. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Zheng, L.; Garrett, M.; Yang, Y.; Xu, M.; Shen, Y.D. Dual-path Convolutional Image-Text Embeddings with Instance Loss. ACM Trans. Multimedia Comput. Commun. Appl. 2020, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Ba, J.; Kiros, R.; Cho, K.; Courville, A.; Salakhudinov, R.; Zemel, R.; Bengio, Y. Show, Attend and Tell: Neural Image Caption Generation with Visual Attention. In Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Machine Learning; Bach, F.; Blei, D., Eds., Lille, France, 07–09 Jul 2015; Vol. 37, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pp. 2048–2057. [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Krishnan, D.; Isola, P. Contrastive Multiview Coding. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision – ECCV 2020; Vedaldi, A.; Bischof, H.; Brox, T.; Frahm, J.M., Eds., Cham, 2020; pp. 776–794. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xie, C.; Cubuk, E.D. Scaling (Down) CLIP: A Comprehensive Analysis of Data, Architecture, and Training Strategies. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro, V.; Loh, C.; Dangovski, R.; Ghorashi, A.; Ma, A.; Chen, Z.; Kim, S.; Lu, P.Y.; Christensen, T.; Soljačić, M. Multimodal Learning for Materials. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Fang, H.; Zhou, S.; Yang, T.; Zhong, Z.; Hu, C.; Kirchhoff, K.; Karypis, G. AutoGluon-Multimodal (AutoMM): Supercharging Multimodal AutoML with Foundation Models. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Automated Machine Learning; Eggensperger, K.; Garnett, R.; Vanschoren, J.; Lindauer, M.; Gardner, J.R., Eds. PMLR, 09–12 Sep 2024, Vol. 256, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pp. 15/1–35. [CrossRef]

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| BeCoSi |

| Modalities | Gap | Eform | Ehull | Etot/atom | Mag/vol | Vol/atom | DOS/atom |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (eV) | (eV atom−1) | (eV atom−1) | (eV atom−1) | ( Å−3) | (Å3 atom−1) | (states (eV atom)−1) | |

| Tabular | 0.147 | 0.494 | 0.461 | 10.384 | 0.009 | 6.588 | 0.299 |

| Images | 0.109 | 0.377 | 0.331 | 13.761 | 0.008 | 2.679 | 0.240 |

| Text | 0.130 | 0.376 | 0.356 | 5.416 | 0.006 | 2.728 | 0.239 |

| Tabular + Images | 0.120 | 0.383 | 0.324 | 11.528 | 0.006 | 2.427 | 0.242 |

| Tabular + Text | 0.111 | 0.411 | 0.310 | 5.430 | 0.006 | 2.754 | 0.225 |

| Images + Text | 0.093 | 0.336 | 0.283 | 9.085 | 0.005 | 2.286 | 0.208 |

| Tabular + Images + Text | 0.169 | 0.334 | 0.292 | 5.660 | 0.005 | 2.288 | 0.217 |

| Modalities | Gap | Eform | Ehull | Etot/atom | Mag/vol | Vol/atom | DOS/atom |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (eV) | (eV atom−1) | (eV atom−1) | (eV atom−1) | ( Å−3) | (Å3 atom−1) | (states (eV atom)−1) | |

| Tabular | 0.259 | 0.773 | 0.667 | 17.654 | 0.012 | 7.792 | 0.377 |

| Images | 0.330 | 0.531 | 0.513 | 22.411 | 0.011 | 3.780 | 0.330 |

| Text | 0.239 | 0.521 | 0.546 | 9.579 | 0.012 | 3.954 | 0.319 |

| Tabular + Images | 0.304 | 0.590 | 0.492 | 19.348 | 0.011 | 3.358 | 0.337 |

| Tabular + Text | 0.261 | 0.589 | 0.473 | 10.036 | 0.012 | 3.997 | 0.295 |

| Images + Text | 0.253 | 0.451 | 0.449 | 14.555 | 0.011 | 3.240 | 0.289 |

| Tabular + Images + Text | 0.298 | 0.489 | 0.450 | 9.822 | 0.011 | 3.313 | 0.292 |

| Modalities | Gap | Eform | Ehull | Etot/atom | Mag/vol | Vol/atom | DOS/atom |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (eV) | (eV atom−1) | (eV atom−1) | (eV atom−1) | ( Å−3) | (Å3 atom−1) | (states (eV atom)−1) | |

| Tabular | 2.251 | 0.953 | 0.861 | 0.586 | 1.077 | 1.045 | 0.983 |

| Images | 1.672 | 0.728 | 0.618 | 0.776 | 0.973 | 0.425 | 0.789 |

| Text | 1.988 | 0.726 | 0.665 | 0.306 | 0.744 | 0.433 | 0.787 |

| Tabular + Images | 1.838 | 0.738 | 0.605 | 0.650 | 0.808 | 0.385 | 0.796 |

| Tabular + Text | 1.700 | 0.793 | 0.580 | 0.306 | 0.720 | 0.437 | 0.739 |

| Images + Text | 1.427 | 0.648 | 0.529 | 0.513 | 0.681 | 0.363 | 0.687 |

| Tabular + Images + Text | 2.578 | 0.645 | 0.547 | 0.319 | 0.687 | 0.363 | 0.715 |

| Modalities | Gap | Eform | Ehull | Etot/atom | Mag/vol | Vol/atom | DOS/atom |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (eV) | (eV atom−1) | (eV atom−1) | (eV atom−1) | ( Å−3) | (Å3 atom−1) | (states (eV atom)−1) | |

| Tabular | 1.269 | 0.952 | 0.939 | 0.697 | 1.023 | 1.010 | 0.981 |

| Images | 1.620 | 0.653 | 0.722 | 0.885 | 0.922 | 0.490 | 0.859 |

| Text | 1.175 | 0.641 | 0.768 | 0.378 | 0.984 | 0.513 | 0.829 |

| Tabular + Images | 1.490 | 0.726 | 0.692 | 0.764 | 0.923 | 0.435 | 0.877 |

| Tabular + Text | 1.283 | 0.724 | 0.666 | 0.396 | 0.992 | 0.518 | 0.767 |

| Images + Text | 1.239 | 0.556 | 0.632 | 0.575 | 0.909 | 0.420 | 0.752 |

| Tabular + Images + Text | 1.461 | 0.602 | 0.634 | 0.388 | 0.871 | 0.430 | 0.759 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).