1. Introduction

Investing is an important source of economic growth, but every investor faces different risks. Investment risks depend directly on the fortunate confluence of various factors. Identifying the factors that give rise to investment risk and researching them is important in making sound business decisions. Investment risk management is an important prerequisite for the effective functioning of economic entities and an economy as a whole [

1,

36]. Inadequate consideration of these risks’ impact can lead to significant financial losses. Given the forecasts of a slowdown in China’s economic growth as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, the risks of foreign investment in the context of Belt and Road Initiative require special attention [

34]. The worsening outlook for some developing countries, especially Belt and Road Initiative participants and commodity exporters, reduces their reliability. Along with the possibility of U.S. monetary policy volatility, this increases the risk of financial shortages [

6,

45]. If all of these risks are realized simultaneously, the destabilization of developing countries could be significant.

China’s current growth in foreign investment, supported by the government’s economic expansion strategy (the “go global” policy), reflects two fundamental shifts in the Chinese economy - one at the macro level and the other at the micro level. On a macroeconomic level, China needs to balance its international capital flows to avoid having to revalue its currency [

27,

48]. At the microeconomic level, more and more Chinese enterprises have incentives and opportunities to pursue internationalization strategies to increase their comparative advantage and profitability. During the rapid influx of foreign investment, many Chinese companies gained the experience and knowledge needed to operate in the international market, so they are ready to implement their own programs of overseas expansion or diversification under Belt and Road Initiative [

20]. Moreover, the threat of overproduction in some industries in the domestic market is another incentive to develop new markets in foreign countries [

23]. Since China’s interest in foreign investment is based more on economic considerations than on political agendas, this trend should continue in the future, as basic economic conditions will remain unchanged. If current economic conditions persist, the upward trend in foreign investment flows from China will continue in the near future. It will be supported by further liberalization of administrative and financial regulation of foreign investment as part of the government’s globalization policy [

30]. In reforming China’s state-owned enterprises and industry in general, private enterprises will gradually increase their share of investment activities in foreign countries, although some industries, such as fuel and energy, will remain under the control of large state-owned companies [

32,

46].

As a result, the role of Belt and Road Initiative as a determinant of foreign investment by Chinese companies was a topic of intense discussion. An important issue is that, in doing so, regional integration associations complement or substitute foreign investment within the project. Regional integration agreements under Belt and Road Initiative generally provide for the reduction of trade barriers and investment restrictions. Accordingly, the impact of regional integration associations on overseas investment by Chinese enterprises reflects the effect that liberalization of trade and investment regime produces [

33,

47]. Under the influence of changes in relative costs in Belt and Road Initiative countries and third countries, changes in the relative rates of economic growth affect investors’ vision of political, project, and other risks and consequently cause transformations in the preferences of Chinese companies. Some of these transformations are direct results of economic integration: for example, a reduction in customs rates changes the comparative attractiveness of exports compared to the creation of a unit in foreign countries. Other changes are indirectly affected by regional integration agreements: for example, the acceleration or deceleration of relative and absolute growth rates is reflected in foreign investment flows [

28]. Therefore, this study aims to fill this gap through a comprehensive approach to assessing foreign investment risks of Chinese companies. This influenced the research objective, which is to form a comprehensive methodological approach to assessing Chinese companies’ risk management effectiveness in foreign investment based on factor complementarity of Belt and Road Initiative project ties.

2. Literature Review

Risk is considered as a consequence of events, so it is classified and evaluated on the basis of its effects. Since the combinability of events is very high, there are many situations, each of which is alternative to others, has a certain probability, the main source of risk formation and the boundaries of its manifestation [

37]. Given the huge number of major sources of risk formation, it is possible to identify different classes of this category and use induction to highlight their properties. This logical model is the basis of the theory describing the functioning of such a categorized phenomenon as risk. Therefore, risk can be interpreted as both a factor and a consequence, accompanied by three conditions: the presence, uncertainty, and alternativeness of risk events [

2].

Location factors influence a firm’s decision to invest abroad [

43]. Import barriers imposed by a recipient state are often the main reason for foreign investment in developing countries. To protect their position in foreign markets, which firms have gained through exports, they respond to protectionist measures by establishing subsidiaries and joint ventures in a recipient country [

7]. Thus, in part, foreign investment can be considered a protective measure by its very nature. For example, when textile exports from Hong Kong were threatened by import restrictions from Indonesia, firms responded by forming businesses in that country [

29]. Another reason for foreign investment in developing countries is the desire to reduce risk through diversification. This risk is related to political instability or to threats of changes in political development in a recipient country. Thus, multinational corporations of the Third World see investment as a means of mitigating overall political risk [

8]. Another driver of foreign investment is the role of the diaspora. Ethnic networks play an intermediary role in connecting buyer and seller in the international marketplace. They receive particularly favorable conditions in a country of origin, which allows them to serve as a bridge between a donor country and a recipient country [

1].

In part, offshoring is a popular investment option because Chinese government policies suppress the development of local capital markets. In the face of domestic barriers, Chinese entrepreneurs are forced to use offshore to locate those businesses for which access to financial services and freedom of capital movement are essential [

42]. By moving business offshore, large Chinese enterprises diversify domestic risks and gain flexible corporate financing and structure. Most of the funds invested offshore later come back to China in the form of foreign direct investment - these offshore companies are also the largest investors for the Chinese economy. Hong Kong accounts for 30% of all investment in China, the British Virgin Islands for 15%, and the Cayman Islands for 3%[

12].

Belt and Road Initiative was designed to strengthen China’s influence on the world economy. The initiative also provides economic benefits to countries that are linked through six economic corridors. In this sense, China’s economic policy stimulus contributes to the strategic goals [

9]. The implementation of Belt and Road Initiative could have a huge impact on the global financial system, since the value of the related investments amounts to hundreds of billions or even trillions of US dollars. Funding comes from several sources provided by international financial institutions created by China. The state-owned Silk Road Fund started with a

$40 billion capital investment in 2014[

41]. The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), established by China, began in 2015 with a

$100 billion capital investment. The purpose of its activities is to support investment in the framework of Belt and Road Initiative [

21]. The Chinese government relies on the resources of the New Development Bank, based in Shanghai and established in 2014 by the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) countries [

11], as well as traditional competitors (the Asian Development Bank or the World Bank)[

18]. Financial participation of countries in the implementation of specific projects is also planned. Large companies in the Western world are interested in making investments, and the implementation of the initiative is expected to lead to an increase in purchases. As a co-owner of large European and American companies or an investor in their projects, China aims to attract financial actors from the Western world to invest [

35]. In doing so, China plans to simultaneously realize its short- and long-term goals. Belt and Road Initiative can be considered the most important foundation of Chinese policy, a strategy to be supported by successive governments in the years and decades to come. There is no firm commitment in the action plan; this does not indicate imperfection, but reflects that the strategy can be executed flexibly, since participants’ goals may change in the future [

19].

China is shifting from exporting goods to increasing outbound investment. In particular, China has invested more in Europe than European companies in China [

22]. Belt and Road Initiative implements China’s global investment strategy, diversification of foreign assets, and international expansion of major Chinese transport infrastructure companies [

14]. Projects are financed by the Silk Road Fund, as well as the China Exim bank and the AIIB, which are involved in lending [

4,

16].

Belt and Road Initiative promises tremendous opportunities for investment and development for relevant economic sectors and enterprises. Today, many countries in South Asia (e.g., India), Southeast Asia (e.g., Indonesia) and Central Asia (e.g., Kazakhstan) suffer from a lack of funds, technology and expertise, especially in the areas of industry and infrastructure [

3]. When it comes to infrastructure, China offers incredible opportunities for international cooperation and know-how transfer. In today’s environment, China’s foreign trade and investment relations are growing stronger, and the use of the renminbi as an official reserve asset is spreading [

25].

Foreign investment risk management, taking into account the participation of Chinese companies in Belt and Road Initiative, as well as the impact of project ties on the level of risks, remains insufficiently studied despite the diversity of modern scientific works in the context of Chinese companies’ investment. Therefore, Chinese companies’ foreign investment as a channel for the country’s economic expansion requires justification, taking into account the following factors:

- enterprise heterogeneity;

- enterprise performance;

- project ties of an enterprise in the context of underdeveloped financial structures and imperfect institutional environment, which are inherent in most developing countries participating in Belt and Road Initiative.

Therefore, this study aims to form a comprehensive methodological approach to the diagnosis of Chinese enterprises’ risk management effectiveness in foreign investment, taking into account the influence of various factors and project ties within Belt and Road Initiative. To achieve this goal, based on the reviewed modern works, the following hypotheses were formulated:

Hypothesis 1: Growth in project ties indicator increases the likelihood of foreign investment success;

Hypothesis 2: Enterprises with high productivity are more likely to make overseas investments and more likely to invest in countries with worse investment conditions, such as small market, high market entry costs, and low trade costs.

3. Materials and Methods

The methodology of the study is based on a discrete complementary double-log model and testing the hypotheses formed about Chinese companies’ foreign investment risks. In accordance with the specificity of statistical data (creation of foreign subsidiaries within a certain period of time) and the hypotheses to be tested, a discrete survival model was built, using a complementary double-log regression. In this model, the event is defined by the moment when a company makes its first foreign investment, that is, when it becomes a multinational corporation. A survival model is used instead of a regression logistic model based on censored observations in the data set. The problem of censored data arises from the observation period (2016-2023). For example, at the end of the study period, some businesses will still only be producing domestically, but that does not mean that they will never make foreign investments in the future. This is a common type of censorship. A logistic regression model is usually used when the dependent variable is binary; a logistic regression is not reliable in case of censoring error. On the other hand, survival analysis also applies with dichotomous variables, but at the same time it is able to account for censoring through time-to-event analysis. Accordingly, by the given data structure and the study subject, the study uses survival analysis. A discrete survival model was chosen instead of a continuous survival model. The reason is that, first, the survival time is censored by the interval. Although the basic process is continuous in time, meaning that a business can open its first foreign venture at any point during the year, only the year in which a particular investment was made can be considered in the model, not a specific date. Second, many related events occur during the year, i.e., many new multinationals may emerge. Moreover, because survival time is censored rather than truly discrete, a discrete complementary double-log model was used rather than a discrete logistic model. For the discrete complementary double-log model, the base model is the continuous Cox proportional risk model, suitable for the statistics used in this study [

26]. The coefficients of the independent variables in the complementary double-log model are also easier to explain than in the logistic model, and they have the same value as in the Cox proportional risk model. That is, ceteris paribus, when the independent variable is increased by one, the underlying continuous risk is multiplied by the relative risk coefficient to a degree [

15]. If one assumes that events are generated by a continuous Cox proportional risk model, then the corresponding discrete complementary double-log model used in this study can be written as:

where

- is the conditional probability that the company will make its first foreign investment in year t, i.e., become a new multinational company, provided that the company has never made a foreign investment before year t. The independent variables and the theoretical hypotheses regarding their impact on the decision to invest abroad will be revised further. The coefficients of the independent variables are the same as in the basic continuous proportional risk model and have the same explanation.

– is a discrete baseline risk integrated annually, which is a function of time. The complementary double-log model can take the form of:

To explain the decision for an individual company to make a foreign investment, the model should include various characteristics of that company and temporal variables.

First, the proposed methodological approach provides conclusions that are consistent with current theoretical and empirical research on the role of productivity, namely that enterprise productivity is directly related to the likelihood that it will make foreign investments, so it is expected to be meaningful and positive. Second, the theoretical hypotheses assume that there is a direct relationship between the project ties of an enterprise and the probability of direct foreign investment. Accordingly, the indicator of project ties will have a positive sign. The study investigates how the coefficient of project ties changes with changes in the quality of the institutional environment and the dependence of an enterprise on external financing (an enterprise with project ties within Belt and Road Initiative). The theoretical hypotheses should be consistent with a significant coefficient of the interaction between project ties and the institutional environment, or between project ties and dependence on external funding. Enterprises from regions with a less developed financial market or greater need for external financing are expected to benefit greatly from project ties under Belt and Road Initiative.

A completely nonparametric main risk was determined by creating dummy variables for each interval considered. The maximum survival period in the data was 8 years, so 8 dummy variable years were included in the regression. The geographic location of a parent company in mainland China was also taken into account, through the inclusion of dummy variables of regions and provinces. There are 23 provinces, four municipalities under the direct jurisdiction of the central government (Shanghai, Beijing, Chongqing, Tianjin), five autonomous regions, and two special administrative regions (Hong Kong and Macau).

The study uses a unique data set of Chinese multinational companies established between 2016 and 2023. The sample of multinational companies is obtained from the list of Chinese companies officially listed on Chinese stock exchanges, namely Shenzhen Stock Exchange and Shanghai Stock Exchange (Shenzhen Stock Exchange, 2023). The influence of country and enterprise characteristics on the decision to make the first foreign investment in 2016-2023 was also investigated.

Since the study considers only the foundations of new foreign subsidiaries and not the foreign trade of multinational companies, logistic regression was used to examine the impact of country- and enterprise-level variables in the context of the foreign investment location decision. It follows that the probability of establishing a new foreign subsidiary is equal to the probability that an enterprise’s productivity is above the threshold productivity, which can be expressed as a function of micro and macro characteristics:

- productivity;

- project ties;

- potential market demand in a recipient country;

- trade costs and entry costs for foreign investment.

The equation of the basic logistic model can be written as follows:

The left side of the equation is the probability that a Chinese multinational will establish a foreign subsidiary in another country for the first time during the study period. – is a dichotomous (binary) response variable that can take the value 1 if a company first established at least one subsidiary in a foreign country during the study period, or 0 if a company did not make any direct investments in that country during that period. – is a logistic cumulative distribution function. The independent variables include enterprise characteristics, designated as vector , and characteristics of a country, designated as a vector . – is a residual reflecting unobservable factors at both an enterprise and a country level.

This study also determined the differences in the impact of country characteristics on enterprises with different levels of project ties and different productivity. The inclusion of terms characterizing the interaction between enterprise and country characteristics will change the coefficients of the vectors and accordingly, this is not reflected in the basic model equation, but will be explained in the corresponding empirical results. Characteristics of recipient countries help identify and examine various motivations of Chinese enterprises to invest directly in foreign countries. The first motive is the search for markets or tariff avoidance. The market-seeking motive causes horizontal foreign investment in order to serve foreign markets and avoid customs tariffs by duplicating production in another country. If horizontal foreign investment prevails among Chinese enterprises, then indicators describing foreign markets, such as GDP or GDP per capita, are expected to have a positive and statistically significant effect on the probability of establishing a new foreign subsidiary. Indicators of customs tariffs, such as the size of customs rates, will also have a positive effect. Otherwise, if horizontal foreign investment is not common among Chinese companies, these variables will not be statistically significant. Transportation costs, as one of the frequently used indicators to characterize trade barriers, have an ambiguous impact. On the one hand, high transportation costs, measured as the distance between China and a potential recipient country, can be a reason to make investments and directly serve the foreign market. On the other hand, they may deter foreign investment because of the high costs of monitoring and controlling foreign subsidiaries and supplying intermediate goods for production. As for the second motive, one should consider the sources of comparative advantage, that is, the difference in the availability of production factors determines another type of direct investment - vertical foreign investment. If vertical foreign investment is common among Chinese foreign investment, then the capital surplus coefficient is expected to be statistically significant. Although the sign may be either positive or negative, depending on the capital intensity of a particular multinational company. Hence, one should study the terms characterizing the interaction between country and company characteristics. If the search for natural resources is one of the motives that strongly influences Chinese foreign investment, then the country’s natural resource endowment is expected to have a positive and statistically significant effect on the likelihood of foreign investment.

4. Results

The correlation matrix between the productivity and various dimensions of project ties for state and non-state enterprises is shown in

Table 1 and

Table 2, respectively. As can be seen from

Table 1, there is no significant correlation between the total factor productivity (TFP) and project ties for state-owned enterprises.

For non-state enterprises, one can observe a positive correlation between project ties and TFP with different levels of significance for different indicators. The different indicators of project ties show a significant correlation between each other for both state and non-state enterprises.

The analysis of the discrete survival model was carried out using complementary double-log regression, in which the event is determined when a company makes FDI for the first time, i.e., becomes a multinational company. To determine the shape of the underlying risk function, the author estimated the basic survival and event risk probabilities for the sample under a certain complementary double-log model. As shown in

Table 3, the time period is 8 years (2016 to 2023)

. The risk of becoming a new multinational company first decreases and then increases again. Since the underlying risk function is not linear, one must include 8 dummy time variables in the regression.

The results of the complementary double-log regression of the main model are shown in

Table 4. Six alternative project ties indicators were used, so the regression results are shown in the corresponding six columns. For each regression set, the effects of the industry indicator and the effect of location are accounted for. Standard errors are robust and clustered at the firm level. The reason may be that this indicator is zero for 89% of observations, and therefore there is not enough variation to explain the effect of this indicator on the emergence of a new Chinese multinational. The coefficients of independent variables in the complementary double-log model have the same value as in the Cox proportional risk model. In other words, ceteris paribus, the underlying continuous risk is multiplied by the relative probability coefficient to a degree when the independent variable grows by one. If the risk percentage coefficient is positive, then the level of risk increases as the corresponding independent variable grows. As shown in

Table 4, the estimated TPF coefficient is highly significant and has, as expected, a positive sign. The value of the TPF coefficient remains around 0.48, regardless of how the project ties are measured. The regression results for TFP are consistent with the empirical research of many scholars and with the theoretical assumptions of the previous section, namely that more productive firms are more likely to become multinational companies. It does not matter which way of measuring design relationships is used when TFP increases by 1%, the probability of becoming a new multinational company increases by 62%, with the other independent variables held constant and the effects of scope of operation and geographic location fixed.

The coefficient of all project ties indicators is highly significant and has the expected positive sign. This means that the empirical results are independent of the way project ties are measured in the present model. The positive and statistically significant coefficient of project ties corresponds to the first hypothesis - strong project ties increase the probability of success of Chinese enterprises’ foreign investment within Belt and Road Initiative.

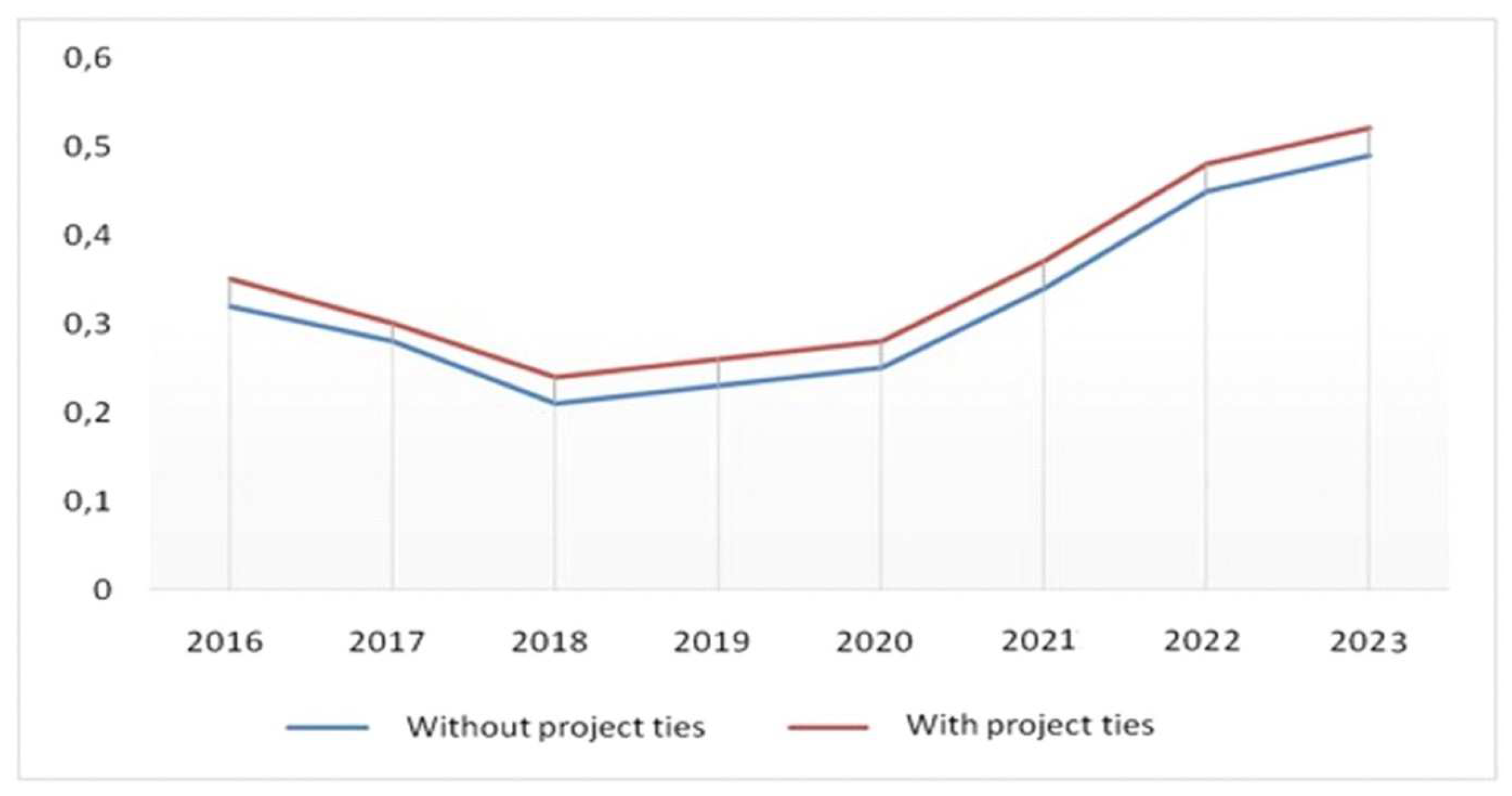

In

Figure 1, the probability of becoming a multinational company is indicated by the blue line for enterprises without project ties, and by the red line for enterprises with project ties. The two curves have the same shape, hence a common risk function is the basis: after a high probability there is a fall at the beginning and then a gradual increase for both groups. The value of the probability of foreign investment for enterprises with project ties is consistently higher than for enterprises without such ties; the value is consistent with the hypotheses.

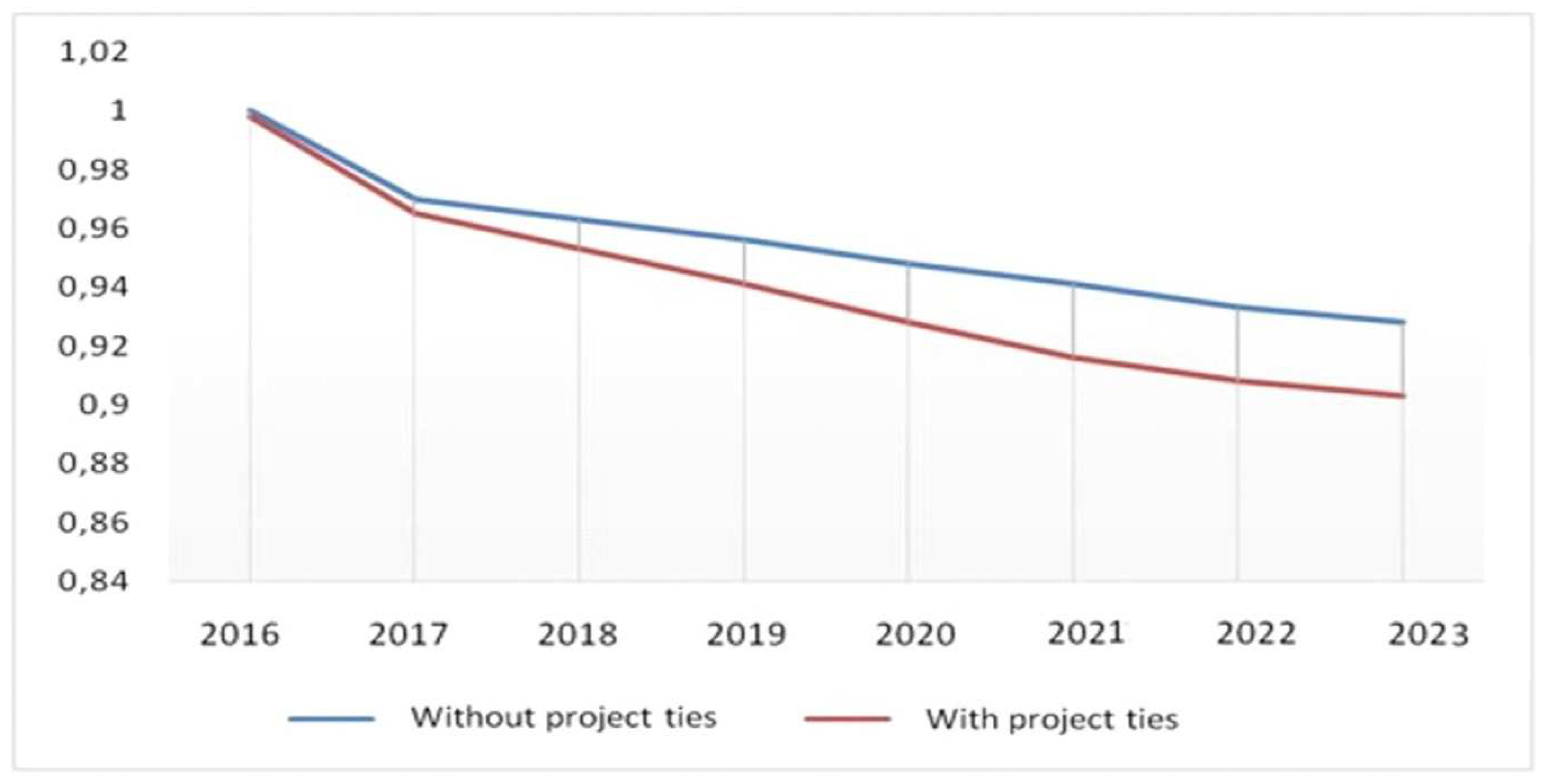

The survival function in

Figure 2 shows that firms without project ties (blue line) continue their existence as exclusively domestic enterprises (not multinational companies) for longer than firms with project ties. Thus, one can conclude that both functions confirm the first hypothesis, that enterprises with project ties are more likely to start investing in foreign countries and be successful. Consequently, both Student’s t-test and graphical analysis support the hypothesis that multinationals tend to have high performance and stronger project ties compared to national companies, and that companies with project ties are more likely to turn into a new multinational than those without ties. The results are independent of the way project ties are measured.

TFP and project ties can strongly influence a multinational company’s decision on where to invest, as suggested by the proposed model. Businesses with better technology (as measured through TFP) have higher rates of return, and therefore may invest in countries with less favorable investment climates - for example, requiring high fixed costs, having a smaller potential market, or lower trade costs. Similarly, businesses with good project ties experience fewer liquidity constraints, and therefore are more likely to invest in countries with higher costs of entry.

Let us analyze the possible impact of country characteristics on enterprises with different levels of TFP and project ties. The interaction of each of these indicators and country characteristics was determined.

Table 5 shows the obtained regression results. The first column is regression results with interaction terms with TFP. The results show that the effect of country characteristics such as GDP, skilled labor, and natural resources will differ for firms with different levels of TFP.

A cross-state study demonstrated that the TFP threshold for the recipient country decreases with potential market demand as measured by GDP; the effect of GDP on the probability of founding a new subsidiary increases by enterprise TFP. The higher a firm’s TFP, the stronger the impact of GDP. For a firm whose TFP is 75%, a 1% increase in GDP in the recipient country increases the logarithm of the odds ratio of founding a new subsidiary by only 0.0002, while for firms with high TFP the same increase in GDP can increase the logarithm of the odds ratio by 0.03. These results do not contradict previous findings in the context of different study directions. Now the study focuses on the distinctive effect of country GDP on heterogeneous enterprises, that is, on companies with different TFP levels, whereas in the cross-country analysis the focus was on the variation in minimum TFP between countries. Countries with low GDP are less attractive to investors, so only companies with high TFP can invest in such countries, so there is a negative correlation between GDP and marginal productivity. However, the results also show that multinational companies in China prefer investing in countries with a large potential market as measured by GDP, showing a positive interaction term between TFP and GDP. The results also show that the effect of the country’s endowment of skilled labor and natural resources drops behind the enterprise’s TFP. For example, for companies with medium TFP, a one percent increase in the recipient country’s share of natural resource reserves increases the logarithm of the odds ratio by 0.81, while the same change for companies with high TFP leads to an increase in the logarithm of the odds ratio by only 0.28. Similarly, a 1 percent increase in the availability of skilled labor in the recipient country causes the logarithm of the odds ratio to increase by 0.14 for firms with average TFP, while the same increase in the availability of skilled labor increases the logarithm of the odds ratio for firms with high TFP by only 0.005. The second column of

Table 5 shows the regression results with interaction terms of country characteristics with the enterprise project ties. Thus, the second hypothesis can be confirmed, since enterprises with high productivity are more likely to make foreign investments and are more likely to invest in countries with worse investment conditions, such as a small market, high market entry costs, and low trade costs. The results suggest that country characteristics have the same impact on enterprises with different levels of project ties. Because of collinearity problems, it was not possible to examine the costs of entry into a country’s market. The previous cross-country analysis suggests that enterprises that invest in countries with above-average entry costs have higher marginal project ties because they have the advantage of debt financing under liquidity constraints and high need for funds.

5. Discussion

China’s overseas investment administration procedures are likely to become more flexible in order to reduce risks for Chinese enterprises investing in foreign countries. This is especially important for small and medium-sized businesses, as well as risk management for enterprises investing abroad for the first time [

40]. It is important to take into account the financial support for the development of enterprises [

5]. The decision on the appropriateness of investments can be made by businesses themselves based on risk-adjusted profit maximization calculations, and they do not need to be confirmed or verified by the government. As experience shows, the state has no more tools to make the right decisions on investment projects than the investors themselves, represented by enterprises [

39].

The advantage of this study is the complementary double-log model formed to make the highest probability risk assessment. It takes into account the risk of violating the basic assumption in the construction of the probability function - namely, the independence of several observations for one company [

38]. For example, the independence assumption is not violated in complementary double-log models for multiple observations for a single company, because the occurrence of multiple observations is based on a multiplier decomposition of the probability function according to the definition of conditional probability [

26]. Accordingly, if more than one event is not observed for a single company during the study period (i.e., the company drops out of the sample when it makes foreign investments for the first time), then there is no violation of the independence assumption.

The peculiarity of the proposed model in the context of risk management is that in order to reflect the incentives for vertical foreign investments the capital-labor ratio coefficient for the enterprise is introduced. The meaning of this coefficient allows several interpretations. If the coefficient estimate of this variable is significant and positive, it follows that capital-intensive enterprises in China invest in foreign countries to take advantage of the capital surplus of developed countries [

24]. However, some studies of foreign investment by developing countries prove the opposite. For example, they apply the product life-cycle model to multinational companies from developing countries and the manifestation of some specific characteristics of these multinational companies - small size and labor-intensive technology [

49]. Accordingly, a significant and negative coefficient means that the comparative advantage of multinational companies in China still lies in labor-intensive technology and this strongly influences the decision to invest abroad [

17].

A limitation of determining the interaction between each of the studied indicators and country characteristics is that, under ideal conditions, this analysis requires the inclusion of the costs of entry into a country’s market in order to determine the possible differential effect of TFP and project relationships in a risk-management environment [

13,

44]. The country entry cost variable, however, is highly dependent on other country characteristics and causes a collinearity problem. A similar problem was found in the study, which indicated that the country-level fixed cost variable is highly correlated with other variables, so only variables from the gravity analysis were used [

10].

In the future, the model developed in this study can be extended to take into account the specifics of the country’s institutional environment. In the analysis, it is possible to examine the assumption that project ties within Belt and Road Initiative can help ease the liquidity constraints faced by an enterprise and, therefore, increase the likelihood of its transformation into a multinational company. It is possible to deepen the study in the context of institutional environment indicators and dependence on external financing, as well as channels of project ties to minimize foreign investment risks.

6. Conclusion

The study proves the role of specific market characteristics under Belt and Road Initiative, such as productivity and project ties, in Chinese enterprises’ foreign investment risk management. A discrete survival model based on the use of complementary double-log regression based on a unique set of statistics was developed. The study confirmed the hypotheses and concluded that Chinese enterprises operating in underdeveloped financial markets or enterprises with a greater need for external financing benefit more from the existence of project ties. Therefore, one can identify the main channel through which project ties affect a company’s foreign investment risks and a country’s economic expansion, namely credit financing, which is associated with financial constraints and a large amount of initial investment. Testing the formed model allowed determining that in countries with an underdeveloped financial sector and weak institutions project ties contribute to the decline in the average efficiency and competitiveness of enterprises in international markets. This allows formulating ways to minimize risks by improving the foreign economic and competition policy of a state through institutional reforms and increasing the transparency of financial markets.

The identified determinants made it possible to identify those influencing the choice of a recipient country for foreign direct investment of Chinese enterprises in the context of their risk management using both micro- and macro-level characteristics. The proposed methodological approach to their analysis using the integral distribution function and the developed model of logistic regression allowed obtaining results confirming the formulated hypotheses and showed that the threshold value of productivity and project ties increase under more favorable conditions for investment. Chinese companies have strong motives to invest in countries that are well endowed with capital, skilled labor and natural resources, but no evidence was found in favor of seeking new markets; the positive effect of enhanced project ties between China and a recipient country was also found. This allows, on the one hand, monitoring trends in China’s economic expansion into developing countries and, on the other hand, taking into account the impact of the identified determinants in the process of optimizing a state’s foreign economic policy.

Factors influencing the choice of country for overseas investment by Chinese multinationals using both micro and macro characteristics were investigated. The results of the study show that marginal project ties are highest for countries with higher entry costs. This suggests that project ties make it easier to obtain external financing in the face of liquidity constraints and high costs of entry. The analysis showed that there are strong motives for Chinese multinational companies to enter countries that are well endowed with capital, skilled labor and natural resources. Chinese multinational companies are also more likely to invest in countries with strong project and political ties to China, measured through the projects China offers to potential recipient countries.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

This research has no competing interests.

References

- Alexander, R. Emerging Roles of Lead Buyer Governance for Sustainability Across Global Production Networks. J. Bus. Ethic- 2019, 162, 269–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aven, T. Improving risk characterisations in practical situations by highlighting knowledge aspects, with applications to risk matrices. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2017, 167, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battamo, A.Y.; Varis, O.; Sun, P.; Yang, Y.; Oba, B.T.; Zhao, L. Mapping socio-ecological resilience along the seven economic corridors of the Belt and Road Initiative. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 309, 127341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, J.-M.F.; Flint, C. The Geopolitics of China’s Maritime Silk Road Initiative. Geopolitics 2017, 22, 223–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boichenko, K.; Mata, M.N.; Mata, P.N.; Martins, J.N. Impact of Financial Support on Textile Enterprises’ Development. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2021, 14, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouri, E.; Demirer, R.; Gupta, R.; Sun, X. The predictability of stock market volatility in emerging economies: Relative roles of local, regional, and global business cycles. J. Forecast. 2020, 39, 957–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Boateng, A.; Guney, Y. Host Country Institutions and Firm-level R&D Influences: An Analysis of European Union FDI in China. 2018, 47, 311–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavusgil, S.T.; Deligonul, S.; Ghauri, P.N.; Bamiatzi, V.; Park, B.I.; Mellahi, K. Risk in international business and its mitigation. J. World Bus. 2020, 55, 101078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-C.; Hou, J.; Xiao, D. “One Belt, One Road” Initiative to Stimulate Trade in China: A Counter-Factual Analysis. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Furceri, D.; Yoon, C. Policy uncertainty and foreign direct investment. Rev. Int. Econ. 2020, 29, 195–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, A.F. The BRICS’ New Development Bank: Shifting from Material Leverage to Innovative Capacity. Glob. Policy 2017, 8, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, R.; Hatzvi, E.; Mo, K. The size and destination of China's portfolio outflows. Appl. Econ. 2021, 53, 845–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabla-Norris, E.; Ji, Y.; Townsend, R.M.; Unsal, D.F. Distinguishing constraints on financial inclusion and their impact on GDP, TFP, and the distribution of income. J. Monetary Econ. 2020, 117, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Soyres, F.; Mulabdic, A.; Ruta, M. Common transport infrastructure: A quantitative model and estimates from the Belt and Road Initiative. J. Dev. Econ. 2019, 143, 102415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; An, H.; Liu, S.; Li, Z.; Yuan, M. Research on the time-varying network structure evolution of the stock indices of the BRICS countries based on fluctuation correlation. Int. Rev. Econ. Finance 2020, 69, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehizuelen, M.M.O. More African countries on the route: the positive and negative impacts of the Belt and Road Initiative. Transnatl. Corp. Rev. 2017, 9, 341–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Buckley, P.J.; Fu, X.M. The growth impact of Chinese direct investment on host developing countries. International Business Review 2020, 29, 101658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabusi, G. “Crossing the River by Feeling the Gold”: The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the Financial Support to the Belt and Road Initiative. China World Econ. 2017, 25, 23–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L. Does China’s belt and road initiative challenge the liberal, rules-based order? Fudan Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences 2020, 13, 113–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, L.; Peng, F.; Zhu, Y.; Pan, A. Harmony in Diversity: Can the One Belt One Road Initiative Promote China’s Outward Foreign Direct Investment? Sustainability 2018, 10, 3264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, S.G.; Kwok, A.O. Regional integration in Central Asia: Rediscovering the Silk Road. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 22, 64–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratz, A.; Huotari, M.; Hanemann, T.; Arcesati, R. Chinese FDI in Europe: 2019 update. Mercator Institute for China Studies 2020, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Lin, D. Does overcapacity prompt controlling shareholders to play a propping role for listed companies? China Journal of Accounting Research 2021, 14, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Han, Y.; He, J. How Does the Heterogeneity of Internal Control Weakness Affect R&D Investment? Emerging Markets Finance and Trade 2019, 55, 3591–3614. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Y. RMB Internationalization and Financing Belt-Road Initiative: An MMT Perspective. Chin. Econ. 2020, 53, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Moussawi, A.; Korniss, G.; Bakdash, J.Z.; Szymanski, B.K. Limits of Risk Predictability in a Cascading Alternating Renewal Process Model. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, C.; Chai, Q.; Chen, H. “Going global” and FDI inflows in China: “One Belt & One Road” initiative as a quasi-natural experiment. The World Economy 2019, 42, 1654–1672. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, D.; Lei, C.; Ullah, F.; Ullah, R.; Baloch, Q.B. China’s One Belt and One Road Initiative and Outward Chinese Foreign Direct Investment in Europe. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robison, R. Industrialization and the economic and political development of capital: the case of Indonesia. In Southeast Asian Capitalists; Cornell University Press, 2018; pp. 65–88. [Google Scholar]

- Schnabl, G. China's Overinvestment and International Trade Conflicts. China World Econ. 2019, 27, 37–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenzhen Stock Exchange (2021). Company List. Available online: http://www.cninfo.com.cn/new/snapshot/companyListEn.

- Cheng, S.; Wang, B. Impact of the Belt and Road Initiative on China's overseas renewable energy development finance: Effects and features. Renew. Energy 2023, 206, 1036–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, K. One Belt and One Road, China’s massive infrastructure project to boost trade and economy: an overview. International Critical Thought 2019, 9, 214–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A. COVID-19 and safer investment bets. Finance Res. Lett. 2020, 36, 101729–101729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutherland, D.; Anderson, J.; Bailey, N.; Alon, I. Policy, institutional fragility, and Chinese outward foreign direct investment: An empirical examination of the Belt and Road Initiative. J. Int. Bus. Policy 2020, 3, 249–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szemere, T.P.; Garai-Fodor, M.; Csiszárik-Kocsir, Á. Risk Approach—Risk Hierarchy or Construction Investment Risks in the Light of Interim Empiric Primary Research Conclusions. Risks 2021, 9, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Themsen, T.N.; Skærbæk, P. The performativity of risk management frameworks and technologies: The translation of uncertainties into pure and impure risks. Accounting, Organ. Soc. 2018, 67, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liu, H.; Bi, H. A modified infeasible interior-point algorithm with full-Newton step for semidefinite optimization. Int. J. Comput. Math. 2018, 96, 1979–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Hu, Y.; Li, L.; Sun, X. A TODIM-Based Investment Decision Framework for Commercial Distributed PV Projects under the Energy Performance Contracting (EPC) Business Model: A Case in East-Central China. Energies 2018, 11, 1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.S.; Lew, Y.K.; Park, B.I. International Network Searching, Learning, and Explorative Capability: Small and Medium-sized Enterprises from China. Manag. Int. Rev. 2020, 60, 597–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiujun, X. Silk Road Fund. In Routledge Handbook of the Belt and Road; Routledge, 2019; pp. 294–299. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Hubbard, P. A flying goose chase: China's overseas direct investment in manufacturing (2011-2013). China Econ. J. 2018, 11, 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, D.; Reimann, F. Internationalization of Developing Country Firms into Developed Countries: The Role of Host Country Knowledge-Based Assets and IPR Protection in FDI Location Choice. J. Int. Manag. 2017, 23, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, P.; Cai, Z.; Sun, Y. Does the emissions trading system in developing countries accelerate carbon leakage through OFDI? Evidence from China. Energy Econ. 2021, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Zhou, C. M&As and the Value Chain of Host Countries in the “belt and Road” — Based on Path Test of Technological Innovation. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2024, 7, 123413. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, S.; Lu, T.; Hu, X.; Liu, L.; Wei, Y.M. Determinants of overcapacity in China’s renewable energy industry: Evidence from wind, photovoltaic, and biomass energy enterprises. Energy Economics 2021, 97, 105056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Fu, Y. Local Politics and Fluctuating Engagement with China: Analysing the Belt and Road Initiative in Maritime Southeast Asia. Chinese Journal of International Politics 2022, 2, 163–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J. Why Go Global? The Logic behind Investing Overseas. In From World Factory to Global Investor; Routledge, 2017; pp. 156–162. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, T.; Xiao, X. The impact of corporate social responsibility on financial constraints: Does the life cycle stage of a firm matter? Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2018, 63, 76–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).