Submitted:

23 January 2025

Posted:

24 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

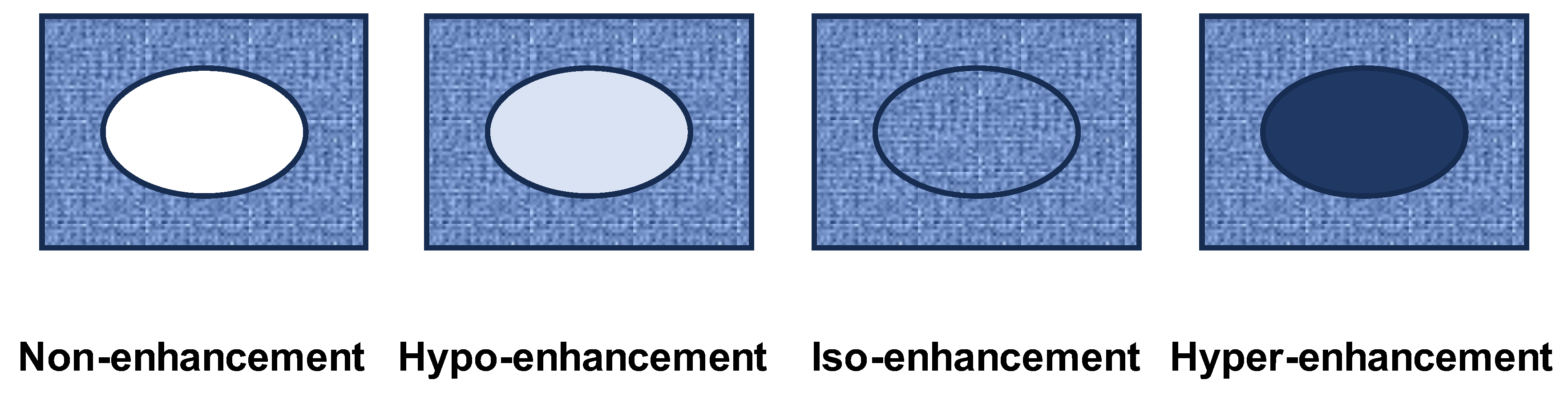

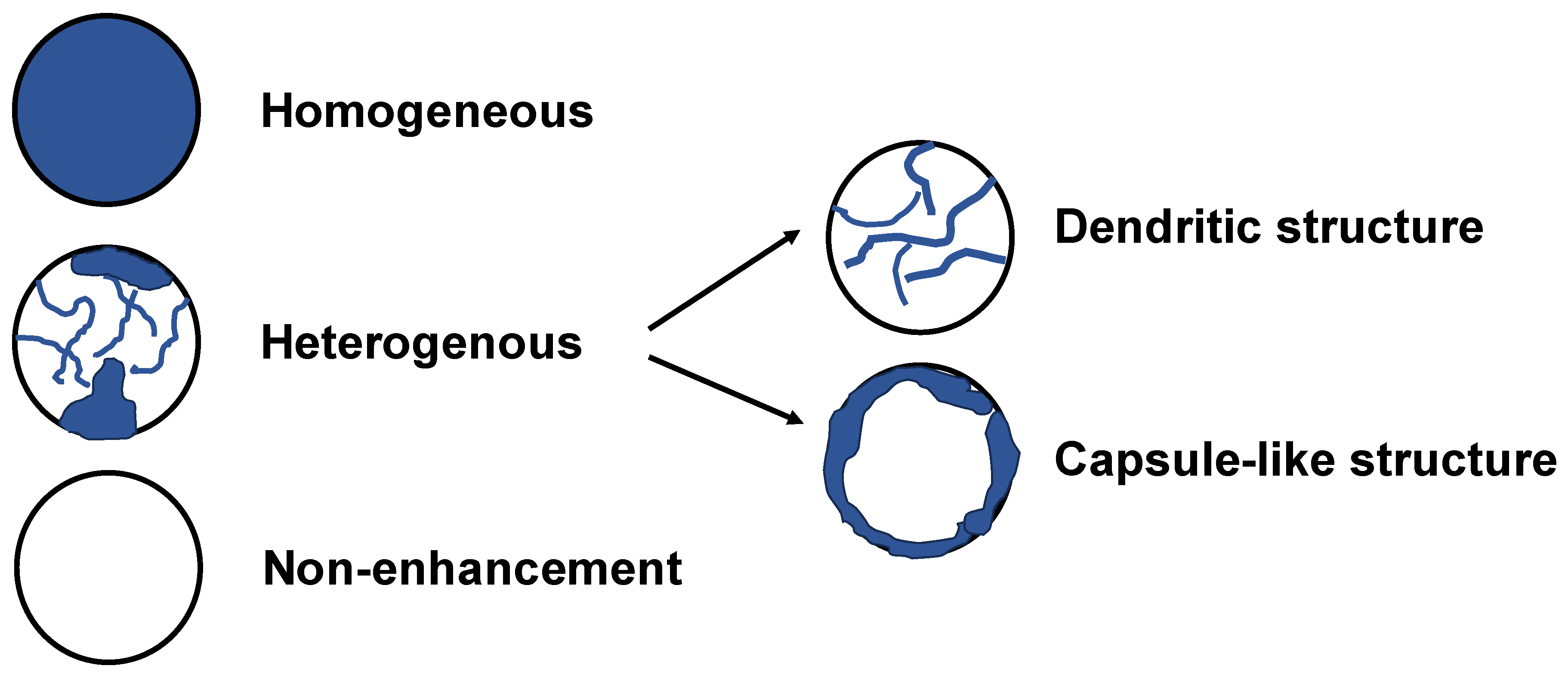

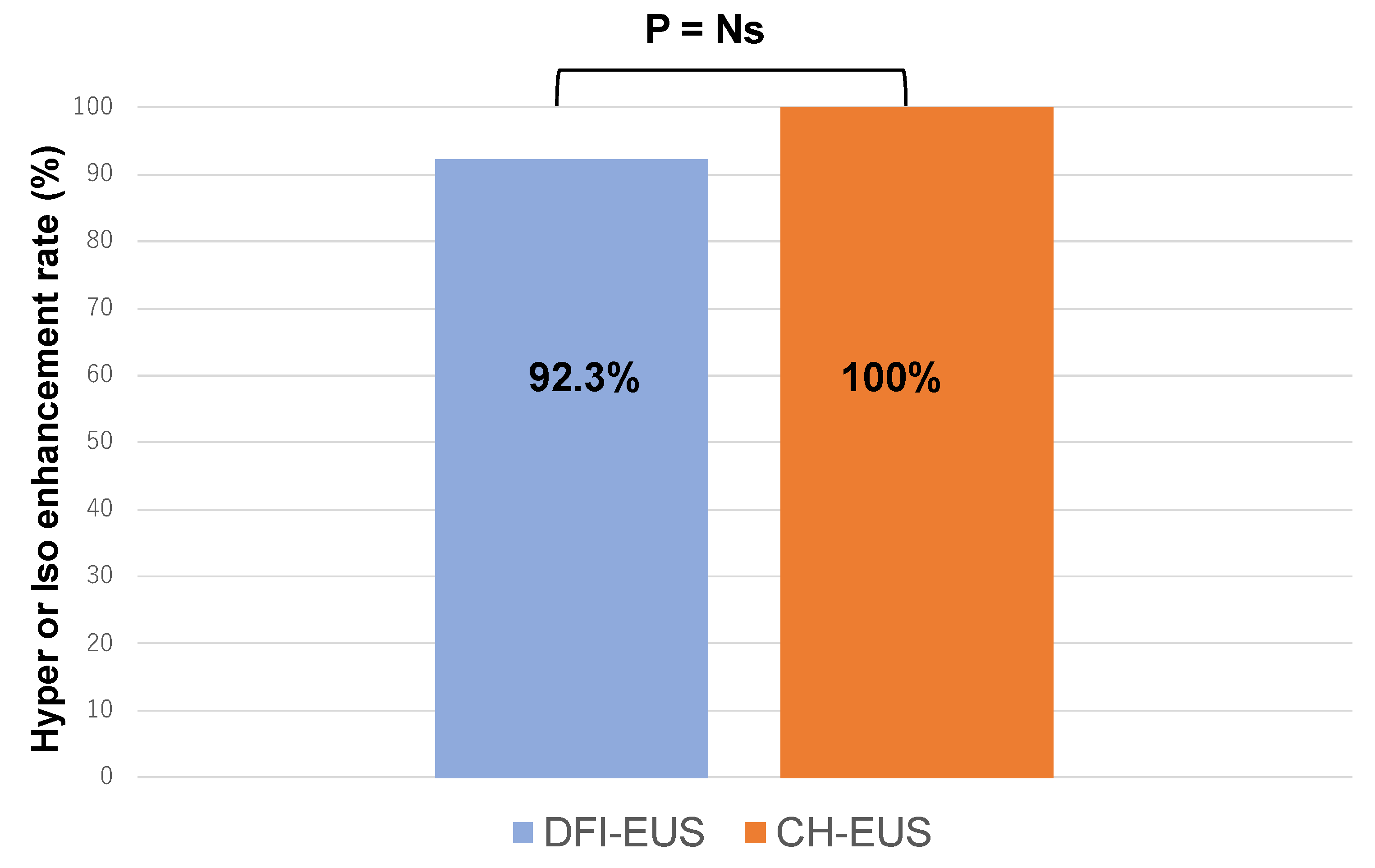

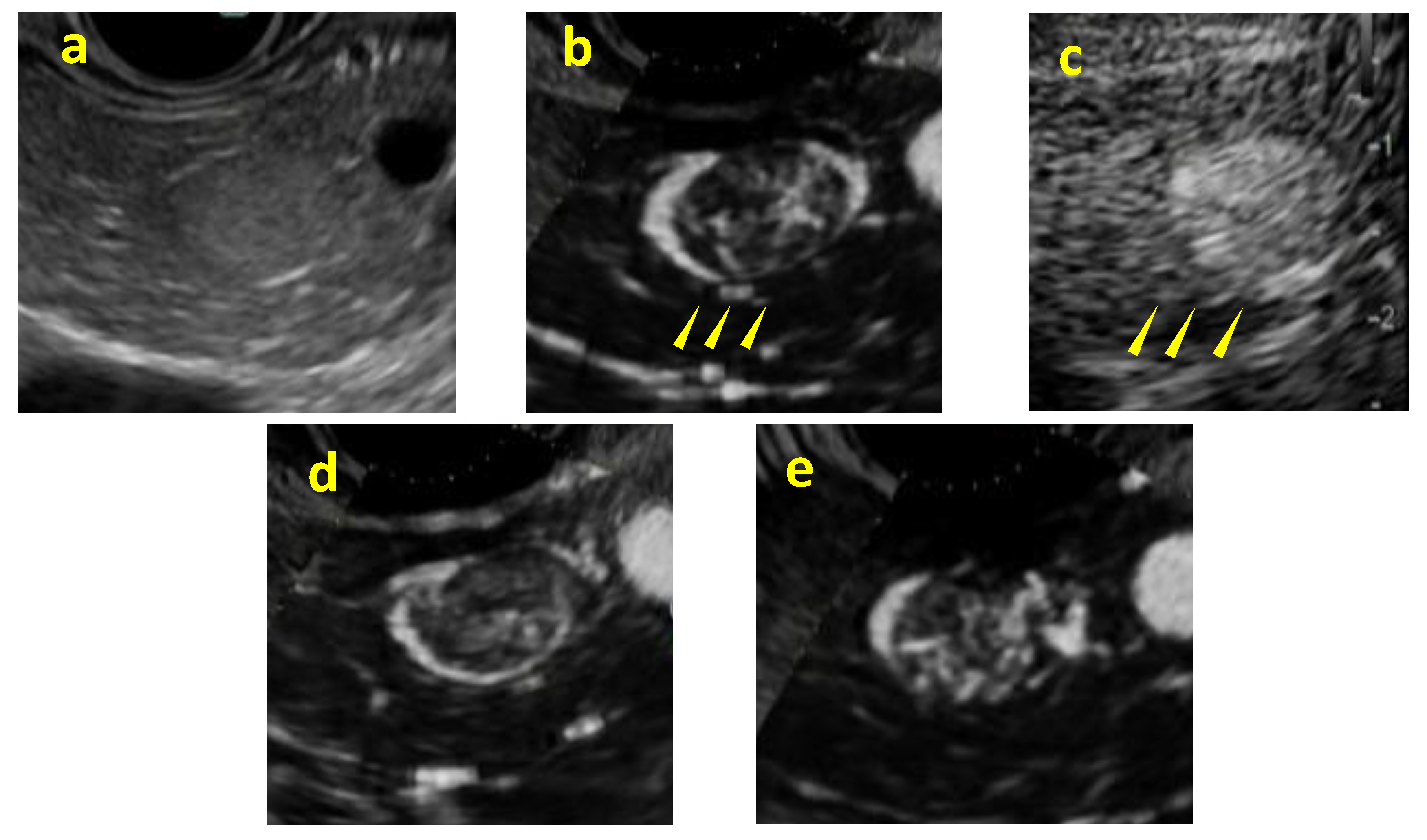

Background/Objectives: Although contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasound (CH-EUS) plays an important role in the ultrasound imaging-based diagnosis of intra-abdominal hypervascular tumors, detective flow imaging EUS (DFI-EUS), which can detect micro-blood flow without using a contrast agent, has recently emerged. In this study, we investigated the usefulness of DFI-EUS for detecting intra-abdominal hypervascular tumors. Methods: Thirteen patients with intra-abdominal hypervascular tumors detected on contrast-enhanced computed tomography who underwent DFI-EUS and CH-EUS were included. The lesions were classified into non-enhancement, hypo-enhancement, iso-enhancement, and hyper-enhancement patterns. Vascular structural patterns were classified as non-enhancement, homogeneous or heterogeneous enhancement. On DFI-EUS, patients who showed heterogeneous enhancement were evaluated for the presence or absence of dendritic and peritumoral capsule-like structures. Contrast patterns, vascular structure patterns, and detection capabilities of DFI-EUS and CH-EUS were examined. Results: The final diagnoses were pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasm in 10 patients (76.9%), gastrointestinal neuroendocrine neoplasm in one patient (7.6%), gastrointestinal stromal tumor in one patient (7.6%), and metastatic pancreatic tumor in one patient (7.6%). The contrast patterns (DFI-EUS vs. CH-EUS) were non-enhancement in 7.7% vs. 0%, iso-enhancement in 15.3% vs. 23.0%, and hyper-enhancement in 76.9% vs. 76.9%. The vascular structure patterns (DFI-EUS vs. CH-EUS) showed a homogeneous enhancement of 0% vs. 100% and a heterogeneous enhancement of 92% vs. 0%. Patients with heterogeneous enhancement on DFI-EUS showed a dendritic structure in 91.6% and capsule-like structures in 75.0% of patients. Conclusions: DFI-EUS and CH-EUS showed comparable iso-enhancement or hyper-enhancement patterns. In contrast, DFI-EUS revealed the characteristic heterogeneous patterns of dendritic and capsular-like vascular structures.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Imaging Equipment

2.2. Image Analysis

2.3. Endpoints

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

| Vascular pattern (%) | |||

| None | Heterogeneous [dendritic structure / capsule-like structure] | Homogeneous | |

| DFI-EUS CH-EUS |

1 (7.7) 0 (0) |

12 (92.3) [11 (91.6) / 9 (75.0)] 0 (0) [0 / 0] |

0 (0) 13 (100) |

| DFI-EUS, Detective flow imaging endoscopic ultrasonography; CH-EUS, Contrast-enhanced harmonic endoscopic ultrasonography | |||

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CH-EUS | contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasound |

| DFI-EUS | detective flow imaging endoscopic ultrasound |

| EUS | endoscopic ultrasound |

| EUS-FNA | endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration |

| GINEN | gastrointestinal neuroendocrine neoplasm |

| GIST | gastrointestinal stromal tumor |

| PNENSMI | pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasmsuperb microvascular imaging |

References

- Shah, M.H.; Goldner, W.S.; Halfdanarson, T.R.; Bergsland, E.; Berlin, J.D.; Halperin, D.; Chan, J.; Kulke, M.H.; Benson, A.B.; Blaszkowsky, L.S.; et al. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Neuroendocrine and Adrenal Tumors, Version 2.2018. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2018, 16, 693-702. [CrossRef]

- Sawhney, M.S.; Debold, S.M.; Kratzke, R.A.; Lederle, F.A.; Nelson, D.B.; Kelly, R.F. Central intranodal blood vessel: a new EUS sign described in mediastinal lymph nodes. Gastrointest Endosc 2007, 65, 602-608. [CrossRef]

- Eloubeidi, M.A.; Wallace, M.B.; Reed, C.E.; Hadzijahic, N.; Lewin, D.N.; Van Velse, A.; Leveen, M.B.; Etemad, B.; Matsuda, K.; Patel, R.S.; et al. The utility of EUS and EUS-guided fine needle aspiration in detecting celiac lymph node metastasis in patients with esophageal cancer: a single-center experience. Gastrointest Endosc 2001, 54, 714-719. [CrossRef]

- Bhutani, M.S.; Hawes, R.H.; Hoffman, B.J. A comparison of the accuracy of echo features during endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration for diagnosis of malignant lymph node invasion. Gastrointest Endosc 1997, 45, 474-479. [CrossRef]

- Das, K.; Kudo, M.; Kitano, M.; Sakamoto, H.; Komaki, T.; Takagi, T.; Yamao, K. Diagnostic value of endoscopic ultrasound-guided directional eFLOW in solid pancreatic lesions. J Med Ultrason (2001) 2013, 40, 211-218. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, G.; Fujita, N.; Noda, Y.; Ito, K.; Horaguchi, J.; Koshida, S.; Kanno, Y.; Ogawa, T.; Masu, K.; Michikawa, Y. Vascular image in autoimmune pancreatitis by contrast-enhanced color-Doppler endoscopic ultrasonography: Comparison with pancreatic cancer. Endosc Ultrasound 2014, 3, S13.

- Xia, Y.; Kitano, M.; Kudo, M.; Imai, H.; Kamata, K.; Sakamoto, H.; Komaki, T. Characterization of intra-abdominal lesions of undetermined origin by contrast-enhanced harmonic EUS (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc 2010, 72, 637-642. [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, Y.; Kato, J.; Ueda, K.; Nakamura, Y.; Kawaji, Y.; Abe, H.; Nuta, J.; Tamura, T.; Itonaga, M.; Yoshida, T.; et al. Contrast-Enhanced Endoscopic Ultrasonography for Pancreatic Tumors. Biomed Res Int 2015, 2015, 491782. [CrossRef]

- Omoto, S.; Takenaka, M.; Kitano, M.; Miyata, T.; Kamata, K.; Minaga, K.; Arizumi, T.; Yamao, K.; Imai, H.; Sakamoto, H.; et al. Characterization of Pancreatic Tumors with Quantitative Perfusion Analysis in Contrast-Enhanced Harmonic Endoscopic Ultrasonography. Oncology 2017, 93 Suppl 1, 55-60. [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, N.; Kato, H.; Tomoda, T.; Matsumoto, K.; Sakakihara, I.; Noma, Y.; Horiguchi, S.; Harada, R.; Tsutsumi, K.; Hori, K.; et al. Contrast-enhanced harmonic endoscopic ultrasonography with time-intensity curve analysis for intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. Endoscopy 2016, 48, 26-34. [CrossRef]

- Kamata, K.; Kitano, M.; Omoto, S.; Kadosaka, K.; Miyata, T.; Yamao, K.; Imai, H.; Sakamoto, H.; Harwani, Y.; Chikugo, T.; et al. Contrast-enhanced harmonic endoscopic ultrasonography for differential diagnosis of pancreatic cysts. Endoscopy 2016, 48, 35-41. [CrossRef]

- Fujita, M.; Itoi, T.; Ikeuchi, N.; Sofuni, A.; Tsuchiya, T.; Ishii, K.; Kamada, K.; Umeda, J.; Tanaka, R.; Tonozuka, R.; et al. Effectiveness of contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasound for detecting mural nodules in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas and for making therapeutic decisions. Endosc Ultrasound 2016, 5, 377-383. [CrossRef]

- Harima, H.; Kaino, S.; Shinoda, S.; Kawano, M.; Suenaga, S.; Sakaida, I. Differential diagnosis of benign and malignant branch duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm using contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasonography. World J Gastroenterol 2015, 21, 6252-6260. [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, Y.; Yoshikawa, T.; Yamazaki, H.; Kawaji, Y.; Tamura, T.; Hatamaru, K.; Itonaga, M.; Ashida, R.; Ida, Y.; Maekita, T.; et al. A Novel Endoscopic Ultrasonography Imaging Technique for Depicting Microcirculation in Pancreatobiliary Lesions without the Need for Contrast-Enhancement: A Prospective Exploratory Study. Diagnostics (Basel) 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Nihei, S.; Kurita, Y.; Hasegawa, S.; Hosono, K.; Kobayashi, N.; Kubota, K.; Nakajima, A. Detective flow imaging endoscopic ultrasound for localizing pancreatic insulinomas that are undetectable with other imaging modalities. Endoscopy 2024, 56, E342-e343. [CrossRef]

- Miwa, H.; Sugimori, K.; Yonei, S.; Yoshimura, H.; Endo, K.; Oishi, R.; Funaoka, A.; Tsuchiya, H.; Kaneko, T.; Numata, K.; et al. Differential Diagnosis of Solid Pancreatic Lesions Using Detective Flow Imaging Endoscopic Ultrasonography. Diagnostics (Basel) 2024, 14. [CrossRef]

- Mulqui, M.V.; Caillol, F.; Ratone, J.P.; Hoibian, S.; Dahel, Y.; Meunier, É.; Archimbaud, C.; Giovannini, M. Detective flow imaging versus contrast-enhanced EUS in solid pancreatic lesions. Endosc Ultrasound 2024, 13, 248-252. [CrossRef]

- Rockall, A.G.; Reznek, R.H. Imaging of neuroendocrine tumours (CT/MR/US). Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007, 21, 43-68. [CrossRef]

- Khashab, M.A.; Yong, E.; Lennon, A.M.; Shin, E.J.; Amateau, S.; Hruban, R.H.; Olino, K.; Giday, S.; Fishman, E.K.; Wolfgang, C.L.; et al. EUS is still superior to multidetector computerized tomography for detection of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Gastrointest Endosc 2011, 73, 691-696. [CrossRef]

- Kurita, Y.; Hara, K.; Kobayashi, N.; Kuwahara, T.; Mizuno, N.; Okuno, N.; Haba, S.; Yagi, S.; Hasegawa, S.; Sato, T.; et al. Detection rate of endoscopic ultrasound and computed tomography in diagnosing pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms including small lesions: A multicenter study. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2022, 29, 950-959. [CrossRef]

- Bansal, R.; Tierney, W.; Carpenter, S.; Thompson, N.; Scheiman, J.M. Cost effectiveness of EUS for preoperative localization of pancreatic endocrine tumors. Gastrointest Endosc 1999, 49, 19-25. [CrossRef]

- Akerström, G.; Hellman, P. Surgery on neuroendocrine tumours. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007, 21, 87-109. [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, T.; Stölzel, U.; Bäder, M.; Koppenhagen, K.; Hamm, B.; Buhr, H.; Riecken, E.O.; Wiedenmann, B. Endoscopic ultrasonography and somatostatin receptor scintigraphy in the preoperative localisation of insulinomas and gastrinomas. Gut 1996, 39, 562-568. [CrossRef]

- Ginès, A.; Vazquez-Sequeiros, E.; Soria, M.T.; Clain, J.E.; Wiersema, M.J. Usefulness of EUS-guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) in the diagnosis of functioning neuroendocrine tumors. Gastrointest Endosc 2002, 56, 291-296. [CrossRef]

- Kann, P.H.; Ivan, D.; Pfützner, A.; Forst, T.; Langer, P.; Schaefer, S. Preoperative diagnosis of insulinoma: low body mass index, young age, and female gender are associated with negative imaging by endoscopic ultrasound. Eur J Endocrinol 2007, 157, 209-213. [CrossRef]

- Patel, K.K.; Kim, M.K. Neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas: endoscopic diagnosis. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2008, 24, 638-642. [CrossRef]

- Lu, R.; Meng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, W.; Wang, X.; Jin, M.; Guo, R. Superb microvascular imaging (SMI) compared with conventional ultrasound for evaluating thyroid nodules. BMC Med Imaging 2017, 17, 65. [CrossRef]

- Bakdik, S.; Arslan, S.; Oncu, F.; Durmaz, M.S.; Altunkeser, A.; Eryilmaz, M.A.; Unlu, Y. Effectiveness of Superb Microvascular Imaging for the differentiation of intraductal breast lesions. Med Ultrason 2018, 20, 306-312. [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Mu, J.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, L.; Xin, X. The value of superb microvascular imaging in differentiating benign renal mass from malignant renal tumor: a retrospective study. Br J Radiol 2018, 91, 20170601. [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Lu, J.; Jin, C.; Chen, Y.; Chen, S.; Guo, G.; Gong, X. Diagnostic Value of Superb Microvascular Imaging in Differentiating Benign and Malignant Breast Tumors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Diagnostics (Basel) 2022, 12. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Lee, J.Y.; Yoon, R.G.; Kim, J.H.; Hong, H.S. The Value of Microvascular Imaging for Triaging Indeterminate Cervical Lymph Nodes in Patients with Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma. Cancers (Basel) 2020, 12. [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | n= 13 |

| Median age, years (range) | 72 (30-80) |

| Sex, male (%) | 4 (30.7) |

| Tumor size (mm) (%) Median (range) 5-10 mm 10-20 mm >20 mm |

26.0 (7-37) 3 (23.0) 7 (53.8) 3 (23.0) |

| Pathological diagnosis (%) PNEN (Grade1 / Grade2) (Non-function/ insulinoma) GINEN (Grade1, non-function) GIST Metastasis |

10 (76.9) 7 (53.8) / 3 (23.0) 8 (61.5) / 2 (15.4pp) 1 (7.6) 1 (7.6) 1 (7.6) |

| Enhancement pattern (%) | ||||

| Non-enhancement | Hypo-enhancement | Iso-enhancement | Hyper-enhancement | |

| DFI-EUS CH-EUS |

1 (7.7) 0 (0) |

0 (0) 0 (0) |

2 (15.3) 3 (23.0) |

10 (76.9) 10 (76.9) |

| DFI-EUS, Detective flow imaging endoscopic ultrasound; CH-EUS, Contrast-enhanced harmonic endoscopic ultrasonography | ||||

| Vascular pattern (%) | |||

| None | Heterogeneous [dendritic structure / capsule-like structure] | Homogeneous | |

| DFI-EUS CH-EUS |

1 (7.7) 0 (0) |

12 (92.3) [11 (91.6) / 9 (75.0)] 0 (0) [0 / 0] |

0 (0) 13 (100) |

| DFI-EUS, Detective flow imaging endoscopic ultrasonography; CH-EUS, Contrast-enhanced harmonic endoscopic ultrasonography | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).