1. Introduction

Pharmaceutical residues, particularly tetracycline hydrochloride (TC), have become critical contaminants of emerging concern (CECs) due to their increasing presence in aquatic environments, driven by improper disposal and inefficiencies in conventional water treatment methods [

1]. In Brazil, the pharmaceutical market generated R

$20 billion in 2021, with significant amounts of medications discarded improperly, contributing to the alarming estimate of 14,000 tons of expired drugs discarded annually [

2,

3]. These residues are frequently found in groundwater and wastewater, highlighting the need for effective remediation technologies [

4].

TC, a common antibiotic used in healthcare and aquaculture, poses significant environmental challenges due to its recalcitrant nature and low degradation potential. About 50–80% of administered TC remains unmetabolized, entering aquatic systems and promoting antibiotic resistance [

5,

6]. Among wastewater treatment methods, adsorption has gained attention for its cost-effectiveness and efficiency. Bentonite, a natural clay mineral, shows promise as an adsorbent due to its high surface area and cation exchange capacity. Acid treatment of bentonite enhances its adsorptive properties by increasing porosity and removing surface impurities, improving contaminant removal [

7,

8].

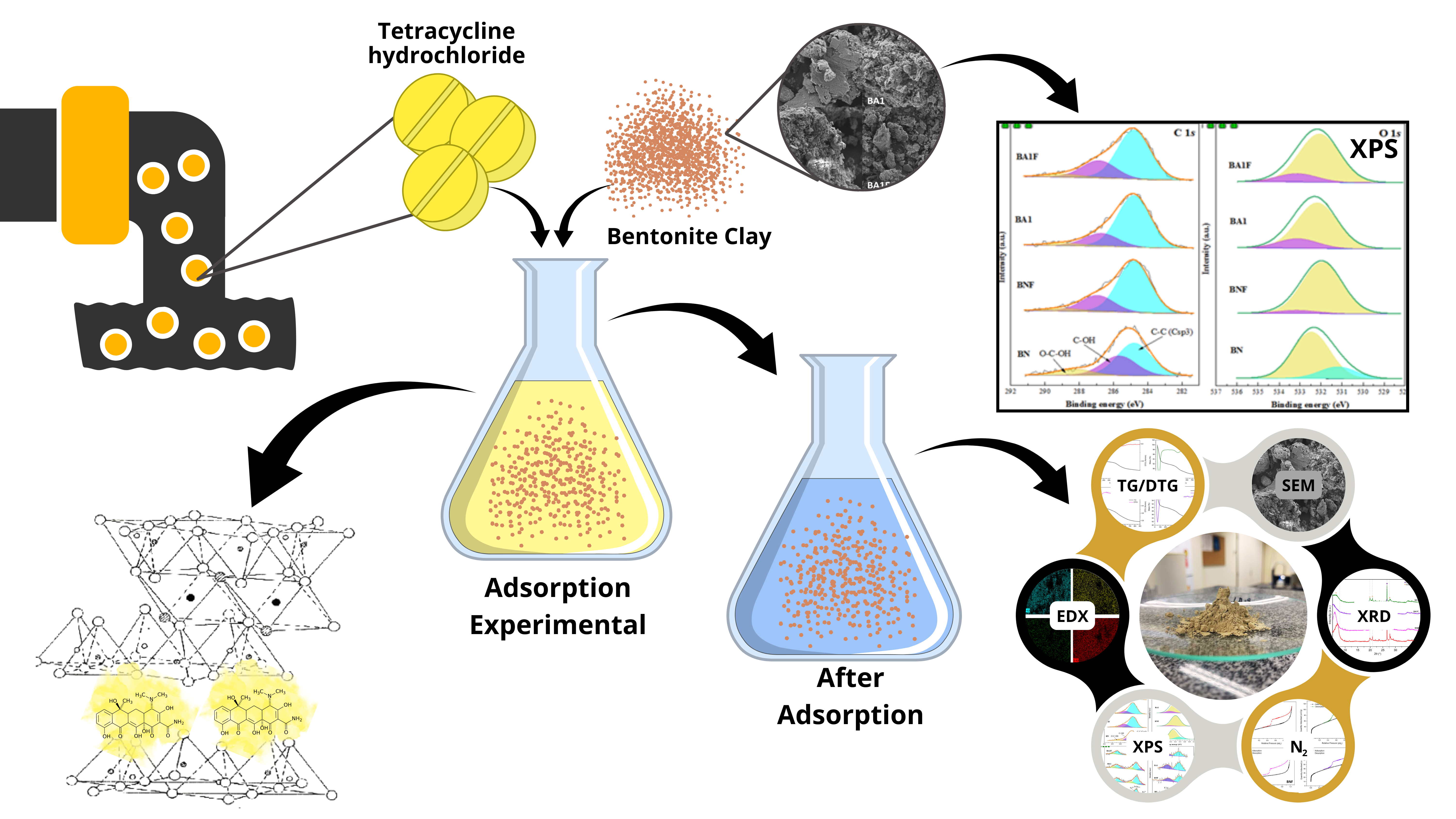

This study explores the effectiveness of natural (BN) and acid-treated (BA1) bentonite for TC removal from aqueous solutions, using various characterization techniques (XRF, XRD, XPS, SEM/TEM-EDS) and adsorption isotherms. The results provide insights into the mechanisms of adsorption and contribute to the development of sustainable water treatment technologies to mitigate pharmaceutical contamination.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Modification of Bentonite

In this study, natural bentonite (BN) was utilized alongside its acid-modified form (BA1) to evaluate its adsorption performance. The modification process involved treating BN with hydrochloric acid (HCl, 37%) at a concentration of 1 mol·L⁻¹. The acid solution was combined with BN under continuous stirring at 60 °C for 4 hours to enhance its adsorptive properties. Following the acid treatment, the material underwent vacuum filtration to separate the solid phase, followed by thorough washing to neutralize the pH. The treated material was then dried in an oven at 70 °C for 12 hours to ensure complete removal of moisture. The resultant acid-modified bentonite sample was designated as BA1 and selected for subsequent adsorption studies based on superior performance observed in preliminary evaluations.

2.2. Characterization of Bentonite

The materials, without drug (BN and BA1) and with drug (BNF and BA1F), were characterized using a variety of advanced analytical techniques. X-ray diffraction (XRD) was performed with a Bruker D2 Phaser instrument to identify the crystalline phases, while elemental composition was determined using X-ray fluorescence (XRF) with a Bruker S2 Ranger. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was used to assess thermal stability and decomposition behavior, conducted on a NETZSCH TG 209 F3 Tarsus under a nitrogen atmosphere, with a heating rate of 5°C·min⁻¹.

The presence of functional groups in the bentonite structure was identified through Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) using a Shimadzu IRAffinity-1 spectrophotometer, with spectra recorded in the 4000–700 cm⁻¹ wavelength range. Morphological and elemental analysis was carried out using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) on a Carl Zeiss Auriga 40 instrument, equipped with a Bruker XFlash 410-M detector. High-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) was conducted with a TALOS F200x instrument, providing detailed imaging at 200 kV in scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) mode, with a high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) detector.

Surface area and pore structure were analyzed using nitrogen adsorption/desorption isotherms at -196 °C, with measurements taken on a Micromeritics ASAP 2420 system. Lastly, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was performed with a PHI 5700 spectrometer using non-monochromatic AlKα radiation to examine surface chemistry and elemental composition.

2.3. Preparation of TC Solutions

To simulate a contaminated aqueous effluent, a sample of tetracycline hydrochloride (TC) was utilized. Starting with a 500 mg.L-1 solution of TC, kinetic, equilibrium, and thermodynamic isotherm measurements were conducted with an initial concentration of 20 mg.L-1. After the adsorption tests, the remaining drug concentration was measured using UV-Vis spectrophotometry (Shimadzu 1800) at a wavelength of 360 nm to determine the final TC concentration.

2.4. Adsorption kinetics Studies

The adsorption mechanism of TC was investigated by evaluating the kinetic parameters over a range of contact times. For these experiments, 0.3 g of adsorbent was added to 25 mL of a 500 mg·L⁻¹ THC solution. The tests were carried out at 25 °C (room temperature) under constant stirring at 150 rpm, with sampling intervals ranging from 1 to 1440 minutes (11 data points). Residual TC concentrations were quantified using UV-Vis spectrophotometry.

The adsorption capacity and kinetic behavior were analyzed using multiple kinetic models, including the pseudo-first-order, pseudo-second-order, Elovich, and Boyd film diffusion models, described by equations 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively. Data fitting and model comparisons were conducted using Excel and Origin 2019b software to identify the most suitable kinetic mechanism governing the adsorption process.

In the kinetic models applied to analyze the adsorption process, qt represents the amount of tetracycline hydrochloride adsorbed per gram of adsorbent at time t, while qe denotes the adsorption capacity of the material at equilibrium, both expressed in mg·g⁻¹. The pseudo-first-order rate constant, k1 (L·min⁻¹), characterizes the rate of adsorption as proportional to the difference between qe and qt. Similarly, the pseudo-second-order rate constant, k2 (g·mg⁻¹·min⁻¹), reflects the chemisorption kinetics, often associated with valence forces or electron exchange. The parameter β (g·mg⁻¹) is related to the activation energy for chemical adsorption and provides information about the extent of surface coverage. Additionally, α (mg·g⁻¹·min⁻¹) represents the initial adsorption rate, describing the adsorption behavior as t → 0. These parameters, obtained by fitting experimental data to the kinetic models, offer detailed insights into the adsorption dynamics and the mechanisms governing the process.

2.5. Adsorption Equilibrium Study

Adsorption isotherms were determined using tetracycline hydrochloride solutions with concentrations ranging from 25 to 500 mg·L⁻¹. For each experiment, 0.3 g of natural or acid-treated bentonite was added to 25 mL of the solution in 250 mL Erlenmeyer flasks. The mixtures were agitated at 150 rpm for 30 minutes to ensure interaction between the adsorbent and the adsorbate. After the adsorption process, the solid and liquid phases were separated via centrifugation at 3000 rpm for 20 minutes. The experimental data were analyzed using non-linear forms of the Langmuir, Freundlich, Sips, and Temkin isotherm models, represented by Equations 5, 6, 7, and 8, respectively. These models were employed to describe the equilibrium behavior of tetracycline adsorption and to evaluate the adsorption capacity and the nature of the interactions between the adsorbent and the adsorbate.

where

Ce is the equilibrium concentration (mg.L

-1);

qe is the amount of adsorbed dyes (mg.g

-1);

qm is the maximum adsorption capacity;

KL,

KF,

Ks and

Kt are the Langmuir, Freundlich, Sips and Temkin constants, respectively; and

n Sips coefficient.

2.6. Influence of pH

To analyze the effect of pH on drug adsorption, 0.1 mol.L-1 buffer solutions were used to test pH levels of 2.5, 4.5, 6.5, and 8.5 with a 300 ppm drug solution. After the adsorption experiments, the final concentration of tetracycline was determined using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Shimadzu 1800) at a wavelength of 360 nm.

3. Results

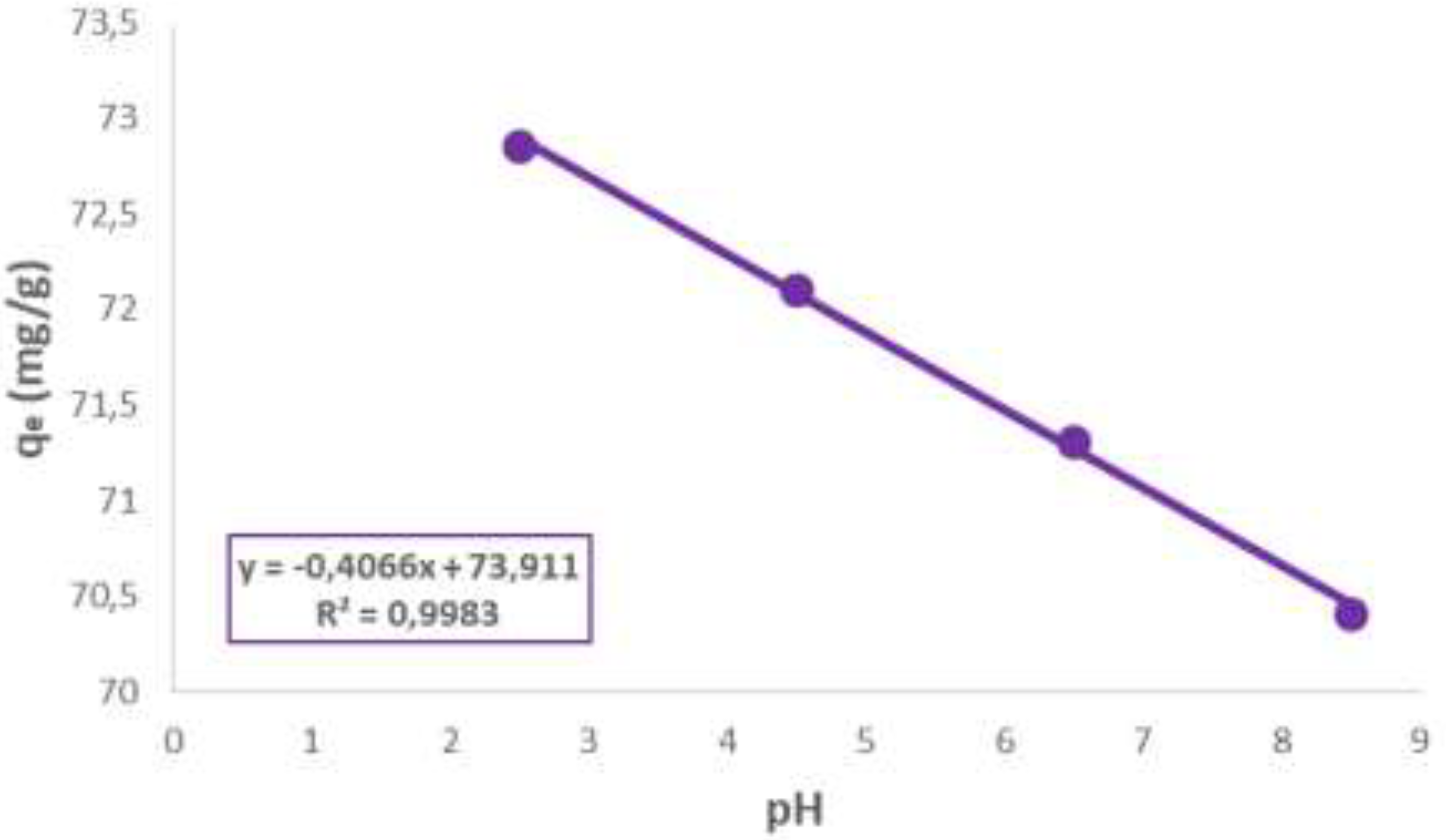

3.1. Influence of pH

The results presented in

Figure 1 indicate that natural bentonite exhibits high tetracycline hydrochloride (TC) adsorption at pH 2.5, which progressively decreases as the pH increases. These findings are consistent with previous studies reporting tetracycline adsorption on natural clays [

4]. At acidic pH, TC adsorption on natural clay is primarily driven by electrostatic interactions, with cation exchange being the dominant mechanism. However, as the pH of the solution increases and species of TC with lower affinity emerge, adsorption may occur via other mechanisms, such as hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic interactions, or the formation of complexes with the surface groups of the clay mineral [

9].

3.2. X-ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy (XRF)

The inorganic elements in natural bentonite (BN) and acid-treated bentonite (BA1) are shown in

Table 1. Silicon (Si) had the highest content in all samples. Aluminum (Al) and silicon are the primary components of bentonite, with the high presence of Al expected due to its montmorillonite content. Cristobalite impurities are associated with silica (SiO₂). Bentonite contained 2.73% Ca and 0.87% Na, both of which were leached out after acid treatment, classifying it as Ca-bentonite. Additionally, potassium (K) and magnesium (Mg) cations were reduced after treatment, confirming the effectiveness of the acid modification [

10,

11].

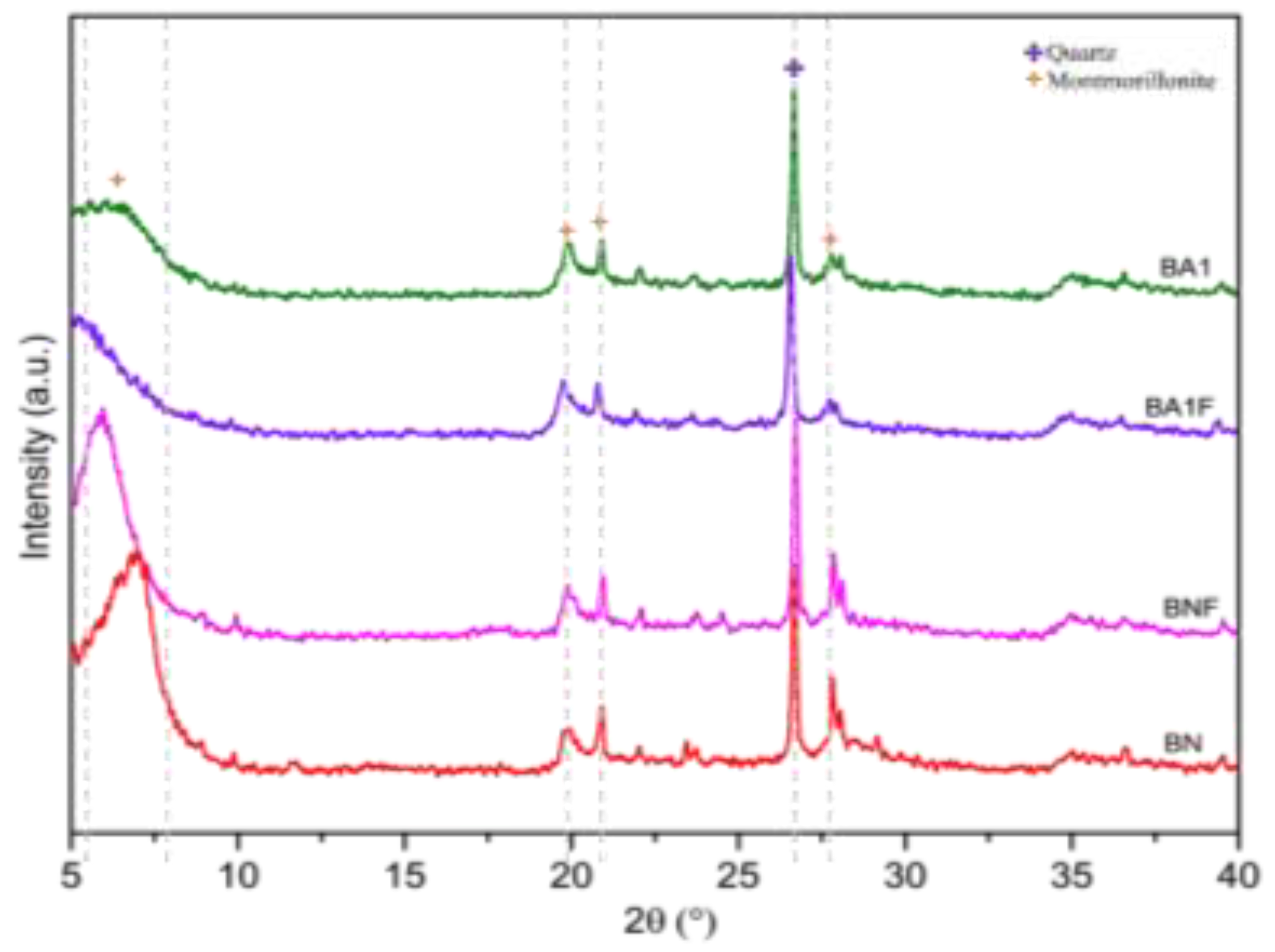

3.3. X-ray Diffraction (XRD)

The XRD (

Figure 2) pattern of the studied clay shows peaks corresponding to montmorillonite, quartz, and feldspar. The natural calcium bentonite is primarily composed of montmorillonite, with characteristic peaks at d

001 = 14.29 Å and d

020 = 4.49 Å, and a basal spacing of d

001 = 39.8 Å, indicating a calcium dominance and classifying the clay as Ca-bentonite. Other peaks correspond to quartz and feldspar impurities. After acid treatment, the XRD pattern of activated bentonite shows broader peaks and increased intensity, suggesting partial disruption of its layered structure and a decrease in crystallinity. The increased quartz peak at around 26° 2θ indicates that quartz, present as an impurity, was not destroyed during activation [

12,

13].

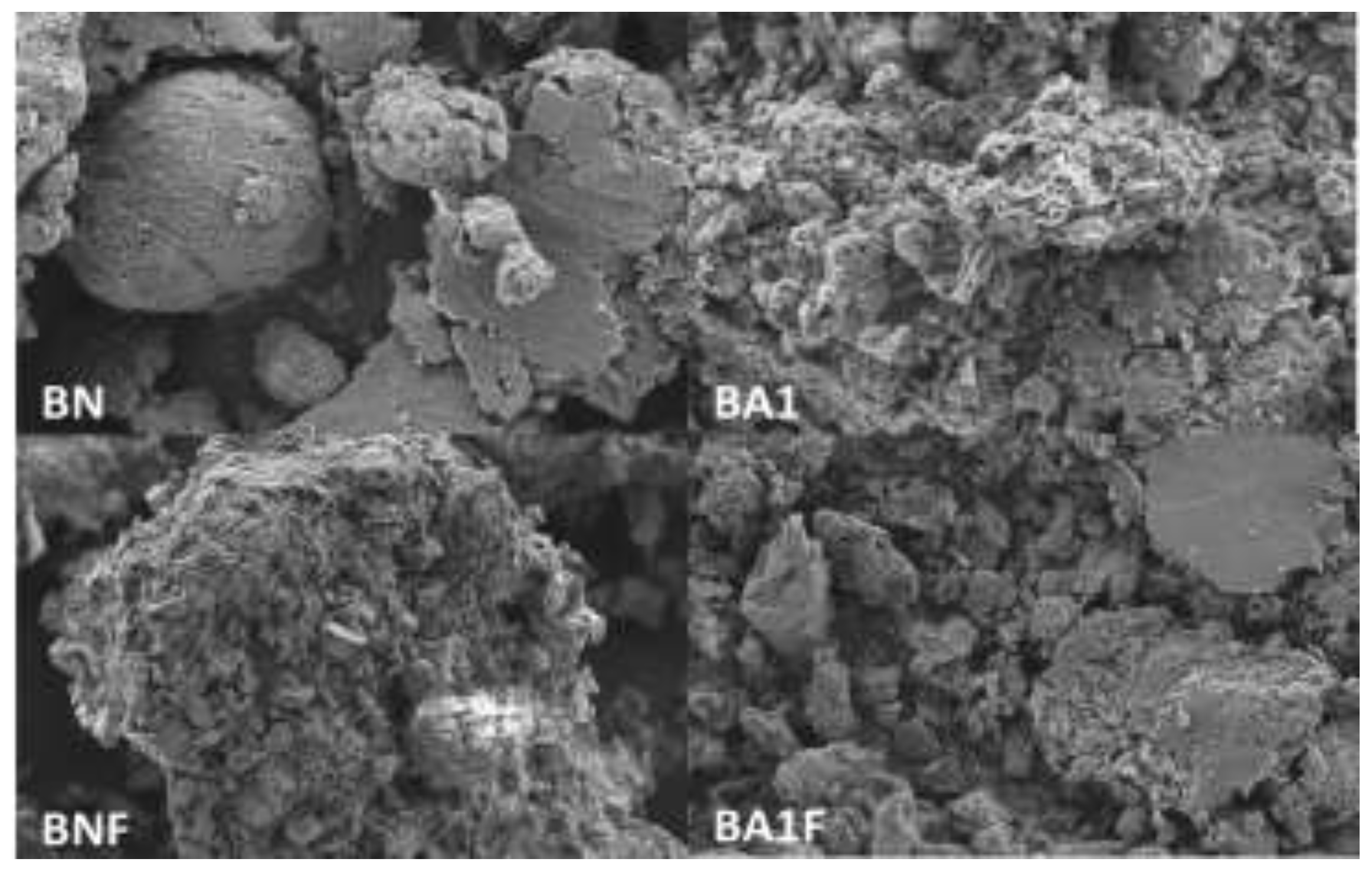

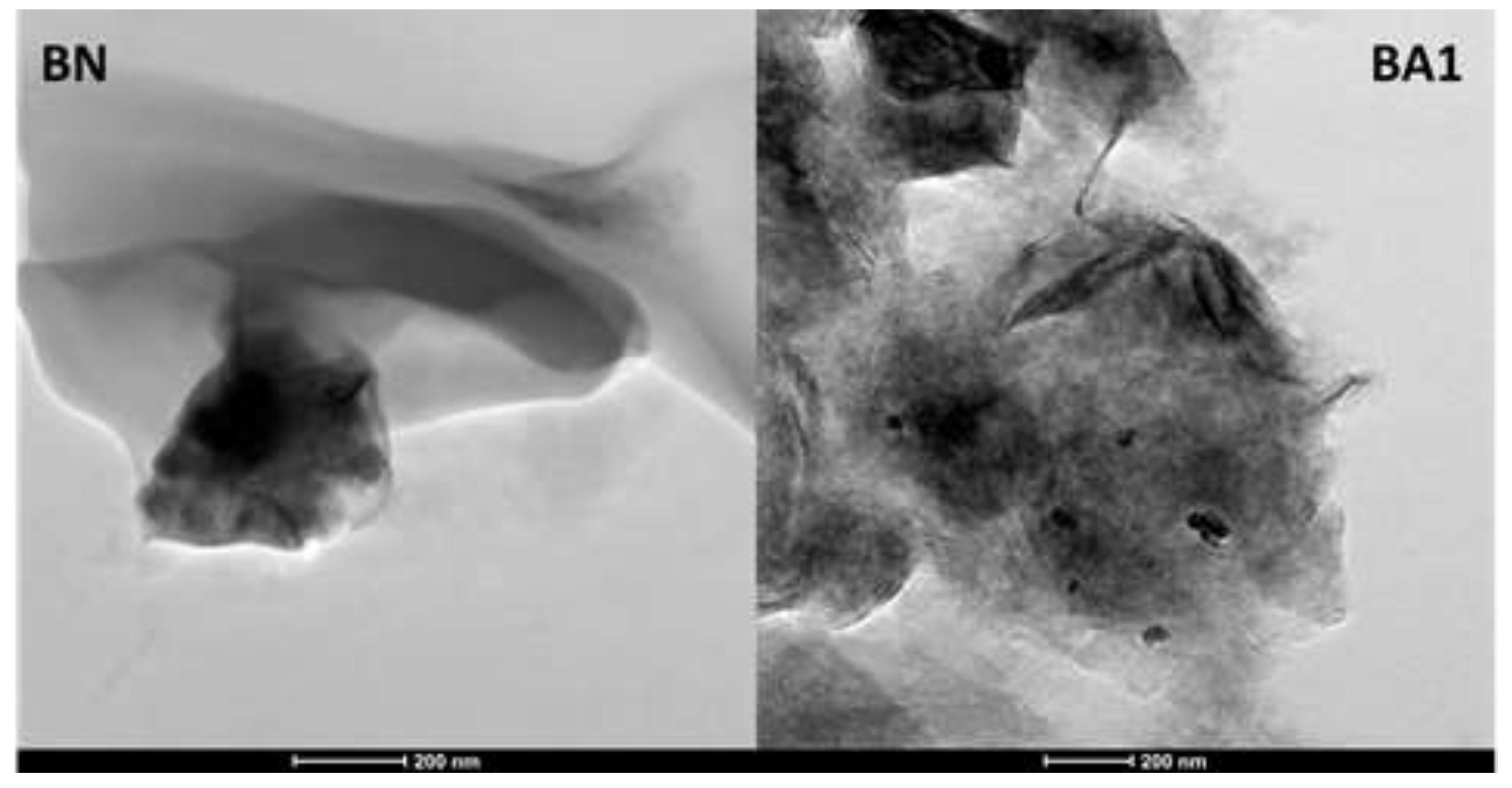

3.4. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) Coupled with Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS) and High-Resolution Transmission Electron Microscopy (HRTEM)

As reported in other studies [

14], bentonite exhibits amorphicity due to its unclear morphology at the nanometric scale. The particle sizes vary for each sample due to differences in the treatment and composition of each. The SEM-EDS image shows some agglomerations in each sample, which may be influenced by the particle size, as shown in

Figure 3.

The HRTEM images (

Figure 4) of natural bentonite (BN) and acid-treated bentonite (BA1) reveal structures with irregular shapes, resembling stacked spheres, as previously reported by [

15].

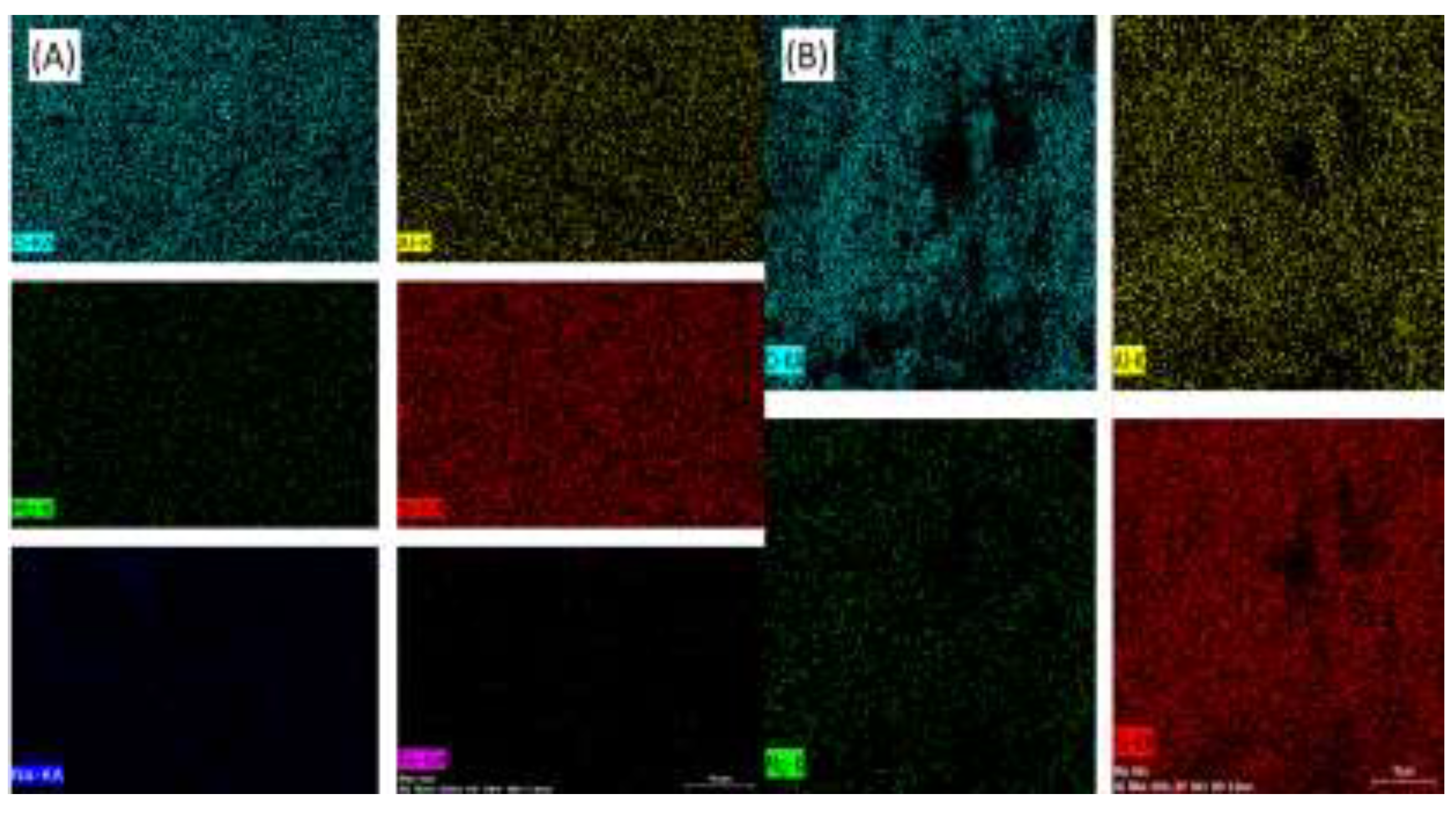

The images (

Figure 5) from the EDS mapping analysis confirm the presence and dispersion of atomic components of the clay minerals on the surfaces of the materials. Similar to the results from the XRF analysis, the data indicate that the composition is primarily composed of aluminum and silicon atoms.

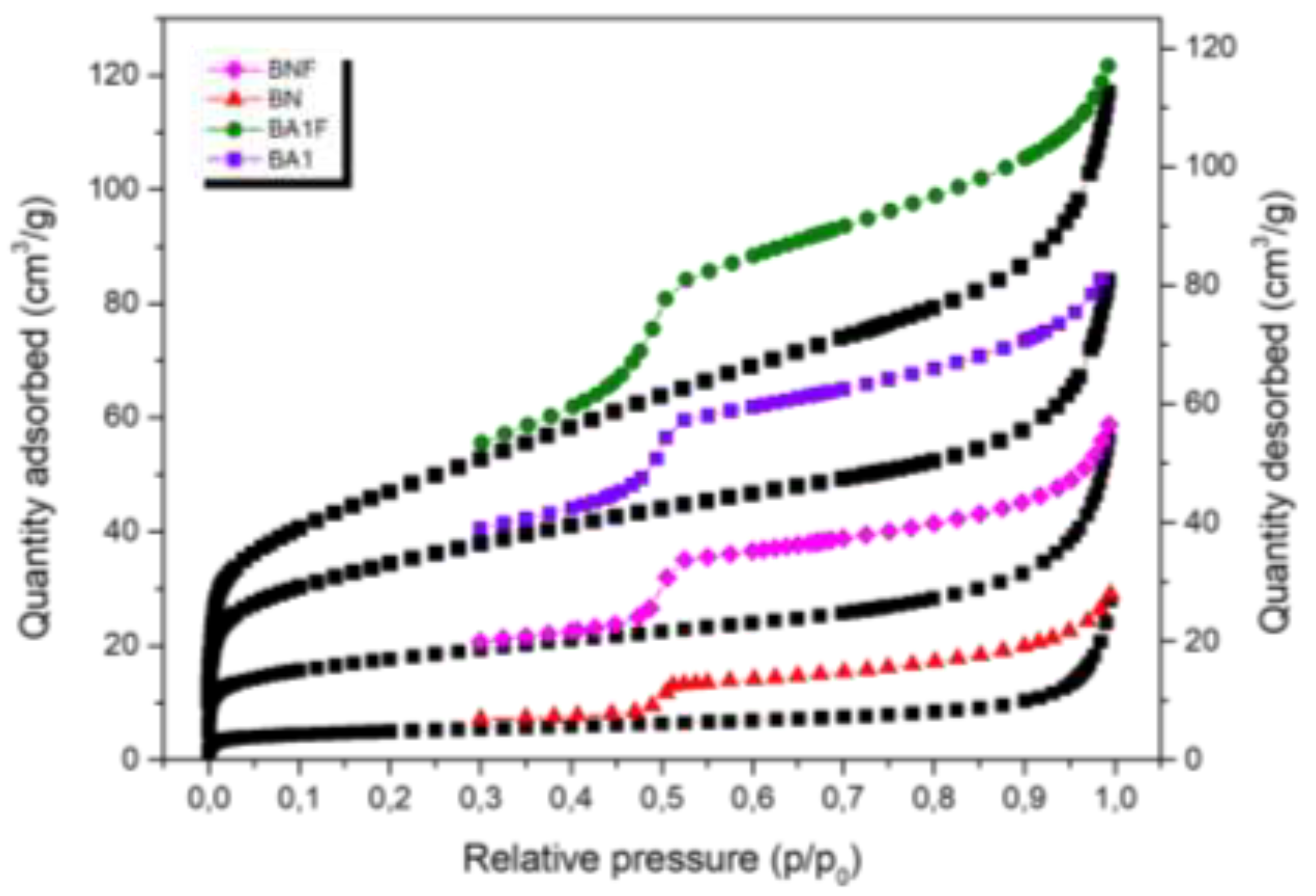

3.5. N2 Isotherm

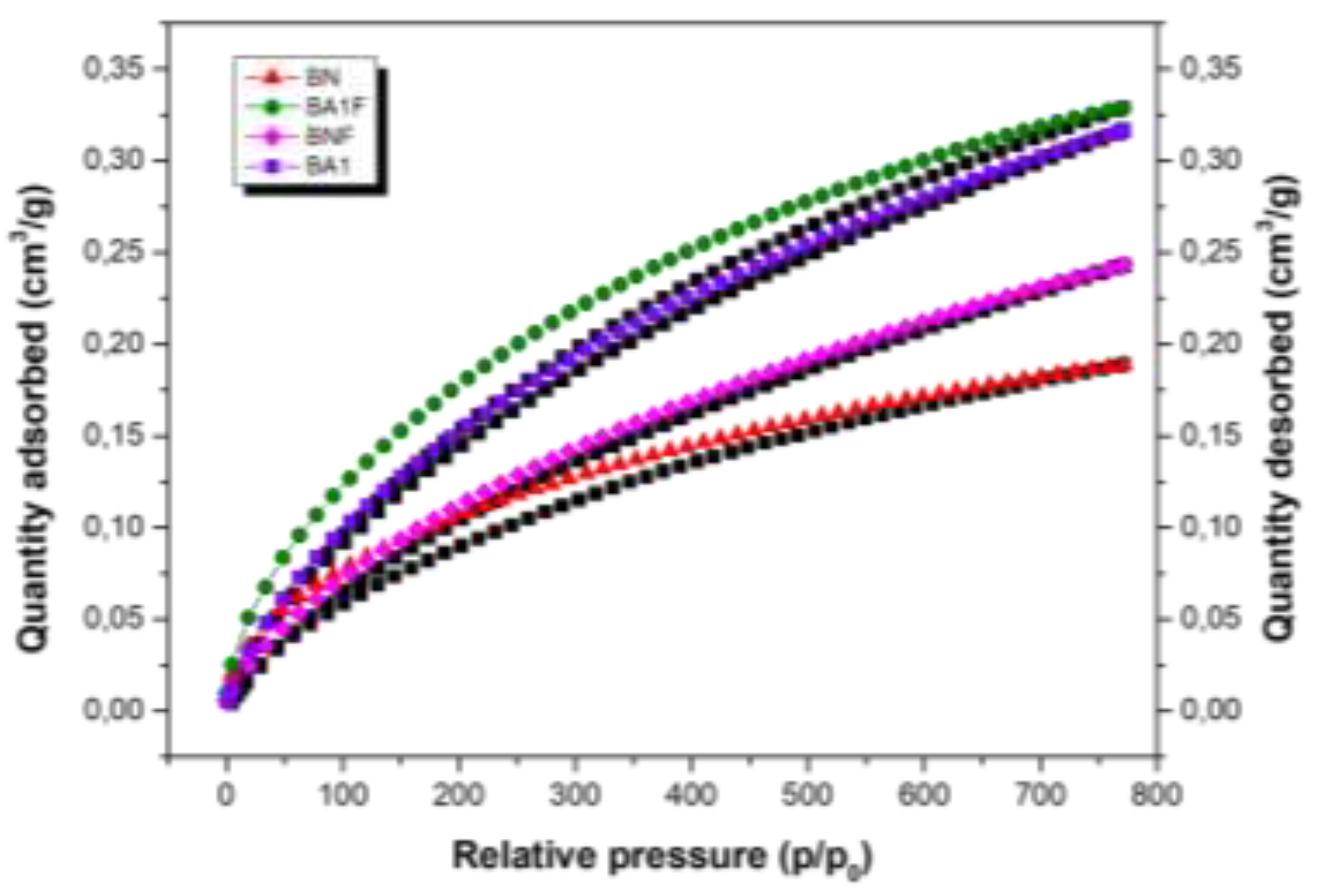

The N

2 adsorption-desorption isotherms at -196 °C for BN, BNF, BA1, and BA1F samples are shown in

Figure 6. According to IUPAC classification, these isotherms are of type IV with H2 hysteresis loops, with P/P

0 > 0.9. In the low P/P

0 region (P/P0 < 0.1), all samples exhibited a small amount of N

2 adsorption, suggesting that there is almost no microporosity in the acid-activated clays. On the other hand, N

2 adsorption increases significantly in the high P/P

0 region, indicating the presence of mesopores in these clays [

16]. Acid treatment increased the specific surface area (BET), as shown in

Table 1, opening structural channels during leaching, which dissolved octahedral cations on the adsorbent surfaces. These results are summarized in

Table 2 [

17].

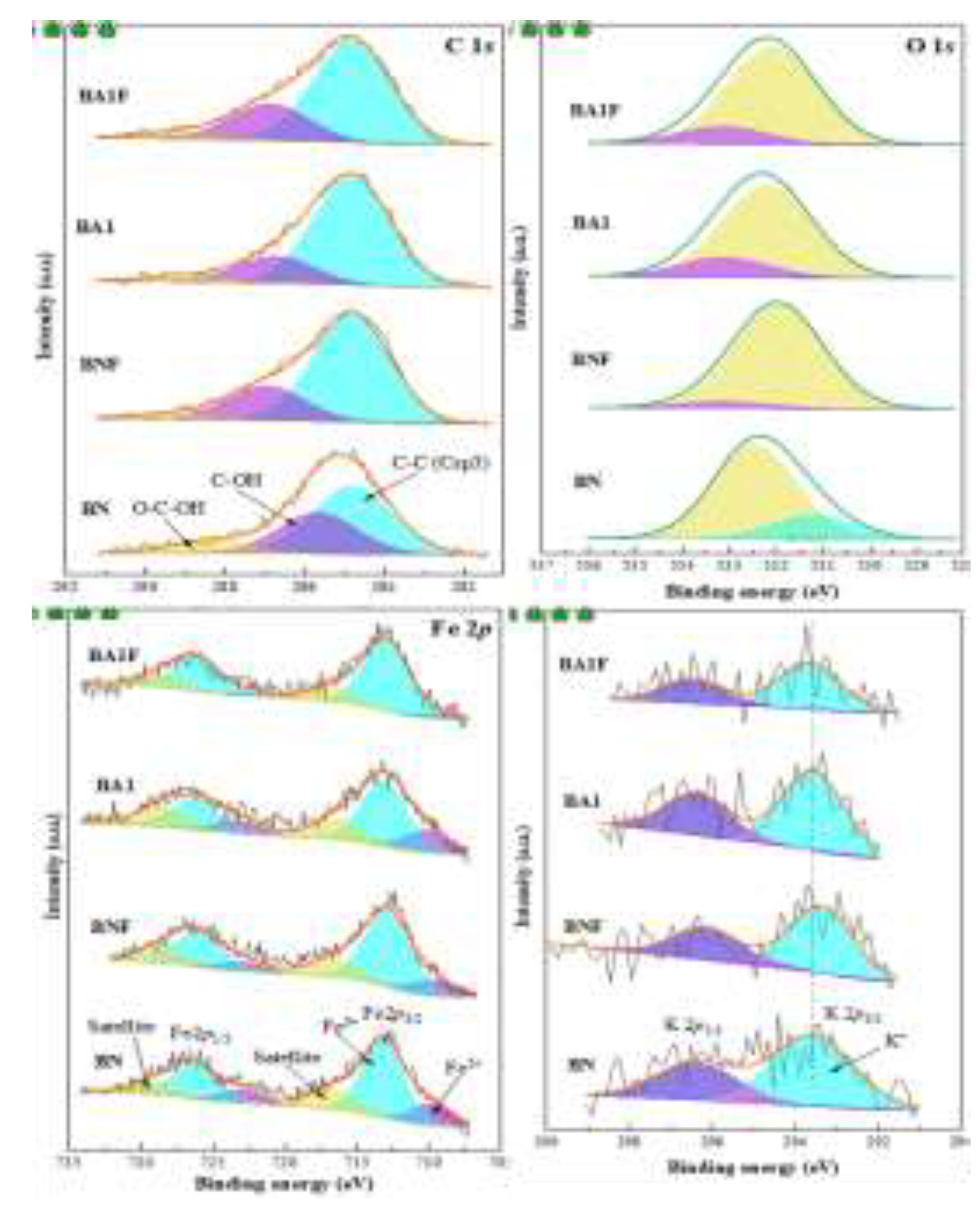

3.6. X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy

The deconvolution of XPS spectra, shown in

Figure 7, is closely linked to the materials' capacity to adsorb tetracycline. The adsorption is strongly influenced by interactions between the functional groups on the adsorbents and the antibiotic molecules. In the C 1

s spectra, BA1F, BA1, and BNF exhibit C–C/C–H (C

sp³) and oxygenated groups, such as C–OH and O–C=O, which are essential for tetracycline adsorption. These groups interact with the antibiotic’s amino and oxygenated functionalities through hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonds, and van der Waals forces, enhancing the adsorption capacity of the materials [

18].

The O 1

s spectra show that all materials contain oxygen bonded to carbonyl (C=O) and hydroxyl (C–O) groups, which are also important for adsorption as they can form hydrogen bonds with tetracycline. BN, with higher intensity in oxygen peaks, exhibits stronger interactions with tetracycline, leading to more efficient adsorption [

19,

20]. Additionally, the presence of iron oxides, particularly Fe²⁺ and Fe³⁺ in BA1F, BA1, and BNF, increases the materials' affinity for tetracycline by coordinating with its functional groups, suggesting additional active sites for adsorption [

21,

22]. The K 2

p spectra indicates the presence of potassium, particularly in BN [

23].

3.7. CO2 Isotherm

The CO₂ adsorption isotherms in

Figure 8 reveal the amount of CO₂ adsorbed by the samples BN, BA1, BNF, and BA1F as a function of pressure. BN shows the lowest adsorption capacity at approximately 0.18 mmol.g

-1, with a gradual increase in adsorption as pressure rises [

24]. In contrast, BA1 adsorbs more CO₂, reaching about 0.26 mmol.g

-1, with a similar progressive increase in adsorption as pressure grows [

25]. BNF and BA1F exhibit the highest CO₂ adsorption capacities, reaching 0.32 mmol.g

-1 at higher pressures. Their isotherms are nearly identical, suggesting consistent high adsorption efficiency [

26]. All materials follow favorable adsorption behavior, with a positive correlation between CO₂ adsorption and pressure [

27]. The observed variations in adsorption capacities indicate differences in surface properties, such as surface area, pore size, and CO₂ affinity, which were evaluated using BET analysis, highlighting the impact of acid treatment on adsorption efficiency.

3.8. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA/DTG)

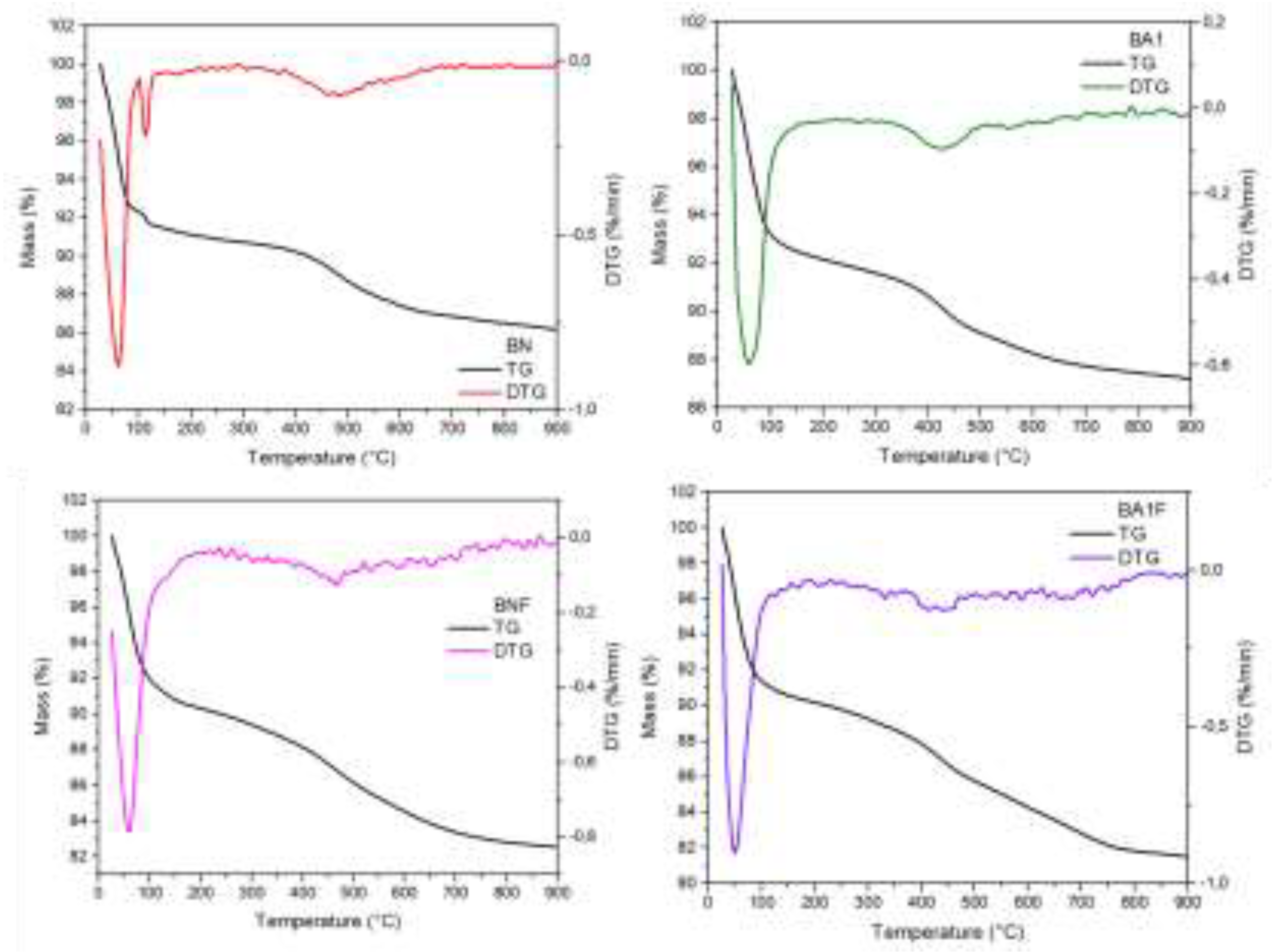

The thermogravimetric curves of the BN, BNF, BA1 and BA1F samples (

Figure 9) reveal two mass loss events, the first around 100 °C and the second around 740 °C. The thermogravimetric mass loss during this phase was 8.52%. The significant mass loss and high rate suggest that the bentonite had a high content of absorbed water and water between its layers, which was rapidly released [

23]. The two hydroxyl groups present in the crystalline structure were removed as water molecules, resulting in an endothermic peak and a mass loss at 447.5°C. At this stage, the thermogravimetric loss was 0.53%. The temperature at which bentonite undergoes dehydroxylation serves as an indicator of its heat resistance, reflecting its thermal stability. Despite the removal of its structural water and the loss of some of its original characteristics, the montmorillonite crystal still preserves its structure, with only distortions and twists in the layered structure, without evident signs of amorphization [

28].

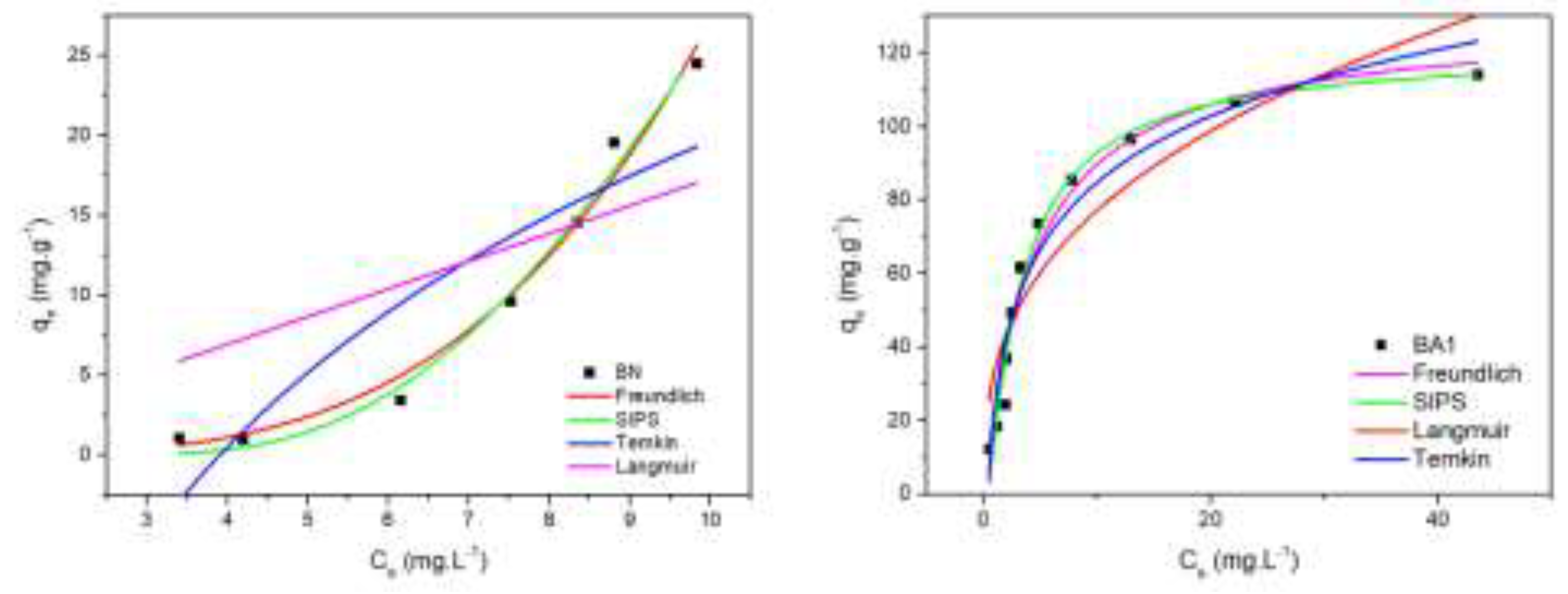

3.9. Adsorption Isotherms

To describe the relationship between the adsorbent and adsorbate when the adsorption process reaches equilibrium at different initial concentrations, the Langmuir, Freundlich, SIPS, and Temkin isotherm models were applied, as shown in

Figure 10. The model parameters provide insights into the adsorption mechanism, specific surface properties, and the affinity between the adsorbate and adsorbent. Equilibrium isotherm calculations for BA1 showed the best fit for the Freundlich model (R² > 0.9923), indicating a favorable adsorption process in heterogeneous systems or multilayer adsorption. Additionally, values of 1 < n < 10 confirm the favorable adsorption of the pharmaceutical under study [

29].

The Temkin model also showed a good fit (R² > 0.9163), suggesting a linear decrease in adsorption heat as the adsorbent surface becomes covered, indicating a maximum adsorption energy distribution [

22,

23]. The Langmuir model (R² > 0.5722) suggested a chemisorption mechanism, with adsorption forming a monolayer on the adsorbent surface with a finite number of sites [

30]. The experimental data were fitted to the Sips equilibrium isotherm model, which showed an excellent fit for both samples.

For BA1, the R² value was 0.9767, indicating a good description of adsorption with moderate surface heterogeneity. The BN sample showed a higher R² of 0.9958, suggesting a better fit and possibly greater surface uniformity or stronger adsorbate affinity. The difference in R² values highlights material-specific variations in adsorption behavior. Overall, the Sips model proved effective in predicting adsorption in heterogeneous systems and identifying adsorbent properties, aiding in the selection of more efficient materials [

31].

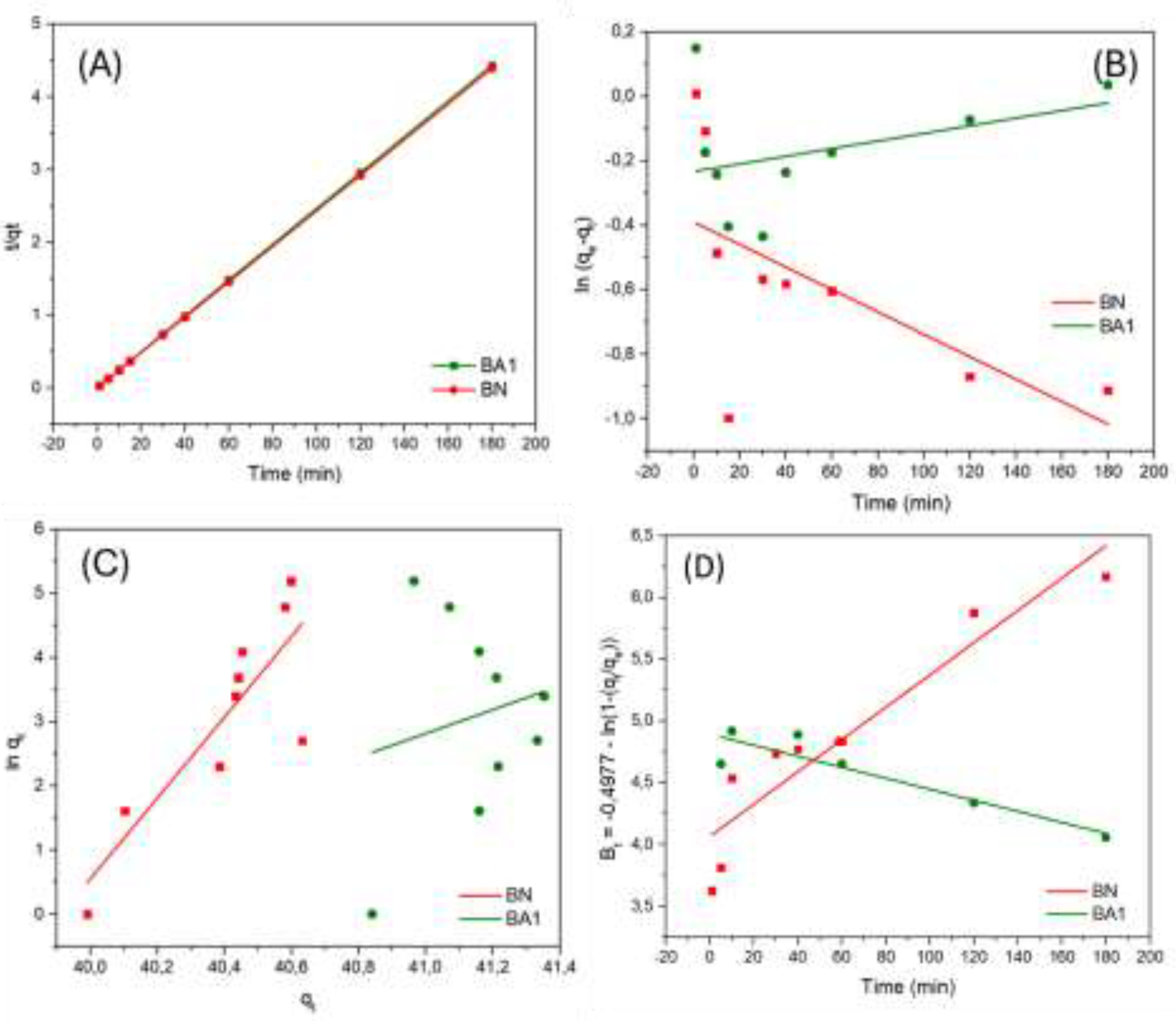

3.10. Adsorption Kinetics

When comparing the untreated and treated clay minerals, BA1 exhibited the highest experimental adsorption capacity (q

e = 41.35 mg.g⁻¹). Adsorption studies with BA1 (q

e = 40.98 mg.g⁻¹) showed an increase in the adsorbed amount of the drug compared to untreated BN (q

e = 40.60 mg.g⁻¹) (

Figure 11), highlighting the effectiveness of acid treatment in improving tetracycline adsorption.

Among the three models studied, the pseudo-second-order model provided the best fit to the data, with a determination coefficient near 1 (R² = 0.999). Additionally, this model showed a small difference between experimental (41.35 mg.g⁻¹) and calculated (40.60 mg.g⁻¹) values of q

e, suggesting that chemisorption is the rate-determining step in the tetracycline adsorption process, involving electron exchange or sharing between the adsorbent and adsorbate [

23]. The Elovich equation was also applied (

Figure 11C) but showed a poor fit for BA1 (R² > 0.6831), indicating that the regression model did not adequately explain data variability [

32].

To investigate the diffusional parameters of the process in more detail, the Boyd film diffusion theory was applied. The temporal evolution of the Bt parameter, shown in

Figure 11D, did not display linear behavior, suggesting that pore diffusion is not the rate-limiting step in the mechanism. This points to significant resistance to mass transfer in the external film [

33]. As shown in

Table 3, the liquid film diffusion rate constant (kb) was determined to be 0.03 min⁻¹, indicating reduced diffusion capacity due to the high initial concentration of the adsorbate [

34].

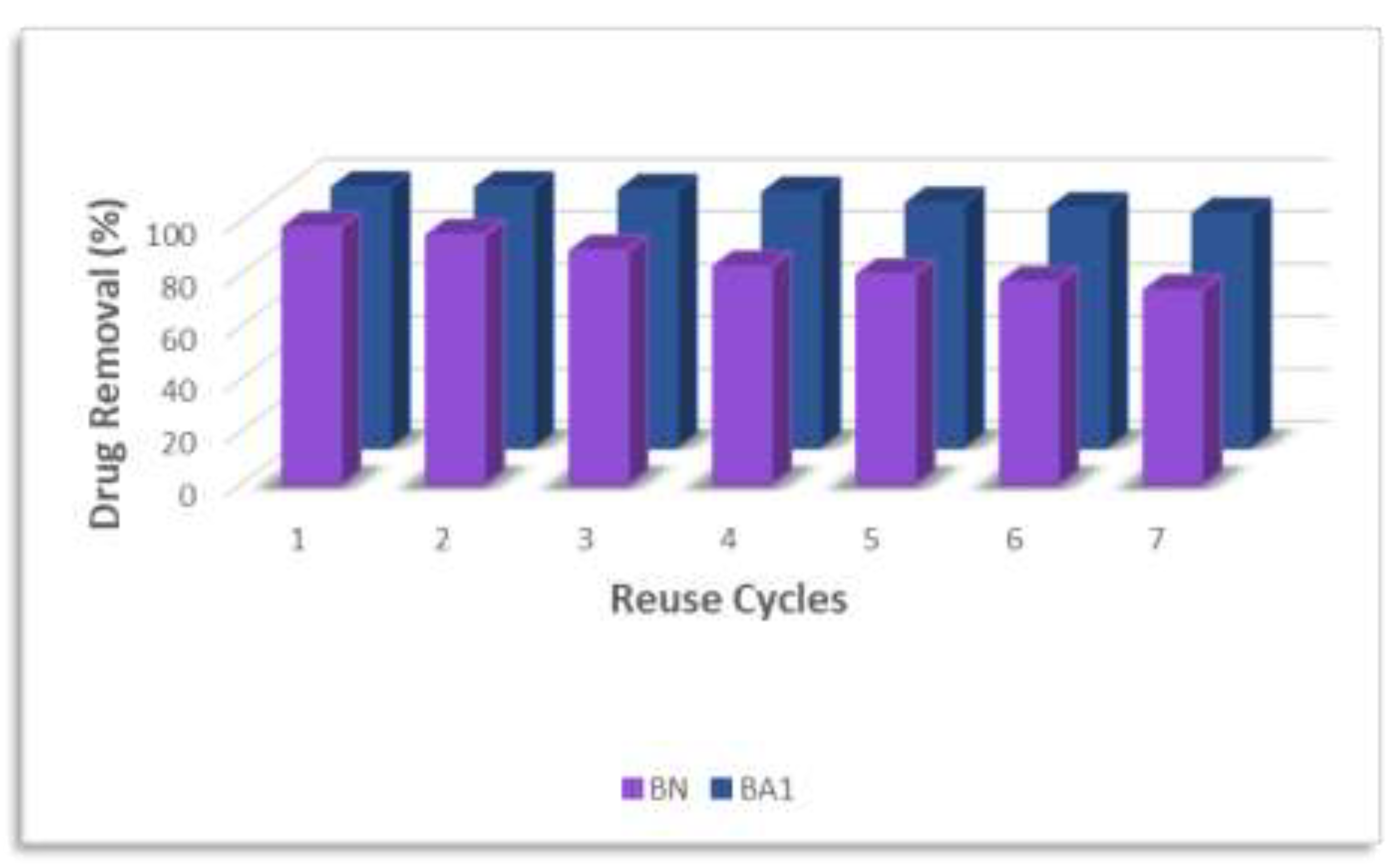

3.11. Reuse of the Adsorbent

The adsorbents BN and BA1 exhibited exceptional performance in reuse for the removal of the tested dyes (

Figure 12). Although a gradual decline, between 10–14% for the utilized adsorbents, in removal efficiency was observed over successive reuse cycles—expected due to material wear—the methodology proved to be effective and reliable, preserving the adsorbents' functionality at a satisfactory level. Notably, BA1 demonstrated remarkable recovery capability after TC removal, with only a 10% decrease even after consecutive cycles. Even after the seventh reuse cycle, this adsorbent maintained high removal efficiency, highlighting its stability and potential for repeated applications in wastewater treatment processes [

23].

4. Conclusions

This study underscores the potential of bentonite-based materials as effective and sustainable adsorbents for removing contaminants from pharmaceutical effluents, aligning with the United Nations' 2030 Agenda, specifically SDG 12 on Responsible Consumption and Production. Among the adsorbents tested, BA1 exhibited superior performance compared to BA2.5, reducing reagent consumption and waste generation, while maintaining high adsorption efficiency. Advanced characterization techniques such as XPS, XRF, EDS, SEM, and TEM revealed a silicon- and aluminum-rich composition, with acid treatment significantly enhancing surface properties, such as increased surface area and functional group availability.

The reuse analysis demonstrated that BA1 maintained high removal efficiency even after multiple cycles, indicating its robustness and suitability for continuous applications in wastewater treatment. The kinetic studies confirmed that the optimal adsorption conditions for BA1 are achieved within 30 minutes using 0.30 g of adsorbent, following a pseudo-second order kinetic model and Freundlich isotherm. This suggests a mixed adsorption mechanism involving both chemisorption and physisorption.

The modification of bentonite through acid treatment with HCl further enhanced adsorption capacity by introducing oxygenated functional groups and altering oxidation states, particularly for materials rich in iron. These modifications not only improved the adsorption of pharmaceutical contaminants like tetracycline but also demonstrated the versatility of bentonite in adapting to diverse industrial and environmental challenges.

Overall, this work highlights bentonite as a readily available, eco-friendly material with immense potential for sustainable applications in the pharmaceutical industry, particularly in the development of reusable, high-efficiency adsorbents. The results pave the way for further innovations in material design, contributing to a circular economy and enhanced environmental stewardship.

Author Contributions

Aisha V. S. Pereira: Conceptualization, Methodology, Experimental operation, Data analysis, Visualization, Investigation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Adriano Freitas: Investigation, Data analysis. Anne B. F. Câmara: Conceptualization, Methodology, Visualization, Investigation, Writing - review & editing. Mariana R. L. Silva: Conceptualization, Methodology, Visualization, Investigation, Writing - review & editing. Heloise O. M. A. Moura: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data analysis, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Enrique Rodríguez-Castellón: Writing - review & editing, Discussion, Data analysis, Funding, Resources. Daniel Plata-Ballesteros: Writing - review & editing, Discussion, Data analysis. Luciene S. de Carvalho: Conceptualization, Resources, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing - review & editing.

Funding

This study was financed in part by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico—Brazil (CNPq) — Finance Code 151750/2023-8 and the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brazil (CAPES)—Finance Code 001. Enrique Rodríguez-Castellón thanks to the project PID2021-126235OB-C32 funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033/ and FEDER funds.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to intellectual property considerations.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Molecular Sieve Laboratory (LABPEMOL) and the Analytical Centre (IQ/UFRN).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Farto, C.D.; Athayde Jr., G. B.; et al. Contaminantes de preocupação emergente no Brasil na década 2010- 2019 – Parte I: ocorrência em diversos ambientes aquáticos. Revista de Gestão de Água da América Latina, v. 18, p. 1-19, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Leite, H. Debate sobre venda de remédios em supermercados e pela internet coloca R$ 20 bilhões em disputa. 2022. Disponível em: https://cev.fgv.br/noticia/debate-sobre-venda-de-remedios-em-supermercados-e-pela-internet-coloca-r-20-bilhoes-em. Acesso em: 12 ago. 2024.

- Regitano, J.B. Comportamento e impacto ambiental de antibióticos usados na produção animal brasileira. Revista Brasileira de Ciência do Solo, v. 34, p. 601-616, 2010. Disponível em. Materials Science for Energy Technologies, v. 7, p. 282–286, 1 jan. 2024.

- Fernandez, F.A. Adsorción de Antibióticos sobre bentonitas naturales y modificadas. Neuquén, Diciembre de 2015.

- Maia, P.P.; Rath, S.; Reyes, F.G.R. Antimicrobianos em alimentos de origem vegetal: uma revisão. Segurança Alimentar e Nutricional, v. 16, n. 1, p. 49-64, 2009. Disponível em: https://periodicos.sbu.unicamp.br/ojs/index.php/san/article/view/1811.

- Shi Y, Wang X, et al. Nano-clay montmorillonite removes tetracycline in water: Factors and adsorption mechanism in aquatic environments. IScience, 27(2), 108952–108952. (2024).

- Sadjadi, S.; Malmir, M.; Heravi, M.M. A novel magnetic heterogeneous catalyst based on decoration of halloysite with ionic liquid-containing dendrimer. Applied Clay Science, v. 168, p. 184-195, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Salgado-Campos, V. M. J.; Bertolino, L. C.; Silva, F. J.; Mendes, J. C.; Neumann, R. Mineralogy and chemistry of a new halloysite deposit from the Rio de Janeiro pegmatite province, south-eastern Brazil. Clay Minerals, v. 56, 1-15, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Parolo, M.E. , Savini M., Valles J., Baschini M., Avena M. Tetracycline adsorption on montmorillonite: effects of pH and ionic strength. Applied Clay Science 40 (2008) 179-186.

- Usman, F.; Muhammad, A. PREPARATION AND CHARACTERIZATION OF BENTONITE CLAY CATALYSTS FOR TRANSESTERIFICATION OF WASTE COOKING OIL INTO BIODIESEL. FUDMA Journal of Sciences, v. 8, n. 2, p. 204–211, 30 abr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Nicolás, M. F.; et al. Low-temperature sintering of ceramic bricks from clay, waste glass and sand. Boletín de la Sociedad Española de Cerámica y Vidrio, 1 jun. 2024.

- POKHAREL, B.; SIDDIQUA, S. Effect of calcium bentonite clay and fly ash on the stabilization of organic soil from Alberta, Canada. Engineering Geology, v. 293, p. 106291, nov. 2021.

- Bharali, P. Acid Treatment on Bentonite Clay for the Removal of Fast Green FCF Dye from Aqueous Solution. Environmental Quality Management, v. 34, n. 1, 25 jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Rianna, M.; et al. Experimental investigation on ceramic materials of wood flour and bentonite. Journal of Physics Conference Series, v. 2733, n. 1, p. 012016–012016, 1 mar. 2024.

- Kgabi, D. P.; Ambushe, A. A. Characterization of South African Bentonite and Kaolin Clays. Sustainability, v. 15, n. 17, p. 12679–12679, 22 ago. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y. , Wang, S., Meng, X. et al. Acid Treatment on Bentonite Catalysts for Alkylation of Diphenylamine. Catal Lett 154, 4928–4940 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Barrera D, Villarroel J, Torres D, Sapag K. SÍNTESIS Y CARACTERIZACIÓN DE EXTRUIDOS CERÁMICOS DE BENTONITA PARA LA REMOCIÓN DE Pb (II) EN SOLUCIÓN ACUOSA. IBEROMET XIX CONAMET/SAM. 2 al 5 de Noviembre de 2010, Viña del Mar, CHILE.

- Huang, C. , Ma, Q., Zhou, M. et al. Adsorption Effect of Oxalic Acid-Chitosan-Bentonite Composite on Cr6+ in Aqueous Solution. Water Air Soil Pollut 234, 540 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Liu, WT. , Tsai, SC., Tsai, TL. et al. Characteristic study for the uranium and cesium sorption on bentonite by using XPS and XANES. J Radioanal Nucl Chem 314, 2237–2241 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Moura, Heloise Oliveira Medeiros de Araujo. Innovative methodologies in the concept of biorefinery for the analysis and derivatization of lignocellulose. Tese (Doutorado) - Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte. Centro de Ciências Exatas e da Terra - CCET, Instituto de Química. Programa de Pós-Graduação em Química (PPGQ). 169 f. Natal: UFRN, 2023.

- Sudan, S. , Kaushal, J., Khajuria, A. et al. Bentonite clay-modified coconut biochar for effective removal of fluoride: kinetic, isotherm studies. Adsorption 30, 389–401 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Sales, R.V. Avaliação da dessulfurização de diesel utilizando adsorventes mesoporosos modificados pós-situ com íons metálicos. 2015. 117f. Tese (Doutorado em Química) – Programa de Pós-Graduação em Química, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal, RN, Brasil, 2015.

- Silva, M.R.L. Estudo da adsorção dos corantes sintéticos azul de metileno e vermelho do congo e do antibiótico tetraciclina utilizando o argilomineral haloisita. 2024. 129f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Química) – Programa de Pós-Graduação em Química, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal, RN, Brasil, 2024.

- Hamad, N. H.; et al. Optimized Bentonite Clay Adsorbents for Methylene Blue Removal. Processes, v. 12, n. 4, p. 738–738, 5 abr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; et al. Multicomponent gases (CH4/CO2/C6H6) diffusion and adsorption in unsaturated bentonite: A molecular insight. Computers and Geotechnics, v. 169, p. 106178–106178, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Cecília, J.A. , Vilarrasa-García E., Cavalcante Jr C.L., Azevedo D.C.S., Franco F., Rodríguez-Castellón E. Evaluation of two fibrous clay minerals (sepiolite and palygorskite) for CO2 Capture. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering v. 6, 4573-4587, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Sarode, U. K.; Vaidya, P. D. Catalytic desorption of CO2-loaded solutions of diethylethanolamine using bentonite catalyst. The Canadian Journal of Chemical Engineering, v. 102, n. 3, p. 1262–1271, 28 set. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Hai, L. , Wang, J. Experimental study on the heat treatment reaction process of bentonite. Sci Rep 14, 16649 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Freundlich, H. Of the adsorption of gases. section ii. kinetics and energetics of gas adsorption. introductory paper to section ii. Transactions of the Faraday Society, v. 28, p. 195–201, 1932. [CrossRef]

- Langmuir, I. The constitution and fundamental properties of solids and liquids. Journal of the American Chemical Society, v. 38, p. 2221–2295, 1916. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10. 1021. [Google Scholar]

- Aguareles, M.; Barrabés, E.; Myers, T.; Valverde, A. Mathematical analysis of a Sips-based model for column adsorption. Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena, v. 448, p. 133690, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Elodoma, M. A. Studies on the isotherm, kinetic, and thermos-sorption aspects of the Cr (VI) uptake onto commercial bentonite. Jouf University Science and Engineering Journal (JUSEJ) 2023; 10(2): 8- 9. Disponível em: https://www.ju.edu.sa/fileadmin/jouf_University_Science_and_Engineering_Journal/Journal/AUSEJ_10-22_01.pdf#page=103.

- Han, G.; et al. Preparation of lanthanum-modified bentonite and its combination with oxidant and coagulant for phosphorus and algae removal. Journal of water process engineering, v. 59, p. 104925–104925, 1 mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Câmara, A.B.F.; Sales, R.V.; Bertolino, L.C.; Furlanetto, R.P.P.; Rodríguez-Castellón, E.; Carvalho, L.S. Novel application for palygorskite clay mineral: a kinetic and thermodynamic assessment of diesel fuel desulfurization. Adsorption, v. 26, p. 267-282, 2020. Disponível em. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Influence of pH on tetracycline adsorption with BN.

Figure 1.

Influence of pH on tetracycline adsorption with BN.

Figure 2.

XRD of samples BN, BNF, BA1 and BA1.

Figure 2.

XRD of samples BN, BNF, BA1 and BA1.

Figure 3.

SEM images of BN, BA1, BNF, and BA1F samples.

Figure 3.

SEM images of BN, BA1, BNF, and BA1F samples.

Figure 4.

HRTEM of samples BN and BA1.

Figure 4.

HRTEM of samples BN and BA1.

Figure 5.

EDX Mapping of samples BN (A) and BA1 (B).

Figure 5.

EDX Mapping of samples BN (A) and BA1 (B).

Figure 6.

N2 adsorption isotherms of BN, BNF, BA1, and BA1F samples.

Figure 6.

N2 adsorption isotherms of BN, BNF, BA1, and BA1F samples.

Figure 7.

Deconvolution of the XPS spectrum of the elements present on the surface of the samples.

Figure 7.

Deconvolution of the XPS spectrum of the elements present on the surface of the samples.

Figure 8.

CO2 adsorption isotherms of BN, BNF, BA1, and BA1F samples.

Figure 8.

CO2 adsorption isotherms of BN, BNF, BA1, and BA1F samples.

Figure 9.

Thermogravimetric Analysis (TG/DTG) of BN, BNF, BA1, and BA1F samples.

Figure 9.

Thermogravimetric Analysis (TG/DTG) of BN, BNF, BA1, and BA1F samples.

Figure 10.

Adsorption Isotherms of BN and BA1 Samples.

Figure 10.

Adsorption Isotherms of BN and BA1 Samples.

Figure 11.

Kinetic Adsorption Graphs of BN and BA1 Samples for the Pseudo-Second Order Model (A), Pseudo-First Order Model (B), Elovich Model (C), and Boyd Film Diffusion Model (D).

Figure 11.

Kinetic Adsorption Graphs of BN and BA1 Samples for the Pseudo-Second Order Model (A), Pseudo-First Order Model (B), Elovich Model (C), and Boyd Film Diffusion Model (D).

Figure 12.

Reuse of BN and BA1 adsorbents after drug adsorption.

Figure 12.

Reuse of BN and BA1 adsorbents after drug adsorption.

Table 1.

XRF of samples BN and BA1.

Table 1.

XRF of samples BN and BA1.

| Elements |

BN – composition (%) |

BA1 – composition (%) |

| Si |

52.35 |

62.51 |

| Fe |

18.57 |

13.13 |

| Al |

15.18 |

15.83 |

| K |

3.42 |

3.28 |

| Ca |

2.73 |

1.23 |

| Na |

0.87 |

0.00 |

| Mg |

2.06 |

1.93 |

| Others |

4.65 |

2.06 |

Table 2.

N2 adsorption data of the samples.

Table 2.

N2 adsorption data of the samples.

| Samples |

SBET (m2.g-1) |

Vpa (cm3.g-1) |

Pore Diameter (Å) |

| BN |

63 |

0.06 |

37.43 |

| BA1 |

165 |

0.15 |

35.29 |

| BNF |

17.8 |

0.02 |

43.78 |

| BA1F |

121 |

0.09 |

32.67 |

Table 3.

Parameters for the fitting to pseudo-first order, pseudo-second order, Elovich and Boyd’s Film Diffusion models.

Table 3.

Parameters for the fitting to pseudo-first order, pseudo-second order, Elovich and Boyd’s Film Diffusion models.

| Kinects Parameters |

BN |

BA1 |

| qe,exp (mg.g-1) |

3.84 |

4.08 |

| Pseudo-first order |

|

|

| k1 (min-1) |

-0.0008 |

-0.0026 |

| qe,cal (mg.g-1) |

0.271 |

0.483 |

| R2

|

0.9799 |

0.848 |

| Pseudo-second order |

|

|

| k2 (g.mg-1.min-1) |

0.0071 |

0.1232 |

| qe,cal (mg/g) |

3.87 |

4.04 |

| R2

|

0.9998 |

0.9998 |

| Elovich |

|

|

| α (mg.g-1 min-1) |

7.30x10-5

|

1.30x10-2

|

| β (g.mg-1) |

0.309 |

0.906 |

| R2

|

0.9681 |

0.9679 |

| Boyd’s Film Diffusion |

|

|

| Kb (min-1) |

0.01 |

-0.004 |

| R2

|

0.86 |

0.80 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).