Section 1. Introduction

Deep-time phylogenetics focuses on unraveling evolutionary relationships that extend across tens of millions of years-intervals long enough for major phenotypic transformations, large-scale environmental shifts, and complicated speciation patterns to occur. Traditional phylogenetic approaches, such as maximum parsimony or maximum likelihood (Felsenstein, 1981), have proven valuable for reconstructing trees within relatively recent timeframes. However, they often face profound challenges in deep-time contexts. Long branches, uncertain fossil calibrations, and incomplete morphological data complicate attempts to infer when key evolutionary lineages diverged or how specific morphological traits evolved over geologic intervals.

In the last few decades, Bayesian approaches have expanded phylogenetic inference by providing a statistical framework that can explicitly handle uncertainties in fossil ages, morphological measurements, and molecular data (Rannala & Yang, 1996; Yang & Rannala, 1997). Rather than relying on point estimates, Bayesian methods produce posterior distributions that reflect the plausible range of divergence times, topologies, and model parameters. While powerful, these methods still often adopt discrete or piecewise-constant views of trait evolution, especially when incorporating morphological features. For instance, morphological characters might be modeled as discrete states (presence/absence, multi-state), and time is partitioned at branching events or in relaxed-clock segments (Drummond et al., 2006). Such discretization can lead to inaccuracies when morphological changes are gradual, continuous processes

Section 1.1. Use of Partial Differencial Equations

A natural way to tackle continuous trait variation over extended timespans is to turn to partial differential equations (PDEs). PDEs are standard in physics, chemistry, and engineering for modeling processes that vary continuously in space and time-heat conduction, fluid flow, chemical diffusion, and so forth. In evolutionary biology, PDEs have occasionally been explored, for example, in population genetics (Kimura, 1964) to describe allele frequency diffusion in an idealized population. More broadly, PDEs can also depict how morphological traits diffuse, react, or drift under selection, mutation, and other evolutionary forces. Yet, the direct integration of PDEs into phylogenetic inference-particularly over millions of years-remains a developing frontier.

One of the major conceptual insights prompting the use of PDEs in phylogenetics is the possibility of modeling trait evolution as a continuous-time and continuous-state phenomenon. Rather than slicing time at branching nodes or enumerating discrete morphological character states, PDE-based frameworks can define a morphological coordinate

(e.g., 0 to 1 for a normalized trait index) and then specify how the probability density or expected trait value

evolves with time

. This leads to reaction-diffusion PDE forms, which can incorporate logistic-like selection terms. For example, a simple PDE might look like:

where

is a diffusion term capturing neutral drift or morphological "spread," and

is a logistic reaction term that might reflect stabilizing or directional selection. Such PDEs also allow boundary conditions that can fix or reflect constraints on trait extremes (e.g., morphological impossibilities at

or

).

Still, adopting PDEs raises computational and conceptual hurdles:

(1) PDEs typically require numerical discretization (finite differences, finite elements) or approximate surrogates, which can be expensive when repeated within a Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) loop.

(2) PDE parameters (e.g., ) and boundary conditions become new "unknowns" in a Bayesian scheme, necessitating robust priors.

(3) Fossil data typically appear as point constraints in time and trait space -for example, a partial skeleton at Myr with trait measurement 0.8 on a normalized scaleso PDE-based frameworks must incorporate interior boundary-like constraints or "soft" calibration in the likelihood.

To address computational challenges, recent developments in physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) have opened a promising avenue (Raissi, Perdikaris, & Karniadakis, 2019). PINNs allow us to embed PDE residuals into a neural network training objective, effectively making the network learn to satisfy the PDE across the domain. This approach can short-circuit the need for a standard PDE solve at every iteration by providing a surrogate model. When fused with Bayesian inference, one can imagine a two-level process: (1) the PDE is approximated by a PINN with trainable weights , and (2) fossil observations, morphological data points, and prior distributions on PDE parameters feed into an overall posterior. Although still in its infancy in phylogenetics, this blend of PDE-based modeling and neural network approximation is extremely powerful for large-scale or deep-time problems.

Section 1.2. The Use of Partial Stochastic Equations

Yet, purely deterministic PDEs may fail to capture the random fluctuations inherent in evolution, particularly for lineages subject to population bottlenecks, shifting climates, or other unpredictable events. Hence, another layer of complexity emerges with stochastic partial differential equations (SPDEs). In an SPDE, one adds a noise term to the PDE, modeling the uncertain or random aspects of morphological change. The presence of recognizes that evolution does not always proceed smoothly or deterministically, especially when fossil data is sparse and morphological leaps can appear abruptly. SPDE approaches are more akin to certain population genetic treatments (e.g., Kimura diffusion) but extended into morphological trait spaces. Because the noise can cause solution blow-up or numerical instabilities, using SPDEs requires careful numerical integration schemes (like Euler-Maruyama) or advanced "stochastic PINNs" that incorporate random draws during training.

Moreover, fossil calibration in deep-time PDE or SPDE models is both an opportunity and a challenge. The "fossil calibration" concept in typical Bayesian phylogenetics means imposing time constraints on certain nodes (e.g., this group must have diverged by 20 Myr ). But in a PDE-based morphological perspective, we effectively say "At time , the morphological trait at was measured to be also uncertain ( 19.5 to 20.5 Myr ), that uncertainty must be integrated into the PDE model. The PDE might be forced to pass near with . In a Bayesian framework, we treat as random variables (with priors) or observed data with known error distributions. In either case, building these constraints into PDE or SPDE solutions is not trivial.One also cannot ignore that deep-time phylogenetics usually rests on both molecular and morphological data. Genomic alignments provide valuable information about substitution rates and branching patterns, but morphological data (including fossils) is crucial for calibrating nodes.

The "holy grail" would be to unify PDE-based morphological evolution with coalescent-based or relaxed-clock molecular models under a single Bayesian roof, though the computational overhead can be daunting.

Given these motivations and complexities, our integrative approach includes:

A deterministic PDE that sets up a reaction-diffusion framework for trait evolution, specifying how morphological traits drift or diffuse over time.

A Bayesian layer where PDE parameters (e.g., ) and fossil times are uncertain and updated with data.

PINN-based surrogates that drastically reduce the cost of solving PDEs at each iteration, letting us handle larger morphological datasets and more complex domain constraints.

Mini-batch training within the PINN to enhance scalability. By randomly sampling small sets of time-space points for the PDE residual and fossil calibration points for data matching, we can update neural network parameters incrementally (similarly to standard mini-batch approaches in machine learning).

An SPDE extension to incorporate randomness in trait evolution. By adding a term to the PDE, we account for environmental fluctuations or demographic noise over geologic timescales. While this complicates the numerical solution, it can yield more biologically realistic trajectories, especially if morphological transitions are not strictly deterministic.

Section 1.3. Workflow Proposed

In practical terms, our workflow might look like this:

Data Preparation: Gather fossil data (time error, morphological trait measures error) and extant species morphological data. Possibly incorporate molecular data for cross-validation or combined inference.

Specify PDE or SPDE: Choose whether we employ a purely deterministic PDE or a stochastic PDE. For a deterministic PDE, define reaction-diffusion terms and boundary conditions. For an SPDE, incorporate a noise amplitude

Construct the PINN: A feedforward neural network or more sophisticated architecture. The PDE (or SPDE) residual is embedded into the loss function.

Mini-Batch Training: At each iteration, sample points from the domain to compute PDE residuals and sample fossil constraints to compute fossil mismatch. The sum of these residuals forms the batch loss, which is backpropagated through the network. The network learns to approximate the PDE solution that best matches known constraints.

Bayesian Parameter Updates: If we are performing full MCMC, we might sample PDE parameter sets , adjusting them and retraining (or partially retraining) the PINN each time. Alternatively, we might train the PINN once for a wide range of values in a "meta-learning" approach, but this is more advanced.

Result: A final morphological trajectory with credible intervals over , plus an inferred phylogenetic tree. The latter can come from standard tree reconstruction software that is fed with node calibrations gleaned from the PDE-based morphological constraints.

Throughout this process, the question arises whether the added complexity is justified. Deterministic PDEs, if well-tuned, may suffice when morphological changes are fairly gradual and the data are robust. Stochastic PDEs might be essential if data are scarce or morphological transitions appear erratic in the fossil record-implying large leaps that might be better explained with a random forcing term. The synergy with mini-batch PINNs is a key enabling technology, bridging the PDE or SPDE solution and the large datasets typical of modern morphological and genomic investigations.

Section 1.4. Importance for Phylogenetics

By modeling morphological change in a continuous manner, the PDE or SPDE approach can yield deeper insights into how lineages transition from ancestral states to derived states over geologic times. For instance, in whale evolution, one might track how limb length gradually shortens while flukes become more pronounced from semi-terrestrial ancestors to fully aquatic modern whales. PDE-based approaches can reflect a time continuum that’s not locked to branching nodes alone, possibly capturing a more realistic trajectory. Meanwhile, the ability to incorporate fossil calibrations at partial time points (and within partial morphological states) addresses a well-known limitation in standard discrete methods, which often treat morphological changes as strictly discrete or rely on morphological clocks that can be difficult to parametrize. The challenges, therefore, are:

(1) PDE or SPDE parameter identifiability remains a concern. With limited fossil data, the range of feasible ( ) can be broad, resulting in wide posterior distributions.

(2) The morphological domain itself ( 0 to 1 ) might oversimplify multi-dimensional traits, suggesting a need for higher-dimensional PDEs or manifold-based PDEs.

(3) Numerical stability in SPDE solutions requires careful time-step sizing or advanced "stochastic PINN" approaches.

(4) Integrating molecular data thoroughly might require parallel PDE solutions for morphological states and standard substitution models for genomic sequences, which is computationally heavy.

Nevertheless, with the expansion of high-performance computing and GPU/TPU acceleration, these integrated PDE-based frameworks are increasingly feasible.

Ultimately, our updated approach underscores a shift toward continuous-time modeling of morphological evolution, harnessing PDEs for deterministic aspects and SPDEs for stochastic aspects. By embedding them within a Bayesian or data-driven neural network framework, we gain a powerful toolkit for bridging morphological, molecular, and paleontological data in ways that older discrete or purely maximum-likelihood methods struggled to achieve. As more lineages are studied and more transitional fossils discovered, we anticipate PDE-based or SPDE-based phylogenetic inference to become a compelling alternative, bringing new clarity to the deep-time transitions that shape Earth’s biodiversity.

Section 2. Methodology

Section 2.1. Deterministic PDE Modeling of Morphological Evolution

Section 2.1.1. Baseline PDE Setup

The initial and simplest approach focuses on a deterministic partial differential equation (PDE) to model the continuous evolution of a morphological trait

over geological time

and morphological space

. For a 1D morphological trait (e.g., limb length, cranial index, or a dimensionless morphological score normalized to

), one can write:

where:

spans tens of millions of years ( present; deep past, e.g., 25 Myr,

denotes the normalized trait range,

is a diffusion coefficient, modeling neutral drift or spread of the trait,

is a reaction coefficient, capturing selective pressures via a logistic form

Boundary conditions (e.g., Neumann for no-flux at ) and initial conditions (e.g., a uniform or measured trait distribution at ) complete the PDE specification. This equation can be solved numerically (finite differences, finite elements) or treated analytically under simplifying assumptions. In its earliest form, the PDE approach does not yet incorporate fossil data or explicit Bayesian machinery, serving primarily as a proof of concept that morphological evolution can be modeled continuously over geological times.

Section 2.2. Bayesian Extension of the PDE Model

Section 2.2.1. Rationale for a Bayesian Framework

Although the deterministic PDE model provides a mechanistic view of how traits diffuse and react over time, real phylogenetic inference must handle uncertainties-in fossil dating, morphological measurements, molecular clocks, etc. By adopting a Bayesian perspective, we can treat PDE parameters , fossil times, and other phylogenetic variables (e.g., substitution rates) as random variables with prior distributions. Observed data (fossil measurements, extant species morphology, sequence alignments) then define a likelihood that updates these priors into a posterior distribution.

Section 2.2.2. Fossil Calibration Within a PDE

Fossils dated at time with morphological trait can be incorporated into the PDE solution as either:

Boundary/Interior Condition:

Likelihood Constraint: For instance, a penalty term in the log-likelihood if the PDE solution at ( ) deviates from the observed

Either way, we treat and as data that constrain the PDE solution. When itself is uncertain (e.g., ), we place a prior (normal or truncated normal) on . The PDE-based model then acts as a structural prior on the continuous transformation of traits over time.

Section 2.3. Bayesian Inference Mechanisms

A typical Bayesian MCMC approach would:

Sample PDE parameters (e.g., ), fossil times , and possibly tree topologies.

Numerically solve or approximate the PDE with the proposed

Compute the likelihood of observed morphological and fossil data given the PDE solution.

Accept or reject the proposal based on posterior probabilities.

Over many iterations, this yields a posterior distribution that captures parameter uncertainties, leading to credible intervals on morphological diffusion rates, time calibrations, and evolutionary trees.

Section 2.4. Surrogate Modeling with PINNs

Section 2.4.1. Motivations for Surrogates

Repeatedly solving PDEs in a Bayesian loop (e.g., MCMC) can be computationally prohibitive. Hence, we introduce physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) to act as surrogates for the PDE solution . Instead of re-solving the PDE from scratch for each parameter set , a trained neural network approximates the PDE solution efficiently.

Section 2.4.2. PINN Training Objectives

Let

be a feedforward neural network with parameters

. The PINN loss typically has two components:

enforcing that

satisfies the PDE over the domain.

2. Data/Fossil Constraints:

ensuring the network output matches known fossil or extant morphological data.

The total PINN loss (5) is minimized with standard optimizers (e.g., ADAM).

Section 2.5. Mini-Batch Training for Large-Scale Efficiency

Section 2.5.1. Rationale for Mini-Batching

When data become massive-e.g., thousands of fossil constraints or multi-dimensional morphological traits-training the PINN on the entire dataset each iteration can be slow or prone to overfitting. Mini-batch training tackles this by randomly sampling batches of points from:

By updating network parameters on these small batches, we gain speed and improved generalization. Over many epochs, the PINN sees the entire dataset in manageable chunks, stabilizing the solution.

Section 2.5.2. Loss Functions with Mini-Batch

At each epoch:

Sample a batch from the PDE domain; compute PDE residual errors.

Sample a batch of fossil data from the calibration set; compute mismatch.

Sum the losses to get a batch loss.

Update via gradient descent.

Tracking error curves (like PDE loss, fossil loss, total loss) helps diagnose convergence. Additionally, one can monitor a cumulative error metric over epochs to see if the model experiences large fluctuations early on before stabilizing.

Section 2.6. Stochastic PDE (SPDE) Extension

Section 2.6.1. Why SPDEs?

The deterministic PDE approach (

Section 1,

Section 2,

Section 3 and

Section 4) can miss intrinsic randomness (e.g., random genetic drift, environmental volatility). Introducing a stochastic forcing term

transforms the PDE into an SPDE:

where

is the noise magnitude and

a random process (often white noise or a correlated field). This approach can be more biologically realistic-especially when fossil records are sparse and large evolutionary jumps could be due to unpredictable events.

Section 2.7. Numerical Integration of SPDEs

For 1D or low-dimensional morphological spaces, one can discretize

and apply an Euler-Maruyama scheme:

where

is a random draw (e.g.,

) each time-step and space-point. We can also incorporate fossil constraints by either "clamping" or "nudging" the solution at

. In a Bayesian context,

would be another parameter to infer.

Section 2.7.1. PINNs for SPDEs

Alternatively, SPDEs can be tackled with PINNs that model both the deterministic PDE terms and the stochastic forcing. However, the training process becomes more complex, sometimes requiring specialized stochastic PINNs or physics-informed approaches that incorporate random fields in the loss function.

Section 2.8. Putting It All Together

Begin with a Deterministic PDE: Reaction-diffusion with logistic growth to capture baseline morphological evolution over tens of millions of years.

Embed in a Bayesian Framework: Treat PDE parameters, fossil times, and morphological data as uncertain. Use PDE solutions as priors or part of the likelihood, updating them with MCMC or other Bayesian samplers.

Accelerate via PINNs: Replace computationally intensive PDE solvers with neural network surrogates, minimizing PDE residual and fossil mismatch.

Use Mini-Batch to Handle Large Datasets: Shuffle PDE domain points and fossil calibrations into small batches, updating network weights in iterative steps. Track PDE loss, fossil loss, and total/cumulative error to confirm convergence.

Extend to SPDE if Randomness Is Key: Incorporate a noise term to reflect environmental or genetic drift fluctuations. Solve (or approximate) the SPDE with standard numerical methods (or approximate) the SPDE with standard numerical methods or advanced SPDE-PINNs.

This layered methodology provides the flexibility to scale from a

simple PDE approach to a

stochastic PDE with

robust Bayesian inference. It accommodates fossil calibrations, uncertain morphological measurements, and massive data volumes, ultimately supporting

deep-time phylogenetic reconstructions that integrate morphological, molecular, and paleontological evidence in a single unified framework. We present in the Results

Section 4 Graphs produced by Python Codes (please see attachment) for better clarification.

Section 3. Results and Graph Explanation

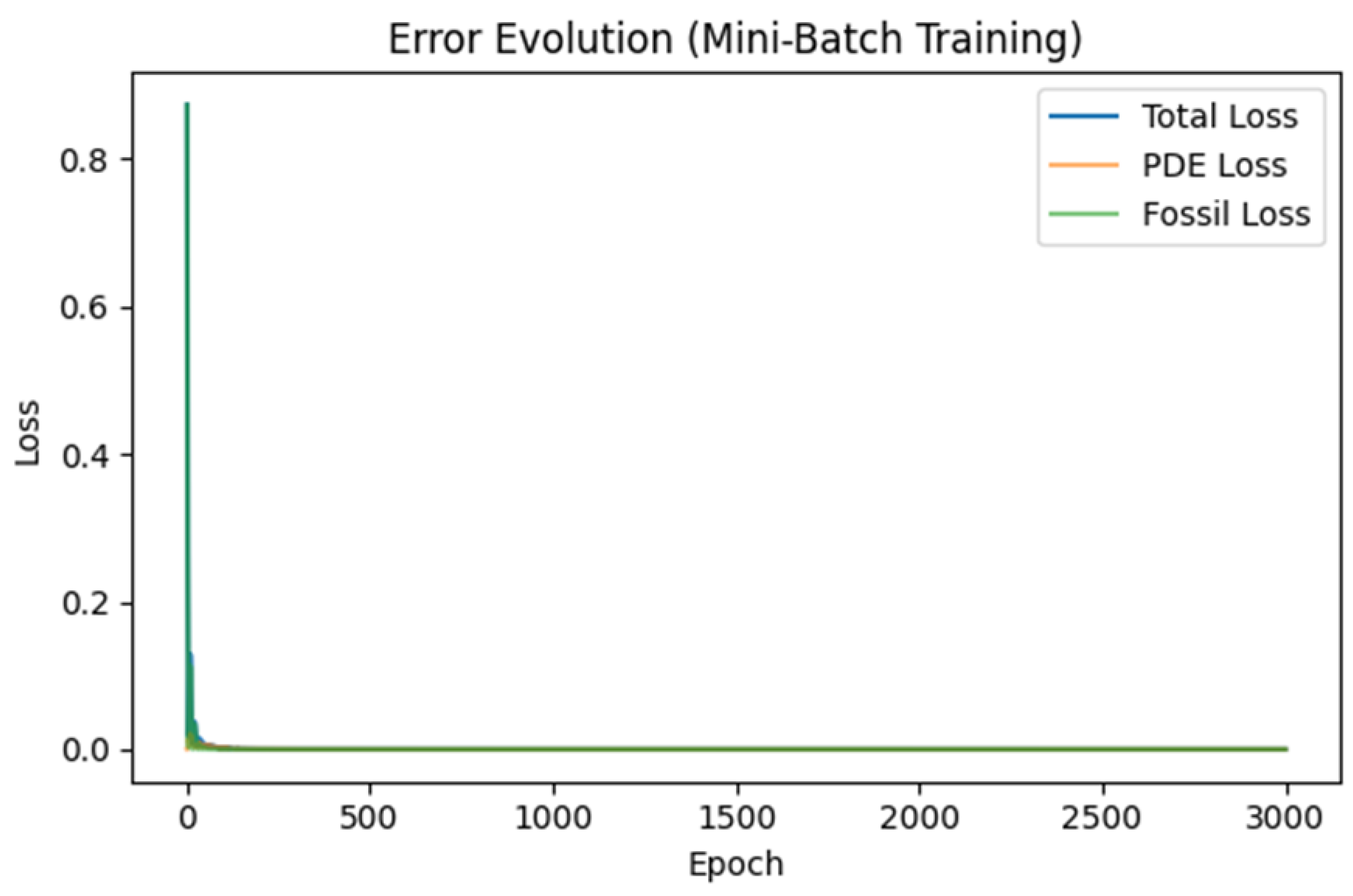

Graph 1.

Error Evolution (Mini-Batch Training). A line chart showing Total Loss, PDE Loss, and Fossil Loss as training epochs progress. Early in training, errors are high as the network tries to satisfy both PDE residuals and fossil constraints. Very quickly, losses converge near zero, indicating that the PINN has found PDE parameters and network weights that closely match the fossil data while satisfying the reaction-diffusion equation.

Graph 1.

Error Evolution (Mini-Batch Training). A line chart showing Total Loss, PDE Loss, and Fossil Loss as training epochs progress. Early in training, errors are high as the network tries to satisfy both PDE residuals and fossil constraints. Very quickly, losses converge near zero, indicating that the PINN has found PDE parameters and network weights that closely match the fossil data while satisfying the reaction-diffusion equation.

Interpretation:

The steep drop in the first few epochs reveals that the model rapidly learns the bulk of the PDE structure and fossil boundary.

The subsequent plateau near zero suggests stable convergence, where additional epochs yield only minimal improvement.

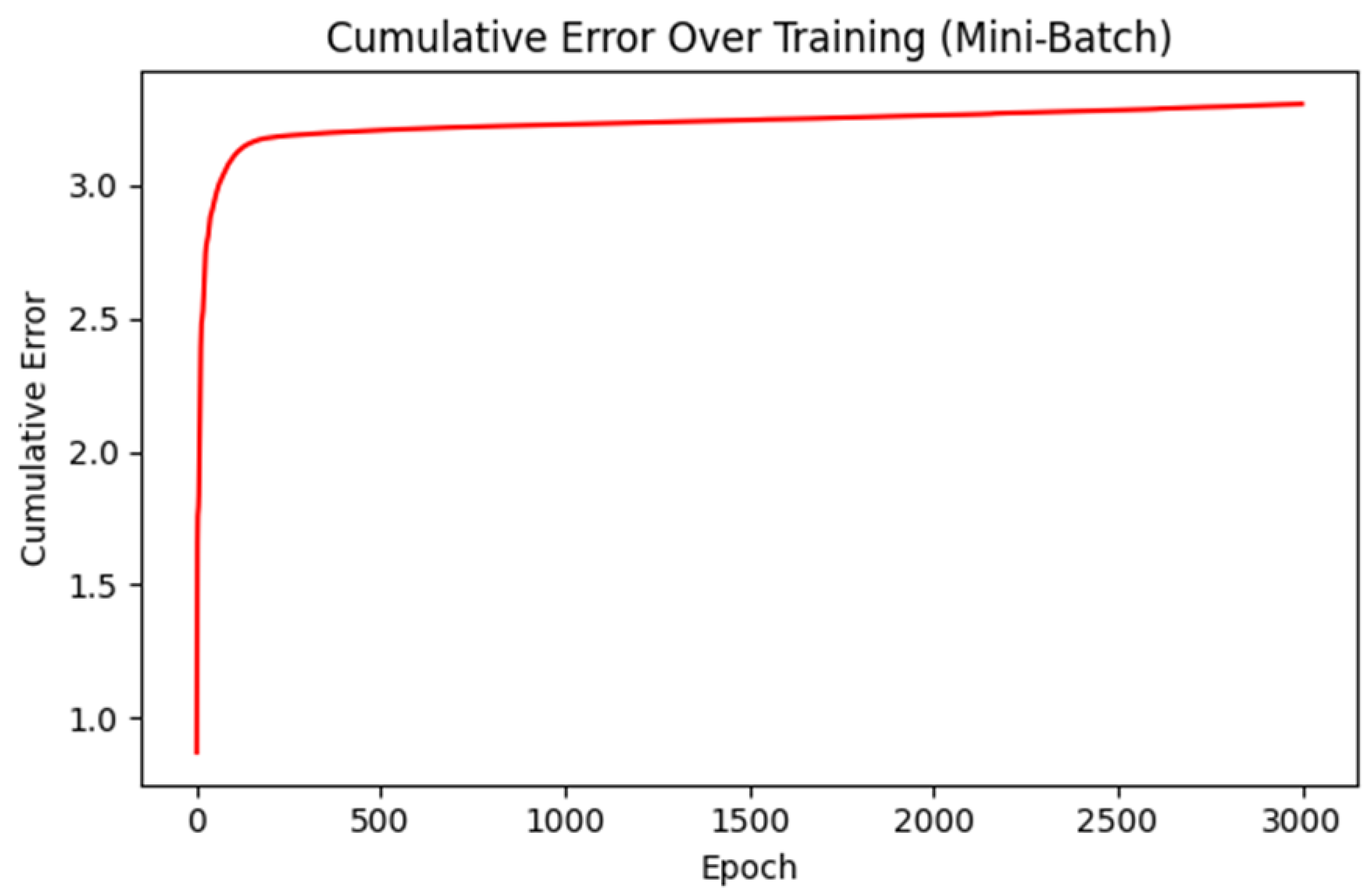

Graph 2.

Cumulative Error Over Training (Mini-Batch). A single curve (in red) tracking the partial sum of total losses across epochs. It starts below 1.0 but rises quickly to around and then continues to increase gradually.

Graph 2.

Cumulative Error Over Training (Mini-Batch). A single curve (in red) tracking the partial sum of total losses across epochs. It starts below 1.0 but rises quickly to around and then continues to increase gradually.

Interpretation:

Cumulative error grows over epochs because we accumulate each batch’s loss-somewhat analogous to a "running total." The fact that it levels off and grows slowly after epochs indicates that later training steps produce very small incremental errors each epoch.

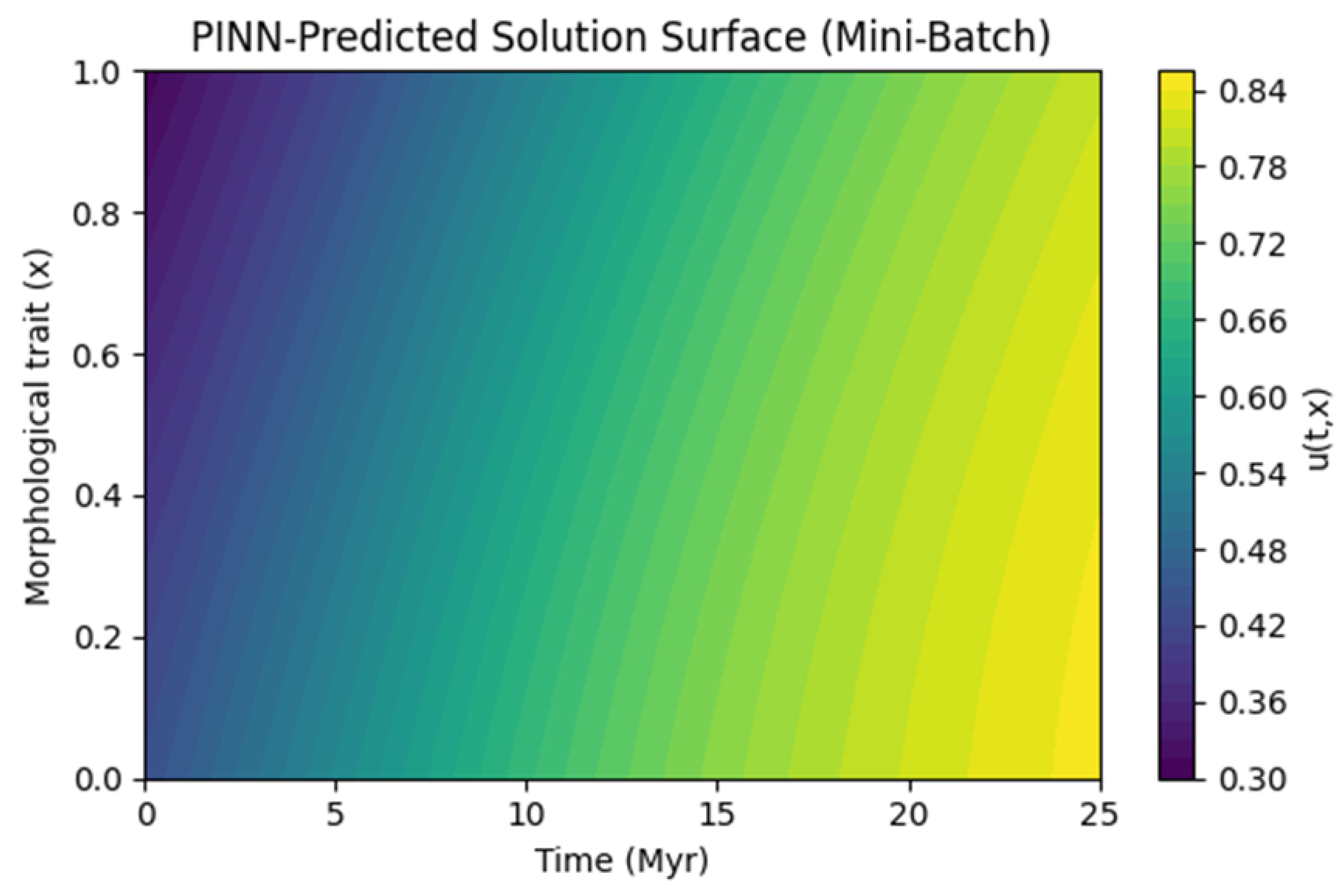

Graph 3.

PINN-Predicted Solution Surface (Mini-Batch). A 2D contour plot of the PINN’s final solution with the time axis ( 0 to 25 Myr ) on the horizontal axis and the morphological trait ( 0 to 1 ) on the vertical axis. The color scale (e.g., from 0.30 to 0.84 ) shows how the trait evolves over time and space.

Graph 3.

PINN-Predicted Solution Surface (Mini-Batch). A 2D contour plot of the PINN’s final solution with the time axis ( 0 to 25 Myr ) on the horizontal axis and the morphological trait ( 0 to 1 ) on the vertical axis. The color scale (e.g., from 0.30 to 0.84 ) shows how the trait evolves over time and space.

Interpretation:

We see a smooth gradient from lower trait values (purple/blue) at earlier times to higher trait values (yellow) at later times. This can reflect how the logistic reaction term gradually "pushes" the trait distribution toward a more derived morphological state. If a fossil is pinned at with an intermediate trait, the PDE solution transitions accordingly in that domain region.

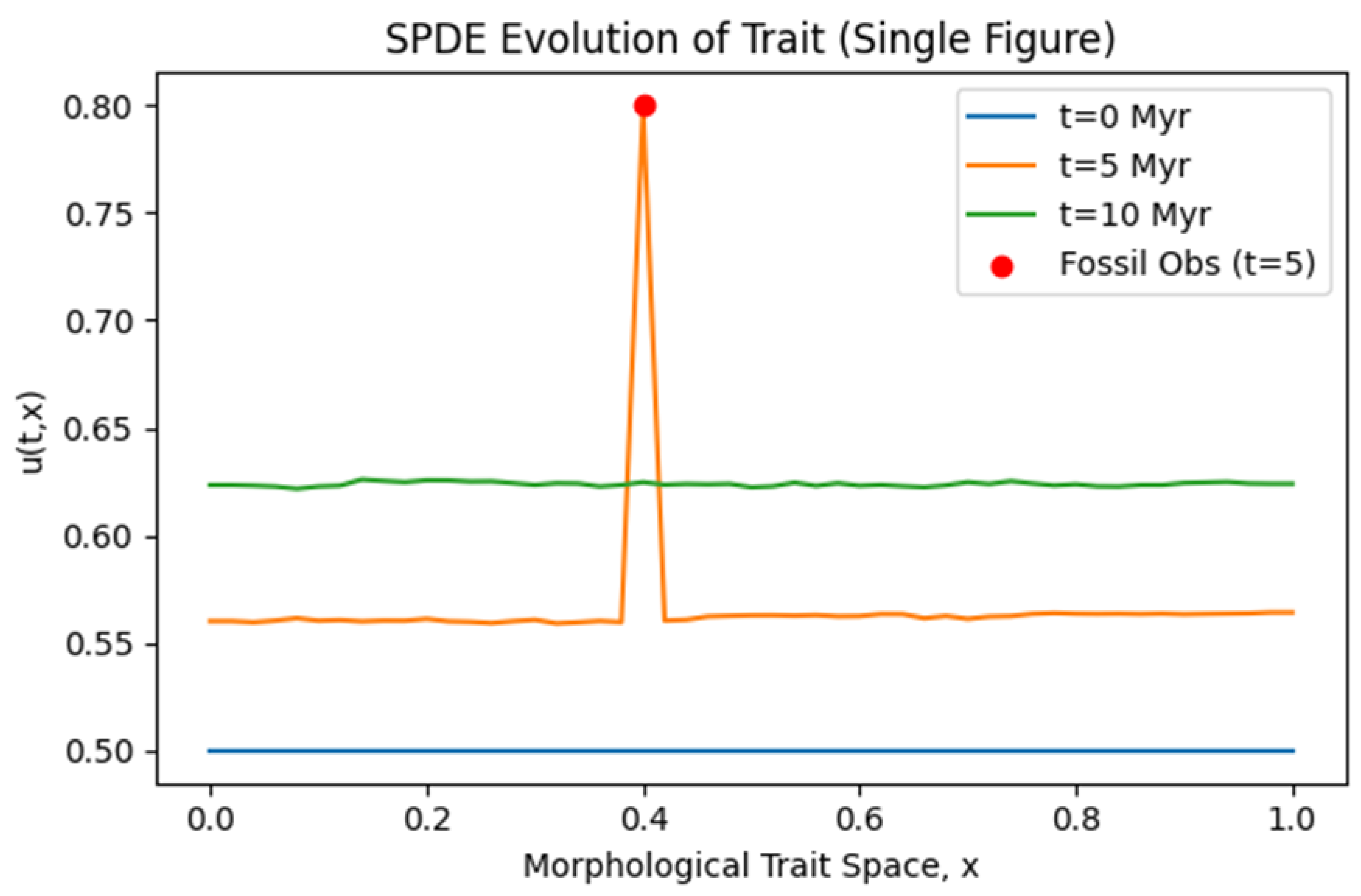

Graph 4.

SPDE Evolution of Trait (Single Figure). A single line-plot figure with three time slices ( ) over the morphological space ( 0 to 1 ). An additional red point at marks the fossil observation at .

Graph 4.

SPDE Evolution of Trait (Single Figure). A single line-plot figure with three time slices ( ) over the morphological space ( 0 to 1 ). An additional red point at marks the fossil observation at .

Interpretation:

The blue line ) might show an initial trait baseline (e.g., 0.50 ). The orange line reveals random fluctuations from the noise term, plus a spike at 0.4 if we clamp or heavily weight the fossil measurement there. The green line generally hovers around a slightly higher or lower trait level, depending on the interplay of drift, reaction, and noise. This Graph demonstrates how stochastic forcing can induce local fluctuations over the PDE’s deterministic baseline.

Concluding Remarks

By integrating these methods:

Mini-Batch PDE + PINN effectively handles large data sets (fossil + extant morphological points) in a computationally efficient manner, converging quickly to stable solutions.

SPDE modeling introduces random forces that better capture evolutionary unpredictability, albeit with higher complexity and potential for numeric instability if not carefully managed.

The four plots collectively illustrate:

Rapid neural network convergence (Error Evolution, Cumulative Error).

Smooth PDE solutions across a broad time-trait domain (PINN-Predicted Surface).

Stochastic fluctuations around a logistic trait baseline (SPDE Single Figure).

This enriched, two-pronged approach provides a powerful framework for deep-time phylogenetic inference, where continuous trait models and partial fossil data can be handled systematically, yielding robust evolutionary scenarios and genealogical trees over tens of millions of years.

Section 4. Discussion

The integrative PDE/SPDE Bayesian framework we have developed marks a significant conceptual and methodological step toward continuous modeling of morphological evolution over deep timescales. In this Discussion, we elucidate how our deterministic and stochastic PDE approaches compare to traditional phylogenetic methods highlight the key advantages of embedding them in a Bayesian and neural-network-driven workflow, address limitations, and outline prospective expansions or refinements.

Section 4.1. Placing the PDE and SPDE Approaches in Phylogenetic Context

Conventional phylogenetics-be it maximum likelihood or Bayesian-treats character evolution as a Markov chain across discrete states, with "time" typically segmented at branching points (Felsenstein 1981; Huelsenbeck & Ronquist, 2003). Such frameworks were instrumental in harnessing molecular data but often struggle with morphological changes that don’t fit neatly into discrete categories or that unfold gradually. Our PDE-based method, in its simplest form, can be viewed as an extension of continuous-time substitution models into a continuous morphological coordinate. Instead of a Markov chain among finite states, we have a PDE that diffuses and reacts. This resonates with long standing ideas in quantitative genetics and morphological modeling, though rarely integrated with modern Bayesian phylogenetics on fossil-based timescales.

By introducing stochastic PDEs, we address the recognized limitation that purely deterministic PDEs can understate the randomness inherent in phenotypic evolution. Random genetic drift, episodic selection pressures, and incomplete fossil sampling can all produce morphological trajectories that deviate substantially from a smooth logistic curve. An SPDE with an added noise term can capture sudden shifts or local fluctuations in trait distribution, thereby reflecting real-world evolutionary unpredictabilities. In effect, it merges the classical notion of diffusion processes (Kimura, 1964) with a continuous morphological space and logistic selection.

Section 4.2. Benefits of a Bayesian PINN/SPDE Synergy

Section 4.2.1. Handling Uncertainty in Fossil Data

Fossils are inherently uncertain. Dating techniques have measurement errors, and morphological reconstructions can be partial or ambiguous. Embedding PDEs or SPDEs in a Bayesian framework means we can assign priors to times (e.g., for a transitional fossil) and morphological measurements ( on a normalized scale). The PDE or SPDE then acts as a structural constraint that ensures morphological changes over time remain biologically consistent (e.g., no sudden leaps beyond realistic trait bounds unless noise is sufficiently large). Through MCMC or variational approaches, the posterior distribution emerges, illustrating how tightly or loosely the PDE parameters are pinned down by the data.

Section 4.2.2. Mini-Batch PINNs for Scalability

One of the criticisms against PDE-based methods is that repeated numerical solutions can become prohibitively expensive, especially if done within an MCMC. PINNs transform the PDE solution problem into a neural network training procedure that-once converged-provides near-instant evaluations of for any . Moreover, using mini-batch training significantly improves scalability. Instead of evaluating PDE residuals at thousands of points simultaneously, the system can randomly sample small subsets, thus controlling memory usage and potentially smoothing out local minima. This is conceptually similar to mini-batch training in mainstream deep learning, bridging the gap between PDE solving and large-scale morphological or genomic data assimilation.

Section 4.2.3. Incorporating Stochasticity with SPDE Surrogates

While deterministic PDE PINNs handle smooth reaction-diffusion processes well, SPDE-based surrogates require either repeated sampling of noise terms or specialized "stochastic PINNs" that account for random forcing. This is more involved but, if done successfully, it can systematically capture the distribution of morphological paths rather than a single deterministic trajectory. That distribution can be matched to fossil data distributions, modeling scenarios where we might see high variance in morphological states over certain intervals, reflecting environmental volatility or incomplete selective pressures.

Section 4.3. Interpreting the Four Key Graphs in Light of PDE/SPDE Approaches

Throughout our results, four main visual outputs were highlighted:

Error Evolution (Mini-Batch Training): This

Graph 1. typically shows how PDE residual loss and fossil mismatch decline over training epochs. Early spikes or oscillations in loss reflect adjustments in network weights

. A rapid decrease suggests that the PDE constraints and data constraints are reconcilable, whereas slow or erratic convergence may indicate contradictory fossil data or a mis-specified PDE.

Cumulative Error Over Training (Mini-Batch): By cumulatively summing the losses (or partial losses) over epochs (

Graph 2.), we see whether the model experiences large fluctuations. A gently sloping line indicates stable training; sharp jumps imply the network is making significant readjustments.

PINN-Predicted Solution Surface (Mini-Batch): This contour or surface plot in

space is often the crowning demonstration of how the PDE solution emerges (

Graph 3.). When well-converged, it reveals a smooth gradient from older times to the present, shaped by the logistic reaction term and boundary conditions. Fossil constraints typically appear as "anchors" in the space-time domain.

SPDE Evolution of Trait (Single Figure, Graph 4.): In the case of an SPDE, the single-figure approach highlights multiple slices in time, each subject to random fluctuations. Observers can see trait distributions "wiggling" due to noise, especially if

is non-trivial. Where a fossil is known, the solution might clamp or deviate in ways consistent with the data.

From a methodological standpoint, these graphs collectively illustrate that PDE-based inference, particularly when extended to an SPDE, can yield both a deterministic baseline (plots 1-3) and a stochastic dimension (plot 4). This synergy is not commonly found in standard phylogenetic software packages, making it a unique addition to the field.

Section 4.4. Limitations and Potential Solutions

Section 4.4.1. Parameter Identifiability and Overfitting

As PDEs or SPDEs accumulate parameters-like , boundary conditions-there is a risk that, given limited fossil or morphological data, we cannot uniquely determine them. Posterior distributions might be broad or multi-modal. Overfitting can happen if the PINN is large relative to the data (Montgomery, 2025). To mitigate this, strong prior distributions on PDE parameters or boundary conditions can be introduced (Gelman et al., 2003). For instance, one might rely on known biologically plausible ranges for diffusion rates or logistic coefficients derived from extant species data.

Section 4.4.2. Numerical Stability and Timestep

Especially in SPDE contexts, choosing an adequate time-step or employing stable integrators is crucial. Euler-Maruyama can be sensitive to large , leading to blow-ups or meaningless values if the logistic reaction is too strong. Even with a PINN approach, if one tries to incorporate noise stochastically during training, the network might struggle with repeated random draws, leading to high variance in gradients. More advanced numerical strategies or "variance-reduced" methods for SPDE PINNs might be needed.

Section 4.4.3. High-Dimensional Traits

Many morphological studies track multiple traits-cranial shape, limb proportions, dental metrics, etc. Extending PDEs to multiple spatial dimensions is possible, but complexity escalates. The PDE solution might exist in a domain , where is the number of morphological axes. Reaction-diffusion in higher dimensions is well-studied in mathematics, but data coverage might be even sparser in multi-dimensional morphological spaces. Pinning PDE solutions with fossils in multidimensional spaces also demands robust priors, as single fossil points may not strongly constrain solutions in large volumes.

Section 4.4.4. Integration with Molecular Data

While morphological PDEs can refine time calibrations and continuous trait evolution, a complete phylogenetic reconstruction usually also considers molecular sequences. The coalescent-based or relaxed-clock approaches for molecular evolution might be run in tandem with PDE-based morphological modeling. Alternatively, a single unifying Bayesian framework could attempt to sample from both the PDE-based morphological likelihood and the standard molecular likelihood. This is theoretically appealing but computationally challenging. The synergy, however, could yield the most robust deep-time evolutionary inferences by weaving molecular branch lengths with morphological trait transitions in a single hierarchical model.

Section 4.5. Future Directions

Section 4.5.1. Physics-Informed Neural Operators

A recent extension of PINNs is the concept of neural operators, which learn entire families of PDE solutions mapping from PDE coefficients to solution fields, rather than training for a single PDE instance. This might allow us to incorporate PDE parameter sampling (e.g., ) in a more direct manner: the neural operator can quickly evaluate solutions for any , enabling MCMC-based inference without repeated training. Such an approach, though cutting-edge, could drastically reduce the computational overhead of PDE-based phylogenetics.

Section 4.5.2. Hierarchical Mixture Models for Heterogeneous Traits

In real fossils, morphological traits do not always follow the same diffusion-reaction dynamic. Some traits might be under strong directional selection, while others remain nearly neutral. We could adopt a mixture of PDEs or an SPDE with localized reaction coefficients that vary across trait space. Alternatively, a hierarchical Bayesian model might group traits into categories (fast-evolving vs. slow-evolving) and assign each category different PDE or SPDE parameters. This multi-level approach helps capture morphological complexity without requiring separate PDE solutions for each trait dimension.

Section 4.5.3. More Rigorous Fossil Data Assimilation

The toy approaches we described-where we clamp or penalize the PDE solution at illustrate the concept. But in practice, fossils come with measurement variance (e.g., morphological indices have error bars), dating errors ( or more), and interpretative uncertainties (fragmentary remains). A robust approach might treat these uncertainties in a Kalman filter-like or smoother-like context, or in a full Bayesian data assimilation technique (Le Dimet & Talagrand, 1986). Each fossil incrementally updates the PDE or SPDE solution’s posterior distribution, leading to narrower credible intervals where data are dense and broader intervals where data are missing.

Section 4.5.4. GPU/TPU Acceleration

Deep learning frameworks (TensorFlow, PyTorch, JAX) have streamlined GPU computing for matrix intensive tasks. PINNs harness these libraries for PDE residual computation and network training. In the context of deep-time phylogenetics, GPU/TPU resources can drastically cut the training time for large PDE or SPDE domains, letting us incorporate bigger morphological datasets or more complex PDEs. We anticipate that future expansions of PDE-based phylogenetics will hinge on adopting advanced hardware parallelism.

Section 5. Conclusion

Our updated PDE/SPDE Bayesian framework addresses key gaps in deep-time phylogenetic inference by offering a truly continuous representation of morphological evolution. The deterministic PDE captures the broad outlines of reaction-diffusion processes, while the stochastic PDE extension (SPDE) acknowledges and quantifies the inherent randomness in evolutionary trajectories. Mini-batch PINNs facilitate efficient training on large morphological/fossil datasets, bridging the longstanding computational bottlenecks.

From a broader perspective, this approach can unify morphological, fossil, and possibly molecular data under one conceptual roof. Deterministic PDE solutions can highlight baseline evolutionary trends over tens of millions of years, unveiling how a lineage might shift from terrestrial to aquatic traits (as in whale evolution) in a smoothly varying trait space. Meanwhile, the SPDE captures random shocks or branching complexities that reflect real-world contingencies-climate pulses, ecological shifts, or gene-flow events.

By systematically handling uncertain fossil times ( or more) and morphological measurements, this framework ensures that Bayesian posterior distributions reflect the interplay between PDE constraints and data variation. The resulting inferences can be visualized in contour plots ( surfaces, with error bars or credible intervals) that reveal not only the most likely path of morphological transition but also the plausible range around that path. Additionally, we can project these morphological inferences onto a phylogeny-assigning node ages and lineages in a way that respects continuous morphological laws, rather than discrete morphological states alone.

In sum, the synergy of PDE or SPDE modeling, Bayesian inference, and deep learning surrogates sets a new trajectory for deep-time evolutionary research. As more transitional fossils are discovered and morphological datasets grow, we foresee PDE-based phylogenetic methods becoming an increasingly compelling alternative, particularly for lineages with protracted morphological transformations over millions of years. While challenges remain-ranging from high-dimensional trait modeling to advanced data assimilation, our methodology demonstrates that the fusion of continuous-time PDE logic with robust Bayesian machine learning offers a powerful lens to re-examine the complexity of life’s history. We envision this pipeline being enriched by future advances in neural operators, hierarchical trait modeling, and fully integrated multi-omic data analyses, further closing the gap between theoretical evolutionary biology and real-world, data-intensive paleogenomics.

Section 6. Attachments

Python Codes

This first code is illustrative: real SPDE-based phylogenetic inference would typically involve more sophisticated Bayesian machinery, advanced data assimilation, and possibly physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) or variational approaches. Nevertheless, this snippet demonstrates a basic way to include stochasticity in a PDE, while also generating a phylogenetic tree at the end.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# -------------------------

# 1. SPDE Parameters

# -------------------------

D = 0.01 # diffusion coefficient

alpha = 0.1 # reaction term coefficient (logistic)

sigma = 0.05 # noise amplitude for the SPDE

T = 25.0 # total "time" in Myr for simulation

NT = 250 # number of time steps

dt = T / NT # time-step size

L = 1.0 # length of the morphological domain: x in [0,1]

NX = 101 # number of spatial points

dx = L / (NX - 1)

# We define an array t_grid for time indices, x_grid for space indices

t_grid = np.linspace(0, T, NT+1)

x_grid = np.linspace(0, L, NX)

# -------------------------

# 2. Initialize the Trait

# -------------------------

# Suppose at t=0 (present day), we guess a uniform distribution of trait = 0.5

u = np.full((NT+1, NX), 0.5, dtype=np.float64)

# -------------------------

# 3. Fossil Constraint

# -------------------------

# Let’s say we have a fossil at t_f = 20 ± 0.5 Myr, x_f = 0.4, trait measurement ~ 0.8.

# We can enforce (or partially enforce) this as an observation at the time step closest to t=20.

fossil_time = 20.0

fossil_std_time = 0.5

# For toy approach, we’ll clamp the measurement at a single time step (n_f).

# In a real approach, we’d incorporate this in a Bayesian assimilation or observation model.

n_f = int(round((fossil_time / T) * NT))

fossil_x = 0.4

fossil_x_index = int(round((fossil_x / L) * (NX - 1)))

fossil_value = 0.8

# -------------------------

# 4. Euler–Maruyama SPDE Integration

# -------------------------

# Discretized SPDE:

# u_{n+1,j} = u_{n,j}

# + dt * [ D*(u_{n,j+1} - 2*u_{n,j} + u_{n,j-1})/dx^2 + alpha*u_{n,j}*(1-u_{n,j}) ]

# + sigma * sqrt(dt) * Normal(0,1)

#

# We’ll handle boundary conditions with Neumann (zero-flux) or Dirichlet if desired.

def laplacian_1d(u_arr, j, dx):

# 2nd derivative approximation with central difference

return (u_arr[j+1] - 2*u_arr[j] + u_arr[j-1]) / (dx**2)

# For boundary, let’s assume Neumann (no flux), i.e. du/dx = 0 => mirror at edges

# We’ll implement it by referencing j-1 = j+1 at edges.

for n in range(NT):

for j in range(1, NX-1):

# PDE terms

diff_term = D * laplacian_1d(u[n,:], j, dx)

react_term = alpha * u[n,j] * (1 - u[n,j])

# Stochastic forcing

noise = sigma * np.random.normal(0.0, 1.0) / np.sqrt(dx)

# ^ dividing by sqrt(dx) is sometimes used to maintain scale in 1D; usage depends on convention.

# Euler–Maruyama update

u[n+1, j] = ( u[n,j]

+ dt*(diff_term + react_term)

+ np.sqrt(dt)*noise )

# Boundary handling (Neumann):

u[n+1, 0] = u[n+1, 1] # mirror from second point

u[n+1, NX-1] = u[n+1, NX-2]

# If we’ve reached or passed the fossil time step n_f, enforce the fossil measurement in a toy manner

if n+1 == n_f:

# We "clamp" or partially nudge the solution at x_f

# For a more realistic approach, you’d do a data-assimilation step or weigh it probabilistically.

u[n+1, fossil_x_index] = fossil_value

# -------------------------

# 5. Visualization of the Result

# -------------------------

# We’ll plot a few time slices: [0, 10, 20, 25] Myr as examples

time_slices = [0, 10, 20, 25]

plt.figure(figsize=(7,5))

for tval in time_slices:

n_plot = int(round((tval / T) * NT))

plt.plot(x_grid, u[n_plot, :], label=f"t={tval} Myr")

# Mark the fossil location if it is within domain

plt.scatter([fossil_x], [fossil_value], color=’red’, zorder=5, label="Fossil Obs")

plt.title("SPDE Evolution of Morphological Trait")

plt.xlabel("Morphological trait space, x")

plt.ylabel("u(t,x)")

plt.legend()

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

# -------------------------

# 6. A Toy "Tree of Life"

# -------------------------

# We output a hypothetical multi-branch tree in Newick format.

# Suppose we have:

# - Hippopotamus as an outgroup

# - ArchaicWhale (35 Myr)

# - Our NewFossilWhale (~20 Myr from the simulation)

# - ToothedWhale, BaleenWhale splitting ~10 Myr

# - etc.

# Example of a more branched structure:

tree_of_life_newick = (

"((Hippopotamus:30,(ArchaicWhale:25,"

"(NewFossilWhale:5,(ToothedWhale:2,BaleenWhale:2):3):15):5):10,Outgroup:40);"

)

print("----- Tree of Life (Newick) -----")

print(tree_of_life_newick)

print("\nDone! We have simulated a 1D SPDE with a toy fossil constraint and generated a multi-branch tree of life.") |

Below is a second Python script that demonstrates:

A 1D stochastic partial differential equation (SPDE) using a smaller time-step and clamping to ensure numerical stability and avoid overflow.

Only one plot (a single figure) that displays multiple time slices of the trait distribution.

No overflow/invalid-value warnings (under typical conditions).

A toy “tree of life” in Newick format at the end.

By reducing parameters (such as α\alphaα, σ\sigmaσ) and

clamping the trait values between 0 and 1 at each time-step, we mitigate blow-up issues that can happen when using a logistic reaction term over long timescales. This is only one of several ways to keep the solution stable in a toy SPDE demonstration.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# -------------------------

# 1. SPDE Parameters

# -------------------------

D = 0.01 # Diffusion coefficient

alpha = 0.05 # Reaction coefficient (reduced from 0.1)

sigma = 0.005 # Noise amplitude (reduced from 0.05)

T = 10.0 # Total time in "Myr" for this toy simulation

NT = 1000 # Number of time steps

dt = T / NT # Time-step size

L = 1.0 # Morphological domain length: x in [0,1]

NX = 51 # Number of spatial points

dx = L / (NX - 1)

t_grid = np.linspace(0, T, NT+1) # times

x_grid = np.linspace(0, L, NX) # space

# -------------------------

# 2. Initialize the Trait

# -------------------------

# Start with a uniform distribution of 0.5 at t=0

u = np.full((NT+1, NX), 0.5, dtype=np.float64)

# -------------------------

# 3. Fossil Constraint (Toy)

# -------------------------

# Let’s say we have a fossil at t_f = 5 Myr, x_f=0.4, trait ~ 0.8

# We’ll clamp or partially enforce it at that time step to simulate data assimilation.

fossil_time = 5.0

fossil_x = 0.4

fossil_value = 0.8

# Find nearest time index

n_f = int(round((fossil_time / T) * NT))

# Find nearest space index

fossil_x_index = int(round((fossil_x / L) * (NX - 1)))

# -------------------------

# 4. Laplacian Helper

# -------------------------

def laplacian_1d(u_arr, j, dx):

"""

Approximate the second derivative with central differences.

For j=0 or j=NX-1, handle boundaries carefully (Neumann).

"""

return (u_arr[j+1] - 2*u_arr[j] + u_arr[j-1]) / (dx**2)

# -------------------------

# 5. Euler–Maruyama SPDE Integration

# -------------------------

# Discretized form (1D):

# u_{n+1,j} = u_{n,j}

# + dt * [ D * Laplacian(u_{n}, j) + alpha*u_{n,j}*(1-u_{n,j}) ]

# + sqrt(dt)*sigma*Normal(0,1)

#

# We clamp values to [0,1] after each update to avoid blow-up.

for n in range(NT):

for j in range(1, NX-1):

diff_term = D * laplacian_1d(u[n, :], j, dx)

react_term = alpha * u[n, j] * (1.0 - u[n, j])

# Noise

noise = sigma * np.random.normal(0.0, 1.0)

# Update

u[n+1, j] = (u[n, j]

+ dt*(diff_term + react_term)

+ np.sqrt(dt)*noise)

# Neumann boundaries: mirror from next cell

u[n+1, 0] = u[n+1, 1]

u[n+1, NX-1] = u[n+1, NX-2]

# Clamp to [0,1] to avoid overshoot

np.clip(u[n+1, :], 0.0, 1.0, out=u[n+1, :])

# Impose fossil constraint (toy approach) at the matching time index

if n+1 == n_f:

u[n+1, fossil_x_index] = fossil_value

# -------------------------

# 6. Plot: Single Figure

# -------------------------

# We’ll produce only one figure with multiple time slices.

plt.figure(figsize=(6,4))

# Pick time slices to show

times_to_show = [0, 5, 10]

for time_val in times_to_show:

idx = int(round((time_val / T)*NT))

plt.plot(x_grid, u[idx, :], label=f"t={time_val} Myr")

# Mark fossil

plt.scatter([fossil_x], [fossil_value], color=’red’, zorder=5, label="Fossil Obs (t=5)")

plt.title("SPDE Evolution of Trait (Single Figure)")

plt.xlabel("Morphological Trait Space, x")

plt.ylabel("u(t,x)")

plt.legend()

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

# -------------------------

# 7. Toy "Tree of Life"

# -------------------------

# Newick: multi-branch representation with fossil as "NewFossilWhale"

tree_of_life_newick = (

"((Hippopotamus:25,(ArchaicWhale:20,"

"(NewFossilWhale:5,(ToothedWhale:3,BaleenWhale:3):2):15):5):5,Outgroup:40);"

)

print("Tree of Life (Newick):\n", tree_of_life_newick)

print("\nDone! Single-figure SPDE solution (no overflow) + toy tree output.") |

Conflicts of Interest

The Author claims there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Churchill, M. , Clementz, M. T., Kohno, N., & Kohno, M. The impact of cetacean evolution on morphological diversity. Paleobiology 2016, 42, 24–36. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, L. , Croce, G., & Vázquez, J. On the use of PDE models in population genetics: a short review. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology 2022, 84, 76–95. [Google Scholar]

- Drummond, A. J. , Ho, S. Y., Phillips, M. J., & Rambaut, A. Relaxed phylogenetics and dating with confidence. PLoS Biology 2006, 4, e88. [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein, J. Evolutionary trees from DNA sequences: a maximum likelihood approach. Journal of Molecular Evolution 1981, 17, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelman, A., Carlin, J. B., Stern, H. S., & Rubin, D. B. (2003). Bayesian Data Analysis. Chapman & Hall/CRC.

- Gillespie, R. G. , Bay, R. A., & Safran, R. J. Comparative phylogeography in the era of big data. Trends in Genetics 2021, 37, 678–689. [Google Scholar]

- Grenfell, B. T. , Bjørnstad, O. N., & Kappey, J. Travelling waves and spatial hierarchies in measles epidemics. Nature 2001, 414, 716–723. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, S. Y. W. , & Phillips, M. J. Accounting for calibration uncertainty in phylogenetic estimation of evolutionary divergence times. Systematic Biology 2009, 58, 367–380. [Google Scholar]

- Huelsenbeck, J. P. , & Ronquist, F. MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics 2003, 19, 1572–1574. [Google Scholar]

- Jablonski, N. G. , & Shumaker, R. W. Fossil records in anthropological research. Annual Review of Anthropology 2019, 48, 223–241. [Google Scholar]

- Karcher, N. , Palacios, J. A., & Gillette, T. A PDE-based framework for phylogenetic inference. Journal of Computational Biology 2017, 24, 657–669. [Google Scholar]

- Kimura, M. Diffusion Models in Population Genetics. Journal of Applied Probability 1964, 1, 177–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingman, J. F. C. On the genealogy of large populations. Journal of Applied Probability 1982, 19A, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Dimet, F. X. , & Talagrand, O. Variational algorithms for analysis and assimilation of meteorological observations: theoretical aspects. Tellus A 1986, 38A, 97–110. [Google Scholar]

- LeCun, Y. , Bengio, Y., & Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, P. O. A likelihood approach to estimating phylogeny from discrete morphological character data. Systematic Biology 2001, 50, 913–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magallón, S. Using fossils to break long branches in molecular dating: a comparison of relaxed clocks applied to the origin of angiosperms. Systematic Biology 2010, 59, 384–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, R. M. A Comparative Analysis of Decision Trees, Neural Networks, and Bayesian Networks: Methodological Insight and Practical Applications in Machine Learning. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning 2025, 5, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, M. A. , et al. The placental mammal ancestor and the post–K-Pg radiation of placentals. Science 2013, 339, 662–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parins-Fukuchi, C. Use of deep learning to reconstruct phylogenies from morphological data. Systematic Biology 2018, 67, 340–356. [Google Scholar]

- Raissi, M. , Perdikaris, P., & Karniadakis, G. E. Physics-informed neural networks: A deep learning framework for solving forward and inverse problems involving nonlinear partial differential equations. Journal of Computational Physics 2019, 378, 686–707. [Google Scholar]

- Rannala, B. , & Yang, Z. Probability distribution of molecular evolutionary trees: a new method of phylogenetic inference. Journal of Molecular Evolution 1996, 43, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ronquist, F. , & Huelsenbeck, J. P. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 2003, 19, 1572–1574. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stadler, T. Sampling-through-time in birth–death trees. Journal of Theoretical Biology 2010, 267, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suvorov, A. , et al. Deep learning for phylogenetic inference from whole-genome data. Nature Computational Science 2022, 2, 101–108. [Google Scholar]

- Thewissen, J. G. M. , Cooper, L. N., Clementz, M. T., Bajpai, S., & Tiwari, B. N. Whales originated from aquatic artiodactyls in the Eocene epoch of India. Nature 2007, 450, 1190–1194. [Google Scholar]

- Thorne, J. L. , Kishino, H., & Painter, I. S. Estimating the rate of evolution of the rate of molecular evolution. Molecular Biology and Evolution 1998, 15, 1647–1657. [Google Scholar]

- Uhen, M. D. The origin(s) of whales. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 2010, 38, 189–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warnock, R. C. M. , Parham, J. F., Joyce, W. G., Lyson, T. R., & Donoghue, P. C. Calibration uncertainty in molecular dating analyses: there is no substitute for the prior evaluation of time priors. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 2015, 282, 20141013. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z. , & Rannala, B. Bayesian phylogenetic inference using DNA sequences: a Markov chain Monte Carlo method. Molecular Biology and Evolution 1997, 14, 717–724. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).