Submitted:

16 January 2025

Posted:

17 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

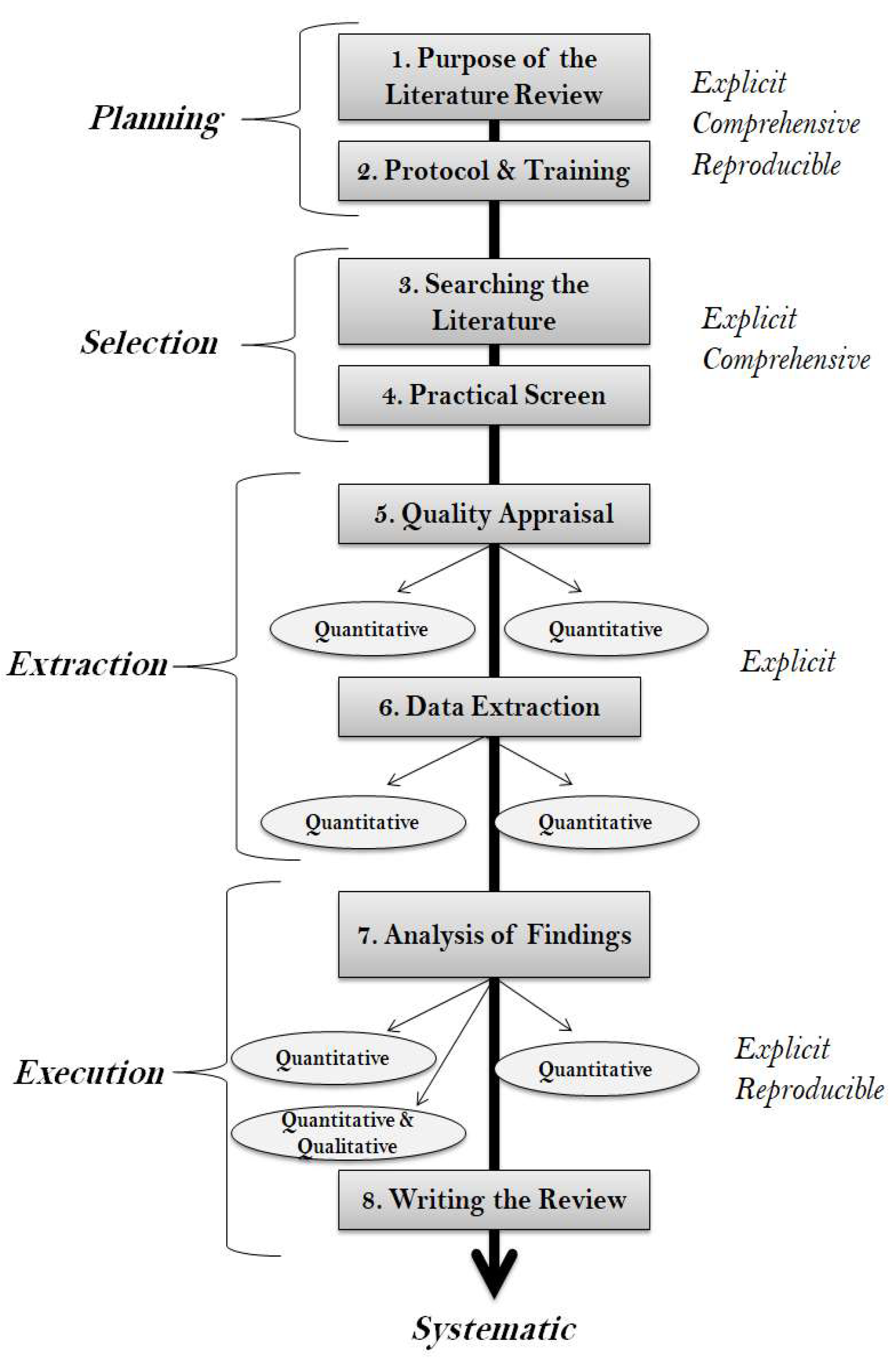

2. Research Aim & Methodology

- The sources and search strings for searching literature.

- The practical screen criteria (content, language, year range, etc).

- The quality appraisal criteria (methodological quality, argumentation analysis).

- The data extraction method for storing details of the final list of articles.

- The method for the analysis of findings.

- The process of writing the SLR, using the synthesis of extracted information.

3. SLR Basics

3.1. Practical Screening

3.2. Quality Appraisal

4. Identification of Systematic BPR Methodologies

- According to the IEEE Std 1362-1998 [76], a system is defined as “a collection of interacting components organized to accomplish a specific function or set of functions within a specific environment”.

- According to the IEEE Std 1232-2002 [77], a system is defined as “a collection of interacting, interrelated, or interdependent elements forming a collective, functioning entity”.

5. Examination of Generalizability

- 7.

- Type: Does it implement different Business Process Change (BPC) types (e.g. BPR, BPI, BPO) or focuses on particular ones?

- 8.

- Notation: Is it applicable to various process modelling notations or limited to a specific/custom representation method?

- 9.

- Objectives: Is there versatility and flexibility in the definition of improvement / optimisation objectives? Are they predefined or can they be customized?

- 10.

- Heuristics: Are different redesign heuristics considered?

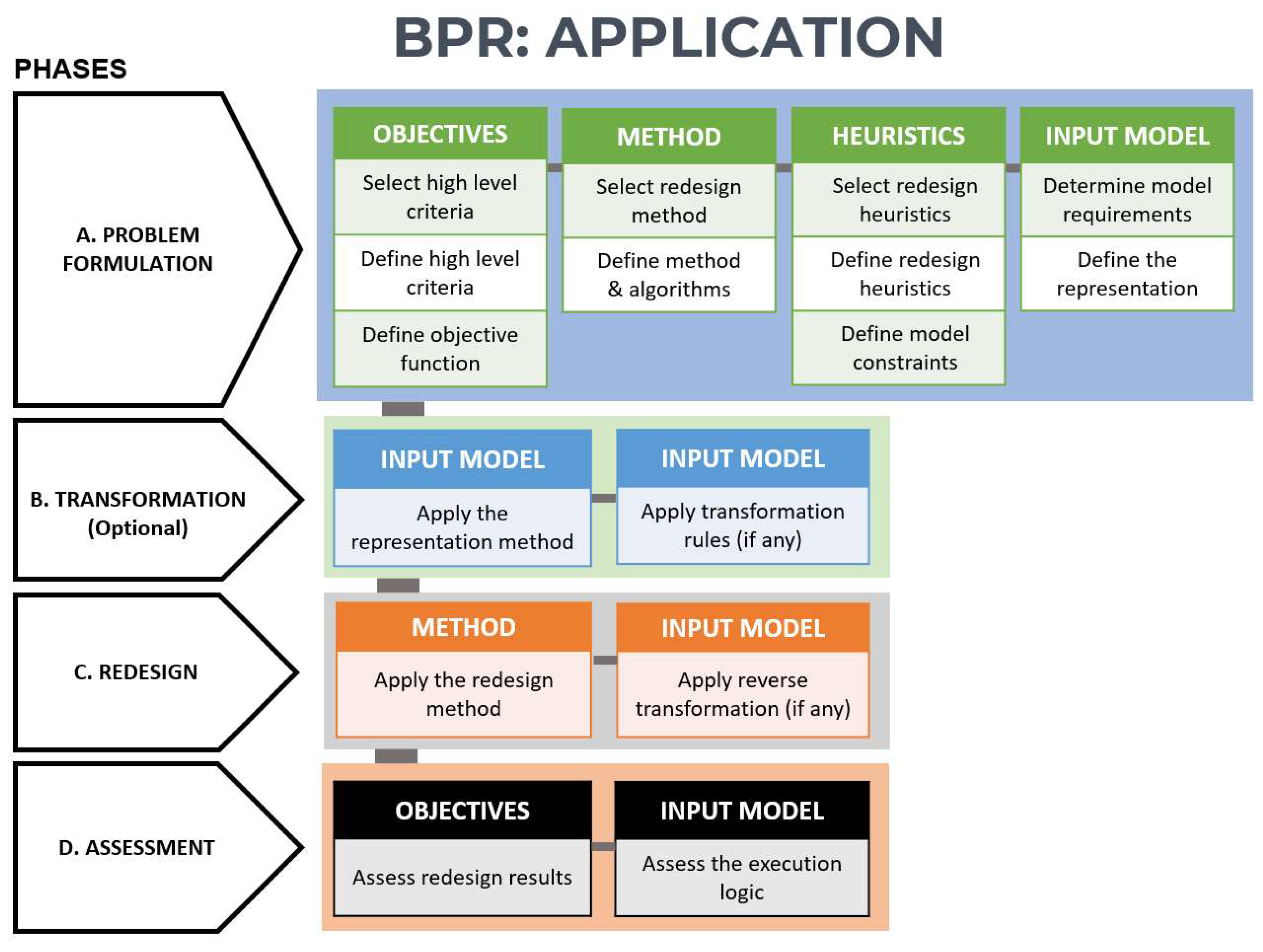

6. A Roadmap for systematic and generalizable methods

7. Discussion and Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Becker, J.; Kugeler, M.; Rosemann, M. Process Management: A Guide for the Design of Business Processes; Springer Science & Business Media, 2013; ISBN 978-3-540-24798-2.

- Jennings, N.R.; Faratin, P.; Johnson, M.J.; Norman, T.J.; O’brien, P.; Wiegand, M.E. Agent-Based Business Process Management. International Journal of Cooperative Information Systems 1996, 5, 105–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weske, M. Business Process Management: Concepts, Languages, Architectures; 2nd ed. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, H.; Fingar, P. Business Process Management: The Third Wave; Meghan-Kiffer Press Tampa, 2003; Vol. 1;

- Tsakalidis, G.; Vergidis, K. Towards a Comprehensive Business Process Optimization Framework.; IEEE: Thessaloniki, Greece, 2017; Vol. 1, pp. 129–134. [Google Scholar]

- Mendling, J.; Decker, G.; Hull, R.; Reijers, H.A.; Weber, I. How Do Machine Learning, Robotic Process Automation, and Blockchains Affect the Human Factor in Business Process Management? Communications of the Association for Information Systems 2018, 43, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendling, J.; Weber, I.; Aalst, W.V.D.; Brocke, J.V.; Cabanillas, C.; Daniel, F.; Debois, S.; Ciccio, C.D.; Dumas, M.; Dustdar, S. Blockchains for Business Process Management-Challenges and Opportunities. ACM Transactions on Management Information Systems (TMIS) 2018, 9, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szelągowski, M. Evolution of the BPM Lifecycle. In Proceedings of the Federated Conference on Computer Science and Information Systems; 2018; pp. 205–211. [Google Scholar]

- Tsakalidis, G.; Vergidis, K.; Kougka, G.; Gounaris, A. Eligibility of BPMN Models for Business Process Redesign. Information 2019, 10, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumas, M.; Rosa, M.L.; Mendling, J.; Reijers, H.A. Fundamentals of Business Process Management; 2013th edition; Springer: Berlin, 2013; ISBN 978-3-642-43473-0. [Google Scholar]

- Seethamraju, R.; Marjanovic, O. Role of Process Knowledge in Business Process Improvement Methodology: A Case Study. Business Process Management Journal 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, C.C.; Ngai, E.W. IT Infrastructure Capabilities and Business Process Improvements: Association with IT Governance Characteristics. Information Resources Management Journal (IRMJ) 2007, 20, 25–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizzon, J.S.; Carmo, L.F.R.R.S. do; Ceryno, P.S.; Fiorencio, L. Business Process Redesign: An Action Research. Gest. Prod. 2020, 27, e4305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zellner, G. A Structured Evaluation of Business Process Improvement Approaches. Business Process Management Journal 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, A. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper; Sage publications, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cognini, R.; Corradini, F.; Gnesi, S.; Polini, A.; Re, B. Business Process Flexibility-a Systematic Literature Review with a Software Systems Perspective. Information Systems Frontiers 2018, 20, 343–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoli, C.; Schabram, K. A Guide to Conducting a Systematic Literature Review of Information Systems Research. Sprouts Work. Pap. Inf. Syst 2010, 10, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchenham, B.; Charters, S. Guidelines for Performing Systematic Literature Reviews in Software Engineering. 2007.

- Webster, J.; Watson, R.T. Analyzing the Past to Prepare for the Future: Writing a Literature Review; JSTOR, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.T.; Chuah, K.B. A SUPER Methodology for Business Process Improvement-An Industrial Case Study in Hong Kong/China. International Journal of Operations & Production Management 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, K.K.; Spedding, T.A. An Integrated Multidimensional Process Improvement Methodology for Manufacturing Systems. Computers & Industrial Engineering 2003, 44, 673–693. [Google Scholar]

- Harmon, P. Business Process Change: A Manager’s Guide to Improving, Redesigning, and Automating Processes; Morgan Kaufmann, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y. The Methodology for Business Process Optimized Design. In Proceedings of the IECON’03. 29th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society (IEEE Cat. No. 03CH37468); IEEE, 2003; Vol. 2; pp. 1819–1824. [Google Scholar]

- Reijers, H.A.; Mansar, S.L. Best Practices in Business Process Redesign: An Overview and Qualitative Evaluation of Successful Redesign Heuristics. Omega 2005, 33, 283–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansar, S.L.; Reijers, H.A.; Ounnar, F. BPR Implementation: A Decision-Making Strategy. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Business Process Management; Springer; 2005; pp. 421–431. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen-Vullers, M.; Reijers, H. Business Process Redesign in Healthcare: Towards a Structured Approach. INFOR: Information Systems and Operational Research 2005, 43, 321–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesola, S.; Baines, T. Developing and Evaluating a Methodology for Business Process Improvement. Business Process Management Journal 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen-Vullers, M.H.; Netjes, M.; Reijers, H.A.; Stegeman, M.J. A Redesign Framework for Call Centers. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Business Process Management; Springer; 2006; pp. 306–321. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, H.-Z.; Lu, H.-Y. Applying Cmmi Approach to Business Process Improvement. Electronic Commerce Studies 2006, 4, 97–116. [Google Scholar]

- Vergidis, K.; Tiwari, A.; Majeed, B. Business Process Improvement Using Multi-Objective Optimisation. BT Technology Journal 2006, 24, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalmaris, P.; Tsui, E.; Hall, B.; Smith, B. A Framework for the Improvement of Knowledge-Intensive Business Processes. Business Process Management Journal 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, B. Business Process Improvement Toolbox; Quality Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Abdolvand, N.; Ferdowsi, Z.; Albadvi, A. Towards a Unified Perspective of Business Process Reengineering Methodologies. International journal of technology transfer and commercialisation 2007, 6, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coskun, S.; Basligil, H.; Baracli, H. A Weakness Determination and Analysis Model for Business Process Improvement. Business Process Management Journal 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.; Bali, R.K.; Wickramasinghe, N. A Business Process Improvement Framework to Facilitate Superior SME Operations. International journal of networking and virtual organisations 2008, 5, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siha, S.M.; Saad, G.H. Business Process Improvement: Empirical Assessment and Extensions. Business Process Management Journal 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enabling Simulation – Simulation and Process Improvement Methodology. In Enabling a Simulation Capability in the Organisation; Greasley, A., Ed.; Springer: London, 2008; pp. 59–87. ISBN 978-1-84800-169-5.

- Goel, S.; Chen, V. Integrating the Global Enterprise Using Six Sigma: Business Process Reengineering at General Electric Wind Energy. International Journal of Production Economics 2008, 113, 914–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Su, Q.; Zhao, C.; Chang, L. A Four-Dimensional Framework for Broad Band Business Process Improvement in HT Company. In Proceedings of the 2009 International Conference on Computers & Industrial Engineering; IEEE; 2009; pp. 1160–1164. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Xue, T.; Yang, A. Business Process Continuous Improvement System Based on Workflow Mining Technology. In Proceedings of the 2009 WRI World Congress on Computer Science and Information Engineering; IEEE, 2009; Vol. 5; pp. 414–418. [Google Scholar]

- Samaranayake, P. Business Process Integration, Automation, and Optimization in ERP: Integrated Approach Using Enhanced Process Models. Business Process Management Journal 2009, 15, 504–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limam Mansar, S.; Reijers, H.A.; Ounnar, F. Development of a Decision-Making Strategy to Improve the Efficiency of BPR. Expert Systems with Applications 2009, 36, 3248–3262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagloel, T.Y.; Dachyar, M.; Arfiyanto, F.N. Quality Improvement Using Model-Based and Integrated Process Improvement (MIPI) Methodology. In Proceedings of the Proceeding of the 11th International Conference on QiR (Quality in Research); 2009; pp. 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Harmon, P. Business Process Change: A Guide for Business Managers and BPM and Six Sigma Professionals, Elsevier. 2010.

- Martin, J.; Conte, T.; Knapper, R. Towards Objectives-Based Process Redesign. Available at SSRN 1805503 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, T.A.; Ghose, A.K.; Lê, L.-S. A Framework for Optimizing Inter-Operating Business Process Portfolio. In Information Systems Development; Springer, 2011; pp. 383–396.

- Niedermann, F.; Radeschütz, S.; Mitschang, B. Business Process Optimization Using Formalized Optimization Patterns. In Proceedings of the Business Information Systems; Abramowicz, W., Ed.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2011; pp. 123–135. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, J.; Betz, S.; Conte, T.; Gerhardt, C.; Weinhardt, C. Objectives-Based Business Process Redesign in Financial Planning – A Case Study. In Proceedings of the ECIS 2011 Proceedings; Helsinki, Finland; 11/06 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-González, L.; Ruiz, F.; García, F.; Piattini, M. Improving Quality of Business Process Models. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Evaluation of Novel Approaches to Software Engineering; Springer; 2011; pp. 130–144. [Google Scholar]

- Lodhi, A.; Köppen, V.; Saake, G. Business Process Improvement Framework and Representational Support. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Intelligent Human Computer Interaction (IHCI 2011), Prague, Czech Republic, August, 2011; Springer, 2013; pp. 155–167.

- Martin, J.; Conte, T.; Mazarakis, A. Process Redesign for Liquidity Planning in Practice: An Empirical Assessment. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advanced Information Systems Engineering; Springer; 2012; pp. 581–596. [Google Scholar]

- Mazz, M.; Kumar, M. Structured Method for Business Process Improvement. In Proceedings of the 2012 Third International Conference on Services in Emerging Markets; IEEE; 2012; pp. 183–188. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, S.; Heching, A.R.; Squillante, M.S. A Two-Phase Approach for Stochastic Optimization of Complex Business Processes. In Proceedings of the 2013 Winter Simulations Conference (WSC); IEEE; 2013; pp. 1856–1868. [Google Scholar]

- Darmani, A.; Hanafizadeh, P. Business Process Portfolio Selection in Re-Engineering Projects. Business Process Management Journal 2013, 19, 892–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohrmann, M.; Reichert, M. Demonstrating the Effectiveness of Process Improvement Patterns. In Enterprise, Business-Process and Information Systems Modeling; Springer, 2013; pp. 230–245.

- Riemann, U. Value-Chain Oriented Identification of Indicators to Establish a Comprehensive Process Improvement Framework. arXiv preprint, arXiv:1310.3230 2013.

- Palma-Mendoza, J.A.; Neailey, K.; Roy, R. Business Process Re-Design Methodology to Support Supply Chain Integration. International Journal of Information Management 2014, 34, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzostowski, K.; Gąsior, D.; Grzech, A.; Juszczyszyn, K.; Ko\laczek, G.; Kozik, A.; Rudek, R.; S\lawek, A.; Szczurowski, L.; Świątek, P.R. Business Process Optimization Platform for Integrated Information Systems. Information systems architecture and technology, eds. Jerzy Świątek [i in.]. Wroc\law: Oficyna Wydawnicza Politechniki Wroc\lawskiej 2014, 13–22.

- Vera-Baquero, A.; Colomo-Palacios, R.; Molloy, O. Towards a Process to Guide Big Data Based Decision Support Systems for Business Processes. Procedia Technology 2014, 16, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanović, D.; Slović, D.; Tomašević, I.; Simeunović, B. Model for Selection of Business Process Improvement Methodologies. In Proceedings of the Paper presented at19th International Toulon-Verona Conference on Excellence in Services, Huelva, Spain; 2016; Vol. 5; pp. 453–467. [Google Scholar]

- Mahammed, N.; Benslimane, S.M. Toward Multi Criteria Optimization of Business Processes Design. In Proceedings of the Model and Data Engineering; Bellatreche, L., Pastor, Ó., Almendros Jiménez, J.M., Aït-Ameur, Y., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2016; pp. 98–107. [Google Scholar]

- Ghanadbashi, S.; Ramsin, R. Towards a Method Engineering Approach for Business Process Reengineering. IET Software 2016, 10, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attong, M.; Metz, T. Change or Die: The Business Process Improvement Manual; 1st edition. Productivity Press, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sallos, M.P.; Yoruk, E.; García-Pérez, A. A Business Process Improvement Framework for Knowledge-Intensive Entrepreneurial Ventures. The Journal of Technology Transfer 2017, 42, 354–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avci, M.G.; Selim, H. A Multi-Objective, Simulation-Based Optimization Framework for Supply Chains with Premium Freights. Expert Systems with Applications 2017, 67, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-González, L.; García, F.; Ruiz, F.; Piattini, M. A Case Study about the Improvement of Business Process Models Driven by Indicators. Software & Systems Modeling 2017, 16, 759–788. [Google Scholar]

- Huo, J.; Liu, L. An Optimization Framework of Multiobjective Artificial Bee Colony Algorithm Based on the MOEA Framework. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience 2018, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torkhani, R.; Laval, J.; Malek, H.; Moalla, N. Intelligent Framework for Business Process Automation and Re-Engineering. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Intelligent Systems (IS); IEEE; 2018; pp. 624–629. [Google Scholar]

- AbdEllatif, M.; Farhan, M.S.; Shehata, N.S. Overcoming Business Process Reengineering Obstacles Using Ontology-Based Knowledge Map Methodology. Future Computing and Informatics Journal 2018, 3, 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.A.; Butt, J.; Mebrahtu, H.; Shirvani, H. Analyzing the Effects of Tactical Dependence for Business Process Reengineering and Optimization. Designs 2020, 4, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnasari, A.; Fitrianah, D.; Haji, W.H. BPTrends Redesign Methodology (BPRM) for the Development Disaster Management Prevention Information System. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2020 2nd Asia Pacific Information Technology Conference; 2020; pp. 113–117.

- Skoglund, B.; Perjons, E. Towards a Goal and Problem Based Business Process Improvement Framework–an Experience Report. In Proceedings of the Practice of Enterprise Modelling 2019 Conference Forum. POEM 2019.; Feltus, C., Johannesson, P., Proper, HA; 2020; pp. 64–77. [Google Scholar]

- Truong, T.-M.; Lê, L.-S.; Paja, E.; Giorgini, P. A Data-Driven, Goal-Oriented Framework for Process-Focused Enterprise Re-Engineering. Information Systems and e-Business Management 2021, 19, 683–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, K.K.; Reka, L.; Mullahi, R.; Jani, K.; Taraj, J. Public Services: A Standard Process Model Following a Structured Process Redesign. Business Process Management Journal 2021, 27, 796–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriam-Webster Systematic. Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary.

- IEEE Guide for Information Technology - System Definition - Concept of Operations (ConOps) Document; 1998; pp. 1–24;

- (Replaced) IEEE Standard for Artificial Intelligence Exchange and Service Tie to All Test Environments (AI- ESTATE); 2002; pp. 1–124;

- Hevner, A.; March, S.T.; Park, J.; Ram, S. Design Science Research in Information Systems. MIS quarterly 2004, 28, 75–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T. The Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) for Decision Making. In Proceedings of the Kobe, Japan; 1980; pp. 1–69. [Google Scholar]

- Adesola, S.; Baines, T.S. Developing a Methodology for Business Process Improvement. In Proceedings of the 4th international conference on managing innovative manufacturing; MCB University Press; 2000; pp. 28–35. [Google Scholar]

- Alter, S. Information Systems: A Management Perspective. 1999.

- Jablonski, S.; Bussler, C. Workflow Management: Modeling, Concepts, Architecture and Implementation; Cengage Learning, 1996.

- Berio, G.; Vernadat, F. Enterprise Modelling with CIMOSA: Functional and Organizational Aspects. Production planning & control 2001, 12, 128–136. [Google Scholar]

- Seidmann, A.; Sundararajan, A. The Effects of Task and Information Asymmetry on Business Process Redesign. International Journal of Production Economics 1997, 50, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Team, C.P. Capability Maturity Model® Integration (CMMI SM), Version 1.1. CMMI for systems engineering, software engineering, integrated product and process development, and supplier sourcing (CMMI-SE/SW/IPPD/SS, V1. 1) 2002, 2.

- Niiniluoto, I. Critical Scientific Realism; OUP Oxford, 1999.

- Dooner, M.; Ellis, T.; Swift, K. A Technique for Revealing and Agreeing an Agenda for Process Improvement. Journal of materials processing technology 2001, 118, 216–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, M.; Rautert, T.; Pater, A.J. Business Process Simulation: A Fundamental Step Supporting Process Centered Management. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 31st conference on Winter simulation: Simulation—a bridge to the future-Volume 2; 1999; pp. 1383–1392.

- Kettinger, W.J.; Teng, J.T.; Guha, S. Business Process Change: A Study of Methodologies, Techniques, and Tools. MIS quarterly 1997, 55–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieringa, R.; Heerkens, H.; Regnell, B. How to Write and Read a Scientific Evaluation Paper. In Proceedings of the 2009 17th IEEE International Requirements Engineering Conference; IEEE; 2009; pp. 361–364. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, H.A. The Sciences of the Artificial. 3rd 1996.

- Mingers, J.; Brocklesby, J. Multimethodology: Towards a Framework for Mixing Methodologies. Omega 1997, 25, 489–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seruca, I.; Loucopoulos, P. Towards a Systematic Approach to the Capture of Patterns within a Business Domain. Journal of Systems and Software 2003, 67, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthu, S.; Whitman, L.; Cheraghi, S.H. Business Process Reengineering: A Consolidated Methodology. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 4 th Annual International Conference on Industrial Engineering Theory, Applications, and Practice, 1999 US Department of the Interior-Enterprise Architecture; Citeseer, 2006.

- Malerba, F.; Caloghirou, Y.; McKelvey, M.; Radoševic, S. Conceptualizing Knowledge Intensive Entrepreneurship: Definition and Model. In Dynamics of Knowledge Intensive Entrepreneurship; Routledge, 2015; pp. 43–71.

- Hadka, D. MOEA Framework - A Free and Open Source Java Framework for Multiobjective Optimization, Version 2.13. Available online: http://moeaframework.org/ (accessed on 6 August 2022).

- Huo, J.; Liu, L. An Improved Multi-Objective Artificial Bee Colony Optimization Algorithm with Regulation Operators. Information 2017, 8, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, M.; Champy, J. Reengineering the Corporation: A Manifesto for Business Revolution. Business Horizons 1993, 36, 90–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.A.; Butt, J.; Mebrahtu, H.; Shirvani, H.; Alam, M.N. Data-Driven Process Reengineering and Optimization Using a Simulation and Verification Technique. Designs 2018, 2, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.A.; Butt, J.; Mebrahtu, H.; Shirvani, H.; Sanaei, A.; Alam, M.N. Integration of Data-Driven Process Re-Engineering and Process Interdependence for Manufacturing Optimization Supported by Smart Structured Data. Designs 2019, 3, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmon, P. Chapter 13 - The BPTrends Process Redesign Methodology. In Business Process Change (Second Edition); Harmon, P., Ed.; The MK/OMG Press; Morgan Kaufmann: Burlington, 2007; pp. 353–383. ISBN 978-0-12-374152-3.

- Limam Mansar, S.; Reijers, H.A. Best Practices in Business Process Redesign: Use and Impact. Business Process Management Journal 2007, 13, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendling, J.; Reijers, H.A.; van der Aalst, W.M. Seven Process Modeling Guidelines (7PMG). Information and Software Technology 2010, 52, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanafizadeh, P.; Moosakhani, M.; Bakhshi, J. Selecting the Best Strategic Practices for Business Process Redesign. Business Process Management Journal 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanwersch, R.J.B.; Pufahl, L.; Vanderfeesten, I.; Mendling, J.; Reijers, H.A. How Suitable Is the RePro Technique for Rethinking Care Processes. BETA publicatie: working papers 2015, 468. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, K.; Suh, E.; Kim, K.-Y. Knowledge Flow-Based Business Process Redesign: Applying a Knowledge Map to Redesign a Business Process. Journal of knowledge management 2007, 11, 104–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsakalidis, G.; Nousias, N.; Vergidis, K. BPR Assessment Framework: Staging Business Processes for Redesign Using Cluster Analysis. In Proceedings of the Decision Support Systems XIII. Decision Support Systems in An Uncertain World: The Contribution of Digital Twins; Liu, S., Zaraté, P., Kamissoko, D., Linden, I., Papathanasiou, J., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2023; pp. 97–110. [Google Scholar]

- Tsakalidis, G.; Nousias, N.; Madas, M.; Vergidis, K. Systematizing Business Process Redesign Initiatives with the BPR:Assessment Framework.; IEEE: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 17/06 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ong, A.K.S.; Cleofas, M.A.; Prasetyo, Y.T.; Chuenyindee, T.; Young, M.N.; Diaz, J.F.T.; Nadlifatin, R.; Redi, A.A.N.P. Consumer Behavior in Clothing Industry and Its Relationship with Open Innovation Dynamics during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 2021, 7, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novita, N.; Percunda, A.D.; Chalidyanto, D. Outpatient Service Business Development in an Effort to Reduce Service Time. Jurnal Kesehatan Masyarakat 2023, 19, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popoola, O.A.; Adama, H.E.; Okeke, C.D.; Akinoso, A.E. Cross-Industry Frameworks for Business Process Reengineering: Conceptual Models and Practical Executions. World Journal of Advanced Research and Reviews 2024, 22, 1198–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, S.S.; Nathiya, R. AI-Powered Business Revolution: Elevating Efficiency and Boosting Sales through Cutting-Edge Process Re-Engineering with Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 2024 Second International Conference on Data Science and Information System (ICDSIS); February 2024; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

| Database | Institution | Abbr. |

|---|---|---|

| Google Scholar | GS | |

| ACM Digital Library | ACM | ACM |

| IEEE Xplore | IEEE | IEEE |

| ScienceDirect | Elsevier | ELSV |

| SpringerLink | Springer | SPRG |

| Criteria | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| Accessibility | IC-A1 | The full text of study is digitally accessible. |

| Content | IC-C1 | The study is relevant to the specific RQs. |

| Publication Language | IC-P1 | The study is written in English. |

| Date of Publication | IC-P2 | The study is restricted to date ranges from 2000 to 2022. |

| Publication Type | IC-P3 | The study is book, book chapter, journal article, already published literature review or conference paper. |

| Criteria | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| Artefact Proposal | IC-A2 | Has the study proposed an artefact for the purpose of the RQs? |

| Methodological support | IC-M | Is the proposed artefact based on a defined methodology? |

| Primary Artefact | IC-P4 | Is the proposed artefact the primary approach in literature? |

| Source | Search String | Initial Results | After Practical Screening | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC-A1, IC-P1, IC-P2, IC-P3 | IC-C1 | |||

| GS | “business process" AND ("redesign framework” OR “improvement framework” OR “optimization framework” OR "redesign methodology" OR "improvement methodology" OR "optimization methodology") | 6290 | 212 | 107 |

| “business process" AND ("redesign framework” OR “improvement framework” OR “optimization framework” OR "redesign methodology" OR "improvement methodology" OR "optimization methodology") ~systematic -software process | 1130 | 84 | ||

| “business process" AND "redesign framework” | 225 | 37 | ||

| IEEE | "business process" AND ("redesign framework” OR “improvement framework” OR “optimization framework” OR "redesign methodology" OR "improvement methodology" OR "optimization methodology") | 211 | 50 | |

| ACM | "business process" AND ("process redesign" or "process improvement" OR "process optimization") AND ("framework" OR "methodology")-software process | 221 | 39 | |

| “business process" AND ("redesign framework” OR “improvement framework” OR “optimization framework” OR "redesign methodology" OR "improvement methodology" OR "optimization methodology") -software process | 85 | 13 | ||

| ELSV | “business process" AND ("redesign framework” OR “improvement framework” OR “optimization framework” OR "redesign methodology" OR "improvement methodology" OR "optimization methodology") | 404 | 52 | |

| SPRG | business process AND (“redesign framework” OR “improvement framework” OR “optimization framework” OR “redesign methodology” OR “improvement methodology” OR “optimization methodology”) AND NOT “software process” | 604 | 34 | |

| Number of research items: | 9168 | 521 | 107 | |

| Practical Screening | IC-A2 | IC-M (& IC-C1) | IC-P4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Included Studies | 107 | 83 | 72 | 57 |

| No | Reference | Artefact title or short description | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| AP MD 1 | [20] | SUPER methodology | BPI, Reengineering, Benchmarking |

| AP MD 2 | [21] | Integrated multidimensional process improvement methodology (IMPIM) | Improvement, Reengineering |

| AP MD 3 | [22] | BPR Framework | Redesign |

| AP MD 4 | [23] | The Framework of BP Optimized Design | Optimization |

| AP MD 5 | [24] | BPR Framework | Redesign |

| AP MD 6 | [25] | BPR Implementation Strategy | Redesign |

| AP MD 7 | [26] | BPR Methodology | Redesign |

| AP MD 8 | [27] | BPI Methodology | Improvement |

| AP MD 9 | [28] | Redesign Framework for call centers | Redesign |

| AP MD 10 | [29] | CMMI framework | Improvement |

| AP MD 11 | [30] | BPO framework (bpoF) | Optimization |

| AP MD 12 | [31] | KBPI Framework | Improvement |

| AP MD 13 | [32] | A process for conducting Reengineering – BPI Roadmap | Improvement |

| AP MD 14 | [33] | BP Reengineering Methodology | Reengineering |

| AP MD 15 | [34] | Process Improvement methodology | Improvement |

| AP MD 16 | [35] | BPI Framework | Improvement |

| AP MD 17 | [36] | A conceptual framework for guiding BPI practice | Improvement |

| AP MD 18 | [37] | Process Improvement Methodology through Simulation | Improvement |

| AP MD 19 | [38] | Framework for BP Reengineering | Reengineering |

| AP MD 20 | [39] | Four-dimensional Framework for Enterprise BPI | Improvement |

| AP MD 21 | [40] | BP Continuous Improvement Framework | Improvement |

| AP MD 22 | [41] | Framework: Process Integration, Automation, and Optimization | Optimization |

| AP MD 23 | [42] | BPR Methodology using a decision-making method based on AHP | Redesign |

| AP MD 24 | [43] | Model-Based, Integrated Process Improvement MIPI Methodology | Improvement |

| AP MD 25 | [11] | A knowledge co-creation process that uses collaborative exploration of different scenarios and contexts | Improvement |

| AP MD 26 | [44] | The BPTrends Redesign Methodology | Redesign |

| AP MD 27 | [45] | The Redesign Model | Redesign |

| AP MD 28 | [46] | Framework for Process Portfolio Optimization | Optimization |

| AP MD 29 | [47] | Deep Business Optimization Platform | Optimization |

| AP MD 30 | [48] | Stage-activity BP Reengineering Framework | Reengineering |

| AP MD 31 | [49] | Conceptual Model for BPI | Improvement |

| AP MD 32 | [50] | Framework for BPI and analysis | Improvement |

| AP MD 33 | [51] | Redesign Framework with prior Financial Planning | Redesign |

| AP MD 34 | [52] | Framework for selecting suitable improvement patterns | Improvement |

| AP MD 35 | [53] | Two-stage BPO framework | Optimization |

| AP MD 36 | [54] | Model for selection of appropriate reengineering scenarios | Reengineering |

| AP MD 37 | [55] | Extended Conceptual Framework for Process improvement | Improvement |

| AP MD 38 | [56] | A Comprehensive Process Improvement Framework | Improvement |

| AP MD 39 | [57] | BPR methodological framework for supply chain integration (SCI) | Redesign |

| AP MD 40 | [58] | BPO Methodology (BPOM) | Optimization |

| AP MD 41 | [59] | a BPI methodology | Improvement |

| AP MD 42 | [60] | Model for selecting BPI methodology | Improvement |

| AP MD 43 | [61] | BPO Framework | Optimization |

| AP MD 44 | [62] | BP Reengineering Process (BPRP) Framework | Reengineering |

| AP MD 45 | [63] | BPI Method | Improvement |

| AP MD 46 | [64] | A conceptual framework for BPI in knowledge-intensive entrepreneurial ventures | Improvement |

| AP MD 47 | [65] | A multi-objective simulation-based optimization framework | Optimization |

| AP MD 48 | [5] | A comprehensive BPO framework | Optimization |

| AP MD 49 | [66] | BPMIMA framework for BP model improvement | Improvement |

| AP MD 50 | [67] | Unified Optimization Framework, MOABC Algorithm | Optimization |

| AP MD 51 | [68] | A Framework for BPI and automation | Improvement |

| AP MD 52 | [69] | Process Reengineering Ontology-based knowledge Map (PROM) | Reengineering |

| AP MD 53 | [70] | The Khan–Hassan–Butt (KHB) methodology | Reengineering |

| AP MD 54 | [71] | BPTrends Redesign Methodology (BPRM) | Redesign |

| AP MD 55 | [72] | The BPI framework | Improvement |

| AP MD 56 | [73] | A framework for redesigning BPes | Redesign |

| AP MD 57 | [74] | Process redesign framework (PRF) | Redesign |

| No | AP MD Phases / Stages | Systematic |

|---|---|---|

| AP MD 1 | Select Process, Understand Process, Process Measurement, Process Improvement, Review Process. | X |

| AP MD 2 | Conventional Simulation Study (Productivity), Statistical Process Control (Quality), Activity-Based Costing (Cost), Decision Support Model, BP Reengineering or Improvement (TQM). | X |

| AP MD 3 | Planning, Analysis, Design, Development, Managing | X |

| AP MD 4 | Forming business strategy, BP diagnosis, and determining alternative reengineering blueprints, Forming BPR objectives, BP structurized design and structural optimization, BP assignment optimization, BP evaluation and decision-making, BP implementation. | X |

| AP MD 5 | Customers, Products, BP Operation and Behavioural Views, Organization (Structure, Population), Information and Technology. | X |

| AP MD 6 | The multi-criteria method uses Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) and includes the indicators of the following criteria: Component, Popularity, Impact, Goal, Risk. | X |

| AP MD 7 | Process modeling, Assessment of benefits of redesign heuristics, Selection of redesign heuristic, Creation of the TO-BE model, Selection of scenarios. | X |

| AP MD 8 | Understand business needs, Understand the process, Model & Analyze Process, Redesign Process, Implement New Process, Assess New Process & Methodology, Review Process. | X |

| AP MD 9 | - | |

| AP MD 10 | Customized model tailoring, IDEAL implementation methodology, Evidence assessment principles and suggestions. Maturity levels: Initial, Managed, Defined, Quantitatively Managed, Optimizing. | X |

| AP MD 11 | Framework Input, Optimization with EMOAs, Framework Output. | X |

| AP MD 12 | A foundational theory of knowledge, an ontology for dissecting, describing and discussing BPs, A method for the evaluating and improving of BP performance. | X |

| AP MD 13 | Planning, Reengineering, Transformation, Implementation. | X |

| AP MD 14 | BPR Plan, Supportive Environment, Improvement approaches, Process Management, Change Management, Information and Communication Technology. | X |

| AP MD 15 | Start-up, Self-analysis, Making changes, Feedback. | X |

| AP MD 16 | Vision, Collate and measure, Define and plan BPI, Management awareness, (Management commitment/support and Management education), Training and education in kaizen, (Shop-floor awareness, support and commitment), Check the process. | X |

| AP MD 17 | Specify, Analyze, Monitor. | X |

| AP MD 18 | Build and Communicate Process Map, Measure and Analyse Process Performance, Develop Future Process Design, Enable and Implement Future Process Design. | X |

| AP MD 19 | Process Redesign, Tool Selection, Security Analysis. | X |

| AP MD 20 | Four dimensions: green dimension makes sure the BP green service-oriented and environment-centered; layers dimension ensures the structure optimization; Logic dimension reflects the right route for BPI; Process dimension is used for looking for the root cause of the problems and proposing targeted suggestions. | X |

| AP MD 21 | (1) Info Acquisition, (2) Performance Evaluation, (3) Defects Identification, (4) Model Generation. | X |

| AP MD 22 | BP integration, automation, and optimization. | |

| AP MD 23 | Creative, Structured and Proposed approach. | X |

| AP MD 24 | Understand business needs, Understand the process, Model and analyze the process, Redesign process, Implement new process, Assess new process and methodology, Review new process. | X |

| AP MD 25 | Set of knowledge-management processes (Phases: Analysis, Modeling and Optimization). | |

| AP MD 26 | Understand Project, Analyze BP, Redesign, Implement Redesigned BP, Roll-out. | X |

| AP MD 27 | Envision, Initiate, Diagnose, Redesign, Reconstruct. | X |

| AP MD 28 | Rearranging Tasks within a Process, Restructuring Inter-operating Processes, Checking the Pre-defined Compliance, Calculating the Minimal Change Measures, Calculating the Resulting Optimization Value, Obtaining the Solution. | X |

| AP MD 29 | Data Integration, Process Analytics, Process Optimization. | X |

| AP MD 30 | Envision, Initiate, Diagnose, Redesign, Reconstruct, Evaluation. | X |

| AP MD 31 | Measurement, Evaluation, Redesign. | X |

| AP MD 32 | Data collection, Computation, Representation in BP models, Steps for improvement, and Mechanism to carry out the changes. | X |

| AP MD 33 | Financial Planning Process Prior to Redesign, Key Performance Indicators, Redesign Realization | X |

| AP MD 34 | - | |

| AP MD 35 | Analytical Approach, Simulation-based Optimization Approach. | X |

| AP MD 36 | Selection of strategic processes, Determining best practices for selected strategic processes, Definition of risk and return and measuring degree of change, BPPS. | X |

| AP MD 37 | Organizational objectives, Process improvement objectives (PIOs), Process improvement measures (PIMs). | X |

| AP MD 38 | As-Is evaluation of already existing KPIs / PPIs, Identification of corporate strategic topics, Evaluation of the corporate Value Chain, Selection of the corporate End-to-End processes, Selection of functional KPIs / PPIs, Benchmarking, Development of Root-Cause Analysis. | X |

| AP MD 39 | Top management commitment and vision, Business understanding, Identification of relevant supply chain processes and selection of target for redesign, Definition of objectives for improvement, Understanding the process AS IS, design of process TO BE, Implementation of changes, Evaluation of changes. | X |

| AP MD 40 | Business Analysis, Ontologies, Platform (Software tools). | X |

| AP MD 41 | Define, Configuration, Execution, Control, Diagnosis. | X |

| AP MD 42 | Companies attitude toward change, Process Performance, Process Characteristics and IT, Impact of Stakeholders. | |

| AP MD 43 | Generate random population, Check the constraints, Evaluate the solution, XNSGAII. | X |

| AP MD 44 | Envision, Initiate, Diagnose, Redesign, Implement redesigned processes, roll out the redesigned processes. | X |

| AP MD 45 | Executive Summary, The Process, Vision, Goals, and Objectives, SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats) Analysis, Project Team, Risks and Opportunities, Resources, Next Steps, Conclusion. | X |

| AP MD 46 | Understand the Business Needs, Understand the Process, Model and Analyze the Process, Redesign the Process, Implement New Process, Assess the Improvement Methodology, Review the process. | X |

| AP MD 47 | Initial Solution, Optimization, Simulation, Pareto-optimal solutions | X |

| AP MD 48 | Representing BPs in a quantitative way, Composing BP designs with the use of algorithms, Identifying the optimal processes utilizing the EMOAs, Incorporating pre-processing stages during execution, Testing the application of the developed framework on BPs composed of web services. | X |

| AP MD 49 | Measurement, Evaluation, Redesign. | X |

| AP MD 50 | Problem Formulation, Algorithm Selection, Optimization process, Results Assessment. | X |

| AP MD 51 | Preparing for re-engineering, Analysis of the AS-IS processes and criticality identification, Data Engineering, Design the TO-BE process model. | X |

| AP MD 52 | Preparation and readiness for the organization, Building ontology, Identifying and prioritizing processes, Construction of knowledge structure and source maps, Analyze the maps, Modify the BPs and evaluate the results, Update the ontology. | X |

| AP MD 53 | Process Identification, Process Mapping, Data Collection, and Analysis, Process Verification, Reengineering Phase, Implementation. | X |

| AP MD 54 | Review project plan, Document as-is process, Agree on process name, sub-processes, inputs, outputs, and activities, Identify flaws, Create a chart of relationships, Determine the required characteristics of each activity, Interview people, Document cost and time, Re-focus on objectives, Recommend changes, Summarize in redesign plan, Present and maintain a redesign plan. | X |

| AP MD 55 | A goal model, A problem model, BPI methods, BPI tasks, The relationship model, The action unit pattern. | X |

| AP MD 56 | Problem Relevance, Research Rigor, Design as an Artifact, Design Evaluation, Research contributions, Communication of Research. | X |

| AP MD 57 | Relocate, Regulate, Delegate, Educate/Allocate, Eliminate, Automate. | X |

| No | 1. Can the artefact be applied to generic BPs? | 2. Does the artefact implement different BPC types? | 3. Is the artefact applicable to various process modelling notations? | 4. Does the artefact support the selection of different objectives? | 5. Does the artefact support different redesign heuristics? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AP MD 1 | X | X | X | X | X |

| AP MD 2 | X | X | X | X | X |

| AP MD 3 | ✔ | X | X | X | X |

| AP MD 4 | X | ✔ | X | X | ✔ |

| AP MD 5 | ✔ | X | X | ✔ | ✔ |

| AP MD 6 | ✔ | X | X | ✔ | ✔ |

| AP MD 7 | X | X | X | X | ✔ |

| AP MD 8 | ✔ | X | X | ✔ | X |

| AP MD 9 | X | X | X | ✔ | ✔ |

| AP MD 10 | ✔ | X | X | X | X |

| AP MD 11 | ✔ | X | X | X | X |

| AP MD 12 | ✔ | X | X | X | X |

| AP MD 13 | ✔ | X | X | — | X |

| AP MD 14 | ✔ | ✔ | X | X | X |

| AP MD 15 | ✔ | X | X | X | X |

| AP MD 16 | X | X | X | X | X |

| AP MD 17 | ✔ | ✔ | X | X | X |

| AP MD 18 | ✔ | X | X | X | X |

| AP MD 19 | ✔ | X | X | ✔ | X |

| AP MD 20 | ✔ | X | X | X | X |

| AP MD 21 | ✔ | X | X | ✔ | X |

| AP MD 22 | ✔ | X | X | X | X |

| AP MD 23 | ✔ | X | X | ✔ | ✔ |

| AP MD 24 | ✔ | X | X | X | X |

| AP MD 25 | ✔ | X | — | X | ✔ |

| AP MD 26 | ✔ | — | X | ✔ | X |

| AP MD 27 | ✔ | X | X | X | X |

| AP MD 28 | ✔ | X | X | X | X |

| AP MD 29 | ✔ | X | X | ✔ | ✔ |

| AP MD 30 | ✔ | X | X | X | X |

| AP MD 31 | ✔ | X | X | X | ✔ |

| AP MD 32 | ✔ | X | X | ✔ | X |

| AP MD 33 | ✔ | X | X | ✔ | X |

| AP MD 34 | ✔ | X | X | ✔ | ✔ |

| AP MD 35 | ✔ | X | X | X | X |

| AP MD 36 | ✔ | X | X | X | ✔ |

| AP MD 37 | ✔ | X | X | X | ✔ |

| AP MD 38 | ✔ | X | X | X | X |

| AP MD 39 | X | X | X | ✔ | X |

| AP MD 40 | X | X | X | X | X |

| AP MD 41 | ✔ | X | X | X | X |

| AP MD 42 | ✔ | ✔ | X | ✔ | X |

| AP MD 43 | ✔ | X | X | X | X |

| AP MD 44 | ✔ | X | — | ✔ | X |

| AP MD 45 | ✔ | X | X | ✔ | X |

| AP MD 46 | ✔ | X | X | X | X |

| AP MD 47 | ✔ | X | X | X | X |

| AP MD 48 | X | X | X | X | X |

| AP MD 49 | ✔ | X | X | X | ✔ |

| AP MD 50 | ✔ | X | X | X | X |

| AP MD 51 | ✔ | X | X | X | X |

| AP MD 52 | ✔ | X | X | X | X |

| AP MD 53 | ✔ | X | X | X | X |

| AP MD 54 | ✔ | X | X | X | X |

| AP MD 55 | ✔ | ✔ | X | X | X |

| AP MD 56 | ✔ | X | X | ✔ | X |

| AP MD 57 | ✔ | X | X | X | ✔ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).