1. Introduction

The neuromuscular diseases are a heterogeneous group of nosological entities resulting from a primary or secondary alteration of the skeletal muscle cell. Although they are rare, they represent a significant cause of disability. Neuromuscular diseases can affect various levels of the neuromuscular system, from the spinal cord to peripheral nerves, the neuromuscular junction, and the muscles themselves.

In last decades, there has been a shift in the natural history of neuromuscular diseases largely due to improvements in the diagnosis and treatment of respiratory complications, which are the leading cause of mortality [

1]. Therefore, pulmonary function assessment should be conducted in every patient with a neuromuscular disease, even in the absence of symptoms, and should be monitored throughout follow-up.

The neuromuscular diseases can be classified into different categories based on their characteristics, both anatomically and genetically. However, the classification that has the most significant impact on the standardization of care protocols for these patients is based on their temporal profile, distinguishing between slowly progressive, such as Duchenne muscular dystrophy, and rapidly evolving, the most prominent of which is Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS). In the latter, the pulmonologist plays a crucial role, which is why many hospitals have established Multidisciplinary ALS Units, to enhance the care of these patients.

ALS is an unknown etiology neuromuscular disease characterized by the fast and progressive degeneration of upper and lower motor neurons, usually progressing rapidly over months or a few years, with respiratory involvement determining the prognosis [

2]. The incidence of sporadic ALS in Europe and the United States is estimated to be between 2.7 and 7.4 per 100,000 inhabitants per year. It is more common in males, with an average survival ranging from 20 to 48 months [

3].

The most common initial clinical manifestation (80%) is asymmetric limb weakness, and about 20% begin with bulbar impairment, such as dysarthria or dysphagia [

4]. Only 1-3% will present with respiratory muscle weakness at onset [

4,

5].

The progressive weakness of respiratory muscles is the most important predictor of survival, hence pulmonary function assessment should be performed in all ALS patients and monitored throughout follow-up. The reference tests include spirometry (in both sitting and supine positions), muscle strength tests, and blood gas analysis [

2]. The most commonly used tests are maximum inspiratory pressure (MIP) and the Sniff Nasal Inspiratory Pressure (SNIP) test; however, they show significant variability both between and within patients, limiting their utility for monitoring and predicting the need for non-invasive mechanical ventilation (NIV). Something similar happens with forced vital capacity (FVC), which, while showing good correlation with diaphragmatic involvement, may not be a useful predictor for the initiation of NIV in patients presenting with nocturnal hypoventilation symptoms and preserved FVC values [

2]. Hypercapnia tends to be a late event and is often not useful in the early stages of the disease [

3].

Ultrasound is an excellent tool for the non-invasive evaluation of diaphragm mobility and functionality. Various studies have demonstrated the usefulness of diaphragmatic ultrasound as a comparable evaluation tool to more costly imaging techniques [

6,

7,

8]. Measurements that can be taken of the diaphragm include thickness, thickening fraction, excursion, and velocity [

9].

In ALS, assessing diaphragmatic atrophy, determined by thickness and thickening fraction, is of great interest as it can be related to pulmonary function [

10,

11]. Furthermore, non-invasive mechanical ventilation (NIV) has been shown to increase survival in ALS patients [

12], with some authors pleading for its early initiation [

13]. This decision is based on a combination of symptoms and signs, with forced vital capacity (FVC) being the most recommended parameter for monitoring respiratory function [

14].

Therefore, diaphragmatic ultrasound could be a useful tool for assessing the ventilatory muscle function of ALS patients both in clinical follow-up and in the indication for NIV. It is necessary to compare it with established measurements in clinical guidelines.

The main objective of our study is to evaluate the diaphragmatic ultrasound characteristics of ALS patients and compare them with respiratory function test measurements. Additionally, we aim to analyze if there is any predictive factor between these measurements and the need for NIV.

2. Materials and Methods

A prospective, descriptive, multicenter study (EcoELA) was conducted. Approval was previously requested from the Research Ethics Committees of each participating hospital (CEIM Code: PI 2019-04-289). All patients diagnosed with ALS referred to the specialized NIV clinics at each center between June 2019 and June 2023 were consecutively included. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants after verbal and written information was provided. The participating centers were the Hospital Universitario de Salamanca (HUS), Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias (HUCA), Hospital Universitario Son Llàtzer (HUSLL), Hospital de Manacor (HMAN), and the Hospital Universitario Germans Trias i Pujol (HUGTP), all of them part of the Spanish Public Health System in various regions of the country.

Patients included in the study met the following criteria: to be diagnosed with ALS, referred to the monographic NIV clinic or to be under follow-up and not receiving NIV treatment. Patients actively receiving NIV treatment, those unable to cooperate for testing due to general deterioration, and those who refused to participate in the study were excluded.

Diaphragmatic ultrasound was performed on all patients starting from the first visit to the NIV clinic. In the first visit, and on the same day, firstly was performed the ultrasonography examination and, immediately after, the complete pulmonary and respiratory muscle function tests. Subsequent visits were conducted every 3 months. There were four different reasons for the patients to exit the study: initiation of NIV, clinical worsening, voluntary withdrawal, or death. NIV treatment was initiated for patients as needed based on clinical and blood gas criteria according to the guidelines from the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) [

15], European Respiratory Society and American Thoracic Society (ERS/ATS) [

16] or the European Federation of the Neurological Societies (EFNS) [

17].

Ultrasound examinations were performed in the Interventional Pulmonology Unit of each center by a pulmonologist experienced in thoracic and diaphragmatic ultrasound. For the subcostal approach, only the right hemidiaphragm was assessed thorugh the liver, and a convex probe with frequencies between 3.5 and 5 MHz was used. Otherwise a high-frequency linear probe between 7 and 10 MHz was used for the axillary approach, following the recommendations of the Spanish Society of Pulmonology and Thoracic Surgery (SEPAR) Procedures Manual [

9].

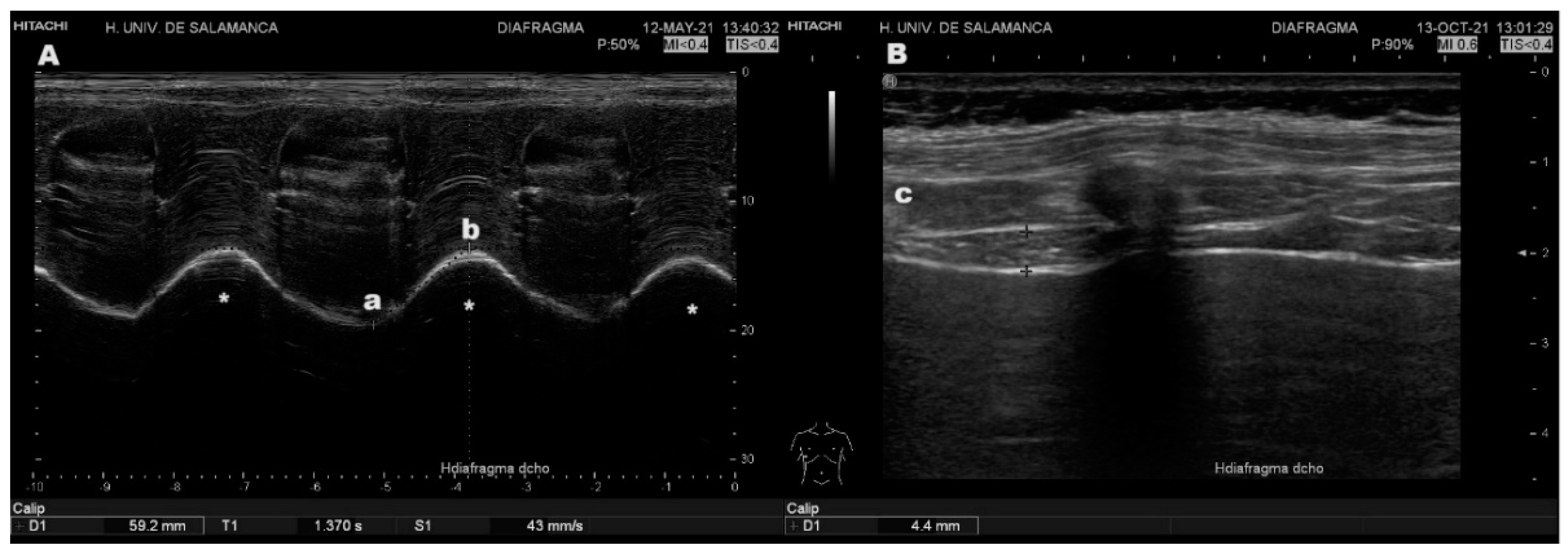

Measurements were taken with the patient in a supine position with the top of the bed elevated around 30 degrees, after remaining in this position for at least 15 minutes. After positioning the patient, explorations were initiated through the subcostal approach, locating the posterior portion of the right hemidiaphragm. Its visibility was verified both in B-mode and M-mode during slow, deep inspirations, before ordering the patient to perform three rapid and deep inspirations, selecting the one with the highest value. Once this measurement was completed, the axillary approach was utilized, between the 8th and 10th intercostal spaces along the mid-axillary line, on both sides. After identifying the diaphragm, the segment closest to its costal insertion was selected during deep inspirations, ensuring no interposition of pulmonary parenchyma. Subsequently, the rapid and deep inspiration maneuvers were repeated to obtain values from the hemithorax where these were the highest (

Figure 1).

Pulmonary function tests were conducted after the diaphragmatic ultrasound on the same day, including spirometry in supine and sitting positions, maximum inspiratory pressure (MIP), maximum expiratory pressure (MEP), Snip test, and baseline arterial blood gas analysis. For the reference values, those from the European Respiratory (ERS) Task Force of the Global Lung Function Initiative of 2012 were used [

18].

After both tests carried out, the variables analysed were: age, sex, reason for study exit (initiation of NIV, clinical worsening or death), diaphragmatic excursion during deep breathing, diaphragmatic thickness at the end of expiration (endE), thickening fraction, FVC, supine FVC, MIP, MEP and Snip test.

The diaphragmatic thickening fraction was calculated as:

An initial sample size calculation was performed to obtain a diagnostic statistical power of 90% and a confidence level of 95% (alpha error of 5%), resulting in a required number of 86 ALS patients.

Statistical analysis was conducted using the SPSS® version 20 software package. Correlations between variables were determined using Pearson's Correlation Coefficient.

3. Results

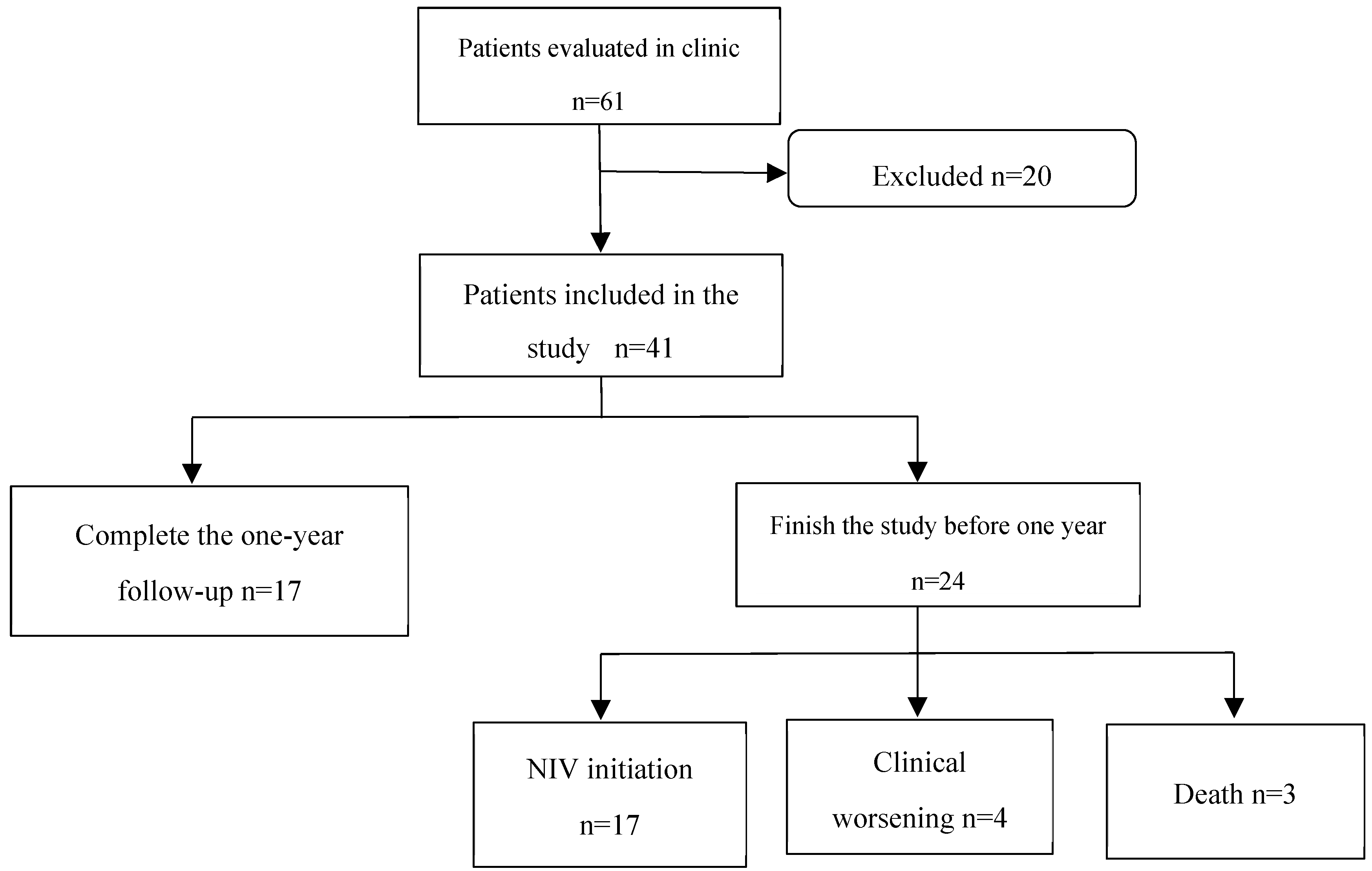

A total of 61 patients, who attended the monographic NIV clinics, were initially evaluated, 41 of them met the study inclusion criteria (

Table 1). Of these, 24 patients (58.5%) did not complete the one-year follow-up, exiting the study for various reasons: 17 (70.8%) due to initiation of NIV, 4 (16.7%) due to clinical worsening without NIV initiation, and 3 (12.5%) due to death (

Figure 2).

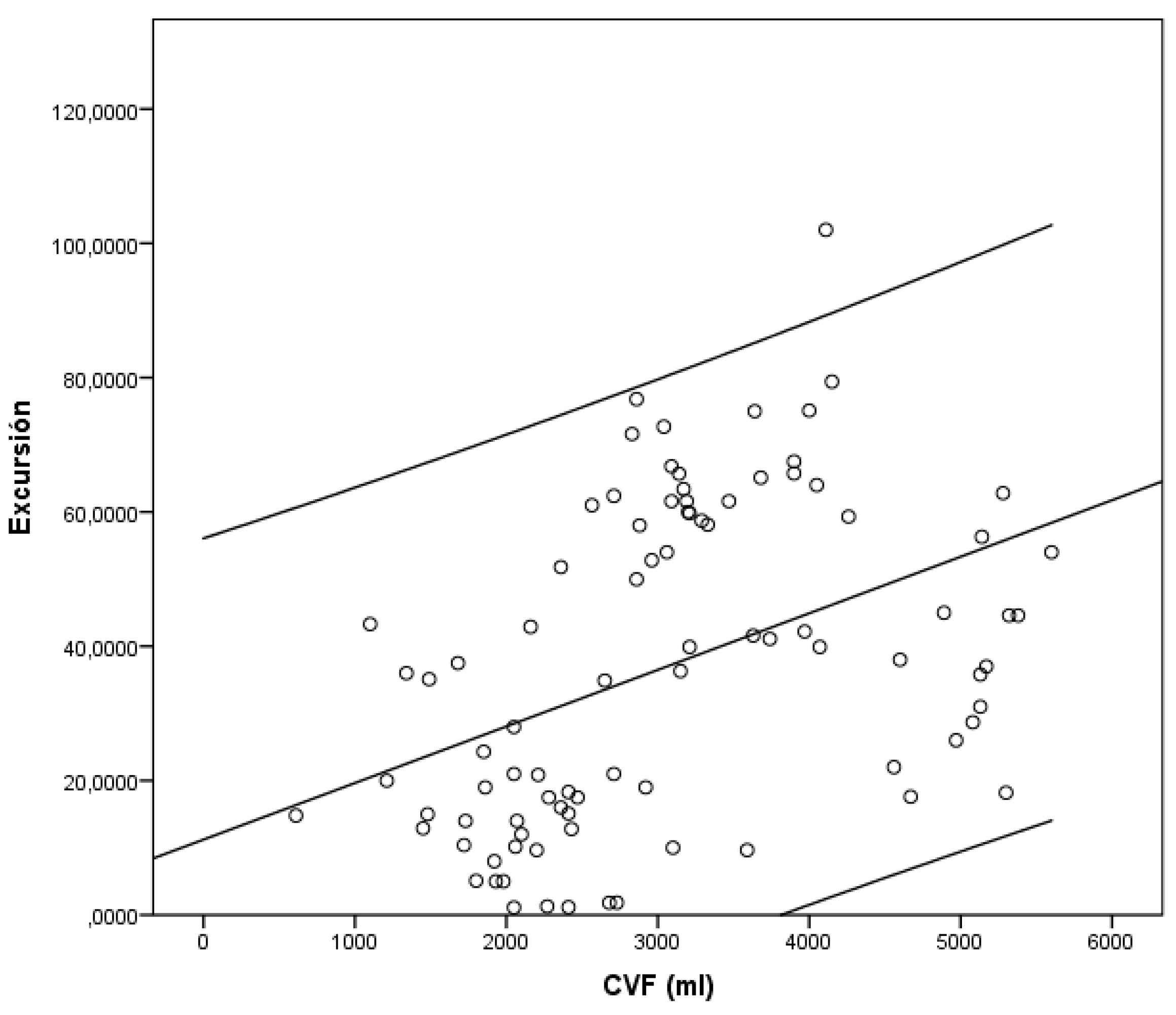

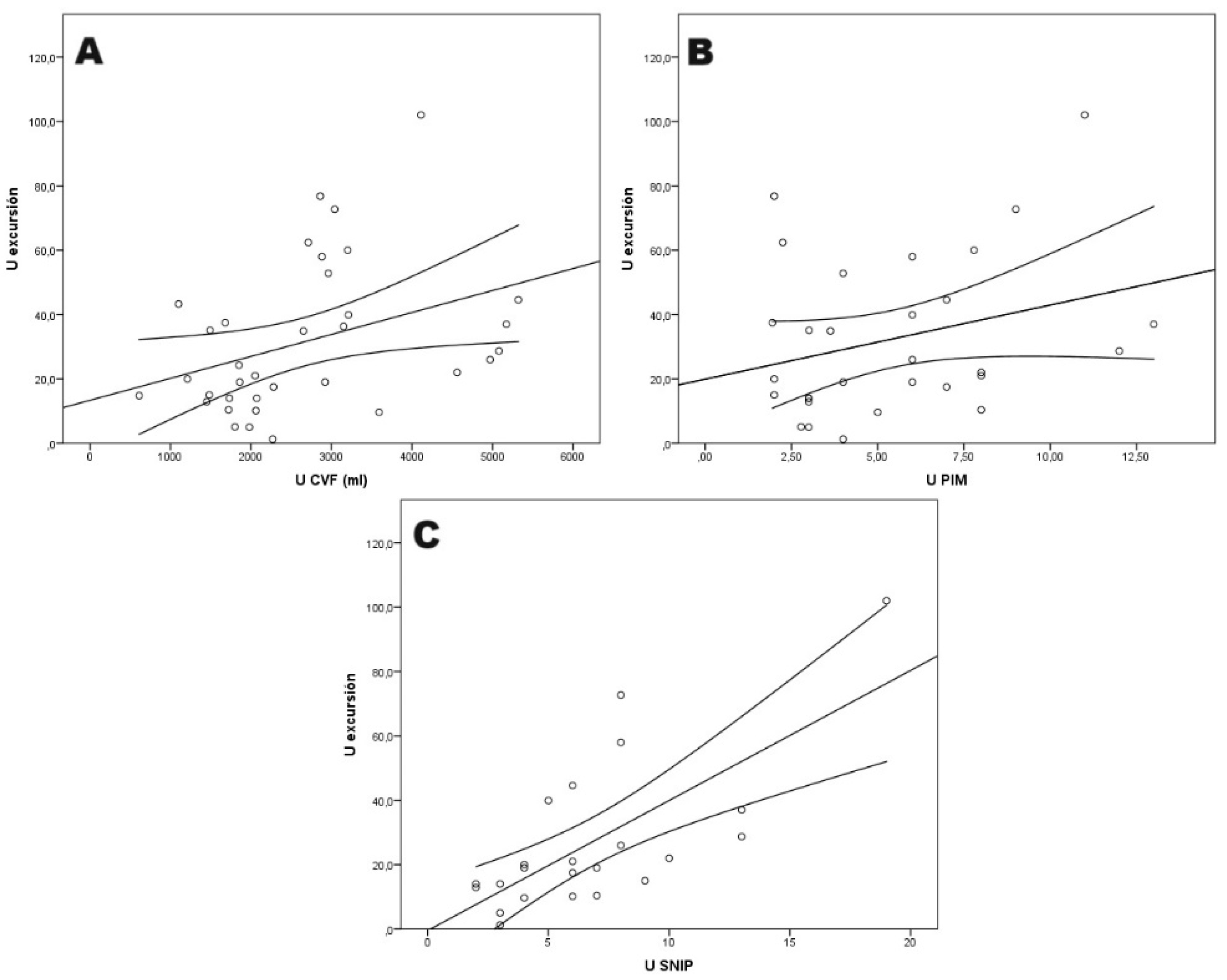

We conducted an analysis to determine if there were any correlation between the different variables obtained by the diaphragmatic ultrasound and those from the pulmonary function, and between these variables and the reason for the study exit due to NIV initiation or death. This analysis of the correlation between thoracic ultrasound and pulmonary function showed us that both excursion and velocity had a statistically significant correlation with FVC and supine FVC (p<0.01) (

Figure 3), and with MIP and the Snip test (p<0.05). The other variables did not show any statistically significant correlations with our data.

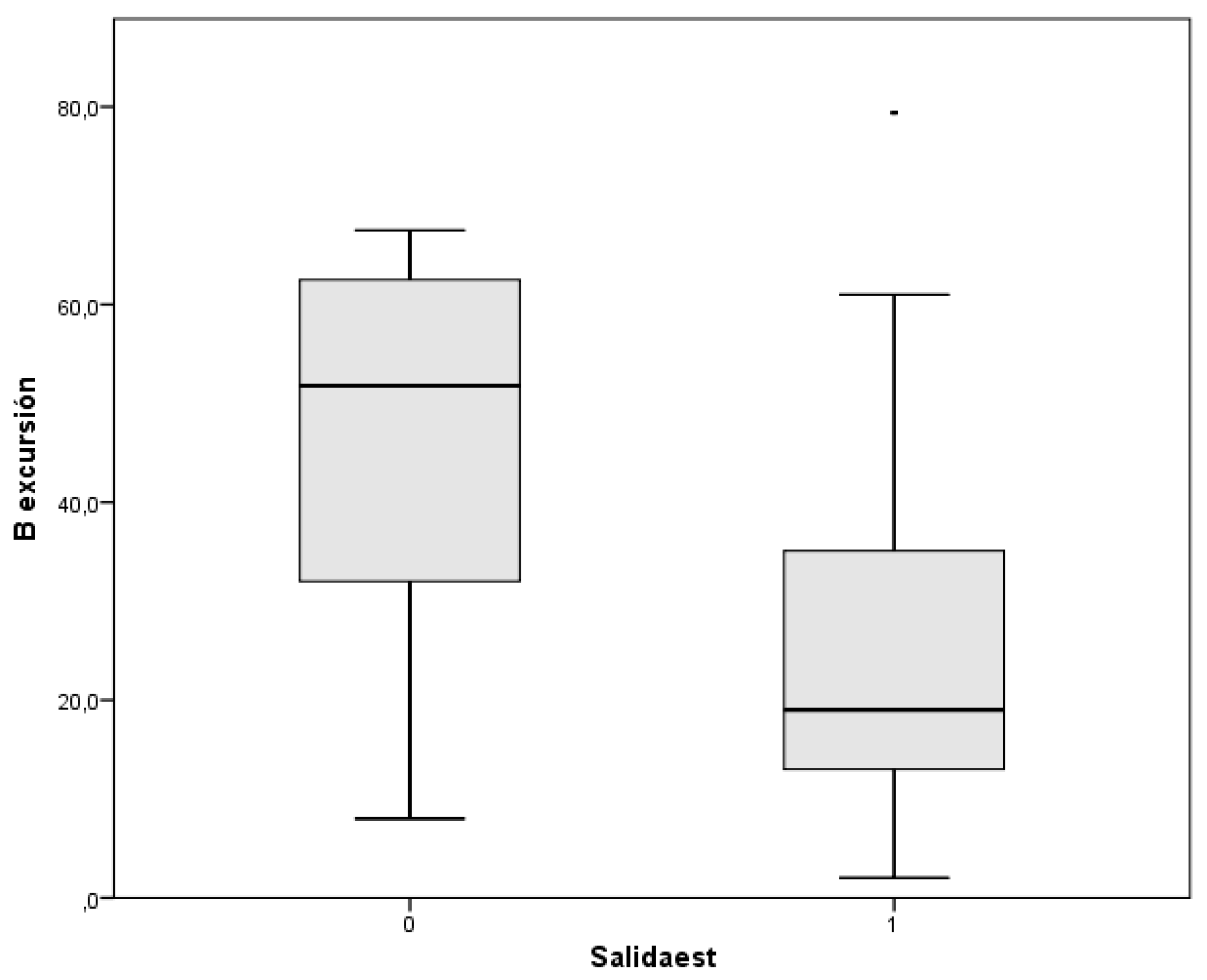

If we put the focus on the study exit due to NIV initiation or death, we looked for the correlation with the lung function and diaphragmatic ultrasound values at both, in the baseline visit (

Table 2) and in the last visit before the patient had to exit the study: at the first visit, the presence of worse pulmonary function values of FVC, supine FVC, and MEP (p<0.01) and diaphragmatic excursion measured by ultrasound (p<0.01) were associated with study exit (

Figure 4).

Additionally, as an indirect value of clinical worsening, at the last visit before the study exit, we also found a correlation between FVC, supine FVC, MIP, MEP, Snip test, and the excursion measured by ultrasound (

Figure 5).

4. Discussion

The difficulty in performing correct pulmonary function maneuvers in some ALS patients has led to the search for alternative methods to assess diaphragmatic function without requiring great patient cooperation. In the literature we can find numerous studies that have attempted to correlate diaphragmatic ultrasound variables with pulmonary function, obtaining good results particularly with the measurements of diaphragmatic thickness and thickening fraction [

19,

20,

21]. For instance, in the study by Hiwatani et al. [

22] in 2013, a correlation was observed between diaphragmatic thickness and FVC, although this was a study not regarding any clinical correlation. It was the first, but not the only study, because subsequent studies [

8,

11,

23] have reached similar conclusions regarding the diaphragm's thickening fraction and its relationship with pulmonary function. According to these data, concordant results were expected in our series, but we did not obtain a significant relationship between diaphragmatic thickness and the thickening fraction with lung function parameters (neither FVC nor MIP or MEP). We believe this is due to the good clinical condition of our patients at diagnosis (mean FVC 83%) and the early initiation of NIV in our centers, thanks to the intense follow-up of these patients in the monographic clinics. That’s why in many cases the NIV which was started based on symptoms and relative losses in pulmonary function, but without letting those patients to descend to severe values in the FVC or inspiratory or expiratory pressures.

However, while the diaphragmatic thickness and the thickening fraction are quite well assessed, this is not the case with the other variables used in diaphragmatic ultrasound: excursion and diaphragm mobility velocity, as they are not evaluated in any studies in ALS patients. Only the study by Boussuges et al. [

24], a quite old study from 2009, a clear correlation was observed between right hemidiaphragm excursion and pulmonary function tests, but just in healthy population. To be able to measure these variables, the patient should be placed in the supine position using an abdominal convex probe with the bed head elevated approximately 30 degrees. When designing our study, we preferred to choose this position to perform a complete diaphragmatic ultrasound, because this allowed us to explore patients who could not be assessed in a seated position. As the study by Boussuges [

24] was able to conclude, also in our study the diaphragmatic excursion during deep inspiration was correlated with FVC.

Regarding the predictive capacity for clinical worsening of diaphragmatic ultrasound, in parallel, we were able to conclude that the excursion was the only variable that can be correlated with the study exit of the patients due either to NIV initiation nor death. We were only able to finde two studies in the literature that prospectively analyze this predictive capacity. The first one, that of Fantini et al. [

25], analyze the utility of a cut-off point for the ratio between expiratory and inspiratory thickness at 0.75, and they were able to predict NIV initiation. Besides, the study of Spiliopoulos et al. [

26] found a predictive capacity for the thickening fraction, with an area under the ROC curve of 0.989. Our study aimed to find a variable that could identify, at diagnosis time, the patients most likely to require NIV and to be useful for determining respiratory failure and the need for it. Among our patients, those who developed clinical deterioration showed significantly lower diaphragmatic excursion both at the baseline visit and at the last visit before study exit, suggesting that if a patient suffers a significant decline in his diaphragmatic excursion may indicate the need for NIV evaluation or, at least, closer monitoring.

Our study has several limitations: the main one being the variability in patient follow-up and the significant loss of visits due to the COVID-19 global pandemic, that made the visits quite complicated to carry up. All procedures and management of the patients were carried out in real clinical practice, so in some visits, not all tests could be completed depending on patient characteristics. Additionally, although each center had only one or two examiners, there is significant inter-observer variability in thoracic ultrasound and between the ultrasound devices used something usually assumed by the investigators in all the studies. Finally, it remains a study with a limited population, due to the prevalence of the disease, needing a more complex cohort study.

5. Conclusions

Assessing diaphragmatic excursion during deep inspiration using ultrasonography can be a useful tool to add to the existing ones for monitoring ALS patients, especially those who cannot perform FVC maneuvers correctly or maintain a seated position. Further studies with larger populations could enhance the validity of excursion as a predictive measure for NIV initiation in ALS patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Iglesias M and Cascón-Hernández J; methodology, Iglesias M and Cascón-Hernández J; software, Iglesias M; validation, Cascón-Hernández J, Cordovilla R, Maimó A, Albaladejo A and Andreo F; formal analysis, Iglesias M; investigation, Iglesias M, Cascón-Hernández J, Maimó A, Albaladejo A, Andreo F, Sánchez A, Maciá M, Martínez I and García R; data curation, Iglesias M; writing—original draft preparation, Iglesias M; writing—review and editing, Cascón-Hernández J, Cordovilla R, Maimó A, Albaladejo A and Andreo F; supervision, Cordovilla R; project administration, Iglesias M; funding acquisition, Iglesias M and Cascón-Hernández J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the SPANISH SOCIETY OF PULMONOLOGY AND THORACIC SURGERY, with the grant: “PII Neumología Intervencionista 2019”

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of SALAMANCA UNIVERSITY HOSPITAL (PI 2019-04-289 of April 2019).

Data Availability Statement

The research data is unavailable due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the colleagues from the pulmonary function units of each participating centre, who were in charge of carrying out the pulmonary function tests, the nursing staff and the rest of the colleagues who have facilitated the work of the researchers. In addition, we would like to thank the collaboration of all the participants, who had to keep a project alive during the COVID-19 pandemic. We would also like to thank the support provided by the Interventional Pulmonology area of SEPAR, both financially and in favouring the collaboration of the centres involved..

References

- Howard, R.S.; Wiles, C.; Hirsch, N.; Spencer, G. Respiratory involvement in primary muscle disorders: assessment and management. Qjm: Int. J. Med. 1993, 86, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedermeyer, S.; Murn, M.; Choi, P.J. Respiratory Failure in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Chest 2019, 155, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiò, A.; Logroscino, G.; Traynor, B.; Collins, J.; Simeone, J.; Goldstein, L.; White, L. Global Epidemiology of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Systematic Review of the Published Literature. Neuroepidemiology 2013, 41, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilbourn, A.J. The ?split hand syndrome? Muscle Nerve 2000, 23, 138–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuwabara, S.; Sonoo, M.; Komori, T.; Shimizu, T.; Hirashima, F.; Inaba, A.; Misawa, S.; Hatanaka, Y. ; Tokyo Metropolitan Neuromuscular Electrodiagnosis Study Group Dissociated small hand muscle atrophy in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Frequency, extent, and specificity. Muscle Nerve 2008, 37, 426–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerscovich, E.; Cronan, M.; McGahan, J.P.; Jain, K.; Jones, C.D.; McDonald, C. Ultrasonographic evaluation of diaphragmatic motion. J. Ultrasound Med. 2001, 20, 597–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Şahin, H.; Doğan, A.; Ekiz, T. Ultrasonographic evaluation of the diaphragm thickness in patients with multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2019, 36, 101369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fantini, R.; Mandrioli, J.; Zona, S.; Antenora, F.; Iattoni, A.; Monelli, M.; Fini, N.; Tonelli, R.; Clini, E.; Marchioni, A. Ultrasound assessment of diaphragmatic function in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Respirology 2016, 21, 932–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Alaejos R, Ríos Cortés AT, Vilaró Casamitjana J. Manual de procedimientos SEPAR. SEPAR 2017. Ecografía torácica.

- Pinto, S.; Alves, P.; Pimentel, B.; Swash, M.; de Carvalho, M. Ultrasound for assessment of diaphragm in ALS. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2016, 127, 892–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayas-Catalán, J.; Hernández-Voth, A.; Villena-Garrido, M.V. Diaphragmatic Ultrasound: An Innovative Tool Has Become Routine. Arch. De Bronc- 2020, 56, 201–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radunovic A, Annane D, Rafiq MK, et al. Mechanical ventilation for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/motor neuron disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Oct 6; 10.

- Vitacca, M.; Montini, A.; Lunetta, C.; Banfi, P.; Bertella, E.; De Mattia, E.; Lizio, A.; Volpato, E.; Lax, A.; Morini, R.; et al. Impact of an early respiratory care programme with non-invasive ventilation adaptation in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Eur. J. Neurol. 2018, 25, 556–e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EFNS Task Force on Diagnosis and Management of Amyotrophic Lateral, Sclerosis; Andersen, P.M.; Abrahams, S.; Borasio, G.D.; de Carvalho, M.; Chio, A.; Van Damme, P.; Hardiman, O.; Kollewe, K.; Morrison, K.E.; Petri, S. EFNS Task Force on Diagnosis and Management of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis; Andersen, P.M.; Abrahams, S.; Borasio, G.D.; de Carvalho, M.; Chio, A.; Van Damme, P.; Hardiman, O.; Kollewe, K.; Morrison, K.E.; Petri, S.; et al. EFNS guidelines on the Clinical Management of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (MALS) – revised report of an EFNS task force. Eur. J. Neurol. 2012; 19, 360–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan A, Frazer-Green L, Amin R, et al.. Respiratory management of patients with neuromuscular weakness: an American College of Chest Physicians clinical practice guideline and expert panel report. Chest 2023; 164: 394–413.

- Rochwerg, B.; Brochard, L.; Elliott, M.W.; Hess, D.; Hill, N.S.; Nava, S.; Navalesi, P.; Antonelli, M.; Brozek, J.; Conti, G.; et al. Official ERS/ATS clinical practice guidelines: noninvasive ventilation for acute respiratory failure. Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 50, 1602426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFNS Task Force on Diagnosis and Management of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis; Andersen, P. M.; Abrahams, S.; Borasio, G.D.; de Carvalho, M.; Chio, A.; Van Damme, P.; Hardiman, O.; Kollewe, K.; Morrison, K.E.; Petri, S.; et al. EFNS guidelines on the Clinical Management of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (MALS) – revised report of an EFNS task force. Eur. J. Neurol. 2011, 19, 360–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quanjer, P.H.; Stanojevic, S.; Cole, T.J.; Baur, X.; Hall, G.L.; Culver, B.H.; Enright, P.L.; Hankinson, J.L.; Ip, M.S.M.; Zheng, J.; et al. Multi-ethnic reference values for spirometry for the 3–95-yr age range: the global lung function 2012 equations. Eur. Respir. J. 2012, 40, 1324–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Aguirre JE, Rivera-Uribe CP, Rendón-Ramírez EJ, et al. Pulmonary Ultrasound and Diaphragmatic Shortening Fraction Combined Analysis for Extubation-Failure-Prediction in Critical Care Patients. Arch Bronconeumol. 2019 Apr;55(4):195-200.

- Harlaar, L.; Ciet, P.; van der Ploeg, A.; Brusse, E.; van der Beek, N.; Wielopolski, P.; de Bruijne, M.; Tiddens, H.; van Doorn, P. Imaging of respiratory muscles in neuromuscular disease: A review. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2018, 28, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobson-Webb, L.D.; Simmons, Z. ULTRASOUND IN THE DIAGNOSIS AND MONITORING OF AMYOTROPHIC LATERAL SCLEROSIS: A REVIEW. Muscle Nerve 2019, 60, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiwatani, Y.; Sakata, M.; Miwa, H. Ultrasonography of the diaphragm in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Clinical significance in assessment of respiratory functions. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2013, 14, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sartucci, F.; Pelagatti, A.; Santin, M.; Bocci, T.; Dolciotti, C.; Bongioanni, P. Diaphragm ultrasonography in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a diagnostic tool to assess ventilatory dysfunction and disease severity. Neurol. Sci. 2019, 40, 2065–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boussuges A, Gole Y, Blanc P. Diaphragmatic motion studied by m-mode ultrasonography: methods, reproducibility, and normal values. Chest. 2009 Feb;135(2):391-400.

- Fantini, R.; Tonelli, R.; Castaniere, I.; Tabbì, L.; Pellegrino, M.R.; Cerri, S.; Livrieri, F.; Giaroni, F.; Monelli, M.; Ruggieri, V.; et al. Serial ultrasound assessment of diaphragmatic function and clinical outcome in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. BMC Pulm. Med. 2019, 19, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spiliopoulos, K.C.; Lykouras, D.; Veltsista, D.; Skaramagkas, V.; Karkoulias, K.; Tzouvelekis, A.; Chroni, E. The utility of diaphragm ultrasound thickening indices for assessing respiratory decompensation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve 2023, 68, 850–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).