Submitted:

13 January 2025

Posted:

14 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Fundamental Aspect of the Binding Strength of S-RBD Mutants

3. Binding Inhibitors for S-RBD with ACE-2

3.1. Lactic Acid

3.2. Acidic Compounds as Inhibitor Candidates

4. Practical Use and Modification of Known Medicines for Inhibiting the Infection

4.1. PF07321332

4.2. Molnupiravir (EIDD-2801)

4.3. Cocktail Inhibitors

4.4. Further Study of Cocktail Applications

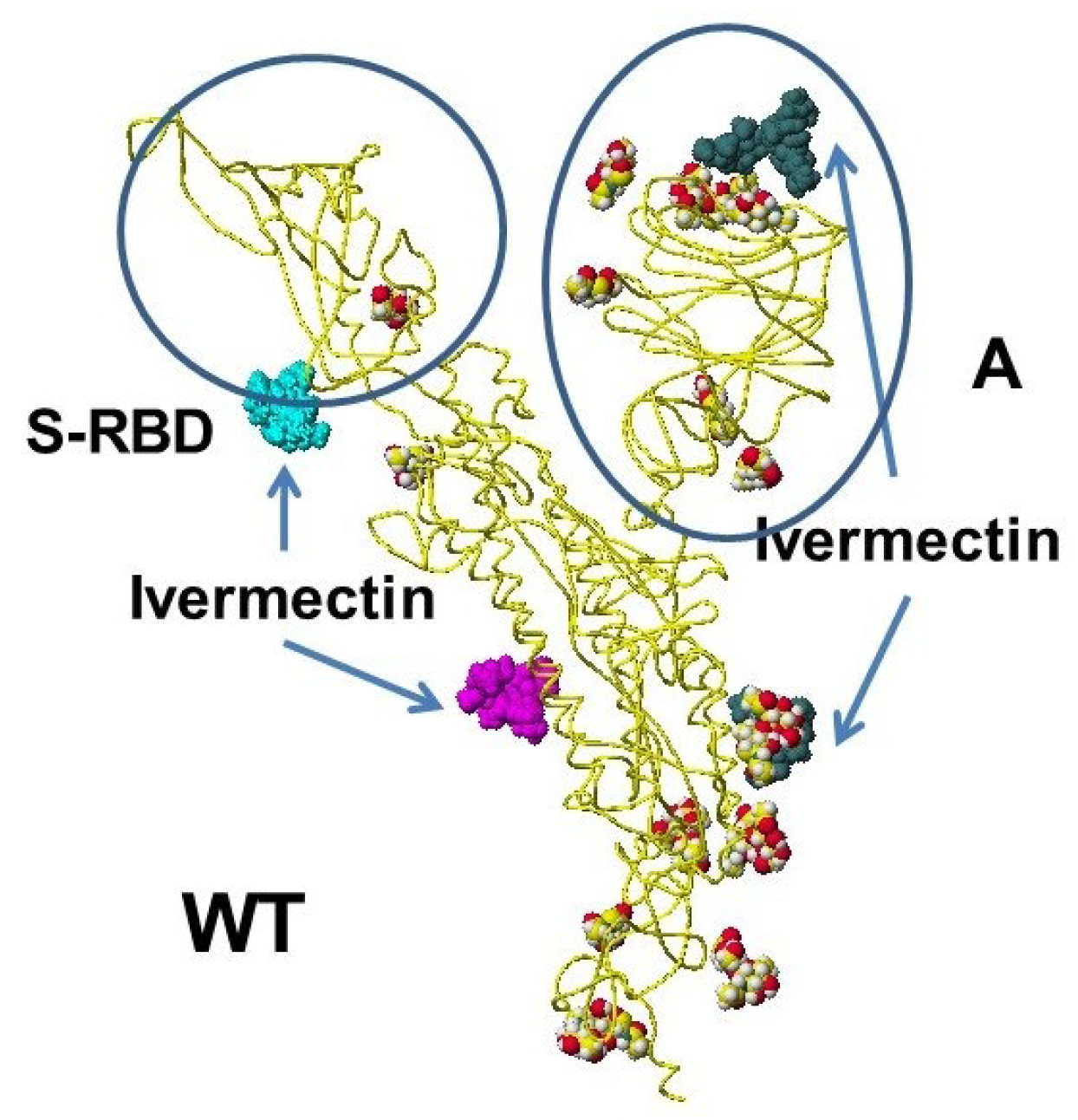

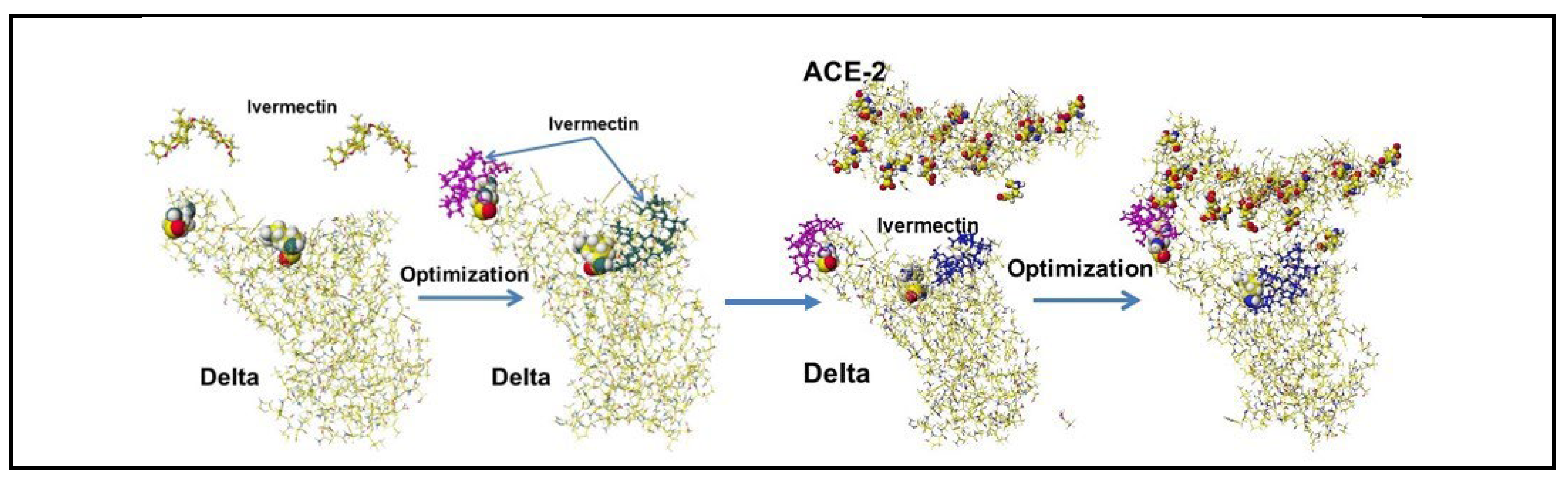

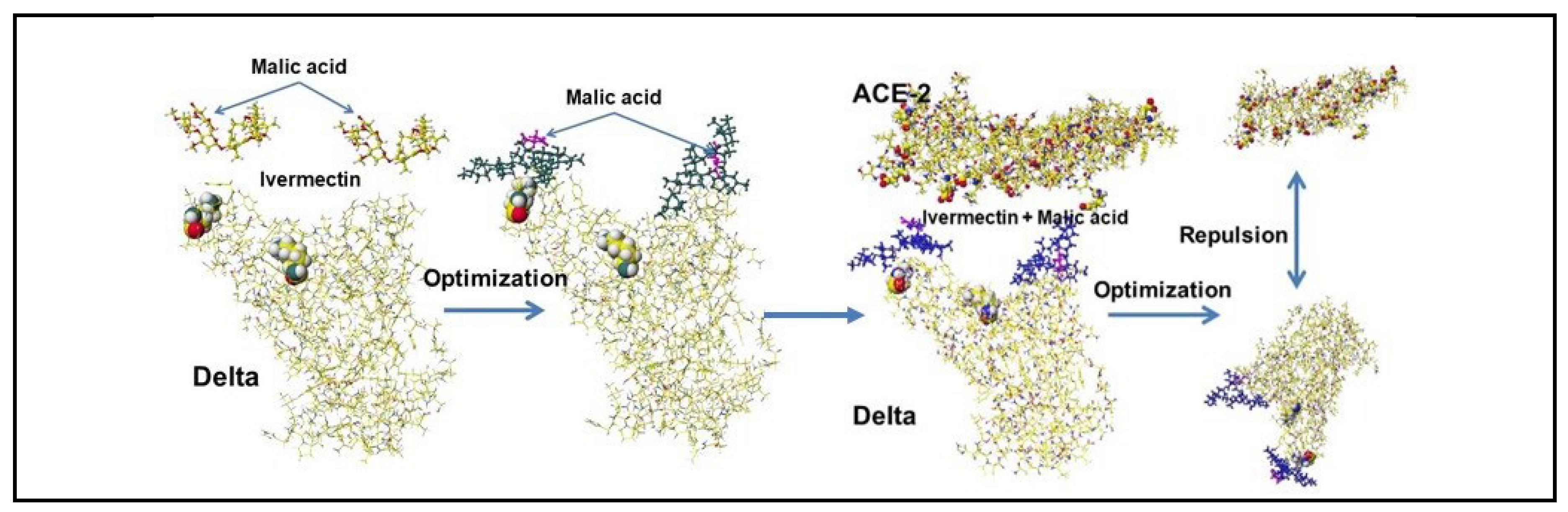

4.5. Ivermectin and Malic Acid Cocktail

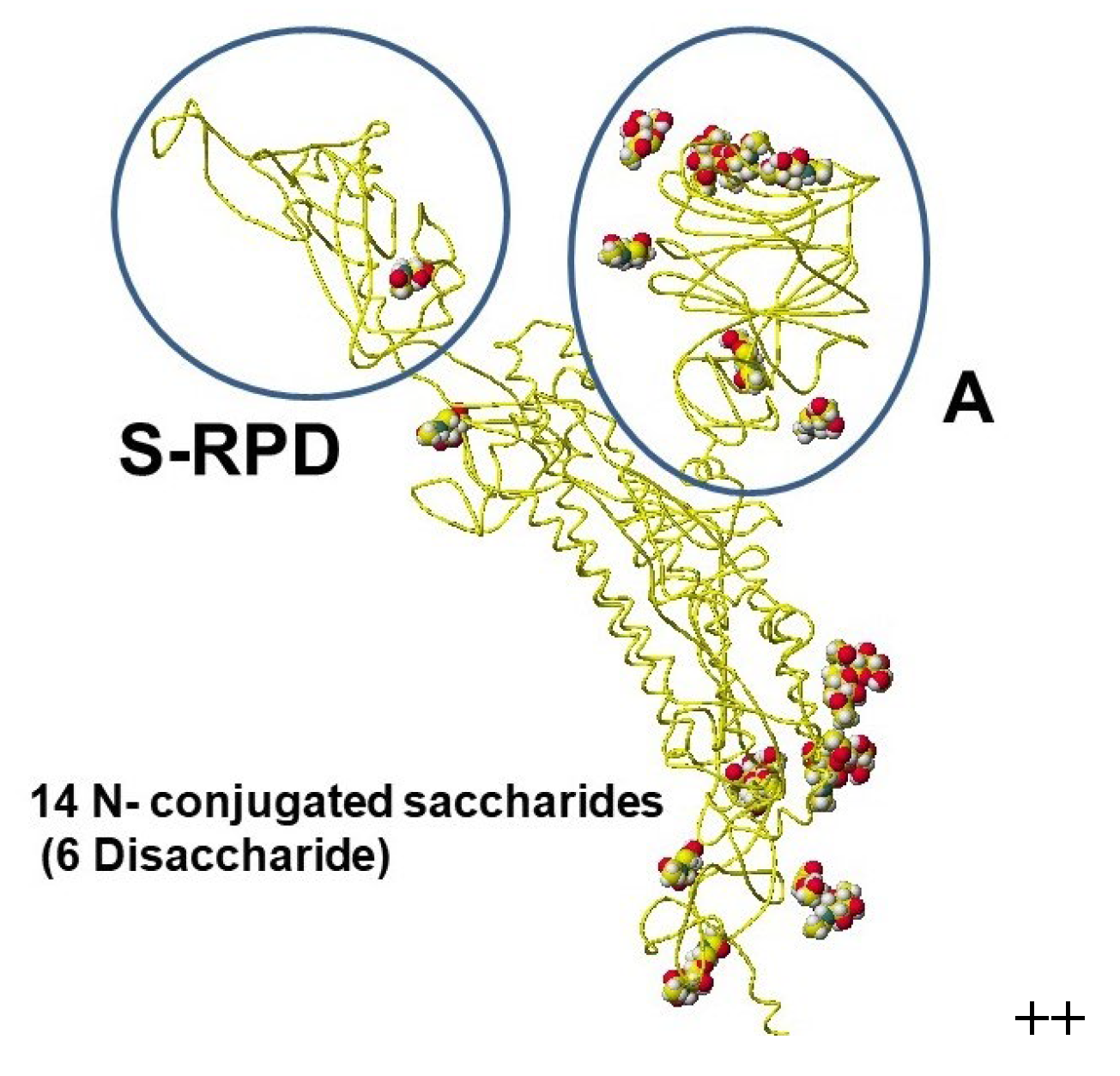

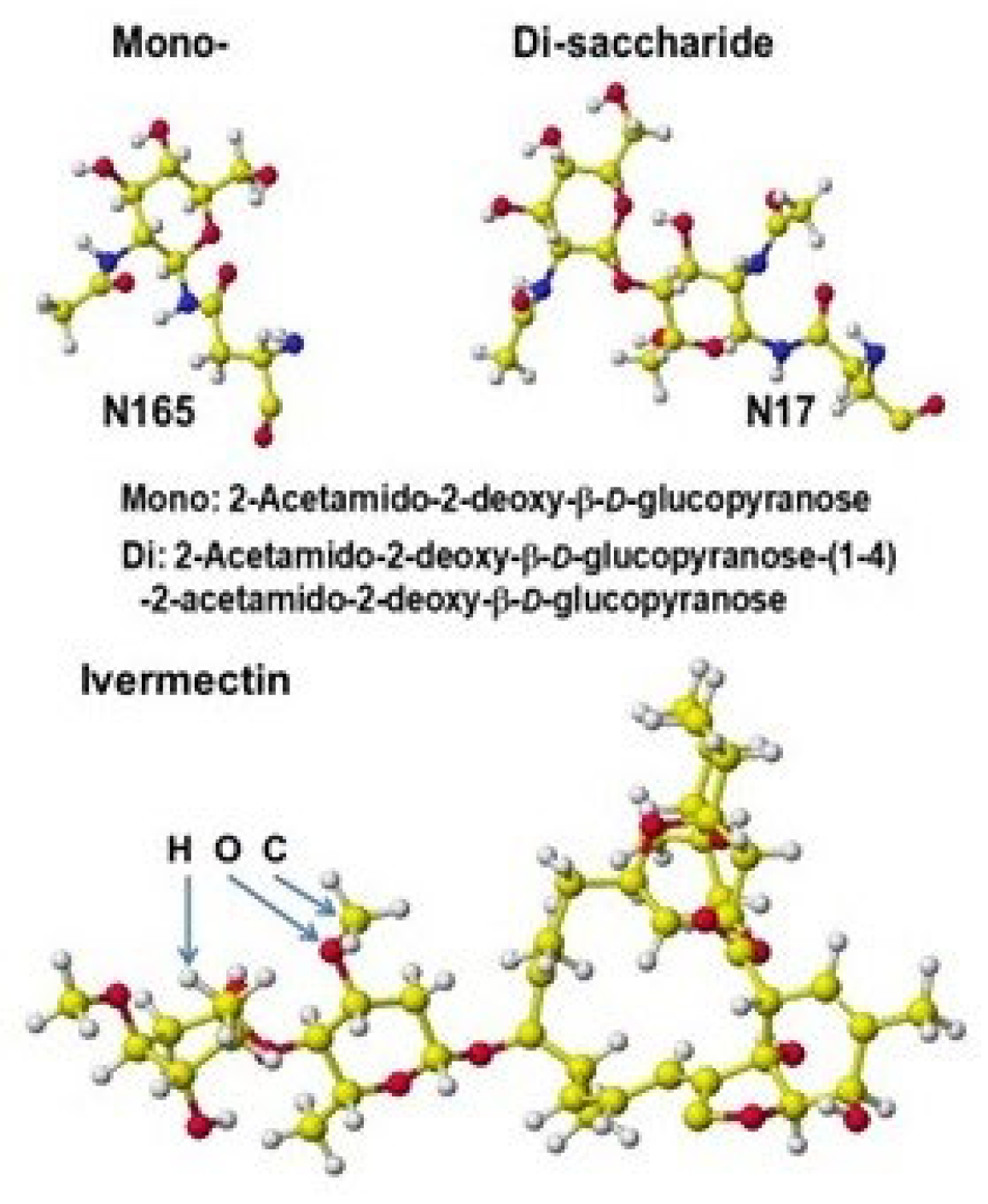

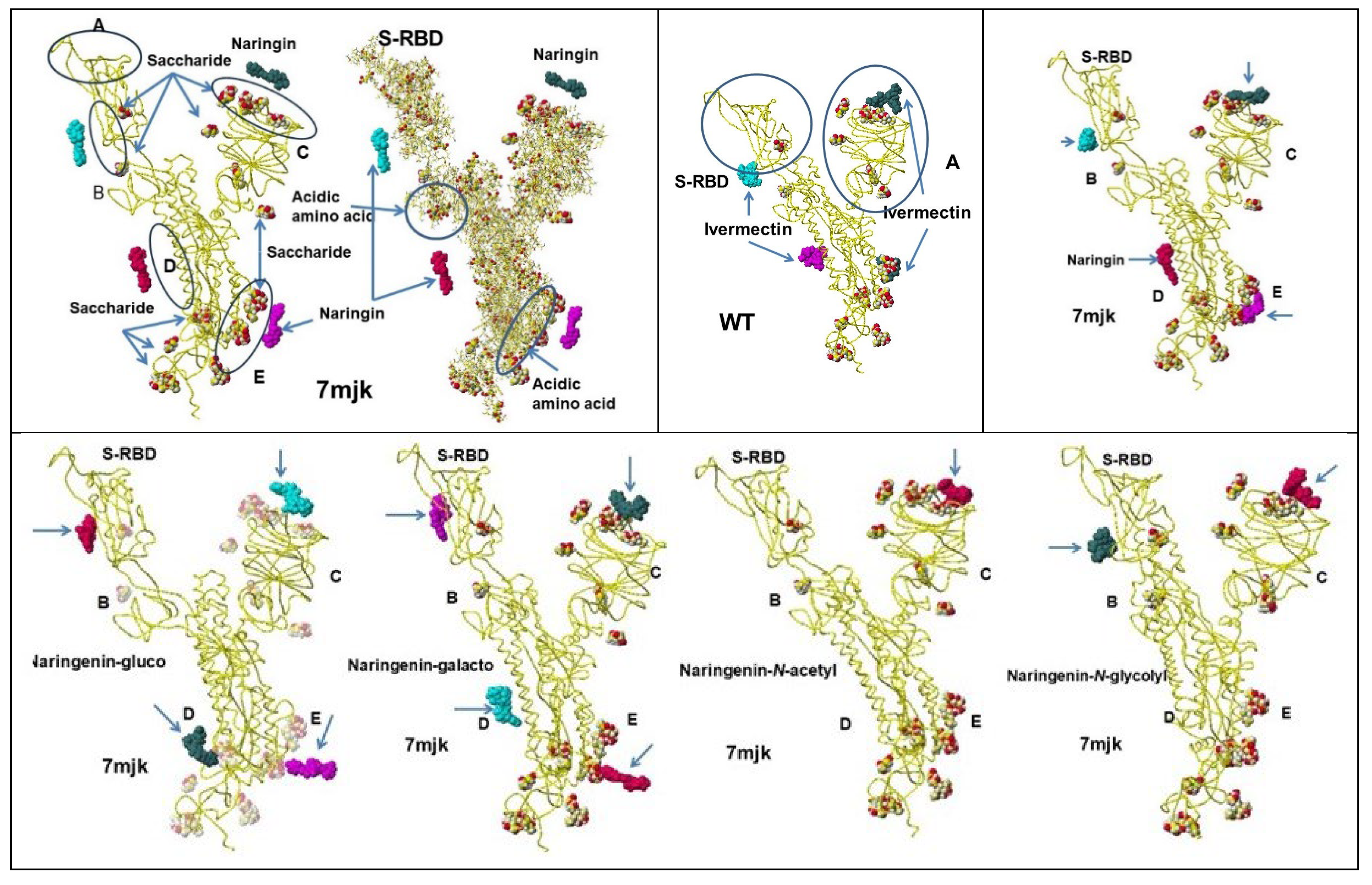

Saccharides and Ivermectin

5. Binding Inhibition of Natural Compounds

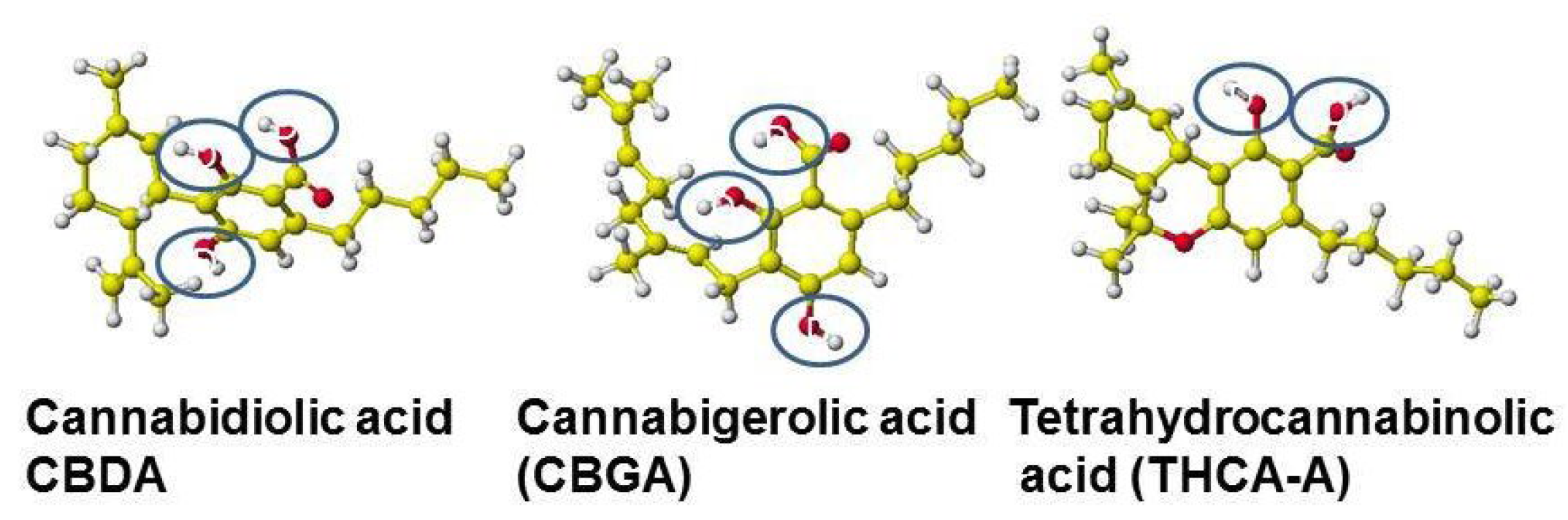

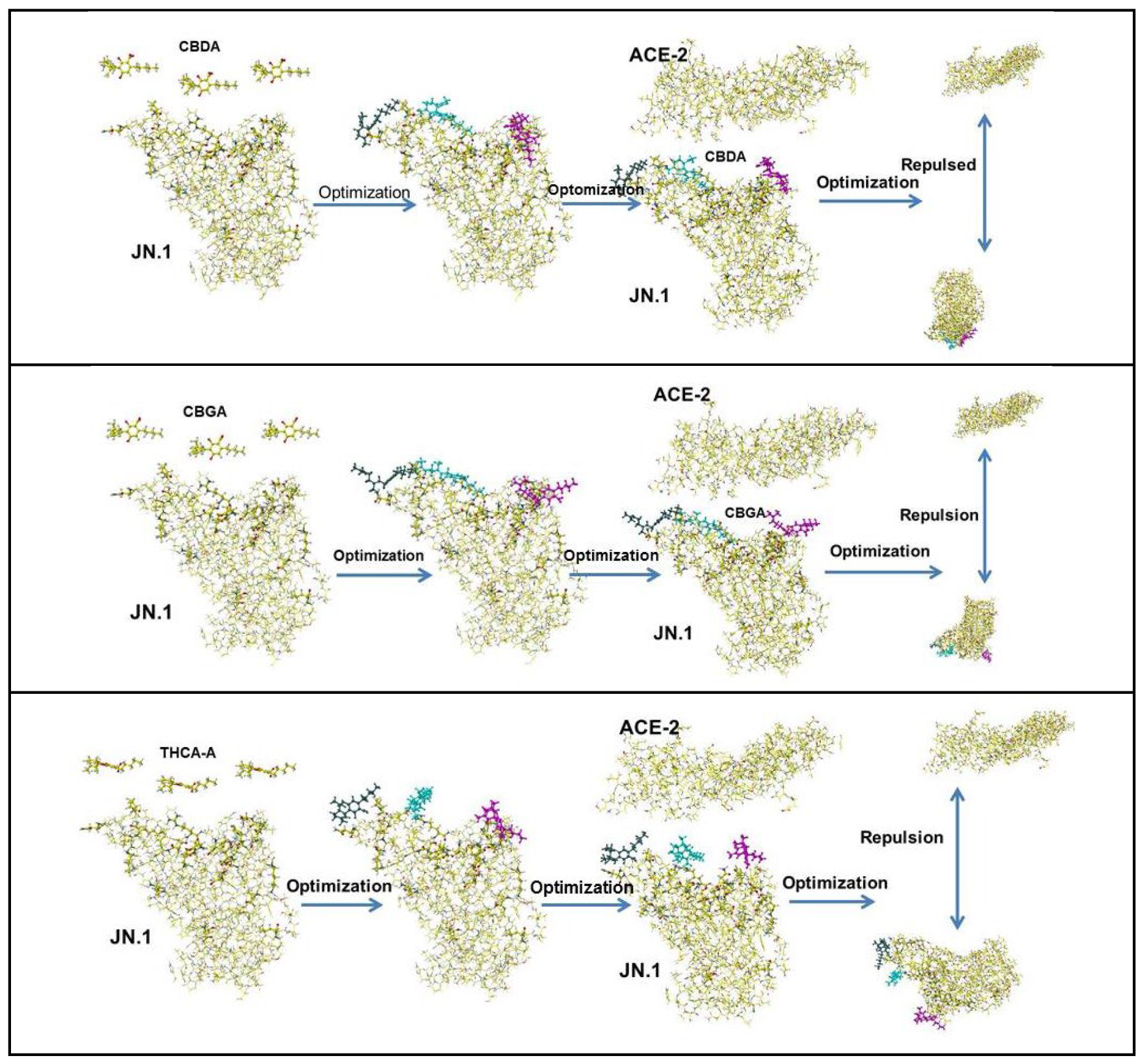

5.1. Cannabinoids

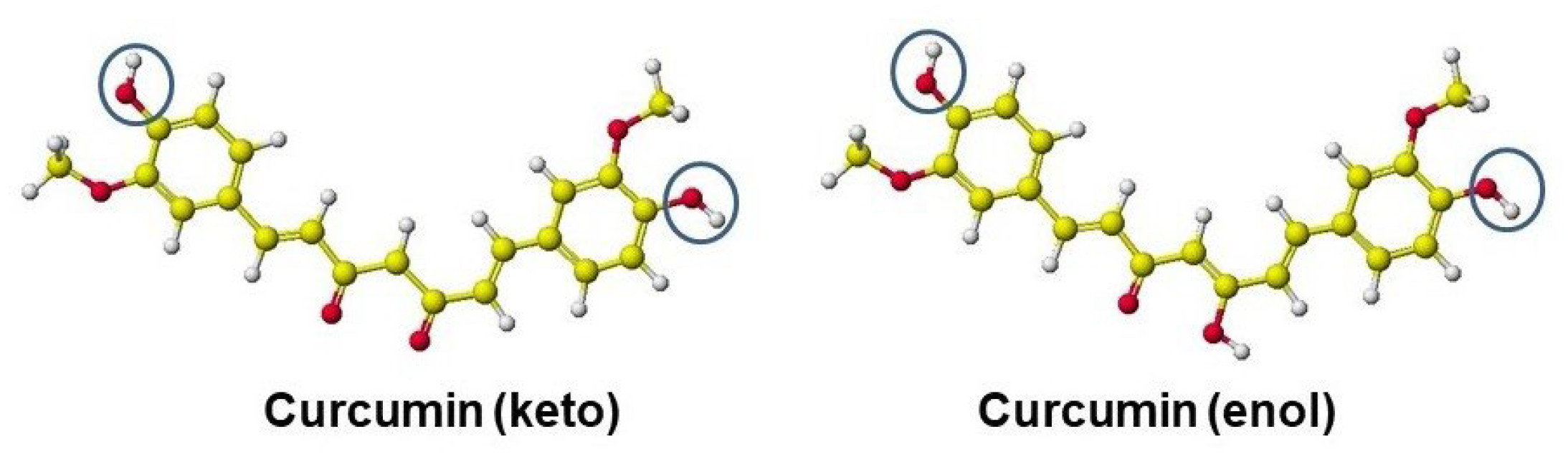

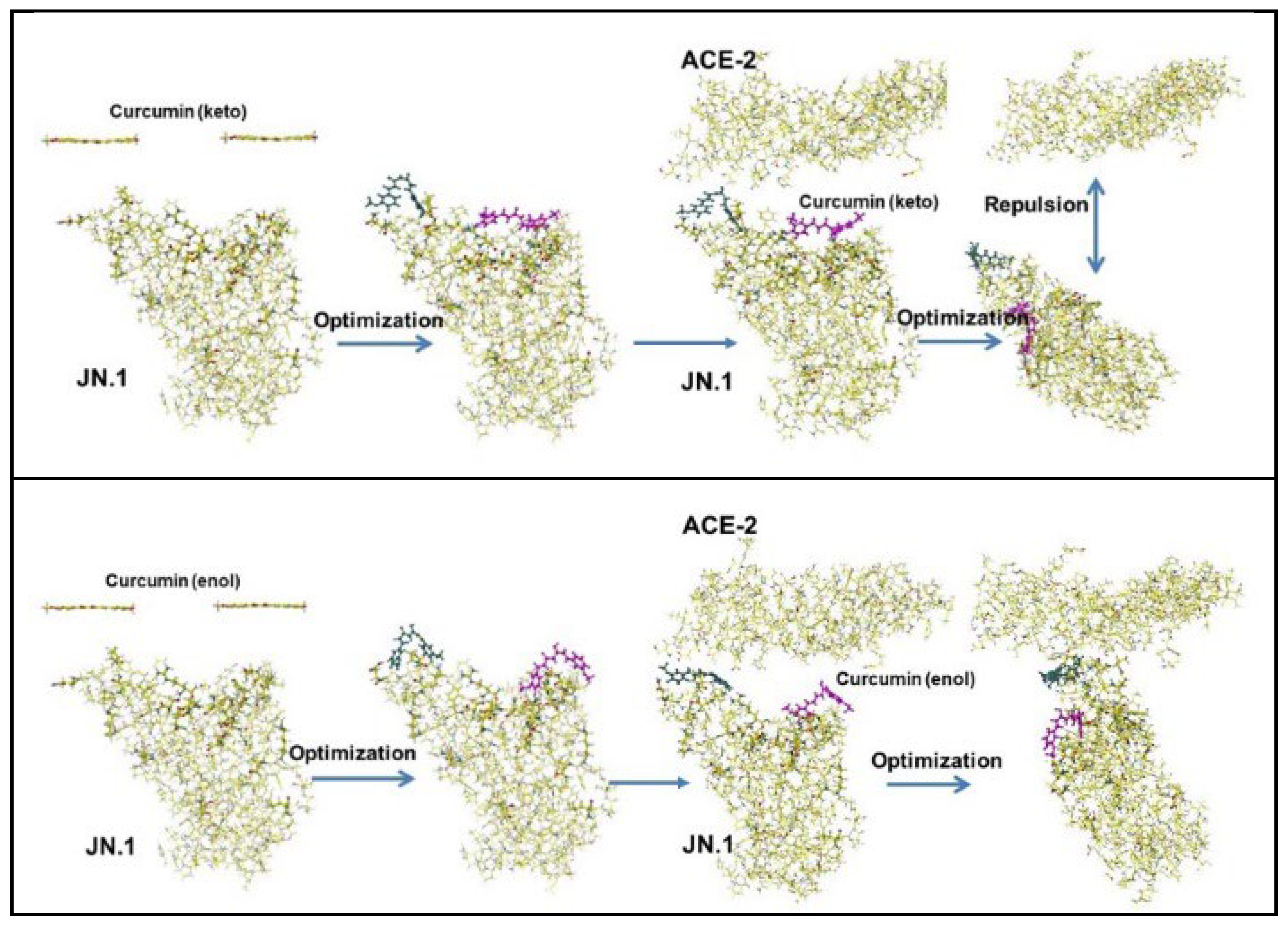

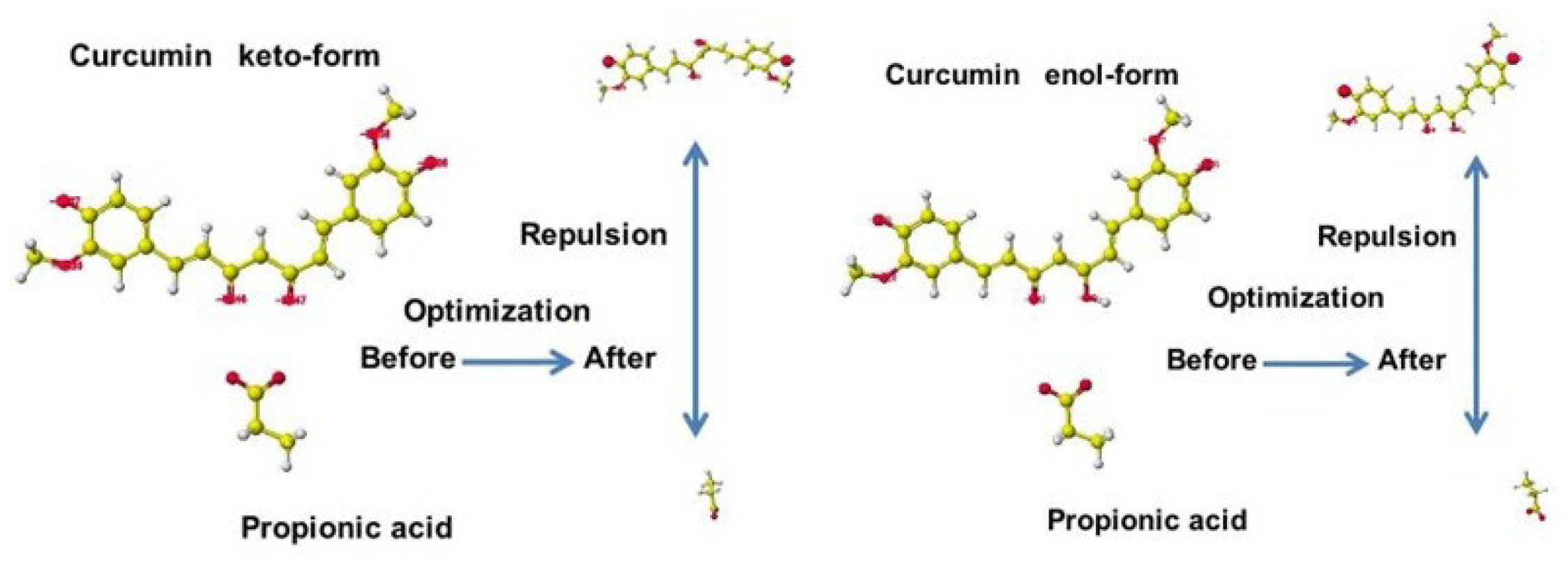

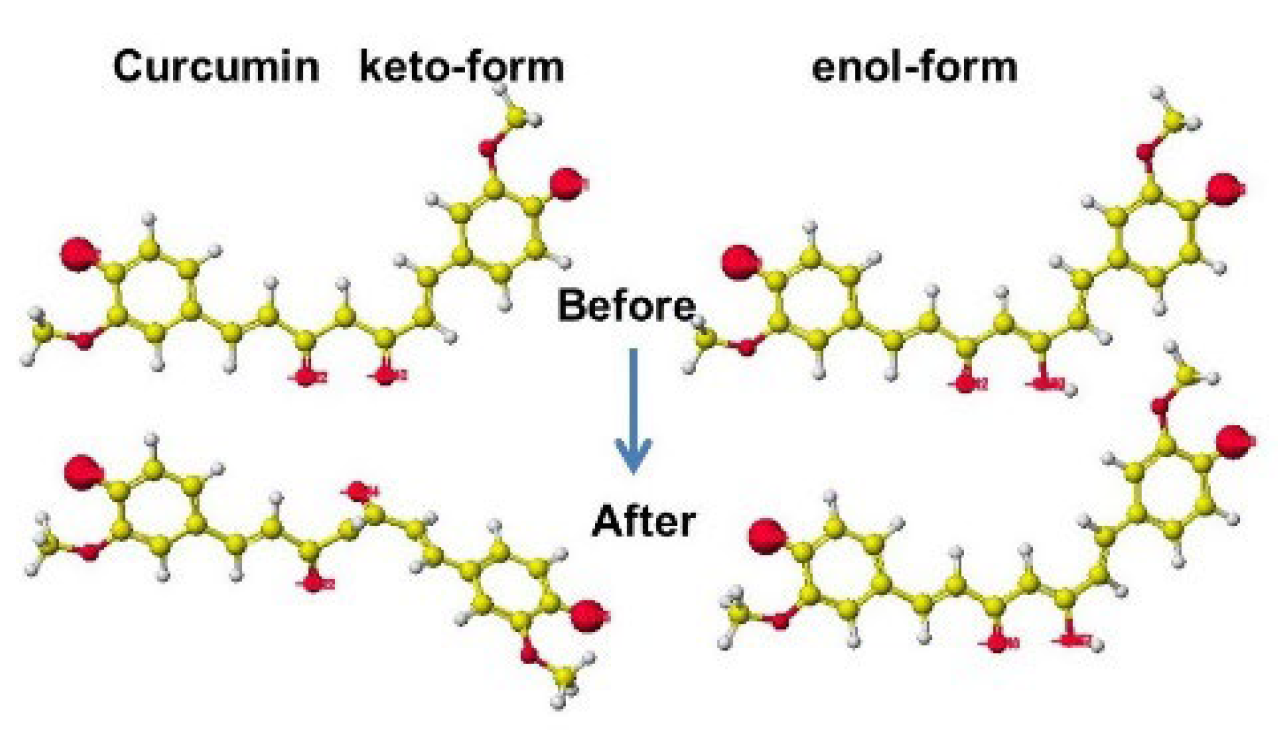

5.2. Curcumin

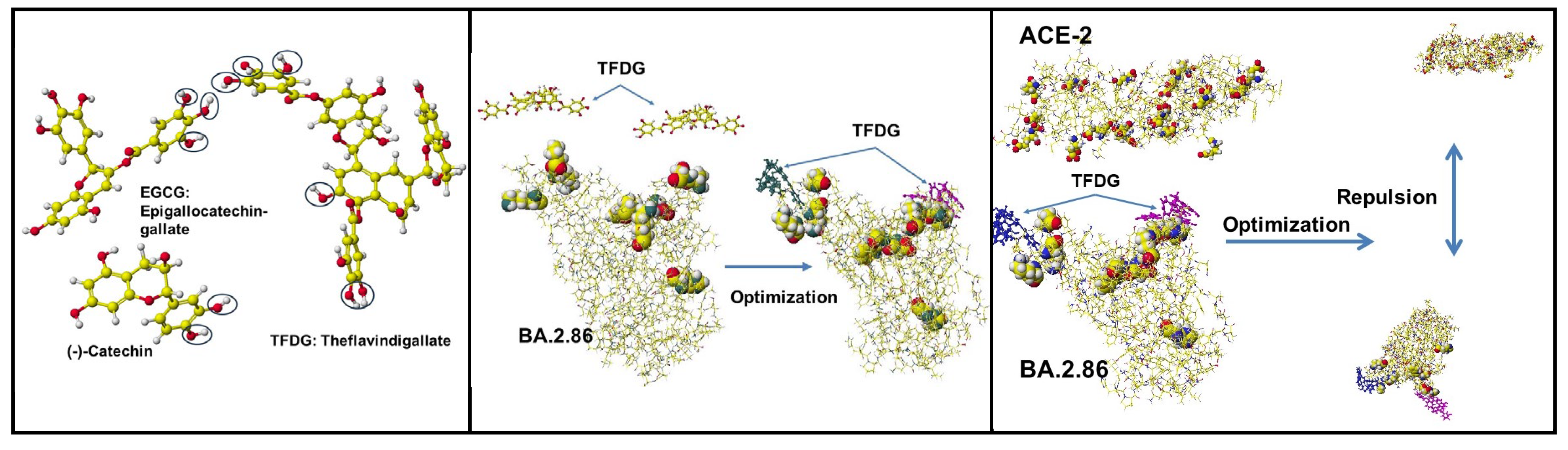

5.3. Polyphenols of Green and Black Rea

6. Glycisydation (Glycosylation) as an Effective Derivatization

7. Discussion

8. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

References

- Scudellari, M. How SARS-CoV-2 infects cells – and why Delta is so dangerous, Nature 2021, 595, 640-644. [CrossRef]

- Editorial, Cocid-19, a pandemic or not?, Lancet, 2020, 20, 383, www.thelancet.com/infection. [CrossRef]

- Horton, R. Offline: Covid-19 is not a pandemic, Lancet, 2020, 396, 874. Richard.horton@lancet.com.

- Shmerling, R.H. Is the Covid-19 pandemic over, or not?, Harvard Health Publishing, October 26, 2022.

- Topol, E. An optimistic outlook, Ground Truths, Daily pandemic update #6, November 7, 2022, erictioik@substack.com.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; SARS-CoV-2 variants of dashboard 10 Nov. 2022. http://www.ecdc.eu/en/covid-19/variant-concern.

- Prillaman, M. Prior omicron infection protects against BA.4 and BA.5 variants, Nature News 21 July 2022. [CrossRef]

- 8. Topol, E. The BA.5 story, The takeover by this omicron sub-variant is not pretty, Ground Truths, November 8, 2022.

- Tuekprakhon, A.; Nutalai, R.; Dijokaite-Guraliu, S.; Zhou, D.; Ginn, H.M.; Selvaraj, M.; Liu, C.; Mentzer, A.J.; Supasa, P.; Duyvesteyn, H.M.R.; Das, R.; Skelly, D.; Ritter, T.G.; Amini, A.; Bibi, S. Adele, S.; Johnson, S.A.; Constantinides, A.; Webster, H.; Temperton, N.; Klenerman, P.; Barnes, E.; Dunachie, S.J.; Crook, D.; Pollard, A.H.; Lambe, T.; Goulder, P.; Paterson, N.G.; Williams, M.A.; Hall. D.R.; Fry, E.E.; Huo, J.; Mongkolsapaya, J.; Ren, J.; Stuart, D.I.; Screaton, G.T.; Antibody escape of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.4 and BA.5 from vaccine and BA.1 serum, Cell, 2022, 185, 2422-2433.e13. [CrossRef]

- Sheward, D.J.; Kim, C.; Fischbach, J.; Muschiol, S.; Ehling, R.A.; Bjorkstrom, N.K.; Hedestam, S.T. Reddy, G.B.K.; Albert, J.; Peacock, T.P.; Murrell, B. Evasion of neutralizing antibodies by omicron sublineage BA.2.75, Lancet Infect Dis 2022, Sept 1 2022. [CrossRef]

- Topol. E. The BA2.86 variant and the new tooster, Ground Truths, Sept. 9, 2023. pp.12.

- Muik, A.; Lui, B.G.; Diao, H.; Fu, Y.; Bacher, M.; Toker, A.; Grosser, J.; Ozhelvaci, O.; Grikscheit, S. Hoehl, K.; Kohmer, N.; Lustig, Y.; Regev-Yochay, G.; Ciesek, S.; Beguir, K.; Poran, A.; Türeci, U. Sahin, Ö. Progressive loss of conserved spike protein neutralizing antibody sites in Omicron sublineages is balanced by preserved T-cell recognition epitopes, bioRxiv 2022, preprint: https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.12.15.520569, Cell Reports, 2023, 42, (8), 112888, Aug 29, 2023, pp.13. [CrossRef]

- Debnath, U.; Mitra, A.; Dewake, V.; Prabhakar, Y.S.; Tadala, R.; Krishnan, K.; Wagh, P.; Velusamy, C. Subramani, U.; Agarwal, S.; Vrati, S.; Baliyan, A.; Kurpad, A.V.; Bhattacharyya, P.; Mandal, A.K. N-acetyl cysteine: A tool to perturb SARS-CoV-2 spike protein conformation, http://chemorg/engage/api-gateway/chemrxiv/ssets/ Preprint from ChemRxiv, 06 Jan 2021, pp.21. [CrossRef]

- Stein, S.R.; Ramelli, S.C.; Grazioli, A.; Chung, J.-Y.; Singh, M.; Yinda, C.K.; Winkler, C.W.; Sun, J.; Dickey, J.M.; Ylaya, K.; Ko, S.H.; Platt, A.P.; Burbelo, P.D.; Quezado, M.; Pittaluga, S.; Purcell, M.; Munster, V.J.; Belinky, F.; Ramos-Benitez, M.J.; Boritz, E.A.; Lach, I.A.; Herr, D.L.; Rabin, J.; Saharia, K.K.; Madathil, R.J.; Tabatabai, A.; Soherwardi, S.; McCurdy, M.T.; Consortium, A.; Peterson, K.E.; Cohen, J.I.; de Wit, E.; Vannella, K. M.; Hewitt, S.M.; Kleiner, D.E.; Chertow, D.S. SARS-CoV-2 infection and persistence in the human body and brain at autopsy, Nature 2022, 612, 758-763.

- Lee, M.J.; Leong, M.W.; Rustagi, A.; Beck, A.; Zeng, L.; Holmes, S.; Qi, L.S.; Blish, C.A. SARS-CoV-2 escapes direct NK cell killing through Nsp1-mediated downregulation of ligands for NKG2D, Cell Reports 2022, 41, 111892, Dec. 27, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Bianchini, F.; Crivelli, V.; Abernathy, M.E.; Guerra, C.; Palus, M.; Muri, J.; Marcotte, H.; Piralla, A.; Pedotti, M.; De Gasparo, R.; Simonelli, L.; Matkovic, M.; Toscano, C.; Biggiogero, M.; Calvaruso, V.; Svoboda, P.; Rincón, T.C.; Fava, T.; Podešvová, L.; Shanbhag, AA.; Celoria, A.; Sgrignani, J.; Stefanik, M.; Hönig, V.; Pranclova, V.; Michalcikova, T.; Prochazka, J.; Guerrini, G.; Mehn, D.; Ciabattini, A.; Abolhassani, H.; Jarrossay, D.; Uguccioni, M.; Medaglini, D.; Pan-Hammarström, Q.; Calzolai, L.; Fernandez, D.; Baldanti, F.; Franzetti-Pellanda, A.; Garzoni, C.; Sedlacek, R.; Ruzek, D.; Varani, L.; Cavalli, A.; Barnes, C.O.; Robbiani, D.F. Human neutralizing antibodies to cold linear epitopes and subdomain 1 of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein, Sci. Immunol., 2023, 8,1-17.

- Tye, E.X.C.; Jinks, E.; Haigh, T.; Kaul, B.; Patek, P.; Parry, H.M.; Newby, M.K.; Crispin, M.; Kaur, N.; Moss, P.; Drennan, S.J.; Tayloe, G.S.; Long, H.M. Mutations in SARS-CoV-2 spike protein impair epitope-specific CD4+ T cell recognition. Nat. Immunol. 2022, 23, 1726–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fulop, T.; Larbi, A.; Pawelec, G.; Cohen, A.A.; Provost, G.; Khalil, A.; Lacombe, G.; Rodrigues, S.; Desroches, M.; Hirokawa, K.; et al. Immunosenescence and Altered Vaccine Efficiency in Older Subjects: A Myth Difficult to Change. Vaccines 2022, 10, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taishi Kayano, Misaki Sasanami, Hiroshi Nishiura, Science-based exit from stringent countermeasures against COVID-19: Mortality prediction using immune landscape between 2021 and 2022 in Japan, Vaccine: X 20 (2024) 100547, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Jose L. Domingo, A review of the scientifc literature on experimental toxicity studies of COVID-19 vaccines, with special attention to publications in toxicology journals, Archives of Toxicology (2024) 98:3603–3617. [CrossRef]

- Christopher D Richardson, Heterologous ChAdOx1-nCoV19–BNT162b2 vaccination provides superior immunogenicity against COVID-19, Lancet, Published Online August 12, 2021 https://doi.org/10.1016/ S2213-2600(21)00366-0, www.thelancet.com/respiratory Vol 9 November 2021, 1207-1209. [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, R.; Balzano, N.; Di Napoli, R.; Mascolo, A.; Berrino, P.M.; Rafaniello, C.; Sportiello, L.; Rossi, F.; Capuano, A. Capillary leak syndrome following COVID-19 vaccination: Front. Immunol. 2023, 13, 956825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, C.; Domke, L.M.; Hartmann, L.; Stenzinger, A.; Longerich, T.; Schirmacher, P. Autopsy-based histopathological characterization of myocarditis after anti-SARS-CoV-2-vaccination, Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2023, 112, 431–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonker, L.M.; Z. Swank, Z.; Bartsch, Y.C.; Burns, M.D.; Kane, A.; Boribong, B.P.; Davis, J.P.; Loiselle, M.; Novak, T.; Senussi, Y.; Cheng, C.-A.; Burgess, E.; Edlow, A.G.; Chou, J.; Dionne, A.; Balaguru, D.; Lahoud-Rahme, M.; Arditi, M.; Julg, B.; Randolph, A.G.; Alter, G.; Fasano, A.; Walt, D.R. Circulating Spike Protein Detected in Post–COVID-19 mRNA Vaccine Myocarditis, Circulation. 2023, 147, 867-876. [CrossRef]

- Barmada A.; Klein J.; Ramaswamy A.; Brodsky N.N.; Joycox J.R.; Sheikha H.; Nines K.M.; Habet V.; Campbell M.; Shimoda T.S.; Kontorovich A;. Bogunovic D.; Oliveira C.R.; Steele J.; Hall E.K.; Pena-Hernandez M.; Monteiro V.; Lucan C.; Ring A.M.; Omer S.B.; Iwasaki A.; Yildirim I.; Lucas C.L.; Cytokinopathy with aberrant cytotoxic lymphocytes and profibrotic myeloid response in SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine-associated myocarditis, Additional introduction doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.adh3455. Sci. Immunol. 2023, 8:1-18, eadh3455, Epub 2023, May 5. [CrossRef]

- Marco Alessandria 1,† , Giovanni M. Malatesta 2,†, Franco Berrino 3 and Alberto Donzelli, A Critical Analysis of All-Cause Deaths during COVID-19 Vaccination in an Italian Province, Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1343. [CrossRef]

- lberto Boretti, mRNA vaccine boosters and impaired immune system response in immune compromised individuals: a narrative review, Clinical and Experimental Medicine (2024) 24:23. [CrossRef]

- /Sunil J. WimalawansaUnlocking insights: Navigating COVID-19 challenges and Emulating future pandemic Resilience strategies with strengthening natural immunity, Heliyon 10 (2024) e34691. [CrossRef]

- Julie A. Bettinger, Michael A. Irvine, Hennady P. Shulha, Louis Valiquette, Matthew P. Muller, Otto G. Vanderkooi, James D. Kellner, Karina A. Top, Manish Sadarangani, Allison McGeer, Jennifer E. Isenor, Kimberly Marty, Phyumar Soe, and Gaston De Serres Adverse Events Following Immunization With mRNA and Viral Vector Vaccines in Individuals With Previous Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Infection From the Canadian National Vaccine Safety Network, Research Network CID 2023:76 (15 March) 1088-1102.

- Gibo M, Kojima S, Fujisawa A, Kikuchi T, Fukushima M, Increased Age-Adjusted Cancer Mortality After the Third mRNA-Lipid Nanoparticle Vaccine Dose During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Japan., Cureus. 2024 Apr; 16(4): e57860. Published online 2024 Apr 8. [CrossRef]

- /Ronald Palacios Castrillo, Cancer Mortality Surges Post COVID ModRNA Vaccination Ronald Palacios Castrillo, European Journal of Clinical and Biomedical Sciences 2024, Vol. 10, No. 2, pp. [CrossRef]

- /Valdes Angues R, Perea Bustos Y (December 17, 2023) SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination and the Multi-Hit Hypothesis of Oncogenesis. Cureus 15(12): e50703.

- /Yeon-Woo Heo;Jae Joon Jeon;Min Chul Ha, ;et al,You Hyun Kim,;Solam Lee, Long-Term Risk of Autoimmune and Autoinflammatory Connective Tissue Disorders Following COVID-19, JAMA Dermatol. Published online November 6, 2024. [CrossRef]

- /Muhammad Bilal Khalid, Pamela A. Frischmeyer-Guerrerio,, The conundrum of COVID-19 mRNA vaccine– induced anaphylaxi, J ALLERGY CLIN IMMUNOL GLOBAL FEBRUARY 2023.

- /4.Gwo-Tsann Chuang, Wei-Chou Lin, Luan-Yin Chang, I-Jung Tsai, Yong-Kwei Tsau, Pediatric glomerulopathy after COVID-19 vaccination: A case series and review of the literature, Journal of the Formosan Medical Association, Volume 122, Issue 11, November 2023, Pages 1125-1131. [CrossRef]

- /Chiao-Yu Yang, · Yu-Hsiang Shih, Chia-Chi Lung, The association between COVID-19 vaccine/infection and new-onset asthma in children - based on the global TriNetX database, Infection Open access, Published: 21 June 2024, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- /Jose L. Domingo, A review of the scientifc literature on experimental toxicity studies of COVID-19 vaccines, with special attention to publications in toxicology journals, Archives of Toxicology (2024) 98:3603–3617. [CrossRef]

- /Hiroshi Kusunoki, Michiko Ohkusa, Rie Iida, Ayumi Saito, Mikio Kawahara, Kazumi Ekawa, Nozomi Kato, Masaharu Motone, Hideo Shimizu, Increase in antibody titer and change over time associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection after mRNA vaccination: Consideration of the significance of additional vaccination, Clin Case Rep. 2024;12:e8953. [CrossRef]

- /Stephanie Seneff, Greg Nigh, Anthony M. Kyriakopoulos, Peter A. McCullough, Innate immune suppression by SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccinations: The role of G-quadruplexes, exosomes, and MicroRNAs, Food and Chemical Toxicology 164 (2022) 113008,1-19. [CrossRef]

- /Dominik Pflumm , Alina Seidel , Fabrice Klein, Rüdiger Groß, Lea Krutzke, Stefan Kochanek, Joris Kroschel , Jan Münch, Katja Stifter, Reinhold Schirmbeck, Heterologous DNA-prime/ protein-boost immunization with a monomeric SARS-CoV-2 spike antigen redundantizes the trimeric receptor-binding domain structure to induce neutralizing antibodies in old mice, Frontiers in Immunology, pp.15, TYPE Original Research PUBLISHED 11 September 2023. [CrossRef]

- /27.Elias A. Said, Afnan Al-Rubkhi, Sanjay Jaju, Crystal Y. Koh, Mohammed S. Al-Balushi, Khalid Al-Naamani , Siham Al-Sinani , Juma Z. Al-Busaidi and Ali A. Al-Jabri , Association of the Magnitude of Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine Side Effects with Sex, Allergy History, Chronic Diseases, Medication Intake, and SARS-CoV-2 Infection, Vaccines 2024,12, 104. [CrossRef]

- /5.Mina Thabet Kelleni, COVID-19 mortality paradox (United States vs Africa): Mass vaccination vs early treatment, World J Exp Med. 2024 Mar 20;14(1):88674. [CrossRef]

- /Alexander Muik,Bonny Gaby Lui,Jasmin Quandt,Huitian Diao, Yunguan Fu, Maren Bacher, Jessica Gordon, Aras Toker, Jessica Grosser, Orkun Ozhelvaci, Katharina Grikscheit, Sebastian Hoehl, Niko Kohmer, Yaniv Lustig, Gili Regev-Yochay, Sandra Ciesek, Karim Beguir, Asaf Poran, Isabel Vogler, O¨ zlem Tureci,, Progressive loss of conserved spike protein neutralizing antibody sites in Omicron sublineages is balanced by preserved T cell immunity, Cell Reports 42, 112888, August 29, 2023 ª 2023 BioNTech SE. [CrossRef]

- /Martin Heil*, Self-DNA driven inflammation in COVID-19 and after mRNAbased vaccination: lessons for non-COVID-19 pathologies, Immunol. 14:1259879. [CrossRef]

- Staufer, O.; Gupta, K.; Bucher, J.E.H.; Kohler, F.; Sigl, C.; Singh, G.; Vasileiou, K.; Relimpio, A.Y.; Macher, M.; Fabritz, S.; Dietz, H.; Adam, E.A.C.; Schaffitzel, C.; Ruggieri, A.; Platzman, I.; Berger, I.; Spatz, J.P. Synthetic virions reveal fatty acid-coupled adaptive immunogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. Nature Communications 2022, 13, 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Lewandowski, E.M.; Tan, H.; Zhang, X.; Morgan, R.T.; Zhang, X.; Jacobs, L.M.C.; Bitler, S.G.; Gongora, M.V. Choy, J.; Deng, X.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J. Naturally Occurring Mutations of SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease Confer Drug Resistance to Nirmatrelvir, ACS Cent. Sci. 2023, 9, 8, 1658–1669, Publication Date: July 24, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Doctrow, B. How COVID-19 variants evade the immune response, NIH Research Matter, June 8, 2021.

- Han, P.; Li, L.; Liu, S.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, D.; Xu, Z.; Hana, P.; Li, X.; Peng, Q.; Su, C.; Huang, B.; Li, D.; Zhang, R.; Tian, M.; Fu, L.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, X.; Liu, K.; Qi, J.; Gao, G.; Wang, P. Receptor binding and complex structures of human ACE2 to spike RBD from omicron and delta SARS-CoV-2, Cell, 2022, 185, 630-640. [CrossRef]

- Kozlov, M. Omicron overpowers key CONID antibody treatments in early tests, Nature, 2021, Dec 21, https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021-03829-0 (Sotrovimab, DXP-604). [CrossRef]

- Yamasoba, D.; Kosugi, Y.; Kimura, I.; Fujita, S.; Uriu, K.; Ito, J.; Sato, K. Neutralisation sensitivity of SARS-CoV-2 omicron subvariants to therapeutic monoclonal antibodies, Lancet, www.thelancet.com/infection, July 2022, 22, 942. [CrossRef]

- Hentzien, M.; Autran, B.; Pitoh, I.; Yazdanpanah, Y.; Calmy, A. A monoclonal antibody stands out against omicron subvariants: a call to action for wider access to Bebtelovimab, Lancet, www.thelancet.com/infection 22, Sept 2022. [CrossRef]

- Hanai, T. Quantitative in silico analysis of SARS-CoV-2 S-RBD omicron mutant transmissibility, Talanta, 2022, 240, 123206. [CrossRef]

- Anthony M Kyriakopoulos 1, Greg Nigh2, Peter A McCullough3, Stephanie Seneff, Clinical rationale for dietary lutein supplementation in long COVID and mRNA vaccine injury syndromes [version 3; peer, review: 2 approved], F1000Research 2024, 13:191 Last updated: 08 NOV 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad A Toubasi, Steven Allon and Francesca Bagnato, Disseminated histoplasmosis mimicking postvaccination side effects in an immunocompromised person with multiple sclerosis, Multiple Sclerosis Journal— Experimental, Translational and Clinical July–September 2024, 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Cheriyedath, S. Understanding immune responses to Sars-Cov-2 infections in children, News Med. Sci. Jan. 26, 2022, https://www.news-medical.net/news/202201125/Understanding-immune-responses-to-SARS-CoV-2-infections-inchildren.

- Mallapaty S. Kids Covid: Why young immune systems are still on top. Doi: 10.1038/d41586-02502423-8 Nature, 2021, 597, 166-168.

- Mallapaty S. Kids show mysteriously low levels of COVID-19 antibodies. Doi:10.1038/d41586-022-00681-8. Nature, News, 2022, Mar.10. [CrossRef]

- Briere, J.J.; Favier, J.; Gimenez-Roqueple, A.-P.; Rustin, P. Tricarboxylic acid cycle dysfunction as a cause of human diseases and tumor formation. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2006, 291, C1114–C1120. [Google Scholar]

- Smith K. (2021) Healthy eating, Nature News, Dcs. 10, 2021, (W. Willett et al. Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT-Lancet commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Doi: 10.1016/s170-6736(18)31788-4; Lancet, 2019, 383:447-492, Hirvonen CK et al. Affordability of the EAT-Lancet reference diet: a global analysis, http;//doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021. Lancet Glob. Health, 2020, 8: e59-e66.

- Michinobu Yoshimura, Atsuhiko Sakamoto, Ryo Ozuru, Yusuke Kurihara, Ryota Itoh, Kazunari Ishii, Akinori Shimizu , Bin Chou, Yusuke Sechi, Aya Fujikane, Shigeki Nabeshima, Kenji Hiromatsu, Insufficient anti-spike RBD IgA responses after triple vaccination with intramuscular mRNA BNT162b2 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2, Received 4 August 2023; Received in revised form 7 Heliyon 10 (2024) e23595, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Mohammad Hossein Fallah Mehrabadi, Monireh Hajimoradi, Ali Es-haghi, Saeed Kalantari, Mojtaba Noofeli, Ali Rezaei Mokarram, Seyed Hossein Razzaz, Maryam Taghdiri, Ladan Mokhberalsafa, Fariba Sadeghi, Vahideh Mohseni, Safdar Masoumi, Rezvan Golmoradi-Zadeh, Mohammad Hasan Rabiee, Masoud Solaymani-Dodaran, Seyed Reza Banihashemi, Safety and Immunogenicity of Intranasal Razi Cov Pars as a COVID-19 Booster Vaccine in Adults: Promising Results from a Groundbreaking Clinical Trial, Vaccines 2024, 12, 1255. [CrossRef]

- Ming Gao, Xiaomin Xing, Wenbiao Hao, Xulei Zhang, Kexin Zhong, Canhui Lu, Xilong Deng, Lei Yu, Diverse immune responses in vaccinated individuals with and without symptoms after omicron exposure during the recent outbreak in Guangzhou, China, Heliyon 10 (2024) e24030. [CrossRef]

- Khaleqsefat Esmat, Baban Jamil, Ramiar Kaml Kheder, Arnaud John Kombe Kombe, Weihong Zeng, Huan Ma, Tengchuan Jin, Immunoglobulin A response to SARS-CoV-2 infection and immunity, REVIEW ARTICLE HELYON, Volume 10, Issue 1e24031January 15, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Oscar Bladh, Katherina Aguilera, Ulrika Marking, Martha Kihlgren, Nina Greilert Norin, Anna Smed-Sörensen, Margaret Sällberg Chen, Jonas Klingström, Kim Blom, Michael W. Russell, Sebastian Havervall , Charlotte Thålin, Mikael Åberg, Comparison of SARS-CoV-2 spike-specific IgA and IgG in nasal secretions, saliva and serum, Frontiers in Immunology, PUBLISHED 15 March 2024. [CrossRef]

- Villadiego, J.; García-Arriaza, J.; Ramírez-Lorca, R.; García-Swinburn, R.; Cabello-Rivera, D.; Rosales-Nieves, A.E.; Álvarez-Vergara, M.I.; Cala-Fernández, F.; García-Roldán, E.; López-Ogáyarl, J.L.; Zamora, C.; Astorgano, D.; Albericio, G.; Pérez, P.; Muñoz-Cabello, A.M.; Pascual, A.; Esteban, M.; López-Barneo, J.; Toledo-Ara, J.J. Full protection from SARS-CoV-2 brain infection and damage in susceptible transgenic mice conferred by MVA-CoV2-S vaccine candidate, Nature Neuroscience, 2022, 26, 226-238. [CrossRef]

- Offit, P.A. Bivalent Covid-19 Vaccines — A Cautionary Tale, N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 481–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irrgang, P.; Gerling, J.; Kocher, K.; Lapuente, D.; Steininger, P.; Habenicht, K.; Wytopi, M.; Beileke, S.; Schäfer, S.; Zhong, J.; Ssebyatika, G.; Krey, T.; Falcone, V.; Schülein, C.; Peter, A.S.; Nganou-Makamdop, K.; Hengel, H.; Held, J.; Bogdan, C.; Überla, K.; Schober, K.; Winkler, T.H.; Tenbusch, M. Class switch towards non-inflammatory, spike-specific IgG4 antibodies after repeated SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination. Sci. Immunol. 2023, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saed Abbasi,1,7 Miki Matsui-Masai,2,7 Fumihiko Yasui,3 Akimasa Hayashi,4 Theofilus A. Tockary,1 Yuki Mochida,1,5 Shiro Akinaga,2 Michinori Kohara,6 Kazunori Kataoka,1 and Satoshi Uchida1,, Carrier-free mRNA vaccine induces robust immunity against SARS-CoV-2 in mice and non-human primates without systemic reactogenicity, Molecular Therapy Vol. 32 No 5 May 2024 1267,p.1266-1283. [CrossRef]

- Michael W. Grunst, Zhuan Qin, Esteban Dodero-Rojas, Shilei Ding, Jérémie Prévost, Yaozong Chen, Yanping Hu, Michael W. Grunst, Zhuan Qin, Esteban Dodero-Rojas, Shilei Ding, Jérémie Prévost, Yaozong Chen, Yanping Hu, Marzena Pazgier, Shenping Wu, Xuping Xie, Andrés Finzi, José N. Onuchic, Paul C. Whitford, Walther Mothes, Wenwei Li, Structure and inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 spike refolding in membranes, SCIENCE, ug 2024 Vol 385, Issue 6710 pp. 757-765. [CrossRef]

- Jon Cohen, Missing immune cells may explain why COVID-19 vaccine protection quickly wanes, New insights on what stimulates long-lived antibody production could spur better vaccines, SCIENCE INSIDER, 11 OCT 2024, PP.

- Hentzien, M.; Autran, B.; Pitoh, I.; Yazdanpanah, Y.; Calmy, A. A monoclonal antibody stands out against omicron subvariants: a call to action for wider access to Bebtelovimab, Lancet, www.thelancet.com/infection 22, Sept 2022.

- Barmada A.; Klein J.; Ramaswamy A.; Brodsky N.N.; Joycox J.R.; Sheikha H.; Nines K.M.; Habet V.; Campbell M.; Shimoda T.S.; Kontorovich A; Bogunovic D.; Oliveira C.R.; Steele J.; Hall E.K.; Pena-Hernandez M.; Monteiro V.; Lucan C.; Ring A.M.; Omer S.B.; Iwasaki A.; Yildirim I.; Lucas C.L.; Cytokinopathy with aberrant cytotoxic lymphocytes and profibrotic myeloid response in SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine-associated myocarditis, Additional introduction doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.adh3455. Sci. Immunol. 2023, 8:1-18, eadh3455, Epub 2023, May 5. [CrossRef]

- Hanai, T. Further quantitative in silico analysis of SARS-CoV-2 S-RBD Omicron BA.4, BA.5, BA.2.75, BQ.1, and BQ.1.1 transmissibility, Talanta, 2023, 254, 124127. [CrossRef]

- RCSB PDB 7mjk.

- D. Zha, M. Fu, Y, Qian, Vascular Endothelial Glycocalyx Damage and Potential Targeted Therapy in COVID-19, Cells `2022, 11, 1972. [CrossRef]

- Kissel, G.T.; René, E.; Toes, M.; Thomas, W.; Huizinga1, J.; Manfred, W. Glycobiology of rheumatic, diseases, Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2023 Jan;19(1):28-43. [CrossRef]

- Williamson, G. Effects of polyphenols on glucose-induced metabolic changes in healthy human subjects and on glucose transporters, Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2022, 66, 2101113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanai, T. (Ed) Quantitative in Silico Analytical Chemistry, Quantitative analysis of molecular interactions from chromatography retention to enzyme selectivity, http://www.hanai-toshihiko.net/ or http://hanai-tohihiko.net/, 2024, pp.327, 43.5MB (10 Chapters).

- Van Breemen, R.B.; Muchiri, R.N.; Bates, T.A.; Weinstein, J.B.; Leier, H.C.; Farly, S.; Tafesse, F.G. Cannabinoids block cellular entry of SARS-CoV-2 and the emerging variants, J. Nat. Prod. 2022, 85, 496–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brevini, T.; Maes, M.; Webb, G.J.; John, B.V.; Fuchs, C.D.; Buescher, G.; Wang, L.; Griffiths, C.; Brown, M.L.; Scott III, W.E.; Pereyra-Gerber, P.; Gelson, W.T.H.; Brown, S.; Dillon, S.; Muraro, D.; Sharp, J.; Neary, M.; Box, H.; Tatham, L.; Stewart, J.; Curley, P.; Pertinez, H.; Forrest, S.; Mlcochova, P. FXR inhibition may protect from SARS-CoV-2 infection by reducing ACE2, Nature, 2023,615, 134–142. [CrossRef]

- Hammond, J.; Leister-Tebbe, H.; Gardner, A.; Abreu, P.; Bao, W.; Wisemandle, W.; Baniecki, M.- L.; Hendrick, V.M.; Damle, B.; Simón-Campos, A.; Pypstra, R.; Rusnak, J.M. Oral Nirmatrelvir for High-Risk, Nonhospitalized Adults with Covid-19, N Engl J Med. 2022, 386, 1397-408. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, J.A.; Barbosa, B.V.R.; Lima, M.T.N.S.; Cardoso, P.G.; Consigli, C.; Pimenta, L.P.S. Antiviral fungal metabolites and some insights into their contribution to the current COVID-19 pandemic, Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2021, 46, 116366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Xiao, Y.; Lidsky, P.V.; Wu, C.-T.; Bonser, L.R.; Peng, S.; Garcia-Knight, M.A.; Tassetto, M.; Chung, C.-I.; Li, X.; Nakayama, T.; Lee, I.T.; Nayak, J.V.; Ghias, K.; Hargett, K.L.; Shoichet, B.K.; Erle, D.J.; Jackson, P.K.; Andino, R.; Shu, X. Fluorogenic reporter enables identification of compounds that inhibit SARS-CoV-2, Nature Microbiology, 2023, 8, 121–134. [CrossRef]

- Cordero, F.M.M. Research study to evaluate the clinical effectiveness of the nutritional supplement VITAMIC BIOSEN®, Combination of Curcumin, Vitamin C, and Boswellia Serrata, on individuals with symptoms consistent with LONG COVID who have been vaccinated against the SARS-CoV2, Biomed J Sci & Tech Res.2022, 47, BJSTR.MS.ID.007512, 38567-38581.

- Bodie, N.M.; Hashimoto, R.; Connolly, D.; Chu, J.; Takayama, K.; Uhal, B.D. Design of a chimeric ACE-2/Tc-silent fusion protein with ultrahigh affinity and neutralizing capacity for SARS-CoV-2 variants, Antib. Ther. 2023, 20, 59-74, https://academic.oup.com/abt/advance-article/doi/10.1093/abt/tbad001/6994056 by guest on Jan. 25, 2023.

- Zhang, J.-L.; Li, Y.-H.; Wang, L.-L.; Liu, H.-Q.; Lu, S.-Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, K.; Li, B.; Li, S.-Y.; Shao, F.-M.; Wang, K.; Sheng, N.; Li, R.; Cui, J.-J.; Sun, P.-C.; Ma, C.-X.; Zhu, B.; Wang, Z.; Wan, Y.-H.; Yu, S.-S.; Che, Y.; Wang, C.-Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, L.-M.; Peng, X.-Z.; Cheng, Z.; Chang, Jun-B.; Jiang, J.-D. Azvudine is a thymus-homing anti-SARS-CoV-2 drug effective in treating COVID-19 patients, Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 2021, 6, 414. [CrossRef]

- Yue, C.; Song, W.; Wang, L.; Jian, F.; Chen, X.; Gao, F.; Shen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Cao, Y. ACE2 binding and antibody evasion in enhanced transmissibility of XBB.1.5, The Lancet Infectious Diseases, Lancet Infect Dis. 2023 Mar, 23(3):278-280. [CrossRef]

- Topol, E. The virus takes a detour in its evolution arc, Ground Truths, OCT. 26, 2023, https:/erictopod.substack.com/p/the-virus-takes-a-detour-in-its-evolution-arc/.

- 89. Kaku, Y.; Okumura, K.; Padilla-Blanco, M.; Kosugi, Y.; Uriu, K.; Hinay Jr, A.A.; Chen, L.; Plianchaisuk, A.; Kobiyama, K.; Ishii, K.J.; Zahradnik, J.; Ito, J.; Sato, K. Virological characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 JN.1 variant Lancet Infect Dis. 2024, Jan.3. 2024.

- Bjorkman, A.; Gisslen, M.; Gullberg, M.; Ludvigsson, J. The Swedish COVID-19 approach: a scientific dialogue on mitigation policies, Frontiers in Public Health, 2023, 20, 1-4. [CrossRef]

- Villadiego, J.; García-Arriaza, J.; Ramírez-Lorca, R.; García-Swinburn, R.; Cabello-Rivera, D.; Rosales-Nieves, A.E.; Álvarez-Vergara, M.I.; Cala-Fernández, F.; García-Roldán, E.; López-Ogáyarl, J.L.; Zamora, C.; Astorgano, D. Albericio, G.; Pérez, P.; Muñoz-Cabello, A.M.; Pascual, A.; Esteban, M.; López-Barneo, J.; Toledo-Ara, J.J. Full protection from SARS-CoV-2 brain infection and damage in susceptible transgenic mice conferred by MVA-CoV2-S vaccine candidate. Nature Neuroscience, 2022; 26, 226–238. [Google Scholar]

- Van Breemen, R.B.; Muchiri, R.N.; Bates, R.A.; Weistein, J.B.; Leier, H.C.; Farly, S.; Tafesse, F.G. Cannabinoids block cellular entry of SARS-CoV-2 and the emerging variants. J. Nat. Rod. 2022, 85, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanai, T. (Ed) Quantitative in silico Chromatography, Computational Modeling of Molecular Interactions, 2014, RSC, Cambridge, pp.338. ISBN 978-1-84973-991-7.

- Tozser, J.; Benko, S. Natural compounds as regulators of NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated IK-1b production, Mediator of Inflammation, 2016, Article ID: 5460302, pp.16.

- T.E. Tallei, Fatimawali, N.J. Niode, R. Idroes, R.M. Zidan, S. Mitra, I. Celik, F. Nainu, D. Ağagündüz, T.B. Emran, and R. Capasso, A Comprehensive Review of the Potential Use of Green Tea Polyphenols in the Management of COVID-19, Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2021, 7170736. Published online 2021 Dec 3. [CrossRef]

- R. Ghosh, A. Chakraborty, A. Biswas, and S. Chowdhuri, Evaluation of green tea polyphenols, as novel coronavirus (SARS CoV-2) main protease (Mpro) inhibitors – an in silico docking and molecular dynamics simulation study, J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2020, 1–13. Published online 2020 Jun 22. [CrossRef]

- L. Henss, A. Auste, C. Schürmann, C. Schmidt, C. von Rhein, M.D. Mühlebach, B.S Schnierle, The green tea catechin epigallocatechin gallate inhibits SARS-CoV-2 infection, J Gen Virol. 102(4) (2021), 001574. [CrossRef]

- J. Park, R. Park, M. Jang, and Y-I. Park, Therapeutic Potential of EGCG, a Green Tea Polyphenol, for Treatment of Coronavirus Diseases, Life (Basel). 197, (2021) 197. Published online 2021 Mar 4. [CrossRef]

- H. Nishimura, M. Okamoto, I. Dapat, M. Katsumi, H. Oshitani, Inactivation of SARS-CoV-2 by Catechins from Green Tea, Jpn J Infect Dis. 74(5), (2021) 421-423. [CrossRef]

- T. Hanai (ed) Quantitative in silico chromatography, Computational modeling of molecular interactions, 2014, RSC, Cambridge, p.94-100. (T. Hanai, Quantitative structure-retention relationship of phenolic compounds without Hammet’s equations, J. Chromatogr. A, 985 (2003) 343-349.

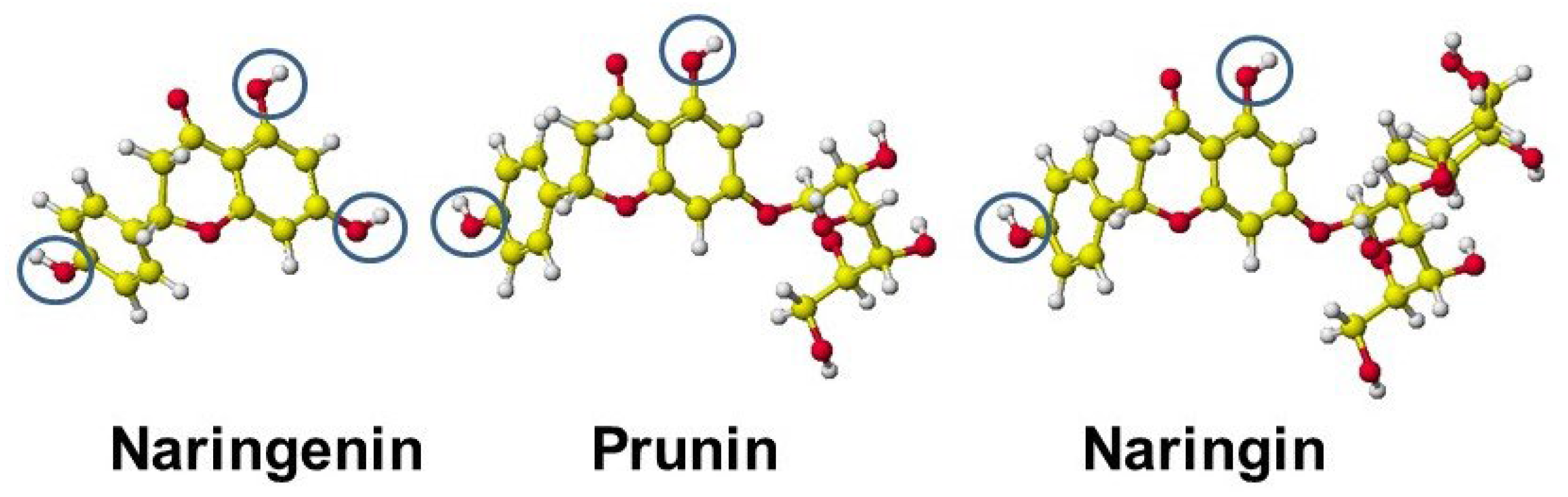

- Ricardo Wesley Alberca1, Franciane Mouradian Emidio Teixeira, Danielle Rosa Beserra, Emily Araujo de Oliveira, Milena Mary de Souza Andrade, Anna Julia Pietrobon, Maria Notomi Sato, The Potential Effects of Naringenin in COVID-19, Front. Immunol., 25 September 2020, Sec. Nutritional Immunology, Volume 11 - 2020. [CrossRef]

- Siqi Liu, Mengli Zhong, Hao Wu, Weiwei Su, Yonggang Wang, Peibo Li, Potential Beneficial Effects of Naringin and Naringenin on Long COVID—A Review of the Literature, Microorganisms 2024, 12, 332. [CrossRef]

- Helda Tutunchi, Fatemeh Naeini, Alireza Ostadrahimi, Mohammad Javad Hosseinzadeh-Attar Naringenin, a flavanone with antiviral and anti-inflammatory effects: A promising treatment strategy against COVID-19, Phytotherapy Research. 2020;34:3137–3147. [CrossRef]

- Nicola Clementi, Carolina Scagnolari, Antonella D’Amore, Fioretta Palombi, Elena Criscuolo, Federica Frasca, Alessandra Pierangeli, Nicasio Mancini, Guido Antonelli, Massimo Clementi, Armando Carpaneto, Antonio Filippini, Naringenin is a powerful inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro, Pharmacological Research 163 (2021) 105255. [CrossRef]

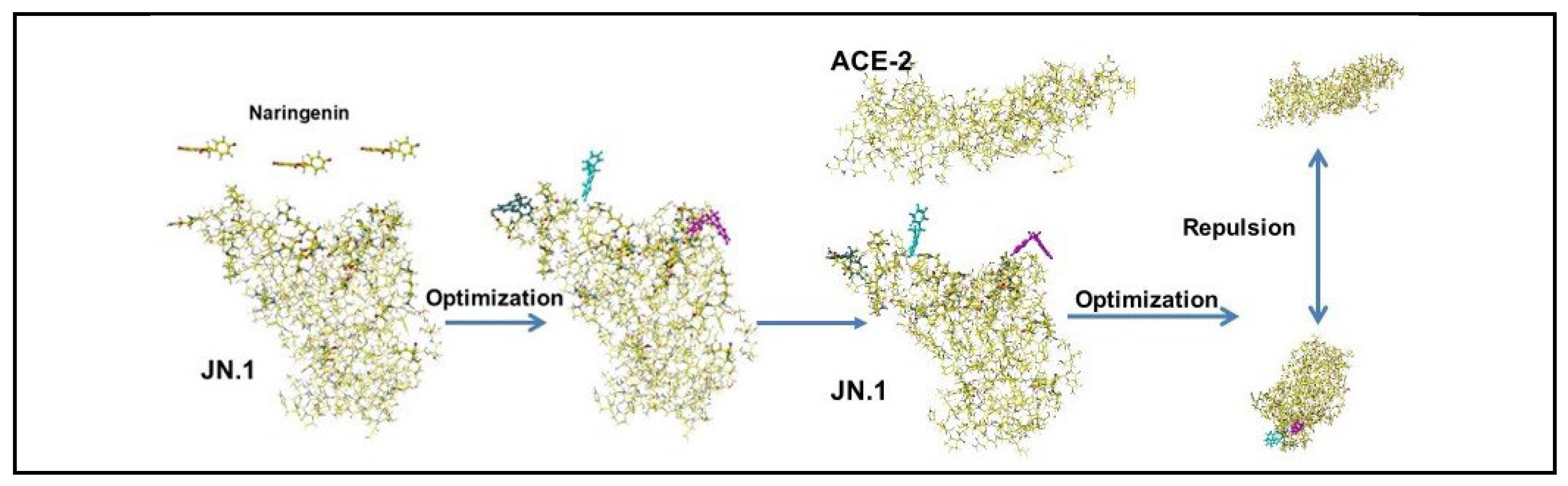

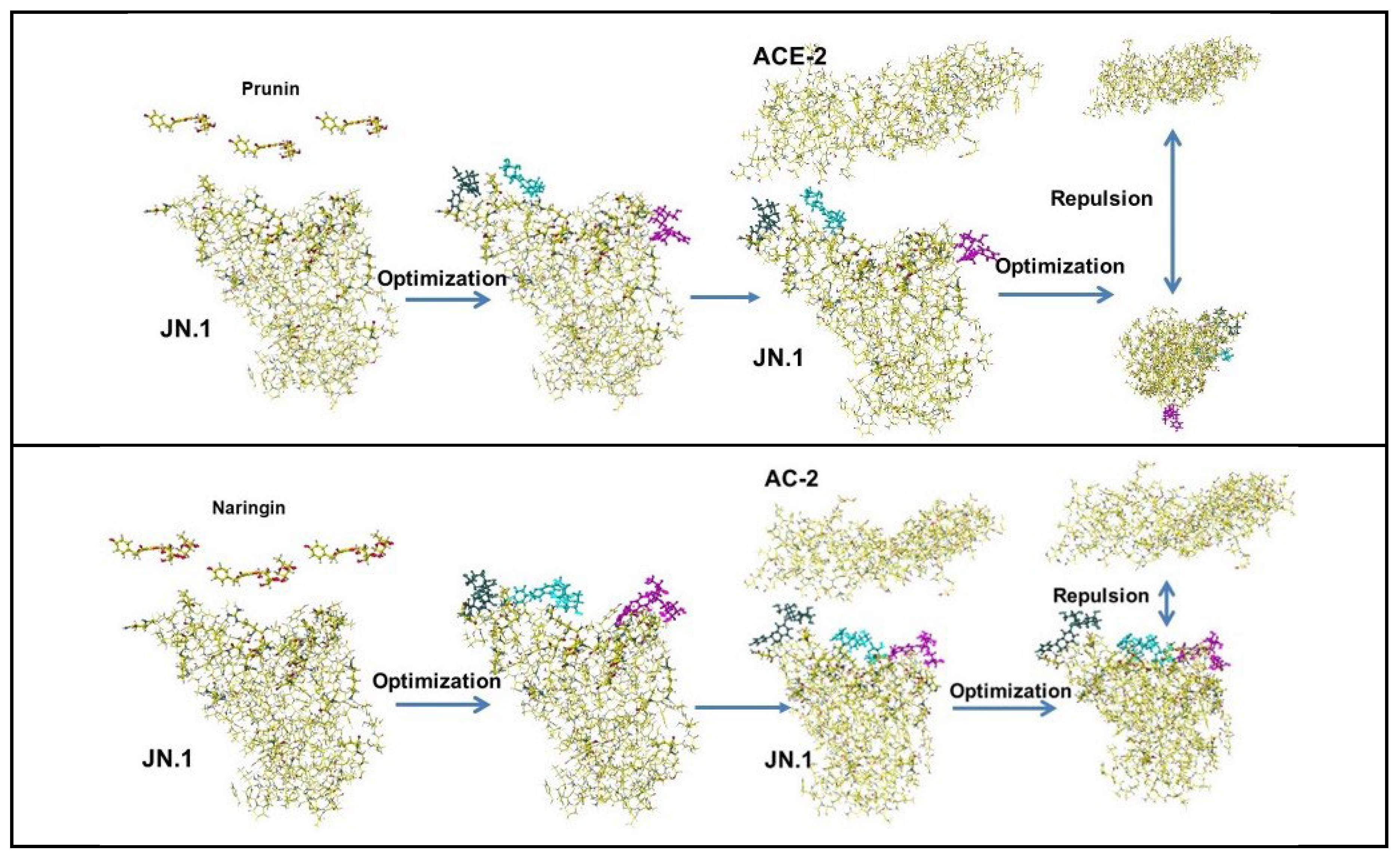

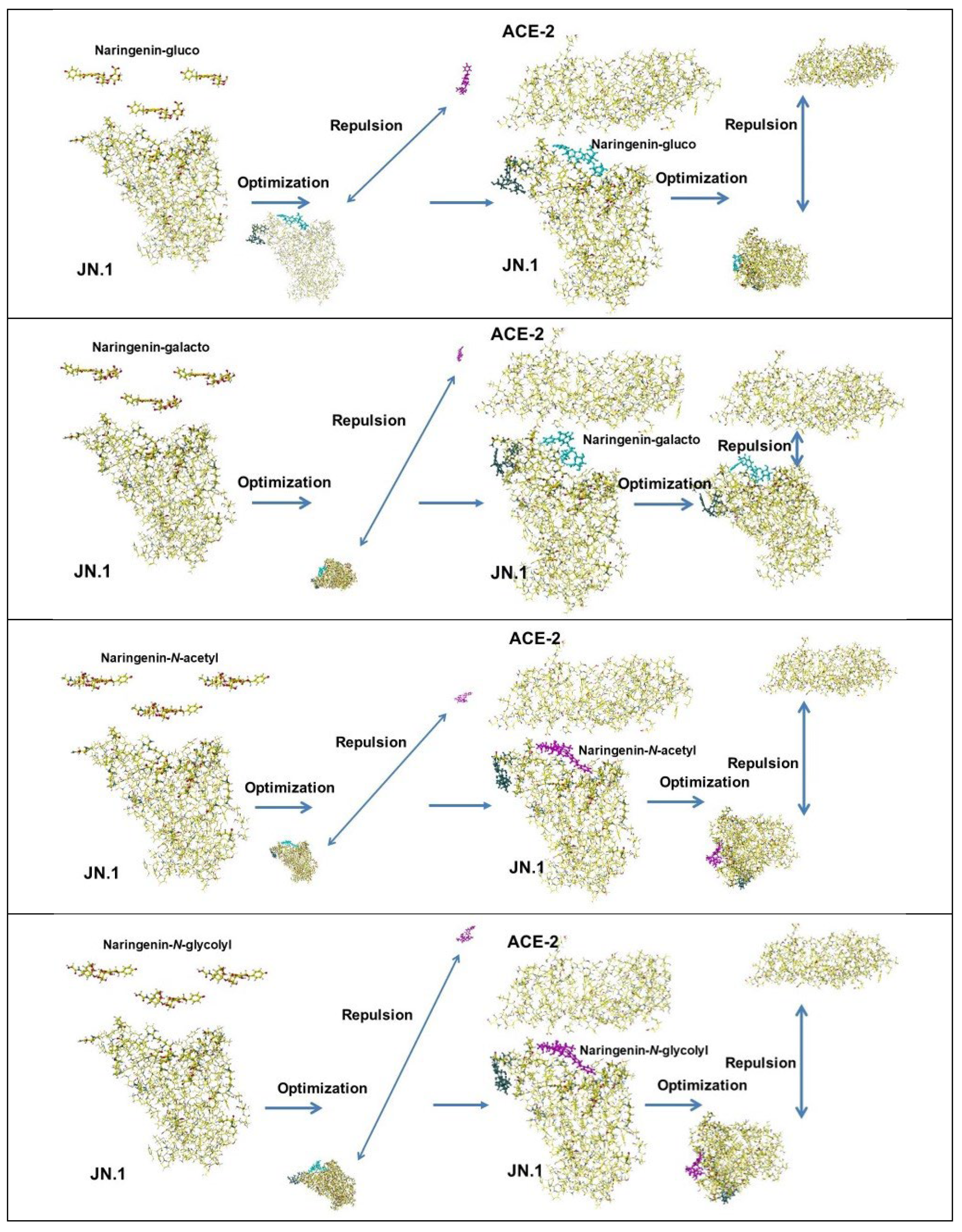

- Hanai, T. Visualization (XX) Glycosidation (Glycosylation), Effective derivatization, 2024, http://hanai-toshihiko.net/ quantitative in silico analytical chemistry/Covid-19 transmissibility and designing the binding inhibitors/.

- Lewis, A.L.; Toukach, P.; Bolton, E.; Chen, X.; Frank, M.; Lutteke, T.; Knirel, Y.; Schoenhofen, I.; Varki, A.; Vinogradov, E.; Woods, R.J.; Zachara, N.; Zhang, J.; Karmerling, J.P.; Neelamegham, S. Cataloging natural sialic and other nonulosonic acids (NulOs), and their representation using the Symbol Nomenclature for Glycans, Glycobiology. 2023, 33, 99-103. [CrossRef]

- Ling, A.J.W.; Chang, L.S.; Babji, A.S.; Latip, J. Koketsu, M.; Lim, S.J. Review of sialic acid’s biochemistry, sources, extraction and functions with special reference to edible bird’s nest Affiliations expand, Food Chem. 2022 Jan 15, 367,130755. [CrossRef]

- Stencel-Baerenwalg, J.E.; Reiss, K.; Reiter, D.K.; Stehle. T.; Dermody, T.S. The sweet spot: defining virus-sialic acid interactions, Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2014, 12, 739-749.

- Ghosh, S. Sialic acid and biology of life: An introduction, Sialic Acids and Sialoglycoconjugates in the Biology of Life, Health and Disease. 2020, 1–61. [CrossRef]

- Yagisawa, M.; Foster, P.J.; Hanaki, H.; Omura, S. Global trends in clinical trials of Ivermectin for Covid-19, Part 2. The Japanese Journal of Antibiotics, 2024, 77, 45. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M. Ivermectin could be a powerful drug for fighting cancer, The Epoch Times, Nar 21, 2024, 1-5.

- Zaidi, A.K.; Dehgani-Mobaraki, P. The mechanisms of action of Ivermectin against SARS-CoV-2- an extensive review. J. Antibiotics, 2022, 75, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanai, T. 2023-0917 Visualization (IV) of Pros and Cons of Ivermectin for S-RBDs and ACE-2 interaction and the inhibitors, http://hanai-tohihiko.net/ Quantitative in silico analytical chemistry/ COVID-19 transmissibility and designing the binding inhibitors, 2023.

- Hanai, T.; Shimada, K.; Koyama, N.; Nohara, Y.; Takayanagi, H.; (late) Kinoshita, T. Quantitative analysis of selective glycosylation of saccharides with aromatic amines, Carbohydrate Research, 2020, 498, 108171 http://doi.org/10.1016/j.carres.2020.108171 (Hanai, T.; Kato, K.; Furukoshi, E.; Hennmi, M.; Imoto, S.; Kotaka, A.; Shimada, K. Thoma, M.; Ishikawa, M.; Watanabe, T.; Ohgawara, E.; Koyama, N.; Furuhata, K.; Nagahara, K.; Takayanagi, H.; Nohara, Y.; Kinoshita, T.). [CrossRef]

- 108/Hanai, T. Evaluation of measuring methods of human serum albumin-drug binding affinity. Current Pharmaceutical Analysis, 2007, 3, 205–212. [Google Scholar]

- Pavelic, S.; Pavelic, K. Open questions over the COVID-19 pandemic, DOI: 10.5005/jp-hournals-11005-0027. Science, Art and Religion, 2023, 1, 211-220.

- Guan, Y.; Tang, G.; Li, L.; Shu, J.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, L.; Tang, J. Herbal medicine and gut microbiota: exploring untapped therapeutic potential in neurodegenerative disease management. Archives of Pharmacal Research, 2024, 47, 146–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tozser, J.; Benko, S. Natural compounds as regulators of NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated IK-1b production, Mediator of Inflammation, 2016, Article ID: 5460302, pp.16.

- Priyanjana Pramanik, Healthy lifestyle habits dramatically cut long-term COVID-19 risks, URL: pp.5, https://www.news-medical.net/news/20240730/.

- Mathew G. Frank, Jayson B. Ball, Shelby Hopkins, Tel Kelley, Angelina J. Kuzma, Robert S. Thompson, Monika Fleshner, Steven F. Maier, SARS-CoV-2 S1 subunit produces a protracted priming of the neuroinflammatory, physiological, and behavioral responses to a remote immune challenge: A role for corticosteroids, Brain, Behavior and Immunity, 121, 2024, 87-103. [CrossRef]

- Delphine Planas, Isabelle Staropoli, Cyril Planchais, Emilie Yab, Banujaa Jeyarajah, Yannis Rahou, Matthieu Prot, Florence Guivel-Benhassine, Frederic Lemoine, Vincent Enouf , Etienne SimonLoriere, Hugo Mouquet, Marie-Anne Rameix-Welti , Olivier Schwartz., Escape of SARS-CoV-2 variants KP1.1, LB.1 and KP3.3 from approved monoclonal antibodies, bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.08.20.608835; this version posted August 21, 2024, 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Mahta Mortezavi, Abigail Sloan, Ravi Shankar P. Singh, Luke F. Chen, MBBS, Jin Hyang Kim, Negin Shojaee, Sima S. Toussi, John Prybylski, Mary Lynn Baniecki, Arthur Bergman, Anindita Banerjee, Charlotte Allerton, Negar Niki Alami, Virologic Response and Safety of Ibuzatrelvir, a Novel SARS-cov-2 Antiviral, in Adults With COVID-19, Clinical Infectious Diseases, 1-19, 2024, acspted. [CrossRef]

- Yongzhi Lu, Qi Yang, Ting Ran, Guihua Zhan, Wenqi Li, Peiqi Zhou, Jielin Tang, Minxian Dai, Jinpeng Zhong, Hua Chen, Pan He, Anqi Zhou, Bao Xue, Jiayi Chen, Jiyun Zhang, Sidi Yang, Kunzhong Wu, Xinyu Wu, Miru Tang, Wei K. Zhang, Deyin Guo, Xinwen Chen, Hongming Chen, Jinsai Shang, Discovery of orally bioavailable SARS-CoV-2 papain-like protease inhibitor as a potential treatment for COVID-19 , Nature Communications | (2024) 15:10169, 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Topol., E. Long-term Long Covid, Ground Truths, 2023, Aug. 22, pp.12.

- Stefanie Kaiser, Steffen Kaiser, Jenny Reis, and Rolf Marschalek, Quantification of objective concentrations of DNA impurities in mRNA vaccines, SSRN https://papers.ssrn.com › papers.cfm.

- Lorena Diblasi, Martín Monteverde, David Nonis, PhD, Marcela Sangorrín, At Least 55Undeclared Chemical Elements Found in COVID-19 Vaccines from AstraZeneca, CanSino, Moderna, Pfizer, Sinopharm and Sputnik V, with Precise ICP-MS, International Journal of Vaccine Theory, Practice, and Research 3(2) October 11, 2024 | Page 1367. [CrossRef]

- Yingying Shi1 , Meixing Shi1 , Yi Wang 1 and Jian You, Progress and prospects of mRNA-based drugs in pre-clinical and clinical applications, Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy (2024) 9:322. [CrossRef]

| Amino acid | MIFS | MIHB | MIES | MIVW | Amino acid | MIFS | MIHB | MIES | MIVW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glu + Ala (A) | 10.48 | 0.07 | 11.35 | -0.92 | Glu + Pro (P) | 5.32 | -0.004 | 5.40 | 0.53 |

| Glu + Arg (E) | 84.05 | 25.29 | 64.31 | -3.30 | Glu + Thr (T) | 25.17 | 9.29 | 16.69 | 0.08 |

| Glu + Asn (N) | 33.56 | 18.74 | 16.47 | -2.17 | Glu + Tyr (Y) | 24.75 | 9.85 | 20.04 | -0.26 |

| Glu + Asp*(D) | -5.05 | -0.05 | -5.09 | 0.01 | Glu + Phe (F) | 12.61 | 0.07 | 9.41 | 2.91 |

| Glu + Glu*(E) | -5.73 | 0.02 | -5.75 | -0.01 | Glu + Ser (S) | 22.53 | 9.68 | 14.34 | -0.57 |

| Glu + Gln (Q) | 31.27 | 17.19 | 16.49 | -2.40 | Glu + Val (V) | 13.26 | 0.28 | 13.97 | -0.54 |

| Glu + Gly (G) | 16.41 | -0.11 | 15.50 | -1.06 | |||||

| Glu + His (H) | 21.20 | 4.30 | 17.04 | 0.25 | Tyr + Asn (N) | -27.71 | -14.69 | -13.24 | 5.56 |

| Glu + Leu (L) | 8.16 | 0.11 | 7.15 | 1.06 | Lys + Asn (N) | 43.92 | 27.77 | 20.73 | -4.65 |

| Glu + Lys (K) | 142.03 | 33.80 | 120.21 | -8.67 | Lys + Tyr (Y) | 31.38 | 28.95 | 5.17 | -3.52 . |

| WHO name | Lincage plus | Mutated amino acids |

|---|---|---|

| WT | N501 | |

| Alpha | B.1.1.7 | N501Y |

| Alpha plus | B.1.1.7+E484K | N501N, E484K*1 |

| Beta | B-1.351 | N417K, E484K, N-501Y |

| Delta | B.1.517.2 | L452R, T478K |

| Delta plus | AY.1 | K417N, L452R, T478K |

| Epsilon | B.1.427/B.1.429 | L452R |

| Eta | B.1.525 | E484K |

| Gamma | P.1 | K417N, E484K, N501Y |

| Gamma | P.1 | K417N, E484K, N501Y*2 |

| Iota | B.1.526 | E484k, (Eta B.1.525) |

| Iota | B.1.526.1 | L452R |

| Kappa | B.1.617.1 | L452R, E484Q |

| Kappa | B.1.620 | S477N, E484K |

| Lambda | C37 | L452Q, F490S |

| Mu | B.1.621 | R346K, E484K, N501Y |

| Theta | P.3 | E484K, N501Y, (Alpha B.1.7 + E484K) |

| Theta | B.1.616 | V483A |

| Zeta | P.2 | E484K, (Eta B.1.525) |

| Omicron | BA1 | G339D, S371L, S373P, S375F, K417N, N440K, G446S, S477N, T478K, |

| E484A, Q493R, G496S, Q498R, N501Y, Y505H, | ||

| Omicron | BA2 | G339D, S371F, S373P, S375F, T376A, D405N, R408S, K417N, N440K, S477N, T478K, E484A, Q493R, Q498R, N501Y, Y505H, |

| Omicron | B.2.75 | D339H, G446S, N460K, Q493R |

| Omicron | BA.4/5 | L452R, F486V, Q493R |

| Omicron | BQ.1 | K444T, N460K |

| Omicron | BQ.1.1 | R346T, K444T, N460K |

| Omicron | XBB | R346T, V445P, G446S, N460K, F486S, F490S, Q493R |

| Omicron | XBB.1.5 | F456L,N460K, F486P, F490S |

| Omicron | XBB.1.16 | T478R, F486P |

| Omicron | FE.1 | F456L, F486P, F490S |

| Omicron | EG.5 | F456L, N460K, S486P, FS490S |

| Omicron | BA.2.86 | I332V, D339H, R403K, V445H, G446S, N450F, L452W, N481K,483del, E484K, F486P |

| Omicron | BA.2.87.1 | G339D, S371F, S373P, S376F, T376A, D405N, R408S,K417T, N471K, E484A, Q498R, N501Y, Y506H |

| Omicron | HV.1 | R346T, L368I, T376A, D405N, K417N, N440K, V445P, G446S, L452R, V460K, S477N, T478K, E484A, F486P, F490S, Q493R, N501Y, Y505H |

| Omicron | JN.1 | T332V, K356T,T376A, R403K, D405N, K417N, N440K, V445H, G446S, N450D, L452W, L455S, V460K, S477N, T478K, N481K, 483V, E484A, F486P, F490P, Q493R, N501Y, Y505H |

| Omicron | JN.1.17 | T332V, K356T,T376A, R403K, D405N, K417N, N440K, V445H, G446S, N450D, L452W, L455S, V460K, S477N, T478K, N481K, 483V, E484A, F486P, F490P, Q493R, N501Y, Y505H, T572I |

| Omicron | JN.1.18 | T332V, R346T, K356T,T376A, R403K, D405N, K417N, N440K, V445H, G446S, N450D, L452W, L455S, V460K, S477N, T478K, N481K, 483V, E484A, F486P, F490P, Q493R, N501Y, Y505H, |

| Omicron | KP.2 | T332V, K356T, R346T,T376A, R403K, D405N, K417N, N440K, V445H, G446S, N450D, L452W, L455S, F456L, V460K, S477N, T478K, N481K, 483V, E484A, F486P, F490P, Q493R, N501Y, Y505H, T572I |

| Omicron | KP.3 | T332V, K356T,T376A, R403K, D405N, K417N, N440K, V445H, G446S, N450D, L452W, L455S, F456L, V460K, S477N, T478K, N481K, 483V, E484A, F486P, F490P, Q493E, N501Y, Y505H, T572I |

| Compounds | S-RBD | ACE-2 | C+A* | Compounds | S-RBD | ACE-2 | C+A* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetaminophen | B | B | - | Furosemide | B | B | - |

| Adrenaline | B | B | - | Gallic acid | B | R | R |

| Ascorbic acid | B | B | - | Gingerol | B | B | - |

| Aspirin I | B | R | PB | Glycyrrhizinic acid | B | R | R |

| Aspirin-O-mannoside M | B | B | - | Hydroxychloroquine | B | B | - |

| Aspirin-O-mannoside I | B | R | - | Ibuprofen I | B | R | R |

| Azithromycin | B | B | - | Ibuprofen M | B | B | B |

| Benzoic acid I | B | R | PB | Isopropylantipyrine | B | B | - |

| b-Blocker | B | B | - | Lactic acid I | B | B | R |

| m-Carboxyl-L-tyrosine | B | R | R | Lactic acid M | B | B | R |

| m-Carboxyl-L-tyrosine | B | R | R | Lopinavir | B | B | - |

| N-mannoside | Malic acid D-mannoside M | B | B | - | |||

| Catechin | B | B | - | Malic acid D-mannoside I | B | R | R |

| Captopril | B | B | - | Mefenamic acid I | B | R | R |

| Clofazimine | B | B | - | Mefloquine | B | B | - |

| Chlorophenyl amine- | B | B | - | Molnupiravir | B | B | B |

| Malonate | N3 | B | B | - | |||

| Citric acid | B | R | R | Nalidixic acid I | B | R | R |

| Citric acid dimethyl | B | R | R | Naproxen I | B | R | R |

| Citric acid trimethyl | B | B | PB | Oseltamivir | B | R | B |

| Citric acid O-mannoside | B | R | R | PF-07321332 | B | B | B |

| Citric acid di-O-mannoside | B | R | R | Probenecid I | B | R | - |

| Citric acid tri-O-mannoside | B | B | - | Remdesivir | B | B | - |

| Ethionamide | B | B | - | Ritonavir | B | B | - |

| Ephedrine | B | B | - | Unifenovir | B | B | - |

| Favipiravir | B | B | - | Unifenovir I | B | B | |

| Ferulic acid I | B | R | R | Xocova | B | B | B |

| Ferulic acid M | B | B | - | Zanamivir | B | R | B |

| Flavonoid | B | B |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).