1. Introduction

The sharing economy has given rise to new forms of organisation based on the social production and consumption of communities on digital platforms (Dredge & Gyimóthy, 2015; Pettica-Harris, deGama, & Ravishankar, 2020; Pelgander, Öberg, & Barkenäs, 2022). Both private and public actors are currently in the process of testing new digital business models for sharing services and resources, and there is great promise for the potential of the sharing economy to generate new forms of value that can disrupt and innovate traditional businesses (Cohen, Amoros & Lundy, 2017; Frenken & Schor, 2019). In the sharing economy, institutions or individuals with idle resources transfer the right to use goods to others through a third-party payment platform (Xiaoxi & Kai, 2021).

Platforms typically rely on socially progressive narratives of promoting more sustainable consumption of products and services, where consumers access rather than own resources (Bardhi & Eckhardt, 2012; Belk, 2014; Hamari, Sjöklint, & Ukkonen, 2015), combined with fostering communities of consumers who share social values and norms. In this way, sharing platforms are sometimes claimed to have the potential to empower citizens and consumers who join forces in both a common meaningful cause and an economic opportunity to provide decent employment and real value to consumers (Martin, 2016). On the other hand, the sharing economy blurs the boundaries between production and consumption, between full employment and casual labour, and between private and public life, and can therefore, as Martin (2016) argues, give rise to unregulated markets, posing a threat to regulated businesses and creating both monopoly and consumer risk.

The novelty of sharing as a mode of organising digital business platforms lies in their hybrid networking functions, which can serve commercial and social purposes simultaneously (Gyimóthy, 2017). Some platforms are about genuine sharing and pooling of resources, while others are more about facilitating monetised exchanges. Mair and Reischauer (2019) argue that there is no such thing as ’the’ sharing organisation - there is a high degree of pluralism. However, many platforms face what Besharov and Smith (2014) describe as “contested logics” - that is, they follow a dual logic of organising for both the common good and financial sustainability, and therefore need to balance these conflicting logics. Laurell and Sandström capture these dual logics when they define the sharing economy as: “ICT-enabled platforms for the exchange of goods and services that draw on non-market logics such as sharing, lending, gifting and swapping, as well as market logics such as renting and selling” (2017, p. 58). There is some debate about the value of the sharing economy in terms of shifting the logic away from sharing for the common good and sustainability, towards the economic opportunity of exploiting the discourse of sharing as a sustainable practice. Martin (2016, p. 149) goes so far as to say that: “although a critique of hyper-consumption was central to the emergence of the sharing economy niche, it was successfully reframed by regime actors as a purely economic opportunity”. The ideological ambiguity of the sharing economy is consistent with its many definitions, which have been variously referred to as the collaborative economy, the peer-to-peer economy, the participatory economy (Gössling, Larson & Pumputis, 2021), the on-demand economy (Cockain, 2016), the gig economy, the platform economy and post-capitalism (Peticca-Harris et al., 2020).

Sharing businesses typically operate on digital platforms involving community-based social production and consumption (Acquier, Daudigeos & Pinkse, 2017; Kassan & Orsi, 2012), although there is a high degree of diversity in sharing business model patterns (Curtis, 2021; Öberg, 2023). The value proposition lies in disintermediation, enabling direct transactions between providers and consumers for a fee (Vendrell-Herrero et al., 2018). Cutting out the middleman results in lower transaction costs and prices, on-demand access, instant payments, and verification opportunities for providers and users of the platform. Previous research has begun to categorise and discuss the business models of sharing platforms (e.g., Constantiou, Marton & Tuunainen, 2017; Curtis, 2021, Öberg, 2023), but in-depth empirical studies on how the business models of sharing platforms emerge and are organised remain scarce. Furthermore, little attention is paid to the importance of sharing ideology in facilitating the mobilisation and insourcing of community resources.

It is sometimes suggested that Airbnb’s unprecedented success lies in its ability to perform and enact ideological narratives of sharing to attract users to the platform (Cockayne, 2016; Gyimóthy, 2017). In this article, we follow Perkmann and Spicer’s (2010) performative approach to business models, which implies that they serve as narratives that persuade, typifications that legitimise, and recipes that guide social action. We pay attention to how activities, practices, actions and sayings impact (Mason, Kjellberg & Hagberg, 2014) the emergence of the sharing business model, and how contested and conflicting rationalities and ideologies are negotiated. We propose that sharing platforms perform ideological narratives (cf. Perkman & Spicer, 2010) to mobilise labour, community, resources and goodwill (cf. Peticca-Harris et al., 2020). These narratives can also influence the identity of community members and their sense of belonging, for example by alluding to users’ emotional engagement (cf. Perkmann & Spicer, 2010). Thus, the purpose of this paper is to understand how sharing business models emerge through processes of ideological narration.

To analyse how digital business models of sharing platforms emerge, we present a longitudinal case study describing the emergent process of how an entrepreneur and his team developed a digital sharing business model. The case company is an adventure tourism start-up in Sweden. Based on interviews, participant observation of work meetings and observations of the digital platform, the paper identifies four narratives during four phases of the emergence of the business model. The rest of the paper is structured as follows: First, we present our theoretical framework, which consists of a narrative perspective on business models. Second, we describe our methodology and research approach. Third, based on our theoretical framework, we show the narratives used during four phases of the platform’s development. Finally, we discuss the results of the study and draw some conclusions.

2. Theory: Performing Sharing Business Models

There is a large body of literature on the concept of business models (Massa, Tucci & Afuah, 2016), although some researchers argue that this research is still in its infancy (Wieland, Hartmann & Vargo, 2017). More recently, the concept has emerged in streams of literature on different variations of business models, such as sustainable business models (Nosratabadi et al., 2019) and digital business models (Verhoef & Bijmolt, 2019; Luz Martín-Peña, Díaz-Garrido & Sánchez-López, 2018). The sharing economy business model is a form of digital business model that is generally considered to be different from those of traditional marketplaces in its ability to “combine organisational and market mechanisms to coordinate platform participation and ultimately create value” (Constantiou, Marton & Tuunainen, 2017, pp. 231-232).

Perkmann and Spicer (2010) group research on general business models into three concepts. The first conception concerns business models as transactional structures, describing the way in which firms configure their transactions with groups of stakeholders. For example, Zott and Amit (2010, p. 219) define a business model as “the content, structure and governance of transactions designed to create value by exploiting business opportunities”. The second view is that business models are mechanisms for creating economic value, while the third view sees business models as devices for structuring and designing organisations. Massa, Tucci & Afuah (2017) also identify different conceptions of business models in the business literature, seeing three streams: business models as (1) attributes of real firms, (2) cognitive/linguistic schema, and (3) formal conceptual representations.

We argue that narratives can be seen as devices for structuring and designing sharing business models through cognitive/linguistic schemas. Thus, the emergence of sharing business models is achieved through the performance of narratives that produce material effects. We propose that it is possible to gain mobilising capacities through narratives linked to the consecrated concepts and ideologies of the sharing economy (Richardson, 2015), and that narratives define the meaning of the sharing business model in the actual context. Sharp (2018) shows how this narrative of the sharing economy is played out by the actors of the sharing platform, using an example quote from the co-founder of the sharing platform Sharable: “Imagine a city where everyone’s needs are met because people make the personal choice to share. Where everyone can create a meaningful livelihood.” (p. 520) Such narratives can attract (or repel) users, persuade investors, and control partners and employees.

Therefore, business models can be understood as being produced in and through narrative discourse (e.g., talk, texts, and conversations) that construct their communicative realities (cf. Brummans et al., 2014; Schoeneborn et al., 2014). To conceptualise how narratives are enacted, we draw on the communicative constitution of organisation (CCO) literature, in particular the Montreal School approach (Schoeneborn & Vasquez, 2017; Schoeneborn et al., 2014), with its emphasis on communication as a cultural practice that is constitutive of reality. This approach emphasises the processual nature of organisational identity and image formation (Craig, 1999). A central part of the CCO approach is that organising is done through communication in such a way that text and conversation give rise to a communicative reality (Brummans et al., 2014). From this perspective, business models are understood as actor-centred rather than firm-centred (Wieland et al., 2017).

We approach sharing business models from the perspective that they are performed through narratives (Schoeneborn & Trittin, 2013), which consist of promises in the hope of achieving something that lies beyond immediate reality. This is in line with Perkmann and Spicer’s (2010) argument that business models are performative in three ways: (1) as narratives that persuade, (2) as typifications that legitimise, and (3) as recipes that instruct. Thus, it is possible to understand business models as narrative devices that allow organisational actors to explore markets, recruit allies and increasingly perform the world they are narrating (Araujo & Easton, 2012; Doganova & Eyquem-Renault, 2009; Magretta, 2002). By skilfully and engagingly bringing the components of a story together in a narrative, entrepreneurs can frame innovations and new technologies as plausible and appealing. For example, business model narratives can mobilise fantasy scenarios, use widely known cultural myths, appeal to archetypal characters, construct a series of episodes and mobilise familiar literary tropes (Perkmann & Spicer, 2010). Perkmann and Spicer (2010) also argue that a business model allows a firm to associate itself with a particular type or identity, thereby creating a sense of legitimacy and meaning (Suchman, 1995), and to identify with similar firms while distancing itself from others (Fisher, 2020). Furthermore, Perkman and Spicer (2010) suggest that business models provide recipes that instruct actors in the firm on what to do. Here, the performance of business models is not only about narratives about the business model, but also about how these narratives are enacted by actors in the community. In this article, we show how the narratives of sharing business models involve the shaping of a particular shared identity, and thus the shaping of the sharing community.

3. Materials and Methods

The empirical material was collected from a longitudinal case study of a Swedish adventure tourism start-up, here referred to as Dawn. The start-up was intended to serve as a global intermediary for booking guiding services, mainly in kayaking, kitesurfing, and skiing. The company was founded by a local high-profile entrepreneur in adventure sports, anonymised in this paper as Adrian. In 2015, Adrian started working on establishing a business model for a digital sharing platform that would act as an intermediary between guide service providers and adventure tourists. The process of developing Dawn’s sharing business model, from idea to launch, was followed by two of the authors between October 2016 to December 2018. The case study was exploratory and inductive with the aim of understanding the dynamics of business modelling in this single setting (see Eisenhart, 1989), i.e., how this process continuously evolved and changed (e.g., Czarniawska, 2004a). The empirical material is summarised in

Table 1.

The process of how Adrian and his team developed the business model of the start-up was closely followed using interviews, observations of team meetings and conversations, and e-mail communication. The data was collected both through digital tools (the digital meeting tool Skype and the communication tool Slack) and by way of physical meetings. Also, observations of the Dawn platform and Adrian’s social media communication were performed. Fifteen in-depth interviews were conducted. The focus was on the entrepreneur, Adrian, as he was the sole owner of the start-up and the initiator of the business. Two interviews were conducted with one of the key people in the team that Adrian recruited, as he was the only person who stayed for a longer period. There were also thirty-four observations of the Dawn team – physically, via the meeting platform Skype, and the communication tool Slack. There was also an ongoing analysis of the texts and images that Adrian posted on the platform and social media over these two years.

Observations of work meetings, involving the entrepreneur and contract workers, and interviews were conducted either via Skype as in real-time video calls or face-to-face. We also observed in real-time conversations between the team members on the digital communication application Slack. The observations aimed to supplement the retrospective accounts of the process provided during the interviews with naturally occurring data in situ (Borda, 2006). This data enriched our understanding of the social complexity of developing a sharing business model. During these observations, we took a passive role as spectators, saving our questions for the end of the working sessions. We also carried out a narrative analysis of the texts and images on the platform and in the social media accounts (Instagram and Facebook) associated with Dawn.

The study can be characterised as action research because the researchers and the start-up together formed a collaborative research project funded by a research council. Action research is a methodological approach to conducting collaborative research with practitioners that informs scientific knowledge as well as practice, policy and community development (Borda, 2006). Delanty (1998) sees action research as a way of making the social sciences relevant and bringing about a more engaged level of scholarship in terms of connecting scholars with real social problems and the people affected by those problems. Similarly, Leca and Cruz (2021) discuss critical performativity as critical scholars engaged in direct practice. It should be emphasised, however, that we acted as observers of the start-up’s progress and did not contribute to its development as experts. The interviews were conducted as an exploratory dialogue and the actual focus of the research emerged over time. Initially, the entrepreneur consulted us on the design of the business model, without success: Over time, however, our position as scholars was gradually accepted.

The collected material was transcribed and then analysed as narrative performances. Narrative analysis was used to understand how the entrepreneur and his team constructed and negotiated the meanings of Dawn’s business model. We understand narrative meaning in terms of the meanings produced to make sense of everyday experiences, and we focused on how the narratives related to Dawn were enacted and re-enacted over time. The analysis of sense-making processes assumes that people create individual meaning (Weick, 1995) and that the sense-maker is an active agent in a continuum of explication, explanation, and exploration, moving from the passive role of recipient to co-author and finally author of her/his story. To make sense of our experiences, both for ourselves and for others, we plot events and turn them into stories – stories that organise events and occurrences to understand them better (Czarniawska, 2004b). The narrative analysis of the case study led to the identification of the master narratives used during the emergence of the sharing business model. These were traced back to ideologies, i.e., hegemonic belief systems (cf. Gramsci, 2005), which were negotiated between the entrepreneur and the team to gain internal and external support (i.e., labour, capital and users).

4. Results: Narrating a Sharing Business Model

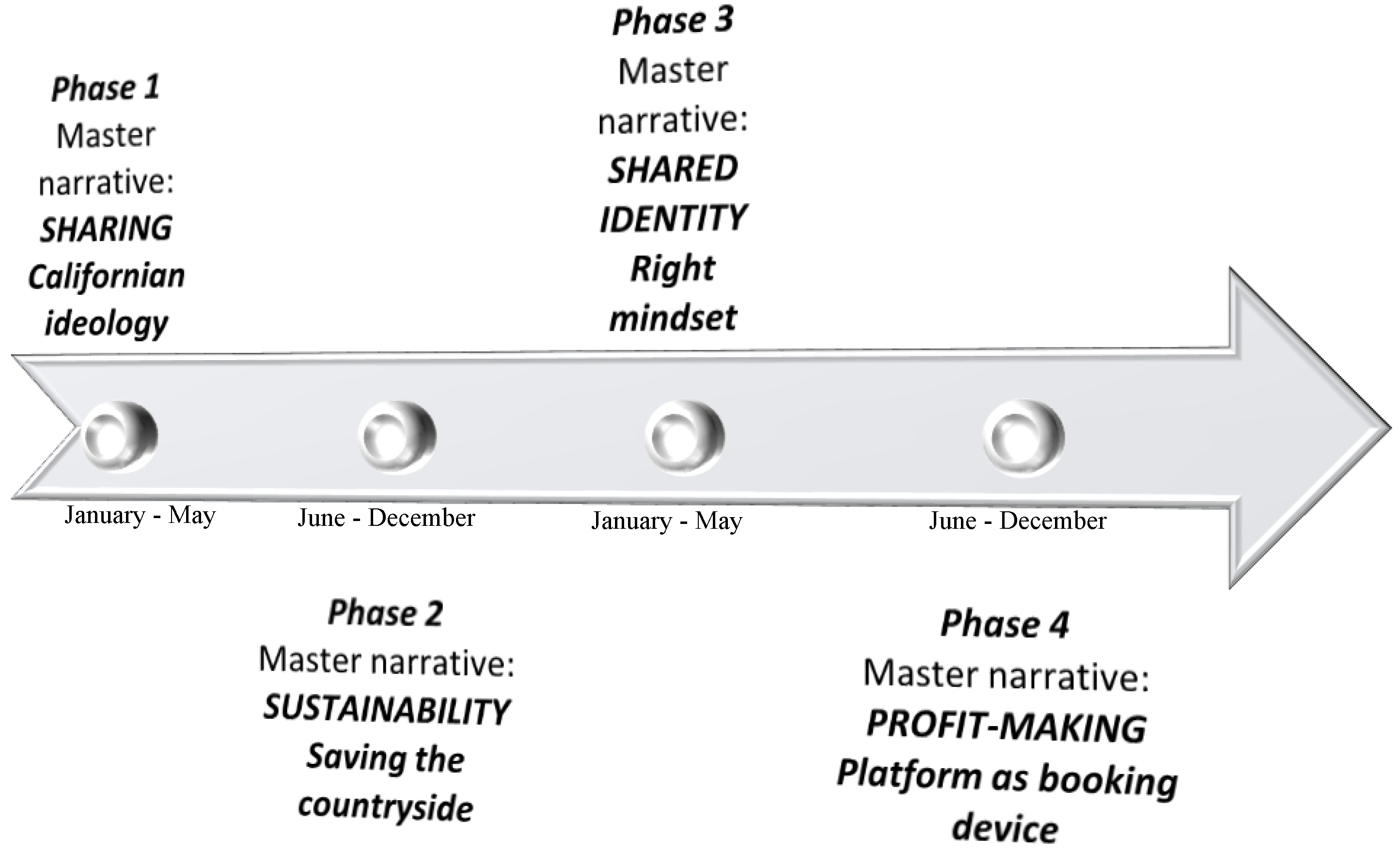

Narrative analysis of the development of the sharing business model generated four master narratives; i.e., sharing, environmental and social sustainability, shared identity, and profit-making. These master narratives occurred during the different phases of the development process.

4.1. Performing Narratives of Sharing

Sharing platforms balance between an altruistic ideology of sharing and a profit-driven logic (Gyimóthy, 2017; Laurell & Sandström, 2017). This fusion between the social aim of making the world a better place and a strong belief in the principles of the radical free market can be found in what is referred to as the Californian ideology. Barbrook and Cameron (1996, p. 1) describe this ideology as “the heterogenous orthodoxy of the information age”. This particular ideology originates in the 1960s Californian New Left movement and is argued to traditionally govern the narration of the Silicon Valley high-tech industries. It is characterized by a conflictual relationship between resistance to social conventions, the championing of progressive political issues, e.g., a universal basic income, progressive taxation and social justice, while simultaneously advocating market capitalism. Similar conflictual ideological values are present in the brand narratives of successful sharing organizations, e.g., Airbnb and Uber, and this is mimicked by smaller platform companies and start-ups. These narratives are often about driving social change and more sustainable modes of consumption and production in the form of sharing, and there is a strong ideological emphasis on community and anti-consumerism (Ozanne & Ballentine, 2010; O’Reagan & Choe, 2017). Airbnb’s community illustrates this ideology well in its vision of an egalitarian ecotopia. In the case of Dawn, similar communitarian values were communicated to legitimize and differentiate this start-up during the early stages of its development.

Members of the Dawn community, including the entrepreneur Adrian, his team of temporary IT professionals who set up the platform, and the prospective users of that platform (adventure guides and adventure consumers), all enacted the sharing ideology by adopting its narrative rhetoric. Adrian embodied the values of the ideology in leaving a promising career in finance for a less secure but more self-fulfilling job as an entrepreneur in adventure tourism. Adrian had high hopes for the platform as a professional meeting place for the service providers and users of the adventure sports community, with social purposes also being served at the same time. In December 2016, Adrian said: “initially, it was connected to my wish to create some form of platform for finding and interacting with like-minded friends and doing sports activities”. He saw it as a platform that would create opportunities for adventurers to meet and share their knowledge of how to create safe adventure experiences of high quality. Adrian also saw the platform as a way for adventure guides to become less dependent on tourism organizations, and other larger tourism intermediaries, e.g., the Swedish leisure company Skistar, in marketing and distributing their services. In his view, the Dawn platform would lead to a disintermediation process in the adventure industry in terms of taking away traditional intermediators between guides and customers. In this way, Adrian wanted to empower the adventure guides, saying: “I want to give competent people better opportunities to develop and have a better income doing what they are trained for” (Adrian, December 2016, interview).

Furthermore, Adrian also viewed the platform as an opportunity for human progress and societal development, saying: “What I’m trying to do with the platform is open up the adventure community to more … I have a vision of human progress, to push humanity in the right direction.” (Adrian, April 2017) For example, Adrian mentions the opportunity for rural places to use the platform for destination development in order to attract tourists and to create economic impact and employment for adventure guides. Thus, Adrian’s vision was connected to the adventure community on different levels. First, he performed a visionary narrative of developing a society promoting progress and knowledge. Secondly, he narrated stories of how to empower adventure guides and instructors and give them access to the market. Third, he performed attractive narratives of how people (consumers and guides) would benefit from the platform by means of opportunities for meeting like-minded people interested in adventure sports.

Adrian manifested altruistic values by emphasising that he had been working for several years with his business without any funding and that the people he had invited into the venture had been working for free or on low wages. In April 2017, a member of the team called Ben said: “I said early on that I wasn’t interested in the money. I joined the team because I thought it would be a fun service to develop.” These narrations of altruistic value, in terms of contributing to society and the adventure community, can be seen as a way to legitimise the business as a moral player in the sharing economy, but also as an attempt to justify and normalise flexible and precarious work (Cockayne, 2016). The narrative of ‘working just for fun’ may be seen as the way in which power operates in ideological mode. By establishing the business model on the basis of such an ideological narrative, it becomes possible to exercise power by means of domination through the construction of ideological values (Fleming & Spicer, 2014). This view of power captures a type of politics that defines the very terrain where actors understand their organizational situation (Fleming & Spicer, ibid, building on Luke’s (2005) view of power). By performing the narratives of the sharing ideology, Dawn (temporarily) mobilised a community of unsalaried workers, investors and platform users. Thus, appealing stories were narrated about both sharing and seemingly fantasy scenarios (Perkmann & Spicer, 2010) regarding how the platform would change the adventure industry on many levels.

4.2. Performing Narratives of Social and Environmental Sustainability

The second master narrative identified in the development of the Dawn sharing business model is tied both to the ideology of sustainability (Baptista, 2014) and to value conflicts between economic growth and social progression and wellbeing. The sharing economy is often viewed as having the potential to create more sustainable business models (Gupta & Chauhan, 2021), with sharing platform organizations often framing their activities in terms of social and environmental sustainability. Adrian had the strong vision of the platform leading to social sustainability for adventure sports practitioners.

My driving force goes beyond building a company. My incentives are a lot more about societal development and how the value of knowledge should be rewarded and remunerated. Many professionals aren’t paid for their knowledge and I think that this lack of compensation hinders the development of society. (…) Individuals in the countryside could be more fairly compensated for their knowledge, guiding people where they live, hunt, kayak, and so on. (Adrian, March 2017, interview)

The aim of empowering adventure guides was also part of how the Dawn business narrative was communicated via the platform.

We create new business possibilities through smart digital interactions and integrations and we aim to work closely with our users to expand local businesses and contribute to positive change. Being an outdoor professional is a challenging occupation. Dealing with conditions in order to bring safe experiences to clients is time consuming and demands extensive physical work. A line of work often driven by passion rather than financial gain. We aim to help you reduce time consumption, increase earnings from your services and keep your passion intact. For a flexible, free and secure future. We increase possibilities of reaching out and expand the horizon of financial possibilities and personal empowerment. (Dawn platform, August 2017, original language)

The narrative conveys the trade-off between passion and profit, and between individual and economic growth. It constructs the sharing platform in terms of striving for social and environmental sustainability, while at the same time leading to economic opportunity and employment.

We bring working possibilities to your local environment. (Dawn Platform, September 2017)

ENVIRONMENT. Our oceans, rivers, mountains, glaciers, forests and all other ecosystems with its inhabitants are interfered by human activity. We are dedicated to contribute and drive positive sustainable change for interacting with our planet. Sustainability is not enough. We believe in human growth and we need to address habitability in the perspective of holistic living conditions. We believe this is the future of co-living in a healthy, loving and joyful way. We highlight the benefits of an outdoor lifestyle for individual health and cognitive behaviour. Protect our playgrounds – This is our pledge! We support: Initiatives for preservation of rivers, Projects for securing water supplies, Dismantling of inefficient and non-sustainable energy sources, Renewable and abundant energy sources, Ocean cleaning, Ocean preservation, Removal of non-sustainable manufacturing, Sustainable public legislation, New technology for sustainable lifestyles. (Dawn Platform, November 2018, original language)

The Dawn narrative, at the outset, was an ideological endeavour regarding how a more sustainable lifestyle could be achieved for the adventure sports community, and society in general. The narratives dealt with freedom, social progress, knowledge, and breaking free from conventional lifestyles and ways of doing business, echoing the Californian ideology. In performing such narratives, Adrian and his team wanted to make the sharing business model legitimate, i.e., worth using, committing to, and investing in, in the adventure sports community.

4.3. Performing Narratives of a Shared Identity

The third master narrative in the Dawn business model concerns mobilising the adventure community by narrating a shared identity. Adrian embodied the adventurous outdoor lifestyle of this community. He worked as a stockbroker for many years in Stockholm, but decided to downsize into what he calls a ‘freer life close to nature’. He indulged his passion for adventure sports and became a certified instructor and guide in alpine skiing and kitesurfing. Prior to founding Dawn, he ran a bed & breakfast in a popular Swedish summer resort famous among surfers. Thus, even when Dawn was founded, he had an established position in the adventure sports communities of Sweden and Europe. The business model used primarily relied on this entrepreneur’s personal connections, relationships and position in the adventure community.

Sales are initially being made on the personal level. I have a rather large network in this business, in different segments, for several reasons. I have many contacts and I spent several seasons in the Alps. I’m a kitesurfing instructor, which is close to other surf sports like wind surfing, wave surfing, SUP, and so on. I have a great interest in outdoor activities, so I’m very active on an advanced level in several other sports like kayaking, trekking, cycling and I also have a network of private contacts. I’ve also worked for many years with xxx – a shop selling adventure sports equipment. (…) My personal connections and background will take me a long way in introducing this service. (Adrian, December 2016, interview)

A key feature of sharing business models is that they depend on a community of users to fill that platform with content, and to recruit other users to do so as well. Adrian’s idea was to co-create the platform with its users throughout the development process in a user-centric manner (cf. Buhalis et al., 2019). Also, Adrian argued that it was important to gather content for the platform and recruit members into the community before making it public. A way to achieve this was to narrate the lifestyle of the adventure community, in this way expressing the identity of Dawn. In his social media communication, relating both to him personally and to Dawn, narratives were performed referring to exclusive destinations for adventure sports insiders, e.g., islands in the Swedish archipelago and particular spots in the French Alps, in doing so reinforcing the identity of Dawn as a platform for adventurers.

We provide a powerful mobile operation management and financial transaction system for location-independent outdoor professionals. However, we aren’t just a service provider. We’re also skiers and surfers. We spend time with our users and their clients. That’s who we are and we’ll keep our service in tune with them. (…) We’re currently leaving a tropical summer in the Baltics for autumn surfing adventures and trekking in Europe together with our users. (Dawn Platform, November 2017)

Thus, Dawn was established by framing this business as a particular way of life. As Canniford and Karababa (2013) contend, adventure sports provide an alternative to the urban rationalised and restricted way of life and, as Adrian put it: “It’s much more than just the sport…it’s about alternative ways to live, almost a bit subversive”. Adrian and his team performed narratives depicting their identities as free and adventurous individuals. By means of being authentic to the users and connecting to the cultural world of adventure sports, the intention was to create a strong brand identity (cf. Holt, 2004).

The adventure identity was also reflected in the composition of the Dawn work team. Adrian spent a lot of time when recruiting people into the venture in order to ensure that new workers shared his values and priorities. The blurred boundary between work and everyday life in the creative and adventure industries has been acknowledged in previous research. Land and Taylor (2010), for instance, demonstrate how corporations use co-workers’ personal interests and lifestyles as resources in constructing brand identities. This conflation between the personal and the professional in the workplace may, on the one hand, be viewed as a way of humanizing the corporation and making it more authentic (Land & Taylor, 2010). But on the other, the valorisation of personal interests, identities, aspirations, and so on means that the capitalist logic is extended into people’s life worlds, resulting in companies exercising subjectification processes of what constitutes the person; his/her lived sense of identity and selfhood (Fleming & Spicer, 2014). The management of values and identities was visible in the case of Dawn. Members of the Dawn development team were constantly being replaced due to their incompatible views regarding what the company should stand for, and how it should be owned and organised. Adrian’s way of rationalizing the high rate of staff turnover was to ascribe it to his values and ambitions conflicting with those of his co-workers. This conflation of the private and the professional led to co-workers not sharing Adrian’s values and ambitions leaving the start-up.

One of the big challenges of leading this project has been finding a good team. Finding people with the right mindset and the right perspective for this business is very difficult. Is this person showing the right level of commitment to his work? During the processes, people have joined and left. They’ve left because our views on the purpose of the start-up have been at odds. Entering into a business relationship is like entering into a loving relationship. It’s exactly the same thing. You expect different things from one another, and if these do not match, you go your separate ways. (Adrian, October, 2017, interview)

During the early phase of the start-up, Adrian did not regard compelling narratives as sufficient to recruit like-minded co-workers and users to the platform. Instead, a value-based approach was adopted, focusing on rules and strictly formulated values that would attract and unite entrepreneurs, guides, and consumers in a form of homogenous community based on a shared identity. Thus, the business model was narrated in a way that provided explicit recipes (Perkmann & Spicer, 2010) which instruct community members as to what they should do. In order to come across as authentic, Adrian maintained that it was important for the values to also be conveyed as part of the respective co-worker’s individual ideological beliefs. A number of values were formulated by Adrian and his team, and expressed on the Dawn platform:

Working guidelines

- 1)

We listen to our users

- 2)

We have fun

- 3)

We stay active and adventurous

- 4)

We share our experiences

- 5)

We are locally present

- 6)

We spend time together

- 7)

We encourage innovation and new solutions

- 8)

We embrace new technology and practices that will enhance user experience and possibilities.

- 9)

Our decisions are holistic and long-term

- 10)

We work for sustainable practices (Dawn Platform, September 2017, original language)

These values served as instructions to members of the sharing community, defining community insiders and outsiders. Members were expected to have a particularly active lifestyle and to have the time to interact with other members. In this way, the sharing platform gained power through the subjectivisation of users, emotional engagement, and shared identity.

Dawn’s business model is narrated in this way to mobilise the ’right’ people who fit Dawn’s prescribed lifestyle and values. These lifestyles and values are visually reinforced on the platform and in social media with images of a free, carefree, and playful life in the outdoors. The visuals typically depict young, strong, white males surfing ocean waves or skiing through freshly fallen powder snow, often alone in the great outdoors. These narratives naturally appeal to certain groups of people. As such, they can be understood as an effective way of exercising power through subjectification (Fleming & Spicers, 2014). By communicating appealing narratives in a particular way, community members build and reinforce a shared identity based on adventure sports - an identity that defines meaning based on what is right and valuable, and who is to be considered part of the shared identity.

4.4. Performing Narratives of Profit-Making

The Dawn platform was designed from the outset to facilitate guiding services and activities in terms of planning, booking, payment, inventory and equipment exchange (e.g., sharing, leasing or swapping). The design themes of the platform were presented by Adrian as a novel structure and form of governance in adventure sports, with the potential to disrupt and change conventional business models in the industry by removing the intermediary between supplier and consumer. The intention was to build a strong community that would lead to lock-in effects. The value to guides and instructors was increased efficiency through reduced transaction costs. Gradually, more services would appear on the platform in a co-creative process within the industry community. As the sharing business model depended on the transaction fees generated through the platform, traction (a high volume of users) was critical to its success. Thus, although Dawn’s narratives were about sharing, sustainability and adventure sports lifestyles, they followed the dual logic of business for the common good and financial gain (cf. Besharov & Smith, 2014).

The narrative of profit-making was increasingly becoming visible as the Dawn team realised the difficulties of launching the platform, expressed here in the explanation of this start-up’s commission-based system.

Dawn is dedicated to create unique solutions for support of independent personal empowerment and long-term livelihood to outdoor professionals. Our product is a business management tool aimed to simplify administration and promote sales and client relations by addressing the challenges of working in nature. It is free to use our service, however your clients will pay a small service fee to Dawn when booking an event. (Dawn Platform, December, 2017, original language)

This links to sharing platforms’ market-based controversies regarding who makes the money (Murillo, Buckland & Val, 2017), and the fact that sharing platforms are criticised for taking the profit-driven logic to an extreme by not taking full responsibility for the working conditions emanating from their platforms (Frenken & Schor, 2019). In the case of Dawn, however, the failure to attract enough users onto the platform to make it financially sustainable led to bankruptcy.

5. Discussion

Since the rise of the sharing economy, critics have pointed to its inherent contradictions (Frenken & Schor, 2019; Martin, 2016). Sharing invigorates access-based consumption (and thus, it is argued, leads to more sustainable resource use) and provides economic opportunities and employment to marginalised social groups (Bardhi & Eckhardt, 2012; Belk, 2014). At the same time, sharing business models have been seen as a kind of ’neoliberalism on steroids’, with unregulated markets threatening regulated businesses, the rise of the precariat and the undermining of the welfare state (Murillo, Buckland & Val, 2017; Pettica-Harris et al., 2020). Cockayne (2016) discusses how sharing is used as an attempt to justify and normalise flexible and precarious work, by ambiguously linking capitalist exchange and altruistic social value. This fuzzy ideological hybrid, sometimes referred to as the ’Californian ideology’ (Barbrook & Cameron, 1996), has proved effective in empowering citizens and consumers to launch their ’movements’ and join forces in a common, meaningful cause. The Dawn case study illustrates how a sharing business model is built using the narratives of such an ideology.

Dawn’s business model claims to offer a novel structure and governance of guide services in adventure tourism with the potential to disrupt and transform the industry in ways that benefit both producers (guides) and consumers (adventurers). The value of this business model is claimed to be increased efficiency in matching guides and consumers by reducing transaction costs. The business model is carried out by communicating Dawn through ideological narratives of sharing, sustainability and a strong community identity based on adventure sports, while at the same time being profit-driven (

Figure 1).

The master narratives were consistent in promoting individual freedom and social progress to achieve a more sustainable adventure tourism industry that protects the environment of rural adventure destinations and helps local communities to thrive and remain vibrant. The sustainability narrative is a common way for new exchange platforms to gain legitimacy: However, sustainability aspects are often forgotten over time (Geissinger et al., 2019). On the Dawn platform, although the sustainability goals were explicitly narrated, there was a lack of strategies for both acting on and achieving these goals.

At the same time, an ideological narrative was presented, linked to a shared identity of (mainly) male bonding through sport. It can be argued that sustainability has little to do with the narrow identity that excluded groups of potential adventurers other than those targeted by the platform. Although these two narratives are seemingly contradictory, they can be understood as different ways of mobilising a particular group of people who are seen as essential to the success of the business. Both Dawn’s digital platform and social media targeted a community of white male adventurers by featuring almost exclusively images of white, young, and middle-aged men. Women were absent from the development process of Dawn, both as employees and as a target audience for the promotion of Dawn. Furthermore, in our interviews with the entrepreneur and his colleagues, there was no mention of female guides, instructors, skiers, or surfers. Relying on a homogeneous community of users and collaborators risks limiting the success of sharing platforms, as their capacity depends on their ability to attract many users.

Although the narratives performed by Adrian and his team initially focused on the pursuit of the common good, financial sustainability and profit-making became increasingly dominant. Thus, ideologically contradictory narratives were performed to establish the platform, reflecting the contradictory logic of the sharing business model (Besharov & Smith, 2014). These narratives are linked to the ideology of the radically free market economy and, at the same time, to an ideology based on altruistic and egalitarian values that aim to promote social change and sustainable modes of production and consumption. Paradoxically, the narratives underline the fact that the sharing platform is only accessible to a limited group of people, i.e., the insiders of the adventure sports community, albeit embedded in a discourse of an inclusive sharing economy. In

Figure 1, the narratives are plotted along the timeline of Dawn’s business model development, showing that the different narratives were more prevalent at different stages. The figure shows that narratives of sharing and sustainability were dominant in the first year of business model development, with narratives of community identity growing stronger over time. Narratives of profit-making grew over time and became dominant in the final phase, apparently due to the marked lack of financial resources available to develop the business model. Thus, tensions between communitarian and capitalist logics became more pronounced over time.

Our findings on how different master narratives were used to develop a sharing business model in adventure tourism may be common to other sharing platforms. In the case of Dawn, the ideological orientation of community values and beliefs was particularly emphasised, leading to an exclusive and shared identity that attracted too few users to allow the platform to expand.

6. Conclusions

This paper advances our understanding of the processes by which sharing business models evolve over time by situating them within the ideological narratives that shape their emergence. These narratives, enacted at different stages of the development process, reflect different and sometimes conflicting logics. While there is scholarly interest in sharing business models (e.g., Constantiou, Marton & Tuunainen, 2017; Ritter & Schanz, 2019; Öberg, 2023), less attention has been devoted to the discursive and ideological efforts that underpin their evolution. Our findings highlight the critical role of ideological embeddedness of sharing business models in shaping them. Arguably, all business models are, to some extent, narrated into being; however, we would argue that sharing business models is particularly susceptible to the performance of narratives linked to strong ideologies, such as claims of sharing, inclusion and sustainability. These ideological claims are not only used to establish engagement and legitimacy but also serve to build distinct brand identities to communicate uniqueness. As such, the evolution of sharing business models cannot be fully understood without examining the ideological frameworks and narratives that frame them. We call for further research to delve deeper into the narratives that shape sharing business models, exploring how various ideologies interact to shape their emergence and trajectory.

Funding

The authors would like to express their appreciation to BFUF (the R&D fund of the Swedish Tourism & Hospitality Industry) for their support in funding this research.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Acquier, A., Daudigeos, T., & Pinkse, J. (2017). Promises and paradoxes of the sharing economy: An organizing framework. Technological Forecasting & Social Change, 125 (December), 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Araujo, L., & Easton, G. (2012). Temporality in business networks: the role of narratives and management technologies. Industrial Marketing Management, 42(2), 312-318. [CrossRef]

- Baptista, J. A. (2014). The ideology of sustainability and the globalization of a future. Time & Society, 23(3), 358-379. [CrossRef]

- Barbrook, R., & Cameron, A. (1996). The Californian ideology. Science as Culture, 6(1), 44-72. [CrossRef]

- Bardhi, F., & Eckhardt, G. M. (2012). Access-based consumption: The case of car sharing. Journal of Consumer Research 39(4), 881-898. [CrossRef]

- Belk, R. (2014). You are what you can access: Sharing and collaborative consumption online. Journal of Business Research 67(8), 1595-1600. [CrossRef]

- Besharov, M. L., & Smith, W. K. (2014). Multiple institutional logics in organizations: Explaining their varied nature and implications. Academy of Management Review 39(3), 364-381. [CrossRef]

- Borda, O. F. (2006). Participatory (action) research in social theory: Origins and challenges. In Borda, O. F., Reason, P., & Bradbury, H. (eds) Handbook of Action Research: Participative Inquiry and Practice. London: Sage, pp. 27-37.

- Brummans, B. H. J. M., Cooren, F., Robichaud, D., & Taylor, J. R. (2014). Approaches to the communicative constitution of organizations. In: Putnam, L. L., & Mumby, D. K. (eds) The SAGE Handbook of Organizational Communication: Advances in Theory, Research and Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, pp. 173-194.

- Buhalis, D., Harwood, T., Bogicevic, V., Viglia, G., Beldona, S., & Hofacker, C. (2019). Technological disruptions in services: lessons from tourism and hospitality. Journal of Service Management. 30(4), 484-506. [CrossRef]

- Canniford, R., & Karababa, E. (2013). Partly primitive: discursive constructions of the domestic surfer. Consumption Markets & Culture, 16(2), 119-144. [CrossRef]

- Clegg, S. R., Courpasson, D., & Phillips, N. (2006). Power and Organizations. Thousand.

- Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Cockayne, D. G. (2016). Sharing and neoliberal discourse: the economic function of sharing in the digital on-demand economy. Geoforum, 77, 73-82. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, B., Amoros, J. E., & Lundy, L. (2017). The generative potential of emerging technology to support startups and new ecosystems. Business Horizons, 60: 741-745. [CrossRef]

- Constantiou, I., Marton, A., & Tuunainen, V. K. (2017). Four models of sharing economy.

- platforms. MIS Quarterly Executive 16(4), 231-251.https://aisel.aisnet.org/misqe/vol16/iss4/3.

- Craig, R. (1999). Communication Theory as a field. Communication Theory, 9(2), 119-161. [CrossRef]

- Curtis, S. K. (2021). Business model patterns in the sharing economy. Sustainable Production.

-

and Consumption, 27(July), 1650-1671. [CrossRef]

- Czarniawska, B. (2004a). On time, space, and action nets. Organization, 11(6), 773-791. [CrossRef]

- Czarniawska, B. (2004b). Narratives in Social Science Research. London: Sage.

- Delanty, G. (1998). Rethinking the university: The autonomy, contestation and reflexivity of knowledge. Social Epistemology, 12(1), 103-113. [CrossRef]

- Doganova, L., & Eyquem-Renault, M. (2009). What do business models do? Innovation.

- devices in technology entrepreneurship. Research Policy, 38(10), 1559-1570. [CrossRef]

- Dredge, D., & Gyimóthy, S. (2015). The collaborative economy and tourism: Critical.

- perspectives, questionable claims and silenced voices. Tourism Recreation Research 40(3): 286-302. DOI: 10.1080/02508281.2015.1086076.

- Eisenhart, K. M. (1989). Building Theories from Case Study Research, Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532-550.

- Fisher, G. (2020). The complexities of new venture legitimacy. Organization Theory, 1(2), 1-25. [CrossRef]

- Fleming, P., & Spicer, A. (2014). Power in management and organization science. Academy of Management Annals, 8(1), 237-298. [CrossRef]

- Frenken, K., & Schor, J. (2019). Putting the sharing economy into perspective. In Mont, O. (ed.) A Research Agenda for Sustainable Consumption Governance. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 121-135.

- Geissinger, A., Laurell, C., Öberg, C., & Sandstrom, C. (2019). How sustainable is the sharing economy? On the sustainability connotations of sharing economy platforms. Journal of Cleaner Production, 206(1), 419-429. [CrossRef]

- Gramsci, A. (2005). Selections from Prison Notebooks. Hoare, Q., & Nowell-Smith, G. (eds). New York: Lawrence & Wishart.

- Gupta, P., & Chauhan, S. (2021). Mapping intellectual structure and sustainability claims of.

- sharing economy research – a literature review. Sustainable Production & Consumption, 25 (January), 347–362. [CrossRef]

- Gyimóthy, S. (2017). Networked Cultures in the Collaborative Economy. In: Dredge, D., Gyimóthy, S. (eds) Collaborative Economy and Tourism. Tourism on the Verge. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S., Larson, M., Pumputis, A. (2021). Mutual surveillance on Airbnb. Annals of Tourism Research, 91 (November), 103314, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Hamari, J., Sjöklint, M., & Ukkonen, A. (2015). The sharing economy: Why people.

- participate in collaborative consumption. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 67(9), 2047-2059. [CrossRef]

- Holt, D. B. (2004). How Brands Become Icons: The Principles of Cultural Branding. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press.

- Kassan, J., & Orsi, J. (2012). Legal landscape of the sharing economy. The Journal of.

-

Environmental Law & Litigation, 27(1), 1–20. http://hdl.handle.net/1794/12245.

- Land, C., & Taylor, S. (2010). Surf’s up: Work, life, balance and brand in a new age.

- capitalist organization. Sociology, 44(3), 395-413. [CrossRef]

- Laurell, C., & Sandström, C. (2017). The sharing economy in social media: Analyzing tensions between market and non-market logics. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 125, 58-65. [CrossRef]

- Leca, B., & Barin Cruz, L. (2021). Enabling critical performativity: The role of institutional context and critical performative work. Organization, 28(6), 903–929. [CrossRef]

- Luz Martín-Peña, M., Díaz-Garrido, E., & Sánchez-López, J. M. (2018). The digitalization and servitization of manufacturing: A review on digital business models. Strategic Change, 27(2), 91-99. [CrossRef]

- Lukes, S. (2005). Power – a radical view, second edition. New York: Palgrave McMillan.

- Mair, J., & Reischauer, G. (2019). Capturing the dynamics of the sharing economy: Institutional research on the plural forms and practices of sharing economy organizations. Technological Forecasting & Social Change, 125, 11-20. [CrossRef]

- Magretta, J. (2002). Why business models matter. Harvard Business Review, 80 (May), 86–92, 133.

- Martin, C. J. (2016). The sharing economy: A pathway to sustainability or a nightmarish form.

- of neoliberal capitalism? Ecological Economics, 121, 149-159. [CrossRef]

- Mason, K., Kjellberg, H., & Hagberg, J. (2015). Exploring the performativity of marketing: theories, practices and devices. Journal of Marketing Management, 31(1-2), 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Massa, L., Tucci, C. L., & Afuah, A. (2017). A critical assessment of business model research. Academy of Management Annals, 11(1), 73-104. [CrossRef]

- Murillo, D., Buckland, H., & Val, E. (2017). Then the sharing economy becomes.

- neoliberalism on steroids: Unravelling the controversies. Technological Forecasting & Social Change, 125 (December), 66-76. [CrossRef]

- Nosratabadi, S., Mosavi, A., Shamshirband, S., Kazimieras, Zavadskas, E., Rakotonirainy, A., & Chau, K. W. (2019). Sustainable Business Models: A Review. Sustainability. 11(6),1663. [CrossRef]

- Öberg, C. (2023). Towards a typology of sharing business model transformation. Technovation, 123, 102722. [CrossRef]

- O’Reagan, D. M., & Choe, J. (2017). Cultural capitalism: Manipulation and control in.

- Airbnb’s intersection with tourism. In Dredge, D., & Gyimóthy, S. (eds) The Collaborative Economy: Tourism Social Science Perspectives. Cham: Springer, pp. 153-169.

- Ozanne, L. K., & Ballantine, P. W. (2010). Sharing as a form of anti-consumption? An.

- examination of toy library users. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 9(6), 485-498. [CrossRef]

- Pelgander, L., Öberg, C., & Barkenäs, L. (2022). Trust and the sharing economy, Digital Business, 2(2), 100048, ISSN 2666-9544, . [CrossRef]

- Perkmann, M., & Spicer, A. (2010). What are business models? Developing a theory of.

- performative representations. In Phillips, N., Sewell, G., & Griffiths, D. (eds) Technology and Organization: Essays in Honour of Joan Woodward (Research in the Sociology of Organizations Vol. 29). Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited, pp. 265-275. [CrossRef]

- Peticca-Harris, A., deGama, N., & Ravishankar, M. N. (2020). Postcapitalist precarious work and those in the ‘drivers’ seat: Exploring the motivations and lived experiences of Uber drivers in Canada. Organization 27(1): 36-59. DOI: 10.1080/0969160X.2018.1515156.

- Richardson, L. (2015). Performing the sharing economy. Geoforum, 67 (December), 121-129. [CrossRef]

- Ritter, M., & Schanz, H. (2019). The sharing economy: A comprehensive business model.

- framework. Journal of Cleaner Production, 213(10), 320-33. [CrossRef]

- Schoeneborn, D., & Trittin, H. (2013). Transcending transmission: Towards a constitutive.

- perspective on CSR communication. Corporate Communications: An International.

- Journal, 18(2), 193–211. [CrossRef]

- Schoeneborn, D., & Vasquez, C. (2017). Communication as constitutive of organization. In.

- C. R. Scott, & L. K. Lewis (Eds.). International encyclopedia of organizational communication. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Schoeneborn, D., Blaschke, S., Cooren, F., McPhee, R. D., Seidl, D., & Taylor, J. R. (2014).

- The three schools of CCO thinking: Interactive dialogue and systematic comparison. Management Communication Quarterly, 28(2), 285-316. [CrossRef]

- Sharp, D. (2018). Sharing Cities for Urban Transformation: Narrative, Policy and Practice. Urban Policy and Research, 36(4), 513-526. DOI: 10.1080/08111146.2017.1421533.

- Suchman, M. (1995). Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 571-610. [CrossRef]

- Vendrell-Herrero, F., Parry, G., Bustinza, O. F., & Gomez, E. (2018). Digital business models: Taxonomy and future research avenues. Strategic Change 27(2), 87-90.

- https://doi.org/10.1002/jsc.2183. [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, P. C., & Bijmolt, T. H. A. (2019). Marketing perspectives on digital business models: A framework and overview of the special issue, International Journal of Research in Marketing, 36(3), 341-349. [CrossRef]

- Weick, K. E. (1995). Sensemaking in Organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Wieland, H., Hartmann, N., & Vargo, S. L. (2017). Business models as service strategy. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45(6), 925-943. [CrossRef]

- Xiaoxi, Z., & Kai, L. (2021). A systematic review and future directions of the sharing economy: business models, operational insights and environment-based utilities, Journal of Cleaner Production, 290, 125209. [CrossRef]

- Zott, C., & Amit, R. (2010). Business model design: An activity system perspective. Long Range Planning 43(2-3), 216-226. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).