1. Introduction

Organ preservation temperature has regained renewed interest in the field of transplantation, particularly for lung transplantation (LTx). Meticulous organ management and high-viability preservation are essential in maintaining quality, improving outcomes, and overcoming logistical limitations. Traditionally, static ice storage (SIS) has been the primary method of preserving donor lungs, involving storage in an ice-filled box [

1,

2,

3]. Despite its global and long-standing use, current practices with SIS are not standardized and has several drawbacks. Storage in ice creates an environment that poses risk of freezing injury, limiting the safe ischemic time to 6-8 hours [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. A common assumption is that SIS maintains organs at 4°C, based on studies from over 30 years ago [

9,

10,

11]. However, recent advancements in precision temperature measurement have not been widely applied to this area, leaving critical gaps in our understanding of lung preservation during SIS [

12].

We hypothesize that organ temperature during standard SIS is not maintained at 4°C and could decrease to 0°C, resulting in freezing injury of organs. We aim to investigate the temperature changes of donor lung cooling and preservation using standard SIS protocols through a combination of preclinical experiments and clinical observations.

2. Methods

This is a combined porcine and clinical study.

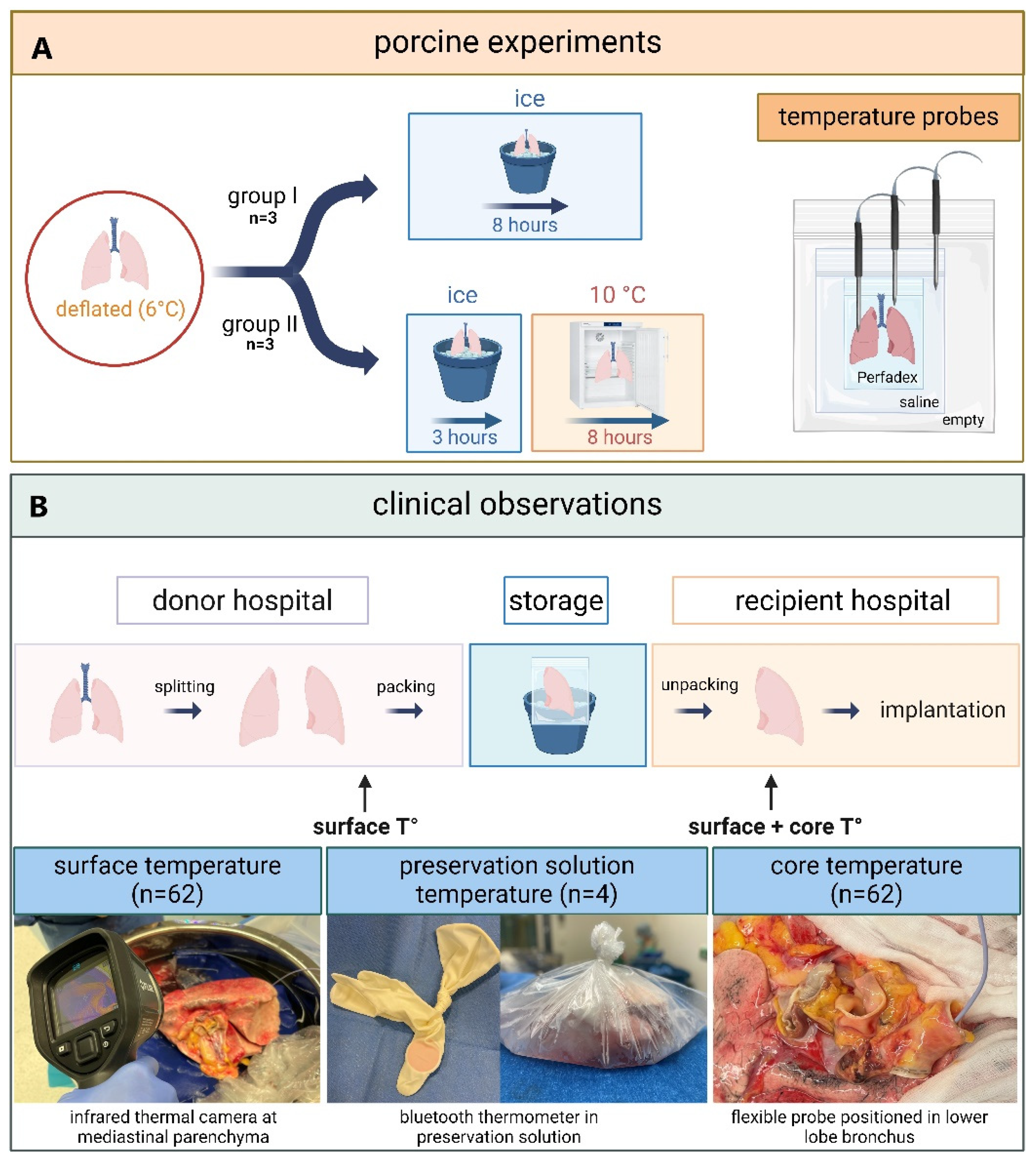

2.1. Porcine

The preclinical study on porcine lungs (

Figure 1) was carried out by researchers from Paragonix Technologies. Porcine double lung-blocks, procured by a commercial medical supplier (Sierra for Medical Science) were delivered in a frozen state to the laboratory. Double lung-blocks were used for each experiment. The pig lungs were thawed to a temperature of 6°C and packed in three bags as recommended by the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) [

13]. The lungs were left deflated, resulting in a lower surface-to-mass ratio and reduced thermal conductivity, which may have slowed cooling. The inner bag contained Perfadex (XVIVO, Mölndal, Sweden) preservation solution, the middle bag contained saline 0.9% NaCl with no added slushed ice, and the outer bag remained empty. The lung-blocks were allocated to two study arms during which temperature was systematically recorded using hardwired temperature probes (CX402-xxM, InTemp, Bourne, MA, USA). A sharp probe was inserted in the right or left lower lobe at 2.5cm depth to measure tissue temperature (tissueT°). A second probe was positioned in the inner bag to measure preservation solution temperature (psT°). The third probe was positioned in the second bag to measure saline temperature (salineT°). Temperature was measured at 30 second intervals throughout the experiment.

Three lung-blocks were allocated to the first study group (group I) of 8 h SIS. After packaging and placement of temperature probes (cf. supra), porcine lungs were placed in an icebox. One saline monitoring experiment was excluded from the analysis due to an incorrect calibration of the temperature probe. Three other lung-blocks were allocated to the second study group (group II) with 3 h SIS followed by 8 h storage in a standard 10°C laboratory refrigerator.

2.2. Clinical

The clinical observational study was performed at University Hospitals Leuven and an overview is shown in

Figure 1. Patients provided written consent and the study was approved by the Ethics Committee UZ/KU Leuven (S67052).

2.2.1. Preservation Solution Temperature During Static Ice Storage in Clinical Lung Transplantation

We longitudinally measured psT° during SIS of four left donor lungs. Standard practice for SIS, recommended by the ISHLT was followed [

13]. Lungs were split in the donor center and individually packed in three bags. The first bag contained 1L Organ Care System (OCS,Transmedics, MA, USA) lung preservation solution. The second bag contained 1L saline solution with added slushed ice. The third, outter bag remained empty. OCS and saline were stored on ice prior to packing. To measure psT° during SIS, a Tempo Disc bluetooth thermometer (Blue Maestro, London, UK) was put in two surgical gloves and positioned in the inner bag filled with OCS. At 1-minute intervals, psT° was measured during SIS until the lung was removed from the bag for implantation. The recored psT° data were transferred to the Tempo Plus 2 application (Blue Maestro, London, UK) for analysis.

2.2.2. Surface and Core Temperature of Human Donor Lungs Before and After Static Ice Storage

Surface (surfaceT°) and core (coreT°) temperatures were measured in clinical donor lungs stored using standard SIS protocols (cf. supra).8 Thirty-one sequential sing-lung transplants were performed, resulting in 62 lungs for which temperatures were measured. First, surfaceT° was measured just prior to packing of the lungs in the donor center. Immediately after unpacking the lung at the end of SIS in the transplant center (within 5 min), surfaceT° and coreT° were measured. Lungs were individually unpacked in the transplant center, according to the implantation sequence. SurfaceT° was measured with an E8 FLIR infrared thermal camera (Teledyne, USA) directed at the mediastinal lung parenchyma. coreT° was measured with a 6Fr flexible temperature probe (SKU 22-GP406-S, Alleset, Jiaxing, China) immediately wedged in the lower lobe bronchus after removing the stapler line.

2.3. Statistics

For porcine experiments, data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), derived from the average of results obtained from three independent experiments.

Clinical donor characteristics were summarized using median ± interquartile range (IQR) for continuous data (age body mass index (BMI), ventilator time, PaO2/FiO2 ratio, cold ischemic storage duration) and were summarized with observed frequencies and percentages (%) for categorical data (sex, donor type). surfaceT° and coreT° were summarized as median (IQR) and plotted with Graphpad (Prism, USA).

3. Results

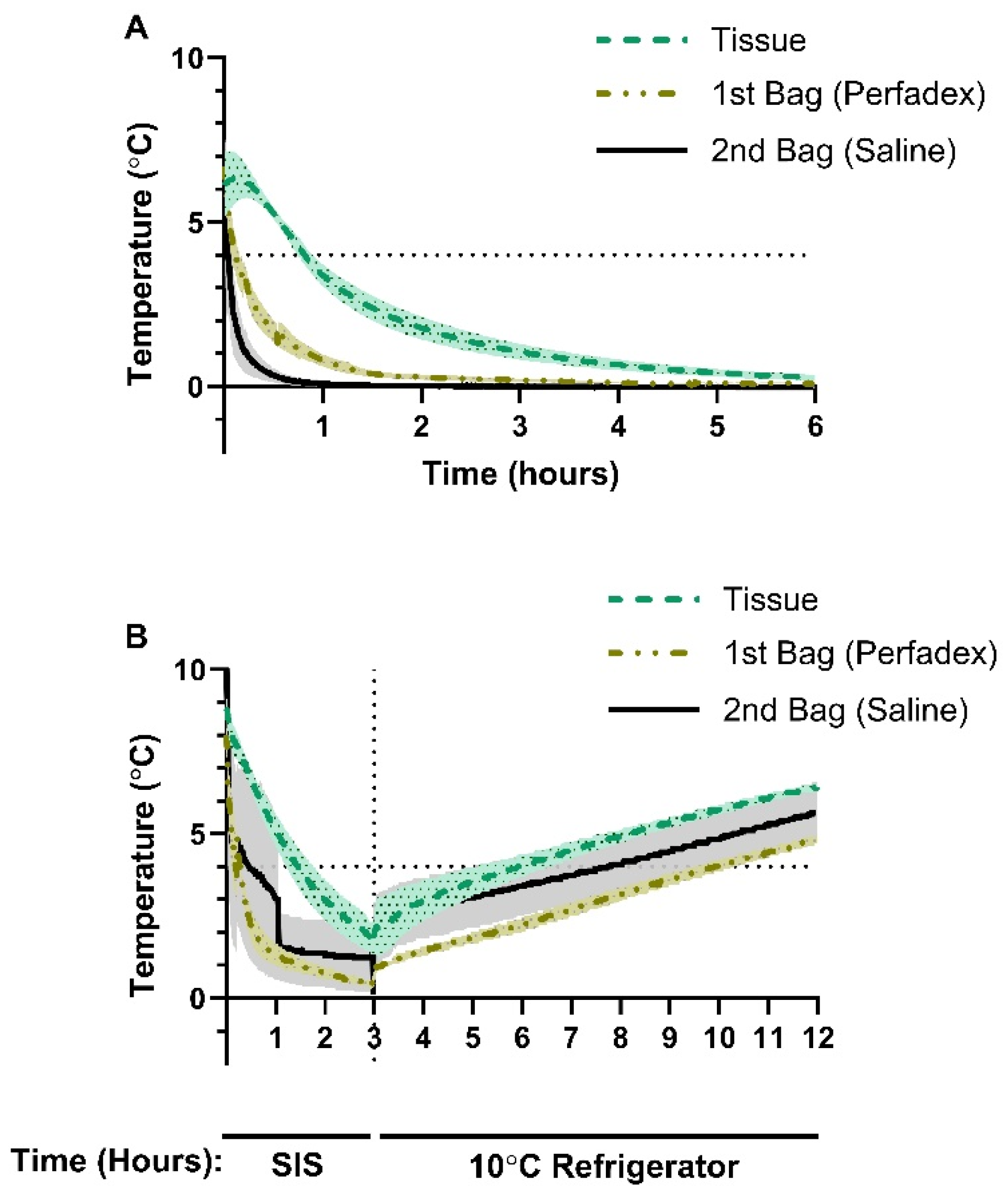

3.1. Porcine Lung Temperature Evolution During Static Ice Storage

At the start of SIS in group I, average tissueT° was 6.11°C, psT° was 6.70°C, and salineT° was 7.08°C (

Figure 2A). After 1 h, the average tissueT° dropped below 4°C, reaching 3.38°C, before continuing to decrease to 1.77°C after 2 h and 0.66°C after 4 h (

Figure 2A). psT° dropped rapidly to 0.80°C after 1 h, 0.28°C after 2 h, and 0.12°C after 4 h (

Figure 2A). salineT°dropped to a temperature of 0.08°C after 1 h and dropped below 0°C after 2.25 h, with the lowest average temperature of -0.03°C recorded over the 8 h observation period (

Figure 2A).

3.2. Porcine Lung Temperature During Static Ice Storage Followed by Storage at 10°C

In group II, we investigated how porcine lung temperature changed when exposed to 10°C following a 3 h period of SIS. After SIS and prior to transfer to the 10°C refrigerator, average lung tissueT° was 1.90°C, psT° was 0.57°C, and salineT was 1.57°C (

Figure 2B). Exposure to 10°C resulted in a gradual temperature increase with a maximal average tissueT° of 6.47°C, psT° of 4.83°C, and salineT° of 5.63°C (

Figure 2B). Time to reach 4°C after SIS followed by 10°C exposure was 2.90 h for tissueT°, 6.90 h for psT° and 7.73 h for salineT°. (

Figure 2B). Over the 8 h rewarming period, none of the temperature probes recorded a measurement of 10°C (

Figure 2B).

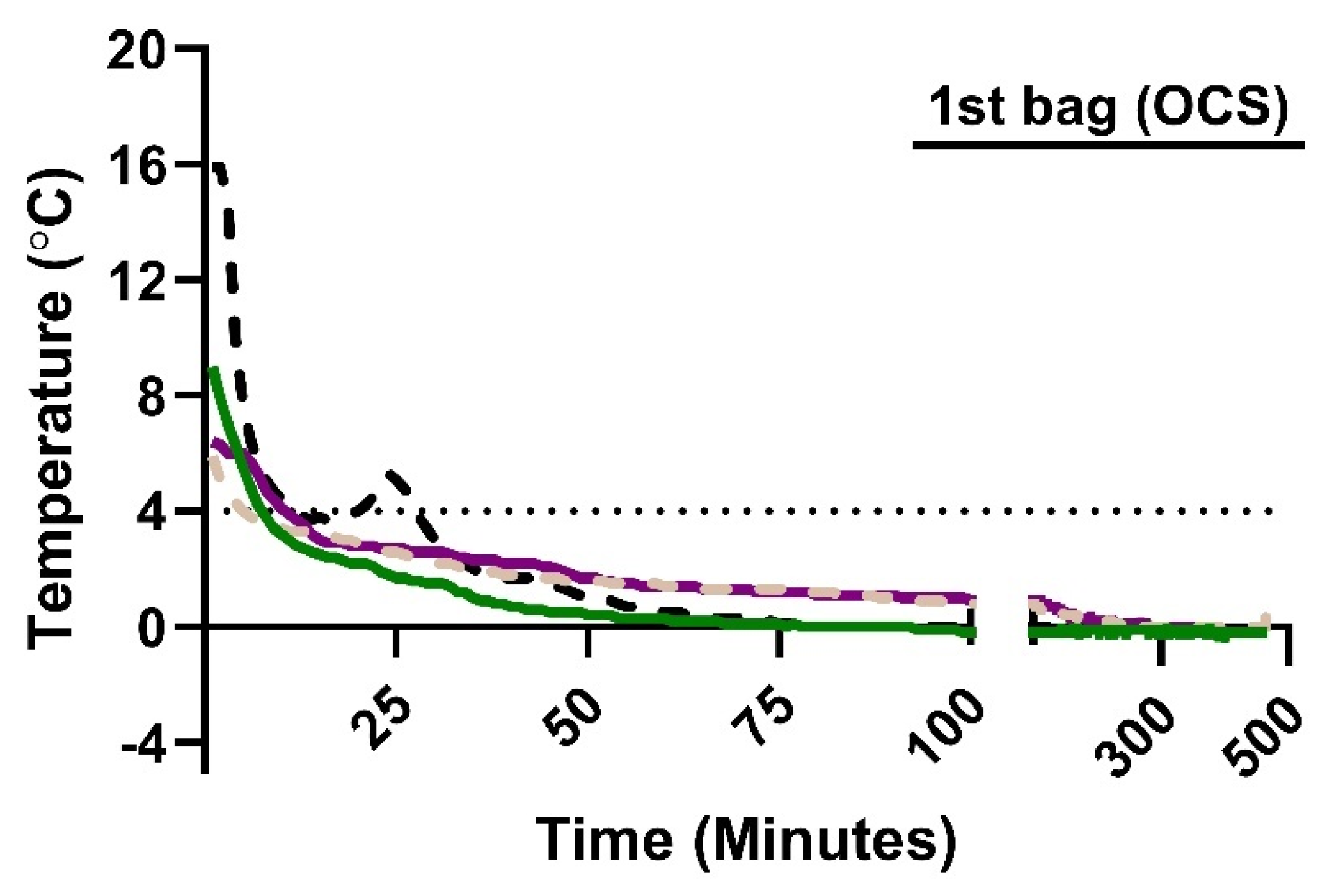

3.3. Longitudinal Monitoring of Preservation Solution Temperature in Human Donor Lungs

Measurement of psT° with the Bluetooth thermometer in OCS showed that the initial psT° at the start of SIS is heterogenous—ranging from 5.9°C to 15.9°C—but that the psT° dropped below 4°C within 9-13 minutes of SIS (

Figure 3). In two cases, psT° dropped to 0.0°C after 78 minutes and remained at, or below, 0.0°C for the duration of SIS (

Figure 3). In two other cases, psT° dropped to 1.0°C within 91 minutes before gradually decreasing to 0.0°C after 259 and 267 minutes.

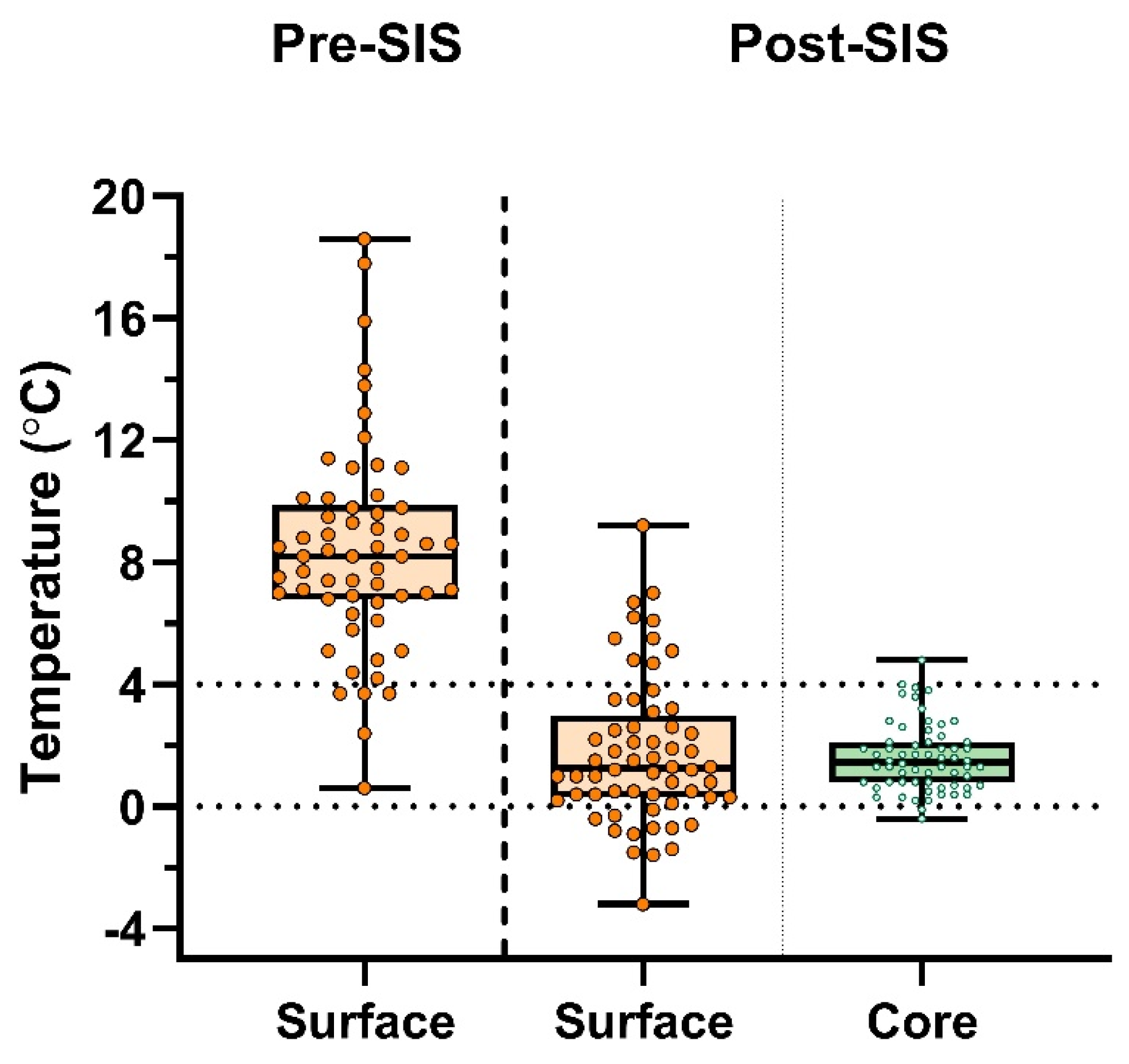

3.4. Human Donor Lung Temperature Before and After Static Ice Storage

To study the effect of SIS on organ temperature in clinical LTx cases, we measured surfaceT° and coreT° before and after SIS temperatures in donor lungs. The donor characteristics are shown in

Table 1.

Donor lungs from 31 sequential single-lung transplant procedures (n=62 lungs) were measured measured at each timepoint. Average donor age was 59.0 ± 20.0 years, 54.8% were male, and 48.4% were donations after circulatory death (DCD-III). Prior to lung packing, median surfaceT° was 8.2°C (6.78°C–9.88°C). Median SIS duration was 254 minutes (min–max; 79–609). Immediately after unpacking in the transplant center, median surfaceT° was 1.25°C (0.30°C–2.98°C), and median coreT° was 1.45°C (0.78°C–2.10°C) (

Figure 4).

4. Discussion

Our preclinical observations revealed that preservation using ice results in temperatures below 4°C, reaching as low as 0°C. Moreover, it is inaccurate to assume ice as being 4°C. Generally, substances consolidate as they reach maximum density, but water is an exception to this rule. While 4°C represents the temperature at which water achieves its maximum density, its actual freezing point at atmospheric pressure is 0°C [

14].

Supplementary Figure 1 Furthermore, saline (0.9% NaCl), commonly used in the second preservation bag, has a freezing point approximating -0.59°C. Additionally, Robicsek et al. observed saline ice temperatures as low as -7.1°C in clinical cardiac surgery setting, with slush ice forming at -0.6°C [

15].

Organ temperature during preservation depends on several factors, including the quantity of preservation bags, presence of ice slush in the second bag, the volume of preservation solution and the preservation duration. We show that SIS poses a great risk of freezing injury, especially in donor organs with extended durations of preservation. In our clinical setting, psT° dropped to 0°C rapidly in one case after 97 minutes, while in other cases it decreased more gradually eventually reaching 0°C. Furthermore, post-SIS temperatures, particularly for surfaceT°, had a large variability, with temperatures below 0°C. Previously, Horch et al. showed that organs stored on ice averaged 2°C, reaching 0°C by 6 hours [

16]. Furthermore, several studies demonstrated that cold-induced injury associated with SIS can directly reduce vascular muscle function [

10,

11], promote vascular edema [

17] and compromise mitochondrial viability and ATP levels, causing increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels [

18]. Direct freezing injury can potentially denaturate proteins and disrupt protoplasmic structures at the cell surface [

15]. Formation of ice crystals at near-freezing temperatures can result in electrolyte and osmotic imbalances leading to organelle swelling and mitochondrial damage [

19,

20]. Taken together, avoiding freezing injury by limiting SIS to 6 hours has been advised [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8].

Recently, controlled hypothermic storage (CHS) emerged as an alternative to SIS. It has been shown in porcine experiments that lung storage in a device set at 10°C better maintains physiological function and mitochondrial health compared to 4°C storage [

18,

21,

22]. Furthermore, a proof-of-concept using CHS in 5 patients demonstrated the potential to extend cold ischemia time, allowing overnight briding of LTx procedures to daytime hours [

18]. Safely extending ischemia times reduces time constraints and logistical challenges, primarily encountered in the context of distant procurements. This was confirmed in a multicenter prospective non-randomized trial comparing 70 CHS with 140 propensity matched SIS cases.

23 No significant differences for primary graft dysfunction grade 3 (PGD3) at 72 h (5.7% for CHS vs. 9.3% for SIS), 30-day -and 1-year survival were noted [

23]. With CHS, median total ischemic time of the second implanted lung was 14h08 [

23]. However, in these studies, the lungs were initially preserved with SIS during transport, followed by CHS in an incubator set at 10°C [

18,

23]. This implies that the average preservation temperature was below 10°C as shown in our porcine experiments. The reported clinical data may therefore not represent the full potential of CHS for improved lung preservation, and implies potential freezing injury during transportation. The impact of this initial freezing step, which was not included in the initial pre-clinical experiments 30 years ago, has to be further studied [

4,

24,

25,

26].

To ensure optimal preservation temperature from procurement to implantation, CHS devices should therefore be transportable. Several have been developed: LungGuard, Xport and Vitalpack [

27]. We previously showed that in a multicenter observational study, extending lung preservation of 13 double lung transplants beyond 15 h appears to be safe applying CHS with LUNGguard. This is a transportable device, maintaining temperature at 4-8°C [

28]. The average preservation temperature in this study was 7°C. Although this was a high-risk recipient cohort, including 3 high-urgent patients, no PGD3 at T72 was observed.

In the new era of CHS, it is important to appreciate the distinction between the actual organ and preservation device temperature, and their effect on clinical outcome. Our findings advocate the importance of correct measurement and reporting of organ temperatures in future experimental and clinical research.

Our study is limited by potential variations in temperature probes that could arise due to numerous factors, including minor differences in calibration. Regarding the porcine study, porcine lungs were procured, frozen delivered, then thawed and deflated. The deflated state of these lungs results in reduced surface area in contact with the preservation solution, which lowers thermal conductivity. Despite this, the total lung mass difference in deflated vs. inflated lungs are negligible in terms of thermal impact (e.g., inflated 6 liters of air corresponding to a mass of 7.76 grams). Thus, this preclinical study represented an overestimation of temperatures reached with SIS. However, the results were comparable to those collected during the clinical portion of this study. For longitudinal analyses in human LTx, we only recorded longitudinal measurements for psT° and not for the temperature of the donor lungs. An uncontrollable variable in the clinical study was preservation duration, which might have contributed to a large variation in post-SIS surfaceT° and coreT°. Additionally, the placement of an endobronchial probe provides an approximate measurement of the coreT°, but it is not feasible to directly measure the temperature of the tissue without causing iatrogenic injury by inserting a probe in the parenchyma. It is noteworthy to address that not all centers use the same packing methods. While some centers pack double lungs together, our center prefers to pack right and left lungs separately at the procurement center.

5. Conclusions

this study provides the first clinical evidence that lung SIS does not maintain lung temperature at 4°C, but exhibits a large variability with unpredictable post preservation temperatures. The findings of this study remind us to reconsider the benefits versus risks of using SIS for donor lungs, especially for extended criteria donors where the ischemic time with suboptimal temperatures can significantly affect organ quality. In this era of CHS, exact organ temperatures should be measured and reported to better understand the impact of different preservation devices and protocols.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Figure S1: phase transition behaviour of water.

Author Contributions

Clinical study design: I.C., J.V.S., A.B., X.J., A.L.P., L.J.C.; Porcine study design: P.P., L.Ch., B.B., J.H.; Analyzing data: I.C., J.V.S., A.B., X.J., A.L.P., P.P., L.Ch., B.B., J.H., L.J.C.; Original draft preparation, I.C., J.V.S., P.P., L.J.C.; visualization, I.C., J.V.S., L.J.C.; supervision LJ.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

LJC is a senior clinical investigator for research Foundation Flanders (FWO; 18E2B24N).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The clinical observational study was performed at University Hospitals Leuven and an overview is shown in

Figure 1. Patients provided written consent and the study was approved by the Ethics Committee UZ/KU Leuven (S67052).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to specific format of data presentation (continuous temperature measurement).

Acknowledgments

Editorial support in the form of writing the first draft of introduction, results and methodology sections, technical editing, and copyediting was provided by Indus MedTech Solutions (Aarti Urs). Statistics were performed by and discussion section, as well as final draft was written by researchers from the Leuven Lung Transplant group. We thank all members of the Laboratory of respiratory diseases and thoracic Surgery (BREATHE), the department of thoracic surgery, transplant coordinators, anesthesiologists, pulmonologists, intensive care physicians, physiotherapists, nursing staff and the medical students involved in the Leuven Lung Transplant Program at the University Hospitals Leuven (Leuven, Belgium).

Conflicts of Interest

PP, LCh and BB are full-time employees of Paragonix Technologies, Inc. No company-related device was used in this study. The other authors (IC, JVS, AB, XJ, AP, JH, LJC) report no conflict of interest to disclose as described by the Journal of Clinical Medicine.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CHS |

Controlled hypothermic storage |

| coreT° |

Core temperature |

| FiO2

|

Fraction of inspired oxygen |

| ISHLT |

International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation |

| LTx |

Lung transplantation |

| OCS |

Organ Care System preservation solution |

| psT° |

Preservation solution temperature |

| PaO2

|

Partial pressure of arterial oxygen |

| PGD3 |

Primary graft dysfunction grade 3 |

| ROS |

Reactive oxygen species |

| salineT° |

Saline temperature |

| SIS |

Static ice storage |

| surfaceT° |

Surface temperature |

| tissueT° |

Tissue temperature |

References

- Daily PO, Adamson RM, Jones BH, Dembitsky WP, Moreno-Cabral RJ. Comparisons of methods of myocardial hypothermia for cardiac transplantation. Ann Thorac Surg. 1996;61(2):679-683. [CrossRef]

- Cooper JD, Pearson FG, Patterson GA, et al. Technique of successful lung transplantation in humans. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1987;93(2):173-181.

- Jing L, Yao L, Zhao M, Peng L ping, Liu M. Organ preservation: from the past to the future. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2018;39(5):845-857. [CrossRef]

- Wang LS, Yoshikawa K, Miyoshi S, et al. The effect of ischemic time and temperature on lung preservation in a simple ex vivo rabbit model used for functional assessment. Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 1989;98(3):333-342. [CrossRef]

- Mulvihill MS, Yerokun BA, Davis RP, Ranney DN, Daneshmand MA, Hartwig MG. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation following lung transplantation: indications and survival. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. 2018;37(2):259-267. [CrossRef]

- Thabut G, Mal H, Cerrina J, et al. Graft Ischemic Time and Outcome of Lung Transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(7):786-791. [CrossRef]

- Pirenne J. Time to think out of the (ice) box. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2010;15(2):147-149. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, O’Brien ME, Yu J, et al. Prolonged Cold Ischemia Induces Necroptotic Cell Death in Ischemia–Reperfusion Injury and Contributes to Primary Graft Dysfunction after Lung Transplantation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2019;61(2):244-256. [CrossRef]

- Guibert EE, Petrenko AY, Balaban CL, Somov AY, Rodriguez J V., Fuller BJ. Organ Preservation: Current Concepts and New Strategies for the Next Decade. Transfusion Medicine and Hemotherapy. 2011;38(2):125-142. [CrossRef]

- Keon WJ, Hendry PJ, Taichman GC, Mainwood GW. Cardiac Transplantation: The Ideal Myocardial Temperature for Graft Transport. Ann Thorac Surg. 1988;46(3):337-341. [CrossRef]

- Ingemansson R, Budrikis A, Bolys R, Sjöberg T, Steen S. Effect of temperature in long-term preservation of vascular endothelial and smooth muscle function. Ann Thorac Surg. 1996;61(5):1413-1417. [CrossRef]

- Courtwright A, Cantu E. Evaluation and Management of the Potential Lung Donor. Clin Chest Med. 2017;38(4):751-759. [CrossRef]

- Copeland H, Hayanga JWA, Neyrinck A, et al. Donor heart and lung procurement: A consensus statement. Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. 2020;39(6):501-517. [CrossRef]

- David R. Lide. CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. In: 85th ed. ; 2004:990-1003.

- Robicsek F, Duncan GD, Rice HE, Robicsek SA. Experiments with a bowl of saline: the hidden risk of hypothermic-osmotic damage during topical cardiac cooling. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1989;97(3):461-466.

- Horch DF, Mehlitz T, Laurich O, et al. Organ transport temperature box: multicenter study on transport temperature of organs. Transplant Proc. 2002;34(6):2320. [CrossRef]

- Hendry PJ, Walley VM, Koshal A, Masters RG, Keon WJ. Are temperatures attained by donor hearts during transport too cold? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1989;98(4):517-522.

- Ali A, Wang A, Ribeiro RVP, et al. Static lung storage at 10°C maintains mitochondrial health and preserves donor organ function. Sci Transl Med. 2021;13(611). [CrossRef]

- Dias CL, Ala-Nissila T, Wong-ekkabut J, Vattulainen I, Grant M, Karttunen M. The hydrophobic effect and its role in cold denaturation. Cryobiology. 2010;60(1):91-99. [CrossRef]

- Chen J, Liu X, Hu Y, Chen X, Tan S. Cryopreservation of tissues and organs: present, bottlenecks, and future. Front Vet Sci. 2023;10. [CrossRef]

- Abdelnour-Berchtold E, Ali A, Baciu C, et al. Evaluation of 10°C as the optimal storage temperature for aspiration-injured donor lungs in a large animal transplant model. Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. 2022;41(12):1679-1688. [CrossRef]

- Wang A, Ali A, Baciu C, et al. Metabolomic studies reveal an organ-protective hibernation state in donor lungs preserved at 10 °C. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. Published online August 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ali A, Hoetzenecker K, Luis Campo-Cañaveral de la Cruz J, et al. Extension of Cold Static Donor Lung Preservation at 10°C. NEJM Evidence. 2023;2(6). [CrossRef]

- Date H, Matsumura A, Manchester JK, Cooper JM, Lowry OH, Cooper JD. Changes in alveolar oxygen and carbon dioxide concentration and oxygen consumption during lung preservation: The maintenance of aerobic metabolism during lung preservation. Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 1993;105(3):492-501. [CrossRef]

- Date H, Lima O, Matsumura A, Tsuji H, d’Avignon DA, Cooper JD. In a canine model, lung preservation at 10° C is superior to that at 4° C: A comparison of two preservation temperatures on lung function and on adenosine triphosphate level measured by phosphorus 31-nuclear magnetic resonance. Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 1992;103(4):773-780. [CrossRef]

- Date H, Matsumura A, Manchester JK, et al. Evaluation of lung metabolism during successful twenty-four-hour canine lung preservation. Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 1993;105(3):480-491. [CrossRef]

- Cenik I, Van Slambrouck J, Provoost AL, et al. Controlled Hypothermic Storage for Lung Preservation: Leaving the Ice Age Behind. [CrossRef]

- Novysedlak R, Provoost AL, Langer NB, et al. Extended Ischemic Time (> 15 Hours) Using Controlled Hypothermic Storage in Lung Transplantation: A Multicenter Experience. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. Published online February 2024. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).