1. Introduction

The acute phase response (APR) is a well-documented phenomenon in vertebrates, characterized by the rapid synthesis and release of acute-phase proteins (APPs) in response to infection, inflammation, or tissue injury [

1]. It has been widely used in the early diagnosis of diseases. Serum amyloid A (SAA), one of the most abundant APPs, has been extensively studied in vertebrates for its role in opsonization, phagocytosis, and modulation of the inflammatory response [

2,

3]. In vertebrates, SAA is primarily synthesized in the liver during the APR and is secreted into the bloodstream. It binds to high-density lipoprotein (HDL) and accumulates in the tissues, particularly at sites of inflammation. SAA exhibits multiple functions, including opsonization of gram-negative bacteria, modulation of cytokine production, and stimulation of the innate immune system [

4,

5]. Its role in innate immunity is further underscored by its ability to induce the production of other immune mediators, such as complement components and reactive oxygen species [

6].

Despite the well-documented roles of SAA in vertebrates, the existence and function of SAA-like proteins in invertebrates remain largely unknown. The primary challenge lies in the fact that invertebrates lack a liver, the primary site of SAA synthesis in vertebrates [

7]. Analyze using transcriptome and genome data and in several protostome taxa made up of 21 marine bivalve species and basal metazoans, 51 SAA-like proteins were retrieved [

7]. These SAA-like proteins share certain structural features with vertebrate SAA, including a conserved N-terminal region and a variable C-terminal region[

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. They are typically small, with molecular weights ranging from 10 to 20 kDa. Recently, proteins with structural and functional similarities to SAA have been identified in some invertebrate species. They are often synthesized in response to immune challenges, such as bacterial or viral infections, and are secreted into the hemolymph or other body fluids [

8,

9]. For example, in oyster

Crassostrea hongkongensis, SAA was found highestly expressed in the mantle, and was significantly up-regulated in haemocytes following bacterial challenge [

9]. In

Tridacna crocea, the recombinant protein r

TcSAA was found to bind bacteria

Vibrio coralliilyticus and

Vibrio alginolyticus and reduce the lethality rate of the clams after bacterial challenge [

10]. Currently, the information of SAA in invertebrates is still limited.

The Pacific oyster

Crassostrea gigas is filter-feeding bivalve and globally important economically farmed specie. However, infectious diseases have become the main obstacle to the development of the oyster farming industry, and a variety of diseases have seriously threatened the farming output of

Crassostrea gigas [

12]. Given that the rearing environments of oysters are usually coastal and estuarine areas, it is a big challenging for environmental management and control when dealing with the outbreak of infectious diseases. [

13,

14]. The early diagnosis of oyster infection is critical to prevent large-scale mortality, and the acute phase response related SAA might provide a fresh idea [

15]. However, the molecular features and potential functions of SAA protein in

Crassostrea gigas is still not clear. The present study identified the only

saa gene (

CgSAA) from oyster

C. gigas, and its molecular characteristics, expression patter as well as possible functions were further investigated, with the aim to explore the evolution of SAAs and the possible role of

CgSAA in the immune response.

3. Results

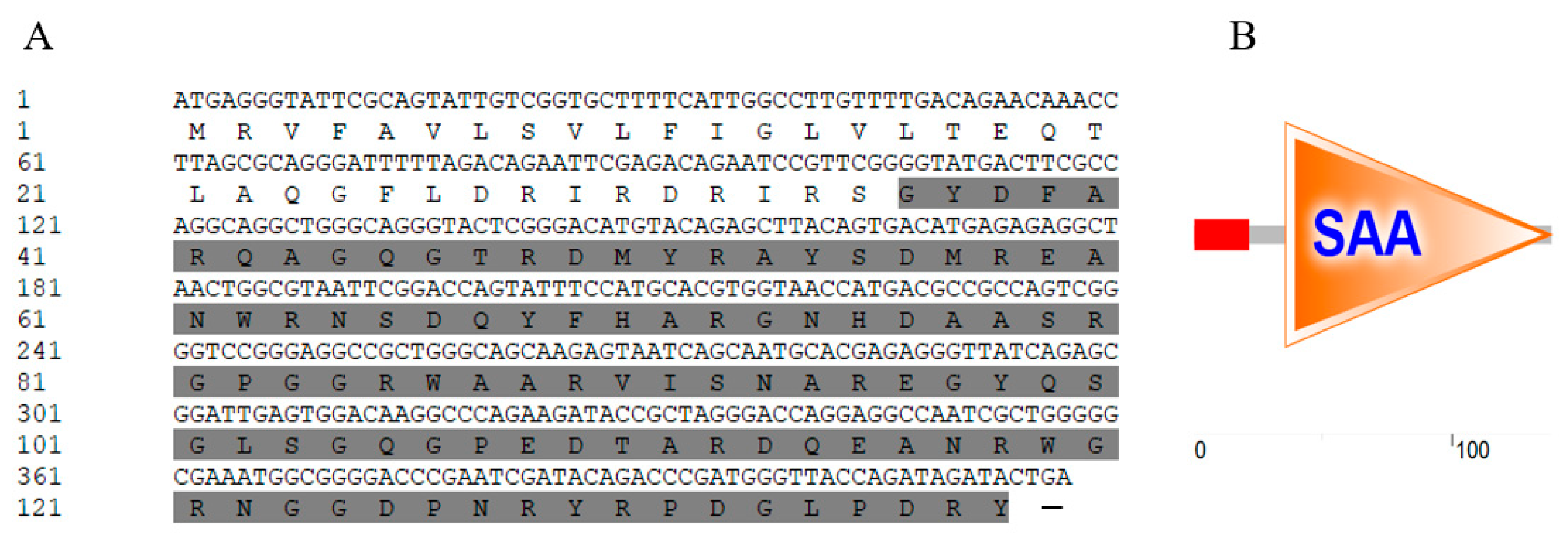

3.1. The Molecular Characters of CgSAA Gene

The open reading frame (ORF) of

CgSAA measured 417 bp, which was responsible for encoding a presumed polypeptide composed of 138 amino acid residues. This polypeptide had an estimated molecular weight of 15.66 kDa and a theoretical isoelectric point (pI) of 9.84 (

Figure 1A). The structural prediction of the amino acid sequence indicates that the oyster

CgSAA is composed of two parts. The signal peptide covers the amino acid residues from residues 1-22, the

CgSAA domain extends from residues 36-138 (

Figure 1B).

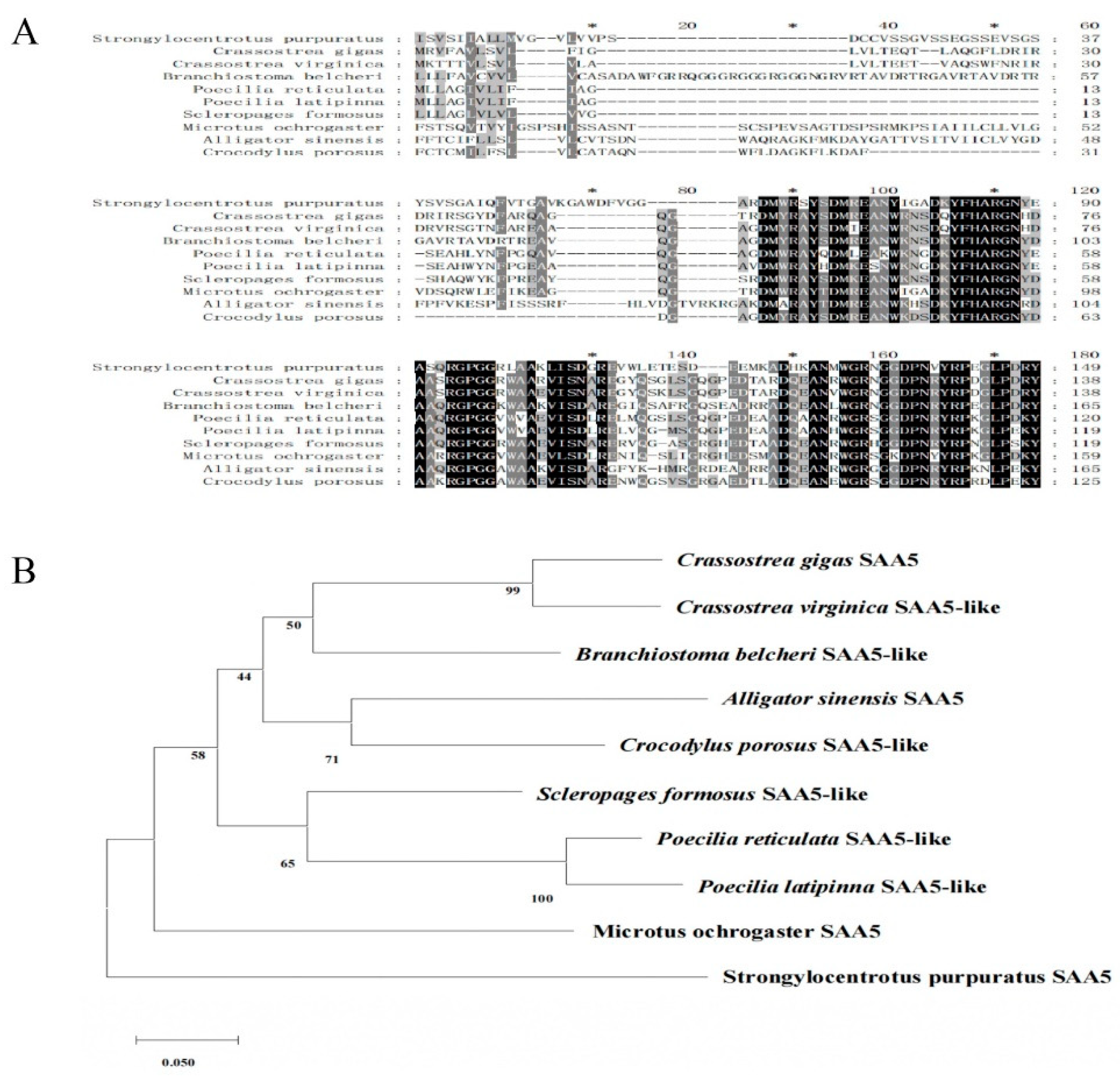

Upon conducting multiple sequence comparisons, it was revealed that the SAA domain of the

CgSAA gene exhibited a significant degree of similarity to those found in both chordates and invertebrates. Notably, the similarity was most pronounced (99%) with respect to that of

Crassostrea virginica (

Figure 2A). For the purpose of phylogenetic analysis, ten SAA-5 sequences from diverse species of vertebrates and invertebrates were chosen,

CgSAA-5 was clustered with

CvSAA-5 from

C. virginica (

Figure 2B).

A: The sequence of ORF and encoded amino acids. The nucleotides and amino acids are numbered along the left margin. The symbol (-) represents a stop codon. The SAA domain is shadowed.

B: Prediction of protein domains by SMART analysis.

A: Multiple sequence alignment analysis of putative domains of CgSAA with other SAA deposited in GenBank, the following are the proteins analyzed: Strongylocentrotus purpuratus (XP_030837042.1), Crassostrea virginica (XP_022321638.1), Branchiostoma belcheri (XP_019623558.1), Poecilia reticulata (XP_008433017.1), Poecilia latipinna (XP_014890824.1), Scleropages Formosus (XP_018618982.1), Microtus ochrogaster (XP_005366816.1), Alligator sinensis (XP_025057901.1), Crocodylus porosus (XP_019407521.1). The identical amino acid residues are shaded in black and the similar amino acid are shaded in grey.

B: Use the MEGA-X software to conduct phylogenetic analysis on CgSAA and other SAA proteins from multiple different species.

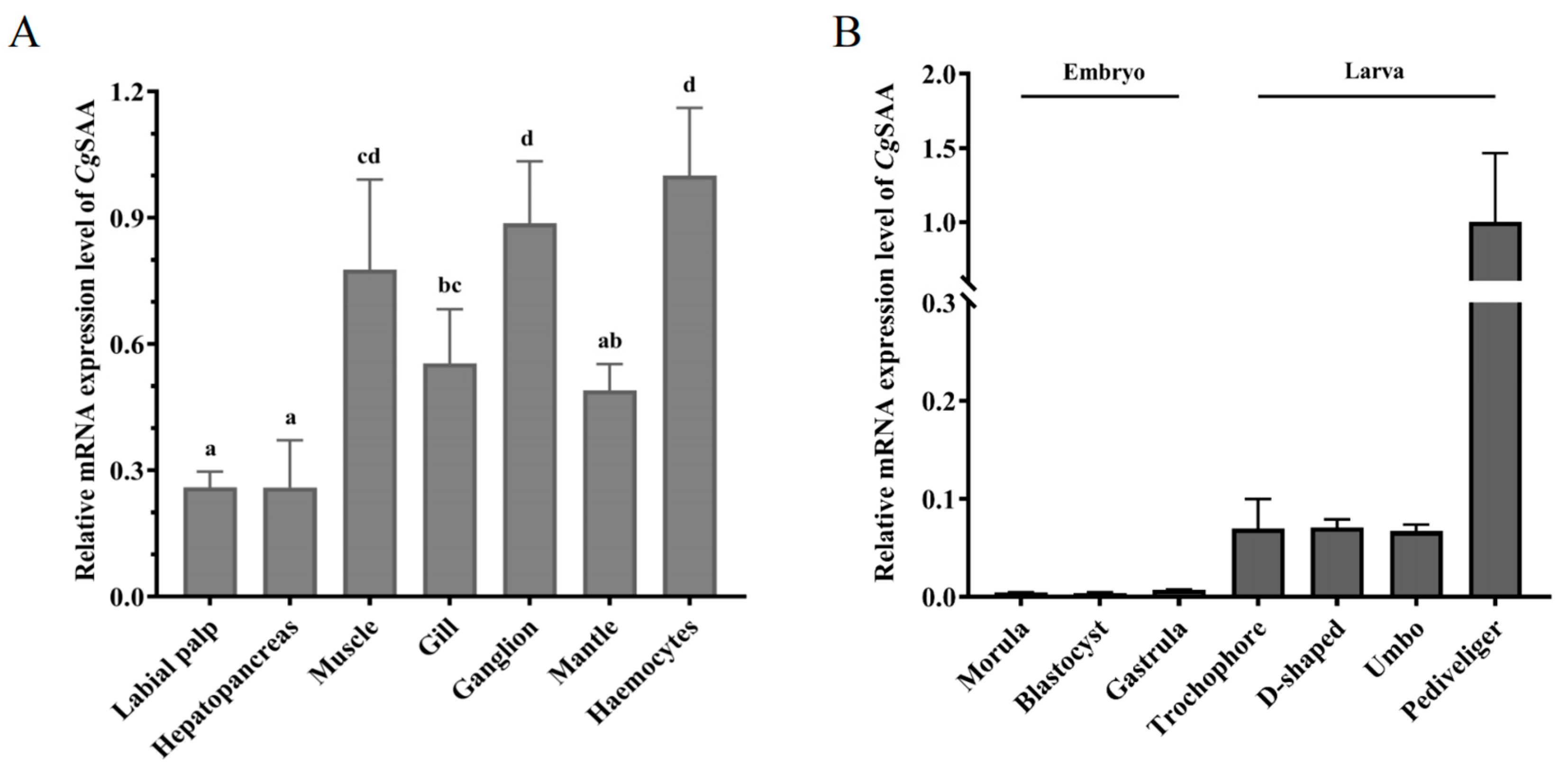

3.2. The Distribution of CgSAA mRNA Transcripts

Analysis of the expression of

CgSAA in different tissues of

Crassostrea gigas. The mRNA expression of

CgSAA in normal individuals was detectable in all the sampled tissues but in low level, including hepatopancreas, mantle, gill, haemocytes, ganglion, adductor muscle and labial palp. In contrastive analysis, the expression level of

CgSAA was detected to be the least in the labial palp. Conversely, haemocytes exhibited a relatively greater expression level of

CgSAA, which was 3.85-fold higher than that in the labial palp (

p < 0.01). It was also higher expressed in ganglions and adductor muscles, which were 3.42-fold (

p < 0.05) and 2.99-fold (

p < 0.05) of that in labial palp, respectively. While relatively lower in gill and mantle, which were 2.14-fold (

p < 0.05), 1.89-fold (

p < 0.05) of labial palp, respectively (

Figure 3A).

During the early developmental process of the oyster

Crassostrea gigas, the expression level of

CgSAA in the larval stage was higher than that in the embryonic stage, and the expression level of

CgSAA was the lowest at the blastula stage. When the embryos of the oyster developed to the trochophore stage, the expression level began to rise, which was 19.11-fold (

p < 0.05) that of the blastula stage. The expression level was the highest at the Pediveliger stage, which was 275.32-fold (

p < 0.05) that of the blastula stage (

Figure 3B).

A: Expression of CgSAA mRNA in different tissues of oyster detected by real-time PCR.

B: The expression levels of CgSAA mRNA in the embryonic and larval stages of the Crassostrea gigas. Data was shown as mean ± S.D (N = 3). Statistically significant differences were designated at p < 0.05. Labial palp, Hepatopancreas, Muscle, Gill, Ganglion, Mantle, Haemocytes.

3.3. The Response of CgSAA in Oyster Under Immune Stimulation or Environmental Stress

The mRNA expressions of

CgSAA in haemocytes were detected at 0, 6, 12 and 24 h after

V. splendidus stimulation. The mRNA expression level of

CgSAA was up-regulated at 6 h (2.76-fold,

p < 0.01), surged at 12 h (7.88-fold,

p < 0.05), and ascended to the peak level at 24 h, which was 21.85-fold (

p < 0.05) higher than that in control group post

V. splendidus stimulation, respectively (

Figure 4A).

After being subjected to high temperature stress (34 ℃), the expression level of

CgSAA in the

Crassostrea gigas remained relatively unchanged in the first 6 h. Then it was significantly unregulated and peaked at 12 h, reaching 21.77-fold (

p < 0.01) of that in the control group, and kept in high level at 24 h (14.6-fold of that in the control group,

p < 0.05) (

Figure 4B). Under hypotonic stress, the expression of

CgSAA in haemocytes was quickly induced, with the highest expression level at 6 h in low salinity group, which was 3.58-fold (

p < 0.01) that of the control group. Then the expression level of

CgSAA decreased sharply with the prolongation of treatment time, and reached the lowest at 24 h (

Figure 4C).

A: The mRNA expression of CgSAA in haemocytes following the stimulation by Vibrio splendidus.

B: The mRNA expression of CgSAA in haemocytes after 34 ℃ seawater treatment.

C: 15‰ salinity seawater treatment. Haemocytes were collected at 0, 6, 12 and 24 h after treatment respectively. Vertical bars represent the mean ± S.D (N = 4). The asterisks (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01) indicate the significant differences.

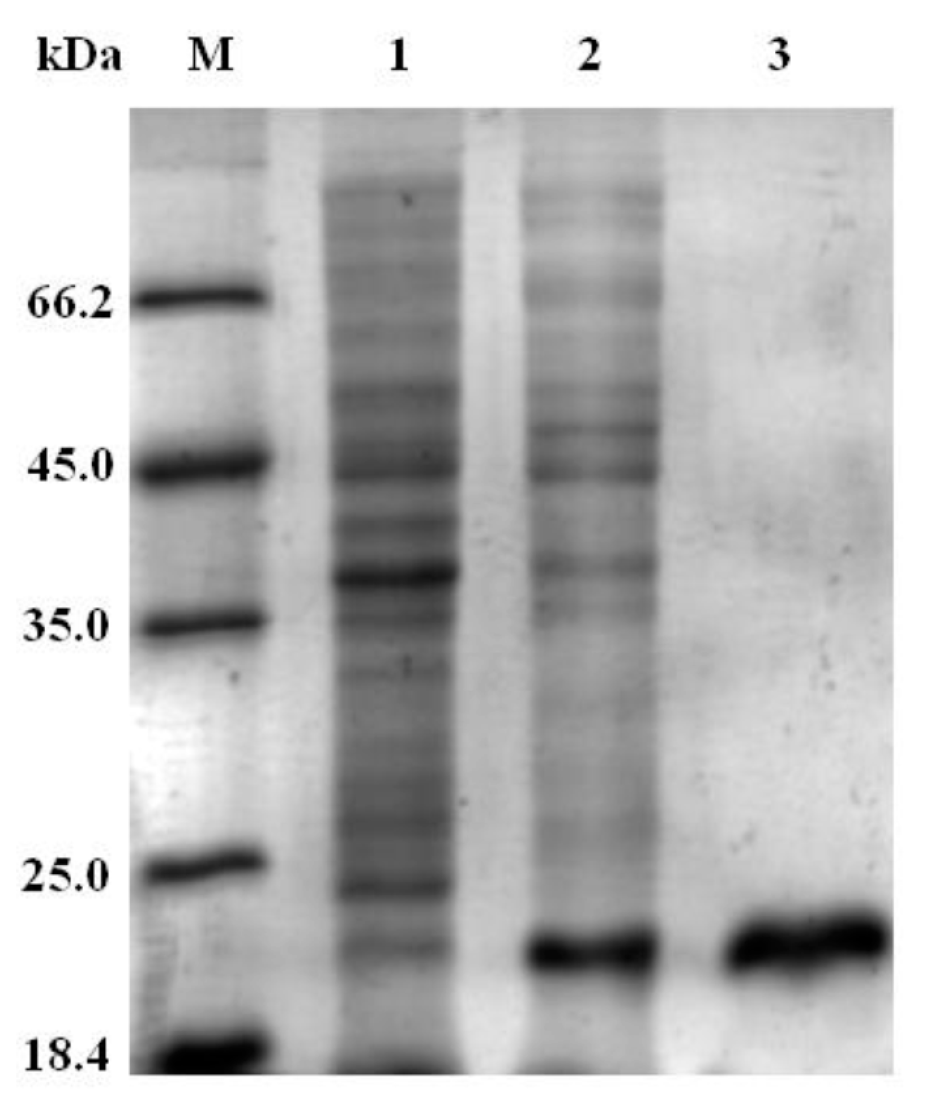

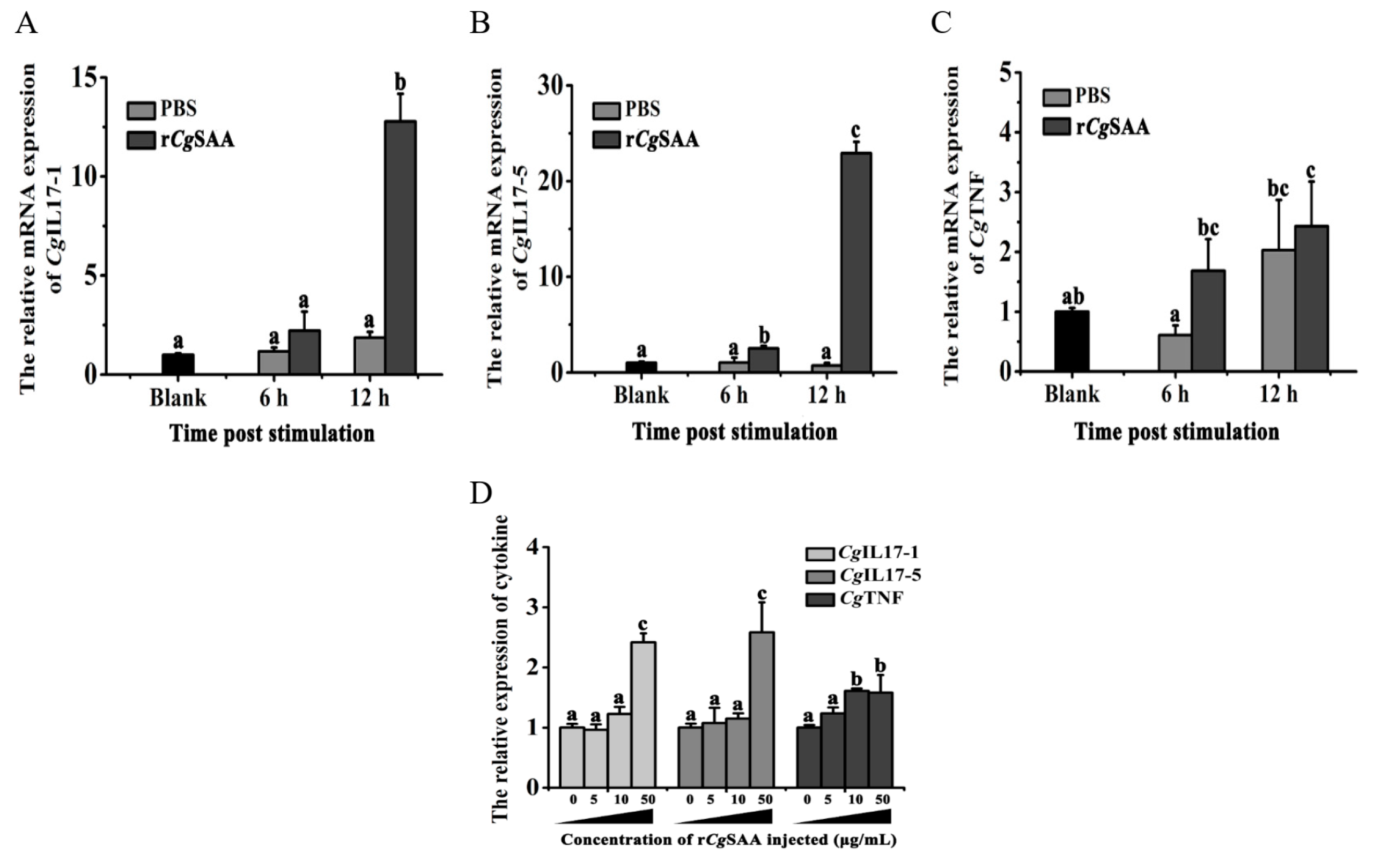

3.4. The Expressions of Cytokines Following Injection of rCgSAA in Oysters

The recombinant protein of

CgSAA (rCgSAA) containing SAA domain was expressed and purified by the CBP-tag Protein Fusion and Purification System. The band with molecular weight of 19.7 kDa was observed (CBP-tag is about 4 kDa), which were consistent with the predicted molecular weight (15.66 kDa) of

CgSAA (

Figure 5). Then the purified r

CgSAA protein was used for oyster injection.

The mRNA expression of cytokine

CgIL17-1, CgIL17-5 and

CgTNF was detected after r

CgSAA injection. The expression level of

CgIL17-1 increased at 6 h after r

CgSAA stimulation and peaked at 12 h, which was 10.29-fold (

p < 0.01) that of that in the control group (

Figure 6A). The relative expression level of

CgIL17-5 was significantly induced at 12 h and 24 h, which were 1.5- and 22.18-fold of that in the control group, respectively,

p < 0.05 (

Figure 6B). Within 12 h after PBS injection, the expression levels of

CgIL17-1 and

CgIL17-5 did not change significantly. The relative expression level of

CgTNF was up-regulated at 6 h and 12 h after r

CgSAA injection, which was 1.64-fold (

p > 0.05) and 2.48-fold (

p < 0.01) higher than that of blank group, respectively (

Figure 6C).

A-C: The expression levels of CgIL17-1, CgIL17-5 and CgTNF in the Crassostrea gigas after treatment with rCgSAA.

D: The expression levels of CgIL17-1, CgIL17-5 and CgTNF in haemocytes after rCgSAA treatment. Vertical bars represent the mean ± S.D. (N = 3). Statistically significant differences were designated at p < 0.05.

3.5. The Expressions of Cytokines in Haemocytes Following Incubation with rCgSAA

To explore how r

CgSAA induce immune response in oyster, the cultured primary haemocytes were incubated with r

CgSAA for 6 h, and expression of

CgIL17-1,

CgIL17-5 and

CgTNF mRNA in haemocytes was validated. When the concentration of r

CgSAA reached 50 μg/mL, it could significantly (

p < 0.01) induce the expression of

CgIL17-1 and

CgIL17-5 in haemocytes, which were 2.48-fold or 2.55-fold that of 0 μg/mL group, respectively, (

Figure 6D). In particular, when the concentration of r

CgSAA reaches 10 μg/mL, the expression level of

CgTNF in haemocytes is significantly enhanced, which is 1.77-fold (

p < 0.05) that of the 0 μg/mL group.

4. Discussion

The acute phase serum amyloid A (SAA), a major acute-phase protein in vertebrates, plays a crucial role in the innate immune response and inflammation. It was isolated and named over 50 years ago and has a striking relationship to the acute phase response with serum levels rising as much as 1000-fold in 24 hours [

8,

15]. SAA proteins are encoded in a family of closely-related genes and have been remarkably conserved throughout vertebrate evolution[

3]. However, the study of SAA in invertebrates is relatively nascent. Thought more and more components of the invertebrate immune system resembling vertebrate counterparts have been discovered, but the presence of SAA has been reported so far in a very limited number of invertebrates, especially in aquatic species. The present study identified the only

saa gene (

CgSAA) from oyster

C. gigas, and its molecular characteristics, expression patter as well as possible functions were further investigated, with the aim to explore the evolution of SAAs and the possible role of

CgSAA in the immune response.

There are varied number of SAA genes in different organisms, and SAA-related proteins and genes constitute a closely-related family. In human, there are 4 SAA genes identified and all of them are clustered on a single chromosome 11p [

2]. In mice, there are 4 functional SAA genes and one pseudogene, which are located in chromosome 7. By genomic and transcriptomic analysis, 51 SAA-like proteins were retrieved in several protostome taxa comprising 21 marine bivalve species and basal metazoans [

7]. Most of these organisms only harbor only one SAA gene. In oyster

C. gigas, only one SAA gene was screened, which was consistent with that in its sister specie

Crassostrea hongkongensis. Invertebrate SAA-like proteins share certain structural features with vertebrate SAA, including a conserved N-terminal region and a variable C-terminal region. These proteins are typically small, with molecular weights ranging from 10 to 20 kDa [

4,

7]. In oyster

C. gigas, the open reading frame of

CgSAA encoded a putative polypeptide of 138 amino acid residues with predicted molecular weight of 15.66 kDa. By structural prediction,

CgSAA was found to contain a signal peptide (residues 1-22) and a structural SAA domain (residues 36-138). Multiple sequence comparisons showed that the SAA domain of the

CgSAA gene shared high similarity with those of chordates and invertebrates, with the highest similarity (99%) to that of

Crassostrea virginica [

9]. Ten SAA-5 from various species of vertebrates and invertebrates were selected for phylogenetic analysis,

CgSAA was clustered with

CvSAA-5 from

C. virginica. These results indicated that

CgSAA was a conserved homolog of SAA family in oyster.

Functional studies have shown that invertebrate SAA-like proteins exhibit similar immune-modulatory activities to vertebrate SAA. In vertebrates, SAA proteins are mainly synthesized in the liver in response to immune challenges, such as bacterial or viral infections and are secreted into the hemolymph or other body fluids [

4]. In invertebrates no specific liver tissue was evolved and developed, and the synthesis of SAA protein was mainly focused on immune-related tissues [

22]. In the present study,

CgSAA was detectable in all the sampled tissues of normal individuals but in low level, with relateive higher level in haemocytes, ganglion and mantle. While in oyster

C. hongkongensis,

ChSAA was lowest expressed in haemocytes but higher expressed in mantle and labial palps [

9]. Though not highly expressed in normal condition, the expression of

CgSAA was quickly un-regulated after immune stimulation, which was similar with that in vertebrates. Living in intertidal environment, oysters always face environmental stresses, such as high temperature and low oxygen [

23]. The mass death caused by high temperature (summary mortality) and continuous rainfall (hypotonic death) has severely dampened the oyster industry, but the mechanism is still not clear [

24]. In the present study, the expression of

CgSAA was quickly un-regulated in oysters cultured under high temperature (34℃) stress or hypotonic stress (15‰). As an acute phase response protein, SAA in human can rise 1000-fold in 24–36 h following the initiating stimulus, which is commonly used as a diagnosing marker of infection or inflammation [

25]. The prompt expression changes of

CgSAA under infection and environmental stresses inferred that it could be used as a sensitive diagnosing marker of oyster disease.

The role of SAA proteins in immune responses is multifaceted. In vertebrates, they can bind to lipoproteins, enhance phagocytosis, and stimulate the production of immune mediators in mammalian [

26]. Some SAA proteins have been shown to exhibit antimicrobial and antiviral activity, directly inhibiting the growth of pathogens. They can also modulate the production of cytokines and other immune mediators, thereby regulating the inflammatory response. While in invertebrates, the role of SAA protein in mediating immune response has not been fully uncovered, and only limited studies reported its expression changes under immune stimulation. In echinoderm, for example, SAA proteins have been shown to be induced in response to LPS stimulation or during intestinal regeneration [

8,

27]. These proteins are secreted into the hemolymph and bind to lipoproteins, forming complexes that are recognized by immune cells. In mollusks

Tridacna crocea, SAA protein has been found to exhibit binding and antimicrobial activity against a range of bacteria pathogens, and could reduce the lethality rate of infected individuals [

10]. In the present study, to explore the potential role of SAA in immune response, the recombinant r

CgSAA was prepared and injected into oysters or incubated with primary cultured haemocytes. The expressions of cytokines including IL17-1, IL17-1 and TNF were all significantly induced after r

CgSAA treatment, indicating the important role of

CgSAA in inflammation. In oyster

C. hongkongensis, the over-expression of

ChSAA via transfection with a

ChSAA expression vector led to significantly increased NF-kB activity in HEK293T cells [

9]. In mammalian, the SAA was also found to display pro-inflammatory effect and could promote synovial macrophage activation and chronic arthritis via NFAT5.

Though the detail mechanism of

CgSAA induced inflammation is still missing, it could be inferred that the NF-kB signal might play a role just as that in oyster

C. hongkongensis. In oyster, the inflammation caused by cytokines including IL17-1, IL17-1 and TNF [

20,

28], plays an important role in mass mortality under stressful environment. Considering the high expression of

CgSAA and serious mortality in oyster under high temperature stress or hypotonic stress, the

CgSAA induced severe inflammation might be the main cause of summary mortality in oyster industry. The discovery of SAA function in oyster has opened up new possibilities for the development of disease-resistant strains and biotechnology applications.