1. Introduction

The spaciotemporal control of gene expression is regulated by promoters and enhancers. Enhancers are non-coding regions located outside the promoter region, are bound by transcription factors, and interact with the promoter to regulate transcription [

1]. Candidate enhancers active in a given cell type may be identified by histone modifications, including H3K27ac, H3K4me1, and H3K4me2, and histone variants, such as H2A.Z [

2]. The spaciotemporal control of transcription by enhancers has been examined in vivo using reporter systems [

3].

In

Drosophila, two or more redundant (or shadow) enhancers, which control the same gene and drive identical or overlapping expression patterns, are present in many genes [

4]. Shadow enhancers have been also identified in

Caenorhabditis elegans, zebrafish, mice, and humans, and are associated with most developmental genes [

5]. Shadow enhancers were previously shown to be functionally redundant because the deletion of individual enhancers showed no phenotype, whereas that of pairs of enhancers resulted in discernible phenotypes [

3]. Furthermore, shadow enhancers were found to function additively, synergistically, or redundantly [

1]. The overlapping activity of shadow enhancers may have important functions, including phenotypic robustness in the face of environmental and genetic variability, buffering upstream noise through the separation of transcription factor inputs at individual enhancers, and generating more precise expression patterns [

3,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10].

Runx2 is an essential transcription factor for osteoblast differentiation and chondrocyte maturation [

11]. It is expressed in all osteoblast lineage cells. Runx2 induces the commitment of multipotent mesenchymal cells to osteoblast lineage cells, the proliferation of osteoprogenitors, the differentiation of committed osteoblasts to mature osteoblasts, and the expression of major bone matrix protein genes [

11]. Runx2 is also expressed in chondrocytes, and its expression is up-regulated in prehypertrophic chondrocytes in the growth plate and maintained in hypertrophic chondrocytes. Runx2 induces chondrocyte maturation and enhances their proliferation by inducing Indian hedgehog (Ihh) in prehypertrophic chondrocytes [

11].

The transcription of Runx2 is regulated by two promoters, P1 and P2. Mice with the deletion of the P1 promoter showed delayed skeletal development and severe osteopenia, indicating that transcripts from the P1 promoter play important roles in Runx2-dependent skeletal development [

12,

13]. The transcriptional regulation of Runx2 has been examined in the P1 promoter [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. However, reporter mice under the control of the P1 promoter failed to recapitulate Runx2 expression in osteoblasts and chondrocytes [

20,

21]. We previously described a 1.3-kb osteoblast-specific Runx2 enhancer that directed reporter EGFP expression specifically to osteoblasts, and showed that 343 bp was sufficient for osteoblast-specific expression. The enhancer was activated by Tcf7, Ctnnb1, Mef2c, Smad1, Sox5/6, Dlx5/6, and Sp7, and formed an enhanceosome in the core 89 bp. Mef2c and Dlx5/6 directly bound to the 89 bp, and the other proteins indirectly bound to it by protein-protein interactions [

21].

A 0.8-kb region with homologous sequences has been identified between the 1.3-kb enhancer and P1 promoter in many species. We examined the enhancer activity of the 0.8-kb region. Although it did not exhibit enhancer activity, the osteoblast-specific 1.3-kb enhancer combined with the 0.8-kb region in reporter mice induced reporter gene expression in chondrocytes in a similar expression pattern to Runx2.

3. Discussion

In mesoderm development in

Drosophila, 64% of loci were found to have shadow enhancers, indicating their pervasiveness throughout the genome [

9]. Many shadow enhancers have an overlapping spaciotemporal expression pattern and exhibit activity to acquire the necessary level of expression that ensures phenotypic robustness or a faithful expression pattern or to maintain a low level of expression noise against genetic perturbations and environmental stresses, such as variations in temperature [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

22]. In mice,

Ihh, which is required for skeletal development, is regulated by at least nine enhancers [

10]. They have individual expression specificities with some overlap in the digit anlagen, growth plates, skull sutures, and fingertips. Sequential deletions of these enhancers resulted in more severe growth defects of the skull and long bones, indicating that these enhancers function in an additive manner. The pervasive presence of multiple enhancers was also observed at seven distinct loci required for limb development [

3]. Although the single deletion of each of the ten enhancers, which had individual expression patterns with overlap, did not show phenotypes, the deletion of pairs of limb enhancers near the same gene caused phenotypes, indicating that these enhancers function redundantly in limb development. Furthermore, single enhancer deletions showed phenotypes in heterozygous mutant mice of the target gene, indicating that redundant enhancers function additively. These shadow or redundant enhancers in

Drosophila and mice have individual expression patterns with overlap and function additively to ensure phenotypic robustness or a faithful expression pattern.

Although the histone of the 0.8-kb region was modified similar to an enhancer, 0.8-kb DNA fragment did not exhibit enhancer activity in vitro. However, the four tandem repeats of 452 bp (452×4), the core homologous region of 0.8 kb, exhibited enhancer activity specifically in chondrocyte cell lines, but virtually no activity in chondrocytes in vivo. When 452×4 was combined with the 1.3-kb osteoblast-specific enhancer in EGFP reporter mice, EGFP expression was detected in osteoblasts and hypertrophic chondrocytes. Therefore, the 0.8-kb region was not an enhancer, it appeared to be a subenhancer that does not exhibit sufficient activity as an enhancer, but acquires enhancer activity when combined with an enhancer. In contrast to previous findings on enhancers, the 1.3-kb osteoblast-specific enhancer and 0.8-kb region did not show any overlapping expression pattern individually and did not function additively to induce expression in osteoblasts, but induced expression in a different lineage cell, chondrocytes. This is the first study to report a subenhancer and show a new model of cooperation between two regulatory elements, namely, an enhancer and subenhancer.

Runx2 expression is low in the growth plate of the resting chondrocyte layer, is up-regulated from the proliferating chondrocyte layer to the prehypertrophic chondrocyte layer, and high expression is maintained in the hypertrophic chondrocyte layer (Supplementary figure S3). The expression pattern of EGFP in the growth plate of femurs was closer to that of Runx2 in reporter mice using the 1.3-kb enhancer and 0.8-kb region than in those using the 1.3-kb enhancer and 452×4 (Figs. 5-7). Mef2c is required for chondrocyte maturation, and its expression pattern is similar to that of Runx2 in the growth plate [

23]. There are two Mef2c-binding motifs in the 0.8-kb region (Supplementary figure S2A). Since they are located in a less conserved region, this region was not included in 452 bp. Although the 0.8-kb luciferase vector had virtually no reporter activity in vitro, the introduction of

Mef2c strongly induced its reporter activity in SW1353 cells (

Figure 2C, Supplementary figure S2B). The 1.3-kb enhancer had one conserved Mef2c motif, which was bound by Mef2c, in the 343-bp core region, and Mef2c was required for enhancer activity [

21]. Reporter mice using the 343-bp region showed osteoblast-specific expression and EGFP expression was absent in chondrocytes [

21]. However, reporter mice using four tandem repeats of 89 bp, which is the most conserved region in 343 bp and contains the Mef2c motif, showed EGFP expression in both osteoblasts and chondrocytes, and the expression pattern in the growth plate was similar to that of Runx2 [

21]. These findings suggest that the presence of multiple Mef2c motifs directed EGFP expression in the growth plate to a similar pattern as that of Runx2, implying an important role for Mef2c in Runx2 expression in the growth plate.

Although the deletion of the 1.3-kb region or of both the 1.3-kb and 0.8-kb regions showed no apparent phenotype, Runx2 expression was slightly reduced in the limbs by the deletion of both the 1.3-kb and 0.8-kb regions. However, the extent of this reduction was not sufficient to show phenotypes, even in the background of Runx2 haplodeficiency. Therefore, Runx2 expression is also regulated by multiple enhancers with redundant functions, similar to other developmental genes.

In conclusion, we herein revealed that cooperation between an osteoblast-specific enhancer and neighboring subenhancer induced expression in chondrocytes. ChIP- and assay for transposase-accessible chromatin (ATAC)- sequencing recently revealed many enhancer candidates, the activities and physiological functions of which need to be examined in vivo. However, regions with low or no enhancer activity in vivo may have physiological functions in cooperation with other enhancers. Since Runx2 is an essential transcription factor for skeletal development, further studies on transcriptional regulation by enhancers is extremely important for obtaining a more detailed understanding of the process of skeletal development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.K.; Methodology, Y.M., X.Q., T.M, V.K.S. K.-M.; Validation, Y.M., X.Q., V.K.S. K.-M.; Formal analysis, Y.M., X.Q., V.K.S. K.-M.; Investigation, Y.M., X.Q., T.M, V.K.S.K.-M., H. Komori, C.S., S.Y., Q.J., H. Kaneko, M.S., T.A.; Resources, K.I.; Data Curation, Y.M., X.Q., T.M, V.K.S.K.-M.; Writing-Original Draft preparation, Y.M. and T.K., Writing-Review & Editing, T.K.; Project Administration, T.K.; Funding Acquisition, Y.M., X.Q., T.M, V.K.S.K.-M., H. Komori, C.S., S.Y., T.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

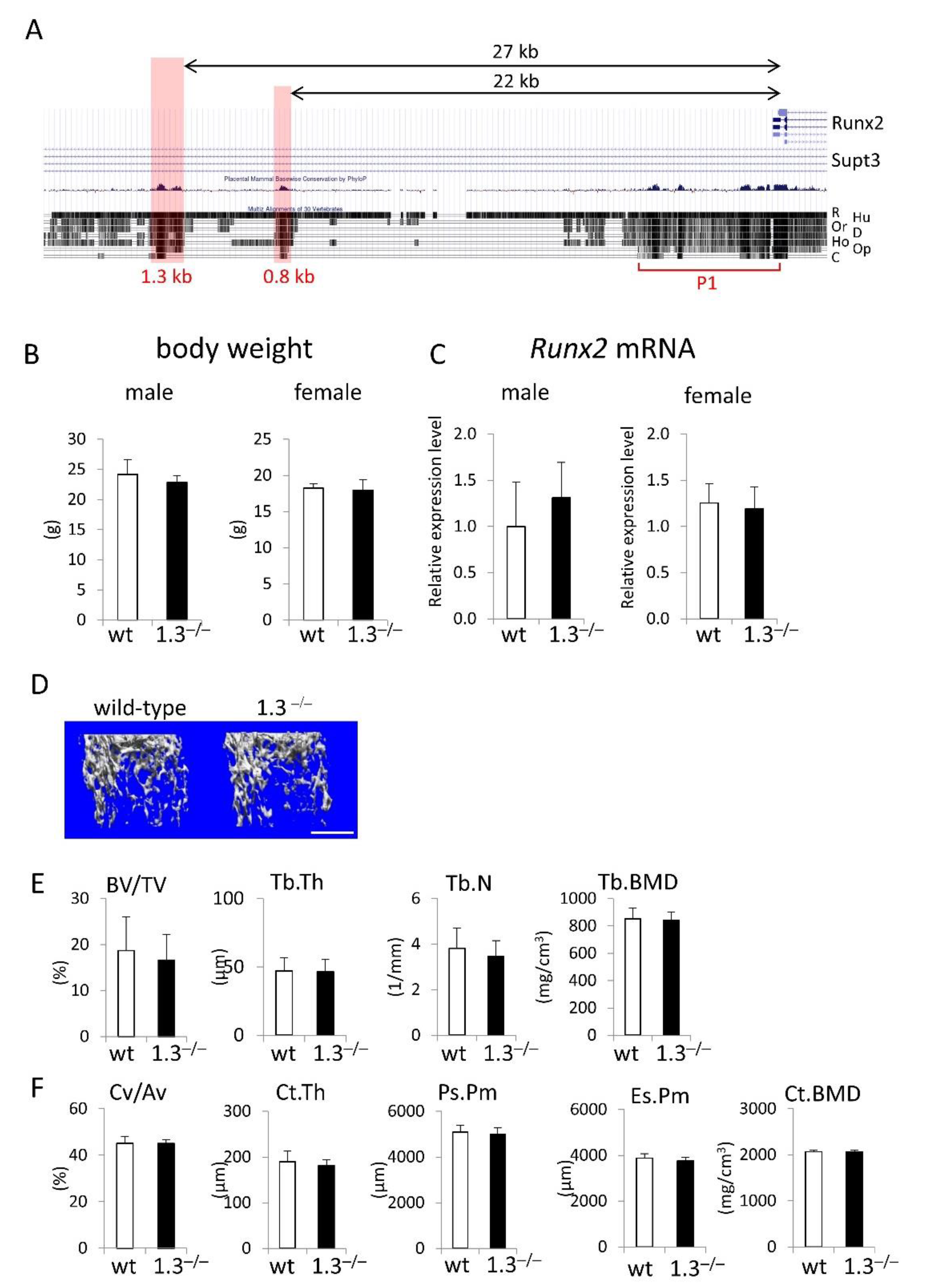

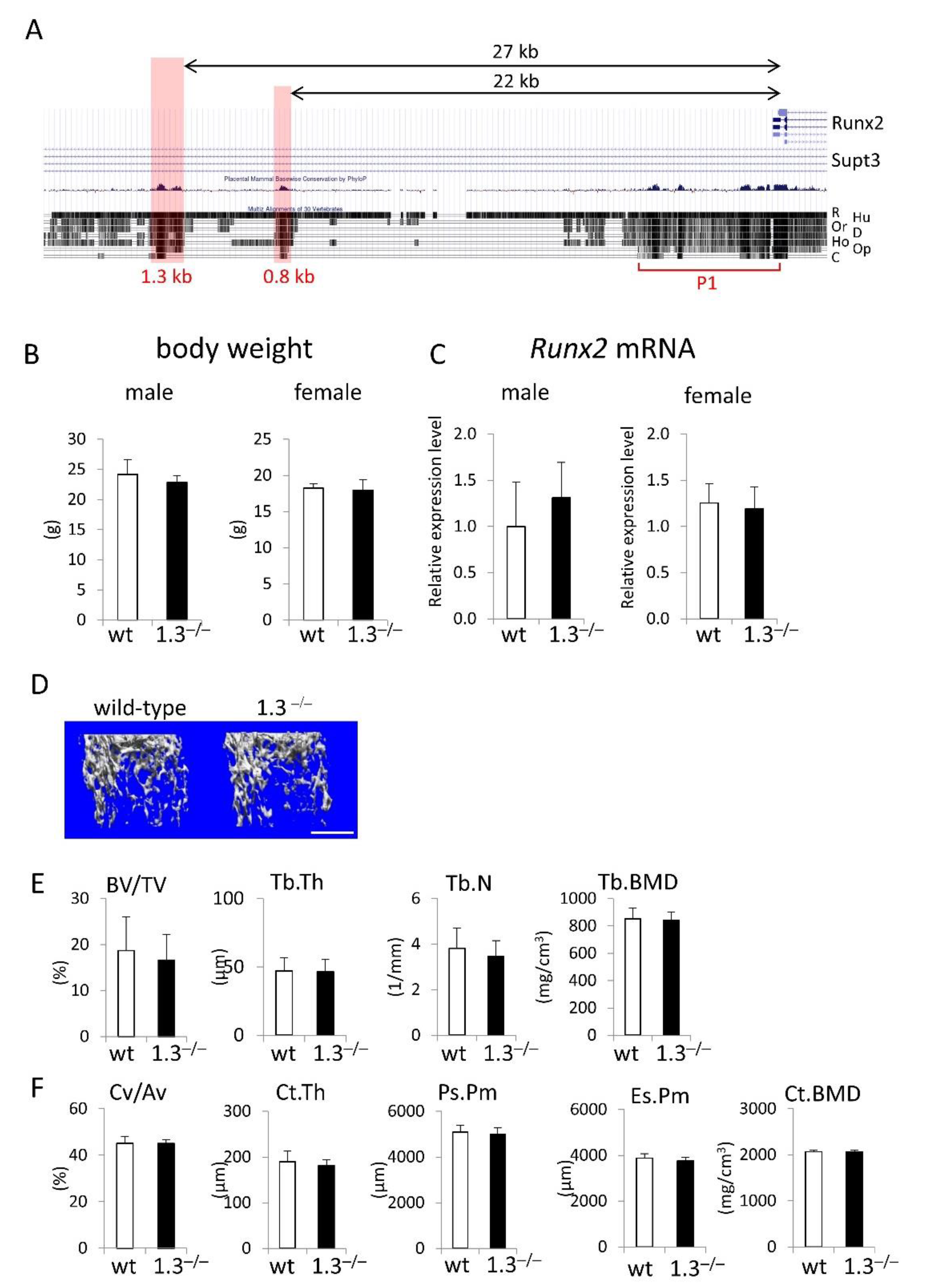

Figure 1.

Phenotypes of 1.3-kb enhancer deletion mice at 10 weeks of age. (A) UCSC Genome Browser screenshot showing homology against the mouse sequence in the upstream region of exon 1 of Runx2. R: rat, Hu: human, Or: orangutan, D: dog, Ho: horse, Op: opossum, C: chicken. The locations of the 1.3-kb, 0.8-kb, and Runx2 P1 promoter (P1) regions are shown. (B) Body weights and (C) tibial Runx2 mRNA expression in wild-type (wt) and 1.3–/– mice. (D-F) Micro-CT analysis of femurs in male wild-type and 1.3–/– mice. (D) Three-dimensional trabecular bone architecture of distal femoral metaphysis. (E) Quantification of the trabecular bone volume (bone volume/tissue volume, BV/TV), trabecular thickness (Tb.Th), trabecular number (Tb.N), and trabecular bone mineral density (Tb.BMD). (F) Quantification of the cortical bone ratio (cortical bone volume/all bone volume, Cv/Av), cortical thickness (Ct.Th), periosteal perimeter (Ps.Pm), endosteal perimeter (Es.Pm), and cortical bone mineral density (Ct.BMD). The number of mice analyzed: male wild-type, n=6; 1.3–/–, n=7-8; female wild-type, n=7-8, 1.3–/–, n=12-13 in B and C, and wild-type, n=6; 1.3–/–, n=8 in E and F. Scale bar: 1 mm.

Figure 1.

Phenotypes of 1.3-kb enhancer deletion mice at 10 weeks of age. (A) UCSC Genome Browser screenshot showing homology against the mouse sequence in the upstream region of exon 1 of Runx2. R: rat, Hu: human, Or: orangutan, D: dog, Ho: horse, Op: opossum, C: chicken. The locations of the 1.3-kb, 0.8-kb, and Runx2 P1 promoter (P1) regions are shown. (B) Body weights and (C) tibial Runx2 mRNA expression in wild-type (wt) and 1.3–/– mice. (D-F) Micro-CT analysis of femurs in male wild-type and 1.3–/– mice. (D) Three-dimensional trabecular bone architecture of distal femoral metaphysis. (E) Quantification of the trabecular bone volume (bone volume/tissue volume, BV/TV), trabecular thickness (Tb.Th), trabecular number (Tb.N), and trabecular bone mineral density (Tb.BMD). (F) Quantification of the cortical bone ratio (cortical bone volume/all bone volume, Cv/Av), cortical thickness (Ct.Th), periosteal perimeter (Ps.Pm), endosteal perimeter (Es.Pm), and cortical bone mineral density (Ct.BMD). The number of mice analyzed: male wild-type, n=6; 1.3–/–, n=7-8; female wild-type, n=7-8, 1.3–/–, n=12-13 in B and C, and wild-type, n=6; 1.3–/–, n=8 in E and F. Scale bar: 1 mm.

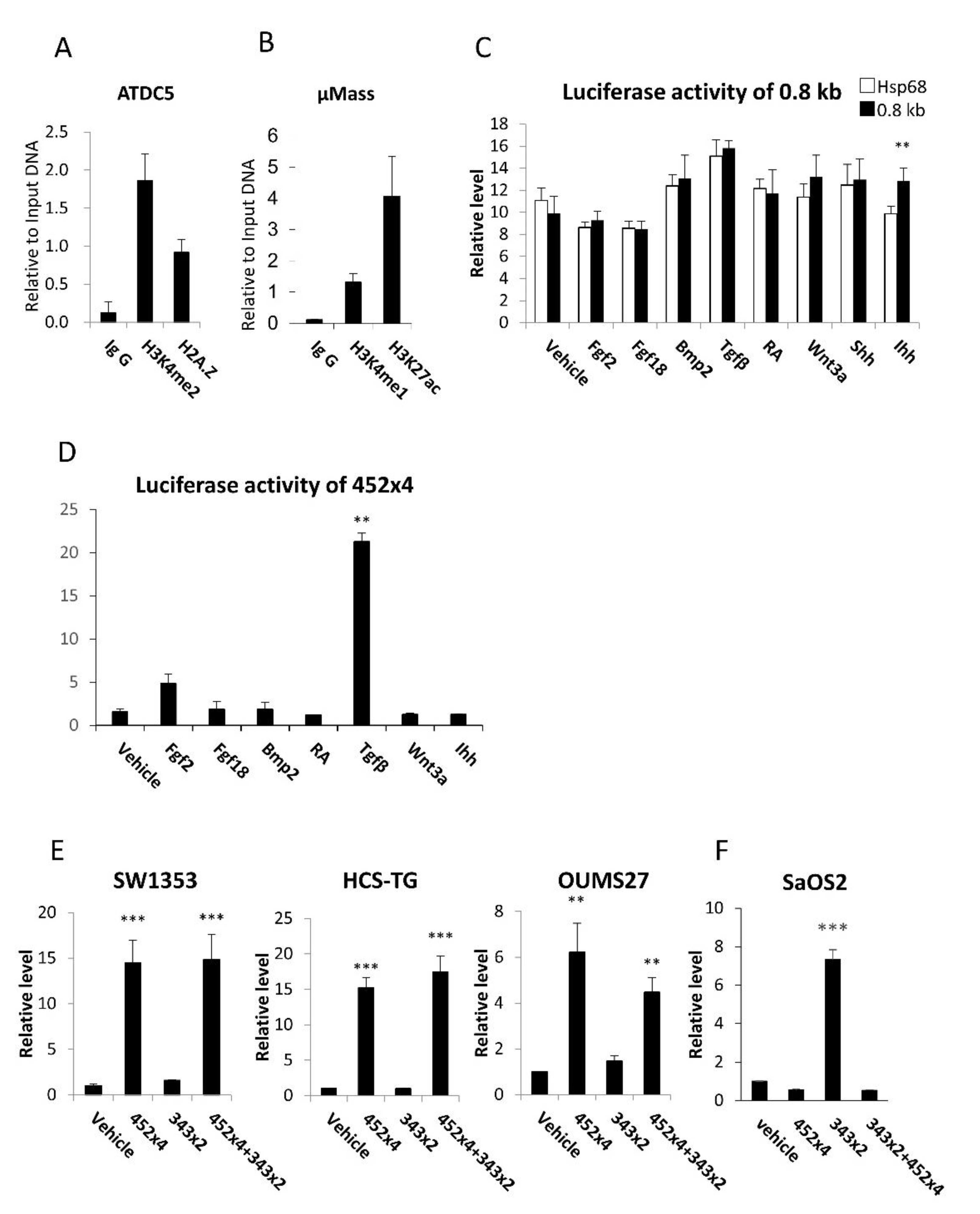

Figure 2.

ChIP analysis of the 0.8-kb region and reporter assays of the 0.8-kb DNA and 452x4. (A, B) ChIP analysis of ATDC5 cells (A) and a micromass culture of primary chondrocytes (B). Antibodies against H3K4me2 and H2A.Z (A) and H3K4me1 and H3K27ac (B) were used for immunoprecipitation. (C-F) Reporter assays. Induction of the reporter activity of the 0.8-kb luciferase vector in ATDC5 cells (C) and the 454×4 luciferase vector in SW1353 cells (D) by various factors. RA: Retinoic acid. Reporter activity of the 452×4, 343×2, and 452×4+343×2 luciferase vectors in chondrocyte cell lines (E) and in the osteoblast cell line (F). Data are the mean ± SE. * Versus Hsp68 in C and versus vehicle in D-F, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001. Similar results were obtained from two independent experiments (C, D) and three to five independent experiments (E, F), and representative data are shown.

Figure 2.

ChIP analysis of the 0.8-kb region and reporter assays of the 0.8-kb DNA and 452x4. (A, B) ChIP analysis of ATDC5 cells (A) and a micromass culture of primary chondrocytes (B). Antibodies against H3K4me2 and H2A.Z (A) and H3K4me1 and H3K27ac (B) were used for immunoprecipitation. (C-F) Reporter assays. Induction of the reporter activity of the 0.8-kb luciferase vector in ATDC5 cells (C) and the 454×4 luciferase vector in SW1353 cells (D) by various factors. RA: Retinoic acid. Reporter activity of the 452×4, 343×2, and 452×4+343×2 luciferase vectors in chondrocyte cell lines (E) and in the osteoblast cell line (F). Data are the mean ± SE. * Versus Hsp68 in C and versus vehicle in D-F, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001. Similar results were obtained from two independent experiments (C, D) and three to five independent experiments (E, F), and representative data are shown.

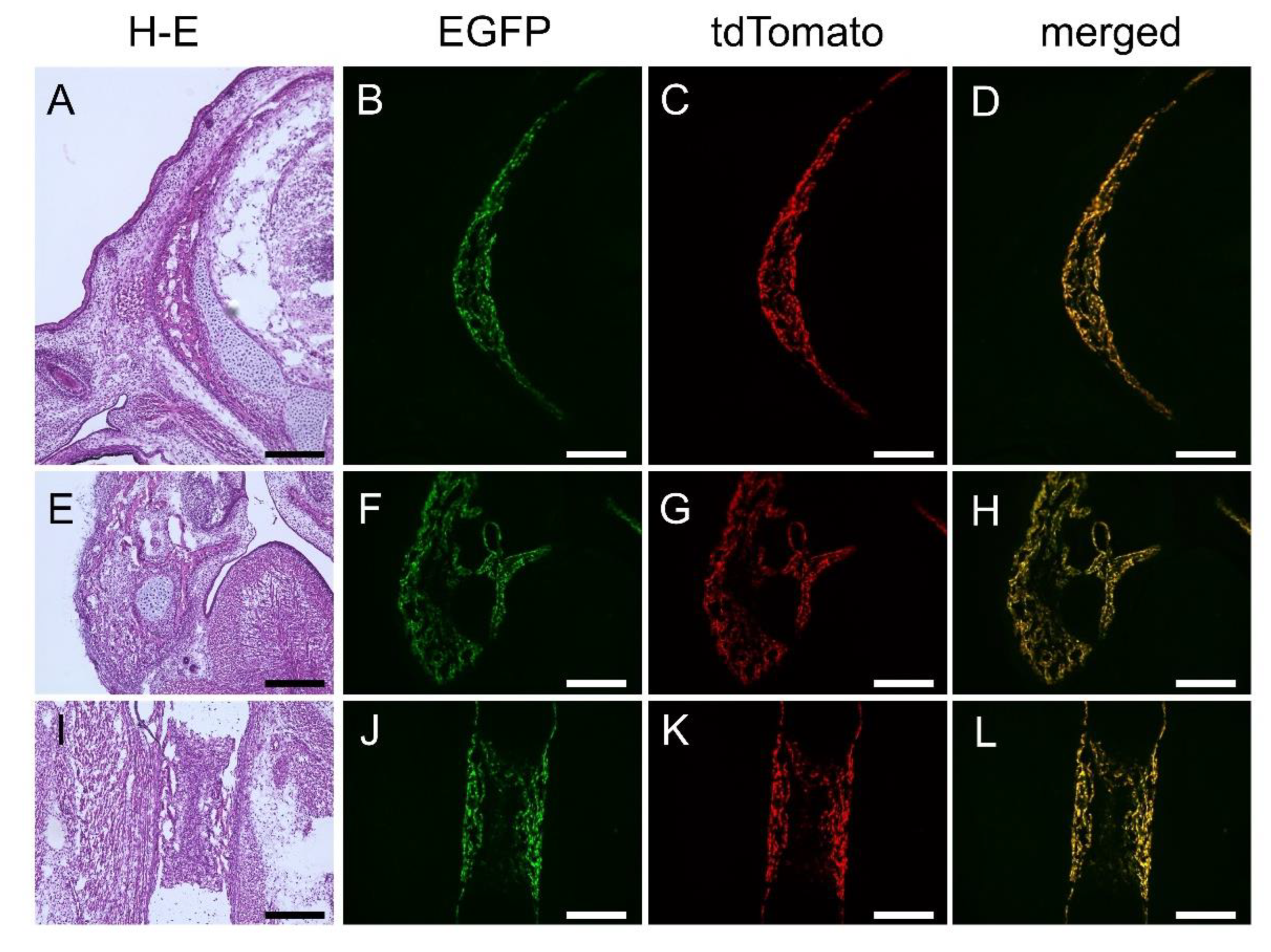

Figure 3.

Reporter gene expression in 1.3-kb enhancer-EGFP and Col1a1-tdTomato double transgenic mice at E16.5. Frozen sections of the head (A-D), mandible (E-H), and femur (I-L). (A, E, I) H-E staining. (B, F, J) EGFP expression. (C, G, K) tdTomato expression. (D, H, L) Merged pictures of EGFP and tdTomato expression. Scale bar: 200 μm.

Figure 3.

Reporter gene expression in 1.3-kb enhancer-EGFP and Col1a1-tdTomato double transgenic mice at E16.5. Frozen sections of the head (A-D), mandible (E-H), and femur (I-L). (A, E, I) H-E staining. (B, F, J) EGFP expression. (C, G, K) tdTomato expression. (D, H, L) Merged pictures of EGFP and tdTomato expression. Scale bar: 200 μm.

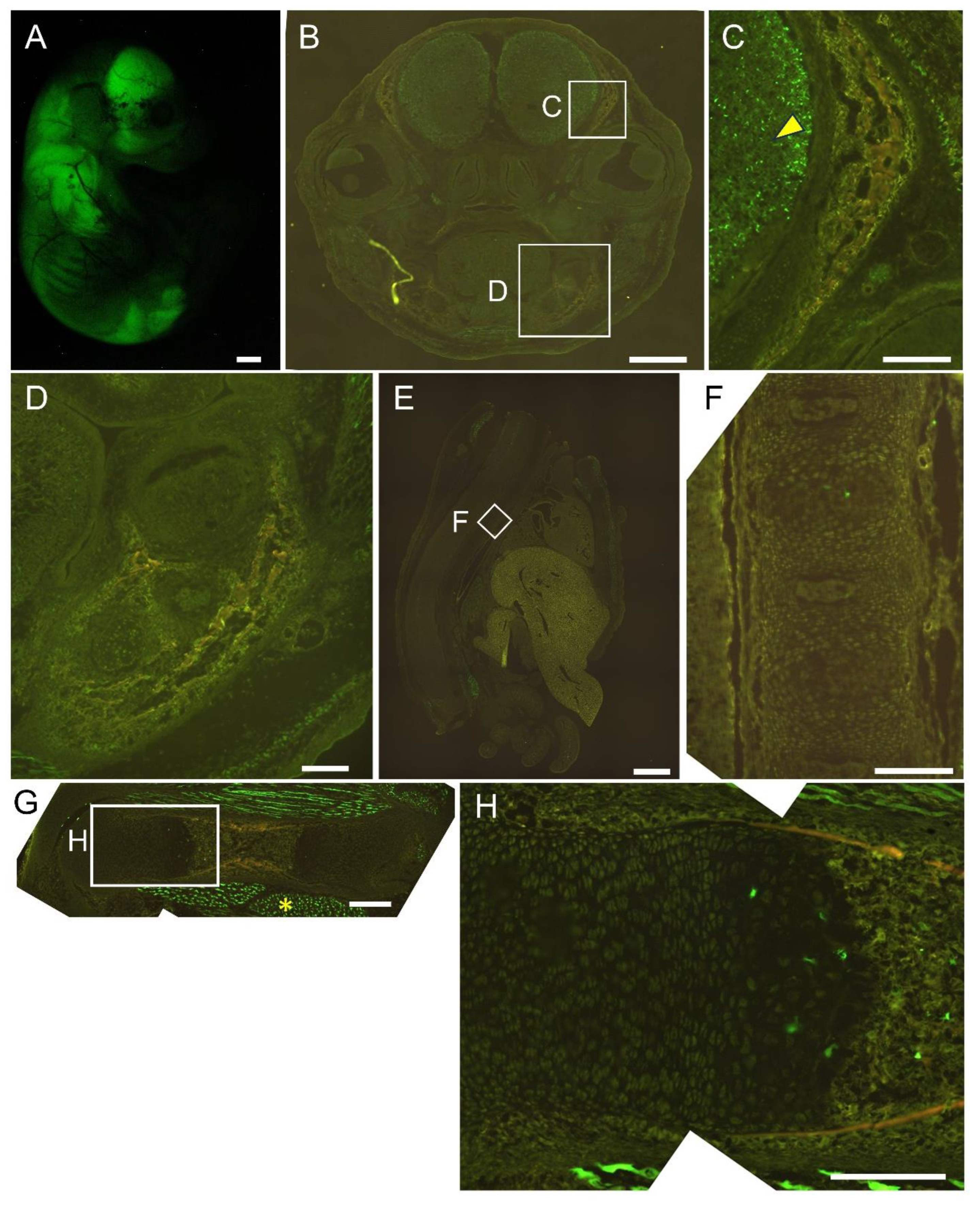

Figure 4.

Reporter gene expression of 452×4-EGFP mice at E16.5. Appearance (A) and frozen sections of the head (B, C), mandible (D), vertebrae (E, F), and femur (G, H). The boxed regions in B, E, and G are magnified in C and D, F, and H, respectively. Arrowhead in C shows brain, and asterisk in G shows muscle. Scale bar: 1 mm (A, B, E), 200 μm (C, D, F, G, H). Three out of three F0 transgenic mice analyzed showed a similar expression pattern and a representative F0 mouse is shown.

Figure 4.

Reporter gene expression of 452×4-EGFP mice at E16.5. Appearance (A) and frozen sections of the head (B, C), mandible (D), vertebrae (E, F), and femur (G, H). The boxed regions in B, E, and G are magnified in C and D, F, and H, respectively. Arrowhead in C shows brain, and asterisk in G shows muscle. Scale bar: 1 mm (A, B, E), 200 μm (C, D, F, G, H). Three out of three F0 transgenic mice analyzed showed a similar expression pattern and a representative F0 mouse is shown.

Figure 5.

Reporter gene expression of 1.3 kb+452×4-EGFP mice at E16.5. Appearance (A) and frozen sections of the head (B, C), mandible (D), vertebrae (E, F), and femur (G, H). The boxed regions in B, E, and G are magnified in C and D, F, and H, respectively. Arrowhead in C shows brain, and asterisk in G shows muscle. Scale bar: 1 mm (A, B, E), 200 μm (C, D, F, G, H). Three out of five F0 transgenic mice analyzed showed a similar expression pattern and a representative F0 mouse is shown.

Figure 5.

Reporter gene expression of 1.3 kb+452×4-EGFP mice at E16.5. Appearance (A) and frozen sections of the head (B, C), mandible (D), vertebrae (E, F), and femur (G, H). The boxed regions in B, E, and G are magnified in C and D, F, and H, respectively. Arrowhead in C shows brain, and asterisk in G shows muscle. Scale bar: 1 mm (A, B, E), 200 μm (C, D, F, G, H). Three out of five F0 transgenic mice analyzed showed a similar expression pattern and a representative F0 mouse is shown.

Figure 6.

Reporter gene expression of the 1.3 kb+452×4-EGFP mice at E15.5. Appearance (A) and frozen section of head (B, C), mandible (D), vertebrae (E, F) and femur (G, H). The boxed regions in B, E and G are magnified in C and D, F and H, respectively. Arrowhead in C shows brain, and asterisk in G shows muscle. The empty spaces (arrows in G and H) between the growth plate and bone marrow were generated by artificial breaks in sectioning. Scale bar: 1 mm (A, B, E), 200 μm (C, D, F, G, H). Two out of two F0 transgenic mice analyzed showed a similar expression pattern and a representative F0 mouse is shown.

Figure 6.

Reporter gene expression of the 1.3 kb+452×4-EGFP mice at E15.5. Appearance (A) and frozen section of head (B, C), mandible (D), vertebrae (E, F) and femur (G, H). The boxed regions in B, E and G are magnified in C and D, F and H, respectively. Arrowhead in C shows brain, and asterisk in G shows muscle. The empty spaces (arrows in G and H) between the growth plate and bone marrow were generated by artificial breaks in sectioning. Scale bar: 1 mm (A, B, E), 200 μm (C, D, F, G, H). Two out of two F0 transgenic mice analyzed showed a similar expression pattern and a representative F0 mouse is shown.

Figure 7.

Reporter gene expression of 1.3 kb+0.8 kb-EGFP mice at E16.5. Appearance (A) and frozen sections of the head (B, C), mandible (D), vertebrae (E, F), and femur (G, H). The boxed regions in B, E, and G are magnified in C and D, F, and H, respectively. Arrowhead in C shows brain, and asterisk in G shows muscle. Scale bar: 1 mm (A, B, E), 200 μm (C, D, F, G, H). Three out of four F0 transgenic mice analyzed showed a similar expression pattern and a representative F0 mouse is shown.

Figure 7.

Reporter gene expression of 1.3 kb+0.8 kb-EGFP mice at E16.5. Appearance (A) and frozen sections of the head (B, C), mandible (D), vertebrae (E, F), and femur (G, H). The boxed regions in B, E, and G are magnified in C and D, F, and H, respectively. Arrowhead in C shows brain, and asterisk in G shows muscle. Scale bar: 1 mm (A, B, E), 200 μm (C, D, F, G, H). Three out of four F0 transgenic mice analyzed showed a similar expression pattern and a representative F0 mouse is shown.

Figure 8.

Phenotypes of 1.3-kb and 0.8-kb deletion (1.3;0.8–/–) mice and 1.3;0.8+/–/Runx2+/– mice. (A-E) Analysis of 1.3;0.8–/– mice. Runx2 mRNA levels in the calvaria and limbs of wild-type and 1.3;0.8–/– newborn mice (A), H-E staining of femoral sections of E15.5 embryos (B, C), the length of bone marrow in femurs at E15.5 (D), and the length of femurs at P1 (E). (F-M) Analysis of 1.3;0.8+/–/Runx2+/– mice. Skeletal preparations of wild-type, Runx2+/–, and 1.3;0.8+/–/Runx2+/– embryos at E15.5 (F) and E18.5 (G), and H-E staining of femoral sections of E15.5 embryos (H-M). The boxed regions in H-J are magnified in K-M, respectively. The number of mice analyzed: (A) wild-type n=11, 1.3;0.8–/– n=10; (D) n=3-4; (E) n=3. Skeletal preparations at E15.5 (n=3-4) and E18.5 (n=4-6) were examined, and the representatives are shown in F and G. Scale bar: 100 μm (B, C, K-M), 200 μm (H-J), 5 mm (F, G). Data are the mean ± SD. *Versus wild-type, *p<0.05.

Figure 8.

Phenotypes of 1.3-kb and 0.8-kb deletion (1.3;0.8–/–) mice and 1.3;0.8+/–/Runx2+/– mice. (A-E) Analysis of 1.3;0.8–/– mice. Runx2 mRNA levels in the calvaria and limbs of wild-type and 1.3;0.8–/– newborn mice (A), H-E staining of femoral sections of E15.5 embryos (B, C), the length of bone marrow in femurs at E15.5 (D), and the length of femurs at P1 (E). (F-M) Analysis of 1.3;0.8+/–/Runx2+/– mice. Skeletal preparations of wild-type, Runx2+/–, and 1.3;0.8+/–/Runx2+/– embryos at E15.5 (F) and E18.5 (G), and H-E staining of femoral sections of E15.5 embryos (H-M). The boxed regions in H-J are magnified in K-M, respectively. The number of mice analyzed: (A) wild-type n=11, 1.3;0.8–/– n=10; (D) n=3-4; (E) n=3. Skeletal preparations at E15.5 (n=3-4) and E18.5 (n=4-6) were examined, and the representatives are shown in F and G. Scale bar: 100 μm (B, C, K-M), 200 μm (H-J), 5 mm (F, G). Data are the mean ± SD. *Versus wild-type, *p<0.05.