Submitted:

27 December 2024

Posted:

30 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Rule-Based Methods

2.2. Statistical Feature-Based Methods

2.3. Machine Learning-Based Methods

2.4. Deep Learning-Based Methods

2.5. Semi-Supervised Learning Methods

3. Methodology

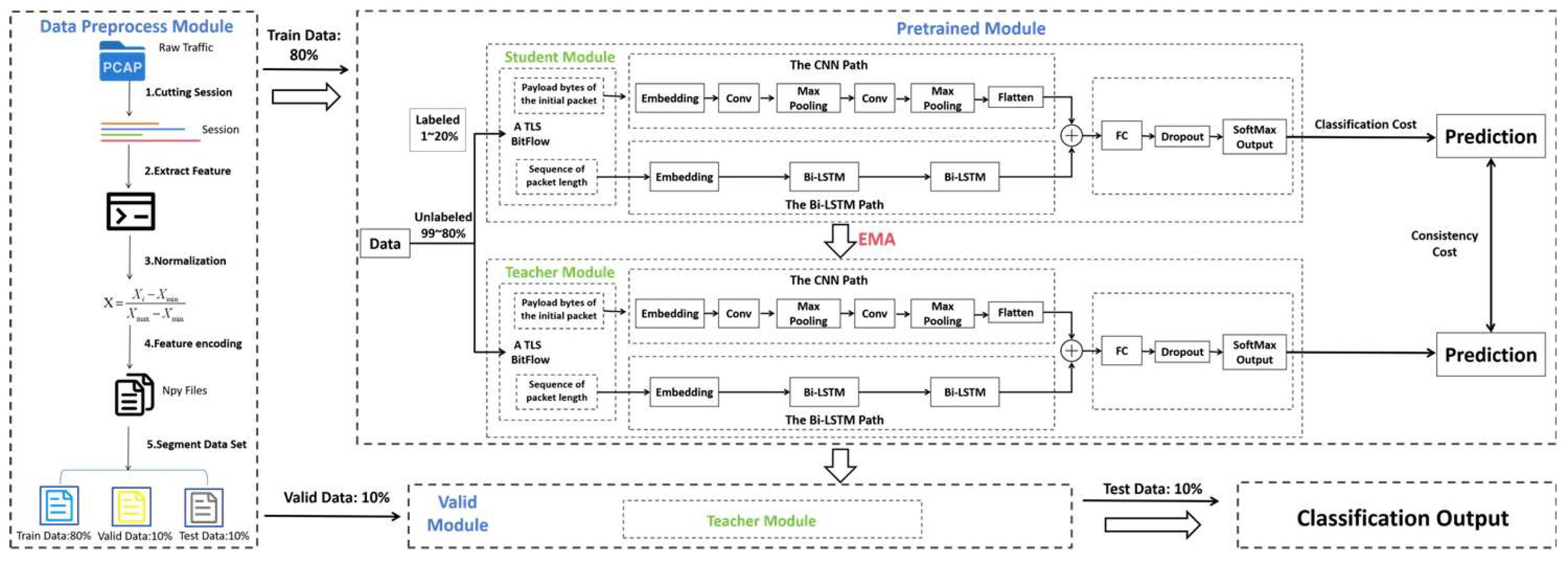

3.1. System Architecture of CLSTM-MT

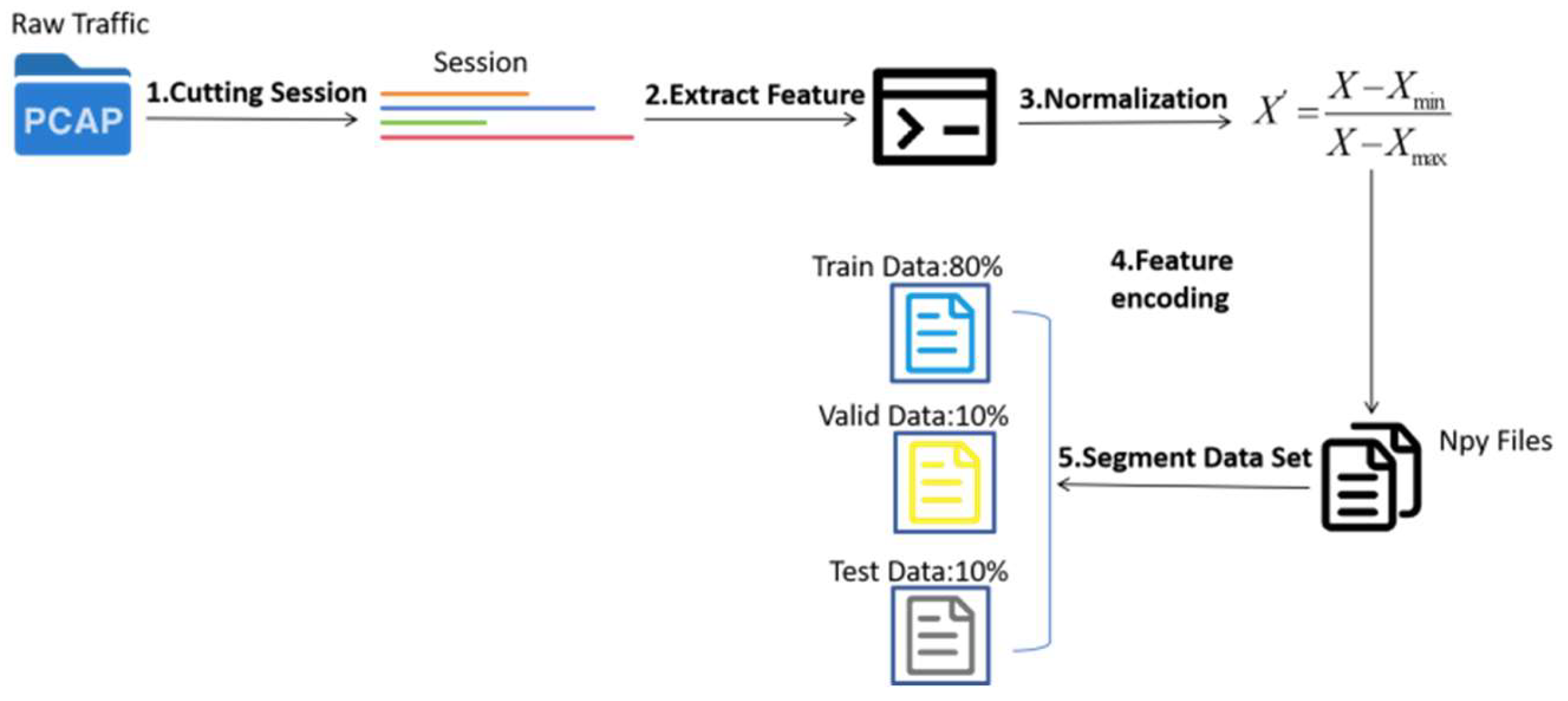

3.2. Data Preprocessing Module

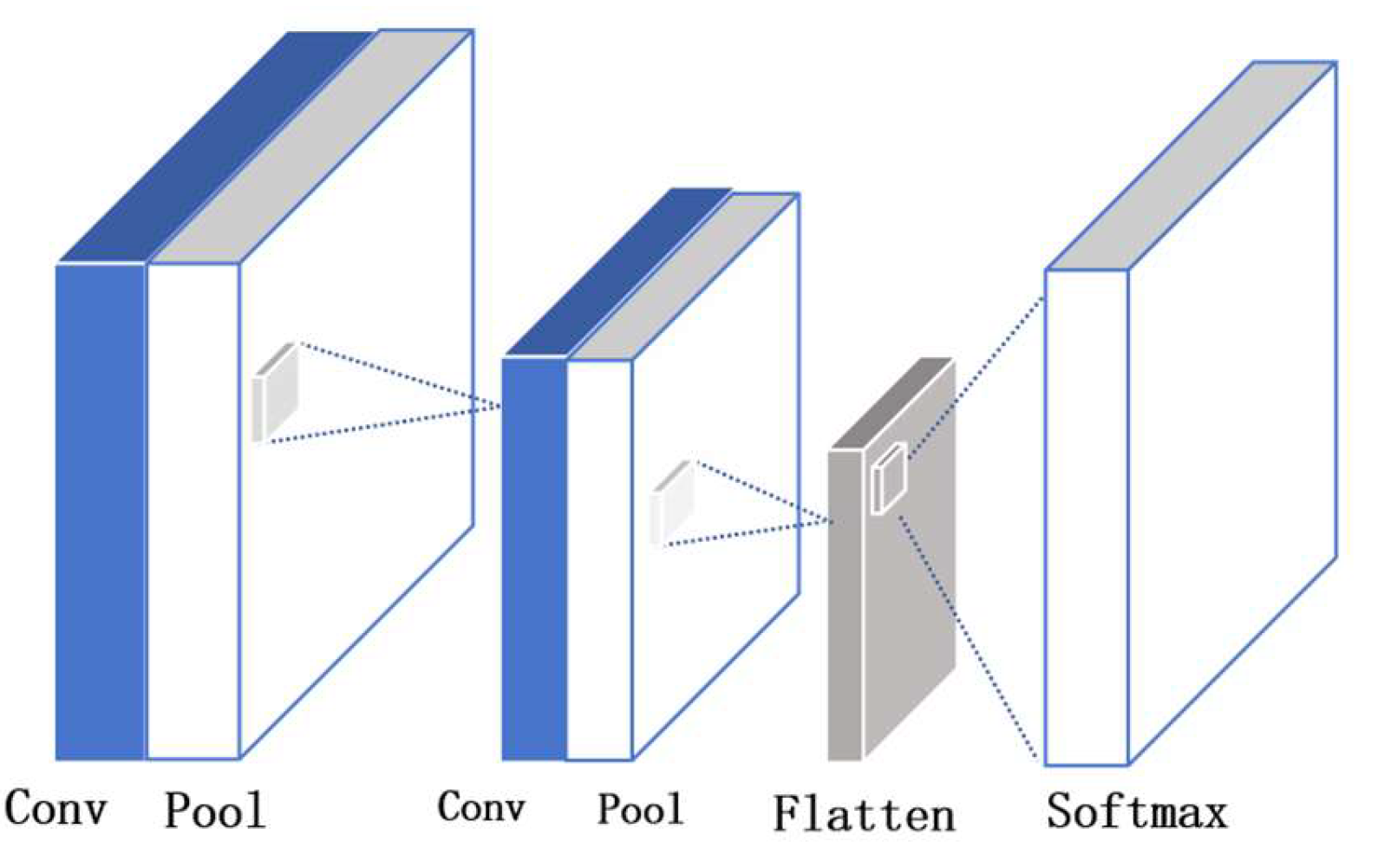

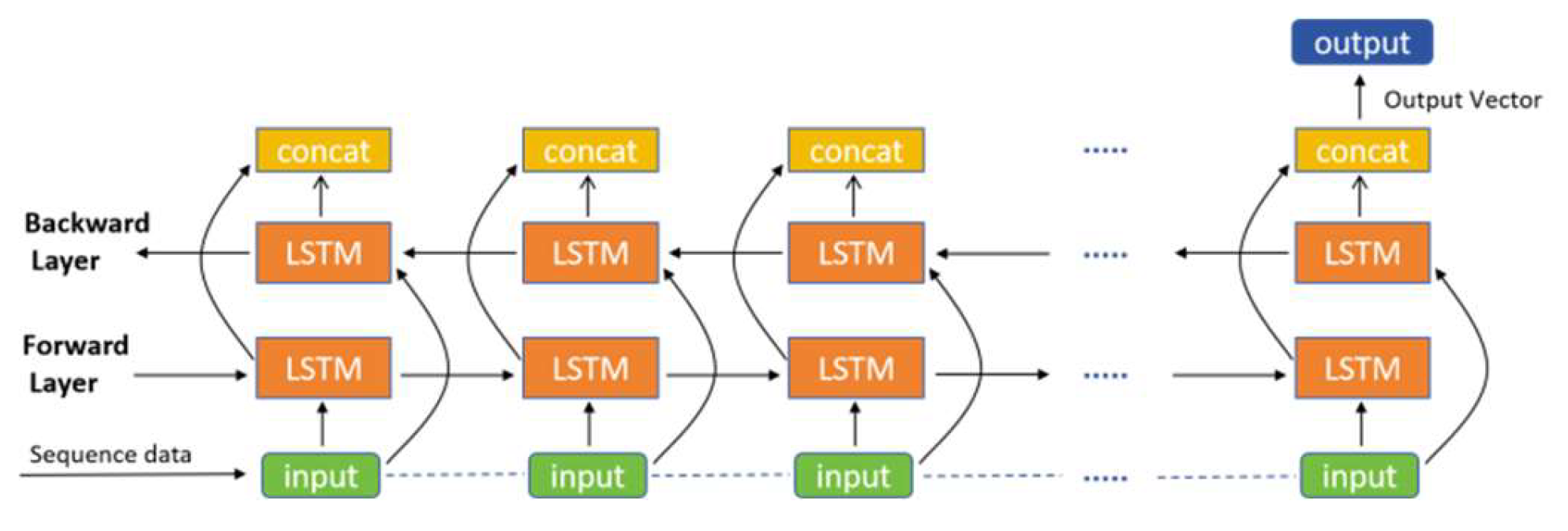

3.3. Model Design

3.4. Mean Teacher Framework Integration

4. Experimental Evaluation

4.1. Experimental Setup

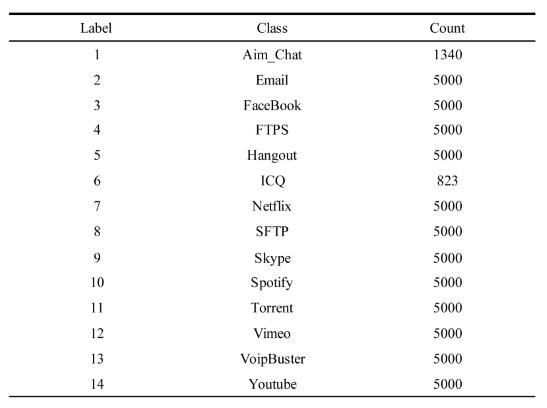

4.1.1. Data Preparation

4.1.2. Equipment Requirements

4.1.3. Evaluation Metrics

- Accuracy (AC): The proportion of correctly classified samples out of the total number of samples.

- Precision (PC): The proportion of correctly classified positive samples out of all predicted positive samples.

- Recall (RC): The proportion of correctly classified positive samples out of all actual positive samples.

- F1 Score (F1): The harmonic mean of precision and recall.

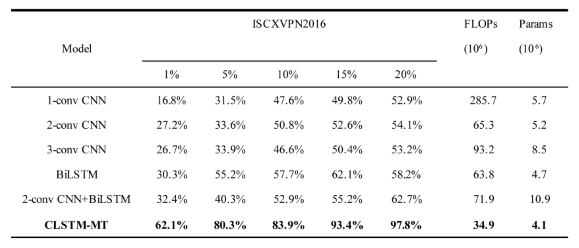

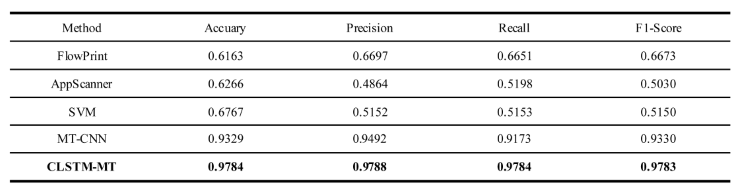

4.2. Experimental Results Compared to Baseline Models

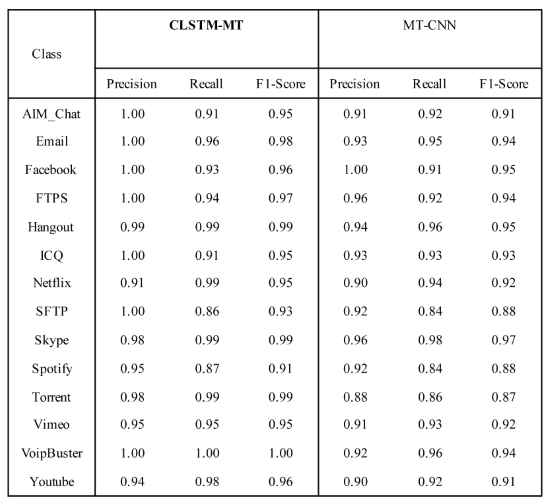

4.3. Compared with the Experimental Results of Other Advanced Models

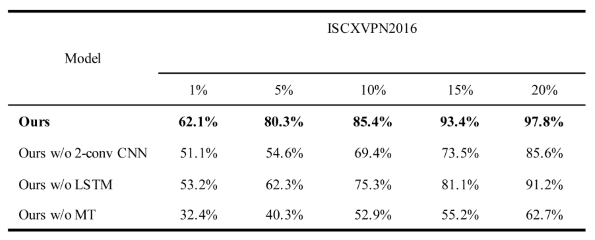

4.4. Ablation Experiments and Results

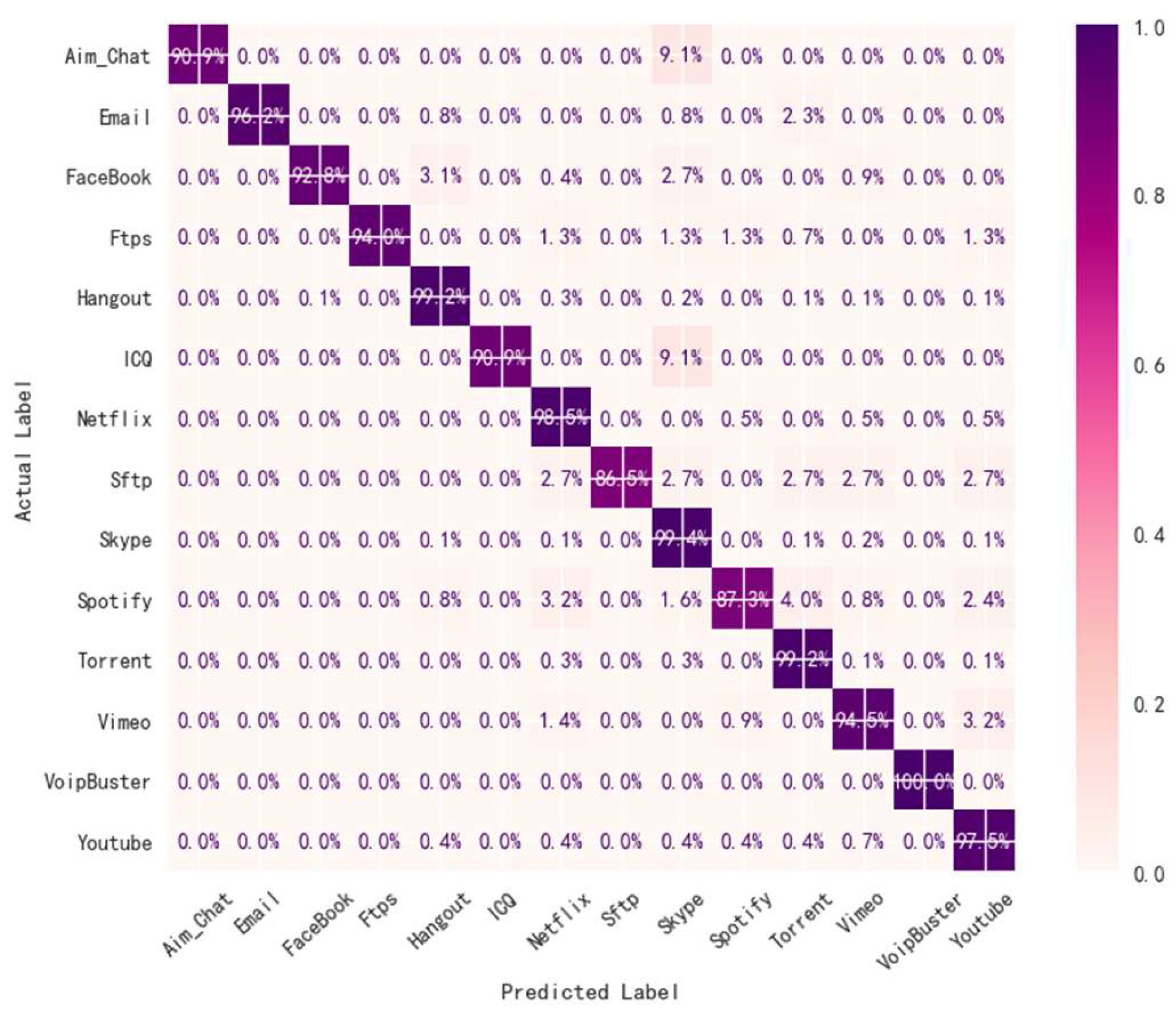

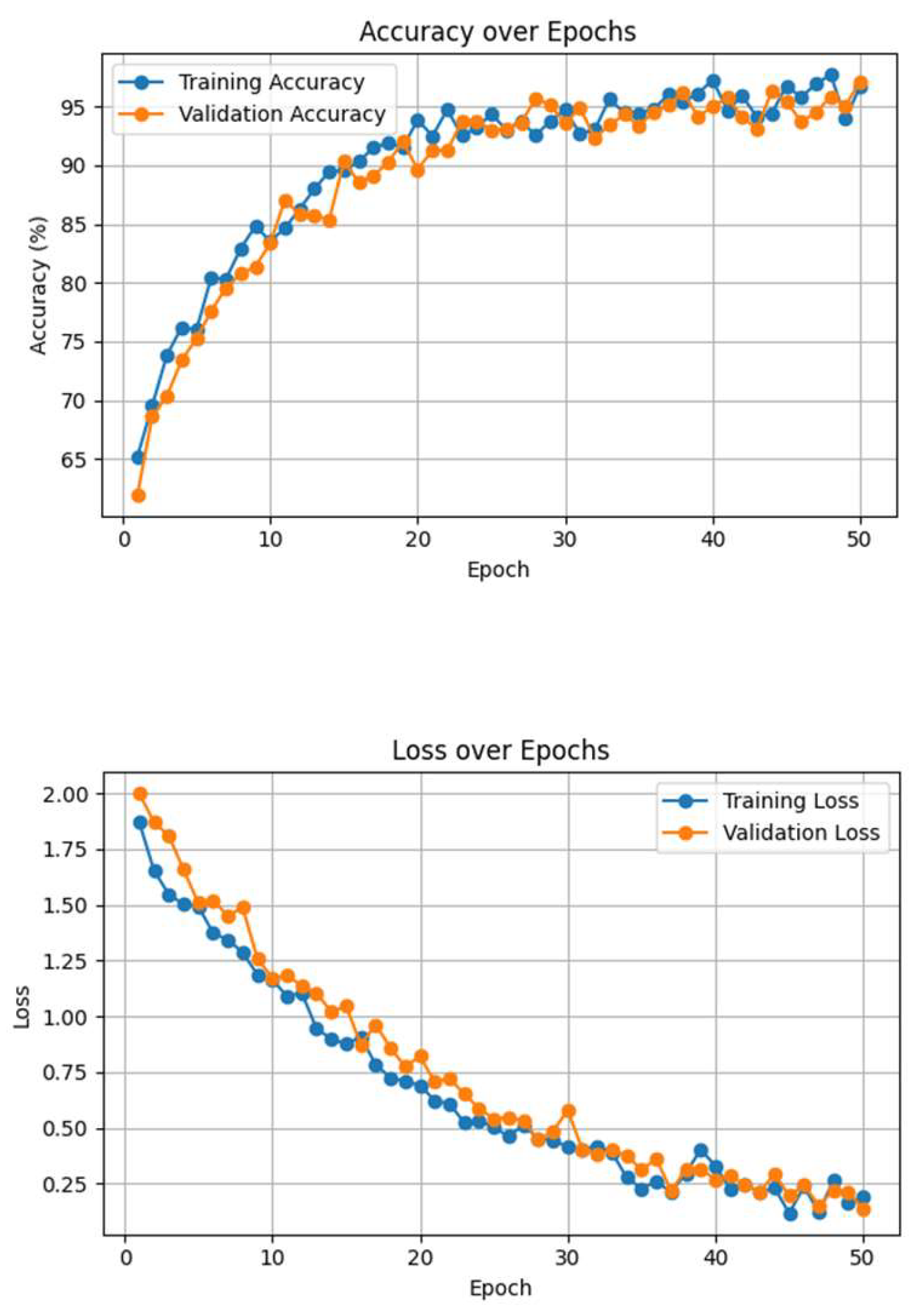

4.5. Analysis of Visual Experiment Results

5. Conclusions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

References

- S. Rezaei, X. Liu, Deep learning for encrypted traffic classification: An overview, IEEE Commun. Mag.57 (5) (2019) 76–81.

- Alberto Dainotti, Antonio Pescape, and Kimberly C Claffy. “Issues and future directions in traffic classification”. In: IEEE network 26.1 (2012), pp. 35–40.

- Liangchen, Chen; et al. “Research status and development trends on network encrypted traffic identification”. In: Netinfo Secur.(03) (2019), pp. 19–25.

- Soheil Hassas, Yeganeh; et al. “Cute: Traffic classification using terms”. In: 2012 21st International Conference on Computer Communications and Networks (ICCCN). IEEE. 2012, pp. 1–9.

- Perdisci, R., Lee, W., & Jajodia, S. (2014).A deep-learning approach to detecting encrypted malicious web traffic.In Proceedings of the 20th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (pp. 1271–1280). ACM.

- Chen, L., Li, Y., & Jiang, X. (2020).A deep convolutional neural network approach for encrypted traffic classification. Computer Communications, 155, 151–161.

- Arash Habibi Lashkari., Gerard Draper Gil., Mohammad Saiful Islam Mamun., and Ali A. Ghorbani. 2017. Characterization of Tor traffic using time based features. In International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy. 253–262.

- Yisroel Mirsky, Tomer Doitshman, Yuval Elovici, and Asaf Shabtai. 2018. Kitsune: an ensemble of autoencoders for online network intrusion detection. In Network and Distributed System Security Symposium (NDSS).

- Shengnan Hao, Jing Hu, Songyin Liu, Tiecheng Song, Jinghong Guo and Shidong Liu, “Improved SVM method for internet traffic classification based on feature weight learning,” 2015 International Conference on Control, Automation and Information Sciences (ICCAIS), Changshu, 2015, pp. 102-106.

- Ying Yang, Cuicui Kang, Gaopeng Gou, Zhen Li, and Gang Xiong. 2018. TLS/SSL encrypted traffic classification with autoencoder and convolutional neural network. In IEEE International Conference on High Performance Computing and Communications. 362–369.

- Chang Liu, Longtao He, Gang Xiong, Zigang Cao, and Zhen Li. 2019. FS-Net: a flow sequence network for encrypted traffic classification. In IEEE International Conference on Computer Communications (INFOCOM). 1171–1179.

- Thijs van Ede, Riccardo Bortolameotti, Andrea Continella, and et al. 2020. FlowPrint: Semi-Supervised Mobile-App Fingerprinting on Encrypted Network Traffic.

- A. Madhukar, C. Williamson, A longitudinal study of P2P traffic classification, in: 14th IEEE International Symposium on Modeling, Analysis, and Simulation, IEEE, 2006, pp. 179–188.

- Adil Fahad, Abdulmohsen Almalawi, Zahir Tari, Kurayman Alharthi, Fawaz S. Al-Qahtani, and Mohamed Cheriet. 2019. SemTra: A semi-supervised approach to traffic flow labeling with minimal human effort. Pattern Recognition 91 (2019), 1–12.

- Haipeng Yao et al. “Identification of encrypted traffic through attention mechanism based long short term memory”. In: IEEE transactions on big data 8.1 (2019), pp. 241–252.

- G. Draper-Gil, A.H. Lashkari, M.S.I. Mamun, A.A. Ghorbani, Characterization of encrypted and VPN traffic using time-related features, in: ICISSP 2016 - Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Information Systems Security and Privacy, no, Icissp, 2016, pp. 407–414.

- Tarvainen A, Valpola H. Mean teachers are better role models: Weight-averaged consistency targets improve semi-supervised deep learning results[J]. Advances in neural information processing systems, 2017, 30.

- K. Shi, Y. Zeng, B. Ma, Z. Liu and J. Ma, “MT-CNN: A Classification Method of Encrypted Traffic Based on Semi-Supervised Learning,” GLOBECOM 2023 - 2023 IEEE Global Communications Conference, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2023, pp. 7538-7543.

- Shumon Alam, Yasin Alam, Suxia Cui, and Cajetan M Akujuobi. Unsupervised network intrusion detection using convolutional neural networks. In 2023 IEEE 13th Annual Computing and Communication Workshop and Conference (CCWC), pages 0712–0717. IEEE, 2023.

- Alberto Dainotti, Antonio Pescape, and Kimberly C Claffy. “Issues and future directions in traffic classification”. In: IEEE network 26.1 (2012), pp. 35–40.

|

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).