Submitted:

18 December 2024

Posted:

19 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

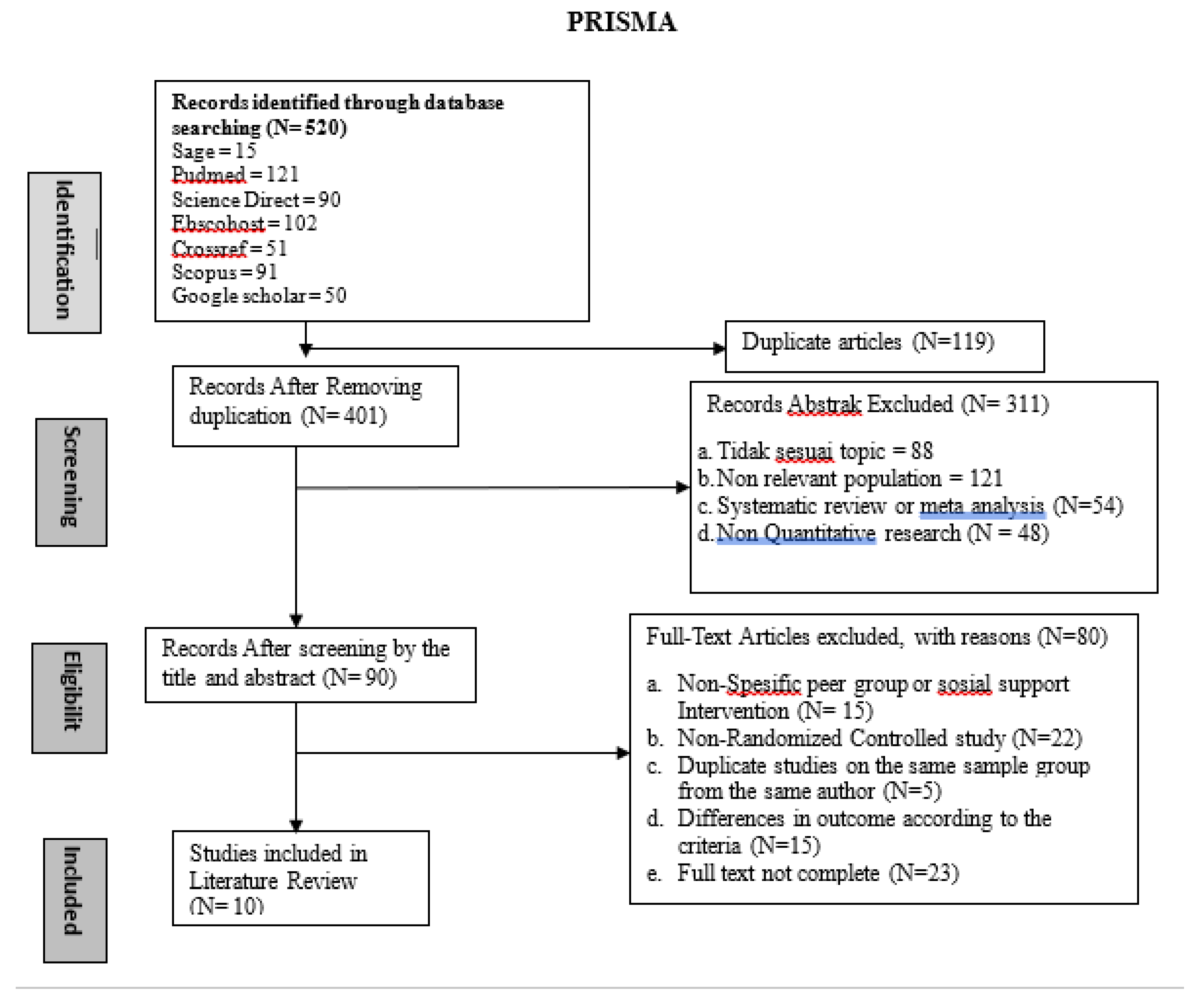

Depression in the elderly is a public health problem that is often significantly undetected and untreated which can lead to increased use of health facilities and even death, social support also plays an important role in behavioral change and self-management in the elderly in dealing with depression. This review aims to explore the effectiveness of peer group support applications in overcoming depression in the elderly. The narrative review approach with the Arksey and O'Malley methodological framework and the PRISMA 2020 diagram formulates how peer group interventions can help reduce depression levels in the elderly. The articles reviewed were selected using inclusion criteria such as elderly population, focus on older adults, depression, treatment, peer group interventions, social support, and using a randomized controlled trial (RCT) design. Data sources include databases such as PubMed, ScienceDirect, Scopus, Google Scholar, Sage, Crossref, and Ebscohost with a publication year range of 2020-2024. A total of 10 articles that met the criteria were obtained through strict selection from 520 initial articles. Based on the systematic review that has been conducted, the results obtained show that there is effectiveness of peer support-based approaches in various contexts, ranging from sports, education, to Cognitive Behavioral Therapy training. Differences in results indicate the diversity of intervention designs and subject populations, but the majority of studies show significant benefits in reducing depression in the elderly, in addition to the results of the narrative review there are also benefits to the quality of life, cognitive function and mental health of the elderly.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

- Population of elderly age,

- The article discusses depression in the elderly,

- interventions discuss peer groups or social support

- Full text complete

- Quantitative research,

- Study design using randomized control trial

- Articles published in 2020-2024.

2.2. Resources

2.3. Study Selection

- Keywords used in the article search included: “Social support” AND “Depression” AND “Elderly”, “Peer group” AND “Depression” AND “older adults”, “Treatment” AND “Depression” AND “Elderly” AND “Randomized Control Trial”, “Peer group” AND “Depression” AND “Elderly” AND “Randomized Control Trial”, “Social support to reduce depression in the elderly from 2020 to 2024” .

- Article selection uses the publication year filter, namely 2020-2024

- Article selection was based on abstract content, title, and keywords in articles about peer groups or social support in overcoming depression in the elderly .

- Articles that have been selected based on title, abstract, and other inclusion criteria will be further critically analyzed using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) instrument for Randomized Control Trials to determine the eligibility of the articles. Articles are evaluated based on the following criteria which, as recommended by the JBI manual, were decided and agreed upon by all authors: (i) “High quality” if all criteria are met; (ii) “Moderate quality” if one or more criteria are unclear; (iii) “Low quality” if one or more criteria are not met. Conflicts in quality scores were resolved through discussion and consensus among researchers .

2.4. Data Collection Process

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Characteristic Study

3.3. Quality Assessment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

5.1. Implications for Practice/Healthcare

5.2. Implications for Research

Compliance with ethical standards

References

- A. Mitchell, “Prognosis Of Depression in Old Age Compared to Middle Age: A Systematic Review Of Comparative Studies,” Am. J. Psychiatry, vol. 162(9), pp. 1588–1601, 2013.

- K. Hay, W. Stageman, and C.L. Allan, “Review of treatments for late-life depression,” Clin. Top. Old Age Psychiatry , pp. 243–253, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Devita et al. , “Recognizing Depression in the Elderly: Practical Guidance and Challenges for Clinical Management,” Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. , vol. 18, no. null, pp. 2867–2880, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- O. World Health, “Depressive disorder (depression),” 2023, [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression.

- H. Idris and SN Hasri, "Factors Associated with the Symptoms of Depression among Elderly in Indonesian Urban Areas," J. Psychol. , vol. 50, no. 1, p. 45, 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. Karami, M. Kazeminia, A. Karami, Y. Salimi, A. Ziapour, and P. Janjani, “Global prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress in cardiac patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis, ” J. Affect. Disord., vol. 324, pp. 175–189, 2023. [CrossRef]

- PMA Santoso, Y. Turana, YS Handajani, and E. Suryani, "The Relationship of Diabetes Mellitus, Cognitive Impairment, Sleep Disturbance, and Sleep Impairment on Depression among Elderly 75 Years Old and Over in Indonesia," Aging Med. Health c., vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 122–129, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Schmidt, S. Wilhelmy, and D. Gross, “Retrospective diagnosis of mental illness: past and present,” The Lancet Psychiatry, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 14–16, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. Ingram, “Depression,” Encycl. Hum. Behav. Second Ed., pp. 682–689, 2012. [CrossRef]

- N. Hossain, M. Prashad, E. Huszti, M. Li, and S. Alibhai, “Age-related differences in symptom distress among patients with cancer.,” J. Geriatr. Oncol., vol. 14, no. 8, p. 101601, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Nikunlaakso, K. Selander, T. Oksanen, and J. Laitinen, "Interventions to reduce the risk of mental health problems in health and social care workplaces: A scoping review," J. Psychiatr. Res., vol. 152, pp. 57–69, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Belfiori, F. Salis, G. Demelas, and A. Mandas, “Association between Depressive Mood, Antidepressant Therapy and Neuropsychological Performances: Results from a Cross-Sectional Study on Elderly Patients.,” Brain Sci. , vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 54-null, 2024, [Online]. Available: https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=a5dcb853-9193-3cac-a5de-437cac4102fe.

- JA, Sirey; et al. , “Community delivery of brief therapy for depressed older adults impacted by Hurricane Sandy.,” Transl. Behav. Med., vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 539–545, Aug. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RW Resna et al. , “Social environmental support to overcome loneliness among older adults: A scoping review,” 2022. [Online]. Available: https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=c89a0702-0791-3be9-8550-1cded9c0c666.

- GNM Gurguis, “Psychiatric disorders,” Platelets, Second Ed. , pp. 791–821, 2006. [CrossRef]

- A. Pilozzi, C. Carro, and X. Huang, “Roles of β-endorphin in stress, behavior, neuroinflammation, and brain energy metabolism,” Int. J. Mol. Sci., vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 1–25. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. Naumov, “Empathy, Stress and Biopsychological Homeostasis. Hormonal-Loop Disorders Theory,” 2022, [Online]. [CrossRef]

- M. Kanova and P. Kohout, “Serotonin—its synthesis and roles in the healthy and the critically ill,” Int. J. Mol. Sci. , vol. 22, no. 9, 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. Liu et al. , “Attitudes toward aging, social support and depression among older adults: Difference by urban and rural areas in China.,” 2020. [Online]. Available: https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=d54c7c9a-b59f-3614-840f-79c7bcc557d7.

- Y. Christiani, JE Byles, M. Tavener, and P. Dugdale, "Exploring the implementation of poslansia, Indonesia's community-based health program for older people," Australas. J Aging , vol. 35, no. 3, pp. E11–E16, 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. Greenberg, “The Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) Geriatric Depression Scale: Short Form,” Best Practice. Nurs. Care for Older Adults, no. 4, pp. 1–2, 2012.

- CWM Sari, VN Khoeriyah, and M. Lukman, "Factors Related to The Utilization of Integration Health Program (Posbindu) Among Older Adults in Indonesia: A Scoping Review," Clin. Interv. Aging , vol. 19, pp. 1361–1370, 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Aji, S. Masfiah, D. Anandari, AD Intiasari, and DA Widyastari, "Enablers and Barriers of Healthcare Services for Community-Dwelling Elderly in Rural Indonesia: A Qualitative Evidence Synthesis," Port. J. Public Heal., vol. 41, no. 1, pp. 65–79. 2023. [CrossRef]

- LN Geffen, G. Kelly, JN Morris, and EP Howard, “Peer-to-peer support model to improve quality of life among highly vulnerable, low-income older adults in Cape Town, South Africa,” BMC Geriatr., vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 1–12. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AMC Stafford, MC Aalsma, S. Bigatti, U. Oruche, and C.B. Draucker, “Getting a Grip on My Depression: How Latina Adolescents Experience, Self-Manage, and Seek Treatment for Depressive Symptoms,” Qual. Health Res. , vol. 29, no. 12, pp. 1725–1738, 2019. [CrossRef]

- L. Zhao et al. , “Mediation role of anxiety on social support and depression among diabetic patients in elderly caring social organizations in China during COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study,” 2023. [Online]. Available: https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=c2380ce5-4229-37d7-a089-bada55b35aef.

- J. Zhao et al. , “Unraveling the mediating role of frailty and depression in the relationship between social support and self-management among Chinese elderly COPD patients: a cross-sectional study,” 2024. [Online]. Available: https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=f9192f3d-69e0-31ed-a304-f750630b0909.

- YJG Korpershoek, ID Bos-Touwen, JM De Man-Van Ginkel, JWJ Lammers, MJ Schuurmans, and JCA Trappenburg, “Determinants of activation for self-management in patients with COPD,” Int. J COPD , vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 1757–1766, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Harpreet S Duggal, “Self-Management of Depression: Beyond the Medical Model,” Perm. Journal , vol. 23:18-295, 2019. [CrossRef]

- PK Sabeena and VS Kumar, “Psycho-Social Intervention for Managing Depression Among Older Adults – a Meta-Analysis,” J. Evidence-Based Psychother. , vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 1–30, 2022. [CrossRef]

- KR Haase et al. , “Systematic review of self-management interventions for older adults with cancer,” Psychooncology. , vol. 30, no. 7, pp. 989–1008, 2021. [CrossRef]

- NAW Aqila, A. Qtrunnada, AP Pasa, AF Anggraeni, and OF Ningrum, "The Effect of Mind-Body Interventions on Improving the Quality of Life for the Elderly (Literature Study) (In Bahasa)," FISIO MU Physiother . Evidence , vol. 2, no. 3, pp. 162–175, 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Song et al. , “The Effect of Modified Tai Chi Exercises on the Physical Function and Quality of Life in Elderly Women With Knee Osteoarthritis,” Front. Aging Neurosci. , vol. 14, no. May, pp. 1–10, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Baklouti et al. , “The effect of web-based Hatha yoga on psychological distress and sleep quality in older adults: A randomized controlled trial,” Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. , vol. 50, p. 101715, 2023. [CrossRef]

- DWL Lai, J. Li, X. Ou, and CYP Li, “Effectiveness of a peer-based intervention on loneliness and social isolation of older Chinese immigrants in Canada: A randomized controlled trial,” BMC Geriatr. , vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 1–12, 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Smith-Turchyn et al. , “A pilot randomized controlled trial of a virtual peer-supported exercise intervention for female older adults with cancer.,” BMC Geriatr. , vol. 24, no. 1, p. 887, 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. Crist et al. , “Health effects and cost-effectiveness of a multilevel physical activity intervention in low-income older adults; results from the PEP4PA cluster randomized controlled trial,” Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. , vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 1–15, 2022. [CrossRef]

- SJ Andreae, LJ Andreae, JS Richman, AL Cherrington, and MM Safford, “Peer-delivered cognitive behavioral training to improve functioning in patients with diabetes: A cluster-randomized trial,” Ann. Fam. Med., vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 15–23. 2020. [CrossRef]

- PWC Li, DSF Yu, PM Siu, SCK Wong, and BS Chan, “Peer-supported exercise intervention for persons with mild cognitive impairment: A waitlist randomized controlled trial (the BRAin Vitality Enhancement trial),” Age Aging, vol. 51, no. 10, pp. 1–10. 2022. [CrossRef]

- RA Merchant, CT Tsoi, WM Tan, W. Lau, S. Sandrasageran, and H. Arai, “Community-Based Peer-Led Intervention for Healthy Aging and Evaluation of the 'HAPPY' Program,” J. Nutr. Heal. Aging, vol. 25, no. 4, pp. 520–527. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Mohammadbeigi, M. Khavasi, M. Golitaleb, and K. Jodaki, “The effect of peer group education on anxiety, stress, and depression in older adults living in nursing homes,” Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res., vol. 26, no. 3, pp. 252–257. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Hong, M. Gang, and J. Lee, “Effects of the Life-Love Program on depression, perceived burdensomeness, and suicidal ideation,” Collegian, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 102–108. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Ae-Ri, L. Kowoon, and P. Eun-A, “Development and evaluation of the information and communication technology-based Loneliness Alleviation Program for community-dwelling older adults: A pilot study and randomized controlled trial, ” Geriatr. Nurs. (Minneap)., vol. 53, pp. 204–211. 2023. [CrossRef]

- SJ Liao, SM Chao, YW Fang, JR Rong, and CJ Hsieh, “The Effectiveness of the Integrated Care Model among Community-Dwelling Older Adults with Depression: A Quasi-Randomized Controlled Trial,” Int. J Environ. Res. Public Health, vol. 19, no. 6, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Desanti Agustina Enggalita and Wachidah Yuniartika, “Reminiscence techniques in reducing stress in the elderly: Literature review,” Open Access Res. J. Sci. Technol., vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 059–064. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. J. Czaja, W. R. Boot, N. Charness, W. A. Rogers, and J. Sharit, “Improving Social Support for Older Adults Through Technology: Findings From the PRISM Randomized Controlled Trial,” Gerontologist, vol. 58, no. 3, pp. 467–477. 2018. [CrossRef]

- HH Tsai, CY Cheng, WY Shieh, and YC Chang, “Effects of a smartphone-based videoconferencing program for older nursing home residents on depression, loneliness, and quality of life: A quasi-experimental study,” BMC Geriatr., vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 1–11. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Shapira, E. Cohn-Schwartz, D. Yeshua-Katz, L. Aharonson-Daniel, A. M. Clarfield, and O. Sarid, “Teaching and practicing cognitive-behavioral and mindfulness skills in a web-based platform among older adults through the COVID-19 pandemic: A pilot randomized controlled trial,” Int. J Environ. Res. Public Health, vol. 18, no. 20, pp. 1–14. 2021. [CrossRef]

- X. Ma, X. Zhang, X. Guo, K. hung Lai, and D. Vogel, “Examining the role of ICT usage in loneliness perception and mental health of the elderly in China,” Technol. Soc. , vol. 67, no. July, p. 101718, 2021. [CrossRef]

| Author, Year | Participant | Participant Age | Instrument | Study design | Intervention | Details Topic and Activity (week) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daniel W. et al, 2020 [35] | I : 30 C: 30 |

Community-dwelling seniors aged > 65 years | De Jong Loneliness Scale-6, Lubben Social Network Scale (LSNS) , General Depression Scale (GDS-4), Geriatric Anxiety Inventory – Short Form (GAI-SF), Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale two items (CD-RISC 2) | RCT | Peer-based intervention | This study used two groups, namely the intervention group and the control group, where the intervention group received peer support intervention for eight weeks and the control group only received short telephone calls from the program coordinator over an eight-week period. |

| Jenna ST, et al. 2024 [36] | I: 8 C: 8 |

Older adult women with an average age of 72 years | Social Support Survey (SSS), EQ-5D VAS using 10-point VAS, Patient-Specific Functional Scale (PSFS), Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale | RCT | AgeMatchPLUS (peer support groups guided by a Qualified Exercise Professional (QEP), AgeMatch: Peer support groups without QEP guidance | The intervention group of older women participated in approximately 150 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity per week. Participants were paired with a partner who was provided with peer support guidance, exercise guidance, and a Fitbit Inspire©. The intervention group involved dyads communicating and supporting each other during exercise, independently structuring their communication (mode and frequency) with their matched partner. Together, the dyads also participated in weekly virtual sessions using Zoom where they received support from a qualified exercise professional (QEP) for 10 weeks. Each session lasted up to 1 hour. The control group was asked to communicate and support each other independently regarding exercise during the 10-week intervention period without the assistance of a qualified exercise professional (QEP). |

| Katie Crist, et al, 2022 [37] | I: 6 C: 6 |

Elderly ≥ 60 years | ActiGraph GT3X+ Accelerometer, Perceived Quality of Life Scale (PQoL-20), 6-Minute Walk Test (6-MWT), Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CESD-10) | RCT | Community-based interventions (PEP4PA) | Trained PHCs lead group walks twice a week, review progress toward step goals and barriers with participants, and organize activities and events to maintain motivation. They are responsible for communicating educational tips and leading group discussions designed to provide social support, share successes and benefits, address walking challenges, and identify strategies to overcome barriers. UC San Diego research staff meet with PHCs weekly for the first 3 months, biweekly for months 3–6, and then monthly thereafter to provide support. PEP4PA participants are guided in goal setting, self-monitoring, and additional effective SCT behavior change strategies as they work toward individual step goals. |

| Susan J. et al. 2020 [38] | I: 25 C: 25 |

Elderly ≥ 60 years | Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC), Short Form 12 (SF12), | RCT | CBT-based interventions | Intervention participants received a 3-month peer-delivered, telephone-administered program. Attention control participants received a general health advice program delivered by peers. |

| Li Polly, et al. 2022 [39] | I: 116 C: 113 |

The average age of the elderly is 74.4 years | Neuropsychological tests, Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale–Cognitive Subscale (ADAS-Cog) 11 items, Short Form 36 Health Survey (SF-36) | RCT | Peer-supported exercise interventions | The intervention group received an 8-week peer-supported, group-based multicomponent exercise intervention, while a wait-list control group received usual care. A battery of neuropsychological tests and the Short Form-36 were administered at baseline, immediately after the intervention, and 3 months after the intervention. |

| Merchant et al, 2021 [40] | 197 participants | Elderly aged 60 years who live in the community | MoCA, FRAIL, SPPB, LSNS-6, geriatric depression scale, EuroQol questionnaires | RCT | HAPPY Program | HAPPY is a dual-task exercise program adapted from cognicise, which originated at the National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology in Nagoya, Japan. Cognicise is a multicomponent exercise program that combines physical, cognitive, and social activities with the goal of improving cognition in older adults with mild cognitive impairment. The exercise component includes low-to-moderate intensity circuit and resistance training as secondary outcomes focused on physical function performed in pairs. The exercises are performed for 60 minutes once or twice a week depending on the location and preference of the center and the availability of volunteers, and are led by a health coach or volunteer. |

| Mohammadbeigi et al, 2021 [41] | 70 elderly | Seniors with an average age of 73 years | DASS-21 Questionnaire | RCT | Peer group education involving training in relaxation and stress reduction techniques | Intervention group, relaxation and stress reduction program trained through peer group. Control group received routine care |

| Misook Hong, et al, 2022 [42] | 32 people | 65 year old elderly | Geriatric Depression Scale Short Form (GDSSF), Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire-Revised (INQ-R) Korean version, Suicidal Ideation (Suicide Ideation) using the Scale for Suicide Ideation (SSI). | RCT | Life-Love Program Intervention | Using the term “Life-Love” to reduce resistance to participation and increase accessibility. Activities include: music therapy, therapeutic recreation, aromatherapy, arts and crafts, horticulture therapy, cooking, and laughter therapy, designed to improve interpersonal relationships. Educating participants with more accurate and positive thoughts, and keeping a journal as a monitoring. |

| Jung Ae-Ri, et al, 2023 [43] | 40 elderly participants | Elderly aged ≥ 60 years | Los Angeles Loneliness Scale (R-UCLA). Geriatric Depression Scale Short Form - Korean Version (GDSSF-K). Laughter Index Laughter Index Scale 30 items. |

RCT | LAP Intervention Program (Loneliness Alleviation Program) | The LAP (Loneliness Alleviation Program) consists of 12 sessions delivered twice a week for 6 weeks. Participants watch YouTube Videos delivered twice a week via mobile phone text messages and messenger to learn related content and practice it. The first session of the program, face-to-face introduction and instructions on how to watch YouTube videos and booklet distribution, then participants are given worksheets to fill out if they have watched the videos and equipment for horticulture therapy. Sessions 2 to 12 of the program are delivered via YouTube videos, and the program content consists of smartphone use, horticulture therapy, medication management, laughter therapy, music exercise therapy, and sleep relaxation. |

| Su-Jung Liao, 2022 [44] | 143 respondents | Elderly aged ≥ 60 years | Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) CES-D, Brief Symptom Rating Scale (BSRS-5) to measure five items of symptoms of anxiety, depression, hostility, interpersonal sensitivity/inferiority, and insomnia. Life Satisfaction Index (LSI) LSI |

RCT | ICM (Integrated Care Model) Intervention | The interventions were summarized in the following domains: Assessing and managing health problems, Achieving spiritual and mental well-being, Improving activities of daily living and mobility, Providing social well-being and Providing prevention of elder abuse. The interventions were implemented over a 12-week period. |

| Author | Quality |

| Daniel W. et al, 2020 [35] | Medium quality |

| Jenna ST, et al. 2024 [36] | Low quality |

| Katie Crist, et al, 2022 [37] | Medium quality |

| Susan J. et al. 2020 [38] | Low quality |

| Li Polly, et al. 2022 [39] | Low quality |

| Merchant et al, 2021 [40] | Medium quality |

| Mohammadbeigi et al, 2021 [41] | Low quality |

| Misook Hong, et al, 2022 [42] | Medium quality |

| Jung Ae-Ri, et al, 2023 [43] | Medium quality |

| Su-Jung Liao, 2022 [44] | Medium quality |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).