1. Introduction

Over the past few decades, the debate over climate change has grown in importance and affected both domestic and international policy. One of the several factors contributing to climate change is deforestation. Although perspectives regarding the extent of human influence on temperature increases and the greenhouse effect remain varied, deforestation is an undeniable fact. In actuality, before human civilizations developed, 60 million square kilometers of forest blanketed the planet. Due to deforestation, there are currently fewer than 40 million square kilometers remaining [

1].

The most vulnerable countries to deforestation and climate change are developing nations like Bangladesh. Higher temperatures, erratic precipitation, and extreme weather events are all effects of climate change that have already started to affect Bangladesh’s economic performance. Deforestation impacts one important channel for carbon uptake and releases a huge quantity of carbon into the atmosphere globally. Tropical forests are especially under pressure to sustain long-term deforestation since they have the highest aboveground biomass and absorb carbon at one of the quickest rates per unit land area. Because atmospheric

is uniform and has a long half-life, the decisions made now on forest management will have a long-lasting effect on

alone. But albedo, evapo- transpiration (ET), and canopy roughness—the three primary biophysical processes that forests regulate—all directly affect climate [

2].

The stability and sustainability of the timber supply, wind breaks, and environmental improvement depend greatly on afforestation. Enhances the quality of the ecosystem for both flora and fauna, contributes to food security, and has a favorable impact on the growth of the human population. Between 2001 and 2020, 1.48 million

of tropical land were lost to deforestation, more than the combined area of France, Spain, and Germany. During this time, the tropics have lost more than half of the world’s forests, and in recent years, the loss of tropical forests has increased more sharply than that of other global regions [

3]. The empirically produced “forest-transition" model, which is defined by minimal loss of native forest area, has divided nations into phases at the national level, planting new forests (posttransition), quickening the rate of forest loss (early transition), and slowing it down (late transition) [

4]. Because the Congo Basin and the Amazon have quite different social, political, and economic environments, the former has seen less deforestation than the latter. Most of the loss is propelled by the residents of nearby towns and cities as well as small-scale commercial and subsistence farmers who clear trees for their own need for food [

5].

A widespread fire and respiratory health risks, along with the increasing deforestation in the Amazon, could lead to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. All Amazonians would be at risk from this, but traditional and rural communities would be particularly vulnerable. The Brazilian Amazon saw 3070

of deforestation between January and June, which is 25% greater than at the same period in 2019 [

6].

We can know about a wide range of theoretical frameworks that can be applied to study ecological variability and stability at different scales in [

7]. An overview of the many forest biomes is provided, with a focus on how the fragmentation of the forests is a result of the growth of agricultural borders. The discussion also includes long-term ecological research carried out globally in an effort to piece together the history of forest fragmentation and destruction in [

8]. A study that examines the causes of deforestation and presents an integrated strategy that includes both forestry and agriculture to prevent deforestation in [

9]. A wide range of wildlife species, including plants, animals, insects, and birds, can find new homes through afforestation. Numerous species can be found in the wide variety of microhabitats that forests provide, including tree canopies, understory vegetation, and forest floors. We can know about more effects of afforestation on wildlife in [

10]. A summary of Global Environmental Changes (GECs) can be found in [

11], where the decline in biodiversity and changes in biogeochemical cycles are discussed. We can know about the bifurcation analysis of the spruce budworm model and the population model with harvesting in [

12]. In [

13] the density of evolution for a population of a single species with a harvesting effect is examined in a heterogeneous environment where all functions are spatially distributed in time series. We can know about the age-structured parabolic-ordinary system that governs the forest environment, a few characteristics of the dynamical system, an abstract parabolic equation, and the limit sets in [

14].

In this paper, we would know more about deforestation and its negative effects. We also discuss situations when afforestation is greater than deforestation, when deforestation is greater than afforestation and periodic behavior of the mathematical model. We can also know the importance of reforestation to prevent deforestation. In this study, we develop mathematical models for deforestation, afforestation and reforestation. The objects of the study are:

Case study in Bangladesh for deforestation.

Describing the causes of deforestation and it’s negative effects on climate change.

Observing the effects on forest when afforestation is greater than deforestation, deforestation is greater than afforestation.

Analysing the importance of reforestation.

We organized the rest part of the paper as follows: We study about deforestation and discussed different kind of forest in Bangladesh in

Section 2. After that, we find the causes of deforestation and its negative effects in

Section 3 and

4. Mathematical models for deforestation and afforestation are developed and solved for stability analysis. We work on numerical results and draw figures for deforestation and afforestation in

Section 5. The steps to stop deforestation are discussed in

Section 6. Then, we add a new condition “reforestation" in mathematical model, develop conditions for stability analysis and draw graphs for reforestation in

Section 7. Finally, in

Section 8, we outline conclusion of the results.

2. Case Study in Bangladesh

Bangladesh is one of the countries having a high population density. The predominant use of land in the country is longitudinal agriculture. The country has 13.02 million hectares in size and has 160 million people. In Bangladesh, forests span around 2.47 million hectares, or 18% of the country’s total land area, accounting for 0.15 percent of the world’s tropical forest area. Deforestation has an impact on one-eighth of the nation [

15].

Bangladesh’s population growth is the main factor contributing to deforestation. Due to population increase, there has been a decrease in the nation’s forests since the turn of the 20th century. This is because more land is needed for housing, industry, and agriculture. In the 1980s, 8000 hectares of forest were lost annually, but with population growth 37,700 hectares each year. Deforestation increases climate change, decreases rainfall, causes soil erosion, harms ecosystems and biodiversity, and endsanger species [

16]. Bangladesh’s low land area to population ratios highlight the fierce fight for the country’s extremely scarce land resources. The direct outcome is deforestation and degradation of the forest supply, both of which are rising as the population grows. Although current forest cover is significantly lost, reforestation of sites that have been cleared of vegetation yields very modest improvements, and recently added land.

2.1. Forest in Bangladesh

The Bangladesh Forest Department (BFD) owns and manages roughly 61.52% of the forestlands which is 1,600,000 hectares, while it is in charge of 26.80% of the unclassified forest which is 697,000 hectares by of the deputy commissioner and the district’s executive chief, and 10.38% (270,000 hectares) are communal and private woods, both under community management [

17]. Some kinds of forest are,

Hill Forests:Over 680,000 hectares, mostly in the northeast and southeast of the nation, are mixed-evergreen hill forests, which make up the majority of Bangladesh’s hill forests. While mixed-evergreen forests still make up some sizable areas in the southeast’s Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT), the majority of the northeast’s forests are dispersed [

17].

Sal Forests:Approximately 120,000 hectares, or 0.81% of the country’s total land area, are covered by Bangladesh’s sal forest, also known as moist deciduous forests. The greatest single mass of deciduous woodland is found in the country’s center [

17].

Mangrove plantations and their natural habitats: An area of 801,700 hectares along the Bay of Bengal coast is covered by mangrove forests. Of the whole coastal forest, 200,000 hectares are made up of coastal plantations, 601,700 hectares are natural mangroves, and the Sundarbans are the greatest area of productive mangrove forest in the world. There are a considerable number of evergreen plant species in this forest that are suited to living in salty environments with regular tidal flooding [

17].

3. Causes of Deforestation

Deforestation is a result of a multitude of factors. We’ll talk about some of the main causes of deforestation. Such that, 90% of deforestation, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), is caused by unsustainable agricultural practices. Regardless of how controversial these numbers are “Unsustainable agriculture" is unquestionably one of the major factors contributing to deforestation in a number of nations [

18].

Forests are cleared to create the land needed for expanding cities and towns to build the infrastructure required to support a growing population. Tropical forests are frequently the focus of infrastructure development for the purposes of oil exploitation, logging concessions, or the construction of hydropower dams. This inevitably leads to the development of new roads in undeveloped areas and the expansion of the road network. The development of highways, railroads, bridges, and airports makes the woodland frontier more populated and allows for more area to be developed. Eighty percent of the world’s resources are used by twenty percent of the world’s population [

19].

In tropical countries, uneven land distribution is the main factor exerting pressure on human settlement rather than population growth. Furthermore, the populace typically lacks the money needed to maintain the quality of the soil or increase yields on currently cleared property. The unequal distribution of wealth is the main factor contributing to deforestation. Shifting growers near the forest frontier are among the most impoverished and marginalized groups in the society. They usually don’t own any land and have little capital. They are hence compelled to clear the forest. Deforestation, particularly clearing for agriculture, is often the primary source of income for farmers who reside in forested areas [

19].

4. Negative Effects of Deforestation

Deforestation greatly contributes to the acceleration of global warming. A significant amount of carbon dioxide is also released when trees are burned to clear land, which furthers the problem of global warming. Deforestation causes a decrease in the amount of water present in the soil, groundwater, and the atmosphere. The cohesion of the soil is also decreased. Followed by landslides, flooding, and erosion. Up to one-third of all anthropogenic carbon dioxide emissions, particularly in tropical places, are caused by deforestation, which is severely detrimental to the ecology. There are many more negative effects of deforestation such that,

The loss of habitat by many plant and animal species due to deforestation lowers biodiversity. Ecological disruptions have the potential to harm or eradicate a species.The removal of carbon dioxide () from the atmosphere is one of the main ways that trees regulate the climate. Because deforestation releases stored carbon into the atmosphere, it plays a part in the greenhouse effect and global warming.Soil is held together by tree roots, which inhibits soil erosion. In the absence of trees, the soil is more vulnerable to wind and water erosion, which results in the loss of rich topsoil and an increase in sedimentation in water bodies.Being able to draw water up from the earth and release it into the atmosphere through transpiration makes trees essential to the water cycle. Deforestation has the potential to upset local and regional water cycles, which can result in altered rainfall patterns, decreased groundwater recharge, and an increase in floods and droughts.

Numerous negative effects of deforestation can significantly affect the ecosystem and the standard of living of people. Initiatives to halt deforestation and promote sustainable land management practices are essential to reducing these effects.

5. Mathematical Model with Afforestation and Deforestation

The act of clearing forests or trees for uses other than forest protection, like agriculture, urbanisation, or timber harvesting, is known as deforestation. Its effects on the economy, society, and environment are diverse. Afforestation is the process of planting trees in regions that were previously devoid of forests or that had lost their forests. It is an essential strategy to mitigate the effects of deforestation. We will create mathematical models applicable to every forest worldwide.

5.1. Case 1: Afforestation Is Greater Than Deforestation

In case 1 we consider, afforestation is greater than deforestation. Here, we consider is the population of forest and the rate of change of forest is . The growth rate is , afforestation and deforestation occur at constant rates a and b, respectively.

The model is [

20,

21],

for

with initial condition,

Table 1.

Model parameters and their descriptions.

Table 1.

Model parameters and their descriptions.

|

Notation |

Definition |

| u |

Population of forest |

| t |

Time |

|

Growth rate |

| a |

Rate of afforestation |

| b |

Rate of deforestation |

5.1.1. Equilibrium Points and Stability Analysis

The solution

u is a funtion of

t. Such that

. The stability of the solution depends on the value of

. Let

is the equilibrium point of the differential equation. Now, for the equilibrium point,

Using the perturbation analysis, let us assume,

Putting the value of

u in the equation (2), we get,

Now we get,

Equation (

6) is similar to the original equation (2). So, the solution of (

6) is,

We now examine the solution’s stability analysis. The stability study is related to the linear system. It can be stated that studying the behaviour of

as

t approaches infinity is a component of stability analysis. The solution is deemed stable if, when

t grows larger,

approaches a constant value. It is said that the solution is unstable if

has no bound. The term

appears in the expression for

. The sign of

determines the stability. In particular,

When , tends to a constant value, and the term approaches 0 as t approaches infinity. Then tends to . As a result, the solution is stable.

When , grows without bound, and the term also grows without bound as t approaches infinity. As a result, the solution is unstable.

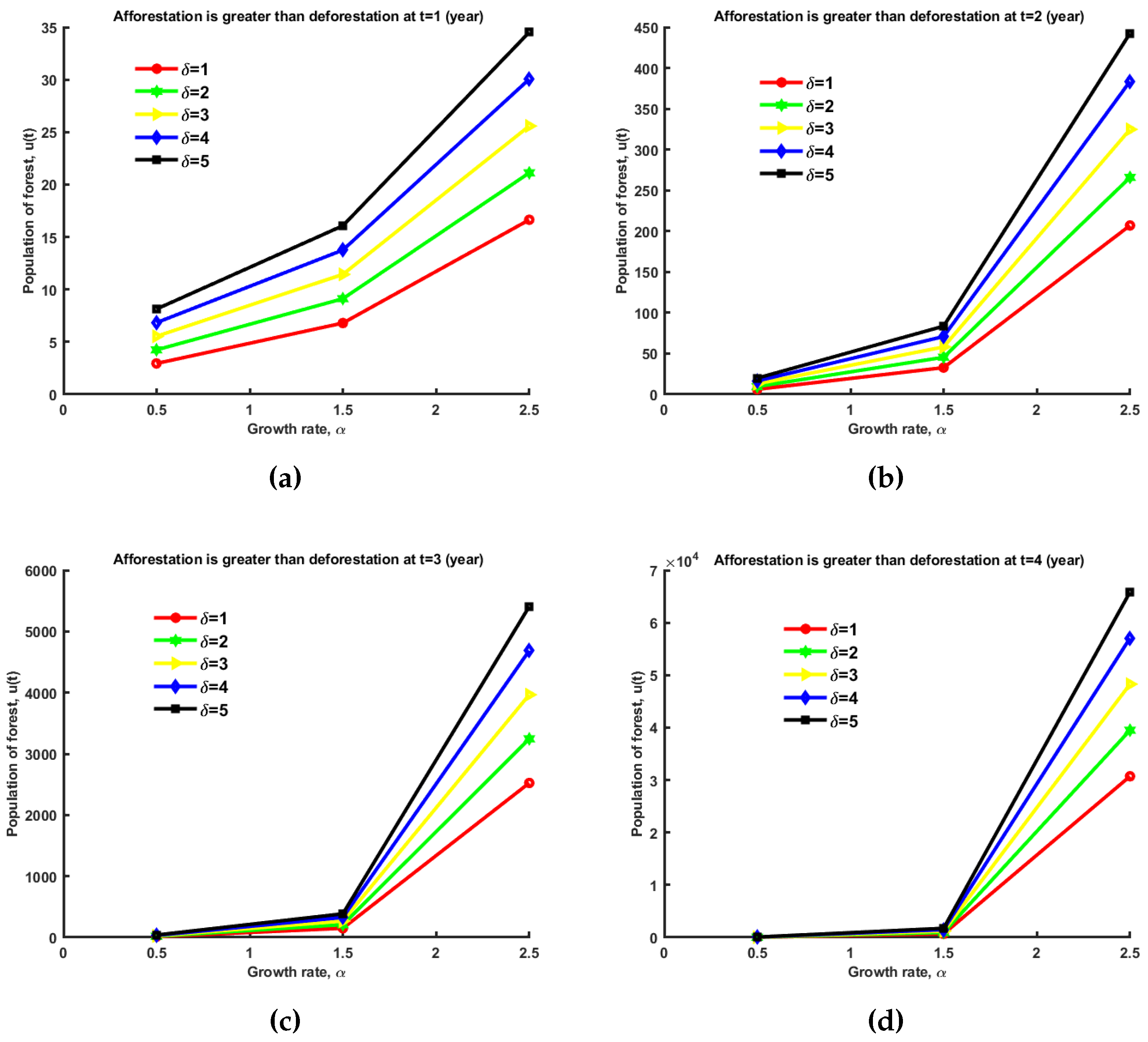

5.1.2. Computational Results for Case 1

We can see variation of forest growth for (3) at and time, in year. We assume data for good results. In the figure, (growth rate) in the x-axis and in the y-axis. In this plot, afforestation is greater than deforestation.

It is evident from the graph in

Figure 1 that if

is continuously increased by one unit, the curve of population of forest,

increases. We can observe that the forest expands quickly if the time interval increases. So, the graphs increases rapidly in (d) compare with (a), (b), (c). We should increase the value of

. Here,

is the difference between afforestation rate and deforestation rate. We should plant more trees to prevent deforestation. Thus, we can conclude that afforestation and the length of time should be increased.

5.2. Case 2: Deforestation is Greater than Afforestation

In our model, we take into account the fact that deforestation outpaces afforestation and examine the impact on forest growth. We consider,

is the population of forest.

The integration yields,

where

and the initial condition is

The stability of the solution depends on the value of

. Let

is the equilibrium point of the differential equation, then we have,

Let,

Putting the value of

u in the equation (9), we get,

Now we have,

Equation (

13) is similar to the original equation (9). So, the solution of (

13) is,

The solution is deemed stable if, when

t grows larger,

approaches a constant value. It is said that the solution is unstable if

has no bound. The term

appears in the expression for

. The sign of

determines the stability. In particular,

When , tends to a constant value, and the term approaches 0 as t approaches infinity. Then tends to . As a result, the solution is stable.

When , grows without bound, and the term also grows without bound as t approaches infinity. As a result, the solution is unstable.

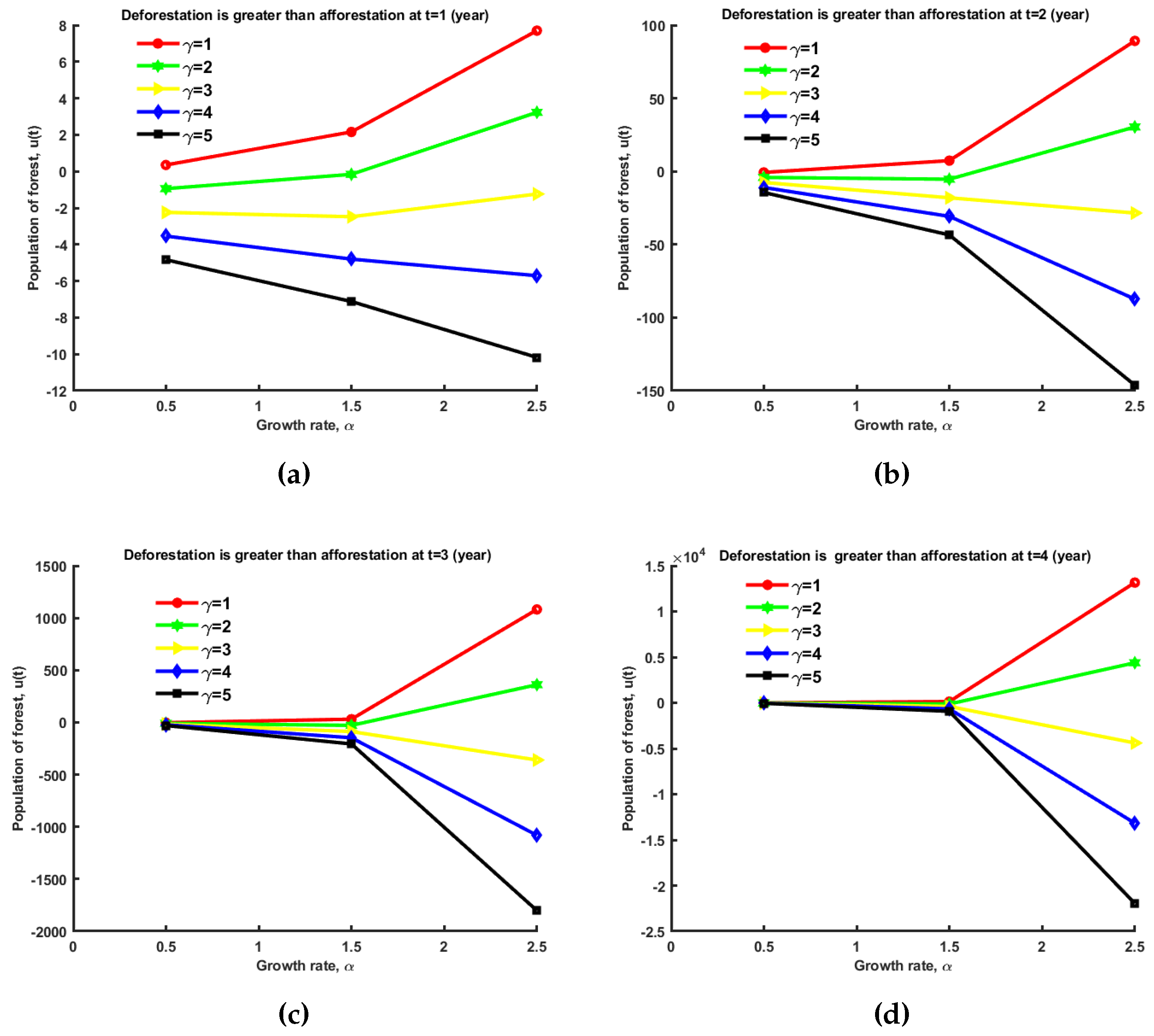

5.2.1. Computational Results for Case 2

We can see variation of forest growth for (

10) at

and time,

in year. In the figure,

(growth rate) in the

x-axis and

in the

y-axis. In this plot, deforestation is greater than afforestation.

It is evident from the graphs in

Figure 2 that in (a) if

is consistently increased by one unit, then

first accelerates in the direction of positive y-axis, then somewhat declines. When

it starts to decrease. Then the curve of population of forest,

changes downhill in the

y-direction’s negative axis. In (b) if

is continuously increased by one unit, then the curve of

first increases in the direction of the positive y-axis, then slightly decreases, and finally turn downward towards the negative y-axis. In (c) and (d)

decreases more rapidly compare with (a) and (b) respectively. Therefore, in order for forests to grow, we must reduce the value of

. Here,

is the difference between deforestation rate and afforestation rate. So, we should prevent deforestation.

5.3. Case 3: Periodic Behavior When Afforestation Is Greater Than Deforestation

In this model afforestation is greater than deforestation and variables

a and

b are time dependent. So

and

.

for

with initial condition,

Integrating Factor,

which implies,

We know that,

Consider

and

. Then we get,

Now,

Again, we can use integration by parts. Now let

and

. Then we get,

So, we can write,

Hence the simplified form is,

So, the integration is,

From (

17) equation, we get,

If

, then

such that,

Putting the value of

C from (

20) in (

19), we have the solution,

The solution

u is a function of

t. Such that

. The stability of the solution depends on the value of

. Consider, the equilibrium point of the differential equation is

. Now we have,

Let,

Putting the value of

u in the equation (

15), we get,

Now we get,

Equation (

23) is similar to the original equation (

15). So, the solution of (

23) is,

We now examine the solution’s stability analysis,

When , the term approaches 0 as t approaches infinity. So, we can say that tends to a finite value as and are bounded when t tends to infinity. As a result, the solution is stable.

When , grows without bound, and the term also grows without bound as t approaches infinity. As a result, the solution is unstable.

When , the differential equation has a periodic solution, after which the term becomes 1. The particular initial conditions determine the stability.

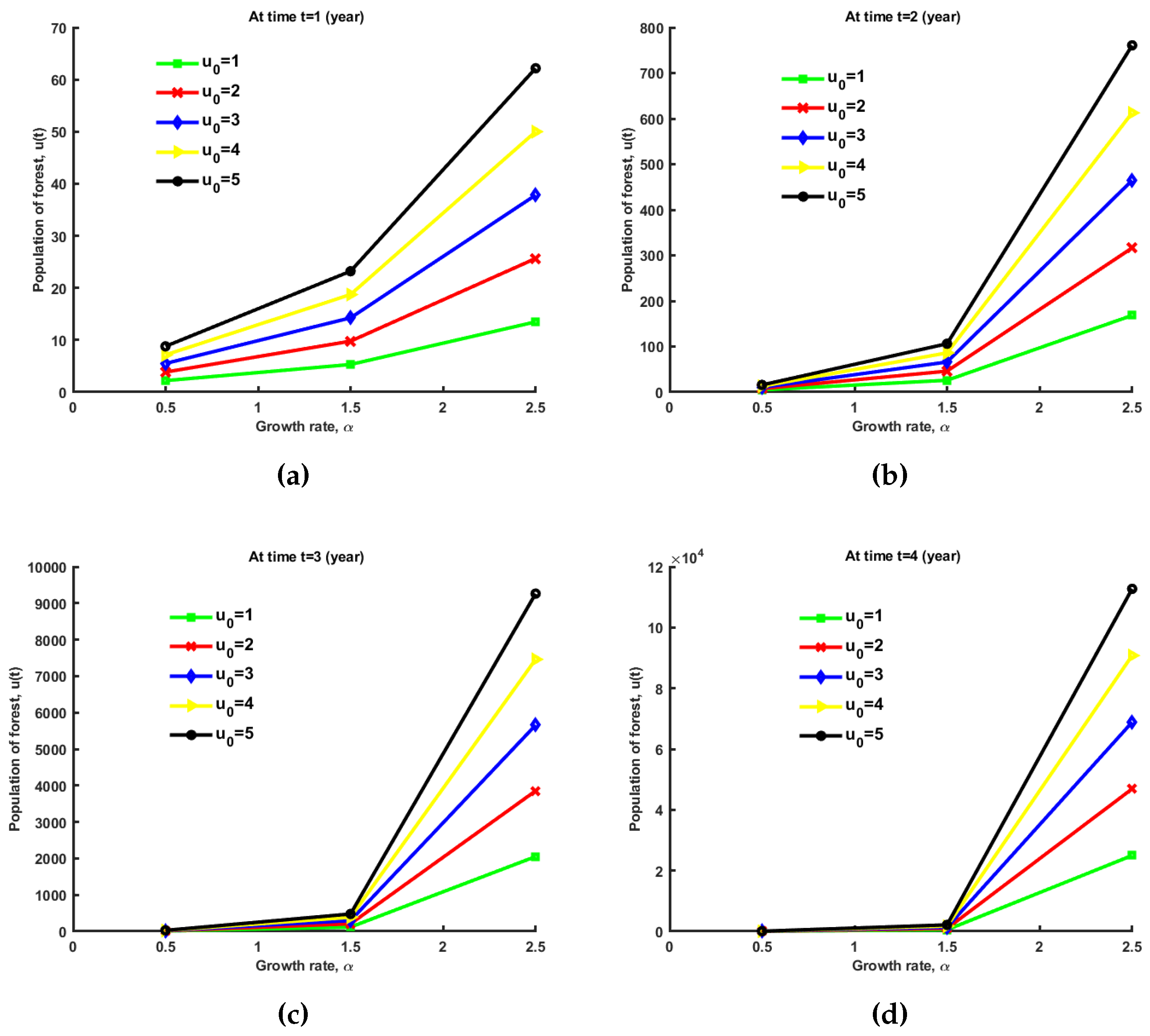

5.3.1. Computational Results for Case 3

In this case afforestation is greater than deforestation and variables

a and

b are time dependent. So

and

. Here,

and

. We can see variation of forest growth for (

21) at

and time,

in year. In the figure,

(growth rate) in the

x-axis and

in the

y-axis.

It is evident from the graph in

Figure 3 that if

is continuously increased by one unit, the curve of population of forest,

increases. We can observe that the forest expands quickly if the time interval increases. So, the graphs increases rapidly in (d) compare with (a), (b), (c). So, we can say that value of forest growth is low if the value of initial condition is small, such as few trees everywhere. We should plant more trees to prevent deforestation. Thus, we can conclude that afforestation, reforestation and the length of time should be increased.

6. How to Minimize the Negative Effects of Deforestation

To stop environmental degradation, a nation’s forestland should make up 25% of its entire land area. But the number is merely 16%. Dangers are pounding at the door. Thus, it is now necessary to consider it and take legal action to stop the trend of deforestation in our nation. Our children are developing in a contaminated atmosphere. Therefore, it is necessary to give the next generation the chance to comprehend the negative effects of deforestation. Local communities, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and civil society organisations ought to step up and collaborate closely with the executive branch. Education and training that raises awareness can be quite important in this process.

Cutting down trees causes massive emissions of the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Growing trees can reduce global warming because they absorb carbon dioxide. Landslides and rock slides, which can occasionally harm people, animals, or cause property damage, are stopped by tree roots. The establishment and upkeep of trees are essential to the community’s overall well-being and standard of living. Trees are regarded for having relaxing and therapeutic properties. We may unwind, get rid of our worries, and revive our strain-weary eyes by simply walking through a forest.

Paper products account for 40% of all timber consumption worldwide, and demand for paper is rising by 2% to 3% annually. This means that more trees are still being used in the paper industry. In the United States, two million trees are cut down every day solely to meet the need for paper. We should make an effort to use less paper, if at all possible. By doing this, we shall decrease our impact on the elimination of trees [

18].

We may contribute as a customer by making sure we only purchase goods that have the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certification, which will help to reduce the demand for more logging, especially illegal logging. The FSC is now the best international standard in the area and provides a framework for interested parties to work towards responsible forest management. Purchasing FSC-certified products achieves two important objectives:

For cooking and home heating, more than two billion people only rely on firewood. The unfortunate reality is that this frequently occurs in less developed places when trees that are already susceptible and close to communities and cities are taken down for fuel before they have a chance to regrow. Due to such poor management, they progressively vanish. We must choose wood from sustainably managed forests that have time to naturally recuperate if we want to start a fire in our fireplace because our excessive consumption has already done a lot of damage to the world’s forests [

18].

Deforestation and other serious environmental problems frequently continue because of a lack of knowledge and understanding of the problem. Even for farmers, better education and awareness are essential. If local farmers are taught how to best manage their property, it will be less need to clear forest area for farming. After all, farmers are the protectors of our soil. By teaching people on the effects of their actions, the quantity of deforestation can be reduced. We must share with our family the steps they can take to halt global deforestation.

Many organisations with a global or regional focus seek to halt deforestation and implement sustainable forestry practises. Some of them are: Conservation International, Amazon Watch, Rainforest Action Network, World Wildlife Fund, Rainforest Alliance, Arbor Day Foundation, Greenpeace and many more.

Reforestation is an additional strategy to reduce deforestation. Here, we present a different model that illustrates the benefits of reforestation. Reforestation is the deliberate planting of trees in areas where forests have disappeared or been drastically reduced. This can include areas where deforestation, wildfires, or other factors have weakened the ecosystem. Worldwide attempts to slow down climate change and protect natural resources depend heavily on reforestation, which is also becoming more and more acknowledged as a key element of sustainable development plans. We’ll talk about reforestation in the next section.

7. Modified Model with Reforestation

The forest is expanding significantly if we take action to reforest areas that have little or no trees because there is more deforestation than afforestation in certain areas.

In the modified model, we introduce new variable

r which denotes rate of reforestation. The deliberate or accidental practice of replanting trees in locations where forests have been destroyed or reduced in size with the objective of recreating or restoring a forest ecosystem is known as reforestation. This approach is necessary to stop deforestation, lessen the effects of climate change, and restore biodiversity. Planting trees where they were previously cut down and creating new forests on cleared or damaged land are the two aspects of reforestation. The growth rate is

, afforestation, reforestation and deforestation occur at constant rates

a,

r and

b, respectively [

20,

21],

for

with initial condition,

The stability of the solution depends on the value of

. Let

is the equilibrium point of the differential equation. Now,

Let,

Putting the value of

u in the equation (26), we get,

Now we have,

Equation (

30) is similar to the original equation (26). So, the solution of (

30) is,

We now examine the solution’s stability analysis,

When , tends to a constant value, and the term approaches 0 as t approaches infinity. Then tends to . As a result, the solution is stable.

When , grows without bound, and the term also grows without bound as t approaches infinity. As a result, the solution is unstable.

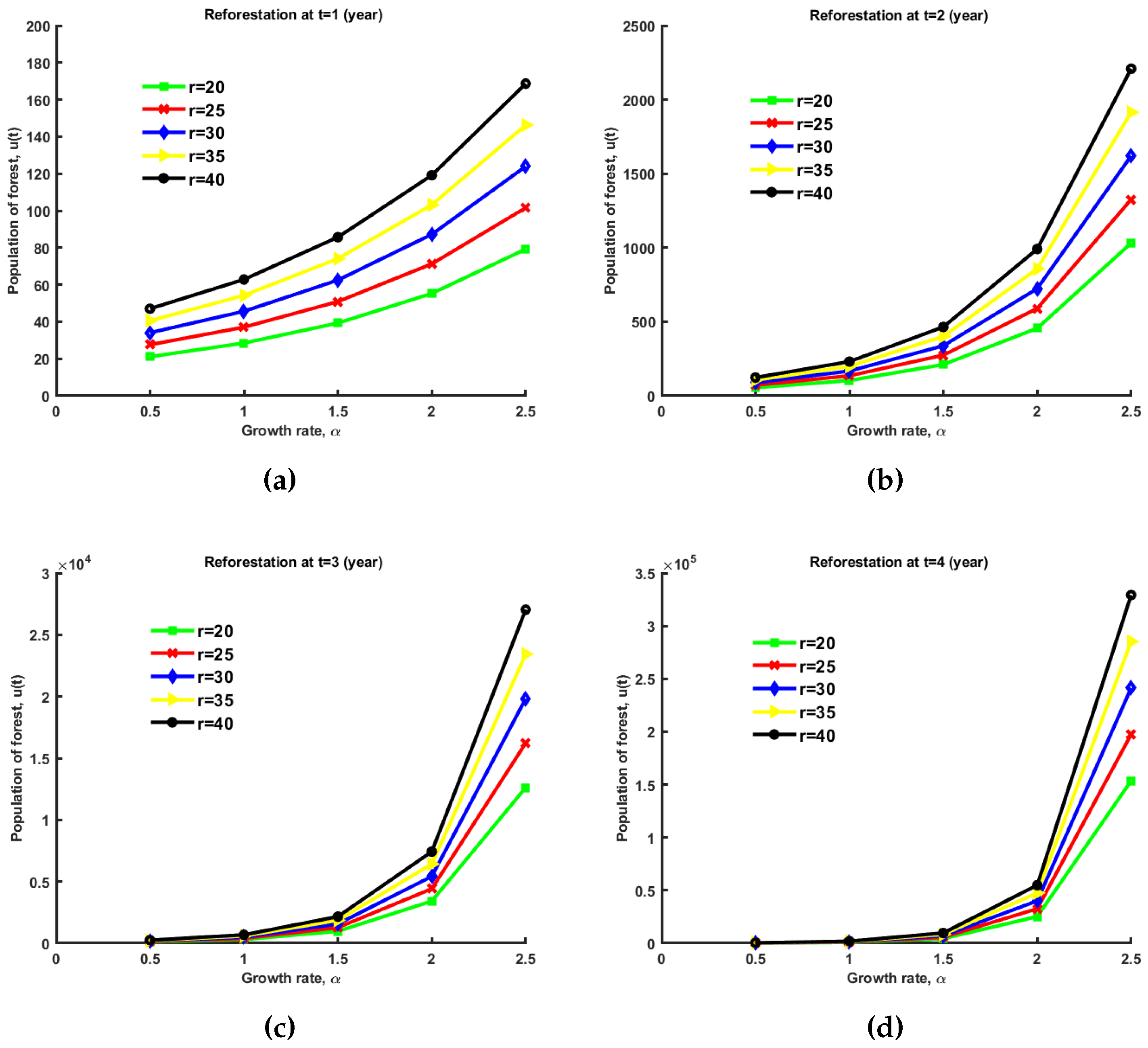

7.1. Computational Results for Reforestation

We can see variation of forest growth for (27) at and time, in year. In the figure, (growth rate) in the x-axis and in the y-axis.

The graph in

Figure 4 makes it clear that in (a) if

r increases and

, then the difference between

r and

also increases. Then the curve of population of forest,

increases. So, the forest expands significantly. Here,

is the difference between deforestation rate and afforestation rate. In (d) the forest expands quickly compare with (a), (b), (c) if the time interval increases. In order to stop deforestation, we should reforest an increasing amount of land and the length of time should be increased.

8. Conclusion

Climate change is the phrase used to describe long-term variations in local, regional, or global temperature patterns. These variations are mostly brought about by human activity, which raises the atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases. These changes have a significant impact on human societies, weather patterns, sea levels, and Earth’s ecosystems. There are multiple ways in which deforestation impacts climate change. Trees act as carbon sinks by absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and storing it in their biomass. When forests are destroyed, carbon is released back into the atmosphere, increasing the amount of greenhouse gases in the environment. We began by outlining Bangladesh’s various forest. We demonstrated the causes of deforestation and its detrimental repercussions in this paper. We used mathematical models to explain the impacts of afforestation, deforestation, and reforestation. We can utilise these mathematical models in any forest on the planet. We solved the models for equilibrium points and developed conditions for stability. We drew figures by using data. The balance of our ecosystem is greatly dependent on trees. Climate change, which is a result of deforestation, is negatively affecting the ecosystem. Therefore, in order to reverse this negative effect, we must plant more trees.

Here, we discuss some directions for further studies of this paper. Such as, To expand this analysis to account for stochastic rather than deterministic behavior, the focus should shift to modeling uncertainties and randomness inherent in the system. Stochastic approaches allow us to incorporate variability in input parameters, external influences, or system responses that deterministic models typically overlook. This can involve probabilistic methods, statistical analysis, or stochastic simulations, depending on the nature of the system and the available data. The analysis could integrate sensitivity assessments to identify which random variables or parameters most significantly impact the results. This could include measures such as variance decomposition or probabilistic sensitivity indices. This paper can also be expanded to focus on both spatial and temporal dimensions, providing a more comprehensive scientific framework through partial differential equation (PDE) analysis. Incorporating space-time dynamics allows for the study of system behaviors as they evolve across spatial domains and over time, enabling a deeper understanding of processes that vary in both dimensions. PDEs provide a robust mathematical framework to model such phenomena, capturing interactions between spatial variations and temporal evolution. For instance, diffusion-reaction equations can be utilized to analyze spatial distributions coupled with dynamic changes, while advection-diffusion models can describe transport phenomena influenced by flow or external forces. Boundary and initial conditions would play a critical role in defining the scope and accuracy of the model.

Data Availability Statement

No human data used in this study.

Acknowledgments

The research by M. Kamrujjaman was partially supported by the University Grants Commission (UGC), and the University of Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| Terms |

Description |

| BFD |

Bangladesh Forest Department. |

| ET |

Evapotranspiration. |

| CHT |

Chittagong Hill Tracts. |

| FAO |

Food and Agriculture Organization. |

| OECD |

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. |

| NGO |

Non-governmental Organizations. |

| FSC |

Forest Stewardship Council Certification. |

References

- Bologna, Mauro, and Gerardo Aquino. Deforestation and world population sustainability: a quantitative analysis. Scientific reports 10, no. 1 (2020): 7631.

- Lawrence, Deborah, Michael Coe, Wayne Walker, Louis Verchot, and Karen Vandecar. The unseen effects of deforestation: biophysical effects on climate. Frontiers in Forests and Global Change 5 (2022): 49. [CrossRef]

- Balboni, Clare, Aaron Berman, Robin Burgess, and Benjamin A. Olken. The economics of tropical deforestation. Annual Review of Economics 15 (2023): 723-754.

- Brown, Sandra, and Daniel Zarin. What does zero deforestation mean? Science 342, no. 6160 (2013): 805-807.

- Seymour, Frances, and Nancy L. Harris. Reducing tropical deforestation. Science 365, no. 6455 (2019): 756-757.

- Garrett, Rachael D., Federico Cammelli, Joice Ferreira, Samuel A. Levy, Judson Valentim, and Ima Vieira. Forests and sustainable development in the Brazilian Amazon: history, trends, and future prospects. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 46 (2021): 625-652.

- Wang, Shaopeng, and Michel Loreau. Ecosystem stability in space: α, β and γ variability. Ecology letters 17, no. 8 (2014): 891-901.

- Bhagwat, Shonil, C. J. Kettle, and L. P. Koh. The history of deforestation and forest fragmentation: a global perspective. Global forest fragmentation 2 (2014): 5-6.

- Grainger, Alan. Controlling tropical deforestation. Routledge, 2013.

- Ratcliffe, D. A. The effects of afforestation on the wildlife of open habitats. Trees and wildlife in the Scottish uplands. Institute of Terrestrial Ecology, Abbots Ripton (1986): 46-54.

- Dietz, Thomas, Rachael L. Shwom, and Cameron T. Whitley. Climate change and society. Annual Review of Sociology 46 (2020): 135-158.

- Tasnim, F. Kamrujjaman Md. Dynamics of Spruce budworms and single species competition models with bifurcation analysis. Biom Biostat Int J 9, no. 6 (2020): 217-222.

- Kamrujjaman, Md, Kamrun Nahar Keya, Ummugul Bulut, Md Rafiul Islam, and Muhammad Mohebujjaman. Spatio-temporal solutions of a diffusive directed dynamics model with harvesting. Journal of Applied Mathematics and Computing 69, no. 1 (2023): 603-630.

- Tasnim, Farah, Md Shah Alam, and Md Kamrujjaman. Forest Dynamics and the Analysis of a Reaction-Diffusion Forest Model. GANIT: Journal of Bangladesh Mathematical Society 43, no. 2 (2023): 26-36.

- Taraqqi-A-Kamal, A. Deforestation in Bangladesh - Issues and Remedies. ResearchGate, January 1, 2006. [CrossRef]

- Hasnat, G. T. , Md Alamgir Kabir, and Md Akhter Hossain. Major environmental issues and problems of South Asia, particularly Bangladesh. Handbook of environmental materials management (2018): 1-40.

- Reza, Ahm Ali, and Md Kamrul Hasan. Forest biodiversity and deforestation in Bangladesh: the latest update. Forest degradation around the world (2019): 1-19. https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/68528.

- Slavikova, Sara Popescu, and Sara Popescu Slavikova. 15 Strategies to Reduce Deforestation | GreenTumble. Greentumble, April 18, 2021. https://greentumble.com/15-strategies-to-reduce-deforestation.

- Chakravarty, Sumit, S. K. Ghosh, C. P. Suresh, A. N. Dey, and Gopal Shukla. Deforestation: causes, effects and control strategies. Global perspectives on sustainable forest management 1 (2012): 1-26.

- Chaudhary, R.A. K. Yadav, S.S. Tomar, S. Kumar. A mathematical model for forest growth. International journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology 5(4) (2020). https://ijisrt.com/a-mathematical-model-for-forest-growth.

- Mangla, Sandhya, Shalini Sharma, Rahul Boadh, and Yogendra Kumar Rajoria. A Mathematical Model of the Impact of Deforestation on the Growth of Forest Resources. Neuroquantology 20, no. 17 (2022): 223. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/365776738_A_Mathematical_Model_of_the_Impact_of_Deforestation_on_the_Growth_of_Forest_Resources.

Figure 1.

Variation of forest growth at , and, where (a) at time (year), (b) at time (year), (c) at time (year), and (d) at time (year).

Figure 1.

Variation of forest growth at , and, where (a) at time (year), (b) at time (year), (c) at time (year), and (d) at time (year).

Figure 2.

Variation of forest growth at , and, where (a) at time (year), (b) at time (year), (c) at time (year), and (d) at time (year).

Figure 2.

Variation of forest growth at , and, where (a) at time (year), (b) at time (year), (c) at time (year), and (d) at time (year).

Figure 3.

Variation of forest growth at and, where (a) at time (year), (b) at time (year), (c) at time (year), (d) at time (year).

Figure 3.

Variation of forest growth at and, where (a) at time (year), (b) at time (year), (c) at time (year), (d) at time (year).

Figure 4.

Variation of forest growth at , , and, where (a) at time (year), (b) at time (year), (c) at time (year), (d) at time (year).

Figure 4.

Variation of forest growth at , , and, where (a) at time (year), (b) at time (year), (c) at time (year), (d) at time (year).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).