Submitted:

15 December 2024

Posted:

16 December 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Method

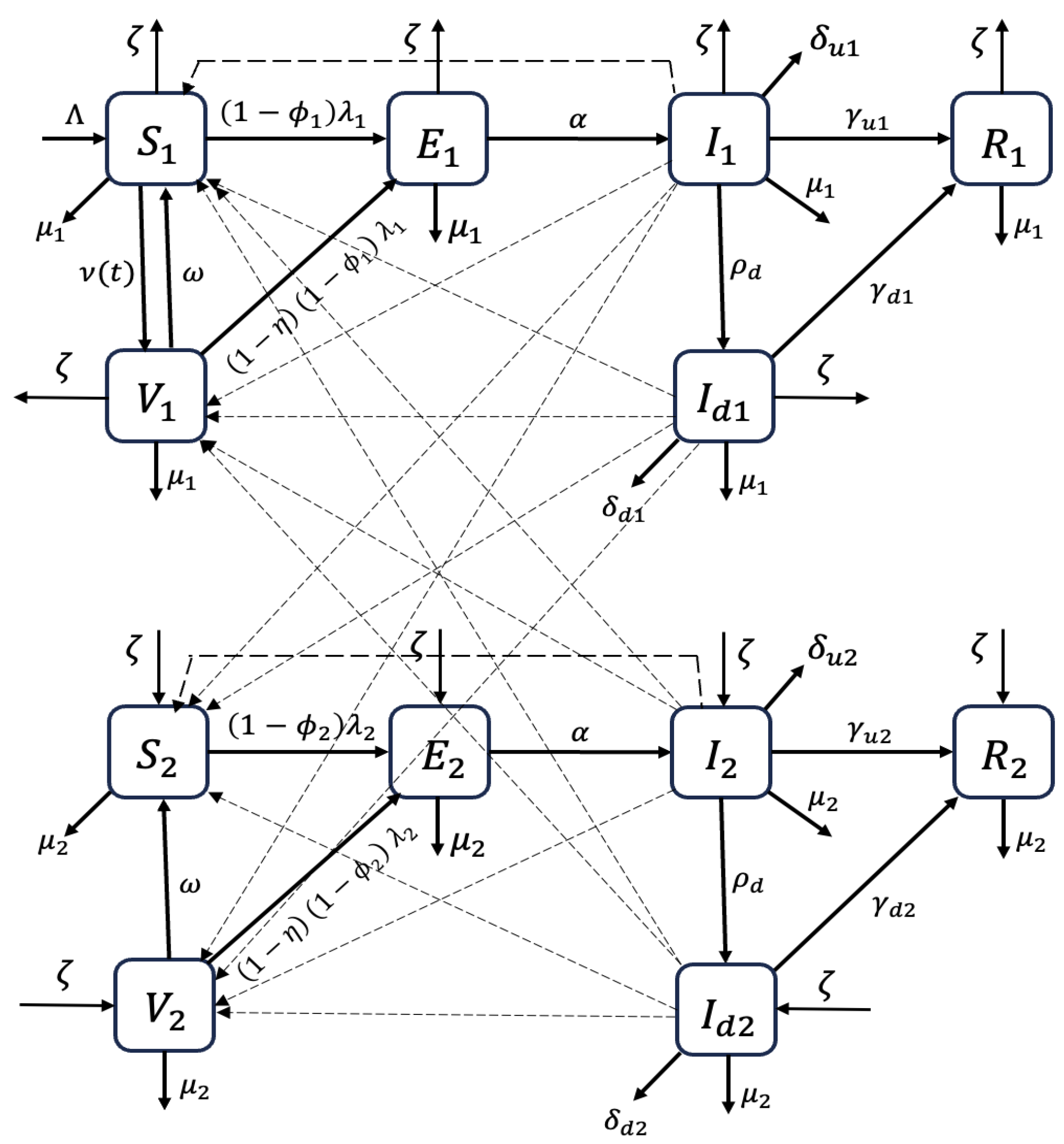

2.1. Model Formulation

- (i)

- Vaccination is administered to under-15 years old individuals that are susceptible. The model doesn’t consider vaccination of detected and confirmed infectious individuals.

- (ii)

- We assume that there is homogeneous mixing among the population, which means that every individual in the community is equally likely to mix and acquire infections from each member when they make contact.

- (iii)

- Since the Mpox outbreak has persisted for a long time, we include the vital dynamics (birth and natural death) in the model.

- (iv)

- The proportion of under-15s in the total Mpox cases remains constant at 0.5 throughout the modeling period.

| State Variable | Description |

|---|---|

| Under 15 (over 15) Susceptible individuals | |

| Under 15 (over 15) Vaccinated individuals | |

| Under 15 (over 15) Exposed individuals | |

| Under 15 (over 15) Infectious individuals | |

| Under 15 (over 15) Detected infectious individuals | |

| Under 15 (over 15) Recovered individuals |

| Parameter | Description | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Birth rate in DRC | ||

| Age-based transition rate | ||

| Natural death rate of under 15 (over 15) individuals | ||

| Vaccination Rate | ||

| Waning rate of the vaccine efficacy | ||

| Vaccine efficacy | dimensionless | |

| () | Percent reduction in the force of infection due to intervention measures (excluding vaccination) and acquired immunity. | dimensionless |

| Transmission rates of under 15 (over 15) infectious individuals | ||

| Transmission rates of under 15 (over 15) detected infectious individuals | ||

| Latent period | ||

| Detection rate of infectious individuals | ||

| Mpox-induced death rate for under 15 (over 15) infectious individuals | ||

| Mpox-induced death rate for under 15 (over 15) detected infectious individuals | ||

| Recovery rate of under 15 (over 15) infectious individuals | ||

| Recovery rate of under 15 (over 15) detected infectious individuals |

| Parameter | Value | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| . | [26] | |

| N | Individuals | [26] |

| [27] | ||

| 0.8 | [28] | |

| Calculated | ||

| () | Calculated | |

| [29] | ||

| (0.004) | Assumed | |

| 0.004 (0.003) | ||

| 1/3.5 (1/3) | Assumed | |

| 1/3 (1/2.5) | [29] |

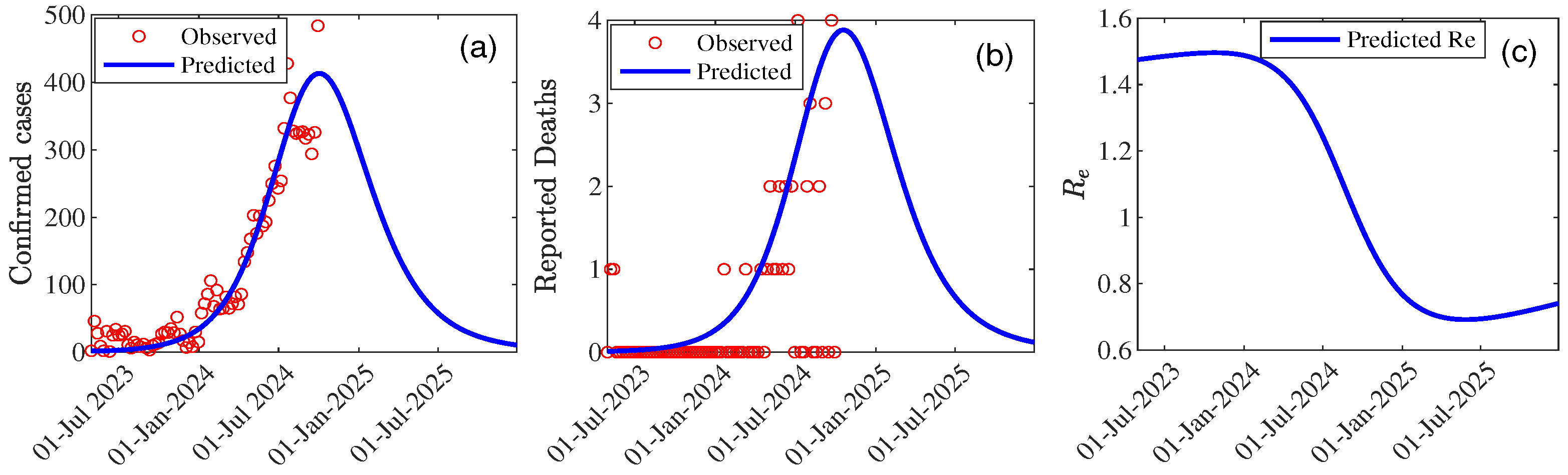

2.2. DRC MPOX Data and Parameter Estimation Procedure

2.2.1. DRC Mpox Data

2.2.2. Model Fiting and Parameter Estimation Procedure

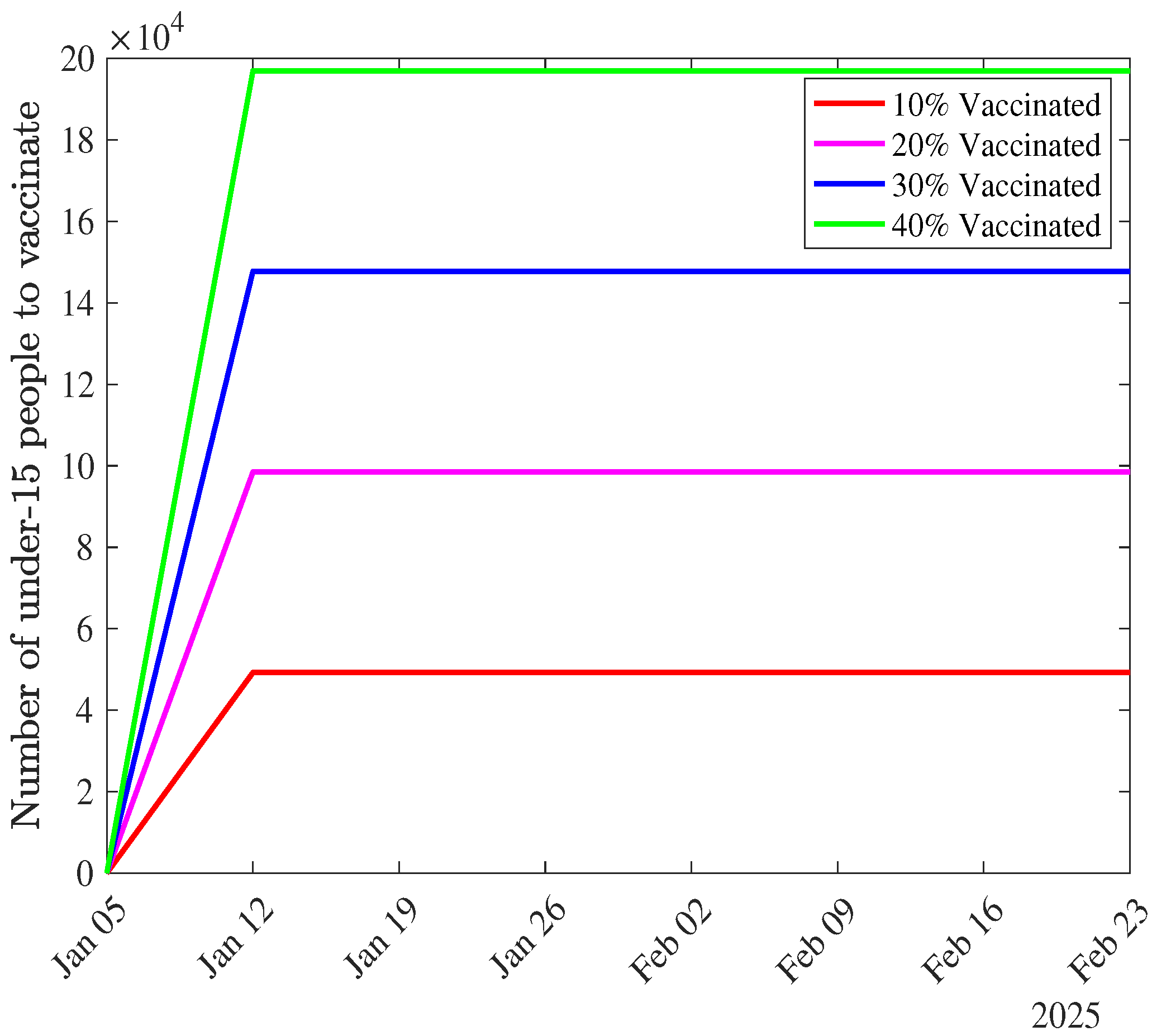

- is start time of the vaccination campaign. Since our modeling period started on April 30, 2023, and we consider the vaccination starting in the second week of January 2025, = 89 weeks).

- is the remaining number of individuals to be vaccinated at time t, calculated as:is the total number of under-15 individuals vaccinated at time t, determined by the ODEs (see equations (1)).

- spreads the vaccination over the remaining weeks in the modeling period.

3. Results

3.1. Analytical Results

3.1.1. Basic and Control Reproduction Numbers

3.1.2. Effective Reproduction

3.2. Stability Analysis of the DFE and Possible Extinction of Mpox

3.3. Numerical Results

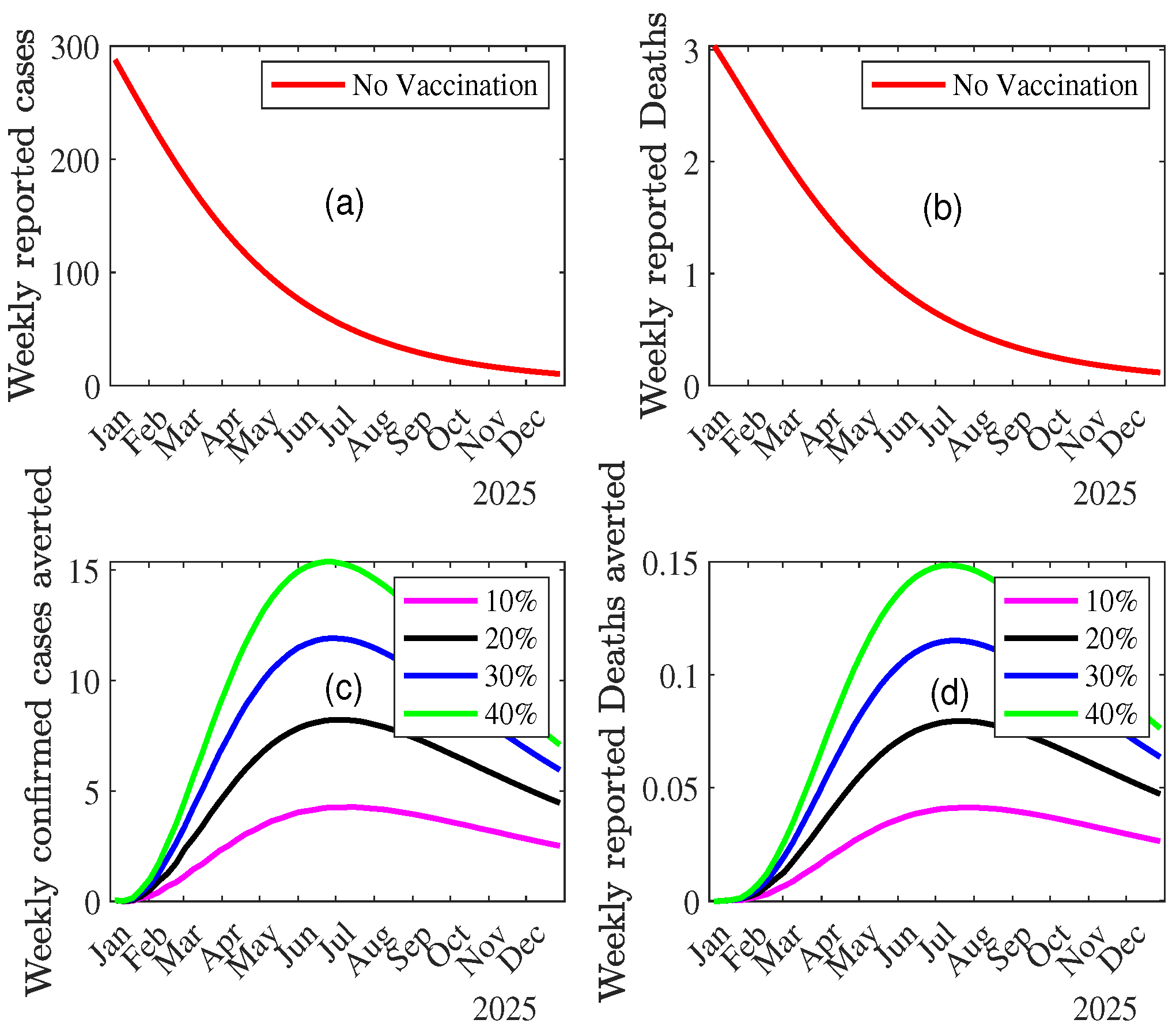

3.3.1. MPOX Dynamics in the Absence of Vaccination

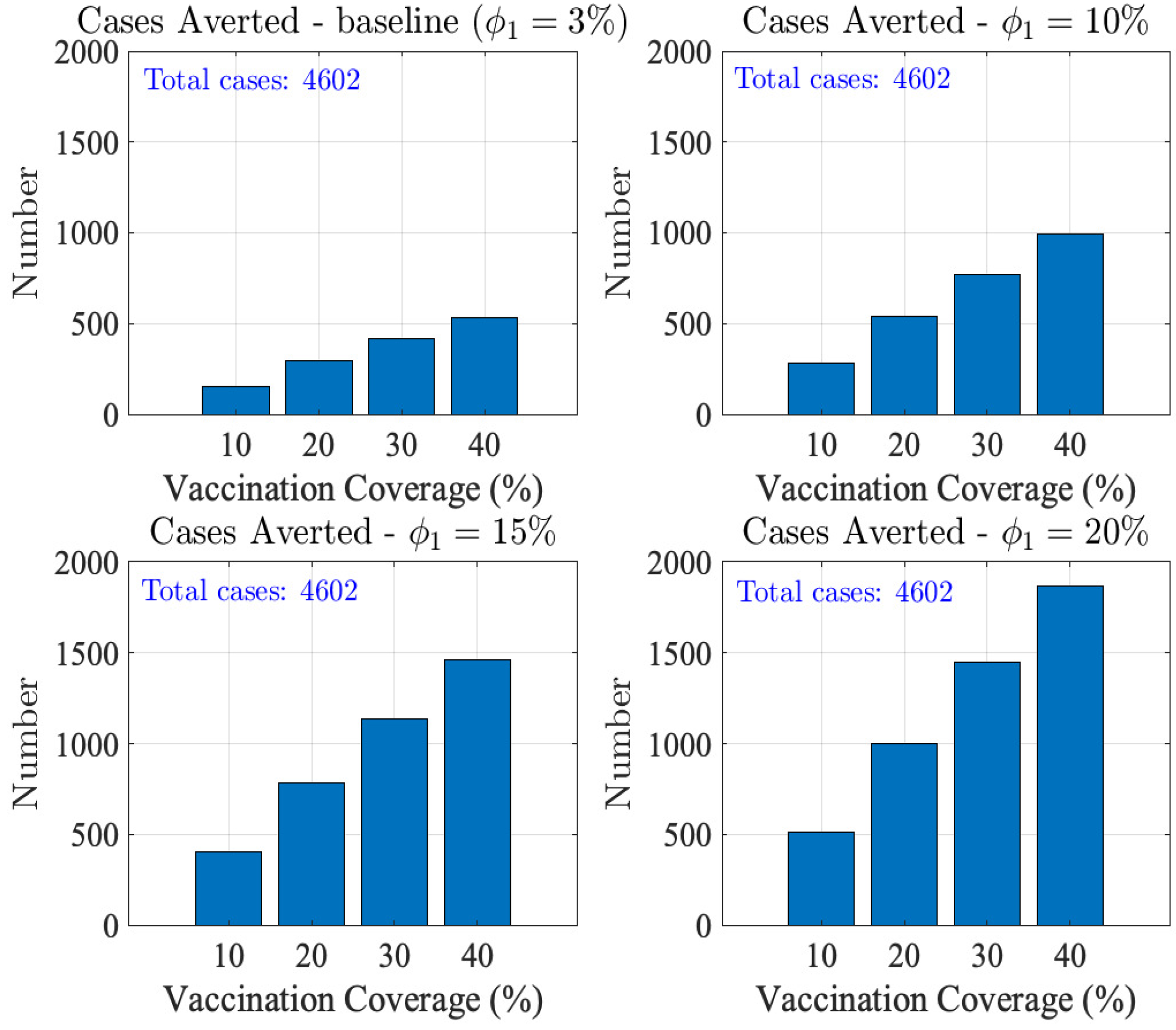

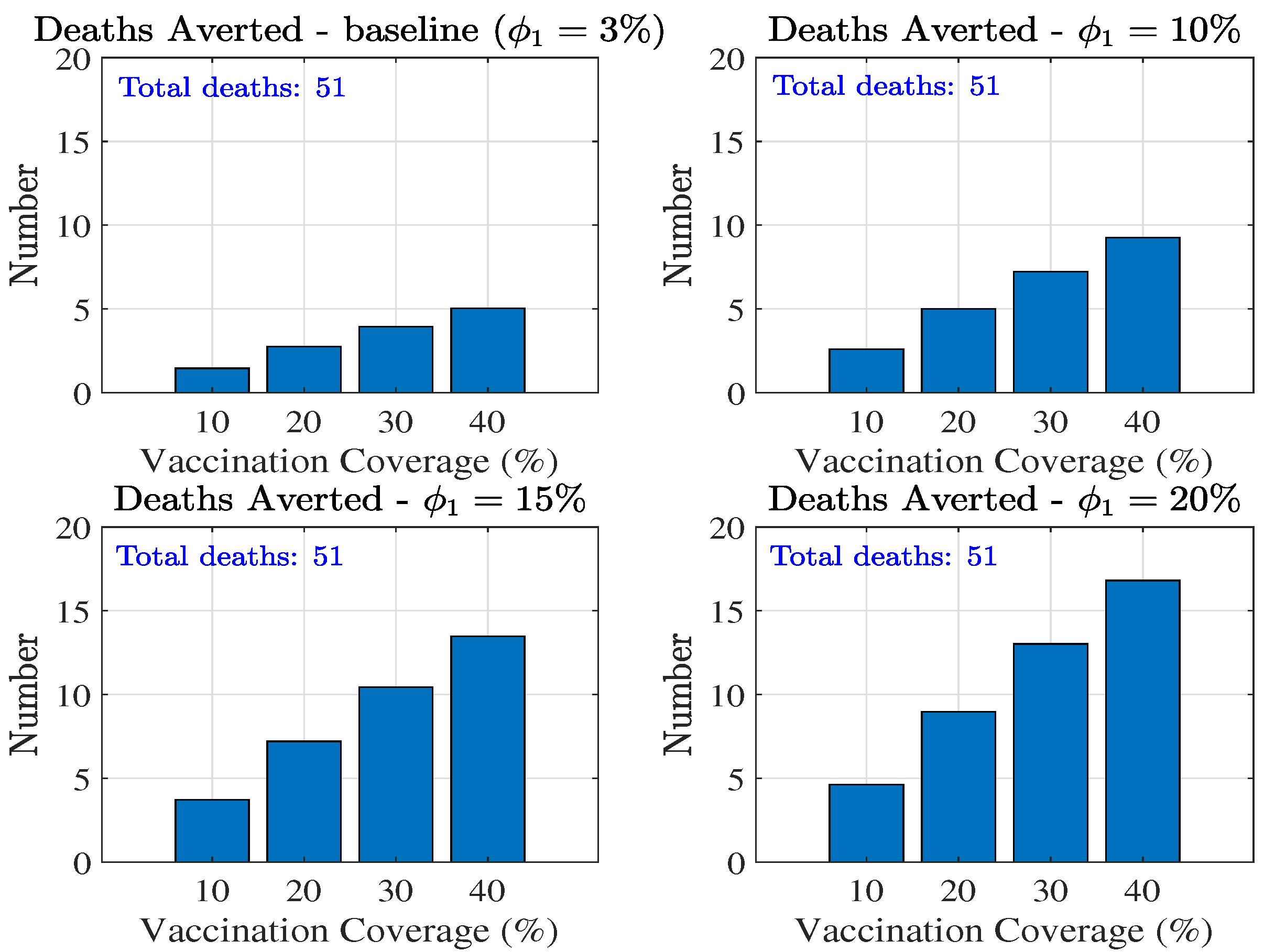

3.3.2. Impact of Vaccination on MPOX Transmission Dynamics

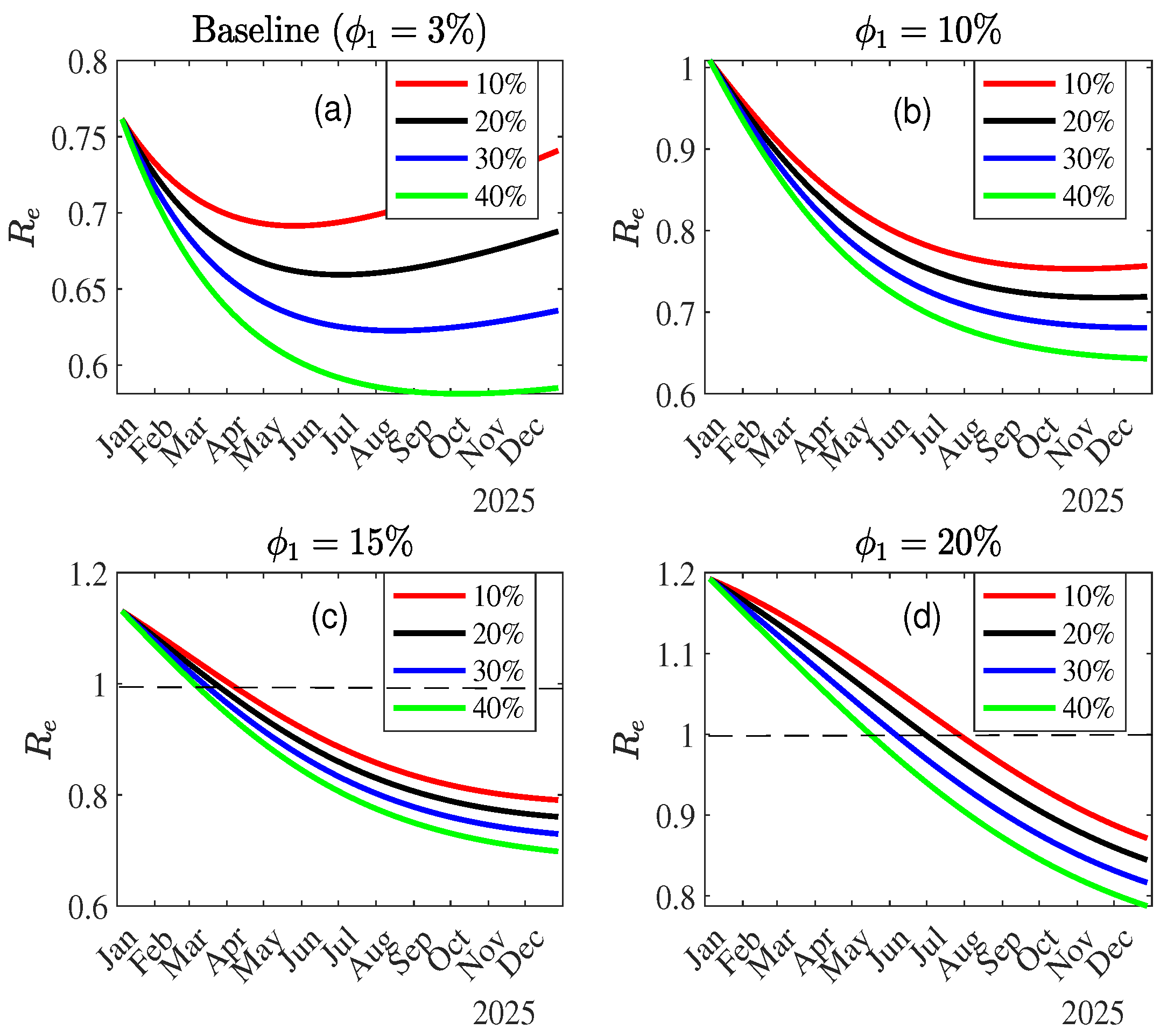

Combined Effect of Vaccination and Increasing Control Measures Levels ()

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Next-Generation Matrix

Appendix B. Distribution of Under-15 s to be Vaccinated According to Vaccination Levels

References

- Liu, B.; Farid, S.; Ullah, S.; Altanji, M.; Nawaz, R.; Wondimagegnhu Teklu, S. Mathematical assessment of monkeypox disease with the impact of vaccination using a fractional epidemiological modeling approach. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 13550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U.S.). What you should know about monkeypox. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/26229. Accessed: 10 Nov 2024.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2021. National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases (NCEZID), Division of High-Consequence Pathogens and Pathology (DHCPP), Monkeypox. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/Monkeypox/index.html. Accessed: 10 Nov 2024.

- Nguyen, P.Y.; Ajisegiri, W.S.; Costantino, V.; Chughtai, A.A.; MacIntyre, C.R. Reemergence of human monkeypox and declining population immunity in the context of urbanization, Nigeria, 2017–2020. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2021, 27, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Emergency Response Team. Multi-country outbreak of mpox, External situation report 29. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/multi-country-outbreak-of-mpox–external-situation-report-30—25-november-2023. Accessed: 10 Nov 2024.

- WHO, Mpox - Democratic Republic of the Congo [Internet]. 2024 [accessed October 31, 2024]. https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2024-DON522. Accessed: 10 Nov 2024. 31 October.

- World Health Organization, 2022-23 Mpox (Monkeypox) Outbreak. Global Trends [Internet]. [cited 2023 Sep 14]. https://worldhealthorg.shinyapps.io/mpx_global//#2_Global_situation_update. Accessed: 10 Nov 2024.

- Whittles, L.K.; Mbala-Kingebeni, P.; Ferguson, N.M. Age-patterns of severity of clade I mpox in historically endemic countries. medRxiv 2024, pp. 2024–04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, T.; Lancaster, K.; Rosengarten, M. A model society: maths, models and expertise in viral outbreaks. Critical Public Health 2020, pp. 253–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, O.J.; Abidemi, A.; Ojo, M.M.; Ayoola, T.A. Mathematical model and analysis of monkeypox with control strategies. The European Physical Journal Plus 2023, 138, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, O.J.; Kumar, S.; Kumari, N.; Oguntolu, F.A.; Oshinubi, K.; Musa, R. Transmission dynamics of Monkeypox virus: a mathematical modelling approach. Modeling Earth Systems and Environment 2022, pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Peter, O.J.; Madubueze, C.E.; Ojo, M.M.; Oguntolu, F.A.; Ayoola, T.A. Modeling and optimal control of monkeypox with cost-effective strategies. Modeling Earth Systems and Environment 2023, 9, 1989–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allehiany, F.; DarAssi, M.H.; Ahmad, I.; Khan, M.A.; Tag-Eldin, E.M. Mathematical modeling and backward bifurcation in monkeypox disease under real observed data. Results in Physics 2023, 50, 106557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Mesady, A.; Adel, W.; Elsadany, A.; Elsonbaty, A. Stability analysis and optimal control strategies of a fractional-order monkeypox virus infection model. Physica Scripta 2023, 98, 095256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adel, W.; Elsonbaty, A.; Aldurayhim, A.; El-Mesady, A. Investigating the dynamics of a novel fractional-order monkeypox epidemic model with optimal control. Alexandria Engineering Journal 2023, 73, 519–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasisi, N.; Akinwande, N.; Oguntolu, F. Development and exploration of a mathematical model for transmission of monkey-pox disease in humans. Mathematical Models in Engineering 2020, 6, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omame, A.; Han, Q.; Iyaniwura, S.A.; Ebenezer, A.; Bragazzi, N.L.; Wang, X.; Kong, J.D.; Woldegerima, W.A. Understanding the impact of HIV on mpox transmission in an MSM population: a mathematical modeling study. Infectious Disease Modelling 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabiu, M.; Dansu, E.J.; Mogbojuri, O.A.; Idisi, I.O.; Yahaya, M.M.; Chiwira, P.; Abah, R.T.; Adeniji, A.A. Modeling the sexual transmission dynamics of mpox in the United States of America. The European Physical Journal Plus 2024, 139, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiridou, M.; Miura, F.; Adam, P.; Op de Coul, E.; de Wit, J.; Wallinga, J. The fading of the mpox outbreak among men who have sex with men: a mathematical modelling study. The Journal of infectious diseases 2024, 230, e121–e130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Guo, X.; Zhao, Z.; Abudunaibi, B.; Zhao, Y.; Rui, J.; Wang, Y.; Song, W.; Wei, H.; Chen, T. Possibility of mpox viral transmission and control from high-risk to the general population: a modeling study. BMC Infectious Diseases 2023, 23, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, S.P.; Cavallaro, M.; Cumming, F.; Turner, C.; Florence, I.; Blomquist, P.; Hilton, J.; Guzman-Rincon, L.M.; House, T.; Nokes, D.J.; others. The role of vaccination and public awareness in forecasts of Mpox incidence in the United Kingdom. Nature Communications 2023, 14, 4100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clay, P.A.; Pollock, E.D.; Saldarriaga, E.M.; Pathela, P.; Macaraig, M.; Zucker, J.R.; Crouch, B.; Kracalik, I.; Aral, S.O.; Spicknall, I.H. Modeling the impact of prioritizing first or second vaccine doses during the 2022 mpox outbreak. medRxiv 2023, pp. 2023–10.

- Bhunu, C.P.; Mushayabasa, S.; Hyman, J. Modelling HIV/AIDS and monkeypox co-infection. Applied Mathematics and Computation 2012, 218, 9504–9518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Africa CDC congratulates the Democratic Republic of the Congo on launching Mpox vaccination campaign. https://africacdc.org/news-item/africa-cdc-congratulates-democratic-republic-of-the-congo-on-launching-mpox-vaccination-campaign. Accessed: 10 Nov 2024.

- World Health Organization, Democratic Republic of the Congo Health data overview for the Democratic Republic of the Congo [Internet]. [cited 2022]. https://data.who.int/countries/180. Accessed: 10 Nov 2024.

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2024). World Population Prospects 2024. New York: United Nations. https://population.un.org/wpp/. Accessed: 10 Nov 2024.

- Collier, A.r.; McMahan, K.; Jacob-Dolan, C.; Liu, J.; Borducchi, E.; Moss, B.; Barouch, D.H. Rapid Decline of Mpox Antibody Responses Following MVA-BN Vaccination. medRxiv 2024, pp. 2024–09.

- Berry, M.T.; Khan, S.R.; Schlub, T.E.; Notaras, A.; Kunasekaran, M.; Grulich, A.E.; MacIntyre, C.R.; Davenport, M.P.; Khoury, D.S. Predicting vaccine effectiveness for mpox. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 3856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunge, E.M.; Hoet, B.; Chen, L.; Lienert, F.; Weidenthaler, H.; Baer, L.R.; Steffen, R. The changing epidemiology of human monkeypox—A potential threat? A systematic review. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 2022, 16, e0010141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honfo, S.H.; Taboe, H.B.; Kakai, R.G. Modeling COVID-19 dynamics in the sixteen West African countries. Scientific African 2022, 18, e01408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ASSOCIATED PRESS, Japan pledges to donate 3 million doses of Mpox vaccine to the Democratic Republic of the Congo. https://apnews.com/article/50dbd1f75a4bb61ceeefcb9bbeb95314. Accessed: 10 Nov 2024.

- Taboe, H.B.; Pilyugin, S.S.; Ngonghala, C.N. Resolve Lassa Fever Persistence: A Compartmental Model with Environmental Virus-Host-Vector Interaction. 2024.

| Parameter | Value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| 0.813 | [0.729 , 0.897] | |

| 1.590 | [1.584 , 1.596] | |

| 0.312 | [0.305 , 0.320] | |

| 0.813 | [0.800 , 0.830] | |

| 0.587 | [0.580 , 0.594] | |

| 0.0001 | [0 , 0.0006] | |

| 0.034 | [0.032 , 0.037] | |

| 0.696 | [0.695 , 0.697] | |

| Peak Time | 75 (29/09/2024) | [74.69 , 75.30] |

| Peak Size | 410.62 | [0 , 1085.85] |

| 1.73 | [1.71 , 1.74] | |

| 1.48 | [1.47 , 1.48] | |

| 0.76 | [0.75 , 0.76] | |

| 208.16 | - | |

| 29.06 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).