1. Introduction

People with advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage 4-5 including dialysis (D) experience multiple symptoms due to both the disease and its treatment. These symptoms, including but not limited to fatigue, sleep disorders, anxiety, pruritus and nausea, are described as ‘symptom burden’, which not only have adverse effects on health-related quality of life (HRQOL) amongst patients with CKD stage 4-5D, but also have great impact on their clinical outcomes [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Of the myriad of symptoms experienced by patients with advanced CKD, fatigue is one of the most prevalent and debilitating symptoms [

6,

7].

Fatigue is a complex, multidimensional symptom, comprising both physical and psychological aspects. Fatigue is generally described as ‘extreme and persistent tiredness, weakness or exhaustion physically, psychologically or both [

6,

7]. Fatigue is a subjective symptom, encompassing both decreased performance on motor and cognitive tests and perceived fatigue, as assessed by patient-reported measures [

10]. The awareness of fatigue may take place in the insula. When the body is in a state of debilitation, internal signals are released by tissues of the body and transmitted to the insula, triggering a sensation of fatigue. Moreover, fatigue is indicative of a decline in the capacity for self-motivated behavior, hampering work tasks or exercise routines. It may involve a reduced response of the ventral striatum to rewards and damage to fronto-striatal circuits due to inflammation [

11].

The prevalence of fatigue in patients with CKD stage 4-5D varies from 42% to as high as 97% depending on assessment tools and treatment regimen [

2,

8,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16], while the equivalent figure in the general population is only 5%-7% [

17]. A large cohort study in the Netherlands found that a higher proportion of participants with compared to without CKD had chronic fatigue (22% versus 10%), of whom 31% versus 15% had severe fatigue [

18]. With the progress of CKD, the prevalence of fatigue increases [

19,

20,

21]. Unfortunately, the burden of fatigue even persists in 40%-59% of the kidney transplant recipients, with an average estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of about 45 mL/min/1.73m [

22,

23,

24]. Fatigue causes patients to reduce their daily activities and is associated with higher unemployment [

25,

26,

27]. Moreover, fatigue is associated with adverse outcomes such as mortality, hospitalization and dialysis initiation [

28,

29,

30,

31].

However, despite the high burden of fatigue in patients with CKD stage 4-5D, which is a critical factor for poor outcomes, there is no consensus regarding the risk factors for fatigue [

32]. Accordingly, the purpose of this narrative review is to present and summarize risk factors affecting the prevalence, severity and progress of fatigue in patients with CKD stage 4-5 and dialysis separately. By determining which factors affect fatigue in patients with CKD stage 4-5D, effective intervention can be developed, which will improve their health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and reduce adverse outcomes.

2. Measurement of Fatigue

Reliable measurement of fatigue is a key step for establishing prevalence, identifying risk factors, enabling a clear determination of intervention efficacy and improving outcomes in patients with CKD stage 4-5D. However, due to the different definitions of fatigue, there is no consensus on the best tool to measure this multifaceted symptom. Ju

et al. [

32] found that 45 different tools were applied in 140 studies among CKD and hemodialysis (HD) patients. Most studies used a Likert scale to calculate score of fatigue. Notable, not all measures were developed specifically for fatigue, as some also evaluate broader outcomes, such as HRQOL and CKD-related symptoms.

The 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) is the most widely used tool to measure generic HRQOL, including fatigue, which shows excellent internal consistency, structural and discriminant validity, especially in dialysis patients [

33]. It is designed to assess eight domains of HRQOL, with the vitality scale being one of its components that comprises four items to evaluate fatigue. Therefore, it is easily comprehensible and can be completed rapidly. The limitation of SF-36 vitality scale is that it may not show other negative aspects of fatigue such as weakness, loss of concentration and a less motivated state [

6]. The shortened SF-12, covers the same domains as the SF-36. Due to the smaller number of items (the entire scale 12

vs 36, the vitality scale 1

vs 4), SF-12 is generally easier to complete than SF-36. Nonetheless, it may sacrifice some details and depth [

34].

The Kidney Disease Quality of Life Short Form (KDQOL-SF), designed for assessing the HRQOL in patients with CKD [

35], provides precise insights but is impractical due to its length [

33].

The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (FACIT-F) has strong correlations with the Piper Fatigue Scale (PFS), and both scales are reliable to capture different dimensions of fatigue. However, the FACIT-F may not explain daytime fatigue [

36], while the original PFS is too long to complete [

37].

The 30-item Dialysis Symptom Index (DSI) can measure

valid and reliable kidney disease specific symptoms and its burden. Since 2018 the combined SF-12 and DSI have been used in Dutch dialysis care and recently also in CKD stage 4-5 [

38,

39].

The Standardized Outcomes in Nephrology-Hemodialysis Fatigue (SONG-HD Fatigue) is valid for HD patients, yet it lacks studies in patients with CKD [

40]. These tools provide diverse options, each with strengths and limitations, for fatigue assessment in patients with CKD stage 4-5D.

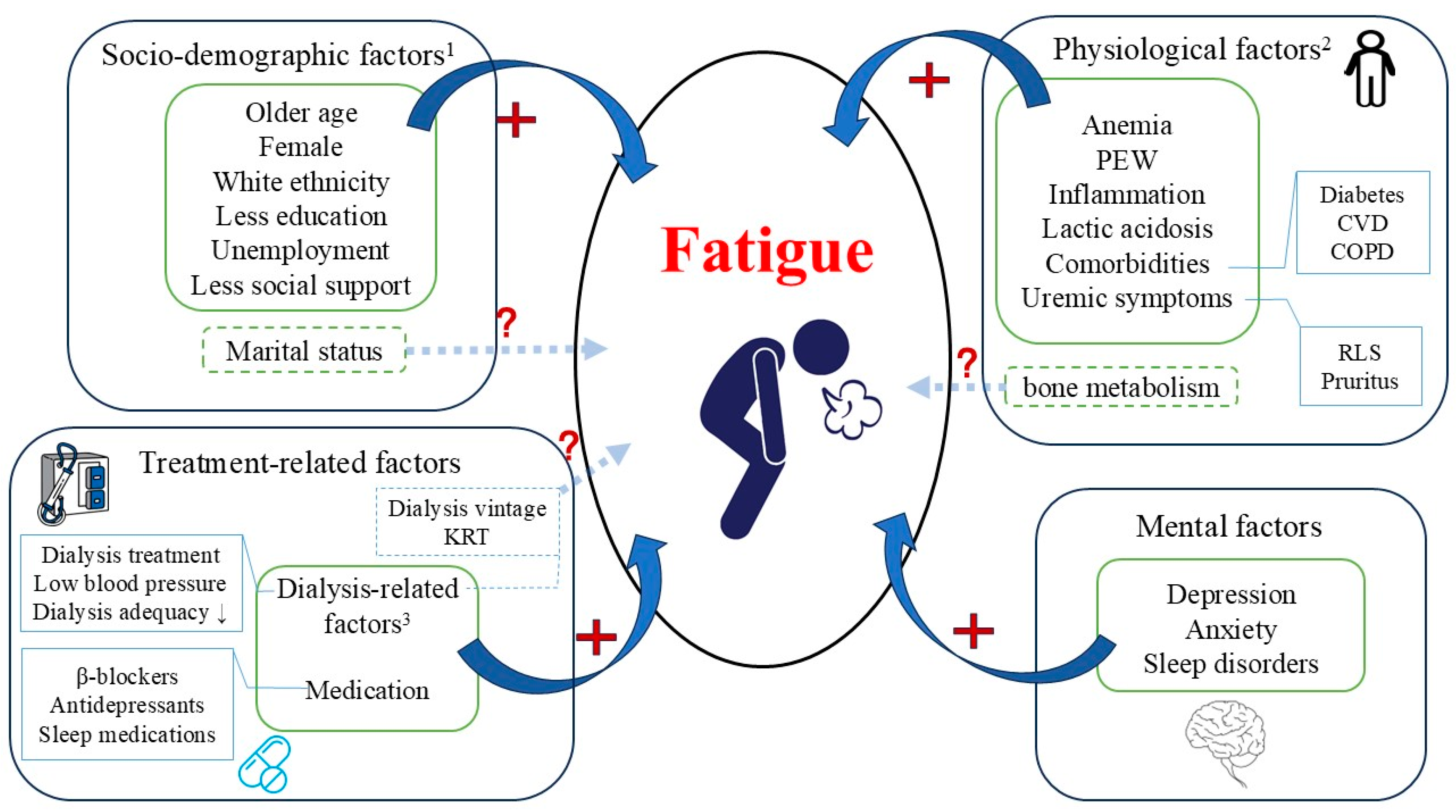

Figure 1.

Risk factors for fatigue in patients with advanced CKD. Abbreviations: PEW, protein energy wasting; BP, blood pressure; CVD, cardiovascular disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; RLS, restless legs syndrome; KRT, kidney replacement therapy. Risk factors related with fatigue can be categorized as socio-demographic factors, physiological factors, mental factors and treatment-related factors. 1Socio-demographic factors: the relation between marital status and fatigue was vague. 2Physiological factors-bone metabolism: evidence regarding the relation between hyperparathyroidism and fatigue is weak. A positive relation between elevated levels of 25(OH) vitamin D and fatigue was observed exclusively among patients >65 years. 3Dialysis-related factors: limited evidence to support the relation between types of KRT and fatigue; the relation between dialysis vintage and fatigue is conflicting.

Figure 1.

Risk factors for fatigue in patients with advanced CKD. Abbreviations: PEW, protein energy wasting; BP, blood pressure; CVD, cardiovascular disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; RLS, restless legs syndrome; KRT, kidney replacement therapy. Risk factors related with fatigue can be categorized as socio-demographic factors, physiological factors, mental factors and treatment-related factors. 1Socio-demographic factors: the relation between marital status and fatigue was vague. 2Physiological factors-bone metabolism: evidence regarding the relation between hyperparathyroidism and fatigue is weak. A positive relation between elevated levels of 25(OH) vitamin D and fatigue was observed exclusively among patients >65 years. 3Dialysis-related factors: limited evidence to support the relation between types of KRT and fatigue; the relation between dialysis vintage and fatigue is conflicting.

3. Risk Factors

3.1. Socio-Demographic Factors

3.1.1. Age

A large number of studies showed that higher age was associated with higher prevalence and severity of fatigue in patients with CKD stage 4-5D and kidney transplant recipients [

15,

24,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51]. Nonetheless, a study involving 266 patients with CKD with a mean age of 64±12 years, 56% of whom had CKD stage 4-5, demonstrated that higher age was not associated with fatigue on any fatigue scale [

28]. Similarly, contradictory results were found in dialysis patients. Among 123 hemodialysis patients, Zakariya

et al. [

52] reported a U-shaped relation between age and fatigue, showing that those between 31-40 of age group were less likely to suffer fatigue compared with those younger than 30 or older than 40 years.

3.1.2. Sex

Multiple studies showed that fatigue was more frequent present in women than in men [

41,

44,

50,

52,

53,

54]. A possible explanation is that men are more likely to deny physical weakness or adopt strategies that may affect the prevalence and severity of fatigue [

55,

56]. In addition, women seem to be more sensitive to symptoms compared with men [

1]. Nevertheless, some studies found no relation between fatigue and sex [

51,

57,

58,

59,

60].

3.1.3. Ethnicity

In 148 patients with CKD stage 4-5, Gregg

et al. [

28] found no association between fatigue and different ethnicities (white, black or other). However, in dialysis patients and kidney transplant recipients, those with a white ethnicity compared with black or Asian/Pacific Islander patients, experience more severe fatigue [

4,

24,

45,

57,

58,

61,

62]. This relation may be influenced by cultural factors, differences in healthcare experiences and social support [

57,

63]. For example, a study found that black patients scored higher than nonblack patients in terms of social support and spiritual beliefs, which may cause patients report fewer symptoms [

64].

3.1.4. Education

There is evidence that less education is related with higher level of fatigue in HD patients [

46,

47,

48,

49,

52,

65], which might be attributed to low health literacy with insufficient self-management [

66,

67]. Those who received higher level of education may understand their condition better and are more compliant to therapy [

68]. Patients with low level of education may find it difficult to retrieve relevant health information [

69], experience difficulty in enhancing symptom management and recognizing the importance of alleviating fatigue [

70].

3.1.5. Employment

A study found that employed compared with unemployed patients with CKD stage 4-5 had an about 50% lower risk to suffer from fatigue [

28]. The inverse relation between fatigue and employed status was similar in dialysis patients [

15,

44,

49,

65,

71,

72]. Unemployed compared with employed patients might be more focused on their disease without the distraction of a job. Despite studies identifying unemployment as a risk factor for fatigue, it is also plausible that fatigue, in turn, may have a negative impact on working will [

15].

3.1.6. Marital Status

Findings related to marital status were inconsistent in dialysis patients. Some studies showed that single compared with married patients had the lowest levels of fatigue in both HD and peritoneal dialysis (PD) [

49,

51]. Another study conducted in HD patients showed that divorced or widowed patients suffered more from fatigue than married or single patients [

48]. However, marital status did not show any protective effect among HD patients in other studies conducted in Asia [

60,

71]. An explanation may be that in the Asian compared with American culture it is more common that family members take care of each other even after divorce [

73].

3.1.7. Social Support

High level of social support is another crucial factor associated with less fatigue in HD patients and kidney transplant recipients [

9], albeit most of the studies were small, including less than 100 patients. Social support might be a modifiable psychosocial factor of great importance for survival [

74], meanwhile, Akin

et al. [

49] found that as levels of loneliness and fatigue increased, the self-care abilities of HD patients were worse.

3.2. Physiological Factors

3.2.1. Anemia

Data from previous studies conducted in patients with CKD stage 4-5 suggested that anemia was related with higher levels of fatigue [

28,

75]. Also, a positive relation between fatigue and anemia was found in several studies including both HD and PD patients [

4,

50,

75]. In contrast, some studies did not find any relation between hemoglobin (Hb) level and fatigue in dialysis patients [

44,

47,

51,

59]. Deficiency of iron may be a confounding factor. Motonishi

et al. [

76] reported that iron deficiency was identified as a risk factor regarding severity of fatigue even without anemia.

Anemia is a risk factor for fatigue due to decreased arterial oxygen carrying capacity and impaired total body oxygen delivery [

77]. The 2012 Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guideline about anemia provided recommendations on the hemoglobin targets in patients with CKD stage 4-5D. It advised that Hb concentration should not exceed 11.5 g/dL, while it also pointed that patients may have improvements in HRQOL at Hb concentration ranges from 11.5-13.0 g/dL [

78]. According to Guedes

et al. [

79], achieved Hb higher or equal than 13g/dL compared to lower than 13g/dL on follow-up demonstrated a relatively larger reduction in fatigue (effect sizes: 0.21 [95% CI: 0.08–0.35] vs. 0.09 [95% CI: 0.02–0.16]). Nevertheless, most of the evidence is poor [

78,

80]. Among patients with CKD stage 4, a study revealed that a target Hb of 13.5 g/dL was associated with increased risk of CVD, progression to renal replacement therapy (RRT) and hospitalization for RRT [

81]. Interestingly, a previous study reported that the optimal target hemoglobin level in kidney transplant recipients may be up to 12.5-13.0 g/dL which is higher than recommended in CKD [

82], as cardiovascular mortality and morbidity may increase when this critical value is exceeded [

83].

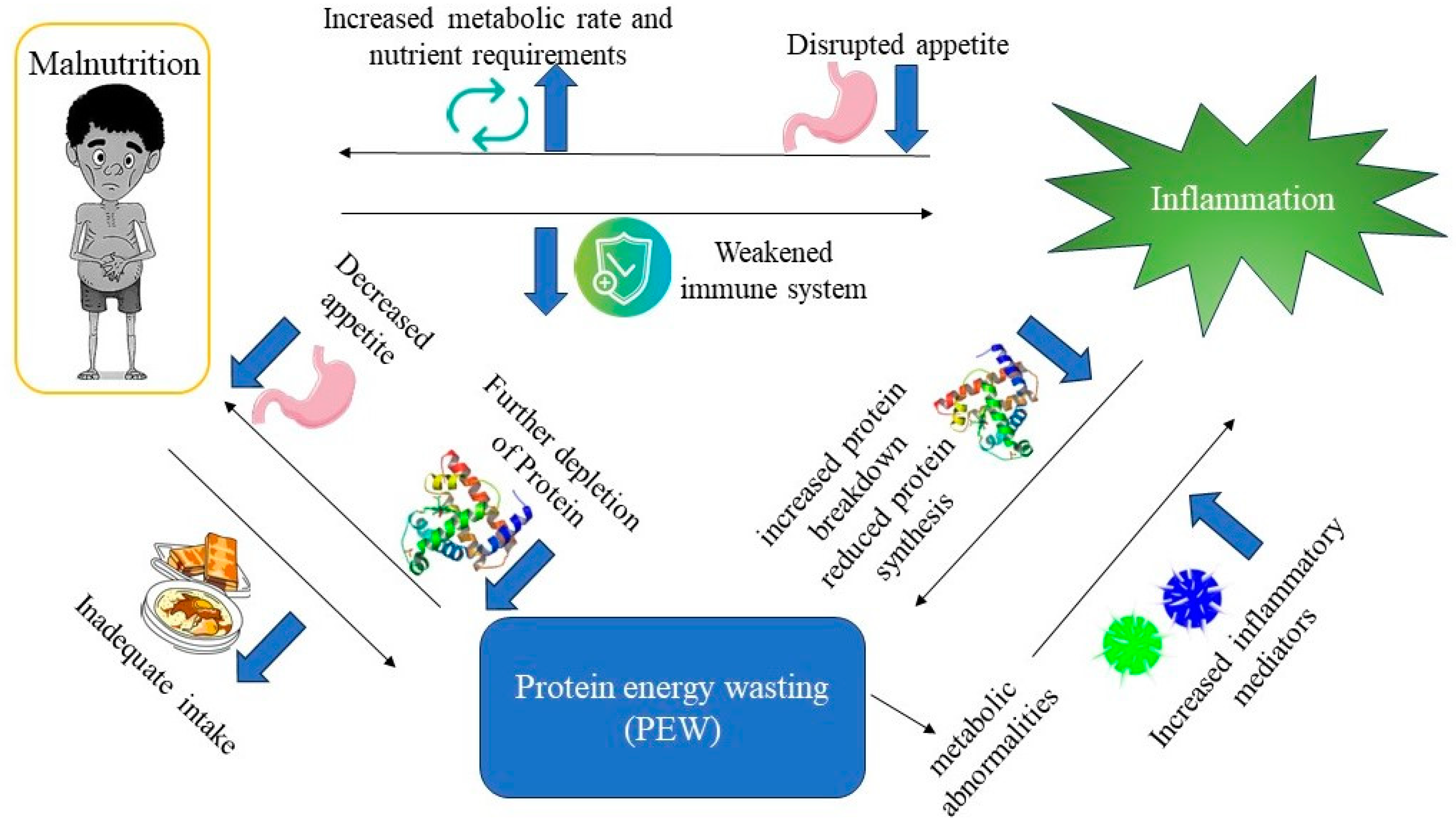

3.2.2. Protein Energy Wasting (PEW)

PEW is a state of metabolic and nutritional disorder that is intricately linked to malnutrition and inflammation [

84] (

Figure 2). PEW is commonly prevalent in patients with advanced CKD, particularly those undergoing dialysis. Importantly, patients with PEW are prone to fatigue, as it may lead to muscle mass loss, as well as a decline in protein and energy stores [

84,

85].

Body mass index (BMI) may be an indicator of PEW status. Maruyama

et al. [

15] found that among 194 hemodialysis patients with a mean BMI of 23±4 kg/m

2, higher BMI was associated with reduced fatigue. Nevertheless, BMI is not an ideal indicator of muscle mass, since it cannot distinguish lean mass from fat mass, or characterize body fat distribution [

86]. Thus, several studies reported a conflicting result that that severity of fatigue and impairment of physical function were positively related with higher BMI among HD and PD patients with a mean BMI of 27 ± 7 kg/m

2, as well as kidney transplant recipients with a mean BMI of 27 ± 5 kg/m

2 [

57,

58,

87]. Moreover, it is notable that the relation between BMI and outcomes may be influenced by age, since BMI cannot fully reflect the increase in fat mass and decrease in muscle mass that occur with age. Hoogeveen

et al. [

88] found that obesity in younger patients with CKD stage 4-5 (<65 years) and being underweight in older patients (≥65 years) were risk factors for adverse outcomes, compared with those with a normal BMI (20–24 kg/m

2).

It is worth noting that malnutrition is both a contributing factor to PEW and a consequence of PEW. Inadequate intake of protein and energy can lead to PEW, while PEW can lead to further depletion of protein stores, decreased appetite and food intake, exacerbating malnutrition [

84] (

Figure 2). A study found that reduced lean tissue index, as an indicator of muscle mass loss and a reflection of malnutrition, was a risk factor for fatigue in kidney transplant recipients [

24]. Furthermore, hypoalbuminemia may be the result of inadequate protein intake, which may contribute to malnutrition and skeletal muscle loss resulting in fatigue. There are a number of studies in patients with CKD stage 4-5D showing an inverse relation between albumin and fatigue [

12,

41,

42,

45,

46]. Debnath

et al. [

47] showed an inverse relation between fatigue severity and normalized protein catabolic rate (nPCR) among HD patients, but not with serum albumin.

Figure 2.

Interplay of PEW, malnutrition, and inflammation.

Figure 2.

Interplay of PEW, malnutrition, and inflammation.

3.2.3. Inflammation

Inflammatory biomarkers, such as increased levels of CRP and IL-6, as well as decreased levels of albumin, are associated with more severe fatigue in patients with advanced CKD. Previous studies including patients with CKD stage 4-5D and kidney transplant recipients demonstrated that fatigue was positively related with higher CRP level [

24,

57,

58,

89]. IL-6 has been also positively related to fatigue in studies conducted in HD and PD patients [

58,

90]. As a mediator of inflammatory processes, trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) has been found to positively associate with fatigue among 795 patients with CKD stage 4-5 [

53]. Inflammatory cytokines may result in fatigue directly through the central nervous system, and adrenal glands or indirectly through sleep and psychological disorders [

91]. Gregg

et al. [

89] found that fatigue in 103 patients with CKD stage 4-5 was correlated with higher levels of high-sensitivity CRP but not with IL-6, albumin and prealbumin. In contrast, Wang

et al. [

90] reported that fatigue in HD patients was associated with higher levels of IL-6 and lower levels of albumin, but not with CRP. This inconsistency may be due to differences in the study participants, with the former encompassing nondialysis patients and the latter involving HD patients.

3.2.4. Bone Metabolism

Most studies found that calcium, phosphorus and parathyroid hormone (PTH) were not related to fatigue in patients with CKD stage 4-5D [

28,

45,

58,

92]. However, a study showed that hyperparathyroidism was positively associated with fatigue in 511 HD patients, albeit the effect was relatively mild (95%CI 1.001-1.002) [

72]. Chronic Kidney Disease-Mineral and Bone Disorder (CKD-MBD) can result in different degrees of high-turnover or low-turnover bone diseases, leading to joint and muscle pain which may increase fatigue [

93].

Furthermore, Pang

et al. [

94] reported that higher levels of serum 25(OH) vitamin D was negatively associated with fatigue in HD patients ≥65 years but not in those <65 years. This finding may be explained by lower levels of Klotho with higher age. The α-Klotho protein is the receptor for Fibroblast Growth Factor-23 (FGF23), regulating phosphate homeostasis. With age, reduced expression of the Klotho gene leads to hyperphosphatemia, consequently leading to a deficiency in calcitriol (1,25-hydroxyvitamin D), along with increased inflammation. Ultimately, this progression may lead to vascular calcification, muscle loss, and fatigue [

95]. In elders, the interplay between Klotho and calcium-phosphate metabolism may magnify the role of 25(OH) vitamin D in the prevalence of fatigue, compared to younger counterparts.

3.2.5. Lactic Acidosis

A study revealed that higher levels of lactic acid was associated with more fatigue in HD patients [

96]. The decline in kidney function, as well as the presence of comorbidities such as cardiovascular diseases (CVD) and complications like renal anemia, may induce tissue hypoxia, thereby maintaining the production of lactate [

77,

97]. Lactic acid accumulation and the resulting decrease in cellular pH is believed to be involved in muscle fatigue [

98].

3.2.6. Comorbidities

Diabetes

Previous studies highlighted that the presence of diabetes was positively related to fatigue in both patients with CKD stage 4-5 and hemodialysis patients [

28,

45]. Furthermore, Biniaz

et al. [

60] found that HD patients with diabetic kidney disease had higher fatigue scores compared with patients with other causes of kidney failure. Diabetes related fatigue can be attributed to physiological factors, including hypo- or hyperglycemia; psychological factors, such as diabetes-related emotional distress; and unhealthy lifestyle, such as sedentary lifestyle and obesity [

99].

Cardiovascular Disease (CVD)

CVD affects the vast majority of patients with CKD stage 4-5D. Jhamb

et al. [

12] reported that the presence of CVD was independently associated with worse fatigue in patients with CKD, of whom 50% were patients with CKD stage 5D. This finding is consistent with that in older adults without CVD at baseline [

100]. Patients with CVD may suffer from hypoxemia, sleep disorders and inflammation, resulting in fatigue [

100].

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)

The prevalence of CKD in patients with COPD ranges from 7% to 53% [

101]. In kidney transplant recipients, the prevalence of COPD is higher than that in healthy controls: 25%

vs 10% [

102]. Furthermore, a study found that obstructive lung disease more than doubles the risk of severe fatigue among kidney transplant recipients [

102]. Peters

et al. [

103] found that the proportion of patients with severe fatigue doubled during a 4-year follow-up, even if the degree of obstructive lung disease remained stable. Therefore, other physical or psychological factors, play also a causal role in the prevalence of fatigue [

104].

Finally, the relation between the increasing number of comorbidities and higher levels of fatigue has been widely investigated among patients with CKD stage 4-5 and HD patients [

25,

28,

45,

48,

49,

57,

71,

96].

3.2.7. Uremic Symptoms

Some studies reported the adverse impact of complications of CKD on fatigue in dialysis patients. Unruh

et al. [

105] found that severe restless legs syndrome was not only related with diminished sleep disorders, but with decreased physical functioning and well-being among 669 HD patients and 225 PD patients. The Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS) reported that among 9964 HD patients, those with extreme pruritus had 5.2 times higher odds of experiencing fatigue compared to patients without pruritus [

106]. This can be attributed to the higher susceptibility of patients with pruritus to develop sleep disorders, which may lead to lower HRQOL [

107]. A study by Zuo

et al. [

72] found that cramping, headache, chest tightness, whole-body pain and decreased appetite were risk factors for fatigue in HD patients.

3.3. Mental Factors

3.3.1. Depression and Anxiety

Numerous studies conducted in HD patients, PD patients and kidney transplant recipients demonstrated that depression was strongly associated with more fatigue [

9,

12,

24,

44,

47,

52,

108,

109,

110,

111]. There are similarities in the manifestations of fatigue and depression. Depression often manifests itself as lethargy and feelings of weakness and tiredness [

9].

Some studies also reported a positive association between fatigue and anxiety among HD patients [

52,

108]. In addition, being anxious about change in body appearance after undergoing dialysis [

48] and damage [

62] were also positively correlated with fatigue.

Depression and anxiety are entangled. Overall, mental factors play a critical role in fatigue. Although Letchmi

et al. [

59] found no association between depression, anxiety and fatigue, it may be explained by small sample size (103 patients) and Asian cultural factor, as Asians may feel ashamed to admit mental diseases [

112].

3.3.2. Sleep Disorders

Sleep disorders, such as insomnia and obstructive sleep apnea, are one of the most common (49%-80 %) symptoms among patients with CKD stage 4-5, especially among dialysis patients [

113,

114]. Previous studies showed that sleep disorders had a strong association with fatigue both in patients with CKD stage 4-5D and kidney transplant recipients [

12,

24,

45,

46,

48,

52,

71,

115], as it may lead to daytime sleepiness and poor concentration. A study by Jhamb

et al. [

12] found that poor self-reported sleep quality was related to excessive daytime sleepiness and fatigue. Previous studies also found that sleep deficiency increases levels of inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6, TNF and IL-1, amplifies inflammatory pathways and reduces the functional capacity of leukocytes. This disruption of immune homeostasis may lead to increased fatigue [

6,

116].

3.4. Treatment-Related Factors

3.4.1. Dialysis

An important factor that cannot be ignored is the negative impact which dialysis treatment itself may have on fatigue. Post-dialysis fatigue (PDF) is a common and incapacitating symptom in hemodialysis patients [

42,

43,

96,

117]. Moreover, Debnath

et al. [

47] and Maruyama

et al. [

15] found that patients were more fatigue on dialysis days than on non-dialysis days, that cannot be explained by other factors. In addition, complications such as low blood pressure and excessively rapid ultrafiltration rate during dialysis that were associated with unstable hemodynamic changes may contribute to fatigue on dialysis days [

96,

117].

Low blood pressure related to dialysis, particularly post-dialysis low mean arterial pressure (MAP), post-dialysis low diastolic blood pressure, or intradialytic hypotension (IDH) are risk factors for post-dialysis fatigue [

117]. Low MAP after hemodialysis leads to hypoperfusion of vital organs and prolongs recovery time of the brain and heart, which attributes to fatigue in HD patients [

111]. A study found that increased extracellular water (ECW) after hemodialysis was associated with higher levels of fatigue, possibly due to IDH that hinders fluid removal, which then leads to longer recovery time after hemodialysis [

111].

Regarding dialysis adequacy, previous studies found that higher dialysis adequacy (as measured by Kt/V or urea reduction ratio (URR)) was positively related with daily activity and negatively related with fatigue [

42,

44]. However, other studies failed to find such a relation [

50,

92]. This may be due to the requirement for dialysis patients to meet target KT/V according to treatment guidelines. Consequently, there is a tendency for data homogeneity, making it challenging to identify the relation between dialysis adequacy and fatigue. Furthermore, diuretic usage and residual kidney function (RKF) may also be confounding factors. Patients with higher rest-diuresis and higher RKF requite less frequent dialysis treatment and have a lower weekly Kt/V.

Regarding types of kidney replacement therapy (KRT), limited studies found that patients undergoing PD experienced the highest levels of fatigue and the lowest levels of activity compared to patients receiving HD and kidney transplant recipients [

41], while the majority of the studies did not show a relation between types of KRT and fatigue [

15,

58,

118,

119]. Patients with better RKF may prefer PD over HD, meanwhile, PD is considered to preserve RKF better than HD [

120]. Better RKF is associated with a better HRQOL including lower levels of fatigue in dialysis patients [

121]. Many studies regrettably disregarded the influence of RKF, potentially compromising the assessment of disparities between dialysis modalities.

The hemodialysis (HEMO) study showed that among patients with an average dialysis vintage of 4 years, those with a longer dialysis vintage experienced lower level of fatigue (Adjusted odds ratio 0.97,

P = 0.02). It should be noted that the study participants may represent a self-selected cohort of patients who are comparatively healthier than those who did not survive long enough to be enrolled in the study [

45]. However, another study revealed that severity of fatigue did not reduce linearly with an increase in vintage. Severity of fatigue appeared to decrease within 6-24 months of dialysis, then increase with dialysis vintage [

62]. Fatigue may not be merely associated with dialysis vintage [

62]. Although fatigue may alleviate with the decrease of uremic toxins after starting dialysis, its positive effects may be outweighed by the negative effects of declining RKF with the increase of dialysis vintage.

3.4.2. Medication

Polypharmacy is common in patients with CKD stage 4-5D and associated with adverse outcomes [

122]. Up to now, only a small number of studies have explored the relation between medication and fatigue in patients with CKD stage 4-5D. Among 148 patients with CKD stage 4-5, Gregg

et al. [

28] reported that the use of β-blockers was associated with increased fatigue measured by the SF-12. It may be attributed to CVD or the side effects of β-blockers [

123]. Additionally, β-blockers is positively associated with depression and sleep disorders [

124], which may consequently contribute to fatigue.

Gregg

et al. [

28] found that using antidepressant medication compared to those without, was associated with more fatigue in patients with CKD stage 4-5 and major depressive disorder (MDD). Likewise, in HD patients and PD patients, Jhamb

et al. [

58] found the similar relation. Next to collinearity between depression and fatigue, the modulation of norepinephrine, serotonin, and/or dopamine-receptor activity by antidepressants may lead to sleep disorders and muscle weakness [

125].

The association between medication use for sleep disorders and fatigue was reported by Jhamb

et al. [

45]. This could be attributed to sleep disorders as a risk factor for fatigue or side effects of the medication.

4. Potential Treatments

Since the etiology of fatigue in patients with CKD stage 4-5D is unclear, and the risk factors for fatigue are inconsistent and contradictory, currently there is no universally accepted treatment strategies. Multidisciplinary synergistic therapy may be ideal as fatigue is multifactorial and multidimensional. Taken together, treatment of fatigue in patients with CKD stage 4-5D includes pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions.

4.1. Pharmacological Interventions

4.1.1. ESA

A study showed that in both HD and PD patients, the treatment of anemia with ESA can decrease the levels of fatigue [

15]. However, a prospective trial for patients with CKD stage 4 failed to find the differences in the degree of fatigue between ESA group and placebo group by using the SF-36 (mean change in the score for energy, 3±10 points

vs 2±10 points;

P = 0.20; mean change in the score for physical functioning, 1±9

vs 1±9;

P = 0.51) [

126].

Although the 2012 KDIGO guideline suggests the general timing for initiating ESA therapy is a Hb 9-10 g/dL in dialysis patients and < 10 g/dL in CKD stage 3-5, it also recommends individualized treatment and Hb targets to achieve better HRQOL, especially to alleviate fatigue symptom [

78,

79]. Nevertheless, use of ESA may result in higher risk of CVD, progression of CKD and death. Minutolo

et al. [

127] found that risk of progression of CKD and death was higher when the dose of ESA was >105 IU/kg/week in 480 patients with CKD stage 4-5. Another study showed that HD patients using high-dose ESA suffered higher risk of death and CVD (≥ 20,000 U/week

vs < 20,000 U/week) [

128]. Importantly, age, comorbidities including malignancy, CVD should also be taken into account when deciding to start or not and choosing the appropriate dose of ESA and Hb target.

Among kidney transplant recipients, a previous review reported that ESA treatment of anemia should be initiated as soon as possible, meanwhile the Hb target was higher than that in CKD and may be up to 12.5-13.0 g/dL [

82], albeit there is few research on the optimal dose of ESA for this group.

Furthermore, it is noteworthy that oral hypoxia-inducible factors (HIF) stabilizers are now available to manage anemia in people with CKD stage 4-5D, yet the effects of HIF on fatigue is uncertain compared with ESA [

129].

4.1.2. L-Carnitine (LC)

LC plays a vital role in the procedure of oxidation of fatty acids, and it is also vital in energy metabolism. However, due to acute removal of carnitine during dialysis and malnutrition, carnitine is deficient, leading to impaired muscle energetics and fatigue in HD patients [

130]. LC supplementation has been recommended in dialysis patients for reducing fatigue and muscle weakness, and improving poor physical exercise, as it may mitigate insulin resistance, inflammation, and protein wasting [

131,

132].

4.1.3. Sodium Bicarbonate

Metabolic acidosis (MA) is a common complication in patients with CKD stage 4-5D [

133]. Sodium bicarbonate supplementation is a reasonable approach to tackle this issue. Correction of MA may be able to improve or prevent the supervening muscle wasting and weakness [

134]. A study conducted by Abramowitz

et al. [

135] in 20 patients with CKD (mean eGFR is 33±9 ml/min per 1.73 m

2), found that sodium bicarbonate supplementation could improve lower extremity muscle strength.

4.1.4. Antidepressant Medication

While antidepressant medication is considered a risk factor for fatigue due to side effects [

125], it is important to acknowledge that depression itself is also a risk factor for fatigue. Therefore, seeking antidepressant medication with fewer side effects may alleviate both depression and fatigue. Hedayati

et al. [

136] failed to find improvement in fatigue comparing sertraline, a Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor (SSRI), versus placebo in 103 patients with CKD stage 4-5 and MDD. Another study demonstrated that bupropion, a dual noradrenaline and dopamine reuptake inhibitor, may be superior to SSRI in alleviating sleepiness and fatigue in remitted MDD patients [

137]. Nonetheless, the impact of bupropion on fatigue in patients with CKD stage 4-5D and MDD remains uncertain.

4.2. Nonpharmacological Interventions

4.2.1. Physical Activity

Physical activity with appropriate intensity may improve fatigue. Some studies revealed that exercise was positively associated with reduced fatigue severity [

57,

58,

71,

72]. During a nine-month hybrid intradialytic exercise program, aerobic and resistance exercise training was found to be a safe and effective approach to improve symptoms of fatigue in 20 HD patients [

138]. Another exercise study (N= 20) including 2 daily 10-minute home walking sessions on the non-dialysis day demonstrated that active lifestyle could assist HD patients improving fatigue and maintaining better physical function over a 2-year period [

139].

Even though exercise programs for patients with CKD stage 4-5D have been introduced for many years, their use is still not widespread. For one thing, the relation between exercise and fatigue is likely to be bidirectional. Fatigue has been perceived as the exercise barrier and it leads to limited physical activity and exercise [

140]. For another, the exercise programs are strenuous for patients with severe comorbidities and should be personalized. Therefore, many kidney units are unwilling to offer exercise therapy in order to avoid occurrence of adverse events[

141]. Nevertheless, a recent clinical trial conducted in 693 HD patients, including those with frailty, found that exercise could improve physical function while avoiding adverse events [

142].

4.2.2. Psychological Interventions

In addition to antidepressant medication, psychological interventions seem promising in treating depression and fatigue. According to some meta-analyses, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) may improve quality of life and alleviate fatigue while reducing depressive symptoms for dialysis patients with moderate-certainty evidence [

143,

144]. Moreover, with the progress of technology, a study found that internet-based self-help CBT (ICBT) is also a plausible approach that was effective in HD patients [

145].

Problem solving therapy (PST) may be another effective psychotherapy to alleviate depressive symptoms for depression in HD patients≥ 60 years [

146]. However, Nadort

et al. [

147] reported that

Internet-based version of PST (IPST) did not show any improvement in decreasing depressive symptoms compared with usual care in HD patients.

4.2.3. Dialysis

Among patients with advanced CKD, although dialysis itself might be a risk factor for fatigue, the EQUAL study demonstrated that fatigue improved after initiation of dialysis among older patients (mean (SD) age was 76 (6) years) [

2]. ECW may be related to fatigue in dialysis patients, hence the improvement in fatigue following dialysis may be attributed to the alleviation of fluid overload [

111].

Among HD patients, cold dialysis was found to relieve the symptom of fatigue [

148], as cooling the dialysate below 36.5°C possibly improves hemodynamic stability and systolic blood pressure during the therapy. Azar

et al. [

149] found that patients felt more energetic after dialysis with cool dialysate. It should be noted that there are some potential side effects related to long-term use of cooled dialysate, including shivering, cramps, and decreased URR [

150].

4.2.4. Aromatherapy

Aromatherapy utilizes concentrated essential oils derived from herbs, flowers, and other botanical sources for therapy [

151]. It is applied through inhalation or massage methods to alleviate symptoms, with sessions ranging from 2 to 60 minutes [

152]. Several meta-analyses have concluded that both compound and single essential oils, such as lavender and citrus aurantium essential oils, effectively reduce fatigue in hemodialysis patients [

152,

153,

154]. Aromatic inhalation may induce the release of endorphins, enkephalins, and noradrenaline through the stimulation of the olfactory system and lymphatic system, promoting relaxation. Aromatic massage, on the other hand, may enhance blood circulation, relax muscles, and relieve fatigue by acting on the skin and lymphatic system [

155]. However, the mechanism of aromatherapy remains unclear, and there is ongoing debate regarding the optimal type, concentration, administration method, and duration of essential oils for fatigue improvement.

5. Challenges and Future Areas of Study

Fatigue is highly prevalent in patients with advanced CKD. Despite the high burden of fatigue and its negative impact on outcomes, this symptom is frequently under-reported, under-recognized, under-estimated, and consequently under-treated [

156]. There are many reasons contributing to the current diagnostic and therapeutic dilemma.

First, considerable uncertainty still exists about the relation between risk factors and fatigue. Since fatigue is multifactorial, and it often interacts with other complications and comorbidities, identifying plausible causal associations is challenging. A further study with more focus on etiology and pathophysiology is therefore suggested.

Second, compared to HD patients, there are relatively few studies on fatigue among patients with CKD stage 4-5 and PD patients. Moreover, there is a paucity of research comparing fatigue before and after initiation of dialysis. Therefore, future studies should be undertaken in these populations in order to provide evidence to support symptom management of fatigue.

Last, there are limitations in fatigue management studies, including the absence of standard measurement of fatigue, small sample size, selection bias and/or limited follow-up. These limitations are not conducive to the evaluation and comparison of various approaches. Consequently, future studies identifying standard measurement of fatigue and developing more targeted interventions are warranted.

6. Conclusions

Fatigue is a commonly reported and important symptom among patients with advanced CKD. To date, this issue is still in the early phases of research. While there are numerous scales available for measuring fatigue, such as SF-36, SF-12, KDQOL-SF, FACIT-F, PFS and DSI, the lack of a clear consensus on the definition of fatigue results in a lack of the best tool to measure this multifaceted symptom. Risk factors for fatigue in patients with advanced CKD are multiple and complex. Older age, female, white ethnicity, less education, unemployment and less social support, were socio-demographic risk factors for fatigue. Anemia, PEW, inflammation, lactic acidosis, comorbidities (e.g., diabetes, CVD, and COPD), and uremic symptoms (e.g., RLS and pruritus), are physiological factors that contribute to fatigue. Depression, anxiety and sleep disorders are mental risk factors related to fatigue. Dialysis treatment, dialysis-related low blood pressure and low dialysis adequacy, as well as medication (e.g., β-blockers, antidepressant medication and medication for sleep disorders) are treatment-related risk factors for fatigue. Yet some previous findings are inconsistent and conflicting, and evidence regarding mechanism to inform the development of fatigue for CKD stage 4-5D population is still lacking.

Currently, pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions have been used to decrease levels of fatigue. Individualized anemia treatment and physical activity are the most promising approaches. Other pharmacological interventions (e.g., LC, sodium bicarbonate, and antidepressants) and nonpharmacological interventions (e.g., psychological interventions and cool dialysate), are still being studied. Given the severe burden of fatigue and uncertainty about the treatment, future studies are needed to identify the risk factors associated with fatigue, which will be crucial for identifying high-risk patients earlier and developing more effective interventions.

References

- Voskamp P, van Diepen M, Evans M, Caskey FJ, Torino C, Postorino M, et al.. The impact of symptoms on health-related quality of life in elderly pre-dialysis patients: effect and importance in the EQUAL study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2019; 34: 1707-15. [CrossRef]

- de Rooij E, Meuleman Y, de Fijter JW, Jager KJ, Chesnaye NC, Evans M, et al.. Symptom burden before and after dialysis initiation in older patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2022; 17: 1719-29. [CrossRef]

- Lockwood MB, Chung S, Puzantian H, Bronas UG, Ryan CJ, Park C, et al.. Symptom cluster science in chronic kidney disease: a literature review. West J Nurs Res. 2019; 41: 1056-91. [CrossRef]

- You AS, Kalantar SS, Norris KC, Peralta RA, Narasaki Y, Fischman R, et al.. Dialysis symptom index burden and symptom clusters in a prospective cohort of dialysis patients. J Nephrol. 2022; 35: 1427-36. [CrossRef]

- de Rooij E, Meuleman Y, de Fijter JW, Le Cessie S, Jager KJ, Chesnaye NC, et al.. Quality of life before and after the start of dialysis in older patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2022; 17: 1159-67. [CrossRef]

- Jhamb M, Weisbord SD, Steel JL, Unruh M. Fatigue in patients receiving maintenance dialysis: a review of definitions, measures, and contributing factors. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008; 52: 353-65. [CrossRef]

- Chesnaye NC, Meuleman Y, de Rooij E, Hoogeveen EK, Dekker FW, Evans M, et al.. Health-related quality-of-life trajectories over time in older men and women with advanced chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2022; 17: 205-14. [CrossRef]

- Artom M, Moss-Morris R, Caskey F, Chilcot J. Fatigue in advanced kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2014; 86: 497-505. [CrossRef]

- Picariello F, Moss-Morris R, Macdougall IC, Chilcot AJ. The role of psychological factors in fatigue among end-stage kidney disease patients: a critical review. Clin Kidney J. 2017; 10: 79-88. [CrossRef]

- Penner IK, Paul F. Fatigue as a symptom or comorbidity of neurological diseases. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017; 13: 662-75. [CrossRef]

- Dantzer R, Heijnen CJ, Kavelaars A, Laye S, Capuron L. The neuroimmune basis of fatigue. Trends Neurosci. 2014; 37: 39-46. [CrossRef]

- Jhamb M, Liang K, Yabes J, Steel JL, Dew MA, Shah N, et al.. Prevalence and correlates of fatigue in chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease: are sleep disorders a key to understanding fatigue? Am J Nephrol. 2013; 38: 489-95.

- Horigan AE. Fatigue in hemodialysis patients: a review of current knowledge. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012; 44: 715-24. [CrossRef]

- Ju A, Unruh M, Davison SN, Dapueto J, Dew MA, Fluck R, et al.. Identifying dimensions of fatigue in haemodialysis important to patients, caregivers and health professionals: an international survey. Nephrology (Carlton). 2020; 25: 239-47. [CrossRef]

- Maruyama Y, Nakayama M, Ueda A, Miyazaki M, Yokoo T. Comparisons of fatigue between dialysis modalities: a cross-sectional study. Plos One. 2021; 16: e246890. [CrossRef]

- Evangelidis N, Tong A, Manns B, Hemmelgarn B, Wheeler DC, Tugwell P, et al.. Developing a set of core outcomes for trials in hemodialysis: an international Delphi survey. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017; 70: 464-75. [CrossRef]

- Wright J, O'Connor KM. Fatigue. Med Clin North Am. 2014; 98: 597-608.

- Goertz Y, Braamse A, Spruit MA, Janssen D, Ebadi Z, Van Herck M, et al.. Fatigue in patients with chronic disease: results from the population-based Lifelines Cohort Study. Sci Rep. 2021; 11: 20977. [CrossRef]

- Mujais SK, Story K, Brouillette J, Takano T, Soroka S, Franek C, et al.. Health-related quality of life in CKD Patients: correlates and evolution over time. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009; 4: 1293-301.

- Pagels AA, Soderkvist BK, Medin C, Hylander B, Heiwe S. Health-related quality of life in different stages of chronic kidney disease and at initiation of dialysis treatment. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012; 10: 71. [CrossRef]

- Senanayake S, Gunawardena N, Palihawadana P, Bandara P, Haniffa R, Karunarathna R, et al.. Symptom burden in chronic kidney disease; a population based cross sectional study. Bmc Nephrol. 2017; 18: 228. [CrossRef]

- Afshar M, Rebollo-Mesa I, Murphy E, Murtagh FE, Mamode N. Symptom burden and associated factors in renal transplant patients in the U.K. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012; 44: 229-38. [CrossRef]

- Bossola M, Pepe G, Vulpio C. Fatigue in kidney transplant recipients. Clin Transplant. 2016; 30: 1387-93. [CrossRef]

- Chan W, Bosch JA, Jones D, Kaur O, Inston N, Moore S, et al.. Predictors and consequences of fatigue in prevalent kidney transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2013; 96: 987-94. [CrossRef]

- Wilund KR, Thompson S, Viana JL, Wang AY. Physical activity and health in chronic kidney disease. Contrib Nephrol. 2021; 199: 43-55.

- Jayanti A, Foden P, Morris J, Brenchley P, Mitra S. Time to recovery from haemodialysis: location, intensity and beyond. Nephrology (Carlton). 2016; 21: 1017-26.

- Ng M, Chan D, Cheng Q, Miaskowski C, So W. Association between financial hardship and symptom burden in patients receiving maintenance dialysis: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021; 18: 9541. [CrossRef]

- Gregg LP, Jain N, Carmody T, Minhajuddin AT, Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, et al.. Fatigue in nondialysis chronic kidney disease: correlates and association with kidney outcomes. Am J Nephrol. 2019; 50: 37-47. [CrossRef]

- Bossola M, Di Stasio E, Antocicco M, Panico L, Pepe G, Tazza L. Fatigue is associated with increased risk of mortality in patients on chronic hemodialysis. Nephron. 2015; 130: 113-18. [CrossRef]

- de Goeij MC, Ocak G, Rotmans JI, Eijgenraam JW, Dekker FW, Halbesma N. Course of symptoms and health-related quality of life during specialized pre-dialysis care. Plos One. 2014; 9: e93069. [CrossRef]

- Guedes M, Wallim L, Guetter CR, Jiao Y, Rigodon V, Mysayphonh C, et al.. Fatigue in incident peritoneal dialysis and mortality: a real-world side-by-side study in Brazil and the United States. Plos One. 2022; 17: e270214. [CrossRef]

- Metzger M, Abdel-Rahman EM, Boykin H, Song MK. A narrative review of management strategies for common symptoms in advanced CKD. Kidney Int Rep. 2021; 6: 894-904. [CrossRef]

- Ju A, Unruh ML, Davison SN, Dapueto J, Dew MA, Fluck R, et al.. Patient-reported outcome measures for fatigue in patients on hemodialysis: a systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis. 2018; 71: 327-43. [CrossRef]

- Ware JJ, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996; 34: 220-33.

- Hays RD, Kallich JD, Mapes DL, Coons SJ, Carter WB. Development of the kidney disease quality of life (KDQOL) instrument. Qual Life Res. 1994; 3: 329-38.

- Wang SY, Zang XY, Liu JD, Gao M, Cheng M, Zhao Y. Psychometric properties of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (FACIT-Fatigue) in Chinese patients receiving maintenance dialysis. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015; 49: 135-43. [CrossRef]

- Machado MO, Kang NC, Tai F, Sambhi R, Berk M, Carvalho AF, et al.. Measuring fatigue: a meta-review. Int J Dermatol. 2021; 60: 1053-69.

- van der Willik EM, Meuleman Y, Prantl K, van Rijn G, Bos W, van Ittersum FJ, et al.. Patient-reported outcome measures: selection of a valid questionnaire for routine symptom assessment in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease - a four-phase mixed methods study. Bmc Nephrol. 2019; 20: 344. [CrossRef]

- Weisbord SD, Fried LF, Arnold RM, Rotondi AJ, Fine MJ, Levenson DJ, et al.. Development of a symptom assessment instrument for chronic hemodialysis patients: the Dialysis Symptom Index. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004; 27: 226-40. [CrossRef]

- Ju A, Teixeira-Pinto A, Tong A, Smith AC, Unruh M, Davison SN, et al.. Validation of a core patient-reported outcome measure for fatigue in patients receiving hemodialysis: the SONG-HD fatigue instrument. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020; 15: 1614-21.

- Bonner A, Wellard S, Caltabiano M. The impact of fatigue on daily activity in people with chronic kidney disease. J Clin Nurs. 2010; 19: 3006-15. [CrossRef]

- Bossola M, Di Stasio E, Sirolli V, Ippoliti F, Cenerelli S, Monteburini T, et al.. Prevalence and severity of postdialysis fatigue are higher in patients on chronic hemodialysis with functional disability. Ther Apher Dial. 2018; 22: 635-40. [CrossRef]

- Bossola M, Picca A, Monteburini T, Parodi E, Santarelli S, Cenerelli S, et al.. Post-dialysis fatigue and survival in patients on chronic hemodialysis. J Nephrol. 2021; 34: 2163-65. [CrossRef]

- Liu HE. Fatigue and associated factors in hemodialysis patients in Taiwan. Res Nurs Health. 2006; 29: 40-50. [CrossRef]

- Jhamb M, Pike F, Ramer S, Argyropoulos C, Steel J, Dew MA, et al.. Impact of fatigue on outcomes in the hemodialysis (HEMO) study. Am J Nephrol. 2011; 33: 515-23. [CrossRef]

- Yang PC, Lu YY. Predictors of fatigue among female patients on hemodialysis. Nephrol Nurs J. 2017; 44: 533-39.

- Debnath S, Rueda R, Bansal S, Kasinath BS, Sharma K, Lorenzo C. Fatigue characteristics on dialysis and non-dialysis days in patients with chronic kidney failure on maintenance hemodialysis. Bmc Nephrol. 2021; 22: 112. [CrossRef]

- Tsirigotis S, Polikandrioti M, Alikari V, Dousis E, Koutelekos I, Toulia G, et al.. Factors associated with fatigue in patients undergoing hemodialysis. Cureus. 2022; 14: e22994. [CrossRef]

- Akin S, Mendi B, Ozturk B, Cinper C, Durna Z. Assessment of relationship between self-care and fatigue and loneliness in haemodialysis patients. J Clin Nurs. 2014; 23: 856-64. [CrossRef]

- Ossareh S, Roozbeh J, Krishnan M, Liakopoulos V, Bargman JM, Oreopoulos DG. Fatigue in chronic peritoneal dialysis patients. Int Urol Nephrol. 2003; 35: 535-41. [CrossRef]

- Cantekin I, Tan M. Determination of sleep quality and fatigue level of patients receiving continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis in Turkey. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2011; 45: 452-60. [CrossRef]

- Al NZ, Gormley K, Noble H, Santin O, Al MM. Fatigue, anxiety, depression and sleep quality in patients undergoing haemodialysis. Bmc Nephrol. 2021; 22: 157. [CrossRef]

- Massy ZA, Chesnaye NC, Larabi IA, Dekker FW, Evans M, Caskey FJ, et al.. The relationship between uremic toxins and symptoms in older men and women with advanced chronic kidney disease. Clin Kidney J. 2022; 15: 798-807. [CrossRef]

- van de Luijtgaarden M, Caskey FJ, Wanner C, Chesnaye NC, Postorino M, Janmaat CJ, et al.. Uraemic symptom burden and clinical condition in women and men of >/=65 years of age with advanced chronic kidney disease: results from the EQUAL study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2019; 34: 1189-96.

- Courtenay WH. Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men's well-being: a theory of gender and health. Soc Sci Med. 2000; 50: 1385-401.

- Gemmell LA, Terhorst L, Jhamb M, Unruh M, Myaskovsky L, Kester L, et al.. Gender and racial differences in stress, coping, and health-related quality of life in chronic kidney disease. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016; 52: 806-12. [CrossRef]

- Chilcot J, Moss-Morris R, Artom M, Harden L, Picariello F, Hughes H, et al.. Psychosocial and clinical correlates of fatigue in haemodialysis patients: the importance of patients' illness cognitions and behaviours. Int J Behav Med. 2016; 23: 271-81. [CrossRef]

- Jhamb M, Argyropoulos C, Steel JL, Plantinga L, Wu AW, Fink NE, et al.. Correlates and outcomes of fatigue among incident dialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009; 4: 1779-86. [CrossRef]

- Letchmi S, Das S, Halim H, Zakariah FA, Hassan H, Mat S, et al.. Fatigue experienced by patients receiving maintenance dialysis in hemodialysis units. Nurs Health Sci. 2011; 13: 60-64. [CrossRef]

- Biniaz V, Tayybi A, Nemati E, Sadeghi SM, Ebadi A. Different aspects of fatigue experienced by patients receiving maintenance dialysis in hemodialysis units. Nephrourol Mon. 2013; 5: 897-900. [CrossRef]

- Kutner NG, Brogan D, Fielding B, Hall WD. Black/white differences in symptoms and health satisfaction reported by older hemodialysis patients. Ethn Dis. 2000; 10: 328-33.

- Picariello F, Norton S, Moss-Morris R, Macdougall IC, Chilcot J. A prospective study of fatigue trajectories among in-centre haemodialysis patients. Br J Health Psychol. 2020; 25: 61-88. [CrossRef]

- Weisbord SD, Bossola M, Fried LF, Giungi S, Tazza L, Palevsky PM, et al.. Cultural comparison of symptoms in patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Hemodial Int. 2008; 12: 434-40. [CrossRef]

- Kimmel PL, Emont SL, Newmann JM, Danko H, Moss AH. ESRD patient quality of life: symptoms, spiritual beliefs, psychosocial factors, and ethnicity. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003; 42: 713-21. [CrossRef]

- Zyga S, Alikari V, Sachlas A, Fradelos EC, Stathoulis J, Panoutsopoulos G, et al.. Assessment of fatigue in end stage renal disease patients undergoing hemodialysis: prevalence and associated factors. Med Arch. 2015; 69: 376-80. [CrossRef]

- Billany RE, Thopte A, Adenwalla SF, March DS, Burton JO, Graham-Brown M. Associations of health literacy with self-management behaviours and health outcomes in chronic kidney disease: a systematic review. J Nephrol. 2023; 36: 1267-81. [CrossRef]

- Elisabeth SU, Klopstad WA, Gunnar GL, Hjorthaug UK. Health literacy in kidney disease: associations with quality of life and adherence. J Ren Care. 2020; 46: 85-94.

- Gerogianni G, Lianos E, Kouzoupis A, Polikandrioti M, Grapsa E. The role of socio-demographic factors in depression and anxiety of patients on hemodialysis: an observational cross-sectional study. Int Urol Nephrol. 2018; 50: 143-54. [CrossRef]

- Dinh H, Nguyen NT, Bonner A. Healthcare systems and professionals are key to improving health literacy in chronic kidney disease. J Ren Care. 2022; 48: 4-13. [CrossRef]

- Green JA, Mor MK, Shields AM, Sevick MA, Arnold RM, Palevsky PM, et al.. Associations of health literacy with dialysis adherence and health resource utilization in patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013; 62: 73-80. [CrossRef]

- Wang SY, Zang XY, Fu SH, Bai J, Liu JD, Tian L, et al.. Factors related to fatigue in Chinese patients with end-stage renal disease receiving maintenance hemodialysis: a multi-center cross-sectional study. Ren Fail. 2016; 38: 442-50. [CrossRef]

- Zuo M, Tang J, Xiang M, Long Q, Dai J, Hu X. Relationship between fatigue symptoms and subjective and objective indicators in hemodialysis patients. Int Urol Nephrol. 2018; 50: 1329-39. [CrossRef]

- Park M, Chesla C. Revisiting Confucianism as a conceptual framework for Asian family study. J Fam Nurs. 2007; 13: 293-311.

- Alexopoulou M, Giannakopoulou N, Komna E, Alikari V, Toulia G, Polikandrioti M. The effect of perceived social support on hemodialysis patients' quality of life. Mater Sociomed. 2016; 28: 338-42. [CrossRef]

- Eriksson D, Goldsmith D, Teitsson S, Jackson J, van Nooten F. Cross-sectional survey in CKD patients across Europe describing the association between quality of life and anaemia. Bmc Nephrol. 2016; 17: 97. [CrossRef]

- Motonishi S, Tanaka K, Ozawa T. Iron deficiency associates with deterioration in several symptoms independently from hemoglobin level among chronic hemodialysis patients. Plos One. 2018; 13: e201662. [CrossRef]

- Gregg LP, Bossola M, Ostrosky-Frid M, Hedayati SS. Fatigue in CKD: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and treatment. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021; 16: 1445-55.

- Improving Global Outcomes KDIGO Anemia Work Group KD. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for anemia in CKD. Kidney Int Suppl. 2012; 2: 279-335.

- Guedes M, Guetter CR, Erbano L, Palone AG, Zee J, Robinson BM, et al.. Physical health-related quality of life at higher achieved hemoglobin levels among chronic kidney disease patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bmc Nephrol. 2020; 21: 259. [CrossRef]

- Wyatt CM, Drueke TB. Higher hemoglobin levels and quality of life in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease: no longer a moving target? Kidney Int. 2016; 89: 971-73.

- Singh AK, Szczech L, Tang KL, Barnhart H, Sapp S, Wolfson M, et al.. Correction of anemia with epoetin alfa in chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2006; 355: 2085-98. [CrossRef]

- Gafter-Gvili A, Gafter U. Posttransplantation anemia in kidney transplant recipients. Acta Haematol. 2019; 142: 37-43. [CrossRef]

- Heinze G, Kainz A, Horl WH, Oberbauer R. Mortality in renal transplant recipients given erythropoietins to increase haemoglobin concentration: cohort study. BMJ. 2009; 339: b4018. [CrossRef]

- Fouque D, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kopple J, Cano N, Chauveau P, Cuppari L, et al.. A proposed nomenclature and diagnostic criteria for protein-energy wasting in acute and chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2008; 73: 391-98. [CrossRef]

- Constantin-Teodosiu D, Constantin D. Molecular mechanisms of muscle fatigue. Int J Mol Sci. 2021; 22: 11587. [CrossRef]

- Heetun A, Cutress RI, Copson ER. Early breast cancer: why does obesity affect prognosis? Proc Nutr Soc. 2018; 77: 369-81.

- Neto A, Boslooper-Meulenbelt K, Geelink M, van Vliet I, Post A, Joustra ML, et al.. Protein intake, fatigue and quality of life in stable outpatient kidney transplant recipients. Nutrients. 2020; 12: 2451. [CrossRef]

- Hoogeveen EK, Rothman KJ, Voskamp P, de Mutsert R, Halbesma N, Dekker FW. Obesity and risk of death or dialysis in younger and older patients on specialized pre-dialysis care. Plos One. 2017; 12: e184007. [CrossRef]

- Gregg LP, Carmody T, Le D, Bharadwaj N, Trivedi MH, Hedayati SS. Depression and the effect of Sertraline on inflammatory biomarkers in patients with nondialysis CKD. Kidney360. 2020; 1: 436-46. [CrossRef]

- Wang LJ, Wu MS, Hsu HJ, Wu IW, Sun CY, Chou CC, et al.. The relationship between psychological factors, inflammation, and nutrition in patients with chronic renal failure undergoing hemodialysis. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2012; 44: 105-18. [CrossRef]

- Pertosa G, Grandaliano G, Gesualdo L, Schena FP. Clinical relevance of cytokine production in hemodialysis. Kidney Int Suppl. 2000; 76: S104-11. [CrossRef]

- Leinau L, Murphy TE, Bradley E, Fried T. Relationship between conditions addressed by hemodialysis guidelines and non-ESRD-specific conditions affecting quality of life. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009; 4: 572-78. [CrossRef]

- Okpechi IG, Nthite T, Swanepoel CR. Health-related quality of life in patients on hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2013; 24: 519-26. [CrossRef]

- Pang M, Chen L, Jiang N, Jiang M, Wang B, Wang L, et al.. Serum 25(OH)D level is negatively associated with fatigue in elderly maintenance hemodialysis patients. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2023; 48: 231-40.

- Buchanan S, Combet E, Stenvinkel P, Shiels PG. Klotho, aging, and the failing kidney. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020; 11: 560.

- Zu Y, Lu X, Yu Q, Yu L, Li H, Wang S. Higher postdialysis lactic acid is associated with postdialysis fatigue in maintenance of hemodialysis patients. Blood Purif. 2020; 49: 535-41. [CrossRef]

- Rachoin JS, Weisberg LS, McFadden CB. Treatment of lactic acidosis: appropriate confusion. J Hosp Med. 2010; 5: E1-07. [CrossRef]

- Kristensen M, Albertsen J, Rentsch M, Juel C. Lactate and force production in skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 2005; 562: 521-26. [CrossRef]

- Lien AS, Hwang JS, Jiang YD. Diabetes related fatigue sarcopenia, frailty. J Diabetes Investig. 2018; 9: 3-04. [CrossRef]

- Qiao Y, Martinez-Amezcua P, Wanigatunga AA, Urbanek JK, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, et al.. Association Between Cardiovascular Risk and Perceived Fatigability in Mid-to-Late Life. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019; 8: e13049. [CrossRef]

- Madouros N, Jarvis S, Saleem A, Koumadoraki E, Sharif S, Khan S. Is there an association between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and chronic renal failure? Cureus. 2022; 14: e26149.

- Knobbe TJ, Kremer D, Eisenga MF, van Londen M, Gomes-Neto AW, Douwes RM, et al.. Airflow limitation, fatigue, and health-related quality of life in kidney transplant recipients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021; 16: 1686-94. [CrossRef]

- Peters JB, Heijdra YF, Daudey L, Boer LM, Molema J, Dekhuijzen PN, et al.. Course of normal and abnormal fatigue in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and its relationship with domains of health status. Patient Educ Couns. 2011; 85: 281-85. [CrossRef]

- Ebadi Z, Goertz Y, Van Herck M, Janssen D, Spruit MA, Burtin C, et al.. The prevalence and related factors of fatigue in patients with COPD: a systematic review. Eur Respir Rev. 2021; 30: 200298. [CrossRef]

- Unruh ML, Levey AS, D'Ambrosio C, Fink NE, Powe NR, Meyer KB. Restless legs symptoms among incident dialysis patients: association with lower quality of life and shorter survival. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004; 43: 900-09. [CrossRef]

- Pisoni RL, Wikstrom B, Elder SJ, Akizawa T, Asano Y, Keen ML, et al.. Pruritus in haemodialysis patients: International results from the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006; 21: 3495-505. [CrossRef]

- van der Willik EM, Lengton R, Hemmelder MH, Hoogeveen EK, Bart H, van Ittersum FJ, et al.. Itching in dialysis patients: impact on health-related quality of life and interactions with sleep problems and psychological symptoms-results from the RENINE/PROMs registry. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2022; 37: 1731-41. [CrossRef]

- Wang SY, Zang XY, Liu JD, Cheng M, Shi YX, Zhao Y. Indicators and correlates of psychological disturbance in Chinese patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis: a cross-sectional study. Int Urol Nephrol. 2015; 47: 679-89. [CrossRef]

- Davey CH, Webel AR, Sehgal AR, Voss JG, Hsiao CP, Darrah R, et al.. Genetic correlates of fatigue in individuals with end stage renal disease. West J Nurs Res. 2020; 42: 1042-49. [CrossRef]

- Bai YL, Lai LY, Lee BO, Chang YY, Chiou CP. The impact of depression on fatigue in patients with haemodialysis: a correlational study. J Clin Nurs. 2015; 24: 2014-22. [CrossRef]

- Tangvoraphonkchai K, Davenport A. Extracellular water excess and increased self-reported fatigue in chronic hemodialysis patients. Ther Apher Dial. 2018; 22: 152-59. [CrossRef]

- Wong DF, Xuesong H, Poon A, Lam AY. Depression literacy among Chinese in Shanghai, China: a comparison with Chinese-speaking Australians in Melbourne and Chinese in Hong Kong. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012; 47: 1235-42. [CrossRef]

- Losso RL, Minhoto GR, Riella MC. Sleep disorders in patients with end-stage renal disease undergoing dialysis: comparison between hemodialysis, continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis and automated peritoneal dialysis. Int Urol Nephrol. 2015; 47: 369-75. [CrossRef]

- Scherer JS, Combs SA, Brennan F. Sleep disorders, restless legs syndrome, and uremic pruritus: diagnosis and treatment of common symptoms in dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017; 69: 117-28. [CrossRef]

- Benetou S, Alikari V, Vasilopoulos G, Polikandrioti M, Kalogianni A, Panoutsopoulos GI, et al.. Factors associated with insomnia in patients undergoing hemodialysis. Cureus. 2022; 14: e22197. [CrossRef]

- Besedovsky L, Lange T, Haack M. The sleep-immune crosstalk in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2019; 99: 1325-80. [CrossRef]

- You Q, Bai DX, Wu CX, Chen H, Hou CM, Gao J. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Postdialysis Fatigue in Patients Under Maintenance Hemodialysis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci). 2022; 16: 292-98. [CrossRef]

- Zazzeroni L, Pasquinelli G, Nanni E, Cremonini V, Rubbi I. Comparison of quality of life in patients undergoing hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2017; 42: 717-27. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka M, Ishibashi Y, Hamasaki Y, Kamijo Y, Idei M, Kawahara T, et al.. Health-related quality of life on combination therapy with peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis in comparison with hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis: a cross-sectional study. Perit Dial Int. 2020; 40: 462-69. [CrossRef]

- Bello AK, Okpechi IG, Osman MA, Cho Y, Cullis B, Htay H, et al.. Epidemiology of peritoneal dialysis outcomes. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2022; 18: 779-93. [CrossRef]

- Kong J, Davies M, Mount P. The importance of residual kidney function in haemodialysis patients. Nephrology (Carlton). 2018; 23: 1073-80. [CrossRef]

- Kimura H, Tanaka K, Saito H, Iwasaki T, Oda A, Watanabe S, et al.. Association of polypharmacy with kidney disease progression in adults with CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021; 16: 1797-804. [CrossRef]

- Andrade C. Beta-blockers and the risk of new-onset depression: meta-analysis reassures, but the Jury Is still out. J Clin Psychiatry. 2021; 82: 21f-14095f.

- Lengton R, W SR, Nadort E, van Rossum EF, Dekker FW, Siegert CE, et al.. Association between lipophilic beta-blockers and depression in diabetic patients on chronic dialysis. Clin Med Insights Endocrinol Diabetes. 2022; 15: 722978774.

- Adams SM, Miller KE, Zylstra RG. Pharmacologic management of adult depression. Am Fam Physician. 2008; 77: 785-92.

- Pfeffer MA, Burdmann EA, Chen CY, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, Eckardt KU, et al.. A trial of darbepoetin alfa in type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2009; 361: 2019-32. [CrossRef]

- Minutolo R, Garofalo C, Chiodini P, Aucella F, Del VL, Locatelli F, et al.. Types of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents and risk of end-stage kidney disease and death in patients with non-dialysis chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2021; 36: 267-74. [CrossRef]

- Szczech LA, Barnhart HX, Inrig JK, Reddan DN, Sapp S, Califf RM, et al.. Secondary analysis of the CHOIR trial epoetin-alpha dose and achieved hemoglobin outcomes. Kidney Int. 2008; 74: 791-98. [CrossRef]

- Natale P, Palmer SC, Jaure A, Hodson EM, Ruospo M, Cooper TE, et al.. Hypoxia-inducible factor stabilisers for the anaemia of chronic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022; 8: D13751. [CrossRef]

- Siami G, Clinton ME, Mrak R, Griffis J, Stone W. Evaluation of the effect of intravenous L-carnitine therapy on function, structure and fatty acid metabolism of skeletal muscle in patients receiving chronic hemodialysis. Nephron. 1991; 57: 306-13. [CrossRef]

- Wasserstein AG. L-carnitine supplementation in dialysis: treatment in quest of disease. Semin Dial. 2013; 26: 11-15. [CrossRef]

- Fatouros IG, Douroudos I, Panagoutsos S, Pasadakis P, Nikolaidis MG, Chatzinikolaou A, et al.. Effects of L-carnitine on oxidative stress responses in patients with renal disease. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010; 42: 1809-18. [CrossRef]

- Kraut JA, Kurtz I. Metabolic acidosis of CKD: diagnosis, clinical characteristics, and treatment. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005; 45: 978-93. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira EA, Zheng R, Carter CE, Mak RH. Cachexia/Protein energy wasting syndrome in CKD: causation and treatment. Semin Dial. 2019; 32: 493-99. [CrossRef]

- Abramowitz MK, Melamed ML, Bauer C, Raff AC, Hostetter TH. Effects of oral sodium bicarbonate in patients with CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013; 8: 714-20. [CrossRef]

- Hedayati SS, Gregg LP, Carmody T, Jain N, Toups M, Rush AJ, et al.. Effect of Sertraline on depressive symptoms in patients with chronic kidney disease without dialysis dependence: the CAST randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017; 318: 1876-90.

- Cooper JA, Tucker VL, Papakostas GI. Resolution of sleepiness and fatigue: a comparison of bupropion and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in subjects with major depressive disorder achieving remission at doses approved in the European Union. J Psychopharmacol. 2014; 28: 118-24. [CrossRef]

- Grigoriou SS, Krase AA, Karatzaferi C, Giannaki CD, Lavdas E, Mitrou GI, et al.. Long-term intradialytic hybrid exercise training on fatigue symptoms in patients receiving hemodialysis therapy. Int Urol Nephrol. 2021; 53: 771-84. [CrossRef]

- Malagoni AM, Catizone L, Mandini S, Soffritti S, Manfredini R, Boari B, et al.. Acute and long-term effects of an exercise program for dialysis patients prescribed in hospital and performed at home. J Nephrol. 2008; 21: 871-78.

- Ghafourifard M, Mehrizade B, Hassankhani H, Heidari M. Hemodialysis patients perceived exercise benefits and barriers: the association with health-related quality of life. Bmc Nephrol. 2021; 22: 94. [CrossRef]

- Kosmadakis GC, Bevington A, Smith AC, Clapp EL, Viana JL, Bishop NC, et al.. Physical exercise in patients with severe kidney disease. Nephron Clin Pract. 2010; 115: c7-16. [CrossRef]

- Anding-Rost K, Von Gersdorff G, Von Korn P, Ihorst G, Josef A, Kaufmann M, et al.. Exercise during hemodialysis in patients with chronic kidney failure. NEJM Evidence. 2023; 2. [CrossRef]

- Natale P, Palmer SC, Ruospo M, Saglimbene VM, Rabindranath KS, Strippoli GF. Psychosocial interventions for preventing and treating depression in dialysis patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019; 12: D4542. [CrossRef]

- Ng CZ, Tang SC, Chan M, Tran BX, Ho CS, Tam WW, et al.. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of cognitive behavioral therapy for hemodialysis patients with depression. J Psychosom Res. 2019; 126: 109834. [CrossRef]

- Chan R, Dear BF, Titov N, Chow J, Suranyi M. Examining internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy for patients with chronic kidney disease on haemodialysis: a feasibility open trial. J Psychosom Res. 2016; 89: 78-84. [CrossRef]

- Erdley SD, Gellis ZD, Bogner HA, Kass DS, Green JA, Perkins RM. Problem-solving therapy to improve depression scores among older hemodialysis patients: a pilot randomized trial. Clin Nephrol. 2014; 82: 26-33. [CrossRef]

- Nadort E, Schouten RW, Boeschoten RE, Smets Y, Chandie SP, Vleming LJ, et al.. Internet-based treatment for depressive symptoms in hemodialysis patients: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2022; 75: 46-53. [CrossRef]

- Sajadi M, Gholami Z, Hekmatpou D, Soltani P, Haghverdi F. Cold dialysis solution for hemodialysis patients with fatigue: a cross-over study. Iran J Kidney Dis. 2016; 10: 319-24.

- Azar AT. Effect of dialysate temperature on hemodynamic stability among hemodialysis patients. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2009; 20: 596-603.

- Roumelioti ME, Unruh ML. Lower dialysate temperature in hemodialysis: is it a cool idea? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015; 10: 1318-20.

- Cooke B, Ernst E. Aromatherapy: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2000; 50: 493-96.

- Zhang C, Mu H, Yang YF, Zhang Y, Gou WJ. Effect of aromatherapy on quality of life in maintenance hemodialysis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ren Fail. 2023; 45: 2164202. [CrossRef]

- Natale P, Ju A, Strippoli GF, Craig JC, Saglimbene VM, Unruh ML, et al.. Interventions for fatigue in people with kidney failure requiring dialysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023; 8: D13074. [CrossRef]

- Wang Q, Wei L, Luo Y, Lin L, Deng C, Hu P, et al.. Effectiveness of aromatherapy on ameliorating fatigue in adults: a meta-analysis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2022; 2022: 1141411. [CrossRef]

- Farrar AJ, Farrar FC. Clinical aromatherapy. Nurs Clin North Am. 2020; 55: 489-504. [CrossRef]

- Weisbord SD, Fried LF, Mor MK, Resnick AL, Unruh ML, Palevsky PM, et al.. Renal provider recognition of symptoms in patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007; 2: 960-67. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).