Submitted:

10 December 2024

Posted:

12 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

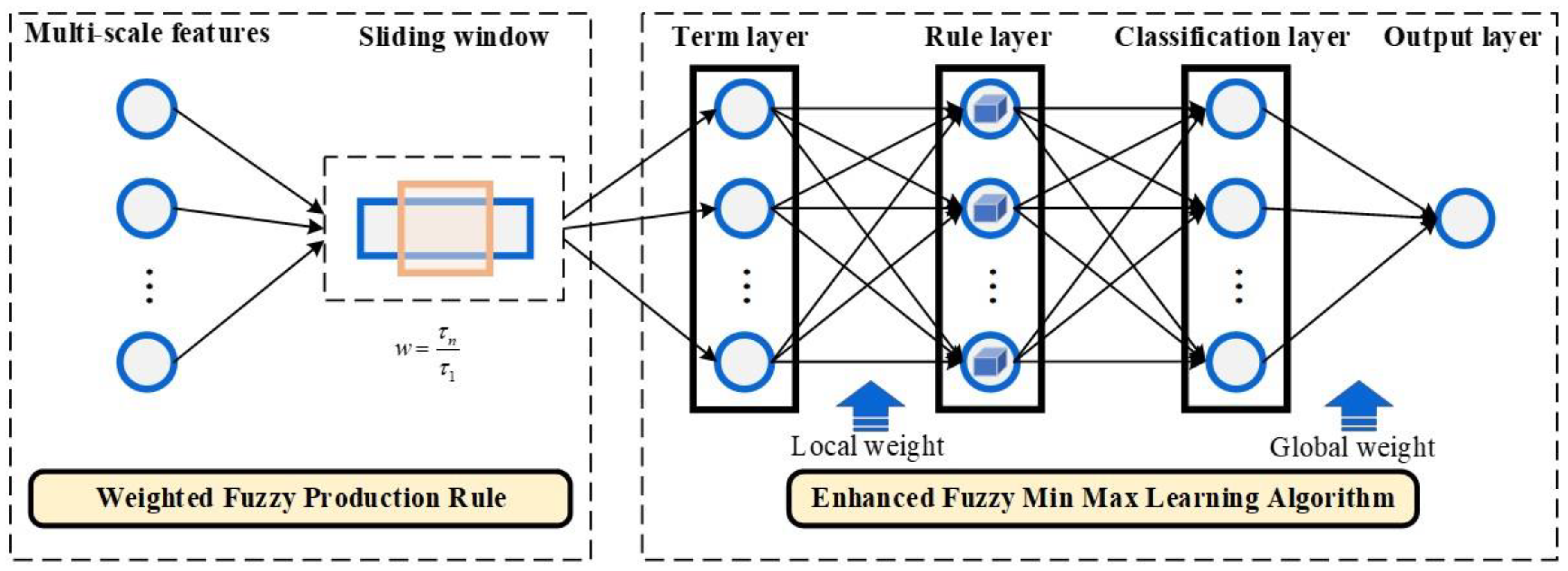

This paper proposes a multiple time-scale pattern classification method based on a refinement fuzzy min-max neural network (RFMMNN). The purpose is to provide the suitable hyperboxes for RFMMNN to cover the multiple time-scale input patterns in the online learning algorithms. Firstly, a new fuzzy production rule (FPR) with local and global weights is established based on the multi-time scale input pattern. This FPR can directly use multi-scale features for pattern classification. Secondly, a fuzzy min-max network (FMM) with an enhanced learning algorithm is developed, and the FMM is used to refine the local and global parameters of FPR. Thirdly, a pruning strategy is designed to prevent the useless FPR generation in the learning process, and further to improve the accuracy of classification. The efficacy of FFMMNN is evaluated using benchmark data sets and a real-world task. The results are better than those from various FMM-based models, such as support vector machine-based, Bayesian-based, decision tree-based, fuzzy-based, and neural-based classifiers.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- A new classification (membership) function is established based on multiple time-scale characteristics, where local and global weights are established based on the multiple time-scale input pattern. Then it can directly utilize origin features for pattern classification.

- An improved fuzzy min-max learning algorithm is proposed. The approximation of the FMM is utilized to improve the refinement of the local and global parameters in FPR, which ensures accurate classification.

- A pruning strategy is designed. This strategy concentrates on removing redundant fuzzy rules represented by hyperboxes, thereby enhancing the classification ability of FPR-FMM while eliminating the influences of redundant information.

2. Problem Description

3. FPR-FMM

3.1. Weighted Fuzzy Production Rule (WFPR)

3.2. FPR-FMM architecture

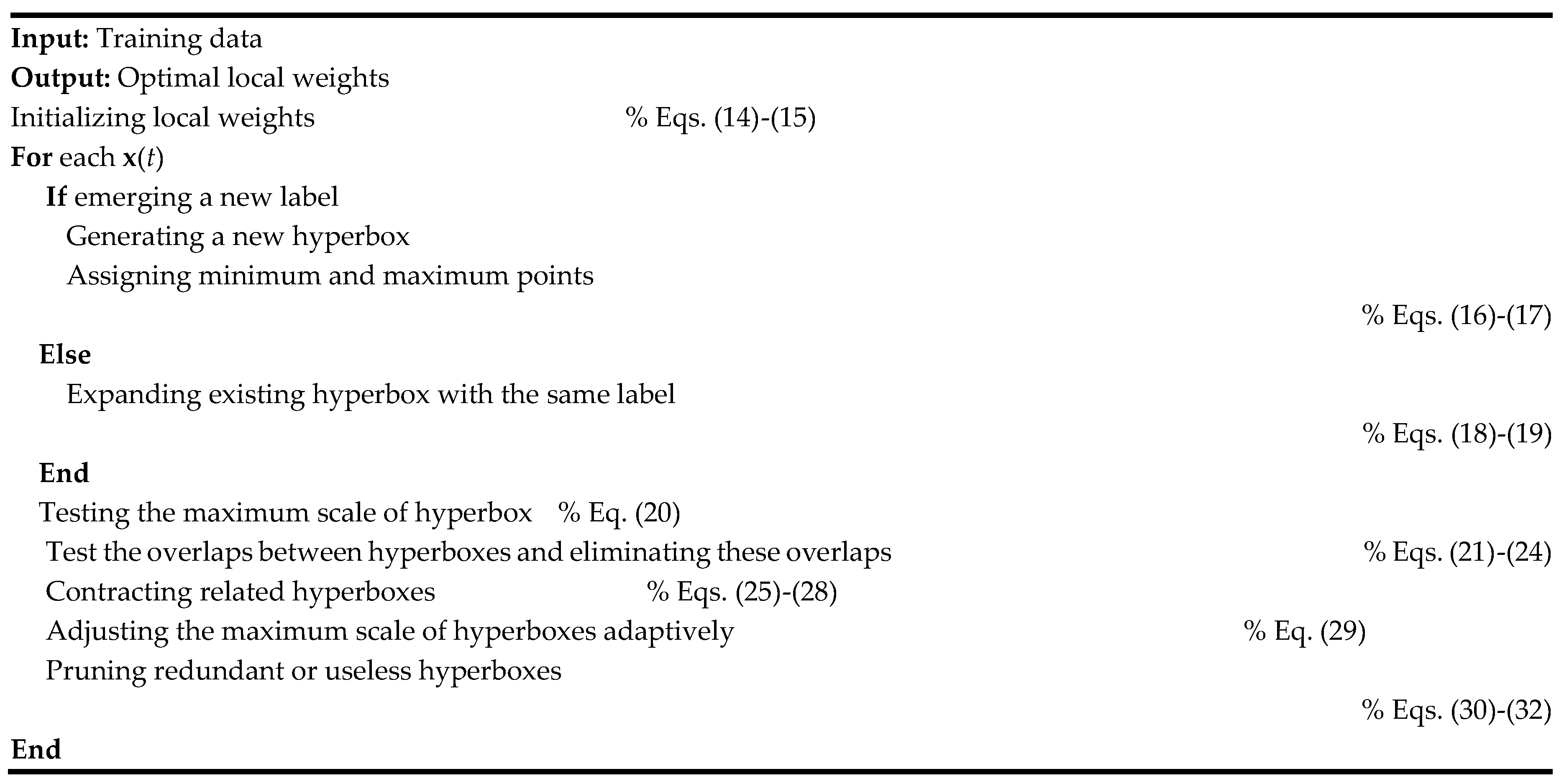

4. An Enhanced Fuzzy Min Max Learning Algorithm

4.1. Learning Algorithm

- Initialization: The minimum point vj and maximum point wj of the jth hyperbox are initialized as follows:

- 2.

- Hyperbox expansion: The expansion process is used to determine the number of hyperboxes and their minimum and maximum points. According to the input mode x(t) at time t, the membership degree is calculated, and the hyperbox Bj(t) with the largest membership degree is selected for expansion. In this case, adjust Bj(t) according to Eqs. (18) and (19).

- 3.

- Overlap test: FPR-FMM stipulates that overlap between hyperboxes of the same type is allowed, while the overlap between hyperboxes of different types is not allowed. Assuming that the hyperbox Bj(t) is expanded in the previous step, there are two cases to select other hyperboxes that need to be tested for overlap with Bj(t). Suppose any hyperbox Bk(t) and Bj(t) are tested for overlap, then:

- 4.

- Hyperbox contraction: If there is overlap between different types of hyperboxes, the contracting process will reduce the overlap. When ∆>0, only need to adjust the ∆th dimension between the two hyperboxes. The hyperbox contracts as follows:

- 5.

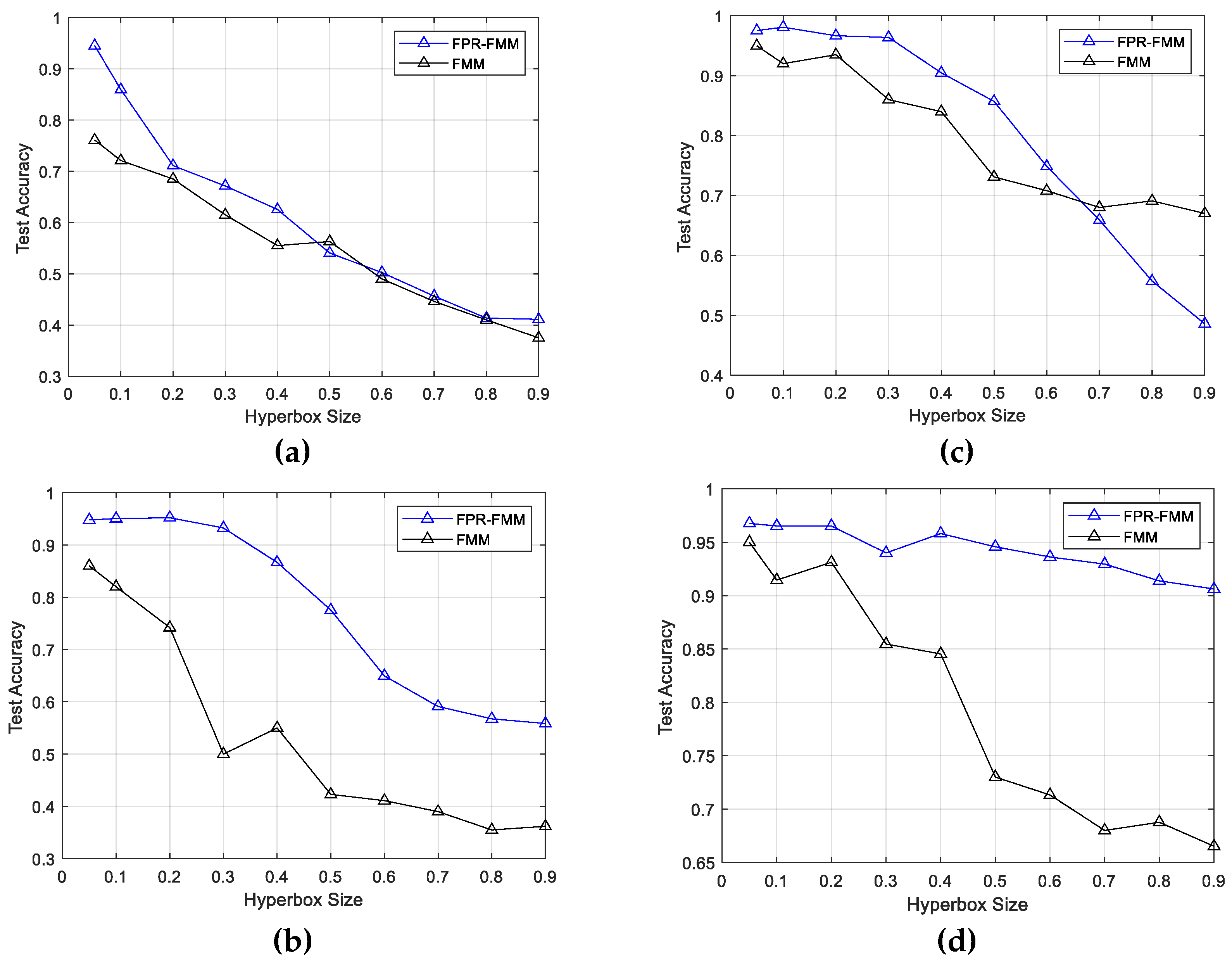

- Adaptive adjustment of maximum scale: For hyperbox, the maximum scale Θ has an important influence on the classification of the network. The fixed parameters may lead to a reduction in classification accuracy. When the parameter Θ is large, the number of error classifications will increase, especially when there are complex overlapping classes; on the contrary, when the parameter Θ is small, it will cause a lot of unnecessary expansion of the hyperbox. Therefore, the parameter Θ needs to be dynamically adjusted to improve the classification accuracy of the model. To dynamically adjust the parameters, after each training data is input, the dynamic adjustment formula of parameter Θ is as follows:

4.1. Pruning of hyperboxes based on confidence factor

5. Illustrated Examples

5.1. Case Study I

5.2. Case Study II

5.3. Case Study III

5.4. Case Study IV

6. Conclusion

References

- T. Ojala, M. Pietikainen and T. Maenpaa.: Multiresolution Gray-scale and Rotation Invariant Texture Classification with Local Binary Patterns. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 24(7), 971-987 (2002). [CrossRef]

- A. Jain, R. Duin, and J. Mao.: Statistical Pattern Recognition: A Review. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 22(1), 4-37 (2000).

- G. Huang, H. Zhou, X. Ding, and R. Zhang.: Extreme Learning Machine for Regression and Multiclass Classification. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Part B (Cybernetics), 42(2), 513-529 (2012). doi:10.1109/tsmcb.2011.2168604.

- V. Badrinarayanan, A. Kendall, and R. Cipolla.: SegNet: A Deep Convolutional Encoder-Decoder Architecture for Image Segmentation. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 39(12), 2481-2495 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Y. Huang, F. Xiao.: Higher Order Belief Divergence with Its Application in Pattern Classification. Information Sciences, 635, 1-24, (2023). [CrossRef]

- H. Li and L. Zhang.: A Bilevel Learning Model and Algorithm for Self-Organizing Feed-Forward Neural Networks for Pattern Classification. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems, 32(11), 4901-4915 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Z. Akram-Ali-Hammouri, M. Fernández-Delgado, E. Cernadas, and S. Barro.: Fast Support Vector Classification for Large-Scale Problems. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 44(10), 6184-6195 (2022).

- Q. Xue, Y. Zhu, and J. Wang.: Joint Distribution Estimation and Naïve Bayes Classification Under Local Differential Privacy. IEEE Transactions on Emerging Topics in Computing, 9(4), 2053-2063 (2021). [CrossRef]

- T. Liao, Z. Lei, T. Zhu, et. al.: Deep Metric Learning for K-Nearest Neighbor Classification. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering, 35(1), 264-275 (2023).

- J. Liang, Z. Qin, S. Xiao, L. Ou, and X. Lin.: Efficient and Secure Decision Tree Classification for Cloud-Assisted Online Diagnosis Services. IEEE Transactions on Dependable and Secure Computing, 18(4), 1632-1644 (2021). [CrossRef]

- B. Wang, L. Gao, and Z. Juan.: Travel Mode Detection Using GPS Data and Socioeconomic Attributes Based on a Random Forest Classifier. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, 19(5), 1547-1558 (2018). doi:10.1109/tits.2017.2723523.

- G. Nápoles, A. Jastrzębska, Y. Salgueiro.: Pattern Classification with Evolving Long-Term Cognitive Networks. Information Sciences, 548, 461-478 (2021). [CrossRef]

- P. Simpson.: Fuzzy Min-Max Neural Networks - Part 1: Classification. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks,” 3(5) 776-786 (1992).

- P. Simpson.: Fuzzy Min-Max Neural Networks - Part 2: Clustering. IEEE Transactions on Fuzzy Systems, 1(1), 33, (1993). [CrossRef]

- B. Gabrys, A. Bargiela.: General Fuzzy Min-Max Neural Network for Clustering and Classification. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks, 11(3), 769-783 (2000). [CrossRef]

- J. Liu, Z. Yu, D. Ma.: An Adaptive Fuzzy Min-Max Neural Network Classifier Based on Principle Component Analysis and Adaptive Genetic Algorithm. Mathematical Problems in Engineering, 1-21, (2012). [CrossRef]

- M. Mohammed, C. Lim.: An Enhanced Fuzzy Min–Max Neural Network for Pattern Classification. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks & Learning Systems, 26(3), 417-429 (2014). [CrossRef]

- T. Khuat, B. Gabrys.: Accelerated Learning Algorithms of General Fuzzy Min-Max Neural Network Using A Novel Hyperbox Selection Rule. Information Sciences, 547, 887-909 (2021). [CrossRef]

- A. Quteishat, C. Lim, K. Tan.: A Modified Fuzzy Min-Max Neural Network with A Genetic-Algorithm-Based Rule Extractor for Pattern Classification. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics - Part A: Systems and Humans, 40(3), 641-650 (2010). [CrossRef]

- A. Nandedkar, P. Biswas.: A Fuzzy Min-Max Neural Network Classifier with Compensatory Neuron Architecture. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks, 18(1), 42-54 (2007). [CrossRef]

- H. Zhang, J. Liu, D. Ma, et al.: Data-Core-Based Fuzzy Min–Max Neural Network for Pattern Classification. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks, 22(12), 339 – 2352 (2011). [CrossRef]

- R. Davtalab, M. Dezfoulian, M. Mansoorizadeh.: Multi-Level Fuzzy Min-Max Neural Network Classifier. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems, 25(3), 470-482 (2014).

- A. Kumar, P. Prasad.: Scalable Fuzzy Rough Set Reduct Computation Using Fuzzy Min-Max Neural Network Preprocessing. IEEE Transactions on Fuzzy Systems, 28(5), 953-964 (2020). [CrossRef]

| Data set | Sample size | Feature dimensionality | Class size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Iris | 150 | 4 | 3 |

| Glass | 214 | 9 | 6 |

| Ionosphere | 351 | 34 | 2 |

| Sonar | 208 | 60 | 2 |

| Wine | 178 | 13 | 3 |

| WBC | 699 | 10 | 2 |

| Heart | 270 | 13 | 2 |

| Soybean | 307 | 35 | 4 |

| % | FMM | FPR-FMM | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | Max | Avg. | Min | Max | Avg. | |

| 30 | 2.01 | 7.3 | 4.67 | 2.01 | 6 | 3.46 |

| 40 | 2.01 | 6.7 | 4.33 | 0.67 | 4.67 | 2.62 |

| 50 | 1.34 | 4 | 2.06 | 0.67 | 3.33 | 1.46 |

| 60 | 0 | 3.33 | 1.68 | 0 | 2.67 | 1.34 |

| 70 | 0 | 2.67 | 1.27 | 0 | 2 | 0.9 |

| Θ | FMM | FPR-FMM | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | Mean | Max | Avg. Hyperbox No. | Min | Mean | Max | Avg. Hyperbox No. | |

| 0.4 | 50.79 | 62.03 | 73.27 | 127 | 68.23 | 73.82 | 79.41 | 127 |

| 0.5 | 52.14 | 60.86 | 69.58 | 53 | 75.57 | 77.89 | 80.20 | 53 |

| 0.6 | 69.13 | 75.38 | 81.62 | 21 | 73.84 | 79.91 | 85.97 | 21 |

| Methods | WBC | Heart | Soybean |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gaussian RBF kernel | 92.36 | 80.31 | 91.67 |

| Linear kernel | 86.24 | 82.52 | 94.85 |

| Polynomial kernel | 90.12 | 73.96 | 95.71 |

| FPR-FMM | 94.65 | 86.27 | 97.40 |

| Methods | Iris | WBC | Wine | Glass |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naive Bayes | 95.45±0.50 | 94.92±1.20 | 93.67±2.24 | 46.28±0.32 |

| C4.5 | 95.13±0.20 | 94.71±0.09 | 91.14±5.12 | 67.90±0.50 |

| SMO | 96.69±2.58 | 97.51±0.97 | 97.87±2.11 | 58.85±6.58 |

| Fuzzy gain measure | 96.88±2.40 | 98.14±0.90 | 98.36±1.26 | 69.14±4.69 |

| HHONC | 97.46±2.31 | 97.17±1.17 | 97.88±2.29 | 56.50±7.58 |

| FPR-FMM | 96.14±2.47 | 97.49±0.26 | 99.62±1.31 | 65.80±0.71 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).