Submitted:

09 December 2024

Posted:

10 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Why Chosen Ensemble Learning Techniques over Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)?

2. Related Works

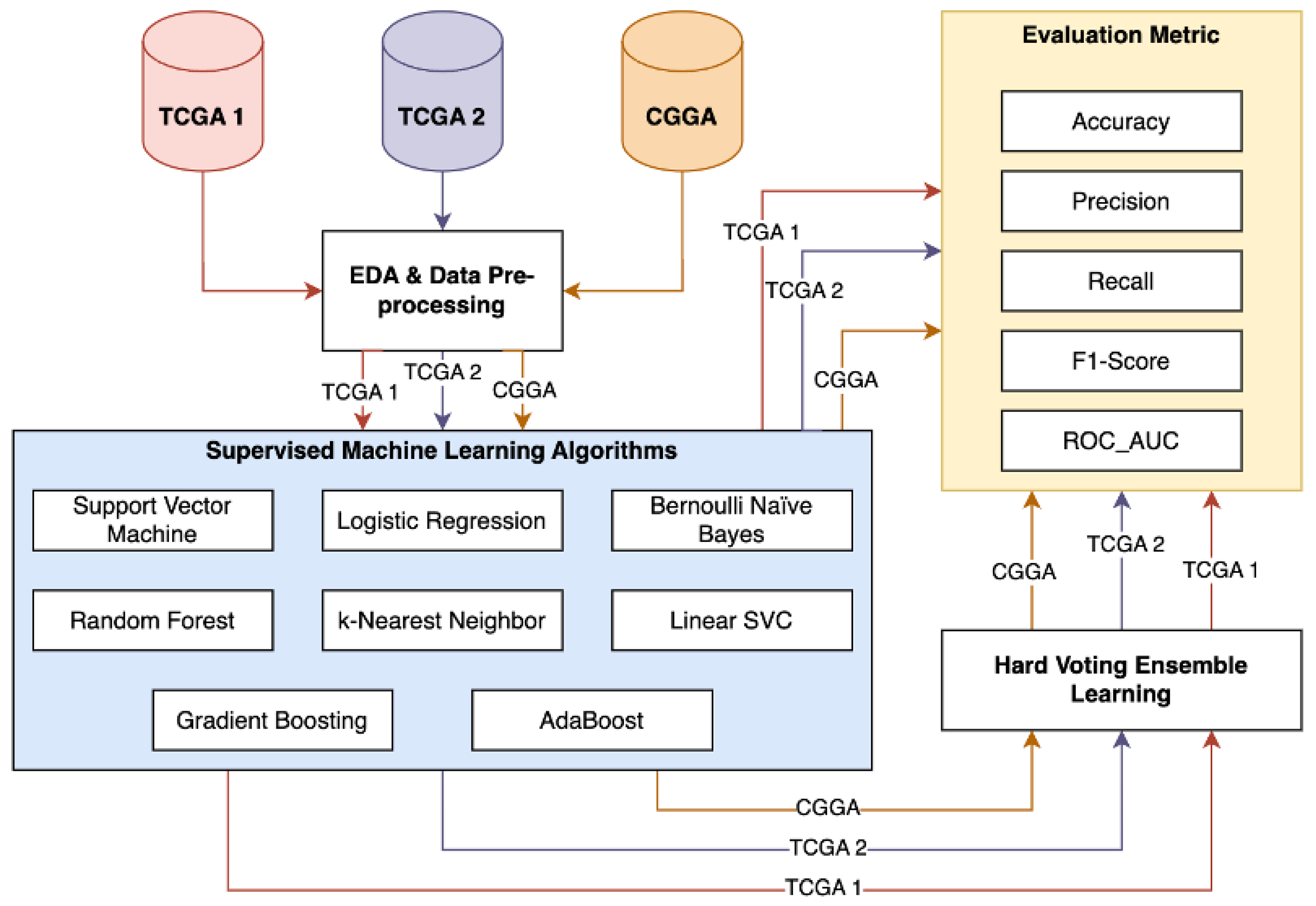

3. Methodology

3.1. Machine Learning Models

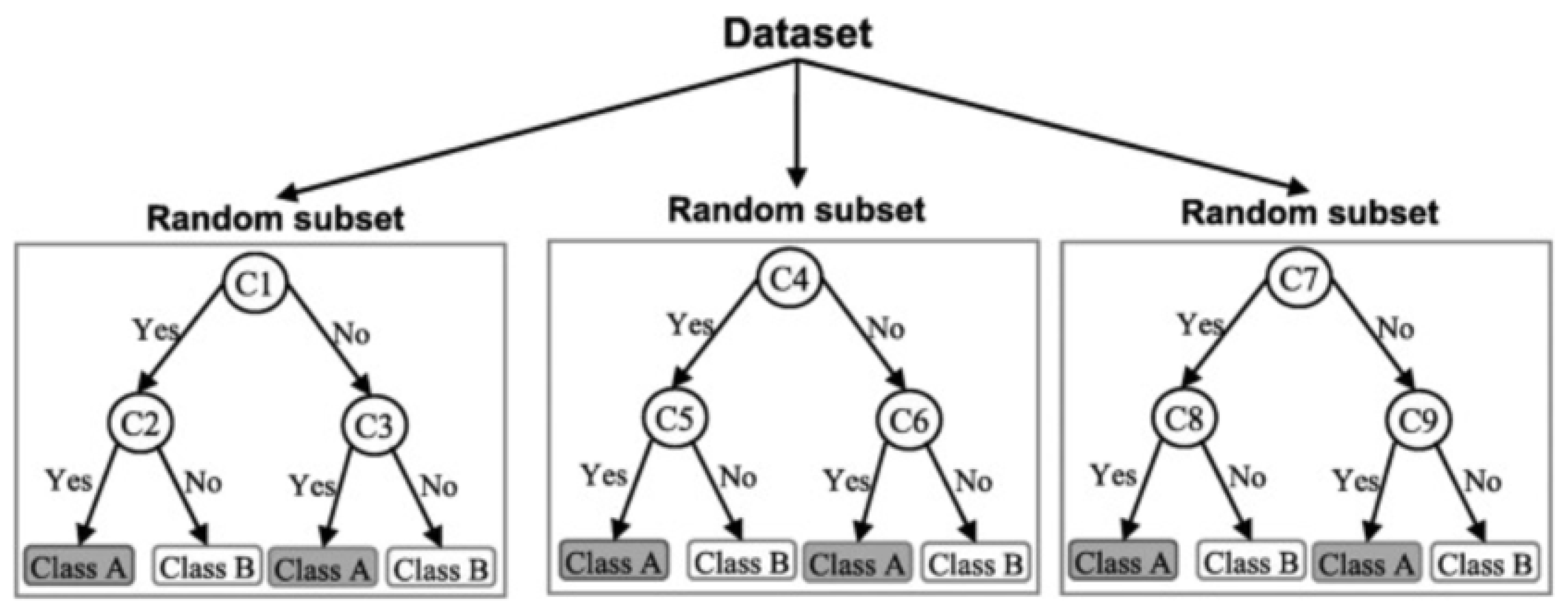

3.1.1. Random Forest

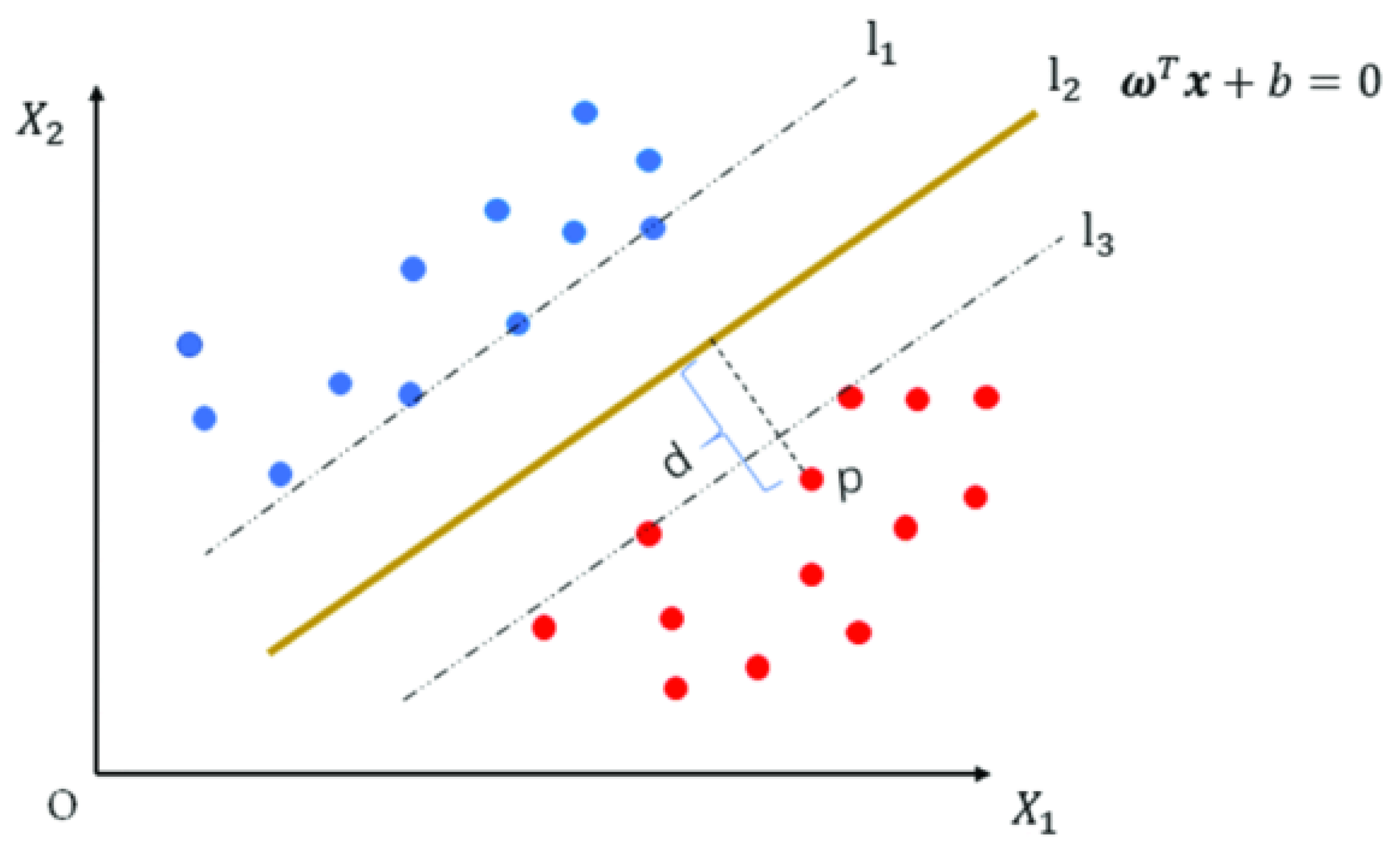

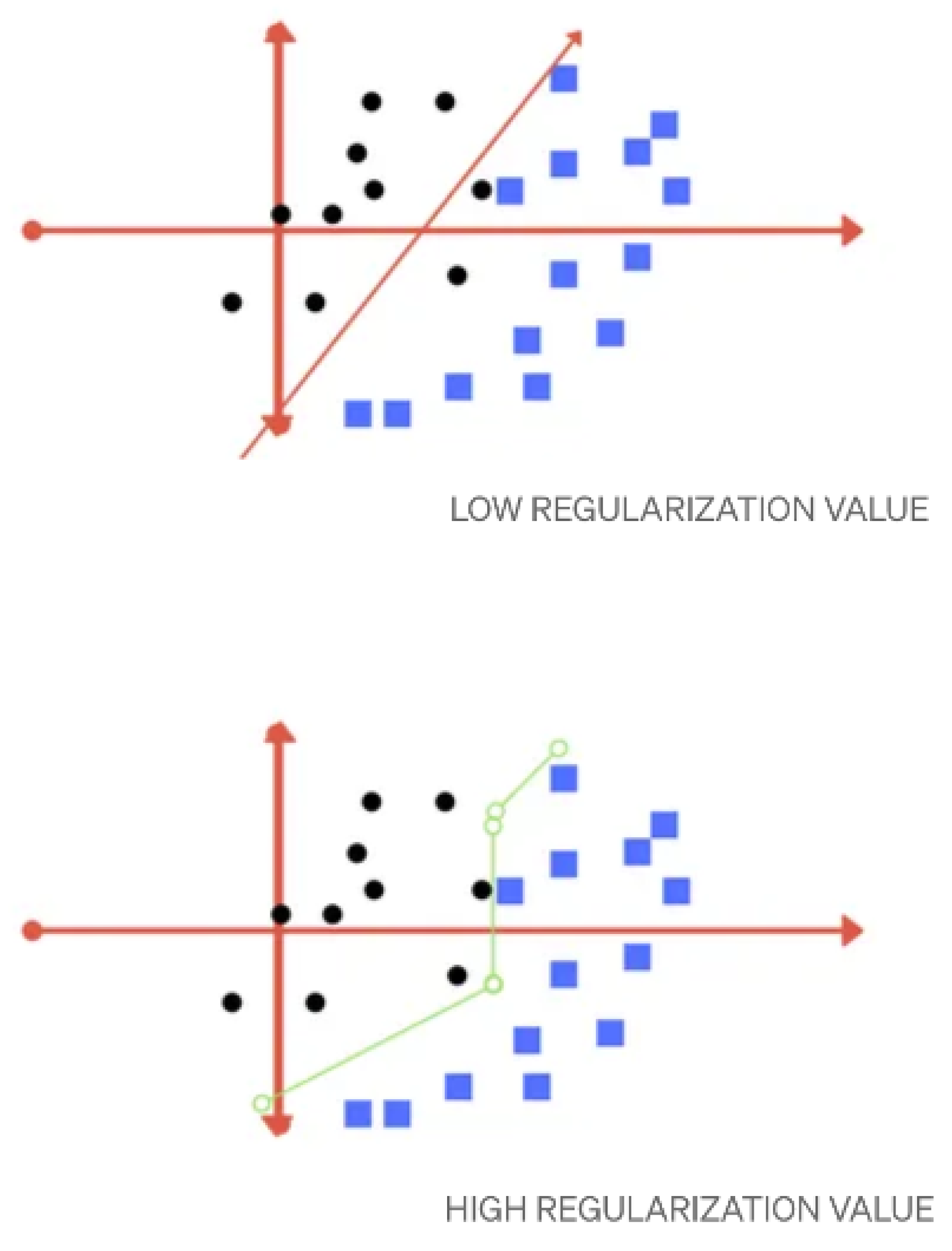

3.1.2. Support Vector Machine

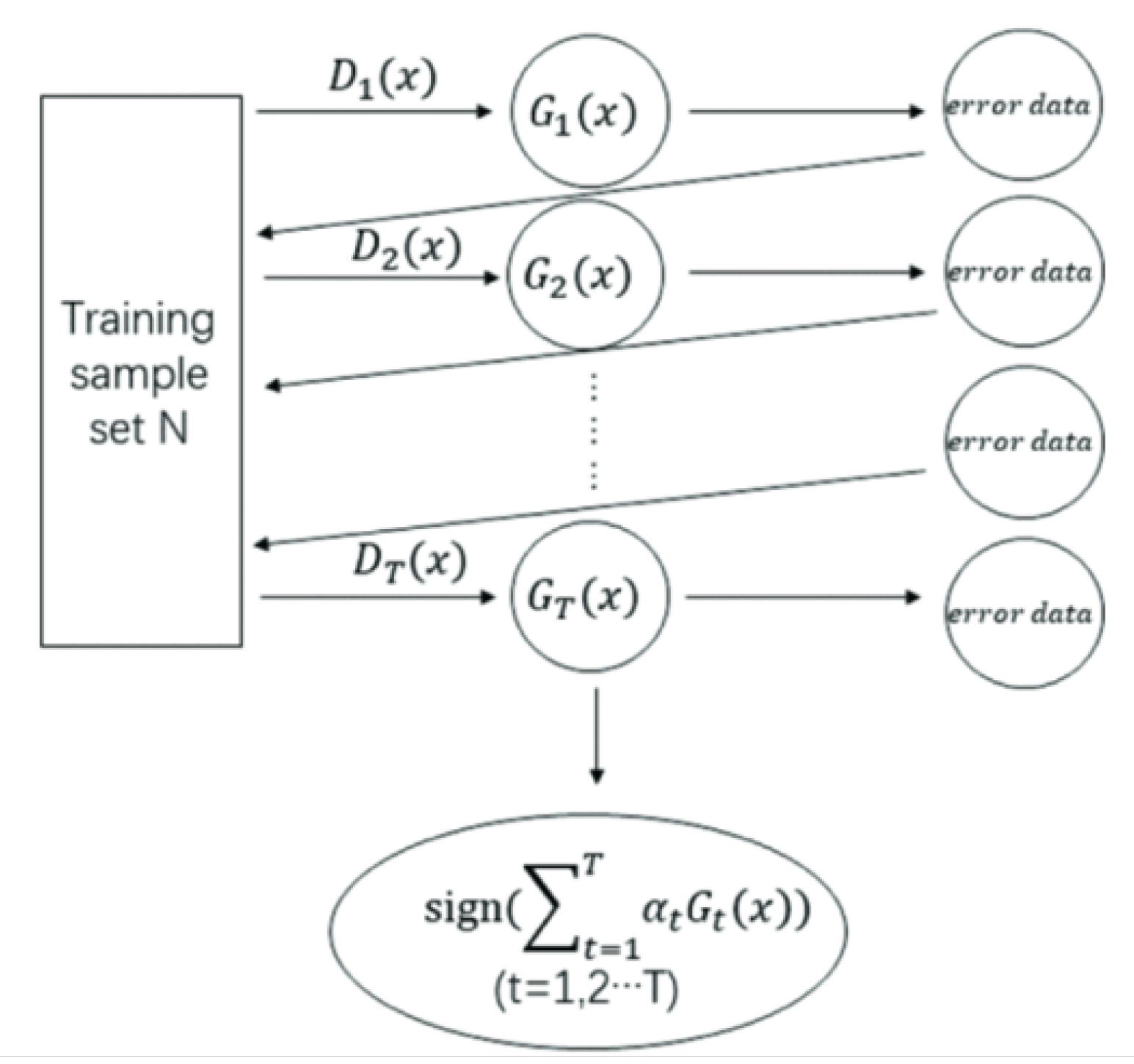

3.1.3. Adaptive Boosting

3.1.4. Logistic Regression

3.1.5. Gradient Boosting

3.1.6. Linear SVC

3.1.7. Bernoulli Naïve Bayes

3.1.8. k-Nearest Neighbors

4. Experiments

4.1. Training Setting

4.1.1. Pipeline Framework

4.1.2. GridSearchCV

4.2. Preprocessing

4.2.1. Data Cleaning

4.2.2. Handling of Categorical Variables

4.2.3. Missing Values

4.3. Data Balancing Techniques

4.3.1. Weighted Loss Functions

4.3.2. Under-Sampling

4.3.3. Comparison of Techniques

4.3.4. Hyper Parameters

- Random Forest: We tuned one hyper parameter for RF model which is ’n_estimators’. This allows us to set the number of decision trees in the forest. The best number of trees for TCGA 1, CGGA, and TCGA 2 datasets are 39, 97, and 138 respectively. We chose ’entropy’ for ’criterion’ and ’sqrt’ for ’max_features’ hyper parameters.

- Support Vector Machine: For this model, we predefined the kernel which is ’RBF’. We tuned the C and gamma hyper parameters of this model. The best C for TCGA 1 dataset was 0.1, 1 for CGGA dataset, and 0.1 for TCGA 2 dataset. For gamma, the best gamma values were 10, 1, 100 for TCGA 1, CGGA, and TCGA 2 respectively.

- Adaptive Boosting: Similar to the SVC model, we tuned only two hyperparameters for the AdaBoost model: ’n_estimators’ and ’learning_rate’. For the TCGA 1 dataset, the optimal hyperparameters were a ’learning_rate’ of 0.01 and ’n_estimators’ set to 60. In the CGGA dataset, the best combination was a ’learning_rate’ of 1 and ’n_estimators’ set to 80. For the TCGA 2 dataset, the optimal values were a ’learning_rate’ of 1 and ’n_estimators’ set to 40.

- Logistic Regression: Prior to tuning this model, we set ’log_loss’ for loss parameter and ’elasticnet’ for penalty. There were 4 hyper parameters tuned which are ’eta0’, ’max_iter’, alpha, and ’l1_ratio’. Optimal ’eta0’, ’max_iter’, alpha, and ’l1_ratio’ values for CGGA were 1, 0.001, 0, and 500 respectively. For TCGA 1, the best ’eta0’ was 0.001, 1 for alpha, 0.5 for ’l1_ratio’, and 500 for ’max_iter’. The best values of ’eta0’, alpha, ’l_ratio’, and ’max_iter’ for TCGA 2 dataset were 0.001, 0.01, 0, and 500 respectively.

- Gradient Boosting: The hyper parameters that were tuned for gradient boosting were ’n_estimators’, ’learning_rate’, and ’max_depth’. The best value of ’n_estimators’ for TCGA 1, TCGA 2, and CGGA dataset were 50, 150, and 200 respectively. The optimal ’learning_rate’ values were 0.01 for TCGA 1, 0.1 for CGGA, and 0.2 for TCGA 2. The best ’max_depth’ for all dataset was 5.

- Linear SVC: C and ’max_iter’ were the hyper parameters we tuned. The best values of C and ’max_iter’ for TCGA 1 are 0.01 and 1000 respectively. For CGGA and TCGA 2, the optimal value for C was 1 and 1000 for ’max_iter’

- Bernoulli Naïve Bayes: This model’s hyper parameters that we tuned were alpha and ’binarize’. The best alpha values for CGGA, TCGA 2, and TCGA 1 were 1000, 0.01, and 10 respectively and for ’binarize’, 0.6 was the best value for TCGA 2 and CGGA dataset, while 0.4 value of ’binarize’ was the best for TCGA 1.

- k-Nearest Neighbors: ’n_neigbors’, weights, algorithm, and p were tuned to improve the model’s performance. The best values for algorithm, ’n_neighbors’, and p were ’auto’, 11, and 1 respectively for all datasets. For weights, the best value for CGGA dataset was ’distance’ and ’uniform’ for TCGA 1 and TCGA 2.

- Hard Voting Ensemble Learning: There was no hyper parameter tuned for ensemble learning. Although, we set the voting parameter to ’hard’ because we aim to find which ensemble learning set can perform the best using hard-voting method.

4.4. Hyperparameter Tuning

| Model | Tuned | Optimal | Estimated | Computational |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hyperparameters | Values | Computational Time | Cost | |

| Random Forest | n_estimators | 39, 97, 138 | 3 min | Medium |

| criterion | entropy | |||

| max_features | sqrt | |||

| Support Vector Machine | C | 0.1, 1, 0.1 | 6 min | Medium |

| gamma | 10, 1, 100 | |||

| Adaptive Boosting | n_estimators | 60, 80, 40 | 4 min | Medium |

| learning_rate | 0.01, 1, 1 | |||

| Logistic Regression | eta0 | 1, 0.001, 0.001 | 2 min | Low |

| max_iter | 500 | |||

| alpha | 0, 1, 0.01 | |||

| l1_ratio | 500, 0.5, 0 | |||

| Gradient Boosting | n_estimators | 50, 200, 150 | 8 min | High |

| learning_rate | 0.01, 0.1, 0.2 | |||

| max_depth | 5 | |||

| Linear SVC | C | 0.01, 1, 1 | 5 min | Medium |

| max_iter | 1000 | |||

| Bernoulli Naïve Bayes | alpha | 1000, 0.01, 10 | 1 min | Low |

| binarize | 0.6, 0.4 | |||

| k-Nearest Neighbors | n_neighbors | 11 | ||

| weights, | distance/uniform, | |||

| algorithm, p | auto, 1 | 4 min | Medium | |

| Hard Voting | ||||

| Ensemble Learning | Voting | hard | 2 min | Low |

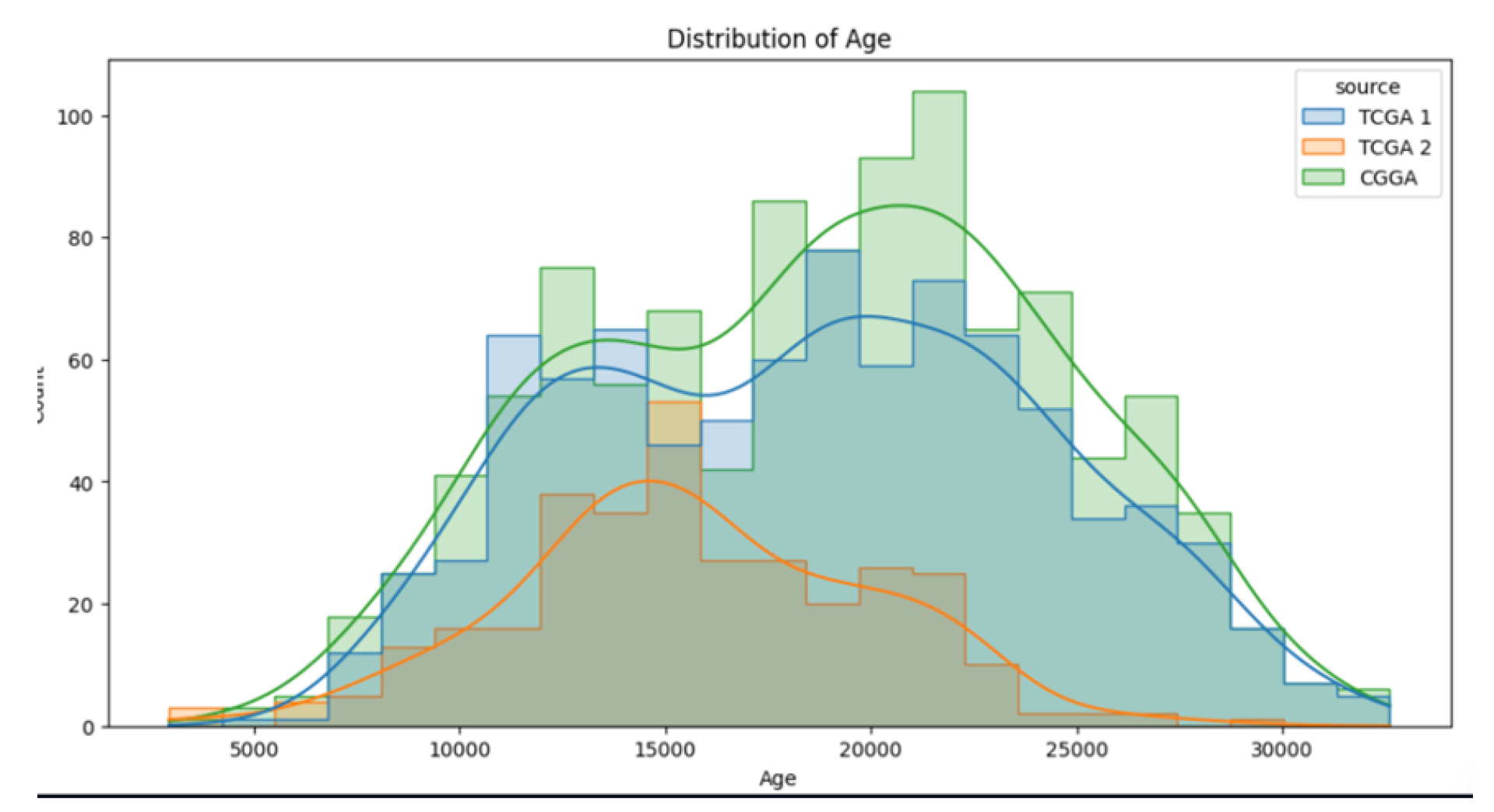

4.5. Datasets

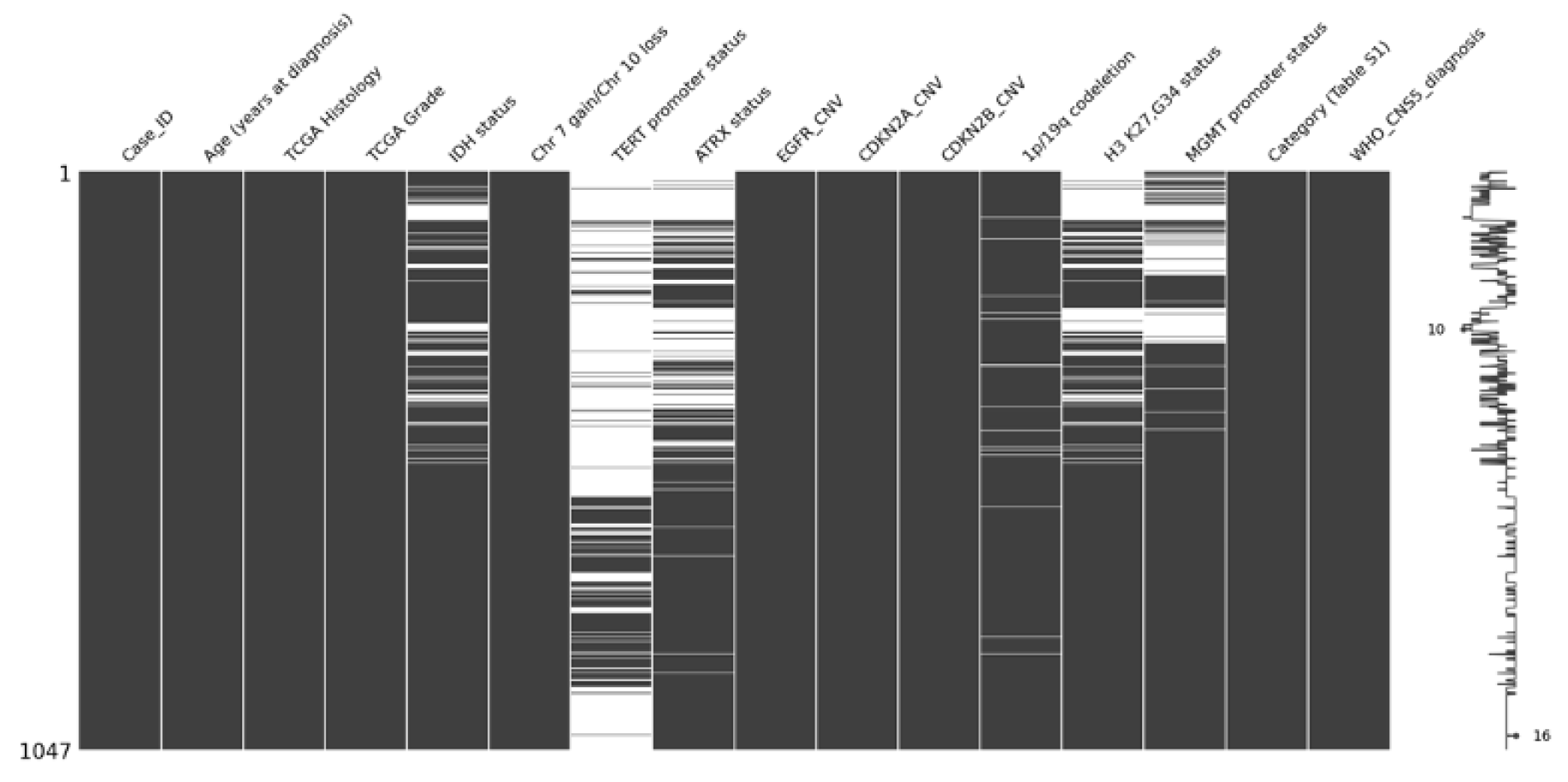

4.5.1. The Cancer Genome Atlas Dataset: Structure of 1 st TCGA Dataset:

4.5.2. The Cancer Genome Atlas Dataset:Structure of 2nd TCGA Dataset:

4.5.3. The Chinese Glioma Genome Atlas Dataset

4.6. Experiments

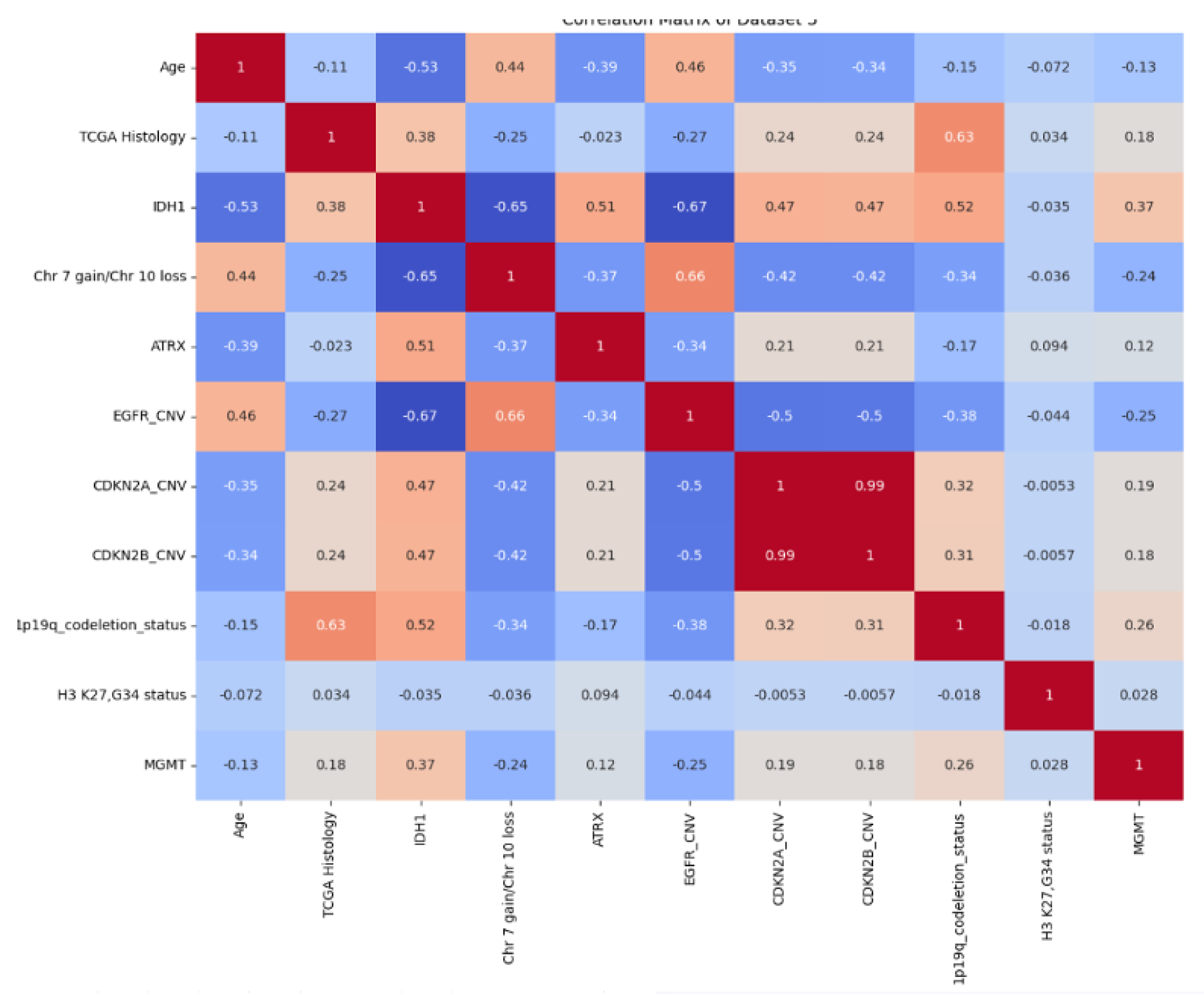

4.6.1. Exploratory Data Analysis

4.6.2. Evaluation Metrics

4.6.3. Results

-

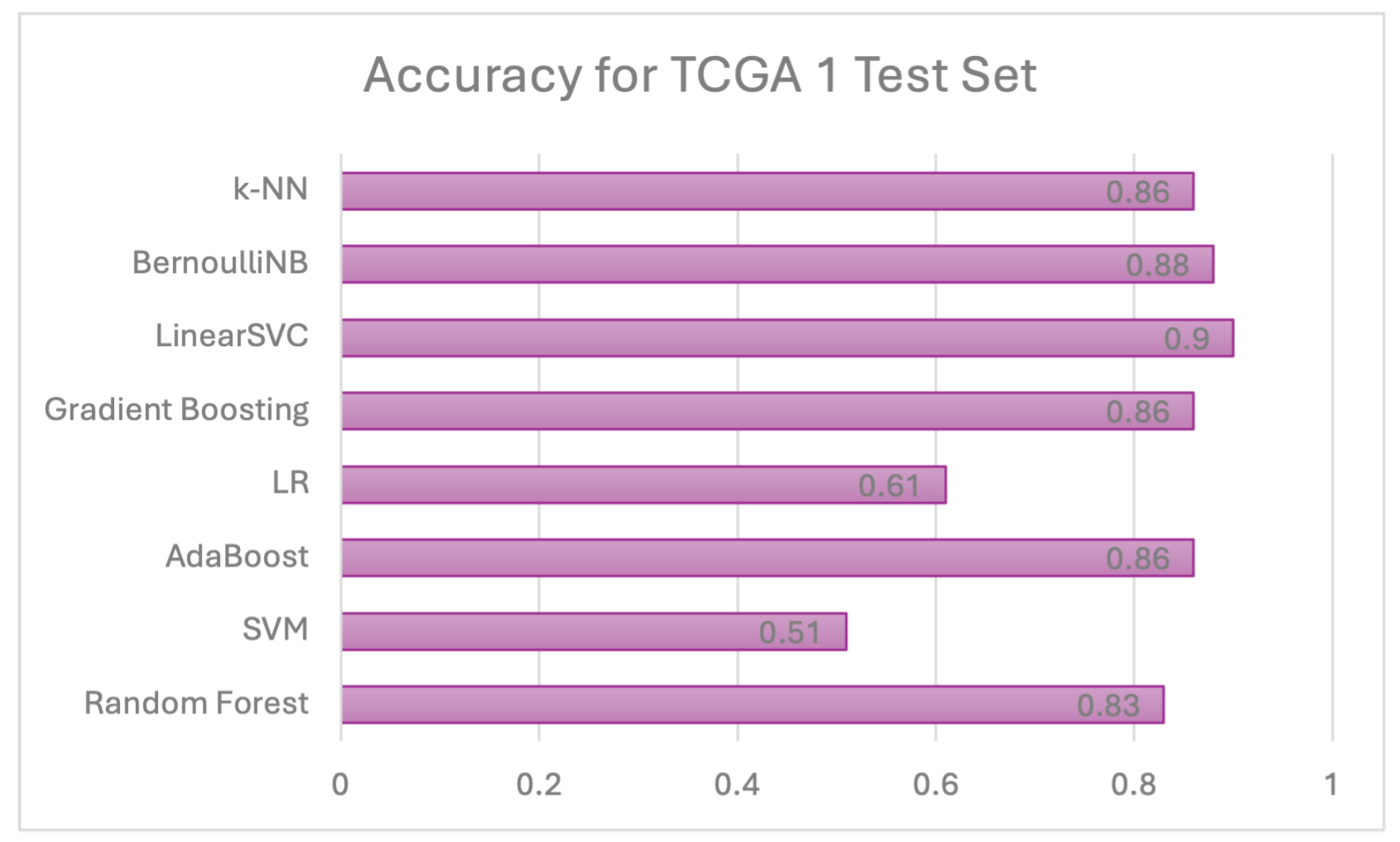

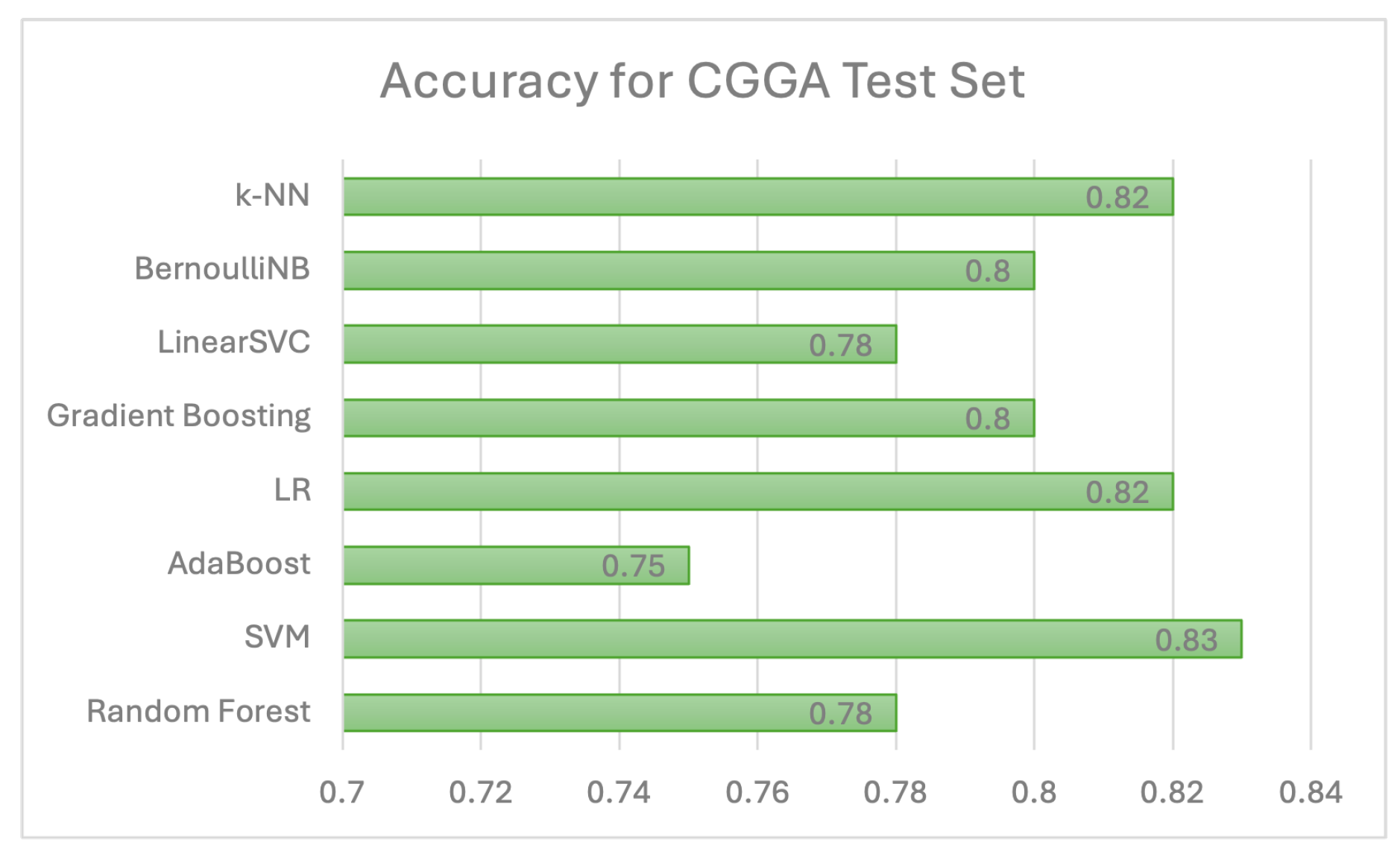

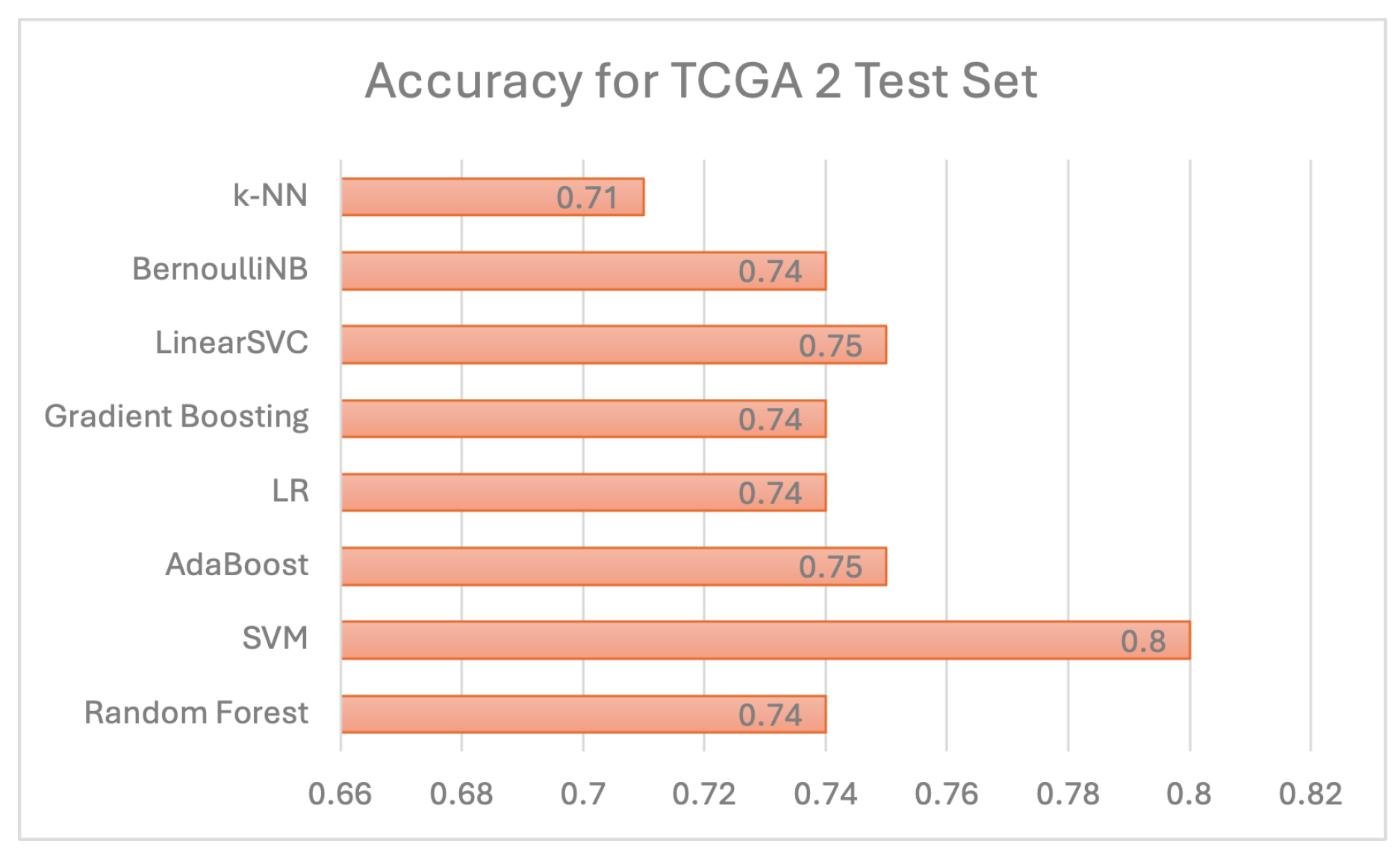

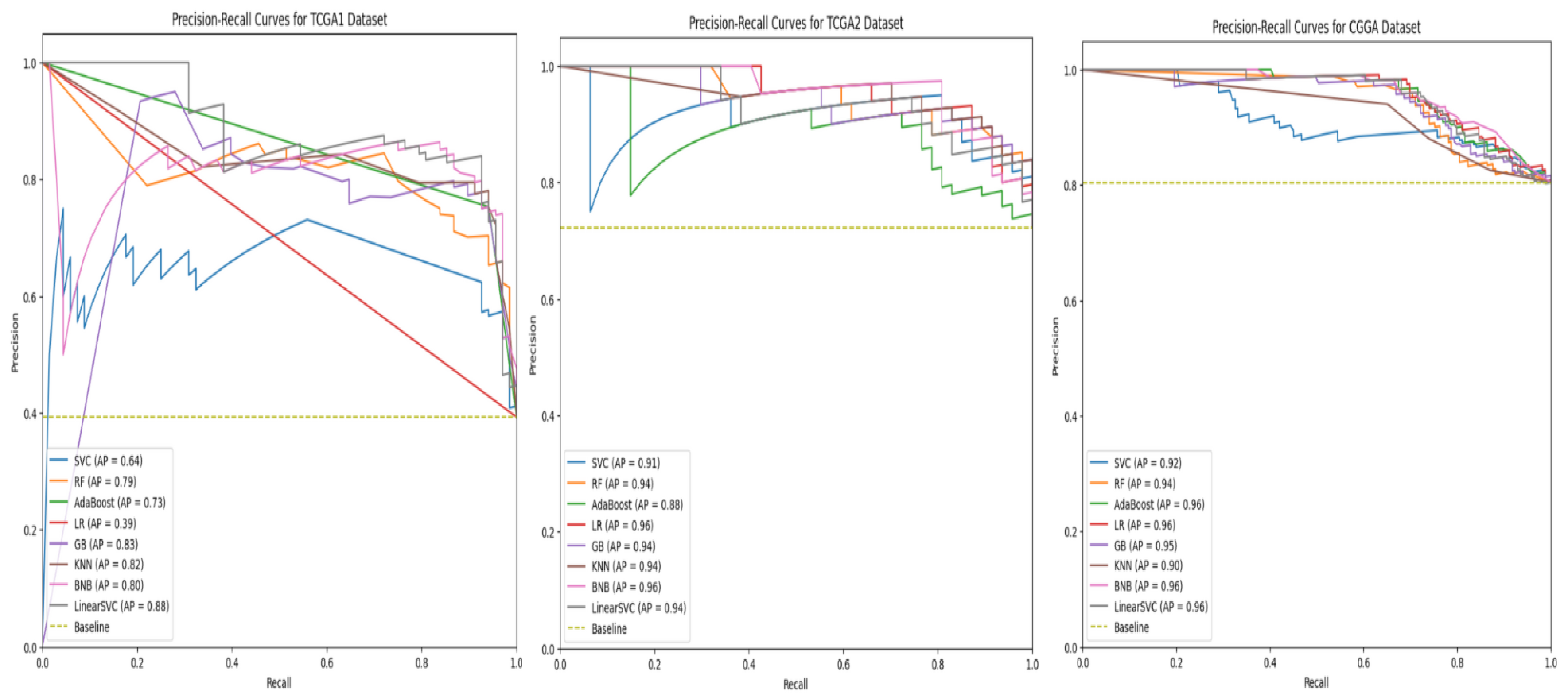

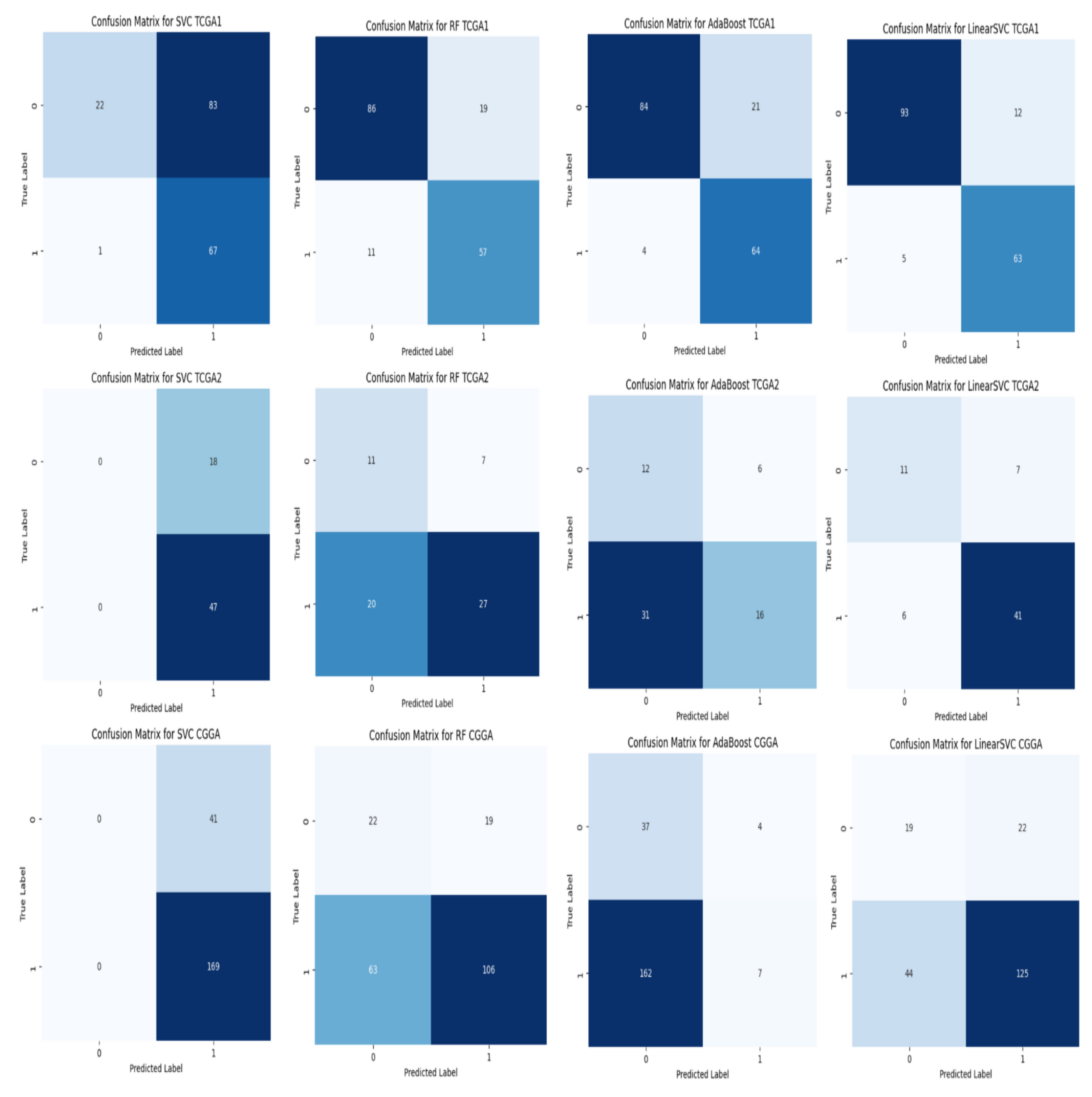

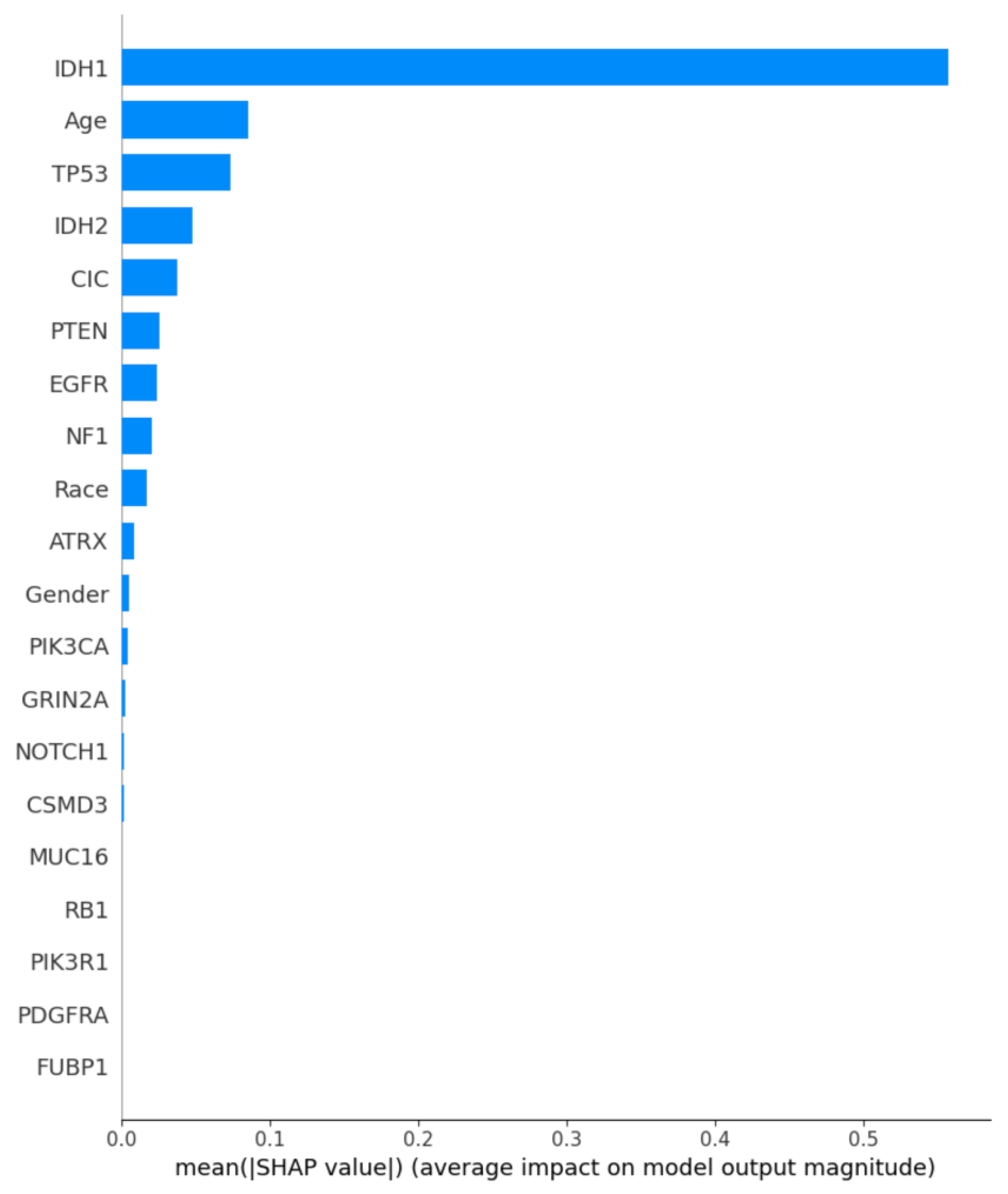

Individual model results All models are evaluated using 5 evaluation metrics. Table 6 below depicts the full evaluation metrics for individual ML algorithms. The results of applying various machine learning algorithms across three datasets (TCGA 1, CGGA, and TCGA 2) reveal distinct performance patterns across multiple evaluation metrics, including precision, recall, F1 score, and ROCAUC, alongside accuracy. For the Random Forest algorithm, TCGA 1 demonstrates strong overall performance with balanced precision (0.75), recall (0.84), and an F1 score of 0.79, while CGGA shows slightly lower accuracy (0.78) but higher precision (0.88), indicating fewer false positives. TCGA 2 has the lowest performance with a lower ROCAUC (0.66), despite good precision (0.88). The Support Vector Machine (SVC) model performs poorly on TCGA 1, with low precision (0.45) but high recall (0.99), resulting in a lower F1 score (0.61). However, the model performs well on CGGA and TCGA 2, with balanced metrics across precision (0.85 and 0.85) and recall (0.94 and 0.92), yielding high F1 scores (0.89 and 0.88). AdaBoost delivers strong results on TCGA 1, with high recall (0.94) and an F1 score of 0.84, while precision is lower at 0.75. On CGGA and TCGA 2, AdaBoost performs moderately well, achieving precision of 0.86 and 0.93, respectively, with balanced F1 scores of around 0.83. Logistic Regression performs poorly on TCGA 1, where all metrics, including precision and recall, are zero. However, on CGGA and TCGA 2, it shows solid performance with precision values of 0.93 and 0.95, though recall is slightly lower (0.81 and 0.71), leading to balanced F1 scores. Gradient Boosting also performs well on TCGA 1, with high recall (0.90), precision (0.78), and a ROCAUC of 0.87. Performance drops on TCGA 2, where precision remains strong (0.88), but ROCAUC drops to 0.66. The Linear SVC model shows the best results on TCGA 1, achieving the highest accuracy (0.90), precision (0.84), and F1 score (0.88), as well as the highest ROCAUC (0.91) across all models. Performance on CGGA and TCGA 2 remains competitive, with a balanced F1 score of 0.85 on CGGA and 0.82 on TCGA 2. Bernoulli Naïve Bayes also performs well on TCGA 1, with high recall (0.93) and precision (0.80), though its performance on CGGA and TCGA 2 is less consistent. Finally, K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) demonstrates stable performance across all datasets, with high recall (0.91) and balanced precision, but accuracy on TCGA 2 is lower at 0.71. Overall, no single model consistently outperforms across all datasets, though Linear SVC and Random Forest achieve strong results on TCGA 1.As shown in Figure 10, linear SVC for TCGA 1 sample has the highest accuracy (90.1%) while SVC with RBF kernel has the lowest accuracy which is 51%. This could suggest that the dataset is partially linearly separatable due to low accuracy score of SVC with RBF kernel. Although, linear SVC obtained a good score of 90%, there is potential for enhancement. This proves that linear SVC is the most accurate model among all supervised models that have been utilised in this study.For CGGA accuracy, all models performed worse than TCGA 1 dataset where SVC with RBF kernel obtained the highest accuracy score of 83% and 75% for the lowest score, as shown in Figure 11. This proves that SVC model was able to capture some non-linear patterns in the date because RBF kernel is effective for non-linear data. It explains why linear SVC has lower accuracy score than SVC with RBF kernel.Regarding accuracy score for TCGA 2 sample, only one model (SVC) achieved 80% and the rest of the models had below than 80%, as shown in Figure 12. The potential reason for this discrepancy is there might be several issues with data pre-processing or simply the sample was not sufficient to train and test.

-

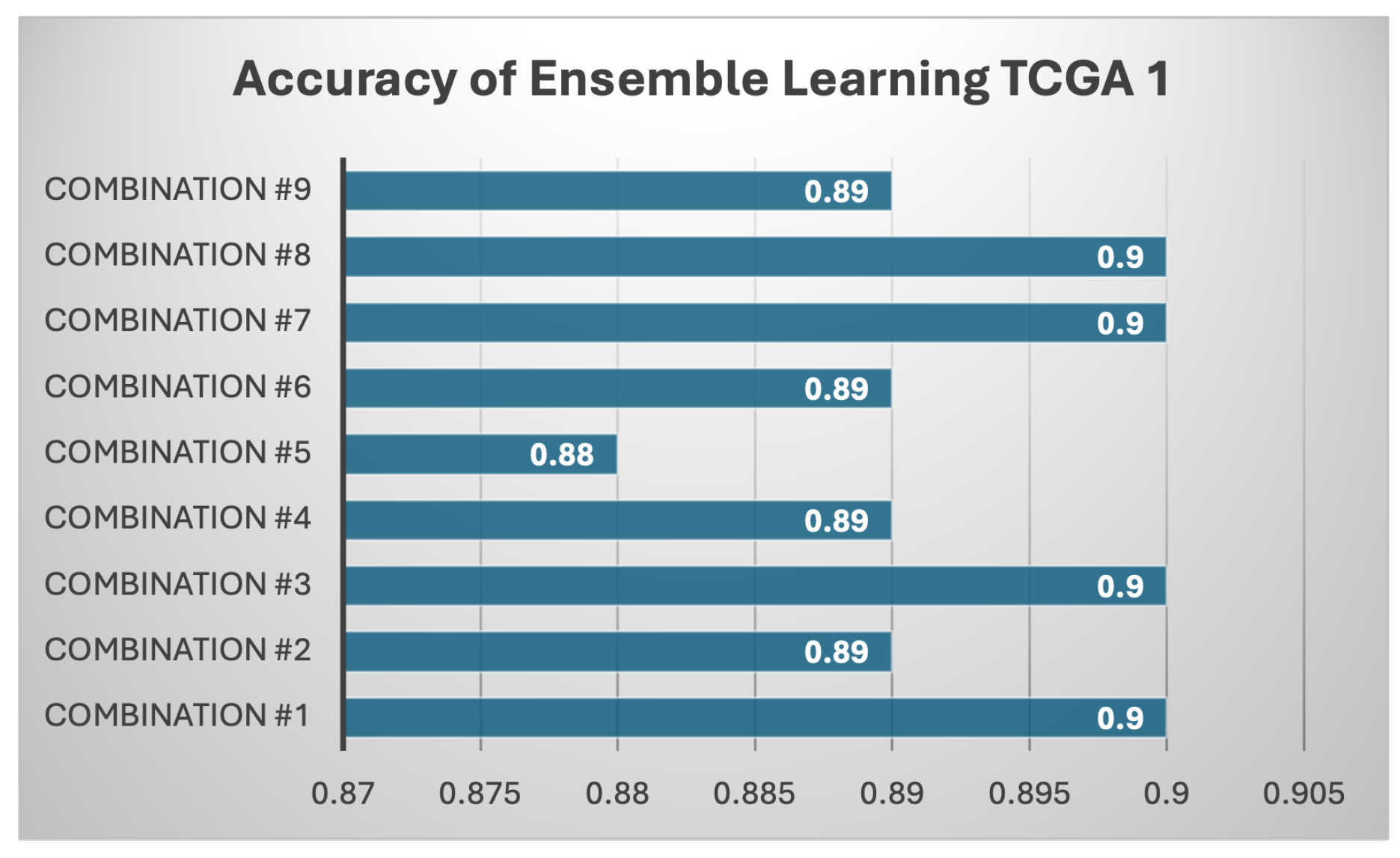

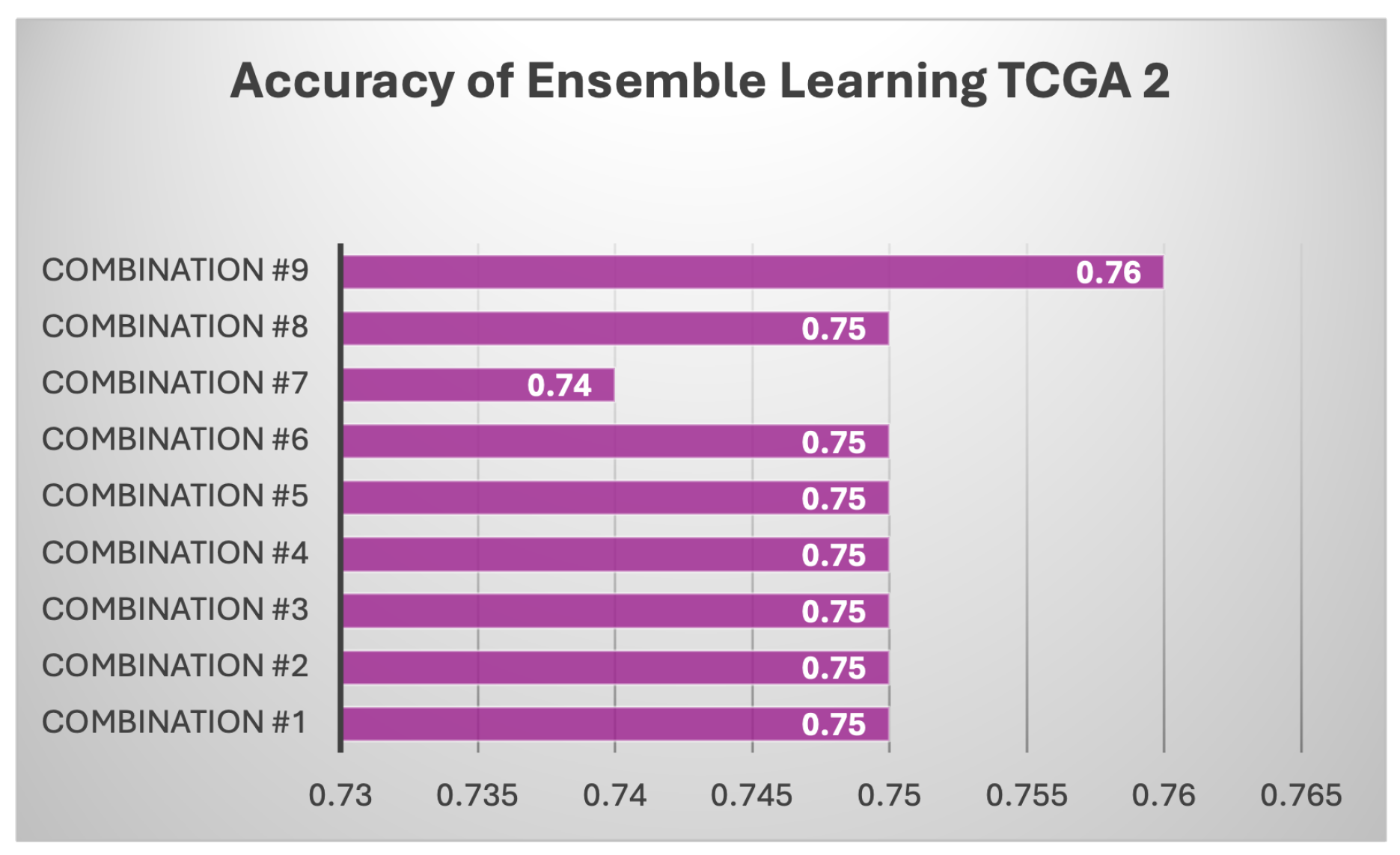

Results of Each Set of Ensemble Learning: Various model combinations were tested across all three datasets (TCGA 1, TCGA 2, and CGGA) to find out if ensemble learning can improve the individual models and gain better performance.As shown in Table 7, different combination of ensemble of models used. The ensemble models, which combine multiple classifiers, consistently outperform individual models across all datasets. For instance, the combination of LinearSVC, AdaBoost, k-NN, BNB, and Random Forest achieves the highest accuracy on TCGA 1 (0.90), with balanced precision (0.84), recall (0.93), F1 score (0.88), and the highest ROC AUC (0.91). Similar strong performance is observed on CGGA and TCGA 2, where precision remains high (0.93 and 0.94, respectively) with a stable F1 score of 0.88 on CGGA and 0.83 on TCGA 2. Another ensemble, using LinearSVC, AdaBoost, BNB, and Random Forest, achieves similar results, particularly on TCGA 1 and CGGA, showing that these combinations leverage the strengths of multiple models to produce more reliable predictions across metrics. Notably, these ensemble approaches surpass individual models in terms of both precision and recall, reflecting a better balance between minimizing false positives and capturing true positives. For example, when k-NN is included in the ensemble with AdaBoost, BNB, and Random Forest, TCGA 1 achieves an accuracy of 0.89 with strong recall (0.90), precision (0.84), and a high F1 score (0.87), further highlighting the consistency and robustness of ensemble techniques. Similarly, CGGA sees significant improvements with the ensemble methods, showing that combining models is more effective than relying on individual classifiers. This is particularly evident in scenarios where no single model excels across all metrics, as seen with the base models. Across all tested configurations, ensemble methods tend to perform better on the TCGA 1 dataset, reaching accuracies as high as 0.90, while CGGA and TCGA 2 maintain competitive results, especially with models that include AdaBoost and Random Forest. The results strongly suggest that ensemble learning provides more stable and generalized predictions, making it a superior approach for handling diverse datasets compared to individual machine learning models.Based on Figure 13, every combination achieved a high accuracy, and this supports that each model combination is a robust model. However, these models are not better than existing models made by past researchers. There are still room more enhancement like obtaining more samples.All models performed reasonably well with CGGA dataset as shown Figure 14 despite it having the smallest sample than the other two datasets. The highest score was achieved by the fourth combination (linear SVC, k-NN, BernoulliNB, and RF) with a score of 85% while the lowest was observed in the first combination with 77% score of accuracy. In contrast, for TCGA 2 dataset as shown in Figure 15, all model combinations had the worst performance among all three datasets, with maximum accuracy score of 76%. Even the worst-performing model combination on the TCGA 1 and CGGA dataset still scored higher than 76%.

4.6.4. Model Error Analysis and Interpretability

4.6.5. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ostrom, Q.T.; Cioffi, G.; Waite, K.; Kruchko, C.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S. CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Other Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2014–2018. Neuro-Oncology 2021, 23, iii1–iii105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munquad, S.; Si, T.; Mallik, S.; Li, A.; Das, A.B. Subtyping and grading of lower-grade gliomas using integrated feature selection and support vector machine. Briefings in Functional Genomics 2022, 21, 408–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raj, K.; Singh, A.; Mandal, A.; Kumar, T.; Roy, A.M. Understanding EEG signals for subject-wise definition of armoni activities. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2301.00948. [Google Scholar]

- Ranjbarzadeh, R.; Jafarzadeh Ghoushchi, S.; Tataei Sarshar, N.; Tirkolaee, E.B.; Ali, S.S.; Kumar, T.; Bendechache, M. ME-CCNN: Multi-encoded images and a cascade convolutional neural network for breast tumor segmentation and recognition. Artificial Intelligence Review 2023, 56, 10099–10136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasci, E.; Zhuge, Y.; Kaur, H.; Camphausen, K.; Krauze, A.V. Hierarchical Voting-Based Feature Selection and Ensemble Learning Model Scheme for Glioma Grading with Clinical and Molecular Characteristics. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 14155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, K.; Kumar, T.; Mileo, A.; Bendechache, M. OxML Challenge 2023: Carcinoma classification using data augmentation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.10544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleem, S.; Kumar, T.; Little, S.; Bendechache, M.; Brennan, R.; McGuinness, K. Random data augmentation based enhancement: a generalized enhancement approach for medical datasets. 24th Irish Machine Vision and Image Processing (IMVIP) Conference, 2022.

- Kumar, T.; Turab, M.; Mileo, A.; Bendechache, M.; Saber, T. AudRandAug: Random Image Augmentations for Audio Classification. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.04762. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.; Ranjbarzadeh, R.; Raj, K.; Kumar, T.; Roy, A. Understanding EEG signals for subject-wise Definition of Armoni Activities. arXiv 2023. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2301.00948. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, T.; Mileo, A.; Brennan, R.; Bendechache, M. Image data augmentation approaches: A comprehensive survey and future directions. arXiv, 2023; arXiv:2301.02830. [Google Scholar]

- Vavekanand, R.; Sam, K.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, T. CardiacNet: A Neural Networks Based Heartbeat Classifications using ECG Signals. Studies in Medical and Health Sciences 2024, 1, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, T.; Park, J.; Ali, M.S.; Uddin, A.S.; Ko, J.H.; Bae, S.H. Binary-classifiers-enabled filters for semi-supervised learning. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 167663–167673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, T.; Turab, M.; Talpur, S.; Brennan, R.; Bendechache, M. FORGED CHARACTER DETECTION DATASETS: PASSPORTS, DRIVING LICENCES AND VISA STICKERS. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence & Applications.

- Khan, W.; Raj, K.; Kumar, T.; Roy, A.M.; Luo, B. Introducing urdu digits dataset with demonstration of an efficient and robust noisy decoder-based pseudo example generator. Symmetry 2022, 14, 1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.F.; Hsu, F.T.; Hsieh, K.L.C.; Kao, Y.C.J.; Cheng, S.J.; Hsu, J.B.K.; Tsai, P.H.; Chen, R.J.; Huang, C.C.; Yen, Y.; Chen, C.Y. Machine Learning–Based Radiomics for Molecular Subtyping of Gliomas. Clinical Cancer Research 2018, 24, 4429–4436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noviandy, T.R.; Alfanshury, M.H.; Abidin, T.F.; Riza, H. Enhancing Glioma Grading Performance: A Comparative Study on Feature Selection Techniques and Ensemble Machine Learning. 2023 International Conference on Computer, Control, Informatics and its Applications (IC3INA). IEEE, 2023, pp. 406–411. [CrossRef]

- Oberoi, V.; Negi, B.S.; Chandan, D.; Verma, P.; Kulkarni, V. Grade and Subtype Classification for Glioma Tumors using Clinical and Molecular Mutations. 2023 International Conference on Modeling, Simulation & Intelligent Computing (MoSICom). IEEE, 2023, pp. 468–473. [CrossRef]

- Turab, M.; Kumar, T.; Bendechache, M.; Saber, T. Investigating multi-feature selection and ensembling for audio classification. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence & Applications 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.; Raj, K.; Kumar, T.; Verma, S.; Roy, A.M. Deep learning-based cost-effective and responsive robot for autism treatment. Drones 2023, 7, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, T.; Mileo, A.; Brennan, R.; Bendechache, M. RSMDA: Random Slices Mixing Data Augmentation. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Wang, D.; Mok, V.C.; Shi, L. Comparison of Feature Selection Methods and Machine Learning Classifiers for Radiomics Analysis in Glioma Grading. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 102010–102020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutta, S.; Acharya, J.; Shiroishi, M.; Hwang, D.; Nayak, K. Improved Glioma Grading Using Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. American Journal of Neuroradiology 2021, 42, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, J.; Choudhary, C.; Gobind, H.; Abrol, V. ; Anurag. Gliomas Disease Prediction: An Optimized Ensemble Machine Learning-Based Approach. 2023 3rd International Conference on Technological Advancements in Computational Sciences (ICTACS). IEEE, 2023, pp. 1307–1311. [CrossRef]

- Sriramoju, S.P.; Srivastava, S. Enhanced Glioma Disease Prediction Through Ensemble-Optimized Machine Learning. 2024 International Conference on Communication, Computer Sciences and Engineering (IC3SE). IEEE, 2024, pp. 460–465. [CrossRef]

- Ullah, M.S.; Khan, M.A.; Albarakati, H.M.; Damaševičius, R.; Alsenan, S. Multimodal brain tumor segmentation and classification from MRI scans based on optimized DeepLabV3+ and interpreted networks information fusion empowered with explainable AI. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2024, 182, 109183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapôso, C.; Vitorino-Araujo, J.L.; Barreto, N. Molecular Markers of Gliomas to Predict Treatment and Prognosis: Current State and Future Directions; Exon Publications, 2021; pp. 171–186. [CrossRef]

- Tehsin, S.; Nasir, I.M.; Damaševičius, R.; Maskeliūnas, R. DaSAM: Disease and Spatial Attention Module-Based Explainable Model for Brain Tumor Detection. Big Data and Cognitive Computing 2024, 8, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourou, K.; Exarchos, T.P.; Exarchos, K.P.; Karamouzis, M.V.; Fotiadis, D.I. Machine learning applications in cancer prognosis and prediction. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal 2015, 13, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanan, R.; Sujatha, P. A State of Art Techniques on Machine Learning Algorithms: A Perspective of Supervised Learning Approaches in Data Classification. 2018 Second International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Control Systems (ICICCS). IEEE, 2018, pp. 945–949. [CrossRef]

- Dutta, P.; Paul, S.; Kumar, A. , Comparative analysis of various supervised machine learning techniques for diagnosis of COVID-19; Elsevier, 2021; pp. 521–540. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ni, M.; Zhang, C.; Liang, S.; Fang, S.; Li, R.; Tan, Z. Research and Application of AdaBoost Algorithm Based on SVM. 2019 IEEE 8th Joint International Information Technology and Artificial Intelligence Conference (ITAIC). IEEE, 2019, pp. 662–666. [CrossRef]

- Qadir, A. Tuning parameters of SVM: Kernel, Regularization, Gamma and Margin., 2020.

- Strzelecka, A.; Kurdyś-Kujawska, A.; Zawadzka, D. Application of logistic regression models to assess household financial decisions regarding debt. Procedia Computer Science 2020, 176, 3418–3427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasteski, V. An overview of the supervised machine learning methods. HORIZONS.B 2017, 4, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, N.; Akhir, E.A.P.; Aziz, I.A.; Jaafar, J.; Hasan, M.H.; Abas, A.N.C. A Study on Gradient Boosting Algorithms for Development of AI Monitoring and Prediction Systems. 2020 International Conference on Computational Intelligence (ICCI). IEEE, 2020, pp. 11–16. [CrossRef]

| Research Paper | Author(s) Name, Year and Reference No. | Best Model |

|---|---|---|

| Machine Learning Based Radiomics for Molecular Subtyping of Gliomas | Lu et al. (2018), [15] | Cubic SVM |

| Comparison of Feature Selection Methods and Machine Learning Classifiers for Radiomics Analysis in Glioma Grading | Sun et al. (2019), [21] | Multilayer Perceptron |

| Improved Glioma Grading Using Deep Convolutional Neural Networks | Gutta et al. (2021), [22] | Convolutional Neural Networks |

| Hierarchical Voting-Based Feature Selection and Ensemble Learning Model Scheme for Glioma Grading with Clinical and Molecular Characteristics | Tasci et al. (2022), [5] | Ensemble Learning Model–Soft Voting |

| Enhancing Glioma Grading Performance: A Comparative Study on Feature Selection Techniques and Ensemble Machine Learning | Noviandy et al. (2023), [16] | Ensemble Learning Model |

| Grade and Subtype Classification for Glioma Tumors using Clinical and Molecular Mutations | Oberoi et al. (2023), [17] | Logistic Regression |

| Gliomas Disease Prediction: An Optimized Ensemble Machine Learning-Based Approach | Thakur et al. (2023), [23] | KStar and SMOreg – Ensemble Learning Method |

| Enhanced Glioma Disease Prediction Through Ensemble-Optimized Machine Learning | Sriramoju and Srivastava (2024), [24] | Decision Tree and Random Forest – Ensemble Learning Method |

| Attributes | Description |

|---|---|

| Grade | Glioma grade of the corresponding patient |

| Project | The name of the genome atlas database |

| Case ID | Unique ID that corresponds to each patient |

| Gender | Gender of patient |

| Age at diagnosis | Age of patient |

| Primary Diagnosis | Types of glioma present |

| Race | Race of patient |

| IDH1 | Status of IDH1 mutation |

| TP53 | Status of TP53 mutation |

| ATRX | Status of ATRX mutation |

| PTEN | Status of PTEN mutation |

| EGFR | Status of EGFR mutation |

| CIC | Status of CIC mutation |

| MUC16 | Status of MUC16 mutation |

| PIK3CA | Status of PIK3CA mutation |

| NF1 | Status of NF1 mutation |

| PIK3R1 | Status of PIK3R1 mutation |

| FUBP1 | Status of FUBP1 mutation |

| RB1 | Status of RB1 mutation |

| NOTCH1 | Status of NOTCH1 mutation |

| BCOR | Status of BCOR mutation |

| CSMD3 | Status of CSMD3 mutation |

| SMARCA4 | Status of SMARCA4 mutation |

| GRIN2A | Status of GRIN2A mutation |

| IDH2 | Status of IDH2 mutation |

| FAT4 | Status of FAT4 mutation |

| PDGFRA | Status of PDGFRA mutation |

| Attributes | Description |

|---|---|

| Case ID | Unique ID that corresponds to each patient |

| Age (years at diagnosis) | Age of patients |

| TCGA Histology | Types of glioma present |

| TCGA Grade | Glioma grade of the corresponding patient |

| IDH1 Status | Status of IDH1 mutation |

| Chr 7 gain/Chr 10 loss | Status of chromosome 7 gain and 10 loss combination |

| TERT promoter status | Status of TERT mutation |

| ATRX status | Status of ATRX mutation |

| EGFR CNV | Number of CNVs in the EGFR gene |

| CDKN2A CNV | Number of CNVs in the CDKN2A gene |

| CDKN2B CNV | Number of CNVs in the CDKN2B gene |

| 1p/19q codeletion | Status of 1p/19q chromosomal codeletion |

| H3 K27, G34 status | Status of H3 K27 and H3 G34 mutations |

| MGMT promoter status | Status of MGMT mutation |

| Category (Table S1) | Description of the glioma combination |

| WHO CNS5 diagnosis | Glioma grade by the World Health Organization |

| Attributes | Description |

|---|---|

| CGGA ID | Unique ID that corresponds to each patient |

| PRS type | Primary or recurrent glioma |

| Histology | Types of glioma present |

| Grade | Glioma grade by WHO |

| Gender | Gender of patient |

| Age | Age of patient |

| OS | Overall survival of patient |

| Censor (alive=0; dead=1) | Dead or alive status |

| Radio status (treated=1; untreated=0) | Radiation therapy treatment status |

| Chemo status (TMZ treated=1; untreated=0) | Chemotherapy treatment status |

| IDH mutation status | IDH1 and IDH2 mutation status |

| 1p19q codeletion status | Status of 1p/19q chromosomal codeletion |

| MGMTp methylation status | MGMT methylation status |

| Dataset | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1 | ROCAUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest | |||||

| TCGA 1 | 0.83 ± 0.02 | 0.75 ± 0.01 | 0.84 ± 0.02 | 0.79 ± 0.01 | 0.83 ± 0.01 |

| CGGA | 0.78 ± 0.01 | 0.88 ± 0.01 | 0.81 ± 0.01 | 0.84 ± 0.01 | 0.77 ± 0.01 |

| TCGA 2 | 0.74 ± 0.02 | 0.88 ± 0.01 | 0.79 ± 0.01 | 0.83 ± 0.01 | 0.66 ± 0.02 |

| Support Vector Machine | |||||

| TCGA 1 | 0.51 ± 0.02 | 0.45 ± 0.01 | 0.99 ± 0.01 | 0.61 ± 0.01 | 0.60 ± 0.01 |

| CGGA | 0.83 ± 0.01 | 0.85 ± 0.01 | 0.94 ± 0.01 | 0.89 ± 0.01 | 0.75 ± 0.01 |

| TCGA 2 | 0.80 ± 0.01 | 0.85 ± 0.01 | 0.92 ± 0.01 | 0.88 ± 0.01 | 0.62 ± 0.01 |

| AdaBoost | |||||

| TCGA 1 | 0.86 ± 0.01 | 0.75 ± 0.01 | 0.94 ± 0.01 | 0.84 ± 0.01 | 0.87 ± 0.01 |

| CGGA | 0.75 ± 0.01 | 0.86 ± 0.01 | 0.79 ± 0.01 | 0.82 ± 0.01 | 0.73 ± 0.01 |

| TCGA 2 | 0.75 ± 0.02 | 0.93 ± 0.01 | 0.75 ± 0.01 | 0.83 ± 0.01 | 0.75 ± 0.01 |

| Logistic Regression | |||||

| TCGA 1 | 0.61 ± 0.02 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.50 ± 0.01 |

| CGGA | 0.82 ± 0.01 | 0.93 ± 0.01 | 0.81 ± 0.01 | 0.86 ± 0.01 | 0.82 ± 0.01 |

| TCGA 2 | 0.74 ± 0.02 | 0.95 ± 0.01 | 0.71 ± 0.01 | 0.81 ± 0.01 | 0.78 ± 0.01 |

| Gradient Boosting | |||||

| TCGA 1 | 0.86 ± 0.01 | 0.78 ± 0.01 | 0.90 ± 0.01 | 0.84 ± 0.01 | 0.87 ± 0.01 |

| CGGA | 0.80 ± 0.01 | 0.93 ± 0.01 | 0.79 ± 0.01 | 0.85 ± 0.01 | 0.81 ± 0.01 |

| TCGA 2 | 0.74 ± 0.02 | 0.88 ± 0.01 | 0.79 ± 0.01 | 0.82 ± 0.01 | 0.66 ± 0.02 |

| Linear SVC | |||||

| TCGA 1 | 0.90 ± 0.01 | 0.84 ± 0.01 | 0.93 ± 0.01 | 0.88 ± 0.01 | 0.91 ± 0.01 |

| CGGA | 0.78 ± 0.01 | 0.87 ± 0.01 | 0.83 ± 0.01 | 0.85 ± 0.01 | 0.75 ± 0.01 |

| TCGA 2 | 0.75 ± 0.02 | 0.96 ± 0.01 | 0.72 ± 0.01 | 0.82 ± 0.01 | 0.80 ± 0.01 |

| Bernoulli Naïve Bayes | |||||

| TCGA 1 | 0.88 ± 0.01 | 0.80 ± 0.01 | 0.93 ± 0.01 | 0.96 ± 0.01 | 0.89 ± 0.01 |

| CGGA | 0.80 ± 0.01 | 0.89 ± 0.01 | 0.83 ± 0.01 | 0.86 ± 0.01 | 0.78 ± 0.01 |

| TCGA 2 | 0.74 ± 0.02 | 0.95 ± 0.01 | 0.72 ± 0.01 | 0.82 ± 0.01 | 0.78 ± 0.01 |

| K-Nearest Neighbors | |||||

| TCGA 1 | 0.86 ± 0.01 | 0.78 ± 0.01 | 0.91 ± 0.01 | 0.84 ± 0.01 | 0.87 ± 0.01 |

| CGGA | 0.82 ± 0.01 | 0.93 ± 0.01 | 0.81 ± 0.01 | 0.86 ± 0.01 | 0.82 ± 0.01 |

| TCGA 2 | 0.71 ± 0.02 | 0.88 ± 0.01 | 0.74 ± 0.01 | 0.80 ± 0.01 | 0.66 ± 0.02 |

| Dataset | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1 | ROC AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LinearSVC + AdaBoost + BNB + k-NN + RF | |||||

| TCGA 1 | 0.90 ± 0.01 | 0.84 ± 0.01 | 0.93 ± 0.01 | 0.88 ± 0.01 | 0.91 ± 0.01 |

| CGGA | 0.83 ± 0.01 | 0.93 ± 0.01 | 0.83 ± 0.01 | 0.88 ± 0.01 | 0.83 ± 0.01 |

| TCGA 2 | 0.75 ± 0.01 | 0.94 ± 0.01 | 0.73 ± 0.01 | 0.83 ± 0.01 | 0.77 ± 0.01 |

| LinearSVC + AdaBoost + BNB + RF | |||||

| TCGA 1 | 0.89 ± 0.01 | 0.84 ± 0.01 | 0.90 ± 0.01 | 0.87 ± 0.01 | 0.89 ± 0.01 |

| CGGA | 0.82 ± 0.01 | 0.93 ± 0.01 | 0.81 ± 0.01 | 0.86 ± 0.01 | 0.82 ± 0.01 |

| TCGA 2 | 0.75 ± 0.01 | 0.95 ± 0.01 | 0.73 ± 0.01 | 0.82 ± 0.01 | 0.78 ± 0.01 |

| LinearSVC + AdaBoost + BNB + k-NN | |||||

| TCGA 1 | 0.90 ± 0.01 | 0.84 ± 0.01 | 0.93 ± 0.01 | 0.88 ± 0.01 | 0.91 ± 0.01 |

| CGGA | 0.83 ± 0.01 | 0.95 ± 0.01 | 0.81 ± 0.01 | 0.87 ± 0.01 | 0.85 ± 0.01 |

| TCGA 2 | 0.75 ± 0.01 | 0.95 ± 0.01 | 0.72 ± 0.01 | 0.82 ± 0.01 | 0.78 ± 0.01 |

| LinearSVC + k-NN + BNB + RF | |||||

| TCGA 1 | 0.89 ± 0.01 | 0.84 ± 0.01 | 0.90 ± 0.01 | 0.87 ± 0.01 | 0.89 ± 0.01 |

| CGGA | 0.85 ± 0.01 | 0.95 ± 0.01 | 0.83 ± 0.01 | 0.89 ± 0.01 | 0.86 ± 0.01 |

| TCGA 2 | 0.75 ± 0.01 | 0.97 ± 0.01 | 0.71 ± 0.01 | 0.82 ± 0.01 | 0.81 ± 0.01 |

| AdaBoost + k-NN + BNB + RF | |||||

| TCGA 1 | 0.88 ± 0.01 | 0.83 ± 0.01 | 0.88 ± 0.01 | 0.86 ± 0.01 | 0.88 ± 0.01 |

| CGGA | 0.80 ± 0.01 | 0.93 ± 0.01 | 0.79 ± 0.01 | 0.85 ± 0.01 | 0.81 ± 0.01 |

| TCGA 2 | 0.75 ± 0.01 | 0.95 ± 0.01 | 0.73 ± 0.01 | 0.83 ± 0.01 | 0.79 ± 0.01 |

| AdaBoost + k-NN + LinearSVC + RF | |||||

| TCGA 1 | 0.89 ± 0.01 | 0.84 ± 0.01 | 0.90 ± 0.01 | 0.87 ± 0.01 | 0.89 ± 0.01 |

| CGGA | 0.83 ± 0.01 | 0.95 ± 0.01 | 0.79 ± 0.01 | 0.86 ± 0.01 | 0.84 ± 0.01 |

| TCGA 2 | 0.75 ± 0.01 | 0.96 ± 0.01 | 0.72 ± 0.01 | 0.82 ± 0.01 | 0.80 ± 0.01 |

| LinearSVC + AdaBoost + k-NN | |||||

| TCGA 1 | 0.90 ± 0.01 | 0.84 ± 0.01 | 0.93 ± 0.01 | 0.88 ± 0.01 | 0.91 ± 0.01 |

| CGGA | 0.80 ± 0.01 | 0.90 ± 0.01 | 0.81 ± 0.01 | 0.85 ± 0.01 | 0.79 ± 0.01 |

| TCGA 2 | 0.74 ± 0.01 | 0.94 ± 0.01 | 0.73 ± 0.01 | 0.82 ± 0.01 | 0.77 ± 0.01 |

| LinearSVC + AdaBoost + BNB | |||||

| TCGA 1 | 0.90 ± 0.01 | 0.84 ± 0.01 | 0.93 ± 0.01 | 0.88 ± 0.01 | 0.91 ± 0.01 |

| CGGA | 0.80 ± 0.01 | 0.90 ± 0.01 | 0.83 ± 0.01 | 0.86 ± 0.01 | 0.78 ± 0.01 |

| TCGA 2 | 0.75 ± 0.01 | 0.95 ± 0.01 | 0.73 ± 0.01 | 0.83 ± 0.01 | 0.78 ± 0.01 |

| LinearSVC + k-NN + BNB | |||||

| TCGA 1 | 0.90 ± 0.01 | 0.84 ± 0.01 | 0.93 ± 0.01 | 0.88 ± 0.01 | 0.91 ± 0.01 |

| CGGA | 0.81 ± 0.01 | 0.90 ± 0.01 | 0.82 ± 0.01 | 0.86 ± 0.01 | 0.78 ± 0.01 |

| TCGA 2 | 0.75 ± 0.01 | 0.95 ± 0.01 | 0.73 ± 0.01 | 0.83 ± 0.01 | 0.78 ± 0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).