1. Introduction

Ikaite (CaCO

3·6H

2O - hexahydrate of calcium carbonate) is a unique mineral that forms at low temperatures during early diagenesis. When the temperature exceeds 6-7 °C, ikaite loses water, resulting in the formation of calcite [

1,

2,

3]. The transformation to calcite often occurs through an intermediate vaterite phase [

3,

4,

5]. The calcite form often preserves the shape of ikaite crystals, forming a pseudomorph known as glendonite [

6,

7]. This mineral is also known by several other names, including gennoishi, thinolite, jarrovite, White Sea hornlets etc [

6,

8]. Pseudomorphs of ikaites are commonly used as indicator of past climate cooling, as they can only be found in areas with cold ocean floors [

2,

8,

9,

10].

On the other hand, the confirmed presence of methane-derived carbon in the crystal lattice of certain modern ikaites from bottom sediments [

4,

11,

12,

13], provides a basis for comparing glendonites enriched in light

12C isotope with ancient methane seepage sites [

14,

15]. In this context, collecting data on the processes that lead to ikaite formation in modern bottom sediments from various environments is essential for understanding both the potential use of these sediments in reconstructing past climate changes and the characteristics of the carbon cycle, especially in Earth’s polar regions.

The bottom sediments of the Kara Sea are one of the most favorable environments for the formation of ikaite, as confirmed by numerous findings of this mineral [

12,

16,

17]. The formation of ordinary anhydrous authigenic carbonates on the Arctic shelf is inhibited, mainly due to the low and sometimes negative temperatures of the bottom water. Single occurrences of such carbonate minerals in the Kara Sea are represented by calcite [

18,

19].

2. Materials and Methods

Offshore research in the southeastern part of the Kara Sea was conducted on board the R/V Fridtjof Nansen (PINRO) in August 2015. During the coring operation at three different sites (FN-76T, FN-169T, and FN-170T), we discovered ikaite concretions at various depths in the sediment (

Figure 1,

Table 1). These concretions appeared in the form of rounded "needle-shaped" nodules or as intergrowths of individual crystals. In our work we also used the results of ikaites studies in the Kara Sea, previously published by other researchers [

12,

20] (

Figure 1,

Table 1).

The δ13С and δ18О isotopic composition of ikaite, as well as the δ13С value of organic carbon (Corg) in sediments, were determined using a Finnigan Delta Plus XP mass spectrometer. Limestone NBS-19 was used as a standard. The δ13С values are reported on the VPDB scale, while the δ18О values are reported in the VPDB scale for carbonates and the VSMOW scale for water.

X-ray diffraction analysis of ikaite was carried out under vacuum conditions using a Rigaku “Ultima IV” diffractometer. The anode material is a standard CuKα X-ray tube. The nominal operating mode of the X-ray source is 40 kV / 35 mA. Scan range 2θ angles from 5° to 85°. Reflected X-ray detector - high-speed energy dispersive detector D-TexUltra. Silicone was added as a standard for peak correction. XRD measurements of ikaite were conducted at intervals of 5 minutes, 20 minutes, 3 days and 30 days, under controlled conditions at 25 °C and a 1 atm pressure (

Figure 2). For the sample held for 5 minutes under standard conditions, the rate of XRD measurement was 20° 2 θ per minute. Subsequent measurements were performed at a slower rate of 5° 2 θ per minute.

Thermal XRD-analysis of ikaites was conducted in the temperature range from -30° to +50 °C under vacuum conditions using a research complex based on the Rigaku “UltimaIV” diffractometer equipped with a medium- and low-temperature Rigaku “R-300” attachment. A resistive heater external to the sample was used. The temperature gradient throughout the sample did not exceed ±2.5 °C. The measurement speed was 2°/min, the heating rate was 5°/min. Before each measurement, the sample was kept for an hour at a certain temperature.

The concentrations of rare earth elements in the ikaite and sediment samples were determined using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS), following acid digestion. Measurements were conducted using an ELEMENT 2 mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific GmbH) at the Geological Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

3. Results

The sediment cores analyzed (FN-76T, FN-170T and FN-196T) were collected from the southern part of the Kara Sea, under the influence of the Yenisei River (

Figure 1). The water depth at the sampling sites varied from 36 to 50 m. The host sediments of all sites were represented by Upper Pleistocene-Holocene sediments, usually of fine-grained composition. These sediments often had a noticeable odor of hydrogen sulfide. Mollusk shells, polychaete tubes, small spottiness and lenses of hydrotroilite were observed in the cores. These features of the sediment are a consequence of reduced conditions.

The ikaite crystals were found at different depths beneath the sea floor and had distinct shapes (

Figure 1). At site FN-76T, druses of honey-yellow crystals with diameter of 4-5 cm were observed at a depth of 70 cm below the see floor. Spherical intergrowths of crystals in the sediment range of 65-70 cmbsf were found at the site FN-170T. At the site FN-196T, individual ikaite crystals were sampled at the sediment depth of 90 cmbsf. In all cores, ikaite was found in more compacted clayey sediments than the overlying ones.

The results of XRD measurements indicate that calcite formed 20 minutes after keeping the sample under standard conditions contained a small amount of magnesium in the crystal lattice; its formula can be written as (Mg

0.03, Ca

0.97)CO

3. The XRD analysis revealed that traces of the ikaite phase existed in the sample for at least three days. XRD-measurements taken after 30 days showed the disappearance of reflexes corresponding to ikaite - a complete transformation of ikaite into calcite occurred. The presence of intermediate phases such as vaterite was not detected. It was established earlier that when the temperature differential between formation and breakdown is larger (e.g. > 15 °C), vaterite was observed to form as an intermediate stage, whereas when this differential was < 10 °C, only calcite formed [

3,

23].

The results of thermal XRD-analysis of the ikaite-calcite transition in the temperature range from -30 °C to +50 °C are shown in

Figure 3.

The X-ray diffraction pattern (

Figure 3) shows that reflections shift towards larger angles when the sample is heated, indicating that water is being removed from the interlayer space. The peaks of ikaite gradually become less pronounced and eventually disappear completely at a certain temperature. At the same time, an increase in the areas of calcite reflections is observed.

Figure 3.

Results of thermal XRD-analysis of ikaite crystal from site FN-76T.

Figure 3.

Results of thermal XRD-analysis of ikaite crystal from site FN-76T.

The rare earth elements (REE) concentrations in ikaite and sediment from site FN-169T (

Table 2) were normalized to the Post-Archean Australian Shale (PAAS; [

24]), with the PAAS-normalized REE data presented in

Figure 4. The ikaites are characterized by a luck of Ce anomaly (Ce/Ce* = 0.94 and 1.03), a MREE (Sm-Dy)-bulge, positive Eu anomaly (Eu/Eu* = 1.1 to 1.13), and superchondritic Y/Ho ratios (29 and 28) (

Figure 4). The sediment sample has Ce/Ce* and Eu/Eu* values of 0.92 and 1.06, respectively, along with a pronounced MREE-bulge and a Y/Ho ratio of 26.4. The REE content in the ikaite sampled from a depth of 70 cmbsf was significantly higher than in the ikaite from a level of 65 cmbsf (

Table 2), suggesting a higher degree of contamination in the former sample with the sedimentary material.

In addition to the ikaite samples collected during our expedition on the R/V Fridtjof Nansen, this mineral has also been found in the Kara Sea several times by other researchers [

12,

16,

17,

20,

21,

22,

25]. The first documented discovery of ikaite in the sediments of the Kara Sea was made in 1997 at site 97-24 during a scientific cruise on the R/V "Akademik Boris Petrov" [

21]. Small bladed and needle-shaped crystals, less than 2 centimeters in size, as well as twinned crystal intergrowths ranging from 1 to 5 centimeters, were found in the dark gray clay between depths of 5 and 25 cmbsf. Their δ

13C values ranged from -30 to -28.8‰ VPDB (

Table 1) [

20,

21].

Detailed studies of ikaites collected at two sites during the cruise of the R/V "Akademik Boris Petrov" in 2001 are presented in the paper by [

12]. In the sediments from site 01-26, at a sub-bottom depth of 226-230 centimeters, a spherical cluster of small (less than 1 centimeter) bladed ikaite crystal intergrowths were sampled. The cluster was approximately 5 centimeters in diameter. We found a similar sample, although smaller in size, in the sediment of site FN-76T, which is located north of site 01-26 (

Figure 1). Not only the morphology, but also the carbon isotope composition of the ikaite samples is similar: - 20.5‰ (in site FN-76T) and -24.0‰ (in site 01-26).

In the sediments from site 01-55 ikaite samples were found at a depth of 135 cmbsf in the form of single crystals and as intergrowths of 2-3 crystals up to 6.5 cm long [

12]. Below, at a level of 165 cmbsf, a large pyramid-shaped crystal with size of 4.5 × 12 cm was discovered, along with three smaller crystals. The δ

13С values of these ikaite samples vary from -42.3 to -40.1‰ VPDB (

Figure 1,

Table 1). The shape and size of ikaite crystals are likely to be directly influenced by the rates of crystallization. These rates are determined by factors such as temperature, the presence of anhydrous carbonate inhibitors, and the level of supersaturation of pore water with calcium and bicarbonate ions.

Numerous pyramidal ikaite crystals, 2-4 cm long, were found in the sediments at site 03-07, between depth of 175 cmbsf and the base of the section at 320 cmbsf [

20]. The δ

13C values of the ikaites at this site range from -57.3‰ (same as in our site FN-170T) to - 28.8‰ VPDB (

Figure 1,

Table 1).

The discovery of an intergrowth of honey-yellow ikaite crystals during a cruise on the R/V Geophysic in 1999 (site 0502) was reported in [

16]. Unfortunately, no analytical studies have been conducted on this sample.

Most of the ikaite samples are found in the “sea continuation” of the Yenisei River (

Figure 1). Only one site with ikaite was found within the zone of influence of the Ob River waters (BR03-07,

Figure 1).

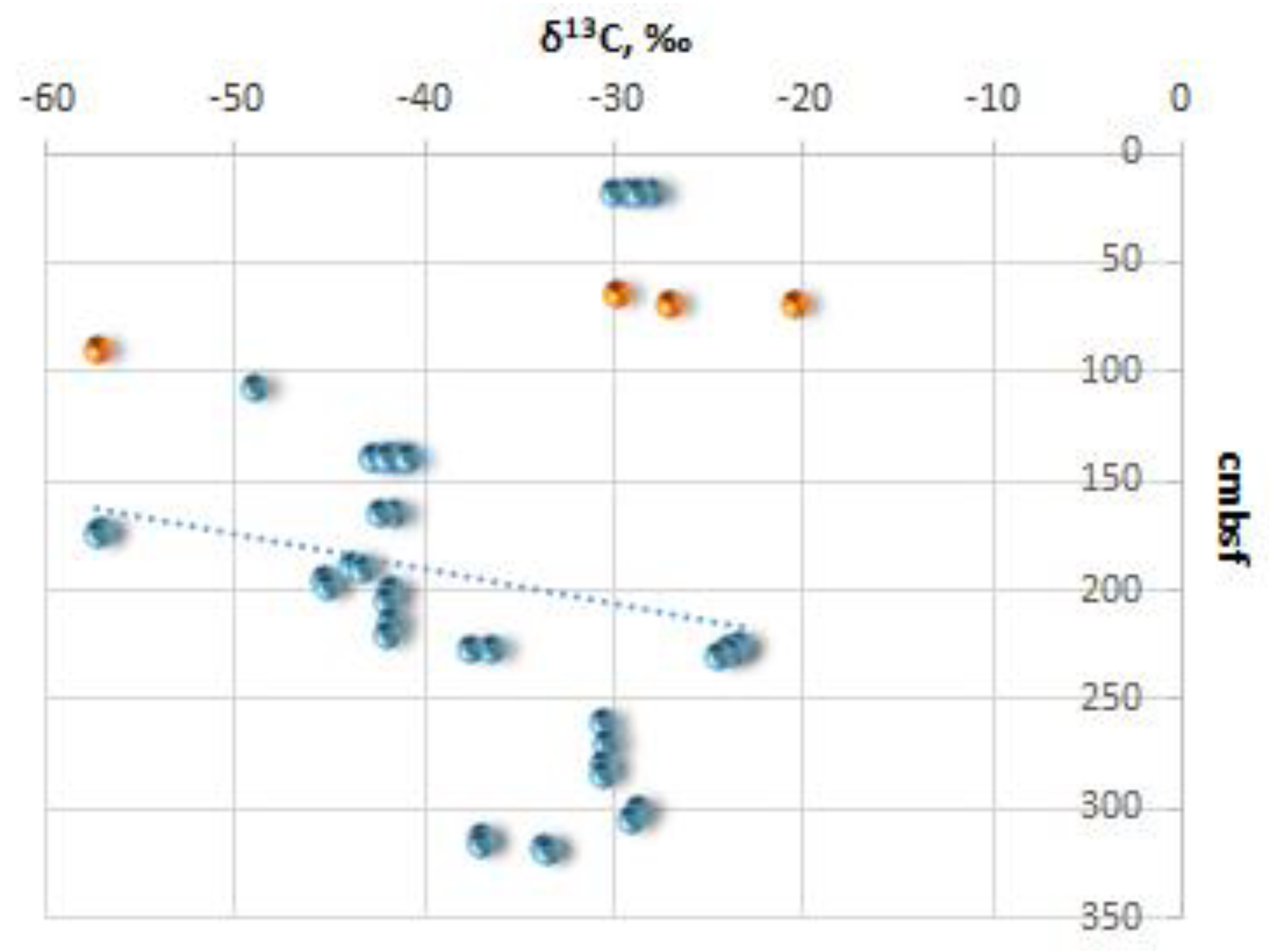

The measured δ

13С (

Figure 5) and δ

18О values of all ikaite samples from the Kara Sea range from -57.3 (site FN-170T) to - 20.5‰ VPDB (site FN-76T) and from -1.3 (site FN-169T) to 1.84‰ (st. 170T) VPDB, respectively (

Table 1). It is important to note that the ikaite samples with the highest and lowest carbon isotopic values (δ

13C) were collected during our expedition on the R/V Fridtjof Nansen. In the sediment samples from site FN-169T we detected the following values: C

org content (1.7...1.84%), C

carb content (0.08%), and δ

13Сorg (-25.5 ‰) (

Table 1).

4. Discussion

Carbon Isotope (δ13С) in Ikaite

The variation in δ

13C values of ikaite samples from the Kara Sea, ranging from -20.5‰ at site FN-76T to -57.3‰ VPDB at sites FN-170T and PB03-07, provides insight into the primary carbon sources involved in the formation of ikaite. Authigenic carbonates with extremely low δ

13C values typically form in sediments within areas of focused discharge of hydrocarbon fluids. In these areas, isotopically light carbon released during anaerobic methane oxidation enters the crystal lattice of the carbonates. Such anhydrous methane-derived carbonates with an isotope composition as light as -60.1‰ VPDB have also been found in the sediments at site BR00-37 in the Kara Sea [

20]. The average isotopic composition of the total organic carbon in the exospheric reservoirs is approximately δ

13Corg = -22‰ [

20]. Therefore, the δ

13C values of ikaite samples that contain carbon from organic matter are expected to vary around this value. The wide range of δ

13C values observed in ikaite samples from the Kara Sea can be explained by the different sources of carbon that contributed to their formation. The main sources of carbon were organic matter and methane.

Carbon Mass Balance in Ikaite

Carbon can be incorporated into calcium carbonate hexahydrate in a similar way to that of marine early diagenetic authigenic carbonates [

26]. The main sources of dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) in pore water include: 1) the oxidation of organic matter (OM); 2) anaerobic oxidation of methane (AOM); 3) carbon from the oxidation of methane homologues. However, the real sources of carbon in our ikaite samples could be the first two components mentioned above: oxidized organic matter and AOM. Indeed, hydrocarbon gases in the Late Pleistocene-Holocene ikaites-bearing sediments of the Kara Sea are composed almost entirely of methane [

20]. Therefore, the carbon from methane homologues (C

2+) can be ignored. Thus, the mass fractions of different carbon sources can be calculated using the following simple formula:

where F

DIC is the DIC fraction of pore water that ikaite crystallizes from; F

OM is the proportion of carbon released during the oxidation of OM; F

CH4 is the proportion of carbon released during AOM.

Considering the δ

13C values of each carbon source, we can write the mass balance equation as follows:

The initial values for the balance calculations (δ

13C-CH

4 and δ

13C-C

org values) are presented in

Table 1. To calculate the carbon source budget for ikaites from our study sites (FN-76T, FN-169T, and FN-170T), we used the δ

13C-C

org value measured in sediments from site 169T. During the anaerobic oxidation of organic matter in the sulfate reduction zone, there is minimal isotopic fractionation occurs (e.g. [

27]). Therefore, carbon with an isotopic composition close to that of the organic matter enters the pore water. Unfortunately, during the expedition of the R/V Fridtjof Nansen, it was not possible to obtain sufficient methane concentrations to measure δ

13C-CH

4 values. Therefore, we used data from previous studies on cores containing ikaite from the Kara Sea [

12,

20]. The minimum δ

13С value of methane in these cores is -86‰, and the maximum is -78.2‰ VPDB (see

Table 1,

Table 3). At a temperature of -1.4 °C, the coefficients of carbon isotopic fractionation between ikaite and DIC in pore water are α = 1.001-1.002, as reported by M. Whiticar and E. Suess [

28]. This means that the isotopic compositions of their carbon will differ by 1-2‰ (

Table 3).

Based on the data provided, we can determine the proportions of different carbon sources in our ikaite samples (

Table 3).

Table 3.

Proportions of carbon from methane and organic matter in the composition of ikaites.

Table 3.

Proportions of carbon from methane and organic matter in the composition of ikaites.

| Ikaite occurrence cmbsf |

δ13C-ikaite ‰ VPDB |

δ13C-DIC ‰ VPDB |

δ13C-CH4 ‰ VPDB |

δ13C-Corg ‰ VPDB |

CH4 % |

OM % |

| Site FN-76T |

| 70 |

-20.5 |

-21.5 |

-78.2…-86.0 |

-25.5 |

0 |

100 |

| Site FN-169T |

65-69

70-74 |

-29.8

-27.0 |

-30.8

-28.0 |

|

|

9-10

4-5 |

90-91

95-96 |

| Site FN-170T |

| 90 |

-57.3 |

-58.3 |

|

|

54-62 |

38-46 |

All carbon in the crystal lattice of ikaite from site FN-76T originated from the oxidation of organic matter. For site FN-170T, however, methane was the main source of carbon (54-62%) in ikaite. In samples from site FN-169T, most of the carbon was derived from the breakdown of organic matter (90-96%), with only a small amount coming from AOM (4-10%).

Oxygen Isotopes (δ18O) in Ikaites

The oxygen isotope composition of ikaite's "carbonate part", as well as anhydrous carbonates, is dependent on the δ

18O values of pore waters and crystallization temperature. The measured δ

18О ikaite values vary from -1.3 (site 169T) to 1.84‰ VPDB (site 170T), with a difference of 3.14‰ (

Table 1). The bottom temperatures in the area where samples were taken ranged from -1.3 to -1.5 °C. Based on the available data, the theoretical δ

18O value of the pore water from which the ikaite crystallized could be calculated using the following equation, which is commonly used for calcites [

29]:

where α—oxygen isotope fractionation factor, T—temperature in Kelvin.

The theoretical δ

18O values of pore water depends on temperature, and are therefore provided in

Table 4 for both bottom temperatures of -1.3 and -1.5 °C. The calculation results indicate that the theoretical δ

18O values of the pore water range from -4.8 to -1.6‰ VSMOW (

Table 4). These pore water δ

18O isotopic values approximately correspond to variations in Kara Sea water salinity from -33 to -27‰ [

30,

31]. This indicates a relatively weak desalination process during the crystallization of ikaites. Variations in the theoretical pore water δ

18O values calculated are likely due to changes in the depth of penetration of river water (mainly from the Yenisei River) into the Kara Sea over time.

REE and Tract Elements

Generally, marine carbonate rocks have their own characteristic REE pattern [

32] which are: (1) homogeneous HREE enrichment (2) La positive anomalies and (3) Ce negative anomalies if the carbonate rocks were deposited in oxidizing condition.

Because Ce and Eu have two ions with different electrovalence, they often show anomaly in chemical sedimentary rocks. The negative anomaly of Ce results from the differentiation between Ce

3+ and adjacent elements due to the oxidation of Ce

3+ into Ce

4+. In oxidized water, soluble Ce

3+ oxidizes to into insoluble Ce

4+, which is then fixed within sedimentary particles and organic matter. This reaction causes a loss of Ce in water. Therefore, the redox condition of water during carbonate deposition can be inferred from the enrichment or loss of Ce ion between its atom and adjacent elements (e.g. [

33]).

Table 4.

Theoretical calculated δ18O values of pore water in which ikaites crystallized.

Table 4.

Theoretical calculated δ18O values of pore water in which ikaites crystallized.

| Site |

δ18O ikaite, ‰ VPDB |

δ18O pore water, VSMOW |

| t = -1.3 °C |

t = -1.5 °C |

| 76t |

1.45 |

-2.0 |

-2.1 |

| 169t |

-0.5 |

-3.9 |

-4.0 |

| -1.3 |

-4.7 |

-4.8 |

| 170t |

-1.84 |

-1.6 |

-1.7 |

Moderate Ce negative anomalies observed in carbonates are consistent with modern seawater [

34], and, therefore, provide strong evidence about formation in a seawater environment that was mostly oxygenated. In our study, a minor negative Ce anomaly was recorded in the sample of bottom sediment containing ikaite but was not present in the ikaite samples. The Ce/Ce* values in our ikaites (0,94 and 1,03) likely reflect a redox environment.

Eu positive anomaly is usually caused by the differentiation of Eu

3+ ions from neighboring elements due to their reduction to Eu

2+. Eu

3+ is reduced to Eu

2+, which reduces the radius of Eu ions and enables Eu ions to substitute Ca

2+ into the crystal lattice of carbonates. There are Eu and Gd positive anomalies in our samples that are different from Eu/Eu* in modern seawater. The Eu positive anomalies in marine carbonate rocks could not be directly caused by the reduction of seawater, but by the mixing of dust (e.g. continental weathering product), river water or hydrothermal fluid with seawater [

32]. Obviously, the latter option is extremely unlikely.

The MREE-bulge (Sm-Dy) observed in ikaite, and sediment samples could likely reflect the presence of organic matter during early diagenesis [

35]. Superchondritic Y/Ho ratios of the studied ikaites (28 and 29) reflect a significant input of clastic material during ikaite formation [

36].

5. Conclusions

The sediments of the Kara Sea contain a significant amount of ikaite, which forms at depths between 10 and 320 cmbsf. Below this level, the ikaite is likely transformed into anhydrous forms of calcium carbonate (

Table 1). The findings of these minerals are mainly located in areas along the continuation of the Yenisei (8 sites) and Ob (1 site) Rivers. The primary factor influencing the formation of ikaite crystals is the diagenesis of organic matter. This process results in the release of phosphate ions into the pore water, which stabilizes ikaite. The relationship between river runoff and ikaite formation is likely due to the supply of organic carbon from rivers, which promotes early diagenetic processes. In some cases, a second source of carbon in ikaite may be the process of anaerobic oxidation of methane. The latter can be identified based on the light isotopic composition of carbon (δ

13C) in ikaite. In areas with intense methane seepage and rapid AOM, the formation of anhydrous calcium carbonate crystals is more likely.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.K., E.A.L. and E.A.G.; methodology, A.A.K., E.A.L., Ya.Ya.; software, E.Z.; validation, A.K., E.L., E.G., Ya.Ya. and Z.Z.; formal analysis, M.K., A.S.D., O.I.O.; investigation, A.A.K., E.A.L., E.A.G., D.U.; resources, A.S.D., O.I.O.; data curation, E.L.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.K.; writing—review and editing, A.A.K., E.A.L., Y.Z.; visualization, A.A.K., E.A.L.; supervision, E.A.G.; project administration, A.A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Russian Science Foundation, grant No 23-27-00457.

Data Availability Statement

All data used during the study appear in the submitted article.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the crew of the R/V Fridtjof Nansen for their assistance in expeditionary work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rogov, M.; Ershova, V.; Vereshchagin, O.; Vasileva, K.; Mikhailova, K.; Krylov, A. Database of Global Glendonite and Ikaite Records throughout the Phanerozoic. Earth Syst Sci Data 2021, 13, 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogov, M.; Ershova, V.; Gaina, C.; Vereshchagin, O.; Vasileva, K.; Mikhailova, K.; Krylov, A. Glendonites throughout the Phanerozoic. Earth Sci Rev 2023, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickers, M.L.; Vickers, M.; Rickaby, R.E.M.; Wu, H.; Bernasconi, S.M.; Ullmann, C.V.; Bohrmann, G.; Spielhagen, R.F.; Kassens, H.; Pagh Schultz, B.; et al. The Ikaite to Calcite Transformation: Implications for Palaeoclimate Studies. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 2022, 334, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krylov, A.A.; Logvina, E.A.; Matveeva, T.V.; Prasolov, E.M.; Sapega, V.F.; Demidova, A.L.; Radchenko, M.S. Ikaite (CaCO3 6H2O) in the Bottom Sediments of the Laptev Sea and the Role of Anaerobic Oxidation of Methane in the Process of Its Formation. Zapiski RMO (Proceedings of the Russian Mineralogical Society) 2015, 61–75. [Google Scholar]

- Kolesnik, O.N.; Kolesnik, A.N.; Karabtsov, A.A.; Vasilenko, Y.P. Ikaite from Holocene Sediments of the Chukchi Sea. Doklady Earth Sciences 2025, 520. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, M.E. Calcite pseudomorphs (pseudogaylusite, jarrowite, thinolite, glendonite, gennoishi) in sedimentary rocks. The origin of pseudomorphs. Lithol. Miner. Resour. 1979, 125–141. [Google Scholar]

- Suess, E.; Balzer, W.; Hesse, K.-F.; Müller, P.J.; Ungerer, C.A.; Wefer, G. Calcium Carbonate Hexahydrate from Organic-Rich Sediments of the Antarctic Shelf: Precursors of Glendonites. Science (1979) 1982, 216, 1128–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, B.; Thibault, N.; Huggett, J. The Minerals Ikaite and Its Pseudomorph Glendonite: Historical Perspective and Legacies of Douglas Shearman and Alec K. Smith. Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association 2022, 133, 176–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogov, M.A.; Ershova, V.B.; Shchepetova, E.V.; Zakharov, V.A.; Pokrovsky, B.G.; Khudoley, A.K. Earliest Cretaceous (Late Berriasian) Glendonites from Northeast Siberia Revise the Timing of Initiation of Transient Early Cretaceous Cooling in the High Latitudes. Cretac Res 2017, 71, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, B.P.; Huggett, J.; Ullmann, C.V.; Kassens, H.; Kölling, M. Links between Ikaite Morphology, Recrystallised Ikaite Petrography and Glendonite Pseudomorphs Determined from Polar and Deep-Sea Ikaite. Minerals 2023, 13, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, C.J.; Nürnberg, D.; Scheele, N.; Pauer, F.; Kriews, M. 13C Isotope Depletion in Ikaite Crystals: Evidence for Methane Release from the Siberian Shelves ? Geo-Marine Letters 1997, 17, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodina, L.A.; Tokarev, V.G.; Vlasova, L.N.; Korobeinik, G.S. Contribution of Biogenic Methane to Ikaite Formation in the Kara Sea: Evidence from the Stable Carbon Isotope Geochemistry. In Siberian River Run-off in the Kara Sea: Characterisation, Quantification, Variability, and Environmental Significance; Stein, R., Galimov, E.M., Fahl, K., Fütterer, D.K., Stepanets, O.V., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, 2003; Vol. 6, pp. 349–374. [Google Scholar]

- Greinert, J.; Derkachev, A. Glendonites and Methane-Derived Mg-Calcites in the Sea of Okhotsk, Eastern Siberia: Implications of a Venting-Related Ikaite/Glendonite Formation. Mar Geol 2004, 204, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teichert, B.M.A.; Luppold, F.W. Glendonites from an Early Jurassic Methane Seep - Climate or Methane Indicators? Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 2013, 390, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, C.; Rogov, M.; Wierzbowski, H.; Ershova, V.; Suan, G.; Adatte, T.; Föllmi, K.B.; Tegelaar, E.; Reichart, G.-J.; de Lange, G.J.; et al. Glendonites Track Methane Seepage in Mesozoic Polar Seas. Geology 2017, 45, 503–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusev, Ye.A.; Matyushev, A.P.; Rudoy, A.S.; Usov, A.N. Quaternary Deposits in the Central Part of the Kara Sea. In Oceanological Research in the Arctic Region; Lisitsyn, A.P., Vinogradov, M.E., Romankevich, E.A., Eds.; Nauchniy Mir: Moscow, 2001; pp. 533–558. [Google Scholar]

- Levitan, M.A.; Krupskaya, V.V.; Frolova, E.A.; Vlasova, L.N. First Results of the Sediment Studies. Ber. Polarforsch. Meeresforsch 2004, 479, 44–54. [Google Scholar]

- Lein, A.Y.; Makkaveev, P.N.; Savvichev, A.S.; Kravchishina, M.D.; Belyaev, N.A.; Dara, O.M.; Ponyaev, M.S.; Zakharova, E.E.; Rozanov, A.G.; Ivanov, M.V.; et al. Transformation of Suspended Particulate Matter into Sediment in the Kara Sea in September of 2011. Oceanology 2013, 53, 570–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baturin, G.N.; Dubinchuk, V.T.; Pokrovsky, B.G.; Novigatsky, A.N.; Dmitrenko, O.B.; Oskina, N.S. Phosphatized Calcareous Conglomerate from the Kara Sea Floor. Oceanology 2016, 56, 690–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galimov, E.M.; Kodina, L.A.; Stepanets, O.V.; Korobeinik, G.S. Biogeochemistry of the Russian Arctic. Kara Sea: Research Results under the SIRRO Project, 1995-2003. Geochemistry International 2006, 44, 1053–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

Scientific Cruise Report of the Kara Sea Expedition of RV Akademik Boris Petrov in 1997 (Wissenschaftlicher Fahrtbericht Über Die Karasee-Expedition von 1997 Mit FS Akademik Boris Petrov); Matthiessen, J., Stepanets, O.V., Eds.; Ber. Polarforsch. Meeresforsch., 1998; Vol. 266. [Google Scholar]

-

Scientific Cruise Report of the Kara-Sea Expedition 2001 of RV “Akademik Boris Petrov”: The German-Russian Project on Siberian River Run-off (SIRRO) and the EU Project “ESTABLISH”; Stein, R., Stepanets, O., Eds.; Ber. Polarforsch. Meeresforsch., 2002; Vol. 419. [Google Scholar]

- Purgstaller, B.; Dietzel, M.; Baldermann, A.; Mavromatis, V. Control of Temperature and Aqueous Mg2+/Ca2+ Ratio on the (Trans-)Formation of Ikaite. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 2017, 217, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLennan, S.M. Rare earth elements in sedimentary rocks: Influence of provenance and sedimentary processes. In Geochemistry and Mineralogy of Rare Earth Elements; 1989; pp. 169–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodina, L.A.; Tokarev, V.G.; Vlasova, L.N. New Findings of Ikaite in the Kara Sea During RV “Akademik Boris Petrov” Cruise 36. In Scientific Cruise Report of the Kara-Sea Expedition 2001 of RV “Akademik Boris Petrov”: The German-Russian Project on Siberian River Run-off (SIRRO) and the EU Project “ESTABLISH”; Stein, R., Stepanets, O., Eds.; Ber. Polarforsch. Meeresforsch., 2002; Vol. 419, pp. 164–172. [Google Scholar]

- Lein, A.Y. Authigenic Carbonate Formation in the Ocean. Lithology and Mineral Resources 2004, 39, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, N.E.; Aller, R.C. Anaerobic Methane Oxidation on the Amazon Shelf. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 1995, 59, 3707–3715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiticar, M.J.; Suess, E. The Cold Carbonate Connection between Mono Lake, California and the Bransfield Strait, Antarctica. Aquat Geochem 1998, 4, 429–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-T.; O’neil, J.R. Equilibrium and Nonequilibrium Oxygen Isotope Effects in Synthetic Carbonates; 1997; Vol. 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubinina, E.O.; Kossova, S.A.; Miroshnikov, A.Y.; Fyaizullina, R.V. Isotope Parameters (ΔD, Δ18O) and Sources of Freshwater Input to Kara Sea. Oceanology 2017, 57, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossova, S.A.; Dubinina, E.O.; Chizhova, Yu.N. Estimation of River Runoff Isotopic Parameters (ΔD, Δ18O) under Conditions of Multicomponent Freshening Using the Example of the Ob and Yenisei Rivers. In Proceedings of the Geology of seas and oceans. Materials of the XXV International Scientific Conference (School) on Marine Geology, Moscow; 2023; pp. 88–91. [Google Scholar]

- Van Kranendonk, M.J.; Webb, G.E.; Kamber, B.S. Geological and Trace Element Evidence for a Marine Sedimentary Environment of Deposition and Biogenicity of 3.45 Ga Stromatolitic Carbonates in the Pilbara Craton, and Support for a Reducing Archaean Ocean. Geobiology 2003, 1, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frimmel, H.E. Trace Element Distribution in Neoproterozoic Carbonates as Palaeoenvironmental Indicator. Chem Geol 2009, 258, 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alibo, D.S.; Nozaki, Y. Rare Earth Elements in Seawater: Particle Association, Shale-Normalization, and Ce Oxidation. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 1999, 63, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Ren, J.; Guo, Q.; Cao, J.; Wang, H.; Liu, C. Rare Earth Element Geochemistry Characteristics of Seawater and Porewater from Deep Sea in Western Pacific. Sci Rep 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, G.E.; Kamber, B.S. Rare Earth Elements in Holocene Reefal Microbialites: A New Shallow Seawater Proxy. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 2000, 64, 1557–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischoff, J.L.; Fitzpatrick, J.A.; Rosenbauer, R.J. The Solubility and Stabilization of Ikaite (CaCO3·6H2O) from 0° to 25 °C: Environmental and Paleoclimatic Implications for Thinolite Tufa. Journal of Geology 1993, 101, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, E.A.; Walter, L.M. The Role of PH in Phosphate Inhibition of Calcite and Aragonite Precipitation Rates in Seawater. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 1990, 54, 797–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.P.; Singer, P.C. Inhibition of Calcite Precipitation by Orthophosphate: Speciation and Thermodynamic Considerations. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 2006, 70, 2530–2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiticar, M.J.; Suess, E.; Wefer, G.; Müller, P.J. Calcium Carbonate Hexahydrate (Ikaite): History of Mineral Formation as Recorded by Stable Isotopes. Minerals 2022, 12, 1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Lu, Z.; Rickaby, R.E.M.; Domack, E.W.; Wellner, J.S.; Kennedy, H.A. Ikaite Abundance Controlled by Porewater Phosphorus Level: Potential Links to Dust and Productivity. Journal of Geology 2015, 123, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krylov, A.A.; Logvina, E.A.; Semenov, P.B.; Bochkarev, A.V.; Kil, A.O.; Shatrova, E.V. Unusual Authigenic Carbonates (Mg-Calcite and Ikaite) in the Gas Hydrate-Bearing Structure “VNIIOkeangeologia” (Deryugin Basin, Sea of Okhotsk). Relief and Quaternary deposits of the Arctic, sub-Arctic and North-West Russia 2023, 405–414. [Google Scholar]

- Chaka, A.M. Quantifying the Impact of Magnesium on the Stability and Water Binding Energy of Hydrated Calcium Carbonates by Ab Initio Thermodynamics. Journal of Physical Chemistry A 2019, 123, 2908–2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tollefsen, E.; Stockmann, G.; Skelton, A.; Mörth, C.-M.; Dupraz, C.; Sturkell, E. Chemical Controls on Ikaite Formation. Mineral Mag 2018, 82, 1119–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockmann, G.; Tollefsen, E.; Skelton, A.; Brüchert, V.; Balic-Zunic, T.; Langhof, J.; Skogby, H.; Karlsson, A. Control of a Calcite Inhibitor (Phosphate) and Temperature on Ikaite Precipitation in Ikka Fjord, Southwest Greenland. Applied Geochemistry 2018, 89, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tollefsen, E.; Balic-Zunic, T.; Mörth, C.-M.; Brüchert, V.; Lee, C.C.; Skelton, A. Ikaite Nucleation at 35 °C Challenges the Use of Glendonite as a Paleotemperature Indicator. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 8141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berner, R.A. The Role of Magnesium in the Crystal Growth of Calcite and Aragonite from Sea Water. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 1975, 39, 489–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulikov, H.N. Mineral Composition of the Sandy-Silty Part of the Kara Sea Sediments. In Geology of the Sea; NIIGA Publishing House: Leningrad, 1971; Vol. 1, pp. 64–72. [Google Scholar]

- Kravchishina, M.D.; Lein, A.Y.; Savvichev, A.S.; Reykhard, L.E.; Dara, O.M.; Flint, M.V. Authigenic Mg-Calcite at a Cold Methane Seep Site in the Laptev Sea. Oceanology 2017, 57, 174–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logvina, E.; Krylov, A.; Taldenkova, Е.; Blinova, V.; Sapega, V.; Novikhin, A.; Kassens, H.; Bauch, H.A. Mechanisms of Late Pleistocene Authigenic Fe–Mn-Carbonate Formation at the Laptev Sea Continental Slope (Siberian Arctic). arktos 2018, 4, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruban, A.; Rudmin, M.; Mazurov, A.; Chernykh, D.; Dudarev, O.; Semiletov, I. Cold-Seep Carbonates of the Laptev Sea Continental Slope: Constraints from Fluid Sources and Environment of Formation. Chem Geol 2022, 610, 121103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 |

below the see floor - cmbsf |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).