Submitted:

09 December 2024

Posted:

10 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) represents a significant public health concern, particularly in men aged 55 to 64, where it occurs in about 1%. We investigated metabolomics and genetics of AAA by analyzing a cohort consisting of 76 patients diagnosed with AAA and 228 matched controls. Utilizing the Metabolon DiscoveryHD4 platform for non-targeted metabolomics profiling, we identified 11 novel metabolites that significantly increased the risk of AAA. These metabolites were primarily associated with environmental and lifestyle factors, notably smoking and pesticide exposure, which underscores the influence of external factors on the progression of AAA. Additionally, several genetic variants were associated with xenobiotics, highlighting a genetic predisposition that may exacerbate the effects of these environmental exposures. The integration of metabolomic and genetic data provides compelling evidence that lifestyle, environmental, and genetic factors are intricately linked to the etiology of AAA. The results of our study not only deepen the understanding of the complex pathophysiology of AAA but also pave the way for the development of targeted therapeutic strategies.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Baseline Characteristics of AAA Cases and Controls

2.2. Differences in the Metabolite Abundances Between the AAA Cases and Controls

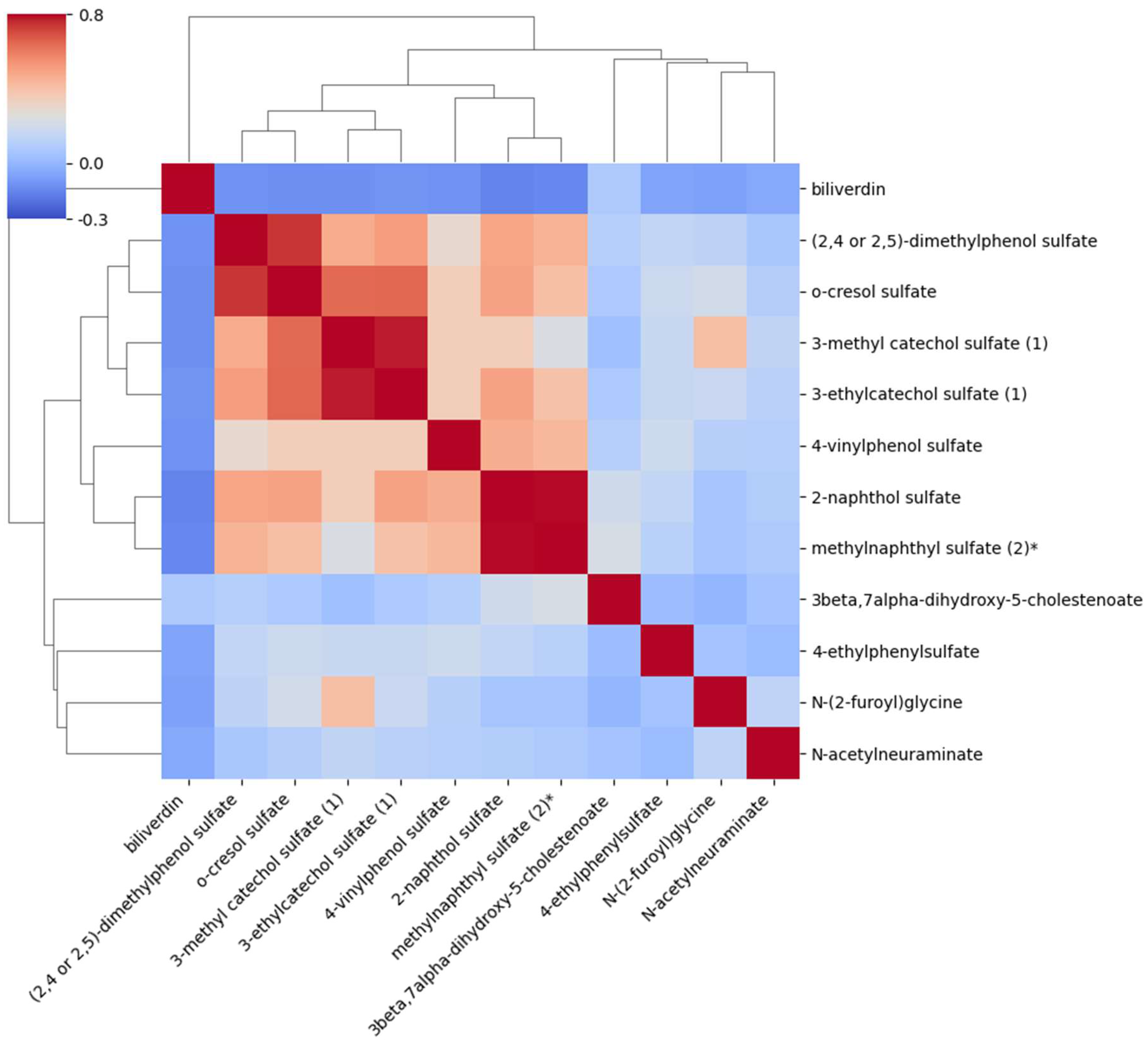

2.3. Correlations Between the Metabolites Associated with AAA

2.4. Association of the Genetic Variants with Metabolites in Patients with AAA

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Population

4.2. Clinical and Laboratory Measurements

4.3. Metabolomics

4.4. Selection of Genetic Variants Associated with Increased Risk of AAA

4.5. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012; 380: 2095–2128. [CrossRef]

- Singh K, Bonaa KH, Jacobsen BK, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for abdominal aortic aneurysms in a population-based study: The Tromso Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2001; 154: 236–244.

- Powell JT, Greenhalgh RM. Clinical practice. Small abdominal aortic aneurysms. N Engl J Med. 2003; 348: 1895–1901.

- Scott RA, Wilson NM, Ashton HA, et al. Influence of screening on the incidence of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm: 5-year results of a randomized controlled study. Br J Surg. 1995; 82: 1066–1070. [CrossRef]

- Lederle FA, Johnson GR, Wilson SE. Aneurysm detection and management veterans affairs cooperative study. Abdominal aortic aneurysm in women. J Vasc Surg. 2001; 34: 122–126.

- Lederle FA, Johnson GR, Wilson SE, et al. The aneurysm detection and management study screening program: Validation cohort and final results. Arch Intern Med. 2000; 160: 1425–1430.

- Khan H, Abu-Raisi M, Feasson M, Shaikh F, Saposnik G, et al. Current prognostic biomarkers for abdominal aortic aneurysm: a comprehensive scoping review of the literature. Biomolecules. 2024; 14: 661. [CrossRef]

- Torres-Fonseca M, Galanb M, Martinez-Lopez D, Canes L, Roldan-Monteroa R, et al. Pathophysiology of abdominal aortic aneurysm: Pathophysiology of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Atherosclerosis. 2019; 31: 166–177.

- Bengtsson H, Ekberg O, Aspelin P, et al. Ultrasound screening of the abdominal aorta in patients with intermittent claudication. Eur J Vasc Surg. 1989; 3: 497–502. [CrossRef]

- Cabellon S, Jr, Moncrief CL, Pierre DR, et al. Incidence of abdominal aortic aneurysms in patients with atheromatous arterial disease. Am J Surg. 1983; 146: 575–576. [CrossRef]

- Fleming C, Whitlock EP, Beil TL, et al. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: A best-evidence systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2005; 142: 203–211. [CrossRef]

- Salo JA, Soisalon-Soininen S, Bondestam S, et al. Familial occurrence of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Ann Intern Med. 1999; 130: 637–642. [CrossRef]

- Jones GT, Tromp G, Kuivaniemi H, Gretarsdottir S, Baas AF, Giusti B, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies for abdominal aortic aneurysm identifies four new disease-specific risk loci. Circ Res. 2017; 120: 341–353. [CrossRef]

- Chaikof EL, et al. The Society for Vascular Surgery practice guidelines on the care of patients with an abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg. 2018; 67: 2–77. [CrossRef]

- Ramprasath T, Han Y-M, Zhang D, Yu C-J, Ming-Hui MH. Tryptophan catabolism and inflammation: a novel therapeutic target for aortic diseases. Front Immunol. 2021; 12: 731701. [CrossRef]

- Ling X, Jie W, Qin X, Zhang S, Shi K, Li T, et al. Gut microbiome sheds light on the development and treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022; 9: 1063683. [CrossRef]

- Benson TW, Conrad KA, Li XS, Wang Z, Helsley RN, Schugar RC, et al. Gut microbiota-derived trimethylamine N-oxide contributes to abdominal aortic aneurysm through inflammatory and apoptotic mechanisms. Circulation. 2023; 147(14): 1079–1096. [CrossRef]

- Ma Y, Li D, Cui F, Wang J, Tang L, Yang Y, Liu R, Tian Y. Air pollutants, genetic susceptibility, and abdominal aortic aneurysm risk: a prospective study. Eur Heart J. 2024; 45(12): 1030–1039. [CrossRef]

- Ramesh A, Prins PA, Perati PR, Rekhadevi PV, Sampson UK. Metabolism of benzo(a)pyrene by aortic subcellular fractions in the setting of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Mol Cell Biochem. 2016; 411(1-2): 383–391. [CrossRef]

- Rupérez FJ, Ramos-Mozo P, Teul J, Martinez-Pinna R, Garcia A, et al. Metabolomic study of plasma of patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2012; 403(6): 1651–1660. [CrossRef]

- Ciborowski M, Teul J, Martin-Ventura JL, Egido J, Barbas C. Metabolomics with LC-QTOF-MS permits the prediction of disease stage in aortic abdominal aneurysm based on plasma metabolic fingerprint. PLoS One. 2012; 7(2): e31982. [CrossRef]

- Qureshi MI, Greco M, Vorkas PA, Holmes E, Davies AH. Application of metabolic profiling to abdominal aortic aneurysm research. J Proteome Res. 2017; 16(7): 2325–2332. [CrossRef]

- Guo Y, Wan S, Han M, Zhao Y, Li C, Cai G, Zhang S, Sun Z, Hu X, Cao H, Li Z. Plasma Metabolomics Analysis Identifies Abnormal Energy, Lipid, and Amino Acid Metabolism in Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms. Med Sci Monit. 2020; 26: e926766. [CrossRef]

- Lieberg J, Wanhainen A, Ottas A, Vähi M, Mihkel Zilmer M, et al. Metabolomic profile of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Metabolites. 2021; 11(8): 555. [CrossRef]

- Liu J, Liu M, Feng J, Zhu H, Wu J, Zhang H, et al. Alpha-ketoglutarate ameliorates abdominal aortic aneurysm via inhibiting PXDN/HOCL/ERK signaling pathways. J Transl Med. 2022; 20(1): 461. [CrossRef]

- Sun L-Y, Lyu Y-Y, Zhang H-Y, Zhi Shen Z, Lin G-Q, et al. Nuclear receptor NR1D1 regulates abdominal aortic aneurysm development by targeting the mitochondrial tricarboxylic acid cycle enzyme aconitase-2. Circulation. 2022; 146(21): 1591–1609. [CrossRef]

- Chinetti G, Carboni J, Murdaca J, Moratal C, Sibille B, Raffort J, Lareyre F, Baptiste EJ, Hassen-Khodja R, Neels JG. Diabetes-induced changes in macrophage biology might lead to reduced risk for abdominal aortic aneurysm development. Metabolites. 2022; 12(2): 128. [CrossRef]

- Xie T, Lei C, Song W, Wu X, Wu J, et al. Plasma lipidomics analysis reveals the potential role of lysophosphatidylcholines in abdominal aortic aneurysm progression and formation. Int J Mol Sci. 2023; 24(12): 10253. [CrossRef]

- Vanmaele A, Bouwens E, Hoeks SE, Kindt A, Lamont L, et al. Targeted proteomics and metabolomics for biomarker discovery in abdominal aortic aneurysm and post-EVAR sac volume. Clin Chim Acta. 2024; 554: 117786. [CrossRef]

- Daniele A, Parenti G, d’Addio M, Andria G, Ballabio A, Meroni G. Biochemical characterization of arylsulfatase E and functional analysis of mutations found in patients with X-linked chondrodysplasia punctata. Am J Hum Genet. 1998; 62: 562–572. [CrossRef]

- Baubec T, Ivanek R, Lienert F, Schubeler D. Methylation-dependent and -independent genomic targeting principles of the MBD protein family. Cell. 2013; 153: 480–929. [CrossRef]

- Huang L-Y, Hsu D-W, Pears CJ. Methylation-directed acetylation of histone H3 regulates developmental sensitivity to histone deacetylase inhibition. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021; 49(7): 3781–3795. [CrossRef]

- Kunita R, Otomo A, Joh-E Ikeda J-E. Identification and characterization of novel members of the CREG family, putative secreted glycoproteins expressed specifically in brain. Genomics. 2002; 80: 456–460.

- Kutsuno Y, Hirashima R, Sakamoto M, Ushikubo H, Michimae H, et al. Expression of UDP-Glucuronosyltransferase 1 (UGT1) and glucuronidation activity toward endogenous substances in humanized UGT1 mouse brain. Drug Metab Dispos. 2015; 43(7): 1071–1076. [CrossRef]

- Štefanac T, Grgas D, Landeka Dragičević T. Xenobiotics-Division and Methods of Detection: A Review. J Xenobiot. 2021; 11(4): 130–141.

- Bulka CM, Daviglus ML, Persky VW, et al. Association of occupational exposures with cardiovascular disease among US Hispanics/Latinos. Heart. 2019; 105: 439–448. [CrossRef]

- Mostafalou S, Abdollahi M. Pesticides and human chronic diseases: evidences, mechanisms, and perspectives. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2013; 268(2): 157–177. [CrossRef]

- Lorenz DR, Misra V, Chettimada S, Uno H, Wang L, Blount BC, De Jesús VR, Gelman BB, Morgello S, Wolinsky SM, Gabuzda D. Acrolein and other toxicant exposures in relation to cardiovascular disease among marijuana and tobacco smokers in a longitudinal cohort of HIV-positive and negative adults. EClinicalMedicine. 2021; 31: 100697. [CrossRef]

- Alhamdow A, Lindh C, Albin M, et al. Early markers of cardiovascular disease are associated with occupational exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Sci Rep. 2017; 7: 9426. [CrossRef]

- Choi H, Harrison R, Komulainen H, et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. In: WHO Guidelines for Indoor Air Quality: Selected Pollutants. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK138709/.

- Patel AB, Shaikh S, Jain KR, Desai C, Madamwar D. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons: Sources, Toxicity, and Remediation Approaches. Front Microbiol. 2020; 11: 562813. [CrossRef]

- Mallah MA, Li C, Mallah MA, Noreen S, Liu Y, Saeed M, et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon and its effects on human health: An overview. Chemosphere. 2022; 296: 133948.

- Wu P. Association between polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons exposure with red cell width distribution and ischemic heart disease: insights from a population-based study. Sci Rep. 2024; 14: 196. [CrossRef]

- Ramesh A, Prins PA, Perati PR, Rekhadevi PV, Sampson UK. Metabolism of benzo(a)pyrene by aortic subcellular fractions in the setting of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Mol Cell Biochem. 2016; 411(1-2): 383–391. [CrossRef]

- Bulka CM, Daviglus ML, Persky VW, et al. Association of occupational exposures with cardiovascular disease among US Hispanics/Latinos. Heart. 2019; 105: 439–448. [CrossRef]

- Mostafalou S, Abdollahi M. Pesticides and human chronic diseases: evidences, mechanisms, and perspectives. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2013; 268(2): 157–177. [CrossRef]

- Nizioł J, Ossoliński K, Płaza-Altamer A, et al. Untargeted urinary metabolomics for bladder cancer biomarker screening with ultrahigh-resolution mass spectrometry. Sci Rep. 2023; 13: 9802. [CrossRef]

- Wishart DS, Guo AC, Oler E, et al. HMDB 5.0: the Human Metabolome Database for 2022. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022; 50(D1): 31. [CrossRef]

- Burzyńska P, Sobala ŁF, Mikołajczyk K, Jodłowska M, Jaśkiewicz E. Sialic Acids as Receptors for Pathogens. Biomolecules. 2021; 11(6): 831. [CrossRef]

- Alvi N, Nguyen P, Liu S, et al. Infected abdominal aortic aneurysm: a rare entity. JACC. 2020; 75(11_Supplement_1): 3187. [CrossRef]

- Vuruşkan E, Saraçoğlu E, Düzen İV. Serum bilirubin levels and the presence and progression of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Angiology. 2017; 68(5): 428–432. [CrossRef]

- Laakso M, Kuusisto J, Stančáková A, Kuulasmaa T, Pajukanta P, Lusis AJ, et al. The Metabolic Syndrome in Men study: a resource for studies of metabolic and cardiovascular diseases. J Lipid Res. 2017; 58: 481–493. [CrossRef]

- Inker LA, Eneanya ND, Coresh J, Tighiouart H, Wang D, Sang Y, et al. New creatinine- and cystatin C–based equations to estimate GFR without race. N Engl J Med. 2021; 385: 1737–1749. [CrossRef]

| Variable | Cases (n=76) | Controls (n=228) | |

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | p | |

| Age (years) | 62.91 ± 5.72 | 62.06 ± 5.62 | 0.258 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.48 ± 4.29 | 27.39 ± 3.91 | 0.957 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 140.93 ± 15.48 | 141.90 ± 15.33 | 0.968 |

| Total triglycerides (mmol/l) | 1.71 ± 1.52 | 1.31 ± 0.70 | 0.003 |

| LDL cholesterol (mmol/l) | 3.17 ± 0.85 | 3.29 ± 0.84 | 0.267 |

| Fasting plasma glucose (mmol/l) | 5.75 ± 0.51 | 5.64 ± 0.48 | 0.086 |

| Matsuda ISI (mg/dl, mU/l) | 5.26 ± 3,08 | 7.10 ± 4.79 | 0.004 |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m²) | 81.13 ± 16.25 | 83.73 ± 10.89 | 0.117 |

| hs-CRP (mg/l) | 4.03 ± 7.09 | 2.75 ± 5.06 | 0.004 |

| Smoking (%) | 40.8 | 15.4 | 3.0x10-6 |

| Statin medication (%) | 47.4 | 29.4 | 0.004 |

| Coronary heart disease medication (%) | 30.3 | 17.1 | 0.014 |

| Cases | Controls* | |||||

| Metabolite | Sub class | n | Mean ± SD | n | Mean ± SD | p |

| Xenobiotics | ||||||

| 2-naphthol sulfate | Chemical | 71 | 0.67 ±1.14 | 200 | -0.18 ± 0.97 | 4.7 x 10-6 |

| Methylnaphthyl sulfate | Chemical | 55 | 0.66 ±1.11 | 113 | -0.28 ± 1.01 | 1.2 x 10-7 |

| 4-vinylphenol sulfate | Benzoate Metab. | 76 | 0.60 ±1.23 | 227 | -0.17 ± 1.06 | 2.4 x 10-7 |

| 4-ethylphenylsulfate | Benzoate Metab. | 76 | 0.50 ± 1.07 | 227 | -0.17 ± 0.92 | 2.6 x 10-7 |

| (2,4 or 2,5)-dimethylphenol sulfate | Food/Plant | 62 | 0.52 ± 0.88 | 142 | -0.21 ± 0.95 | 8.1 x 10-7 |

| O-cresol sulfate | Benzoate Metab. | 70 | 0.58 ± 1.05 | 176 | -0.09 ± 0.93 | 1.9 x 10-6 |

| 3-methyl catecol sulfate | Benzoate Metab. | 76 | 0.55 ± 0.91 | 226 | -0.10 ± 1.05 | 2.0 x 10-6 |

| N-(2-furoyl)glycine | Food/Plant | 63 | 0.54 ± 1.19 | 167 | -0.11 ± 0.77 | 2.2 x 10-6 |

| 3-ethylcatechol sulfate | Food/Plant | 69 | 0.61 ± 0.95 | 187 | -0.05 ± 1.02 | 4.1 x 10-6 |

| Cofactors/Vitamins | ||||||

| Biliverdin | Hemoglobin/ Porphyrin Metab. | 76 | -0.39 ± 0.89 | 226 | 0.21 ± 1.06 | 1.2 x 10-5 |

| Carbohydrate | ||||||

| N-acetylneuraminate | Aminosugar Metab. | 76 | 0.45 ± 1.04 | 227 | -0.18 ± 1.11 | 2.4 x 10-5 |

| Lipid | ||||||

| 3beta,7alpha-dihydroxy-5-cholestenoate | Sterol | 71 | 0.46 ± 1.03 | 224 | -0.10 ± 0.93 | 2.5 x 10-5 |

| Metabolite | Genetic variant | p value | Beta | Gene |

| 2-naphthol sulfate | rs169828-T | 2 x 10-28 | 0.15 increase | ARSL |

| 4-vinylphenol sulfate | rs211644-C | 9 x 10-12 | 0.09 increase | ARSL |

| rs9461218-A | 1 x 10-19 | 0.10 increase | SLC17A1 | |

| 4-ethylphenylsulfate | rs13200784-T | 4 x 10-20 | 0.21 increase | SLC17A1 |

| rs556339-T | 4 x 10-24 | 0.11 increase | SLC17A3 | |

| rs144597325-T | 4 x 10-8 | 0.55 increase | LINC01919, MBD2 | |

| o-cresol sulfate | rs480400-G | 8 x 10-12 | 0.10 decrease | SGF29 |

| 3-methyl catechol sulfate | rs2342307-G | 5 x 10-12 | 0.13 decrease | SLC51A, PCYT1A |

| rs113759232-T | 5 x 10-13 | 0.50 decrease | LINC02499 | |

| rs9461218-A | 2 x 10-11 | 0.07 increase | SLC17A1 | |

| N-(2-furoyl)glycine | rs6751877-? | 6 x 10-24 | 0.78 decrease | CREG2 |

| 3-ethylcatechol sulfate | rs6795511-A | 1 x 10-11 | 0.18 increase | SLC51A, PCYT1A |

| rs1186313-C | 5 x 10-11 | 0.16 increase | SLC17A3 | |

| Biliverdin | rs10168416-?rs887829-T | 3 x 10-143 x 10-403 | 0.49 increase0.70 increase | UGT1A7, UGT1A8, UGT1A10,UGT1A9,UGT1A7,UGT1A3, UGT1A5, UGT1A6, UGT1A8, UGT1A9, UGT1A10, UGT1A4 |

| rs4148325-T | 6 x 10-19 | 0.27 increase | UGT1A5, UGT1A8, UGT1A10, UGT1A9, UGT1A3, UGT1A7, UGT1A6, UGT1A1, UGT1A4 | |

| rs1976391-A | 2 x 10-802 | 0.65 decrease | UGT1A8, UGT1A4,UGT1A7, UGT1A9, UGT1A5, UGT1A10, UGT1A6, UGT1A3 | |

| rs35754645-A | 2 x 10-250 | 0.51 increase | UGT1A3, UGT1A5, UGT1A10, UGT1A7, UGT1A6,UGT1A4, UGT1A9, UGT1A8 | |

| rs4149056-C | 1 x 10-13 | 0.17 increase | SLCO1B1 | |

| rs111366223-A | 4 x 10-8 | 1.48 decrease | FYB1 | |

| rs1871395-G | 3 x 10-15 | 0.15 increase | SLCO1B1 | |

| rs201662188-? | 3 x 10-23 | 0.12 decrease | SLCO1B1 | |

| N-acetylneuraminate | rs116448311-T | 8 x 10-84 | 1.31 increase | LAMC1 |

| rs78799057-A | 4 x 10-78 | 1.11 increase | NPL | |

| rs1354034-T | 1 x 10-23 | 0.15 decrease | ARHGEF3 | |

| rs2109101-A | 2 x 10-18 | 0.09 decrease | SNHG16 | |

| 3beta,7alpha-dihydroxy-5-cholestenoate | rs1573558-T | 3 x 10-42 | 0.26 increase | LINC02732 |

| rs7206511-A | 5 x 10-11 | 0.13 increase | FBXL19 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).